Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Outcomes

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Collection

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Qualitative Synthesis

2.6.2. Quantitative Synthesis

- Random selection of one treatment intervention: Instead of combining interventions belonging to the same intervention category, as in the main analysis, we randomly selected only one.

- Removal of SBS test results: Instead of including all bond strength tests, as in the main analysis, we included only results from µSBS and µTBS tests.

3. Results and Discussion

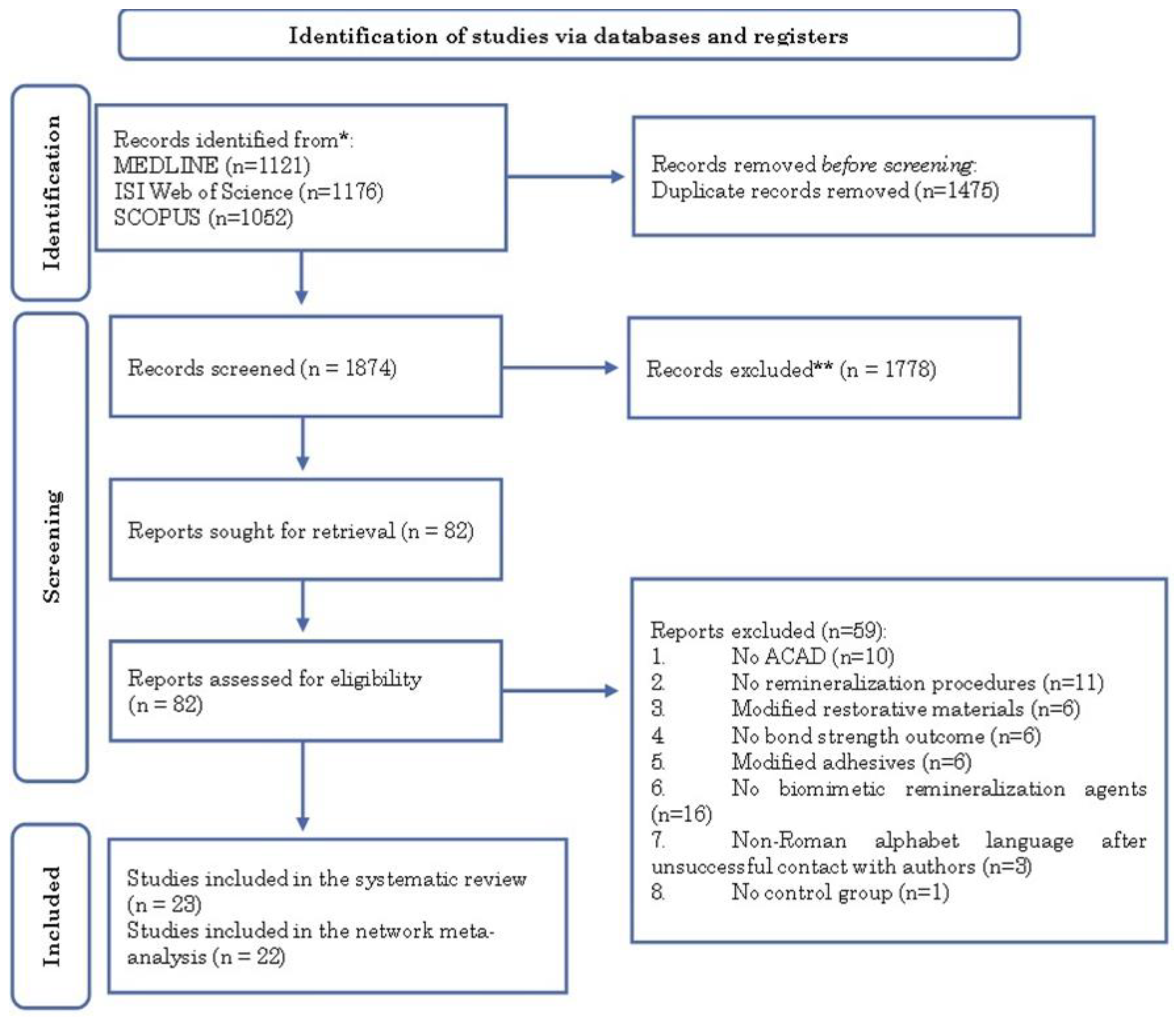

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Meta-Regressions

3.3.1. Influence of the Adhesive Technique on NMA Effect Estimates

3.3.2. Influence of the ACAD Protocol on NMA Effect Estimates

3.4. Network Meta-Analysis

3.4.1. ER Technique with Chemical ACAD Protocol

3.4.2. ER Technique with Biological ACAD Protocol

3.4.3. SE Technique with Chemical ACAD Protocol

3.5. NMA Confidence Ratings

3.5.1. ER Technique with Chemical ACAD Protocol

3.5.2. ER Technique with Biological ACAD Protocol

3.5.3. SE Technique with Chemical ACAD Protocol

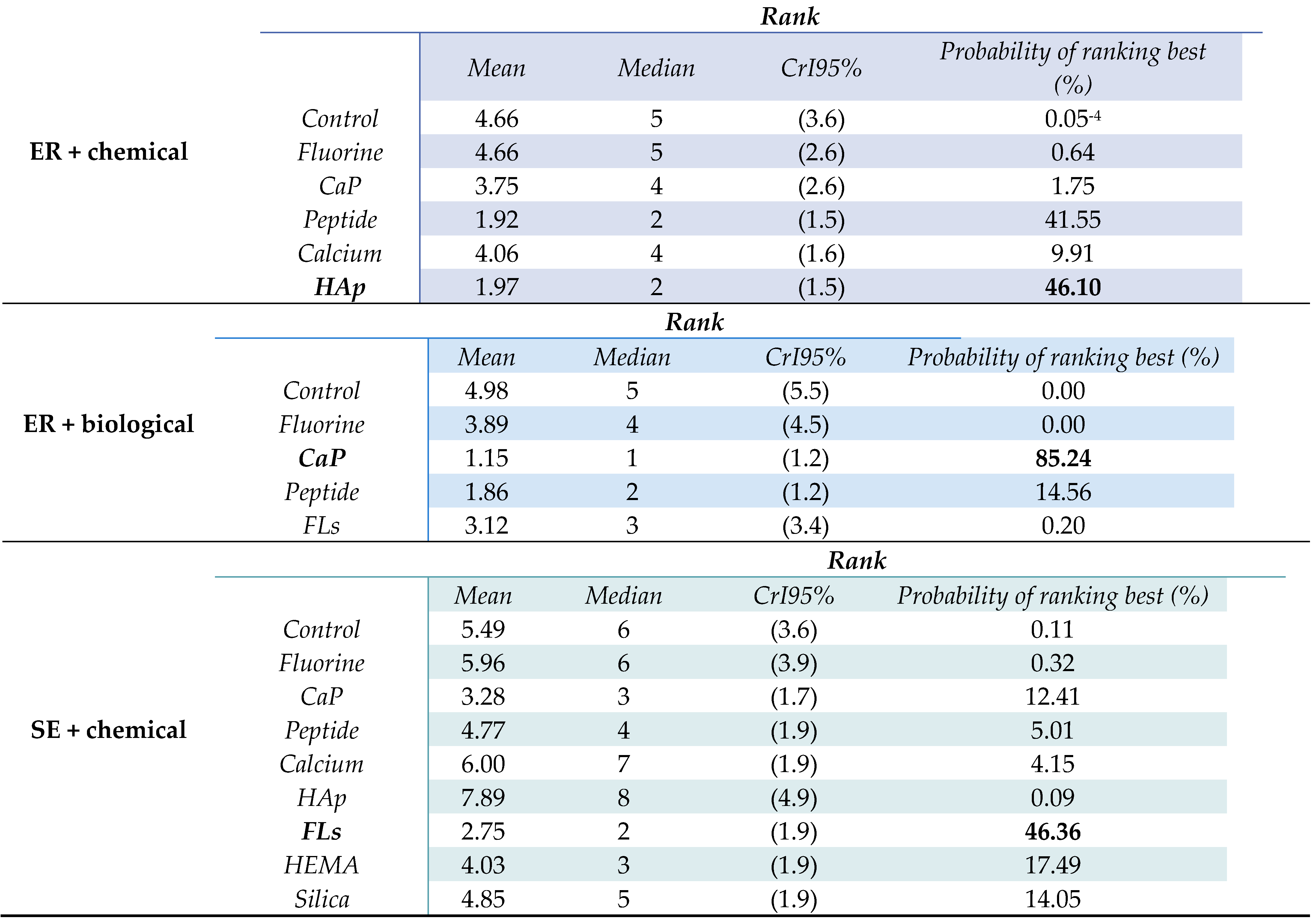

3.6. Rankings

3.6.1. ER Technique with Chemical ACAD Protocol

3.6.2. ER Technique with Biological ACAD Protocol

3.6.3. SE Technique with Chemical ACAD Protocol

3.7. Sensitivity Analyses

3.7.1. ER Technique with Chemical ACAD Protocol

3.7.2. ER Technique with Biological ACAD Protocol

3.7.3. SE Technique with Chemical ACAD Protocol

3.8. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMA | Network Meta-analysis |

| ACAD | Artificial caries-affected dentin |

| BR | Biomimetic remineralization |

Appendix 1

1. Search Strategies

| Studies | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Doozandeh et al. (2015)[61] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Bergamin et al. (2016)[62] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Ghani et al. (2017)[63] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Komori et al. (2009) [64] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Leal et al. (2017)[65] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Luong et al. (2020)[66] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Meraji et al. (2018)[67] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Prasansuttiporn et al. (2020)[68] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Sajjad et al. (2022)[69] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Yilmaz et al. (2017)[70] | 1-Without ACAD |

| Castellan et al. (2010)[71] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Okuyama et al. (2011)[72] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Wang et al. (2012)[73] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| de-Melo et al. (2013)[74] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Carvalho et al. (2016)[75] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Deari et al. (2017)[76] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Giacomini et al. (2017)[77] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Rodrigues et al. (2017)[78] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Imiolczyk et al. (2017)[79] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Stape et al. (2021)[80] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Hartz et al. (2022)[81] | 2- Without remineralization procedures |

