Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

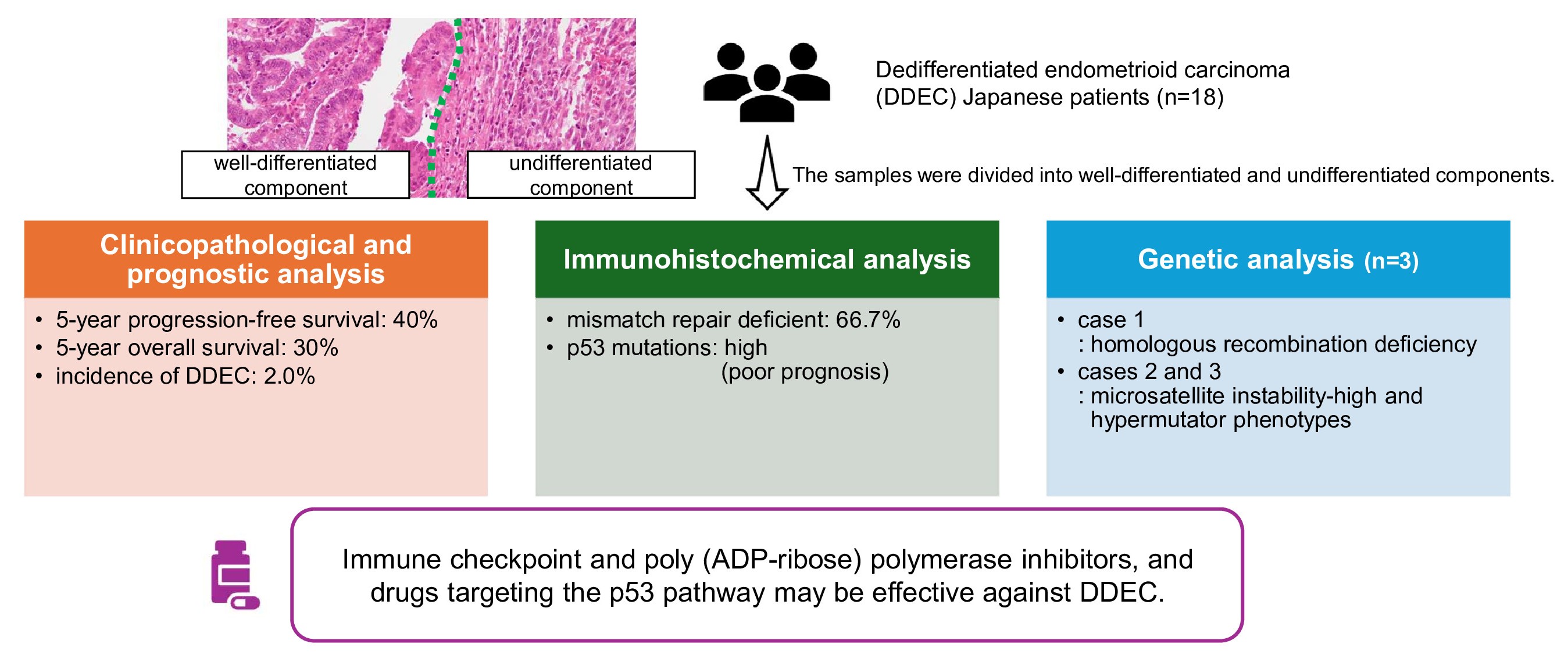

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Natural Incidence Histology and Clinicopathological Characteristics

