Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a significant burden on global public health, being one of the main causes of cancer mortality worldwide. This type of cancer has been closely linked to viral and environmental factors, particularly hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and exposure to aflatoxins, produced by fungi of the genus Aspergillus. Aflatoxins are known carcinogens found in contaminated foods, such as grains and nuts. In the presence of chronic HBV infection, they can function as cofactors in liver carcinogenesis. The synergistic interaction between HBV and aflatoxins is crucial for understanding the molecular complexity of HCC. Multiple studies have shown how the simultaneous presence of these carcinogens significantly increases the risk of developing HCC. The complexity of these mechanisms highlights the urgent need for targeted preventive and therapeutic strategies, ranging from improvements in food safety and aflatoxin regulation to widespread HBV vaccination in high-prevalence areas. Understanding the molecular interactions between these environmental and viral factors is crucial not only for the diagnosis and treatment of HCC, but also for the effective implementation of public health policies that re-duce the global burden of this devastating liver disease. A multifactorial approach is essential to effectively address the increasing prevalence of HCC worldwide and improve health outcomes for affected populations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

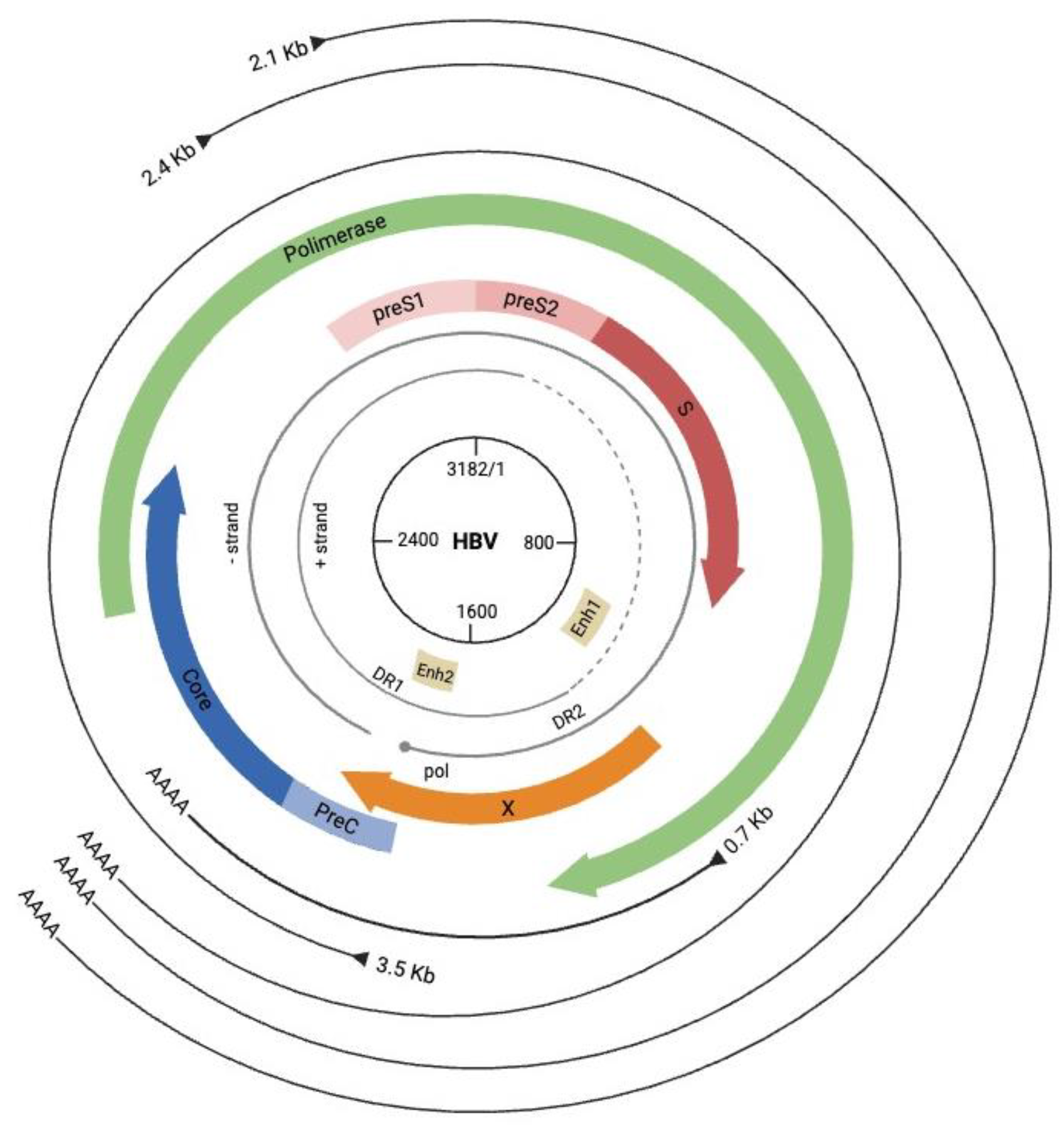

2. Hepatitis B Virus: Structure and Replication

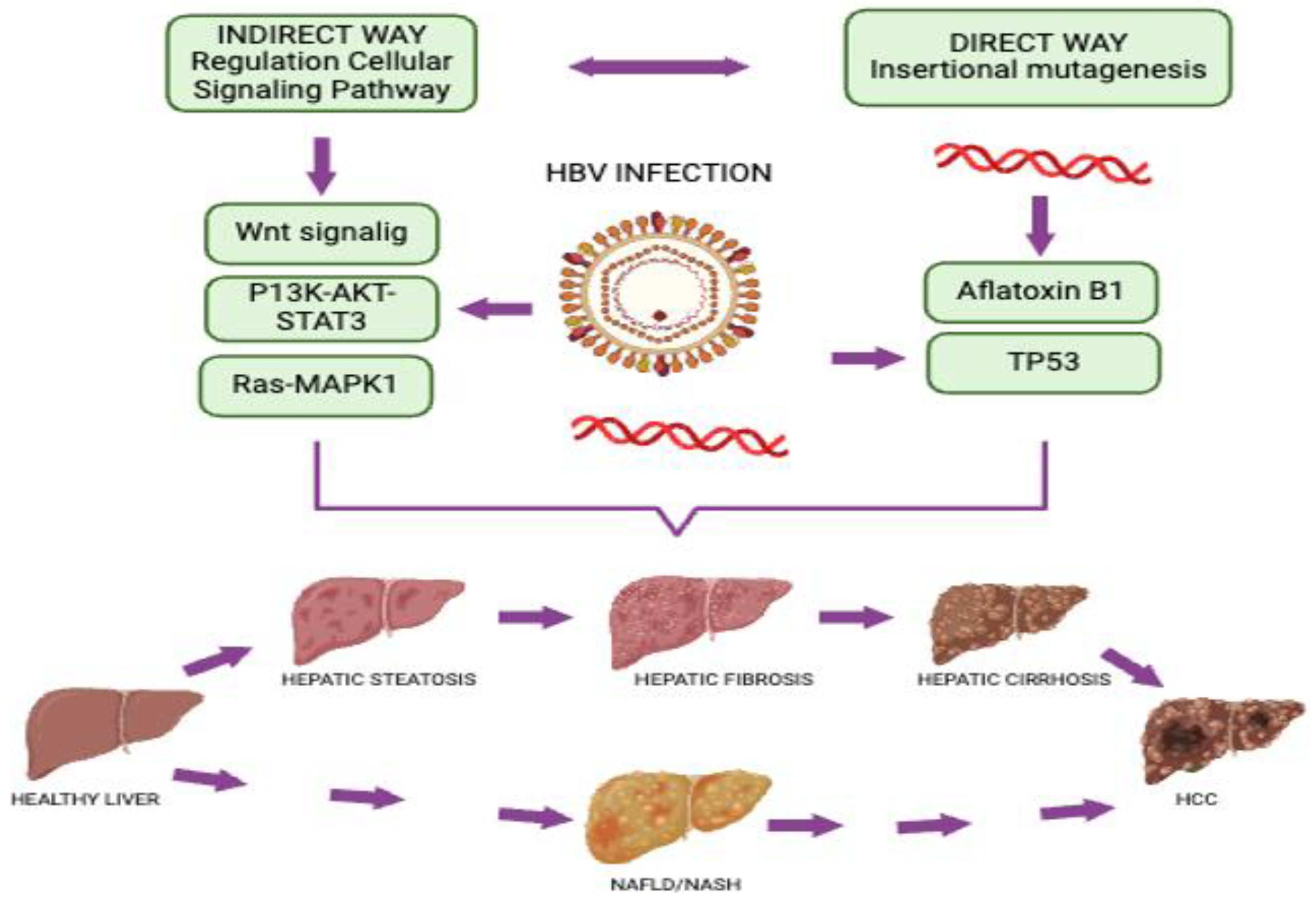

3. Mechanisms of HBV-Mediated Cancer Development

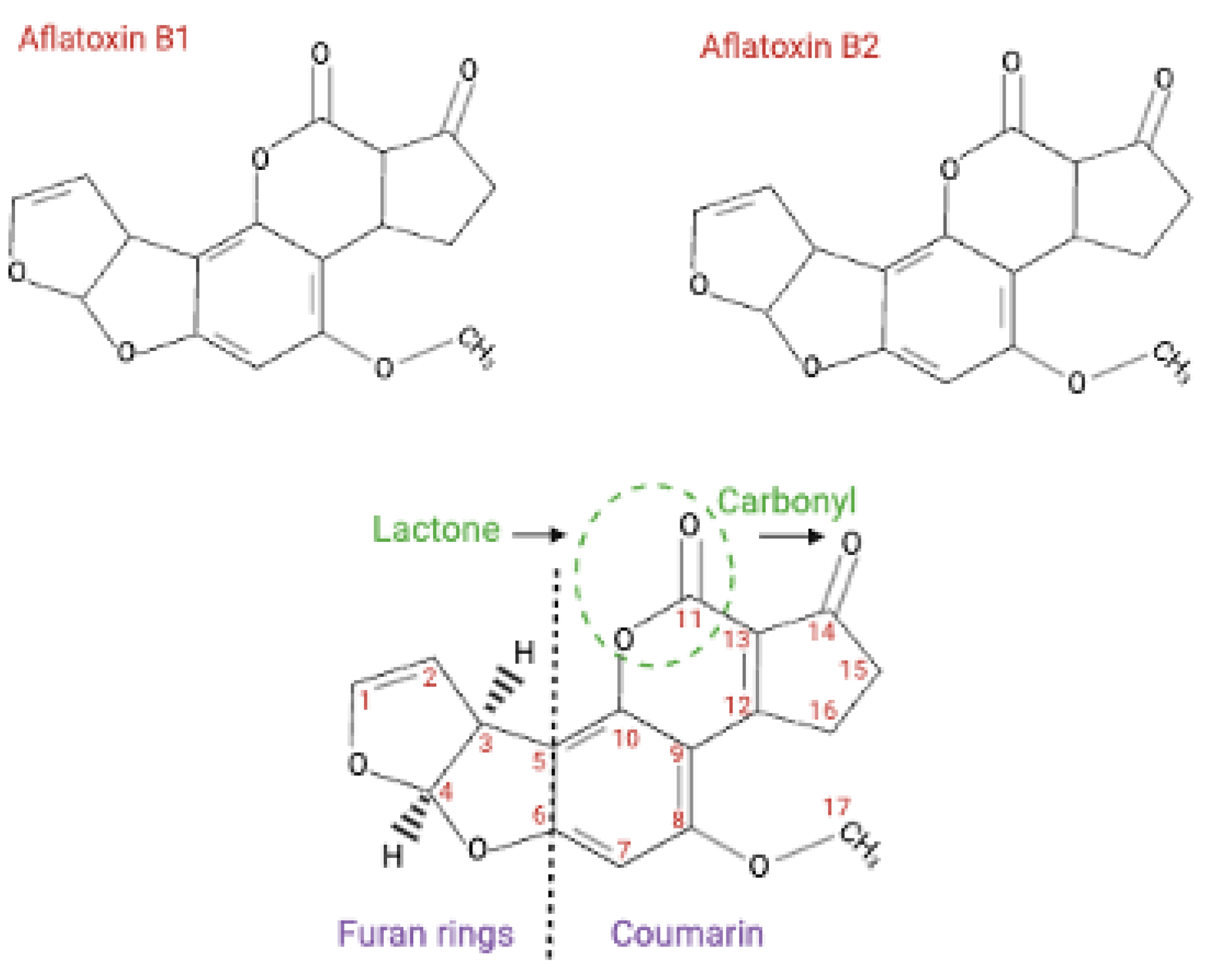

4. Aflatoxins and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

5. Epidemiological Associations Between HBV and AFB1 for HCC Development

6. Mechanisms of Cooperation Between HBV and Aflatoxins for HCC Development

6.1. Aflatoxin B1 Cooperates with HBV HBx Oncoprotein for Carcinogenesis

6.2. AFB1 Exposure Might Favor HBV Integration Events

6.3. HBV Infection Sensitizes Hepatic Cells to AFB1 Effects

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collaborators, G.C.o.D. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2100–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, M.R.; Campbell, P.J.; Futreal, P.A. The cancer genome. Nature 2009, 458, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudu, S.A.; Shinkafi, S.H.; Jimoh, A.O. A critical review of diagnostic and prognostic markers of chronic hepatitis B infection. Med Rev (2021) 2024, 4, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, J.P.; Carrillo-Beltrán, D.; Aedo-Aguilera, V.; Calaf, G.M.; León, O.; Maldonado, E.; Tapia, J.C.; Boccardo, E.; Ozbun, M.A.; Aguayo, F. Tobacco Exposure Enhances Human Papillomavirus 16 Oncogene Expression via EGFR/PI3K/Akt/c-Jun Signaling Pathway in Cervical Cancer Cells. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, F.; Boccardo, E.; Corvalán, A.; Calaf, G.M.; Blanco, R. Interplay between Epstein-Barr virus infection and environmental xenobiotic exposure in cancer. Infect Agent Cancer 2021, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, F.; Muñoz, J.P.; Perez-Dominguez, F.; Carrillo-Beltrán, D.; Oliva, C.; Calaf, G.M.; Blanco, R.; Nuñez-Acurio, D. High-Risk Human Papillomavirus and Tobacco Smoke Interactions in Epithelial Carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Santella, R. The role of aflatoxins in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepat Mon 2012, 12, e7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.J. Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. Hepatology 2009, 49, S13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukuda, S.; Watashi, K. Hepatitis B virus biology and life cycle. Antiviral Res 2020, 182, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatakrishnan, B.; Zlotnick, A. The Structural Biology of Hepatitis B Virus: Form and Function. Annu Rev Virol 2016, 3, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, C.; Mason, W.S. Molecular biology of hepatitis B virus infection. Virology 2015, 479-480, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Liu, K. Complete and Incomplete Hepatitis B Virus Particles: Formation, Function, and Application. Viruses 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, D.S.; Cameron, C.H.; Briggs, M. Virus-like particles in serum of patients with Australia-antigen-associated hepatitis. Lancet 1970, 1, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leistner, C.M.; Gruen-Bernhard, S.; Glebe, D. Role of glycosaminoglycans for binding and infection of hepatitis B virus. Cell Microbiol 2008, 10, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, A.; Gripon, P.; Urban, S. Hepatitis B virus infection initiates with a large surface protein-dependent binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Hepatology 2007, 46, 1759–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrier, E.R.; Colpitts, C.C.; Bach, C.; Heydmann, L.; Weiss, A.; Renaud, M.; Durand, S.C.; Habersetzer, F.; Durantel, D.; Abou-Jaoudé, G.; et al. A targeted functional RNA interference screen uncovers glypican 5 as an entry factor for hepatitis B and D viruses. Hepatology 2016, 63, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glebe, D.; Urban, S.; Knoop, E.V.; Cag, N.; Krass, P.; Grün, S.; Bulavaite, A.; Sasnauskas, K.; Gerlich, W.H. Mapping of the hepatitis B virus attachment site by use of infection-inhibiting preS1 lipopeptides and tupaia hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 2005, 129, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gripon, P.; Cannie, I.; Urban, S. Efficient inhibition of hepatitis B virus infection by acylated peptides derived from the large viral surface protein. J Virol 2005, 79, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Lempp, F.A.; Mehrle, S.; Nkongolo, S.; Kaufman, C.; Fälth, M.; Stindt, J.; Königer, C.; Nassal, M.; Kubitz, R.; et al. Hepatitis B and D viruses exploit sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide for species-specific entry into hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1070–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhong, G.; Xu, G.; He, W.; Jing, Z.; Gao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Peng, B.; Wang, H.; et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, M.; Saso, W.; Sugiyama, R.; Ishii, K.; Ohki, M.; Nagamori, S.; Suzuki, R.; Aizaki, H.; Ryo, A.; Yun, J.H.; et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor is a host-entry cofactor triggering hepatitis B virus internalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 8487–8492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, B.; Glebe, D.; Kann, M. Lipid-mediated introduction of hepatitis B virus capsids into nonsusceptible cells allows highly efficient replication and facilitates the study of early infection events. J Virol 2006, 80, 5465–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kann, M.; Sodeik, B.; Vlachou, A.; Gerlich, W.H.; Helenius, A. Phosphorylation-dependent binding of hepatitis B virus core particles to the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 1999, 145, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, B.; Vlachou, A.; Panté, N.; Helenius, A.; Kann, M. Nuclear import of hepatitis B virus capsids and release of the viral genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 9849–9854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, W.H.; Robinson, W.S. Hepatitis B virus contains protein attached to the 5' terminus of its complete DNA strand. Cell 1980, 21, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Jiang, D.; Zhou, T.; Cuconati, A.; Block, T.M.; Guo, J.T. Characterization of the intracellular deproteinized relaxed circular DNA of