| Wang et al. (2016)[82] | 3-Modified Materials |

| Moda et al (2018)[83] | 3-Modified Materials |

| Choi et al. (2020)[84] | 3-Modified Materials |

| Abdelshafi et al. (2021) [85] | 3-Modified Materials |

| Al-Qahtani et al. (2021)[86] | 3-Modified Materials |

| Khor et al. (2022)[87] | 3-Modified Materials |

| Adebayo et al. (2010)[88] | 4- Without bond strength measurement |

| Liu et al. (2011)[89] | 4- Without bond strength measurement |

| Chen et al. (2016)[90] | 4- Without bond strength measurement |

| Bortolotto et al. (2017)[91] | 4- Without bond strength measurement |

| Liang et al. (2017)[92] | 4- Without bond strength measurement |

| Wang et al. (2021)[93] | 4- Without bond strength measurement |

| Zhou et al. (2016) [94] | 5- Modified adhesive |

| Flury et al (2017)[95] | 5- Modified adhesive |

| Ye et al. (2017)[96] | 5- Modified adhesive |

| Liang et al. (2018) [97] | 5- Modified adhesive |

| Cardenas et al. (2021) [38] | 5- Modified adhesive |

| Hasegawa et al. (2021)[98] | 5- Modified adhesive |

| Bridi et al (2012)[99] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Castellan et al (2013)[100] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Monteiro et al (2013)[101] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Abu Nawareg et al (2016)[102] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Lee et al (2017)[103] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Prasansuttiporn et al (2017)[104] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Ramezanian Nik et al (2017)[105] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Costa et al (2019)[106] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Fialho et al (2019)[107] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Landmayer et al (2020) [108] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Costa et al (2021)[109] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Giacomini et al (2021)[110] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Shioya et al (2021)[111] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Xu et al (2021)[112] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Atay et al (2022)[113] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Lemos et al (2022)[114] | 6- Not biomimetic remineralization agents |

| Zhang et al (2015)[115] | 7-Non-Roman Alphabet language after unsuccessful contact with authors |

| Wang et al (2017)[116] | 7-Non-Roman Alphabet language after unsuccessful contact with authors |

| Meng et al (2022)[117] | 7-Non-Roman Alphabet language after unsuccessful contact with authors |

| Kim et al (2020)[13] | 8- Missing control group |

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Atomura et al (2018)[32] | Standard Deviation and sample size (N) missing and authors didn´t respond to the various emails. |

| Study | Data Information |

|---|---|

| Zumstein et al. (2018)[42] | Missing data obtained from another Meta-Analysis by Wiegand et al.2021 [50]. Authors didn´t respond to the various emails. |

| Study | Data Information |

|---|---|

| Barbosa-Martins et al. (A) (2018)[8] | Unit of statistical analysis |

| Barbosa-Martins et al. (B) (2018)[7] | Unit of statistical analysis |

| de Sousa et al. (2019)[33] | Unit of statistical analysis |

| Moreira et al. (2021)[15] | Unit of statistical analysis |

| Meng et al. (2021) [24] | Mean and SD values |

| Pei et al. (2019)[26] | Unit of statistical analysis |

| Pulidindi et al. (2021) [40] | Unit of statistical analysis |

| Yang et al. (2018)[29] | Mean and SD values and Unit of statistical analysis |

| Zang et al. (2018)[30] | Mean and SD values and Unit of statistical analysis |

2. OpenBUGS Code for Random Effects Meta-Regression Model with a Subgroup Indicator Covariate

3. Meta-Regression

| NMA comparison | Mean | 95% CrI |

|---|---|---|

| CTRL:F | 0.8846 | (-1.72; 3.52) |

| CTRL:CaP | -3.351 | (-6.664; -0.03009) |

| CTRL:Pept. | -5.384 | (-9.103; -1.65) |

| CTRL:SiO2 | -0.8296 | (-10.72; 9.049) |

| CTRL:HEMA | -1.728 | (-10.22; 6.768) |

| CTRL:FLs | -4.982 | (-12.35; 2.382) |

| CTRL:Ca | 0.3152 | (-5.575; 6.211) |

| CTRL:HAp | 1.223 | (-2.536; 4.98) |

| F:CaP | -4.236 | (-7.499; -0.9842) |

| F:Pept. | -6.268 | (-9.996; -2.552) |

| F:SiO2 | -1.714 | (-11.95; 8.521) |

| F:HEMA | -2.613 | (-11.1; 5.868) |

| F:FLs | -5.867 | (-13.45; 1.726) |

| F:Ca | -0.5694 | (-6.352; 5.196) |

| F:HAp | 0.3381 | (-3.942; 4.631) |

| CaP:Pept. | -2.032 | (-5.601; 1.525) |

| CaP:SiO2 | 2.522 | (-7.906; 12.94) |

| CaP:HEMA | 1.623 | (-7.297; 10.54) |

| CaP:FLs | -1.631 | (-9.428; 6.172) |

| CaP:Ca | 3.666 | (-2.196; 9.529) |

| CaP:HAp | 4.574 | (-0.07638; 9.248) |

| Pept.:SiO2 | 4.554 | (-6.013; 15.1) |

| Pept.:HEMA | 3.656 | (-5.425; 12.76) |

| Pept.:FLs | 0.4015 | (-7.578; 8.394) |

| Pept.:Ca | 5.699 | (-0.6984; 12.08) |

| Pept.:HAp | 6.606 | (1.658; 11.56) |

| SiO2:HEMA | -0.8984 | (-13.94; 12.13) |

| SiO2:FLs | -4.153 | (-16.46; 8.18) |

| SiO2:Ca | 1.145 | (-10.37; 12.64) |

| SiO2:HAp | 2.052 | (-8.496; 12.66) |

| HEMA:FLs | -3.254 | (-14.41; 7.904) |

| HEMA:Ca | 2.043 | (-8.051; 12.17) |

| HEMA:HAp | 2.951 | (-6.264; 12.18) |

| FLs:Ca | 5.297 | (-3.932; 14.52) |

| FLs:HAp | 6.205 | (-1.944; 14.31) |

| Ca:HAp | 0.9075 | (-5.872; 7.675) |

| NMA comparison | Mean | 95% CrI |

|---|---|---|

| CTRL:F | -7.588 | (-11.3; -3.877) |

| CTRL:CaP | -12.97 | (-17.32; -8.628) |

| CTRL:Pept. | -14.2 | (-18.64; -9.77) |

| CTRL:SiO2 | -10.15 | (-20.78; 0.5214) |

| CTRL:HEMA | -10.62 | (-19.71; -1.499) |

| CTRL:FLs | -11.2 | (-18.69; -3.706) |

| CTRL:Ca | -9.321 | (-15.94; -2.717) |

| CTRL:HAp | -9.208 | (-14.65; -3.78) |

| F:CaP | -5.381 | (-8.621; -2.139) |

| F:Pept. | -6.617 | (-10.3; -2.935) |

| F:SiO2 | -2.563 | (-12.68; 7.6) |

| F:HEMA | -3.031 | (-11.43; 5.39) |

| F:FLs | -3.61 | (-11.2; 3.981) |

| F:Ca | -1.734 | (-7.48; 3.999) |

| F:HAp | -1.62 | (-5.972; 2.749) |

| CaP:Pept. | -1.236 | (-4.793; 2.332) |

| CaP:SiO2 | 2.818 | (-7.433; 13.12) |

| CaP:HEMA | 2.35 | (-6.401; 11.14) |

| CaP:FLs | 1.77 | (-6.08; 9.585) |

| CaP:Ca | 3.647 | (-2.149; 9.428) |

| CaP:HAp | 3.761 | (-0.8584; 8.391) |

| Pept.:SiO2 | 4.055 | (-6.382; 14.52) |

| Pept.:HEMA | 3.586 | (-5.386; 12.55) |

| Pept.:FLs | 3.007 | (-4.964; 10.97) |

| Pept.:Ca | 4.884 | (-1.454; 11.21) |

| Pept.:HAp | 4.997 | (-0.001725; 10.01) |

| SiO2 :HEMA | -0.4682 | (-13.38; 12.48) |

| SiO2:FLs | -1.048 | (-13.4; 11.32) |

| SiO2:Ca | 0.829 | (-10.56; 12.18) |

| SiO2:HAp | 0.9427 | (-9.562; 11.42) |

| HEMA:FLs | -0.5796 | (-11.75; 10.58) |

| HEMA:Ca | 1.297 | (-8.708; 11.3) |

| HEMA:HAp | 1.411 | (-7.759; 10.56) |

| FLs:Ca | 1.877 | (-7.369; 11.12) |

| FLs:HAp | 1.991 | (-6.31; 10.31) |

| Ca:HAp | 0.1137 | (-6.606; 6.846) |

4. Contribution Tables

| NMA treatment effect/ comparisons | Ca:CaP | Ca:CTRL | Ca:F | CaP:CTRL | CaP:F | CaP:Pept. | CTRL:F | CTRL:HAp | CTRL:Pept. | F:Pept. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed estimates | ||||||||||

| CaP:CTRL | 2.935 | 2.375 | 0.56 | 63.32 | 7.4 | 7.4783 | 8.4533 | 0 | 6.985 | 0.4933 |

| CaP:F | 4.195 | 0.0675 | 4.2625 | 22.975 | 31.11 | 6.1242 | 25.1317 | 0 | 2.2242 | 3.9 |

| CaP:Pept. | 1.1317 | 0.6967 | 0.435 | 16.795 | 5.04 | 52.39 | 0.535 | 0 | 18.0267 | 4.94 |

| Ca:CaP | 38.27 | 15.92 | 11.94 | 17.4467 | 7.655 | 2.7583 | 3.2517 | 0 | 1.725 | 1.0333 |

| Ca:CTRL | 15.095 | 36.58 | 15.3917 | 13.445 | 0.125 | 1.775 | 14.73 | 0 | 2.3117 | 0.5367 |

| Ca:F | 12.5817 | 15.78 | 38.56 | 3.1633 | 7.905 | 1.5133 | 18.9033 | 0 | 0.04 | 1.5533 |

| CTRL:F | 0.5775 | 2.515 | 3.0925 | 8.505 | 8.155 | 0.2275 | 70.38 | 0 | 3.3875 | 3.16 |

| CTRL:HAp | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| CTRL:Pept. | 0.8633 | 0.8783 | 0.015 | 14.86 | 1.5317 | 17.255 | 7.2017 | 0 | 51.7 | 5.685 |

| F:Pept. | 1.5167 | 0.5925 | 2.1092 | 3.9225 | 10.465 | 15.9042 | 25.565 | 0 | 22.235 | 17.69 |

