1. Introduction

Maxillofacial trauma represents a significant global health challenge, encompassing injuries to facial soft and hard tissues that can profoundly impact critical functions like breathing, eating, and speaking [

1,

2]. The worldwide incidence of these injuries places substantial strain on healthcare systems [

3]. While road traffic accidents remain the primary cause of maxillofacial fractures, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [

4], other significant causes include interpersonal violence, falls, sports injuries, and industrial accidents [

5]. The distribution and patterns of these injuries vary geographically, reflecting differences in socioeconomic conditions, cultural factors, and legislative environments [

6]. Management of maxillofacial trauma demands a multidisciplinary approach [

7], with immediate priorities including airway maintenance, hemodynamic stabilization, and hemorrhage control [

8,

9]. These injuries often result in significant functional, aesthetic, and psychological consequences [

10,

11,

12], while also imposing substantial economic burdens through direct healthcare costs and lost productivity [

13,

14]. Prevention strategies are crucial in reducing the global burden of maxillofacial trauma. As highlighted by Siegler and Rogers in their comprehensive analysis of trauma systems, environmental and social factors play a crucial role in trauma prevention. Their work demonstrates how socioeconomic disparities significantly influence both the incidence and outcomes of trauma, particularly in underprivileged areas. Traditional preventive measures include road safety regulations [

15] and public awareness campaigns [

16], but addressing underlying social determinants is equally important. Recent advances in imaging, surgical techniques, and biomaterials have transformed treatment approaches [

17,

18,

19], though significant disparities in access to specialized care persist, particularly in developing regions [

20,

21]. Future research should focus on developing novel treatment strategies, refining outcome assessments, and implementing evidence-based prevention programs [

22,

23].

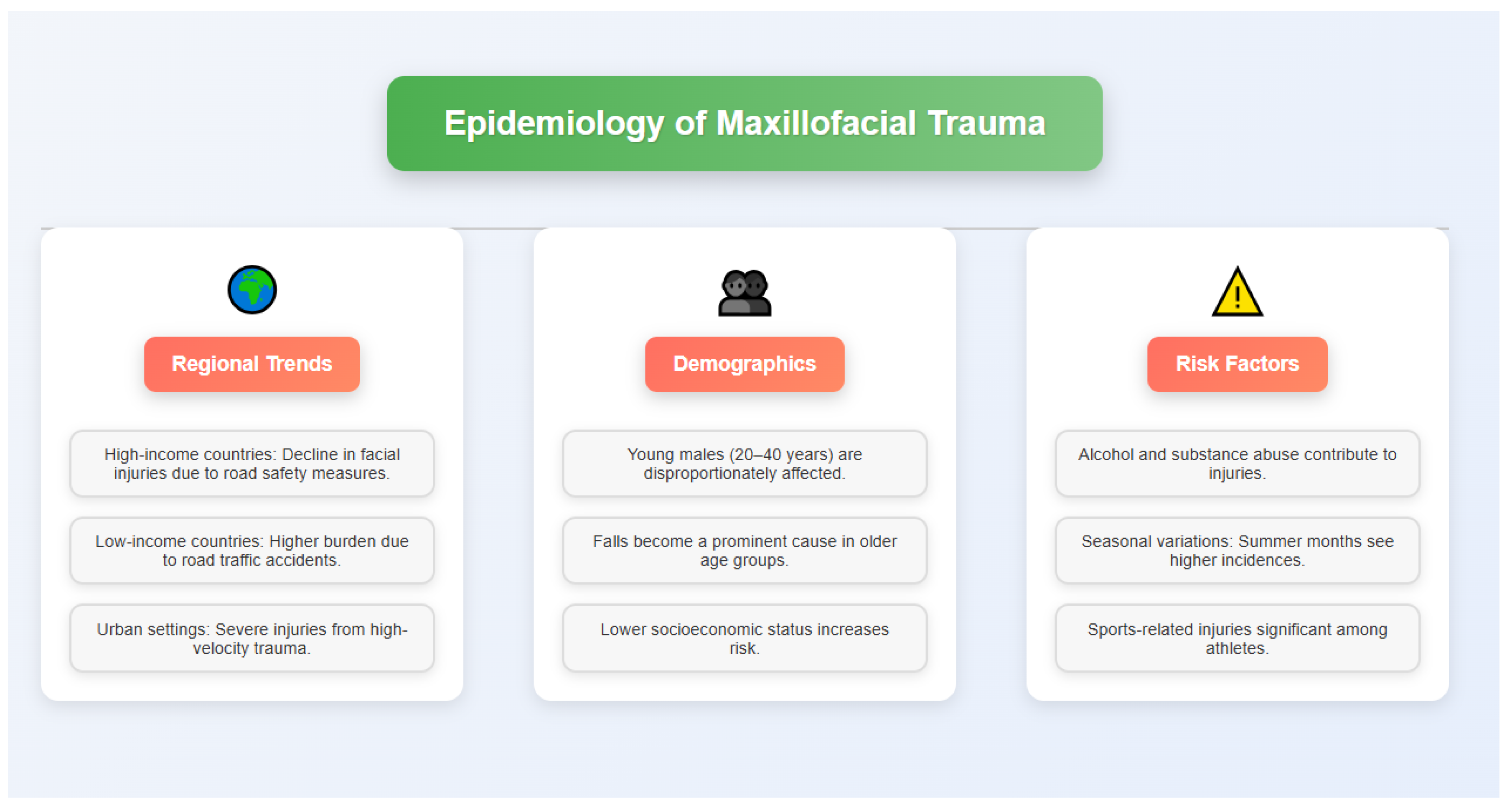

2. Epidemiology

The epidemiology maxillofacial trauma shows vast regional and demographic variations influenced by socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions [

24]. Although worldwide rates of maxillofacial injuries are difficult to ascertain precisely owing to diversity and access of health systems, some evidence suggests that maxillofacial injuries are attributable to trauma in 33 to 50% of cases (a rate that may be influenced by mortality from other types of injuries). Nonetheless, it is estimated that these injuries represent a significant portion of Emergency Department (ED) visits worldwide, with studies indicating facial injuries in as many as 15% of all trauma patients who present to EDs [

25].

Maxillofacial trauma: Geographical distribution indicates the university hospital based differs from those based in general hospitals Although the incidence of severe facial injury has decreased over the last few decades in high-income countries, this is often attributed to improved road safety and stricter regulations [

26]. On the other hand, the burden of maxillofacial trauma persists, particularly associated with RTAs, among low- and middle-income countries. The differences are usually associated with poor infrastructure, lax traffic laws, and a lack of enforcement of safety regulations [

27].

The nephrology demographic has some consistent trends, regionally comparatively. This highlights the need for targeted prevention approaches and preventive programs, especially for young adults, who are majorly affected (especially men aged 20–40) due to their higher degree of risk-taking and occupational exposure [

28]. This age group is at risk, especially for trauma due to RTAs and interpersonal violence. This difference in gender decreases in older age categories, in which falls become the leading cause of facial injuries [

29].

Epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma is influenced by socioeconomic status factors [

30]. It is often lower socioeconomic status is connected to a greater facial injury risk, which might be due to factors such as living and working under dangerous conditions, less access to protective equipment and also more occurrences of inter-personal violence in the poor areas [

30]. Moreover, alcohol and substance abuse may be major risk factors for RTAs and interpersonal violence that causes facial injuries [

31].

Maxillofacial injuries vary internationally and temporally in aspect and degree. In city environments, the higher-velocity trauma associated with vehicular injuries leads to a greater incidence of severe and complex facial fractures compared to those seen in rural settings where lower-velocity injuries sustained from falls or animal attacks are more common [

32] (

Figure 1).

Seasonal variation has been observed in some regions with increased cases in summer months or holiday times, potentially due to higher outdoor activity and increased alcohol consumption [

33].

Maxillofacial sports injuries have a different epidemiological pattern. Although they represent a smaller share of the total head and neck injuries than other causes such as road traffic accidents or interpersonal violence, they are prominent in particular demographics, especially in younger athletes. Depending on the sporting activity, these injuries differ greatly; with sports entailing physical contact (e.g., boxing, rugby, and ice hockey) having a stronger association with facial fractures and dental injuries [

34].

