1. Introduction

Preterm birth and poor growth increase the risk of developing the chronic lung disease bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). While the development of BPD in preterm neonates is multifactorial, poor growth and nutritional deficits contribute to the BPD lung phenotype of impaired alveolar formation. Important nutrients in the context of BPD and lung development include long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), particularly the long-chain omega 3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid, (DHA) [

1].

The involvement of DHA deficiency in the development of BPD, and potential protective effects of DHA supplementation in resolving lung outcomes in preterm neonates and in animal studies has been a focus for over a decade. In preterm infants born <30 weeks gestation, DHA decreases rapidly over the first week of life, and decreased DHA is associated with increased BPD [

2]. Other studies conducted to assess the effects of DHA supplementation on neurodevelopment, with BPD as a secondary outcome, showed a positive impact of enteral DHA supplementation on BPD in a subset of preterm neonates [

3]. The concept that DHA is beneficial to the developing lung, particularly in the context of growth restriction and neonatal lung injury, is also supported by animal studies [

4,

5,

6,

7]. As a result of the body of research supporting a role for DHA in the development of BPD, several clinical trials examining the effects of DHA supplementation of preterm infants on BPD rates and severity have been conducted. However, these trials show that supplemental DHA administration to preterm neonates may actually increase the incidence of BPD in subsets of neonates [

8,

9]. Given the need for, and potential consequences of, lipid supplementation of preterm neonates, a comprehensive understanding of the effects of lipid supplementation on the developing lung is essential.

One key lipid responsive molecular mediator of lung development is the transcriptional activator PPARγ. PPARγ is well established to have important functions in the lung, and is necessary for the epithelial-mesenchymal interactions required for lung development and lung vascular integrity [

10,

11,

12]. PPARγ is also essential in the lung response to injury, and injury effects can often be mitigated by PPARγ activation, which can be accomplished by DHA [

4,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Like many transcription factors, PPARγ is subject to extensive alternative splicing. One splice variant of PPARγ, the PPARγ delta 5 (PPARγΔ5) variant has been reported in adipose and kidney tissue, and functions as a dominant-negative protein isoform due to lack of a transactivation domain [

17,

18]. However, whether PPARγΔ5 is expressed in the lung, and whether its expression is altered by PGR and/or DHA supplementation is unknown.

In order to elucidate mechanistic effects of growth and DHA on lung outcomes, we use a rat model of postnatal growth restriction (PGR) [

19]. We recently showed that prolonged PGR, without additional lung injury, impairs lung structure and function in the rat. In this model, the lung characteristics are similar to those of neonates with BPD, including increased alveolar wall thickness, decreased lung compliance, and increased tissue damping [

19]. Here, we aim to determine the effects of DHA supplementation on lung outcomes in our previously described PGR rat model, as well as expression of PPARγ and the PPARγΔ5 splice variant. We hypothesize that the PPARγ splice variant, PPARγΔ5, will be expressed in the rat lung, and that DHA supplementation of PGR rat pups will alter circulating lipid profiles, lung mechanics, and PPARγ variant expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rat Model of PGR

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Utah Animal Care and Use Committee, following the NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Timed pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were housed in a controlled environment with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and unrestricted access to food and water. We employed the postnatal growth restriction (PGR) model as previously described by our group [

19]. Briefly, at birth, pups were assigned to foster dams to establish litter sizes of either eight (control) or sixteen (PGR). Pups remained within their respective litters for the study duration. On postnatal day 21, animals were either euthanized for tissue and serum collection (decapitated under anesthesia with Ketamine/Xylazine at 80/12 mg/kg) or assigned to lung mechanics assessments. Each litter contributed one male and one female pup for experimental analyses.

2.2. DHA Supplementation

At delivery, rat dams from the PGR groups were randomized to receive either standard rat chow (6% fat from soybean oil, EnVIGO Teklad, Indianapolis, IN) or rat chow supplemented with DHA at 0.01% of total fats (LoDHA) or DHA at 0.1% of total fats (HiDHA) (Nu-Chek-Prep, Inc., Elysian, MN). The DHA chow was formulated by substituting the desired percentage of soybean oil with pure DHA. All rat chow formulations were isocaloric and equally tolerated by the dams. All dams had ad libitum access to chow and water during lactation.

2.3. Serum Fatty Acids

Serum fatty acid composition was analyzed via gas chromatography following transesterification, as previously described by our group [

19,

20]. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were generated via transesterification using heptadecanoic acid as an internal standard for quantification. Analyses were performed on an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a capillary column, enabling the detection of fatty acids with chain lengths ranging from 10 to 24 carbons. FAMEs were identified and quantified using the Supelco 37 FAME mix (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and data processing was conducted with OpenLAB Chromatography software (Agilent Technologies).

2.4. Lung Mechanics

Lung mechanics were assessed using the FlexiVent FX 2 system (SCIREQ, Montreal, Canada) and analyzed with FlexiWare 7.2 software (Service Pack 2, Build 728; SCIREQ, Montreal, Canada). On postnatal day 21, rat pups were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg). Following tracheostomy, a 16- or 18-gauge cannula was inserted, and animals were connected to the FlexiVent system. Ventilation was maintained at a rate of 150 breaths per minute with tidal volumes of 10 mL/kg and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 3 cm H₂O. After a stabilization period of 3 minutes to establish consistent breathing patterns and confirm the absence of air leaks, vecuronium bromide (1 mg/kg, IP) was administered as a paralytic agent.

Lung function was evaluated using automated maneuvers, as previously described [

21]. Inspiratory capacity (IC) and static compliance (Cst) were derived from quasistatic pressure-volume (PV) loops recorded over a pressure range of 3 to 30 cm H₂O. To differentiate airway mechanics from parenchymal properties, the forced oscillation technique (FOT) was applied [

21]. Respiratory impedance data were modeled using the constant phase equation to obtain Newtonian resistance (Rn), an index of airway narrowing, as well as tissue elastance (H) and tissue damping (G), which reflect alveolar stiffness and resistance, respectively. Tissue hysteresivity (η, G/H) was also calculated to assess viscoelastic properties of the lung.

