In the following, we evaluate and discuss the results of the conducted cycle aging studies. First, the formation of cell inhomogeneities during cycling is outlined, followed by the impact of the test procedure and cycling interruptions due to CU and rest phases. Based on these findings, the influence of DOD and current rate on in- and rehomogenization behavior is presented. Finally, methods to actively support intermediate cell rehomogenization are analyzed.

3.1. Formation of Cell Inhomogeneities During Cycling

Several studies have reported inhomogeneous cell conditions in terms of negative electrode lithiation [

9,

12,

15] and conducting salt distribution [

37]. These inhomogeneities result from cell cycling, which triggers the formation of concentration gradients. Electrolyte motion due to volume changes of the jelly roll further enhances these gradients [

19]. As a result, the kinetic overpotentials increase, leading to the earlier reaching of the cut-off voltage and consequently reducing the extractable capacity [

21]. These effects are reversible as long as a critical cell condition has not been exceeded. However, they lead to an increasingly uneven distribution of the locally acting stresses, promoting localized degradation spots, e.g., due to lithium plating.

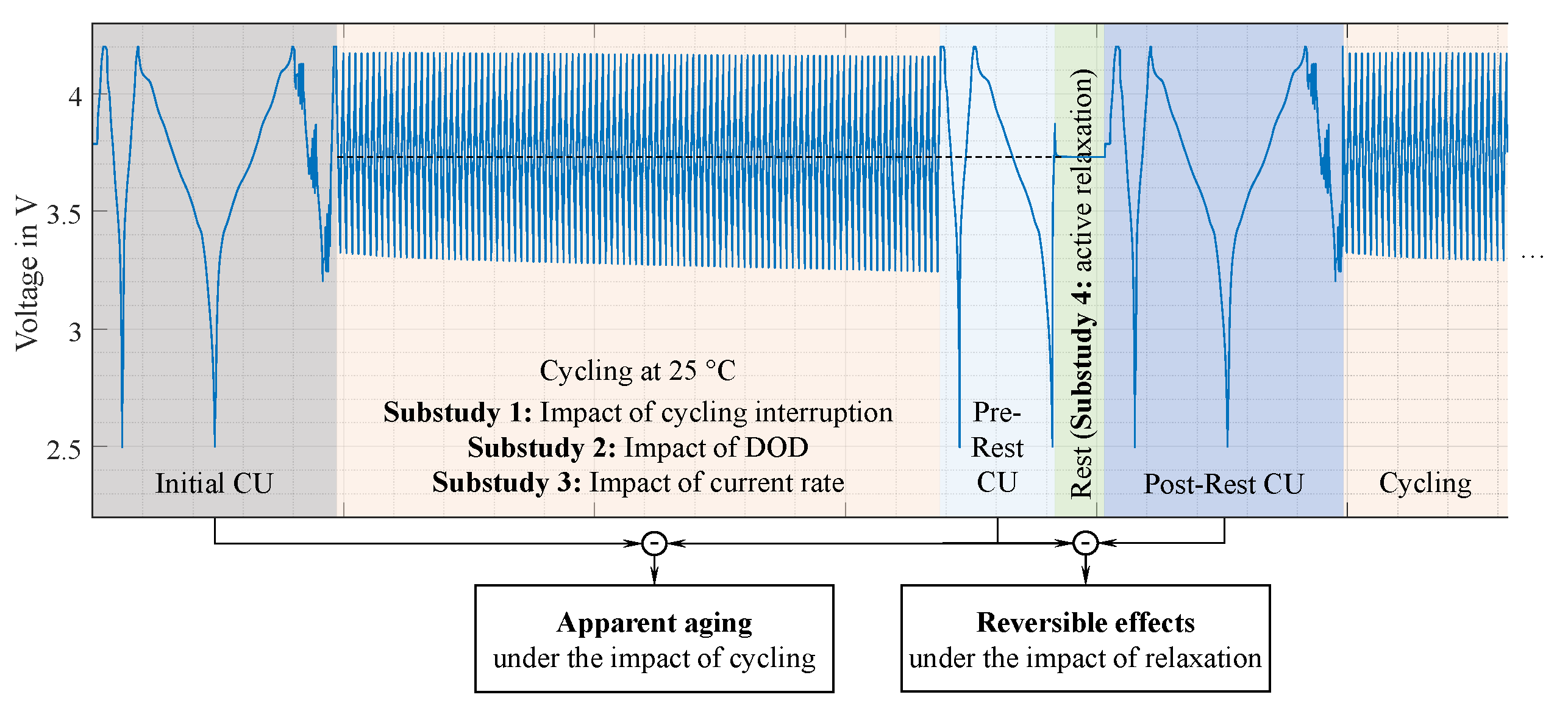

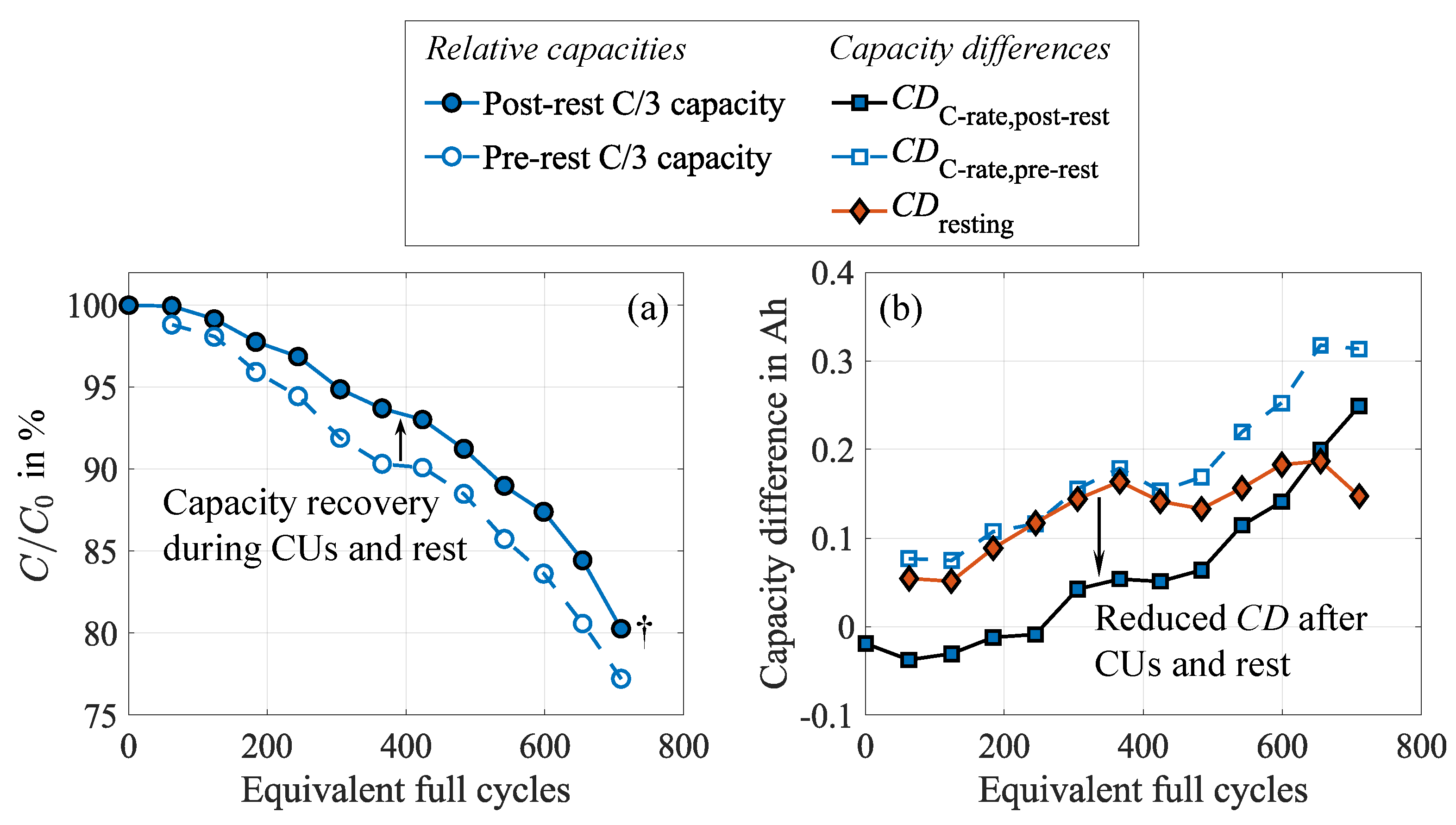

To show these effects and the underlying cell behavior, the 20 to 100 SOC test case is considered exemplary because it shows the most pronounced effects and allows for the analysis of

, in contrast to the full DOD test case. For the latter, discharging is always terminated at

, and therefore, no

alterations occur. The reversibility mentioned above becomes evident in

Figure 4 (a), illustrating the relative capacity during the cycle aging study. The dashed line represents the capacity measured in the pre-rest CU directly after cycling, while the solid line depicts the capacity extracted from the post-rest CU after the subsequent ten-hour rest. Both measurements follow the same procedure, though they reveal a clear discrepancy in the extractable capacity, as shown by the red curve in

Figure 4 (b). In addition, the capacity differences

between low (C/15) and high current (C/3) discharge, obtained from the pre-rest (blue curve) and the post-rest CU (black curve), are depicted, also revealing a discrepancy, as presented in our earlier publication [

34].

