Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

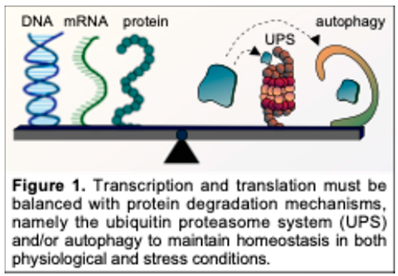

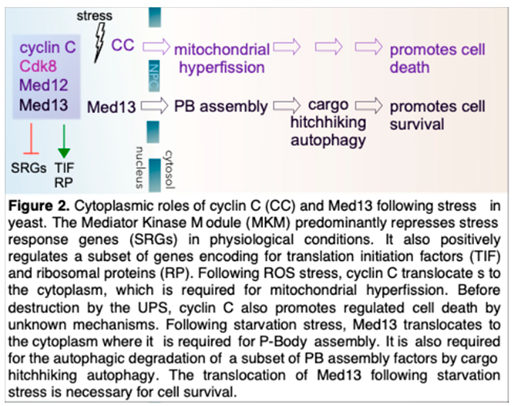

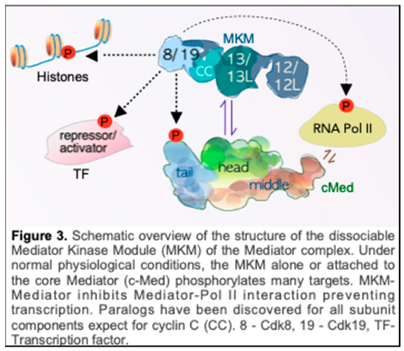

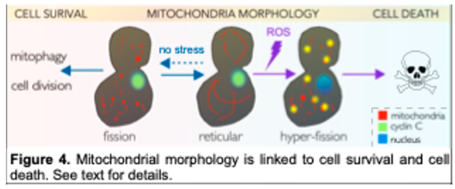

Following unfavorable environmental cues, cells reprogram pathways that govern transcription, translation, and protein degradation systems. This reprogramming is essential to restore homeostasis or commit to cell death. This review focuses on the secondary roles of two nuclear transcriptional regulators, cyclin C and Med13, that play key roles in this decision processing. Both proteins are members of the Mediator kinase module (MKM) of the Mediator complex, which, under normal physiological conditions, positively and negatively regulates a subset of stress response genes. However, cyclin C and Med13 translocate to the cytoplasm following cell death and cell survival cue, respectively, interacting with a host of cell death and cell survival proteins. In the cytoplasm, cyclin C is required for stress-induced mitochondrial hyper-fission and promotes regulated cell death pathways. Cytoplasmic Med13 promotes stress-induced assembly of processing bodies (P-bodies) and is required for the autophagic degradation of a subset of P-body assembly factors by cargo hitchhiking autophagy. This review will focus on these secondary, a.k.a. "nigh" jobs" of "cyclin C and Med13, outlining the importance of these secondary functions in maintaining cellular homeostasis following stress.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Structure of the CKM

3. Transcriptional Reprogramming by the MKM Following Stress

4. Mechanisms of CKM Disassembly

5. The Roles of Cytoplasmic Cyclin C

6. Cytoplasmic Roles of Med13

7. Diseases Associated with the MKM

8. Outlook

Funding

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interest

Abbreviations

References

- Koyuncu, S., et al., Rewiring of the ubiquitinated proteome determines ageing in C. elegans. Nature, 2021. 596(7871): p. 285-290. [CrossRef]

- Kevei, É. and T. Hoppe, Ubiquitin sets the timer: impacts on aging and longevity. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 2014. 21(4): p. 290-292. [CrossRef]

- Tramutola, A., et al., It Is All about (U)biquitin: Role of Altered Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and UCHL1 in Alzheimer Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2016. 2016: p. 2756068. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.O., et al., Mitochondrial hyperfusion via metabolic sensing of regulatory amino acids. Cell Reports, 2022. 40(7): p. 111198. [CrossRef]

- Aman, Y., et al., Autophagy in healthy aging and disease. Nature Aging, 2021. 1(8): p. 634-650. [CrossRef]

- Leidal, A.M., B. Levine, and J. Debnath, Autophagy and the cell biology of age-related disease. Nature Cell Biology, 2018. 20(12): p. 1338-1348. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J., et al., Ubiquitin–proteasome system as a target for anticancer treatment—an update. Archives of Pharmacal Research, 2023. 46(7): p. 573-597.

- Ajmal, M.R., Protein Misfolding and Aggregation in Proteinopathies: Causes, Mechanism and Cellular Response. Diseases, 2023. 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Louros, N., J. Schymkowitz, and F. Rousseau, Mechanisms and pathology of protein misfolding and aggregation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2023. 24(12): p. 912-933. [CrossRef]

- Dawes, I.W. and G.G. Perrone, Stress and ageing in yeast. FEMS Yeast Research, 2019. 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Cazzanelli, G., et al., The Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a Model for Understanding RAS Proteins and their Role in Human Tumorigenesis. Cells, 2018. 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, F., et al., A Cyclam Salt as an Antifungal Agent: Interference with Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans Mechanisms of Virulence. Antibiotics (Basel), 2024. 13(3).