2.5. Identification of PPARγΔ5 in the Lung

Lung RNA was extracted from lung tissue from control rats at birth, postnatal day 12, and postnatal day 21 and reverse transcribed as previously described [

19]. Gene specific primers were used to amplify the region of the Pparγ transcript between exon 4 and exon 6. Primer sequences were: forward (within exon 4): CGAGAAGGAGAAGCTGTTGG and reverse (within exon 6): GCACGTGCTCTGTGACAATC. PCR product was subject to gel electrophoresis using 2.2% agarose FlashGel

® Recovery Cassettes and measured (57022, Lonza Bioscience, Rockland, ME). Resulting bands were excised and sequenced by the University of Utah Sequencing Core.

2.6. mRNA Transcript Levels

Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR was used as described by our group [

19,

22] to measure the abundance of lung Pparγ, and of the PparγΔ5 splice variant. We used an assay-on-demand primer/probe set for Pparγ, which covers the exon boundary between exon 5 and 6 (Rn00440945_m1, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). To measure levels of PparγΔ5 we used a custom primer/probe set spanning the exon 4-6 junction (forward, CGAGAAGGAGAAGCTGTTGG; reverse, GCGGTTGATTTGTCTGTTGT; probe, CCCTGGCAAAGCATTTGTAT). mRNA levels of PPARγ target gene, Perilipin 2 (Plin2) was also measured using the following Assay on Demand: Rn01399516_m1. For all measures, the comparative CT method was used, with GADPH as an internal control.

2.7. Protein Abundance

We utilized immunoblot to measure protein levels of PPARγ and PPARγΔ5. Proteins were separated NuPAGE™ Bis-Tris Midi Protein Gels, 4 to 12% (WG1403BOX, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). Following electrophoresis, protein was transferred using PVDF Transfer Stacks (IB34001, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) and dry-transfer with the iBlot™ 3 Western Blot Transfer Device (IB31001, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). Total protein normalization was performed using No-Stain™ Protein Labeling Reagent according to manufacturer instructions (A44449, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). Membranes were probed using anti-PPARγ polyclonal antibody (16643-1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL) in SuperSignal™ Western Blot Enhancer. Membranes were incubated in SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate according to manufacturer instructions (34580, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), and imaged using Universal settings of the iBright™ CL1500 Imaging System (A44114, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA).

2.8. Statistics

Groups were Control receiving a regular diet (Control), PGR with a regular diet (PGR), PGR with 0.01% DHA diet (PGR+LoDHA), and PGR with 0.1% DHA diet (PGR+HiDHA). Males and females were treated as separate groups. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s post-hoc protected least-significance difference was used to determine differences between groups. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Rat Model of PGR and DHA Supplementation

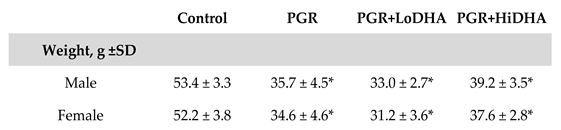

As we previously reported, our model of PGR resulted in a significant decrease in weight at day 21 in both males and females compared to control (

Table 1). PGR with a regular diet resulted in a 33% decrease in body weight in males. The addition of DHA supplementation in male rat pups did not improve weight gain in PGR, with PGR+LoDHA and PGR+HiDHA rat pups weighing 38% and 27% less than male controls, respectively. Similarly, in females, PGR resulted in a 34% reduction in body weight in the regular diet group, and a 41% and 28% reduction in body weight with PGR+LoDHA and PGR+HiDHA, respectively.

3.2. Serum Fatty Acids

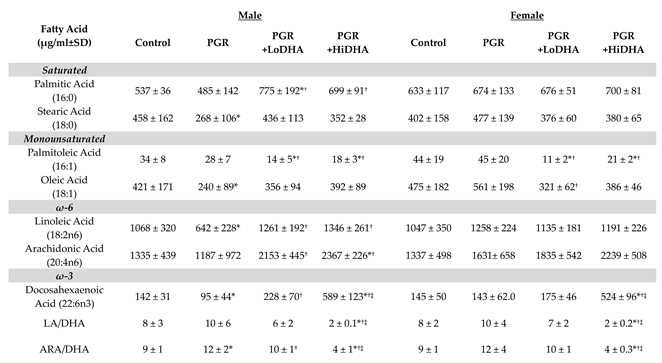

Both PGR and DHA supplementation significantly affected serum fatty acid levels (

Table 2). PGR with a regular diet altered serum levels of several fatty acids in male rat pups. In male rat pups, PGR on a regular diet decreased serum levels of stearic acid (18:0) by 40%, oleic acid (18:1) by 43%, linoleic acid (18:2n6) by 40%, and DHA (22:6n3) by 33% compared to controls. PGR also increased the ARA/DHA ratio by 40% in male rat pups. In contrast, in female rat pups, PGR on a regular diet did not alter levels of any serum fatty acid.

Consistent with the experimental design, serum DHA was increased by maternal DHA supplementation in PGR rat pups. In male PGR rat pups, the LoDHA diet increased serum DHA by 140% compared to PGR on a regular diet, while the HiDHA diet increased serum DHA by 520% compared to PGR on a regular diet and 315% compared to controls. In female PGR rat pups, the HiDHA diet increased serum DHA by 370% compared to PGR on a regular diet and 360% compared to controls.

