1. Introduction

The concern with the quality of care throughout a serious illness that threatens the continuity of life has been a recurring theme, including the process of death and dying [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Although significant efforts are directed toward curative treatments in several countries, efforts focused on end-of-life care remain limited. Furthermore, important disparities exist in the quality of these care services across different countries [

1].

The results of the latest ranking published by The Economist on the quality of death in various countries showed that, among 80 countries analyzed, Brazil ranked 42nd. To prepare this ranking, 20 quantitative and qualitative indicators were analyzed and distributed into five categories: the palliative and health environment, human resources, accessibility to care, care quality, and the level of community engagement. Furthermore, Brazil ranked third to last in terms of quality of death among 81 countries studied, ahead only of Lebanon and Paraguay, according to the international report published in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management [

1,

5]

A justification for this result is linked to a widespread culture of denying the reality of death and dying [

2]. In light of this situation, it is crucial to foster cultural changes that acknowledge the significance of palliative care, recognize death as a natural aspect of life, and emphasize the quality of life for patients throughout their entire journey with a serious illness, including at the end of life, for both patients and their families [

5].

In Brazil, palliative care has been progressing steadily, marked by the significant achievement of the National Palliative Care Policy published in 2024. This policy aims to enhance autonomy and quality of life for patients, focusing on symptom control, the development of advanced care plans, and monitoring the active dying process. A key guideline of the policy is to promote awareness and education about palliative care throughout society [

6].

Education is fundamental in palliative care. It is essential that this education is accessible at all levels and tailored to various contexts [

7,

8]. This is particularly important in a country like Brazil, where some regions still face challenges in accessing essential services that contribute to quality of life, including healthcare, food, housing, income, education, and leisure [

7,

8,

9] and adapts to different realities [

4], especially in a country like Brazil, where there are still regions with limited access to essential services for quality of life, such as health, food, housing, income, education, and leisure [

9].

Among the strategies implemented, the Last Aid Courses (LAC) are particularly noteworthy. The concept of Last Aid is founded on the idea that knowledge of palliative care should be included in public education. The aim is to cultivate compassionate communities and to transform end-of-life care into a collective responsibility [

10,

11]. The Last Aid approach provides accessible ways for the general public to engage in discussions about death, dying, and grief, and it also suggests practical actions to offer support in various contexts [

11].

It is important to highlight that the concept was first described by Georg Bollig in 2008, and courses began to be offered in 2015 in Germany. Through a standardized curriculum and a slide set, the courses are held in over 22 countries, including Germany, Australia, Scotland, Slovenia, Brazil, and Singapore [

11,

12,

13,

14].

In 2020, LAC began its operations in Brazil, utilizing an international curriculum and slide set. Since then, it has offered both face-to-face and online courses in various locations, including cultural centers, healthcare centers, nursing homes, universities, and compassionate communities [

15].

Research findings indicate that LAC is not only feasible and well-received, but also has significant potential to enhance palliative care education for the general public across various countries [

10,

12,

16], including children and adolescents [

17]. However, as of now, only one study has examined courses conducted in Brazil. The authors evaluated a total of 13 courses in Germany, in contrast to just 2 online courses offered in Brazil [

16].

In light of this, it is crucial to conduct a study on LAC in Brazil to better understand its potential, challenges, and the experiences involved in its implementation across the country. This phase is particularly important, as emphasized by Bollig and Bauer. Research indicates that outcomes may vary depending on the location where LACs are implemented [

18]. Furthermore, LAC addresses a new demand arising from the National Palliative Care Policy [

6].

This study is also aligned with the needs outlined in the Global Atlas of Palliative Care, which highlighted the importance of strategies to promote education in palliative care and research on the topic, especially in low- and middle-income countries [

19].

Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate if LACs contribute to bringing knowledge and awareness of Palliative Care to different settings in Brazil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants of the LAC in Brazil from March to Nov 2024, who choose to respond the questionnaire provided after the course.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The study is a transversal study based on a mixed-methods approach with a combination of quantitative and qualitative data from a questionnaire

The data used to conduct the research is of primary origin, as it uses a questionnaire answered by LAC participants. The objective of the work is exploratory in nature, as it is characterized as an initial approach to the topic, seeking to analyze and describe the understanding and impact of the LAC on the course participants.

From March to Nov 2024, after attending a LAC, all participants were asked to complete a questionnaire containing quantitative and qualitative questions.

The present study is a part of an ongoing larger research project that aims to analyze the understanding and impact of the LAC on the perception of finitude, care, mourning, death literacy, and breaking of taboos among the participants.

