Submitted:

09 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Oxidative Stress

3. Electron Transport Chain

4. Oxidative Stress in Sickle Cell Disease

4.1. Environmental Factors

5. Murine Studies Linking Oxidative Stress to SCD Clinical Severity

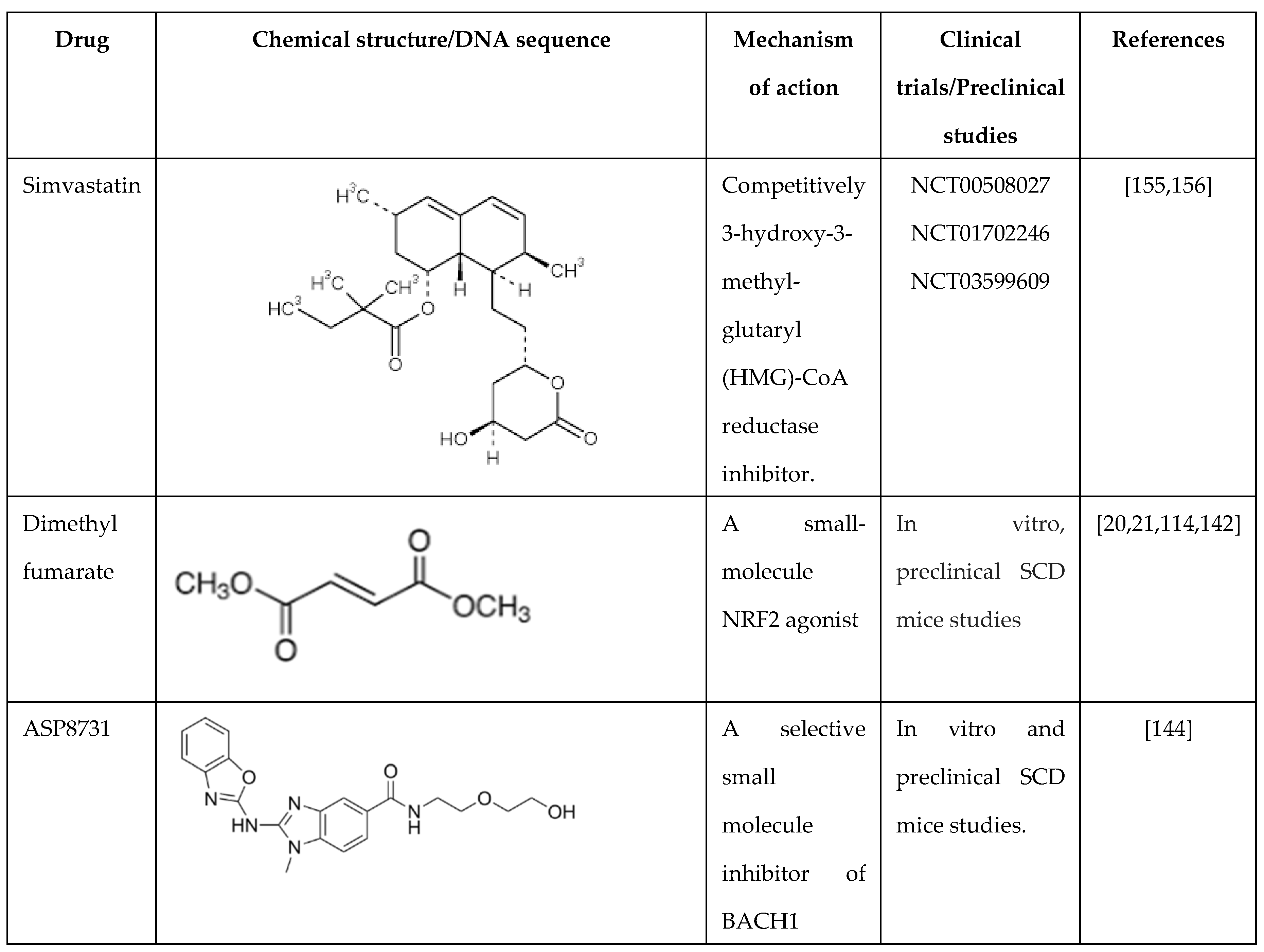

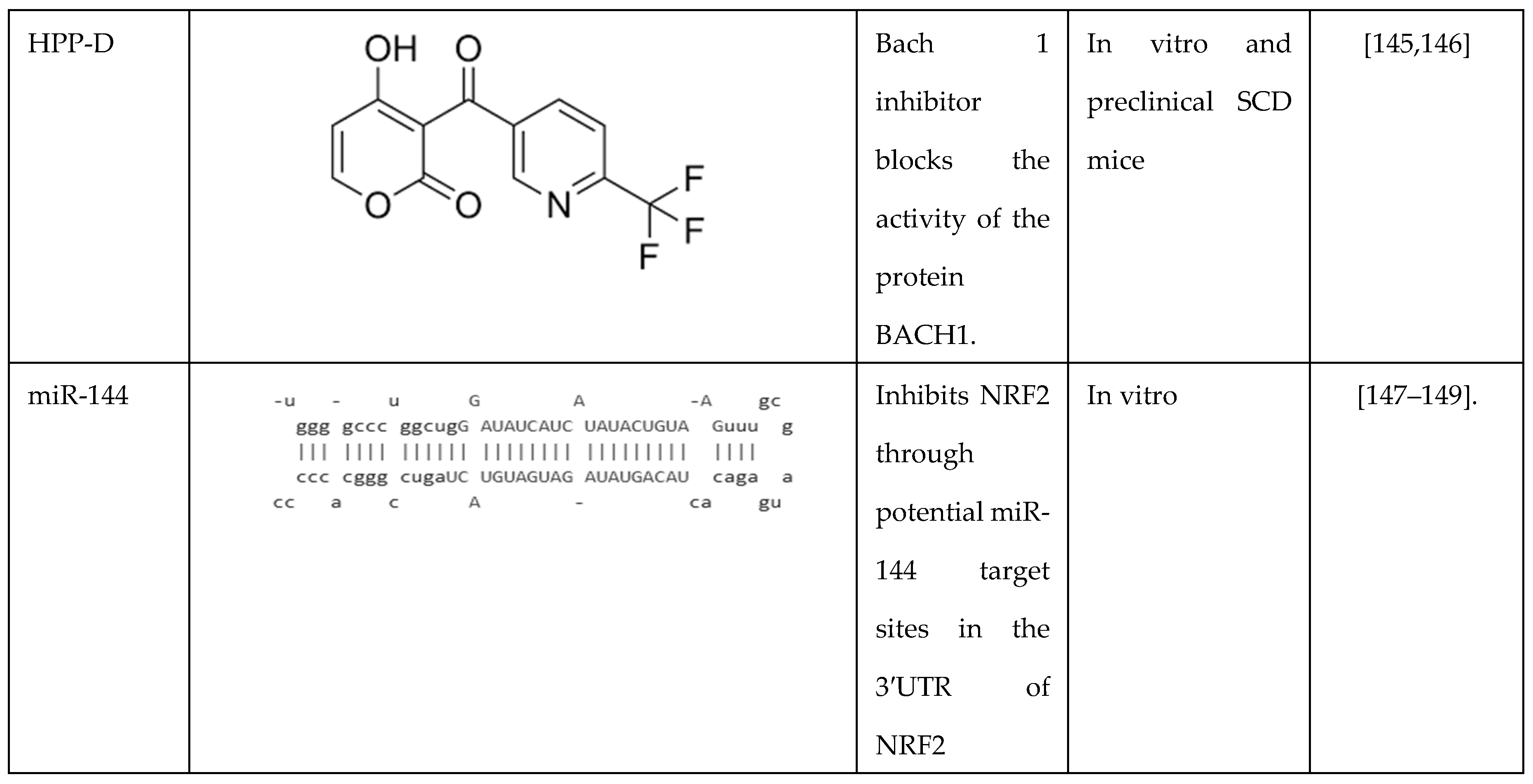

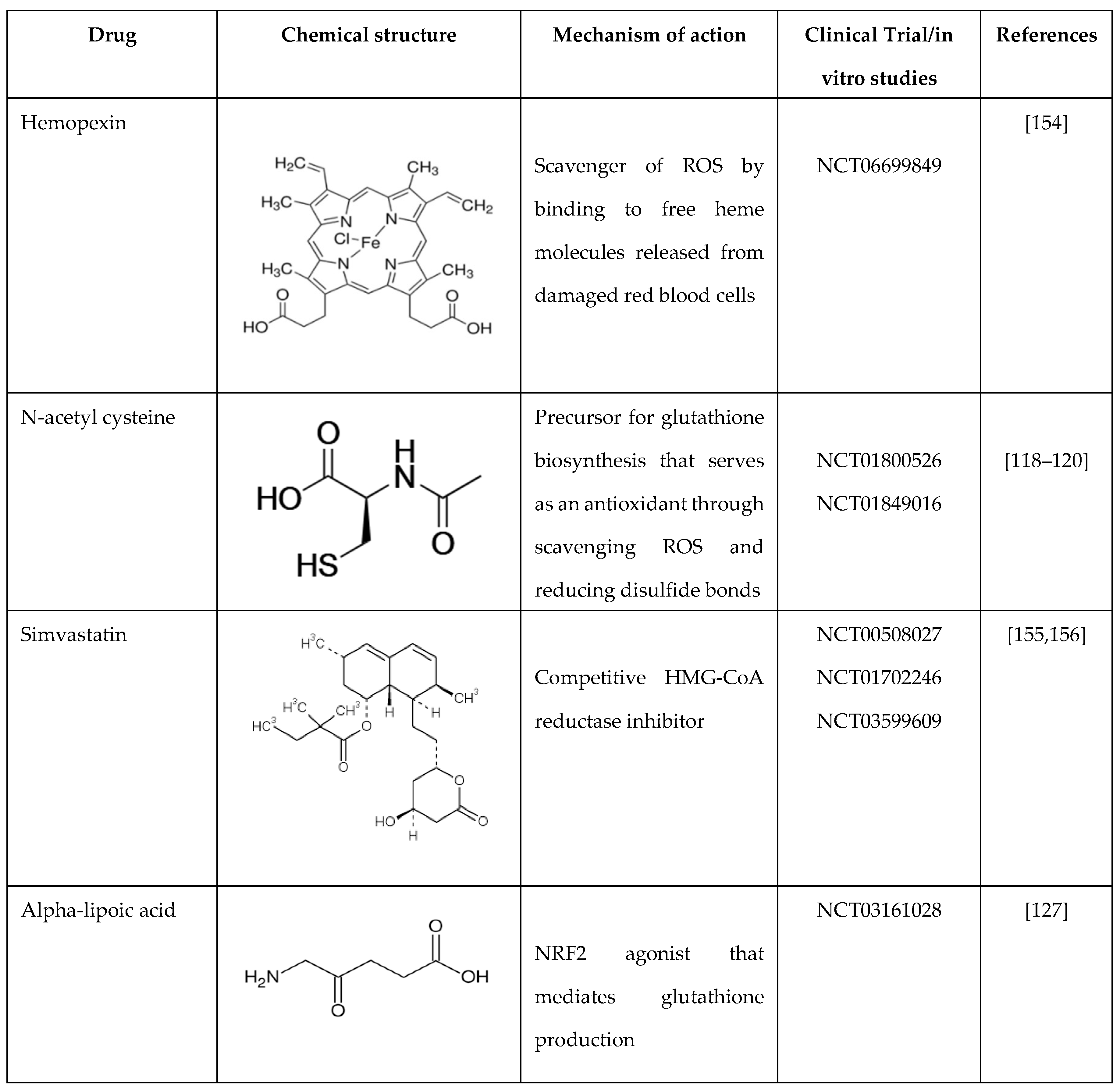

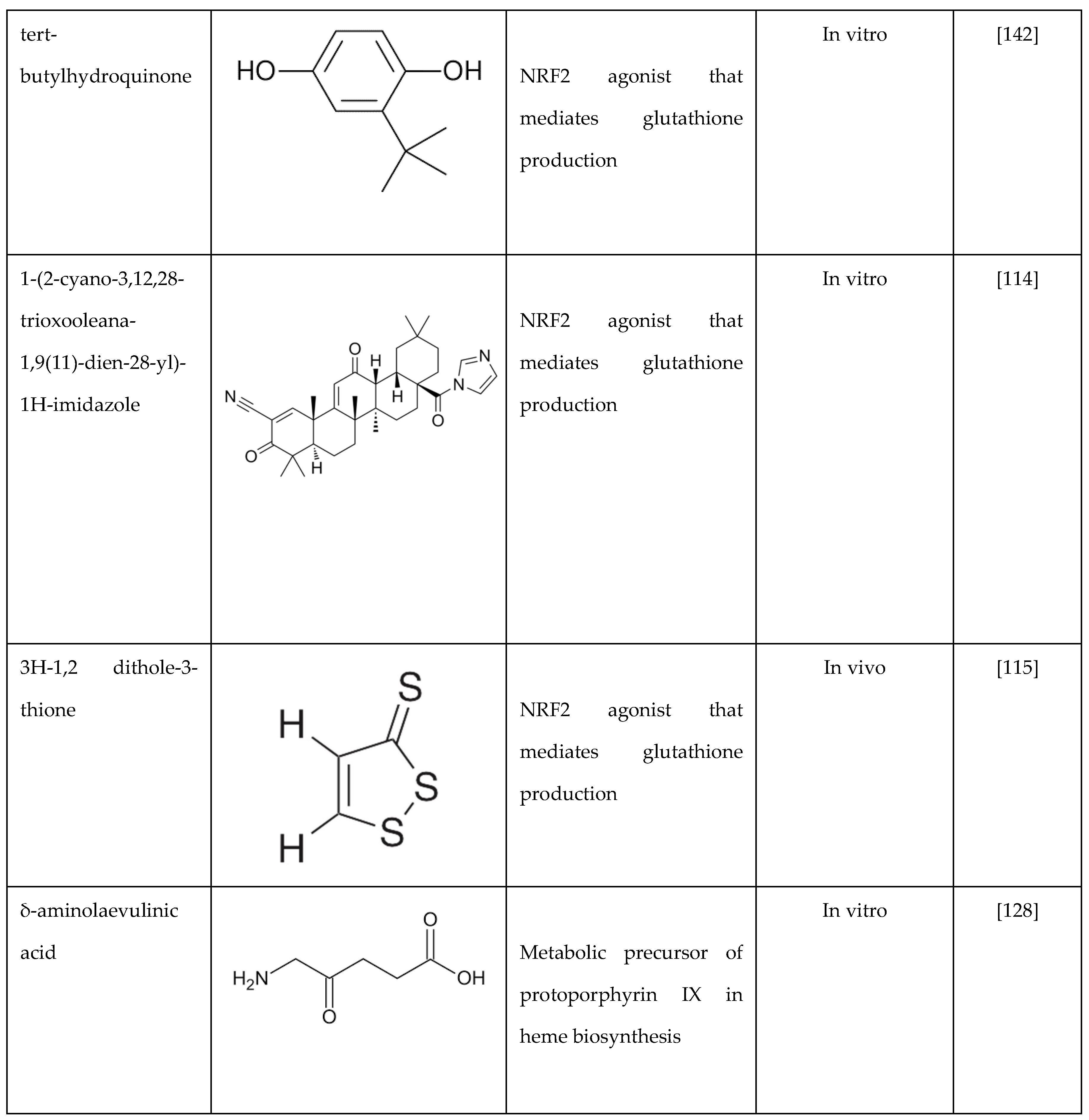

6. Targeted Therapy to Reduce Oxidative Stress in SCD

6.1. Hemopexin

6.2. Alpha-Lipoic Acid

6.3. δ-Aminolevulinate

6.4. Arginine

7. Role of NRF2 in Globin Gene Regulation

7.1. BACH 1 Inhibitors

7.2. Regulation by Microrna Genes

8. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Royal, C.D.M.; Babyak, M.; Shah, N.; Srivatsa, S.; Stewart, K.A.; Tanabe, P.; Wonkam, A.; Asnani, M. Sickle cell disease is a global prototype for integrative research and healthcare. Adv Genet (Hoboken) 2021, 2, e10037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vona, R.; Sposi, N.M.; Mattia, L.; Gambardella, L.; Straface, E.; Pietraforte, D. Sickle Cell Disease: Role of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Therapy. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, F.B.; Rees, D.C.; DeBaun, M.R.; Nnodu, O.; Ranque, B.; Thompson, A.A.; Ware, R.E.; Abboud, M.R.; Abraham, A.; Ambrose, E.E.; et al. Defining global strategies to improve outcomes in sickle cell disease: a Lancet Haematology Commission. Lancet Haematol 2023, 10, e633–e686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goia, F.; Tesi, U.; Gilardino, M.O.; Gasperini, S.; Carezzana, G. [Clinical evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy of cephalexin]. Minerva Stomatol 1986, 35, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stamatoyannopoulos, G. Human hemoglobin switching. Science 1991, 252, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrone, F.A.; Hofrichter, J.; Eaton, W.A. Kinetics of sickle hemoglobin polymerization. I. Studies using temperature-jump and laser photolysis techniques. J Mol Biol 1985, 183, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatoyannopoulos, G. The molecular basis of hemoglobin disease. Annu Rev Genet 1972, 6, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, C.C.; Thein, S.L. Sickle cell nephropathy - a practical approach. Br J Haematol 2011, 155, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, G.J.; Steinberg, M.H.; Gladwin, M.T. Intravascular