1. Introduction

Stabilising the climate will require a change in mobility patterns to cleaner, less energy intensive forms of transport (Jaramillo et al. 2022, Climate Change Committee 2023). E-cargo bikes are a relatively new form of e-micromobility that offer a potential alternative to private car travel (Behrendt et al. 2024) not least because they permit the carrying of additional loads (whether shopping, children, tools, waste or other materials) which can be a key cause of car dependence (Mattioli et al., 2016).

To date, the role for such bikes has mostly been considered in relation to their potential to reduce van use in urban logistics. Studies include major European projects (Cyclelogistics Ahead c. 2017, Ploos van Amstel et al. 2018); modelling studies (Papaioannou et al. 2023, Hofman et al. 2017, Melo & Baptista 2017, Zhang et al. 2018); practical trials and guidance (Blazejewski et al. 2020, Clarke & Leonardi 2017, DfT 2018, Bicycle Association 2024, Verlinghieri 2023); examples of use by logistics companies (Post & Parcel 2019, Bodanski 2018); and various overview assessments (Caggiani et al. 2021, Malik et al. 2023, Cairns & Sloman 2019, Maes 2018, TfL 2023). Grant schemes have also been offered (EST 2022a & 2022b, Cairns & Sloman 2019).

However, “literature pertaining to e-cargo cycles in private transport is in general very limited” (Narayanan et al. 2022, p293), and has largely come from countries with more established cycling cultures, often based on sharing schemes in urban centres (Becker & Rudolf 2018, Hess & Schubert 2019, Marincek et al. 2024 , Bissel & Becker 2024). In the UK, e-cargo bike uptake is very low, with sales of only 4,000 e-cargo bikes reported in 2022, compared with 70,000 in France and 90,000 in Germany (Garadis, 2023).

Therefore, this research aims to address the research questions: what is the practical potential for e-cargo bikes as a personal transport mode in the UK? What are the key factors that will encourage or discourage take-up? And what are the potential impacts on car use and health? To answer these questions, the paper provides an overview of key findings from a mixed method research project called ‘ELEVATE’ (Philips et al., 2024), together with a discussion of the background, literature and project methodology.

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. E-Cargo Bikes and Their Private Use

E-cargo bikes are designed to carry loads including shopping, work equipment and passengers (particularly children). They vary in size and carrying capacity, but are larger and heavier than a conventional bike or e-bike. Compared to conventional bicycles, they often have a sturdier frame, smaller wheels and longer wheelbase to increase stability, and a heavy duty stand for easy parking. The most common types for personal use comprise ‘longtail’ (with an extended rear carrier) and ‘long john’ (with a large carrier at the front) bikes or trikes. A motor provides optional adjustable electrical assistance when the rider pedals. The e-cargo bikes considered in this project fall within the EAPC (electrically-assisted pedal cycle) regulations (DfT & DVSA, 2015), which limit the maximum continuously-rated power output of the motor to 250 Watts, and require electrical assistance to cut off when speed reaches 15.5mph. Although some of the technology that e-cargo bikes typically incorporate is complex, the bikes usually require little day-to-day maintenance, although longer-term servicing is often more challenging than for a conventional bicycle (Marks 2024).

As a theoretical assessment, the European CycleLogistics project identified ‘goods-related trips that could shift to bike or e-(cargo) bike’ as being those that involved the transport of ‘more than a handbag; less than 200kg’; that were less than 7km; and that were not part of a complex trip chain requiring a car. It estimated that, of personal motorised trips in cities, 77% of shopping trips, 50% of commuting trips and 44% of leisure trips could potentially shift to bike or cargo-bike (Wrighton & Reiter, 2016; Kruchten, 2013). Meanwhile, primary quantitative research on private use of e-cargo bikes includes:

A 2015 survey of 2,500 individuals owning cargo bikes in the US (Riggs 2016; Riggs & Schwatz 2018).

A 2016 survey of 931 users of a network of 46 cargo-bike-sharing operators in Germany and Austria (Becker & Rudolf 2018).

A 9-month randomised control trial in Norway in 2017/18, involving 36 parents, including 18 in a control group, and 18 who were variously equipped with - an e-bike with trailer (n = 6), a cargo (longtail) bike (n = 6) and a traditional bike with trailer (n = 6) (Bjørnarå et al. 2019).

A 2017 survey of 301 members and non-members of an e-cargo bike sharing scheme (‘Carvelo2go’) in Basel, Switzerland (Hess & Schubert 2019).

A 2022 survey of 955 cargo bike owners and users of cargo-bike sharing schemes in Switzerland (Marincek et al. 2024)

A 2022 survey of 2,386 users of cargo bike sharing schemes in Germany (Bissel & Becker 2024)

A recent overview paper by Carracedo & Mostofi (2022) synthesises some of the key themes from these, and other relevant studies (mostly European or US), whilst there is also a growing body of qualitative literature (Thomas 2021, Boterman 2020).

From their synthesis, Carracedo & Mostofi (2022) concluded that personal e-cargo bike users are more likely to be upper or middle class, male, in their late thirties or early forties, educated to degree level, existing cyclists, and in households with children and cars. Marincek et al. (2024) found similar characteristics, but noted there were significant proportions of cargo-bike-sharers who were under 30 and had relatively low incomes, whilst Bissel and Becker (2024) reported that over half of their cargo-bike-sharers were in households without cars.

Motivations for e-cargo bike use include lower total costs of ownership compared with car use; social aspects including physical and mental health benefits; and environmental concerns (Carracedo & Mostofi, 2022). Becker & Rudolf (2018) found more than 92% of their cargo-bike-sharers were ‘rather’ or ‘very concerned’ about climate change. Others have also highlighted the value of being able to cycle as a family (Thomas, 2021).

In terms of e-cargo bike use, Becker & Rudolf (2018) found 57% round trips were up to 10km, and 88% were up to 25km, with a relatively long mean distance of 14.6km (compared to typical unpowered cycle trips). Marincek et al. (2024) found that 91% of cargo bike owners were using them several times a week (including 55% who were using them every day, or almost every day), whilst frequencies of use were lower for cargo bike sharers.

Reported purposes for use vary. Marincek et al. (2024) propose four main types of user:

Cargo transporters – young, car-free adults using shared cargo bikes to transport bulky items;

Enthusiasts – who own a cargo bike as their main vehicle to stay active, transport children and replace car trips;

Multi-modals – who use cargo bikes as one travel option; and

Sustainable parents – pre-existing cyclists who acquire a cargo bike to transport children.

2.2. E-Cargo Bike Energy Use, Emissions and Impacts on Car Use

There is general agreement that e-cargo bikes are more energy efficient, and generate fewer emissions than cars or vans, both when in use, and from their creation and disposal. The European Cyclelogistics Ahead project states that “

an electric van can carry 10 times as much payload as a cargo bike, but it weighs 60 times as much. As a result, e-vans require motors delivering more than 80 kW, when a cargo bike does the job with one fourth of a kW (plus a tenth of a kW from the rider).” (Cyclelogistics Ahead c. 2017). A recent review paper (Narayanan & Antoniou 2022) concludes that, in use, the energy consumption of e-cargo cycles ranges from 9 to 18 Wh/km while an e-van may consume 200 Wh/km and an e-truck may use 800 Wh/km. A 2020 assessment of lifecycle emissions by the International Transport Forum indicates that, from manufacture, assembly and disposal, emissions for an e-bike (which may be a similar order of magnitude to those of an e-cargo bike) are less than 3% of those generated for a conventional car, or less than 2% of those generated for an e-car (Cazzola & Crist, 2020)

1. Emissions savings from using e-cargo bikes for last mile logistics compared to electric, hybrid or conventional vans are reported by various commentators (Temporelli et al. 2022, Cairns & Sloman 2019).