| Indirect estimates | ||||||||||

| CaP:HAp | 2.0033 | 1.5833 | 0.42 | 31.66 | 4.9333 | 5.0267 | 5.7233 | 43.6233 | 4.6567 | 0.37 |

| Ca:HAp | 10.2008 | 18.29 | 10.3225 | 8.9633 | 0.1 | 1.3375 | 9.82 | 38.8133 | 1.74 | 0.4025 |

| Ca:Pept. | 17.22 | 16.965 | 12.4708 | 0.7075 | 1.7067 | 19.6342 | 4.2742 | 0 | 20.5317 | 6.49 |

| F:HAp | 0.4445 | 1.6767 | 2.1212 | 5.6992 | 5.4367 | 0.182 | 35.19 | 44.8545 | 2.2887 | 2.1067 |

| HAp:Pept. | 0.6475 | 0.6595 | 0.012 | 9.9067 | 1.1495 | 11.7037 | 4.9275 | 41.3437 | 25.85 | 3.79 |

| NMA treatment effect/ comparisons | CaP:CTRL | CaP:F | CaP:Pept. | CTRL:FLs | CTRL:F | CTRL:Pept. | F:Pept. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed estimates | |||||||

| CaP:CTRL | 47.08 | 13.7 | 12.3317 | 0 | 14.5567 | 11.475 | 0.8567 |

| CaP:F | 17.525 | 40.42 | 11.1833 | 0 | 19.6783 | 2.1533 | 9.03 |

| CaP:Pept. | 16.035 | 11.5217 | 43.84 | 0 | 1.0367 | 17.0717 | 10.485 |

| CTRL:FLs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CTRL:F | 6.015 | 6.345 | 0.33 | 0 | 71.49 | 8.075 | 7.745 |

| CTRL:Pept. | 7.505 | 1.1033 | 8.6083 | 0 | 12.8783 | 58.13 | 11.775 |

| F:Pept. | 0.9933 | 8.17 | 9.1633 | 0 | 21.8183 | 20.825 | 39.04 |

| Indirect estimates | |||||||

| CaP:FLs | 23.54 | 9.1333 | 8.2925 | 40.9658 | 9.7758 | 7.65 | 0.6425 |

| FLs:F | 4.01 | 4.2575 | 0.2475 | 45.1658 | 35.745 | 5.4108 | 5.1633 |

| FLs:Pept. | 5.0033 | 0.8275 | 5.8308 | 42.7458 | 8.6775 | 29.065 | 7.85 |

| NMA treatment effect/ comparisons | Ca:CaP | Ca:CTRL | Ca:F | CaP:CTRL | CaP:F | CaP:Pept. | CTRL: FLS | CTRL:F | CTRL: HEMA | CTRL:HAp | CTRL:Pept. | CTRL:SiO2 | F:HEMA | F:Pept. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed estimates | ||||||||||||||

| CaP:CTRL | 5.215 | 3.955 | 1.26 | 51.94 | 9.345 | 8.4575 | 0 | 10.425 | 0.4725 | 0 | 8.165 | 0 | 0.4725 | 0.2925 |

| CaP:F | 6.4433 | 0.7333 | 5.71 | 20.78 | 29.56 | 5.3175 | 0 | 23.9333 | 1.1025 | 0 | 3.5225 | 0 | 1.1025 | 1.795 |

| CaP:Pept. | 1.9783 | 1.3433 | 0.635 | 14.09 | 4.5933 | 54.07 | 0 | 2.3683 | 0.13 | 0 | 17.932 | 0 | 0.13 | 2.73 |

| Ca:CaP | 41.85 | 14.96 | 11.2705 | 15.37 | 8.04 | 2.8205 | 0 | 2.5325 | 0.168 | 0 | 2.2905 | 0 | 0.168 | 0.53 |

| Ca:CTRL | 13.2408 | 37.83 | 16.005 | 10.395 | 0.6525 | 2.1933 | 0 | 15.825 | 0.6925 | 0 | 2.3333 | 0 | 0.6925 | 0.14 |

| Ca:F | 11.2397 | 16.065 | 39.64 | 3.365 | 6.74 | 1.1347 | 0 | 19.125 | 0.773 | 0 | 0.468 | 0 | 0.773 | 0.6667 |

| CTRL:FLs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CTRL:F | 0.4375 | 2.85 | 3.2875 | 5.19 | 5.3533 | 0.6008 | 0 | 72.96 | 3.15 | 0 | 1.8108 | 0 | 3.15 | 1.21 |

| CTRL:HEMA | 0.174 | 0.9567 | 1.1307 | 1.74 | 1.8025 | 0.2365 | 0 | 18.35 | 52.86 | 0 | 0.6432 | 0 | 21.6898 | 0.4067 |

| CTRL:HAp | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CTRL:Pept. | 1.553 | 1.29 | 0.263 | 11.88 | 2.5467 | 15.9797 | 0 | 5.8717 | 0.248 | 0 | 56.8 | 0 | 0.248 | 3.31 |

| CTRL:SiO2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| F:HEMA | 0.174 | 0.9433 | 1.1173 | 1.72 | 1.78 | 0.234 | 0 | 18.125 | 21.4223 | 0 | 0.634 | 0 | 53.44 | 0.4 |

| F:Pept. | 2.31 | 0.455 | 2.765 | 3.8833 | 9.255 | 15.4483 | 0 | 28.2333 | 1.265 | 0 | 26.07 | 0 | 1.265 | 9.05 |

| Indirect estimates | ||||||||||||||

| CaP:FLs | 3.5907 | 2.6367 | 0.954 | 25.97 | 6.23 | 5.6773 | 41.468 | 7.04 | 0.378 | 0 | 5.4433 | 0 | 0.378 | 0.234 |

| CaP:HEMA | 4.1842 | 1.6142 | 2.57 | 23.36 | 12.08 | 4.2917 | 0 | 3.6925 | 24.7767 | 0 | 3.495 | 0 | 19.1392 | 0.7967 |

| CaP:HAp | 3.5907 | 2.6367 | 0.954 | 25.97 | 6.23 | 5.6773 | 0 | 7.04 | 0.378 | 41.468 | 5.4433 | 0 | 0.378 | 0.234 |

| CaP:SiO2 | 3.5907 | 2.6367 | 0.954 | 25.97 | 6.23 | 5.6773 | 0 | 7.04 | 0.378 | 0 | 5.4433 | 41.468 | 0.378 | 0.234 |

| Ca:FLs | 9.097 | 18.915 | 10.685 | 6.93 | 0.522 | 1.645 | 38.697 | 10.55 | 0.552 | 0 | 1.75 | 0 | 0.552 | 0.105 |

| Ca:HEMA | 8.9795 | 17.48 | 17.97 | 5.1542 | 2.6933 | 1.132 | 0 | 1.0295 | 22.5367 | 0 | 0.932 | 0 | 21.8928 | 0.2 |

| Ca:HAp | 9.097 | 18.915 | 10.685 | 6.93 | 0.522 | 1.645 | 0 | 10.55 | 0.552 | 38.697 | 1.75 | 0 | 0.552 | 0.105 |

| Ca:Pept. | 17.575 | 16.975 | 11.148 | 0.668 | 1.6767 | 19.9197 | 0 | 5.6533 | 0.298 | 0 | 22.258 | 0 | 0.298 | 3.52 |

| Ca:SiO2 | 9.097 | 18.915 | 10.685 | 6.93 | 0.522 | 1.645 | 0 | 10.55 | 0.552 | 0 | 1.75 | 38.697 | 0.552 | 0.105 |

| FLs:F | 0.35 | 1.9 | 2.25 | 3.46 | 3.5825 | 0.4725 | 45.2192 | 36.48 | 2.1 | 0 | 1.2792 | 0 | 2.1 | 0.8067 |

| FLs:HEMA | 0.145 | 0.7175 | 0.8625 | 1.305 | 1.355 | 0.195 | 41.1858 | 12.2333 | 26.43 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 14.7558 | 0.305 |

| FLs:HAp | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FLs:Pept. | 1.1862 | 0.9675 | 0.2187 | 7.92 | 1.91 | 11.0162 | 41.6228 | 4.1287 | 0.2067 | 0 | 28.4 | 0 | 0.2067 | 2.2067 |

| FLs:SiO2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| F:HAp | 0.35 | 1.9 | 2.25 | 3.46 | 3.5825 | 0.4725 | 0 | 36.48 | 2.1 | 45.2192 | 1.2792 | 0 | 2.1 | 0.8067 |

| F:SiO2 | 0.35 | 1.9 | 2.25 | 3.46 | 3.5825 | 0.4725 | 0 | 36.48 | 2.1 | 0 | 1.2792 | 45.2192 | 2.1 | 0.8067 |

| HEMA:HAp | 0.145 | 0.7175 | 0.8625 | 1.305 | 1.355 | 0.195 | 0 | 12.2333 | 26.43 | 41.1858 | 0.5 | 0 | 14.7558 | 0.305 |

| HEMA:Pept. | 1.4625 | 0.2 | 1.2625 | 4.635 | 4.37 | 10.4675 | 0 | 5.7817 | 25.81 | 0 | 26.757 | 0 | 15.3342 | 3.92 |

| HEMA:SiO2 | 0.145 | 0.7175 | 0.8625 | 1.305 | 1.355 | 0.195 | 0 | 12.2333 | 26.43 | 0 | 0.5 | 41.1858 | 14.7558 | 0.305 |

| HAp:Pept. | 1.1862 | 0.9675 | 0.2187 | 7.92 | 1.91 | 11.0162 | 0 | 4.1287 | 0.2067 | 41.623 | 28.4 | 0 | 0.2067 | 2.2067 |

| HAp:SiO2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Pept.:SiO2 | 1.1862 | 0.9675 | 0.2187 | 7.92 | 1.91 | 11.0162 | 0 | 4.1287 | 0.2067 | 0 | 28.4 | 41.6228 | 0.2067 | 2.2067 |

