1. Introduction

When a laser beam propagates through the atmosphere, it is significantly influenced by small temperature fluctuations, as well as wind shear and turbulence. These factors lead to irregular distributions of the refractive index in both space and time, resulting in the distortion of the laser wavefront. Consequently, this distortion degrades the coherence of the laser, causes dissipation of laser energy, and significantly impacts the transmission efficiency of the laser [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Specifically, atmospheric turbulence can cause several detrimental effects on laser communication:

Beam Spread: Atmospheric turbulence causes the laser beam to spread out as it propagates, leading to a larger spot size at the receiver and reduced signal intensity [

1,

2].

Beam Wander: The random variations in the refractive index cause the laser beam to wander off its intended path, making it difficult for the receiver to maintain alignment and track the beam accurately [

1,

2].

Angle-of-Arrival Fluctuations: The angle at which the laser beam arrives at the receiver fluctuates due to turbulence, complicating the task of maintaining optimal alignment and reducing the efficiency of signal reception [

1,

2].

Scintillation: The intensity of the laser beam fluctuates randomly as it propagates through the turbulent atmosphere, leading to signal fading and increased error rates [

1,

2].

Phase Distortion: Turbulence induces random phase changes in the laser beam, which can degrade the performance of coherent communication systems by reducing the mixing efficiency and increasing error rates [

1,

2].

Currently, the random phase screen method, based on wave theory, is commonly used to simulate laser beam propagation in a turbulent atmosphere [

5,

6]. It models the continuous medium along the laser path as discrete phase screens and treats the optical-field propagation between them as vacuum diffraction. Specifically, before reaching each screen, the optical field undergoes vacuum diffraction and is then modulated by phase screens. Iterating this process in a sequential manner can efficiently simulate the laser beam propagation in turbulent media.

The key steps in this numerical simulation encompass the computation of phase screens and the diffraction of the optical field. For the diffraction calculation, it is typically addressed by the split-step method based on the Fresnel diffraction in angular spectrum form, which has become a well-established approach in numerical diffraction computations [

7]. Regarding the phase screen calculation, the power-spectrum inversion algorithm is widely utilized to generate phase screens [

8,

9,

10]. Considering its substantial influence on the simulation results, a great deal of research has been to enhance computational efficiency without compromising accuracy, including sparse spectrum technology introduced by Charnotskii [

11,

12] , random subharmonic sampling by Paulson [

13] and sinc series approximation based method introduced by Cubillos[

14]. Additionally, the authors have proposed a phase screen generation technique based on sampling optimization [

15,

16]. All these methods are aimed at improving the speed and precision of phase screen generation by sampling the refractive index spectrum.

Despite these advancements, several challenges persist. Even though remarkable improvements have been made in numerical simulation efficiency, achieving real-time applicability is still extremely difficult. This is mainly attributed to two key factors. Firstly, each transmission calculation involves multiple iterations of diffraction and modulation processes, which are inherently time-consuming operations. Secondly, given the stochasticity of atmospheric turbulence, obtaining the necessary optical field statistics demands statistical analysis of a large number of samples. Typically, this can only be accomplished through ensemble average. These challenges are deeply rooted in the numerical computation approach, indicating that mere algorithmic improvements are insufficient to significantly enhance the simulation speed.

Fortunately, recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, specifically generative AI, present promising solutions for these challenges. In the realm of image generation, generative AI has witnessed remarkable progress. It has evolved from variational autoencoders [

17] and generative adversarial networks [

18,

19] (GAN) to the state-of-the-art diffusion models [

20], which have substantially enhanced both image quality and content control. In our study, taking the initial optical field distribution as input and atmospheric turbulence conditions as control parameters, generative AI can generate the atmospheric-turbulence-altered intensity distribution on the received plane.

Among the aforementioned generative AI frameworks, GANs stand out for their rapid output capabilities, generating the intensity distribution of laser transmission through atmospheric turbulence more efficiently than diffusion models, which require multiple denoising steps. By avoiding the blurring issues associated with variational autoencoders, GANs are particularly well-suited for the fast field mapping of laser transmission under a turbulent atmosphere. Thus, here we focus on a GAN-based architecture, designing a specialized neural network structure tailored for simulating laser beam propagation in the turbulent atmosphere. Through adversarial training, the authors have achieved fast and stable simulations for laser beam propagation in atmospheric turbulence.

2. Network Design

2.1. The Laser Beam Model

The goal of the proposed model is to simulate the intensity distribution of a laser beam after propagating through turbulent atmospheres. The input to the model is the optical field distribution at the source plane, and the output is the intensity distribution on the receiving plane, while the transmission distance and the refractive index structure constant are provided as additional control parameters in the bottleneck layer.

The mathematical model for laser beam propagation in turbulent atmospheres is based on the split-step method using Fresnel diffraction in angular spectrum form [

6,

21]. The propagation process can be expressed as:

where,

is the spatial distribution of the optical field at the source plane.

m serves as the scaling parameter that controls the spatial sampling interval on the receiving plane, which helps accommodate the beam width increase caused by turbulence and diffraction effects.

Q,

F,

,

T are a set of operators. Specifically,

Q represents the second-order phase factor,

F represents the Fourier Transform,

represents the Inverse Fourier Transform, and

T represents the phase modulation induced by turbulence. They are defined as follows:

where,

represents the phase screen that can be calculated via phase screen generation method based on spectral inversion:

In Eq.(6),

represents complex Hermitian Gaussian random matrix with zero mean and unit variance.

denote the power spectral density function that conforms to the atmospheric turbulence spectrum.

and

are the spatial frequencies in the

x direction and

y direction, respectively. The power spectral density function that follows the Kolmogorov spectrum can be expressed as:

where

represents the atmospheric coherence length, also known as the Fried parameter [

1]. It is related to the refractive index structure constant

and the propagation distance

z in a Kolmogorov spectrum:

2.2. Proposed GAN Architecture

By analyzing the calculation process of the above-mentioned model, it can be deduced that to complete the calculation of laser beam propagation in turbulent atmosphere, it is essential to feed the source-plane optical-field distribution, transmission distance

z, and refractive index structure constant

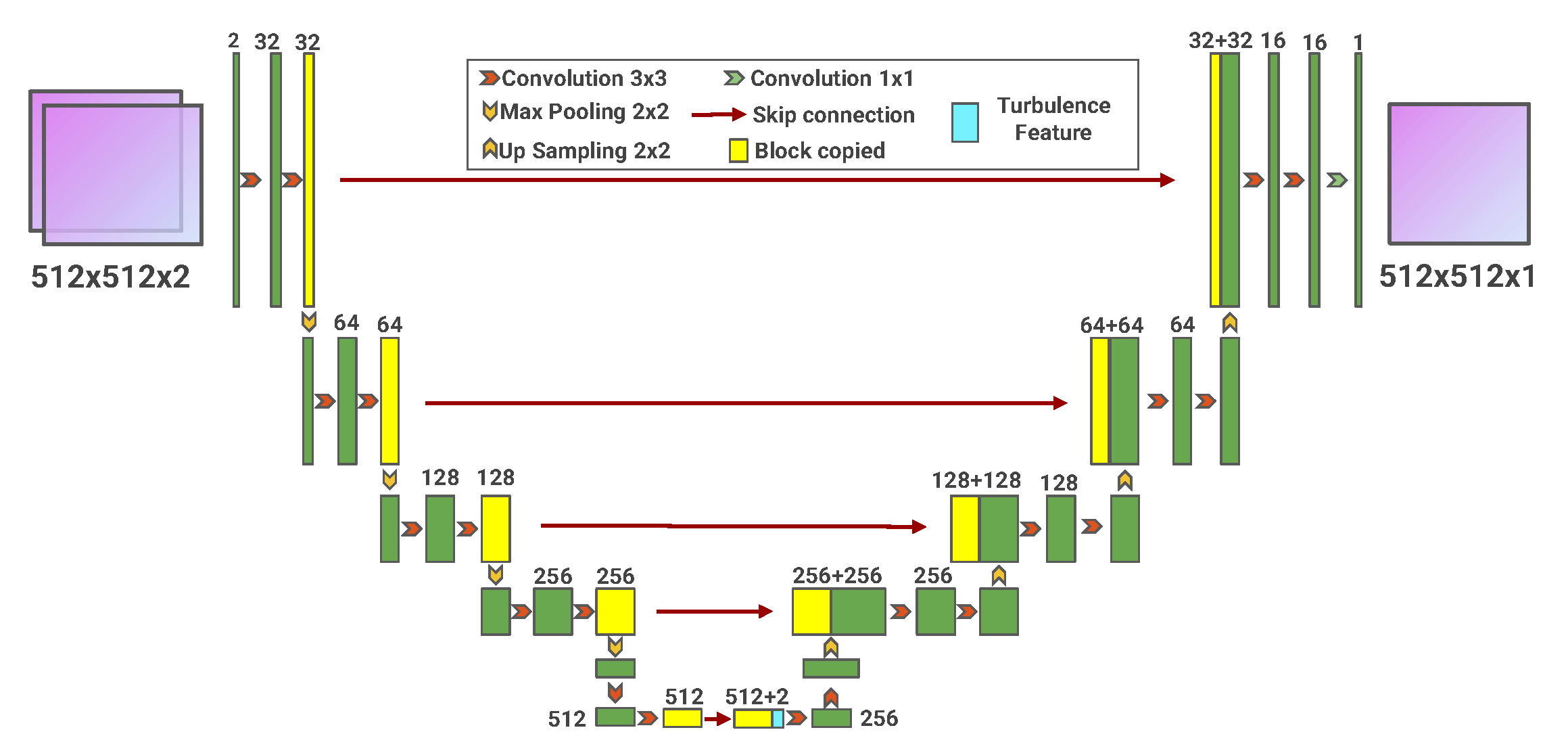

into the calculation model as inputs, and the final output is the optical-field distribution on the receiving plane. To simulate this process efficiently, we propose a GAN-based architecture. The generator, based on the U-Net [

22] network, takes the source-plane optical field distribution as input and outputs the intensity distribution on the receiving plane. The discriminator, based on the PatchGAN network [

23], evaluates the quality of the generated samples. The structure of the U-Net generator is shown in

Figure 1.

As depicted in

Figure 1, the U-Net network essentially adopts an encoder-decoder architecture. The left-hand side of the network progressively abstracts the input optical-field distribution, extracting deep-level features at the middle layer. Subsequently, through the decoding process on the right-hand side, it reconstructs an output optical-field distribution with the same size as the input. Considering that most statistical analyses of atmospheric turbulence predominantly rely on the intensity distribution, the optical-field distribution is replaced by the intensity distribution.