Key issues in the domestic context are whether e-cargo bikes do substitute for car or van travel or for more sustainable modes, and whether they modify destination choices, car ownership and travel habits more generally. In his study of US e-cargo bike owners, Riggs (2016) found that the proportion listing bike or cargo bike as their ‘primary’ mode of travel increased from 29% to 79% after purchase (with a 41%-point reduction in the proportion reporting that it was a car). 69% changed their travel behaviour, and, for these people, the number of car trips made reduced by an average of 1–2 trips per day. In their survey of shared cargo bike users, Becker & Rudolf (2018) found that 46% said that without the cargo bike, they would have made the journey by car. Bjørnarå et al. (2019) also reported a decrease in frequency of car driving for travelling to the workplace and the kindergarten in their trial (though not to the grocery store). Bissel & Becker (2024) found that car ownership was reduced by 7.4-18.1% for their cargo-bike-sharing users (with the range reflecting whether deferred purchases were included), and that cargo bikes were rated as superior to cars for various attributes. Together, these studies suggest that reductions in car use are likely to result from e-cargo bike use.

2.3. Health Implications of Use

Work on electrically-assisted bikes has shown that they usually require sufficient exertion to count as moderate or vigorous physical activity, and are therefore likely to provide health benefits for their riders (Simons et al. 2009. Gojanovic et al. 2011, Langford et al. 2017, Bourne et al. 2018). A recent briefing note (Bourne et al. 2022) includes references demonstrating that e-cycling can increase individual physical fitness by up to 10% in both inactive adults and those with chronic disease; that individuals typically ride e-bikes more frequently and for longer periods of time than conventional bicycles; and that the long-term benefits of active travel outweigh the risks of exposure to air pollution in high income countries. There is a lack of specific literature on the health impacts of (e-)cargo bike use, but several schemes involving commercial use of e-cargo bikes have anecdotally reported that their riders value the exercise they get from their jobs (Ploos van Amstel et al., 2018). Meanwhile, physical and mental health benefits are often mentioned as some of the main motivations for using e-cargo bikes in the literature on personal use (Carracedo & Mostofi 2022; Bissel & Becker 2024, Marincek et al. 2024).

This US and EU literature on e-cargo bike use and their energy, car replacement and health impacts, provides the key background for our methodology and findings.

3. Methodology

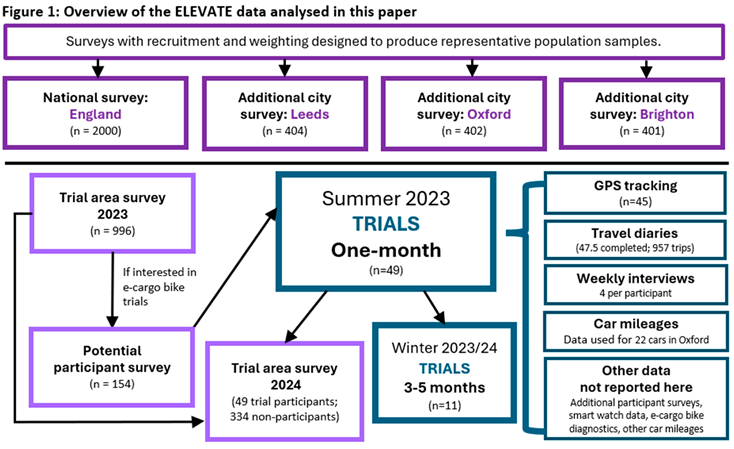

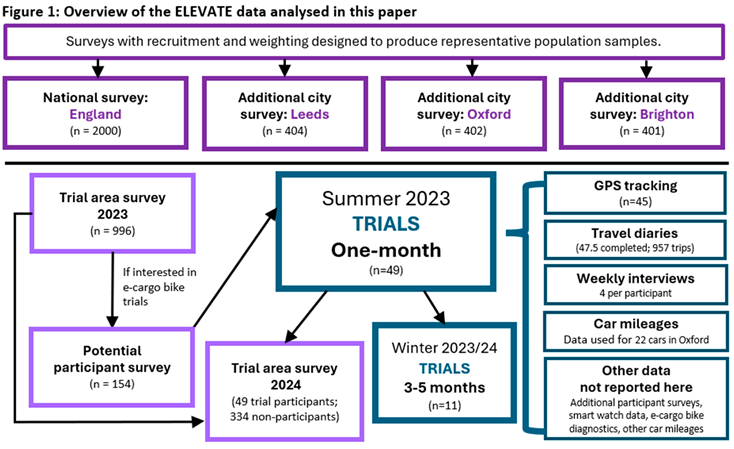

The methodology underlying this study is described in Philips et al. 2024), with information about the elements relevant to this paper’s analysis detailed below (see Figure 1).

3.1. Surveys

We conducted a series of surveys to investigate interest in e-cargo bikes and other micromobility modes, and to capture existing travel behaviour, opinions and personal characteristics of respondents.

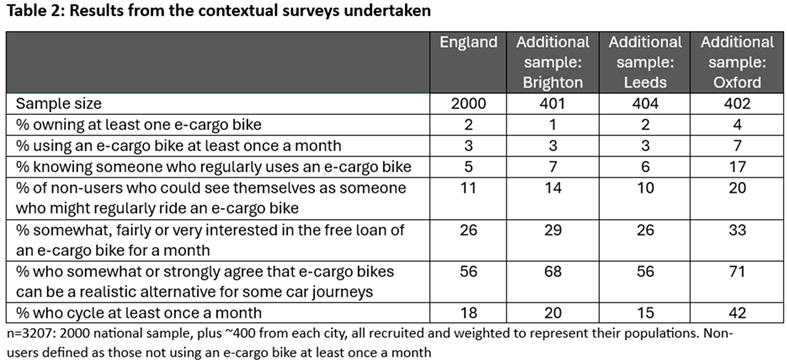

First, to provide context for the planned trials and to understand the current position of e-cargo bikes in the UK, YouGov Plc (one of the leading market research companies in the UK) were commissioned to undertake online surveys designed by the project team. Results were obtained for 2000 adults in England, together with an additional 400 adults in each of the three UK cities of Brighton, Oxford and Leeds (Table 2). Surveys were conducted between 31st May and 18th July 2023

2. Recruitment and weighting were used to ensure that each survey was representative of the relevant adult population, based on age, gender, ethnicity, social grade, and, in the English survey, region.

These representative surveys provided the context for ‘trial area’ surveys run by the project team, which took place between 24th April 2023 and the 30th September 2023

3. These surveys were promoted using a range of methods (including Twitter, Facebook and contact with community groups and schools), to reach as many people as possible. Whilst those completing the surveys were probably more interested in such modes than average, people were advised that we were “

keen to hear both positive and negative views” and, from comments, it is clear that some people responded because they wanted to express negative views.

996 responses were received from the trial areas (312 in Leeds; 422 in Brighton; 262 in Oxford). About half the respondents were somewhat, fairly or very interested in the free loan of an e-cargo bike for a month and 52% (515 people) expressed an interest in receiving further information about participating in our research project. The majority who did so were sent a link to a ‘potential participant’ survey

4, which 154 people completed. The drop-out between expressing interest and completing this survey partly occurred because the second survey highlighted that participants would be required to provide researchers with a significant volume of information, and, for insurance reasons, needed to have somewhere secure to store the bikes.

After the trials (described below), in September/October 2024, a follow-up survey was sent to the lead trial participants, and to all those who had completed the earlier trial area surveys and were happy to be contacted again but who had not become participants. In total, all trial participants and 334 (of 611) trial area survey non-participants replied.

3.2. Trials

Across the three cities of Brighton, Oxford and Leeds, 49 households were lent e-cargo bikes

5 for one month each during the summer of 2023, together with cycle training and other support.

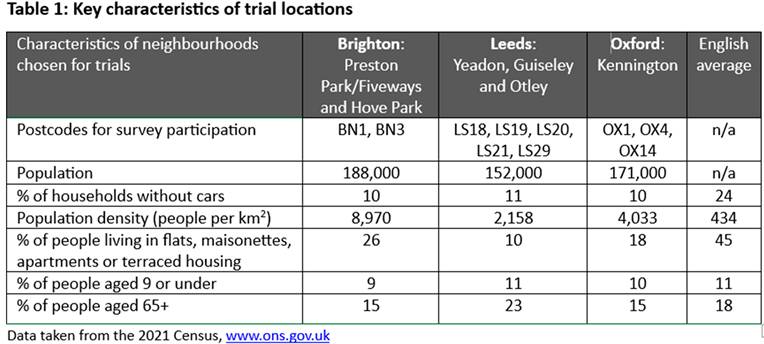

The trials were focused in three different types of suburban areas with high levels of car ownership, but viable trip lengths for cycle use, in order to assess the potential to reduce car use (Table 1).