DHA supplementation of PGR rat pups also significantly altered serum levels of other fatty acids. In male PGR rat pups, the Lodha diet normalized levels of oleic acid (18:1), linoleic acid (18:2n6), and the ARA/DHA ratio, while serum levels of palmitoleic acid (16:1) decreased by 60% compared to controls, and palmitic acid (16:0) increased by 45% compared to controls. In female PGR rat pups, the Lodha diet also decreased levels of palmitoleic acid (16:1) by 75% compared to controls. In male PGR rat pups, the HiDHA diet increased serum levels of ARA by 77% compared to controls while also decreasing the LA/DHA ratio by 75% and the ARA/DHA ratio by 56% compared to controls. Similarly, in female PGR rat pups, the HiDHA diet decreased the LA/DHA ratio by 75% and the ARA/DHA ratio by 55%.

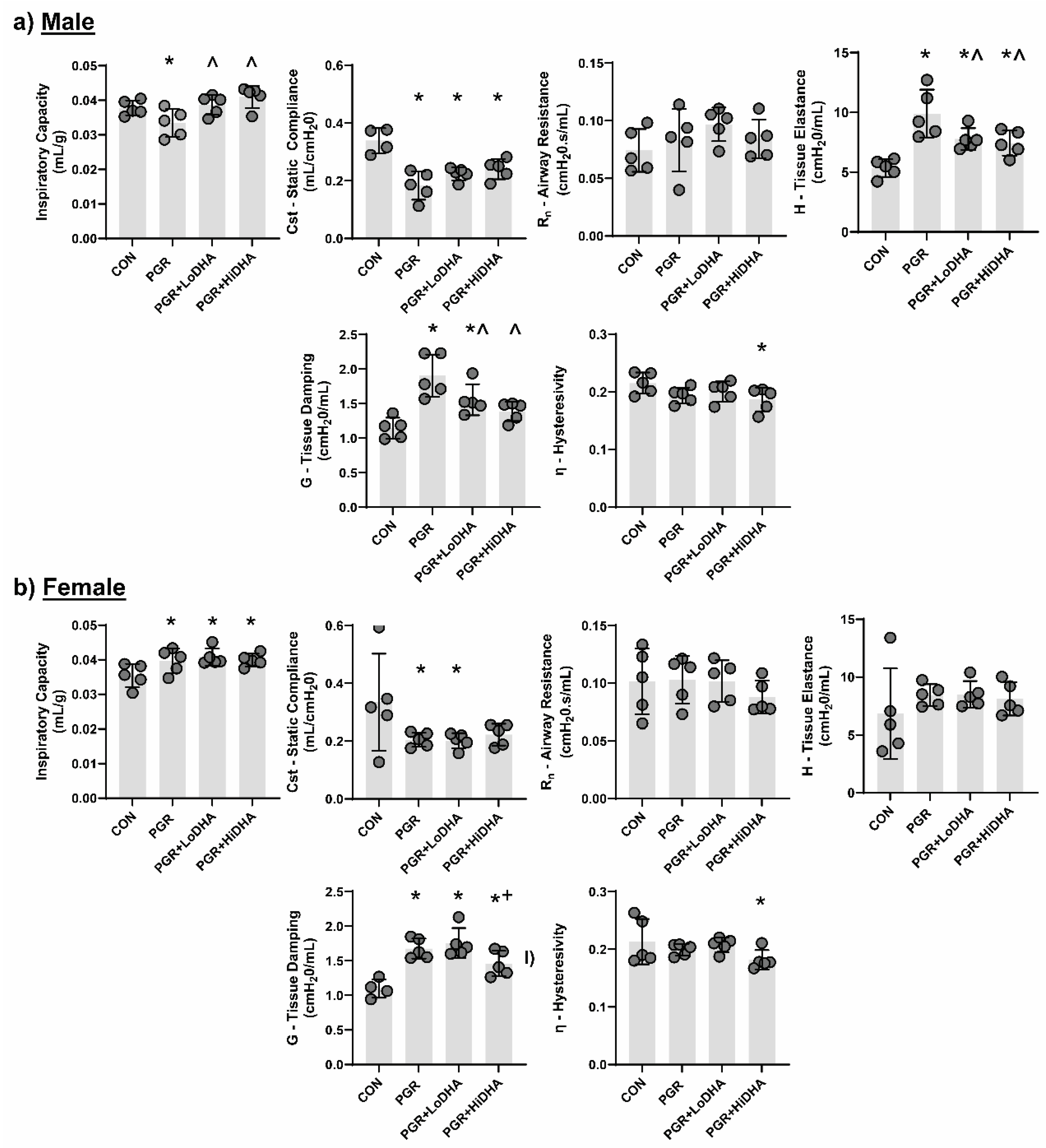

3.2. Lung Mechanics

Using closed chest pressure-volume loops to determine quasi-static lung compliance and the forced oscillation technique to differentiate between central and peripheral lung tissue, we measured lung mechanics in all four groups (control, PGR, PGR+LoDHA, PGR+HiDHA).

Similar to our previous report [

19], PGR altered lung mechanics in male and female rat pups. In male rat pups, PGR on a regular diet decreased inspiratory capacity by 12%, decreased static compliance by 46%, and increased tissue elastance by 85% and tissue damping by 66% compared to controls (

Figure 1a-e). In female rat pups, PGR increased inspiratory capacity by 11%, decreased static compliance by 39%, and increased tissue damping by 52% compared to controls (

Figure 1g-l).

DHA supplementation of PGR rat pups did not restore lung function to that of controls in either sex. In male PGR rat pups, while inspiratory capacity was normalized, static lung compliance remained reduced (34% and 30% decrease compared to controls with LoDHA and Hi DHA diets respectively), and tissue elastance remained increased (45% and 38% increase compared to controls with LoDHA and HiDHA diets respectively). Tissue damping remained increased male PGR rat pups with LoDHA diet (35% increase relative to control), but was normalized with HiDHA diet. Additionally, HiDHA diet decreased lung hysterestivity by 14% compared to control (

Figure 1a-e). In female PGR rat pups, inspiratory capacity remained increased (15% and 12% increase compared to controls with LoDHA and Hi DHA diets respectively), static lung compliance remained reduced with the LoDHA diet (40% compared to controls) but was normalized with HiDHA diet. Tissue damping remained increased female PGR rat pups on both diets (59% and 32% increase compared to controls with LoDHA and Hi DHA diets respectively). Similar to male PGR rat pups, in female PGR rat pups, HiDHA diet decreased lung hysterestivity by 15% compared to control (

Figure 1g-l).

