Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Terpenes are the largest category of specialized metabolites. Aerobic endospore-forming bacteria (AEFB), a diverse group of microorganisms, can thrive in various habitats and produce specialized metabolites, including terpenes. This study investigates the potential for terpene biosynthesis in 10 AEFB strain whole-genome sequences by performing bioinformatics analyses to identify genes associated with these isoprene biosynthesis pathways. Specifically, we focused on the sequences coding for enzymes in the methylerythritol-phosphate (MEP) pathway and the polyprenyl synthase family, which play crucial roles in synthesizing terpene precursors together with terpene synthases. Comparative analysis revealed a unique genetic architecture of these biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Our results indicated that some strains possessed the complete genetic machinery required to produce terpenes such as squalene, hopanoids, and carotenoids. We also reconstructed phylogenetic trees based on the amino acid sequences of terpene synthases, which aligned with the phylogenetic relationships inferred from the whole-genome sequences, suggesting the production of terpenes is an ancestor property in AEFB. Our findings highlight the importance of genome mining as a powerful tool for discovering new biological activities. Furthermore, this research lays the groundwork for future investigations to enhance our understanding of terpene biosynthesis in AEFB and the potential applications of these Brazilian environmental strains.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains

Ethics Statement

Sequencing, Assembly, Annotation, and Data Availability

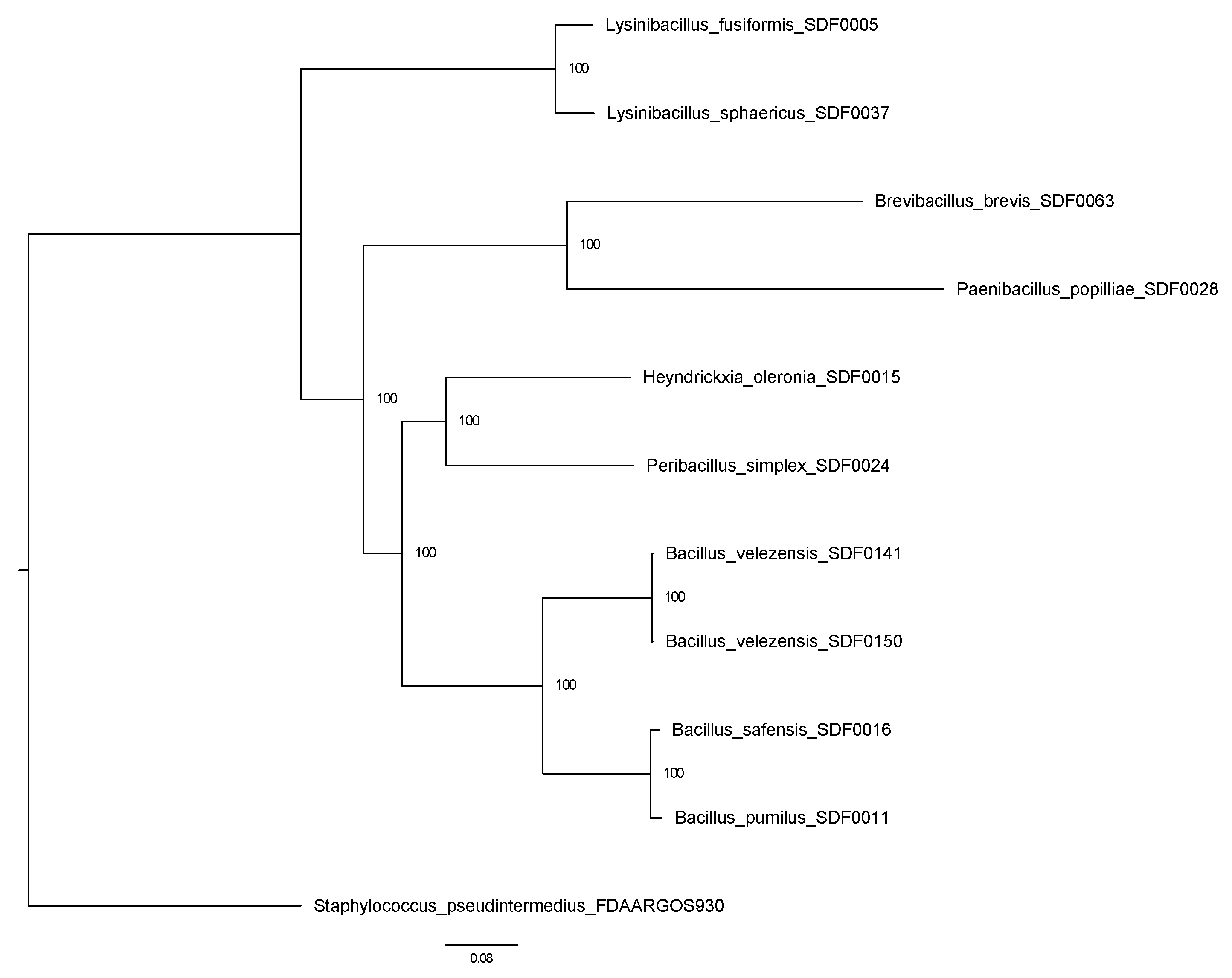

Whole Genome-Based Features and Phylogeny

BGC Predictions

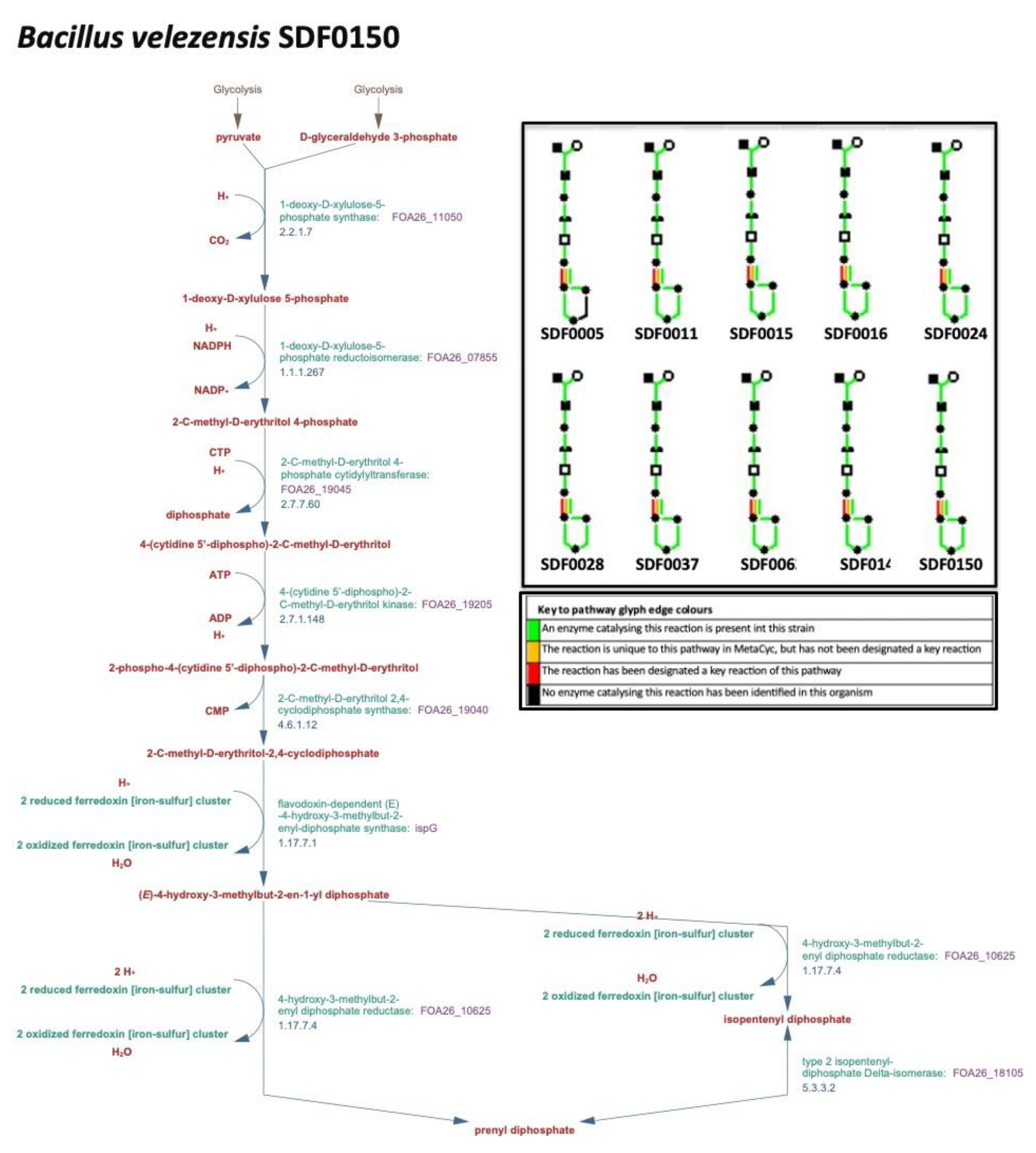

MEP Pathway Reconstruction

Detection of Polyprenyl Synthase Enzymes

Similarity of the Enzyme Set for Terpene Production

Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction Based on Terpene Synthase Contents