Occupational maxillofacial trauma is not as common as that associated with either road traffic accidents or interpersonal violence but may represent an important problem from the perspective of certain industries. The construction, manufacturing, and agricultural sectors have the highest incidences of facial injuries and are typically caused by falling, striking objects, or machinery. The introduction of safety guidelines for employees, as well as personal protective equipment, has helped reduce the incidence and severity of these injuries in many countries [

35].

Maxillofacial trauma epidemiology within the context of war and natural disasters. In these environments, the rate of high-severity facial injuries typically rises sharply, with an increased proportion of penetrative injuries sustained by projectiles or blast forces. These injuries are more complex due to limited healthcare resources and challenging evacuation conditions [

36].

The epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma has also been affected by recent global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Road traffic accidents and sports-related injuries reduced temporarily during lockdown measures imposed by several countries. On the other hand, certain regions observed a surge in facial injuries related to domestic violence, suggesting a nuanced relationship between social dynamics and injury trends [

37].

The knowledge of maxillofacial trauma epidemiology will help to shape standard preventive measures and appropriate health care resourcing. It guides policymaking about road safety, violence prevention programs, and occupational safety legislation. Furthermore, understanding the demographic and geographic trends of these injuries can inform the design of primary prevention strategies and the planning of specialized maxillofacial trauma care services [

38].

3. Etiology

Maxillofacial trauma has variable etiology, and the circumstances surrounding this variety often depend on socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental factors of different geographic areas. Understanding these causes is crucial for determining prevention and treatment methods.

RTAs remain the most common cause of maxillofacial injuries in many parts of the world, especially in developing countries [

39]. Factors such as poor road infrastructure, lax traffic laws, and inadequate safety enforcement contribute to high RTA-associated facial trauma. The probability of serious maxillofacial injuries due to RTAs is especially high in urban settings with dense populations and heavy vehicular traffic.

Another significant cause of maxillofacial trauma is interpersonal violence, which varies widely between societies and cultural groups [

40]. Alcohol and substance abuse, socioeconomic disparities, and cultural norms contribute to violence-related facial injuries. In certain areas, domestic violence has emerged as a prominent subset of interpersonal violence, making it particularly difficult to report and intervene upon [

41].

Falls in elderly and young patients represent a significant proportion of maxillofacial trauma. The increasing elderly population in many countries has contributed to a rise in fall-associated facial injuries, often complicated by comorbid conditions and anticoagulant drug use [

42]. In pediatric populations, falls from height, playground accidents, and home accidents play a major role in facial trauma etiology, requiring special management due to the unique anatomical and physiological characteristics of the growing facial skeleton [

43].

Another distinct etiological category is sports-related maxillofacial injuries. Although less frequent than RTAs or interpersonal violence, contact sports like boxing, rugby, and ice hockey carry a higher risk for facial fractures and dental injuries. The rise in such cases may also be attributed to the growing popularity of extreme sports [

44]. Sports-related facial trauma differs in nature from other mechanisms, with an increased proportion of isolated fractures and soft tissue injuries.

Maxillofacial trauma due to occupational hazards remains common, particularly in the construction and industrial sectors. Despite improvements in workplace safety regulations, accidents involving machinery, falling objects, and high-energy impacts continue to be a major cause of facial injuries in specific professions [

45]. The types and severity of these injuries are largely dependent on the work environment and adherence to safety protocols.

The etiology of maxillofacial trauma takes on unique characteristics in conflict zones and natural disaster-affected areas. Injuries from explosions, gunshots, and collapsing structures create complex patterns of facial trauma requiring specialized management approaches [

46]. Reconstruction and rehabilitation in these scenarios present additional challenges due to the severity of both hard and soft tissue injuries.

Although less common in urban settings, animal-related injuries remain a significant cause of maxillofacial trauma in rural and agricultural communities. These injuries, caused by livestock, wild animals, or even dog attacks, can result in severe facial lacerations, crush injuries, and fractures [

47]. Management often involves zoonotic infection control and specialized wound care protocols.

Alcohol and substance abuse play a crucial role in maxillofacial trauma, as they are strong contributors to RTAs and interpersonal violence. Studies have shown that a large proportion of patients presenting with facial injuries in emergency departments are intoxicated or under the influence of drugs [

48]. This highlights the importance of integrating substance abuse prevention and treatment programs into maxillofacial injury reduction strategies.

Emerging trends in lifestyle and technology have introduced new etiological factors. The increasing use of personal mobility devices (PMDs), such as electric scooters, has led to a rise in urban facial injuries [

49]. Additionally, distracted driving and even distracted walking due to mobile device use have contributed to new patterns of maxillofacial trauma.

Understanding the various factors contributing to maxillofacial injuries provides insight into the complex interplay between human behavior and environmental conditions. This knowledge informs the development of more effective prevention and management strategies, shaping public health policies, guiding healthcare resource distribution, and influencing safety measures across various sectors.

Identifying the mechanisms behind different types of facial trauma not only aids clinicians in recognizing complications but also helps in planning treatment strategies specific to each injury type. As the global landscape evolves, so too will the etiological factors of maxillofacial trauma. Emerging influences, such as extreme weather events related to climate change, demographic shifts, and technological advancements, may introduce new causes or replace existing ones. Monitoring and responding to these trends will be vital in ensuring that prevention strategies and therapeutic approaches remain aligned with the evolving needs of affected populations worldwide.

4. Common Maxillofacial Injuries

Maxillofacial trauma is a broad term that involves injury to the soft tissues, bones, and dentition of the face and associated structures. Due to the intricate anatomy of the facial region along with the importance from both functional and aesthetic perspectives, it is important to be aware of the different varieties of injuries that can happen.

4.1. Soft Tissue Injuries

Soft tissue injuries are one of the frequent presentations of maxillofacial trauma, ranging from small abrasions to deep lacerations and avulsions [

50]. These injuries may involve the skin, subcutaneous tissues, muscles, and neurovascular structures of the face. They are of particular concern because they may scar and impair function.

The rich vascular supply of the face often causes profuse bleeding from minor wounds, and prompt treatment is required [

51]. Facial contusions and hematomas are commonly seen in blunt trauma, with their presentation depending on the impacted force as well as the type of tissue involved.

Injuries involving eyelids, lips, and nose receive special consideration due to their functional importance and aesthetic sensitivity [

52]. Soft tissue injuries can also involve deeper structures, such as the parotid gland and duct, branches of the facial nerve, or the lacrimal apparatus, all of which require unique management strategies.

4.2. Facial Bone Fractures

Maxillofacial trauma injuries vary in complexity in an upward direction and can be as devastating as the functional disturbances they create, often imperfectly causing proper aesthetic arrangements of facial components. The configuration and extent of fractures are dictated by the mechanism of injury, impact force, and the intrinsic strength of facial skeletal elements [

53].

Mandibular fractures are the most common fractures of facial bones, the location and pattern of which dictate the method of treatment. Particularly for condylar fractures, careful analysis is needed regarding the temporal aspects of joint function [

54].

Midface fractures, such as Le Fort fractures, zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures, and orbital fractures, have unique diagnostic and management challenges [

55]. The concept of facial skeleton reconstruction buttresses is seminal for the treatment of these injuries.

Although nasal bone fractures are often viewed as less severe, if not properly managed, they can result in major functional and aesthetic concerns. They are highly common due to the position and relative fragility of the nasal bones [

56].

Frontal sinus fractures, while infrequent, are particularly concerning because of the proximity of the frontal sinuses to the intracranial structures and the long-term complications like mucocele formation or meningitis [

57].

4.3. Dental and Alveolar Injuries

Dental trauma is a common aspect of maxillofacial injuries ranging from uncomplicated crown fractures to total avulsion of the teeth. The treatment of these injuries is not only aimed at restoring the functionality of the teeth, quickly, but also addresses the long-term health of the dentition [

58].

The alveolar process is frequently fractured/absent in dental injuries and plays an important role in the stability and prognosis of affected teeth. Root fractures, lateral luxation, subluxation and extrusion all necessitate intervention for optimal outcomes. However, this situation emphasizes the importance of public education in the immediate provisional management of tooth avulsion [

59].

