Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

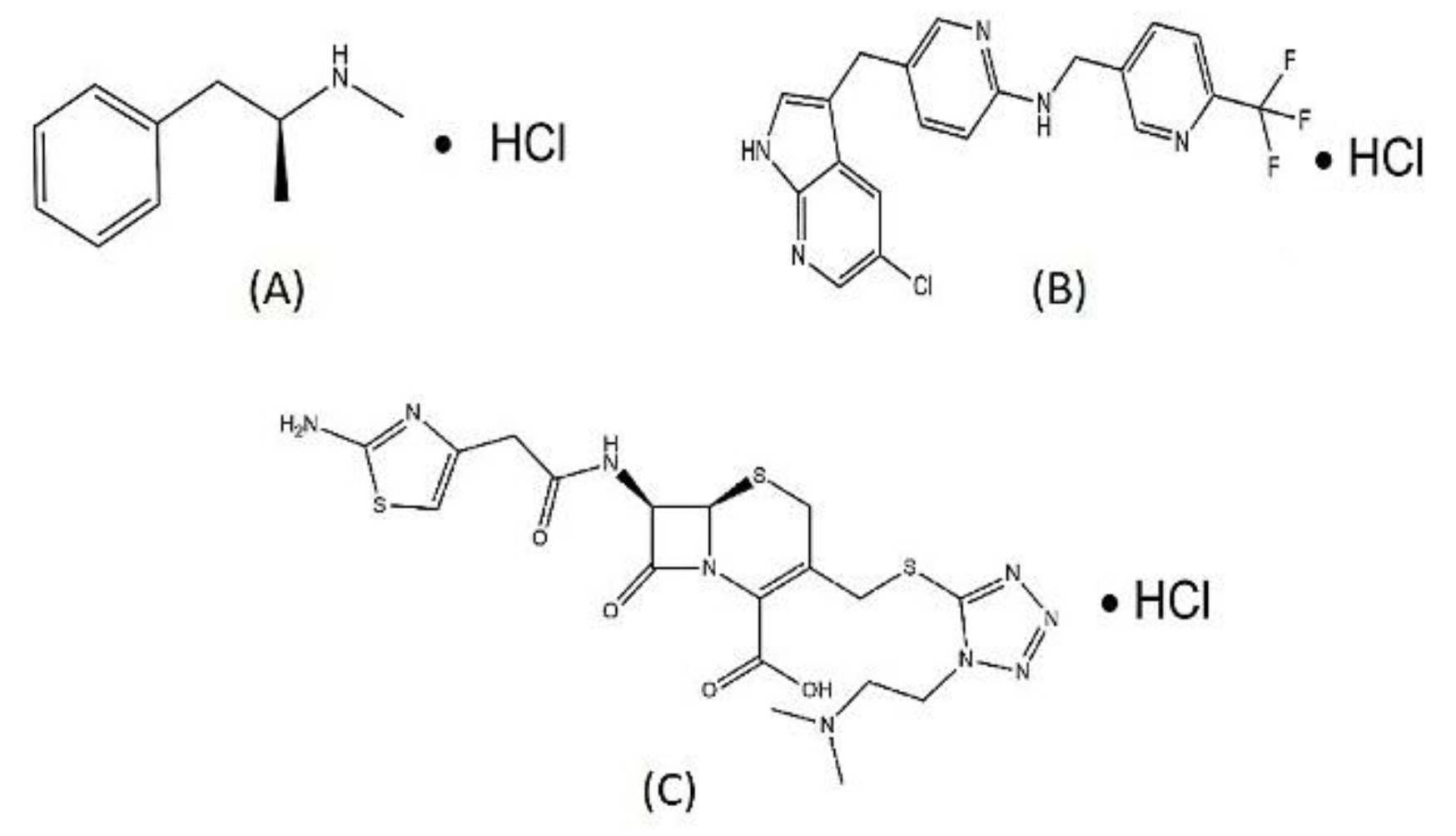

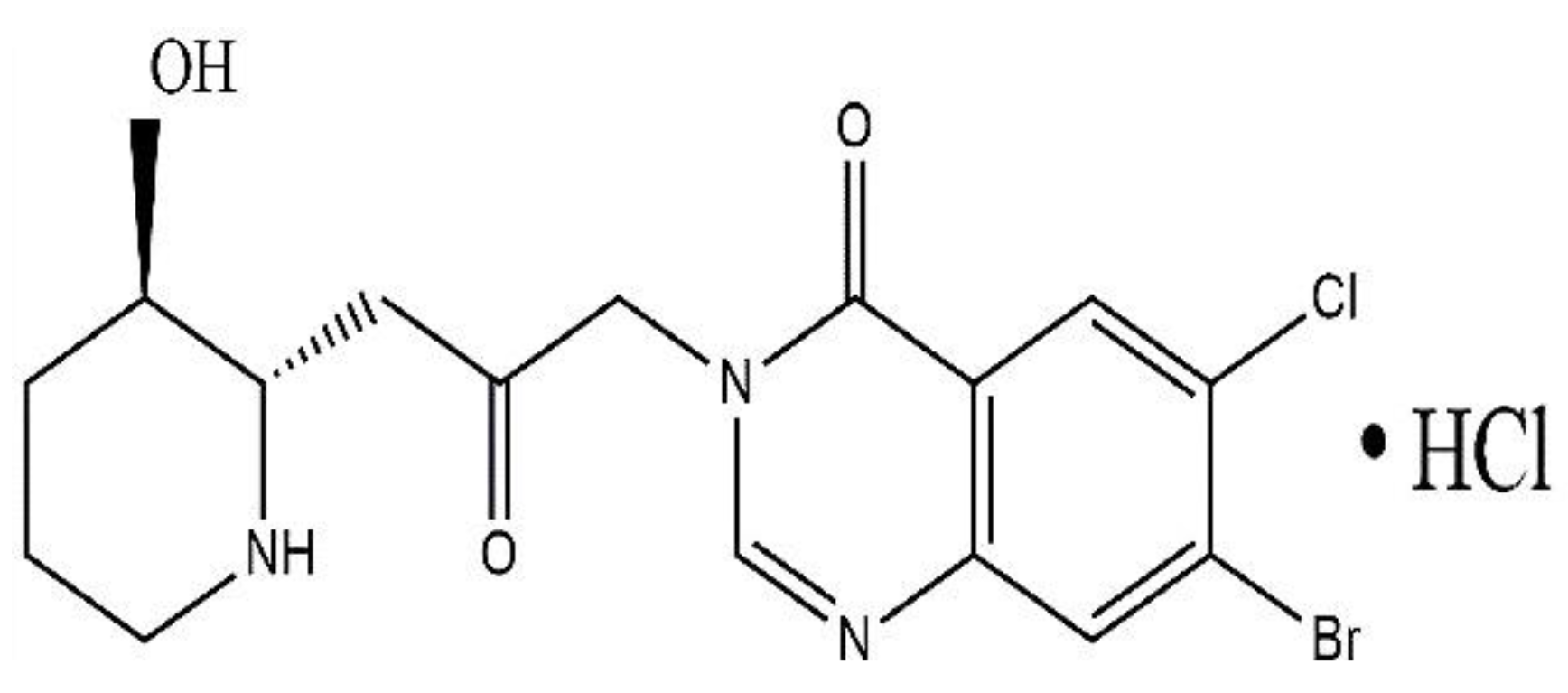

2.1. Biochemistry and Structural Analogues of Halofuginone:

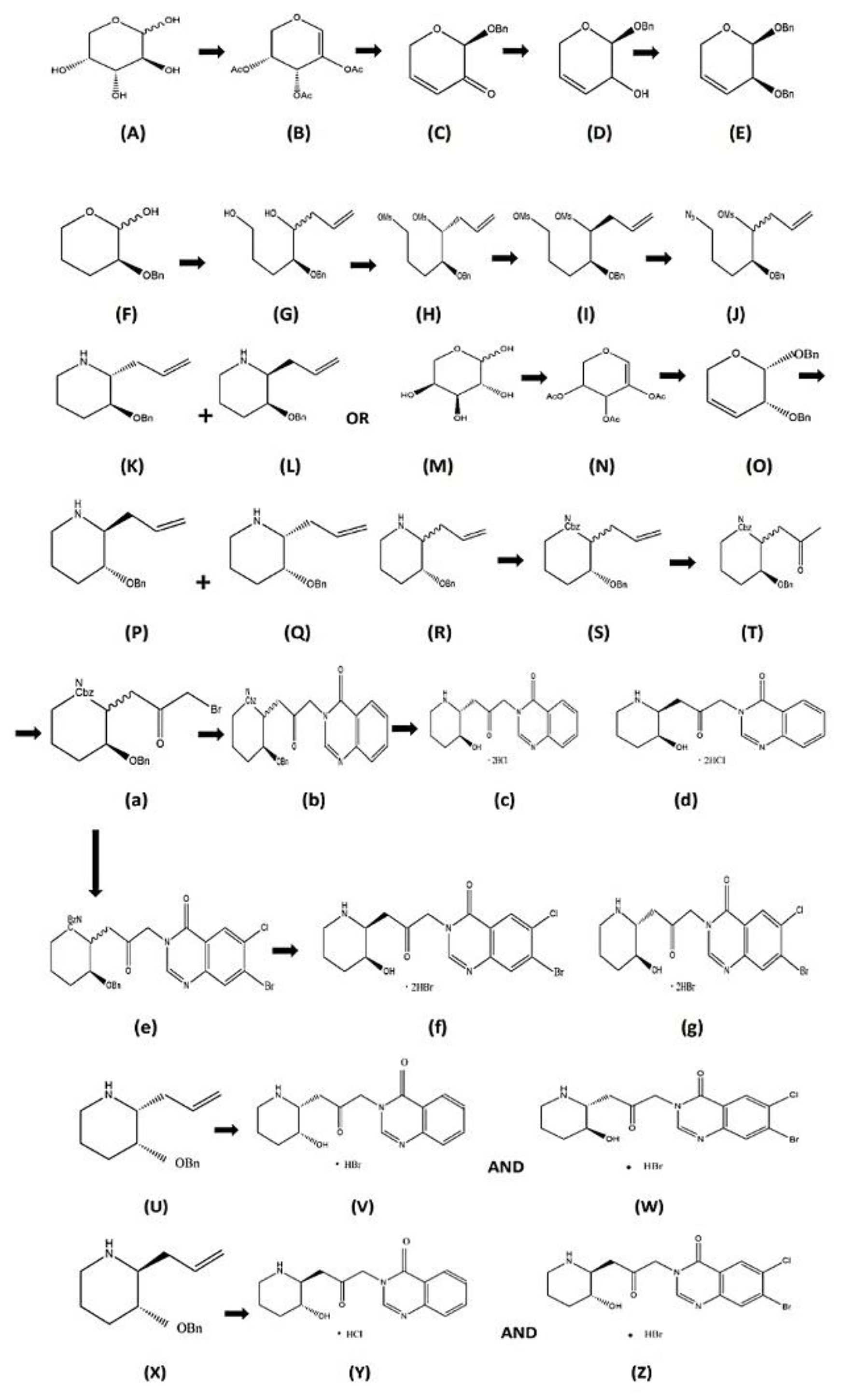

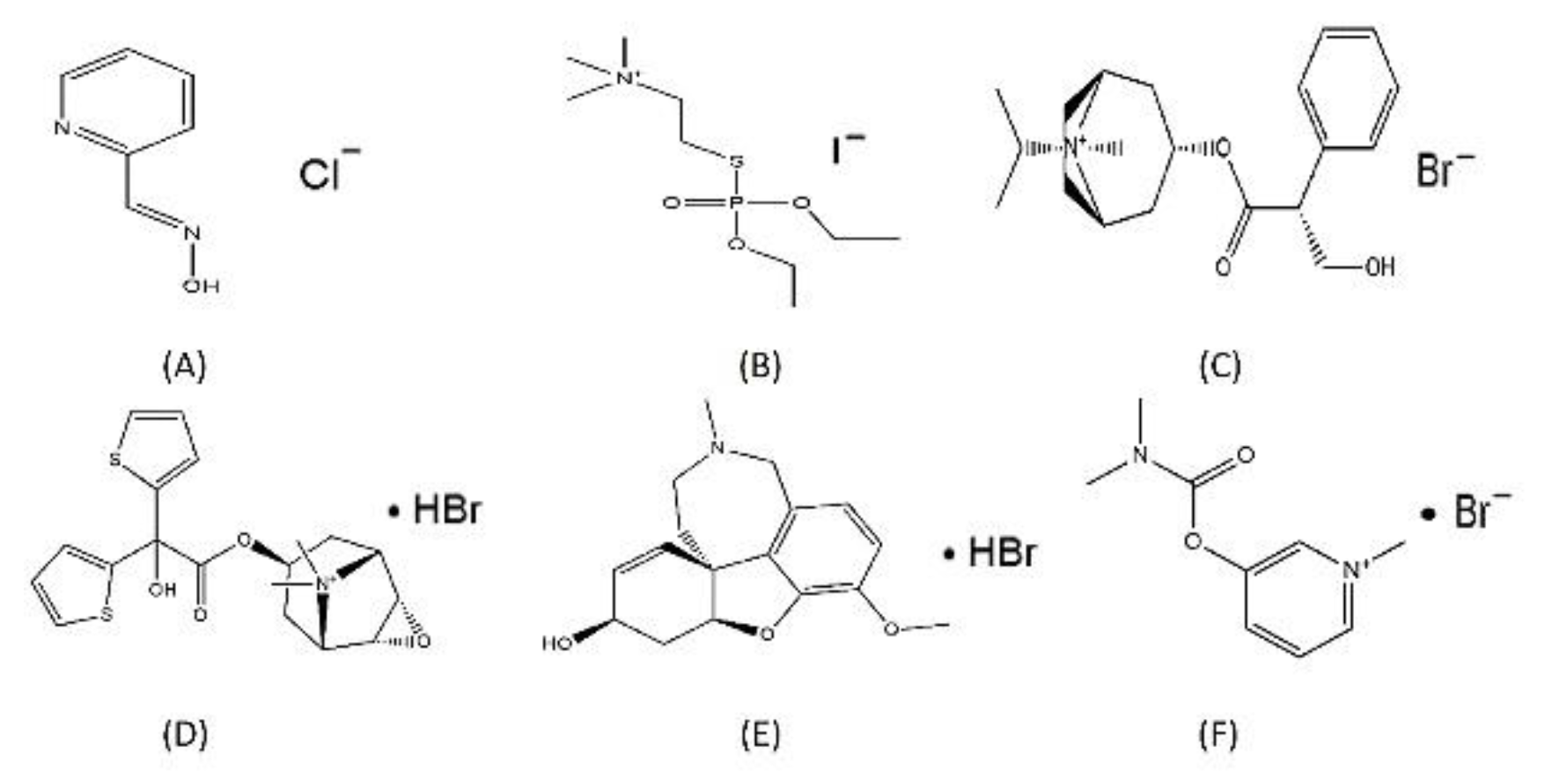

2.2. Stereoisomeric Synthesis of Halofuginone HBr Salt:

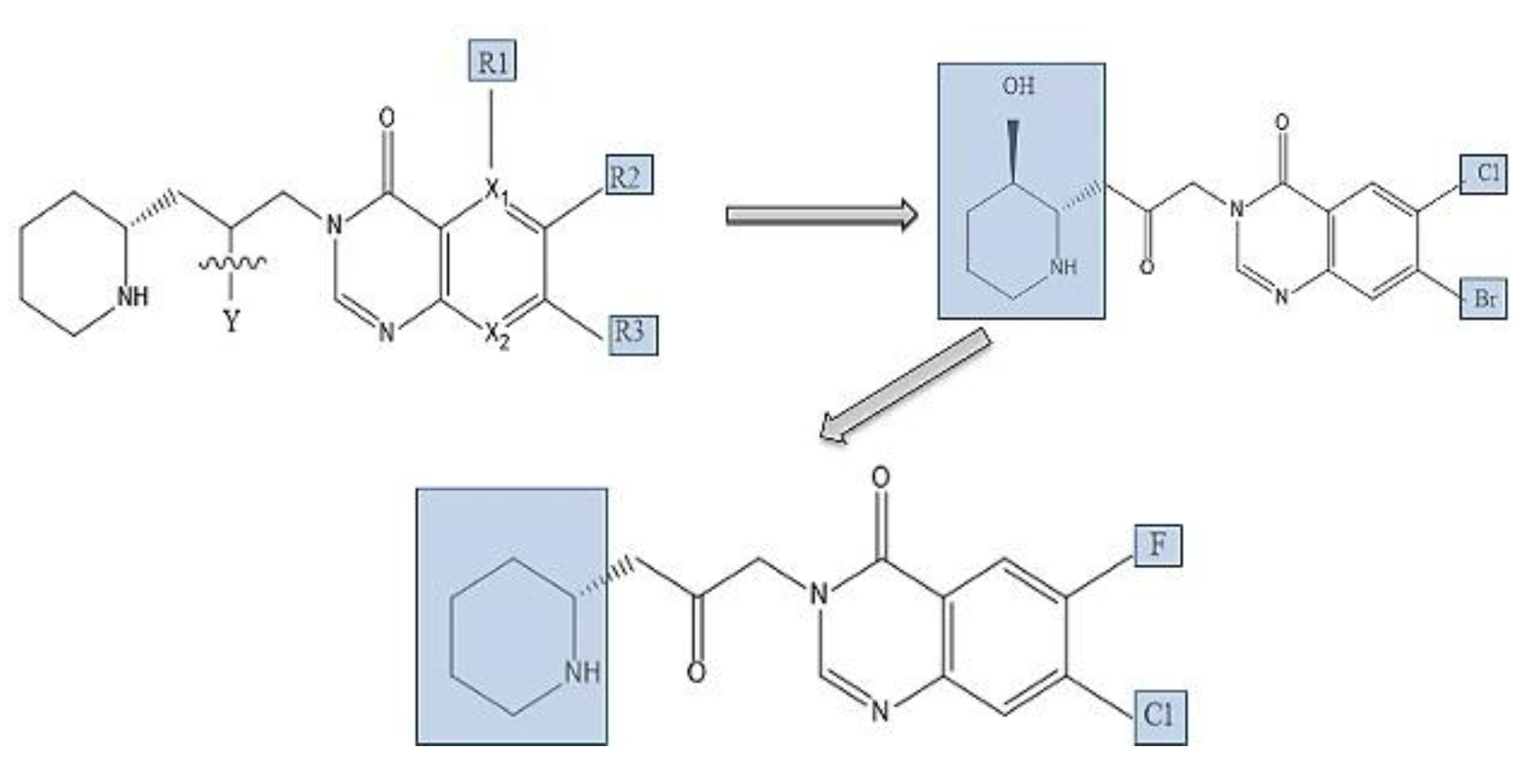

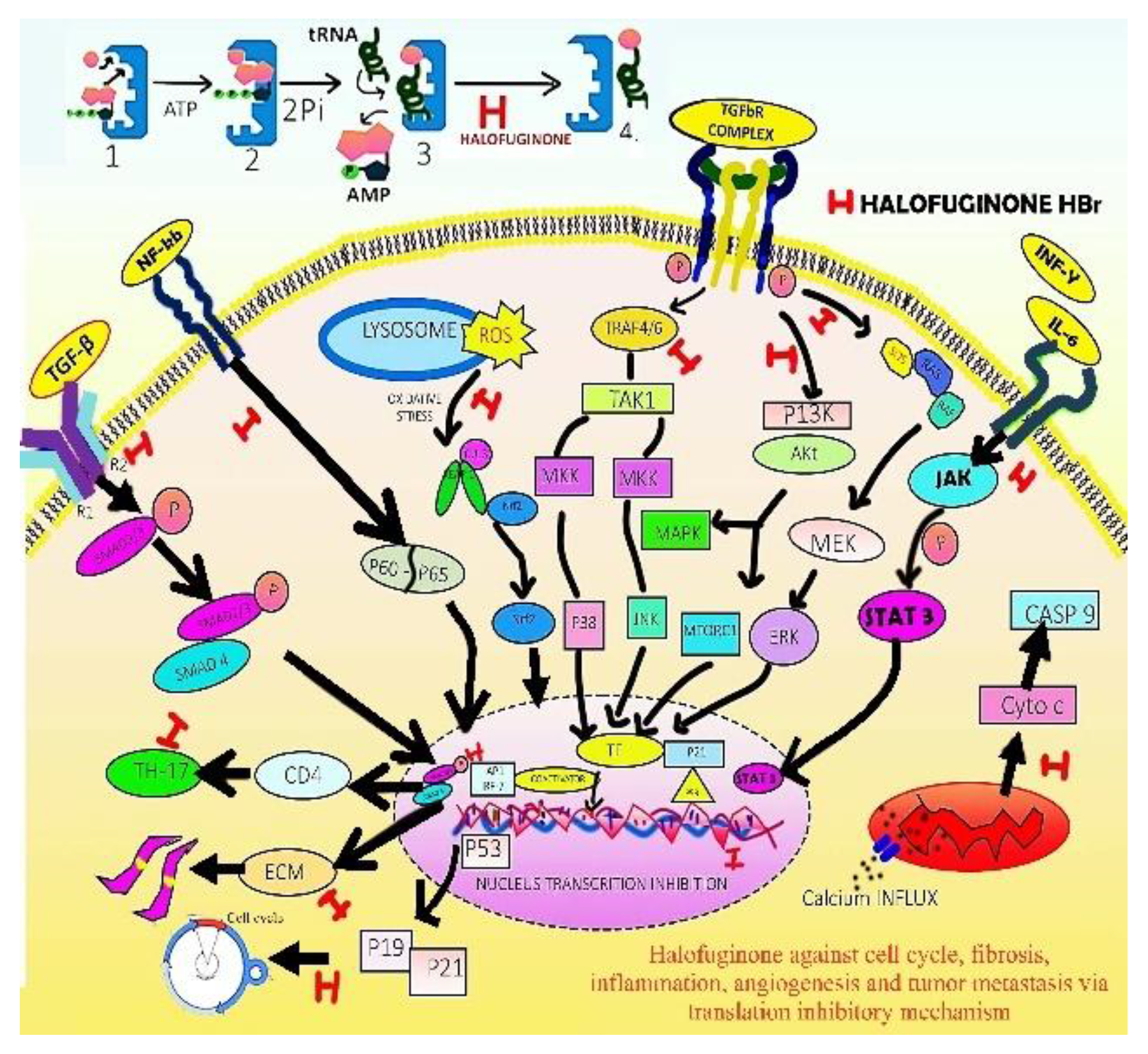

2.3. Clinical Significance of Halofuginone- Novel tRNA Synthesis Inhibitor:

2.3.1. Antimalarial Therapy:

2.3.2. Antiprotozoal:

2.3.3. Antifibrotic Agent:

2.3.4. Halofuginone Targeting metabolic Disorders:

2.3.5. Antiinflammation and Immunomodulation:

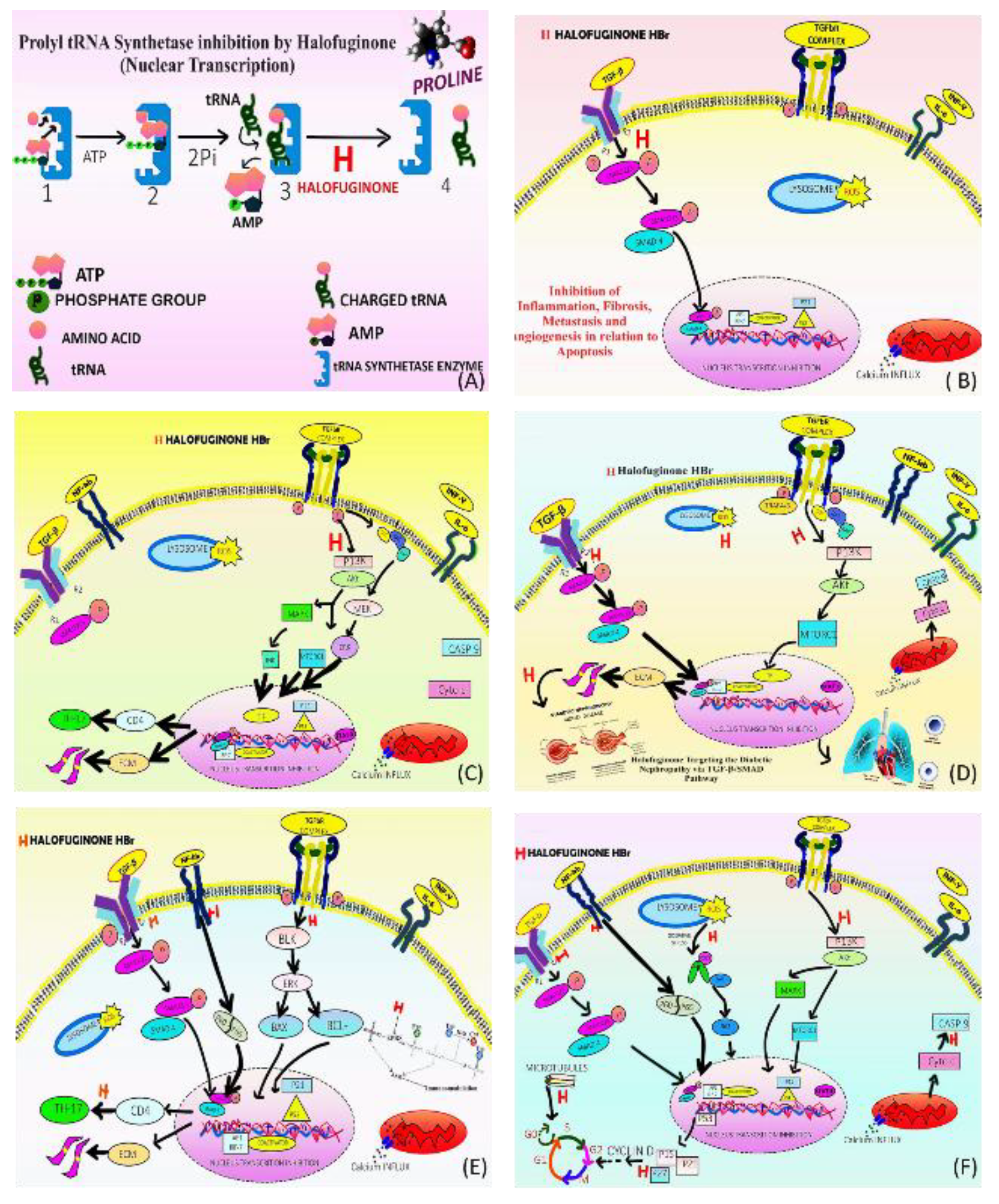

2.4. Halofuginone Targeting Various Cancer Subtypes:

2.4.1. Gastric Cancer and Colorectal Cancer:

2.4.2. Breast Cancer:

2.4.3. Lung Cancer:

2.4.4. Hepatocarcinoma:

2.5. Therapeutic and Clinical Potential of Halofuginone:

| Disease | Clinical trials | Active ingredient | Route | Dose | Dlt | Reference |

| Kaposi sarcoma, renal cancer. Rectum cancer, melanomas and Non-small-cell lung-cancer | Phase II and PK | Halofuginone |

Topical | 0.01% w/w ointment, twice daily | No side effect | [232] |

|

Advanced solid tumours |

Phase I and PK Studies | Halofuginone |

Oral | 0.5-3.5 mg/D | Nausea, vomiting, fatigue | [235] |

|

Chronic graft vs host disease Scleroderma |

Phase I and PKStudies | Halofuginone |

Topical cream | 0.1% | No side effect | [236] |

| Covid-19 | Phase II | Halofuginone | Oral | 0.5mg, 1 mg and placebo OD for 10 days | Well tolerated | [237] |