3. Results

3.1. SDF Strain Genome Features

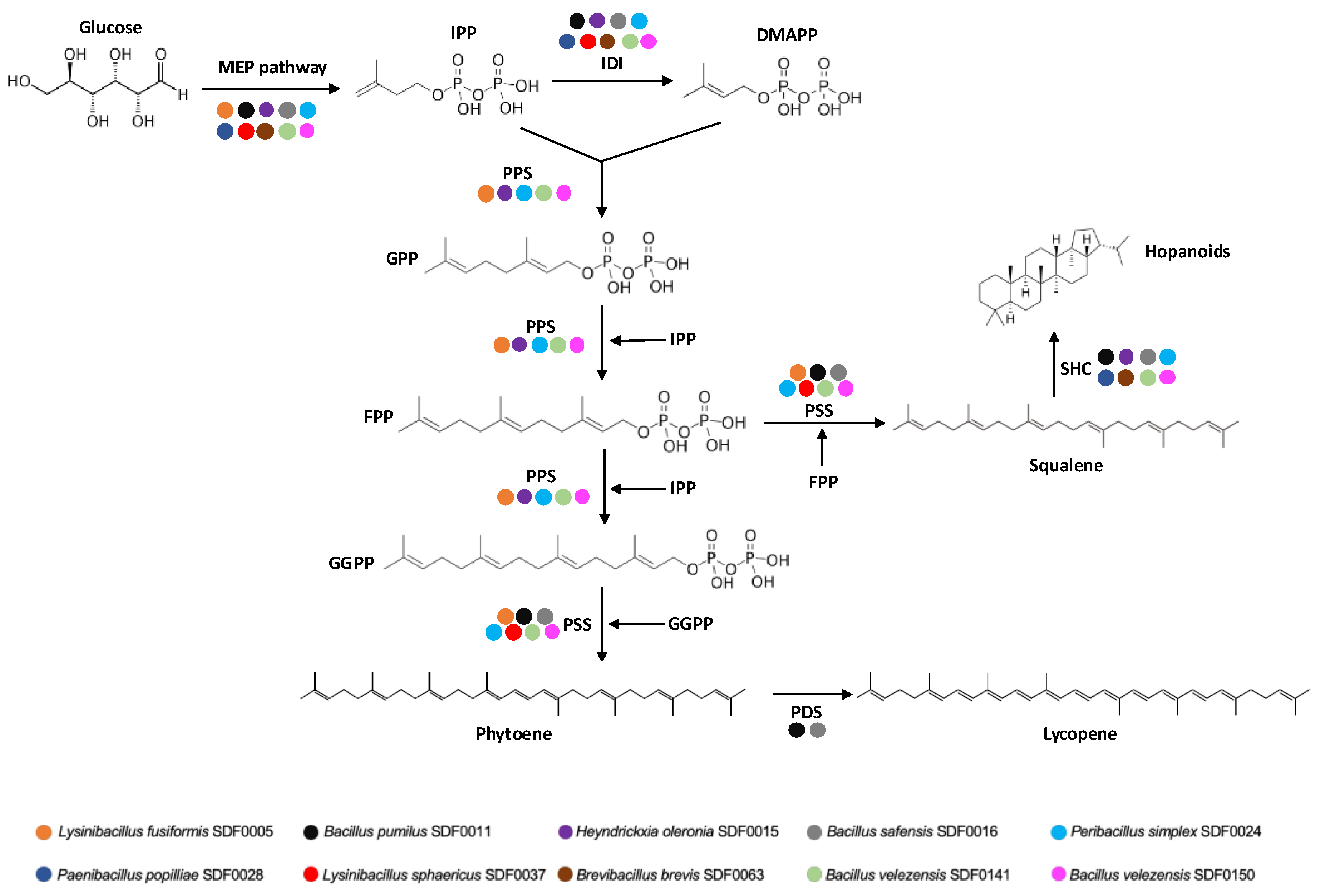

3.2. MEP Pathway Reconstruction

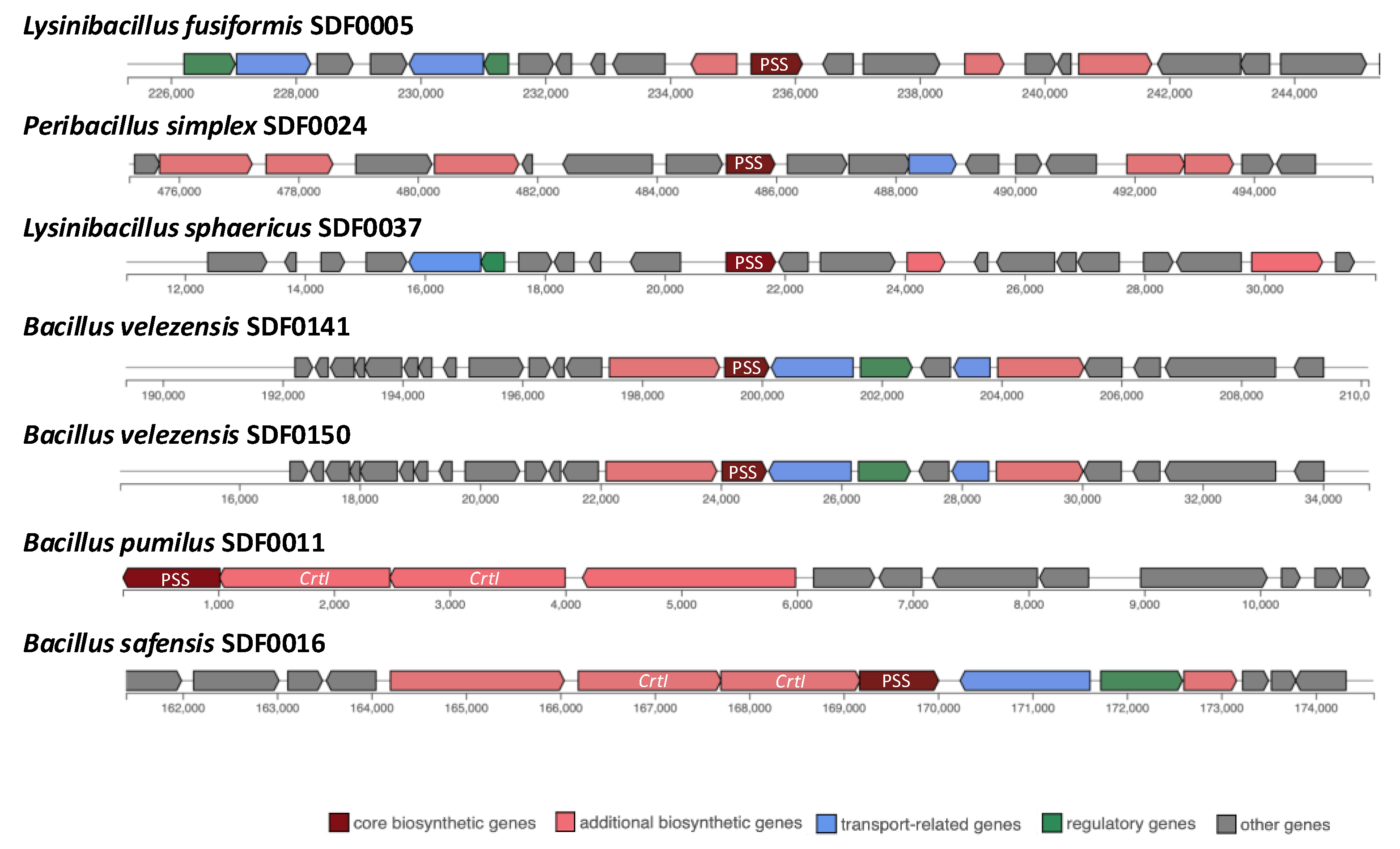

3.3. Detection of Polyprenyl Synthase Enzymes

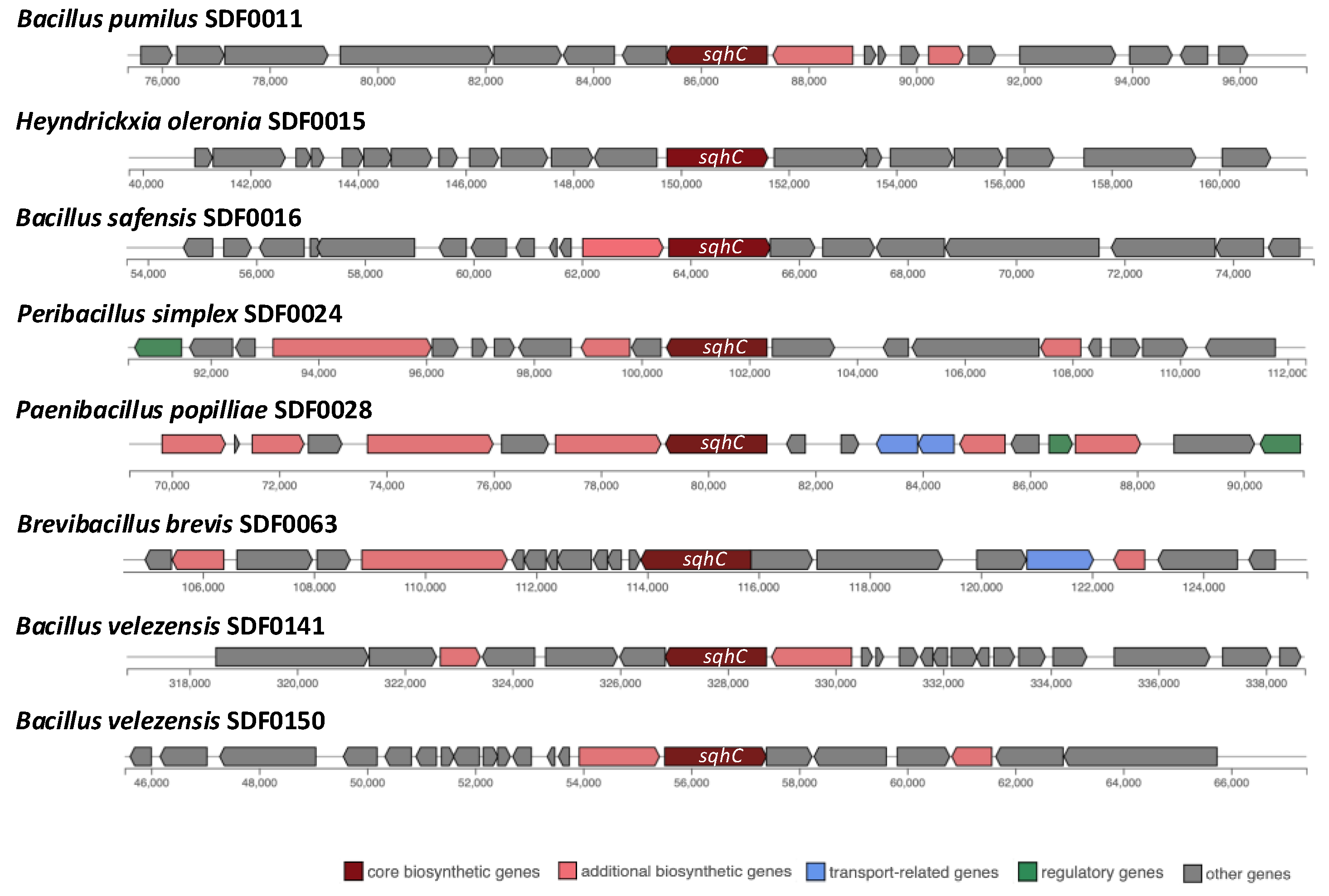

3.4. Prediction of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters Associated with Terpenes Synthesis

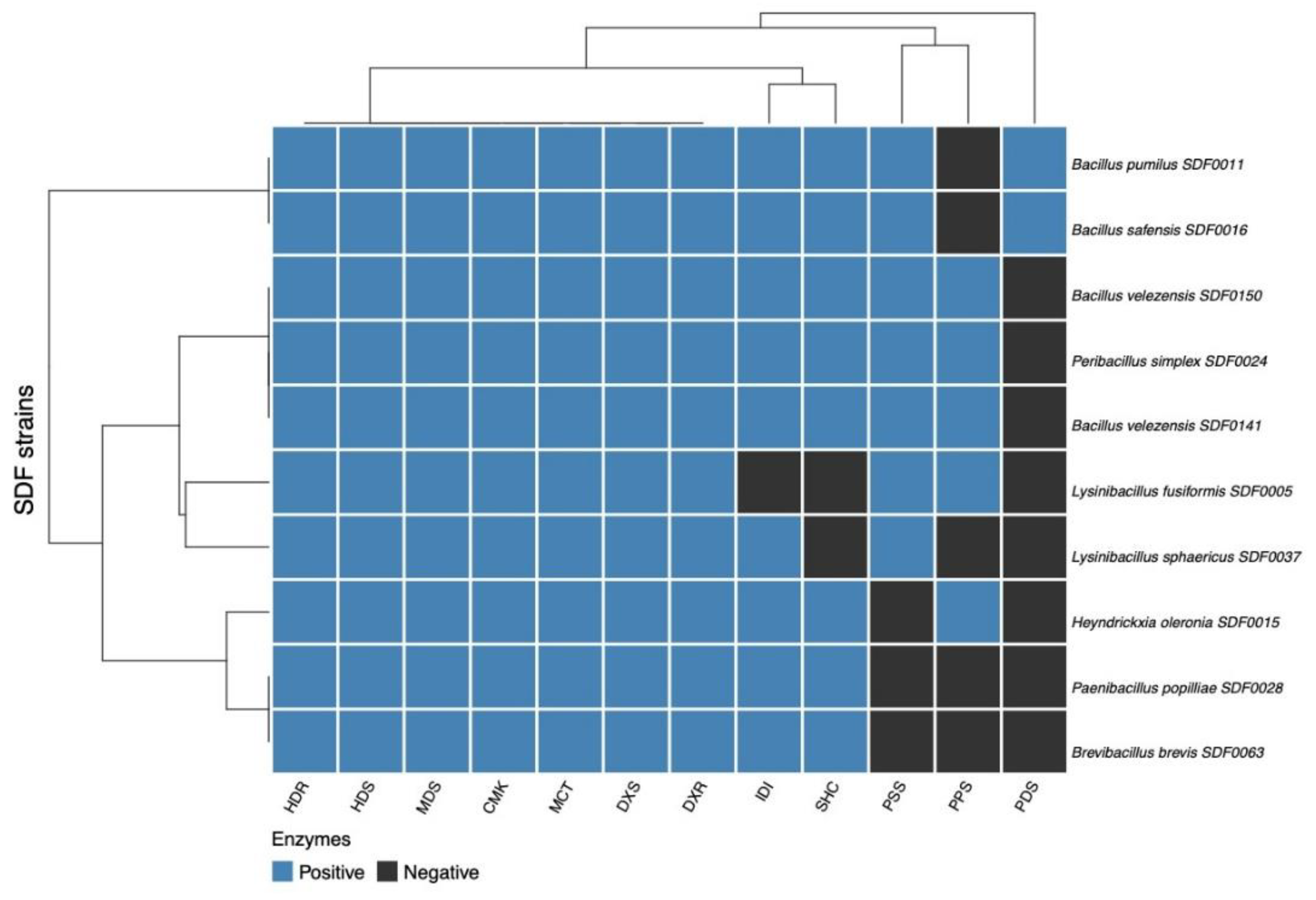

3.5. Distribution of the Enzyme Set for Terpene Production Among the 10 SDF Strains