Stepwise cortical fracture of mandible: Long-term sequel of dental intion and facial growth in children.

4.4. Associated Injuries

Injuries of related structures are common with maxillofacial trauma, and patient assessment and treatment should be broad based. Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are another leading concern, as the direct link between the face and cranial cavity allows for force to be easily transverted to depths of the cranial vault [

60]. Here, we observed that the risk of TBI increases with the severity of the facial trauma, supporting the observation that the presence of facial fractures has been linked with an increased risk of TBI and a more severe injury overall and highlighting the need for entire facial traumas to be neurophysiologically assessed.

Although less frequently observed, cervical spine injuries need to be evaluated as part of the initial assessment of maxillofacial trauma. The mechanism of injury behind facial trauma often includes forces that can compromise the cervical spine, and warrant adequate immobilization and evaluation protocols [

61].

Ocular trauma can range from a mild contusion to a rupture of the globe, and management will frequently require an interdisciplinary approach, including input from an ophthalmologist. High-energy impacts can occasionally exceed the protective function of the orbital bones resulting in direct ocular trauma [

62].

When we think of maxillofacial trauma resulting in airway compromise, however, we typically think of maxillofacial trauma resulting in airway compromise. Studies also underline that airway management is the top priority in such scenarios, and may demand advanced procedures like surgical airway establishment [

63].

Knowledge of the various types of maxillofacial injuries and their possible associations is important for the diagnosis, treatment planning, and multidisciplinary management. The need for holistic management of maxillofacial trauma combines the goal of restoring function and aesthetics due to the complex interaction between soft tissue injury, facial bone fractures, dentoalveolar injuries, and associated injuries.

5. Economic Impact

The costs of maxillofacial trauma are not limited to acute particular care alone but are extensive in terms of direct and indirect responses to trauma on an economic scale (

Table 1). It is important to know the economics of these injuries to formulate prevention strategies, allocate resources availing health care and apply treatment modalities judiciously.

5.1. Healthcare Costs

Maxillofacial trauma is estimated to have significant direct healthcare costs due to the complex nature of these injuries and the multidisciplinary approach often required for their management, and costs have an important impact on health system budgeting. A large part of these costs can be attributed to initial emergency department visits, diagnostic imaging, surgical interventions and hospitalization [

64].

Costs can range anywhere from simple emergency repair to long-term medical care when multiple facial fractures or associated injuries are involved that require extensive surgical procedures and hospital stays. Advanced imaging techniques, including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), although necessary for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning, add considerably to the total cost of care [

65].

Additionally, it places a significant financial burden on the patients in need of specialized equipment and materials such as plates, screws, and other fixation devices in maxillofacial surgery. For example, in cases that require urgent surgery, the cost of operating rooms, anesthesia, and post-operative treatment in intensive care settings may significantly impact total spending on healthcare [

66].

Furthermore, treating complications like infections, malunion, or revision surgeries can impose unexpected added costs. Because maxillofacial trauma is more enduring, requiring frequent follow-up visits, imaging studies, and potential secondary procedures, cumulative costs of healthcare tend to increase over time [

67].

A further cost for those sustaining extensive dental and alveolar injuries includes dental rehabilitation with prosthetic replacements and implants.

5.2. Loss of Productivity

Maxillofacial trauma also has a significant impact on productivity, contributing to this economic burden, particularly as the effects can persist long beyond the initial recovery phase. When patients are hospitalized and need time off work or school during recovery, this is a direct loss of productivity by those individuals, which, in turn, contributes to loss of productivity in the economy as a whole [

68].

The duration of work absence can be greatly affected by both the severity and nature of facial injuries. It can be assumed that complex fractures or necessitating extensive surgical reconstruction will lead to prolonged periods of disability with significant loss of income for the affected individuals as well as reduced economic output for the employer [

69].

For example, maxillofacial trauma leading to chronic disfigurement or loss of function can affect long-term employability and work advancement. This can result in decreased earning capacity throughout the life of the individual, reinforcing the negative economic impact of the initial injury [

70].

Even after the physical recuperation, the psychological sequelae in the form of PTSD or depression can also lead to impaired productivity and reduced work performance [

71]. These mental health sequelae may require more time off work for treatment and may impact long-term career prospects.

5.3. Rehabilitation Expenses

Rehabilitation after maxillofacial trauma is usually long and complex, requiring different types of therapy and interventions, leading to high costs. For temporomandibular joint injuries or facial nerve function related cases, physical therapy may be necessary for longer durations [

72].

Often patients receiving extensive oral or maxillofacial surgery, especially palatal or mandibular reconstruction, require speech therapy. The expense of rehabilitation can vary widely depending on the duration and intensity of these therapies [

73].

Psychological support and counseling are another important part of rehabilitation, as facial injuries can take a severe emotional and psychological toll. The prices for mental health services on a long basis can escalate, especially in cases of extreme disfigured or traumatic events [

74].

Prosthetic rehabilitation, which can involve facial prostheses for patients with wide loss of tissue, dental implants, and other restorative procedures, represents a large share of rehabilitation costs. Although necessary to restore function or aesthetics, these interventions are often associated with significant material and professional costs [

75].

Long-term rehabilitation costs are compounded by the need for ongoing medical management, such as pain management, scar revision techniques and treatment of chronic conditions stemming from the original trauma. Such costs are potentially spanning many years or even a lifetime [

76].

6. Prevention Strategies

Maxillofacial trauma prevention is not a simple endeavor, but rather a complex approach addressing multiple causes and mechanisms of injury. The personal, societal, and economic burdens associated with facial injuries may be addressed through implementation of effective prevention strategies that will help minimize occurrence and severity of injury to the facial region. These preventive measures will only be effective if all stakeholders, including policymakers, healthcare professionals, law enforcement agencies, and the public, work together.

6.1. Road Safety Measures

As road traffic accidents rank as a foremost cause of maxillofacial injuries, measures to significantly enhance road safety need implementation and enforcement. Primary seat belt laws have been associated with a decrease in incidence and severity of facial injury in motor vehicle crashes [

77].

In a similar regard, the presence of airbags in high-impact collisions has similarly been shown to reduce the overall severity of facial injuries, despite its potential to cause minor injuries to the midface [

78].

The helmet, when it comes to motorcyclists and cyclists, is one of the most important aspects. Their advantage over open-face designs is especially pronounced in providing maxillofacial protection such as facial fractures and soft tissue injuries [

79].

Many jurisdictions have achieved a significant number of helmet uses and reduction in facial trauma as a result of legislation mandating helmet usage and public education campaigns in place. Better infrastructure, such as traffic calming interventions in cities and separation of pedestrian and vehicle traffic, can lead to fewer accidents involving vulnerable road users [

80].

Moreover, the evolution of safety features in cars, like collision avoidance systems and better crumple zones, greatly reduces crash force during accidents.

6.2. Violence Prevention Programs

A significant proportion of the maxillofacial trauma is associated with interpersonal violence, which calls for vigorous violence prevention programs.

Community-based interventions for high-risk groups have been proved effective in preventing assault-related facial trauma [

81].

Conflict resolution training, anger management classes, and mentorship programs are parts of these programs (

Figure 2).

To truly make a difference to violence, we need to address the key factors that drive violence – social inequality, substance abuse, mental health problems, etc.

A more holistic approach to violence prevention can be provided by law enforcement working with social services and healthcare providers [

82].

Domestic violence predominantly leading to facial trauma, and highlight how screening protocols in health care settings can address this issue.

Support services for victims and legal measures, alongside rehabilitation programs for perpetrators [

83], are integral components in domestic violence prevention approaches.

6.3. Occupational Safety Regulations

The work-related maxillofacial trauma has been documented in many industries, notably construction, manufacture, and agriculture, which require occupational health and safety regulations to be in place. Mandatory PPE including face shields and helmets in high-risk environments reduced the incidence of facial trauma [

84].

Routine safety training efforts for safe handling of equipment and identification of hazards is key to prevention of occupational injuries. Initiatives such as machine guarding and fall protection measures can help to limit the rates of injury to the facial region that occurs in industrial settings [

85].