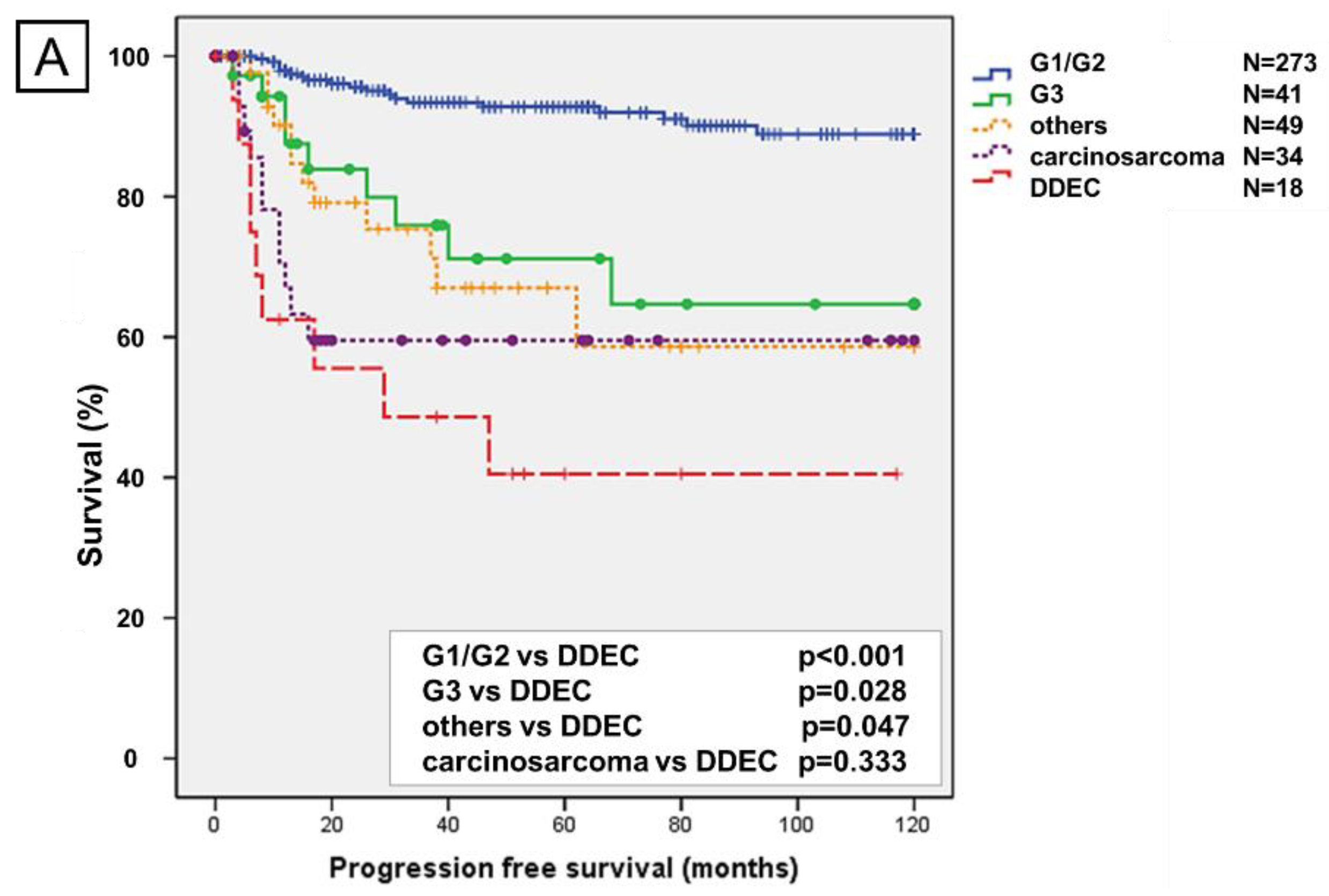

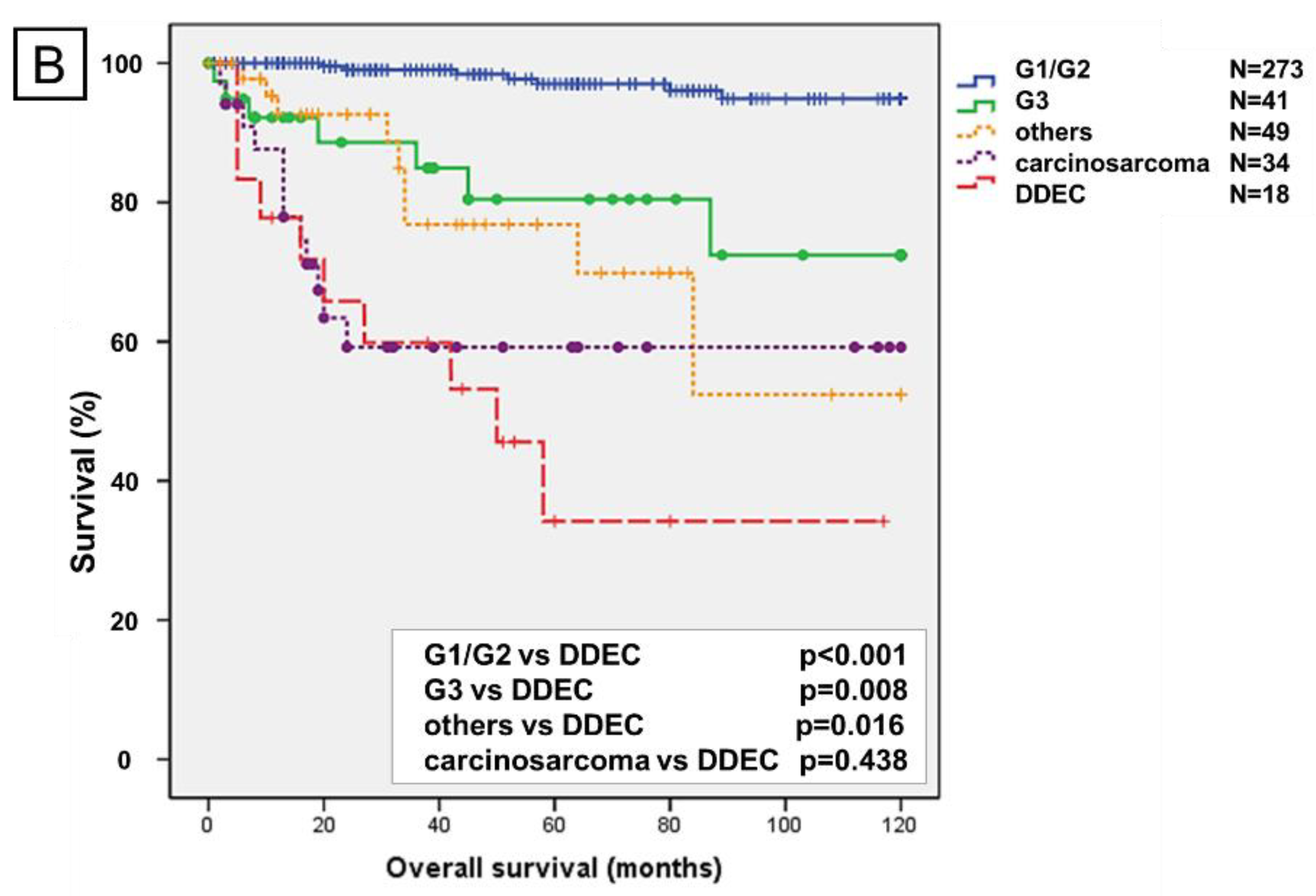

2.2. Prognostic Analysis Using the Kaplan–Meier Method

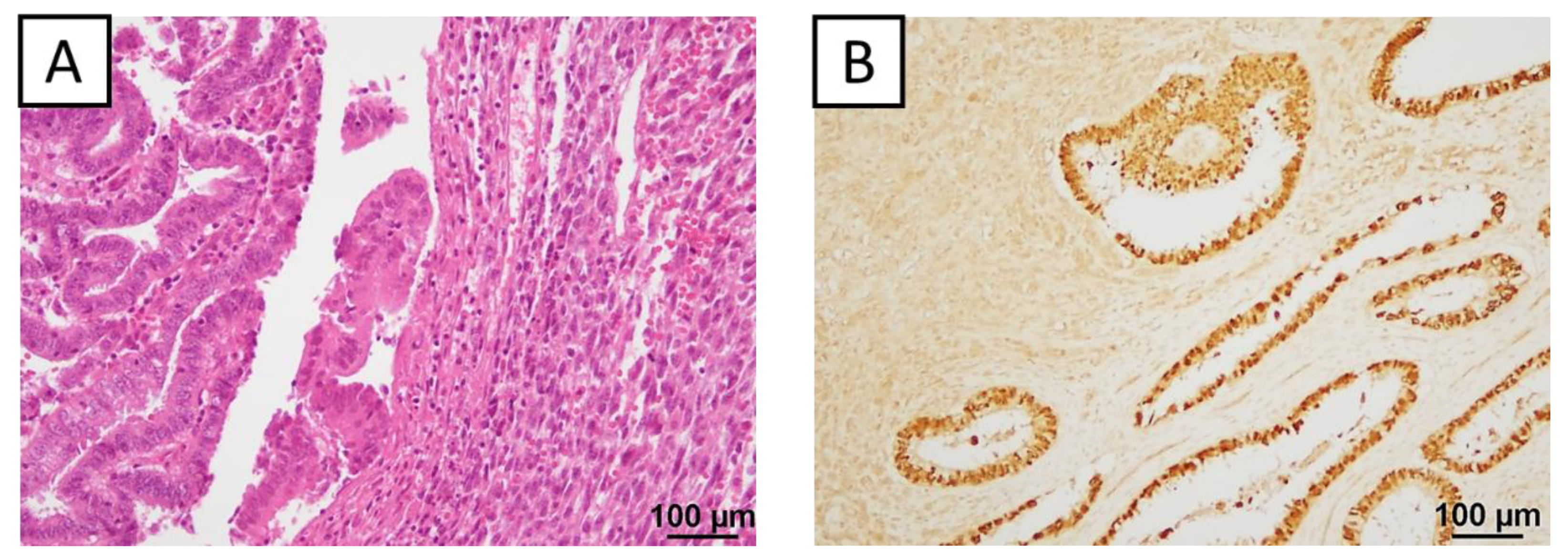

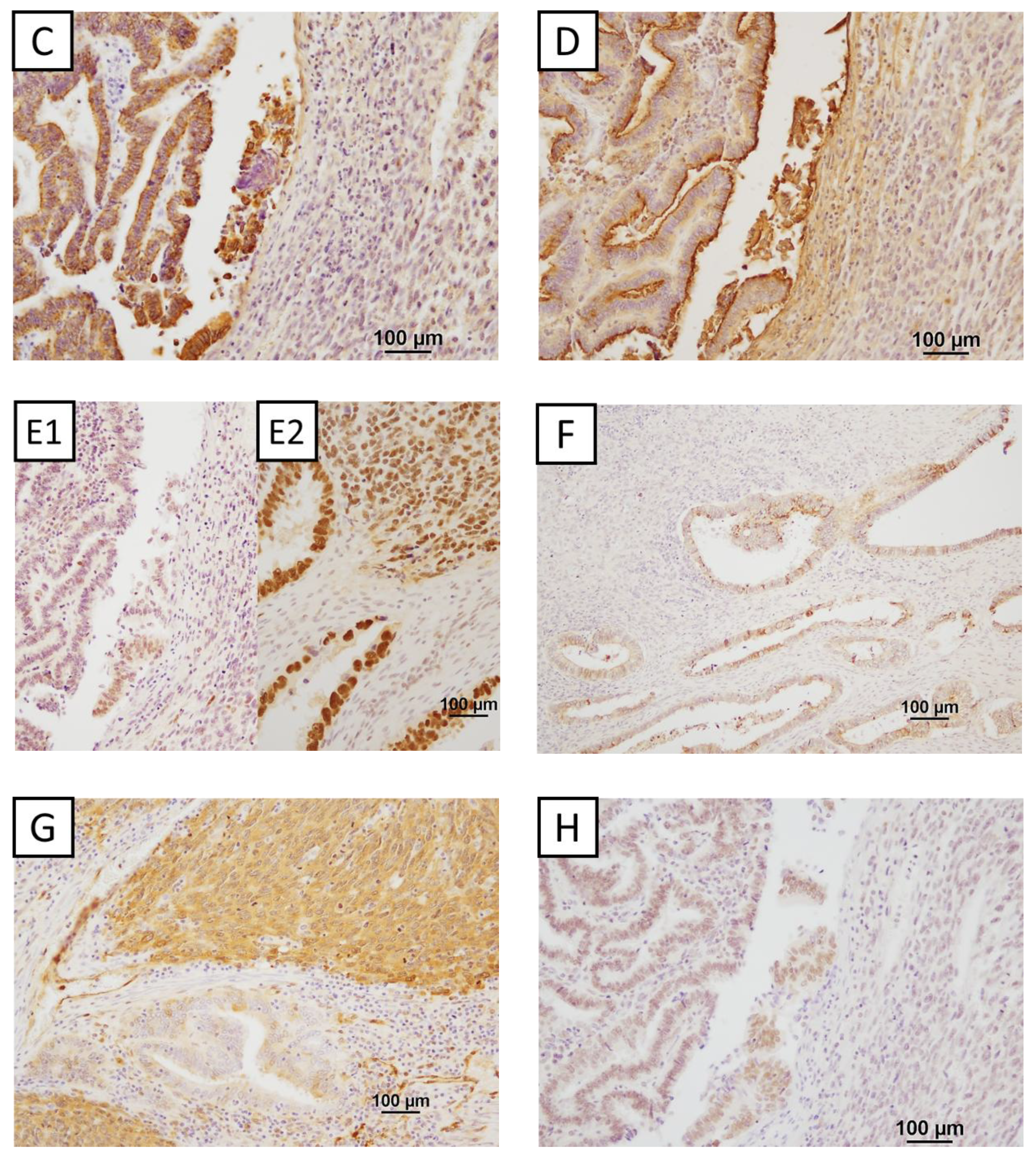

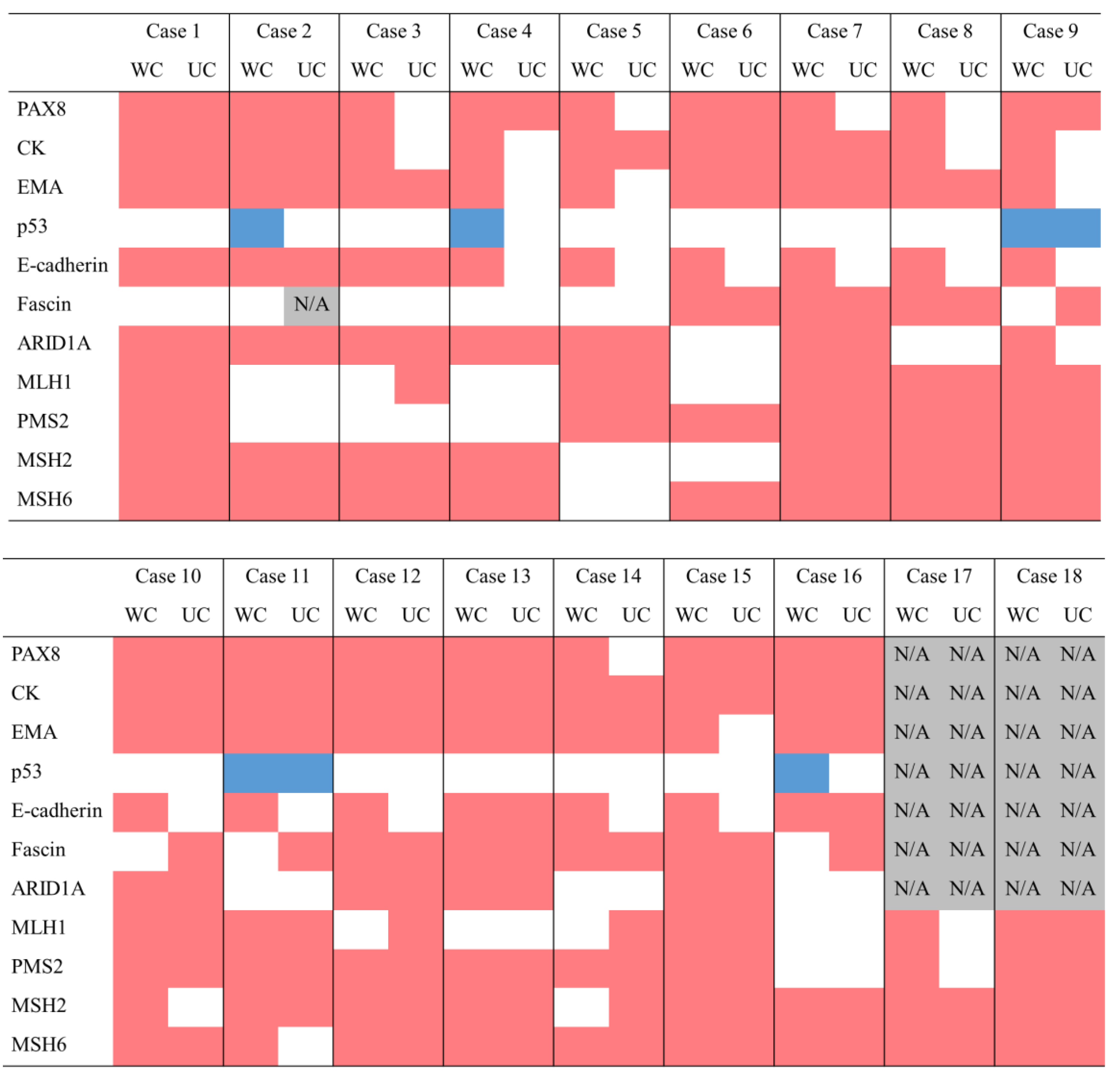

2.3. Immunohistochemical Findings