hepatitis B virus: an intermediate of covalently closed circular DNA formation. J Virol 2007, 81, 12472–12484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.H.; Seeger, C. The reverse transcriptase of hepatitis B virus acts as a protein primer for viral DNA synthesis. Cell 1992, 71, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rall, L.B.; Standring, D.N.; Laub, O.; Rutter, W.J. Transcription of hepatitis B virus by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol 1983, 3, 1766–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollicino, T.; Belloni, L.; Raffa, G.; Pediconi, N.; Squadrito, G.; Raimondo, G.; Levrero, M. Hepatitis B virus replication is regulated by the acetylation status of hepatitis B virus cccDNA-bound H3 and H4 histones. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decorsière, A.; Mueller, H.; van Breugel, P.C.; Abdul, F.; Gerossier, L.; Beran, R.K.; Livingston, C.M.; Niu, C.; Fletcher, S.P.; Hantz, O.; et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein identifies the Smc5/6 complex as a host restriction factor. Nature 2016, 531, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.M.; Xu, Y.; Li, F.; Nio, K.; Reszka-Blanco, N.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Su, L. Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Promotes Degradation of SMC5/6 to Enhance HBV Replication. Cell Rep 2016, 16, 2846–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, J.; Nassal, M. Efficient Hsp90-independent in vitro activation by Hsc70 and Hsp40 of duck hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase, an assumed Hsp90 client protein. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 36128–36138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Toft, D.O.; Seeger, C. Hepadnavirus assembly and reverse transcription require a multi-component chaperone complex which is incorporated into nucleocapsids. EMBO J 1997, 16, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, C.; Döring, T.; Prange, R. Hepatitis B virus maturation is sensitive to functional inhibition of ESCRT-III, Vps4, and gamma 2-adaptin. J Virol 2007, 81, 9050–9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieler, J.T.; Prange, R. Involvement of ESCRT-II in hepatitis B virus morphogenesis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e91279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patient, R.; Hourioux, C.; Roingeard, P. Morphogenesis of hepatitis B virus and its subviral envelope particles. Cell Microbiol 2009, 11, 1561–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Q.; Qudus, M.S.; Yue, Z.; Luo, W.; Zhang, W.; Ouyang, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Innate Immunity, Inflammation, and Intervention in HBV Infection. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Cheong, J.Y. Role of Immune Cells in Patients with Hepatitis B Virus-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgia, M.; Dal Bo, M.; Toffoli, G. Role of Virus-Related Chronic Inflammation and Mechanisms of Cancer Immune-Suppression in Pathogenesis and Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.F.; Chang, M.H. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection from infancy to adult life - the mechanism of inflammation triggering and long-term impacts. J Biomed Sci 2015, 22, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T.; Budzinska, M.A.; Shackel, N.A.; Urban, S. HBV DNA Integration: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Viruses 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, S.H.; Li, C.L.; Lin, Y.Y.; Ho, M.C.; Wang, Y.C.; Tseng, S.T.; Chen, P.J. Hepatitis B Virus DNA Integration Drives Carcinogenesis and Provides a New Biomarker for HBV-related HCC. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 15, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Han, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J. The Mechanisms of HBV-Induced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2021, 8, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.; Groopman, J.D. Interaction of mutant hepatitis B X protein with p53 tumor suppressor protein affects both transcription and cell survival. Mol Carcinog 2011, 50, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; Du, Z.B.; Wang, W.H.; Wu, J.S.; Han, T.; Chen, Y.Y.; Han, P.Y.; Lei, Z.; Chen, X.X.; He, Y.; et al. Intracellular antibody targeting HBx suppresses invasion and metastasis in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocarcinogenesis via protein phosphatase 2A-B56γ-mediated dephosphorylation of protein kinase B. Cell Prolif 2022, 55, e13304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, M.C. Hepatitis B virus x protein in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011, 26 Suppl 1, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Choi, H.S.; Park, Y.K.; Park, E.S.; Shin, G.C.; Kim, D.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, K.H. HBx-induced NF-κB signaling in liver cells is potentially mediated by the ternary complex of HBx with p22-FLIP and NEMO. PLoS One 2013, 8, e57331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lin, X.; Lei, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, F.; et al. Aerobic glycolysis enhances HBx-initiated hepatocellular carcinogenesis via NF-κBp65/HK2 signalling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2022, 41, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.J.; Lin, Y.J.; Yen, C.S.; Tsai, H.W.; Tsai, T.F.; Chang, K.Y.; Huang, W.C.; Lin, P.W.; Chiang, C.W.; Chang, T.T. Hepatitis B virus X protein upregulates mTOR signaling through IKKβ to increase cell proliferation and VEGF production in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One 2012, 7, e41931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, J.; Xie, Q.; Deng, C.; Su, N.; Wei, W.; Shi, D.; Xu, F.; et al. Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Stimulates Proliferation, Wound Closure and Inhibits Apoptosis of HuH-7 Cells via CDC42. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Quan, J. Hepatitis B virus X protein increases microRNA-21 expression and accelerates the development of hepatoma via the phosphatase and tensin homolog/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep 2017, 15, 3285–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Shan, C.; Ye, L.; Zhang, X. Upregulated microRNA-29a by hepatitis B virus X protein enhances hepatoma cell migration by targeting PTEN in cell culture model. PLoS One 2011, 6, e19518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Jia, Z.; Tian, Y.; Yang, P.; Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; et al. HBx Protein Contributes to Liver Carcinogenesis by H3K4me3 Modification Through Stabilizing WD Repeat Domain 5 Protein. Hepatology 2020, 71, 1678–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, E.; Vanhove, J.; Severyn, B.; Verschueren, L.; Pauwels, F. The Hepatitis B Virus Interactome: A Comprehensive Overview. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 724877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasudhan, E.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Khan, F.I.; Lu, Z.; Meng, J.; Blake, N.; Rong, R. Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Contributes to Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Upregulation of KIAA1429 Methyltransferase and mRNA m6A Hypermethylation of HSPG2/Perlecan. Mol Carcinog 2025, 64, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.J.; Huang, T.; Wang, L.; Sun, X.F.; Zhang, Y.M. HBX suppresses PTEN to promote the malignant progression of hepatocellular carcinoma through mi-R155 activation. Ann Hepatol 2022, 27, 100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.S.; Park, Y.K.; Shin, C.Y.; Park, S.