3.1. Validation of the SI-Based Template Library

The validation of the SITL involved implementing and integrating the Euler system of differential equations using standard C++20. This system is a core component of the guidance system for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), drones, and various spacecraft.

Implementations used the Runge-Kutta method [

33]. The proposed SITL facilitated writing clearer code and provided enhanced formal verification during compile time.

#define VX AngularVelocityX<double>

#define VY AngularVelocityY<double>

#define VZ AngularVelocityZ<double>

#define AX AngularAccelerationX<double>

#define AY AngularAccelerationY<double>

#define AZ AngularAccelerationZ<double>

using namespace SI;

using namespace Geometry;

using namespace Mechanics;

AngularVelocityX<double> wx0(0.);

AngularVelocityY<double> wy0(0.);

AngularVelocityZ<double> wz0(0.);

MomentOfInertia<double> Ixx = 10, Iyy = 20, Izz = 30;

MomentOfForceX<double> Mx = 2;

MomentOfForceY<double> My = 4;

MomentOfForceZ<double> Mz = 6;

AX<double> E1(Time<double> t, VX wx, VY wy, VZ wz)

{

return (Mx - (Izz - Iyy) * wy * wz) /Ixx;

}

AY<double> E2(Time<double> t, VX wx, VY wy, VZ wz) {

return ((My - (Ixx - Izz) * wz * wx) / Iyy);

}

AZ<double> E3(Time<double> t, VX wx, VY wy, VZ wz) {

return (Mz - (Iyy - Ixx) * wx * wy) / Izz;

}

Time<double> T0 = 0.0, T_end = 10.0, step = 0.5, tis;

typedef AX<double>(*EFX)(Time<double>, VX wx, VY wy, VZ wz);

typedef AY<double>(*EFY)(Time<double>, VX wx, VY wy, VZ wz);

typedef AZ<double>(*EFZ)(Time<double>, VX wx, VY wy, VZ wz);

void rungeKutta4SI(EFX fx, EFY fy, EFZ fz )

{

Dimensionless<double> ndl = ((T_end - T0) / step);

int n = int(ndl.getValue());

std::vector<SI::Time<double>> t(n + 1);

t[0] = T0;

std::size_t nefv =3;

vector <VX> wx(n+1);

vector <VY> wy(n+1);

vector <VZ> wz(n+1);

wx[0] = wx0; wy[0] = wy0; wz[0] = wz0;

AVX k1x, k2x, k3x, k4x, wx_;

AVY k1y, k2y, k3y, k4y, wy_;

AVZ k1z, k2z, k3z, k4z, wz_;

//++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i)

{

k1x = step * fx(t[i], wx[i], wy[i], wz[i]);

k1y = step * fy(t[i], wx[i], wy[i], wz[i]);

k1z = step * fz(t[i], wx[i], wy[i], wz[i]);

tis= t[i]+step/2.; wx_= wx[i]+k1x/2.;

wy_ = wy[i]+k1y/2.; wz_=wz[i]+k1z/2.

k2x =step*fx(tis, wx1, wy1, wz1);

k2y =step*fy(tis, wx1, wy1, wz1);

k2z =step*fz(tis, wx1, wy1, wz1);

wx_= wx[i]+k2x/2.; wy_= wy[i]+k2y/2.;

wz_= wz[i]+k2z/2.;

k3x =step*fx(tis, wx_, wy_, wz_);

k3y =step*fy(tis, wx_, wy_, wz_);

k3z =step*fz(tis, wx_, wy_, wz_);

tis= t[i]+step; wx_= wx[i] + k3x;

wy_= wy[i] + k3y; wz_= wz[i] + k3z

k4x = step * fx(tis, wx_, wy_, wz_);

k4y = step * fy(tis, wx_, wy_, wz_);

k4z = step * fz(tis, wx_, wy_, wz_);

wx[i+1]=wx[i]+(k1x+2*k2x+2*k3x+k4x)/6;

wy[i+1]=wy[i]+(k1y+2*k2y+2*k3y+k4y)/6;

wz[i+1]=wz[i]+(k1z+2*k2z+2*k3z+k4z)/6;

t [i+1]=t[i] + step;

}

}

The validation of the SITL confirms its accuracy and reliability for use in various applications.