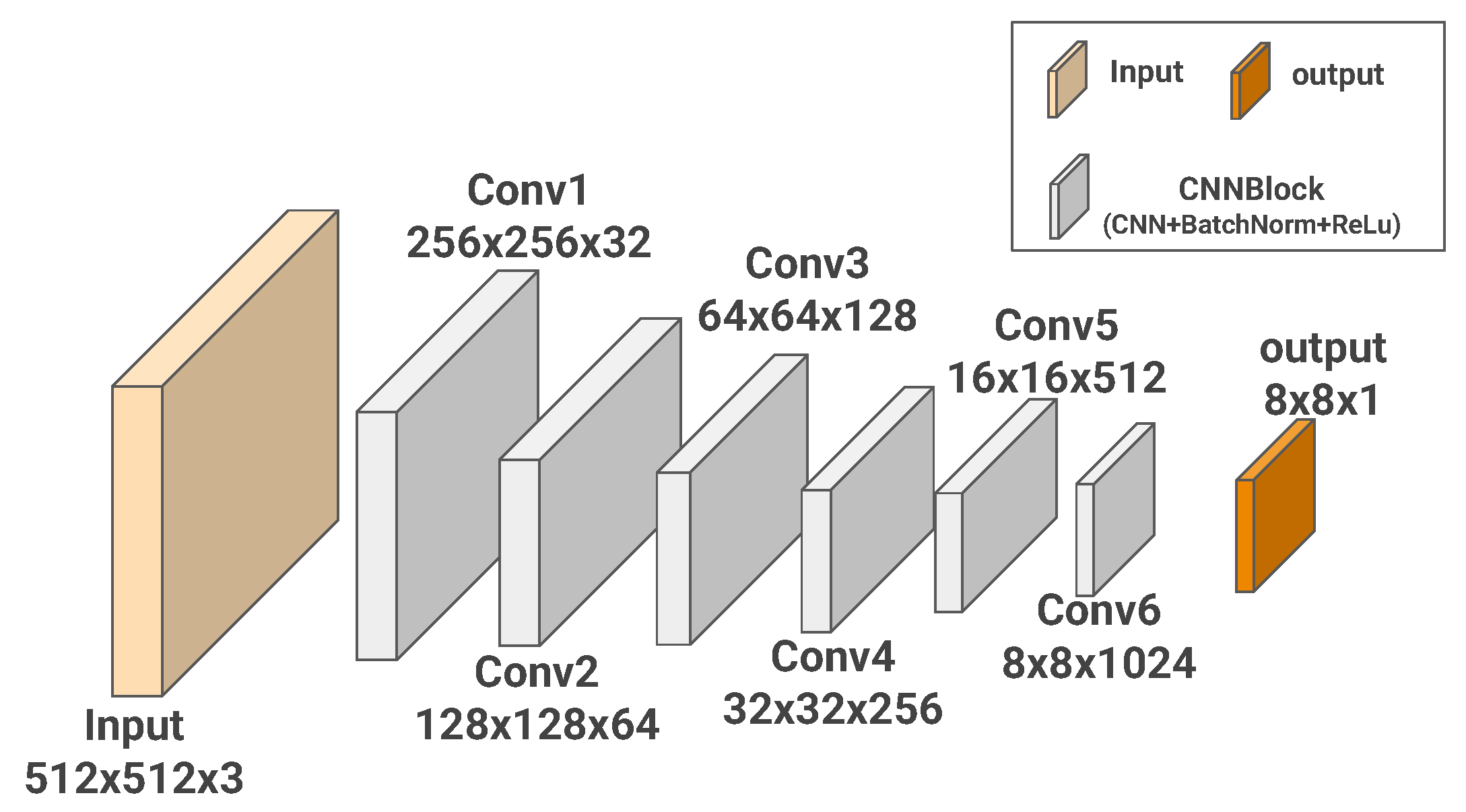

During the GAN training process, a discriminator is necessary to assess the quality of the generated samples. In this study, PatchGAN is used as a discriminator, as it has been proven effective in similar tasks according to previous research [

19,

24]. The architecture of the PatchGAN network is illustrated in

Figure 2.

3. Training Data and Network Training

The training sample was prepared via the numerical simulation method mentioned above. Based on the network architecture, the inputs for the U-Net network are defined as the initial optical field distribution (comprising the amplitude distribution and phase distribution) and the control condition parameters (including the refractive index structure constant and transmission distance).

The initial optical field distribution follows a fundamental mode Gaussian distribution. The initial phase distribution varies depending on the collimation and focusing state of the beam. To match the dimensionality of the middle layer of the U-Net network, the characteristic parameters of the intensity of the turbulence are expanded in dimension to form a characteristic layer (with a dimension of 16 × 16 × 2). Here, the third dimension represents different control condition parameters. Finally, this characteristic layer is concatenated with the feature layer along the third dimension.

As for the PatchGAN network, its inputs consist of the initial optical field distribution and the intensity distribution of the receiving plane. The intensity distribution output of the U-Net network is labeled as ’fake’, while the intensity distribution obtained through numerical simulation is labeled ’true’.

3.1. Building up the Training Dataset

The parameters of the training sample set are presented as follows:

The input optical field is a fundamental-mode Gaussian beam with a beam waist radius of 0.1 m and a wavelength of 1.08 m. This Gaussian beam can be in a collimated or focused state. In the focused state, the focal length is set equal to the corresponding transmission distance;

Regarding the turbulence-related parameters, the refractive index structure constant is linearly sampled 100 times from to . The outer scale parameter is 100 m, and the inner scale parameter is 0.01 m. The number of phase screens on the transmission path is set to 20;

For the receiving-plane and transmission parameters, the physical dimension of the receiving-plane is . The transmission distance ranges from 0 to 10000 m, with a linear separation of 200 m intervals.

The above-mentioned parameters are substituted into the numerical model based on the random phase screen method to calculate the intensity distribution of the receiving plane. Considering the stochasticity of the atmospheric turbulence, the calculations are repeated 400 times for each set of parameters, and the average result is used as the label data for the network.

Subsequently, a training data set consisting of 10,000 training samples is created. Each sample includes the source-plane optical field with a dimension of 512 × 512 × 2, the control-condition parameters of 16 × 16 × 2, and the label representing the intensity distribution with a dimension of 512 × 512.

3.2. Loss Function

To align the intensity distribution generated by the network with the results of numerical simulation, a loss term representing the statistical characteristics of the atmospheric turbulence effect is incorporated into the original loss function of the generator network. Given that the loss function should be as simple as possible to ensure the gradient stability during backpropagation, a first-order statistical moment, specifically the beam wander variance [

1], is introduced as an additional loss term. This additional loss term can be expressed by the following formula:

The total power of the beam in the receiving plane is the sum of the power weighted in the

x direction and

y direction respectively. When the two-dimensional intensity distribution is obtained, the beam wander variance can be obtained by numerical solution, and then the

loss of the beam wander variance can be introduced,

where in Eq. (9),

i and

j denote the sequence numbers of the computing grid in the

x and

y directions, respectively.

and

represent the grid sizes in the

x and

y directions, respectively. The input optical field is denoted as

A, and the generator network is represented by

G. Meanwhile,

B serves as the label corresponding to the intensity distribution generated by numerical simulation. Based on these defined parameters, the modified loss function is formulated as follows:

where

represents the adversarial loss calculated by the Binary Cross Entropy (BCE) loss function;

represents the pixel loss calculated by the

loss function. For the discriminator network, we use a BCE loss function corresponding to the adversarial loss. Subsequently, the Adam optimizer is employed with the first-order moment exponential decay rate

and the second-order moment exponential decay rate

. The hyperparameters

and

are set to 5 and 0.5, respectively, based on preliminary experiments to balance the influence of different loss components and optimize the model performance.

3.3. Training Method

To address the GAN’s training challenges, a two-step training method is employed to achieve network convergence gradually. In the first step, a total of 1500 training epochs are conducted. The generator network and the discriminator network are trained alternately at a ratio of 1:1, that is, the generator network is trained once and then the discriminator network is trained once. The labels for the discriminator network are set as follows: the real distribution is labeled as 1, and the fake distribution is labeled as 0. The learning rate of the optimizers for both the generator and discriminator networks is set to 0.001.

In the second step, another 1500 training rounds are carried out. First, the discriminator network is reset to its initial random state. Then, the generator network and the discriminator network are alternately trained at a ratio of 1:2, the discriminator network is trained twice for every one-time training of the generator network. The label setting for the discriminator network is reversed, the real distribution is labeled as 0, and the fake distribution is labeled as 1. The learning rate of the optimizer for the generator network and that for the discriminator network are both set to 0.0001. Throughout the two-step training process, the generator network remains unchanged and is continuously trained. The whole training process utilizes an NVIDIA A100 GPU and takes 4 days to complete.

