1. Introduction

A Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) refers to damage affecting the bundle of nerves and nerve fibers that transmit signals between the brain and the rest of the body. The spinal cord, an extension of the central nervous system (CNS), begins at the medulla oblongata and ends in the lower back at the conus medullaris, followed by the cauda equina. The brain serves as the command center, while the spinal cord facilitates communication between the brain and the body. These messages control muscle movement, sensation, and essential autonomic functions like breathing and heart rate (Witiw & Fehlings, 2015).

SCI may result from direct trauma to the spinal cord or damage to surrounding tissues and vertebrae. These injuries can lead to temporary or permanent impairment of sensation, movement, and bodily functions below the injury site (Ditunno et al., 1994). Symptoms vary based on injury location and severity. Higher spinal cord injuries may result in tetraplegia, affecting all four limbs, while lower injuries can cause paraplegia. Paralysis may occur immediately (primary damage) or progressively due to secondary damage from bleeding, swelling, or cell death. The extent of nerve fiber damage influences recovery potential, ranging from minor impairment to complete loss of function. Symptoms include numbness, pain, weakness, difficulty walking, and loss of bladder or bowel control. Breathing difficulties and altered sexual function may also occur (Rupp et al., 2021).

1.1. Pathophysiology and Diagnosis of SCI

Following an SCI, key pathological changes occur that impact recovery. The initial phase includes vascular disruption, leading to hypoperfusion and ischemia, which can cause neuronal cell death. Inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and apoptotic pathways further contribute to tissue damage. Neurogenic shock, marked by hypotension and bradycardia, may occur due to autonomic dysfunction. Over time, tissue loss results in cavity formation at the injury site, complicating recovery (Anjum et al., 2020).

Diagnosing SCI requires a combination of clinical assessments and imaging techniques. Emergency evaluation includes testing movement, sensation and breathing, responsiveness, and muscle strength. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to detect spinal trauma, herniated discs, vascular abnormalities, and ligament damage (Freund et al., 2019). Computerized tomography (CT) scans identify fractures, bleeding, and spinal stenosis (Goldberg & Kershah, 2010). X-rays provide rapid insights into vertebral misalignment or fractures, assisting in immediate decision-making (Pinchi et al., 2019).

1.2. Classification & Assessment of SCI

SCI classification is based on anatomical and functional criteria. The spine is divided into five sections: Cervical (C1-C7), Thoracic (T1-T12), Lumbar (L1-L5), Sacral (S1-S5), and Coccyx (Cx3-Cx5). The neurological level of injury is the lowest spinal segment with intact motor and sensory function. Injuries are classified as complete or incomplete based on preserved neurological function below the injury level (Nas et al., 2015). A complete injury results in total loss of motor and sensory function, whereas an incomplete injury allows some level of function and sensation (S. C. Kirshblum et al., 2011; S. Kirshblum & Waring, 2014; Rupp et al., 2021). Neurological function alone does not define disability, as motor and sensory impairments also influence clinical outcomes (Krawetz & Nance, 1996; Rekand et al., 2012).

Standardized assessment tools evaluate SCI severity and recovery potential. The American Spinal Injuries Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS) is the most widely used tool for assessing SCI severity. It classifies injuries from Grade A, (complete injury with no function) to Grade E (normal function) based on motor and sensory assessments (Waters et al., 2000). ASIA evaluates key muscles and dermatomes on both sides of the body, providing a standardized score to determine injury severity and recovery potential. The Lower Extremity Motor Score (LEMS), a component of ASIA, helps predict walking ability, with a score of 30 or higher indicating a good chance of regaining mobility (Waters et al., 1994).

1.3. Emergency and Acute Treatment of SCI

At the scene of an accident where a spinal cord injury (SCI) is suspected, emergency responders prioritize immobilization to prevent further damage. A rigid collar is placed around the neck, and the patient is carefully positioned on a backboard (Eli et al., 2021). If necessary, sedatives may be administered to minimize movement, and a breathing tube may be inserted in cases of respiratory distress. Upon arrival at a trauma center, immediate interventions include spinal realignment using a rigid brace or mechanical force. Surgery is often required to remove fractured vertebrae, bone fragments, or herniated discs compressing the spinal cord. Early spinal decompression surgery has been shown to improve functional recovery.