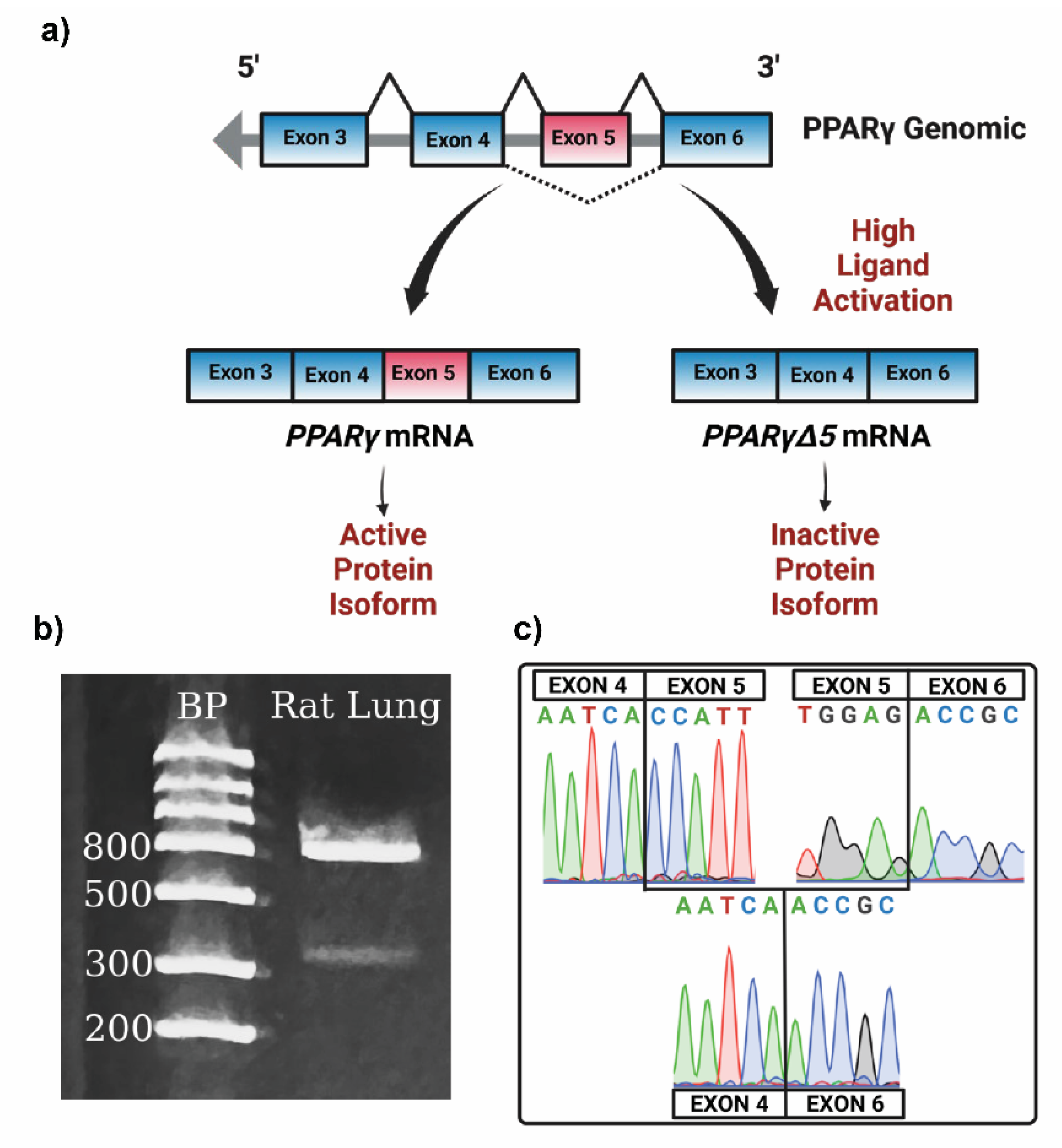

3.3. PPARγΔ5 in the Lung

To determine whether

PparγΔ5 is expressed in the lung, we performed PCR on cDNA isolated from rat lungs, using primers contained within exon 4 (forward) and exon 6 (reverse). Gel electrophoresis of our PCR product produced two bands, one measuring approximately 850bp and the other measuring approximately 450bp, consistent with the estimated molecular weights of the targeted amplicons of full-length

Pparγ and the

PparγΔ5 splice variant, respectively (

Figure 2b). Sequencing confirmed that the 850 bp band amplified

Pparγ containing exon 5, and the 450bp band amplified the

PparγΔ5 variant with exon four spliced directly to exon 6 (

Figure 2c).