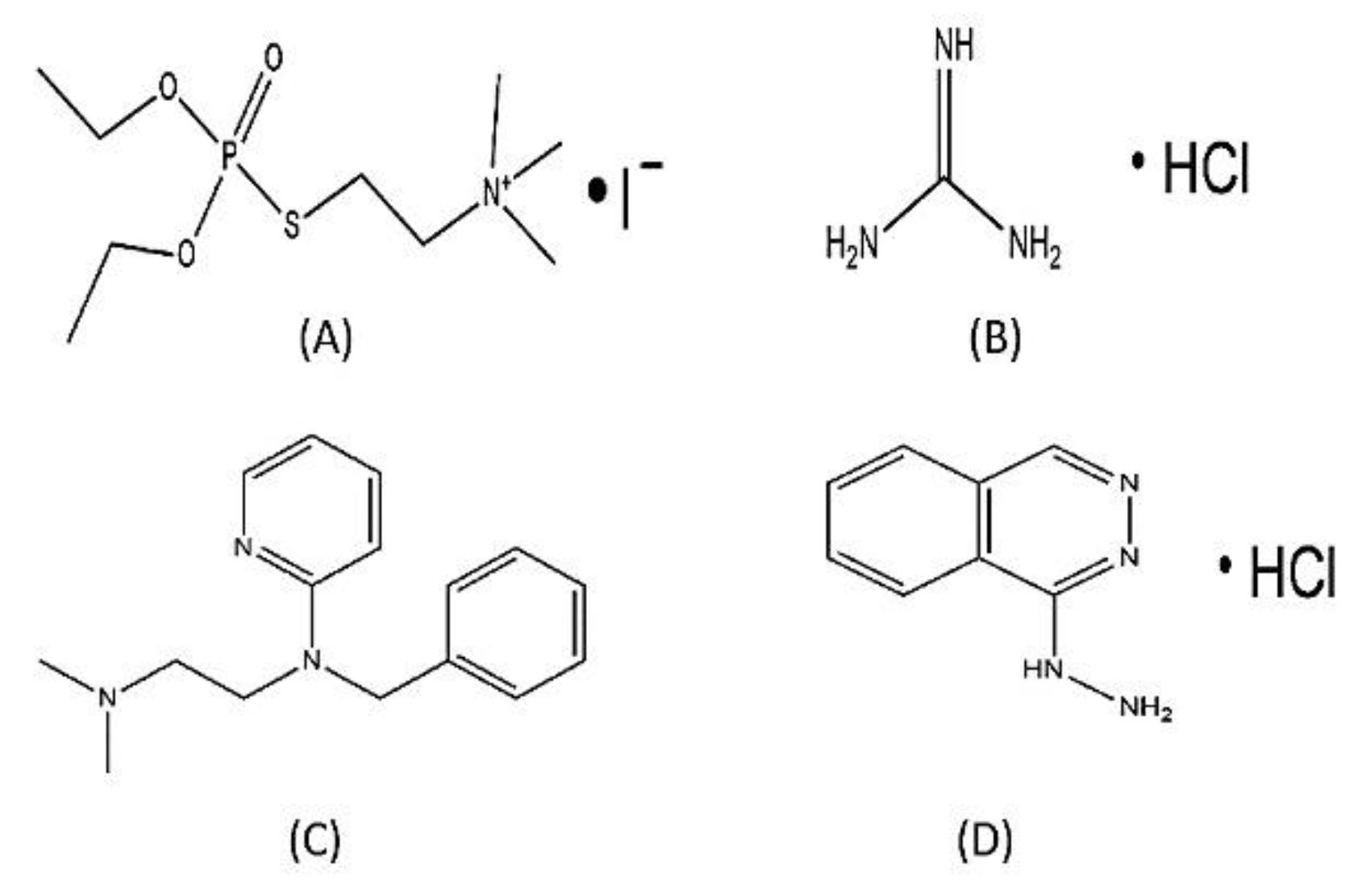

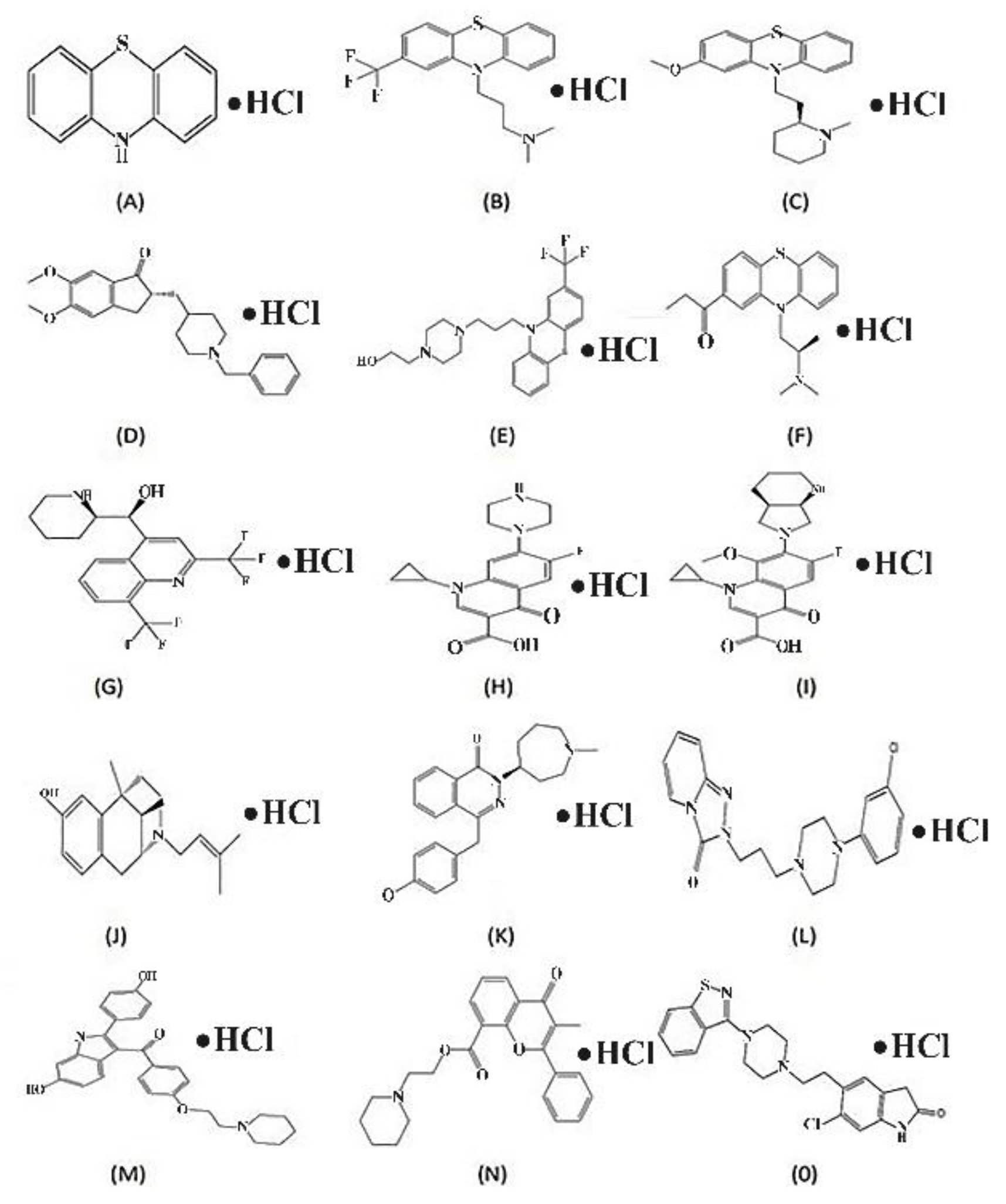

2.6. Effect of Halide Salt Formulations on Safety and Efficacy of Halofuginone:

2.7. HCl Conjugate Formation of Halofuginone:

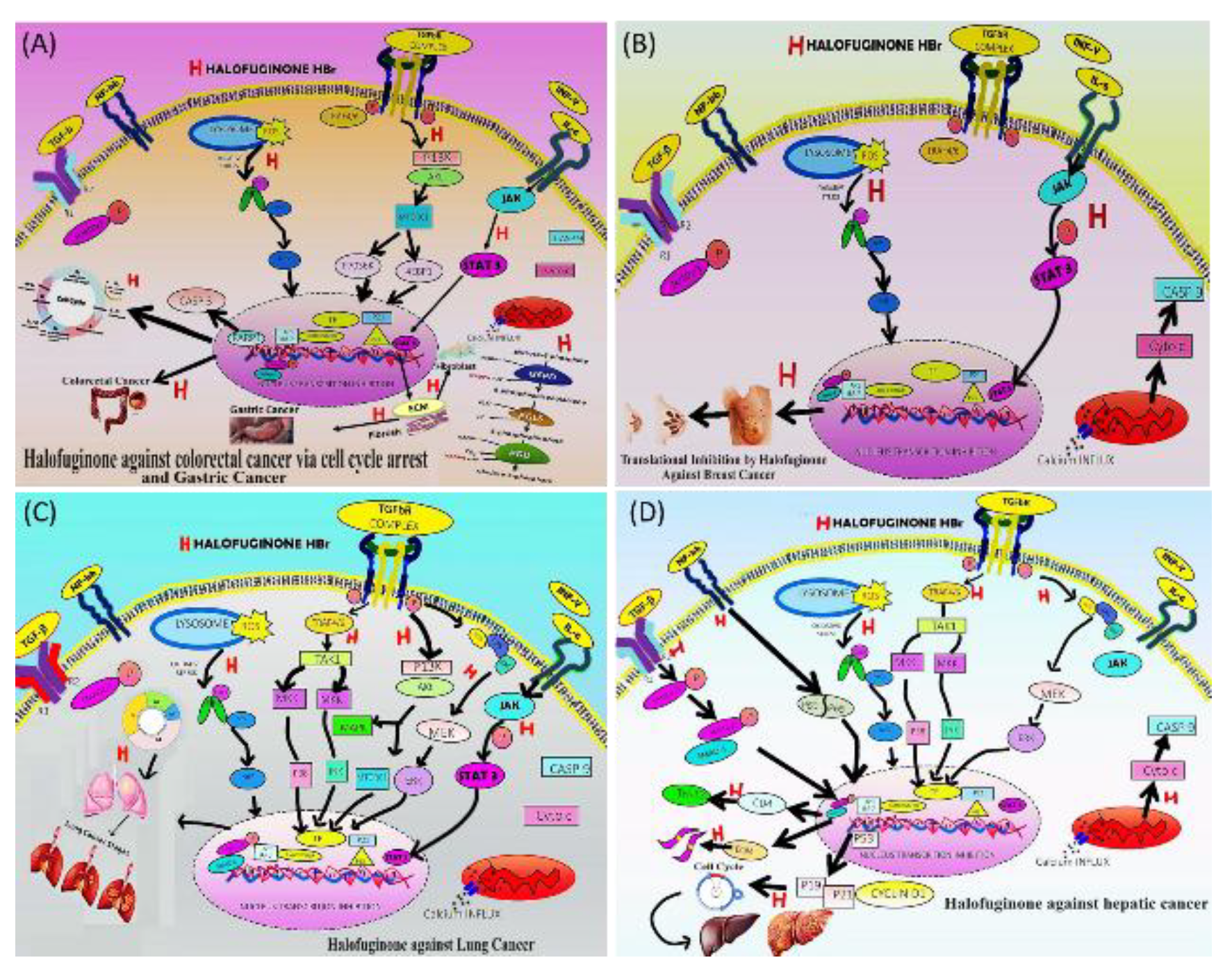

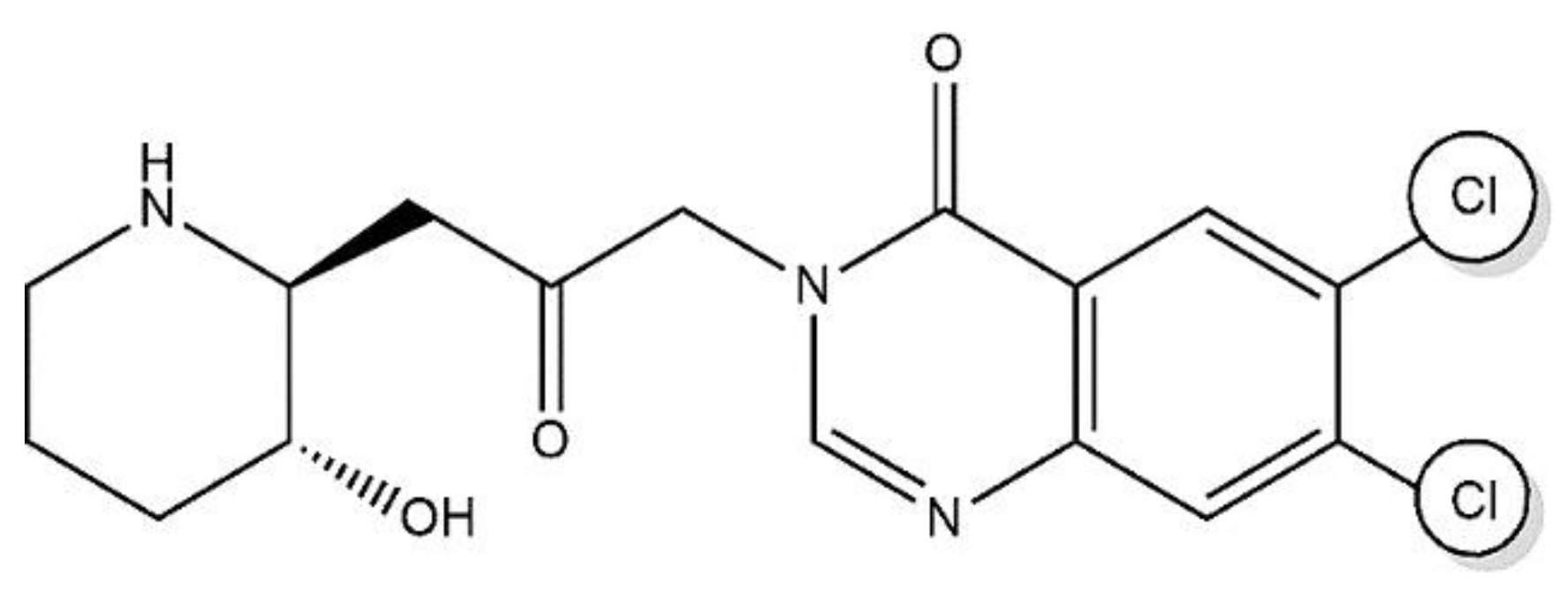

2.8. Stereoisomeric Synthesis of Halofuginone HCl Salt and Its Projected Properties:

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2022; 72. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; et al. Fisetin micelles precisely exhibit a radiosensitization effect by inhibiting PDGFRβ/STAT1/STAT3/Bcl-2 signaling pathway in tumor. Chinese Chemical Letters 2024, 109734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; et al. Recent advances in enhancing reactive oxygen species based chemodynamic therapy. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.J.; et al. Effects of Curcuma longa L. and Piper nigrum L. Against Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Infectious Angiogenesis. J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2024, 18, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-L.; et al. Traditional Chinese medicine in cancer care: an overview of 5834 randomized controlled trials published in Chinese. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 15347354211031650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; et al. Cancer statistics for the US Hispanic/Latino population, 2021. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; et al. The burden of cancer, government strategic policies, and challenges in Pakistan: A comprehensive review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 940514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in Asian countries: A trend analysis. Cancer Control 2022, 29, 10732748221095955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curado, M.-P.; et al. Cancer incidence in five continents, Volume IX. 2007: IARC Press, International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- Ferlay, J.; et al. QOL comparison of PG and TG 415. Int J Cancer 2010, 127, 2893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, S.; Sharpless, N.E. Cancer as a global health priority. Jama 2021, 326, 809–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, R.; et al. A scoping review on the Status of female breast Cancer in Asia with a special focus on Nepal. Breast Cancer: Targets Ther. 2022, 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, M.L.; et al. Differences in breast cancer incidence among young women aged 20–49 years by stage and tumor characteristics, age, race, and ethnicity, 2004–2013. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 169, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.W. The changing trends in live birth statistics in Korea, 1970 to 2010. Korean J. Pediatr. 2011, 54, 429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, C.Y.; Lim, J.-Y.; Park, H.-Y. Age at natural menopause in Koreans: secular trends and influences thereon. Menopause 2018, 25, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.C.; et al. A study on the menstruation of Korean adolescent girls in Seoul. Korean J. Pediatr. 2011, 54, 201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Maso, L.D.; Vaccarella, S. Global trends in thyroid cancer incidence and the impact of overdiagnosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.E. Cigarette smoking among successive birth cohorts of men and women in the United States during 1900–1980. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1983, 71, 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Rakshit, B. Global burden of cancers attributable to tobacco smoking, 1990–2019: an ecological study. EPMA J. 2023, 14, 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, B.; et al. Physical activity behaviour change in black prostate cancer survivors: a qualitative study using the Behaviour Change Wheel. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 154. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2017. Cancer Res. Treat. : Off. J. Korean Cancer Assoc. 2020, 52, 335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Katanoda, K.; et al. An updated report on the trends in cancer incidence and mortality in Japan, 1958–2013. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 45, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keinan-Boker, L.; et al. Time trends in the incidence and mortality of ovarian cancer in Ireland, Northern Ireland, and Israel, 1994–2013. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, R.; et al. Incidence trends and mortality rates of gastric cancer in Israel. Gastric Cancer 2013, 16, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccarella, S.; et al. The impact of diagnostic changes on the rise in thyroid cancer incidence: a population-based study in selected high-resource countries. Thyroid 2015, 25, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, L.; et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology disease state clinical review: the increasing incidence of thyroid cancer. Endocr. Pract. 2015, 21, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J. Natural products as leads to potential drugs: an old process or the new hope for drug discovery? J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2589–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; et al. Advances in anticoccidial drug halofuginone. Heilongjiang Anim. Husb. Vet. J. 2013, 3, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge, M.; et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of halofuginone, an oral quinazolinone derivative in patients with advanced solid tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, C.-S.; et al. Ch'ang Shan, a Chinese antimalarial herb. Science 1946, 103, 59–59. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, N.P.; Evans, P.; Pines, M. The chemistry and biology of febrifugine and halofuginone. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 1993–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pines, M.; Spector, I. Halofuginone—the multifaceted molecule. Molecules 2015, 20, 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waletzky, E.; Berkelhammer, G.; Kantor, S. Method for Treating Coccidiosis With Quinazolinones. US332 0124 (A), 1967.