Use of proper protective equipment is critical in preventing sports-related maxillofacial injury. In contact sports, mouthguards and face masks have been shown to reduce dental and facial injuries [

86]. Other critical measures include enforcing rules against dangerous play and educating athletes about injury risks and how to prevent them.

6.4. Awareness Raising Campaigns

The importance of public education in preventing maxillofacial trauma. Behavior modification and injury prevention through awareness campaigns against specific risk factors and risk groups are effective. These campaigns should be conducted through various media, including social media [

87].

Education about the impact of dangerous behaviors (think drunk driving, or violence) can help dissuade them. Effective public health campaigns encouraging the use of protective equipment further encourage compliance and decrease risk of injury in sports and recreation [

88]. Education regarding the initial management of dental and facial trauma can disperse a lot of initial unnecessary panic and may allow for better outcomes. For example, public awareness of the correct tooth preservation methods after avulsion can significantly improve the likelihood of successful reimplantation [

89].

For example, as discussed in the context of child safety, educating parents/caregivers about household hazards and child proofing may reduce the incidence of many facial injuries in young children. Recognizing the importance of car seats and educating parents on correct installation may also help to decrease injury in children from motor vehicle collisions [

90].

The execution of these preventive measures needs to be a joint effort across various sectors. Legislation — like stricter regulations against drunk driving or mandatory helmet use — lays the groundwork for enforcement. But the real success of such initiatives comes from public compliance as well as community involvement.

Ongoing research on injury patterns, risk factors, and the effectiveness of prevention strategies is critical to hone and adapt these measures as necessary as things evolve. Identifying and targeting the underlying factors contributing to maxillofacial injuries, as well as leveraging data to implement evidence-based interventions, could have a considerable impact in decreasing the burden of these injuries and ultimately, enhancing public health and relieving the economic strain on healthcare systems and society.

7. Surgical Management

Surgical intervention for maxillofacial trauma is a dynamic adaptable field that demands a thorough knowledge of facial anatomy, biomechanics, and aesthetic principles. The aims of surgical intervention are threefold: to improve and/or preserve function, to prevent complications, and to maximize long-term outcomes. Surgical management varies, based on injury type and severity as well as patient factors.

7.1. Timing of Interventions

Timing of surgical intervention in maxillofacial trauma is crucial which is tempered by specific injury pattern and regional injuries. For patients with isolated facial fractures in which there is no substantial soft tissue compromise, early definitive management within 72 hours of injury is usually preferred [

91]. This phenomenon, termed as early definitive care, avoids loss of functional fracture reduction and fixation (due to edema and fibrosis) later.

In patients with multiple moderate or major trauma, or patients who need critical care management, however, a delayed approach may be necessary. The damage control surgery principles that were designed for the management of abdominal trauma have been translated for use in maxillofacial injury [

92]. This includes initial stabilization and control of life-threatening conditions, followed by definitive reconstruction once the patient’s overall condition stabilizes.

In the case of complex panfacial fractures, a systematic approach towards surgical timing and sequencing is critical. Restoration of the mandibular arch is typically handled first [

93]. The goals of this process is to begin with functional appropriateness of the teeth so they have a consistent occlusion and facial width that becomes the foundation for rebuilding over.

7.2. Surgical Approaches

In maxillofacial trauma, the decision of approach is influenced by the need to provide a sufficient amount of exposure necessary for fracture reduction and fixation whilst avoiding aesthetic compromise and functional impairment. With the improvement in the technique of surgery, there is demand for minimally invasive techniques as much as possible using the pre-existing scars or natural wrinkles of the skin when possible [

94].

Intraoral approaches are most commonly used to avoid visible scarring for mandibular fractures. External fixation may, however, be warranted in the setting of more complex or comminuted fractures (particularly those involving the condyle or ramus) [

95]. Endoscopic-assisted approaches have been utilized for the management of subcondylar fractures, providing enhanced visualization with minimal external incisions [

96].

The coronal approach is relatively versatile for accessing the upper and middle thirds of the face in midface trauma. Nevertheless, less traumatic procedures like the transconjunctival route for the orbital floor fractures and the sublabial approach for maxillary fractures have gained much attention by virtue of less nuisance and better aesthetic outcomes [

97].

7.3. Reconstruction Techniques

In reconstructing maxillofacial injuries, solutions must be addressed for both bony and soft tissue defects, often utilizing combination techniques. Fixation methods are guided by load-sharing and load-bearing osteosynthesis, which are principles of craniofacial fixation [

98]. Advances in plating systems and the emergence of resorbable materials have provided surgeons with multiple options.

The use of custom-made stay patient-specific implants (PSIs) for reconstruction has revolutionized the management of complex orbital fractures. These implants are designed to restore orbital volume and contour and are often manufactured via computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technology [

99]. Likewise, the accuracy of mandibular reconstruction, especially free fibula flaps, has been enhanced by virtual surgical planning and three-dimensional printing technologies [

100].

Reconstruction of soft tissue defects during maxillofacial trauma happens through local and regional flaps in smaller defects and microvascular free tissue transfer in wide tissue loss. The design and placement of flaps are directed according to the concept of facial subunit reconstruction to ensure optimal aesthetic results [

101]. Fat grafting techniques have been refined over the years and have served as a new tool for volume restoration and contouring in the late period of breast reconstruction [

102].

Panfacial fractures are difficult to maintain due to restoration of facial buttress anatomy. Fracture repair is sequenced, usually starting with restoration of the outer facial frame (mandible and zygoma) before central midface structures [

103]. The use of computer-assisted navigation systems has also improved the accuracy of outcomes of reduction and fixation in such complex cases [

104].

For patients with extensive tissue defects or for whom primary reconstruction is not possible, facial transplantation has become a pioneering solution. Facial transplantation is still an experimental procedure, however, it dominates the key-advanced treatment for restoration of both shape and function of selected patients with horrific facial traumas [

105].

Technologies like virtual surgical planning, 3D printing of patient-specific implants, and computer-assisted navigation are progressively incorporated into the surgical workflows, improving the precision and predictability of the results [

106]. Moreover, due to the advances of tissue engineering-related methods and regenerative medicine concepts, more effective soft tissue reconstruction and bone regeneration will be possible [

107].

8. Complications and Long-Term Outcomes

Maxillofacial trauma is a heterogeneous entity, and although, with improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative management, complication rates have dropped, these still exist. Complications can be immediate and postoperative, but also structural in terms of long-standing gagging functional and psychological sequelae ranging. Early recognition of and anticipation of possible complications is paramount for best patient care and optimizing outcomes.

8.1. Immediate Complications

The immediate complications of maxillofacial trauma surgery can be classified into infectious, vascular, and neurological complications. Infection is always a worry, especially with compound fractures and poor soft tissue coverage. The rate of postoperative infections after maxillofacial trauma varies from 3% to 33%, depending on injury severity and treatment modality used [

108]. However, the risk of infection can be minimized by proper wound care, adequate antibiotic prophylaxis, and precise surgical technique.

Less common but potentially serious are vascular complications. These treatment-associated complications consist of hematoma formation with potential airway compromise in extreme cases and are most commonly seen in the environment of the neck and floor of mouth [

109]. Postoperative monitoring of the kidneys with rapid response underlies management for these complicating issues. Caution should be used while entering the compartment to avoid facial nerve injury, skin burn, or pseudoaneurysm formation, although pseudoaneurysms of the facial artery or other branches of external carotid artery are rare and require either endovascular or surgical management [

110].

Neurological complications primarily include damage to cranial nerves, especially the facial nerve, in temporal bone fractures or parotid region trauma. The prevalence of facial nerve injury is reported to be between 7% and 10% in cases of temporal bone fractures [

111]. Early identification and appropriate treatment, including surgical exploration and possible nerve repair, are essential for optimizing outcomes.

8.2. Long-Term Functional Disability

Functional disabilities that are associated with maxillofacial trauma have a large impact on quality of life in patients. Malocclusion is one of the most common sequelae, particularly after mandibular or maxillary fracture. The incidence of such an event after trauma has been reported as high as 3% to 25%, dependent on fracture type and treatment modality [

112]. Severe malocclusion unresponsive to orthodontics may require secondary orthognathic surgery.