- Stieber, H., et al., The sphingolipid inhibitor myriocin increases Candida auris susceptibility to amphotericin B. Mycoses, 2024. 67(4): p. e13723. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.L., et al., Elimination of virus-like particles reduces protein aggregation and extends replicative lifespan in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2024. 121(14): p. e2313538121. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. and R. Xu, Invertebrate genetic models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Mol Neurosci, 2024. 17: p. 1328578. [CrossRef]

- Rencus-Lazar, S., et al., Yeast Models for the Study of Amyloid-Associated Disorders and Development of Future Therapy. Front Mol Biosci, 2019. 6: p. 15. [CrossRef]

- Koller, H. and L.B. Perkins, Brewing and the Chemical Composition of Amine-Containing Compounds in Beer: A Review. Foods, 2022. 11(3). [CrossRef]

- Reiter, T., et al., Transcriptomics Provides a Genetic Signature of Vineyard Site and Offers Insight into Vintage-Independent Inoculated Fermentation Outcomes. mSystems, 2021. 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al., Stress tolerance enhancement via SPT15 base editing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Biofuels, 2021. 14(1): p. 155. [CrossRef]

- Postaru, M., et al., Cellular Stress Impact on Yeast Activity in Biotechnological Processes-A Short Overview. Microorganisms, 2023. 11(10). [CrossRef]

- Minden, S., et al., Performing in spite of starvation: How Saccharomyces cerevisiae maintains robust growth when facing famine zones in industrial bioreactors. Microb Biotechnol, 2023. 16(1): p. 148-168. [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M., et al., Role of Yeasts in the Brewing Process: Tradition and Innovation. Processes, 2021. 9(5): p. 839. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T., et al., Breeding of high-tolerance yeast by adaptive evolution and high-gravity brewing of mutant. J Sci Food Agric, 2024. 104(2): p. 686-697. [CrossRef]

- Hou, D., et al., Effect of environmental stresses during fermentation on brewing yeast and exploration on the novel flocculation-associated function of RIM15 gene. Bioresour Technol, 2023. 379: p. 129004. [CrossRef]

- Soutourina, J., Transcription regulation by the Mediator complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2018. 19(4): p. 262-274.

- Galbraith, M.D., A.J. Donner, and J.M. Espinosa, CDK8: a positive regulator of transcription. Transcription, 2010. 1(1): p. 4-12.

- Fant, C.B. and D.J. Taatjes, Regulatory functions of the Mediator kinases CDK8 and CDK19. Transcription, 2019. 10(2): p. 76-90. [CrossRef]

- Bancerek, J., et al., CDK8 kinase phosphorylates transcription factor STAT1 to selectively regulate the interferon response. Immunity, 2013. 38(2): p. 250-62. [CrossRef]

- Steinparzer, I., et al., Transcriptional Responses to IFN-γ Require Mediator Kinase-Dependent Pause Release and Mechanistically Distinct CDK8 and CDK19 Functions. Molecular Cell, 2019. 76(3): p. 485-499.e8. [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, C., et al., Nuclear CDKs drive Smad transcriptional activation and turnover in BMP and TGF-beta pathways. Cell, 2009. 139(4): p. 757-69. [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.J., et al., E2F1 represses β-catenin transcription and is antagonized by both pRB and CDK8. Nature, 2008. 455(7212): p. 552-556. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., et al., Regulation of lipogenesis by cyclin-dependent kinase 8-mediated control of SREBP-1. J Clin Invest, 2012. 122(7): p. 2417-27. [CrossRef]

- Hirst, M., et al., GAL4 is regulated by the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme-associated cyclin-dependent protein kinase SRB10/CDK8. Mol Cell, 1999. 3(5): p. 673-8.

- Vincent, O., et al., Interaction of the Srb10 kinase with Sip4, a transcriptional activator of gluconeogenic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol, 2001. 21(17): p. 5790-6.

- Cooper, K.F., Cargo hitchhiking autophagy - a hybrid autophagy pathway utilized in yeast. Autophagy, 2025: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.L., et al., A conserved Mediator-CDK8 kinase module association regulates Mediator-RNA polymerase II interaction. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2013. 20(5): p. 611-9. [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.L. and D.J. Taatjes, The Mediator complex: a central integrator of transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2015. 16(3): p. 155-66. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.J., et al., Molecular architecture of the yeast Mediator complex. Elife, 2015. 4. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., T.C. Chao, and K.L. Tsai, Structures and compositional dynamics of Mediator in transcription regulation. Curr Opin Struct Biol, 2024. 88: p. 102892. [CrossRef]

- Chao, T.C., et al., Structural basis of the human transcriptional Mediator regulated by its dissociable kinase module. Mol Cell, 2024. 84(20): p. 3932-3949.e10. [CrossRef]

- Elmlund, H., et al., The cyclin-dependent kinase 8 module sterically blocks Mediator interactions with RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2006. 103(43): p. 15788-93. [CrossRef]

- Knuesel, M.T., et al., The human CDK8 subcomplex is a histone kinase that requires Med12 for activity and can function independently of Mediator. Mol Cell Biol, 2009. 29(3): p. 650-61. [CrossRef]

- Osman, S., et al., The Cdk8 kinase module regulates interaction of the mediator complex with RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem, 2021. 296: p. 100734. [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, N., et al., Mediator Undergoes a Compositional Change during Transcriptional Activation. Mol Cell, 2016. 64(3): p. 443-454454. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.A., et al., The SCF-Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase degrades MED13 and MED13L and regulates CDK8 module association with Mediator. Genes Dev, 2013. 27(2): p. 151-6. [CrossRef]

- Mo, X., et al., Ras induces mediator complex exchange on C/EBP beta. Mol Cell, 2004. 13(2): p. 241-50.

- Pavri, R., et al., PARP-1 determines specificity in a retinoid signaling pathway via direct modulation of Mediator. Mol Cell, 2005. 18(1): p. 83-96. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E., et al., From structure to molecular condensates: emerging mechanisms for Mediator function. FEBS J, 2023. 290(2): p. 286-309. [CrossRef]

- Holstege, F.C., et al., Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell, 1998. 95(5): p. 717-28. [CrossRef]

- Anandhakumar, J., et al., Evidence for Multiple Mediator Complexes in Yeast Independently Recruited by Activated Heat Shock Factor. Mol Cell Biol, 2016. 36(14): p. 1943-60. [CrossRef]

- Donner, A.J., et al., CDK8 is a positive regulator of transcriptional elongation within the serum response network. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2010. 17(2): p. 194-201. [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, M.D., et al., HIF1A employs CDK8-mediator to stimulate RNAPII elongation in response to hypoxia. Cell, 2013. 153(6): p. 1327-39. [CrossRef]