SCI often leads to complications requiring targeted treatment (Sterner & Sterner, 2023). Respiratory issues are common, with one-third of SCI patients needing temporary or permanent breathing assistance. Injuries at the C1-C4 levels can impair diaphragm function, requiring mechanical ventilation. Pneumonia is a leading cause of death in SCI patients, particularly those on ventilators. Circulatory complications, such as unstable blood pressure, blood clots, and abnormal heart rhythms, necessitate the use of anticoagulants and compression stockings. SCI can also lead to muscle tone changes, including spasticity and atrophy. Autonomic dysreflexia, a life-threatening condition in individuals with upper spinal injuries, can cause sudden hypertension, headaches, sweating, and vision disturbances. Positioning the patient upright can help reduce blood pressure. Other complications include pressure ulcers, neurogenic pain, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and sexual health issues, all of which require specialized treatment. Additionally, SCI often has a psychological impact, with many individuals experiencing depression. Therapy and medication can help manage these mental health challenges (Safdarian et al., 2023).

1.4. Rehabilitation and Prognosis in SCI

Rehabilitation programs aim to restore independence and improve quality of life. These programs integrate physical therapies, skill-building activities, and psychological support. A multidisciplinary team consisting of rehabilitation specialists, therapists, nurses, and psychologists tailors treatment to each patient’s needs (Hu et al., 2023). Assistive devices such as braces, wheelchairs, electronic stimulators, and neural prosthetics can enhance mobility.

Predicting recovery from SCI remains challenging. Clinical assessments alone often fall short in forecasting outcomes (Cadotte & Fehlings, 2014). Neurophysiological techniques, including somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs), nerve conduction studies, and motor evoked potentials (MEPs), provide objective measures of neural function (Hubli et al., 2019). These techniques distinguish nerve damage types and offer prognostic value, particularly in clinical trials. SSEPs are especially useful in evaluating sensory recovery by assessing the conduction of sensory signals along the spinal cord. Intact or improved SSEP responses suggest better prognosis, while absent or diminished responses indicate severe injury (Nardone et al., 2016). SSEPs are valuable for assessing injury level, guiding treatment plans, and predicting long-term sensory and motor outcomes.

1.5. Electrophysiology and Artificial Intelligence in SCI

Electrophysiology plays a critical role in SCI diagnosis, classification, and prognosis (Korupolu et al., 2019). Among the widely used evoked potential (EP) techniques, SSEPs, MEPs, and nerve conduction studies assess neural pathway integrity (Curt & Ellaway, 2012; Kakulas, 2004). EPs provide objective insights into neurological dysfunction, even in cases where clinical evaluations are challenging due to patient unresponsiveness (Fustes et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). Studies show that SSEPs correlate strongly with SCI outcomes, including walking ability, hand function, and bladder control (Singh et al., 2020). Combining clinical assessments (e.g., ASIA scores) with electrophysiological tests enhances diagnostic accuracy and informs treatment strategies.

Recent technological advancements have introduced Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) into SCI research. AI leverages large datasets to enhance disease prediction, classification, and treatment planning (Lawal & Kwon, 2021). ML algorithms utilize statistical techniques like regression analysis and Bayesian inference to analyze patient data, improving diagnostic precision. Neural networks have been successfully applied in SCI prognosis, medical imaging, and treatment optimization (Hongmei et al., 2006). By integrating AI-driven models with neurophysiological assessments, researchers aim to predict SCI progression and optimize rehabilitation strategies, leading to better patient outcomes.

3. Results

As main approach was used the Ensemble Learning, a machine learning technique, that combines multiple models—such as regression models, neural networks, and decision trees—to enhance predictive accuracy. This approach, sometimes referred to as committee-based learning, integrates several individual models to achieve better results than a single model alone (Zhou, 2012). Research has validated the effectiveness of ensemble learning in machine learning and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Each machine learning model is influenced by various factors, including training data, hyperparameters, and other parameters, all of which impact the total error of the resulting model. Consequently, even when using the same training algorithm, different models may emerge, each characterized by distinct levels of bias, variance, and irreducible error. By merging multiple diverse models, ensemble methods can minimize the overall error while preserving the unique strengths and complexities of each model, such as a lower bias for specific data subsets. Studies indicate that ensembles with greater diversity among their component models generally yield more accurate predictions. Furthermore, ensemble learning can effectively mitigate overfitting without significantly increasing model bias. Research suggests that ensembles composed of diverse, under-regularized models (which tend to overfit their training data) can outperform individual regularized models (Zhou, 2019). Additionally, ensemble techniques can address challenges related to high-dimensional data, offering an alternative to traditional dimensionality reduction approaches.