hemolysis and the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potoka, K.P.; Gladwin, M.T. Vasculopathy and pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015, 308, L314–L324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, E.; Biemond, B.J.; Otten, H.M.; Brandjes, D.P.; Schnog, J.J.; Group, C.S. Oxidative stress in sickle cell disease; pathophysiology and potential implications for disease management. Am J Hematol 2011, 86, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumburu, L.; Ghosh-Choudhary, S.; Seifuddin, F.T.; Barbu, E.A.; Yang, S.; Ahmad, M.M.; Wilkins, L.H.W.; Tunc, I.; Sivakumar, I.; Nichols, J.S.; et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA is a proinflammatory DAMP in sickle cell disease. Blood 2021, 137, 3116–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagadeeswaran, R.; Vazquez, B.A.; Thiruppathi, M.; Ganesh, B.B.; Ibanez, V.; Cui, S.; Engel, J.D.; Diamond, A.M.; Molokie, R.E.; DeSimone, J.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of LSD1 and mTOR reduces mitochondrial retention and associated ROS levels in the red blood cells of sickle cell disease. Exp Hematol 2017, 50, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallivan, A.; Alejandro, M.; Kanu, A.; Zekaryas, N.; Horneman, H.; Hong, L.K.; Vinchinsky, E.; Lavelle, D.; Diamond, A.M.; Molokie, R.E.; et al. Reticulocyte mitochondrial retention increases reactive oxygen species and oxygen consumption in mouse models of sickle cell disease and phlebotomy-induced anemia. Exp Hematol 2023, 122, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hybertson, B.M.; Gao, B.; Bose, S.K.; McCord, J.M. Oxidative stress in health and disease: the therapeutic potential of Nrf2 activation. Mol Aspects Med 2011, 32, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Takahashi, J.; Yamamoto, M. Molecular Basis of the KEAP1-NRF2 Signaling Pathway. Mol Cells 2023, 46, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macari, E.R.; Schaeffer, E.K.; West, R.J.; Lowrey, C.H. Simvastatin and t-butylhydroquinone suppress KLF1 and BCL11A gene expression and additively increase fetal hemoglobin in primary human erythroid cells. Blood 2013, 121, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Oseghale, A.R.; Nicole, L.H.; Li, B.; Pace, B.S. Mechanisms of NRF2 activation to mediate fetal hemoglobin induction