Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Definition of Terms

3. Methodology

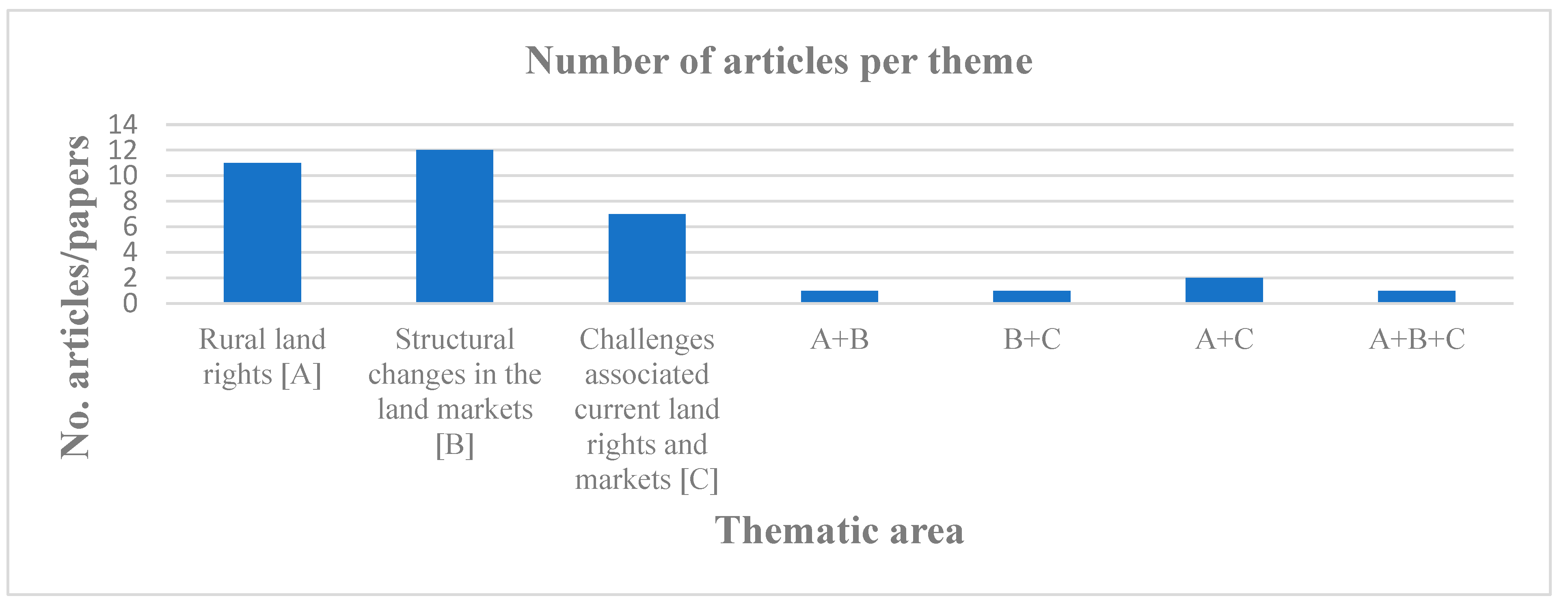

4. Results Based on Thematic Areas

4.1. Status of Rural Land Rights

4.2. Structural Changes in the Land Markets and Rights

4.3. Challenges Associated with Current Land Rights

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Rural Land Rights

5.2. Land Markets and Structural Transformation

5.3. Challenges Associated with Current Land Rights

5.4. Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusions/Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Tatwangire, A., Holden, S.T. 2013. Land Tenure Reforms, Land Market Participation and the Farm Size — Productivity Relationship in Uganda. In: Holden, S.T., Otsuka, K., Deininger, K. (eds) Land Tenure Reform in Asia and Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, London. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2023. Sustainable Land Management in Practice. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/4/i1861e/i1861e.pdf.

- McDonald, E. 2011. Women and tenure transition: An examination of land access and gendered land rights in Kanungu District, Uganda. PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal, 5(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development. 2013. The Uganda National Land Policy. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/uga163420.pdf.

- World Population Prospects 2022: The 2022 Revision. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2022. https://population.un.org/wpp.

- Kyaddondo, B. 2012. Uganda population stabilization report. Population Trends and Policy Options in Selected Developing Countries, 202. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258207258_Population_Trends_and_Policy_Options_in_Selected_Developing_Countries_2012_edited_by_Dr_Joe_Thomas.