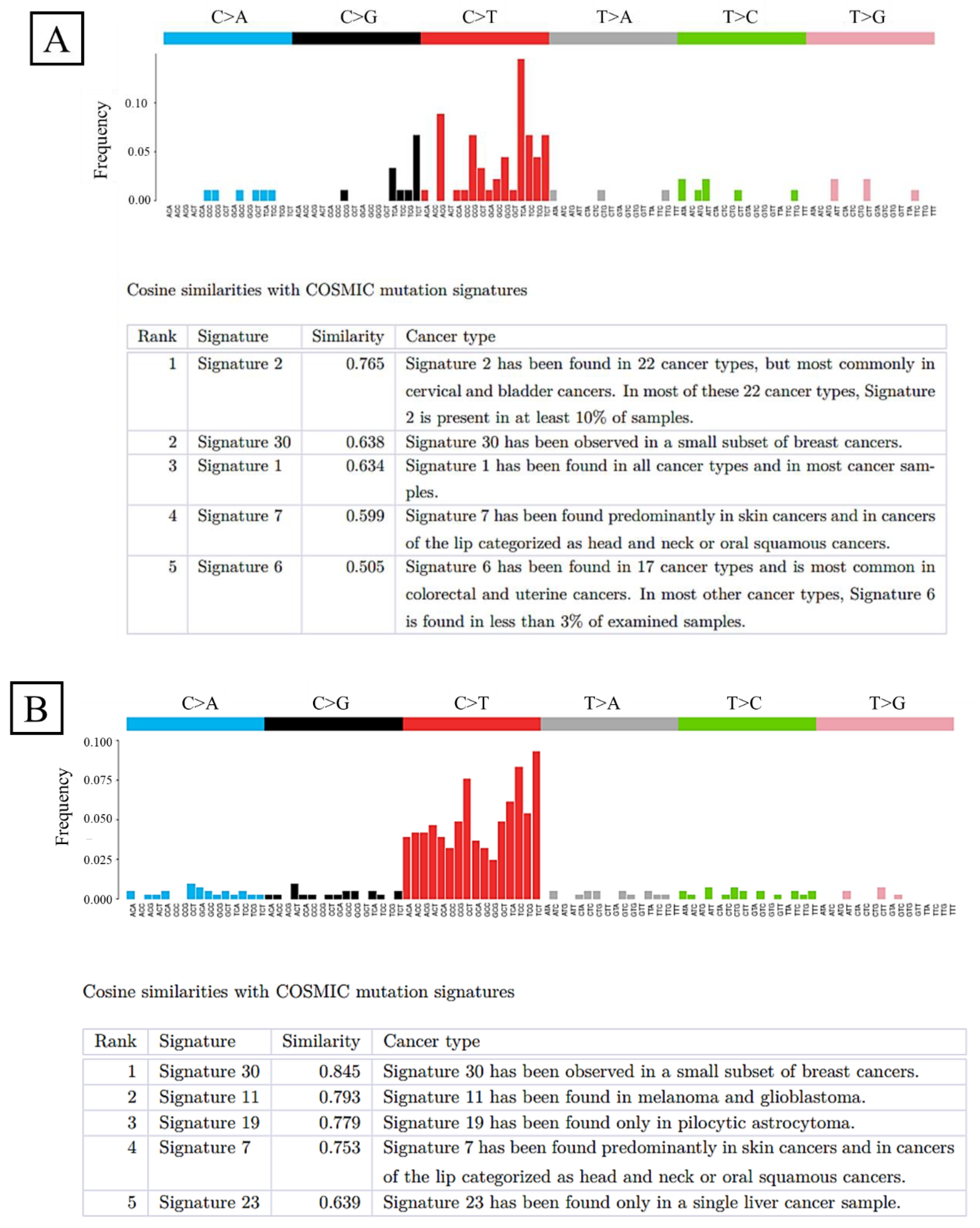

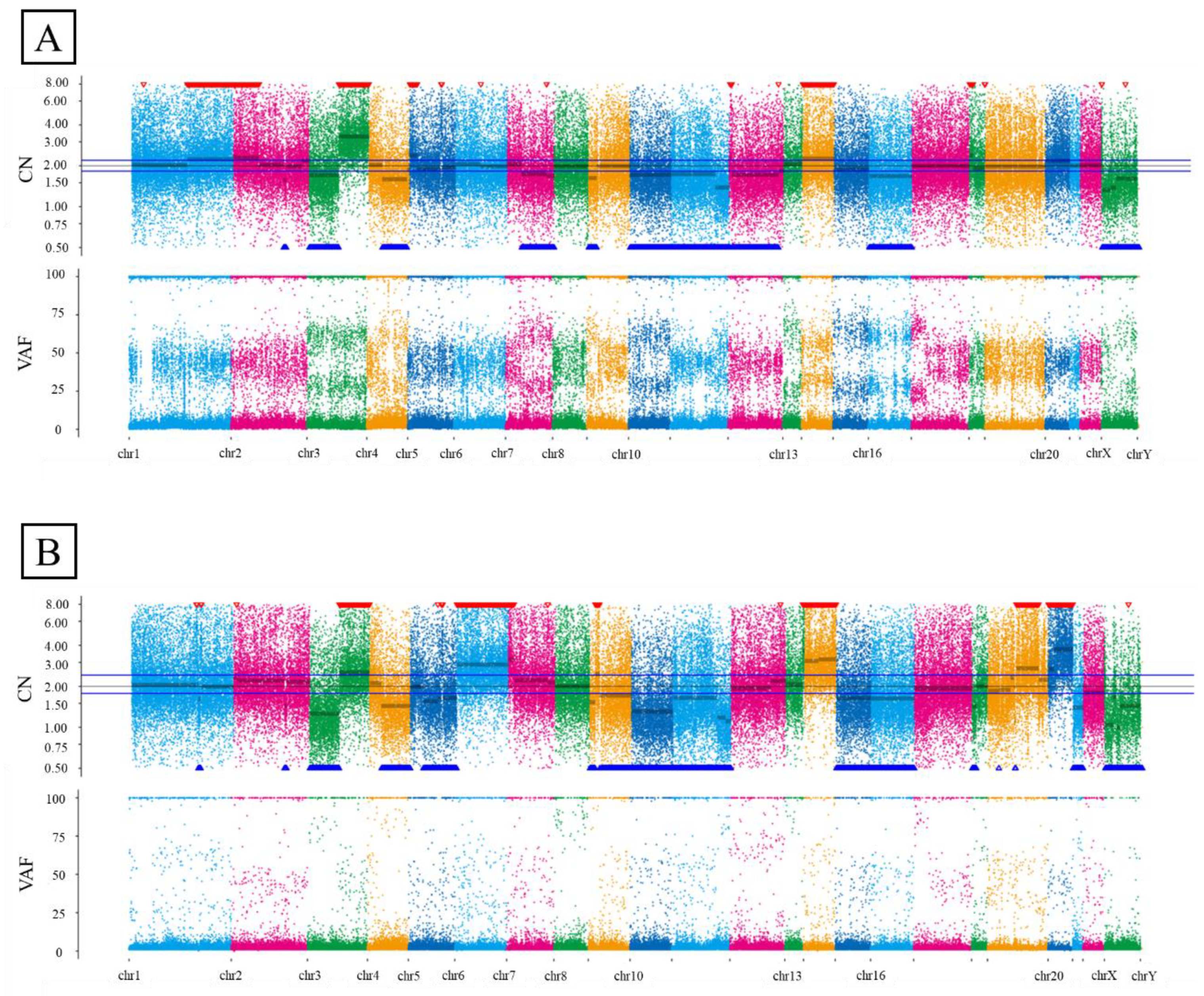

2.4. Whole-Exome Sequencing

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Samples

4.2. Immunohistochemistry

4.3. DNA Extraction

4.4. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, E.G.; Deavers, M.T.; Bodurka, D.C.; Malpica, A. Association of low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of the uterus and ovary with undifferentiated carcinoma: a new type of dedifferentiated carcinoma? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006, 25, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaino, R.; Carinelli, S.G.; Eng, C.; Kurman, R.J.; Carcangiu, M.L.; Herrington, C.S.; Young, R.H. WHO Classification of tumours of Female Reproductive Organs: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. 4th ed. IARC Press; Lyon, France; 2014.