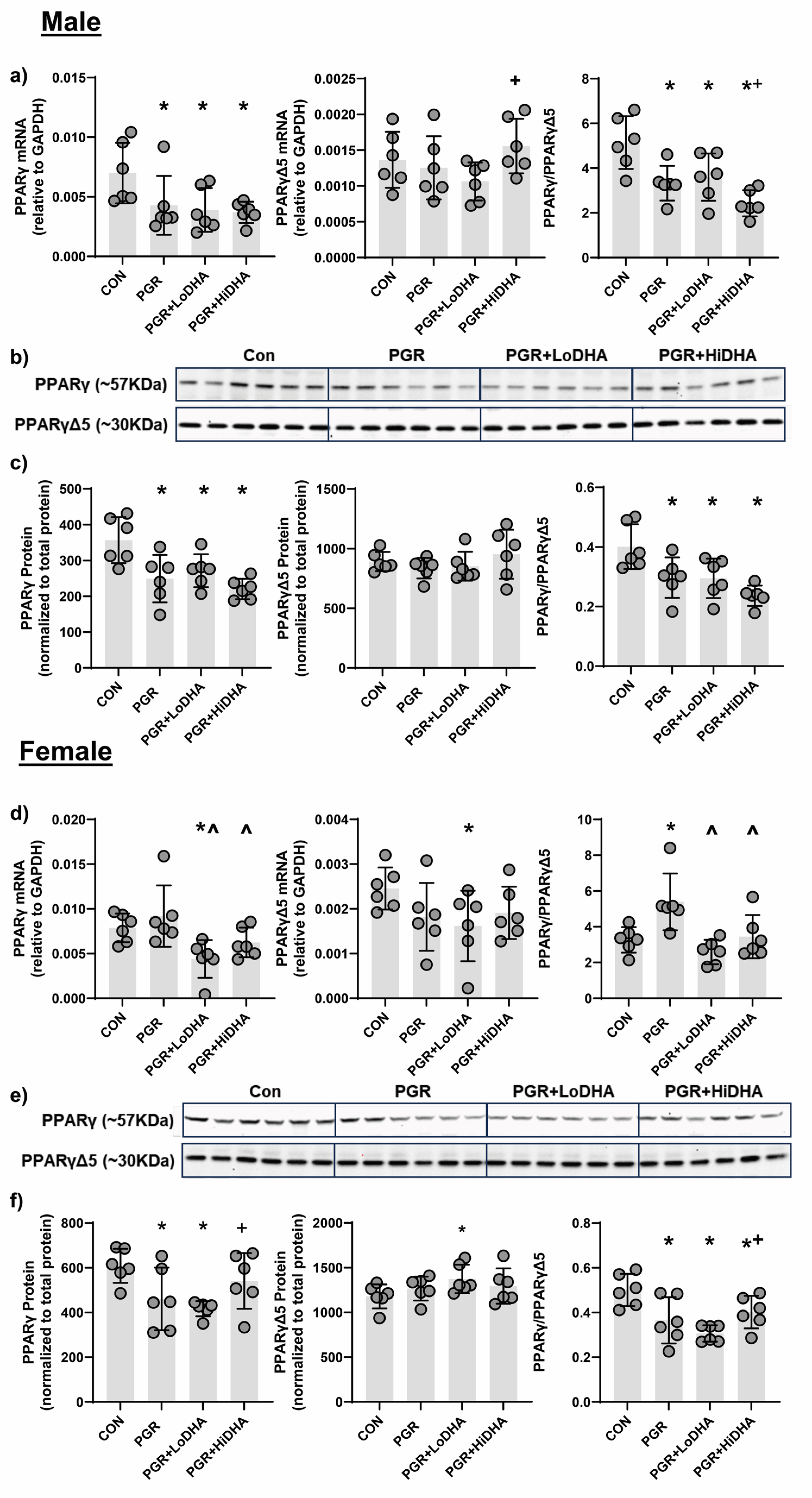

3.4. PPARγ mRNA and Protein Quantification

We quantified levels of

Pparγ and

PparγΔ5 mRNA and PPARγ and PPARγΔ5 protein in all study groups. In male rat lung, PGR with a regular diet decreased

Pparγ mRNA by 39% compared to control, but did not alter

PparγΔ5 mRNA (

Figure 3a). The

Pparγ/PparγΔ5 ratio was decreased in male PGR rat lung on a regular diet by 35% relative to control (

Figure 3a). In male rat lung, PGR with a regular diet decreased PPARγ protein levels by 30% compared to control, without affecting protein levels of PPARγΔ5. Similar to mRNA findings, in male rat lung, PGR with a regular diet decreased the PPARγ/PPARγΔ5 ratio by 26% compared to control (

Figure 3b,c). In female rat lung, PGR with a regular diet decreased did not affect mRNA levels of

Pparγ or

PparγΔ5 (

Figure 3d). However, the resulting

Pparγ/PparγΔ5 ratio was increased in female PGR rat lung on a regular diet by 65% compared to control (

Figure 3d). In female rat lung, PGR with a regular diet decreased PPARγ protein levels by 24% compared to control, without affecting protein levels of PPARγΔ5. An female rat lung, PGR with a regular diet decreased the PPARγ/PPARγΔ5 ratio by 27% compared to control (

Figure 3e,f).

In male PGR rat lung,

Pparγ mRNA levels remained decreased with both DHA diets (44% and 46% compared to control for LoDHA and HiDHA respectively), and

PparγΔ5 mRNA remained unchanged (

Figure 3a). Similarly, in male PGR rat lung, PPARγ protein levels remained decreased with both DHA diets (24% and 38% compared to control for LoDHA and HiDHA respectively), and PPARγΔ5 protein levels were unaffected (

Figure 3b,c). The resulting PPARγ/PPARγΔ5 protein ratio also remained reduced in male PGR rat lung with both DHA diets (27% and 41% compared to control for LoDHA and HiDHA respectively).

In female PGR rat lung,

Pparγ and

PparγΔ5 mRNA levels decreased with the LoDHA diet (44% and 34% respectively compared to control) (

Figure 3d). In female PGR rat lung, PPARγ protein levels decreased with LoDHA diet by32% compared to control, while PPARγΔ5 protein levels increased by 17% relative to control (

Figure 3b,c). The resulting PPARγ/PPARγΔ5 protein ratio, however, remained reduced in female PGR rat lung with both DHA diets (39% and 20% compared to control for LoDHA and HiDHA respectively).