Specifically, the project was focused on:

Preston Park and Hove Park - high density inner suburbs of the coastal city of Brighton.

Yeadon, Guiseley and Otley - satellite towns on the edge of the northern conurbation of Leeds.

Kennington - a village on the outskirts of the southern city of Oxford.

Insurance requirements meant that areas needed to have houses with somewhere for secure e-cargo bike storage. For survey purposes, areas were defined by postcode geographies, which were more familiar to the general public than Census zones or council ward administrative geographies. The geodemographic characteristics of the areas were assessed using secondary data sources, and site selection was discussed with stakeholders from the areas.

The 49 trial households were selected from the 154 people who completed the ‘potential participant’ survey. Selection was largely based on practical considerations – including storage arrangements, availability in relevant time windows and clarity about desire to participate. During their one-month loan, households completed a travel diary with details of every round trip made using their e-cargo bike, including an estimate of distance, trip purpose, and how they would have otherwise travelled. Diary data were completed for 47.5 of the loans, with information for 957 trips

6 (Azzouz 2024). In addition, the e-cargo bikes were fitted with GPS trackers

7, with full data available for 45 loans. For both data sources, data cleaning and gap filling was required, and neither fully captured all travel

8.

In addition to surveys, households completed four interviews during the course of their participation. Interviews were conducted using semi-structured interview guides, with subsequent transcription, coding and analysis using NVivo software. Supplementary data was also gathered via household car mileage readings; smart watch (or equivalent) supplied by some participants about their health; and uploads of comments, pictures and video of their experience.

Between October 2023 and April 2024, 11 of the original 49 households who expressed particular interest in a longer loan were lent an e-cargo bike for a further 3-6 months and completed additional interviews and surveys.

4. Findings from the National and City-Level Surveys

4.1. Existing Levels of E-Cargo Bike Ownership and Use in England

The nationally-representative online survey of 2,000 adults showed that e-cargo bikes are a relatively niche transport mode in England. Overall, 3% of the respondents were using an e-cargo bike at least once a month; 2% were part of households that owned an e-cargo bike; and 6% had ridden an e-cargo bike at least once. 5% stated that they knew someone personally who regularly uses an e-cargo bike and 6% of respondents said that they were aware of opportunities to hire an e-cargo bike within walking distance of their home.

4.2. Interest in, and Perceptions of, E-Cargo Bikes

Of those who had not used an e-cargo bike in the last month, 11% of respondents somewhat or strongly agreed that they could see themselves as being the kind of person who might regularly ride an e-cargo bike. 21% also somewhat or strongly agreed that people who were important to them would approve of them doing so; and 42% somewhat or strongly agreed that they would find it easy to ride an e-cargo bike if they wanted to. From the full sample, 5% of respondents said that their household was somewhat or very likely to buy an e-cargo bike (or another e-cargo bike) in the next 12 months, whilst 26% of respondents were ‘somewhat’, ‘fairly’ or ‘very interested’ in the free loan of an e-cargo bike for a month. Interest in e-cargo bikes, therefore, suggests that there may be potential for considerably higher usage than at present.

All respondents were asked about their perceptions of e-cargo bikes: 66% somewhat or strongly agreed that they are better for the environment than driving (whilst 9% somewhat or strongly disagreed); 56% somewhat or strongly agreed that they can be a realistic alternative for some car journeys (whilst 20% somewhat or strongly disagreed), and 41% somewhat or strongly agreed that the Government should do more to support their use (whilst 19% somewhat or strongly disagreed).

4.3. Variation in Findings by Location

Table 2 indicates that these national findings varied in Leeds, Brighton and Oxford, given their differing contexts. In particular, high levels of cycling in Oxford were accompanied by higher levels of e-cargo bike ownership and use. Figures for Leeds were similar to those for England as a whole, whilst Brighton represented an interim case between Oxford and Leeds.

4.4. Current Use of E-Cargo Bikes and Associated Characteristics

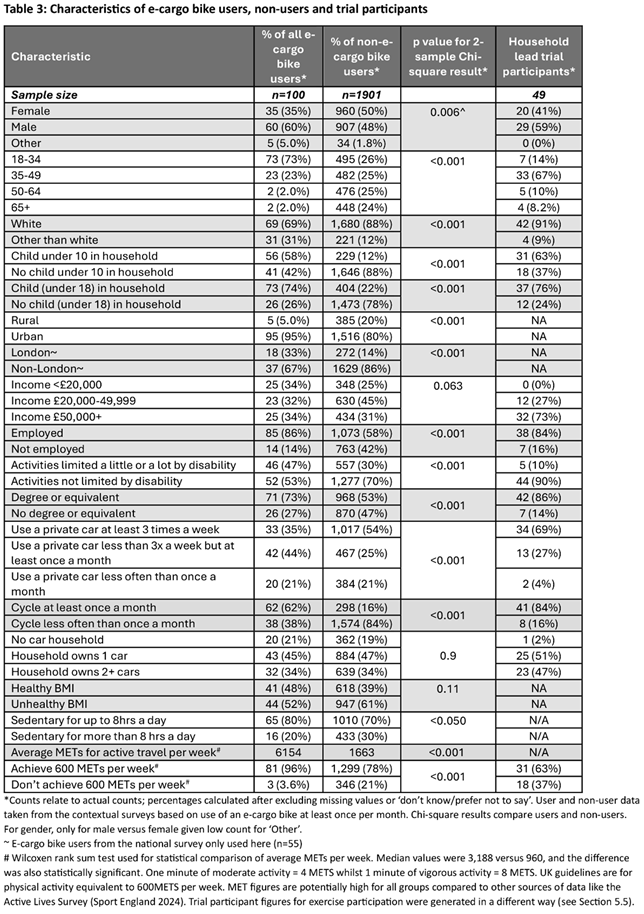

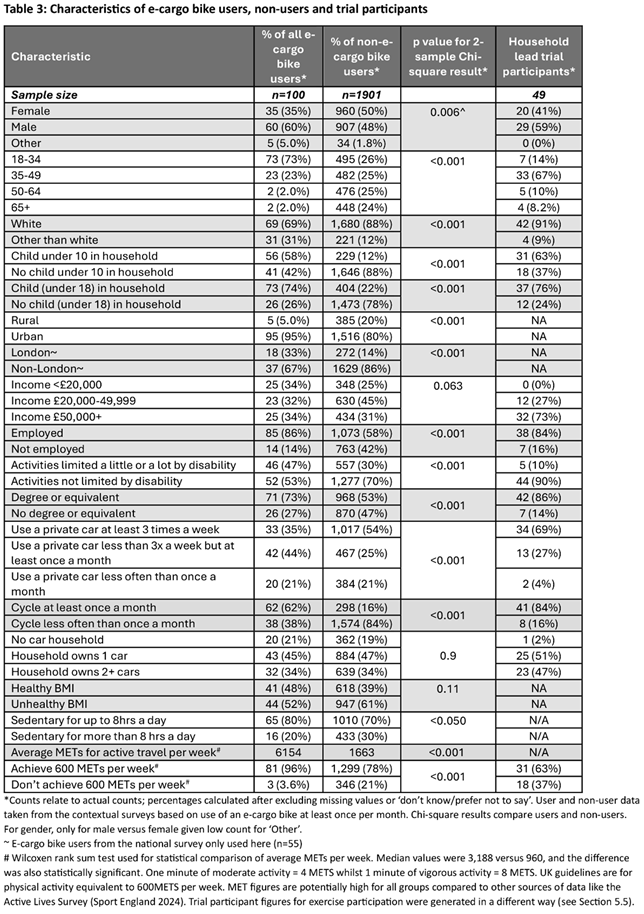

The survey data were also analysed to compare e-cargo bike users and non-users. There were 55 people using an e-cargo bike at least once a month in the English national survey, 12 in Leeds, 22 in Oxford and 11 in Brighton. Consequently, a pooled sample of 100 ‘users’ was created, and compared to the data from the main national sample about those who did not use an e-cargo bike at least once a month (n=1901)

9, see Table 3.