5. Confidence Ratings Output of CINeMA Software

| Comparison | Number of studies | Within-study bias | Reporting bias | Indirectness | Imprecision | Heterogeneity | Incoherence | Confidence rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed estimates | ||||||||

| CaP:CTRL | 1 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Major concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Low |

| CaP:F | 1 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Major concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Low |

| CaP:Pept. | 1 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Major concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Low |

| Ca:CaP | 7 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | No concerns | Low |

| Ca:CTRL | 3 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | Major concerns | Very low |

| Ca:F | 4 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| CTRL:F | 8 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | Major concerns | Very low |

| CTRL:HAp | 3 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | Low |

| CTRL:Pept. | 4 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| F:Pept. | 2 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| Indirect estimates | ||||||||

| CaP:HAp | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Major concerns | Low |

| Ca:HAp | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Major concerns | Low |

| Ca:Pept. | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Major concerns | Low |

| F:HAp | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Major concerns | Low |

| HAp:Pept. | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Major concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | Very low |

| ER with Biological | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Number of studies | Within-study bias | Reporting bias | Indirectness | Imprecision | Heterogeneity | Incoherence | Confidence rating |

| Mixed estimates | ||||||||

| CaP:CTRL | 2 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| CaP:F | 2 | Some concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| CaP:Pept. | 2 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| CTRL:FLs | 1 | Some concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| CTRL:F | 4 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| CTRL:Pept. | 3 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| F:Pept. | 2 | Some concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| Indirect estimates | ||||||||

| CaP:FLs | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| FLs:F | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| FLs:Pept. | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| SE with Chemical | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Number of studies | Within-study bias | Reporting bias | Indirectness | Imprecision | Heterogeneity | Incoherence | Confidence rating |

| Mixed estimates | ||||||||

| CaP:CTRL | 1 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| CaP:F | 1 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| CaP:Pept. | 1 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | No concerns | Low |

| Ca:CaP | 4 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| Ca:CTRL | 2 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| Ca:F | 3 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | No concerns | Low |

| CTRL:FLs | 1 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| CTRL:F | 8 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Moderate |

| CTRL:HEMA | 1 | Major concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Low |

| CTRL:HAp | 5 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| CTRL:Pept. | 3 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| CTRL:SiO2 | 1 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | Some concerns | Low |

| F:HEMA | 1 | Major concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | No concerns | Low |

| F:Pept. | 1 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Major concerns | Low |

| Indirect estimates | ||||||||

| CaP:FLs | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| CaP:HEMA | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| CaP:HAp | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| CaP:SiO2 | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| Ca:FLs | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| Ca:HEMA | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| Ca:HAp | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | Some concerns | Low |

| Ca:Pept. | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| Ca:SiO2 | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| FLs:F | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| FLs:HEMA | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| FLs:HAp | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| FLs:Pept. | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| FLs:SiO2 | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| F:HAp | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| F:SiO2 | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| HEMA:HAp | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| HEMA:Pept. | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | No concerns | Major concerns | Some concerns | Low |

| HEMA:SiO2 | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| HAp:Pept. | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

| HAp:SiO2 | 0 | Some concerns | Low risk | No concerns | Some concerns | No concerns | Some concerns | Moderate |

6. Sensitivity Analyses

| RANDOM | Calcium | |||||

| 1.106 ( -7.711, 9.922) | CaP | |||||

| -0.123 ( -8.738, 8.491) | -1.229 ( -5.371, 2.913) | Control | ||||

| -1.291 (-10.094, 7.512) | -2.397 ( -7.595, 2.802) | -1.168 ( -5.227, 2.892) | Fluorine | |||

| 5.813 ( -4.953, 16.580) | 4.707 ( -2.965, 12.380) | 5.937 ( -0.522, 12.395) | 7.104 ( -0.524, 14.733) | HAp | ||

| 5.028 ( -4.929, 14.984) | 3.922 ( -1.860, 9.704) | 5.151 ( -0.520, 10.822) | 6.319 ( -0.223, 12.860) | -0.786 ( -9.381, 7.809) | Peptide | |

| WITHOUT SB | Calcium | |||||

| 1.849 (-10.377, 14.074) | CaP | |||||

| -1.065 (-12.941, 10.810) | -2.914 ( -9.377, 3.549) | Control | ||||

| -1.323 (-13.357, 10.710) | -3.172 (-10.460, 4.116) | -0.258 ( -5.532, 5.016) | Fluorine | |||

| 3.777 (-10.759, 18.313) | 1.928 ( -8.656, 12.513) | 4.842 ( -3.540, 13.225) | 5.100 ( -4.804, 15.004) | HAp | ||

| 5.947 ( -8.203, 20.096) | 4.098 ( -4.949, 13.145) | 7.012 ( -1.747, 15.771) | 7.270 ( -2.143, 16.683) | 2.170 ( -9.954, 14.293) | Peptide |

| RANDOM | Calcium phosphate | ||||

| -21.320 (-26.341, -16.299) | Control | ||||

| -11.160 (-20.061, -2.258) | 10.160 (2.810, 17.510) | Flavonoids | |||

| -17.063 (-22.451, -11.675) | 4.257 (0.806, 7.708) | -5.903 (-14.023, 2.217) | Fluorine | ||

| -2.924 ( -8.500, 2.652) | 18.396 (14.256, 22.535) | 8.236 ( -0.200, 16.672) | 14.139 (9.408, 18.870) | Peptide |

| RANDOM | Calcium | ||||||||

| 1.938 ( -2.927, 6.803) | CaP | ||||||||

| 1.437 ( -3.182, 6.057) | -0.500 (-3.617, 2.616) | Control | |||||||

| 10.407 (1.928, 18.887) | 8.470 (0.706, 16.233) | 8.970 (1.859, 16.081) | FLs | ||||||

| 0.937 ( -3.774, 5.649) | -1.000 (-4.507, 2.507) | -0.500 (-2.804, 1.804) |

-9.470 (-16.945, -1.995) |

Fluorine | |||||

| 0.768 ( -5.753, 7.290) | -1.169 (-6.806, 4.467) | -0.669 (-5.510, 4.172) |

-9.639 (-18.241, -1.036) |

-0.169 (-5.004, 4.667) | HEMA | ||||

| -3.124 ( -8.605, 2.357) | -5.061 (-9.352, -0.771) | -4.561 (-7.511, -1.611) |

-13.531 (-21.230,-5.832) |

-4.061 (-7.804, -0.318) | -3.892 (-9.561, 1.776) | HAp | |||

| 4.256 ( -1.421, 9.932) | 2.318 (-1.565, 6.201) | 2.818 (-0.994, 6.632) |

-6.152 (-14.220, 1.917) |

3.318 (-0.931, 7.568) | 3.487 (-2.601, 9.576) | 7.380 (2.559, 12.200) | Peptide | ||

| 2.277 ( -5.235, 9.789) | 0.340 (-6.354, 7.033) | 0.840 (-5.084, 6.764) |

-8.130 (-17.385, 1.125) |

1.340 (-5.016, 7.696) | .509 (-6.141, 9.159) | 5.401 (-1.217, 12.019) | -1.978 (-9.024, 5.066) | Silica | |

| WITHOUT SB | Calcium | ||||||||

| 3.937 ( -3.398, 11.273) | CaP | ||||||||

| 0.117 ( -6.760, 6.994) | -3.820 ( -9.111, 1.471) | Control | |||||||

| 4.721 ( -6.357, 15.800) | 0.784 ( -9.386, 10.954) | 4.604 ( -4.082, 13.290) | FLs | ||||||

| 0.254 ( -6.695, 7.203) | -3.684 ( -9.251, 1.884) | 0.137 ( -3.243, 3.516) | -4.467 (-13.787, 4.853) | Fluorine | |||||

| -2.875 (-10.771, 5.021) | -6.812 (-13.373, -0.252) | -2.992 ( -6.871, 0.887) | -7.596 (-17.108, 1.916) | -3.129 ( -8.273, 2.016) | HAp | ||||

| -2.811 (-11.987, 6.365) | -6.748 (-13.994, 0.498) | -2.928 ( -9.722, 3.866) | -7.532 (-18.559, 3.495) | -3.065 (-10.240, 4.111) | 0.064 ( -7.759, 7.888) | Peptide |

References

- Jr., S.E., Dentin/enamel adhesives: review of the literature. Pediatr Dent. , 2002. 24: p. 456–461.

- Tjaderhane, L., et al., Optimizing dentin bond durability: control of collagen degradation by matrix metalloproteinases and cysteine cathepsins. Dent Mater, 2013. 29(1): p. 116-35. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., et al., Mineralization strategy on dentin bond stability: a systematic review of in vitro studies and meta-analysis. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, 2021: p. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Pashley DH, T.F., Yiu, C., et al. , Collagen degradation by host-derived enzymes during aging. . J Dent Res, 2004. 83: p. 216–221.

- Pashley, D.H., et al., State of the art etch-and-rinse adhesives. Dent Mater, 2011. 27(1): p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Carrilho MRO, G.S., Tay FR, de Goes MF, Carvalho RM, Tjäderhane L, Reis AF, Hebling J, Mazzoni A, Breschi L, Pashley DH, In vivo preservation of the hybrid layer by chlorhexidine. J Dent Res J, 2007. 86: p. 529–533.

- Barbosa-Martins, L.F., et al., Biomimetic Mineralizing Agents Recover the Micro Tensile Bond Strength of Demineralized Dentin. Materials (Basel), 2018. 11(9). [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Martins, L.F., et al., Enhancing bond strength on demineralized dentin by pre-treatment with selective remineralising agents. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, 2018. 81: p. 214-221. [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.-W., Y. Ma, and H.; Cölfen, Biomimetic mineralization. J. Mater. Chem., 2007. 17(5): p. 415-449.

- Cao, C.Y., et al., Methods for biomimetic remineralization of human dentine: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci, 2015. 16(3): p. 4615-27. [CrossRef]

- Osorio, R., C.I., Medina-Castillo AL, et al., Zinc-modified nanopolymers improve the quality of resin-dentin bonded interfaces. Clin Oral Invest. , 2016. 20: p. 2411–2420.

