1. Introduction

The immune response, or immunity, is the recognition of and protection against foreign invaders (

Maekawa et al. 2011, Király et al. 2013); therefore, a fundamental feature of the immune response is the ability to distinguish between self and non-self (

Coll et al. 2011, Alberts et al. 2015). The immune response is also classified into primary and secondary immune responses (

Janeway et al. 2001, Király et al. 2013). The primary immune response is the initial response to pathogen infection, followed by a secondary immune response to infection from the same pathogen (

Janeway et al. 2001, Király et al. 2013). Secondary immunity in animals is a type of cell-based immune memory, a highly effective adaptive immune response (

Janeway et al. 2001, Király et al. 2013). For example, when a host is first exposed to an antigen, its B cells produce antibodies and long-lived memory B and T cells, which recognize the antigen in subsequent infections, including secondary infections, triggering an immune response to the infection that is much more effective and rapid than the primary immune response (

Janeway et al. 2001, Fu and Dong 2013). Plants, however, do not have these specialized immune cells like animals, but maintain immune memory through systemic acquired resistance (SAR) for the suppression of secondary infections (

Fu and Dong 2013, Király et al. 2013).

SAR is a long-term and broad-spectrum resistance occurrence throughout the whole plant after local pathogen infection (

Muthamilarasan and Prasad 2013, Seyfferth and Tsuda 2014, Shine et al. 2019). During SAR, a signal is rapidly generated at the primary site of local infection and transmitted throughout the plant; a common signal molecule is salicylic acid (SA) (

Mishina and Zeier 2007, Seyfferth and Tsuda 2014). In addition to SA, the hormone jasmonic acid (JA)/ethylene (ET) and its primary and secondary metabolites; nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species (ROS) have also been reported as SAR triggers (

Zhang et al. 2010, Li et al. 2019, Shine et al. 2019). SA, JA and ROS are known to transmit signaling from the local infection area to distant uninfected areas through the apoplast (

Felle et al. 2005, Shine et al. 2019, Farvardin et al. 2020, Kachroo et al. 2020, Li et al. 2021).

To determine the presence or absence of SA or JA -induced immune responses in red algae, the presence of hormone synthesizing genes, the detection of endogenous hormones or a hormone-induced immune response to exogenous hormones should be observed (

Seyfferth and Tsuda 2014, Radwan et al. 2007). However, in red algae, the hormones SA and JA are either not detected (

Collén et al. 2006) or only observed in some species (

Krupina and Dathe 1991). The genes involved SA and JA synthesis have not been identified in red algae (

Collén et al. 2006, Egan et al. 2014, de Oliveira et al. 2017), and while exogenous SA is involved in growth in some red algae, it does not induce an immune response (

Wang et al. 2013). However, red algae do have defense responses against diverse pathogens (

Pereira and Vasconcelos 2014, Luo et al. 2015, Tang et al. 2019, Im et al. 2019). Research on innate immunity of red algae has been conducted, but it is limited to the economically important seaweed species,

Pyropia yezoensis (

Tang et al. 2019). In several multicellular red algae, some receptors and genes involved in innate immunity have been partially characterized, and defense responses such as oxidative bursts (OB) and hypersensitivity reactions (HR) have been reported (

Weinberger et al. 2007, Gachon et al. 2010, Egan et al. 2014, Luo et al. 2015, de Oliveira et al. 2017, Tang et al. 2019, Im et al. 2019, Wen et al. 2023).

Both OB and HR responses are triggered by ROS, which can also the transmitted through the plant (

Apel and Hirt 2004, Fujita et al. 2006). One of the main sources of ROS is the conversion of dioxygen (O

2) to superoxide anion (O

2-), catalyzed by NADPH oxidase, with hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) being produced in the subsequent reaction (

Lightfoot et al. 2008, Marino et al. 2012, Huang et al. 2019, Mandal et al. 2022). NADPH oxidase and ferric reductase are homologs with canonical domains but are functionally different, with iron reductase catalyzing the electron transfer from cytosolic NADPH to extracellular metal ions and NADPH oxidase catalyzing the electron transfer from cytosolic NADPH to extracellular oxygen (

Zhang et al. 2013). However, NADPH oxidase is distinguished from ferric reductase by three conserved amino acids ranging from transmembrane domain 3 (TM3) to TM4 (

Zhang et al. 2013). Respiratory burst oxidase homologues (RBOHs) belong to NADPH oxidase gene super-families and

rboh genes have been also reported in red algae (

Inupakutika et al. 2016, Luo et al. 2015, Im et al. 2019, Gui et al. 2022, Shim et al. 2022, Moon et al. 2022, Hong et al. 2024b). However, previously reported red algal RBOHs did not mention the presence of conserved sequences and only revealed functional domains that are difficult to distinguish from ferric reductases (

Inupakutika et al. 2016, Luo et al. 2015, Im et al. 2019, Gui et al. 2022, Shim et al. 2022, Moon et al. 2022, Hong et al. 2024b).

The genus

Olpidiopsis is one of the most common pathogens in red algae (

Wen et al. 2023). The red alga

Dasysiphonia japonica (formerly known as

Heterosiphonia japonica), an invasive species introduced worldwide from the Asian Pacific (

Choi et al. 2002, Sjøtun et al. 2008, Savoie and Saunders 2013), is also infected with

Olpidiopsis spp. (

Klochkova et al. 2017). In this study, we aimed to investigate the immune response of

D. japonica to two species of

Olpidiopsis (Supplementary Video S1, S2).

D. japonica can co-exist with

O. heterosiphoniae infection, as opposed the case of

Pyropia in which this infection leads to lethality, and infection of another

Olpidiopsis species (i.e.,

Olpidiopsis dasysiphoniae) which leads lethality in

Dasysiphonia japonica.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Culture

An

Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae infected

Heterosiphonia pulchra plant was collected from Wando, Korea on 17 May 2006. Dual host-parasite cultures were established using

Dasysiphonia japonica, collected from Wando, Korea in September 2004, Wando, Korea (

Klochkova et al. 2017).

Olpidiopsis dasysiphoniae infecting

D. japonica was collected from Muroran, Japan on 17 August 2018 (

Wen et al. 2025). To maintain a high infection rate, we transferred the

Olpidiopsis dasysiphoniae to a

Dasysiphonia japonica collected in September 2004 from Wando, Korea. The samples were cultured in IMR medium and renewed every three weeks. The cultures were maintained in a chamber at 15℃ and 16:8 h light: dark cycle (15 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1).