In this study, ensemble algorithms were employed like Vote, which integrates three models: Decision Trees (J48), Artificial Neural Networks (Multilayer Perceptron), and Bayes (Naïve Bayes). Additionally, the Random Forest algorithm was utilized. All models were implemented using the Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis (WEKA) platform (Holmes et al., 1994). WEKA is a widely used machine learning software suite, developed in Java at the University of Waikato, New Zealand. Distributed as open-source software under the GNU General Public License, WEKA version 3.7.8 provides an extensive range of visualization tools and machine learning algorithms for data analysis and predictive modeling. It features graphical user interfaces that enhance accessibility, as well as data preprocessing functions implemented in C. Moreover, it employs a Make file-based system for conducting machine learning experiments. WEKA integrates various artificial intelligence techniques and statistical methods, supporting core data mining processes such as preprocessing, classification, regression, clustering, visualization, and rule selection. The platform operates on the principle that data is presented in a structured format, where each instance consists of a defined set of attributes, whether numerical, nominal, or other supported types. Many of WEKA’s standard machine learning algorithms generate decision trees for classification tasks.

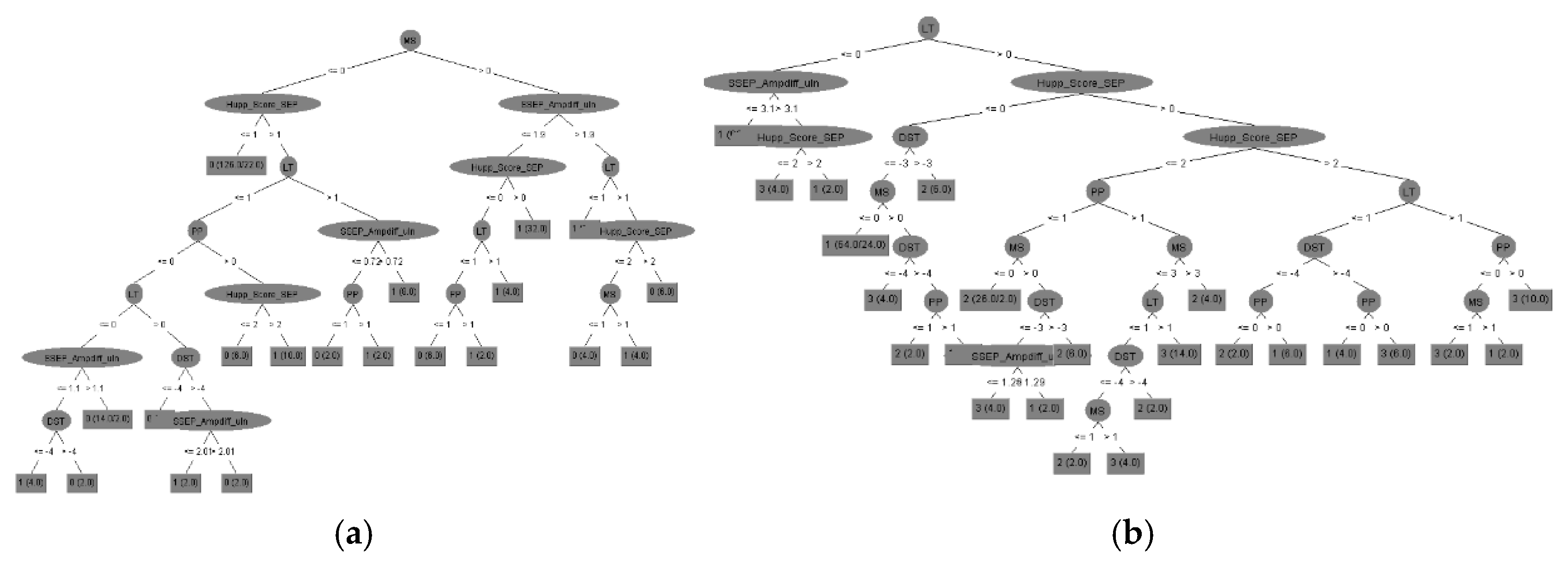

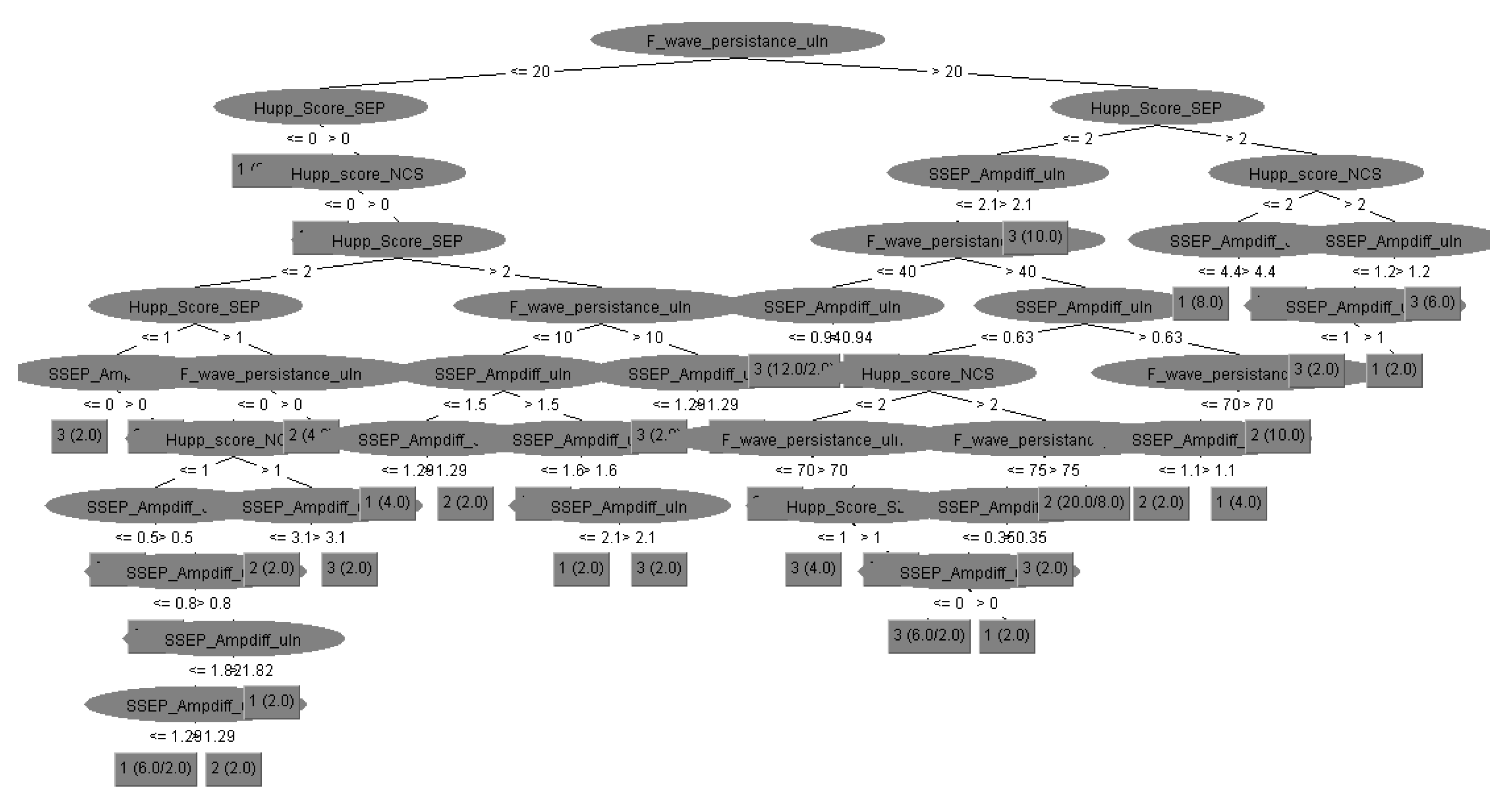

The first machine learning approach applied in this study was Decision Trees using the J48 algorithm. Decision trees facilitate the extraction of valuable insights, enabling the development of predictive models. A decision tree is structured like a flowchart, systematically dividing data into branches without information loss while guiding a series of decisions based on input data. It serves as a hierarchical sorting mechanism, predicting outcomes based on sequential decision-making steps. The tree construction process follows a structured methodology: each node represents a decision point based on a specific parameter, determining the progression to the next branch. This iterative process continues until a leaf node is reached, representing the final predicted outcome (ASIA prediction). To assess the accuracy of the constructed decision tree, the Random Tree algorithm was used to generate the model based on the dataset.