Since measurement impacts can be precluded, these differences must result from effects occurring during the rest phase and the CU. After cycling, the cell exhibits the inhomogeneities in terms of lithiation and conducting salt distribution mentioned above to a certain degree. As a consequence, shares of the active lithium are inaccessible. During the rest phase and the CU, which are characterized by predominantly low-current charge and discharge sequences as well as several additional rest phases, these inhomogeneities can partly equalize, leading to a redistribution of lithium within the negative electrode and increasing the lithium accessibility. Therefore, the capacity increases. An inverse correlation with the

(

) is evident, revealing a reduced capacity difference after relaxation. Moreover, both capacity differences,

and

exhibit a high similarity, supporting the explanation of Lewerenz et al. [

21]. They emphasize that the capacity difference mainly results from inhomogeneous lithium distribution, which strongly limits the extractable capacity. Due to the different time scales during discharging at low and high current rates, these inhomogeneities equalize to varying degrees, explaining the capacity difference. While increased overpotentials due to a grown internal resistance also reduce the extractable capacity as the cut-off voltage is reached earlier depending on the C-rate, this impact is minor since the voltage curves are very steep at the end of discharge. Impacts of the negative electrode’s overhang during the rest phase are assumed negligible since the rest SOC matches the average SOC during cycling. Hence, no considerable lithiation differences should occur between the active and passive areas of the negative electrode.

It becomes evident that the capacity differences grow with progressing cycling. This suggests that as the cell is stressed, it becomes increasingly inhomogeneous, leading to growing capacity recovery during CU and rest. Starting at around 500 EFC, the previously observed high similarity ceases, and the capacity differences begin to diverge. One EFC represents a complete charge and discharge cycle, normalized to the nominal cell capacity. While

further increases,

reaches a maximum and subsequently drops significantly. This could either indicate the establishment of a dynamic equilibrium between inhomogenization and rehomogenization or the progressively increasing incompleteness of the rehomogenization process. Moreover, this further implies changes in degradation behavior and the dominant mechanism, which will be further discussed in

Section 3.5.

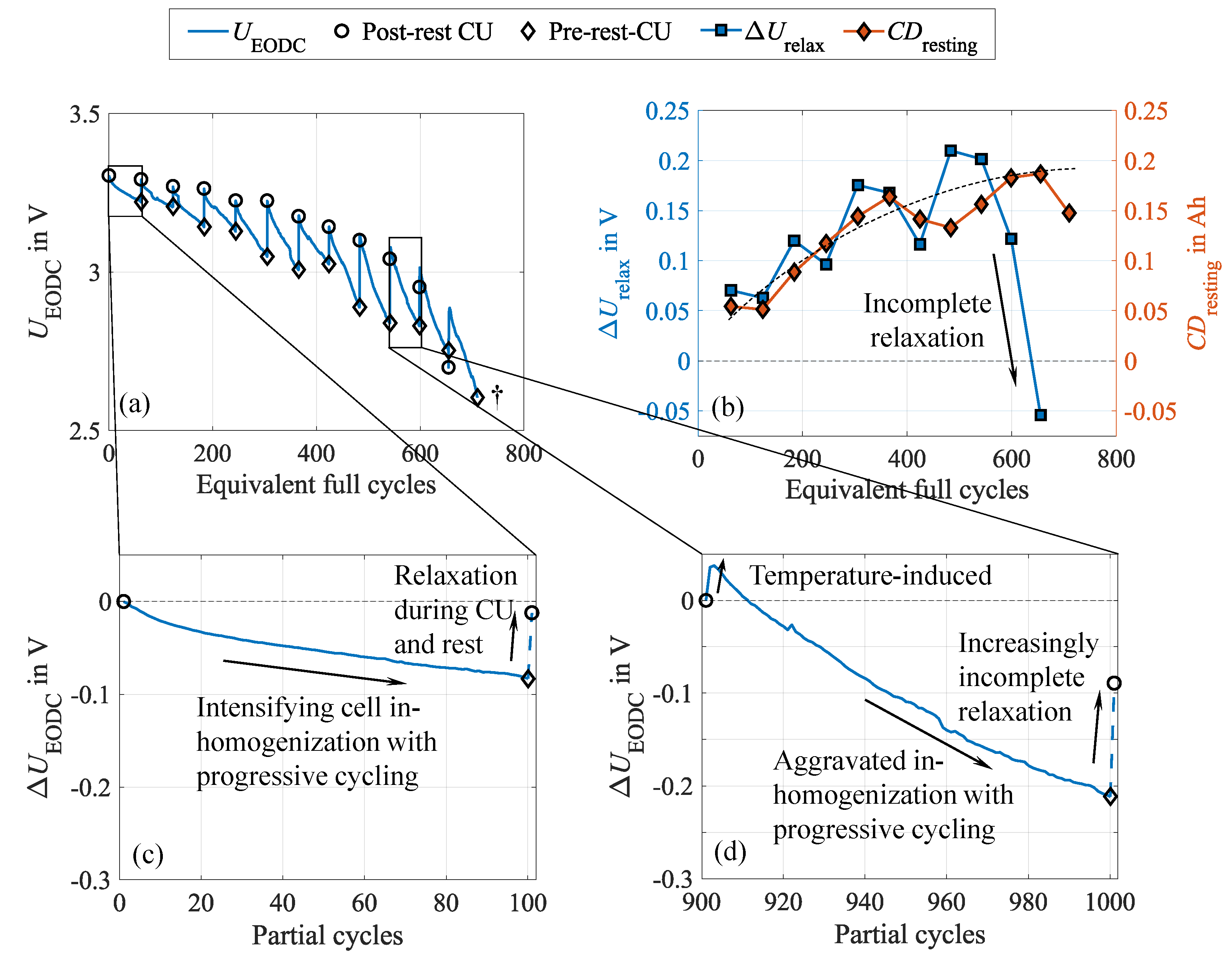

The

further supports this interpretation by its characteristic sawtooth pattern, as can be seen in

Figure 5 (a). Herein, one continuous cycle interval corresponds to one sawtooth, presented for an early aging state during the first 100 cycles in

Figure 5 (c) and for an advanced aging state in the cycle interval between 901 and 1000 in

Figure 5 (d). These observations give further insights into the ongoing phenomena, revealing two interlinked effects: Firstly,

descends towards lower values within one cycle interval as cycling progresses. This results from increasing inhomogeneities in conducting salt distribution and lithiation degree within the negative electrode, leading to local SOC variations in the active material. Consequently, areas with decreased SOC are discharged to a lower voltage when extracting the same amount of charge, shifting

to lower values. In addition, increasing cell polarization due to growing conducting salt gradients causes the overpotentials to increase, specifically the concentration overpotential. During cycling, concentration gradients form within the cell, which aggravate with progressive, continuous cycling. Electrolyte motion due to volume changes leads to a local conducting salt enrichment in the center of the jelly roll, while salt depletes at the edges [

19,

37]. It needs to be considered that such characteristic behavior can also result from a drift of the SOC window caused by small deviations between the discharged and recharged amount of charge. In our tests, however, this can be excluded because both charging and discharging were terminated charge-based, and therefore, this impact is negligible.

Secondly, the spike after the 100

th cycle reveals cell relaxation during resting and CU. During the rest, the lithium distribution in the negative electrode rehomogenizes, and concentration gradients of the conducting salt equalize, leading to a more uniform lithiation. This manifests itself in the observable reset of the

and is illustrated in

Figure 5 (b).

Comparing the cell behavior in the two highlighted cycle intervals provides insights into the long-term behavior. The intensity of both the inhomogenization during cycling and the rehomogenization during resting amplifies with progressing cycling. This is evident from the increasingly steep decline of

during cycling and the subsequently more pronounced voltage spike. However, the inhomogenization effects grow disproportionally compared to the rehomogenization. Despite intensified relaxation effects over the course of the experiment,

Figure 5 (d) reveals a significantly more incomplete and prolonged cell relaxation compared to the early aging state. This effect, indicated by the peak during the first cycles, is temperature-induced, as the cell cools down during CU and rest and heats up during the first cycles. The rising temperature supports equalization processes and reduces overpotentials, ultimately leading to an increased

. This increasingly incomplete relaxation aligns with our previous findings regarding the growing capacity difference and the declining capacity recovery rate. In addition,

Figure 5 (b) illustrates the progressions of

, representing the regained capacity during relaxation, and the voltage relaxations

during CU and rest, proofing a strong correlation of both. The values of the voltage relaxation represent the difference of

between every 100

th cycle (indicated by the diamond marker) and every first cycle of the subsequent cycle sequence (indicated by the circle marker). Consequently,

serves as a measure for the voltage relaxation, such as

represents the charge regain. This behavior seems plausible, as the redistribution of lithium during the rest leads to a more homogeneous SOC distribution throughout the negative electrode, and the polarization declines due to the equalization of concentration gradients. Therefore, the voltage window tightens.