The infection experiment was performed as follows: After 4-5 days of infection, the incubated medium was filtered through a 20 µm nylon net filter (NY20, Merck, Germany) to isolate the zoospores released from infected plants. The medium containing zoospores was incubated with 1 cm indeterminate branches of D. japonica. The infection rate was determined by the number of infected cells in each of the six plants and average.

2.2. Microscopy Observations and Histological Staining

Samples were checked regularly using a microscope (BX50, Olympus, Japan) and recorded on a digital camera (DP72, Olympus) using the CellSens program (Olympus). The production of total reactive oxygen species (ROS) in real time was detected using 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and was performed as in

Moon et al. (

2022). Accumulation of hydrogen peroxides over time (every 12hours) was performed by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining and performed as in Strittmatter et al. (2016).

2.3. NADPH-Oxidases and Calcium Influx Inhibition Experiment

Diphenylene iodonium (DPI) was used to block the activity of NADPH-oxidases (

Foreman et al. 2003) and caffeine was used to block calcium influx through caffeine-sensitive Ca

2+ channels (

Länge et al. 1996). Both DPI and caffeine were pretreated to the

D. japonica filament for 4 hours before infection.

2.4. Identification of NADPH-Oxidase from Dasysiphonia japonica

The known NADPH-oxidases of red algae (

Thapa et al. 2020, Gui et al. 2022, Moon et al. 2022, Shim et al. 2022) were blasted in transcriptome of

D. japonica, and a phylogenetic tree of NADPH-oxidase was constructed to identify the NADPH-oxidases of

D. japonica (Fig. S1). Protein domains were analyzed by Interproscan in Geneious Prime. The identification of conserved sites in protein domain followed a previous study (

Zhang et al. 2013).

2.5. Housekeeping Gene Testing and Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from infected Dasysiphonia japonica frozen samples ground in liquid nitrogen using a Qiagen RNeasy plant mini kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Prior to cDNA synthesis, all RNA samples were treated in DNase I using the Qiagen on-column DNase kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The integrity of the RNA was tested by agarose gel electrophoresis. The synthesis of cDNAs, from each sample, was obtained using the AccuScript High Fidelity 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Potential housekeeping genes (HKG) for quantitative PCR were selected from transcriptome data of Dasysiphonia japonica. Six genes were selected: alpha-tubulin (A-tubulin), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), translation elongation factor Tu (EF-TU), actin, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1C (UBI) and alpha-tubulin (A-tubulin) showed the most stably expressed Ct values at different stages of infection (Fig. S2). Primers for selected genes were designed considering melting temperature and products size using the Geneious Prime and showed in the Table S1. Real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in a real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad CFX96; Bio-Rad Laboratories). cDNA samples were amplified in triplicate from the same RNA preparation. The final reaction volume was 20 μl and included 5 μl of diluted cDNA, 10 μl of iQ SYBR Green supermix and 200 nM of each primer. The reaction protocol was first set at 95°C for 2 min and then 50 cycles of 95°C for 3 s and 60°C for 30 s. The expression of each HKG was determined from the cycle of threshold value (Ct value), which corresponds to the number of cycles required for PCR amplification to reach threshold. The selected HKGs were tested for expression stability during various infection processes, and the genes with the smallest standard deviation of Ct values were selected to determine the relative expression levels for other genes. Relative expression levels were then calculated against the housekeeping gene as a calibrator using the delta–delta Ct method.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Features of Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae Infection on Dasysiphonia japonica

To investigate the degree of infection after exposure to O. heterosiphoniae zoospores, we measured infection rates at 2-day intervals, the minimum time for O. heterosiphoniae sporangia to mature (Fig. 1). An infected host cells was noted when intracellular sporangia were observed (Fig. 1A). After 4 days of infection, several mature sporangia were produced, and zoospores were released (Fig. 1B). On 6 (Fig. 1C) and 8-days (Fig. 1D) after infection, mostly empty sporangia were seen, and some newly produced sporangia were observed as secondary infections progressed. The number of infected cells of Dasysiphonia japonica increased up to day 4 and then decreased to less than 3% from day 6 onwards (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Infection of Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae on Dasysiphonia japonica over time. (A) 2-days after infection. Sporangia of O. heterosiphoniae are seen developing inside apical cells of lateral branch (arrowheads and inset). (B) 4-days after infection, in addition to apical cells, other cells in monosiphonous branches also showed developing sporangia (arrowheads). (C) 6-days after infection with O. heterosiphoniae, most of the sporangia are mature, releasing zoospores and leaving empty sporangia (blue arrowheads), while some newly infected cells with developing sporangia are seen (black arrowheads). (D) 8-days after infection, empty sporangia (blue arrowhead) were observed in infected plant. (E) Changes in infection rate of O. heterosiphoniae on D. japonica over time. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). Scale bars represent: A-D, 100 μm.

Figure 1.

Infection of Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae on Dasysiphonia japonica over time. (A) 2-days after infection. Sporangia of O. heterosiphoniae are seen developing inside apical cells of lateral branch (arrowheads and inset). (B) 4-days after infection, in addition to apical cells, other cells in monosiphonous branches also showed developing sporangia (arrowheads). (C) 6-days after infection with O. heterosiphoniae, most of the sporangia are mature, releasing zoospores and leaving empty sporangia (blue arrowheads), while some newly infected cells with developing sporangia are seen (black arrowheads). (D) 8-days after infection, empty sporangia (blue arrowhead) were observed in infected plant. (E) Changes in infection rate of O. heterosiphoniae on D. japonica over time. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). Scale bars represent: A-D, 100 μm.

3.2. Comparison of Infection Symptoms of Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae and O. dasysiphoniae Infection in D. japonica

With O. heterosiphoniae, cell death was rarely observed around infected cells (Fig. 2A-B) even to a month after infection (Fig. 2C), plus number of infected cells remained low (see section above). However, during infection with O. dasysiphoniae, cell death of infected cells and adjacent cells was observed from the beginning of infection (Fig. 2D), and in many cases, cell death of multiple cells neighboring infected cells was observed (Fig. 2E). One month after the infection, the whole plant was almost dead (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Symptoms of infection with Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae and O. dasysiphoniae on Dasysiphonia japonica. (A-C) O. heterosiphoniae infection (A) Sporangium (arrow) in polysiphonous axial cell of host. (B) 4-days after infection. Arrow indicates infected cells (C) One month after infection. Arrow indicates infected cell. (D-F) O. dasysiphoniae infection. (D) Sporangium in polysiphonous axial cell of host. Arrow indicates infected cell. (E) 4-days after infection. Arrows indicates infected cells; arrowheads indicate adjacent dead cells. (F) One month after infection, most tissue is dead. Scale bars represent: A, D, 100 μm; B-C, E-F, 200 μm. .