As for the second machine learning approach, WEKA’s Neural Network was utilized to construct an Artificial Neural Network (ANN), a widely recognized method under Supervised Machine Learning, particularly prevalent in the medical field. This intelligent system was implemented using WEKA’s Multi-Layer Perceptron, which includes a hidden layer. The training process was conducted using the Error Back-Propagation algorithm. Specifically, the structure of the Neural Network followed an I-H-O (Input - Hidden layers - Output layers) format. The training of the Neural Network was initiated by gradually increasing the number of neurons (H) in the hidden layer while also incrementally extending the number of training epochs. By keeping the learning rate constant, a consistent reduction in error per training epoch was observed, along with a steady improvement in classification performance. The optimal results were obtained with seven hidden neurons and 15,000 training epochs, after which the performance of the Neural Network remained stable.

Bayesian classifiers were also employed, representing a family of classification algorithms based on Bayes’ Theorem. Rather than a single method, Bayesian classification consists of multiple algorithms that share a common principle: each feature used in classification is assumed to be independent of the others. Among these algorithms, the Naïve Bayes classifier is one of the simplest yet highly effective models, allowing for the rapid development of machine learning models with fast prediction capabilities. Naïve Bayes is primarily used for classification tasks and is particularly well-suited for text classification problems. Since text classification involves high-dimensional data, where each word corresponds to a unique feature, the Naïve Bayes algorithm proves useful in applications such as spam detection, sentiment analysis, and rating classification. One of its key advantages is its computational efficiency, enabling swift processing and simplified predictions even in cases involving high-dimensional data (WEKA Machine Learning Group at the University of Waikato). This model estimates the probability that a given instance (e.g., different types of EPs) belongs to a specific class based on a predefined set of features (final ASIA). It functions as a probabilistic classifier, assuming that the presence of one feature does not influence the presence of any other feature. Although this assumption rarely holds in real-world scenarios, the model still delivers effective classification results. The algorithm relies on Bayes’ Theorem for both training and prediction. The dataset was randomly divided, with 66% allocated for training the machine learning models, while the remaining portion was used for testing and evaluating the WEKA-generated models.

Lastly, the Random Forest algorithm was implemented, which builds upon the well-established bagging method by incorporating both bagging and feature randomness to create an ensemble of uncorrelated decision trees. Feature randomness, also known as feature bagging or the “random subspace method,” ensures low correlation among decision trees by generating a random subset of features. This distinguishes Random Forest from traditional decision trees, where all potential feature splits are considered, whereas Random Forest selects only a subset of features for splitting. The Random Forest algorithm requires three primary hyperparameters to be set before training: node size, the number of trees, and the number of features sampled. Once configured, the classifier can be used for both regression and classification tasks. The model consists of multiple decision trees, each built from a bootstrap sample- a randomly selected dataset drawn from the training set with replacement. Approximately one-third of this sample is reserved as test data, known as the out-of-bag (OOB) sample, which is later used for validation. Another layer of randomness is introduced through feature bagging, enhancing dataset diversity and reducing correlation among decision trees. The prediction process varies based on the type of problem: for regression tasks, individual decision tree outputs are averaged, while for classification tasks, the final class is determined through majority voting—i.e., selecting the most frequently predicted categorical variable. Finally, the OOB sample serves as a form of cross-validation, ensuring a reliable prediction outcome.