After approval of the ethical committee the collected data was analyzed.

The data collection was conducted virtually through a questionnaire created on the Google Forms platform, featuring both open and closed-ended questions. The analysis of the data regarding participant characteristics was performed using ab-so-lute and relative frequencies. The open-ended questions were grouped into thematic categories and counted after their inductive evaluation.

In order to protect privacy, no personal data other than age, sex, and profession were collected.

Participants could choose whether or not to provide this information.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data

From March to Nov 2024 32 courses were offered in different settings in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Online and 343 people attended. The settings of the courses and gender characteristics of the participants are outlined in

Table 1.

A total of 246 participants completed the questionnaire.

Table 2 and

Table 3 show the quantitative data.

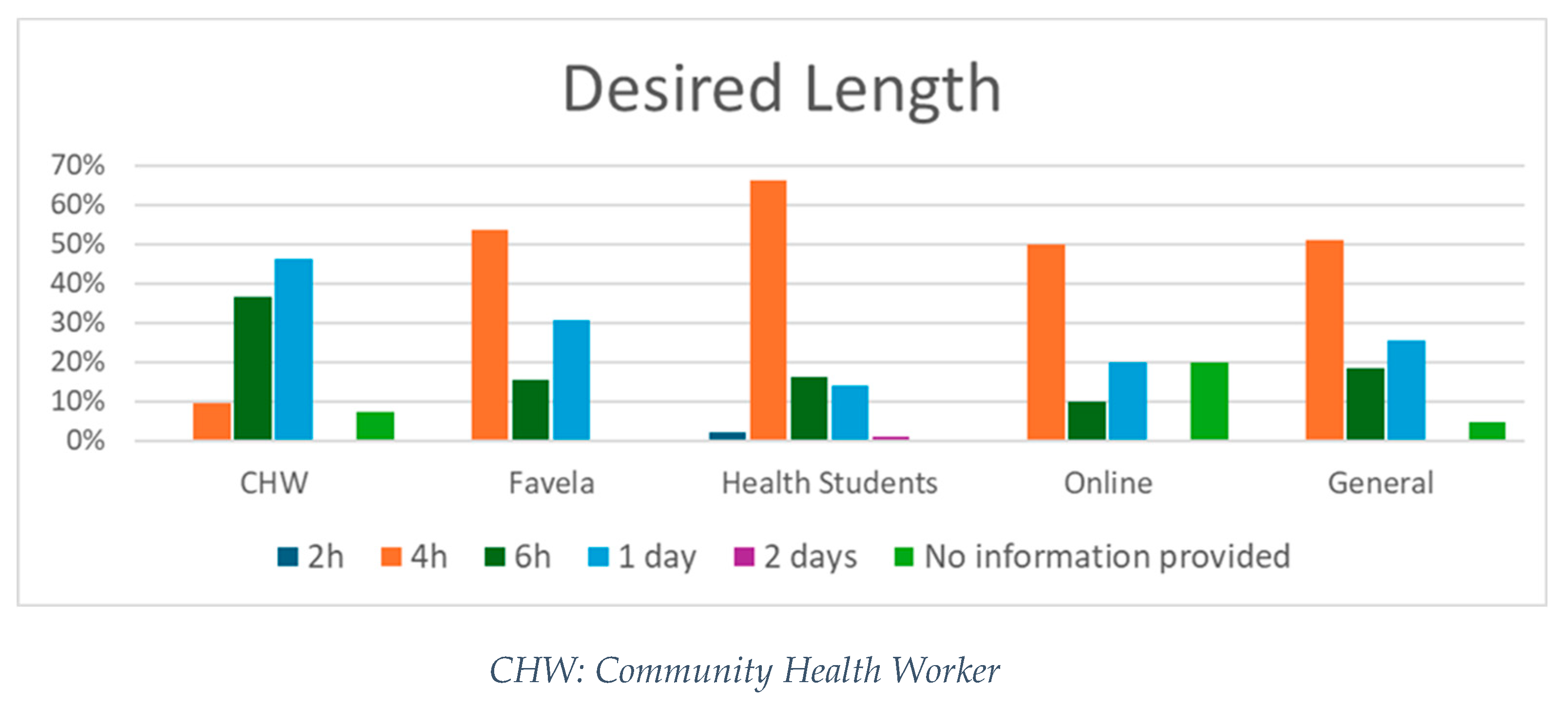

Figure 1.

Participants’ suggestions when asked about the length of the Last Aid Course.