Figure 2.

Symptoms of infection with Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae and O. dasysiphoniae on Dasysiphonia japonica. (A-C) O. heterosiphoniae infection (A) Sporangium (arrow) in polysiphonous axial cell of host. (B) 4-days after infection. Arrow indicates infected cells (C) One month after infection. Arrow indicates infected cell. (D-F) O. dasysiphoniae infection. (D) Sporangium in polysiphonous axial cell of host. Arrow indicates infected cell. (E) 4-days after infection. Arrows indicates infected cells; arrowheads indicate adjacent dead cells. (F) One month after infection, most tissue is dead. Scale bars represent: A, D, 100 μm; B-C, E-F, 200 μm. .

3.3. ROS Signaling in D. japonica After O. heterosiphoniae and O. dasysiphoniae Infection

When ROS staining was performed for Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae and Olpidiopsis dasysiphoniae there was a difference in ROS staining and a difference in infected cells when treated with ROS inhibitors. DCFH-DA staining of Dasysiphonia japonica was not detected with pre-infection (Fig. 3A) but detected around the membrane of infected host cells (Fig. 3, arrowheads), and developing pathogen, on day 2 (Fig. 3B), persisted to day 4 (Fig. 3C), and disappeared on day 8 post-infection (Fig. 3D), when most pathogen zoosporangia were empty. During infection with Olpidiopsis dasysiphoniae, there was no staining around the infected host cell membrane on days 2-4 but only in the developing pathogen (Fig. 3F-G). A large amount of ROS staining was observed on day 8 (Fig. 3H).

Figure 3.

DCFH-DA staining of Dasysiphonia japonica after Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae and O. dasysiphoniae infection (A-D) O. heterosiphoniae infection. (A) 0-day, pre-infection. (B) 2-day. (C) 4-day. (D) 8-day. (E-H) O. dasysiphoniae infection. (E) 0-day, pre-infection. (F) 2-day. (G) 4-day. (H) 8-day. Arrowhead indicates Olpidiopsis developing in cell. Scale bars represent: A-F, 50 μm. (I) Level of infections after ROS (DPI) and calcium channel (caffeine) inhibitors treatment on O. heterosiphoniae infection. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (one-way ANOVA vs. control, C, n = 6). (J) Level of infection after ROS and calcium inhibitors treatment in O. dasysiphoniae infection. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (one-way ANOVA vs. control, n = 3). ** p < 0.01, ns, non- significant.

Figure 3.

DCFH-DA staining of Dasysiphonia japonica after Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae and O. dasysiphoniae infection (A-D) O. heterosiphoniae infection. (A) 0-day, pre-infection. (B) 2-day. (C) 4-day. (D) 8-day. (E-H) O. dasysiphoniae infection. (E) 0-day, pre-infection. (F) 2-day. (G) 4-day. (H) 8-day. Arrowhead indicates Olpidiopsis developing in cell. Scale bars represent: A-F, 50 μm. (I) Level of infections after ROS (DPI) and calcium channel (caffeine) inhibitors treatment on O. heterosiphoniae infection. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (one-way ANOVA vs. control, C, n = 6). (J) Level of infection after ROS and calcium inhibitors treatment in O. dasysiphoniae infection. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (one-way ANOVA vs. control, n = 3). ** p < 0.01, ns, non- significant.

Diphenylene iodonium (DPI) pretreatment of host plants increased O. heterosiphoniae infection rates compared to the control, but caffeine pretreatment showed no significant difference from controls (Fig. 3I). In Olpidiopsis dasysiphoniae infections, DPI and caffeine pretreatment of host plants did not produce any significant difference in infection rates compared to the control (Fig. 3J).

In DAB staining, in O. heterosiphoniae infection, staining was detected within the infected host cell on day 2 of infection (Fig. 4B, 7I), became more intense on day 4 (Fig. 4C, 4J-K), and was detected at both ends of the host cell on day 8 of infection (Fig. 4D, 7L), when most sporangia were empty. In Olpidiopsis sp. infections, there was no significant difference in infected cells on days 2-4 (Fig. 4E-F, 7M), and by day 8, large amounts of H2O2 were stained in intracellular compartments adjacent to the host cell (Fig. 4N-O).

Figure 4.

DAB staining of Dasysiphonia japonica after Olpidiopsis spp. infection. (A, H) Uninfected plant. (B-D, I-L) O. heterosiphoniae infection. (B, I) 2-day. (C, J, K) 4-day. (D, L) 8-day. (E-G, M-O) Olpidiopsis sp. infection. (E) 2-day. (F, M) 4-day. (G, N, O) 8-day. Scale bars represent: A-G, 200 μm; H-O, 20 μm.

Figure 4.

DAB staining of Dasysiphonia japonica after Olpidiopsis spp. infection. (A, H) Uninfected plant. (B-D, I-L) O. heterosiphoniae infection. (B, I) 2-day. (C, J, K) 4-day. (D, L) 8-day. (E-G, M-O) Olpidiopsis sp. infection. (E) 2-day. (F, M) 4-day. (G, N, O) 8-day. Scale bars represent: A-G, 200 μm; H-O, 20 μm.