3.2. Usage SITL for CPS Formal Verification

The proposed SITL was used to verify CPS software. According to

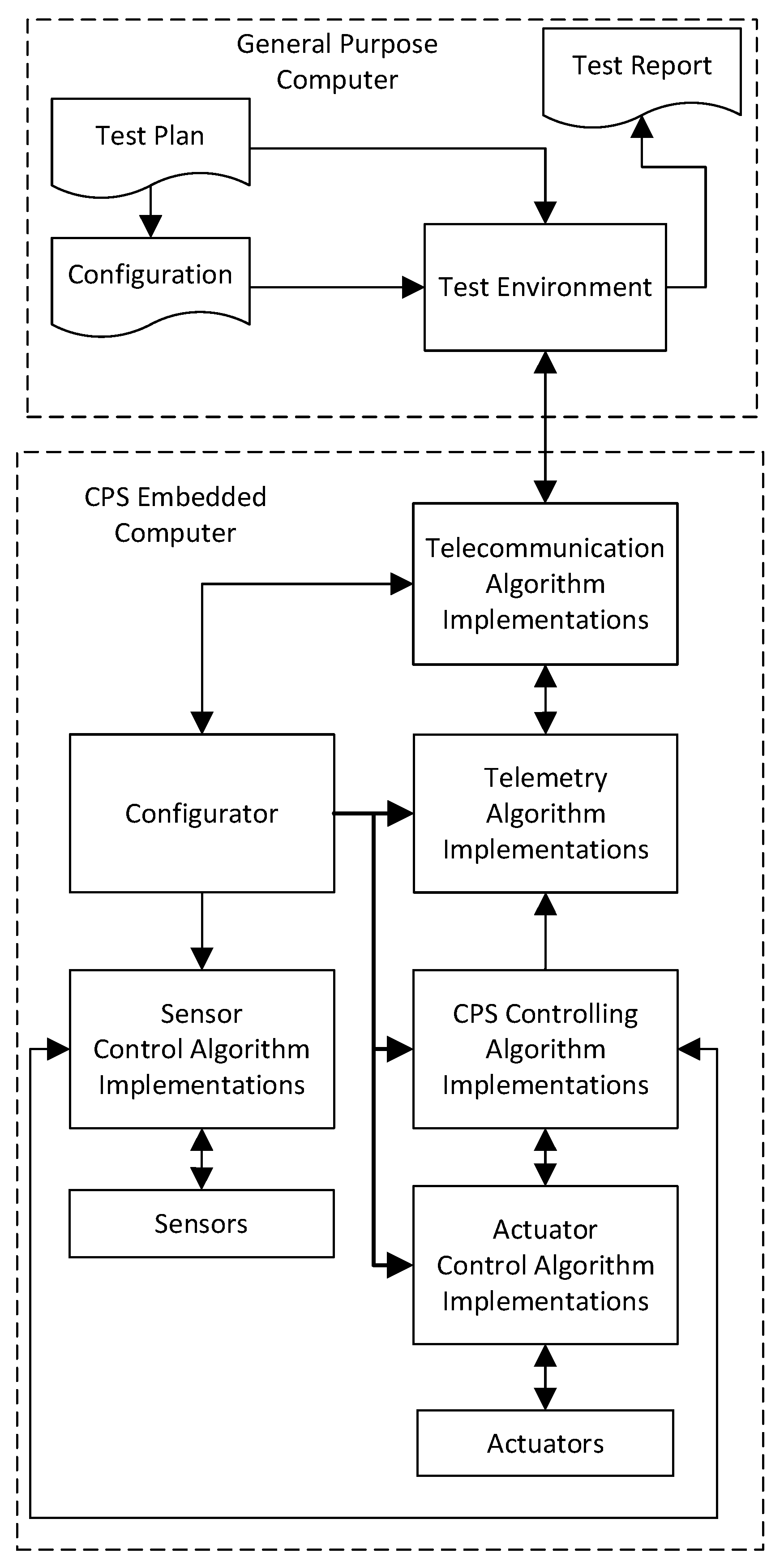

Figure 3, CPS software verification involves a General Purpose Computer with a Test Environment. Following the Test Plan and CPS software configuration, this environment sends test data and configurations to the CPS. The configuration includes embedded algorithms and defines the primary tasks of the CPS, allowing for the modification of algorithms based on the available onboard sensors and actuators. The Test Environment sends configuration and test data to the CPS, while the CPS transmits telemetry back to the Test Environment and Earth.