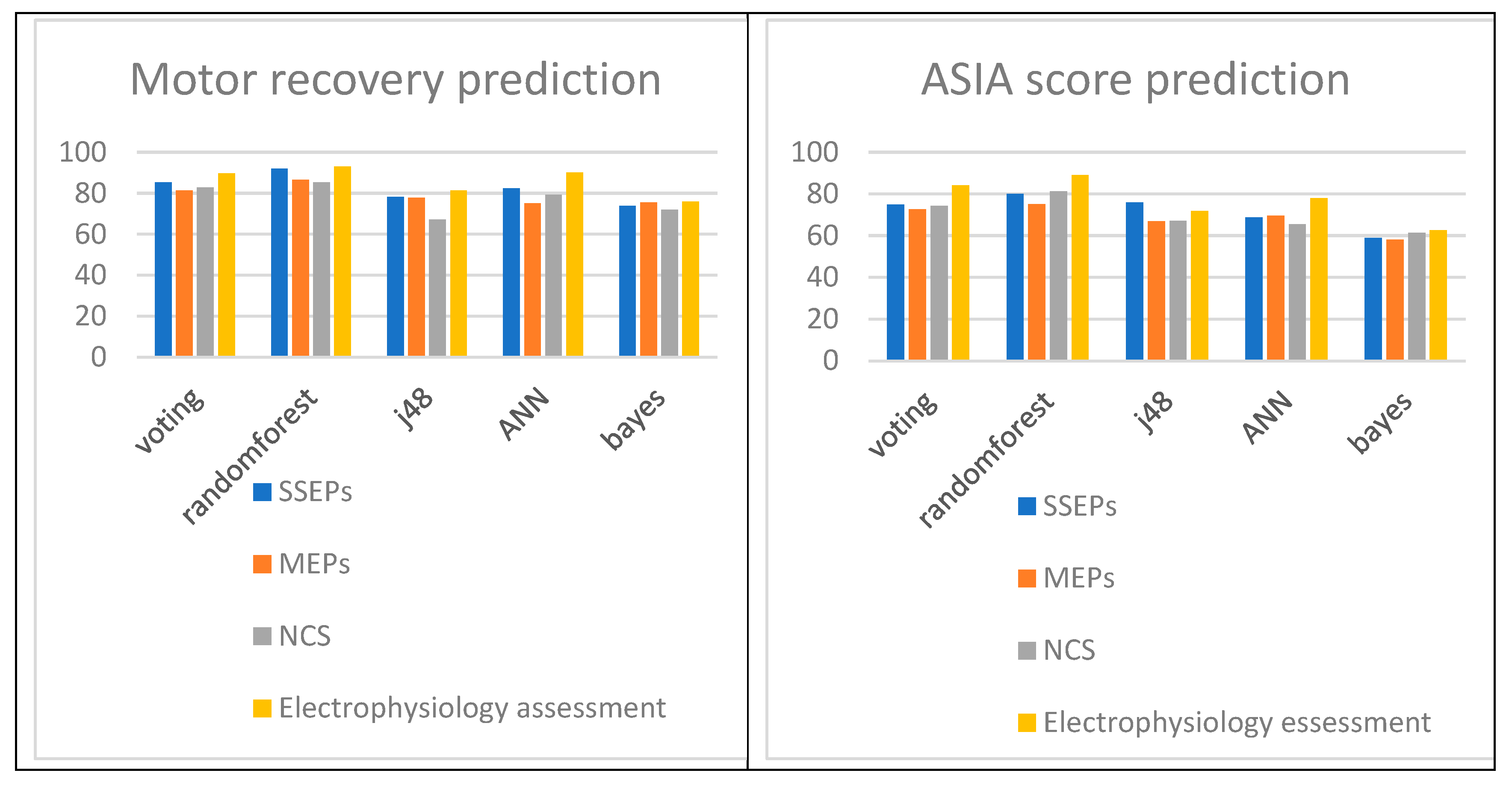

The performance of the machine learning models was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC-ROC) in test set (randomly selected the rest 34% of total). Part of the results of the models on the testing set are shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 1. We calculated the prediction accuracy of

motor recovery, after disease progression as well as current

ASIA score, according to all input parameters of clinical and electrophysiological assessment. Possible electrophysiology biomarkers were divided into SEPs, MEPs and all NCSs data compared with clinical evaluation results.