4. Results

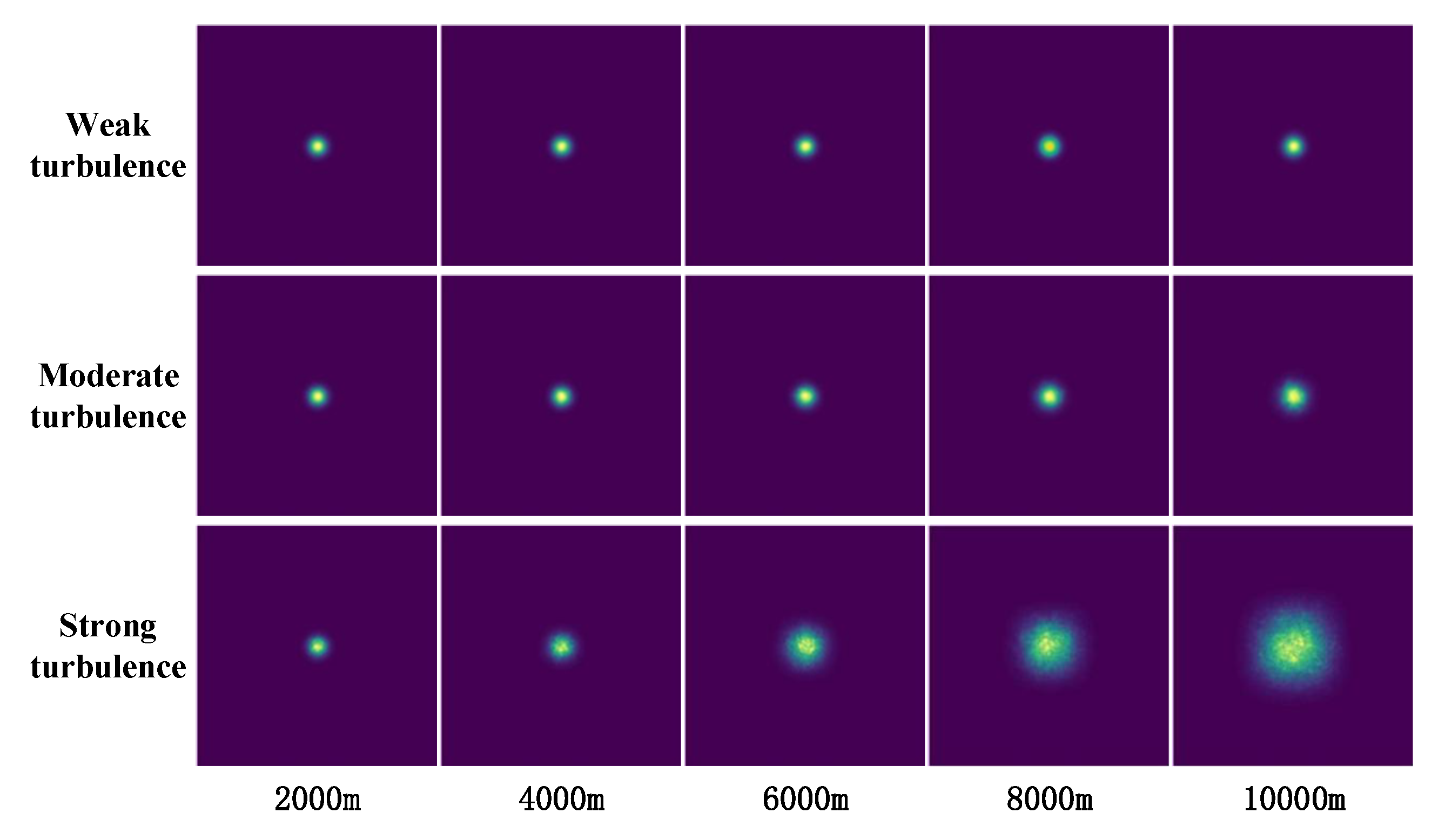

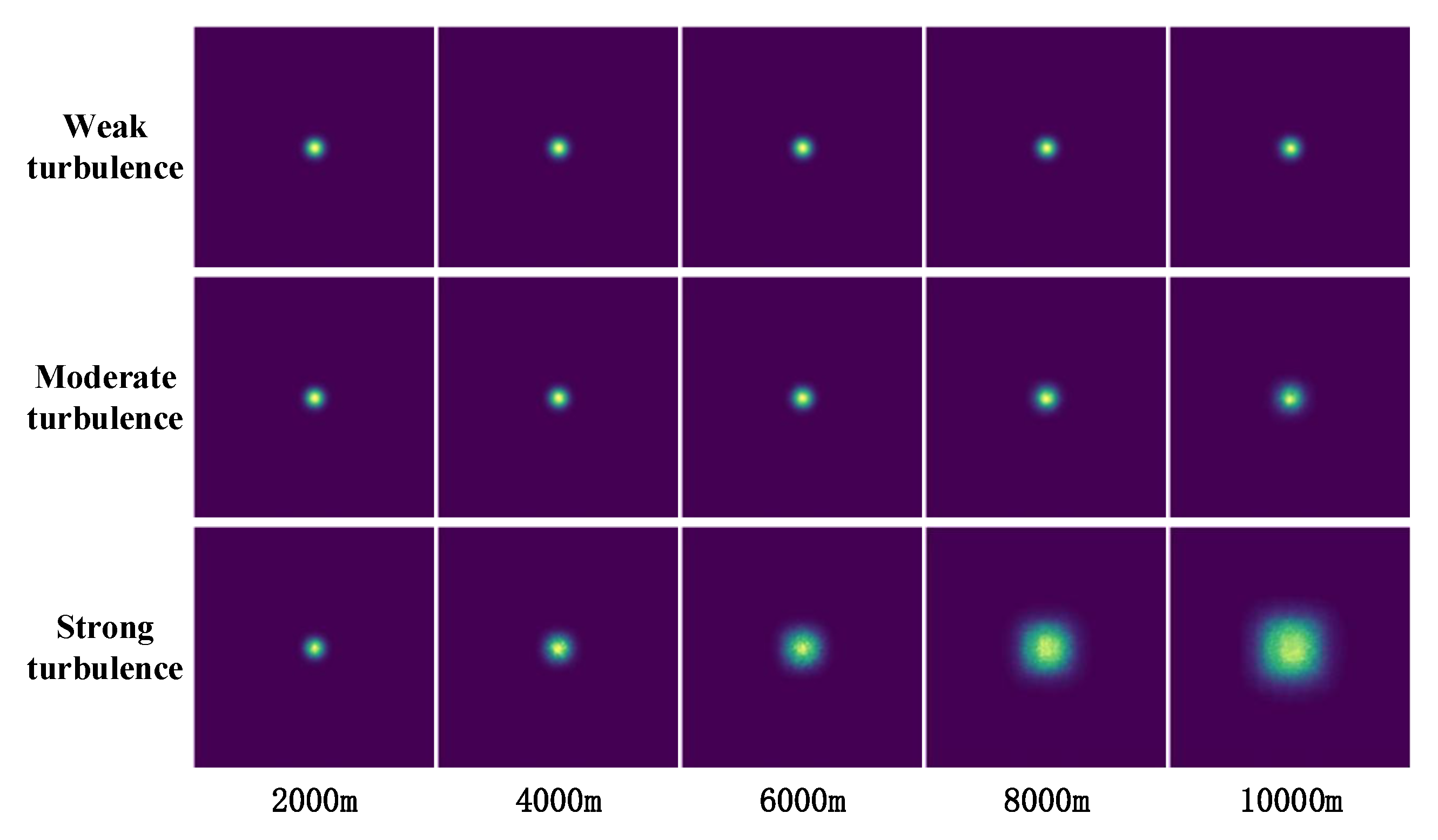

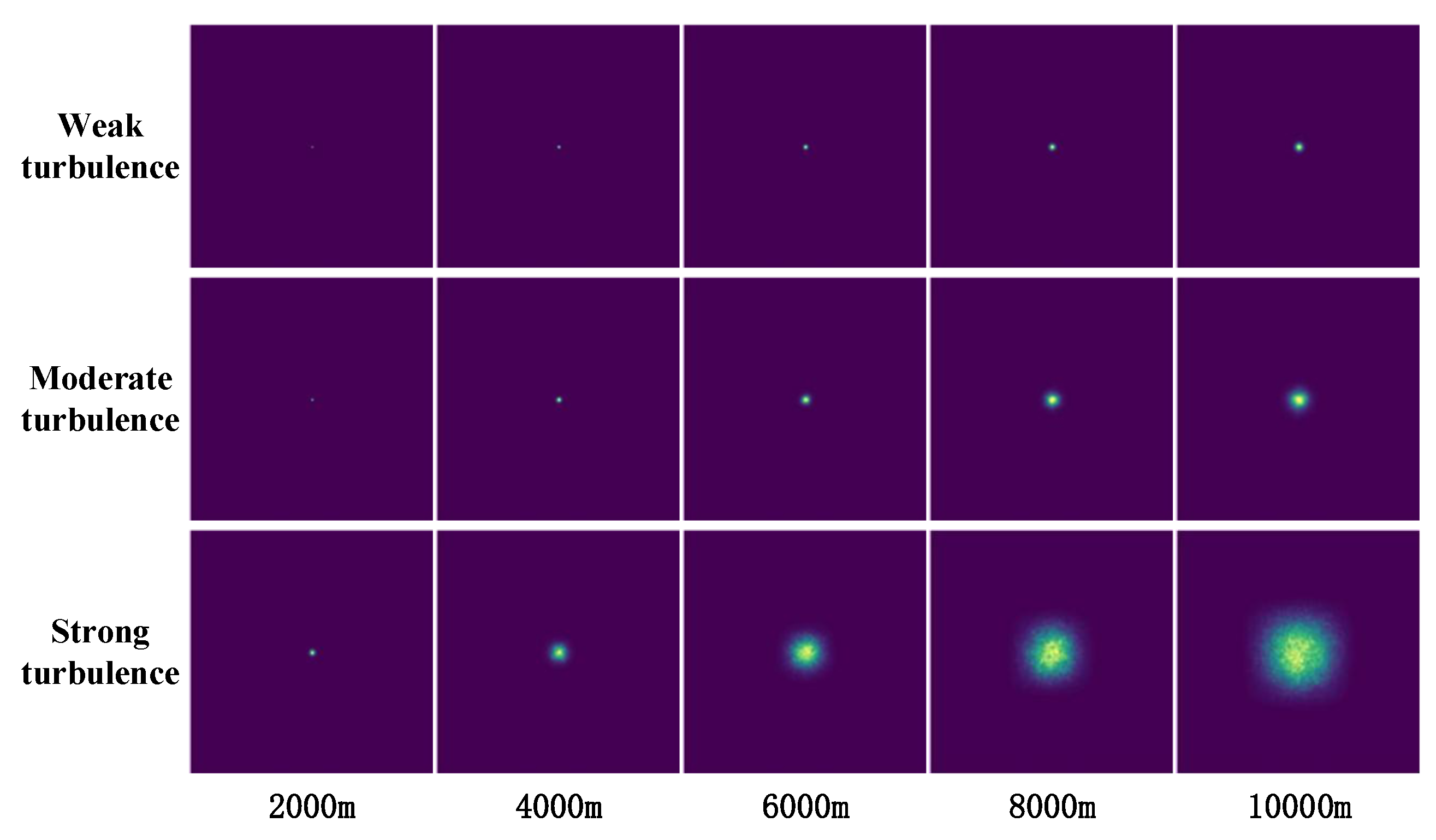

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the distorted intensity distribution of collimated Gaussian beams propagating through atmospheric turbulence, which are calculated by the generator network and numerical simulation respectively. In these figures, the refractive index structure constant takes values of

,

, and

, representing weak, moderate, and strong turbulence conditions, respectively. Meanwhile, the transmission distance is set to 2000 m, 4000 m, 6000 m, 8000 m, and 10000 m. From top to bottom, the rows in the figures represent different values of the refractive index structure constant, while from left to right, the columns correspond to different transmission distances.

The figures reveal that the intensity distribution of the laser beam predicted by the neural network aligns well with the outcomes of numerical simulations. Moreover, the radius of the laser beam exhibits an increasing trend with the growth of both transmission distance and turbulence intensity. This observation is in line with the theoretical understanding of laser beam propagation in turbulent media [

25]. It strongly suggests that the neural network has effectively captured the influence of turbulence on the propagation of the laser beam.