It has to be noted that the reversible capacity losses are inherently superimposed by irreversible ones due to unavoidable degradation mechanisms, including, e.g., SEI growth consuming active lithium or loss of active electrode material, e.g., due to particle cracking as a result of volume changes [

10]. This irreversible capacity loss also causes a widening of the traversed voltage window. However, a sole irreversible degradation would not exhibit the observed voltage reset during the rest.

3.2. Impact of the Test Procedure on Cell Inhomogeneities

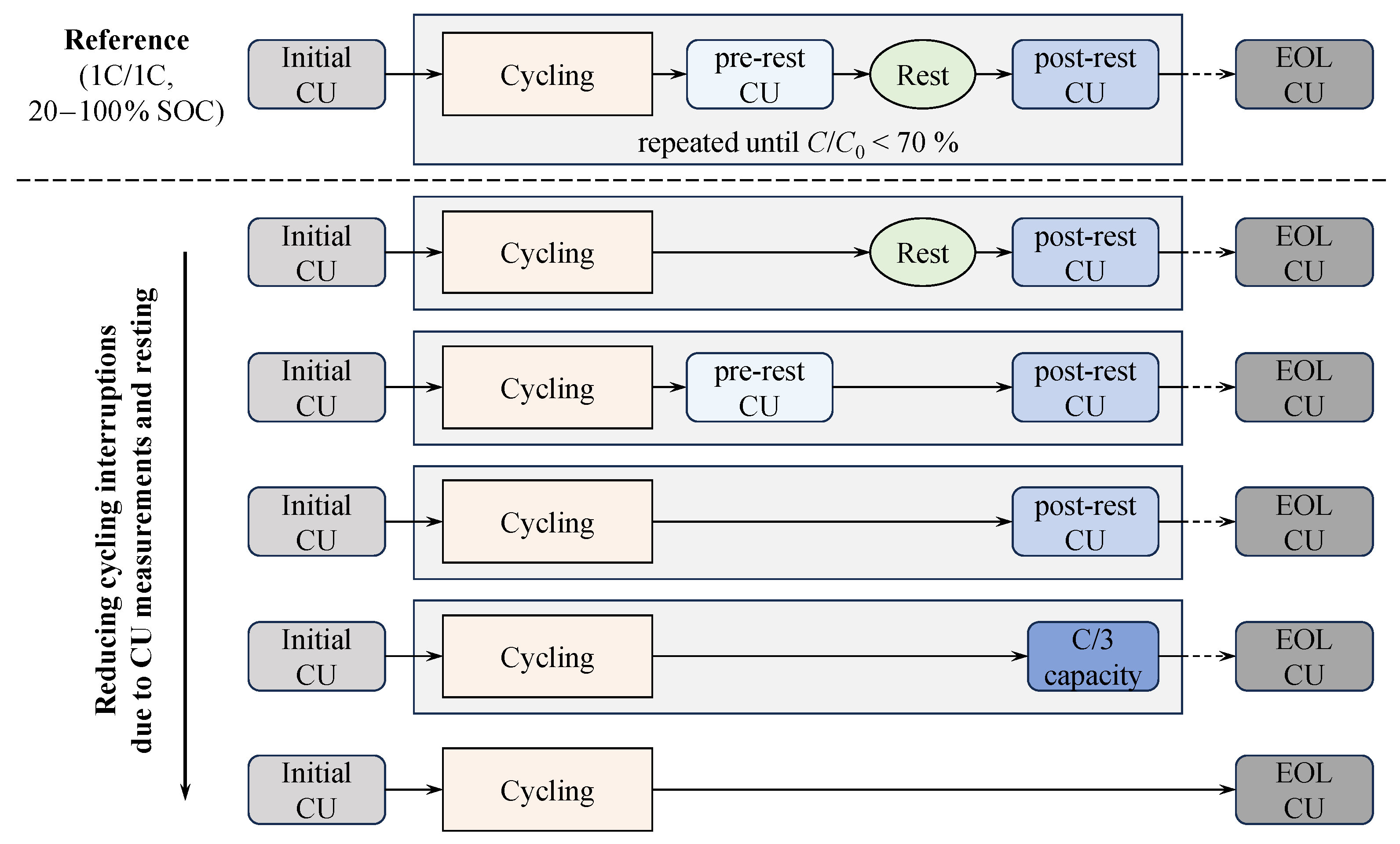

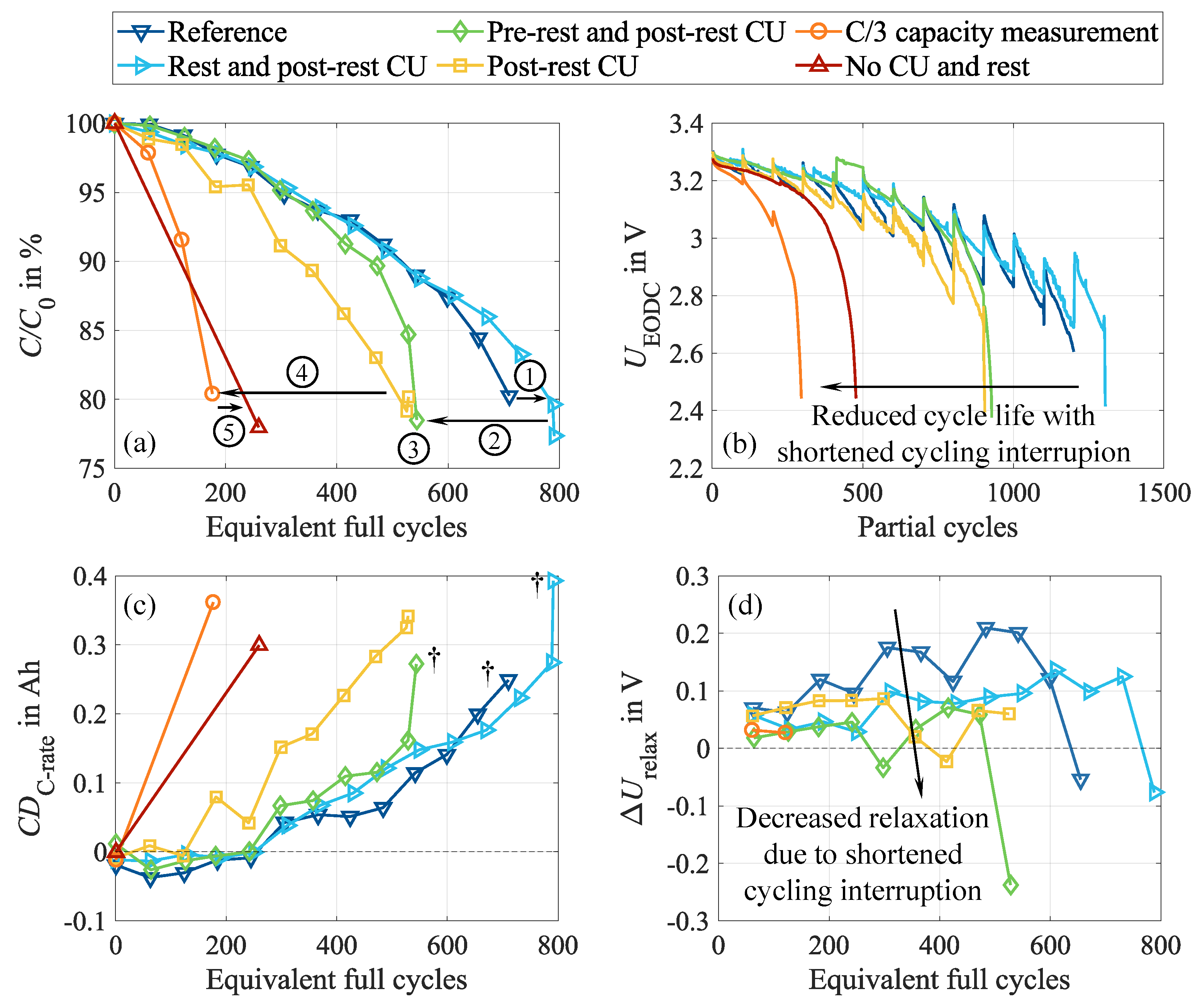

The observed behavior during cycling and the subsequent CUs and rest phase emphasizes considerable reversible effects triggered by continuous cycling. To further investigate how these effects are influenced by the test design and how they manipulate long-term cell behavior, we now focus on the impact of cycling interruptions through CU procedures and rest phases. For this purpose, we stepwise reduced the cycling interruption and sequentially removed specific CU elements and the rest phase. The associated degradation behavior is visualized in

Figure 6. While the reference case (dark blue curve) as one edge case contains the entire pre-rest CU, the ten-hour rest, and the complete post-rest CU every 100 cycles, in the opposite edge case (dark red curve), the cell is continuously cycled and CU are performed only at BOL and EOL. The cycling procedure and the associated stress factors, however, are identical in all cases.