- Cree, I.A.; White, V.A.; Indave, B.I.; Lokuhetty, D. Revising the WHO classification: female genital tract tumours. Histopathology. 2020, 76, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, E.G.; Deavers, M.T.; Malpica, A. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the endometrium: a review. Pathology. 2007, 39, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHilli, M.; Elson, P.; Rybicki, L.; Amarnath, S.; Yang, B.; Michener, C.M.; Rose, P.G. Undifferentiated endometrial carcinoma: a National Cancer Database analysis of prognostic factors and treatment outcomes. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019, 29, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafe, L.J.; Garg, K.; Chew, I.; Tornos, C.; Soslow, R.A. Endometrial and ovarian carcinomas with undifferentiated components: clinically aggressive and frequently underrecognized neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2010, 23, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, C. Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical characterization of dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2016, 24, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altrabulsi, B.; Malpica, A.; Deavers, M.T.; Bodurka, D.C.; Broaddus, R.; Silva, E.G. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the endometrium. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005, 29, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.N.; Tinker, A.V.; Kwon, J.; Lim, P.; Kong, I.; Sihra, S.; Koebel, M.; Lee, C.H. Treatment and outcomes in undifferentiated and dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma. J Gynecol Oncol. 2022, 33, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier-Cloutier, B.; Coatham, M.; Carey, M.; Nelson, G.S.; Hamilton, S.; Lum, A.; Soslow, R.A.; Stewart, C.J.; Postovit, L.M.; Köbel, M.; Lee, C.H. SWI/SNF-deficiency defines highly aggressive undifferentiated endometrial carcinoma. J Pathol Clin Res. 2021, 7, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onder, S.; Taskin, O.C.; Sen, F.; Topuz, S.; Kucucuk, S.; Sozen, H.; Ilhan, R.; Tuzlali, S.; Yavuz, E. High expression of SALL4 and fascin, and loss of E-cadherin expression in undifferentiated/dedifferentiated carcinomas of the endometrium: An immunohistochemical and clinicopathologic study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017, 96, e6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, Robertson AG, Pashtan I, Shen R, Benz CC, Yau C, Laird PW, Ding L, Zhang W, Mills GB, Kucherlapati R, Mardis ER, Levine DA. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 497, 67–73. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rustum, N.; Yashar, C.; Arend, R.; Barber, E.; Bradley, K.; Brooks, R.; Campos, S.M.; Chino, J.; Chon, H.S.; Chu, C.; Crispens, M.A.; Damast, S.; Fisher, C.M.; Frederick, P.; Gaffney, D.K.; Giuntoli, R.; Han, E.; Holmes, J.; Howitt, B.E.; Lea, J.; Mariani, A.; Mutch, D.; Nagel, C.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Podoll, M.; Salani, R.; Schorge, J.; Siedel, J.; Sisodia, R.; Soliman, P.; Ueda, S.; Urban, R.; Wethington, S.L.; Wyse, E.; Zanotti, K.; McMillian, N.R.; Aggarwal, S. Uterine Neoplasms, Version 1.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023, 21, 181–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Vergote, I.; Cibula, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Marnitz, S.; Ledermann, J.; Bosse, T.; Chargari, C.; Fagotti, A.; Fotopoulou, C.; Gonzalez Martin, A.; Lax, S.; Lorusso, D.; Marth, C.; Morice, P.; Nout, R.A.; O'Donnell, D.; Querleu, D.; Raspollini, M.R.; Sehouli, J.; Sturdza, A.; Taylor, A.; Westermann, A.; Wimberger, P.; Colombo, N. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021, 31, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Rosa, J.M.; Leskelä, S.; Cristóbal-Lana, E.; Santón, A.; López-García, M.Á.; Muñoz, G.; Pérez-Mies, B.; Biscuola, M.; Prat, J.; Esther, O.; Soslow, R.A.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Palacios, J. Molecular genetic heterogeneity in undifferentiated endometrial carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2016, 29, 1390–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taira, Y.; Shimoji, Y.; Arakaki, Y.; Nakamoto, T.; Kudaka, W.; Aoki, Y. Comprehensive genomic profiling for therapeutic decision and identification of gene mutation in uterine endometrial dedifferentiated carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2022, 15, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacking, S.; Jin, C.; Komforti, M.; Liang, S.; Nasim, M. MMR deficient undifferentiated/dedifferentiated endometrial carcinomas showing significant programmed death ligand-1 expression (sp 142) with potential therapeutic implications. Pathol Res Pract. 2019, 215, 152552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Mehta, J.; Borges, A.M. Role of SMARCA4 (BRG1) and SMARCB1 (INI1) in dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma with paradoxical aberrant expression of MMR in the well-differentiated component: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2021, 29, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehl, J.D.; Wachter, D.L.; Fiedler, J.; Heimerl, E.; Beckmann, M.W.; Hartmann, A.; Agaimy, A. Pattern of SMARCB1 (INI1) and SMARCA4 (BRG1) in poorly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus: analysis of a series with emphasis on a novel SMARCA4-deficient dedifferentiated rhabdoid variant. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015, 19, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E.; Ayhan, A.; Bahadirli-Talbott, A.; Zhao, C.; Shih, I.e.M. Molecular characterization of undifferentiated carcinoma associated with endometrioid carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014, 38, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, H.J.; Wu, R.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Lai, C.H. Rare subtype of endometrial cancer: Undifferentiated/dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma, from genetic aspects to clinical practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, G.; Ferioli, E.; Guareschi, D.; Tafuni, A. Dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma: A rare aggressive neoplasm-clinical, morphological and immunohistochemical features. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, C.; Farah, B.L.; Ho, W.Y.; Wong, S.L.; Goh, C.H.R.; Chew, S.H.; Nadarajah, R.; Lim, Y.K.; Ho, T.H. Dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus: A case series and review of literature. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2020, 32, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, H.; Cao, J.; Li, Y.; Cheng, W.; Luo, C. Analysis of prognostic factors and cancer-specific survival in patients with undifferentiated and dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma undergoing various postoperative adjuvant therapies. Cancer Manag Res. 2024, 16, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, R.; Davidson, B.; Fadare, O.; Carlson, J.A.; Crum, C.P.; Gilks, C.B.; Irving, J.A.; Malpica, A.; Matias-Guiu, X.; McCluggage, W.G.; Mittal, K.; Oliva, E.; Parkash, V.; Rutgers, J.K.L.; Staats, P.N.; Stewart, C.J.R.; Tornos, C.; Soslow, R.A. High-grade endometrial carcinomas: Morphologic and immunohistochemical features, diagnostic challenges and recommendations. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019, 38, S40–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Du, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, C. Clinicopathological significance of multiple molecular features in undifferentiated and dedifferentiated endometrial carcinomas. Pathology. 2021, 53, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, I.; Lee, C.H.; D'Angelo, E.; Palacios, J.; Prat, J. Undifferentiated and dedifferentiated endometrial carcinomas with POLE exonuclease domain mutations have a favorable prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017, 41, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, V.W.; Yang, H.P.; Pike, M.C.; McCann, S.E.; Yu, H.; Xiang, Y.B.; Wolk, A.; Wentzensen, N.; Weiss, N.S.; Webb, P.M.; et al. Type I and II endometrial cancers: have they different risk factors? J Clin Oncol. 2013, 31, 2607–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, M.; Asano, N.; Katayama, K.; Yoshida, A.; Tsuda, Y.; Sekimizu, M.; Mitani, S.; Kobayashi, E.; Komiyama, M.; Fujimoto, H.; Goto, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Naka, N.; Iwata, S.; Nishida, Y.; Hiruma, T.; Hiraga, H.; Kawano, H.; Motoi, T.; Oda, Y.; Matsubara, D.; Fujita, M.; Shibata, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Nakayama, R.; Kondo, T.; Imoto, S.; Miyano, S.; Kawai, A.; Yamaguchi, R.; Ichikawa, H.; Matsuda, K. Integrated exome and RNA sequencing of dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, R.; Nakayama, K.; Nakamura, K.; Yamashita, H.; Ishibashi, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Minamoto, T.; Razia, S.; Ishikawa, N.; Otsuki, Y.; Nakayama, S.; Onuma, H.; Kurioka, H.; Kyo, S. Dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma could be a target for immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies). Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcarcel-Jimenez, L.; Frezza, C. Fumarate hydratase (FH) and cancer: a paradigm of oncometabolism. Br J Cancer. 2023, 129, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Harper, A.; Imm, K.R.; Grubb RL 3rd Kim, E.H.; Colditz, G.A.; Wolin, K.Y.; Kibel, A.S.; Sutcliffe, S. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. J Urol. 2007, 177, 2074–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, K.; Nakayama, K.; Razia, S.; Islam, S.H.; Farzana, Z.U.; Sonia, S.B.; Sasamori, H.; Yamashita, H.; Ishibashi, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Imamura, K.; Ishikawa, N.; Kyo, S. Molecular analysis of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma exhibiting low-grade serous carcinoma and serous borderline tumor. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024, 46, 9376–9385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Endometrial Carcinoma V.3.2024.