CPS software includes six sets of algorithms.

3.2.1. Configurator Algorithms

Configurator Algorithms (CA) are pivotal in managing and adapting embedded algorithms within a CPS based on specific configurations and requirements. They provide the flexibility to modify and update the system’s functionality by selecting and replacing embedded algorithms.

CA enables the selection of appropriate embedded algorithms based on predefined configuration settings. This selection process ensures that the correct algorithms are applied for the current operational context, whether for data processing, control, or communication tasks. For example, in a satellite mission, configurator algorithms might choose between different image processing algorithms based on the type of observations being made.

One of the key strengths of CA is its ability to reconfigure the CPS dynamically. This means the system can adapt to changing conditions or requirements by loading and activating different algorithms without restarting or redeploying the entire system. For instance, in autonomous vehicles, configurator algorithms could switch between different navigation algorithms depending on the vehicle’s operating environment.

CA facilitates the replacement of existing algorithms with new or updated ones downloaded from the Test Environment (Earth). This capability allows for continuous improvement and adaptation of the system’s functionality, ensuring it remains up-to-date with the latest enhancements or fixes.

CA manages and applies configuration settings that determine which algorithms are used. This includes handling various parameters and options that affect algorithm behavior. CA ensures that the system operates according to the specified requirements and optimizes performance based on the current operational goals.

CA supports version control by ensuring that the correct versions of algorithms are used and are compatible with the existing system components. They help prevent conflicts and ensure that updates or replacements do not disrupt system stability or functionality. Version control mechanisms might ensure new algorithms are compatible with the existing hardware and software infrastructure.

CA performs testing and validation before applying new or updated algorithms to ensure they meet the required performance and reliability standards. This may involve running simulations or conducting preliminary tests to verify that the new algorithms operate correctly and integrate seamlessly with the existing system.

Integrating SITL with CA enhances their capability to manage algorithms that involve physical quantities and units. SITL ensures that any algorithms selected or replaced adhere to dimensional and orientation standards, providing a consistent and reliable framework for algorithm functionality. This integration also supports formal verification of algorithms to ensure they conform to SI units and maintain accuracy across different configurations.

CA includes mechanisms for error handling and rollback in case of issues during algorithm replacement or configuration changes. If a new algorithm fails to perform as expected, the system can revert to a previous stable version, ensuring continuity and minimizing disruptions.

CA optimizes system performance by selecting algorithms that best match the current operational conditions. This includes adjusting computational resources and tuning algorithm parameters for optimal efficiency and effectiveness.

In summary, configurator algorithms are crucial for managing and adapting embedded algorithms in a Cyber-Physical System. They enable dynamic reconfiguration, support algorithm replacement from the Test Environment, and ensure the system operates according to specified configurations. By integrating SITL, configurator algorithms can achieve greater accuracy and consistency in handling physical quantities, enhancing the overall reliability and performance of the CPS.

3.2.2. Telecommunication Algorithms

Telecommunication Algorithms (TA) are crucial in managing and facilitating communication between CPS and their Test Environment, often located on Earth. They ensure the effective exchange of information necessary for configuring, testing, and monitoring CPS operations.

TA handles the reception of configuration data sent from Earth to the CPS. This data may include parameters for system setup, operational commands, and updates. For example, configuration data might specify orbital adjustments, sensor calibrations, or operational modes in a satellite mission.

TA is responsible for transmitting test data from the CPS to Earth. This data can be used to validate the system's performance, conduct experiments, or assess the results of various tests.

