1. Introduction

Informational entropy analysis is often used in biology, but its meaning should be distinguished from that of thermodynamic entropy in molecular biology and evolution [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. The genetic information in DNA supplies straightforward examples for informational entropy concepts. The characteristic nucleotide sequence of the four bases (Adenine A, Guanine G, Cytosine C, and Thymine T) in an organism’s DNA is the same in all cells of the organism, and results in the combination of random mutations and functional selection during biological evolution. There is no preference for a specific sequence;

different DNA sequences are equally possible, and the actual DNA sequence has only a

probability

(where

is the number of bases in the DNA sequence, ranging from one million in bacteria to billions in many animals and plants). Therefore, the space of possible molecular configurations of molecules within an organism is astronomically large. We may assume that the system is “non-ergodic” in the sense that not every part of the configuration space can be explored [

3,

27,

28,

29,

30]. There are several major reasons to expect convergence [

3]. First, all evolutionary trajectories occur under certain generic selective constraints, such as the laws of mathematics, physics, and chemistry; these should lead to some universal features [

31,

32]. For instance, a novel quantum system (quantum dots) recently proposed by the author (2024) [

33], due to the system’s peculiar quantum state–a Diophantine Markov state, would be trapped in a sequence of self-replicating states and would never reach a classical limit, no matter how big the cube (since gaps between states are always finite). Second, many of these spaces are not explored randomly [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Finally, evolutionary trajectories happen within a certain system: Darwinian evolution will act on populations of entities. Entities within the system emerge within assembly spaces [

44,

45,

46]. They are constructed from components over evolutionary timescales. These shape evolution and shift the way one should think about sequence search conditioned on the past, where the logic of assembly spaces may lead to certain types of universal convergence [

3,

46].

DNA replication can lead to the introduction of small insertions or deletions. The addition or removal of one or more base pairs

leads to insertion or deletion mutations, respectively. As shown in [

47], the loss or addition of a single nucleotide causes all of the subsequent three-letter codons to be changed [

48].These mutations are called frameshift mutations because the frame of the triplet reading is altered during translation. A frameshift mutation occurs when any number of bases

are added or deleted, except multiples of three which reestablish the initial reading frame.

Kappa-distributions emerge within the framework of statistical mechanics by maximizing the associated kappa-entropy

under the constraints of the canonical ensemble (e.g., Livadiotis G. and McComas D. J. (2009, 2014, 2023) [

1,

49,

50]). Kappa-distributions are consistent with thermodynamics; yet this fact alone cannot justify the generation and existence of these distributions. Examples of kappa-distributions include super-statistics [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56], the effect of shock waves [

57], turbulence [

58,

59,

60], the effect of pickup ions [

61,

62,

63], the pump acceleration mechanism [

64], colloidal particles [

65], and polytropic behavior [

66,

67]. For all these phenomena, there is a unique thermodynamic origin. The existence of correlations among the particles of a system does not permit the usage of the classical framework based on the Boltzmann [

68]—Gibbs [

69] (BG) entropy and Maxwell–Boltzmann (MB)[

70] canonical distribution of particle velocity (

). The thermodynamic origin of kappa-distributions has recently been connected to the new concept of “entropy defect”, proposed by Livadiotis G. and McComas D. J. (2021) [

71,

72]. Recently, Livadiotis and McComas (2023) [

1] introduced a specific algebra of the addition rule with entropy defect. The addition rule forms a mathematical Abelian group on the set of any measurable physical-quantity (including entropy), called the kapa-addition and refer to by the symbol

. The physical meaning of the kappa index can be understood through particle (subsystems) correlations: the kappa index provides a measure of the loss (for

) or gain (for

) of entropy

after the mixing of the partial systems A and B to compose the combined system [

1].