- Liu, Y.; et al. Ultrasensitive detection of IgE levels based on magnetic nanocapturer linked immunosensor assay for early diagnosis of cancer. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 1855–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; et al. Halofuginone inhibits TNF-α-induced the migration and proliferation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes from rheumatoid arthritis patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 43, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; et al. Application of nanotechnology in CAR-T-cell immunotherapy. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepfli, J.; Mead, J.; Brockman, J.A. Jr. An alkaloid with high antimalarial activity from Dichroa Febrifuga1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69, 1837–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, S.; et al. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of antimalarial alkaloids febrifugine and isofebrifugine and their biological activity. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 6833–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuel, W.; Gerald, B.; Sidney, K. Method for treating coccidiosis with quinazolinones. 1967, Google Patents.

- De Smet, P.A. The role of plant-derived drugs and herbal medicines in healthcare. Drugs 1997, 54, 801–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepfli, J.; Mead, J.; Brockman, J.A. Alkaloids of Dichroa febrifuga. I. Isol. Degrad. Stud.. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 71, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.; et al. Pharmacology of Ch ‘ang Shan (Dichroa febrifuga), a Chinese antimalarial herb. Nature 1948, 161, 400–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R.I.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from Hydrangea. XIII. The effects of various synthetic quinazolones against Plasmodium lophurae in ducks. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1952, 1, 768–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coatney, G.R.; et al. Studies in human malaria. XXV. Trial of febrifugine, an alkaloid obtained from Dichroa febrifuga lour. against the Chesson strain of Plasmodium vivax. J. Natl. Malar. Soc. 1950, 9, 183–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai, S.; et al. Metabolites of febrifugine and its synthetic analogue by mouse liver S9 and their antimalarial activity against Plasmodium malaria parasite. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 4351–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, P.-L.; Cheng, C.-C. Structural modification of febrifugine. Some methylenedioxy analogs. J. Med. Chem. 1970, 13, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, H.; et al. Exploration of a new type of antimalarial compounds based on febrifugine. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 4698–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. xvi. synthesis of 5-, 6-, 7-, and 8-derivatives with two different substituents. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.; McEVOY, F.J. An Antimalarial Alkaloid from Hydrangea. XXIII. Synth. By Pyridine Approach. II. J. Org. Chem. 1955, 20, 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. XVIII. Derivatives of 4-pyrimidone. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1953, 18, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B.; et al. an antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. XVII. some 5-substituted derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. XV. Synthesis of 5-, 6-, 7-, and 8-derivatives with two identical substituents. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from Hydrangea. XIV. Synthesis of 5-, 6-, 7-, and 8-monosubstituted derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P.; et al. Chemical proteomic profiling with photoaffinity labeling strategy identifies antimalarial targets of artemisinin. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108296. [Google Scholar]

- Marapaka, A.K.; et al. Development of peptidomimetic hydroxamates as PfA-M1 and PfA-M17 dual inhibitors: Biological evaluation and structural characterization by cocrystallization. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2550–2554. [Google Scholar]

- Smullen, S. N.P. McLaughlin, and P. Evans, Chemical synthesis of febrifugine and analogues. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 2199–2220. [Google Scholar]

- Takaya, Y.; et al. New type of febrifugine analogues, bearing a quinolizidine moiety, show potent antimalarial activity against Plasmodium malaria parasite. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 3163–3166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.-F.; et al. Anticoccidial effect of halofuginone hydrobromide against Eimeria tenella with associated histology. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 111, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peeters, J.; et al. Specific serum and local antibody responses against Cryptosporidium parvum during medication of calves with halofuginone lactate. Infect. Immun. 1993, 61, 4440–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugschies, A.; Gässlein, U.; Rommel, M. Comparative efficacy of anticoccidials under the conditions of commercial broiler production and in battery trials. Vet. Parasitol. 1998, 76, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi, T.; Ogasawara, K. A diastereocontrolled synthesis of (+)-febrifugine: a potent antimalarial piperidine alkaloid. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 3193–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samant, B.S.; Sukhthankar, M.G. Synthesis and comparison of antimalarial activity of febrifugine derivatives including halofuginone. Med. Chem. 2009, 5, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, N.P.; Evans, P. Dihydroxylation of vinyl sulfones: Stereoselective synthesis of (+)-and (−)-febrifugine and halofuginone. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, B.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. Ix. Synthesis of 3-[β-keto-γ-(4-hydroxy-2-piperidyl) propyl]-4-quinazolone, an isomer. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. v. some 3-(β-keto-sec-aminoalkyl)-4-quinazolones. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. vii. 3-[β-keto-γ-(5-hydroxy-2-piperidyl) propyl]-4-quinazolone, an isomer. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. vi. a second synthesis of 3-[β-keto-γ-(2-piperidyl)-propyl]-4-quinazolone. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B.; et al. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. Viii. Attempted synthesis of 3-[β-keto-γ-(4-hydroxy-2-piperidyl) propyl]-4-quinazolone by the diketone approach. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B.; Schaub, R.E.; Williams, J.H. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. x. synthesis of 3-[β-keto-γ-(4-methyl-2-pyrrolidyl) propyl]-4-quinazolone. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B.; SCHAUB, R.E.; WILLIAMS, J.H. An antimalarial alkaloid from hydrangea. Xi. Synthesis of 3-[β-keto-γ-(3-and 4-hydroxymethyl-2-pyrrolidyl) propyl]-4-quinazolones. J. Org. Chem. 1952, 17, 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, M.R.; et al. (2R, 3S)-(+)-and (2S, 3R)-(−)-Halofuginone lactate: Synthesis, absolute configuration, and activity against Cryptosporidium parvum. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 4140–4143. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, M.; et al. Stereocontrolled synthesis of a potent antimalarial alkaloid,(+)-febrifugine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 6221–6223. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidan, R.K.; Smullen, S.; Evans, P. Asymmetric synthesis of (+)-and (−)-deoxyfebrifugine and deoxyhalofuginone. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 6433–6435. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, M.; Cruickshank, P.A. Febrifugine antimalarial agents. I. Pyridine Analog. Febrifugine. J. Med. Chem. 1970, 13, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, Y.; et al. Synthesis and antimalarial activity of febrifugine derivatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 721–725. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-S. Synthesis and antimalarial activity of dl-deoxyfebrifugine. Heterocycles 1999, 51, 1869–1875. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, H.; et al. Synthesis of febrifugine derivatives and development of an effective and safe tetrahydroquinazoline-type antimalarial. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 76, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, H.; et al. Potent antimalarial febrifugine analogues against the plasmodium malaria parasite. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2563–2570. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, Y.; et al. Re-revision of the stereo structure of piperidine lactone, an intermediate in the synthesis of febrifugine. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 1011–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.; et al. Identification and characterization of potential antioxidant components in Isodon amethystoides (Benth.) Hara tea leaves by UPLC-LTQ-Orbitrap-MS. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 148, 111961. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; et al. Febrifugine analogue compounds: synthesis and antimalarial evaluation. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; et al. Synthesis and evaluation of 4-quinazolinone compounds as potential antimalarial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 3864–3869. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, H.D.T.; et al. Synthesis of febrifuginol analogues and evaluation of their biological activities. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 7226–7228. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Chen, P.; Liu, G. Pd (II)-catalyzed aminofluorination of alkenes in total synthesis 6-(R)-fluoroswainsonine and 5-(R)-fluorofebrifugine. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 960–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perali, R.S.; Bandi, A. Stereoselective total synthesis of all the stereoisomers of (+)- and (−)-febrifugine and halofuginone. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020, 61, 152151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.; et al. Target identification for small bioactive molecules: finding the needle in the haystack. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2744–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.B.; et al. Bioactive molecules: current trends in discovery, synthesis, delivery and testing. IeJSME 2013, 7 (Suppl. S1), S32–S46. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehl Jr, F.A. C.F. Spencer, and K. Folkers, Alkaloids of Dichroa Febrifuga Lour. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 2091–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickwedde, L.H.; et al. An Appeal. Science 1946, 103, 59–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahiduzzaman, M.; et al. Combination of cell culture and quantitative PCR for screening of drugs against Cryptosporidium parvum. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 162, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, F.L.; et al. An antifungal agent inhibits an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by trapping tRNA in the editing site. science 2007, 316, 1759–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibba, M.; Söll, D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000, 69, 617–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; et al. Structure-Guided Design of Halofuginone Derivatives as ATP-Aided Inhibitors Against Bacterial Prolyl-tRNA Synthetase. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 15840–15855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allport, J.; et al. Efficacy of mupirocin, neomycin and octenidine for nasal Staphylococcus aureus decolonisation: a retrospective cohort study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, J. and P. Schimmel, Inhibitors of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases as novel anti-infectives. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2000, 9, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, D.A.; Carter, G.P.; Howden, B.P. Current and emerging topical antibacterials and antiseptics: agents, action, and resistance patterns. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 827–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaduk, J.A.; Gates-Rector, S.; Blanton, T.N. Crystal structure of halofuginone hydrobromide, C16H18BrClN3O3Br. Powder Diffr. 2023, 38, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, A.M. Determination of halofuginone hydrobromide in medicated animal feeds. Analyst 1983, 108, 1252–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; et al. Therapeutic poly(amino acid)s as drug carriers for cancer therapy. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107953. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, Q.; Liu, Z. A novel synthesis of the efficient anti-coccidial drug halofuginone hydrobromide. Molecules 2017, 22, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, T. Hydrogen-bond distances to halide ions in organic and organometallic crystal structures: up-to-date database study. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 1998, 54, 456–463. [Google Scholar]