- Richter, W.F., et al., The Mediator complex as a master regulator of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2022. 23(11): p. 732-749. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.F., et al., Stress and developmental regulation of the yeast C-type cyclin Ume3p (Srb11p/Ssn8p). EMBO J, 1997. 16(15): p. 4665-75. [CrossRef]

- Stieg, D.C., K.F. Cooper, and R. Strich, The extent of cyclin C promoter occupancy directs changes in stress-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem, 2020. 295(48): p. 16280-16291. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C., et al., Structure and noncanonical Cdk8 activation mechanism within an Argonaute-containing Mediator kinase module. Sci Adv, 2021. 7(3). [CrossRef]

- Jeronimo, C. and F. Robert, The Mediator Complex: At the Nexus of RNA Polymerase II Transcription. Trends Cell Biol, 2017. 27(10): p. 765-783. [CrossRef]

- Echalier, A., J.A. Endicott, and M.E. Noble, Recent developments in cyclin-dependent kinase biochemical and structural studies. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2010. 1804(3): p. 511-9. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.V., et al., The structure of CDK8/CycC implicates specificity in the CDK/cyclin family and reveals interaction with a deep pocket binder. J Mol Biol, 2011. 412(2): p. 251-66. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D., et al., Suppression of Mediator is regulated by Cdk8-dependent Grr1 turnover of the Med3 coactivator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(7): p. 2500-5. [CrossRef]

- Fryer, C.J., J.B. White, and K.A. Jones, Mastermind recruits CycC:CDK8 to phosphorylate the Notch ICD and coordinate activation with turnover. Mol Cell, 2004. 16(4): p. 509-20. [CrossRef]

- Alber, F., et al., The molecular architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Nature, 2007. 450(7170): p. 695-701. [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.S., et al., CDK8 maintains tumor dedifferentiation and embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Cancer Res, 2012. 72(8): p. 2129-39.

- Chen, M., et al., CDK8/19 Mediator kinases potentiate induction of transcription by NFkappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017. 114(38): p. 10208-10213.

- Hirst, K., et al., The transcription factor, the Cdk, its cyclin and their regulator: directing the transcriptional response to a nutritional signal. Embo j, 1994. 13(22): p. 5410-20. [CrossRef]

- Lenssen, E., et al., The Ccr4-not complex regulates Skn7 through Srb10 kinase. Eukaryot Cell, 2007. 6(12): p. 2251-9. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, K.A., et al., Enhanced T cell effector activity by targeting the Mediator kinase module. Science, 2022. 378(6620): p. eabn5647. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., et al., CDK8 and CDK19: positive regulators of signal-induced transcription and negative regulators of Mediator complex proteins. Nucleic Acids Research, 2023. 51(14): p. 7288-7313. [CrossRef]

- Stieg, D.C., et al., Cyclin C Regulated Oxidative Stress Responsive Transcriptome in Mus musculus Embryonic Fibroblasts. G3 (Bethesda), 2019. 9(6): p. 1901-1908.

- Hengartner, C.J., et al., Temporal regulation of RNA polymerase II by Srb10 and Kin28 cyclin-dependent kinases. Mol Cell, 1998. 2(1): p. 43-53. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.F. and R. Strich, Functional analysis of the Ume3p/ Srb11p-RNA polymerase II holoenzyme interaction. Gene Expr, 1999. 8(1): p. 43-57. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W., et al., MED16 and MED23 of Mediator are coactivators of lipopolysaccharide- and heat-shock-induced transcriptional activators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(33): p. 12153-8.

- Kuchin, S., P. Yeghiayan, and M. Carlson, Cyclin-dependent protein kinase and cyclin homologs SSN3 and SSN8 contribute to transcriptional control in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1995. 92(9): p. 4006-10. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.F., M.J. Mallory, and R. Strich, Oxidative stress-induced destruction of the yeast C-type cyclin Ume3p requires phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C and the 26S proteasome. Mol Cell Biol, 1999. 19(5): p. 3338-48. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.F. and R. Strich, Saccharomyces cerevisiae C-type cyclin Ume3p/Srb11p is required for efficient induction and execution of meiotic development. Eukaryot Cell, 2002. 1(1): p. 66-74. [CrossRef]

- Wahi, M. and A.D. Johnson, Identification of genes required for alpha 2 repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 1995. 140: p. 79-90. [CrossRef]

- Bjorklund, S. and C.M. Gustafsson, The yeast Mediator complex and its regulation. Trends Biochem Sci, 2005. 30(5): p. 240-4. [CrossRef]

- van de Peppel, J., et al., Mediator expression profiling epistasis reveals a signal transduction pathway with antagonistic submodules and highly specific downstream targets. Mol Cell, 2005. 19(4): p. 511-22. [CrossRef]

- Surosky, R.T., R. Strich, and R.E. Esposito, The yeast UME5 gene regulates the stability of meiotic mRNAs in response to glucose. Mol Cell Biol, 1994. 14(5): p. 3446-58.

- Strich, R., M.R. Slater, and R.E. Esposito, Identification of negative regulatory genes that govern the expression of early meiotic genes in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 1989. 86: p. 10018-10022. [CrossRef]

- Willis, S.D., et al., Cyclin C-Cdk8 Kinase Phosphorylation of Rim15 Prevents the Aberrant Activation of Stress Response Genes. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022. 10: p. 867257. [CrossRef]

- Hanley, S.E., S.D. Willis, and K.F. Cooper, Snx4-assisted vacuolar targeting of transcription factors defines a new autophagy pathway for controlling ATG expression. Autophagy, 2021. 17(11): p. 3547-3565. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.F., et al., Oxidative-stress-induced nuclear to cytoplasmic relocalization is required for Not4-dependent cyclin C destruction. J Cell Sci, 2012. 125(Pt 4): p. 1015-26. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.F., et al., Stress-induced nuclear-to-cytoplasmic translocation of cyclin C promotes mitochondrial fission in yeast. Dev Cell, 2014. 28(2): p. 161-73. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., et al., Cyclin C mediates stress-induced mitochondrial fission and apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell, 2015. 26(6): p. 1030-43. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, V., et al., Cyclin C directly stimulates Drp1 GTP affinity to mediate stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfission. Mol Biol Cell, 2019. 30(3): p. 302-311ctly stimulates Drp1 GTP affinity to mediate stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfission. Mol Biol Cell, 2019. 30(3): p. 302-311. [CrossRef]