and protection against oxidative stress in sickle cell disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2019, 244, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Li, B.; Pace, B.S. NRF2 mediates gamma-globin gene regulation and fetal hemoglobin induction in human erythroid progenitors. Haematologica 2017, 102, e285–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Xi, C.; Ward, A.; Takezaki, M.; Shi, H.; Peterson, K.R.; Pace, B.S. NRF2 mediates gamma-globin gene regulation through epigenetic modifications in a beta-YAC transgenic mouse model. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2020, 245, 1308–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Pace, B.; Gupta, D.; Sturtevant, S.; Li, B.; Makala, L.; Brittain, J.; Moore, N.; Vieira, B.F.; Thullen, T.; et al. Dimethyl fumarate increases fetal hemoglobin, provides heme detoxification, and corrects anemia in sickle cell disease. JCI Insight 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, C.; Jacob, E.; Styles, L.; Kuypers, F.; Larkin, S.; Vichinsky, E. Simvastatin reduces vaso-occlusive pain in sickle cell anaemia: a pilot efficacy trial. Br J Haematol 2017, 177, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, C.; Palani, C.; Takezaki, M.; Shi, H.; Horuzsko, A.; Pace, B.S.; Zhu, X. Simvastatin-Mediated Nrf2 Activation Induces Fetal Hemoglobin and Antioxidant Enzyme Expression to Ameliorate the Phenotype of Sickle Cell Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.M.; Kasztan, M.; Sedaka, R.; Molina, P.A.; Dunaway, L.S.; Pollock, J.S.; Pollock, D.M. Hydroxyurea improves nitric oxide bioavailability in humanized sickle cell mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2021, 320, R630–R640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, S.B. Nitric oxide production from hydroxyurea. Free Radic Biol Med 2004, 37, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshilolo, L.; Tomlinson, G.; Williams, T.N.; Santos, B.; Olupot-Olupot, P.; Lane, A.; Aygun, B.; Stuber, S.E.; Latham, T.S.; McGann, P.T.; et al. Hydroxyurea for Children with Sickle Cell Anemia in Sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, C.C.; Opoka, R.O.; Latham, T.S.; Hume, H.A.; Nabaggala, C.; Kasirye, P.; Ndugwa, C.M.; Lane, A.; Ware, R.E. Hydroxyurea Dose Escalation for Sickle Cell Anemia in Sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 