TMJ dysfunction is another potential long-term complication of condylar fractures. TMJ-related symptoms such as pain, limited mouth opening, and clicking or popping sounds have been mentioned in up to 30% of condylar fracture patients [

113]. Conservative treatment using physical therapy and occlusal splints is used initially and can be successful, with surgical intervention required in intractable cases.

Orbital fractures or optic nerve injuries resultant of orbital fracture can cause visual impairment. Although refinements in surgical techniques have decreased the incidence of post-traumatic enophthalmos and diplopia, it remains an important concern in complex orbital fractures [

114]. These issues may be managed with regular ophthalmic follow-up and possible corrective surgery.

Nasal airway obstruction is a frequent long-term sequelae of nasal and nasoethmoid complex fractures. These are commonly reported in 40% of the patients, complaining of nasal obstruction or difficulty in breathing [

115]. It should be noted that secondary septorhinoplasty is sometimes needed to correct functional and cosmetic problems.

8.3. Psychological Impact

The psychological burden of maxillofacial trauma is an oversimplified problem in patient management. In fact, the growing visibility of facial trauma can have a significant impact on body image, self-esteem, and social interaction. The incidence of PTSD in patients who sustained facial trauma, as confirmed in the study by Sinha et al., was as high as 27% in the first year after injury [

116]. Functional impairment and facial disfigurement were associated with more marked PTSD symptoms.

Maxillofacial trauma patients frequently experience depression and anxiety as well, with rates in the literature varying between 20% and 40% [

117]. These mental health problems can last long after the body has healed and may be detrimental to the affected individual’s quality of life and social integration. The psychological effect goes well beyond the patient to their family and caregivers. According to previous studies, relatives of patients with major facial injuries are often found to have elevated levels of emotional distress that necessitate support and counseling [

118].

Early identification of patients at high risk for psychological complications is critical. Screening such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) can help identify patients who could benefit from psychological intervention [

119]. In patients with facial trauma, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been effective in treating PTSD and depression [

120]. For patients who may be dealing with the psychological effects of their injuries, support groups and peer counseling programs can be helpful in gaining emotional support and coping strategies.

In maxillofacial trauma surgery, the goal of aesthetic results often reflects the auxiliary effects of facial appearance on social interaction and self-image. Although functional restoration is the main objective, the patients' psychological restitutio ad integrum and satisfaction with the treatment results significantly depend on aesthetic detail [

121].

9. Economic Impact

Maxillofacial trauma is not only serious for any individual but it has a wider angle of impact especially on economic concern. It is essential for healthcare system planners, healthcare policymakers, understanding the economic burden, resource allocation, and strategies to reduce excesses of financial burden.

9.1. Healthcare Costs

Maxillofacial trauma is associated with significant direct healthcare costs that can vary greatly depending on the severity of injury, treatment modality and geographic location. A study by Allareddy et al. screened nationwide data in the United States and showed that the average burden of patients with facial fractures was

$55,385 per hospitalization and

$1.06 billion annually [

122].

Indeed, patients with surgical intervention had much higher costs than those treated conservatively. Maxillofacial injuries are seen as some of the most complex injuries due to the anatomical situation and the involvement of different organs and parts of the human body, which commonly require a multidisciplinary approach among oral and maxillofacial surgeons, plastic surgeons, neurosurgeons, and ophthalmologists.

Although critical to achieving the best possible outcomes for cancer patients, this holistic approach carries a cost. A study by Saperi et al. in Malaysia [

123], found that the average cost for treating a maxillofacial trauma patient was

$1,251 with surgical cases costing an average of

$1,716 and non-surgical cases

$805.

Also, extensive follow-up and possible subsequent procedures add greatly to overall healthcare expenses. Chiang et al. ensured that complex facial fractures often led to multi-surged results over years, which could amass costs well over 200,000 dollars per patient in the worst case scenario [

124].

9.2. Loss of Productivity

Direct costs of health care are not the only factors contributing to the economic impact of maxillofacial trauma; there are also drastic loss of productivity factors. Such injury results in long-term disability whereby a person does not attend work for long periods of time and has also high indirect costs on both individual and societal levels.

A study by Bruns et al. analyzed both coverage of East Kentucky by Medicaid as well as overall economic impact and reported that the average days lost to work were 11.8 days per episode 90 and that the total annual lost productivity in Kentucky from facial fractures was estimated to be

$149.9 million [

125].

It also noted that younger patients, who make up a large percentage of maxillofacial trauma cases, were responsible for a disproportionate amount of these productivity losses. The long-term effects of work can lead to a loss of income and earning potential, especially if the injury is serious or permanent.

Kellman and Rosenberg documented that 30% of patients, particularly those with severe facial injuries, were unemployed or underemployed long after their injuries [

126]. In addition to this, maxillofacial trauma can also be associated with psychological sequelae that have led to diminished productivity.

Glynn et al. Patients with PTSD after facial injury had a significantly higher risk of difficulty returning to or retaining work compared to those without PTSD [

127].

9.3. Rehabilitation Expenses

Maxillofacial trauma reveals the need of a multidisciplinary approach of rehabilitation, like physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy and psychological counseling as well. Moreover, the needs for ongoing rehabilitation are significant and form a large part of the entire economic burden of maxillofacial injuries.

A study by Sanchez et al. reported rehabilitation costs specifically related to facial trauma and determined the average number of outpatient therapy sessions was 22 over a 6-month period with a cost of

$3800 per patient [

128]. The study found that patients with both traumatic brain injury and head and neck lesions required as much as

$12,000 of rehabilitation over the same time period.

Another high-cost aspect of maxillofacial trauma cases is dental rehabilitation. All these may cost you a fortune in dental implants, prosthetics, and follow-up dental treatment. Girotto et al. average cost of dental rehabilitation following severe maxillofacial trauma was

$18,000 per patient, with some complex cases exceeding

$50,000 [

129].

Especially for severe injury or disability, the need for assistive devices and home modifications can add to the cost of rehabilitation. Transitional and indirect costs, while less commonly addressed in discussions of maxillofacial trauma, may be considerable for patients suffering from any concurrent injuries and those with long-term functional impairments.

A large portion of patients with maxillofacial trauma are uninsured or underinsured, which adds to the existing economic burden. A study by Allareddy et al. 22.4% of patients presenting with facial fractures were found to be uninsured, resulting in an increased financial burden to both patients and healthcare institutions [

130].

Given these immense economic ramifications, there has been a focus on injury prevention as a potential inexpensive method of decreasing the load of maxillofacial trauma. Employing tactics including increased enforcement of traffic laws, encouraging the use of protective equipment in sports, and workplace regulations all have shown potential for decreasing the incidence and severity of facial injuries [

131].

Moreover, the importance of a multifaceted rehabilitation approach, addressing both physical and psychosocial needs during recovery, is gaining recognition. Maxillofacial trauma can lead to better outcomes and reduced long-term costs with early intervention and coordinated care [

132].

10. Conclusions

Maxillofacial trauma remains a significant global health challenge, with far-reaching physical, psychological, and socioeconomic consequences. Addressing this issue requires a multifaceted approach that encompasses improved prevention strategies, enhanced access to specialized care, and the development of innovative treatment modalities.

Future directions in maxillofacial trauma management should focus on leveraging advanced technologies, such as 3D printing and virtual surgical planning, to optimize surgical outcomes and reduce recovery times. Additionally, efforts should be made to bridge the global disparities in care through international collaborations, telemedicine initiatives, and targeted training programs for healthcare providers in resource-limited settings.

Ultimately, a comprehensive and coordinated approach involving healthcare professionals, policymakers, and community stakeholders will be essential to reduce the incidence and impact of maxillofacial trauma worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and L.L.V.; methodology, A.M.; software, M.L.; validation, A.M., L.V., and J.L.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, S.R. and L.L.; resources, D.S.P.; data curation, C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M., M.L., and L.V.; writing—review and editing, F.M.R. and M.S.; visualization, L.L.V.; supervision, A.M. and L.L.V.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, F.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gassner, R.; Tuli, T.; Hächl, O.; Rudisch, A.; Ulmer, H. Cranio-maxillofacial trauma: a 10 year review of 9543 cases with 21067 injuries. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2003, 31, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.; Holmes, S. (2014). Atlas of operative maxillofacial trauma surgery: primary repair of facial injuries. Springer.