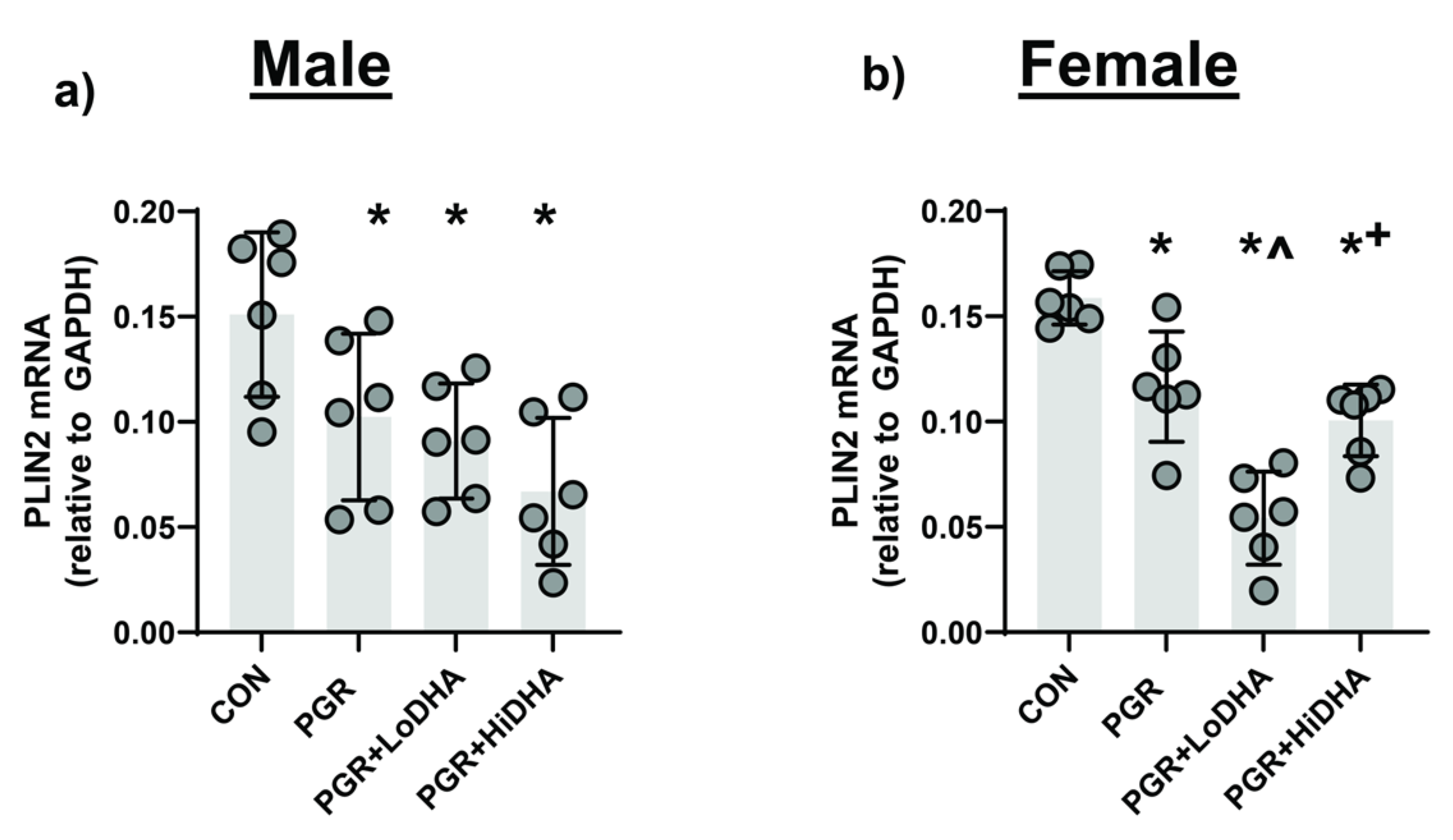

3.5. mRNA of downstream PPARγ Target Gene Plin2

To assess PPARγ activity, we measured mRNA levels PPARγ target gene Perilipin-2 (

Plin2). In male rat lung, PGR with a regular diet decreased

Plin2 mRNA levels by 32% compared to controls (

Figure 4a). In female rat lung, PGR with a regular diet decreased

Plin2 mRNA levels by 27% compared to controls (

Figure 4b). In male rat PGR lung,

Plin2 mRNA remained decreased with both DHA diets (40% and 56% compared to control for LoDHA and HiDHA respectively) (

Figure 4a). In female rat PGR lung,

Plin2 mRNA also remained decreased with both DHA diets (66% and 37% compared to control for LoDHA and HiDHA respectively) (

Figure 4b).

4. Discussion

The development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia is multifactorial, and the molecular drivers and prevention of this disease remain poorly understood. Given the confounding data demonstrating the importance of DHA in lung development and prevention of BPD, combined with the recent clinical trials demonstrating that DHA supplementation of preterm neonates may increase BPD, a comprehensive understanding of the molecular effects of DHA supplementation in the developing lung are required. Using a combined model of postnatal growth restriction and DHA supplementation, we reiterate that postnatal growth restriction alters circulating fatty acids and impairs lung mechanics in rats and illustrate that these effects are not ameliorated with DHA supplementation. We also demonstrate, for the first time, that a dominant negative splice variant of PPARγ, a key regulator of lung development, is expressed in the developing lung. We also show that PPARγ activity is decreased in PGR and not improved with DHA supplementation. Collectively, our data support the view that postnatal DHA supplementation does not improve lung outcomes in PGR.

Recent clinical trials examining the effects of DHA supplementation of preterm neonates used either direct enteral supplementation of DHA to preterm neonates (N-3 fatty acids for improvement in Respiratory Outcomes (N3RO) trial), or DHA administration via maternal DHA supplementation and the provision of breastmilk to preterm neonates (The Maternal Omega-3 Supplementation to Reduce Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Very Preterm Infants (MOBYDIck) trial) [

8,

9]. The N3RO trial ultimately concluded that neonatal DHA supplementation did not improve the overall incidence of BPD and may increase the incidence of BPD in neonates born at less than 27 weeks. Considering these results from the N3RO trial, an early interim analysis was performed of the MOBYDIck trial. The analysis favored placebo over DHA in BPD-free survival, and the study was terminated due to concern for potential harm to future participants. These outcomes were surprising given the dearth of information demonstrating the importance of DHA in lung development and response to injury, and several rationales for these outcomes and currently being explored. One potential contributor to the negative effects of isolated DHA supplementation is the effect of increased DHA on other circulating fatty acids, including the omega-6 fatty acid ARA.