- World Bank 2024. Health Nutrition and Population Statistics: Population Estimates and Projections. Retrieved from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/health-nutrition-and-population-statistics: -population-estimates-and-projections.

- World Bank 2018. Making Farming More Productive and Profitable for Ugandan Farmers. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/uganda/publication/making-farming-more-productive-and-profitable-for-ugandan-farmers.

- Stanley, V., & Lisher, J. 2023. Why Land and Property Rights Matter for Gender Equality. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Stanley%2C+V.%2C+%26+Lisher%2C+J.+%282023%29.+Why+Land+and+Property+Rights+Matter+for+Gender+Equality&btnG=.

- Rugadya, M. A. 2009. Escalating land conflicts in Uganda. A Review of Evidence from Recent Studies and Surveys. The International Republican Institute, The Uganda Round Table Foundation. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Rugadya%2C+M.+A.+%282009%29.+Escalating+land+conflicts+in+Uganda.+A+Review+of+Evidence+from+Recent++Studies+and+Surveys.+The+International+Republican+Institute%2C+The+Uganda+Round+Table+Foundation.&btnG=.

- Nkuba, M. R., Chanda, R., Mmopelwa, G., Adedoyin, A., Mangheni, M. N., Lesolle, D., & Kato, E. 2020. Barriers to climate change adaptation among pastoralists: Rwenzori Region, Western Uganda. African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Doss, C., Meinzen-Dick, R., & Bomuhangi, A. 2014. Who owns the land? Perspectives from rural Ugandans and implications for large-scale land acquisitions. Feminist economics, 20(1), 76-100. [CrossRef]

- Stickler, M. M. 2012. Governance of large-scale land acquisitions in Uganda: The role of the Uganda Investment Authority. In International Conference on Global Land Grabbing II (pp. 17-19). https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Stickler%2C+M.+M.+%282012%2C+October%29.+Governance+of+large-scale+land+acquisitions+in+Uganda%3A+The+role++of+the+Uganda+Investment+Authority.+In+International+Conference+on+Global+Land+Grabbing+II+%28pp.+17-19%29.&btnG=.

- Obaikol, E. 2014. Draft final report on the implementation of the land governance assessment framework in Uganda. Washington, D, C: World Bank Group. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Obaikol%2C+E.+%282014%29.+Draft+final+report+on+the+implementation+of+the+land+governance+assessment++framework+in+Uganda.+Washington%2C+D%2C+C%3A+World+Bank+Group.&btnG=.

- Mabikke, S. B. 2016. Historical continuum of land rights in Uganda: a review of land tenure systems and approaches for improving tenure security. Journal of Land and Rural Studies, 4(2), 153-171. [CrossRef]

- Bagonza, R. A. 2014. Gender and vulnerability to disasters and disaster/climate risk management in Uganda: A participatory characterization. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Bagonza%2C+R.+A.+%282014%29.+Gender+and+vulnerability+to+disasters+and+disaster%2Fclimate+risk++management+in+Uganda%3A+A+participatory+characterisation.&btnG=.

- Deininger, K., & Enemark, S. 2010. Land governance and the millennium development goals. In Innovations in land rights recognition, administration, and governance (pp. 1-11). World Bank Publications. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Deininger%2C+K.%2C+%26+Enemark%2C+S.+%282010%29.+Land+governance+and+the+millennium+development+goals.++In+Innovations+in+land+rights+recognition%2C+administration%2C+and+governance+%28pp.+1-11%29.+World+Bank+Publications.+&btnG=.

- Ogwang, T., & Vanclay, F. 2021. Resource-financed infrastructure: thoughts on four Chinese-financed projects in Uganda. Sustainability, 13(6), 3259. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development. 2023. National budget speech for FY 2023/24. https://budget.finance.go.ug/sites/default/files/National%20Budget%20docs/NATIONAL%20BUDGET%20SPEECH%20FOR%20FY%202023-24.pdf.

- World Bank. 2019. Ugandan government steps up efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change. World Development Indicators. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/05/31/ugandan-government- steps-up-efforts-to-mitigate-and-adapt-to-climate-change.

- Rugadya, M. A. 2020. Land tenure as a cause of tensions and driver of conflict among mining communities in Karamoja, Uganda: Is secure property rights a solution? Land Use Policy, 94, 104495. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2021. Uganda economic update: Uganda can achieve greener, resilient, and inclusive growth by investing in sustainable land management. World Development Indicators. https://uganda.un.org/en/sdgs/13.