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, D.H.; Lim, K.H.; Kwon, S.Y.; Kim, K.P.; Yang, S.I.; et al. Hepatitis B virus inhibits liver regeneration via epigenetic regulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Hepatology 2013, 58, 762–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cheng, S.T.; Chen, J. HBx mediated Increase of SIRT1 Contributes to HBV-related Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumorigenesis. Int J Med Sci 2020, 17, 1783–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, P.; Cheng, B. Notch1 is a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of human hepatitis B virus X protein-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep 2014, 31, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.J.; Li, H.Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhou, W.J.; Li, J.J.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, X.Y.; Zeng, T.; Shi, Z.; et al. NAMPT promotes hepatitis B virus replication and liver cancer cell proliferation through the regulation of aerobic glycolysis. Oncol Lett 2021, 21, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Ye, Y.; Xie, L.; Li, W. Oxidative Stress and Liver Cancer: Etiology and Therapeutic Targets. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 7891574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.R.; Zheng, D.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Xie, W.H.; Huang, Y.H.; Chen, Z.X.; Wang, X.Z.; Li, D. Effect of HBx on inflammation and mitochondrial oxidative stress in mouse hepatocytes. Oncol Lett 2020, 19, 2861–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, L.; Tao, N.N.; Zhou, H.Z.; Liu, B.; Li, W.Y.; Huang, A.L.; Chen, J. Protective Role of Sirtuin3 (SIRT3) in Oxidative Stress Mediated by Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Expression. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0150961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.Y.; Li, D.; Cai, D.E.; Huang, X.Y.; Zheng, B.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Chen, Z.X.; Wang, X.Z. Hepatitis B virus X protein sensitizes HL-7702 cells to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis through modulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Oncol Rep 2017, 37, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabeer, S.; Asad, S.; Jamal, A.; Ali, A. Aflatoxin Contamination, Its Impact and Management Strategies: An Updated Review. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostry, V.; Malir, F.; Toman, J.; Grosse, Y. Mycotoxins as human carcinogens-the IARC Monographs classification. Mycotoxin Res 2017, 33, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peromingo, B.; Rodríguez, A.; Bernáldez, V.; Delgado, J.; Rodríguez, M. Effect of temperature and water activity on growth and aflatoxin production by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus on cured meat model systems. Meat Sci 2016, 122, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ospina, J.; Molina-Hernández, J.B.; Chaves-López, C.; Romanazzi, G.; Paparella, A. The Role of Fungi in the Cocoa Production Chain and the Challenge of Climate Change. J Fungi (Basel) 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangia, R.N.; Githanga, D.P.; Wang, J.S.; Anzala, O.A. Aflatoxin exposure in children age 6-12 years: a study protocol of a randomized comparative cross-sectional study in Kenya, East Africa. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2019, 5, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, C.P. Aflatoxin exposure in developing countries: the critical interface of agriculture and health. Food Nutr Bull 2007, 28, S372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwomadu, T.; Mwanza, M.; Musekiwa, A. Mycotoxin-Linked Mutations and Cancer Risk: A Global Health Issue. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F. Global burden of aflatoxin-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: a risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect 2010, 118, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhonker, S.K.; Rawat, D.; Koiri, R.K. Protective and therapeutic effects of sildenafil and tadalafil on aflatoxin B1-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cell Biochem 2021, 476, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramantieri, L.; Gnudi, F.; Vasuri, F.; Mandrioli, D.; Fornari, F.; Tovoli, F.; Suzzi, F.; Vornoli, A.; D'Errico, A.; Piscaglia, F.; et al. Aflatoxin B1 DNA-Adducts in Hepatocellular Carcinoma from a Low Exposure Area. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smela, M.E.; Hamm, M.L.; Henderson, P.T.; Harris, C.M.; Harris, T.M.; Essigmann, J.M. The aflatoxin B(1) formamidopyrimidine adduct plays a major role in causing the types of mutations observed in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 6655–6660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.A.; Germano, P.M. [Aflatoxins: current concepts on mechanisms of toxicity and their involvement in the etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma]. Rev Saude Publica 1997, 31, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lereau, M.; Gouas, D.; Villar, S.; Besaratinia, A.; Hautefeuille, A.; Berthillon, P.; Martel-Planche, G.; Nogueira da Costa, A.; Ortiz-Cuaran, S.; Hantz, O.; et al. Interactions between hepatitis B virus and aflatoxin B(1): effects on p53 induction in HepaRG cells. J Gen Virol 2012, 93, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, I.C.; Metcalf, R.A.; Sun, T.; Welsh, J.A.; Wang, N.J.; Harris, C.C. Mutational hotspot in the p53 gene in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Nature 1991, 350, 427–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.I.; Lee, S.; Das, G.C.; Park, U.S.; Park, S.M. Activation of the insulin-like growth factor II transcription by aflatoxin B1 induced p53 mutant 249 is caused by activation of transcription complexes; implications for a gain-of-function during the formation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 2000, 19, 3717–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwaifo, O. P53 gene of chang-liver cells (Atcc-Ccl13) exposed to aflatoxin B1 (Afb): the effect of lysine on mutation at codon 249 of exon 7. Afr J Med Med Sci 1999, 28, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Barraud, L.; Guerret, S.; Chevallier, M.; Borel, C.; Jamard, C.; Trepo, C.; Wild, C.P.; Cova, L. Enhanced duck hepatitis B virus gene expression following aflatoxin B1 exposure. Hepatology 1999, 29, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Yu, T.; Qin, W.; Liao, X.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Yu, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, C.; et al. Genome-wide association study of the TP53 R249S mutation in hepatocellular carcinoma with aflatoxin B1 exposure and infection with hepatitis B virus. J Gastrointest Oncol 2020, 11, 1333–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.N.; Li, L.Q.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Bai, T.; Xiang, B.D.; Qin, X.; Xiao, K.Y.; Peng, M.H.; Liu, Z.M.; et al. Genome-wide and differential proteomic analysis of hepatitis B virus and aflatoxin B1 related hepatocellular carcinoma in Guangxi, China. PLoS One 2013, 8, e83465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.W.; Chiang, Y.C.; Lien, J.P.; Chen, C.J. Plasma antioxidant vitamins, chronic hepatitis B virus infection and urinary aflatoxin B1-DNA adducts in healthy males. Carcinogenesis 1997, 18, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, S.; Ortiz-Cuaran, S.; Abedi-Ardekani, B.; Gouas, D.; Nogueira da Costa, A.; Plymoth, A.; Khuhaprema, T.; Kalalak, A.; Sangrajrang, S.; Friesen, M.D.; et al. Aflatoxin-induced TP53 R249S mutation in hepatocellular carcinoma in Thailand: association with tumors developing in the absence of liver cirrhosis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e37707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, L.; Thorgeirsson, S.S.; Gail, M.H.; Lu, P.; Harris, C.C.; Wang, N.; Shao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; et