In the N3RO trial, blood levels of ARA were decreased in the DHA group, as was the ARA:DHA ratio [

8]. In the MOBYDIck trial, blood lipids were not assessed. However, the average lipid composition of the maternal milk used in the trial was analyzed at two weeks [

23]. Findings from this analysis showed that while maternal DHA supplementation increased milk DHA levels, supplementation decreased the ARA:DHA ratio [

23]. The potential importance of including ARA in supplementation is highlighted by other studies that used supplementation with a combination of ARA and DHA. Collectively, the studies that utilized a combination of ARA and DHA (at a 2:1 ratio) did not report negative effects on BPD outcomes [

24,

25].The changes to the ω3 to ω6 ratio and to arachidonic acid levels are especially notable, given the role ARA plays in modulating the inflammatory cascade. In our study, DHA supplementation significantly reduced the ARA:DHA ratio in both male and female rat pups.

An important consideration in the context of DHA supplementation, and disturbed circulating fatty acid profiles during lung development, is the transcriptional activator, PPARγ. PPARγ is required for appropriate lung development, particularly the formation of alveoli. Conditional knockout of PPARγ in mouse airway epithelial cells leads to airspace enlargement and disruption of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions [

10]. PPARγ activation also promotes myofibroblast differentiation to a lipid-laden lipofibroblast phenotype in the developing lung, characterized by high triglyceride levels, which has a significant role in lung maturation, including alveolar maturation [

26,

27,

28]. We and others have previously shown that neonatal rat pups exposed to fetal growth restriction or postnatal hyperoxia have decreased PPARγ expression and impaired alveolar formation. In both cases, lung phenotypes are reversed by PPARγ activation [

4,

16]. An important consideration, however, is that to achieve greater regulation, transcriptional activators also undergo alternative splicing and express dominant negative variants [

29].

PPARγ produces a dominant negative isoform, PPARγΔ5, via the alternative splicing of exon 5 [

17]. Studies in adipose tissue have shown that expression of PPARγΔ5 is increased by ligand activation of PPARγ. The protein isoform produced by alternative splicing of PPARγ exon 5 results in a premature stop codon and truncated protein isoform lacking the ligand binding domain and one transactivation domain [

17]. In adipose tissue, a decrease in the cellular PPARγ/PPARγΔ5 ratio reduces transcription of downstream target genes. In this study, we demonstrate, for the first time, that the PPARγΔ5 variant is expressed in the rat lung under control conditions. Given that DHA can act as a ligand for PPARγ, we considered whether supplemental DHA would increase the expression of PPARγΔ5 in the lung [

30]. Our data show that supplemental DHA has a limited effect on the levels of PPARγΔ5 mRNA or protein in the rat lung. However, given that the PPARγ/PPARγΔ5 ratio conveys overall functional potential, this may be a more appropriate metric. We demonstrated that PGR alone decreases the PPARγ/PPARγΔ5 ratio in the lung in both male and female rat pups, and that this decrease is associated with a decrease in the mRNA levels of the target gene Plin2 (also known as adipose differentiation-related protein), another critical player in lung development [

31]. Reduced PPARγ activity and expression of Plin2 are both associated with impaired lung development and the structural changes consistent with the altered lung function measures we detected. The addition of DHA to PGR rats in this study did not change the PGR-induced impaired lung function, nor did the diets significantly alter the PGR-induced reduction in PPARγ activity. An important caveat for our study is the timing of rat lung development. At our study timepoint, postnatal day 21, the rat lung has completed bulk alveolar formation. It will be important in subsequent studies to assess the effects of DHA on the rat lung during the transition from the saccular to alveolar stages. Also important will be studies aimed to determine the precise mechanisms by which PGR decreases the PPARγ/PPARγΔ5 ratio, and the cause-and-effect consequences of this change on lung development.

Our study is not without limitations. In this study we only examined circulating fatty acid profiles. An understanding of how PGR and DHA supplementation affect intrapulmonary fatty acid profiles is needed. An advantage of understanding intrapulmonary fatty acid profiles and circulating fatty acid profiles in the same system is the potential for the identification of fatty acid biomarkers that may be useful in identifying neonates with detrimental fatty acid complements.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that the novel splice variant of PPARγ, PPARγΔ5, is expressed in the lung, and that PGR reduces the PPARγ/PPARγΔ5 ratio in association with impaired lung mechanics. Despite DHA supplementation increasing circulating DHA levels in PGR rat pups, DHA did not further alter the molecular or function profiles of PGR rat pups. DHA supplementation did, however, disturb circulating fatty acid profiles for other LCPUFA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, LJM, AC, and CRM; methodology, LJM, JAM, and JEC; validation, LJM, JAM, AC; formal analysis, LJM, AC, JAM; investigation, AC, WC, DTW, NJ, AJ, CB, JZ, and JAM.; writing—original draft preparation, LJM.; writing—review and editing, LJM, CRM, JAM, and AC.; funding acquisition, LJM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) DK084036 (LJM) and 1-S10-OD021505-01 (JEC), and the Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah. AJ and CB were supported by the University of Utah Native American Internship (R25HL108828)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Utah (protocol number 21-09019/1827, approval November 30, 2023).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Division of Neonatology and the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah for support, and to Haimei Wang for managing the animal work used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BPD |

Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia |

| DHA |

Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| PPARγ |

Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor gamma |

| PGR |

Postnatal Growth Restriction |

| ARA |

Arachidonic Acid |

| PLIN2 |

Perilipin 2 |

References

- Poindexter, B.B. and C.R. Martin, Impact of Nutrition on Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Clin Perinatol., 2015. 42(4): p. 797-806. Epub 2015 Oct 2. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.R., et al., Decreased postnatal docosahexaenoic and arachidonic acid blood levels in premature infants are associated with neonatal morbidities. J Pediatr., 2011. 159(5): p. 743-749.e1-2. Epub 2011 Jun 12. [CrossRef]

- Makrides, M., et al., Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants fed high-dose docosahexaenoic acid: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 2009. 301(2): p. 175-82.