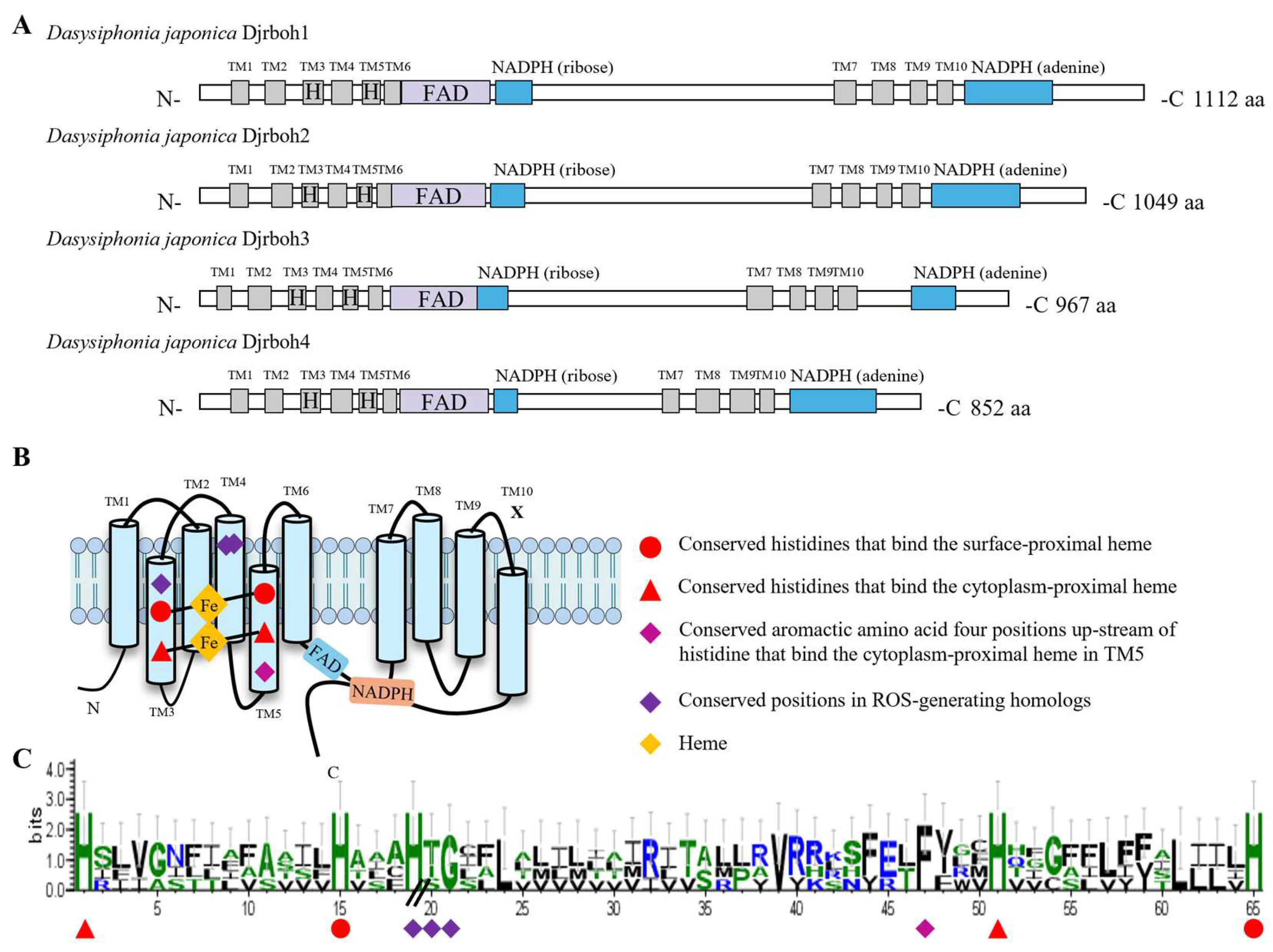

3.4. NADPH-Oxidase Homologues and Expression Levels O. heterosiphoniae and O. dasysiphoniae Infection

Four NADPH-oxidase (Djrboh1-4) homologs were found in our transcriptome dataset (Fig. 5). Djrbohs were shown to have not only conserved sequences for the ferric reductase domain (FRD) superfamily (Fig. 5A), but also NADPH-oxidase-specific conserved sequences (i.e., conserved positions in ROS-generating homologs) that distinguish it from ferric reductases (Fig. 5B). The conserved positions in the ROS-generating homologs of D. japonica consist of a heme-binding histidine in transmembrane domain 3 (TM3) and a conserved threonine or serine in transmembrane domain 4 (TM4), and although not specific to NADPH-oxidase homologs, the glycine sequence is conserved in dipeptide form with the threonine or serine in transmembrane domain 4 (TM4). The above analysis provides strong evidence that Djrboh1-4 is a protein that reduces oxygen rather than iron (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Structure of NADPH-oxidases in Dasysiphonia japonica. (A) Functional domain of NADPH-oxidase (Djrboh1-4) in D. japonica. (B) A schematic representation of the conserved sequences located in the transmembrane. (C) Sequence conservation logos of Djrboh1-4. The height of the stacks indicates sequence conservation, and the width of the stacks is proportional to the fraction of amino acids, thus narrowed within gapped regions.

Figure 5.

Structure of NADPH-oxidases in Dasysiphonia japonica. (A) Functional domain of NADPH-oxidase (Djrboh1-4) in D. japonica. (B) A schematic representation of the conserved sequences located in the transmembrane. (C) Sequence conservation logos of Djrboh1-4. The height of the stacks indicates sequence conservation, and the width of the stacks is proportional to the fraction of amino acids, thus narrowed within gapped regions.