The relative capacities of the cells show a clear trend: shorter cycling interruptions trigger significantly higher degradation rates, as shown in

Figure 6 (a). The best-performing cell completes four times as many cycles as the worst-performing cell before reaching 80 of the initial capacity. Unexpectedly, the BOL-EOL cell (dark red curve) exhibits a longer cycle life than the cell with intermediate capacity measurements every 100 cycles (orange curve). We assume that these capacity measurements, which were performed in the entire voltage range between

and

, cause additional cell inhomogenization and degradation in contrast to the sole cycling between 20 and 100 SOC. Particularly in the low SOC range, where silicon particles are primarily de-/lithiated [

31] and pronounced volume changes occur in the graphite, mechanical stresses are induced in the jelly roll. These stresses promote electrode degradation and electrolyte motion. Despite a noticeable cell relaxation during these capacity measurements, which are evident in the peaks of the

in

Figure 6 (b), the damaging impact is expected to dominate. However, it should also be noted that already the first cycle interval of this particular cell (orange curve) deviates from the others, as

declines significantly stronger during the first 100 cycles. This is suspicious since cell preparation, BOL CU, and cycling were identical in all test cases and, therefore, do not explain this behavior. We cannot preclude an outlier behavior of this specific cell.

In good agreement with the relative capacity, shows a faster decline for test cases with shorter cycling interruptions. The ten-hour rest seems to be especially beneficial for the degradation behavior, as highlighted by the comparison between the blue and green curves. Moreover, voltage relaxation in the test case with only capacity measurements is significantly lower compared to the test cases with extended CU and rest. This is caused by the considerably shorter relaxation time. Consequently, equalization processes can only take place to a minor extent. Unintended intermediate voltage relaxation is observable for the test case without pre-rest CU (light blue curve) at 336 cycles and the test case without rest (green curve) at 411 cycles, highlighted by asterisk markers. In both cases, a power outage led to a test interruption followed by an unintended resting period of several hours. The relaxation is particularly pronounced for the latter because restarting the test caused several further interruptions shortly after the restart. We assume that the combination of this resting phase and current pulses promoted cell relaxation, explaining this significant voltage setback.

The capacity difference

depicted in

Figure 6 (c) shows the inverse behavior of the capacity loss while revealing a high correlation. With decreasing cycling interruptions, the capacity differences increase faster, indicating a faster inhomogenization of the conducting salt and lithium distribution. This coincides with less pronounced voltage relaxation for shorter cycling interruption, as illustrated in

Figure 6 (d). Due to these shorter interruptions, less time is available during which inhomogeneities can equalize. In addition, three of the cells show a prominent drop in

directly before reaching EOL.

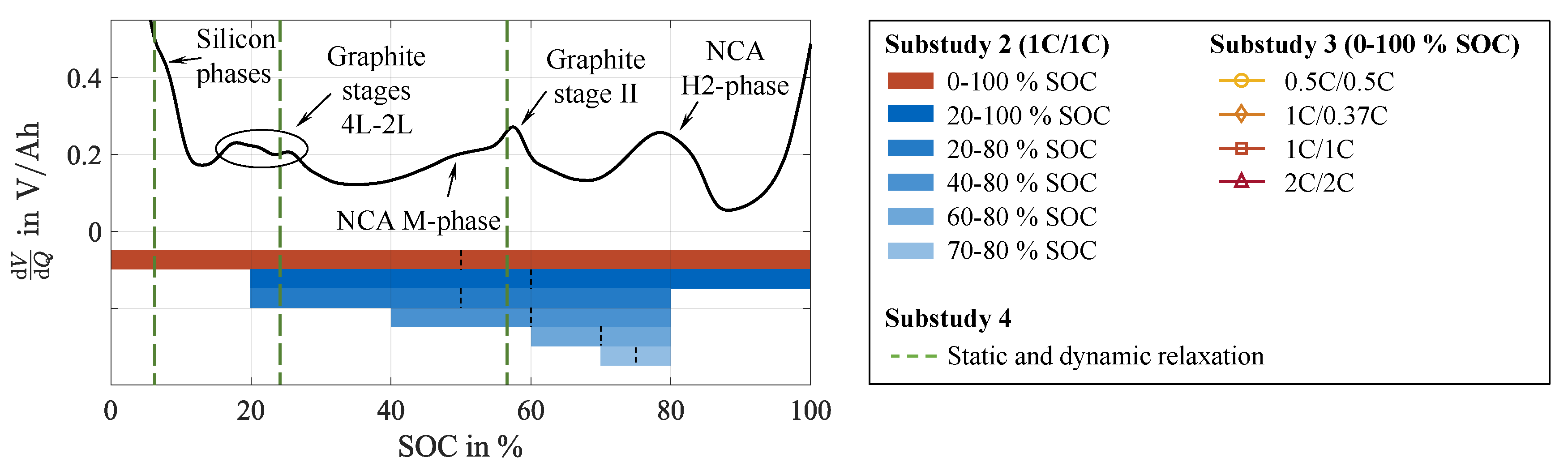

3.3. Impact of Stress Factors During Cycling

After demonstrating how the test procedure, especially the resting phase, impacts the cell behavior by partially reversing capacity fade during CU and rest phases, we now focus on the influences of different stress factors during cycling. For this purpose, we investigate the cell behavior during cycling and relaxation during rest phases. In contrast to the results presented above, the cells of the subsequent two substudies were all subjected to the identical pre- and post-rest CU procedure, as well as the intermediate ten-hour rest. Instead of 1C/1C cycling in the 20 to 100 SOC window, in the first substudy, the DOD and SOC range was varied, while the current rates remained fixed at 1C/1C. In the second substudy, the DOD was set to 100 , and the current rates were modulated.

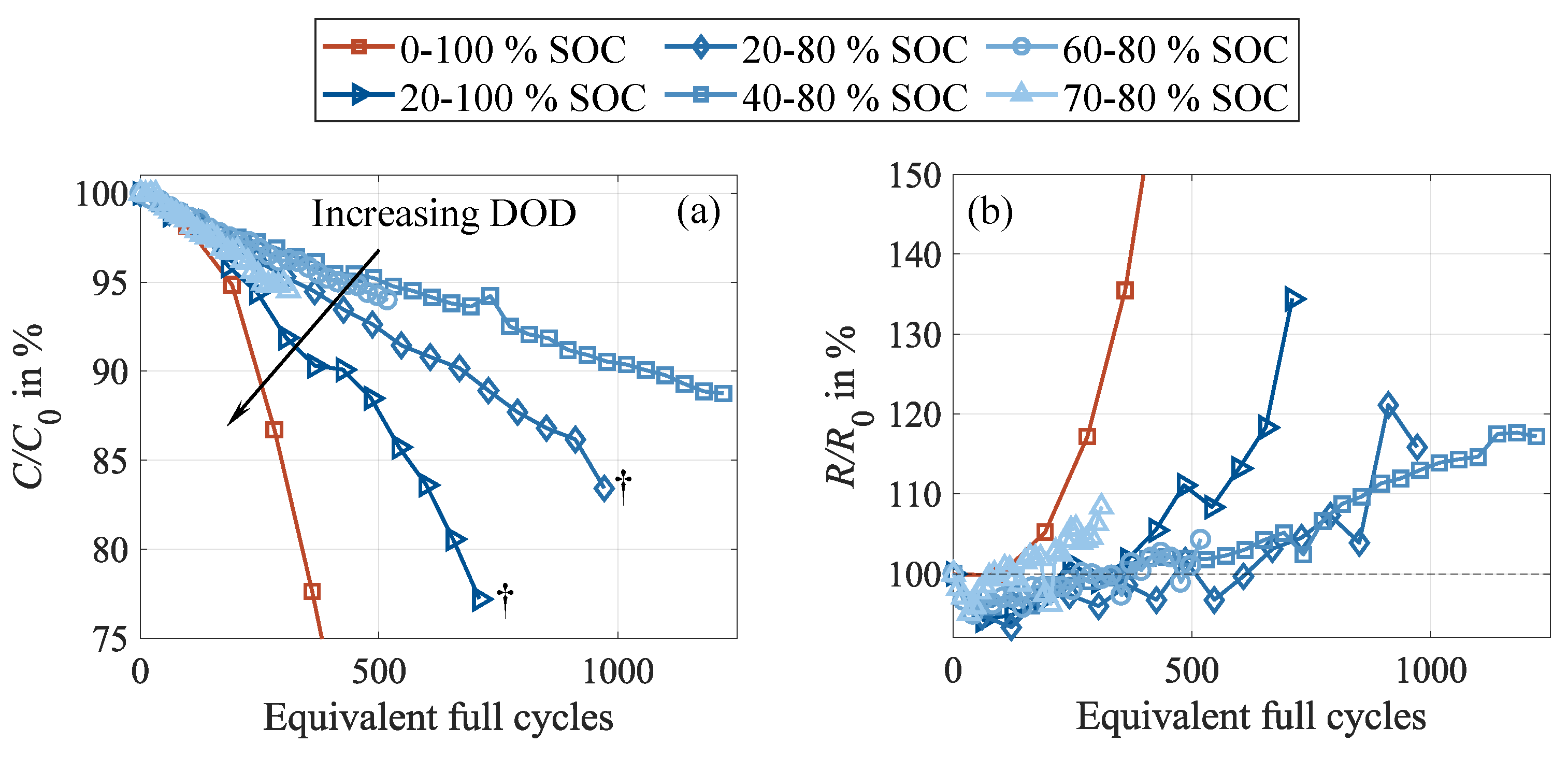

3.3.1. Depth of Discharge

At first glance, the cells exhibit a typical degradation behavior, revealing well-established dependencies on the DOD as a stress factor, as plotted in