TA manages the transmission of telemetry information back to Earth, providing real-time updates on the CPS’s status and performance. This information typically includes data from sensors, system health indicators, and operational logs. Effective telemetry ensures mission control on Earth clearly and accurately understands the CPS’s condition and activities.

To efficiently transmit large volumes of data, TA incorporates data coding. This helps reduce the amount of data that must be sent, optimize bandwidth usage, and minimize transmission delays. Ensuring data integrity during transmission is critical.

TA includes error detection and correction mechanisms to identify and rectify any data corruption or loss that may occur during transmission. This is especially important in environments with high levels of noise or interference, such as space communications.

TA implements communication protocols that define how data is formatted, transmitted, and received. Protocols ensure that data exchange adheres to standards and can be interpreted correctly by both the CPS and ground-based systems.

TA incorporates encryption and authentication mechanisms to protect data from unauthorized access or tampering. Secure communication protocols help safeguard the integrity and confidentiality of the transmitted data.

TA ensures that data is transmitted over the correct channels and that channel usage is optimized for the specific needs of the CPS and its test environment.

TA handles feedback and acknowledgment messages to confirm the successful receipt of data or commands. This feature helps ensure that communications are effectively established and maintained, providing a mechanism for error reporting and resolution.

In summary, telecommunication algorithms are essential for managing the communication between CPS and their test environments. They facilitate the configuration and test data exchange, transmit telemetry information, and ensure data integrity and security. By incorporating SITL, these algorithms can achieve greater accuracy and reliability in handling physical quantities, further enhancing communication effectiveness in complex CPS applications.

3.2.3. CPS Controlling Algorithms

CPS Controlling Algorithms (CPSCA) are essential for effectively managing and operating CPS. They orchestrate the functioning of CPS based on predefined tasks and configurations, and they predict the system's state using a comprehensive software model. This involves several key aspects:

CPSCA is responsible for managing tasks defined in the system’s configuration. This includes scheduling, prioritizing, and executing CPS functions according to the system’s operational requirements. For instance, in an autonomous vehicle, these tasks might involve navigation, obstacle avoidance, and real-time decision-making based on sensor inputs.

Using a software model of the CPS, CPSCA predicts the system's future state. This model is built based on physical laws, system dynamics, and historical data. Simulating different scenarios and input conditions helps the software model anticipate how the system will behave, allowing for proactive adjustments and optimizations.

CPSCA continuously monitors the CPS’s performance and makes real-time adjustments based on the predictions from the software model. This dynamic control is crucial for maintaining optimal performance, efficiency, and safety. In industrial automation, for instance, controlling algorithms might adjust machinery operations to compensate for wear and tear or to adapt to changing production requirements.

CPSCA integrates with sensor data to update the software model and refine predictions. Sensors provide real-time feedback on the system’s state, which is used to validate and adjust the projections. For example, in aerospace applications, sensors might provide data on altitude, speed, and orientation, which is then used to update flight control algorithms and ensure accurate navigation.

CPSCA are designed to handle uncertainties and variabilities in the system’s environment and operation. This includes accounting for unexpected changes or disturbances, such as hardware failures or environmental factors. Advanced algorithms incorporate probabilistic models and adaptive control techniques to manage such uncertainties effectively.

CPSCA aims to optimize the CPS performance by minimizing resource usage, improving response times, and enhancing overall efficiency. This might involve optimizing energy consumption in smart buildings or maximizing throughput in manufacturing processes.

Ensuring the safety and reliability of the CPS is a critical aspect of controlling algorithms. These algorithms incorporate safety checks, fault detection, and recovery mechanisms to prevent or mitigate failures.

CPSCA uses adaptive control strategies to adjust their behavior based on changing conditions or new information. This allows the CPS to remain robust and flexible in the face of evolving requirements or environmental changes.

By employing SITL within CPSCA, developers can ensure that all physical quantities involved in the control processes adhere to rigorous dimensional and orientation standards. This integration helps maintain consistency and correctness across various system components, leading to more reliable and accurate control actions. SITL’s ability to enforce dimensional correctness and support formal verification further enhances the robustness of control algorithms, making them more effective in managing complex CPS operations.