The results provide some interesting corroboration of the literature, and some contradictions. E-cargo bike users emerged as usually being young (with a high proportion aged 18-34), often having children in their household and living in urban areas (with an over-representation of e-cargo bike users based in London). There was a surprisingly high representation from ethnic groups other than white and of people with disabilities. The gender bias was similar to that for general cycling

10. Users were more likely to have a degree and to be employed than non-users, though were from a spread of income groups.

Unsurprisingly, users were more likely to be cycling at least once a month than non-users. There was no significant difference in car ownership levels, but there was a statistically significant difference in frequent car use, with e-cargo bike users being less likely to use a private car at least 3 times a week.

Data on weight, height and the World Health Organisation’s Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) questions

11 were used to provide health characteristics including BMI and energy expenditure from key physical activities. A significantly higher proportion of e-cargo bike users were meeting UK physical activity guidelines (compared with non-users) and they were undertaking, on average, more minutes of active travel. Differences in the shares with a healthy BMI, or who were sedentary for up to 8 hours a day, were in keeping with these findings, but were not statistically significant (at the 95% confidence level).

People in households

owning an e-cargo bike (with a pooled sample of 64 people

12) were also considered. Most of the distinctive characteristics of the owners were similar to those of users. The greatest differences related to income – where only 22% of owners were in households with an income of £50,000+ (compared to 34% of users, and 31% of non-owners) and were less likely to be in employment than users (78% compared to 86%). These findings contradict the narrative that e-cargo bikes are a toy for the wealthy.

5. Findings from One-Month Summer Trials in Brighton, Oxford and Leeds

5.1. Participant Characteristics

Lead trial participants (i.e., those who signed up for the trial) were more likely to be cyclists, with children in their households , educated to degree level and in employment (compared to the national non-user sample), see Table 3. Not least due to the neighbourhoods chosen , car ownership and use were very high, most participants were white, two-thirds were aged 35-49 and households were relatively wealthy.

Although more lead participants were male, other household members could also sign up to ride the bikes and of the 56 people who signed up to ride the bikes in total, 34 (60%) were female. Although many previous studies have found a male bias, the potential appeal of e-cargo bikes to women has also been highlighted– for example, 43% of e-cargo bike sharers in Bissel & Becker (2024) survey were female; Riggs and Schwartz (2018) reported that women were more likely to use e-cargo bikes for trips with children than men; and Marincek et al. (2024) noted that, although two-thirds of their survey respondents were male, 79% of cargo bike owners shared them with other family members.

5.2. E-Cargo Bike Usage by Trial Participants

All trial households used the e-cargo bikes at least once during their one-month loan. According to the travel diaries, the number of days of use per loan ranged from 2 to 29

13, with a mean of 13 days per household (equivalent to about 3 days per week per household). Participants made between 2 and 50 trips during their loan period, averaging 20 trips per loan, or 5 trips per week

14. Trip length ranged from less than 1km to as high as 76km, though the majority (98%) were under 25km, with a mean trip length of 7.8km (9.9 in Leeds, 7.0 in Brighton, and 6.7 in Oxford), a relatively high average for cycle trips, as discussed in Cass (2024b) and in keeping with the findings of Becker & Rudolf (2018), although this may partly relate to how participants defined trips.

Participants travelled an average of 38km (travel diary figure) to 42km (GPS figure) per week. In total, the GPS trackers for 45 loans indicated a total distance travelled during the trial of 8,137km. Travel diaries recorded a slightly lower distance - 7,468kms - though some trips were known to be missing. Together, these imply participants cycled in the order of at least 8,000km during the trials.

5.3. Purposes of E-Cargo Bike Usage

Whilst our study does not allow for corroboration of the e-cargo user types proposed by Marincek et al. (2024), it was the case that some people borrowing e-cargo bikes replaced a regular trip (such as a nursery run), whilst others used the e-cargo bikes on a more ad hoc basis.

In the potential participant survey (n=154), respondents were asked what they thought they might use an e-cargo bike for (with multiple responses possible). In all three cities, shopping was most frequently chosen. Carrying children was the second most chosen, with the figure being lower in Leeds, which is arguably the most car dependent location, and where social media comments often focused on the safety issues of using e-cargo bikes in traffic. Meanwhile, the proportion of respondents choosing commuting was higher in Oxford, where cycling is a more mainstream activity than the other two locations. Other activities indicated included exercise; carrying tools or materials for work; travel during work; trips to the tip, recycling centre or charity shops; leisure trips, including to the gym, beach or park; transporting a dog; considering training to be a delivery driver; servicing fountains; and working as a nanny.

During the trials, 54% trips and 49% distance cycled involved more than one person on the bike – i.e., the cyclist transported other people, usually children (with these figures being highest in Oxford – 62% trips/53% distance – and lowest in Leeds – 44% trips/42% distance). There were 9 households (19%) who did not make any trips with passengers.

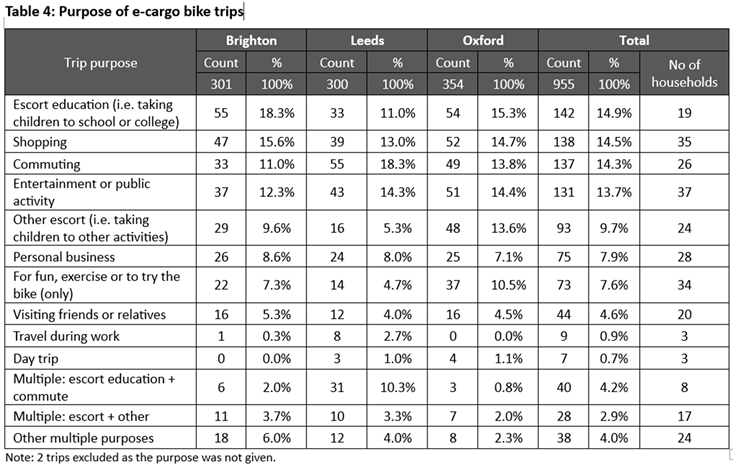

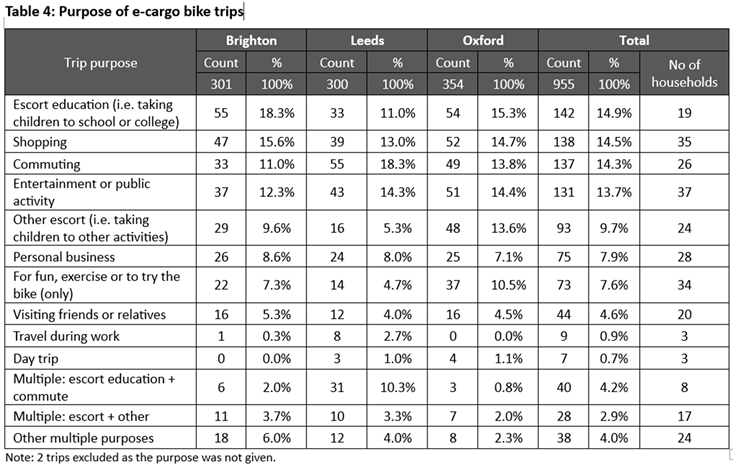

In terms of trip purpose, escorting children (either to school, nursery or other activities), shopping, commuting and entertainment (including going to a child’s activity such as the park, swimming or playgroup) accounted for the majority of trips, either individually or combined (see Table 4). 11% of trips were made for multiple purposes – with the most common combination being commute + school/nursery trip.

Whilst the majority of households (34 out of 48) had made trips only for fun or exercise or to try out the bike, these accounted for less than 8% of all trips made, and the majority were practical journeys enabling participants to reach destinations (although many people indicated fun, exercise or trying the bike was also a motivation when choosing to use the bike for these trips). Concerns about routes, security, and parking at unfamiliar destinations emerged as barriers to use. Some participants reported using the e-cargo bikes less than expected because they had unrealistic expectations - for example, they hoped to do some relaxed leisure trips on the e-cargo bike but found themselves too short of time.

Meanwhile, participants indicated that about 10% of trips would not otherwise have been made without the e-cargo bike, and that the bikes had enabled new trips, often facilitating travel ‘as a family’. Some felt it had made a substantial difference to their opportunities, with one describing how ”it’s allowed us to do more things outdoors than… we would have done previously and to go to places that we wouldn’t have gone to together”, (male_35-39_Oxford).