All above results reveal the importance of SEPs as predictors of

motor recovery of SCI patients according to their accuracy performance. According to

Table 1 the Vote, Decision Trees (randomforest and J48), Neural Network and Bayes for SSEPs attained accuracies of 85,4%,

91,9%, 78,2%, 82,5% and 73,9% respectively that are better than MEPs that attained accuracies of 81,3%, 86,6%, 77,9%, 75,2% and 75,6%, better or comparable to NCVs that attained accuracies of 82,9 %, 85,4%, 67,1%, 79,2% and 71,9%. The SSEPs could be demonstrated as the best motor recovery predictors after SCI with comparable efficacy to that of MEP of NCV findings mostly depending on the classification algorithm (

Figure 2).

Additionally the above results reveal the importance of SEPs as biomarkers for

ASIA score calculation of SCI patients according to their accuracy performance. According to Table 3 the Vote, Decision Trees (randomforest and J48), Neural Network and Bayes for SSEPs attained accuracies of 74,9 %, 80,1%, 76,0%, 68,7% and 58,9% respectively that are better than MEPs that attained accuracies of 72,7%, 75,2%, 67,0%, 69,5% and 58,1%, better or comparable to NCVs that attained accuracies of 74,4%,

81,3%, 67,1%, 65,4% and 61,4%. The SSEPs could be demonstrated as the best motor recovery predictors after SCI with comparable efficacy to that NCV findings most commonly used in clinical practice worldwide (

Figure 2).

Nevertheless, electrophysiology assessment should always be included, when available, as it elevates the total accuracy from only clinical investigation to the level of

93,1% (from at most 75,6%) for final motor recovery prediction, ASIA score determination and consequently disease follow up to the level of

89% (from at most 66,3%). More data are needed to certify the above results (

Table 1).

Finally, we suggest sensory electrophysiology assessment (including SEP and NCV data), which is significantly faster, less expensive, portable, and simpler to administer than other prognostic tests as MRI or even surgery data, and more effective than clinical assessment methods such as AIS, in functioning as biomarkers for SCI scaling and prediction of recovery possibility. By integrating individualized electrophysiological data, we can move toward a precision-medicine approach, tailoring treatment strategies and rehabilitation plans to each patient’s unique neurological profile, ultimately improving functional outcomes.

4. Discussion

Patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) frequently undergo electrophysiological assessments, such as motor evoked potentials (MEPs) and nerve conduction studies (NCSs), to evaluate neurological deficits and predict recovery potential. Empirical studies have established significant correlations between electrodiagnostic findings and ASIA (American Spinal Injury Association) scores, demonstrating that lower ASIA scores are associated with more severe neurological impairments (Singh et al., 2020). Furthermore, specific electrophysiological parameters, including nerve conduction velocity and motor unit potential recruitment, have been shown to enhance the predictive accuracy of ASIA assessments regarding recovery outcomes. By identifying preserved neural pathways, electrophysiological evaluations can provide critical insights that inform rehabilitation strategies and contribute to improved functional recovery (Huang et al., 2022). However, relying solely on ASIA scores might overlook the subtler nuances of potential recovery, suggesting the need for a more integrated evaluation approach.

Our research has demonstrated that somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) hold significant prognostic value in predicting motor recovery in SCI patients. Specifically, our findings indicate a positive correlation between SSEP latencies and motor recovery, further substantiated by their association with the ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS). These findings align with existing literature suggesting that SSEPs and MEPs exhibit greater sensitivity in detecting disease progression than conventional clinical assessments, while also offering cost-effective and time-efficient advantages (Margaritella et al., 2012).

Additionally, the integration of machine learning algorithms into SCI prognostic modeling presents an opportunity to further refine predictive accuracy. By analyzing large-scale datasets, these algorithms can identify complex patterns that may not be immediately discernible to clinicians. Such advancements not only optimize the decision-making process but also enable healthcare professionals to make evidence-based decisions informed by real-time data analysis. The application of predictive analytics facilitates early intervention strategies, allowing for timely modifications in treatment plans that align with patients' evolving clinical needs. As these technological innovations continue to progress, they hold the potential to transform the management of chronic neurological conditions, paving the way for more personalized, precise, and effective treatment pathways.

Further research is required to establish evoked potentials (EPs) as reliable biomarkers for SCI, particularly given their substantial advantages over traditional imaging and biochemical methodologies. EPs are considerably more cost-effective, portable, and straightforward to administer than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), making them a promising alternative for widespread clinical application. Establishing their efficacy as diagnostic and prognostic tools could enhance accessibility to advanced neurological assessments in diverse healthcare settings.