In summary, CPSCA is vital for managing and optimizing the CPS performance. They rely on sophisticated software models, real-time data integration, and adaptive control strategies to ensure the system operates efficiently, safely, and accurately. Using SITL in these algorithms ensures that dimensional and orientation consistency is maintained, contributing to the overall reliability and effectiveness of the CPS.

3.2.4. Telemetry Algorithms

Telemetry Algorithms employ orthogonal polynomials to efficiently process different subsets of telemetry data, enabling high data compression [[35[M1] ]. The algorithms can significantly reduce the data size while preserving critical information by selecting the appropriate polynomials for specific data types, such as sensor readings or environmental conditions.

Incorporating the SITL into these algorithms ensures that the dimensional and orientational consistency of the telemetry data is rigorously maintained throughout the compression process. Using SITL helps verify the correctness of units and their relationships during data handling, which is critical in applications where even minor inconsistencies could lead to mission failure.

This effective compression minimizes the bandwidth required for transmitting large volumes of telemetry data and reduces the energy consumption needed for communication between spacecraft and Earth [

34]. As a result, combining orthogonal polynomials and SITL ensures data integrity, unit consistency, and energy efficiency, contributing to extended mission lifespans and improved performance in resource-constrained environments like spacecraft, satellites, and deep-space probes.

3.2.5. Actuator Control Algorithms

Actuator Control Algorithms play a critical role in the control and performance verification of CPS actuators, such as onboard engines for orientation and orbit correction, electric motors, gyroscopes for object orientation, pumps, and fans. Precise control over these actuators is essential for the stable and reliable functioning of systems like spacecraft, satellites, and autonomous vehicles.

Incorporating the SITL into actuator control algorithms enhances their accuracy and reliability by ensuring that all physical quantities—such as force, torque, velocity, and angular momentum—are managed with dimensional consistency and orientation correctness. SITL verifies that all interactions between actuators and the control algorithms adhere to the strict rules of SI units, preventing issues such as mismatched units, incorrect scaling, or directional errors, which could otherwise result in system failure.

For example, in the case of onboard engines used for orientation and orbit correction, SITL helps ensure that the thrust calculations are dimensionally accurate while verifying the direction of force application. Similarly, for gyroscopes controlling object orientation, SITL confirms that angular momentum and rotational forces are correctly modeled in magnitude and orientation, reducing the risk of misalignment or incorrect rotational control.

By using Siano orientation integrated with SITL, the algorithms can also account for the directional properties of these actuators, providing a more nuanced and reliable control mechanism for CPS. This extension is particularly valuable when dealing with actuators that operate in three-dimensional space, as it ensures that both scalar and directional components of physical quantities are accurately modeled and controlled.

Additionally, SITL supports compile-time verification of these algorithms, which ensures that any potential errors, such as unit mismatches or incorrect dimensional operations, are detected and resolved early in the development process. This leads to more robust and efficient control algorithms with lower runtime overhead and higher reliability.

In conclusion, by integrating SITL into actuator control algorithms, developers can ensure precise and error-free control of CPS actuators across various applications. Whether controlling spacecraft engines, motors, or gyroscopes, SITL enhances these systems' accuracy and efficiency, contributing to safer and more reliable operations in mission-critical environments.

3.2.6. Sensor Control Algorithms

Sensor Control Algorithms (SCA) are critical for managing and verifying the performance of various CPS sensors, such as gyroscopes, accelerometers, cameras, radar systems, magnetic field sensors, and cosmic ray detectors. The accuracy and reliability of these sensors are essential for collecting precise data that informs control decisions, navigation, and operational adjustments in real time, especially in mission-critical systems like spacecraft, autonomous vehicles, and industrial automation.

Incorporating the SITL into SCA enhances the reliability of sensor data processing by ensuring that all measured quantities—such as acceleration, angular velocity, magnetic field strength, and cosmic radiation intensity—are handled with strict adherence to SI units and dimensional consistency. SITL verifies that each sensor output is dimensionally correct, preventing unit mismatches that could lead to errors in subsequent computations, control decisions, or system responses.