Following Livadiotis and McComas (2023) [

1], we propose a new type of DNA frameshift mutations that occur spontaneously due to information exchange between the DNA sequence of length bases (

) and the mutation sequence of length base (m), and respect the kappa-addition symbol

. We call these proposed mutations Kappa-Frameshift Background (KFB) Mutations. We find that the origin of an entropy defect is based on the interdependence of the information length systems (or their interconnectedness, that is, the dependence, or connection, of systems with a significant number of constituents (information length bases) on/with each other. The proposed KFB-mutation quantifies the correlations among the information length bases, or constituents of these systems due to information exchanges. In the presence of entropy defects the Landauer’s bound and the minimal metabolic rate for a biological system are modified. We observe that that the different

and

scales are manifested in the double appearance of the evolution of the proposed biological system through subsystems correlations. In this evolution, for short time scales and for specific values of the kappa-parameter, we can expect deterministic laws associated with a single biological polymer.

2. Kappa-Frameshift Background DNA Mutations

DNA replication can lead to the introduction of small insertions or deletions of base pairs. The addition or removal of one or more base pairs

results in insertion or deletion mutations, respectively. As shown in [

47], the loss or addition of a single nucleotide causes all of the subsequent three-letter codons to be changed [

48]. These mutations are called frameshift mutations because they alter the frame of the triplet reading during translation. Spontaneous DNA mutations occur suddenly and their origin is unknown. Such mutations, also called “background mutations”, have been reported in many organisms, such as Oenothera, maize, bread molds, microorganisms (bacteria and viruses), Drosophila, mice, humans, etc. (see Ref [

48] for details). A frameshift mutation occurs when any number of bases

are added or deleted, except multiples of three which reestablish the initial reading frame. Mutations of multiples of three nucleotides just add one or several reading frames into the sequence without altering the composition of those reading frames thereafter. It is possible, however, that the frameshift causes early termination of the translation (e.g., when a 3-nucleotide stop codon sequence is introduced). The results of frameshift mutations can, therefore, be very severe if the mutations occur early in the coding sequence. Frameshift mutations can occur at microsatellites (tandem repeats of 1–6 base pairs per repeat unit) and also at non-iterated or short repetitive sequences. Proofreading can remove insertion or deletion mutations in short repetitive and non-iterated sequences with almost the same efficiency as that for point mutations; however, it is much less efficient in removing frameshift mutations in homopolymeric runs [

47]. These mutations are removed efficiently by mismatch repair systems. The instability of microsatellite sequences is associated with many diseases, including cancer [

48].

Following Livadiotis and McComas (2023) [

1], we propose a new type of DNA frameshift mutations that occur spontaneously due to information exchanges between the DNA sequence of base lengths (

) and the mutation sequence of base lengths (m), and respects the kappa-addition symbol

. We call the propose mutations Kappa-Frameshift Background (KFB) Mutations. KFB mutations will occur when any number of bases

are added or deleted, to the initial DNA sequence

with respecting kappa-addition symbol

(except multiples of three, which will reestablish the initial reading frame). In the case of the kappa-addition of any number of bases

to the initial DNA base sequence

, we define the set of kappa-natural numbers

as the set of natural numbers

that satisfies kappa addition

law then the proposed KFB mutations are given as follows:

),

which brings the usual sum as a particular case ⊕

∞ ≡ +. The relation 1 can be expressed in the convenient product form [

1]:

),

where

is the initial length of information (string length) of the DNA or biological polymer that is being copied and

(no multiples of three) is the length of information (string length) of the mutation added to the initial base

. The κ-sum is commutative (n⊕

κm = m⊕

κn), associative (n⊕

κ(m⊕

κz) = (n⊕

κm)⊕

κz), but it is not distributive in relation to the usual multiplication (α(n⊕

κm)≠(αn⊕

καm)). The neutral element of the κ-sum is zero, n⊕

κ0 = n. Similarly, in the case of κ-deletion of any number of bases

(no multiples of three) to the initial DNA base sequence

, the proposed KFB mutation is given by the following:

Equation (3) is κ-subtraction, the inverse operation of κ-addition (1): physically, it means that some base(s) are deducted from the initial DNA or biological polymer. The κ-difference obeys n⊕κm̅=⊕κm̅⊕κn and n⊕κ(m̅⊕κz) = (n⊕κm̅)⊕κz, but α(n⊕κm̅) ≠ (αn⊕καm̅). For both κ-addition and κ-subtraction to the initial base of any bases which are multiples of three, we obtain the KFB changes of the information length of the DNA or biological polymer being copied. Then the KFB mutation just adds one or several reading frames into the sequence without altering the composition of those reading frames thereafter.

The meaning of the kappa index in the proposed KFB mutation can be understood through the subsystem (subbases) of correlations between

and

due to information exchanges within a given length of information (string length) in the DNA or biological polymer being copied. In fact, a simple relation exists between the Pearson correlation coefficient

and the kappa index

:

for subbases with

-degrees of freedom ([

71,

72,

73];[

74], Chapter 5).

The largest value of kappa,

, corresponds to DNA or biological polymer characterized by the absence of any correlations between subbases of

This condition is the frameshift mutation. The smallest possible kappa value, , corresponds to the state furthest from the ordinary frameshift mutation of a DNA or biological polymer, and is characterized by the strongest correlation between n and m due to information exchange. The parameter provides a measure of the loss ( ) or gain ( ) of information after the mixing of the partial bases and to compose the combined finial DNA or biological polymer.

3. Information Defects in the DNA or Biological Polymer

Following Ricard Solé et al. (2024) [

3], the size of sequence space

associated with a biological polymer of length

, built from a molecular alphabet

of size

(where

), is:

The space of possible proteins with a length base

of 1000 amino acids is

– a space so large that it could not be explored [

27]. The space of possible molecular configurations within an organism is astronomically large. The probability

for such a such a protein to exist in nature is

. We may assume that the biological system the is “non-ergodic” in the sense that not every part of the configuration space can be explored [

28,

29,

30]. (In statistical physics, an ergodic system is one which, over sufficiently long time-scales, explores all possible microstates that are consistent with its macroscopic properties.) Mathematically, for any physically observable

, where

is the microstate that specifies all of the system’s coordinates

, the long-time average of

converges to the ensemble average, so

In intuitive terms, an ergodic system explores (over time) all the possible ways it can exist. Given enough time, the system will visit all its available configurations or states [

3].There are several major reasons to expect convergence [

3]. Firstly, all evolutionary trajectories occur under certain generic selective constraints, such as the laws of mathematics, physics, and chemistry. These constrains should lead to universal features [

31,

32]. Secondly, many of these states are not explored randomly. Finally, evolutionary trajectories happen within a certain system: Darwinian evolution acts on populations of entities, which emerge within the system in assembly spaces [44,45, and 46].

The second law of thermodynamics states that a physical process must generate an overall increase

in the entropy of a system (

) and its environment (

):

Therefore, living systems can only perform processes that reduce entropy internally if, at the same time, they produce an even greater increase in entropy in the environment. Thus, the universal thermodynamic logic of life is that low-entropy input (“resource”) is turned into high-entropy output (“waste”), which can be expressed as:

Where

is the entropy production in the environment ,

is the amount of heat released,

is the thermal reservoir at temperature

Boltzmann’s constant.

This suggests that all life forms face the problem of maintaining low internal entropy in a race against the second law of thermodynamics.

In non-equilibrium thermodynamics [

3,

75], the rate of entropy production per unit time τ can be expressed as an integral:

for a system of volume

, with the specific entropy production rate,

, written as follows:

In Equation (12),

indicates a set of “forces" (such as temperature gradients or chemical affinities) and

is the set of conjugate fluxes (e.g., het flows, reaction rates). According to Shannon’s formula [

2,

22,

23,

24], the evolution of the base sequences of modern organisms from an unspecified base sequence resulted in a gain of information (a decrease in entropy: negative

), as follows:

For the case of writing a specific string from a set of unordered letters (

), we have:

, (where ) is the number of unique elements, or letters, in the informational system and is the length of information (the string length), that is being copied.