Figure 1.

Participants’ suggestions when asked about the length of the Last Aid Course.

3.2. Qualitative Data

Participants were asked about the most important message they take from the course. The following examples show the impact the course had on participants. The quotes are sorted by settings.

Community Health Worker (CHW):

Death is part of life

Talking about death does not hasten death, that is, it does not attract death

That death is part of life, and we need to be prepared for this moment

Respect people’s wishes

Favela

The importance of talking about death with our family, since death is inevitable. Maintaining a dialogue with loved ones is the best way to find out what they want, and also to make my wishes clear.

The only certainty in life is death, we need to be prepared for this moment of farewell

Understanding about the health area that I will pass on to other people

Health Students

The importance of dying with dignity

The most important message I take away from the course is that talking about the process of dying is necessary and can be lighthearted.

The main message I take away from the Last Aid course is the importance of breaking the taboo around death. When we treat death naturally, we allow people to express their fears and desires openly, which brings more comfort and respect for their choices at this time in life. This ensures a more dignified dying process, both for the patient and for their families, making this phase less lonely and more welcoming.

Welcoming, listening, the time that the person is going through, including family members or caregivers, and trying to ease the pain. But above all, respect the patient’s decision, because just a touch as a gesture of affection makes all the difference at this time.

Online

I learned that dying doesn’t hurt 😯 I always imagined that dying was a heartbreaking moment for the person who is dying, and very distressing for those who are by their side, unable to help... It helped me face this moment with less fear.

Talking about death is very important

Living is an art, dying is the final signature of this masterpiece.

General

Death is part of life and there needs to be quality and humanity at this time as well. Death comes whether we are prepared or not.

We need to talk about Palliative Care.

That death is part of life and that with understanding I can make this process easier.

Knowing how to face death as something natural

Everyone needs to know about palliative care

4. Discussion

The quantitative analysis indicated that 32 courses were held in various environments, attracting a total of 343 participants. The courses were primarily aimed at the general public (31.3%), followed closely by health students (28.1%). Evaluations of the courses showed a high satisfaction rate, with 98.4% of participants expressing that they would recommend the course, and 98.8% indicating they had acquired new knowledge. Additionally, most attendees rated the course content as “very good” across all settings.

The qualitative analysis underscored significant insights from participants, focusing on the normalization of conversations about death and the emphasis on dignity during the dying process. Community health workers and favela participants highlighted the importance of preparing for death and honoring personal wishes. Health students and general attendees acknowledged the necessity of dismantling the taboo surrounding death, promoting open dialogue, and ensuring a dignified end-of-life experience. Online participants shared reflections on overcoming fear and viewing death as a natural aspect of life. Across all groups, there was a consistent focus on raising awareness of palliative care and the need for compassionate communication.

The implementation of the course in Brazil showed positive results, indicating its potential to raise awareness about the topic, regardless of the context. The high satisfaction rates and the recognition of the course’s value among different participant groups, both in terms of local context and education, suggest that such initiatives can help break taboos surrounding death and improve the quality of care regarding end-of-life issues.

The findings of this study align with those from research conducted in other countries [

10,

12,

17,

20]. In a similar study conducted with 5,469 participants in a first aid course in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, it was found that 99% found the course content easy to understand, and 99% would recommend the course to others. The overall course rating was ’very good’ [

20].

The online course assessed in this study also received favorable feedback from participants, reinforcing the findings of the previously mentioned study [

16]. This format allows participation from individuals who are unable to attend in person, including caregivers of severely ill patients and as well as from locations that would be difficult to access for attending the course [

16].

Participants, in general, consider the four-hour duration to be sufficient. However, the CHW showed a greater interest in attending a longer course, indicating the need for more education and training for this profession.

The quantitative and qualitative results indicate that the course proposal seems to meet the growing demand for educational strategies in end-of-life care, as outlined in the National Palliative Care Policy. (6) Furthermore, it helps to fill an important gap in strengthening knowledge and practices in this type of care, ensuring a more integrated approach to the needs and demands of end-of-life care [

21].

The LAC was initiated in Brazil in 2020. In addition to community training, efforts were also made to offer courses aimed at training facilitators for the LAC. This initiative contributes to the dissemination of knowledge on this topic, not only for the training of future facilitators but also for the development of individuals across different states in Brazil [

15].

As in other countries, the dissemination of LAC courses in Brazil has primarily occurred through word of mouth [

12,

15]. However, to expand its reach and impact, it is crucial that the course be institutionally integrated into various settings.