Figure 7. These dependencies are reported as increasing degradation rates with higher DOD [

38,

39] and average cell SOC [

39,

40]. Stronger degradation at higher DOD is commonly attributed to intensified volumetric changes and, thus, increased mechanical stress, notably in the negative electrode [

41]. This is further aggravated for silicon-containing cells when cycling in low SOC areas due to even higher volumetric changes because of the de-/intercalation of the silicon particles [

38]. The influence of increasing average SOC on higher capacity fade is often linked to the enhanced dissolution of nickel-rich materials [

39,

40,

41,

42], caused by elevated cell voltage, with subsequent deposition of the oxidation products in cover layers on the negative electrode [

41,

42,

43,

44]. In this regard, it should be considered that the CU are carried out after an equal number of 100 partial cycles across all test cases. As a result, for decreasing DOD, the CU frequency increases with respect to testing time and charge throughput. This leads to a higher cell exposure due to the full cycles performed in the CU. For this reason, we expect a superimposing impact, falsifying the observable SOC dependency. Moreover, it has to be noted that these results represent the cell behavior directly after cycling, thus not incorporating any relaxation effects.

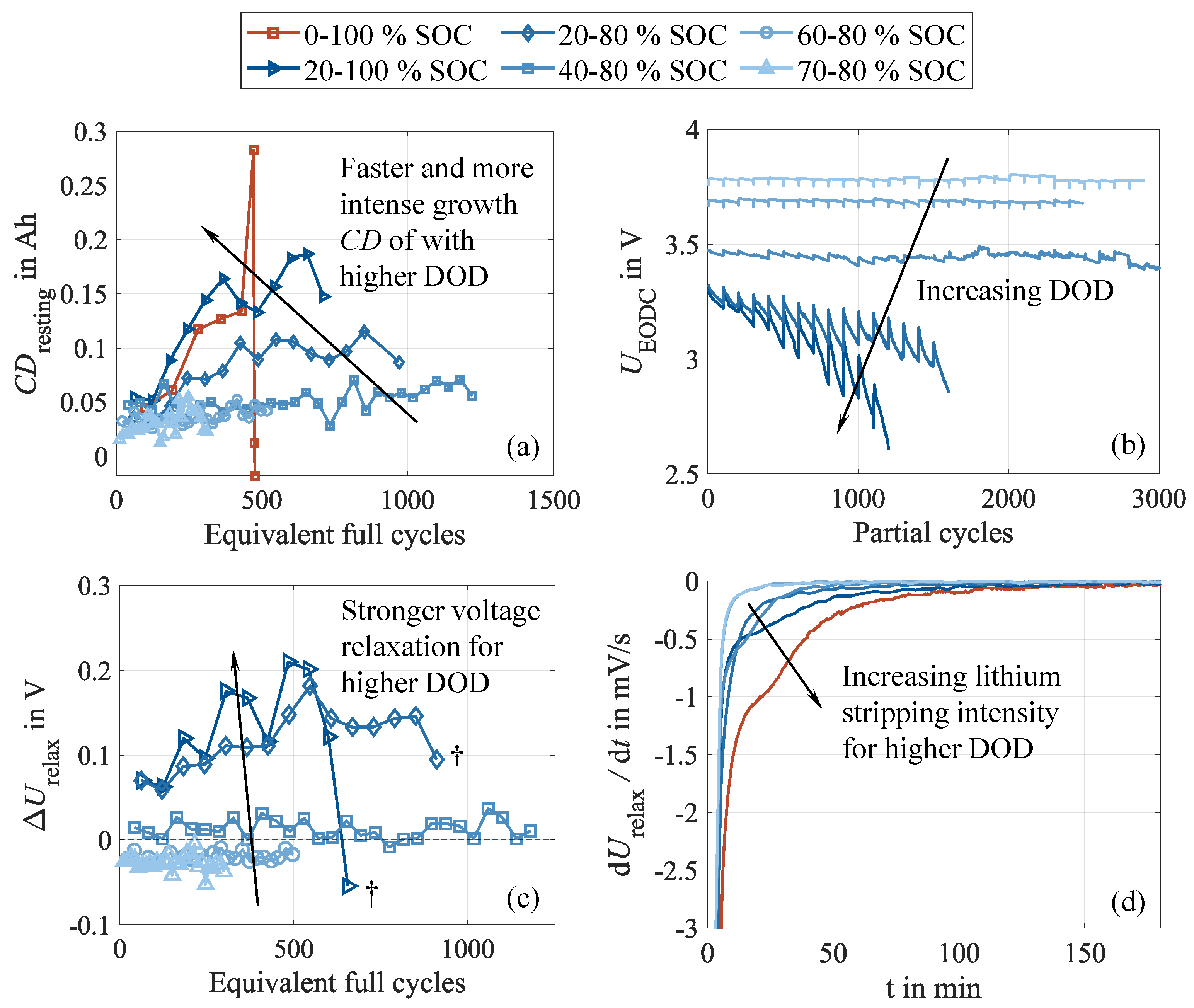

However, what is commonly not considered is the occurrence of reversible capacity loss [

34]. Hence, a different picture emerges when looking deeper into the cell behavior during cycling. The capacity difference under various DOD enables the assessment of the DOD’s impact on reversible capacity loss. Corresponding to

Figure 8 (a), the cells follow a logarithmic increase. A trend consistent with the one observed for shortened cycling interruptions is evident, with higher DOD causing more severe capacity differences and a faster growth rate in the early cycles. This suggests that inhomogenziation effects are more pronounced at higher cycle depths, which is in alignment with findings from the literature [

9,

15] and explained by the more pronounced EMSI effect due to stronger volume changes [

19]. As the electrolyte motion is intensified, this leads to more severe conducting salt gradients and aggravates cell inhomogenization. These enhanced gradients could explain the higher capacity differences and the higher observable capacity loss when cycling at higher cycle depths. Cells cycled at DOD of 40 and less show the identical increase in capacity difference. In contrast, 60 , 80 , and 100 DOD lead to a pronounced drop in the capacity difference shortly before transitioning into an accelerated capacity loss and the subsequent cell failure, commonly denoted as knee point. Consequently, the measurable capacity loss is superimposed by growing shares of reversible capacity losses. It is assumed that DOD around 40 located around the 50 average cycling SOC represent a threshold, and lower DODs do not reduce the impact on cell inhomogenization.

In good agreement with these results, the impact on

is enhanced by increasing DOD, revealing the same trend and consequently indicating stronger cell inhomogenization when applying larger cycle depths [

34]. This becomes evident in

Figure 8 (b) and (c), showing the progressions of the end of discharge voltages as well as the voltage relaxations during CU and rest. As observed earlier, the intensity of inhomogenization, as well as incomplete relaxation during rest, amplifies with progressive cycling, suggesting a self-reinforcing behavior [

14]. In this regard, it should be recapitulated that the number of cycle repetitions between two subsequent CU is the same for all test cases. Thus, cells with a larger DOD experience a higher charge throughput during cycling between two subsequent CU than cells with a lower DOD. This higher charge throughput causes even stronger inhomogenization during cycling, supporting the self-reinforcing behavior. In addition, a lower CU frequency related to the charge throughput allows for less frequent cell relaxation and, thus, rehomogenization, limiting the comparability of the observed magnitudes of inhomogenization between the different DOD test cases.

A specific behavior is observable in

Figure 8 (c) for cells with a DOD of 40 or less. For these cells,

ranges around or below 0

, indicating a decrease of

during CU and rest, while it increases during the first cycles of each cycling sequence. This is traced back to temperature influences. During CU and rest, the cells are allowed for thermal relaxation because of the low cyclic stresses and the extended rest phases, enabling the cells to approach the ambient climate chamber temperature. As cycling restarts, the cells heat up again due to internal resistive effects. This cell heating follows a logarithmic progression and takes several cycles to fully establish and approach its dynamic equilibrium point.