- Jezek, J., et al., Mitochondrial translocation of cyclin C stimulates intrinsic apoptosis through Bax recruitment. EMBO Rep, 2019. 20(9): p. e47425. [CrossRef]

- Ježek, J., et al., Cyclin C: The Story of a Non-Cycling Cyclin. Biology (Basel), 2019. 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Hanley, S.E., et al., Med13 is required for efficient P-body recruitment and autophagic degradation of Edc3 following nitrogen starvation. Mol Biol Cell, 2024. 35(11): p. ar142. [CrossRef]

- Hanley, S.E., et al., Ksp1 is an autophagic receptor protein for the Snx4-assisted autophagy of Ssn2/Med13. Autophagy, 2024. 20(2): p. 397-415. [CrossRef]

- Friedson, B., et al., The CDK8 kinase module: A novel player in the transcription of translation initiation and ribosomal genes. Mol Biol Cell, 2025. 36(1): p. ar2.

- Shore, D. and B. Albert, Ribosome biogenesis and the cellular energy economy. Curr Biol, 2022. 32(12): p. R611-r61711-r617. [CrossRef]

- Hirai, H. and K. Ohta, Comparative Research: Regulatory Mechanisms of Ribosomal Gene Transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biomolecules, 2023. 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.E., Regulation of cell wall biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the cell wall integrity signaling pathway. Genetics, 2011. 189(4): p. 1145-75. [CrossRef]

- Krasley, E., et al., Regulation of the oxidative stress response through Slt2p-dependent destruction of cyclin C in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 2006. 172(3): p. 1477-86. [CrossRef]

- Jin, C., et al., The cell wall sensors Mtl1, Wsc1, and Mid2 are required for stress-induced nuclear to cytoplasmic translocation of cyclin C and programmed cell death in yeast. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2013. 2013: p. 320823. [CrossRef]

- Jin, C., R. Strich, and K.F. Cooper, Slt2p phosphorylation induces cyclin C nuclear-to-cytoplasmic translocation in response to oxidative stress. Mol Biol Cell, 2014. 25(8): p. 1396-407. [CrossRef]

- Stieg, D.C., et al., A complex molecular switch directs stress-induced cyclin C nuclear release through SCF(Grr1)-mediated degradation of Med13. Mol Biol Cell, 2018. 29(3): p. 363-375. [CrossRef]

- Khakhina, S., K.F. Cooper, and R. Strich, Med13p prevents mitochondrial fission and programmed cell death in yeast through nuclear retention of cyclin C. Mol Biol Cell, 2014. 25(18): p. 2807-16. [CrossRef]

- Nash, P., et al., Multisite phosphorylation of a CDK inhibitor sets a threshold for the onset of DNA replication. Nature, 2001. 414(6863): p. 514-21. [CrossRef]

- Ang, X.L. and J. Wade Harper, SCF-mediated protein degradation and cell cycle control. Oncogene, 2005. 24(17): p. 2860-70. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.P. and M. Carlson, Regulation of snf1 protein kinase in response to environmental stress. J Biol Chem, 2007. 282(23): p. 16838-45. [CrossRef]

- Willis, S.D., et al., Snf1 cooperates with the CWI MAPK pathway to mediate the degradation of Med13 following oxidative stress. Microbial Cell, 2018. 5(8): p. 357-370ith the CWI MAPK pathway to mediate the degradation of Med13 following oxidative stress. Microbial Cell, 2018. 5(8): p. 357-370. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., et al., Interplay of energy metabolism and autophagy. Autophagy, 2024. 20(1): p. 4-14.

- Willis, S.D., et al., Ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated cyclin C degradation promotes cell survival following nitrogen starvation. Mol Biol Cell, 2020. 31(10): p. 1015-1031. [CrossRef]

- Rambold, A.S., et al., Tubular network formation protects mitochondria from autophagosomal degradation during nutrient starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011. 108(25): p. 10190-5. [CrossRef]

- Torres, J., et al., Regulation of the cell integrity pathway by rapamycin-sensitive TOR function in budding yeast. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(45): p. 43495-504. [CrossRef]

- ežek, J., K.F. Cooper, and R. Strich, Reactive Oxygen Species and Mitochondrial Dynamics: The Yin and Yang of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cancer Progression. Antioxidants (Basel), 2018. 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Tao, W., C. Kurschner, and J.I. Morgan, Modulation of Cell Death in Yeast by the Bcl-2 Family of Proteins*. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1997. 272(24): p. 15547-15552. [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T., et al., A novel motif in the yeast mitochondrial dynamin Dnm1 is essential for adaptor binding and membrane recruitment. J Cell Biol, 2012. 199(4): p. 613-22. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q., et al., The mitochondrial fission adaptors Caf4 and Mdv1 are not functionally equivalent. PLoS One, 2012. 7(12): p. e53523. [CrossRef]

- Kraus, F., et al., Function and regulation of the divisome for mitochondrial fission. Nature, 2021. 590(7844): p. 57-66. [CrossRef]

- Bleazard, W., et al., The dynamin-related GTPase Dnm1 regulates mitochondrial fission in yeast. Nat Cell Biol, 1999. 1(5): p. 298-304al fission in yeast. Nat Cell Biol, 1999. 1(5): p. 298-304. [CrossRef]

- Zou, W., et al., Application of super-resolution microscopy in mitochondria-dynamic diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2023. 200: p. 115043. [CrossRef]

- Ingerman, E., et al., Dnm1 forms spirals that are structurally tailored to fit mitochondria. J Cell Biol, 2005. 170(7): p. 1021-7. [CrossRef]