- Zhang, Y. 2018. Rural Land System and Rights. In: Insights into Chinese Agriculture. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Wineman, A., & Liverpool-Tasie, L. S. 2017. Land markets and the distribution of land in northwestern Tanzania. Land Use Policy, 69, 550-563. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.043.

- Giddings, S. W. 2009. The land market in Kampala, Uganda, and its effect on settlement patterns. International Housing Coalition, Washington DC, USA, 33. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Giddings%2C+S.+W.+%282009%29.+The+land+market+in+Kampala%2C+Uganda+and+its+effect+on+settlement++patterns.+International+Housing+Coalition%2C+Washington+DC%2C+USA%2C+33.&btnG=.

- Wallace, J., & Williamson, I. 2006. Building land markets. Land use policy, 23(2), 123-135. [CrossRef]

- Jin, S., & Deininger, K. 2009. Land rental markets in the process of rural structural transformation: Productivity and equity impacts from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(4), 629-646. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, J., & Yang, Y. (2018). Strategic adjustment of land use policy under the economic transformation. Land use policy, 74, 5-14. [CrossRef]

- Bazaara, N. 2002. Politics, legal land reform and resource rights in Uganda. Centre for Basic Research, Kampala. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Bazaara%2C+N.+%282002%29.+Politics%2C+legal+land+reform+and+resource+rights+in+Uganda.+Centre+for+Basic++Research%2C+Kampala.+Search+in.&btnG=.

- Kamusiime, H. R., Obaikol, E., & Rugadya, M. 2005. Gender and the Land Reform Process in Uganda, Assessing Gains and Losses for Women in Uganda. Land research series, (2). https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Kamusiime%2C+H.+R.%2C+Obaikol%2C+E.%2C+%26+Rugadya%2C+M.+%282005%29.+Gender+and+the+Land+Reform+Process+in++Uganda%2C+Assessing+Gains+and+Losses+for+Women+in+Uganda.+Land+research+series%2C+%282%29.&btnG=.

- Rugadya, M. A., Nsamba-Gayiiya, E., & Kamusiime, H. 2008. Northern Uganda land study. Analysis for Post Conflict Land Policy and Land Administration: A Survey of IDP Return and Resettlement Issues and Lesson from Acholi and Lango Regions. Kampala, Uganda, World Bank. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Rugadya%2C+M.+A.%2C+NsambaGayiiya%2C+E.%2C+%26+Kamusiime%2C+H.+%282008%29.+Northern+Uganda+land+study.++Analysis+for+Post+Conflict+Land+Policy+and+Land+Administration%3A+A+Survey+of+IDP+Return+and+Resettlement+Issues+and+Lesson+from+Acholi+and+Lango+Regions.+Kampala%2C+Uganda%2C+World+Bank.&btnG=.

- Gondo, T., & Kyomuhendo, V. 2011. Between reality and rhetoric in land conflicts. An anecdotal anatomy of the lawful, bonafide occupants and customary tenants in Kyenjonjo district, Uganda. Land Tenure Journal, (1). https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Gondo%2C+T.%2C+%26+Kyomuhendo%2C+V.+%282011%29.+Between+reality+and+rhetoric+in+land+conflicts.+An++anecdotal+anatomy+of+the+lawful%2C+bonafide+occupants+and+customary+tenants+in+Kyenjonjo+district%2C+Uganda.+Land+Tenure+Journal%2C+%281%29.&btnG=.

- Bomuhangi, A., Doss, C., & Meinzen-Dick, R. 2011. Who owns the land? perspectives from rural Ugandans and implications for land acquisitions. IFPRI-Discussion Papers, (1136).https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Bomuhangi%2C+A.%2C+Doss%2C+C.%2C+%26+MeinzenDick%2C+R.+%282011%29.+Who+owns+the+land%3F+perspectives+from++rural+Ugandans+and+implications+for+land+acquisitions.+IFPRI-Discussion+Papers%2C+%281136%29.&btnG=.

- Doss, C., Truong, M., Nabanoga, G., & Namaalwa, J. 2012. Women, marriage, and asset inheritance in Uganda. Development Policy Review, 30(5), 597-616. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R. H., Spichiger, R., Alobo, S., Kidoido, M., Bashaasha, B., & Munk Ravnborg, H. 2012. Land tenure and economic activities in Uganda: A literature review (No. 2012: 13). DIIS Working Paper. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/122257.