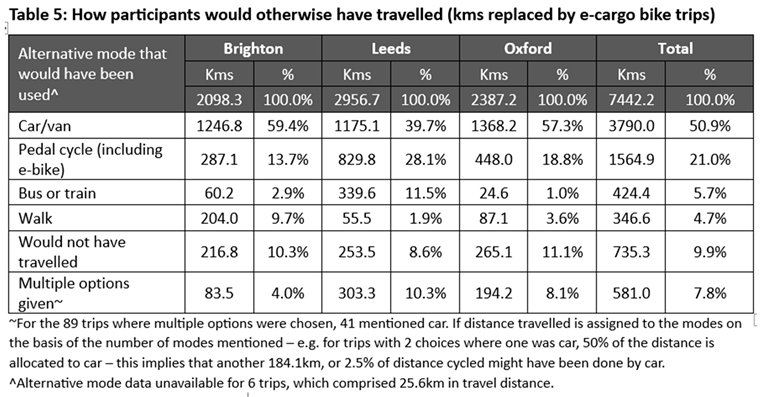

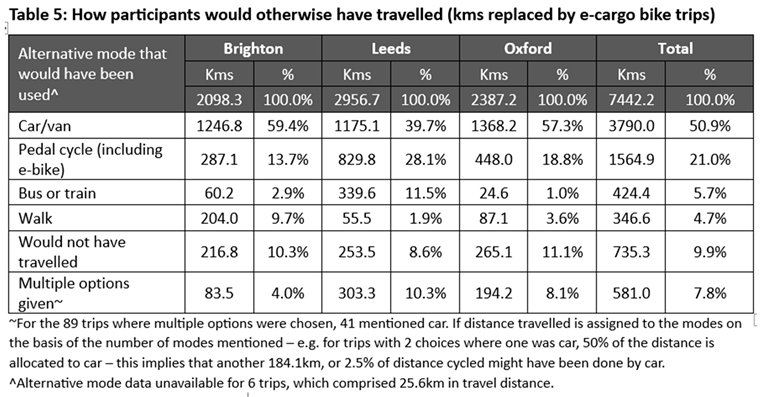

5.4. Impacts of Borrowing An E-Cargo Bike on Car Travel

98% of the trial households owned at least 1 car, including 40% who owned 2 cars and 8% who owned three or more cars, meaning that there was considerable scope for reducing car use. Travel diary data about how participants would otherwise have made e-cargo bike journeys (see Table 5) suggest that over half of all distance travelled by e-cargo bike (51-53%) would otherwise have been made by car, equivalent to 18-19km per household per week

15.

Participants were also asked to record the mileages for all cars in their households on a weekly basis. A reasonable dataset was collected for 14 of the Oxford households, with odometer readings for 22 cars. Comparing mileage in the week before the trial, with mileage during the trial suggested an average reduction of 22.5km per household per week, which is relatively similar to the value from the travel diaries. However, there was considerable heterogeneity in car use trajectories underlying the average figures, not least because one long car journey in a week considerably alters average values, and because many of these households made different journeys each week.

The interview data provided corroboratory evidence that the e-cargo bikes did affect car use – though again highlighting variability. Some saw e-cargo bikes as a mode that would be useful from time to time. For example, one participant anticipated that it would “revolutionise my approach to short journeys, which, right now, is driving a diesel estate that’s forever hauled 2 miles away, multiple times a week”, (female_40-44_Leeds). After the trial, others reported that it had been transformative, and might enable them to forego a (second) household car. For example, one participant said it had “massively reduced our mileage… I’ve barely driven these last 4 weeks at all… I think I’ve been averaging around 20, 23 miles a week.. so that’s… 100 miles of car travel that I haven’t done”, (male_30-34_Oxford).

5.5. Impacts of E-Cargo Bike Trial Use on Health

When attracting trial participants, one consideration was whether only highly fit, existing cyclists would be interested (which would mean the health benefits of encouraging greater take-up of e-cargo bikes would be limited). However, of the 515 local survey respondents who expressed interest in receiving further information about our trial, 34% were cycling less than once a month, and 42% self-reported that they were doing less than 2.5 hours of physical activity per week (the nationally recommended guideline)

16. Of the 49 lead trial participants, before the trial, 8 were cycling less than once a month and 18 were doing less than the nationally recommended amount of physical activity.

In the interviews, trial participants often spontaneously mentioned the health benefits of using the e-cargo bike, both physical and mental. At least one keen cyclist commented that their fitness hadn’t suffered from using the e-cargo bike as they had chosen to cycle more. Another, with two young children, explained how “it isn’t always possible to do a regular exercise, because you’re running around after children” and appreciated “being able to just go on like a 15 minute cycle ride, and choose whether I’m going to put the extra effort in, or just stick it in turbo and let it go”, (female_30-34_Brighton). Another participant particularly valued the social opportunities enabled, highlighting that using the e-cargo bike has meant “we spend time together, we interact together, we have fun, we laugh together, that helps with our bond, helps socially, we meet other people doing it” and that “definitely has improved our mental health”, (male_35-39_Oxford).

5.6. Motivations

Some of our trial participants were keen to be involved because they had already considered buying an e-cargo bike and welcomed the opportunity to see whether it suited them. Many valued the initial help from the research team with adapting the bikes to their particular needs, and the training provided on using and locking the bikes. Most participants had particular journeys, involving shopping, children or other purposes, that they were keen to try.

Environmental motivations were also important. In our national survey, 77% of all English adults indicated being ‘very’, ‘fairly’ or ‘somewhat’ concerned about climate change

17 and 65% of drivers indicated that they ‘try to minimize their car use’

18. In contrast, all trial participants defined themselves as very, fairly or somewhat concerned about climate change, and 95% of those driving were trying to minimize their car use. Environmental issues were also discussed in the interviews. For example, one participant commented that “

anything that you can do to tackle the climate emergency helps to alleviate some sort of anxiety and stress. ..And I think this is a really, really good example”, (male_35-39_Brighton). Potential health benefits were also mentioned, together with the opportunities to cycle as a family, both for social and instructional reasons, with one parent arguing:

“It just normalises it for them… that it’s acceptable to go out on a bike and use that as a mode of transport”, (female_40-44_Leeds)

5.7. Experiences of Use

Although others have reported that e-cargo bike users can generate negative reactions (Boterman, 2020), this was not commonly reported by trial participants (even though, particularly in Oxford, general animosity between drivers and cyclists was mentioned). Instead, people largely reported positive experiences. For example, one father felt transporting his children by e-cargo bike increased the tolerance of other road users:

“Riding on this, I feel people do actually give you a lot of space compared to when I’m in lycra on my road bike … when somebody sees that it’s a bloke stood upright with two kids in the front clearly doing a chore rather than a pleasure ride, I think people do give you more space and patience”

(male_40-44_Leeds)

This was often compounded by high levels of interest in the bikes, with one parent reporting:

“…people wanting to come and talk to me, children wanting to get in it. We’ve constantly got visitors in the bike, parents at nursery wanting to come and ask questions about it… riding past pubs, people cheering for me, which is totally random, but that’s happened maybe three or four times, but people stopping and smiling and waving... drivers passing me and smiling, generally, lots of cyclists, of course, giving me the cycle nod, pulling up alongside us and having conversations with [my daughter]” (female_40-44_Leeds)

Parents also enjoyed being able to interact with their children whilst cycling. For example, some described how they could talk to their children about the rules of the road and what the child would need to be aware of when they cycled independently, as well as being able to socialise with them. Children’s attitudes to use were often a key determinant of whether bikes got used – some were endlessly keen, whilst others couldn’t see the attraction or refused to use them. The ability to travel with other family members also meant that more trip chaining was possible – for example, dropping a child off before shopping – a benefit commonly associated with car use.

Participants also reported riding the e-cargo bike as if it were a car (in terms of keeping to the middle of a lane), a tendency encouraged by the cycle trainer, and that this was also positive:

“You feel safer because it’s a larger road presence, it’s a more dominant road presence, it’s much smoother and better controlled, it’s smoother off the line, it keeps up, you know, it doesn’t get under, in the way of traffic so much.”

(male_45-49_Brighton)

Glachant et al. (2024) consider some of these positive experiences, as part of a wider discussion about e-cargo bike citizenship, and whether it may challenge existing perceptions of cycling as individualistic and abnormal.