- Mears, J.A., et al., Conformational changes in Dnm1 support a contractile mechanism for mitochondrial fission. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2011. 18(1): p. 20-6. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K., et al., Association of mitochondria with microtubules inhibits mitochondrial fission by precluding assembly of the fission protein Dnm1. J Biol Chem, 2019. 294(10): p. 3385-3396. [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, G. and T.L. Schwarz, The pathways of mitophagy for quality control and clearance of mitochondria. Cell Death Differ, 2013. 20(1): p. 31-42. [CrossRef]

- Fannjiang, Y., et al., Mitochondrial fission proteins regulate programmed cell death in yeast. Genes Dev, 2004. 18(22): p. 2785-97. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F., et al., Glucose starvation induces mitochondrial fragmentation depending on the dynamin GTPase Dnm1/Drp1 in fission yeast. J Biol Chem, 2019. 294(47): p. 17725-17734. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, B.L., et al., Disease-associated mutations in Drp1 have fundamentally different effects on the mitochondrial fission machinery. Hum Mol Genet, 2023. 32(12): p. 1975-1987.

- Oliver, D. and P.H. Reddy, Dynamics of Dynamin-Related Protein 1 in Alzheimer's Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells, 2019. 8(9). [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R., et al., Mimicking human Drp1 disease-causing mutations in yeast Dnm1 reveals altered mitochondrial dynamics. Mitochondrion, 2021. 59: p. 283-295. [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.M., K.J. Min, and T.K. Kwon, Inhibition of Drp1 Sensitizes Cancer Cells to Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis through Transcriptional Inhibition of c-FLIP Expression. Molecules, 2020. 25(24). [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y., et al., Mitochondrial Dynamin-Related Protein Drp1: a New Player in Cardio-oncology. Curr Oncol Rep, 2022. 24(12): p. 1751-1763. [CrossRef]

- Xu, R., et al., PCSK9 increases vulnerability of carotid plaque by promoting mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells. CNS Neurosci Ther, 2024. 30(2): p. e14640. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.W., et al., Ruxolitinib induces apoptosis and pyroptosis of anaplastic thyroid cancer via the transcriptional inhibition of DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fission. Cell Death Dis, 2024. 15(2): p. 125. [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, K., et al., Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in Lipotoxic Hearts Induce Post-Translational Modifications of AKAP121, DRP1, and OPA1 That Promote Mitochondrial Fission. Circ Res, 2018. 122(1): p. 58-73. [CrossRef]

- Chang, X., et al., ROS-Drp1-mediated mitochondria fission contributes to hippocampal HT22 cell apoptosis induced by silver nanoparticles. Redox Biol, 2023. 63: p. 102739. [CrossRef]

- Cid-Castro, C. and J. Morán, Differential ROS-Mediated Phosphorylation of Drp1 in Mitochondrial Fragmentation Induced by Distinct Cell Death Conditions in Cerebellar Granule Neurons. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2021. 2021: p. 8832863. [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Gutierrez, D., et al., Guidelines and recommendations on yeast cell death nomenclature. Microb Cell, 2018. 5(1): p. 4-31. [CrossRef]

- Madeo, F., et al., A caspase-related protease regulates apoptosis in yeast. Mol Cell, 2002. 9(4): p. 911-7. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A., et al., The metacaspase Yca1 maintains proteostasis through multiple interactions with the ubiquitin system. Cell Discov, 2019. 5: p. 6. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.E., et al., Metacaspase Yca1 is required for clearance of insoluble protein aggregates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(30): p. 13348-53. [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.K. and G. Sherlock, Yca1 metacaspase: diverse functions determine how yeast live and let die. FEMS Yeast Res, 2023. 23. [CrossRef]

- Strich, R. and K.F. Cooper, The dual role of cyclin C connects stress regulated gene expression to mitochondrial dynamics. Microb Cell, 2014. 1(10): p. 318-324l role of cyclin C connects stress regulated gene expression to mitochondrial dynamics. Microb Cell, 2014. 1(10): p. 318-324. [CrossRef]

- Moll, U.M., et al., Transcription-independent pro-apoptotic functions of p53. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2005. 17(6): p. 631-6. [CrossRef]

- Karbowski, M., et al., Role of Bax and Bak in mitochondrial morphogenesis. Nature, 2006. 443(7112): p. 658-62. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D. and M. Ramsdale, Proteases and caspase-like activity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Soc Trans, 2011. 39(5): p. 1502-8. [CrossRef]

- Mentel, M., et al., Yeast Bax Inhibitor (Bxi1p/Ybh3p) Is Not Required for the Action of Bcl-2 Family Proteins on Cell Viability. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(15). [CrossRef]

- Qian, S., et al., The role of BCL-2 family proteins in regulating apoptosis and cancer therapy. Front Oncol, 2022. 12: p. 985363. [CrossRef]

- Pena-Blanco, A. and A.J. Garcia-Saez, Bax, Bak and beyond - mitochondrial performance in apoptosis. FEBS J, 2018. 285(3): p. 416-431J, 2018. 285(3): p. 416-431. [CrossRef]

- Jenner, A., et al., DRP1 interacts directly with BAX to induce its activation and apoptosis. EMBO J, 2022. 41(8): p. e108587.

- Sato, T., et al., Interactions among members of the Bcl-2 protein family analyzed with a yeast two-hybrid system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1994. 91(20): p. 9238-42. [CrossRef]

- Camougrand, N., et al., The product of the UTH1 gene, required for Bax-induced cell death in yeast, is involved in the response to rapamycin. Mol Microbiol, 2003. 47(2): p. 495-506. [CrossRef]

- Ritch, J.J., et al., The Saccharomyces SUN gene, UTH1, is involved in cell wall biogenesis. FEMS Yeast Res, 2010. 10(2): p. 168-76es, 2010. 10(2): p. 168-76.