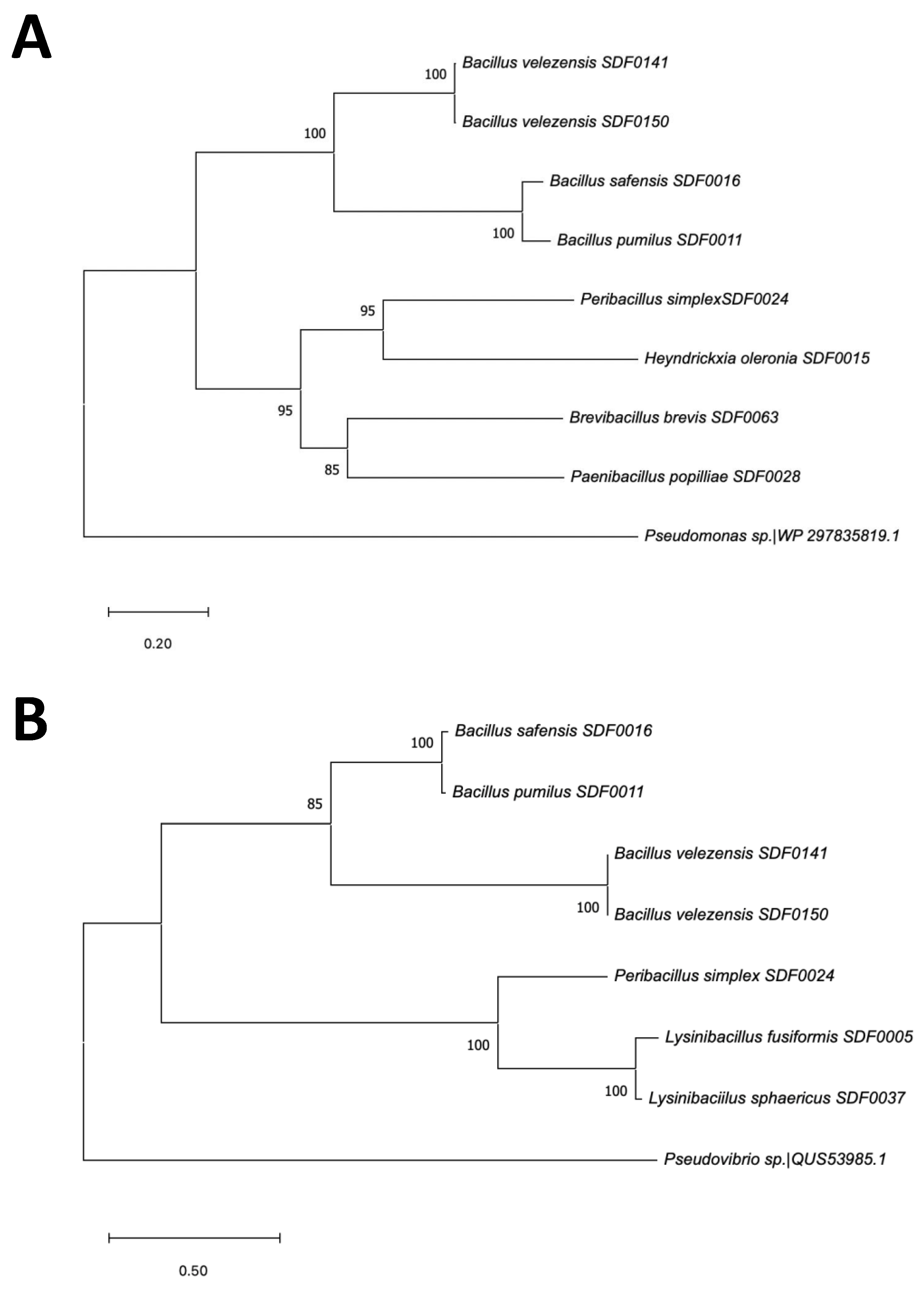

3.6. SDF Strains Evolutionary Relationship Based on Two TS Amino Acid Sequences

4. Discussion

4.1. Uncovering Enzymes from the MEP Pathway and the Polyprenyl Synthase Family in the SDF Strains

4.2. Genomic Potential of Selected SDF Strains for Terpene Production

4.3. The Evolutionary Nature of Terpene Production in the SDF Stains

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, B.P.; Rateb, M.E.; Rodriguez-Couto, S.; Polizeli, M.D.L.T.D.M.; Li, W.-J. Microbial Secondary Metabolites: Recent Developments and Technological Challenges. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bills, G.F.; Gloer, J.B. Biologically Active Secondary Metabolites from the Fungi. Microbiology Spectrum 2016, 4, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, S.; Al-Taweel, A. Terpenes and Terpenoids; IntechOpen: London, United Kingdom, 2018; pp. 01–152. ISBN 978-1-83881-529-5.