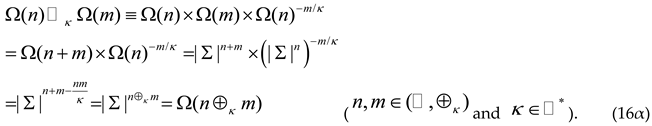

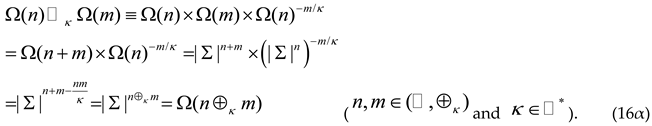

Let us now examine the possible evolutionary events resulting from the combination of the proposed KFB mutations and functional selection during biological evolution in the presence of information exchanges between the length bases. This examination involves the following steps: Firstly, we introduce the kappa-multiplication ( ) acting on the spaces of possible proteins and with a length base of and , respectively (Equation (6)), and resulting in the kappa-addition of the bases and (in the similar way that the κ-addition results with the help of the usual addition in the Equation (1); namely:

Equation (16α) shows the proposed KFB mutation space of the two possible proteins, with being a molecular alphabet of size , (where ). For instance, the Equation (16α) is the standard morphism from to . The morphism (16α) is defined with the help of the morphisms: and from to .

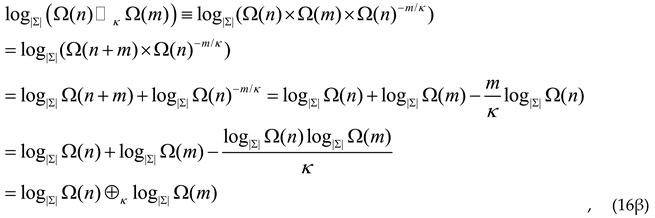

We note that the standard morphism (16α) brings the standard morphism as a particular case ⊙∞ ≡ × and ⊕∞ ≡ + for (κ→∞). Through reciprocity, the logarithm function is the standard morphisms morphism from to ;namely

which is brings the standard morphism

from

to

as a particular case ⊙

∞ ≡ × and ⊕

∞ ≡ + for (κ→∞). We impose the condition:

This implies the following restriction to the values of the κ-parameter:

Using Equation (4), we obtain the following restriction to the values of the correlation coefficient

:

for subbases with

-degrees of freedom ([

71,

72,

73];[

74],Chapter 5). The largest value of kappa,

, corresponds to DNA or biological polymer without any correlation between the subbases of information length

and

given by the Equation (5). The space of the two possible proteins (Equation (16α)) then becomes:

This is the frameshift mutation space of the two possible proteins. We may write Equation (16a) as follows:

In Equation (21), the correlation space of the two possible proteins,

and

(with a length base

and

, respectively) due to information exchanges is given by:

The κ-product (16α) is commutative Ω(n)⊙κΩ(m)=Ω(n)⊙κΩ(m)) and associative (Ω(n) ⊙κ(Ω(m)⊙κΩ(z))=(Ω(n)⊙κΩ(m))⊙κΩ(z)). The number one is the neutral element of the κ-product (Ω(n)⊙κ1=Ω(n), and this permits us to define the inverse multiplicative,1⊙κ Ω(n̅), by means of Ω(n)⊙κ(1⊙κΩ(n̅)) ≡ 1.

Similarly, the space of the two possible proteins,

and

in the case of the deletion of any number of bases

(except multiples of three) from the initial DNA sequence of base

is:

Using Equations (13)–(15), the kappa-gain of information (a decrease in kappa-entropy: negative

) of the system (DNA or biological polymer) during the proposed KFB mutations is given by:

(n,m) is the entropy of a composite system (DNA or biological polymer) with correlations between n and m ,where:

Equation (27) is the proposed entropy defect for the DNA or biological polymer.