- Eid, R., et al., Identification of human ferritin, heavy polypeptide 1 (FTH1) and yeast RGI1 (YER067W) as pro-survival sequences that counteract the effects of Bax and copper in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Exp Cell Res, 2016. 342(1): p. 52-61. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Yeast Bxi1/Ybh3 mediates conserved mitophagy and apoptosis in yeast and mammalian cells: convergence in Bcl-2 family. Biol Chem, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Buttner, S., et al., A yeast BH3-only protein mediates the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. EMBO J, 2011. 30(14): p. 2779-92.

- Manon, S., B. Chaudhuri, and M. Guerin, Release of cytochrome c and decrease of cytochrome c oxidase in Bax-expressing yeast cells, and prevention of these effects by coexpression of Bcl-xL. FEBS Lett, 1997. 415(1): p. 29-32. [CrossRef]

- Lhuissier, C., et al., Mitochondrial F0F1-ATP synthase governs the induction of mitochondrial fission. iScience, 2024. 27(5): p. 109808.

- Matsuyama, S., et al., The Mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase Proton Pump Is Required for Function of the Proapoptotic Protein Bax in Yeast and Mammalian Cells. Molecular Cell, 1998. 1(3): p. 327-336. [CrossRef]

- Légiot, A., et al., Mitochondria-Associated Membranes (MAMs) are involved in Bax mitochondrial localization and cytochrome c release. Microb Cell, 2019. 6(5): p. 257-266. [CrossRef]

- Toth, A., et al., Membrane-tethering of cytochrome c accelerates regulated cell death in yeast. Cell Death Dis, 2020. 11(9): p. 722. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P. and N. Kedersha, RNA granules: post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulators of gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2009. 10(6): p. 430-6 RNA granules: post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulators of gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2009. 10(6): p. 430-6. [CrossRef]

- Brangwynne, C.P., Phase transitions and size scaling of membrane-less organelles. J Cell Biol, 2013. 203(6): p. 875-81. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, U. and R. Parker, Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science, 2003. 300(5620): p. 805-8. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Z. Na, and S.A. Slavoff, P-Bodies: Composition, Properties, and Functions. Biochemistry, 2018. 57(17): p. 2424-2431.

- Wang, C., et al., Context-dependent deposition and regulation of mRNAs in P-bodies. eLife, 2018. 7: p. e29815 e29815. [CrossRef]

- Standart, N. and D. Weil, P-Bodies: Cytosolic Droplets for Coordinated mRNA Storage. Trends Genet, 2018. 34(8): p. 612-626. [CrossRef]

- Horvathova, I., et al., The Dynamics of mRNA Turnover Revealed by Single-Molecule Imaging in Single Cells. Mol Cell, 2017. 68(3): p. 615-625 e9. [CrossRef]

- Hubstenberger, A., et al., P-Body Purification Reveals the Condensation of Repressed mRNA Regulons. Mol Cell, 2017. 68(1): p. 144-157.e54-157.e5. [CrossRef]

- Kroschwald, S., et al., Promiscuous interactions and protein disaggregases determine the material state of stress-inducible RNP granules. eLife, 2015. 4: p. e06807. [CrossRef]

- Fromm, S.A., et al., The structural basis of Edc3- and Scd6-mediated activation of the Dcp1:Dcp2 mRNA decapping complex. Embo j, 2012. 31(2): p. 279-90. [CrossRef]

- Fromm, S.A., et al., In vitro reconstitution of a cellular phase-transition process that involves the mRNA decapping machinery. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2014. 53(28): p. 7354-9. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, H., et al., Structural analysis of the yeast Dhh1–Pat1 complex reveals how Dhh1 engages Pat1, Edc3 and RNA in mutually exclusive interactions. Nucleic Acids Research, 2013. 41(17): p. 8377-8390. [CrossRef]

- Schütz, S., E.R. Nöldeke, and R. Sprangers, A synergistic network of interactions promotes the formation of in vitro processing bodies and protects mRNA against decapping. Nucleic Acids Research, 2017. 45(11): p. 6911-6922.

- Decker, C.J., D. Teixeira, and R. Parker, Edc3p and a glutamine/asparagine-rich domain of Lsm4p function in processing body assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol, 2007. 179(3): p. 437-49. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N., et al., Intrinsically disordered proteins as crucial constituents of cellular aqueous two phase systems and coacervates. FEBS Lett, 2015. 589(1): p. 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Galea, C.A., et al., Regulation of cell division by intrinsically unstructured proteins: intrinsic flexibility, modularity, and signaling conduits. Biochemistry, 2008. 47(29): p. 7598-609. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.T., et al., Regulation of RNA granule dynamics by phosphorylation of serine-rich, intrinsically disordered proteins in C. elegans. Elife, 2014. 3: p. e04591. [CrossRef]

- Saito, M., et al., Acetylation of intrinsically disordered regions regulates phase separation. Nat Chem Biol, 2019. 15(1): p. 51-61.

- Isoda, T., et al., Atg45 is an autophagy receptor for glycogen, a non-preferred cargo of bulk autophagy in yeast. iScience, 2024. 27(6): p. 109810. [CrossRef]

- akeda, E., et al., Receptor-mediated cargo hitchhiking on bulk autophagy. Embo j, 2024. 43(15): p. 3116-3140. [CrossRef]

- Hanley, S.E. and K.F. Cooper, Sorting Nexins in Protein Homeostasis. Cells, 2020. 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Sanchez, S., et al., The endosomal protein sorting nexin 4 is a synaptic protein. Scientific Reports, 2020. 10(1): p. 18239. [CrossRef]

- Poppinga, J., et al., Endosomal sorting protein SNX4 limits synaptic vesicle docking and release. 2024, eLife Sciences Publications, Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.Y., et al., Sorting nexin-4 regulates β-amyloid production by modulating β-site-activating cleavage enzyme-1. Alzheimers Res Ther, 2017. 9(1): p. 4.