The LAC was delivered to 42 CHW, who are key in mediating between the population and the healthcare system. In addition to disseminating essential health information, they facilitate the referral of community needs to the Family Health Strategy. This approach is designed to address territorial, cultural, and social diversity, aligning with the principles of the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) [

22].

Another promising initiative was the implementation of the course in favelas through partnerships with compassionate community projects. The proposal contributes to enhancing the community’s ability to support its members by mobilizing volunteers and expanding the health support network, integrated with primary care services, aiming to reduce disparities in access to palliative care [

9,

23]. Currently, established compassionate communities exist in Rio de Janeiro [

9,

23], Goiânia, São Paulo, and Belo Horizonte, with additional initiatives under development [

9,

23,

24].

The demand for palliative care at home will increase in the coming years [

10,

19]. Additionally, it is important to highlight that there are unique realities in Brazil. Some areas are dominated by drug trafficking or militias and lack basic sanitation. There are regions where access to healthcare facilities is hindered, especially for individuals with mobility challenges and those who are seriously ill [

9,

25]. The disparities in the country are vast in access to healthcare services [

26], and the growing need for home-based care further emphasizes the urgent need for initiatives and strategies focused on community education, such as the LAC.

In Brazil, in addition to occupying positions in the quality of death ranking [

1,

5], we face a challenge in the training process of healthcare professionals. Education on Palliative Care only became mandatory in the medical curriculum in 2023 [

27]. Data collected in 2021 showed that only 44 out of 315 (14%) medical schools registered with the Ministry of Education and Culture offered any type of education on Palliative Care [

28,

29]. In other areas of healthcare professional education, this topic is not mandatory.

5. Limitations

One of the main limitations of the course is the relatively small amount of data collected from certain settings. For example, in the favela and for the CHWs, only 4 and 2 courses were held, respectively. Additionally, all of the settings analyzed were located in the Southeast region of Brazil, which represents just one of the country’s five major regions.

It is also worth noting that not all participants completed the questionnaire (72%), and other opinions could be lacking.

6. Conclusions

The results of the current study indicate that the standardized approach with the normal international LAC curriculum to discuss Palliative Care and care at the end of life can be used in Brazil in different settings and for participants with diverse backgrounds, therefore being a simple/easy tool to raise awareness of Palliative Care in the population.

The feedback from CHWs suggests that these professionals want more information about Palliative Care; benefit from a LAC and this may be an accessible tool to strengthen the National Palliative Care Policy, especially in Primary Health Care.

As an innovative study, the findings show that the LAC model can be expanded and continued, offering significant potential for further implementation and impact in different regions and contexts of Brazil.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Patricia Cury and Karin Schmid; methodology, Patricia Cury, Karin Schmid, Marina Schmidt, Janaina Nascimento; investigation, Karin Schmid; writing—original draft preparation, Karin Schmid.; writing—review and editing, Patricia Cury Marina Schmidt and Janaina Nascimento; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of UERJ (Parecer 7.228.452 of 16.11.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, and the informants had the opportunity to end participation at any time without consequences for them.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in part on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants of the Last Aid courses and workshops, all Last Aid instructors, all our network partners, supporters, and others who have contributed to or supported the project.

Conflicts of Interest

K.S. is the leader of Last Aid in Brazil.

References

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Bhadelia, A.; Goh, C.; Baid, D.; Singh, R.; Bhatnagar, S.; et al. Cross Country Comparison of Expert Assessments of the Quality of Death and Dying 2021. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2022, 63, e419–e429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.; Marques da Silva, C. Palliative care: pathway in primary health care in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 2022, e00130222. [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, J.M.G.; Johnson, F.R.; Finkelstein, E.A. What is a Good Death? A Choice Experiment on Care Indicators for Patients at End of Life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2022, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E, B. What is a good death? A critical discourse policy analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2024, e2546–e2553. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. The 2015 Quality of Death Index. London: 2015.

- BRASIL MdS. PORTARIA GM/MS Nº 3.681, DE 7 DE MAIO DE 2024; Institui a Política Nacional de Cuidados Paliativos - PNCP no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS, por meio da alteração da Portaria de Consolidação GM/MS nº 2, de 28 de setembro de 2017. Brasilia; 2024.