- Boffano, P.; Roccia, F.; Zavattero, E.; Dediol, E.; Uglešić, V.; Kovačič, Ž.; Vesnaver, A.; Konstantinović, V.S.; Petrović, M.; Stephens, J.; et al. European Maxillofacial Trauma (EURMAT) project: A multicentre and prospective study. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2015, 43, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singaram, M.; G, S.V.; Udhayakumar, R.K. Prevalence, pattern, etiology, and management of maxillofacial trauma in a developing country: a retrospective study. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 42, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allareddy, V.; Allareddy, V.; Nalliah, R.P. Epidemiology of facial fracture injuries. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2011, 69, 2613–2618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mijiti, A.; Ling, W.; Tuerdi, M.; Maimaiti, A.; Tuerxun, J.; Tao, Y.Z.; Saimaiti, A.; Moming, A. Epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures treated at a university hospital, Xinjiang, China: A 5-year retrospective study. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2014, 42, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, A.; Doherty, T.; Lewen, G. Facial Fractures and Concomitant Injuries in Trauma Patients. Laryngoscope 2003, 113, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.; Morris, C. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) and facial trauma: can one size fit all? Part 2: ATLS, maxillofacial injuries and airway management dilemmas. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2008, 37, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Czerwinski, M.; Parker, W.L.; Chehade, A.; Williams, H.B. Identification of mandibular fractures: a comparison of two techniques. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2009, 124, 1801–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, E.; Degutis, L.; Pruzinsky, T.; Shin, J.; Persing, J.A. Quality of life and facial trauma: psychological and body image effects. Annals of Plastic Surgery 2005, 54, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Girotto, J.A.; MacKenzie, E.; Fowler, C.; Redett, R.; Robertson, B.; Manson, P.N. Long-Term Physical Impairment and Functional Outcomes after Complex Facial Fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001, 108, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Ahmed, M.; Walton, G.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Hoffman, G.R. The association between depression and anxiety disorders following facial trauma—A comparative study. Injury 2010, 41, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, V.; Glynn, S.; Brown, K.E. Psychosocial sequelae and correlates of orofacial injury. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2004, 47, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mock, C.N.; Donkor, P.; Gawande, A.; Jamison, D.T.; Kruk, M.E.; Debas, H.T. Essential surgery: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet 2015, 385, 2209–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peden, M.; Scurfield, R.; Sleet, D.; Mohan, D.; Hyder, A.A.; Jarawan, E.; Mathers, C.D. (2004). World report on road traffic injury prevention. World Health Organization.

- Zwi, A.B.; Krug, E.G.; Mercy, J.A.; Dahlberg, L.L. World Report on Violence and Health — exploring Australian responses. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Heal. 2002, 26, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.J.; Anderson, P.A.; Hsu, W.K. Use of computed tomography for assessing bone mineral density. Neurosurg. Focus 2011, 37, E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, F.; Cornelius, C.-P.; Schramm, A. Computer-Assisted Mandibular Reconstruction using a Patient-Specific Reconstruction Plate Fabricated with Computer-Aided Design and Manufacturing Techniques. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2014, 7, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-S.; Kim, S.-G.; Baik, S.-M.; Kim, B.-O.; Kim, H.-K.; Moon, S.-Y.; Lim, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-K.; Yun, P.-Y.; Son, J.-S. Comparative Study Between Resorbable and Nonresorbable Plates in Orthognathic Surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 68, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meara, J.G.; Leather, A.J.M.; Hagander, L.; Alkire, B.C.; Alonso, N.; Ameh, E.A.; Bickler, S.W.; Conteh, L.; Dare, A.J.; Davies, J.; et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015, 386, 569–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, R.A.; Spiegel, D.A.; Coughlin, R.; Zirkle, L.G. Injuries: the neglected burden in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2009, 87, 246–246a. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, S.R.; Ziccardi, V.B. Telemedicine Using Smartphones for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Consultation, Communication, and Treatment Planning. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 2505–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffano, P.; Kommers, S.C.; Karagozoglu, K.H.; Forouzanfar, T. Aetiology of maxillofacial fractures: a review of published studies during the last 30 years. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 52, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrcanovic, B.R. Factors influencing the incidence of maxillofacial fractures. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 16, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassner, R.; Tuli, T.; Hächl, O.; Rudisch, A.; Ulmer, H. Cranio-maxillofacial trauma: a 10 year review of 9543 cases with 21067 injuries. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2003, 31, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, O.; Vesterby, A.; Jensen, J. Pattern of injuries due to interpersonal violence. Injury 1998, 29, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddumba, E.K. A cross sectional retrospective study of boda boda injuries at Mulago Hospital in Kampala, Uganda. East and Central African Journal of Surgery 2004, 9, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bormann, K.-H.; Wild, S.; Gellrich, N.-C.; Kokemüller, H.; Stühmer, C.; Schmelzeisen, R.; Schön, R. Five-Year Retrospective Study of Mandibular Fractures in Freiburg, Germany: Incidence, Etiology, Treatment, and Complications. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, S.; Kogo, M.; Sugiura, T.; Mima, T.; Matsuya, T. Retrospective analysis of 1502 patients with facial fractures. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001, 30, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffano, P.; Roccia, F.; Zavattero, E.; Dediol, E.; Uglešić, V.; Kovačič, Ž.; Vesnaver, A.; Konstantinović, V.S.; Petrović, M.; Stephens, J.; et al. European Maxillofacial Trauma (EURMAT) project: A multicentre and prospective study. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2015, 43, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H. Interpersonal Violence and Facial Fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 1878–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, P.; Kalra, N. A retrospective analysis of maxillofacial injuries in patients reporting to a tertiary care hospital in East Delhi. Int. J. Crit. Illn. Inj. Sci. 2012, 2, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, D.; Follmar, K.E.; DeBruijn, M.; Bruno, A.D.; Jung, S.-H.; Edelman, D.; Mukundan, S.; Marcus, J.R. A Retrospective Analysis of Facial Fracture Etiologies. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2008, 60, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourouzis, C.; Koumoura, F. Sports-related maxillofacial fractures: A retrospective study of 125 patients. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2005, 34, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, R.; Rahman, N.A.; Rahman, R.A.; Hussaini, H.M.; Hamid, A.L.A. A retrospective study of oral and maxillofacial injuries in Seremban Hospital, Malaysia. Dent. Traumatol. 2011, 27, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, J.; Gibbons, A.; Hunt, N.; Monaghan, A.; Gibb, I.; Hepper, A.; Midwinter, M. Mandibular fractures in British military personnel secondary to blast trauma sustained in Iraq and Afghanistan. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 49, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzano, G.; Dell'Aversana Orabona, G.; Audino, G.; Vaira, L.A.; Trevisiol, L.; D'Agostino, A. ; .. Nocini, P.F. Have there been any changes in the epidemiology and etiology of maxillofacial trauma during the Italian lockdown for the COVID-19 epidemic? An analysis of 712 injuries received during the pandemic. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 2021, 49, 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Boffano, P.; Kommers, S.C.; Karagozoglu, K.H.; Forouzanfar, T. Aetiology of maxillofacial fractures: a review of published studies during the last 30 years. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 52, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singaram, M.; G, S.V.; Udhayakumar, R.K. Prevalence, pattern, etiology, and management of maxillofacial trauma in a developing country: a retrospective study. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 42, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Global trends in maxillofacial fractures. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 2012, 5, 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.Y.-H.; Choi, A.W.-M.; Fong, D.Y.-T.; Wong, J.K.-S.; Lau, C.-L.; Kam, C.-W. Patterns, aetiology and risk factors of intimate partner violence-related injuries to head, neck and face in Chinese women. BMC Women's Heal. 2014, 14, 6–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, K.; Kuraki, M.; Kurihara, M.; Matsusue, Y.; Murakami, K.; Horita, S.; Sugiura, T.; Kirita, T. Maxillofacial Fractures Resulting From Falls. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 1602–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassner, R.; Tuli, T.; Hächl, O.; Moreira, R.; Ulmer, H. Craniomaxillofacial trauma in children: a review of 3,385 cases with 6,060 injuries in 10 years. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 62, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, R.D.C.A.; de Melo, G.P.; Antunes, A.A.; Dourado, E.; de Barros Silva, P.G. The influence of extreme sports in the prevalence of maxillofacial fractures: a retrospective study of 72 cases. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2014, 18, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Roccia, F.; Bianchi, F.; Zavattero, E.; Tanteri, G.; Ramieri, G. Characteristics of maxillofacial trauma in females: A retrospective analysis of 367 patients. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2010, 38, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, J.; Gibbons, A.J.; Shieff, C.; Banfield, G.; Bryant, D.G.; Midwinter, M.J. Combat-Related Craniofacial and Cervical Injuries: A 5-Year Review From the British Military. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2011, 71, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugboko, V.I.; Olasoji, H.O.; Ajike, S.O.; Amole, A.O.D.; Ogundipe, O.T. Facial injuries caused by animals in northern Nigeria. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2002, 40, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’meara, C.; Witherspoon, R.; Hapangama, N.; Hyam, D.M. Alcohol and interpersonal violence may increase the severity of facial fracture. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 50, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namiri, N.K.; Lui, H.; Tangney, T.; Allen, I.E.; Cohen, A.J.; Breyer, B.N. Electric Scooter Injuries and Hospital Admissions in the United States, 2014-2018. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassner, R.; Tuli, T.; Hächl, O.; Rudisch, A.; Ulmer, H. Cranio-maxillofacial trauma: a 10 year review of 9543 cases with 21067 injuries. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2003, 31, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.; Holmes, S. (2014). Atlas of operative maxillofacial trauma surgery: primary repair of facial injuries. Springer.