- Rudolf, J.D.; Aslup, T.; Xu, B.; Li, Z. Bacterial Terpenome. Natural Product Reports 2021, 38, 905–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quin, M.B.; Flynn, C.M.; Schimidt-Dannert, C. Traversing the Fungal Terpenome. Natural Product Reports 2014, 31, 1449–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, M.E.F.; Mohamed, T.A.; Alhammady, M.A.; Shaheen, A.M.; Reda, E.H.; Elshamy, A.I.; Aziz, M.; Paré, P.W. Molecular Architecture and Biomedical Leads of Terpenes from Red Sea Marine Invertebrates. Marine Drugs 2015, 13, 3154–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Kuzuyama, T.; Komatsu, M.; Ikeda, H. Terpene Synthases are Widely Distributed in Bacteria. PNAS 2015, 112, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morandini, L.; Caulier, S.; Bragard, C.; Mahillon, J. Bacillus cereus sensu lato Antimicrobial Arsenal: An Overview. Microbiological Research 2024, 283, 127697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Zevallos, D.M.; Hellén, H.; Hakola, H.; Nouhuys, S.V.; Halopainen, J.K. Induced defenses of Veronica spicata: Variability in herbivore-induced volatile organic compounds. Phytochemistry Letters 2013, 6, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Ding, N.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Han, L.; Huang, X. Albaflavenoid, a New Tricyclic Sesquiterpenoid from Streptomyces violascens. The Journal of Antibiotics 2016, 69, 773–775. [Google Scholar]

- Netzker, T.; Shepherdson, E.M.F.; Zambri, M.P.; Elliot, M.A. Bacterial Volatile Compounds: Functions in Communication, Cooperation, and Competition. Annual review of microbiology 2020, 74, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyc, O.; Song, C.; Dickschat, J.S.; Vos, M.; Garbeva, P. The Ecological Role of Volatile and Soluble Secondary Setabolites Produced by Soil Bacteria. Trends in microbiology 2017, 25, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twaij, B.M.; Hasan, M.N. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from Plant Sources: Types, Synthesis, and Their Therapeutic Uses. International Journal of Plant Biology 2022, 13, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhi, H.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, P. Genetic engineering of yeast, filamentous fungi and bacteria for terpene production and applications in food industry. Food research international 2021, 147, 110487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driks, A.; Eichenberger, P. The Bacterial Spore: From Molecules to Systems; ASM Press: Washington, DC, United States of America, 2016; pp. 01–397. ISBN 9781555816759.

- Christie, G.; Setlow, P. Bacillus spore germination: Knowns, unknowns and what we need to learn. Cellular signaling 2020, 74, 109729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A.; Garrity, G.M. Valid publication of the names of forty-two phyla of prokaryotes. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 2021, 71, 005056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, M.Y.; Yutin, N.; Wolf, Y.I.; Alvarez, R.V.; Koonin, E.V. Conservation and Evolution of the Sporulation Gene Set in Diverse Members of the Firmicutes. Journal of Bacteriology 2022, 204, e00079-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritze, D. Taxonomy of the Genus Bacillus and Related Genera: The Aerobic Endospore-Forming Bacteria. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 1245–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandic-Mulec, I.; Prosser, J.I. Diversity of Endospore-forming Bacteria in Soil: Characterization and Driving Mechanisms. In Endospore-forming Soil Bacteria, 1st ed.; Logan, N.A., Vos, P., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2011; Volume 27, pp. 31–59. ISBN 978-3-642-19577-8. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, N.A. Bacillus and relatives in foodborne illness. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2012, 112, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harirchi, S.; Sar, T.; Ramezani, M.; Aliyu, H.; Etemadifar, Z.; Nojoumi, S.A.; Yazdian, F.; Awasthi, M.K.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Bacillales: From Taxonomy to Biotechnological and Industrial Perspectives. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, C.D.; Yang, B.W.; Yeo, I.-C.; Hahm, Y.T. Antimicrobial peptides of the genus Bacillus: a new era for antibiotics. Canadian journal of microbiology 2015, 61, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronner, S.; Krismer, B.; Brötz-Oesterhelt, H.; Peschel, A. The microbiome-shaping roles of bacteriocins. Natures Reviews Microbiology 2021, 19, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, B.; Ortiz, A.; Keswani, C.; Minkina, T.; Mandzhieva, S.; Singh, S.P.; Rekadwad, B.; Borriss, R.; Jain, A.; Singh, H.B.; et al. Bacillus spp. as Bio-factories for Antifungal Secondary Metabolites: Innovation Beyond Whole Organism Formulations. Microbial ecology 2023, 86, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondol, M.A.M.; Shin, H.J.; Islam, M.T. Diversity of Secondary Metabolites from Marine Bacillus Species: Chemistry and Biological Activity. Marine Drugs 2013, 11, 2846–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falqueto, S.A.; Pitaluga, B.F.; Sousa, J.R.; Targanski, S.K.; Campos, M.G.; Mendes, T.A.O.; Silva, G.F.; Silva, D.H.S.; Soares, M.A. Bacillus spp. metabolites are effective in eradicating Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae with low toxicity to non-target species. Journal of invertebrate pathology 2021, 179, 107525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orem, J.C.; Silva, W.M.C.; Raiol, T.; Magalhães, M.I.; Martins, P.H.; Cavalcante, D.A.; Kruger, R.H.; Brigido, M.M.; De-Souza, M.T. Phylogenetic diversity of aerobic spore-forming Bacillales isolated from Brazilian soils. International Microbiology 2019, 22, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, D.A.; De-Souza, M.T.; Orem, J.C.; Magalhães, M.I.A.; Martins, P.H.; Boone, T.J.; Castillo, J.A.; Driks, A. Ultrastructural analysis of spores from diverse Bacillales species isolated from Brazilian soil. Environmental Microbiology Reports 2019, 11, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.H.R.; Silva, L.P.; Orem, J.C.; Magalhães, M.I.A.; Cavalcante, D.A.; De-Souza, M.T. Protein profiling as a tool for identifying environmental aerobic endospore-forming bacteria. Open Journal of Bacteriology 2020, 4, 001–007. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, P.H.R.; Rabinovitch, L.; Orem, J.C.; Silva, W.M.C.; Mesquita, F.A.; Magalhães, M.I.A.; Cavalcante, D.A.; Vivoni, A.M.; Oliveira, E.J.; Lima, V.C.P.; et al. Biochemical, physiological, and molecular characterisation of a large collection of aerobic endospore-forming bacteria isolated from Brazilian soils. Neotropical Biology and Conservation 2023, 18, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, F.A.; Silva, W.M.C.; De-Souza, M.T. In silico Analysis of the Genomic Potential for the Production of Specialized Metabolites of Ten Strains of the Bacillales Order Isolated from the Soil of the Federal District, Brazil. In Advances in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, 1st ed.; Scherer, N.M., Melo-Minardi, R.C., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Brazil, 2022, Volume 13523; pp. 158–163. ISBN 978-3-031-21175-1. [Google Scholar]