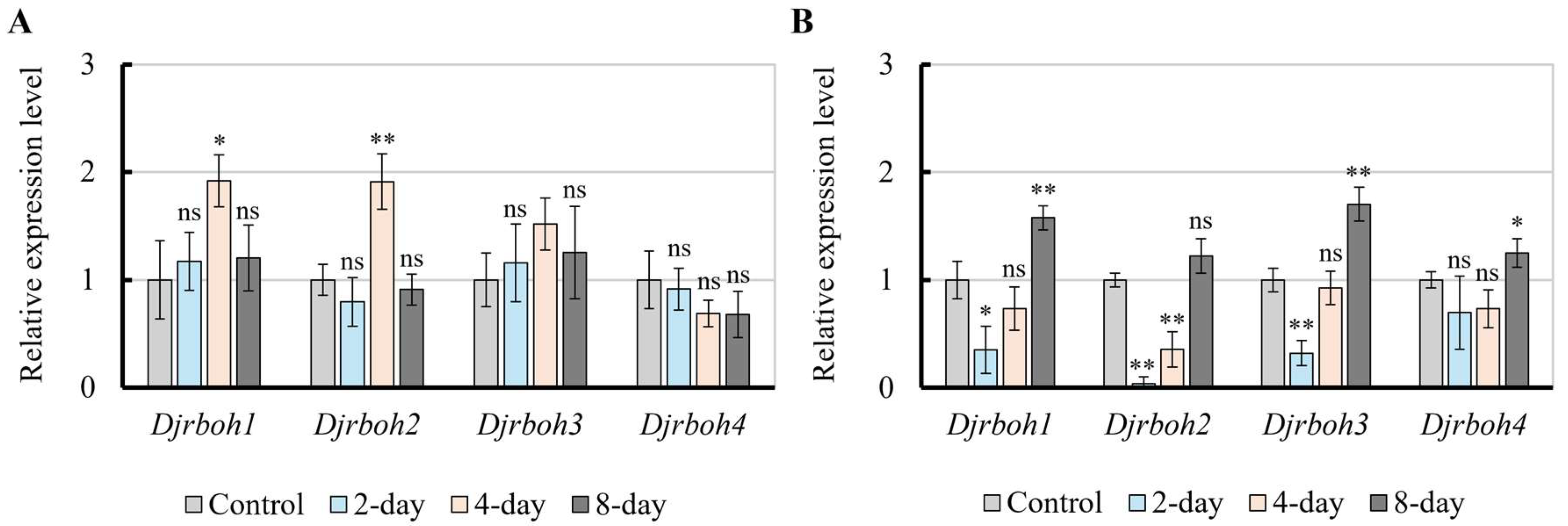

Real-time PCR revealed that during O. heterosiphoniae infection, the expression of Djrboh1 and 2 increased approximately 2-fold, over control levels, on day 4 and recovered by 8 days, while Djrboh 3, 4 genes showed no obvious changes during the first 8 days of infection (Fig. 6A). In O. dasysiphoniae infection, expressions of Djrboh1, 2, and 3 were downregulated on day 2, expression of Djrboh1 and of Djrboh3 were restored by day 4 but not Djrboh2. Expression of Djrboh4 did not change significantly on days 2 and 4 of infection (Fig. 6B). By day 8 post-infection, the expression of Djrboh1, Djrboh3, and Djrboh4 all increased (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Relative expression level of four Djrboh genes (1-4) during Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae and O. dasysiphoniae infection in Dasysiphonia japonica. (A) Real-time PCR results of O. heterosiphoniae infection, showing increased expression in Djrboh q and 2 after days 2 and 4. (B) Real-time PCR results of O. dasysiphoniae infection, showing both up-regulation or down-regulation of all copies even after 8 days. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (one-way ANOVA vs. control, n = 3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ns, non- significant.

Figure 6.

Relative expression level of four Djrboh genes (1-4) during Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae and O. dasysiphoniae infection in Dasysiphonia japonica. (A) Real-time PCR results of O. heterosiphoniae infection, showing increased expression in Djrboh q and 2 after days 2 and 4. (B) Real-time PCR results of O. dasysiphoniae infection, showing both up-regulation or down-regulation of all copies even after 8 days. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (one-way ANOVA vs. control, n = 3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ns, non- significant.

4. Discussion

In this study, red algae Dasysiphonia japonica infected with O. heterosiphoniae accumulated reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the host cell membrane, whereas this was not observed with O. dasysiphoniae infection. Treatment with diphenylene iodonium (DPI), an NADPH oxidase inhibitor that catalyzes ROS in the membrane, increased the infectivity of O. heterosiphoniae infection but did not change the infectivity of O. dasysiphoniae. Accumulation of hydrogen peroxide was also observed at the level of whole plant in O. heterosiphoniae infection, but not in O. dasysiphoniae infection in early infection. Four NADPH-oxidase genes (Djrboh1-4) were found in D. japonica. Real-time PCR of four NADPH oxidase genes (Djrboh1-4) showed that two were upregulated (Djrboh1, 2) at the onset of Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae infection, but not during infection with O. dasysiphoniae in early infection that does not induce SAR.

ROS are a major cause of cellular damage, recent studies have shown that they act as key signaling molecules in most organisms (

Inupakutika et al. 2016, Hong et al. 2024a). In plant immune responses, ROS signaling is always accompanied by cell death (

Torres et al. 2002), while in other cellular physiological processes usually proceeds without cell death (

Chapman et al. 2019, Zandalinas et al. 2020). However, infection with the pathogen

O. heterosiphoniae in the red alga

D. japonica resulted in the production of ROS in host cell membrane but was not accompanied by cell death, and no ROS were observed early in the infection (2, 4 days after infection) in

O. dasysiphoniae infections that underwent cell death. Hydrogen peroxide which synthesized by NADPH-oxidase in cell membrane diffused between cells can act as a systemic signal, cause changes in other proteins to active defense strategy, and cell death as a part of such as oxidative burst (OB) and hypersensitive response (HR) (

Perez and Brown 2014, Niks et al. 2015, Inupakutika et al. 2016, Wu et al. 2023). However, in

D. japonica infected with

O. heterosiphoniae, hydrogen peroxide accumulated throughout the plant, but no cell death was observed; conversely, in

O. dasysiphoniae infection, hydrogen peroxide did not accumulate throughout the whole plant during the early stages of infection (2 and 4 days after infection) but cell death was observed thereafter. Pretreatment with diphenylene iodonium (DPI) inhibits NADPH oxidase activity, which mediates the generation of ROS in membranes (

Moon et al. 2022), only increased infection with

O. heterosiphoniae and did not significantly change infection with

O. dasysiphoniae infection, suggesting that NADPH-oxidase is involved in resistance to infection with

O. heterosiphoniae infection.

Red algae have been using NADPH oxidase to generate ROS long before land plants, and these NADPH-oxidases genes were found in diverse red algae (

Inupakutika et al. 2016, Luo et al. 2015, Im et al. 2019, Gui et al. 2022, Shim et al. 2022, Moon et al. 2022, Hong et al. 2024b). The functional differentiation of RBOH family in red algae is also currently being investigated (

Shim et al. 2022, Moon et al. 2022, Hong et al. 2024b). In red algae,

Bmrboh1-3 are involved in fertilization (

Shim et al. 2022) and

Gmrboh1-4 are involved in cell fusion (

Moon et al. 2022), but only

Gmrboh3 is specifically involved in wound healing (

Hong et al. 2024b). Four other NADPH-oxidase genes

(Djrboh1-4) have been identified from transcriptome data; the four

Djrboh genes showed different expression patterns depending on the pathogen and the date of infection (Fig. 6). On day 4 of infection,