- Hollier, L.H.; Sharabi, S.E.; Koshy, J.C.; Stal, S. Facial trauma: general principles of management. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2010, 21, 1051–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, A.; Doherty, T.; Lewen, G. Facial Fractures and Concomitant Injuries in Trauma Patients. Laryngoscope 2003, 113, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariades, N.; Mezitis, M.; Mourouzis, C.; Papadakis, D.; Spanou, A. Fractures of the mandibular condyle: A review of 466 cases. Literature review, reflections on treatment and proposals. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2006, 34, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manson, P.N.; Clark, N.; Robertson, B.; Slezak, S.; Wheatly, M.; Kolk, C.V.; Iliff, N. Subunit Principles in Midface Fractures: The Importance of Sagittal Buttresses, Soft-Tissue Reductions, and Sequencing Treatment of Segmental Fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999, 103, 1287–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; You, S.H.; Kim, S.G.; Lee, S.I. Analysis of Nasal Bone Fractures; A Six-year Study of 503 Patients. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2007, 19, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Metzinger, S.; Guerra, A.B.; Garcia, R.E. Frontal Sinus Fractures: Management Guidelines. Facial Plast. Surg. 2005, 21, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreasen, J.O.; Andreasen, F.M.; Andersson, L. Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth. Stomatol. EDU J. 2018, 6, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Andreasen, J.O.; Day, P.; Heithersay, G.; Trope, M.; DiAngelis, A.J.; Kenny, D.J.; Sigurdsson, A.; Bourguignon, C.; Flores, M.T.; et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent. Traumatol. 2012, 28, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajandram, R.K.; Omar, S.N.S.; Rashdi, M.F.N.; Jabar, M.N.A. Maxillofacial injuries and traumatic brain injury – a pilot study. Dent. Traumatol. 2014, 30, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, R.P.; Friedman, J.A.; Mahabir, R.C. A Nationwide Review of the Associations Among Cervical Spine Injuries, Head Injuries, and Facial Fractures. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2010, 68, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai-Ourainy, I.; Dutton, G.; Stassen, L.; Moos, K.; Ei-Attar, A. The characteristics of midfacial fractures and the association with ocular injury: a prospective study. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1991, 29, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.; Morris, C. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) and facial trauma: can one size fit all? Part 2: ATLS, maxillofacial injuries and airway management dilemmas. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2008, 37, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allareddy, V.; Allareddy, V.; Nalliah, R.P. Epidemiology of facial fracture injuries. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2011, 69, 2613–2618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmutz, B.; Rahmel, B.; McNamara, Z.; Coulthard, A.; Schuetz, M.; Lynham, A. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: An Accurate, Radiation-Free, Alternative to Computed Tomography for the Primary Imaging and Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of the Bony Orbit. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 72, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, K.F.; Tahim, A.; Mc Goodson, A.; Delaney, M.; Fan, K. A Review Of Current Clinical Photography Guidelines In Relation To Smartphone Publishing Of Medical Images. J. Vis. Commun. Med. 2013, 35, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, E.G.; Sharma, G.K.; Lozano, R. The global burden of injuries. American Journal of Public Health 2000, 90, 523–526. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, S.M.; Shetty, V.; Elliot-Brown, K.; Leathers, R.; Belin, T.R.; Wang, J. Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Facial Injury: A 1-year Prospective Cohort Study. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2007, 62, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotto, J.A.; MacKenzie, E.; Fowler, C.; Redett, R.; Robertson, B.; Manson, P.N. Long-Term Physical Impairment and Functional Outcomes after Complex Facial Fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001, 108, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, J.K.; Asteriadis, S.; Likavec, M.J. Middle and upper facial fractures: a retrospective review of 234 patients. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2005, 63, 790–794. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, E.; Degutis, L.; Pruzinsky, T.; Shin, J.; Persing, J.A. Quality of life and facial trauma: psychological and body image effects. Annals of Plastic Surgery 2005, 54, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, R.J.; Walker, R.V.; Betts, N.J.; Barber, H.D.; Powers, M.P. (2013). Oral and maxillofacial trauma. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Scherer, M.; Sullivan, W.G.; Smith, D.J.; Phillips, L.G.; Robson, M.C. An Analysis of 1,423 Facial Fractures in 788 Patients at an Urban Trauma Center. 1989, 29, 388–390. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Ahmed, M.; Walton, G.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Hoffman, G.R. The association between depression and anxiety disorders following facial trauma—A comparative study. Injury 2010, 41, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, P.A.; Schliephake, H.; Ghali, G.E.; Cascarini, L. (2017). Maxillofacial Surgery. Churchill Livingstone.

- Peled, M.; Leiser, Y.; Emodi, O.; Krausz, A. Treatment Protocol for High Velocity/High Energy Gunshot Injuries to the Face. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2012, 5, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, P.; Rivara, F.P. Car occupant death according to the restraint use of other occupants: a matched cohort study. JAMA 2004, 291, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, M.; Qin, H.; Luan, J. Factors associated with higher levels of injury severity in occupants of motor vehicles that were severely damaged in traffic crashes in Kentucky, 2000-2001. Traffic Injury Prevention 2004, 5, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.C.; Ivers, R.; Norton, R.; Boufous, S.; Blows, S.; Lo, S.K. Helmets for preventing injury in motorcycle riders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, CD004333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retting, R.A.; Ferguson, S.A.; McCartt, A.T. A Review of Evidence-Based Traffic Engineering Measures Designed to Reduce Pedestrian–Motor Vehicle Crashes. Am. J. Public Heal. 2003, 93, 1456–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florence, C.; Shepherd, J.; Brennan, I.; Simon, T. Effectiveness of anonymised information sharing and use in health service, police, and local government partnership for preventing violence related injury: experimental study and time series analysis. BMJ 2011, 342, d3313–d3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, E.G.; A Mercy, J.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Zwi, A.B. The world report on violence and health. Lancet 2002, 360, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.C. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 2002, 359, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipscomb, H.J. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent work-related eye injuries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000, 18, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, D.A.; Verma, S.K.; Brennan, M.J.; Perry, M.J. Factors influencing worker use of personal protective eyewear. 2009, 41, 755–762. [CrossRef]