- Kortagere, S.; Ekins, S.; Welsh, W.J. Halogenated ligands and their interactions with amino acids: implications for structure–activity and structure–toxicity relationships. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2008, 27, 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Thallapally, P.K.; Nangia, A. A Cambridge Structural Database analysis of the C–H⋯ Cl interaction: C–H⋯ Cl− and C–H⋯ Cl–M often behave as hydrogen bonds but C–H⋯ Cl–C is generally a van der Waals interaction. CrystEngComm 2001, 3, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, M.; et al. 3-(4-Fluoropiperidin-3-yl)-2-phenylindoles as high affinity, selective, and orally bioavailable h5-HT2A receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 1603–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niel, M.B.; et al. Fluorination of 3-(3-(piperidin-1-yl) propyl) indoles and 3-(3-(piperazin-1-yl) propyl) indoles gives selective human 5-HT1D receptor ligands with improved pharmacokinetic profiles. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 2087–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblum, S.B.; et al. Discovery of 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-(3 R)-[3-(4-fluorophenyl)-(3 S)-hydroxypropyl]-(4 S)-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-azetidinone (SCH 58235): a designed, potent, orally active inhibitor of cholesterol absorption. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-J.; et al. Fluorine substitution can block CYP3A4 metabolism-dependent inhibition: identification of (S)-N-[1-(4-fluoro-3-morpholin-4-ylphenyl) ethyl]-3-(4-fluorophenyl) acrylamide as an orally bioavailable KCNQ2 opener devoid of CYP3A4 metabolism-dependent inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 3778–3781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, E.L.; et al. Oxidation of Bromide by the Human Leukocyte Enzymes Myeloperoxidase and Eosinophil Peroxidase: FORMATION OF BROMAMINES (∗). J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 2906–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Rousseau, J.; Van Lier, J.E. 7. alpha.-Methyl-and 11. beta.-ethoxy-substitution of iodine-125-labeled [125I] 16. alpha.-iodoestradiol: effect on estrogen receptor-mediated target tissue uptake. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.H.; et al. Crystallographic evidence for isomeric chromophores in 3-fluorotyrosyl-green fluorescent protein. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 720–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; et al. Stabilization of coiled-coil peptide domains by introduction of trifluoroleucine. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 2790–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; et al. Fluorous effect in proteins: de novo design and characterization of a four-α-helix bundle protein containing hexafluoroleucine. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 16277–16284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamora, A.; et al. Anticancer activity of halofuginone in a preclinical model of osteosarcoma: inhibition of tumor growth and lung metastases. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 14413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.; et al. Halofuginone attenuates osteoarthritis by inhibition of TGF-β activity and H-type vessel formation in subchondral bone. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; et al. Analysis of the anti-coccidial drug, halofuginone, in chicken tissue and chicken feed using high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1981, 212, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pines, M. Halofuginone for fibrosis, regeneration and cancer in the gastrointestinal tract. World J. Gastroenterol. : WJG 2014, 20, 14778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.L.; et al. Halofuginone induces the apoptosis of breast cancer cells and inhibits migration via downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.-H.; et al. DT-13 attenuates human lung cancer metastasis via regulating NMIIA activity under hypoxia condition. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; et al. Computational pharmacology and bioinformatics to explore the potential mechanism of Schisandra against atherosclerosis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 150, 112058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán-Rodríguez, J.J.; et al. Plant antimicrobial peptides as potential anticancer agents. BioMed Res. Int. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; et al. ATP-directed capture of bioactive herbal-based medicine on human tRNA synthetase. Nature 2013, 494, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; et al. Antimalarial activities and therapeutic properties of febrifugine analogs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E.R.; Mazitschek, R.; Clardy, J. Characterization of Plasmodium liver stage inhibition by halofuginone. ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; et al. Structure-guided optimization and mechanistic study of a class of quinazolinone-threonine hybrids as antibacterial ThrRS inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 207, 112848. [Google Scholar]

- Tye, M.A.; et al. Elucidating the path to Plasmodium prolyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors that overcome halofuginone resistance. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fingleton, B.; Matrisian, L.M. Matrix metalloproteinases as targets for therapy in Kaposi sarcoma. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2001, 13, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jain, V.; et al. Structural and functional analysis of the anti-malarial drug target prolyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Struct. Funct. Genom. 2014, 15, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, D.R.; et al. The prolyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor halofuginone inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection. bioRxiv, 2021: p. 2021.03. 22.436522.

- Fitz-Coy, S.; Edgar, S. Pathogenicity and control of Eimeria mitis infections in broiler chickens. Avian Diseases, 1992: p. 44-48.

- Silverlås, C.; Björkman, C.; Egenvall, A. Systematic review and meta-analyses of the effects of halofuginone against calf cryptosporidiosis. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009, 91, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; et al. A novel therapeutic vaccine based on graphene oxide nanocomposite for tumor immunotherapy. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 4089–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; et al. Targeted intervention of natural medicinal active ingredients and traditional Chinese medicine on epigenetic modification: possible strategies for prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis. Phytomedicine 2024, 122, 155139. [Google Scholar]

- De Waele, V.; et al. Control of cryptosporidiosis in neonatal calves: use of halofuginone lactate in two different calf rearing systems. Prev. Vet. Med. 2010, 96, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.F.; et al. Halofuginone down-regulates Smad3 expression and inhibits the TGFbeta-induced expression of fibrotic markers in human corneal fibroblasts. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 479. [Google Scholar]

- Pines, M. Targeting TGFβ signaling to inhibit fibroblast activation as a therapy for fibrosis and cancer: effect of halofuginone. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2008, 3, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pines, M.; Nagler, A. Halofuginone: a novel antifibrotic therapy. Gen. Pharmacol. : Vasc. Syst. 1998, 30, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, K.; et al. Ginsenoside Rg1 ameliorates blood–brain barrier disruption and traumatic brain injury via attenuating macrophages derived exosomes miR-21 release. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 3493–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pines, M.; et al. Reduction in dermal fibrosis in the tight-skin (Tsk) mouse after local application of halofuginone. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 62, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Schaffer, F.; et al. Inhibition of collagen synthesis and changes in skin morphology in murine graft-versus-host disease and tight skin mice: effect of halofuginone. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1996, 106, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagler, A.; et al. Reduction in pulmonary fibrosis in vivo by halofuginone. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 154, 1082–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, A.; et al. Suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma growth in mice by the alkaloid coccidiostat halofuginone. Eur. J. Cancer 2004, 40, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, A.; et al. Halofuginone-an inhibitor of collagen type I synthesis-prevents postoperative formation of abdominal adhesions. Ann. Surg. 1998, 227, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, M.; et al. Halofuginone, a specific inhibitor of collagen type I synthesis, prevents dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 1997, 27, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zion, O.; et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor β signaling by halofuginone as a modality for pancreas fibrosis prevention. Pancreas 2009, 38, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, K.D.; et al. Functional resolution of fibrosis in mdx mouse dystrophic heart and skeletal muscle by halofuginone. Am. J. Physiol. -Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H1550–H1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromes, Y.; et al. Inhibition of Fibrosis and Improvement of Function of the Myopathic Hamster Cardiac Muscle by Halofuginone. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2014, 20, 2351–2383. [Google Scholar]

- Roffe, S.; et al. Halofuginone inhibits Smad3 phosphorylation via the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK pathways in muscle cells: effect on myotube fusion. Exp. Cell Res. 2010, 316, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spector, I.; et al. Involvement of host stroma cells and tissue fibrosis in pancreatic tumor development in transgenic mice. PLoS One 2012, 7, e41833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnainsky, Y.; et al. Halofuginone, an inhibitor of collagen synthesis by rat stellate cells, stimulates insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 synthesis by hepatocytes. J. Hepatol. 2004, 40, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, A.S. Helper (TH1, TH2, TH17) and regulatory cells (Treg, TH3, NKT) in rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatol. Clin. 2009, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; et al. Discovery of novel tRNA-amino acid dual-site inhibitors against threonyl-tRNA synthetase by fragment-based target hopping. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 187, 111941. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrella, D.; et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 in protective immunity to vaginal candidiasis. PloS One 2011, 6, e22770. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.M.; Vanderberg, J.P. Specific inflammatory cell infiltration of hepatic schizonts in BALB/c mice immunized with attenuated Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites. Int. Immunol. 1992, 4, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; et al. The Effect of Antifibrotic Drug Halofugine on Th17 Cells in Concanavalin A-Induced Liver Fibrosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 2014, 79, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.L.-H. Prediction of fibrosis progression in chronic viral hepatitis. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2014, 20, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.P.; et al. Halofuginone, a promising drug for treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 3373–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; et al. Fighting hypoxia to improve photodynamic therapy-driven immunotherapy: Alleviating, exploiting and disregarding. Chinese Chemical Letters, 2024: p. 109957.

- Khan, G.J.; et al. Non-Muscle Myosin IIC as a Prognostic and Therapeutic Target in Cancer. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2024, 20, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; et al. Halofuginone prevents extracellular matrix deposition in diabetic nephropathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 379, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabgah, A.G.; Fattahi, E.; Shahneh, F.Z. Interleukin-17 in human inflammatory diseases. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. /Postępy Dermatol. I Alergol. 2014, 31, 256–261. [Google Scholar]

- Leiba, M.; et al. Halofuginone inhibits NF-κB and p38 MAPK in activated T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 80, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, G.J.; et al. Thymus as Incontrovertible Target of Future Immune Modulatory Therapeutics. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdin, F.; et al. Antibiotic therapy in pyogenic meningitis in paediatric patients. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2013, 23, 703–707. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; et al. The protective effects of a D-tetra-peptide hydrogel adjuvant vaccine against H7N9 influenza virus in mice. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; et al. Halofuginone ameliorates systemic lupus erythematosus by targeting Blk in myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 114, 109487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.W. Molecular Mechanism of the Immunomodulatory Drug Halofuginone. 2016: Harvard University.