Moreover, all three cells that failed during the aging experiment, namely 60 DOD, 80 , and 100 , show a pronounced drop in capacity difference before the last CU. This coincides with a significant resistance rise, as well as plateaus in the stripping potential, depicted in

Figure 8 (d). Again, a clear dependency on the DOD can be seen, with higher capacity differences, higher internal resistance growth, more pronounced lithium stripping, and earlier occurrence of cell failure linked to higher DOD. These symptoms of accelerated capacity loss accompanied by increased resistance growth, as well as the occurrence of lithium stripping, are often associated with lithium plating [

28,

32,

41]. This interpretation aligns with the expected degradation behavior of severely inhomogenized battery cells [

9,

14,

45] and seems plausible, considering the underlying mechanisms. Due to the metallic deposition of lithium on the surface of the negative electrode caused by the plating reaction, active lithium is consumed, which explains the capacity loss. Moreover, due to the cover layers formed of plated lithium, the active surface of the negative electrode decreases, resulting in a significant resistance increase [

41]. Finally, the initially localized plating spots rapidly spread across the entire negative electrode surface, explaining the degradation dynamics manifesting in the capacity knee point and the sudden exponential resistance increase.

Consequently, once a critical point is surpassed, the reversible behavior becomes irreversible, causing rapid cell degradation, ultimately leading to cell failure. Therefore, according to our results, sufficiently long and repeated rest periods should be provided, especially for large DODs.

3.3.2. Current Rate

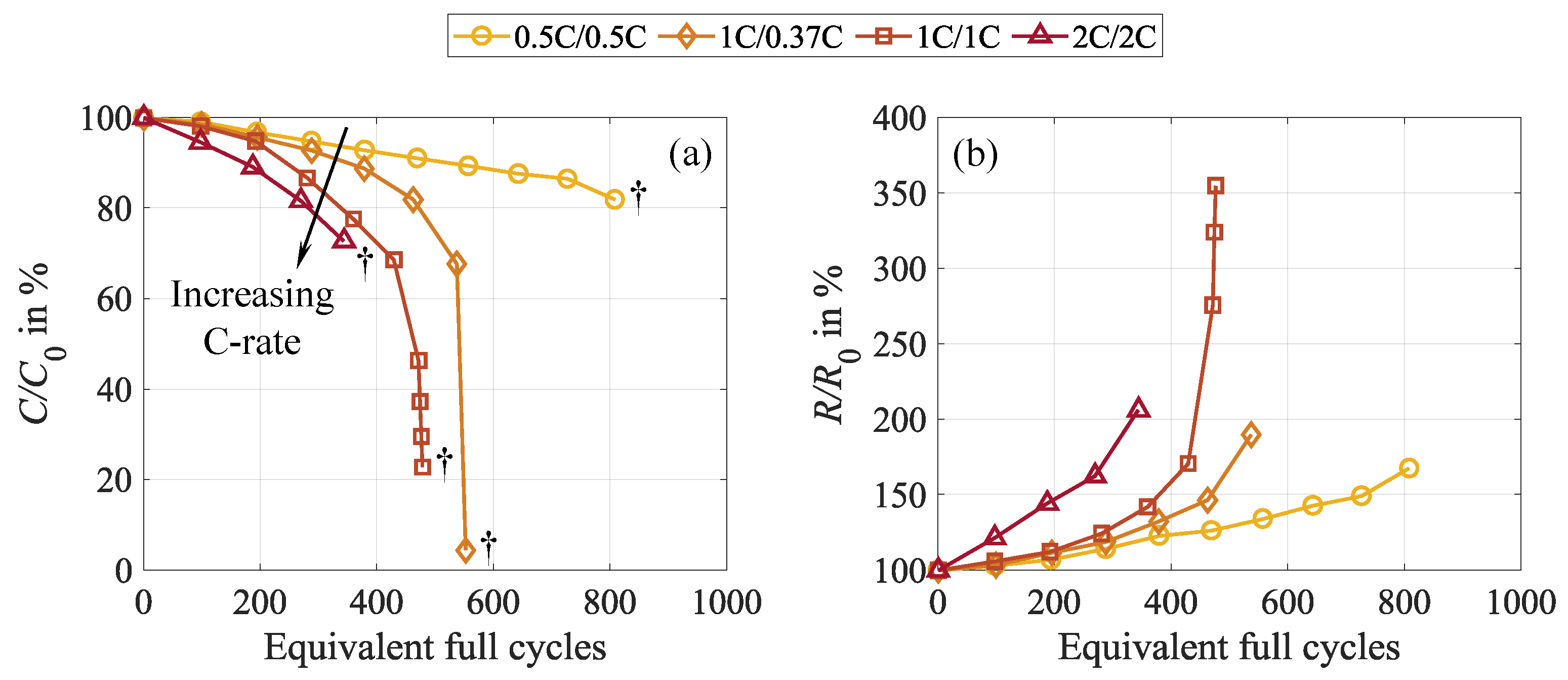

The same trend becomes evident for the current rate, with increasing currents causing more severe apparent capacity loss and resistance growth, as depicted in

Figure 9. Such measurement data represents common observations presented in the literature and is often explained by increased negative electrode degradation as a consequence of high currents or electrode surface passivation and lithium loss due to lithium plating [

41,

46].

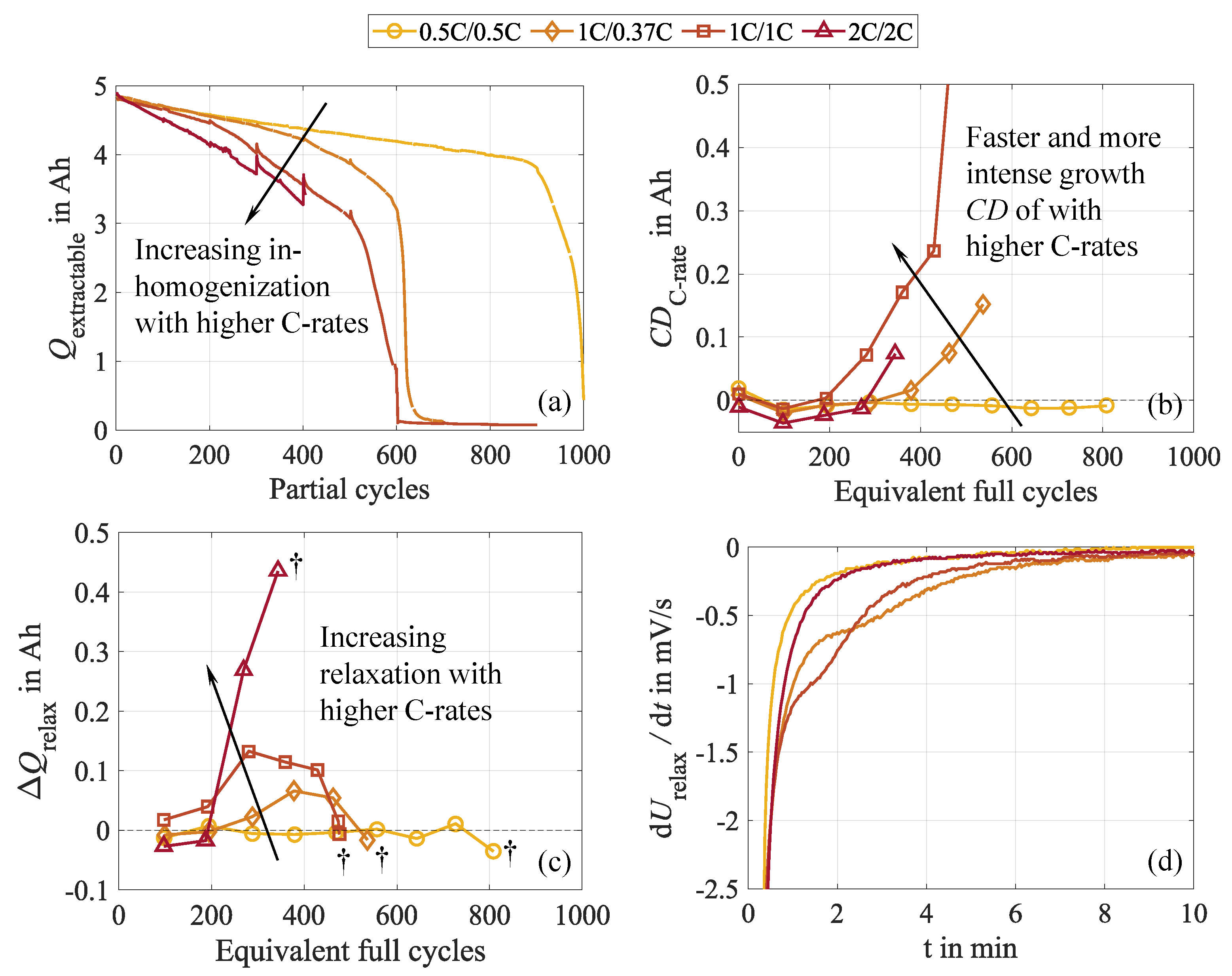

However, increasing the current rates not only aggravates the observable capacity loss but also intensifies cell inhomogenization. This coincides with increasingly declining charge throughput during cycling and more pronounced resets during CU and rest. Like for the DOD, the capacity differences prove an intensifying and faster-growing lateral lithium-ion flow with increasing current rates and progressive cycling, which is shown in

Figure 10 (a) and (b). Overall, these findings agree with the results presented in the literature [

9,

19].