- Coil, D.; Jospin, G.; Darling, A.M. A5-miseq: an updated pipeline to assemble microbial genomes from Illumina Miseq data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatusova, T.; DiCuccio, M.; Badretdin, A.; Chetvernin, V.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Zaslavsky, L.; Lomsadze, A.; Pruitt, K.D.; Borodovsky, M.; Ostell, J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acid Research 2016, 44, 6614–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setubal, J.C.; Almeida, N.F.; Wattam, A.R. Comparative Genomics for Prokaryotes. Methods in Molecular Biology 2018, 1704, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Stoeckert Jr, J.; Roos, D.S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Research 2003, 13, 2178–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castresana, J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2000, 17, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Kloosterman, A.M.; Charlop-Powers, Z.; vanWezel, G.P.; Medema, M.H.; Weber, T. antiSMASH 6.0: improving cluster detection and comparison capabilities. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, W29–W35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanove, A.J.; Koebnik, R.; Lu, H.; Furutani, A.; Angiuoli, S.V.; Patil, P.B.; Sluys, M.A.V.; Ryan, R.P.; Meyer, D.F.; Han, S.-W.; et al. Two New Complete Genome Sequences Offer Insight into Host and Tissue Specificity of Plant Pathogenic Xanthomonas spp. Journal of Bacteriology 2011, 193, 5450–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, M.; Edelmann, D.; Kopp-Schneider, A. Clustering of samples and variables with mixed-type data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medema, M.H.; Kottmann, R.; Yilmaz, P. Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster. Nature Chemical Biology 2015, 11, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köcher, S.; Breitenbach, J.; Müller, V.; Sandmann, G. Structure, function and biosynthesis of carotenoids in the moderately halophilic bacterium Halobacillus halophilus. Archives of Microbiology 2009, 191, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Kóvacs, A.T. How to identify and quantify the members of the Bacillus genus? Environmental Microbiology 2024, 26, e16593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.S.; Patel, S. Robust Demarcation of the Family Caryophanaceae (Planococcaceae) and Its Different Genera Including Three Novel Genera Based on Phylogenomics and Highly Specific Molecular Signatures. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 10, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvochina, M.; Mussig, A.J.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Skarkshewski, A.; Rinke, C.; Parks, D.H.; Hugenholtz, P. Proposal of names for 329 higher taxa defined in the Genome Taxonomy Database under two prokaryotic codes. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2023, 370, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.S.; Patel, S.; Saini, N.; Chen, S. Robust demarcation of 17 distinct Bacillus species clades, proposed as novel Bacillaceae genera, by phylogenomics and comparative genomic analyses: description of Robertmurraya kyonggiensis sp. nov. and proposal for an emended genus Bacillus limiting it only to the members of the Subtilis and Cereus clades of species. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2020, 70, 5753–5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Gupta, R.S. A phylogenomic and comparative genomic framework for resolving the polyphyly of the genus Bacillus: Proposal for six new genera of Bacillus species, Peribacillus gen. nov., Cytobacillus gen. nov., Mesobacillus gen. nov., Neobacillus gen. nov., Metabacillus gen. nov. and Alkalihalobacillus gen. nov. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2020, 70, 406–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, T.; Inoue, T.; Oka, A.; Nishino, T.; Osumi, T.; Hata, S. Cloning, expression, and characterization of cDNAs encoding Arabidopsis thaliana squalene synthase. PNAS 1995, 98, 2328–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, T.R.; Shechter, I. Squalene synthase: Structure and regulation. Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology 2000, 65, 157–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Quesada, C.; López-Biedma, A.; Toledo, E.; Gaforio, J.J. Squalene Stimulates a Key Innate Cell to Foster Wound Healing and Tissue Repair. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2018, 2018, 9473094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Guan, Z.; Merkerk, R.V.; Pramastya, H.; Abdallah, I.I.; Setroikromo, R.; Quax, W.J. Production of Squalene in Bacillus subtilis by Squalene Synthase Screening and Metabolic Engineering. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2020, 68, 4447–4455. [Google Scholar]

- Siedenburg, G.; Jendrossek, D. Squalene-Hopene Cyclases. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2011, 77, 3905–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, S.; Begum, F.; Rabaan, A.A.; Aljeldah, M.; Al Shammari, B.R.; Alawfi, A.; Alshengeti, A.; Sulaiman, T.; Khan, A. Classification and Multifaceted Potential of Secondary Metabolites Produced by Bacillus subtilis Group: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belin, B.J.; Busset, N.; Giraud, E.; Molinaro, A.; Silipo, A.; Newman, D.K. Hopanoid lipids: from membranes to plant-bacteria interactions. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018, 16, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabio, E.; Lozano, M.; Espinosa, V.M.; Mendes, R.L.; Pereira, A.P.; Palavra, A.F.; Coelho, J.A. Lycopene and β-Carotene Extraction from Tomato Processing Waste Using Supercritical CO2. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research 2003, 42, 6641–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, H.; Mao, X. Biotechnological production pf lycopene by microorganisms. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2020, 104, 10307–10324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, D.; Ye, C.; Min, Y.; Li, L. Production of a novel lycopene-rich soybean food by fermentation with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Food Science and Technology 2022, 153, 112551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Bao, Y.; Zhu, P. Development of a novel functional yogurt rich in lycopene by Bacillus subtilis. Food Chemistry 2023, 407, 135142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, A.; Iki, K.; Sandmann, G.; Shindo, K. Isolation and identification of 4,4’-diapolycopene-4,4’-dioc acid produced by Bacillus firmus GB1 and its singlet oxygen quenching activity. Journal of Oleo Science 2013, 62, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, W. Botanische Beschreinbung häufiger am Buttersäureabbau beteiligter sporenbildender Bakteriensspezies. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie, Parasitenkunde, Infektionskrankheiten und Hygiene. Abteilung II 1933, 87, 446–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.Y.; Cho, E.-S.; Yoon, D.J.; Cha, I.-T.; Jung, D.-H.; Nam, Y.-D.; Park, S.-L.; Lim, S.-I.; Seo, M.-J. Genomic and Physiological Characterization of Metabacillus flavus sp. nov., a Novel Carotenoid-Producing Bacilli Isolated from Korean Marine Mud. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattekkatte, A.; Garms, S.; Brandt, W.; Boland, W. Enhanced structural diversity in terpenoid biosynthesis: enzymes, substrates and cofactors. Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry 2018, 16, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, R.; Meirinhos-Soares, L.; Carriço, J.A.; Pintado, M.; Peixe, L.V. Phylogenetic and clonality analysis of Bacillus pumilus isolates uncovered a highly heterogeneous population of different closely related species and clones. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2014, 90, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substrate | Enzyme code* | Enzyme name (abbreviation) | Product (abbreviation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyruvate and G3P | 2.2.1.7 | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP) |