The characteristic non-additive rule of the kappa entropy [

1] was first derived on a physical basis through the concept of entropy defect [

1]. Then, it was demonstrated that the entropy defect can lead to the generalized, kappa-associated entropy [

1].Here, we explain the origin of entropy defects based on the interdependence of information length systems (or interconnectedness of these systems: the condition whereby systems with a significant number of constituents (information length bases) dependent on, and/or are connected to, each other). The proposed KFB mutation quantifies the correlations among the information length of the bases (DNA or polymer constituents) due to information exchanges. Interdependence induces order and reduces the entropy-information in DNA or biological polymer systems thus producing entropy-information defects. Interdependence is measured through the magnitude

of the entropy-information defect, defend as:

where

(see Equation (24)) is the entropy-information of the system with correlations among its constituents (e.g., information length bases), while

denotes the entropy-information of this system if there was no correlation among the information length bases. The smallest possible kappa value,

, corresponds to the state furthest from the ordinary frameshift mutation of a DNA or biological polymer, characterized by the highest correlations between bases due to information exchange. The parameter

provides a measure of the loss (

) or gain (

) of information after the mixing of the partial bases

and

to compose the combined final DNA or biological polymer.

5. Kappa Metabolic Rate in the Presence of Information Defects

Landauer’s bound [

76] gives us the minimal energy required to perform an abstract computation and many string-writing operations, including the copying and transformation of DNA or biological polymer [

77]. We may ask if the available energy is sufficient for the string copying and processing of a very small amount of stored information. The fundamental bounds of information can be connected to metabolism via Landauer’s bound by calculating the minimal metabolic rate, W, needed to replicate genetic information for a given genome length and cellular growth rate [

3,

76,

78]. In the presence of entropy defects, Landauer’s bound is modifies due to the KFB mutations, as follows:

where

is the kappa heat released to a bath at temperature

,

is Boltzmann’s constant,

and

are the initial and final kappa system entropy, respectively. This is nothing more than the expression of the second law of thermodynamics (Equations (13–15)), where

. To write a specific string from a set of unordered letters (

), we have

and

In Equation (33), terms

,

and

are calculated from Equations (25–27);

,the number of unique elements, or letters, in the informational system (Equation(6));

is the length of information (the string length) that is being copied; and

is the length of information (the string length) of the KFB mutation. Here,

is the kappa-composed length of information (the composed string length) after the action of the KFB mutation (Equation (1)). Using Equations (25–27) and (33), the kappa-modified Landauer’s bound becomes:

where

is the heat released to a bath at temperature

independent of the kappa index, and

is the heat released to a bath at temperature

dependent of the kappa index and corresponding to the entropy-information defects of the DNA or biological polymer. The term

in Equation (36) is the correlation between the information lengths n and m due to information exchange after the action of the KFB mutation.

We can convert the kappa-modified Landauer’s bound into a kappa-modified metabolic rate

, due to the presence of entropy defects by considering how fast the information is copied. Given division time,

, of seconds, the kappa-modified minimal metabolic rate of copying is:

where

is the metabolic rate independent of the kappa index, and

is the metabolic rate dependent of the kappa index and corresponding to the entropy-information defects of the DNA or a biological polymer. Again, in limit (29), Equations (34) and (37) become

Equation (40) denotes Landauer’s bound whereas Equation 41 shows the minimal metabolic rate for a biological system if there are absolutely no correlations among the information length bases.