Meanwhile, compared to the positive riding experiences, many trial participants found storing the bike at home awkward if they did not have an obvious space. In some cases, a household car was described as being ‘in the way’ of getting the bike out. Finding parking away from home was also a challenge, as one participant described:

“You can’t just leave it outside a shop because it’s going to take up the whole pavement, so you do need to find the designated bike parking spots. Those bike parking spots aren’t always big enough - well, they are big enough, but you feel like you’re taking over. But it’s way easier to park something like that in Otley than it is to park a car… ”

(male_40-44_Leeds)

Several smaller female participants found the particular bike borrowed was too heavy and cumbersome or were unable to lower the saddle sufficiently, leading them to conclude that it was not for them, and at least one participant also felt uncomfortable with the image they projected. Other issues mentioned included usual cycling concerns such as theft, traffic, weather and poor cycle infrastructure.

6. Findings from Longer Term Winter Trials and Surveys

A subset of the 1-month trial participants (n = 11) were lent bikes for a further period of 3-6 months between October 2023 and April 2024. Evidence from these winter trials was that the e-cargo bikes were usually still used (despite the change in weather), and several households reported that being able to try more than one type of e-cargo bike, or being able to trial an e-cargo bike for a longer period of time, were important for enabling their household to make a decision about whether they would buy one.

By Autumn 2024, 10 of the 49 trial households (20%) had bought e-cargo bikes (with one buying both an electric and an unpowered cargo bike) and the number of households owning at least one e-bike had increased by 5. In total, 18 households (37%) were estimated to have increased their adult cycle ownership (taking into account ownership of e-bikes, e-cargo bikes and conventional pedal cycles

19). In addition, at least one household had got rid of a second car. 18 households (including 9 of those whose household adult cycle ownership had already increased) indicated that their household was very or somewhat likely to buy an e-cargo bike or e-bike in the next 12 months. 34 lead participants (69%) said that an e-cargo bike seemed ‘somewhat’ or ‘much’ better value for money since participating in the trial (with 2 saying somewhat or much worse value) and 32 (65%) said that participating in the trial had made their household ‘somewhat’ or ‘much’ more likely to buy an e-cargo bike (with 6 saying somewhat or much less likely). 33 (67%) somewhat or strongly agreed that cost is “a very important factor in whether my household will buy an e-bike or e-cargo bike in the next 12 months”.

This tendency for the opportunity to trial micromobility modes affecting purchase has been found in other studies. For example, Becker & Rudolf (2018) found that 35% of cargo bike sharers were planning to buy one in the medium to longer term. In the recent evaluation of the UK’s national e-cycle programme, 7% of those loaned an e-bike for 1 month had acquired one by the end of the loan period and many were keener to buy one in the future than before the loan (Steer, 2024).

7. Wider Context

The research has also highlighted wider structural issues that affect e-cargo bike use and cycling more generally.

The first issue is theft. In the national survey, 65% of non e-cargo bike owners somewhat or strongly agreed that “if I owned an e-cargo bike, I would worry about it getting stolen (at home or when out)”. During the trial, one of the e-cargo bikes was stolen and taken to London, and the differing attitude of the police forces involved highlighted the challenges faced by owners. Security measures used during the trial included GPS trackers, providing ‘Sold Secure Gold’ bike locks and most bikes also featured a front wheel lock. In Brighton, additional locks with an alarm were fitted to brake discs. It is clear that there is more scope for innovation, and for police support with recovering stolen bikes.

The second issue is the misrepresentation of what are classed as e-bikes in the UK. This seems to be more relevant in the UK than in the EU. Frequently, press reports refer to e-bikes when talking about motorised 2 wheelers which do not meet the legal definition of an e-bike (DfT & DVSA 2015). This creates a narrative that e-bikes are a fire risk, are ridden dangerously on roads above the 15mph speed limit, and are associated with criminal behaviour. UK industry representative ‘The Bicycle Association’ contests this view and has collated evidence that fire risk is very low amongst reputable e-bike suppliers (BA, 2023; The Electric Bike Alliance 2024; Eland 2025) but refers to this narrative as an ‘existential threat’ to e-bike and e-cargo bike uptake (Sutton 2024). During our trials, we observed the practical implications of this narrative: one participant was not allowed to park his e-cargo bike within the work car park due to concerns about fire, and Leeds University banned the storage and charging of bicycle batteries in any university building.

Third, as with all cycling, and reported in many previous studies (e.g., Narayanan & Antoniou, 2022; Marincek et al. 2024; Carracedo & Mostofi 2022; Becker & Rudolf 2018, Hess & Schubert 2019), the need for safer cycling conditions and better infrastructure was highlighted. Trial participants identified particular issues, such as the need for larger cycle parking, wider cycle lanes, and challenges with access routes blocked with anti-motorcycle barriers. At least some of these issues will also affect those wheeling double buggies, or using mobility scooters, or other forms of ‘wide’ micromobility. Cass (2024a) consider a range of issues, including speed limits and geofencing, as mechanisms that might facilitate the inclusion of e-cargo bikes within existing mobility regimes. Meanwhile, Darking et al. (2024) consider how the experience of trials like this one can affect the perceptions of decision makers and local communities in terms of thinking about innovative transport modes like e-cargo bikes.

8. Conclusions

Cycling offers one way to address key societal challenges, such as physical inactivity, local air pollution and climate change (Brand et al. 2021, Brand et al. 2022, Bourne et al. 2022). E-cargo bikes can help to address one of the drawbacks of cycling – namely the ability to carry goods and passengers – but there has been limited research on their domestic use, or their potential in suburban areas, particularly in the UK.

This paper aims to address this research gap, by providing empirical evidence on the personal use of e-cargo bikes in three suburban UK settings. Insights have been gained from multiple data sources, including a range of surveys, and a series of real world trials, which included short and long term loans, backed with cycle training and other support.

In terms of the potential of e-cargo bikes as a personal transport mode, our national survey highlighted that while only 2% of households in England own an e-cargo bike and 3% of English adults were using one at least once a month, 11% of non-users see themselves as someone who might regularly ride one, and 26% of all respondents were interested in trying one out. The figures were higher in Oxford, which already has a strong culture of cycling. We were readily able to recruit participants to trial e-cargo bikes, and most of our 49 households reported positive experiences, with relatively frequent use by those who found the bikes convenient, usage for a variety of purposes and, on average, relatively long average cycle trips (based on participant trip definition). By Autumn 2024, 10 trial households had bought e-cargo bikes. This indicates, then, that in the right conditions, e-cargo bikes do offer an attractive and practical personal transport mode whose take-up could be increased.

However, for a few trial participants, the e-cargo bike they were loaned was too big and heavy. Other issues discouraging take-up included awkward storage at home, difficulties parking at end destinations, purchase price, theft, battery safety and lack of infrastructure. A key implication for policy and industry, then, is that although there is scope for e-cargo bike take-up to be considerably greater than at present, there are some key barriers to be addressed.

The research also provided insights into the potential impacts on car use and health. Household usage varied considerably, but, in total, participants collectively cycled about 8,000km, averaging 38-42km per week, and indicated that over half of the distance travelled would otherwise have been made by car. Trial participants often highlighted mental or physical activity benefits from use during interviews. In the national and city surveys, compared to non-users, existing e-cargo bike users had typical levels of car ownership, but lower levels of frequent car use, and were more likely to be undertaking the recommended amount of weekly physical activity. These findings chime with literature from other countries which suggest use of e-cargo bikes can lead to reductions in car use and/or health benefits (see work by Riggs 2016, Becker & Rudolf 208, Bjørnarå et al. 2019, Carrecedo & Mostofi 2022, Bissel & Becker 2024 and Marincek et al. 2024). Further work examining whether the mode substitution and health potential reported to date could be replicated at a larger scale would be valuable.

Many of the motivations and experiences that our trial participants reported were similar to those reported for e-cargo bike users in other countries, reinforcing the contention that there is nothing inherently different about people’s reaction to them in the UK. However, at the same time, it is clear that a favourable policy climate for cycling is key to addressing barriers such as theft and infrastructure, and that the misrepresentation of e-bikes in the UK represents a specific issue for UK policy makers to address. The availability of longer-term data in this study, and the dramatic increase in cycle ownership by households involved in our trials, is one of the unique features of the work, and potentially shows the value that trials can play in enabling people to try out unfamiliar and relatively expensive cycle innovations.