- Cullen, P.J. and F. Steinberg, To degrade or not to degrade: mechanisms and significance of endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2018. 19(11): p. 679-696. [CrossRef]

- Kotani, T., et al., A mechanism that ensures non-selective cytoplasm degradation by autophagy. Nat Commun, 2023. 14(1): p. 5815. [CrossRef]

- Nemec, A.A., et al., Autophagic clearance of proteasomes in yeast requires the conserved sorting nexin Snx4. J Biol Chem, 2017. 292(52): p. 21466-21480. [CrossRef]

- Makino, S., et al., Selectivity of mRNA degradation by autophagy in yeast. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 2316. [CrossRef]

- Shpilka, T., et al., Fatty acid synthase is preferentially degraded by autophagy upon nitrogen starvation in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2015. 112(5): p. 1434-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., et al., The Atg17-Atg31-Atg29 Complex Coordinates with Atg11 to Recruit the Vam7 SNARE and Mediate Autophagosome-Vacuole Fusion. Curr Biol, 2016. 26(2): p. 150-160. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H. and N.N. Noda, Biophysical characterization of Atg11, a scaffold protein essential for selective autophagy in yeast. FEBS Open Bio, 2018. 8(1): p. 110-116. [CrossRef]

- Lamark, T. and T. Johansen, Mechanisms of Selective Autophagy. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 2021. 37: p. 143-169. [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, Y., et al., Phase separation organizes the site of autophagosome formation. Nature, 2020. 578(7794): p. 301-305.

- Noda, N.N., Z. Wang, and H. Zhang, Liquid–liquid phase separation in autophagy. Journal of Cell Biology, 2020. 219(8). [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H., et al., The Intrinsically Disordered Protein Atg13 Mediates Supramolecular Assembly of Autophagy Initiation Complexes. Dev Cell, 2016. 38(1): p. 86-99.

- Rogov, V.V., et al., Atg8 family proteins, LIR/AIM motifs and other interaction modes. Autophagy Rep, 2023. 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Laxman, S. and B.P. Tu, Multiple TORC1-associated proteins regulate nitrogen starvation-dependent cellular differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One, 2011. 6(10): p. e26081. [CrossRef]

- Umekawa, M. and D.J. Klionsky, Ksp1 kinase regulates autophagy via the target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1) pathway. J Biol Chem, 2012. 287(20): p. 16300-10. [CrossRef]

- Huber, A., et al., Characterization of the rapamycin-sensitive phosphoproteome reveals that Sch9 is a central coordinator of protein synthesis. Genes Dev, 2009. 23(16): p. 1929-43. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.P., et al., Dynamic phosphoproteomics reveals TORC1-dependent regulation of yeast nucleotide and amino acid biosynthesis. Sci Signal, 2015. 8(374): p. rs4. [CrossRef]

- Soulard, A., et al., The rapamycin-sensitive phosphoproteome reveals that TOR controls protein kinase A toward some but not all substrates. Mol Biol Cell, 2010. 21(19): p. 3475-86. [CrossRef]

- Buchan, J.R., D. Muhlrad, and R. Parker, P bodies promote stress granule assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol, 2008. 183(3): p. 441-55.

- Mitchell, S.F., et al., Global analysis of yeast mRNPs. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2013. 20(1): p. 127-33. [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.C. and S.R. Wente, Functions of Gle1 are governed by two distinct modes of self-association. J Biol Chem, 2020. 295(49): p. 16813-16825. [CrossRef]

- Li, N., et al., Cyclin C is a haploinsufficient tumour suppressor. Nat Cell Biol, 2014. 16(11): p. 1080-91. [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.D., M. Oldenbroek, and T.G. Boyer, Mediator kinase module and human tumorigenesis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol, 2015. 50(5): p. 393-426. [CrossRef]

- Trakala, M. and M. Malumbres, Cyclin C surprises in tumour suppression. Nat Cell Biol, 2014. 16(11): p. 1031-3. [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, L., et al., Notch1 in Cancer Therapy: Possible Clinical Implications and Challenges. Mol Pharmacol, 2020. 98(5): p. 559-576. [CrossRef]

- Koch, U. and F. Radtke, Notch signaling in solid tumors. Curr Top Dev Biol, 2010. 92: p. 411-55. [CrossRef]

- Hyytinen, E.R., et al., Defining the region(s) of deletion at 6q16-q22 in human prostate cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer, 2002. 34(3): p. 306-12. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A., et al., Deletion of 6q16-q21 in human lymphoid malignancies: a mapping and deletion analysis. Cancer Res, 2000. 60(11): p. 2775-9.

- Sinclair, P.B., et al., A fluorescence in situ hybridization map of 6q deletions in acute lymphocytic leukemia: identification and analysis of a candidate tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Res, 2004. 64(12): p. 4089-98.

- Parmigiani, E., V. Taylor, and C. Giachino, Oncogenic and Tumor-Suppressive Functions of NOTCH Signaling in Glioma. Cells, 2020. 9(10). 9(10). [CrossRef]

- Choschzick, M., et al., NOTCH1 and PIK3CA mutation are related to HPV-associated vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract, 2023. 251: p. 154877. [CrossRef]

- Jezek, J., et al., Synergistic repression of thyroid hyperplasia by cyclin C and Pten. J Cell Sci, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Masson, G.R. and R.L. Williams, Structural Mechanisms of PTEN Regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2020. 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z., et al., Targeting Nrf2 to treat thyroid cancer. Biomed Pharmacother, 2024. 173: p. 116324. [CrossRef]

- Firestein, R., et al., CDK8 is a colorectal cancer oncogene that regulates beta-catenin activity. Nature, 2008. 455(7212): p. 547-51. [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.-Y., et al., The study of a novel CDK8 inhibitor E966-0530–45418 that inhibits prostate cancer metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2023. 162: p. 114667. [CrossRef]

- Roninson, I.B., et al., Identifying Cancers Impacted by CDK8/19. Cells, 2019. 8(8). [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.C., et al., Cyclin-dependent kinase 8 mediates chemotherapy-induced tumor-promoting paracrine activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109(34): p. 13799-804. [CrossRef]

- rägelmann, J., et al., Pan-Cancer Analysis of the Mediator Complex Transcriptome Identifies CDK19 and CDK8 as Therapeutic Targets in Advanced Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2017. 23(7): p. 1829-1840. [CrossRef]