6. Kappa Distribution of DNA Length Bases or Biological Polymers

Starting from the connection of probability distribution

with (

)-entropy, and following Gibb’s path, we maximize the BG entropy

under the constraint of normalization

, and derive the Maxwell–Boltzmann (MB) probability distribution

. In the latter,

and

is the number of letters in the molecular alphabet. These steps can be reversed: the maximization of entropy,

, leads to the distribution,

; compared to the MB distribution ,we find

, leading to

(taking also into account that in the case of one single possibility, i.e.,

, we have

) – that is, the BG entropy. From this we derive the connection of entropy with (

)-entropic addition rule: Starting from the BG entropy applied to the two DNA systems,

and

, and their composite system,

, and noting the respective distributions

and entropies

and

, we apply, the entropic equation,

, and the property of statistical independence:

The latter is deduced from the exponential distribution function:

that maximizes this entropy and the energy summation of the DNA length bases

. Then, we obtain

, are independent – a characteristic of the MB exponential distribution function. The associated entropy of each of these systems is given by the BG formulation.

Connection of the probability distribution with ()-entropy

Following Gibb’s path, we maximize the kappa entropy

under the constraint of normalization

and derive the kappa-probability distribution:

where

,

,and

The expectation values are determined through the probability

, called “escort” [

4,

48]. In Equation (45), given that

for

. This is the kappa-related entropy, also named after Havrda, Charvát, Daróczy and Tsallis [

79,

80,

81]. In Equation (45), we use the κ-deformed exponential function and its inverse, the deformed logarithm function (Equations [

47,

48,

49,

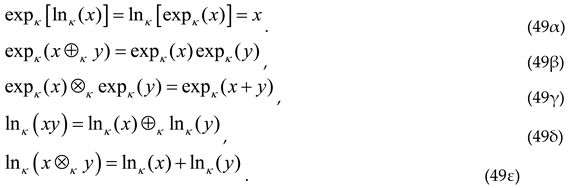

50]), to get:

with the properties of the κ-logarithm and the κ-exponential in a compact form:

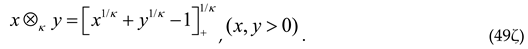

This leads us to the definition of the κ-product (⊗κ) between two real numbers x, y:

The product (49ς) is commutative (x⊗

κy = y⊗

κx) and associative (x⊗

κ(y⊗

κz)=(x⊗

κy)⊗

κz), provided x⊗

κy and y⊗

κz differ from zero and from infinity. The number one is the neutral element of the κ-product (49ς) (x⊗

κ1 = x), and this permits us to define the inverse multiplicative (⊘

κ), 1⊘

κx, by means of x⊗

κ(1⊘

κx) ≡ 1[

82].

Using the κ-logarithm and κ-exponential functions the two standard morphisms Equations (16α-β) have split into four ones. Let us denote the definition set of the generalized exponential function

by

[

82]. From Equation (49β), it comes that the generalized exponential function is morphism from

to

. But from Equation (49γ), we note that this function is also morphism from

to

. From Equation (49δ), it comes that the generalized logarithm function is morphism from

to

. But from Equation (49ε), we note that this function is also morphism from

to

[

82]. Here, we use the kappa index as a subscript to denote the deformed functions, but please note that the q-index could have been used as well (see also: Ref [

73] Appendix A for more details). We also recall the known notation (49α) of deformed exponential/logarithm functions:

which constitutes the multiplicity

. This multiplicity (or statistical weight) is the space of possible molecular configurations of molecules within that biological system. We observe that the multiplicity

becomes a thermodynamic quantity independent of the kappa index. In particular, given the probability distribution

, the statistical definition of this entropy, is formulated by:

expressed in terms of the kappa κ-parameter (mostly used by the space-science community, or equivalently, the q-index (mostly used by the community of no-extensive statistical mechanics [

74]):

The BG entropy for

or

is:

Connection of ()-entropy with a generalized addition rule

Starting from Equation (45), we calculate the information function

where

is the kappa index transformation

, and

is the number of letters in the molecular alphabet. Applied again to the two independent systems of the bases

and

and their kappa-composite system, base

, we find:

or

Equations (57) and (58) lead to the standard form of entropy-information defects for a DNA or biological polymer, as in Ref [

1]:

where

and

Then, after the kappa-index transformation

:

in Equation (61), the entropy defects in the standard form (Refs [

1]) can takes the form of the proposed entropy defects (Equation (27)). Similarly, by applying the kappa-index transformation

in Equation (27), the entropy defects take the standard form (Equation (61)), as in Refs [

1]. The reverse process can be found by starting from this generalized addition rule and seeking the entropic function that obeys this rule; this has been already shown in several earlier publications (e.g. [

1]).