- Torres LF, Oliveira NMSd. Programa educacional em cuidados paliativos para os profissionais de saúde: uma revisão sistemática. Research Society and Development 2022, e18011628885. [Google Scholar]

- Zamarchi, G.; Leitão, B. Estratégias educativas em cuidados paliativos para profissionais da saúde. Revista Bioética 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita MGdR, Silva, Pereira Coelho, Rodrigues Martins, Souza Td, Trotte LAC. Slum compassionate community: expanding access to palliative care in Brazil. Revista de Escola de Enfermagem da USP 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bollig G, Brandt F, Ciurlionis M, Knopf B. Last Aid Course. An Education For All Citizens and an Ingredient of Compassionate Communities. Healthcare 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, Rosenberg, Bollig G, Haberecht. Last Aid and Public Health Palliative Care: Towards the development of personal skills and strengthened community action. Progress in Palliative Care 2020, 28, 343–345. [Google Scholar]

- Bollig G, Neylon S, Niedermann E, Zelko E. The Last Aid Course as Measure for Public Palliative Care Education: Lessons Learned from the Implementation Process in Four Different Countries. 2024 Feb.

- Bollig, G.; Heller, A. The last aid course - A Simple and Effective Concept to. Austin Palliative Care 2016, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bollig, G. Palliative Care für alte und demente Menschen lernen und lehren Berlin, Germany: LIT Verlag; 2010.

- Schmid, K. IMPLANTAÇAO DOS CURSOS DE ULTIMOS SOCORROS NO BRASIL (CDUS)- RELATO DE EXPERIENCIA. 2024 Nov.

- Bollig, G.; Meyer, S.; Knopf, B.; Schmidt, M.; Bauer, E.H. First Experiences with Online Last Aid Courses for Public Palliative Care Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollig, G.; Graef, K.; Gruna, H.; Drexler, D.; Pothmann, R. “We Want to Talk about Death, Dying and Grief and to Learn about End-of-Life Care”—Lessons Learned from a Multi-Center Mixed-Methods Study on Last Aid Courses for Kids and Teens. Children 2024, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollig, G.; Bauer, E.H. Last Aid Courses as measure for public palliative care education for adults and children—a narrative review. Annals of palliative medicine 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance WHO&WHPC. Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life (2nd ed.). 2020.

- Bollig, G.; Kristensen, F.; Wolff, L. Citizens appreciate talking about death and learning end-of-life care – a mixed-methods study on views and experiences of 5469 Last Aid Course participants. Progress in Palliative Care 2021, 29, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.S.M.; Cassavia, M.F.d.C.; Salman, C.S.; Salman, A.A.; Bryan, L.; Oliveira, C.d. National Palliative Care Policy: Challenges of Professional Qualification in Palliative. Rev. Bras. Cancerol. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira FFd Almeida MTPd Ferreira, M.G.; Pinto, I.C.; Amaral, G.G. Importância do agente comunitário de saúde nas ações da Estratégia Saúde da Família: Revisão integrativa. Revista Baiana de Saúde Pública 2022, 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- Silva E, Maia Prates C, da Silva Couto, Costa Oliveira L. Compassionate Community of the Slums of Rocinha and Vidigal: Strategy to Help in Cancer Control. Rev. Bras. Cancerol. 2024, 70, e104714. [Google Scholar]

- Collucci, C. Health Professionals and Residents Bring Palliative Care to Patients in Brazilian Favelas. [Online].; 2024. Available from: HYPERLINK “https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/internacional/en/scienceandhealth/2023/08/health-professionals-and-residents-bring-palliative-care-to-patients-in-brazilian-favelas.shtml” https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/internacional/en/scienceandhealth/2023/08/health-professionals-and-residents-bring-palliative-care-to-patients-in-brazilian-favelas.shtml.

- Minayo MCDS, Constantino P, Mangas RMdN, Pereira TFdS. Experiências de agentes comunitários de saúde com pessoas idosas dependentes e vulneráveis. Revista Pesquisa Qualitativa 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Coube, M.; Nikoloski, Z.; Mrejen, M.; Mossialos, E. Inequalities in unmet need for health care services and medications in Brazil: a decomposition analysis. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL MDE. Alteração da Resolução CNE/CES nº 3, de 20 de junho de 2014, que institui as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Medicina e dá outras providências Brasilia: DOU; 2022.

- Castro, A.; Taquette, S.; Marques, N. Cuidados paliativos: inserção do ensino nas escolas médicas do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 2021, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, Procópio de Moura Mendonça, Terzi C, Zuliani Martin, de Oliveira R, Mota Cruz de Assis Figueiredo MdG, et al. Compartilhando Experiências: Do Ensione de Cuidados Paliativos na Medicina: ANCP; 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).