- Newsome, P.R.H.; Tran, D.C.; Cooke, M.S. The role of the mouthguard in the prevention of sports-related dental injuries: a review. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2001, 11, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.A.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, C.F.; Donaldson, A. A sports setting matrix for understanding the implementation context for community sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 44, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, L.; Andreasen, J.O.; Day, P.; Heithersay, G.; Trope, M.; DiAngelis, A.J.; Kenny, D.J.; Sigurdsson, A.; Bourguignon, C.; Flores, M.T.; et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent. Traumatol. 2012, 28, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, D.R.; Chen, I.; Smith, R.; Elliott, M.R.; Winston, F.K. Effects of Seating Position and Appropriate Restraint Use on the Risk of Injury to Children in Motor Vehicle Crashes. Pediatrics 2005, 115, e305–e309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, E. Timing of definitive management of facial fractures. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2019, 77, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann, D.; Follmar, K.E.; DeBruijn, M.; Bruno, A.D.; Jung, S.-H.; Edelman, D.; Mukundan, S.; Marcus, J.R. A Retrospective Analysis of Facial Fracture Etiologies. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2008, 60, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manson, P.N.; Clark, N.; Robertson, B.; Slezak, S.; Wheatly, M.; Kolk, C.V.; Iliff, N. Subunit Principles in Midface Fractures: The Importance of Sagittal Buttresses, Soft-Tissue Reductions, and Sequencing Treatment of Segmental Fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999, 103, 1287–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrcanovic, B.R. Open versus closed reduction: comminuted mandibular fractures. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 17, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariades, N.; Mezitis, M.; Mourouzis, C.; Papadakis, D.; Spanou, A. Fractures of the mandibular condyle: A review of 466 cases. Literature review, reflections on treatment and proposals. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2006, 34, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, R.; Gutwald, R.; Schramm, A.; Gellrich, N.-C.; Schmelzeisen, R. Endoscopy-assisted open treatment of condylar fractures of the mandible: extraoral vs intraoral approach. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2002, 31, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgarelli, A.C.; Bellini, P.; Landini, B.; Multinu, A.; Consolo, U. A comparative study of different approaches in the treatment of orbital trauma: an experience based on 274 cases. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 14, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, B.; Seligson, D. Removal of asymptomatic bone plates used for orthognathic surgery and facial fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1996, 54, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, T.; Essig, H.; Metzler, P.; Lindhorst, D.; Dubois, L.; Rücker, M.; Schumann, P. Patient specific implants (PSI) in reconstruction of orbital floor and wall fractures. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2015, 43, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodby, K.A.; Turin, S.; Jacobs, R.J.; Cruz, J.F.; Hassid, V.J.; Kolokythas, A.; Antony, A.K. Advances in oncologic head and neck reconstruction: Systematic review and future considerations of virtual surgical planning and computer aided design/computer aided modeling. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2014, 67, 1171–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menick, F.J. (2007). Nasal reconstruction: art and practice. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Coleman, S.R. Structural Fat Grafting: More Than a Permanent Filler. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 118, 108S–120S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, B.L.; Manson, P.N. Panfacial fractures: organization of treatment. . 1989, 16, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Shen, S.G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S. The indication and application of computer-assisted navigation in oral and maxillofacial surgery—Shanghai's experience based on 104 cases. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2013, 41, 770–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomahac, B.; Pribaz, J.; Eriksson, E.; Bueno, E.M.; Diaz-Siso, J.R.; Rybicki, F.J.; Annino, D.J.; Orgill, D.; Caterson, E.J.; Caterson, S.A.; et al. Three Patients with Full Facial Transplantation. New Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, A.; Rehab, M.; O’neil, M.; Khambay, B.; Ju, X.; Barbenel, J.; Naudi, K. A novel approach for planning orthognathic surgery: The integration of dental casts into three-dimensional printed mandibular models. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaigler, D.; Avila, G.; Wisner-Lynch, L.; Nevins, M.L.; Nevins, M.; Rasperini, G.; E Lynch, S.; Giannobile, W.V. Platelet-derived growth factor applications in periodontal and peri-implant bone regeneration. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2011, 11, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, J.O.; Jensen, S.S.; Schwartz, O.; Hillerup, Y. A Systematic Review of Prophylactic Antibiotics in the Surgical Treatment of Maxillofacial Fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 64, 1664–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogbill, T.H.; Cothren, C.C.; Ahearn, M.K.; Cullinane, D.C.; Kaups, K.L.; Scalea, T.M.; Maggio, L.; Brasel, K.J.; Harrison, P.B.; Patel, N.Y.; et al. Management of Maxillofacial Injuries With Severe Oronasal Hemorrhage: A Multicenter Perspective. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2008, 65, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouloux, G.F.; Perciaccante, V.J. Massive hemorrhage during oral and maxillofacial surgery: ligation of the external carotid artery or embolization? Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2004, 62, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Ulug, T.; Ulubil, S.A. Management of facial paralysis in temporal bone fractures: a prospective study analyzing 11 operated fractures. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2005, 26, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.B.; Sawatari, Y.D.; Peleg, M.D. High-Energy Traumatic Maxillofacial Injury. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2015, 26, 1487–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.L.; Laskin, D.M.; Best, A.M. Closed Versus Open Reduction of Mandibular Condylar Fractures in Adults: A Meta-Analysis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, C.; Sigron, G.R.; Jaquiéry, C. Functional outcome after non-surgical management of orbital fractures—the bias of decision-making according to size of defect: critical review of 48 patients. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 51, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondin, V.; Rinaldo, A.; Ferlito, A. Management of nasal bone fractures. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2005, 26, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, S.M.; Shetty, V.; Elliot-Brown, K.; Leathers, R.; Belin, T.R.; Wang, J. Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Facial Injury: A 1-year Prospective Cohort Study. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2007, 62, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Ahmed, M.; Walton, G.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Hoffman, G.R. The association between depression and anxiety disorders following facial trauma—A comparative study. Injury 2010, 41, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, E.; Degutis, L.; Pruzinsky, T.; Shin, J.; Persing, J.A. Quality of life and facial trauma: psychological and body image effects. Annals of Plastic Surgery 2005, 54, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Bisson, J.I.; Psychotherapy; Shepherd, J. P.; Dhutia, M. Psychological Sequelae of Facial Trauma. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 1997, 43, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, A. Psychological issues in acquired facial trauma. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery 2008, 41, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, E.; Degutis, L.; Pruzinsky, T.; Shin, J.; Persing, J.A. Quality of life and facial trauma: psychological and body image effects. Annals of Plastic Surgery 2005, 54, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allareddy, V.; Allareddy, V.; Nalliah, R.P. Epidemiology of facial fracture injuries. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2011, 69, 2613–2618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bin Sulong, S.; Ramli, R.; Ahmed, Z.; Nur, A.M.; Ibrahim, M.I.; Rashdi, M.F.; Nordin, R.; Rahman, N.A.; Yusoff, A.; Jabar, M.A.; et al. Cost analysis of facial injury treatment in two university hospitals in Malaysia: a prospective study. Clin. Outcomes Res. 2017, 9, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.Y.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chen, Y.R.; Yang, J.Y. Long-term outcomes and costs of complex facial reconstructions. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2019, 143, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, J.; Hauser, W.A.; Manson, P.N. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kellman, R.M.; Rosenberg, M. (2007). Facial trauma: immediate and long-term sequelae. In Flint, P.W., Haughey, B.H., Lund, V.J., Niparko, J.K., Richardson, M.A., Robbins, K.T., Thomas, J.R., Eds.; Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery (5th ed., pp. 1543–1561). Mosby Elsevier.

- Glynn, S.M.; Shetty, V.; Elliot-Brown, K.; Leathers, R.; Belin, T.R.; Wang, J. Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Facial Injury: A 1-year Prospective Cohort Study. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2007, 62, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R.; Deleyiannis, F.W.; Zimbler, M.S. The financial impact of facial trauma: a survey of patients. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2017, 75, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Girotto, J.A.; MacKenzie, E.; Fowler, C.; Redett, R.; Robertson, B.; Manson, P.N. Long-Term Physical Impairment and Functional Outcomes after Complex Facial Fractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001, 108, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allareddy, V.; Rampa, S.; Lee, M.K.; Allareddy, V.; Nalliah, R.P. Hospital-based emergency department visits involving dental conditions: profile and predictors of poor outcomes and resource utilization. The Journal of the American Dental Association 2014, 145, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Snape, L.; Steenberg, L.J.; Worthington, J. Comparison between interpersonal violence and motor vehicle accidents in the aetiology of maxillofacial fractures. ANZ J. Surg. 2007, 77, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]