The work has various limitations. For example, due to resource constraints, the nationally-representative survey only covered England and not the UK. Trials were only undertaken in three locations, and people self-selected into the trials. Hence the data from the trials reflects information about those initially interested in e-cargo bikes, and is in no way claimed to be ‘representative’ of all those living in suburban areas; rather it enables an assessment of whether there is any practical potential for e-cargo bikes in these types of neighbourhoods.

In brief, the study demonstrated that for some people, at certain life stages, e-cargo bikes do represent a realistic and desirable form of mobility; they have the potential to reduce car use and emissions for shorter journeys, with associated health benefits; whilst policy measures are needed to address key barriers to use and to ensure that they achieve their full potential as part of the necessary transition to more sustainable mobility patterns.

Funding

This work has been funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council/UKRI, grant reference: UKRI EP/S030700/1.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to the funders and to Pirjo Johnson (Leeds University project administration); Gavin Ellison from YouGov; SmartSurvey; national and local stakeholders; and to all those involved in the surveys and trials reported, including the bike shops, cycle trainers, local residents and trial participants.

Declaration of interests: All authors have previously done a range of research work on cycling and micromobility, which has been funded by a variety of sources, including some pro-cycling organisations. The work has only ever been funded to provide objective insights and advice. External funders have had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Azzouz, L. (2024) E-cargo bikes and modal shift: Tales from three UK cities. Universities Transport Studies Group conference, June 10th, Huddersfield.

- Becker, S., & Rudolf, C. (2018) Exploring the potential of free cargo-bikesharing for sustainable mobility. GAIA - Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 27, 156–164. [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, F., Heinen, E., Brand, C., Cairns, S., Anable, J., & Azzouz, L. Conceptualizing Micromobility. Preprints 2022, 2022090386 https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202209.0386/v1.

- Bicycle Association. (2023) Bicycle Association statement on e-bike battery fire safety.

- Bicycle Association. (2024) Cargo bikes & cycle logistics. Webpage, accessed 30/3/24.

- Bissel M & Becker S (2024) Can cargo bikes compete with cars? Cargo bike sharing users rate cargo bikes superior on most motives – Especially if they reduced car ownership. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour (101), pp218-235. [CrossRef]

- Bjørnarå, H., Berntsen, S., J. te Velde, S., Fyhri, A., Deforche, B., Andersen, L., Bere, E. (2019) From cars to bikes – The effect of an intervention providing access to different bike types: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 14(7): e0219304. [CrossRef]

- Blazejewski, L, Sherriff, G and Davies, N (2020) Delivering The Last Mile: Scoping the Potential for E-cargo Bikes.

- Brand C, Dons E, Anaya-Boig E, Avila-Palencia I, Clark A, de Nazelle A, Gascon M, Gaupp-Berghausen M, Gerike R, Götschi T, Iacorossi F, Kahlmeier S, Laeremans M, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Orjuela JB, Racioppi F, Raser E, Rojas-Rueda D, Standaert A, Stigell E, Sulikova S, Wegener S & Int Panis L (2021) The climate change mitigation effects of daily active travel in cities, Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment (93). [CrossRef]

- Brand C, Dekker H-J & Behrendt F (2022) Chapter Eleven - Cycling, climate change and air pollution,.

- In Advances in Transport Policy and Planning (10) pp235-264. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanski R (2017) Cycle logistics solutions in the 2017 sustainability study of the German parcel and express association (BIEK) Presentation at the 2017 ECLF conference, Vienna, March.

- Boterman, W.R., 2020. Carrying class and gender: cargo bikes as symbolic markers of egalitarian gender roles of urban middle classes in Dutch inner cities. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 21, 245–264. [CrossRef]

- Bourne JE, Sauchelli S, Perry R, Page A, Leary, S., England C, et al. (2018) Health benefits of electrically-assisted cycling: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Bourne J, Levine JG, Landeg-Cox C & Bartington SE (2022). Environmental and Health Impacts of E-cycling, TRANSITION Clean Air Network Policy Briefing Note No.4, pp1-7, Birmingham, UK. [CrossRef]

- Caggiani L, Colovic A, Prencipe LP & Ottomanelli M (2021) A green logistics solution for last-mile deliveries considering e-vans and e-cargo bikes, Transportation Research Procedia (52), pp 75-82. [CrossRef]

- Cairns S & Sloman L (2019) Potential for e-cargo bikes to reduce congestion and pollution from vans in cities. Report for the Bicycle Association.

- Carracedo D & Mostofi H (2022) Electric cargo bikes in urban areas: A new mobility option for private transportation, Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives (16). [CrossRef]

- Cass N (2024a) E-cargo bikes: how does a bike-car hybrid negotiate velomobility and automobility geographies and infrastructures in the UK? Geographies of vélomobility I: Planning, Mobilities and Infrastructure, Nordic Geographers meeting, Copenhagen University, 25/6/24.

- Cass N (2024b) What is an e-cargo bikeable trip? ECEEE 2024, Paris.

- Cazzola, P. and Crist, P. (2020). Good to Go? Assessing the Environmental Performance of New Mobility. Paris. Available at: https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/environmental-performance-new-mobility.pdf.

- Clarke S and Leonardi J (2017) Final Report : Multi- carrier consolidation - Central London trial. GLA, London.

- Climate Change Committee (2023) Progress in reducing UK emissions 2023 Report to Parliament Climate Change Committee, London. ISBN 978-1-5286-4092-3.

- Cyclelogistics Ahead project (undated, c2017) CycleLogistics – Moving Europe Forward. Final EU project report.

- Darking M, Behrendt F, Marks N and Philips I (2024) Engaged micro-mobility research as pragmatist mobility innovation strategy: experimenting with household e-cargo bike use in 3 UK cities. European Association for the Study of Science and technology (EASST) 2024 quadrennial meeeting. Amsterdam, Netherlands, 16/7/24.

- De Sejournet A & Glachant C (2024) E-cargo bikes for a household shift to sustainable mobility? 17th NECTAR conference. Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium, 04/07/2024.

- Department for Transport (2018) The Last Mile: A Call for Evidence on the opportunities available to deliver goods more sustainably, report on Sainsburys trial on p13.

- DfT and DVSA (2015) Electrically assisted pedal cycles (EAPCs) in Great Britain: information sheet - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk).

- Eland P (2025) BA complains to BBC about Panorama e-bike misrepresentation. Press release, Bicycle Association.

- Energy Saving Trust (2022a) eCargo Bike Grant Fund 2021/2022 Local authority scheme evaluation Report for DfT.

- Energy Saving Trust (2022b) eCargo Bike Grant Fund 2021/22 National scheme evaluation Report for DfT.

- Garidis, S., 2023. Bicycle Association UK ebike market results, e-bike summit 05 September 2023. Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. https://www.ebikesummit.org/agenda.

- Glachant C, Cass N, Marks N and Azzouz L (2024) Between or beyond bicycles and cars: Navigating E-Cargo Bike Citizenship in the Transition to Sustainable Mobilities. Paper submitted to Geoforum.

- Gojanovic B, Welker J, Iglesias K, Daucourt C & Gremion G (2011) Electric bicycles as a new active transportation modality to promote health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 43(11) pp2204–10. [CrossRef]

- Hess A & Schuber I (2019) Functional perceptions, barriers, and demographics concerning e-cargo bike-sharing in Switzerland. Transp. Res. Part D 71, 153–168. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman et al. (2017) A Simulation Tool To Assess The Integration Of Cargo Bikes Into An Urban Distribution System. The 5th International Workshop on Simulation for Energy, Sustainable Development & Environment, Barcelona, Spain.

- Jaramillo, P., S. Kahn Ribeiro, P.; Newman, S.; Dhar, O.E.; Diemuodeke, T.; Kajino, D.S.; Lee, S.B.; Nugroho, X.; Ou, A. Hammer Strømman, J. Whitehead, 2022: Transport. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R.; Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Kruchten Z (2013) Shift to Cycling: CycleLogistics Baseline Study Reports on Impressive Potential European Federation Cyclists website, accessed 11/05/24.