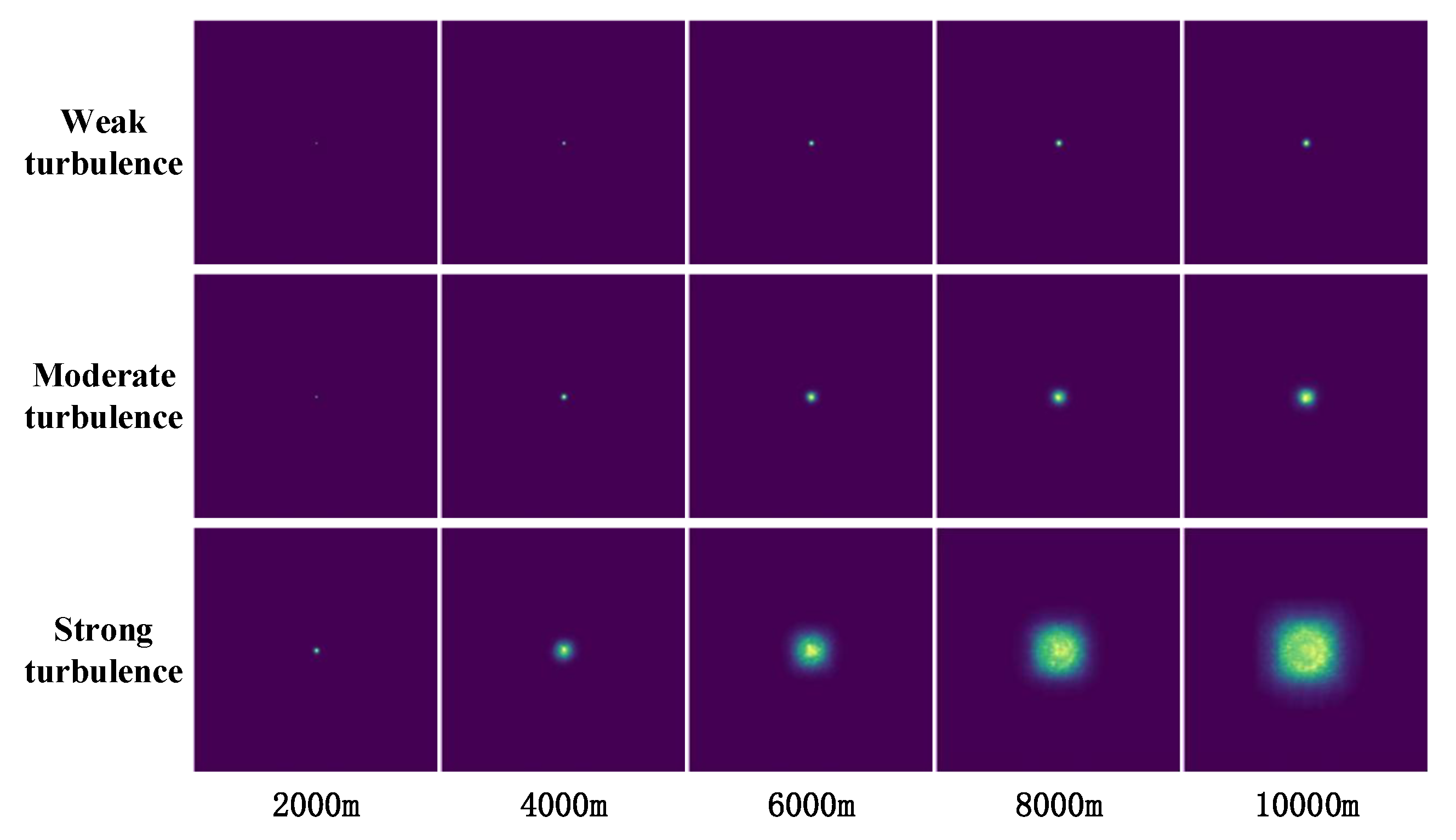

Similarly,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate the distorted intensity distribution of focused Gaussian beams propagating through atmospheric turbulence, which indicate a high degree of consistency between the predictions of the neural network and the outcomes of numerical simulations. In addition, from the patterns of intensity distribution shown in

Figure 6, it is clearly manifested that under weak-turbulence conditions, the focusing spot experiences negligible expansion. However, when a certain turbulence intensity is reached, the converging ability of the Gaussian beam is overshadowed by the expansion effects induced by turbulence, resulting in the formation of a significantly spread spot. This phenomenon is in line with the theory of laser beam propagation in atmospheric turbulence.

By replacing the numerical simulation approach with a neural network, we achieve a significant reduction in computation time, decreasing from 15 seconds to just 6 milliseconds—an impressive reduction of nearly four orders of magnitude. This substantial decrease in computational duration enables the proposed method to effectively meet the demands of applications requiring real-time performance.