- Travaglino, A.; Raffone, A.; Mascolo, M.; Guida, M.; Insabato, L.; Zannoni, G.F.; Zullo, F. TCGA molecular subgroups in endometrial undifferentiated/dedifferentiated carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020, 26, s12253–s019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.M.; Rushton, T.; Nsiah, F.; Stone, R.L.; Beavis, A.L.; Gaillard, S.L.; Dobi, A.; Fader, A.N. Long-term disease-free survival with chemotherapy and pembrolizumab in a patient with unmeasurable, advanced stage dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2024, 53, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Malley, D.M.; Krivak, T.C.; Kabil, N.; Munley, J.; Moore, K.N. PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: A review. Target Oncol. 2023, 18, 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, S.N.; Moore, K.; Chon, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Thomes Pepin, J.; Sundborg, M.; Shai, A.; de la Garza, J.; Nishio, S.; Gold, M.A.; et al. Durvalumab plus carboplatin/paclitaxel followed by maintenance durvalumab with or without olaparib as first-line treatment for advanced endometrial cancer: The Phase III DUO-E Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024, 42, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, P.; Trillsch, F.; Okamoto, A.; Reuss, A.; Kim, J.-W.; Rubio Pérez, M.J.; Vardar, M.A.; Scambia, G.; Trédan, O.; Nyvang, G.; Colombo, N.; Chudecka-Głaz, A.; Grimm, C.; e Lheureux, S.; Van Nieuwenhuysen, E.; Heitz, F.; Wenham, R.M.; Ushijima, K.; Day, E.; Aghajanian, C. Durvalumab with paclitaxel/carboplatin (PC) and bevacizumab (bev), followed by maintenance durvalumab, bev, and olaparib in patients (pts) with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (AOC) without a tumor BRCA1/2 mutation (non-tBRCAm): results from the randomized, placebo (pbo)-controlled phase III DUO-O trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41, abstr LBA5506. [Google Scholar]