al. Dominant role of hepatitis B virus and cofactor role of aflatoxin in hepatocarcinogenesis in Qidong, China. Hepatology 2002, 36, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, C.C.; Kleiner, D.E.; Axiotis, C.A.; Di Bisceglie, A.; Nomura, A.M.; Stemmermann, G.N.; Tabor, E. Mutations of p53 gene in hepatocellular carcinoma: roles of hepatitis B virus and aflatoxin contamination in the diet. J Natl Cancer Inst 1992, 84, 1638–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M. p53 mutation in hepatocellular carcinoma after aflatoxin exposure. Lancet 1991, 338, 1356–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchio, A.; Amougou Atsama, M.; Béré, A.; Komas, N.P.; Noah Noah, D.; Atangana, P.J.A.; Camengo-Police, S.M.; Njouom, R.; Bekondi, C.; Pineau, P. Droplet digital PCR detects high rate of TP53 R249S mutants in cell-free DNA of middle African patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Med 2018, 18, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.N.; Bai, T.; Chen, Z.S.; Wu, F.X.; Chen, Y.Y.; De Xiang, B.; Peng, T.; Han, Z.G.; Li, L.Q. The p53 mutation spectrum in hepatocellular carcinoma from Guangxi, China : role of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and aflatoxin B1 exposure. Liver Int 2015, 35, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.S.; Ortiz, J.; Bendfeldt-Avila, G.; Xie, Y.; Wang, M.; Wu, D.; Higson, H.; Lee, E.; Teshome, K.; Barnoya, J.; et al. Analysis of. Health Sci Rep 2020, 3, e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés-Peregrina, E.N.; Sánchez-Hernández, B.E.; Gamboa-Domínguez, A. Metabolic Syndrome Instead of Aflatoxin-Related TP53 R249S Mutation as a Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk Factor. Rev Invest Clin 2020, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Hampton, L.L.; Luo, L.D.; Wirth, P.J.; Thorgeirsson, S.S. Low frequency of p53 gene mutation in tumors induced by aflatoxin B1 in nonhuman primates. Cancer Res 1992, 52, 1044–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Coursaget, P.; Depril, N.; Chabaud, M.; Nandi, R.; Mayelo, V.; LeCann, P.; Yvonnet, B. High prevalence of mutations at codon 249 of the p53 gene in hepatocellular carcinomas from Senegal. Br J Cancer 1993, 67, 1395–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineau, P.; Marchio, A.; Battiston, C.; Cordina, E.; Russo, A.; Terris, B.; Qin, L.X.; Turlin, B.; Tang, Z.Y.; Mazzaferro, V.; et al. Chromosome instability in human hepatocellular carcinoma depends on p53 status and aflatoxin exposure. Mutat Res 2008, 653, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuniholm, M.H.; Lesi, O.A.; Mendy, M.; Akano, A.O.; Sam, O.; Hall, A.J.; Whittle, H.; Bah, E.; Goedert, J.J.; Hainaut, P.; et al. Aflatoxin exposure and viral hepatitis in the etiology of liver cirrhosis in the Gambia, West Africa. Environ Health Perspect 2008, 116, 1553–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.W.; Yang, W.Y.; Lin, Y.M.; Jin, S.L.; Yuh, C.H. Hepatitis B virus X antigen and aflatoxin B1 synergistically cause hepatitis, steatosis and liver hyperplasia in transgenic zebrafish. Acta Histochem 2013, 115, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.W.; Lien, J.P.; Chiu, Y.H.; Santella, R.M.; Liaw, Y.F.; Chen, C.J. Effect of aflatoxin metabolism and DNA adduct formation on hepatocellular carcinoma among chronic hepatitis B carriers in Taiwan. J Hepatol 1997, 27, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, C.P.; Hasegawa, R.; Barraud, L.; Chutimataewin, S.; Chapot, B.; Ito, N.; Montesano, R. Aflatoxin-albumin adducts: a basis for comparative carcinogenesis between animals and humans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1996, 5, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, M.T.; Castañeda, C.; Ruisanchez, N.; Aleaga, M.; García, E.; Escobar, M.P. [Immunological detection of aflatoxin-albumin