Djrboh1-2 was increased in

O. heterosiphoniae infection, whereas it was decreased or unchanged in

O. dasysiphoniae infection, which does not induce cell death in the host post-infection. On day 8 of infection,

Djrboh genes was not significantly changed in

O. heterosiphoniae infection, whereas

Djrboh1,

Djrboh3, and

Djrboh4 genes were increased in

O. dasysiphoniae infection, which induce cell death in the host.

In this study, we propose the existence of whole plant immune resistance, systemic acquired resistance (SAR), in the red alga D. japonica to O. heterosiphoniae infection, but that this resistance is not seen in D. japonica when infected with O. dasysiphoniae. In SAR process, the signal induced by the pathogen is transmitted to the whole plant by the appropriate concentration of ROS produced by NADPH-oxidase in the membrane without cell death response. This is not seen in O. dasysiphoniae, the whole plant is completely consumed by the pathogen with cell death, suggesting that cell death is not necessary for an effective immune response, and also that D. japonica does not produce a SAR response against O. dasysiphoniae. Future research should focus on the presence of SAR in other red algae diseases and the function of NADPH-oxidase generated ROS as a signaling molecule in disease defense.

Author Contributions

Writing, editing, visualization, X.W.; Conceptualization, G.H.K.; review and editing, G.Z., G.H.K., H.S.Y.; supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, G.H.K., and H.S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the by grants from the Management of Marine Fishery Bio-resources [Center (2024)] funded by the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK) to G.H.K, and the Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development [(Project No. RS-2023-00231243)], Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea to H.S.Y.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within this article or Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alberts, B.; Heald, R.; Johnson, A.; Morgan, D.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P.; Wilsom, J.; Hunt, T. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th ed.; Garland Science Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-081-533-218-3. ISBN 978-081-533-218-3.

- Aleem, A. A. Olpidiopsis feldmannii sp. nov., Champignon marin parasite d'Algues de la famille des Bonnemaisoniacees. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris. 1952, 235, 1250–1252.

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399.

- Badis, Y.; Klochkova, T. A.; Strittmatter, M.; Garvetto, A.; Murúa, P.; Sanderson, J. C.; Kim, G. H.; Gachon, C. M. M. Novel species of the oomycete Olpidiopsis potentially threaten European red algal cultivation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 1239–1250.

- Chakraborty, S.; Moeder, W.; Yoshioka, K. Plant immunity. Ref. Modul. Life Sci. 2017, 1–8. Kachroo, P.; Liu, H.; Kachroo, A. Salicylic acid: transport and long-distance immune signaling. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2020, 42, 53–57.

- Chapman, J. M.; Muhlemann, J. K.; Gayomba, S. R.; Muday, G. K. RBOH-dependent ROS synthesis and ROS scavenging by plant specialized metabolites to modulate plant development and stress responses. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 370–396.

- Choi, H. G.; Kraft, G. T.; Lee, I. K.; Saunders, G. W. Phylogenetic analyses of anatomical and nuclear SSU rDNA sequence data indicate that the Dasyaceae and Delesseriaceae (Ceramiales, Rhodophyta) are polyphyletic. Eur. J. Phycol. 2002, 37, 551–569.

- Coll, N. S.; Epple, P.; Dangl, J. L. Programmed cell death in the plant immune system. Cell Death Differ. 2011, 18, 1247.

- Collén, J.; Hervé, C.; Guisle-Marsollier, I.; Léger, J. J.; Boyen, C. Expression profiling of Chondrus crispus (Rhodophyta) after exposure to methyl jasmonate. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 3869–3881.

- Collén, J.; Porcel, B.; Carré, W.; Ball, S. G.; Chaparro, C.; Tonon, T., Barbeyron, T.; Michel, G.; Noel, B.; Valentin, K.; et al. Genome structure and metabolic features in the red seaweed Chondrus crispus shed light on evolution of the Archaeplastida. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 5247–5252.

- Cornu, M. Monographie des Saprolegniees, etude physiologique et systematique. Ann. Sci. Nat. Bot. 1872, 15, 1–198.

- de Oliveira, L. S.; Tschoeke, D. A.; Magalhães Lopes, A. C. R.; Sudatti, D. B.; Meirelles, P. M.; Thompson, C. C.; Pereira, R. C.; Thompson, F. L. Molecular mechanisms for microbe recognition and defense by the red seaweed Laurencia dendroidea. Msphere. 2017, 2, 10–1128.

- Diehl, N.; Kim, G. H.; Zuccarello, G. A pathogen of New Zealand Pyropia plicata (Bangiales, Rhodophyta), Pythium porphyrae (Oomycota). Algae 2017, 32, 29–39.

- Egan, S.; Fernandes, N. D.; Kumar, V.; Gardiner, M.; Thomas, T. Bacterial pathogens, virulence mechanism and host defence in marine macroalgae. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 925–938.

- Farvardin, A.; González-Hernández, A. I.; Llorens, E.; García-Agustín, P.; Scalschi, L.; Vicedo, B. The apoplast: a key player in plant survival. Antioxidants. 2020, 9, 604.

- Felle, H. H.; Herrmann, A.; Hückelhoven, R.; Kogel, K. H. Root-to-shoot signaling: apoplastic alkalinization, a general stress response and defence factor in barley (Hordeum vulgare). Protoplasma. 2005, 227, 17–24.

- Foreman, J.; Demidchik, V.; Bothwell, J. H.; Mylona, P.; Miedema, H.; Torres, M. A.; Linstead, P.; Costa, S.; Brownlee, C.; Jones, J. D. L.; et al. Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase regulate plant cell growth. Nature 2003, 422, 442–446.

- Fu, Z. Q.; Dong, X. Systemic acquired resistance: turning local infection into global defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 839–863.

- Fujita, M.; Fujita, Y.; Noutoshi, Y.; Takahashi, F.; Narusaka, Y.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: a current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006, 9, 436–442.

- Gachon, C. M.; Sime-Ngando, T.; Strittmatter, M.; Chambouvet, A.; Kim, G. H. Algal diseases: spotlight on a black box. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 633–640.

- Govrin, E. M.; Levine, A. The hypersensitive response facilitates plant infection by the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Curr. Biol. 2000, 10, 751–757.