7. Discussion

Following Ref [

3], the required metabolic rate for information copying alone is calculated from Equation (6), with the key parameters being the number of letters in the molecular alphabet

, the length of the composite genome (

) after the kappa frameshift mutation, (with

and

m being the length of the genome and the mutation length, respectively), and the time to copy the information (

). For

letters, at a typical division time

and a Typical Genome Length (TGL) of

, Equation (6) gives an ordinary Typical Bacterial Metabolic Rate (TBM) of

The smallest possible kappa value,

, (

: degrees of freedom ([

71,

72];[

74], Chapter 5) corresponds to the state furthest from the ordinary frameshift mutation of a DNA or biological polymer, characterized by the highest correlation between bases. Using the

κmin value, Equation (63) becomes:

In the MB probability distribution

for a DNA or biological polymer, entropy is zero

only when a specific information string is written from a set of unordered letters, (

). The probability value for such an unordered information string is

. Furthermore, in the MB statistical mechanics for a specific information string from a set of ordered letters (

), there is no preference for a specific sequence: if

, different DNA sequences are equally possible and the actual DNA sequence has only a probability

(where

is the number of bases (ordered letters) in the DNA sequence, ranging from one million in bacteria to billions in many animals and plants). For example, the space of possible proteins

with a base length

of 1000 amino acids is

– a space so large that it could never be explored in our universe [

27]. The space of possible molecular configurations within an organism is astronomically larger. The probability

of such a protein (ordered information string) to exist in nature is

. The requirements of longer time and a larger number of individuals are even more conducive to the observation of deterministic laws associated with the base length

. The evolutionary fitness of organisms relates to the progressive reduction of the entropy production rate. This, and the Boltzmann’s ergodic principle, allow us to consider organisms as evolving chemical entities (Sabater 2006, 2009[

2,

4]). Accordingly, the time-average state of a single individual over a long period (evolutionary time) coincides with the average state of a sufficiently large number of individuals for shorter time periods [

5]. We note that Sabater (2009[

5]) worked with an alternative theory with biological time arrows, showing that deterministic behavior of a biological system can arise.

Let us now examine the evolutionary events that could result from the combination of functional selection during biological evolution and information exchanges between the base lengths of biological polymers, represented by the kappa parameter. For DNA or biological polymer with the kappa-probability distribution (Equation (46)) derived from the maximized kappa entropy (Equation (45)) under the constraint of normalized

, we observe that the different

and

scales in Equations (45) and (46) are manifested in the double evolutionary emergence of the proposed biological polymers through correlations between its bases. For specific values of the kappa parameter, deterministic laws associated with a single biological polymer can be expected for short timescales. Thus, for the kappa-probability distribution, we have the following short-timescale possibilities for an individual:

Equation (66) measures the loss (for

) or gain (for

) of information. In Equation (66), for

and non-zero integer (ordered letters

), it is

. Therefore, for kappa-entropy, we find the following short-timescale possibilities for a single biological polymer:

In Equation (67), for , , and non-zero integer (ordered letters ), it is .