- Gärber, B. 2013 Women’s land rights and tenure security in Uganda: Experiences from Mbale, Apac and Ntungamo. Stichproben. Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastu dien, 24,32.https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=G%C3%A4rber%2C+B.+%282013%29.+Women%E2%80%99s+land+rights+and+tenure+security+in+Uganda%3A+Experiences+from+Mbale%2C++Apac+and+Ntungamo.+Stichproben.+Wiener+Zeitschrift+f%C3%BCr+kritische+Afrikastu+dien%2C+24%2C+1-32.+&btnG=.

- The Republic of Uganda. (2008). The National Land Use Policy. available on; https://mlhud.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/National-Land-use-Policy.pdf./.

- Deininger, K.; Ali, D. A.; Yamano, T. 2008. Legal Knowledge and Economic Development: The Case of Land Rights in Uganda. Land Economics, 84(4), 593–619. [CrossRef]

- Luyombya, D., & Obbo, D. F. 2013. The state of digitization of the land registry operations in Uganda. Journal of the South African Society of Archivists, 46, 25-25. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jsasa/article/view/100086.

- Deininger, K. W., & Mpuga, P. 2003. Land markets in Uganda: Incidence, impact, and evolution over time. [CrossRef]

- Baland, J. M., Gaspart, F., Place, F., & Platteau, J. P. 2000. The distributive impact of land markets in Central Uganda. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Baland%2C+J.+M.%2C+Gaspart%2C+F.%2C+Place%2C+F.%2C+%26+Platteau%2C+J.+P.+%282000%29.+The+distributive+impact+of+land++markets+in+Central+Uganda.+&btnG=.

- Mwesigye, F., Matsumoto, T., & Otsuka, K. 2017. Population pressure, rural-to-rural migration and evolution of land tenure institutions: The case of Uganda. Land Use Policy, 65, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, M. 2014. Renegotiating customary tenure reform–Land governance reform and tenure security in Uganda. Land use policy, 39, 292-300. [CrossRef]

- Chalin, V., Golaz, V., & Médard, C. 2015. Land titling in Uganda crowds out local farmers. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 9(4), 559-573. [CrossRef]

- Ainembabazi, J. H., & Angelsen, A. 2016. Land inheritance and market transactions in Uganda. Land Economics, 92(1), 28-56. [CrossRef]

- Deininger, Klaus and Xia, Fang and Savastano, Sara and Savastano, Sara. 2015. Smallholders? Land Ownership and Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: A New Landscape?World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7285, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2613753.

- Kijima, Y., & Tabetando, R. 2020. Efficiency and equity of rural land markets and the impact on income: Evidence in Kenya and Uganda from 2003 to 2015. Land Use Policy, 91, 104416. [CrossRef]

- Mugambwa, J. 2007. A comparative analysis of land tenure law reform in Uganda and Papua New Guinea. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Mugambwa%2C+J.+%282007%29.+A+comparative+analysis+of+land+tenure+law+reform+in+Uganda+and+Papua++New+Guinea.&btnG=.

- Nakayi, R., & Twesiime-Kirya, M. 2017. The Legal Jurisprudential Analysis Report on Land Justice in Uganda. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Nakayi%2C+R.%2C+%26+TwesiimeKirya%2C+M.+%282017%29.+The+Legal+Jurisprudential+Analysis+Report+on+Land++Justice+in+Uganda.&btnG=.

- Amone, C., & Lakwo, C. 2014. Customary land ownership and underdevelopment in Northern Uganda. International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research, 2(3), 117-125. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Amone%2C+C.%2C+%26+Lakwo%2C+C.+%282014%29.+Customary+land+ownership+and+underdevelopment+in+Northern++Uganda.+International+Journal+of+Social+Science+and+Humanities+Research%2C+2%283%29%2C+117-125.&btnG=.