- Sallman, D.A.; DeZern, A.E.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Steensma, D.P.; Roboz, G.J.; Sekeres, M.A.; Cluzeau, T.; Sweet, K.L.; McLemore, A.; McGraw, K.L.; Puskas, J.; Zhang, L.; Yao, J.; Mo, Q.; Nardelli, L.; Al Ali, N.H.; Padron, E.; Korbel, G.; Attar, E.C.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Lancet, J.E.; Fenaux, P.; List, A.F.; Komrokji, R.S. Eprenetapopt (APR-246) and azacitidine in TP53-mutant myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2021, 39, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embaby, A.; Kutzera, J.; Geenen, J.J.; Pluim, D.; Hofland, I.; Sanders, J.; Lopez-Yurda, M.; Beijnen, J.H.; Huitema, A.D.R.; Witteveen, P.O.; Steeghs, N.; van Haaften, G.; van Vugt, M.A.T.M.; de Ridder, J.; Opdam, F.L. WEE1 inhibitor adavosertib in combination with carboplatin in advanced TP53 mutated ovarian cancer: A biomarker-enriched phase II study. Gynecol Oncol. 2023, 174, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Lyu, J.; Yang, E.J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Shim, J.S. Targeting AURKA-CDC25C axis to induce synthetic lethality in ARID1A-deficient colorectal cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liewer, S.; Huddleston, A. Alisertib: a review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and toxicity in patients with hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2018, 27, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, K.; Takebayashi, Y.; Nakayama, S.; Hata, K.; Fujiwaki, R.; Fukumoto, M.; Miyazaki, K. Prognostic value of overexpression of p53 in human ovarian carcinoma patients receiving cisplatin. Cancer Lett. 2003, 192, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagiri, A.; Nakayama, K.; Rahman, M.T.; Rahman, M.; Katagiri, H.; Nakayama, N.; Ishikawa, M.; Ishibashi, T.; Iida, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Otsuki, Y.; Nakayama, S.; Miyazaki, K. Loss of ARID1A expression is related to shorter progression-free survival and chemoresistance in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012, 25, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H.; Nakayama, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Nakamura, K.; Ishibashi, T.; Sanuki, K.; Ono, R.; Sasamori, H.; Minamoto, T.; Iida, K.; Sultana, R.; Ishikawa, N.; Kyo, S. Microsatellite instability is a biomarker for immune checkpoint inhibitors in endometrial cancer. Oncotarget. 2017, 9, 5652–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Aimono, E.; Tanishima, S.; Imai, M.; Nagatsuma, A.K.; Hayashi, H.; Yoshimura, Y.; Nakayama, K.; Kyo, S.; Nishihara, H. Intratumoral genomic heterogeneity may hinder precision medicine strategies in patients with serous ovarian carcinoma. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurose, S.; Nakayama, K.; Razia, S.; Ishikawa, M.; Ishibashi, T.; Yamashita, H.; Sato, S.; Sakiyama, A.; Yoshioka, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Nakayama, S.; Otuski, Y.; Ishikawa, N.; Kyo, S. Whole-exome sequencing of rare site endometriosis-associated cancer. Diseases 2021, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Wu, R.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Lai, C.H.; Chao, A.S.; Li, H.P.; Tsai, C.L.; Kuek, E.J.; Hsu, C.L.; Chao, A. A patient-derived xenograft model of dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma: A proof-of-concept study for the identification of new molecularly informed treatment approaches. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Histology | Number of Patients (n = 255) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Endometrioid carcinoma G1/G2 | 188 | 73.7 |

| Endometrioid carcinoma G3 | 23 | 9.0 |

| Others | 39 | 15.3 |

| Serous carcinoma | 28 | 11.0 |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 6 | 2.4 |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 5 | 2.0 |

| Dedifferentiated endometrioid carcinoma | 5 | 2.0 |

| Characteristic | G1/G2 | p-value | G3 | p-value | Others | p-value | Carcino sarcoma |

p-value | DDEC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (%) | 0.554 | 0.931 | 0.102 | 0.053 | |||||||

| <60 | 156 (57) | 20 (49) | 14 (29) | 8 (24) | 9 (50) | ||||||

| ≧60 | 117 (43) | 21 (51) | 35 (71) | 26 (76) | 9 (50) | ||||||

| FIGO Stage (%) | <0.01 | 0.011 | 0.024 | 0.236 | |||||||

| Ⅰ, Ⅱ | 236 (87) | 27 (66) | 30 (61) | 16 (48) | 5 (28) | ||||||

| Ⅲ, Ⅳ | 36 (13) | 14 (34) | 19 (39) | 17 (52) | 13 (72) | ||||||

| Muscle invasion (%) | <0.01 | 0.032 | <0.01 | 0.055 | |||||||

| <50% | 195 (72) | 17 (42.5) | 28 (61) | 6 (46) | 2 (12.5) | ||||||

| ≧50% | 77 (28) | 23 (57.5) | 18 (39) | 7 (54) | 14 (87.5) | ||||||

| LVSI (%) | <0.01 | 0.244 | 0.036 | 0.317 | |||||||

| Yes | 105 (39) | 29 (74) | 27 (59) | 12 (100) | 14 (87.5) | ||||||

| No | 162 (61) | 10 (26) | 19 (41) | 0 (0) | 2 (12.5) | ||||||

| Pelvic/Para aortic lymph metastasis (%) |

<0.01 | 0.297 | 0.213 | 0.170 | |||||||

| Yes | 26 (10) | 12 (29) | 13 (27) | 9 (69) | 7 (44) | ||||||

| No | 247 (90) | 29 (71) | 35 (73) | 4 (31) | 9 (56) | ||||||

| WC | UC | |||

| type | type | |||

| Case1 | LOH high | 21.57% | LOH high | 22.371% |

| Case2 | TMB high | 227 | TMB high | 1927 |

| MSI high | 30.25% | MSI high | 36.38% | |

| Case3 | TMB high | 1099 | TMB high | 15105 |

| MSI high | 28.88% | |||

| Antibody | Producer | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| PAX8 | Proteintech (10336-1-AP) | 1:500 |

| CK | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-8018) | 1:50 |

| EMA | Thermo Fisher Scientific (MA1-06503) | 1:100 |

| p53 | Dako (M7001) | 1:50 |

| E-cadherin | abcam (ab15148) | 1:50 |

| Fascin | Thermo Fisher Scientific (MAF-11483) | 1:200 |

| ARID1A | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-32761) | 1:100 |

| MLH1 | Dako (M3640) | 1:50 |

| PMS2 | Dako (M3647) | 1:40 |

| MSH2 | Dako (M3639) | 1:50 |

| MSH6 | Dako (M3646) | 1:50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).