- Abuna, G., et al., Bonding performance of experimental bioactive/biomimetic self-etch adhesives doped with calcium-phosphate fillers and biomimetic analogs of phosphoproteins. J Dent, 2016. 52: p. 79-86. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., et al., Effect of Remineralized Collagen on Dentin Bond Strength through Calcium Phosphate Ion Clusters or Metastable Calcium Phosphate Solution. Nanomaterials (Basel), 2020. 10(11). [CrossRef]

- Chen, R., et al., Biomimetic remineralization of artificial caries dentin lesion using Ca/P-PILP. Dent Mater, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, K.M., et al., Impact of biomineralization on resin/biomineralized dentin bond longevity in a minimally invasive approach: An "in vitro" 18-month follow-up. Dent Mater, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Poggio, C., et al., Analysis of dentin/enamel remineralization by a CPP-ACP paste: AFM and SEM study. Scanning, 2013. 35(6): p. 366-74. [CrossRef]

- Padovano, J.D., et al., DMP1-derived peptides promote remineralization of human dentin. J Dent Res, 2015. 94(4): p. 608-14. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.S., A.S.E.; Carvalho, E.M.; Carvalho, C.N.; Carvalho, R.M.; Manso, A.P.;, A niobophosphate bioactive glass suspension for rewetting dentin: Effect on antibacterial activity, pH and resin-dentin bonding durability. Journal: International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2018. 84: p. 178-183. [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, A.F.M., et al., Influence of silver diamine fluoride on the adhesive properties of interface resin-eroded dentin. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 2021. 106. [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Jimenez, C.A.-L., P.; Benavides-Reyes, C.; Gonzalez-Lopez, S.; Rodriguez-Navarro, A.B.; Bolaños-Carmona, M.V.;, Physicochemical and Mechanical Effects of Commercial Silver Diamine Fluoride (SDF) Agents on Demineralized Dentin. J Adhes Dent 2021. 23,(6): p. 557-567.

- Dávila-Sánchez, A.G., M.F.; Bermudez, J.P.; Méndez-Bauer, M.L.; Hilgemberg, B.; Sauro, S.; Loguercio, A.D.; Arrais, C.A.G.;, Influence of flavonoids on long-term bonding stability on caries-affected dentin. Dent Mater, 2020. 36(9): p. 1151-1160.

- Gungormus, M. and F. Tulumbaci, Peptide-assisted pre-bonding remineralization of dentin to improve bonding. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, 2021. 113: p. 104119. [CrossRef]

- Krithi, B.V., S.; Mahalaxmi, S.;, Microshear bond strength of composite resin to demineralized dentin after remineralization with sodium fluoride, CPP-ACP and NovaMin containing dentifrices. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2020. 10( 2): p. 122-127. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.H., F.; Wang,S.; Li, M.; Lu, Y.; Pei, D.; Li, A., Bonding Performance of Universal Adhesives Applied to Nano-Hydroxyapatite Desensitized Dentin Using Etch-and-Rinse or Self-Etch Mode. Materials, 2021. 14: p. 4746.

- Paik, Y.K., J.H.; Yoo, K.H.; Yoon, S.Y.; Kim, Y.I.;, Dentin Biomodification with Flavonoids and Calcium Phosphate Ion Clusters to Improve Dentin Bonding Stability. Materials (Basel) -, 2022. 15.

- Pei, D.M., Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y.;, Influence of nano-hydroxyapatite containing desensitizing toothpastes on the sealing ability of dentinal tubules and bonding performance of self-etch adhesive. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, 2019. 91: p. 38-44.

- Pulidindi, H., M.J.B.R.R.R.A.P.P.P., Effect of remineralizing agents on resin-dentin bond durability of adhesive restorations: An in vitro. J Int Oral Health, 2021. 13(470-7). [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, F.S.F.M., L.A.R.; Granja, M.C.P.; de Melo, B.O.; Monteiro-Neto, V.; Reis, A.; Cardenas, A.F.M.; Loguercio, A.D.;, Effect of Silver Diamine Fluoride on the Bonding Properties to Caries-affected Dentin. J Adhes Dent, 2020. 22: p. 161-172. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.C., Z.Y.; Yan, H.Y.; Huang, C.;, Effects of calcium-containing desensitizers on the bonding stability of an etch-and-rinse adhesive against long-term water storage and pH cycling. Dental Materials Journal 2018. 37( 1): p. 122-129.

- Zhang, L.S., H.L.; Yu, J.; Yang, H.Y.; Song, F.F.; Huang, C.;, Application of electrophoretic deposition to occlude dentinal tubules in vitro. Journal of Dentistry, 2018. 71: p. 43-48.

- Altinci, P., et al., Microtensile bond strength to phosphoric acid-etched dentin treated with NaF, KF and CaF 2. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 2018. 85: p. 337-343. [CrossRef]

- Atomura, J.I., G.; Nikaid, T.; Yamanaka, K.; Uo, M.; Tagami, J.;, Influence of FCP-COMPLEX on bond strength and the adhesive artificial caries-affected dentin interface. Dental Materials Journal 2018. 37( 5): p. 775-782.

- de Sousa, J.P., et al., The Self-Assembling Peptide P11-4 Prevents Collagen Proteolysis in Dentin. J Dent Res, 2019. 98(3): p. 347-354. [CrossRef]

- Priya, C.H.L.N., S.B.; Kumar, N.K.; Merwade, S.; Brigit, B.; Prabakaran, P.;, Evaluation of the bond strength of posterior composites to the dentin, treated with four different desensitizing agents - An In vitro study. Journal of the International Clinical Dental Research Organization 2020. 12(1): p. 38-41.

- Van Duker, M.H., J.; Chan, D.C.; Tagami, J.; Sadr, A.;, Effect of silver diamine fluoride and potassium iodide on bonding to demineralized dentin. Am J Dent 2019. 32( 3): p. 143-146.

- Zumstein, K., et al., The Effect of SnCl2/AmF Pretreatment on Short- and Long-Term Bond Strength to Eroded Dentin. Biomed Res Int, 2018. 2018: p. 3895356.

- Meng, Y., et al., Bonding Performance of Universal Adhesives Applied to Nano-Hydroxyapatite Desensitized Dentin Using Etch-and-Rinse or Self-Etch Mode. Materials (Basel), 2021. 14(16). [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, A.F.M.A., L.C.R.; Szesz, A.L.; de Jesus Tavarez, R.R.; Siqueira, F.S.F.; Reis, A.; Loguercio, A.D.;, Influence of Application of Dimethyl Sulfoxide on the Bonding Properties to Eroded Dentin. J Adhes Dent, 2021. 23(6): p. 589-598.

- Zhang, L., et al., Application of electrophoretic deposition to occlude dentinal tubules in vitro. J Dent, 2018. 71: p. 43-48. [CrossRef]

- Pulidindi, H.M., J.; Borugadda, R.; Ravi, R.; Angadala, P.; Penmatsa, P.;, Effect of remineralizing agents on resin-dentin bond durability of adhesive restorations: An in vitro study. Journal of International Oral Health 2021. 13: p. 470-477.

- Page JM, e.a., The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 2021. 371(71): p. 1-9.

- Zumstein, K.P., A.; Lussi, A.; Flury, S.;, The Effect of SnCl(2)/AmF Pretreatment on Short- and Long-Term Bond Strength to Eroded Dentin. Biomed Res Int 2018-. 2018: p. 3895356.

- Cipriani, A., H.J., Geddes JR, Salanti, G., Conceptual and technical challenges in network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med, 2013. 159: p. 130-7.

- Isolan CP, S.-O.R., Lima GS, Moraes RR., Bonding to Sound and Caries-Affected Dentin: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Adhes Dent, 2018. 20: p. 7-18.

- Marquezan, M., et al., Artificial methods of dentine caries induction: A hardness and morphological comparative study. Arch Oral Biol, 2009. 54(12): p. 1111-7. [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, M.C., et al., Histomorphologic characterization and bond strength evaluation of caries-affected dentin/resin interfaces: effects of long-term water exposure. Dent Mater, 2008. 24(6): p. 786-98. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, L., et al., Microtensile bond strength of total-etch and self-etching adhesives to caries-affected dentine. J Dent, 2003. 31(7): p. 469-77. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, G.S., Pereira, G.K.R. ,Susin,A.H., Aging Methods—An Evaluation of Their Influence on Bond Strength Eur J Dent, 2021. 15:: p. 448–453.

- Hardan, L., et al., Bond Strength of Universal Adhesives to Dentin: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Polymers (Basel), 2021. 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, A., C. Lechte, and P. Kanzow, Adhesion to eroded enamel and dentin: systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent Mater, 2021. 37(12): p. 1845-1853. [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.N., et al., Biomimetic remineralization of dentin. Dent Mater, 2014. 30(1): p. 77-96. [CrossRef]

- Dawasaz, A.A.T., R.A.; Mahmood, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Thirumulu Ponnuraj, K. , Remineralization of Dentinal Lesions Using Biomimetic Agents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomimetics, 2023. 8: p. 159.

- Haj-Ali, R., et al., Histomorphologic characterization of noncarious and caries-affected dentin/adhesive interfaces. J Prosthodont, 2006. 15(2): p. 82-8. [CrossRef]

- Joves GJ, I.G., Nakashima S, Sadr A, Nikaido T, Tagami, J., Mineral density, morphology and bond strength of natural versus artificial caries-affected dentin. Dent Mater J, 2013. 32: p. 138-43.

- Mourad Ouzzani, H.H., Zbys Fedorowicz, and Ahmed Elmagarmid., Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2016. 5: p. 210.

- Sheth VH, S.N., Jain R, Bhanushali N, Bhatnagar, V., Development and validation of a risk-of-bias tool for assessing in vitro studies conducted in dentistry: The QUIN. J Prosthet Dent., 2022. 22(S0022-3913): p. 00345-6.

- Nikolakopoulou, A., H.J., Papakonstantinou T, Chaimani A, Del Giovane, C., Egger, M., et al., CINeMA: An approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med, 2020. 17: p. e1003082. [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, T., N.A., Higgins JPT, Egger, M., Salanti, G. , CINeMA: Software for semiautomated assessment of the confidence in the results of network meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews., 2020. 16: p. e1080.

- Higgins JPT, T.J., Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3, in Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. , L.T. Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Editor. 2022, Cochrane.

- Jonas DE, W.T., Bangdiwala, S., et al., Appendix A, WinBUGS Code Used in Bayesian Mixed Treatment Comparisons Meta-Analysis., in Findings of Bayesian Mixed Treatment Comparison Meta-Analyses: Comparison and Exploration Using Real-World Trial Data and Simulation A.f.H.R.a.Q. (US), Editor. 2013: Rockville (MD).

- Doozandeh, M.F., M.; Mirmohammadi, M., The Simultaneous Effect of Extended Etching Time and Casein Phosphopeptide-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate containing Paste Application on Shear Bond Strength of Etch-and-rinse Adhesive to Caries-affected Dentin. J Contemp Dent Pract 2015. 16(10): p. 794-9. [CrossRef]

- Bergamin, A.C.B., E.C.; Amaral, F.L.; Turssi, C.P.; Basting, R.T.; Aguiar, F.H.; França, F.M., Influence of an arginine-containing toothpaste on bond strength of different adhesive systems to eroded dentin. Gen Dent, 2016. 64(1): p. 67-73.