- Menzl, I., A. Witalisz-Siepracka, and V. Sexl, CDK8-Novel Therapeutic Opportunities. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2019. 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A., et al., The histone variant macroH2A suppresses melanoma progression through regulation of CDK8. Nature, 2010. 468(7327): p. 1105-9. [CrossRef]

- Pelish, H.E., et al., Mediator kinase inhibition further activates super-enhancer-associated genes in AML. Nature, 2015. 526(7572): p. 273-276. [CrossRef]

- Ayala, Y.M., et al., Structural determinants of the cellular localization and shuttling of TDP-43. J Cell Sci, 2008. 121(Pt 22): p. 3778-85. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A., et al., Molecular Mechanisms of TDP-43 Misfolding and Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front Mol Neurosci, 2019. 12: p. 25. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J., et al., Mitochondrial fission and fusion: A dynamic role in aging and potential target for age-related disease. Mech Ageing Dev, 2020. 186: p. 111212. [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, B.M., et al., TDP-43 loss of function inhibits endosomal trafficking and alters trophic signaling in neurons. EMBO J, 2016. 35(21): p. 2350-2370. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, K.K., et al., TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) regulates stress granule dynamics via differential regulation of G3BP and TIA-1. Hum Mol Genet, 2011. 20(7): p. 1400-10. [CrossRef]

- Osaka, M., D. Ito, and N. Suzuki, Disturbance of proteasomal and autophagic protein degradation pathways by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutations in ubiquilin 2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2016. 472(2): p. 324-31. [CrossRef]

- Bose, J.K., C.C. Huang, and C.K. Shen, Regulation of autophagy by neuropathological protein TDP-43. J Biol Chem, 2011. 286(52): p. 44441-8. [CrossRef]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O., M.B. Gerke-Duncan, and R.M.D. Holsinger, Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants (Basel), 2023. 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H., et al., TDP-43 Triggers Mitochondrial DNA Release via mPTP to Activate cGAS/STING in ALS. Cell, 2020. 183(3): p. 636-649 e18. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., et al., The inhibition of TDP-43 mitochondrial localization blocks its neuronal toxicity. Nat Med, 2016. 22(8): p. 869-78. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.U., et al., Inhibition of Drp1/Fis1 interaction slows progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EMBO Mol Med, 2018. 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M., et al., Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases. Front Physiol, 2020. 11: p. 694. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L. and S.T. Ngo, Altered TDP-43 Structure and Function: Key Insights into Aberrant RNA, Mitochondrial, and Cellular and Systemic Metabolism in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Metabolites, 2022. 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Goel, P., et al., Neuronal cell death mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease: An insight. Front Mol Neurosci, 2022. 15: p. 937133. [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, V., A. Girdhar, and B.K. Patel, Role of CNC1 gene in TDP-43 aggregation-induced oxidative stress-mediated cell death in S. cerevisiae model of ALS. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res, 2021. 1868(6): p. 118993. [CrossRef]

- Riva, N., et al., Update on recent advances in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol, 2024. 271(7): p. 4693-4723. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, D.L., et al., Mutual Exclusivity of MED12/MED12L, MED13/13L, and CDK8/19Paralogs Revealed within the CDK-Mediator Kinase Module. Journal of Proteomics & Bioinformatics, 2013. 2013: p. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Bessenyei, B., et al., MED13L-related intellectual disability due to paternal germinal mosaicism. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud, 2022. 8(1)ud, 2022. 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Hamada, N., I. Iwamoto, and K.I. Nagata, MED13L and its disease-associated variants influence the dendritic development of cerebral cortical neurons in the mammalian brain. J Neurochem, 2023. 165(3): p. 334-347. [CrossRef]

- Siavrienė, E., et al., Molecular and Functional Characterisation of a Novel Intragenic 12q24.21 Deletion Resulting in MED13L Haploinsufficiency Syndrome. Medicina (Kaunas), 2023. 59(7). [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, R., et al., The MED13L Foundation strategic research plan: a roadmap to the future. Ther Adv Rare Dis, 2024. 5: p. 26330040241290252. [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.T., et al., Aberrant cyclin C nuclear release induces mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction in MED13L syndrome fibroblasts. iScience, 2022. 25(2): p. 103823. [CrossRef]

- Snijders Blok, L., et al., De novo mutations in MED13, a component of the Mediator complex, are associated with a novel neurodevelopmental disorder. Hum Genet, 2018ons in MED13, a component of the Mediator complex, are associated with a novel neurodevelopmental disorder. Hum Genet, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Polla, D.L., et al., De novo variants in MED12 cause X-linked syndromic neurodevelopmental disorders in 18 females. Genetics in Medicine, 2021. 23(4): p. 645-652. [CrossRef]

- Plassche, S.V. and A.P. Brouwer, MED12-Related (Neuro)Developmental Disorders: A Question of Causality. Genes (Basel), 2021. 12(5)).

- Luyties, O. and D.J. Taatjes, The Mediator kinase module: an interface between cell signaling and transcription. Trends Biochem Sci, 2022. 47(4): p. 314-327. [CrossRef]

- Calpena, E., et al., De Novo Missense Substitutions in the Gene Encoding CDK8, a Regulator of the Mediator Complex, Cause a Syndromic Developmental Disorder. Am J Hum Genet, 2019. 104(4): p. 709-720. [CrossRef]

- Uehara, T., et al., Pathogenesis of CDK8-associated disorder: two patients with novel CDK8 variants and in vitro and in vivo functional analyses of the variants. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 17575. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., et al., Analysis of MED12 Mutation in Multiple Uterine Leiomyomas in South Korean patients. Int J Med Sci, 2018. 15(2): p. 124-128. [CrossRef]

- Shamas-Din, A., et al., Mechanisms of action of Bcl-2 family proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2013. 5(4): p. a008714. [CrossRef]

- Gross, A. and S.G. Katz, Non-apoptotic functions of BCL-2 family proteins. Cell Death Differ, 2017. 24(8): p. 1348-1358. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).