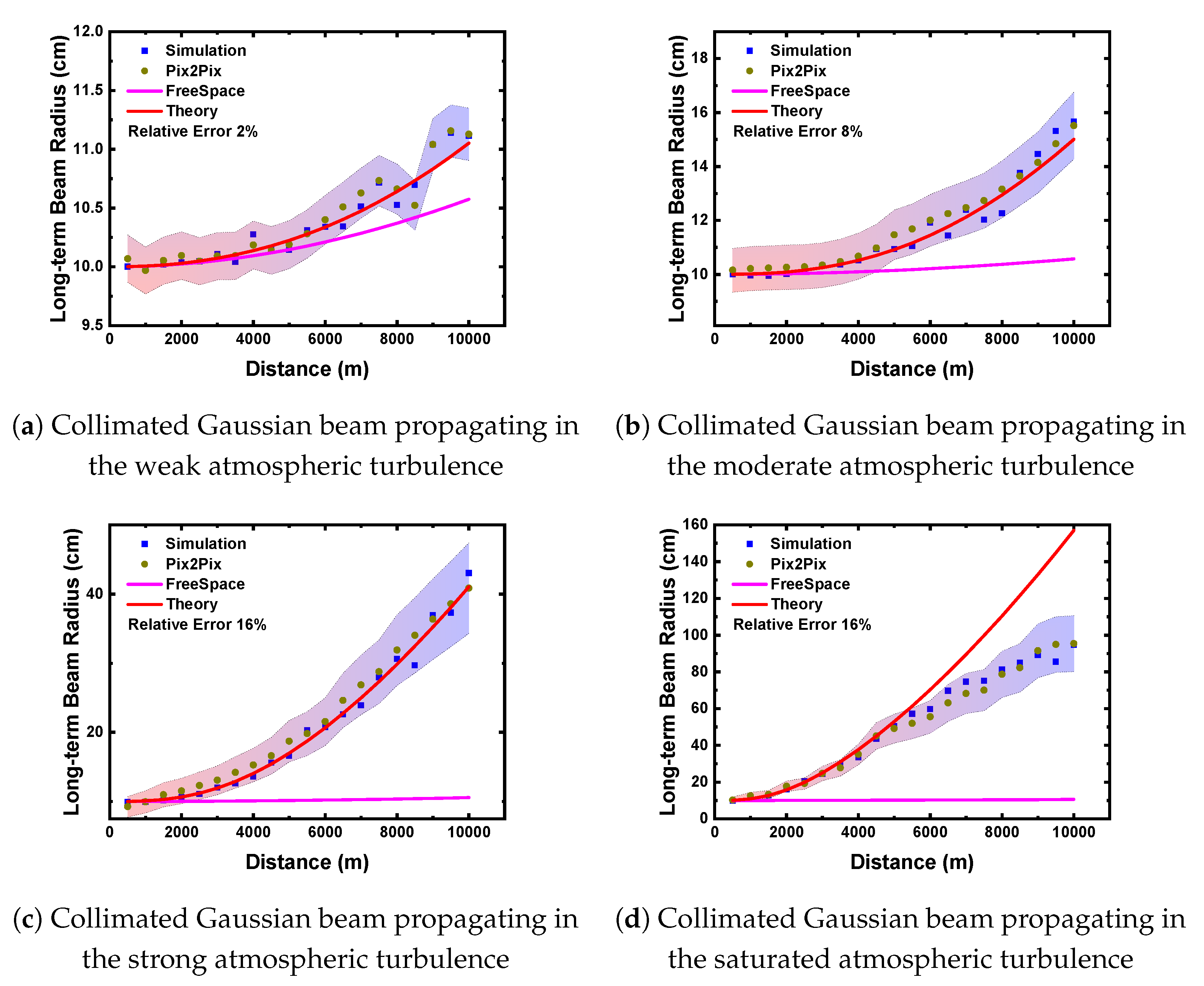

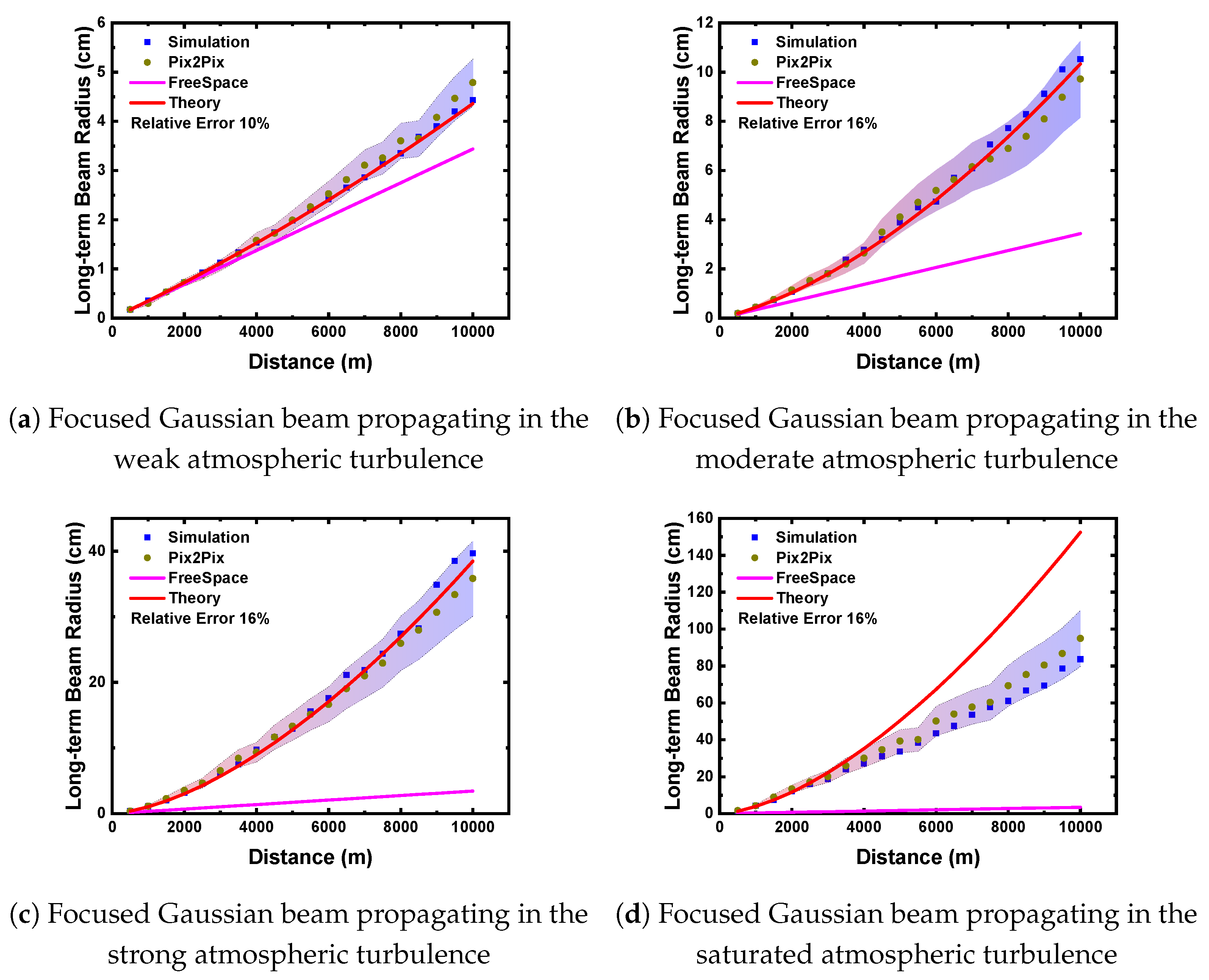

To further assess the prediction accuracy of the neural network, we utilized the second moment of the intensity distribution, namely the long-term beam radius, as an index for evaluation. A comparative analysis was conducted between the prediction results obtained from the neural network and those derived from numerical simulations, as illustrated in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

From the results of the long-term beam radius shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, after being trained on a large-scale training set, the neural network has the ability to simulate the laser beam propagation in the atmospheric turbulent medium, and the relative error under various turbulence intensities and transmission distances does not exceed 16%.

In the case of weak turbulence, both the numerical simulation results and the neural network prediction results exhibit violent oscillations around the theoretical curve, with the overall trend being notably non-smooth. This is because the collimated Gaussian beam in the case of weak turbulence is less affected by turbulence, and its long-term beam radius changes slowly with the increase of the transmission distance. Therefore, even some minor disturbances can cause the statistical results to be magnified in the figure. However, by observing the error magnitude, we can see that although the results seemingly oscillate violently around the theoretical curve, the relative error shows that all the fluctuations are within the error range of 2%, so the actual results are in good agreement with the theoretical curve and numerical simulation results.

Secondly, it is evident that the prediction accuracy of the neural network is higher under weak to moderate turbulence conditions compared to strong and saturated turbulence conditions. This disparity can be attributed to the fragmentation of the laser beam under strong or saturated turbulence, resulting in the formation of numerous small speckles within the two-dimensional intensity pattern. From the perspective of image processing, these speckles manifest as high-frequency signals. The CNN-based neural network encounters challenges in effectively extracting features associated with such high-frequency signals [

26], which imposes limitations on its prediction capabilities. Consequently, the error in the neural network’s predictions of intensity distribution is greater in strong and saturated turbulence conditions than in weak and moderate turbulence conditions.