- Ghani, S.K., M.H.; Jindal, M.K.; Chaudhary, S.; Manuja, N., Comparative Evaluation Of The Influence Of Pre-Treatment With Cpp-Acp And Novamin On Dentinal Shear Bond Strength With Composite- An In Vitro Study. Annals of Dental Specialty 2017. 5(4): p. 140-145.

- Komori, P.C.P., D.H.; Tjäderhane, L.; Breschi, L.; Mazzoni, A.; de Goes, M.F.; Wang, L.; Carrilho, M.R.;, Effect of 2% chlorhexidine digluconate on the bond strength to normal versus caries-affected dentin. Oper Dent 2009. 34( 2): p. 157-65.

- Leal, A.C., C.; Maia, E.; Monteiro-Neto, V.; Carmo, M.; Maciel, A.; Bauer, J, Airborne-particle abrasion with niobium phosphate bioactive glass on caries-affected dentin-effect on the microtensile bond strength. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, 2017. 31(22): p. 2410-2423.

- Luong, M.N., et al., In Vitro Study on the Effect of a New Bioactive Desensitizer on Dentin Tubule Sealing and Bonding. J Funct Biomater, 2020. 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Meraji, N., et al., Bonding to caries affected dentine. Dent Mater, 2018. 34(9): p. e236-e245. [CrossRef]

- Prasansuttiporn, T., et al., Effect of antioxidant/reducing agents on the initial and long-term bonding performance of a self-etch adhesive to caries-affected dentin with and without smear layer-deproteinizing. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 2020. 102. [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.M., N.; Inayat, N.; Qaiser, A.; Wajahat, M.; Khan, M.W., Shear Bond Strength Of Etch And Rinse Adhesives To Dentin- Comparison Of Bond Strength After Acid And Papacarie Pre-Treatment. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2022. 34(1): p. 45-48.

- Yilmaz, N.A., E. Ertas, and H. Orucoglu, Evaluation of Five Different Desensitizers: A Comparative Dentin Permeability and SEM Investigation In Vitro. Open Dent J, 2017. 11: p. 15-33. [CrossRef]

- Castellan, C.S., et al., Mechanical characterization of proanthocyanidin-dentin matrix interaction. Dent Mater, 2010. 26(10): p. 968-73. [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, K., et al., Fluorine analysis of human dentin surrounding resin composite after fluoride application by μ-PIGE/PIXE analysis. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms, 2011. 269(20): p. 2269-2273. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L., S.Y.; Pei, D.D.; Du, X.J.; Ouyang, X.B.; Huang, C., Effect of an 8.0 arginine and calcium carbonate in-office desensitizing paste on the microtensile bond strength of self-etching dental adhesives to human dentin. American Journal of Dentistry, 2012. 25(5): p. 281-286.

- de-Melo, M.A.G.D., C.; de-Moraes, M.D.; Santiago, S.L.; Rodrigues, L.K., Effect of chlorhexidine on the bond strength of a self-etch adhesive system to sound and demineralized dentin. Braz Oral Res, 2013. 27(3): p. 218-24.

- Carvalho, C., et al., Effect of green tea extract on bonding durability of an etch-and-rinse adhesive system to caries-affected dentin. J Appl Oral Sci, 2016. 24(3): p. 211-7. [CrossRef]

- Deari, S., et al., Influence of Different Pretreatments on the Microtensile Bond Strength to Eroded Dentin. J Adhes Dent, 2017. 19(2): p. 147-155. [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, M.C., et al., Role of Proteolytic Enzyme Inhibitors on Carious and Eroded Dentin Associated With a Universal Bonding System. Oper Dent, 2017. 42(6): p. E188-E196. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.V., et al., Effect of conditioning solutions containing ferric chloride on dentin bond strength and collagen degradation. Dent Mater, 2017. 33(10): p. 1093-1102. [CrossRef]

- Imiolczyk, S.M., et al., The Influence of Cold Atmospheric Plasma Irradiation on the Adhesive Bond Strength in Non-Demineralized and Demineralized Human Dentin: An In Vitro Study. The Open Dentistry Journal, 2018. 12(1): p. 960-968. [CrossRef]

- Stape, T.H.S., et al., The pursuit of resin-dentin bond durability: Simultaneous enhancement of collagen structure and polymer network formation in hybrid layers. Dent Mater, 2021. 37(7): p. 1083-1095. [CrossRef]

- Hartz, J.J., et al., Influence of pretreatments on microtensile bond strength to eroded dentin using a universal adhesive in self-etch mode. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 2022. 114. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.S., et al., Effects of silver diammine fluoride on microtensile bond strength of GIC to dentine. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 2016. 70: p. 196-203. [CrossRef]

- Moda, M.D., et al., Analysis of the bond interface between self-adhesive resin cement to eroded dentin in vitro. PLoS One, 2018. 13(11): p. e0208024.

- Choi, Y.J., et al., Effects of microsurface structure of bioactive nanoparticles on dentinal tubules as a dentin desensitizer. PLoS One, 2020. 15(8): p. e0237726. [CrossRef]

- Abdelshafi, M.A., et al., Bond strength of demineralized dentin after synthesized collagen/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite application. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, 2021. 121: p. 104590. [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, Y.M., Impact of graphene oxide and silver diamine fluoride in comparison to photodynamic therapy on bond integrity and microleakage scores of resin modified glass ionomer cement to demineralized dentin. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther, 2021. 33: p. 102163. [CrossRef]

- Khor, M.M., et al., SMART: Silver diamine fluoride reduces microtensile bond strength of glass ionomer cement to sound and artificial caries-affected dentin. Dent Mater J, 2022. 41(5): p. 698-704. [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, O.A., M.F. Burrow, and M.J. Tyas, Resin-dentine interfacial morphology following CPP-ACP treatment. J Dent, 2010. 38(2): p. 96-105.

- Liu, Y., et al., Differences between top-down and bottom-up approaches in mineralizing thick, partially demineralized collagen scaffolds. Acta Biomater, 2011. 7(4): p. 1742-51. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., et al., Glutaraldehyde-induced remineralization improves the mechanical properties and biostability of dentin collagen. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl, 2016. 67: p. 657-665. [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, T.R., A.; Nerushay, I.; Kling, S.; Hafezi, F.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Krejci, I., Effects of riboflavin, calcium-phosphate layer and adhesive system on stress-strain behavior of demineralized dentin. American Journal of Dentistry, 2017. 30(4): p. 179-184.

- Liang, K., et al., Poly (amido amine) and nano-calcium phosphate bonding agent to remineralize tooth dentin in cyclic artificial saliva/lactic acid. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl, 2017. 72: p. 7-17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Cranberry Juice Extract Rapidly Protects Demineralized Dentin against Digestion and Inhibits Its Gelatinolytic Activity. Materials (Basel), 2021. 14(13). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., et al., Cross-linked dry bonding: A new etch-and-rinse technique. Dent Mater, 2016. 32(9): p. 1124-32. [CrossRef]

- Flury, S., A. Lussi, and A. Peutzfeldt, Long-Term Bond Strength of Two Benzalkonium Chloride-Modified Adhesive Systems to Eroded Dentin. Biomed Res Int, 2017. 2017: p. 1207208. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.S., P.; Yuca, E.; Tamerler, C., Engineered Peptide Repairs Defective Adhesive-Dentin Interface. Macromol Mater Eng, 2017. 302(5).

- Liang, K., et al., Poly (amido amine) dendrimer and dental adhesive with calcium phosphate nanoparticles remineralized dentin in lactic acid. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater, 2018. 106(6): p. 2414-2424. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.T., A.; Hosaka, K.; Kuno, Y.; Ikeda, M.; Nozaki, K.; Chiba, A.; Nakajima, M.; Tagami, J., Degree of conversion and dentin bond strength of light-cured multi-mode adhesives pretreated or mixed with sulfinate agents. Dental Materials Journal, 2021. 40(4): p. 877-884.

- Bridi, E.C., et al., Influence of storage time on bond strength of self-etching adhesive systems to artificially demineralized dentin after a papain gel chemical–mechanical agent application. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 2012. 38: p. 31-37. [CrossRef]

- Castellan, C.S., et al., Effect of dentin biomodification using naturally derived collagen cross-linkers: one-year bond strength study. Int J Dent, 2013. 2013: p. 918010. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, T.M.A., et al., Influence of natural and synthetic metalloproteinase inhibitors on bonding durability of an etch-and-rinse adhesive to dentin. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 2013. 47: p. 83-88. [CrossRef]

- Abu Nawareg, M., et al., Is chlorhexidine-methacrylate as effective as chlorhexidine digluconate in preserving resin dentin interfaces? J Dent, 2016. 45: p. 7-13. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S., C., Glutaraldehyde collagen cross-linking stabilizes resin-dentin interfaces and reduces bond degradation. European Journal of Oral Sciences 2017. 125(1): p. 63-71. [CrossRef]

- Prasansuttiporn, T., et al., Bonding Durability of a Self-etch Adhesive to Normal Versus Smear-layer Deproteinized Dentin: Effect of a Reducing Agent and Plant-extract Antioxidant. J Adhes Dent, 2017. 19(3): p. 253-258. [CrossRef]

- Ramezanian Nik, I., et al., Effect of Chlorhexidine and Ethanol on Microleakage of Composite Resin Restoration to Dentine. Chin J Dent Res, 2017. 20(3): p. 161-168. [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.A.G., et al., Effect of Metalloproteinase Inhibitors on Bond Strength of a Self-etching Adhesive on Erosively Demineralized Dentin. J Adhes Dent, 2019. 21(4): p. 337-344. [CrossRef]

- Fialho, M.P.N., et al., Effect of epigallocatechin-3- gallate solutions on bond durability at the adhesive interface in caries-affected dentin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, 2019. 91: p. 398-405. [CrossRef]

- Landmayer, K., et al., Could applying gels containing chlorhexidine, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, or proanthocyanidin to control tooth wear progression improve bond strength to eroded dentin? J Prosthet Dent, 2020. 124(6): p. 798 e1-798 e7.

- Costa, A.R.N., L.Z.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Tsuzuki, F.M.; Correr, A.B.; Correr-Sobrinho, L.; Puppin-Rontani, R.M., CHX Stabilizes the Resin-demineralized Dentin Interface. Braz Dent J 2021. 32(4): p. 106-115.