As evident from

Figure 10 (b), cycling at C/2, which is the lowest C-rate investigated in this study, exhibits an almost constant capacity difference until approximately 900 cycles. Afterwards, the knee point is reached and the cell fails shortly thereafter. At the same time, an approximately linear progression of the extractable charge during cycling occurs with no peaks around the CU and rest phases, as shown in

Figure 10 (a). Since the cells are cycled in the entire SOC range in this substudy, the discharging is terminated uniformly at

. Consequently, no alterations in

can be used to indicate cell inhomogeneity. However, as the DOD remains identical, changes in the extractable charge in every single cycle give insight into cell homogeneity. This suggests that no considerable rehomogenization and therefore no capacity recovery occurs in this test case, which is visualized in

Figure 10 (c). As an equivalent indicator to

,

is analyzed in this case. It represents the amount of regained capacity during CU and rest and is calculated as the difference between the discharge capacity of the first cycle in a cycle interval directly after a CU and the last cycle of the preceding cycle interval before a CU. This parameter is not equivalent to the capacity difference between pre-rest and post-rest CU mentioned earlier. Unlike the capacity difference,

is derived from cycling data rather than CU measurements. Nevertheless, it reflects the same cell behavior.

In contrast, for the 2C/2C test case, marking the other edge case in this substudy, significant capacity recovery during CUs and rest is found. However, this effect sets in at 300 cycles, while until 200 cycles, no signs of recovery are observable. This coincides with the initial linear decline in discharge capacity during the first 200 cycles and the missing indicators for cell relaxation during rest and CU. Temperature effects can partly explain the behavior before this point. Due to the significantly higher C-rates during cycling than in the other test cases, the cell heats up considerably more. This is assumed to reduce cell inhomogenization during the initial phase of cycling. As this self-heating takes a few cycles and the cell cools down during CU and rest, the extractable capacity during the first cycles of every sequence is lower. Consequently, recovery and temperature effects are superimposed and conceal each other. In addition, the self-heating impacts the pre-rest CU, which is performed directly after cycling, while the cell cools down during the pre-rest CU and rest phase. As a result, the extractable capacities in the pre-rest CU are higher due to the supporting effect of the elevated temperature, which manipulates the capacity difference calculation with the post-rest CU.

The capacity regained during CU and rest, depicted in

Figure 10 (c), indicates the approaching EOL, as already observed in the first substudy. The 0.5C/0.5C, 1C/0.37C, and 1C/1C test cases demonstrate a prominent decline shortly before reaching EOL, implying that the earlier reversible behavior turns irreversible. This is expected to result from severe lithium plating triggered by the highly inhomogeneous cell condition, causing pronounced, rapid, irreversible lithium loss. The stripping behavior of these cells, provided in

Figure 10 (d), supports this theory, as distinct plateaus are evident for the 1C/0.37C and 1C/1C test cases shortly before reaching the knee point. Thus, it proves the earlier occurrence of lithium plating [

28]. Such plateaus are not observable for the 2C/2C test case. However, this does not prove the absence of lithium plating; it only shows the missing recovery of earlier plated lithium. Considering the test termination in cycle 406 (approx. 350 EFC) due to the activation of the CID in conjunction with the other analysis of this particular cell, we still expect lithium plating due to the high charging current and the severe inhomogeneity causing cell failure.

3.4. Supporting Cell Recovery During Cycling

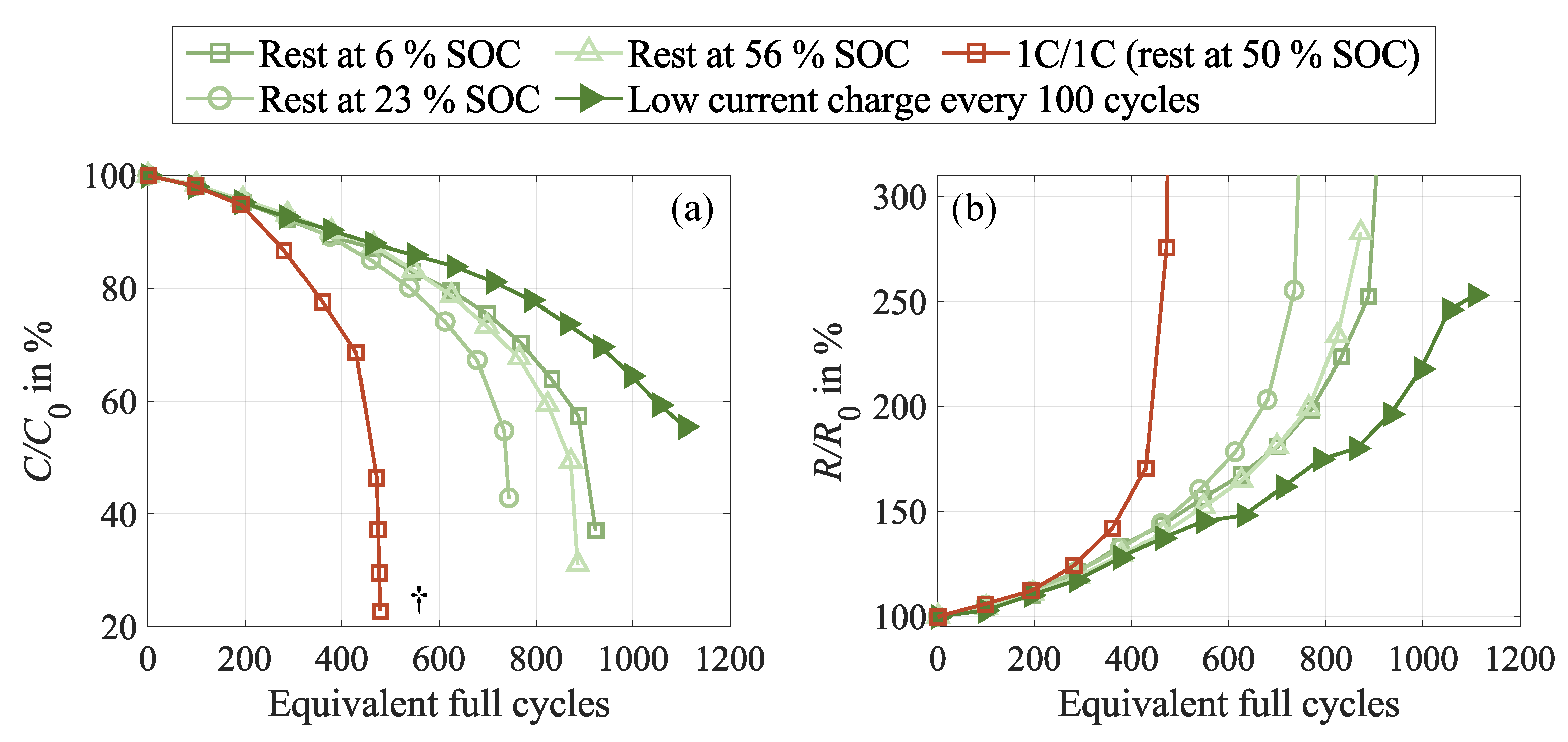

In this section, we focus on methods to actively support cell relaxation during cycling in order to compensate for the triggered inhomogenization effects. For this purpose, we investigate two approaches based on the above findings, further denoted as static and dynamic relaxation. As shown in

Figure 11, both methods (green curves) positively impact cell behavior in terms of capacity loss and resistance increase, significantly enhancing the cycle life performance. This becomes particularly clear when comparing them to the 1C/1C case from substudy 2 (red curve), with more than double the completed equivalent full cycles in the best-performing case until a relative capacity of 70 . All test cases exhibit identical cycling procedures and only differ in the relaxation conditions. While the relaxation in the 1C/1C test case was performed at 50 SOC representing the average SOC during cycling, the rest conditions in the recovery cycles were explicitly designed to support cell relaxation.

The first approach focuses on optimizing static relaxation, which has been shown to positively impact cell homogenization and degradation, as presented in

Section 3.2. In contrast to the 1C/1C test case, the rest SOC are located in ranges of high potential gradients in the negative electrode to trigger equalization processes in case of local lithiation differences. As evident in

Figure 11, the rest SOC at 6 and 56 have a higher beneficial impact on cell behavior than the rest SOC at 23 . This is consistent with all analysis techniques applied in this work. However, the electro-chemical reason for this behavior remains unclear from the data presented and requires further analysis.

The second approach, denoted as dynamic relaxation, is based on a low-current charging sequence instead of resting at a specific SOC, which seems to obtain better results. The idea behind the dynamic relaxation cycle is to pass through different potential regions of the negative electrode in order to provide states with sufficient potential gradients, which trigger lithium redistribution processes in the case of local SOC inhomogeneities. In contrast to the static approach, this is not as sensitive to the precise storage SOC level, which might shift throughout the cycle aging test due to reversible and irreversible capacity loss.