- Holden, S. and Ghebru, H. 2016. Land Rental Market Legal Restrictions in Rural Ethiopia. Land Economics, 92(3), pp. 536-557. [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, A. H., Jack, C., & McCarry, R. 2021. The case for long-term land leasing: a review of the empirical literature. Land, 10(3), 238. [CrossRef]

- Carter, M. R., Wiebe, K. D. and Blarel, B. 1990. Land Titles, Tenure Security, and Agricultural Productivity: Theoretical Issues and an Econometric Analysis of Mediating Factors in Njoro Division, Kenya. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Carter%2C+M.+R.%2C+Wiebe%2C+K.+D.+and+Blarel%2C+B.+%281990%29.+Land+Titles%2C+Tenure+Security%2C+and+Agricultural++Productivity%3A+Theoretical+Issues+and+an+Econometric+Analysis+of+Mediating+Factors+in+Njoro+Division%2C+Kenya&btnG=.

- Naybor, D. 2015. Land as a fictitious commodity: the continuing evolution of women's land rights in Uganda. Gender, Place & Culture, 22(6), 884-900. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K., Agard, J., Liu, J., de Aguiar, A. P., Armenteras, D., Boedhihartono, A. K., ... & Xue, D. 2019. Pathways towards a sustainable future. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Chan%2C+K.%2C+Agard%2C+J.%2C+Liu%2C+J.%2C+de+Aguiar%2C+A.+P.%2C+Armenteras%2C+D.%2C+Boedhihartono%2C+A.+K.%2C+...+%26+Xue%2C+D.++%282019%29.+Pathways+towards+a+sustainable+future.&btnG=.

- Petracco, C. K., & Pender, J. 2009. Evaluating the impact of land tenure and titling on access to credit in Uganda (Vol. 853). Intl Food Policy Res Inst. https://books.google.hu/books?hl=en&lr=&id=IKCCDuC0XQAC&oi=fnd&pg=PP5&dq=Petracco,+C.+K.,+%26+Pender,+J.+(2009).+Evaluating+the+impact+of+land+tenure+and+titling+on+access+to++credit+in+Uganda+(Vol.+853).+Intl+Food+Policy+Res+Inst.+&ots=repNCrWGI8&sig=Er3zBNeUvhjEMMVTvzHwpdugBHQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Note, C. 2021. African Development Bank Group. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Note%2C+C.+%282021%29.+African+Development+Bank+Group.&btnG=.

- Nkunyingi, F. 2016. The Geopolitics of Access to Oil Resources. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Nkunyingi%2C+F.+%282016%29.+The+Geopolitics+of+Access+to+Oil+Resources.&btnG=.

- Byamugisha, F. F., & Kampala, U. 2014. Land reform and investments in agriculture for socio-economic transformation of Uganda. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Byamugisha%2C+F.+F.%2C+%26+Kampala%2C+U.+%282014%29.+Land+reform+and+investments+in+agriculture+for+socio-+economic+transformation+of+Uganda.&btnG=.

- Dmitry, D., Pozhidaev. 2021. Thirty-Five Years of Reforms in Uganda: Is the Glass Half Full or Half Empty? [CrossRef]

- Lastarria-Cornhiel, S. 2003. Uganda country brief: Property rights and land markets. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Lastarria-Cornhiel%2C+S.+%282003%29.+Uganda+country+brief%3A+Property+rights+and+land+markets.&btnG=.

- Brunton, K. A. 2015. The Decentralization of Power and Institutional Adaptations: Decentralized Land Reform in Kayunga, Uganda (Doctoral dissertation, Université d'Ottawa/University of Ottawa). https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Brunton%2C+K.+A.+%282015%29.+The+Decentralization+of+Power+and+Institutional+Adaptations%3A++Decentralized+Land+Reform+in+Kayunga%2C+Uganda+%28Doctoral+dissertation%2C+Universit%C3%A9+d%27Ottawa%2FUniversity+of+Ottawa%29.+&btnG=.

| Criteria for inclusion or exclusion | Number of articles included: 28 | Number of articles dropped: 65 | Justification of criteria used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Publication | Between 1995 and 2023 | Before 1995 | This database would give a good historical perspective on the land rights, markets, and challenges after the promulgation of the current constitution of Uganda. |

| Language of publication | Only those in English | Not in English | Most of the impactful research in this area is published in the English language |

| Publication theme | Land rights, land markets, land structural transformation | Keywords in the title or abstract missing at least one of these: Land rights, land markets, land structural transformation, and challenges | To be able to cover the content scope for this review |

| Availability of the article online | Available | Not available | Lack of access to non-open-source literature |

| Study location | Uganda | Outside Uganda | To maintain the geographical scope of interest |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).