- Giacomini, M.C., et al., Performance of MDP-based system in eroded and carious dentin associated with proteolytic inhibitors: 18-Month exploratory study. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, 2021. 114: p. 104177. [CrossRef]

- Shioya, Y., et al., Sodium p-Toluenesulfinate Enhances the Bonding Durability of Universal Adhesives on Deproteinized Eroded Dentin. Polymers (Basel), 2021. 13(22). [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.C., Y.; Li, X.; Lei, Y.; Shu, C.; Luo, Q.; Chen, L.; Li, X., Reconstruction of a Demineralized Dentin Matrix via Rapid Deposition of CaF(2) Nanoparticles In Situ Promotes Dentin Bonding. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2021. 13(43): p. 51775-51789.

- Tekbas Atay, M., et al., Long-term effect of curcuminoid treatment on resin-to-dentin bond strength. Eur J Oral Sci, 2022. 130(1): p. e12837. [CrossRef]

- Lemos, M., et al., Evaluation of Novel Plant-derived Monomers-based Pretreatment on Bonding to Sound and Caries-affected Dentin. Oper Dent, 2022. 47(1): p. E12-E21. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L., Y.H.; Zhou, Y.S.; Chung, K.H., Influence of carbodiimide-ethanol solution surface treatment on dentin microtensile bond strength. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban, 2015. 47(5): p. 825-8.

- Wang, H., et al., Oriented and Ordered Biomimetic Remineralization of the Surface of Demineralized Dental Enamel Using HAP@ACP Nanoparticles Guided by Glycine. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: p. 40701. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.C., et al., [Effect of hydroxyapatite based agents on the bonding properties of universal adhesives]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi, 2022. 57(2): p. 173-181.

| Study/Year | RoB (score) | Study type | ACAD | BRP | Groups | N (teeth) | Mean (SD) | AT | OM Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-hour measurement | ||||||||||

| ER + C | Altinci et al. 2018 [31] | M(50) | Exp. | 32% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 9 | 35.27 (4.63)a | ER | µTBS |

| F | NaF + 6mM F | 34.7 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| NaF + 24mM F | 54.66 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| NaF+179mM F | 47.11 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| KF + 6mM F | 51.8 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| KF + 24mM F | 48.56 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| KF + 179mM F | 47.58 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| CaF2 + 6mM F | 36.34 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| CaF2+24mM F | 39.49 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| CaF2+179mM F | 48.47 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Excite F | 48.84 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Barbosa-Martins et al. (A) 2018[8] | M(54) | Exp. | 6% CMC | Control | Control | 6 | 26.38 (8.64) | ER | µTBS | |

| F | NaF | 33.43 (10.41) | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 45.25 (8.82) | ||||||||

| Pept. | P11-4 | 46.42 (12.03) | ||||||||

| Barbosa-Martins et al. (B) 2018[7] | M(54) | Quasi-Exp. | 6% CMC | Control | Control | 6 | 21.96 (5.92) | ER | µTBS | |

| F | NaF | 33.43 (10.42) | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 45.25 (8.83) | ||||||||

| Pept. | P11-4 | 46.42 (12.03) | ||||||||

| Bauer et al. 2018[18] | M(50) | Exp. | 35% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 13 | 17 (4.1) | ER | SBS | |

| CaP | 5% NbG | 17.9 (5) | ||||||||

| 10%NbG | 15.8 (6.4) | |||||||||

| 20%NbG | 16.6 (4.4) | |||||||||

| 40%NbG | 15.8 (4.1) | |||||||||

| Cardenas et al. 2021[19] | M(63) | Exp. | pH cycling | Control | Control | 5 | 33.74 (3.6) | Univ. | µTBS | |

| F | SDF 12% | 38.03 (3.5) | ||||||||

| SDF 38% | 39.68 (2.7) | |||||||||

| SDF 38% without KI | 39.38 (2.5) | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 34.9 (3.3) | ||||||||

| F | SDF 12% | 42.45 (2.9) | ||||||||

| SDF 38% | 40.47 (4.2) | |||||||||

| SDF 38% without KI | 41.3 (2.5) | |||||||||

| Chen et al. 2020[14] | M(54) | Quasi-Exp. | pH cycling | Control | Control | 4 | 13.8 (3.35) a | Univ. | µTBS | |

| CaP | Ca/P-PILP | 23.8 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Pept. | PAA-PASP | 14 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| CaP | Ca/P | 11.9 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Cifuentes-Jimenez et al. 2021[20] | M(50) | Exp. | pH cycling | Control | Control | 5 | 31.4 (4.63) a | ER | µTBS | |

| F | Cariestop | 15.1 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| RivaStar1 | 10.1 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| RivaStar2 | 7.5 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Saforide | 23.2 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Gungormus et al. 2021[22] | M(50) | Exp. | 37% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 10 | 15.38 (1.3) | ER | SBS | |

| CaP | NPR 60min | 15.85 (1.44) | ||||||||

| Pept. | PR 10 min | 20.81 (1.74) | ||||||||

| PR 30 min | 20 (1.68) | |||||||||

| PR 60 min | 16.21 (1.1) | |||||||||

| Krithi et al. 2020[23] | M(54) | Exp. | 0.5% citric acid | Control | Control | 15 | 11.83 (0.43) | ER | µSBS | |

| F | NaF | 11.56 (0.15) | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 12.12 (0.57) | ||||||||

| Novamin | 11.66 (0.28) | |||||||||

| Ca | Non-Fidated | 11.94 (0.27) | ||||||||

| Meng et al. 2021[24] | M(50) | Exp. | 1% citric acid | Control | Control | 8 | 46.8b (4.63) a | Univ. | µTBS | |

| Hap | Biorepair | 50.72 b (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Dontodent Sensitive | 50.71 b (4.63) a | |||||||||

| nHAp | 51.24 b (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 50.41 b (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Hap | Biorepair | 53.38 b (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Dontodent Sensitive | 54.5 b (4.63) a | |||||||||

| nHAp | 55.63 b (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 46.85 b (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Hap | Biorepair | 50.77 b (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Dontodent Sensitive | 53.82 b (4.63) a | |||||||||

| nHAp | 55 b (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Pulidindi et al. 2021[40] | M(63) | Exp. | 37% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 15 | 48.84 (4.63) a | ER | µTBS | |

| Pept. | P11-4 | 38.66 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 34.07 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Control | Control | 22.63 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Pept. | P11-4 | 25.37 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 23.62 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Van Duker et al. 2019[35] | H(46) | Quasi-Exp. | 7 days in ADS | Control | Control | 10 | 23.5 (10.7) | Univ. | µTBS | |

| F | SDF 38% | 19.8 (8.4) | ||||||||

| SDF 38% without KI | 7.9 (6.6) | |||||||||

| Yang et al. 2018[29] | M(50) | Exp. | 1% citric acid | Control | Control | 10 | 46.5 b (4.63)a | ER | µTBS | |

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 42.6 b (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Novamin | 43.3 b (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 22.3 b (4.63) a | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 41.2 b (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Novamin | 31.4 b (4.63) a | |||||||||

| ER + B | Barbosa-Martins et al. (B) 2018 | M(54) | Quasi-Exp. | BHI+ S.Mutans | Control | Control | 6 | 22.89 (2.68) | ER | µTBS |

| F | NaF | 26.94 (6.7) | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 47.95 (6.69) | ||||||||

| Pept. | P11-4 | 42.07 (7.83) | ||||||||

| Dávila-Sánchez et al. 2020[21] | M(54) | Exp. | Cariogenic+ S. Mutans | Control | Control | 7 | 14.42 (4.43) | Univ. | µTBS | |

| Fls. | QUE | 24.58 (4.9) | ||||||||

| HES | 18.41 (5.3) | |||||||||

| RUT | 26 (5.51) | |||||||||

| NAR | 24.64 (3.7) | |||||||||

| PRO | 20.66 (3.92) | |||||||||

| de Sousa et al. 2019[33] | M(50) | Quasi-Exp. | Cariogenic+ S. Mutans | Control | Control | 8 | 21.07 (3.24) | ER | µTBS | |

| Pept. | P11-4 | 42.07 (7.83) | ||||||||

| Moreira et al. 2021[15] | M(54) | Exp. | Cariogenic+ S. Mutans | Control | Control | 8 | 25.4 (2.45) | ER | µTBS | |

| F | NaF | 25.47 (4.8) | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 41.79 (5.85) | ||||||||

| Pept. | P11-4 | 40.12 (3.62) | ||||||||

| Siqueira et al. 2020[28] | M(63) | Exp. | Cariogenic+ S. Mutans | Control | Control | 5 | 16.81 (3.5) | Univ. | µTBS | |

| F | SDF 12% | 21.11 (4.1) | ||||||||

| SDF 38% | 24.36 (3.4) | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 19.89 (2.4) | ||||||||

| F | SDF 12% | 24.47 (3.4) | ||||||||

| SDF 38% | 26.32 (2) | |||||||||

| SE + C | Atomura et al. 2018[32] | H(46) | Quasi-Exp. | 7 days in ADS | Control | Control | unknown | 48.3 (13) | SE | µTBS |

| F | NaF | 47.7 (8.6) | ||||||||

| FCP complex | 43.9 (14.3) | |||||||||

| Barbosa-Martins et al. (A) 2018 | M(54) | Exp. | 48h 6% CMC | Control | Control | 6 | 25.38 (8.58) | SE | µTBS | |

| F | NaF | 35.59 (9.18) | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 48.11 (11.71) | ||||||||

| Pept. | P11-4 | 25.7 (8.95) | ||||||||

| Cardenas et al. 2021 | M(63) | Exp. | pH cycling | Control | Control | 5 | 33.74 (3.6) | Univ. | µTBS | |

| F | SDF 12% | 39.53 (4.2) | ||||||||

| SDF 38% | 41.31 (2) | |||||||||

| SDF 38% without KI | 40.55 (2.9) | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 36.56 (4.1) | ||||||||

| F | SDF 12% | 39.98 (1.7) | ||||||||

| SDF 38% | 41.08 (3) | |||||||||

| SDF 38% without KI | 41.57 (2.4) | |||||||||

| Chen et al. 2020 | M(54) | Quasi-Exp. | pH cycling | Control | Control | 4 | 13.8 (3.35) a | Univ. | µTBS | |