- Chen, L.; et al. Biomaterial-induced macrophage polarization for bone regeneration. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, K.; et al. Extracellular vesicle-derived miR-146a as a novel crosstalk mechanism for high-fat induced atherosclerosis by targeting SMAD4. J. Adv. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.-F.; et al. Autophagy modulators from traditional Chinese medicine: Mechanisms and therapeutic potentials for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 194, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suman, S.; et al. The pro-apoptotic role of autophagy in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zocchi, M.R.; Poggi, A. Targeting the microenvironment in hematological malignancies: how to condition both stromal and effector cells to overcome cancer spreading. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 5172–5173. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; et al. DT-13, a saponin monomer of dwarf lilyturf tuber, induces autophagy and potentiates anti-cancer effect of nutrient deprivation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 781, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; et al. Emerging nanomedicine and prodrug delivery strategies for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 4449–4460. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, K.-f.; et al. Salicin from Alangium chinense ameliorates rheumatoid arthritis by modulating the Nrf2-HO-1-ROS pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6073–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, A.; Jung, K.-W.; Won, Y.-J. Colorectal cancer mortality in Hong Kong of China, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. World J. Gastroenterol. : WJG 2013, 19, 979. [Google Scholar]

- Koseoglu, S.; et al. AKT1, AKT2 and AKT3-dependent cell survival is cell line-specific and knockdown of all three isoforms selectively induces apoptosis in 20 human tumor cell lines. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007, 6, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francipane, M.G.; Lagasse, E. mTOR pathway in colorectal cancer: an update. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ucaryilmaz Metin, C.; Ozcan, G. Comprehensive bioinformatic analysis reveals a cancer-associated fibroblast gene signature as a poor prognostic factor and potential therapeutic target in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.S.; Klostergaard, J. Chapter 7 - STAT3 Signaling in Cancer: Small Molecule Intervention as Therapy?, in Anti-Angiogenesis Drug Discovery and Development, R. Atta ur and M.I. Choudhary, Editors. 2014, Elsevier. p. 216-267.

- Khan, G.J.; et al. Versatility of cancer associated fibroblasts: commendable targets for anti-tumor therapy. Curr. Drug Targets 2018, 19, 1573–1588. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; et al. mTOR signaling pathway is a target for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 16, 2617–2628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin up-regulation of pyruvate kinase isoenzyme type M2 is critical for aerobic glycolysis and tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 4129–4134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. science 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Yalcin, S.; et al. ROS-mediated amplification of AKT/mTOR signalling pathway leads to myeloproliferative syndrome in Foxo3−/− mice. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 4118–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düvel, K.; et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; et al. A selective HK2 degrader suppresses SW480 cancer cell growth by degrading HK2. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109264. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, R.C. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, NADPH, and cell survival. IUBMB Life 2012, 64, 362–369. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, D.; Miyamoto, S. Hexokinase II integrates energy metabolism and cellular protection: Akting on mitochondria and TORCing to autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; et al. Manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency triggers mitochondrial uncoupling and the Warburg effect. Oncogene 2015, 34, 4229–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Q.; et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel phthalazinone acridine derivatives as dual PARP and Topo inhibitors for potential anticancer agents. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 404–408. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of piperidyl benzimidazole carboxamide derivatives as potent PARP-1 inhibitors and antitumor agents. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.O.; et al. The Global Breast Cancer Initiative: a strategic collaboration to strengthen health care for non-communicable diseases. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huyen, C.T.T.; et al. Chemical constituents from Cimicifuga dahurica and their anti-proliferative effects on MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Molecules 2018, 23, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari, A.; et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer☆. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1475–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Viale, G.; et al. Retrospective study to estimate the prevalence and describe the clinicopathological characteristics, treatments received, and outcomes of HER2-low breast cancer. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 101615. [Google Scholar]

- Schalper, K.A.; et al. A retrospective population-based comparison of HER2 immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization in breast carcinomas: impact of 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists criteria. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2014, 138, 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; et al. DT-13 inhibits breast cancer cell migration via non-muscle myosin II-A regulation in tumor microenvironment synchronized adaptations. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 22, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenblick, A.; et al. STAT3 activation in HER2-positive breast cancers: Analysis of data from a large prospective trial. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuan, K.; et al. Complement C3 overexpression activates JAK2/STAT3 pathway and correlates with gastric cancer progression. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F.; et al. The autophagy-independent role of BECN1 in colorectal cancer metastasis through regulating STAT3 signaling pathway activation. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- You, W.; et al. IL-26 promotes the proliferation and survival of human gastric cancer cells by regulating the balance of STAT1 and STAT3 activation. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63588. [Google Scholar]

- Tajmohammadi, I.; et al. Identification of Nrf2/STAT3 axis in induction of apoptosis through sub-G 1 cell cycle arrest mechanism in HT-29 colon cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 14035–14043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lau, A.; et al. Arsenic inhibits autophagic flux, activating the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway in a p62-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 2436–2446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-J.; et al. Interaction of Nrf2 with dimeric STAT3 induces IL-23 expression: Implications for breast cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2021, 500, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; et al. Aberrant expression of IL-23/IL-23R in patients with breast cancer and its clinical significance. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 4639–4644. [Google Scholar]

- Betti, M.; et al. Genetic predisposition for malignant mesothelioma: A concise review. Mutat. Res. /Rev. Mutat. Res. 2019, 781, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, T.A.; et al. Novel insights into mesothelioma biology and implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 475–488. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, X.; et al. p38 and JNK MAPK pathways control the balance of apoptosis and autophagy in response to chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Lett. 2014, 344, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez, P.; et al. Halofuginone inhibits TGF-β/BMP signaling and in combination with zoledronic acid enhances inhibition of breast cancer bone metastasis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 86447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, Y.; et al. Halofuginone induces matrix metalloproteinases in rat hepatic stellate cells via activation of p38 and NFκB. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 15090–15098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, T.J.; et al. Halofuginone-induced amino acid starvation regulates Stat3-dependent Th17 effector function and reduces established autoimmune inflammation. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 2167–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; et al. DT-13 inhibits cancer cell migration by regulating NMIIA indirectly in the tumor microenvironment. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.; et al. The potential mechanism of Isodon suzhouensis against COVID-19 via EGFR/TLR4 pathways. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiroglu-Zergeroglu, A.; et al. Anticarcinogenic effects of halofuginone on lung-derived cancer cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2020, 44, 1934–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perepelyuk, M.; et al. Hepatic stellate cells and portal fibroblasts are the major cellular sources of collagens and lysyl oxidases in normal liver and early after injury. Am. J. Physiol. -Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013, 304, G605–G614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; et al. Rural–urban, sex variations, and time trend of primary liver cancer incidence in China, 1988–2005. Eur. J. Cancer prevention 2013, 22, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.S.; Wang, W.H.; Li, F.Q. Combination of interventional adenovirus-p53 introduction and ultrasonic irradiation in the treatment of liver cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 9, 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; et al. Preventive effect of halofuginone on concanavalin A-induced liver fibrosis. PLoS One 2013, 8, e82232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.H.; et al. Total flavonoid extract from Dracocephalum moldavica L. improves pulmonary fibrosis by reducing inflammation and inhibiting the hedgehog signaling pathway. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 2745–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; et al. Determination of the anti-oxidative stress mechanism of Isodon suzhouensis leaves by employing bioinformatic and novel research technology. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 3520–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, S.; et al. Mule/Huwe1/Arf-BP1 suppresses Ras-driven tumorigenesis by preventing c-Myc/Miz1-mediated down-regulation of p21 and p15. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1101–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; et al. Expression of the p12 subunit of human DNA polymerase δ (Pol δ), CDK inhibitor p21WAF1, Cdt1, cyclin A, PCNA and Ki-67 in relation to DNA replication in individual cells. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 3529–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.a.; Chai, R.; Yu, X. Downregulation of NIT2 inhibits colon cancer cell proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest through the caspase-3 and PARP pathways. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 35, 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, L.; Hornby, D. c-IAP1 binds and processes PCSK9 protein: linking the c-IAP1 in a TNF-α pathway to PCSK9-mediated LDLR degradation pathway. Molecules 2012, 17, 12086–12101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.C.; Bathina, M.; Fiscus, R.R. Cyclic GMP/protein kinase G type-Iα (PKG-Iα) signaling pathway promotes CREB phosphorylation and maintains higher c-IAP1, livin, survivin, and Mcl-1 expression and the inhibition of PKG-Iα kinase activity synergizes with cisplatin in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 113, 3587–3598. [Google Scholar]

- Jilany Khan, G.; et al. TGF-β1 causes EMT by regulating N-Acetyl glucosaminyl transferases via downregulation of non muscle myosin II-A through JNK/P38/PI3K pathway in lung cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2018, 18, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwibasira Rudinga, G.; Khan, G.J.; Kong, Y. Protease-activated receptor 4 (PAR4): a promising target for antiplatelet therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, K.; et al. Protective effects of Isodon Suzhouensis extract and glaucocalyxin A on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease through SOCS3–JAKs/STATs pathway. Food Front. 2023, 4, 511–523. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; et al. Interdependent and independent multidimensional role of tumor microenvironment on hepatocellular carcinoma. Cytokine 2018, 103, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koon, H.B.; et al. Phase ii aids malignancy consortium trial of topical halofuginone in aids-related kaposi’s sarcoma. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2011, 56, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, L.; et al. Halofuginone for cancer treatment: A systematic review of efficacy and molecular mechanisms. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 98, 105237. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, G.J.; et al. Pharmacological effects and potential therapeutic targets of DT-13. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jonge, M.J.A.; et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of halofuginone, an oral quinazolinone derivative in patients with advanced solid tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, M.; et al. Halofuginone to treat fibrosis in chronic graft-versus-host disease and scleroderma. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003, 9, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomazini, B.M.; et al. Halofuginone for non-hospitalized adult patients with COVID-19 a multicenter, randomized placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. The HALOS trial. Plos One 2024, 19, e0299197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharate, S.S. Modulation of biopharmaceutical properties of acidic drugs using cationic counterions: A critical analysis of FDA-approved pharmaceutical salts. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 607, 120993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmali, A.; Bharate, S.S. Phosphate moiety in FDA-approved pharmaceutical salts and prodrugs. Drug Dev. Res. 2022, 83, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bharate, S.S. Carboxylic acid counterions in FDA-approved pharmaceutical salts. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 1307–1326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kramer, S.F.; Flynn, G.L. Solubility of Organic Hydrochlorides. J. Pharm. Sci. 1972, 61, 1896–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Serajuddin, A.T. Salt formation to improve drug solubility. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A.; et al. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Berge, S.M.; Bighley, L.D.; Monkhouse, D.C. Pharmaceutical salts. J. Pharm. Sci. 1977, 66, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain Mithu, M.S.; et al. Advanced methodologies for pharmaceutical salt synthesis. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 1358–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Bharate, S.S. Recent developments in pharmaceutical salts: FDA approvals from 2015 to 2019. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 384–398. [Google Scholar]

- Bharate, S.S.; Vishwakarma, R.A. Impact of preformulation on drug development. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2013, 10, 1239–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastin, R.J.; Bowker, M.J.; Slater, B.J. Salt selection and optimisation procedures for pharmaceutical new chemical entities. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2000, 4, 427–435. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, L.; Amin, A.; Bansal, A.K. An overview of automated systems relevant in pharmaceutical salt screening. Drug Discov. Today 2007, 12, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; et al. Salt screening and characterization of ciprofloxacin. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorson, M.R.; et al. A microfluidic platform for pharmaceutical salt screening. Lab A Chip 2011, 11, 3829–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; et al. Crystalline form information from multiwell plate salt screening by use of Raman microscopy. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, D.E.; et al. Unraveling complexity in the solid form screening of a pharmaceutical salt: Why so many forms? Why so few? Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 5349–5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, W.-Q.T. Salt screening and selection: new challenges and considerations in the modern pharmaceutical research and development paradigm. Developing solid oral dosage forms,.