adducts in children with chronic hepatitis B infection]. G E N 1995, 49, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Hsu, W.L.; Yang, H.I.; Lee, M.H.; Chen, H.C.; Chien, Y.C.; You, S.L. Epidemiology of virus infection and human cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res 2014, 193, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hamadalnil, Y.; Tu, T. Hepatitis B Viral Protein HBx: Roles in Viral Replication and Hepatocarcinogenesis. Viruses 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.H.; Wang, Y.J.; Dong, W.; Xiang, S.; Liang, H.F.; Wang, H.Y.; Dong, H.H.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.P. Hepatic oval cell lines generate hepatocellular carcinoma following transfection with HBx gene and treatment with aflatoxin B1 in vivo. Cancer Lett 2011, 311, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, S.; Jaitovitch-Groisman, I.; Benlimame, N.; Galipeau, J.; Batist, G.; Alaoui-Jamali, M.A. Retroviral expression of the hepatitis B virus x gene promotes liver cell susceptibility to carcinogen-induced site specific mutagenesis. Mutat Res 2000, 460, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouas, D.A.; Shi, H.; Hautefeuille, A.H.; Ortiz-Cuaran, S.L.; Legros, P.C.; Szymanska, K.J.; Galy, O.; Egevad, L.A.; Abedi-Ardekani, B.; Wiman, K.G.; et al. Effects of the TP53 p.R249S mutant on proliferation and clonogenic properties in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines: interaction with hepatitis B virus X protein. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.; Liu, Y.; Yu, S.Z.; Qian, G.S.; Wan, S.G.; Dixon, K.R. Hepatitis B virus x gene and cyanobacterial toxins promote aflatoxin B1-induced hepatotumorigenesis in mice. World J Gastroenterol 2006, 12, 3065–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štampar, M.; Tomc, J.; Filipič, M.; Žegura, B. Development of in vitro 3D cell model from hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cell line and its application for genotoxicity testing. Arch Toxicol 2019, 93, 3321–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy-Yuzugullu, O.; Yuzugullu, H.; Yilmaz, M.; Ozturk, M. Aflatoxin genotoxicity is associated with a defective DNA damage response bypassing p53 activation. Liver Int 2011, 31, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Gu, J.; Patt, Y.; Hassan, M.; Spitz, M.R.; Beasley, R.P.; Hwang, L.Y. Mutagen sensitivity as a susceptibility marker for human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1998, 7, 567–570. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, I.C.; Tokiwa, T.; Bennett, W.; Metcalf, R.A.; Welsh, J.A.; Sun, T.; Harris, C.C. p53 gene mutation and integrated hepatitis B viral DNA sequences in human liver cancer cell lines. Carcinogenesis 1993, 14, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, P.C.; Mendy, M.; Whittle, H.; Fortuin, M.; Hall, A.J.; Wild, C.P. Hepatitis B infection and aflatoxin biomarker levels in Gambian children. Trop Med Int Health 2000, 5, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.J.; Wild, C.P.; Wheeler, J.G.; Riley, E.M.; Montesano, R.; Bennett, S.; Whittle, H.C.; Hall, A.J.; Greenwood, B.M. Aflatoxin exposure, malaria and hepatitis B infection in rural Gambian children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1992, 86, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.Y.; Hatch, M.; Chen, C.J.; Levin, B.; You, S.L.; Lu, S.N.; Wu, M.H.; Wu, W.P.; Wang, L.W.; Wang, Q.; et al. Aflatoxin exposure and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Int J Cancer 1996, 67, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groopman, J.D.; Hall, A.J.; Whittle, H.; Hudson, G.J.; Wogan, G.N.; Montesano, R.; Wild, C.P. Molecular dosimetry of aflatoxin-N7-guanine in human urine obtained in The Gambia, West Africa. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1992, 1, 221–227. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).