| CaP | Ca/P-PILP | 23.8 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Pept. | PAA-PASP | 14 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| CaP | Ca/P | 11.9 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Control | Control | 9.2 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| CaP | Ca/P-PILP | 15.1 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Pept. | PAA-PASP | 9.3 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| CaP | Ca/P | 9.8 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Cifuentes-Jimenez et al. 2021 | M(50) | Exp. | pH cycling | Control | Control | 5 | 31.4 (3.35) a | SE | µTBS | |

| F | Cariestop | 9.6 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Saforide | 8.03 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| Gungormus et al. 2021 | M(50) | Exp. | 37% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 10 | 15.38 (1.3) | SE | SBS | |

| CaP | NPR 60min | 15.49 (1.17) | ||||||||

| Pept. | PR 10 min | 18.93 (0.99) | ||||||||

| PR 30 min | 19.62 (0.9) | |||||||||

| PR 60 min | 21.73 (1.57) | |||||||||

| Krithi et al. 2020 | M(54) | Exp. | 0.5% citric acid | Control | Control | 15 | 11.83 (0.43) | SE | µSBS | |

| F | NaF | 12.4 (0.18) | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 11.97 (0.39) | ||||||||

| Novamin | 11.97 (0.17) | |||||||||

| Ca | Non-Fidated | 10.62 (0.11) | ||||||||

| Meng et al. 2021 | M(50) | Exp. | 1% citric acid | Control | Control | 8 | 46.8 b (3.35) a | Univ. | µTBS | |

| Hap | Biorepair | 47.62 b (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Dontodent Sensitive | 51.89 b (3.35) a | |||||||||

| nHAp | 51.89 b (3.35) a | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 56.3 b (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Hap | Biorepair | 51.62 b (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Dontodent Sensitive | 57.47 b (3.35) a | |||||||||

| nHAp | 58.39 b (3.35) a | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 56.8 b (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Hap | Biorepair | 52.25 b (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Dontodent Sensitive | 50.8 b (3.35) a | |||||||||

| nHAp | 56.1 b (3.35) a | |||||||||

| Paik et al. 2022[25] | M(50) | Exp. | 35% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 4 | 21.66 (3.35) a | Univ. | µTBS | |

| Fls. | ICT | 24.4 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| FIS | 26.81 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| SIB | 25.65 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| CPIC | 25.97 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| ICT+ C | 30.63 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| FIS+ C | 25.63 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| SIB+ C | 24.76 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| Pei et al. 2019[26] | M(50) | Exp. | 1% citric acid | Control | Control | 4 | 43.61 (3.35) a | SE | µTBS | |

| Hap | Biorepair | 33.16 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Dontodent Sensit. | 35.41 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| nHAp | 46.92 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 47.47 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Hap | Biorepair | 43.47 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Dontodent Sensit. | 42.3 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| nHAp | 41.24 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| Priya et al. 2020[34] | H(46) | Quasi-Exp. | 37% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 13 | 6.677 (1.254) | Univ. | SBS | |

| F | VivaSens | 3.332 (0.78) | ||||||||

| MS Coat F | 3.127 (0.478) | |||||||||

| HEMA | GLUMA Desensit. | 4.572 (0.718) | ||||||||

| Systemp | 9.697 (1.127) | |||||||||

| Zang et al. 2018[30] | M(50) | Exp. | 37% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 6 | 19.73 b (2.108) | Univ. | SBS | |

| SiO2 | Charged mesoporous | 20.57 b (2.244) | ||||||||

| Zumstein et al. 2018[42] | M(50) | Quasi-Exp. | pH cycling | Control | Control | 20 | 24.7 (8.1)c | SE | µTBS | |

| F | SnCl2/ AmF4 | 23.3 (8.2) c | ||||||||

| Control | Control | 23.73 (8) c | Univ. | |||||||

| F | SnCl2/ AmF4 | 21.39 (6.8) c | ||||||||

| SE + B | Siqueira et al. 2020 | M(63) | Exp. | Cariogenic+ S. Mutans | Control | Control | 5 | 16.81 (3.5) | Univ. | µTBS |

| F | SDF 12% | 20.02 (4.6) | ||||||||

| SDF 38% | 25.21 (3) | |||||||||

| Control | Control | 19.61 (3.3) | ||||||||

| F | SDF 12% | 23.82 (4.4) | ||||||||

| SDF 38% | 27.16 (3.6) | |||||||||

| TMC measurement | ||||||||||

| ER + C | Pulidindi et al. 2021 | M(63) | Exp. | 37% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 15 | 48.84 (4.63) a | ER | µTBS |

| Pept. | P11-4 | 25.37 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 23.62 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| ER + B | Dávila-Sánchez et al. 2020 | M(54) | Exp. | Cariogenic+ S. Mutans | Control | Control | 7 | 14.42 (4.43) | Univ. | µTBS |

| Fls. | QUE | 12.02 (5.21) | ||||||||

| HES | 15.73 (6.07) | |||||||||

| RUT | 21.08 (4.75) | |||||||||

| NAR | 22.12 (2.92) | |||||||||

| PRO | 17.2 (2.72) | |||||||||

| SE + C | Chen et al. 2020 | M(54) | Quasi-Exp. | pH cycling | Control | Control | 4 | 13.8 (3.35) a | Univ. | µTBS |

| CaP | Ca/P-PILP | 15.1 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Pept. | PAA-PASP | 9.3 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| CaP | Ca/P | 9.8 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| Paik et al. 2022 | M(50) | Exp. | 35% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 4 | 21.66 (3.35) a | Univ. | µTBS | |

| Fls. | ICT | 20.53 (3.35) a | ||||||||

| FIS | 19.4 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| SIB | 22.04 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| CPIC | 23.43 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| ICT+ C | 26.74 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| FIS+ C | 23.42 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| SIB+ C | 25.17 (3.35) a | |||||||||

| Storage in a fluid solution for 3-month measurement | ||||||||||

| ER + C | Bauer et al. 2018 | M(50) | Exp. | 35% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 13 | 17 (4.1) | ER | SBS |

| CaP | 5% NbG | 11.8 (3.7) | ||||||||

| 10%NbG | 13.9 (3.2) | |||||||||

| 20%NbG | 13.2 (2.7) | |||||||||

| 40%NbG | 14.7 (2.9) | |||||||||

| SE + C | Atomura et al. 2018 | H(46) | Quasi-Exp. | 7 days in ADS | Control | Control | unknown | 48.3 (13) | SE | µTBS |

| F | NaF | 42.6 (12.1) | ||||||||

| FCP complex | 47.4 (9.2) | |||||||||

| Storage in a fluid solution for 6-month measurement | ||||||||||

| ER + C | Altinci et al. 2018 | M(50) | Exp. | 32% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 9 | 35.27 (4.63) a | ER | µTBS |

| F | NaF + 6mM F | 50.31 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| NaF + 24mM F | 49.28 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| NaF+179mM F | 47.73 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| KF + 6mM F | 41.95 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| KF + 24mM F | 51.53 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| KF + 179mM F | 54.29 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| CaF2 + 6mM F | 52.25 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| CaF2+24mM F | 41.1 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| CaF2+179mM F | 40.85 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Excite F |

46.22 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| de Sousa et al. 2019 | M(50) | Quasi-Exp. | Cariogenic+ S. Mutans | Control | Control | 8 | 21.07 (3.24) | ER | µTBS | |

| Pept. | P11-4 | 31.98 (3.44) | ||||||||

| Moreira et al. 2021 | M(54) | Exp. | Cariogenic+ S. Mutans | Control | Control | 8 | 25.4 (2.45) | ER | µTBS | |

| F | NaF | 18.36 (5.5) | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 36.55 (4.27) | ||||||||

| Storage in a fluid solution for 12-month measurement | ||||||||||

| ER+C | Altinci et al. 2018 | M(50) | Exp. | 32% phosphoric acid | Control | Control | 9 | 35.27 (4.63) a | ER | µTBS |

| F | NaF + 6mM F | 51.63 (4.63) a | ||||||||

| NaF + 24mM F | 45.56 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| NaF+179mM F | 39.31 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| KF + 6mM F | 40.01 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| KF + 24mM F | 51.85 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| KF + 179mM F | 36.48 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| CaF2 + 6mM F | 33.06 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| CaF2+24mM F | 38.24 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| CaF2+179mM F | 0.88 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Excite F | 42.4 (4.63) a | |||||||||

| Yang et al. 2018 | M(50) | Exp. | 1% citric acid | Control | Control | 10 | 46.5 b (4.63) a | ER | µTBS | |

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 41.2 b (4.63) a | ||||||||

| Novamin | 31.4 b (4.63) a | |||||||||

| SE+C | Zumstein et al. 2018 | M(50) | Quasi-Exp. | pH cycling | Control | Control | 20 | 24.7 (8.1)c | SE | µTBS |

| F | SnCl2/ AmF4 | 16.3 (6.36)c | ||||||||

| Control | Control | 15.43 (6.53)c | Univ. | |||||||

| F | SnCl2/ AmF4 | 14.12 (7.12)c | ||||||||

| Storage in a fluid solution for 18-month measurement | ||||||||||

| ER+B | Moreira et al. 2021 | M(54) | Exp. | Cariogenic+ S. Mutans | Control | Control | 8 | 25.4 (2.45) | ER | µTBS |

| F | NaF | 7.81 (4.48) | ||||||||

| CaP | CPP-ACP | 26.01 (3.28) | ||||||||

| Pept. | P11-4 | 25.24 (3.98) | ||||||||

| a- Input SD Values; b- Information given by authors; c- Information from another meta-analysis. | ||||||||||

| Legend: B- Biological; C- Chemical; RoB- Risk of bias; ACAD- Artificial caries-affected dentin; BRP- Biomimetic remineralization procedure; SD- Standard deviation; AT- Adhesive technique; OM-Outcome measurement; ADS- Artificial demineralization solution; M- Medium; H- High; Exp.-Experimental; ER- Etch-and-rinse; SE- Self-etch; Univ.- Universal; F- Fluorine; Ca-Calcium; CaP- Calcium phosphate; Pept.- Peptide; FLs- Flavonoids; SiO2- Silica Hap- Hidroxiapatite; HEMA- 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate; TMC- Thermocycling; µTBS- microtensile bond strengh; SBS- shear bond strength; µSBS- microshear bond strength. | ||||||||||

| Plot of the NMA ER + chemical ACAD |

Plot of the NMA ER + biological ACAD |

Plot of the NMA SE + chemical ACAD |

|

|

|

|

| NMA | Ranks and probability of ranking best |

|---|---|

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).