| DXP and NADPH | 1.1.1.267 | DXP reductorisomerase (DXR) | methylerythritol-phosphate (MEP) |

| MEP | 2.7.7.60 | MEP cytidylyltransferase (MCT) | 4-(cytidine 5′-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol (CD-ME) |

| CD-ME and ATP | 2.7.1.148 | CD-ME kinase (CMK) | 4-difosfocitidil-2-C-metil-Deritritol 2-fosfato (CD-MEP) |

| CD-MEP | 4.6.1.12 | 2C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (MDS) | 2C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate (MEC) |

| MEC and NADPH | 1.17.7.3 | 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate synthase (HDS) | 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate (HMBPP) |

| HMBPP and NADPH | 1.17.7.4 | HMBPP reductase (HDR) | isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) |

| IPP | 5.3.3.2 | isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase (IDI) | dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) |

| IPP and DMAPP | 2.5.1.1 | GPP synthase (GPPS)** | geranyl diphosphate (GPP) |

| GPP and IPP | 2.5.1.10 | FPP synthase (FPPS)** | farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) |

| FPP and IPP | 2.5.1.29 | GGPP synthase (GGPPS)** | geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) |

| Strain | Size (bp) | Scaffold # | N50 (bp) | GC content (%) | CDS # | Protein coding regions | Pseudo genes (total) | rRNA genes (5S; 16S; 23S) |

tRNA genes | GenBank accession # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysinibacillus fusiformis SDF0005 | 4,472,771 | 24 | 392,231 | 37.6 | 4,369 | 4,328 | 41 | 13; 7; 7 | 85 | VKHW00000000.1 |

| Bacillus pumilus SDF0011 | 3,686,817 | 56 | 143,274 | 41.2 | 3,688 | 3,617 | 71 | 7; 3; 2 | 73 | VKHY00000000.1 |

| Heyndrickxia oleronia SDF0015 | 5,267,437 | 75 | 151,790 | 34.7 | 5,127 | 5,018 | 109 | 10; 14; 7 | 129 | VKHZ00000000.1 |

| Bacillus safensis SDF0016 | 3,674,191 | 25 | 484,434 | 41.6 | 3,688 | 3,640 | 48 | 4; 1; 1 | 74 | SADW00000000.1 |

| Peribacillus simplex SDF0024 | 5,376,271 | 45 | 497,961 | 40.2 | 5,204 | 5,007 | 197 | 14; 7; 6 | 81 | VKHX00000000.1 |

| Paenibacillus popilliae SDF0028 | 6,580,875 | 39 | 611,008 | 46.5 | 5,684 | 5,519 | 165 | 2; 2; 3 | 62 | SADY00000000.1 |

| Lysinibacillus sphaericus SDF0037 | 5,122,785 | 71 | 215,682 | 36.5 | 4,869 | 4,643 | 226 | 5; 7; 2 | 71 | SADV00000000.1 |

| Brevibacillus brevis SDF0063 | 6,239,737 | 31 | 471,412 | 47.3 | 5,789 | 5,602 | 187 | 1; 16; 9 | 89 | SADX00000000.1 |

| Bacillus velezensis SDF0141 | 3,945,527 | 15 | 962,078 | 46.4 | 3,887 | 3,780 | 107 | 8; 3; 2 | 78 | VKIB00000000.1 |

| Bacillus velezensis SDF0150 | 3,927,067 | 21 | 271,062 | 46.4 | 3,870 | 3,763 | 107 | 8; 6; 2 | 82 | VKIC00000000.1 |

| Strain | Occurrence | identity (%)* | Reference species | GeneBank reference sequence# |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysinibacillus fusiformis SDF0005 | + | 99.66 | Lysinibacillus fusiformis | KAB0443654.1 |

| Bacillus pumilus SDF0011 | - | NA | NA | NA |

| Heyndrickxia oleronia SDF0015 | + | 67.86 | Bacillus pumilus | WP_268443628.1 |

| Bacillus safensis SDF0016 | - | NA | NA | NA |

| Peribacillus simplex SDF0024 | + | 98.65 | Peribacillus sp. | WP_241589686.1 |

| Paenibacillus popilliae SDF0028 | - | NA | NA | NA |

| Lysinibacillus sphaericus SDF0037 | - | NA | NA | NA |

| Brevibacillus brevis SDF0063 | - | NA | NA | NA |

| Bacillus velezensis SDF0141 | + | 100 | Bacillus velezensis | ASK59031.1 |

| Bacillus velezensis SDF0150 | + | 99.65 | Bacillus velezensis | QWC45887.1 |

| Strain | Gene/TS enzyme | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| sqhC/SHC | Phytoene and/or squalene synthase family gene/PSS | crti/PDS | |

| Lysinibacillus fusiformis SDF0005 | - | + | - |

| Bacillus pumilus SDF0011 | + | + | + |

| Heyndrickxia oleronia SDF0015 | + | - | - |

| Bacillus safensis SDF0016 | + | + | + |

| Peribacillus simplex SDF0024 | + | + | - |

| Paenibacillus popilliae SDF0028 | + | - | - |

| Lysinibacillus sphaericus SDF0037 | - | + | - |

| Brevibacillus brevis SDF0063 | + | - | - |

| Bacillus velezensis SDF0141 | + | + | - |

| Bacillus velezensis SDF0150 | + | + | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).