Let us consider the example of the state characterized by

, that is, the strongest correlation between bases due to information exchange. The space of possible final proteins

with a length base

of 1000 amino acids is:

The final protein entropy

. From this, we obtain entropy changes (gain of information) of the following value:

with

for equal final and initial base length of amino acids (

). We call these proposed changes

iso-order n changes. These changes are characterized by the parameters:

The space of possible final proteins with a base length of 1000 amino acids is 1. An initial space of a magnitude as large as has thus now collapsed to the one final possibility: . The probability for such a protein (ordered information string) final state to exist in nature is now one .

Let us now consider another example for (

) state characterized by the highest correlations between bases due to information exchanges. By writing a specific initial information string from a set of unordered letters for kappa values (

,

) we have:

We then obtain the entropy changes (information gain):

where

is the final entropy of the “mathematical” protein Equation (72) is the

iso-entropic process for a given “mathematical’’ protein, and is adiabatic and reversible [

83,

84,

85,

86], with equal initial and final probability (that is,

).

Furthermore, we have the order n changes:

. It seems that order

emerges spontaneously from the unordered initial information string. This emergence of order

may relate to the quantum self-organization process (see Refs [

33,

87,

88,

89,

90] for details).

Using Equations (37) and (41) the

iso-entropic changes for the proposed “mathematical’’ protein yield to the zero kappa-metabolic rate. This implies that, at this optimum state (

), to protect itself from damage it cannot endure, the “mathematical” protein must not waste energy (produce entropy) in reactions. We call this state of the “mathematical” protein the kappa-functional optimum state. This state is given by Equation (72). In nature, it may be possible for a real protein to approximate the kappa-functional optimum state with increasing correlation between its parts:

Due to the strongest correlation between its parts, such a protein would need to waste much less energy (produce less entropy) in reactions and would be less susceptible to damage than the classical information theory predicts.

8. Conclusion

Following Livadiotis G. and McComas D. J, (2023) [

1], we propose a new type of DNA frameshift mutations: Kappa-Frameshift Background (KFB) mutations. KFB mutations occur spontaneously due to information exchange between the DNA sequence of length base (

) and the mutation sequence of length base (m), and respect the kappa-addition symbol

. KFB mutations occur when any number of

bases are added or deleted to the initial DNA sequence of

bases. This repeats the kappa-addition symbol

, except in the case of multiples of three, which reestablish the initial reading frame. In the proposed KFB mutation, the kappa index can be understood through the subsystem (subbase) of information length correlation between

and

due to information exchange within the given length of DNA or biological polymer (the string length) that is being copied.

We find that entropy defects originate in the interdependence of information length systems (or their interconnectedness: the state at which systems with a significant number of constituents (information length bases) depend on, or are connected with, each other) by the proposed KFB mutations. In general, interdependence induces order in the systems involved (DNA or biological polymers) and reduces their entropy-information, thus producing entropy-information defect.

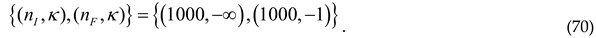

In the presence of entropy defects, the Landauer’s bound and minimal metabolic rate for a biological system is modified. We observe that that the different and scales in Equations (45) and (46) are manifested in the double evolutionary emergence of proposed biological polymers due to subsystems correlations. In this process, for specific values of the kappa parameter, we can expect deterministic laws associated with a single biological polymer for short timescales. We find that the possible evolutionary events resulting from the combined effects of functional selection during biological evolution and information exchange between the length bases of the biological polymer are represented by the kappa parameter. We also identify iso-order n changes characterized by the parameters (70). Using a proposed “mathematical” protein, we find that the iso-entropic changes this protein yield to the zero kappa-metabolic rate. This implies that, at the optimum state ( ), to protect itself from damage it cannot endure, the “mathematical” protein must not waste energy (produce entropy) in reactions. We call this state of the “mathematical” protein the kappa-functional optimum state (Equation (72)). In nature, with increasing correlation between its parts, a real protein may approximate the kappa-functional optimum state. Due to the strongest correlation between its parts, such a protein would waste much less energy (produce less entropy) in reactions, and would be less susceptible to damage, than the classical information theory predicts.