- Langford BC, Cherry CR, Bassett DR, Fitzhugh EC & Dhakal N (2017) Comparing physical activity of pedal-assist electric bikes with walking and conventional bicycles. J Transp Health (6) pp463–73. [CrossRef]

- London Fire Brigade (2022) House Fire - Walthamstow. Safety warning 4/7/22, accessed 11/6/24.

- Maes J (2018) The potential of cargo bicycle transport as a sustainable solution for urban logistics Velo-City June 12-15 2018, Rio.

- Malik FA, Egan R, Dowling CM & Caulfield B (2023) Factors influencing e-cargo bike mode choice for small businesses, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (178). [CrossRef]

- Marinek D, Rérat P & Lurkin V (2024) Cargo bikes for personal transport: A user segmentation based on motivations for use. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 18 (9). [CrossRef]

- Marks N (2024) “Blue: ANTics of an e-cargo bike.” International Conference at the Centre for Mobilities and Urban Studies (C-MUS), Aalborg, Denmark, August 22-23, 2024.

- Mattioli G, Jillian Anable J & Vrotsou K (2016) Car dependent practices: Findings from a sequence pattern mining study of UK time use data, Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice (89), pp56-72. [CrossRef]

- Melo & Baptista (2017) Evaluating the impacts of using cargo cycles on urban logistics: integrating traffic, environmental and operational boundaries. European Transportation Research Review 9: 30. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan S & Antoniou C (2022) Electric cargo cycles - A comprehensive review, Transport Policy 116, pp 278-303. [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou E, Iliopoulou C & Kepaptsoglou K (2023) Last-Mile Logistics Network Design under E-Cargo Bikes. Future Transportation 3(2) pp403-416. [CrossRef]

- Philips I, Anable J & Chatterton T (2022) E-bikes and their capability to reduce car CO2 emissions, Transport Policy (116) pp11-23. [CrossRef]

- Philips, I., Azzouz, L., de Séjournet, A., Anable, J., Behrendt, F., Cairns, S., Cass, N., Darking, M., Glachant, C., Heinen, E., Marks, N., Nelson, T., & Brand, C. (2024). Domestic Use of E-Cargo Bikes and Other E-Micromobility: Protocol for a Multi-Centre, Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(12), 1690. [CrossRef]

- Post and Parcel (11/3/19) DPD to transform London. Website accessed 11/05/24. https://postandparcel.info/103277/news/infrastructure/dpd-to-transform-delivery-in-london/.

- Ploos van Amstel W et al. (2018) City logistics: light and electric. LEFV-LOGIC: Research on light electric freight vehicles. Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences. http://www.citylogistics.info/research/city-logistics-light-and-electric/.

- Riggs W & Schwartz J (2018) The impact of cargo bikes on the travel patterns of women. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 6 (1) (2018), pp. 95-110.

- Riggs W (2016) Cargo bikes as a growth area for bicycle vs. auto trips: exploring the potential for mode substitution behavior. Transportation Research F 43, pp48-55.

- Simons M, Van Es E & Hendriksen I (2009) Electrically assisted cycling: a new mode for meeting physical activity guidelines? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 41(11), pp2097–102. [CrossRef]

- Sport England (2024) Active Lives Adult Survey November 2022-23 Report. Sportengland.org.

- Sutton M (2024) Call for Government to up pace on dangerous kit imports or face ‘existential’ risk to cycling industry. Cycling Electric article reporting on a session of the All Party Parliamentary Group for Cycling and Walking.

- Temporelli A, Brambilla PC, Brivio E & Girardi P (2022) Last Mile Logistics Life Cycle Assessment: A Comparative Analysis from Diesel Van to E-Cargo Bike. Energies. 2022; 15(20):7817. [CrossRef]

- The Electric Bike Alliance (2024) Be E-bike Positive Campaign website.

- Thomas, A. (2021). Electric bicycles and cargo bikes—Tools for parents to keep on biking in auto-centric communities? Findings from a US metropolitan area. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 16(7), 637–646. [CrossRef]

- Transport for London (2023) Cargo bike action plan Transport for London.

- Verlinghieri E (2023) Supporting cargo bike managers to scale up the sector. Cargo-bikes-follow-up-policy-briefing-note. University of Westminster, London.

- Wrighton, S., Reiter, K., 2016. CycleLogistics – Moving Europe forward! Transp. Res. Procedia 12, 950–958. [CrossRef]

- Zhang et al. 2018: Simulation-based Assessment of Cargo Bicycle and Pick-up Point in Urban Parcel Delivery. Procedia Computer Science 130, pp18-257. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Figures for vehicle and battery manufacture, assembly and disposal (including fluids), plus delivery to point of purchase, comprise 11,339,015 gCO2-eq for an electric car; 6,496,825 for a conventional car; and 168,510 gCO2-eq for a privately-owned electrically-assisted bike. |

| 2 |

All questions had a ‘don’t know / prefer not to say’ response option. All questions asking about agreement or disagreement with opinion statements also had a ‘neither agree nor disagree’ option. |

| 3 |

The majority of responses were received towards the beginning of this period. |

| 4 |

Some people did not provide a valid email address, and a few respondents were not sent a link towards the end of the survey period, since it would not have been possible for them to become a trial participant. |

| 5 |

The bikes used were: 4 Reise & Muller Multitinker bikes in Brighton; 4 Gazelle Maki Load bikes in Oxford; and 2 Raleigh stride bikes, a Tern GSD bike, a Talio bike and a Benno Boost bike in Leeds. |

| 6 |

Information was missing about riders and passengers (10 trips), trip purpose (2 trips) and alternative mode (6 trips). These trips have been excluded from relevant calculations. |

| 7 |

PowUnity BikeTrax trackers were used, with data accessed via their API. R code was used for access and data analysis. https://powunity.com/en

|

| 8 |

For the travel diaries, it was unclear whether all trips were logged, and there were gaps in the records (some of which were subsequently filled by cross-referencing with interview or GPS data). In one case, the travel diary was not completed, and in another, it was only completed for 2 of 4 weeks (i.e. 0.5 of the loan period). For the GPS data, data were cleaned to remove travel used to reposition the bikes between households and adjustment was needed to allow for the fact that in areas where signal quality was low, and GPS points were relatively widely spaced, the GPS only recorded a ‘straight line’ distance. Further cleaning is planned to address trip definitions, as trip definitions used by the trackers may have included stops at traffic lights and other temporary pauses, as trip start/ends, so trip based information reported here is from the travel diaries. |

| 9 |

People who did not complete the question about how often they use an e-cargo bike, or who indicated ‘Don’t know/prefer not to say’ as their response, were excluded from the samples. Weighted data have not been used in this section, given analysis suggesting that use of weights in this context might skew results. |

| 10 |

NTS table NTSQ05005a indicates that 37% of males and 24% of females aged 5+ cycle at least once a month, implying that perhaps 60% are male; data accessed on the Ad-hoc National Travel Survey analysis page. |

| 11 |

Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ) (who.int) |

| 12 |

Our assumption is that e-cargo bike users whose households did not own an e-bike were either borrowing an e-cargo bike, or using one for work. |

| 13 |

Loan periods ranged from 18-43 days, with the majority between 27 and 29 days (including bike handover days). |

| 14 |

Participants varied in whether they recorded trips as one-way or round trips. |

| 15 |

Here, data are averaged across the sample, rather than using the mean of household averages (used to calculate average weekly mileages). |

| 16 |

This was assessed using a simple question, rather than the WHO GPAQ questions, due to the need to minimize questionnaire length. |

| 17 |

Respondents were asked: ‘On a scale of 1-5, how concerned are you about climate change, sometimes referred to as global warming?’ with answer options being 5 - very concerned; 4- fairly concerned; 3-somewhat concerned; 2-Not very concerned; 1-Not at all concerned. Don’t know/prefer not to say. Percentages given here are calculated to include the ‘don’t know/prefer not to say’ option. |

| 18 |

This was asked as part of a wider question, with two options for non-drivers, two options for drivers ‘I drive and am not interested in reducing my car use’ and ‘I drive but try to minimise my car use’ and a ‘Don’t know/None of the above/Prefer not to say’. Percentages given here are for the balance of the two car driver options. |

| 19 |

Where respondents had chosen ‘3 or more’ for any of these categories, the number was conservatively assumed to be three. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).