- Joss-Moore, L.A., et al., IUGR decreases PPARgamma and SETD8 Expression in neonatal rat lung and these effects are ameliorated by maternal DHA supplementation. Early Hum Dev, 2010. 86(12): p. 785-91.

- Rogers, L.K., et al., Maternal docosahexaenoic acid supplementation decreases lung inflammation in hyperoxia-exposed newborn mice. J Nutr., 2011. 141(2): p. 214-22. Epub 2010 Dec 22. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., et al., DHA suppresses chronic apoptosis in the lung caused by perinatal inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2015. 309(5): p. L441-8.

- Velten, M., et al., Maternal dietary docosahexaenoic acid supplementation attenuates fetal growth restriction and enhances pulmonary function in a newborn mouse model of perinatal inflammation. J Nutr., 2014. 144(3): p. 258-66. Epub 2014 Jan 22. [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.T., et al., Docosahexaenoic Acid and Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants. N Engl J Med, 2017. 376(13): p. 1245-1255.

- Marc, I., et al., Effect of Maternal Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation on Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia-Free Survival in Breastfed Preterm Infants: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA., 2020. 324(2): p. 157-167. [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.M., et al., Epithelial cell PPAR[gamma] contributes to normal lung maturation. Faseb J, 2006. 20(9): p. 1507-9.

- Cerny, L., J.S. Torday, and V.K. Rehan, Prevention and treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: contemporary status and future outlook. Lung, 2008. 186(2): p. 75-89.

- Gien, J., et al., Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma-Rho-kinase interactions contribute to vascular remodeling after chronic intrauterine pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol., 2014. 306(3): p. L299-308. Epub 2013 Dec 27. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.A., et al., Emerging PPARgamma-Independent Role of PPARgamma Ligands in Lung Diseases. PPAR Res, 2012. 2012:705352.(doi): p. 10.1155/2012/705352. Epub 2012 Jun 18.

- Hagood, J.S., Beyond the genome: epigenetic mechanisms in lung remodeling. Physiology (Bethesda). 2014. 29(3): p. 177-85. [CrossRef]

- Morales, E., et al., Nebulized PPARγ agonists: a novel approach to augment neonatal lung maturation and injury repair in rats. Pediatr Res, 2014. 75(5): p. 631-40.

- Rehan, V.K., et al., Rosiglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist, prevents hyperoxia-induced neonatal rat lung injury in vivo. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2006. 41(6): p. 558-69.

- Aprile, M., et al., PPARγΔ5, a Naturally Occurring Dominant-Negative Splice Isoform, Impairs PPARγ Function and Adipocyte Differentiation. Cell Rep., 2018. 25(6): p. 1577-1592.e6. [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.Y., et al., A PPARG Splice Variant in Granulosa Cells Is Associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Med., 2022. 11(24): p. 7285. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., et al., Postnatal growth restriction impairs rat lung structure and function. Anat Rec (Hoboken), 2023.

- Weinheimer, C., et al., Maternal Tobacco Smoke Exposure Causes Sex-Divergent Changes in Placental Lipid Metabolism in the Rat. Reprod Sci, 2020. 27(2): p. 631-643.

- McGovern, T.K., et al., Evaluation of respiratory system mechanics in mice using the forced oscillation technique. J Vis Exp, 2013(75): p. e50172.

- Joss-Moore, L., et al., Intrauterine growth restriction transiently delays alveolar formation and disrupts retinoic acid receptor expression in the lung of female rat pups. Pediatr Res, 2013. 73(5): p. 612-20.

- Fougère, H., et al., Docosahexaenoic acid-rich algae oil supplementation on breast milk fatty acid profile of mothers who delivered prematurely: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 21492.

- Hellström, A., et al., Effect of Enteral Lipid Supplement on Severe Retinopathy of Prematurity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr, 2021. 175(4): p. 359-367.

- Wendel, K., et al., Effect of arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid supplementation on respiratory outcomes and neonatal morbidities in preterm infants. Clin Nutr., 2023. 42(1): p. 22-28. Epub 2022 Nov 17. [CrossRef]

- McCulley, D., M. Wienhold, and X. Sun, The pulmonary mesenchyme directs lung development. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 2015. 32: p. 98-105.

- Kyle, J.E., et al., Cell type-resolved human lung lipidome reveals cellular cooperation in lung function. Sci Rep., 2018. 8(1): p. 13455. [CrossRef]

- Varisco, B.M., et al., Thy-1 signals through PPARgamma to promote lipofibroblast differentiation in the developing lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol., 2012. 46(6): p. 765-72. Epub 2012 Jan 20. [CrossRef]

- Scarpato, M., et al., Novel transcription factor variants through RNA-sequencing: the importance of being “alternative”. Int J Mol Sci, 2015. 16(1): p. 1755-71.

- Grygiel-Gorniak, B., Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and their ligands: nutritional and clinical implications--a review. Nutr J, 2014. 13: p. 17.

- Torday, J.S. and V.K. Rehan, Up-regulation of fetal rat lung parathyroid hormone-related protein gene regulatory network down-regulates the Sonic Hedgehog/Wnt/betacatenin gene regulatory network. Pediatr Res, 2006. 60(4): p. 382-8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).