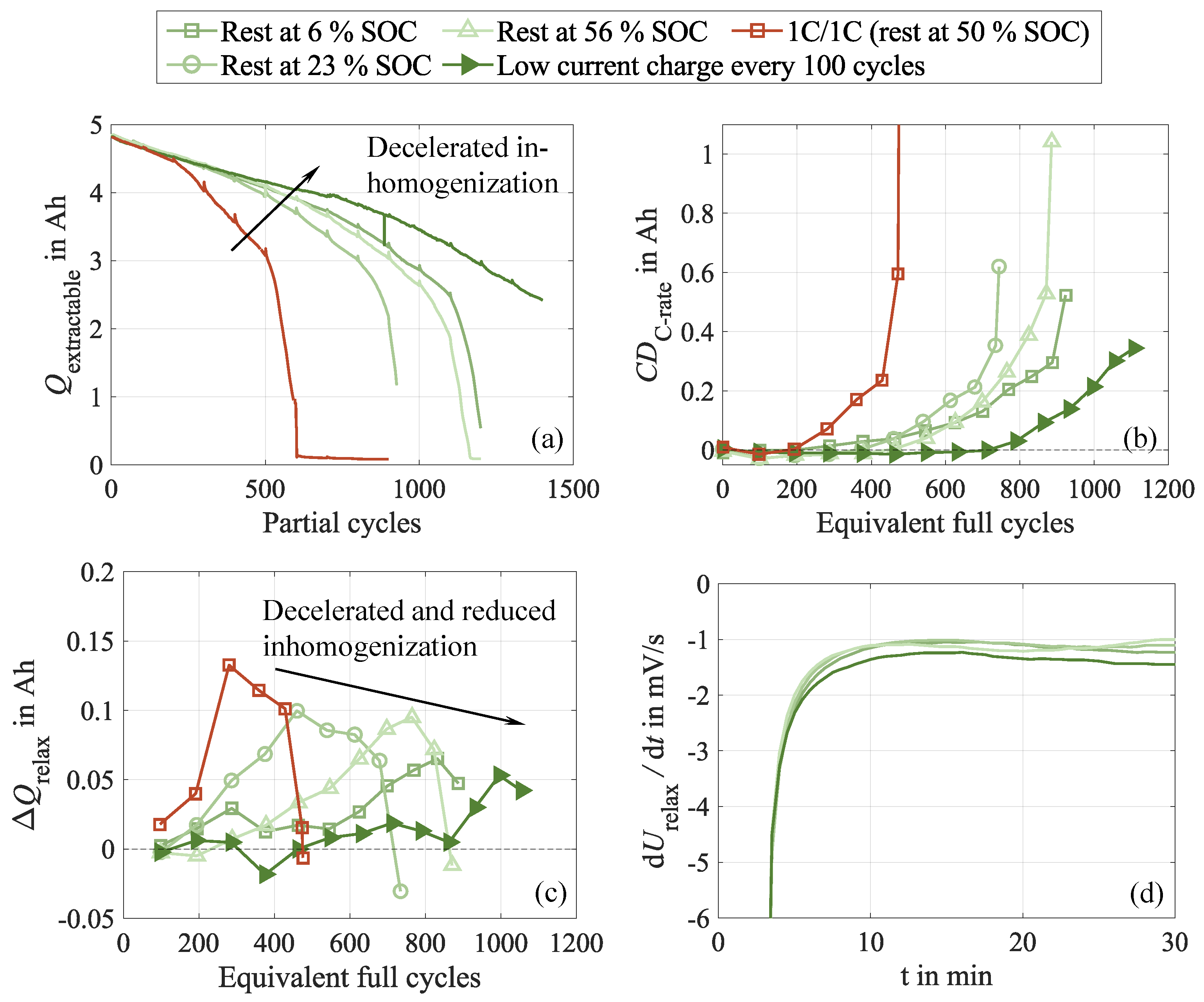

The capacity difference

between low and high current discharge, shown in

Figure 12 (b), accurately reflects the observed aging behavior. More severely degraded cells exhibit earlier and faster-growing capacity differences. This is in agreement with the extractable charge during cycling, depicted in

Figure 12 (a). For the test cases with optimized relaxation, it remains considerably higher throughout the entire test, while it significantly declines in the 1C/1C case without optimized relaxation. This observation suggests that the relaxation cycles effectively suppress the earlier discussed cell inhomogenization, which reduces the lateral lithium flow and better preserves the extractable amount of charge. The behavior of the cell with dynamic relaxation is particularly noteworthy, as it exhibits a negligible capacity difference until approximately 800 EFC and almost no signs of recovered charge during CU and rest up to this test progress, indicating a highly beneficial impact of this method.

As shown in

Figure 12 (c), the recovered amounts of charge confirm the previously observed trend. The faster the capacity fades, the faster and more pronounced the recovered charge increases. Once a critical cell condition is reached, the recovered capacity surpasses its peak and rapidly drops. This behavior coincides with the occurrence of the knee point, thus suggesting that reversible effects intensify with progressive cycling and rehomogenization during cycling becomes increasingly incomplete. At this tipping point, the reversible behavior seems to become irreversible and cause subsequent rapid cell failure. The stripping potential analysis, visualized in

Figure 12 (d), reveals characteristic plateaus at the end of the cycle aging test, indicating the occurrence of lithium plating in all test cases, which is in alignment with the other substudies. Overall, the analysis demonstrates that the applied recovery cycles effectively reduce the inhomogenization rate and delay the critical tipping point.

3.5. Implications of Cell Inhomogenization and Relaxation on Cycle Life

Summarizing and connecting the findings from the four substudies under diverse impacting factors presented above reveals a characteristic cell behavior and suggests a common specific mechanism influencing cycle life performance.

Figure 13 visualizes the correlation of capacity fade, capacity difference, and the amount of recovered capacity during CU and rest. This behavior is evident in nearly all test cases, with variations only in the timing of characteristic events.

Firstly, a high correlation between the capacity loss and the increasing capacity difference is evident from

Figure 13 (a) and (b). The capacity difference results from inhomogeneous electrode lithiation and represents a reversible loss of lithium. Consequently, this correlation indicates the strong superimposition of reversible losses and the measured capacity fade. A growing share of reversible losses becomes evident, especially towards the end of the tests, where the capacity difference significantly increases. This implies an aggravating inhomogenization of the negative electrode and is in line with the literature, where increasing inhomogeneity with progressive cycling has been reported [

9,

21].

Secondly, the capacity differences coincide with the progression of the recovered charge and the relaxed end of discharge voltage during CUs and rest. The aggravated inhomogeneities mentioned above lead to increasing equalization intensities of concentration gradients and the redistribution of lithium within the negative electrode during CUs and rest. This manifests in growing amounts of recovered charge during low-current operation and rest. As the comparison of

Figure 13 (b) and (c) shows, the significant increase in the capacity difference occurs around the peak values of this recovered charge, indicating a change in the underlying cell behavior.

Finally, the first capturable signs of lithium stripping occur two or three CU before the last data point. This coincides with the peak in the recovered capacity or shortly before, suggesting lithium plating is triggered once a critical degree of inhomogeneity is surpassed. However, based on the data, only the earliest occurrence of lithium stripping can be identified, proving that lithium plating must have occurred beforehand. The onset of lithium plating, in contrast, cannot be determined.

The 2C/2C test case differs from this characteristic behavior, not showing a drop in

and any signs of lithium stripping. Nevertheless, severe lithium plating is assumed in this cell, which would explain the early cell failure after approximately 350 EFC and is in alignment with the high currents applied. Moreover, the DOD test cases of 40 and below don’t evince significant capacity differences,

, and indicators of lithium stripping. This supports the previously outlined theory, as it demonstrates that inhomogeneous cell conditions correlate with and precede lithium stripping. However, in these test cases, the cyclic stresses appear to be mild enough to prevent significant inhomogenization, which aligns with earlier findings in the literature [

9,

16].

This leads to the question of which stress factor influences cell inhomogenization the most. From the data presented in this study, C-rates appear to have the highest impact. However, the data suggests a certain minimum DOD is required to trigger the observed mechanism. This is plausible, as one key process is the EMSI effect, which results from volume changes of the negative electrode and, therefore, is enhanced by increasing cycle depths. However, the data presented is obtained from only a few test cases, which allows for deriving only generic high-level trends. Revealing detailed stress factor impacts and analyzing respective trends, in contrast, requires a comprehensive parameter study, particularly considering various C-rate and DOD combinations. Moreover, further stress factors need to be considered.

Evaluating the investigated recovery methods emphasizes an overall positive impact on cycle life performance and cell homogeneity, particularly with the dynamic strategy. An additional advantage of this procedure is that intermediate low-current charge cycles can easily be integrated into the cycle aging test and provide valuable measurement data, which gives further insights into the cell behavior, e.g., through DVA. Apart from that, resting in the very low SOC range or around the graphite stage II phase transition proves effective. Analogous to the influence of stress factors, it needs to be considered that the data presented is not the result of a parameter study or optimization. The static method could yield better outcomes under optimized conditions, e.g., rest SOC, duration, and temperature. As diffusion and equalization effects follow the Arrhenius correlation, better and faster results could be obtained at elevated temperatures. Consequently, relaxation cycles could be carried out at higher temperatures. Moreover, intermediate charging pulses have been reported to positively impact equalization processes [

14,

47] and therefore could offer further potential for intermediate cell rehomogenization.