Finally, in the context of saturated turbulence, substantial discrepancies are observed between both the numerical simulation outcomes and the neural network predictions when compared to theoretical expectations. Notably, once the transmission distance exceeds 5000 meters, the theoretical values are significantly elevated relative to those observed in previous cases. This phenomenon primarily arises from the absence of an effective theoretical framework that accurately characterizes the propagation of laser beams under saturated turbulence conditions. The theory employed in this study is primarily designed to address general turbulence scenarios. Thus, the general turbulence theory proves inadequate for accurately modeling such conditions.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, a simulation method for laser beam propagation in turbulent atmosphere based on GAN is proposed. Firstly, a generator based on the U-Net network and a discriminator based on the PatchGAN network are designed. In the construction of the generator, the refractive index structure constant and the transmission distance are introduced as control conditions into the bottleneck layer of the generator. Then, a two-step adversarial training strategy is utilized to complete the training of the generator network, enabling the simulation of Gaussian beams under different turbulence conditions and different transmission distances.

Compared with the traditional numerical method, the neural network method can increase the simulation speed by four orders of magnitude. Furthermore, under various turbulence conditions, the trends of how the second-order statistical moment of the predicted outcomes changes with distance align well with those derived from numerical simulations. Additionally, the relative error is maintained within 16%.

Finally, the differences in the prediction accuracy of the neural network under different turbulence intensities were analyzed. The results show that under weak and moderate turbulence conditions, the neural network prediction results exhibit high accuracy. However, under strong and saturated turbulence conditions, the prediction accuracy of the neural network decreases. This is because the fragmentation of the laser spot leads to the inability of the neural network to effectively capture a large number of high-frequency speckles. Given the complexity of atmospheric turbulence and its potential to introduce intricate patterns, it is important to consider the balance between robustness and accuracy in our models [

27,

28]. Future research will focus on addressing these challenges to improve prediction accuracy under varying turbulence conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Dongxiao Zhang and Junjie Zhang; Methodology, Dongxiao Zhang and Junjie Zhang; Project administration, Yinjun Gao and Taijiao Du; Software, Dongxiao Zhang and Junjie Zhang; Supervision, Junjie Zhang and Yinjun Gao; Validation, Taijiao Du; Writing – original draft, Dongxiao Zhang; Writing–review & editing, Junjie Zhang, Yinjun Gao and Taijiao Du..

Funding

The work is partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under the grant number 12105227 and 12405318.

References

- Andrews, L.C.; Phillips, R.L. Laser beam propagation through random media; SPIE press, 2005.

- Khare, K.; Lochab, P.; Senthilkumaran, P. Theory of wave propagation in a turbulent medium. In Orbital Angular Momentum States of Light; IOP Publishing, 2020; pp. 7–1 to 7–39. [CrossRef]

- Hulea, M.; Tang, X.; Ghassemlooy, Z.; Rajbhandari, S. A review on effects of the atmospheric turbulence on laser beam propagation — An analytic approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 10th International Symposium on Communication Systems, Networks and Digital Signal Processing (CSNDSP); 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, S.S.R. Laser beam propagation in atmospheric turbulence. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences 1979, 2, 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Salmanowitz, J.; Zandt, N.R.V. Phase Screen Generation for Non-Kolmogorov Turbulence. Imaging and Applied Optics Congress 2022 (3D, AOA, COSI, ISA, pcAOP), 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Frehlich, R. Simulation of laser propagation in a turbulent atmosphere. Applied Optics 2000, 39, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcglamery, B.L. Computer Simulation Studies Of Compensation Of Turbulence Degraded Images. Proceedings of SPIE - The International Society for Optical Engineering 1976, 74, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.; Wang, K.; Tang, X.; Wang, X. Investigation of Oceanic Turbulence Random Phase Screen Generation Methods for UWOC. Photonics 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Q.; Yang, L.; Gong, L.; Wang, L.G.; Wang, X. Waveform Distortion of Gaussian Beam in Atmospheric Turbulence Simulated by Phase Screen Method. Journal of Mathematics 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, B.J.; Strugala, L.A. Method for inclusion of low-frequency contributions in numerical representation of atmospheric turbulence. Proceedings of SPIE - The International Society for Optical Engineering 1990, 1221, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Charnotskii, M. Sparse spectrum model for a turbulent phase. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 2013, 30, 479. [Google Scholar]

- Charnotskii, M. Sparse spectrum model for the turbulent phase simulations. In Proceedings of the Atmospheric Propagation X; Thomas, L.M.W.; Spillar, E.J., Eds. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, 2013, Vol. 8732, p. 873208. [CrossRef]

- Paulson, D.A.; Wu, C.; Davis, C.C. Randomized Spectral Sampling for Efficient Simulation of Laser Propagation through Optical Turbulence. Journal of the Optical Society of America B 2019, 36, 3249–3262. [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos, M.; Luna, K. Sinc method for generating and extending phase screens of atmospheric turbulence. Journal of the Optical Society of America, A: Optics, Image Science and Vision 2024, 41, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, C.; Qin, M.; Wu, H. Accurate simulation of turbulent phase screen using optimization method. Optik 2019, 178, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, D.X.; Xiao, C.; Qin, M.Z. Precision analysis of turbulence phase screens and its influence on simulation of Gaussian-beam propagating in the turbulent atmosphere. Applied Optics 2020, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2014; pp. 2672–2680.19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2017, pp. 2223–2232.

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2023, pp. 10684–10695.

- Chunbo, M.A.; Ke, H.; Jun, A.O. Numerical Simulation of Random Phase Screen Under the Kolmogorov and Non-Kolmogorov Turbulence Model. Computer & Digital Engineering, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI). Springer; 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017, pp. 1125–1134.

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Lu, H.; Won, D.; Yoon, S.W. Medical Image Synthesis with Generative Adversarial Networks for Tissue Recognition. IEEE Computer Society 2018, 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.C.; Yang, P.L.; Zhao, H.C.; Wang, Z.B.; Wu, Y.; Fei, W. Simulation of Characteristics of Far Field Laser Beam Spot Under Different Atmospheric Transmission Conditions. MODERN APPLIED PHYSICS 2019, 10, 020301–1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.Q.J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y. Training Behavior of Deep Neural Network in Frequency Domain. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing; Gedeon, T.; Wong, K.W.; Lee, M., Eds., Cham; 2019; pp. 264–274. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.J.; Meng, D. Quantum-inspired analysis of neural network vulnerabilities: the role of conjugate variables in system attacks. National Science Review 2024, 11, nwae141, [https://academic.oup.com/nsr/articlepdf/11/9/nwae141/58810640/nwae141.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Meng, D.; et al. Exploring the uncertainty principle in neural networks through binary classification. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 28402, Received 24 July 2024; Accepted 05 November 2024; Published 18 November 2024,. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).