- Barron, K.; et al. Comparative evaluation of the in vitro effects of hydralazine and hydralazine acetonide on arterial smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1977, 61, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, U.; et al. The first-in-human study of the hydrogen sulfate (Hyd-sulfate) capsule of the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886): a phase I open-label multicenter trial in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 1613–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsiczky, B.; et al. The effect of clopidogrel besylate and clopidogrel hydrogensulfate on platelet aggregation in patients with coronary artery disease: a retrospective study. Thromb. Res. 2012, 129, 700–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggadike, K. Fluticasone furoate/fluticasone propionate–different drugs with different properties. Clin. Respir. J. 2011, 5, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; et al. Fluorine-containing drugs approved by the FDA in 2019. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 2401–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitipamula, S.; et al. Polymorphs, salts, and cocrystals: what’s in a name? Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 2147–2152. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, D.P.; Johnson, B.F.; Perry, R. Prolonged hallucinations following a modest overdose of tripelennamine. Clin. Toxicol. 1980, 16, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bjerre, C.; Björk, E.; Camber, O. Bioavailability of the sedative propiomazine after nasal administration in rats. Int. J. Pharm. 1996, 144, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, K.B.; Cullen, L.F. Propiomazine Hydrochloride, in Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances. 1973, Elsevier. p. 439-466.

- Florey, K. Triflupromazine Hydrochloride, in Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances, K. Florey, Editor. 1973, Academic Press. p. 523-550.

- Rifkin, A.; et al. Fluphenazine decanoate, fluphenazine hydrochloride given orally, and placebo in remitted schizophrenics: I. Relapse rates after one year. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1977, 34, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Surov, A.O.; et al. Pharmaceutical salts of ciprofloxacin with dicarboxylic acids. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 77, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Al Omari, M.M.; et al. Moxifloxacin hydrochloride. Profiles of drug substances, excipients and related methodology 2014, 39, 299–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, T.D. Pentazocine, in Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances, K. Florey, Editor. 1984, Academic Press. p. 361-416.

- Miller, R.R. Clinical effects of pentazocine in hospitalized medical patients. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1975, 15, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, Y. Flavoxate Hydrochloride, in Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances and Excipients, H.G. Brittain, Editor. 2001, Academic Press. p. 77-115.

- Elhesaisy, N.; Swidan, S. Trazodone loaded lipid core poly (ε-caprolactone) nanocapsules: development, characterization and in vivo antidepressant effect evaluation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Hettche, H.; et al. Salts of azelastine having improved solubility. 1999, Google Patents.

- Bariakar, U.V.; Patel, U.N. Pralidoxime Chloride, in Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances, K. Florey, Editor. 1988, Academic Press. p. 533-569.

- Wahl, J.W.; Tyner, G.S. Echothiophate Iodide*: The Effect of 0.0625% Solution on Blood Cholinesterase. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1965, 60, 419–425. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilonius, S.-M.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of pyridostigmine in man. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1980, 18, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.R.; Holtzman, S.G. Opiate antagonists: central sites of action in suppressing water intake of the rat. Brain Res. 1981, 221, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Teoh, H.L. Galanthamine from snowdrop—the development of a modern drug against Alzheimer’s disease from local Caucasian knowledge. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 92, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichl, R. New thienylcarboxylic acid esters of aminoalcohols, their quarternary products, their preparation and use of the compounds. 1999, Google Patents.

- Banholzer, R.; Pfrengle, W.; Sieger, P. Novel tiotropium salts, process for the preparation and pharmaceutical compositions thereof. 2005, Google Patents.

- Lenke, D.; et al. Basically substituted benzyl phthalazone derivatives, acid salts thereof and process for the production thereof. 1974, Google Patents.

- Van Leeuwen, F.R.; Sangster, B.; Hildebrandt, A.G. The toxicology of bromide ion. CRC Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1987, 18, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D.E. In silico prediction of blood–brain barrier permeation. Drug Discov. Today 2003, 8, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, D.P.; Holm, R.; De Diego, H.L. Use of pharmaceutical salts and cocrystals to address the issue of poor solubility. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 453, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, D.P.; et al. The utility of sulfonate salts in drug development. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 2948–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-L.; et al. Preformulation investigation I: relation of salt forms and biological activity of an experimental antihypertensive. J. Pharm. Sci. 1972, 61, 1418–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinnider, M.A. Invalid SMILES are beneficial rather than detrimental to chemical language models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, P.; Rohde, B.; Selzer, P. Fast calculation of molecular polar surface area as a sum of fragment-based contributions and its application to the prediction of drug transport properties. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3714–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veber, D.F.; et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, G.J.; et al. Understanding and responsiveness level about cervical cancer and its avoidance among young women of Pakistan. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 4877–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; et al. Recent progress in theranostic microbubbles. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.C.; et al. Trends in the approval of cancer therapies by the FDA in the twenty-first century. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.; Sharma, A. Prospects of halofuginone as an antiprotozoal drug scaffold. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 2586–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; et al. The role of halofuginone in fibrosis: more to be explored? J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017, 102, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.-n.; et al. -n.; et al. Using halofuginone–silver thermosensitive nanohydrogels with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties for healing wounds infected with Staphylococcus aureus. Life Sci. 2024, 339, 122414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; et al. Adhesive chitosan-based hydrogel assisted with photothermal antibacterial property to prompt mice infected skin wound healing. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.J.; et al. Ciprofloxacin: The frequent use in poultry and its consequences on human health. Prof. Med. J. 2015, 22, 001–005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-H.; Fu, J.; Sun, D.-Q. Halofuginone alleviates acute viral myocarditis in suckling BALB/c mice by inhibiting TGF-β1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 473, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, I.; et al. Assessment of the broad-spectrum host targeting antiviral efficacy of halofuginone hydrobromide in human airway, intestinal and brain organotypic models. Antivir. Res. 2024, 222, 105798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Extensible and swellable hydrogel-forming microneedles for deep point-of-care sampling and drug deployment. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108103. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, V.; et al. Structure of prolyl-tRNA synthetase-halofuginone complex provides basis for development of drugs against malaria and toxoplasmosis. Structure 2015, 23, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sevilla, L.M.; Pérez, P. Glucocorticoids and Glucocorticoid-Induced-Leucine-Zipper (GILZ) in Psoriasis. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; et al. Halofuginone functions as a therapeutic drug for chronic periodontitis in a mouse model. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2020, 34, 2058738420974893. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr, M.; et al. Quinazolinone Alkaloid Febrifugine and Its Analogues To Control Phytopathogenic Diseases Caused by Oomycete Fungi. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202101522. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; et al. Anti-phytophthora activity of halofuginone and the corresponding mode of action. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 12364–12371. [Google Scholar]

- Kunimi, H.; et al. A novel HIF inhibitor halofuginone prevents neurodegeneration in a murine model of retinal ischemia-reperfusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; et al. Inhibition of IL-17 signaling in macrophages underlies the anti-arthritic effects of halofuginone hydrobromide: Network pharmacology, molecular docking, and experimental validation. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Miwa, Y.; et al. Halofuginone prevents outer retinal degeneration in a mouse model of light-induced retinopathy. Plos One 2024, 19, e0300045. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; et al. Halofuginone Inhibits Osteoclastogenesis and Enhances Osteoblastogenesis by Regulating Th17/Treg Cell Balance in Multiple Myeloma Mice with Bone Lesions. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.; et al. Integrated Stress Response Potentiates Ponatinib-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Circ. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; et al. Nanoparticles-based lateral flow strip for halofuginone ultrasensitive detection in chicken and beef. Food Biosci. 2024, 104100. [Google Scholar]

- Semukunzi, H.; et al. IDH mutations associated impact on related cancer epidemiology and subsequent effect toward HIF-1α. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 89, 805–811. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; et al. Halofugine prevents cutaneous graft versus host disease by suppression of Th17 differentiation. Hematology 2012, 17, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozmen, E.; Demir, T.D.; Ozcan, G. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: protagonists of the tumor microenvironment in gastric cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1340124. [Google Scholar]

- Tossetta, G.; et al. Role of natural and synthetic compounds in modulating NRF2/KEAP1 signaling pathway in prostate cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, R.; et al. Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 Depletion Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Gemcitabine via Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 3a1 Repression. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2021, 379, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lv, T.; et al. Halofuginone enhances the anti-tumor effect of ALA-PDT by suppressing NRF2 signaling in cSCC. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 37, 102572. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; et al. An injectable mPEG-PDLLA microsphere/PDLLA-PEG-PDLLA hydrogel composite for soft tissue augmentation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2486–2490. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Wu, X. Halofuginone inhibits cell proliferation and AKT/mTORC1 signaling in uterine leiomyoma cells. Growth Factors 2022, 40, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; et al. Theranostic mesoporous platinum nanoplatform delivers halofuginone to remodel extracellular matrix of breast cancer without systematic toxicity. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2023, 8, e10427. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, R.; et al. Halofuginone-guided nano-local therapy: Nano-thermosensitive hydrogels for postoperative metastatic canine mammary carcinoma with scar removal. International Journal of Pharmaceutics: X 2024, 100241.

- Cai, C.; et al. In situ wound sprayable double-network hydrogel: Preparation and characterization. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 1963–1969. [Google Scholar]

- de Figueiredo-Pontes, L.L.; et al. Halofuginone has anti-proliferative effects in acute promyelocytic leukemia by modulating the transforming growth factor beta signaling pathway. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26713. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; et al. 5-Fluorouracil Combined with Rutaecarpine Synergistically Suppresses the Growth of Colon Cancer Cells by Inhibiting STAT3. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2023, 993–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; et al. Polysaccharide-based supramolecular drug delivery systems mediated via host-guest interactions of cucurbiturils. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 949–953. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; et al. Halofuginone sensitizes lung cancer organoids to cisplatin via suppressing PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 773048. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, R.-H.; et al. Cell death mechanisms induced by synergistic effects of halofuginone and artemisinin in colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 19, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, H.; et al. Halofuginone micelle nanoparticles eradicate Nrf2-activated lung adenocarcinoma without systemic toxicity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 187, 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, R.; et al. Orally administered halofuginone-loaded TPGS polymeric micelles against triple-negative breast cancer: enhanced absorption and efficacy with reduced toxicity and metastasis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 2475–2491. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, P.; Skinner, F. Pharmaceutical aspects of the api salt form. Pharmaceutical Salts: Properties, Selection, and Use, 2nd ed.; Stahl, PH, Wermuth, CG, Eds, 2011: p. 85-124.

- Peresypkin, A.; et al. Discovery of a stable molecular complex of an API with HCl: a long journey to a conventional salt. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 3721–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.; et al. Revealing the synergistic mechanism of multiple components in compound fengshiding capsule for rheumatoid arthritis therapeutics by network pharmacology. Curr. Mol. Med. 2019, 19, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, P.L. Salt selection for basic drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 1986, 33, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).