- Gui, T. Y.; Gao, D. H.; Ding, H. C.; Yan, X. H. Identification of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rboh) family genes from Pyropia yezoensis and their correlation with archeospore release. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 929299.

- Han, S. W.; Jung, H. W. Molecular sensors for plant immunity; pattern recognition receptors and race-specific resistance proteins. J. Plant Biol. 2013, 56, 357–366.

- Heller, J.; Tudzynski, P. Reactive oxygen species in phytopathogenic fungi: signaling, development, and disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011, 49, 369–390.

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N. S. Reactive oxygen species signaling and oxidative stress: transcriptional regulation and evolution. Antioxidants 2024a, 13, 312.

- Hong, C. Y.; Yun, J. H.; Kim, G. H. Ca2+-mediated reactive oxygen species signaling regulates cell repair after mechanical wounding in the red alga Griffithsia monilis. J. Phycol. 2024b, 60, 853–870.

- Huang, H.; Ullah, F.; Zhou, D. X.; Yi, M.; Zhao, Y. Mechanisms of ROS regulation of plant development and stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 800.

- Im, S. H.; Klochkova, T. A.; Lee, D. J.; Gachon, C. M.; Kim, G. H. Genetic toolkits of the red alga Pyropia tenera against the three most common diseases in Pyropia farms. J. Phycol. 2019, 55, 801–815.

- Inupakutika, M. A.; Sengupta, S.; Devireddy, A. R.; Azad, R. K.; Mittler, R. The evolution of reactive oxygen species metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, erw382.

- Janeway, C.; Travers, P.; Walport, M.; Shlomchik, M. Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease, 5th ed.; Garland Science Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 081-533-642-X. ISBN 081-533-642-X.

- Kadota, Y.; Shirasu, K.; Zipfel, C. Regulation of the NADPH oxidase RBOHD during plant immunity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 1472–1480.

- Kamle, M.; Borah, R.; Bora, H.; Jaiswal, A. K.; Singh, R. K.; Kumar, P. Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (ISR): role and mechanism of action against phytopathogens. Fungal biol. Biotechnol. 2020, 457–470.

- Kim, G. H.; Moon, K. H.; Kim, J. Y.; Shim, J.; Klochkova, T. A. A revaluation of algal diseases in Korean Pyropia (Porphyra) sea farms and their economic impact. Algae. 2014, 29, 249–265.

- Király, L.; Künstler, A.; Bacsó, R.; Hafez, Y.; Király, Z. Similarities and differences in plant and animal immune systems—what is inhibiting pathogens? Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hung. 2013, 48, 187–205.

- Klochkova, T. A.; Jung, S.; Kim, G. H. Host range and salinity tolerance of Pythium porphyrae may indicate its terrestrial origin. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016a, 29, 371–379.

- Klochkova, T. A.; Shin, Y. J.; Moon, K. H.; Motomura, T.; Kim, G. H. New species of unicellular obligate parasite, Olpidiopsis pyropiae sp. nov., that plagues Pyropia sea farms in Korea. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016b, 28, 73–83.

- Klochkova, T. A.; Kwak, M. S.; Kim, G. H. A new endoparasite Olpidiopsis heterosiphoniae sp. nov. that infects red algae in Korea. Algal Res. 2017, 28, 264–269.

- Krupina, M. V.; Dathe, W. Occurrence of jasmonic acid in the red alga Gelidium latifolium. Z. Naturforsch. C. 1991, 46, 1127–1129.

- Kwak, M. S.; Klochkova, T. A.; Jeong, S.; Kim, G. H. Olpidiopsis porphyrae var. koreanae, an endemic endoparasite infecting cultivated Pyropia yezoensis in Korea. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 2003–2012.

- Länge, S.; Wissmann, J.D.; Plattner, H. Caffeine inhibits Ca2+ uptake by subplasmalemmal calcium stores (‘alveolar sacs’) isolated from Paramecium cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 1996, 1278, 191–196.

- Li, N.; Han, X.; Feng, D.; Yuan, D.; Huang, L. J. Signaling crosstalk between salicylic acid and ethylene/jasmonate in plant defense: do we understand what they are whispering? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 671.

- Li, M.; Yu, G.; Cao, C.; Liu, P. Metabolism, signaling, and transport of jasmonates. Plant Commun. 2021, 2.

- Lightfoot, D. J.; Boettcher, A.; Little, A.; Shirley, N.; Able, A. J. Identification and characterisation of barley (Hordeum vulgare) respiratory burst oxidase homologue family members. Funct. Plant Biol. 2008, 35, 347–359.

- Luo, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, R.; Qian, F.; Yan, X.; Chen, H. Characterization of a respiratory burst oxidase homologue from Pyropia haitanensis with unique molecular phylogeny and rapid stress response. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 27, 945–955.

- Maekawa, T.; Kufer, T. A.; Schulze-Lefert, P. NLR functions in plant and animal immune systems: so far and yet so close. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 817–826.

- Marino, D.; Dunand, C.; Puppo, A.; Pauly, N. A burst of plant NADPH oxidases. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 9–15.

- Mandal, M.; Sarkar, M.; Khan, A.; Biswas, M.; Masi, A.; Rakwal, R.; Agrawal, G. K.; Srivastava, A.; Sarkar, A. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) in plants–maintenance of structural individuality and functional blend. Adv Redox Res. 2022, 5, 100039.

- McDowell, J. M.; Hoff, T.; Anderson, R. G.; Deegan, D. Propagation, storage, and assays with Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis: a model oomycete pathogen of Arabidopsis. In Plant immunity methods and protocols.; McDowell, J. M., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 137–151, ISBN 978-161-737-997-0. ISBN 978-161-737-997-0.

- Mishina, T. E.; Zeier, J. Pathogen-associated molecular pattern recognition rather than development of tissue necrosis contributes to bacterial induction of systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007, 50, 500–513.

- Moon, J. S.; Hong, C. Y.; Lee, J. W.; Kim, G. H. ROS signaling mediates directional cell elongation and somatic cell fusion in the red alga Griffithsia monilis. Cells. 2022, 11, 2124.

- Muthamilarasan, M.; Prasad, M. Plant innate immunity: an updated insight into defense mechanism. J. Biosci. 2013, 38, 433–449.