For instance, in the case of gyroscopes and accelerometers, SITL ensures that rotational and linear measurements are dimensionally consistent with the system’s requirements for navigation and orientation. This is crucial for maintaining stability and accurate positioning in CPS, such as satellites or drones. In radar systems, SITL guarantees that distance, velocity, and time measurements are correctly aligned with SI units, reducing the risk of errors during target detection or speed measurement.

Furthermore, Siano's extension of the SI system, integrated into SITL, allows SCA to account for the directional properties of measured quantities. This is particularly valuable for sensors like magnetic fields and cosmic ray detectors, where both the magnitude and direction of the field or radiation must be considered. By leveraging Siano’s orientation, SITL provides a more nuanced representation of the sensor outputs, improving the accuracy of directional measurements and enhancing system performance in complex environments.

SITL also enables compile-time verification of SCA, detecting potential errors—such as unit inconsistencies or incorrect dimensional operations—early in development. This leads to safer, more efficient, and error-free software implementations. With SITL, developers can ensure that sensor data is not only accurate in terms of physical quantities but also aligned with the specific needs of the system’s control mechanisms.

In conclusion, by integrating SITL into SCA, developers can enhance sensor data's accuracy, dimensional consistency, and reliability across a wide range of CPS applications. Whether managing the precise measurements from gyroscopes, radars, or magnetic field sensors, SITL ensures that the data is handled correctly, providing a robust foundation for real-time decision-making and system optimization. This ultimately leads to more reliable and efficient sensor management, which is critical for mission success in aerospace, autonomous systems, and scientific exploration.

All embedded algorithms are implemented in C++20 using the SITL. This modern approach leverages C++20’s advanced features and the robustness of SITL to ensure that the algorithms are efficient but also reliable and maintainable.

3.2.7. SITL Benefits

Using SITL provides several benefits for the formal verification of embedded software:

Dimensional and Orientational Consistency: SITL ensures that all physical quantities in the embedded algorithms adhere to correct SI units and orientations. This is crucial for embedded systems where precise measurements and calculations are required, such as in aerospace, robotics, and automotive applications.

Formal Verification: SITL enables rigorous formal verification of embedded software by checking dimensional correctness and consistency at compile time. This helps to detect errors early in the development process, ensuring that the software behaves correctly with the given hardware configurations and that the unit operations conform to the defined physical laws.

Hardware Configuration Changes: Embedded systems often change hardware configurations due to upgrades or repairs. SITL helps maintain software correctness despite these changes by validating that the software remains compliant with SI units and dimensions even when the hardware components are altered or replaced. This ensures that the algorithms continue to perform as expected without introducing errors due to hardware modifications.

Software Configuration Changes: Besides hardware changes, software configurations may also be updated or modified. SITL provides a framework for ensuring that these configuration changes do not compromise the correctness of the algorithms. By continuously verifying dimensional and orientational accuracy, SITL helps maintain the integrity of the software across different configurations.

Enhanced Code Maintainability: Implementing algorithms with SITL in C++20 facilitates formal verification and improves code maintainability. Using modern C++20 features, such as concepts, literals, and ranges, combined with SITL’s type-safe unit management, results in more accessible code to understand, extend, and modify while ensuring that any changes adhere to strict correctness standards.

Efficiency and Performance: C++20’s features and SITL’s compile-time checks contribute to the efficiency and performance of the embedded algorithms. By catching errors early and ensuring dimensional correctness, SITL helps reduce runtime overhead and computational inefficiencies, leading to more optimized and faster-executing embedded software.

Robust Error Detection: SITL's compile-time checks provide robust error detection capabilities, helping to identify issues related to unit mismatches, incorrect calculations, or logical errors before the software is deployed. This proactive approach to error management enhances the overall reliability and stability of the embedded systems.

Implementing embedded algorithms in C++20 using SITL offers significant advantages in formal verification, code maintainability, and performance. SITL ensures that the software remains correct and reliable, even when hardware or software configurations change, making it a powerful tool for developing high-integrity embedded systems.