- Oliver, J. P.; Castro, A.; Gaggero, C.; Cascón, T.; Schmelz, E. A.; Castresana, C.; Ponce de Leon, I. Pythium infection activates conserved plant defense responses in mosses. Planta 2009, 230, 569–579.

- Niks, R. E.; Qi, X.; Marcel, T. C. Quantitative resistance to biotrophic filamentous plant pathogens: concepts, misconceptions, and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2015, 53, 445–470.

- Pereira, R. C.; Vasconcelos, M. A. Chemical defense in the red seaweed Plocamium brasiliense: spatial variability and differential action on herbivores. Braz. J. Biol. 2014, 74, 545–552.

- Perez, I. B.; Brown, P. J. The role of ROS signaling in cross-tolerance: from model to crop. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 754.

- Ponce de León, I.; Montesano, M. Adaptation mechanisms in the evolution of moss defenses to microbes. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 366.

- Radwan, D. E. M.; Fayez, K. A.; Mahmoud, S. Y.; Hamad, A.; Lu, G. Physiological and metabolic changes of Cucurbita pepo leaves in response to zucchini yellow mosaic virus (ZYMV) infection and salicylic acid treatments. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2007, 45, 480–489.

- Savoie, A. M.; Saunders, G. W. First record of the invasive red alga Heterosiphonia japonica (Ceramiales, Rhodophyta) in Canada. Bioinvasions Rec. 2013, 2, 27–32.

- Sekimoto, S.; Yokoo, K.; Kawamura, Y.; Honda, D. Taxonomy, molecular phylogeny, and ultrastructural morphology of Olpidiopsis porphyrae sp. nov. (Oomycetes, straminipiles), a unicellular obligate endoparasite of Bangia and Porphyra spp. (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). Mycol. Res. 2008, 112, 361–374.

- Sekimoto, S.; Klochkova, T. A.; West, J. A.; Beakes, G. W.; Honda, D. Olpidiopsis bostrychiae sp. nov.: an endoparasitic oomycete that infects Bostrychia and other red algae (Rhodophyta). Phycologia 2009, 48, 460–472.

- Seyfferth, C.; Tsuda, K. Salicylic acid signal transduction: the initiation of biosynthesis, perception and transcriptional reprogramming. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 697.

- Shim, E.; Lee, J. W.; Park, H.; Zuccarello, G. C.; Kim, G. H. Hydrogen peroxide signaling mediates fertilization and post-fertilization development in the red alga Bostrychia moritziana. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 727–741.

- Shine, M. B.; Xiao, X.; Kachroo, P.; Kachroo, A. Signaling mechanisms underlying systemic acquired resistance to microbial pathogens. Plant Sci. 2019, 279, 81–86.

- Sjøtun, K.; Husa, V.; Peña, V. Present distribution and possible vectors of introductions of the alga Heterosiphonia japonica (Ceramiales, Rhodophyta) in Europe. Aquat. Invasions. 2008, 3, 377–394.

- Tang, L.; Qiu, L.; Liu, C.; Du, G.; Mo, Z.; Tang, X.; Mao, Y. Transcriptomic insights into innate immunity responding to red rot disease in red alga Pyropia yezoensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5970.

- Thapa, H. R.; Lin, Z.; Yi, D.; Smith, J. E.; Schmidt, E. W.; Agarwal, V. Genetic and biochemical reconstitution of bromoform biosynthesis in Asparagopsis lends insights into seaweed reactive oxygen species enzymology. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 1662–1670.

- Torres, M. A.; Dangl, J. L.; Jones, J. D. Arabidopsis gp91phox homologues AtrbohD and AtrbohF are required for accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates in the plant defense response. PNAS. 2002, 99, 517–522.

- Uppalapati, S. R.; Fujita, Y. Carbohydrate regulation of attachment, encystment, and appressorium formation by Pythium porphyrae (Oomycota) zoospores on Porphyra yezoensis (Rhodophyta). J. Phycol. 2000, 36, 359–366.

- Wang, L.; Mao, Y.; Kong, F.; Li, G.; Ma, F.; Zhang, B.; Sun, P.; Bi, G.; Zhang, F., Xue, H.; et al. Complete sequence and analysis of plastid genomes of two economically important red algae: Pyropia haitanensis and Pyropia yezoensis. PloS one 2013, 8, e65902.

- Weinberger, F. Pathogen-induced defense and innate immunity in macroalgae. Biol. Bull. 2007, 213, 290–302.

- Wen, X.; Zuccarello, G. C.; Klochkova, T. A.; Kim, G. H. Oomycete pathogens, red algal defense mechanisms and control measures. Algae 2023, 38, 203–215.

- Wen, X.; Zuccarello, G. C.; Yoon, H. S.; Kim, G. H. A new oomycete pathogen Olpidiopsis dasysiphoniae sp. nov. (Oomycota) infecting the red alga Dasysiphonia spp. (Ceramiales, Delesseriaceae). Bot. Mar. 2025, Minor revision.

- Whittick, A.; South, G. R. Olpidiopsis antithamnionis nov. sp. (Oomycetes, Olpidiopsidaceae), a parasite of Antithamnion floccosum (OF Müll.) Kleen from Newfoundland. Arch. Mikrobiol. 1972, 82, 353–360.

- Wojtaszek, P. Oxidative burst: an early plant response to pathogen infection. Biochem. J, 1997, 322, 681–692.

- Wu, B.; Qi, F.; Liang, Y. Fuels for ROS signaling in plant immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 1124–1131.

- Zandalinas, S. I.; Fichman, Y.; Mittler, R. Vascular bundles mediate systemic reactive oxygen signaling during light stress. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3425–3435.

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Ding, P.; Wang, D.; Cheng, Y. T.; He, J.; Gao, M.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Control of salicylic acid synthesis and systemic acquired resistance by two members of a plant-specific family of transcription factors. PNAS. 2010, 107, 18220–18225.

- Zhang, X.; Krause, K. H.; Xenarios, I.; Soldati, T.; Boeckmann, B. Evolution of the ferric reductase domain (FRD) superfamily: modularity, functional diversification, and signature motifs. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e58126.

- Zuccarello, G. C.; Gachon, C. M.; Badis, Y.; Murúa, P.; Garvetto, A.; Kim, G. H. Holocarpic oomycete parasites of red algae are not Olpidiopsis, but neither are they all Pontisma or Sirolpidium (Oomycota). Algae 2024, 39, 43–50.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).