2524–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niihara, Y.; Miller, S.T.; Kanter, J.; Lanzkron, S.; Smith, W.R.; Hsu, L.L.; Gordeuk, V.R.; Viswanathan, K.; Sarnaik, S.; Osunkwo, I.; et al. A Phase 3 Trial of l-Glutamine in Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataga, K.I.; Kutlar, A.; Kanter, J.; Liles, D.; Cancado, R.; Friedrisch, J.; Guthrie, T.H.; Knight-Madden, J.; Alvarez, O.A.; Gordeuk, V.R.; et al. Crizanlizumab for the Prevention of Pain Crises in Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 2017, 376, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migotsky, M.; Beestrum, M.; Badawy, S.M. Recent Advances in Sickle-Cell Disease Therapies: A Review of Voxelotor, Crizanlizumab, and L-glutamine. Pharmacy (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichinsky, E.; Hoppe, C.C.; Ataga, K.I.; Ware, R.E.; Nduba, V.; El-Beshlawy, A.; Hassab, H.; Achebe, M.M.; Alkindi, S.; Brown, R.C.; et al. A Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Voxelotor in Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangoul, H.; Locatelli, F.; Sharma, A.; Bhatia, M.; Mapara, M.; Molinari, L.; Wall, D.; Liem, R.I.; Telfer, P.; Shah, A.J.; et al. Exagamglogene Autotemcel for Severe Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 2024, 390, 1649–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippidis, A. CASGEVY Makes History as FDA Approves First CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Edited Therapy. Hum Gene Ther 2024, 35, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanter, J.; Walters, M.C.; Krishnamurti, L.; Mapara, M.Y.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Rifkin-Zenenberg, S.; Aygun, B.; Kasow, K.A.; Pierciey, F.J., Jr.; Bonner, M.; et al. Biologic and Clinical Efficacy of LentiGlobin for Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herring, W.L.; Gallagher, M.E.; Shah, N.; Morse, K.C.; Mladsi, D.; Dong, O.M.; Chawla, A.; Leiding, J.W.; Zhang, L.; Paramore, C.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Lovotibeglogene Autotemcel (Lovo-Cel) Gene Therapy for Patients with Sickle Cell Disease and Recurrent Vaso-Occlusive Events in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics 2024, 42, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Zucca, P.; Varoni, E.M.; Dini, L.; Panzarini, E.; Rajkovic, J.; Tsouh Fokou, P.V.; Azzini, E.; Peluso, I.; et al. Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Mitra, S.; Crowe, S.E. Oxidative stress: an essential factor in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Physiol Rev 2014, 94, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T.; Holbrook, N.J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of aging. Nature 2000, 408, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med 2010, 49, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghi Aminjan, H.; Abtahi, S.R.; Hazrati, E.; Chamanara, M.; Jalili, M.; Paknejad, B. Targeting of oxidative stress and inflammation through ROS/NF-kappaB pathway in phosphine-induced hepatotoxicity mitigation. Life Sci 2019, 232, 116607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veith, A.; Moorthy, B. Role of Cytochrome P450s in the Generation and Metabolism of Reactive Oxygen Species. Curr Opin Toxicol 2018, 7, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stading, R.; Chu, C.; Couroucli, X.; Lingappan, K.; Moorthy, B. Molecular role of cytochrome P4501A enzymes inoxidative stress. Curr Opin Toxicol 2020, 20-21, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermot, A.; Petit-Hartlein, I.; Smith, S.M.E.; Fieschi, F. NADPH Oxidases (NOX): An Overview from Discovery, Molecular Mechanisms to Physiology and Pathology. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu-Medellin, N.; Kelley, E.E. Xanthine oxidoreductase-catalyzed reactive species generation: A process in critical need of reevaluation. Redox Biol 2013, 1, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.; Garcia, T.; Aniqa, M.; Ali, S.; Ally, A.; Nauli, S.M. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) and the Cardiovascular System: in Physiology and in Disease States. Am J Biomed Sci Res 2022, 15, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int J Mol Med 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, K.T.; Chang, H.C.; Ardehali, H. Role of heme in cardiovascular physiology and disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2015, 4, e001138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 20, 1126–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boveris, A.; Chance, B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J 1973, 134, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolfi-Donegan, D.; Braganza, A.; Shiva, S. Mitochondrial electron transport chain: Oxidative phosphorylation, oxidant production, and methods of measurement. Redox Biol 2020, 37, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Tu, B.P. Acetyl-CoA and the regulation of metabolism: mechanisms and consequences. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2015, 33, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.K.; Lu, J.; Bai, Y. Mitochondrial respiratory complex I: structure, function and implication in human diseases. Curr Med Chem 2009, 16, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliati, S.; Lorenzi, I.; Rigoni, G.; Caicci, F.; Soriano, M.E. Regulation of Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Assembly. J Mol Biol 2018, 430, 4849–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindoli, A.; Rigobello, M.P. Principles in redox signaling: from chemistry to functional significance. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 18, 1557–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Zou, L.; Zhang, X.; Branco, V.; Wang, J.; Carvalho, C.; Holmgren, A.; Lu, J. Redox Signaling Mediated by Thioredoxin and Glutathione Systems in the Central Nervous System. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017, 27, 989–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uttara, B.; Singh, A.V.; Zamboni, P.; Mahajan, R.T. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr Neuropharmacol 2009, 7, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.R.; Lyon, C.J.; Xia, X.; Liu, J.Z.; Tangirala, R.K.; Yin, F.; Boyadjian, R.; Bikineyeva, A.; Pratico, D.; Harrison, D.G.; et al. Age-accelerated atherosclerosis correlates with failure to upregulate antioxidant genes. Circ Res 2009, 104, e42–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, Z. Therapeutic potentials of catalase: Mechanisms, applications, and future perspectives. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2024, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Brigelius-Flohe, R.; Maiorino, M. Glutathione peroxidases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1830, 3289–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubos, E.; Loscalzo, J.; Handy, D.E. Glutathione peroxidase-1 in health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011, 15, 1957–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebbel, R.P.; Morgan, W.T.; Eaton, J.W.; Hedlund, B.E. Accelerated autoxidation and heme loss due to instability of sickle hemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988, 85, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Pushkaran, S.; Konstantinidis, D.G.; Koochaki, S.; Malik, P.; Mohandas, N.; Zheng, Y.; Joiner, C.H.; Kalfa, T.A. Erythrocyte NADPH oxidase activity modulated by Rac GTPases, PKC, and plasma cytokines contributes to oxidative stress in sickle cell disease. Blood 2013, 121, 2099–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinney, A.; Woska, E.; Spasojevic, I.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Zennadi, R. Disrupting the vicious cycle created by NOX activation in sickle erythrocytes exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation prevents adhesion and vasoocclusion. Redox Biol 2019, 25, 101097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zennadi, R. The Role of RBC Oxidative Stress in Sickle Cell Disease: From the Molecular Basis to Pathologic Implications. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Franceschi, L.; Bertoldi, M.; Matte, A.; Santos Franco, S.; Pantaleo, A.; Ferru, E.; Turrini, F. Oxidative stress and beta-thalassemic erythroid cells behind the molecular defect. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013, 2013, 985210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boasiako, C.; Dankwah, G.B.; Aryee, R.; Hayfron-Benjamin, C.; Donkor, E.S.; Campbell, A.D. Oxidative Profile of Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Med Sci (Basel) 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.M.; Liu, M.; Sturdy, M.; Gao, G.; Varghese, S.T.; Sovari, A.A.; Dudley, S.C., Jr. Metabolic stress, reactive oxygen species, and arrhythmia. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2012, 52, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Sachdev, V.; Jison, M.L.; Shizukuda, Y.; Plehn, J.F.; Minter, K.; Brown, B.; Coles, W.A.; Nichols, J.S.; Ernst, I.; et al. Pulmonary hypertension is a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Vichinsky, E. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 2008, 359, 2254–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, C.D.; Wang, X.; Tanus-Santos, J.E.; Hogg, N.; Cannon, R.O., 3rd; Schechter, A.N.; Gladwin, M.T. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat Med 2002, 8, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, G.T.; Green, E.R.; Mecsas, J. Neutrophils to the ROScue: Mechanisms of NADPH Oxidase Activation and Bacterial Resistance. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conran, N.; Belcher, J.D. Inflammation in sickle cell disease. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2018, 68, 263–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhol, N.K.; Bhanjadeo, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Dash, U.C.; Ojha, R.R.; Majhi, S.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. The interplay between cytokines, inflammation, and antioxidants: mechanistic insights and therapeutic potentials of various antioxidants and anti-cytokine compounds. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 178, 117177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, S.; Jang, Y.M.; Smith, A.; Hagen, T.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Age-associated increases in oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activities in cardiac interfibrillar mitochondria: implications for the mitochondrial theory of aging. FASEB J 2005, 19, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.S.; Hamali, H.A.; Rashid, H.; Dobie, G.; Madkhali, A.M.; Mobarki, A.A.; Oldenburg, J.; Biswas, A. Mitochondria: Emerging Consequential in Sickle Cell Disease. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.C.; Gladwin, M.T.; Straub, A.C. Sickle cell disease: at the crossroads of pulmonary hypertension and diastolic heart failure. Heart 2020, 106, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, S.M.; De Moraes, J.A.; Bonnin, P.; Abbyad, P.; Le Jeune, S.; Lionnet, F.; Loufrani, L.; Grimaud, L.; Lambry, J.C.; Charue, D.; et al. Circulating cell membrane microparticles transfer heme to endothelial cells and trigger vasoocclusions in sickle cell disease. Blood 2015, 125, 3805–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbotosho, O.T.; Kapetanaki, M.G.; Kato, G.J. The Worst Things in Life are Free: The Role of Free Heme in Sickle Cell Disease. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 561917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, J.D.; Chen, C.; Nguyen, J.; Zhang, P.; Abdulla, F.; Nguyen, P.; Killeen, T.; Xu, P.; O’Sullivan, G.; Nath, K.A.; et al. Control of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Sickle Cell Disease with the Nrf2 Activator Dimethyl Fumarate. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017, 26, 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brousse, V.; Buffet, P.; Rees, D. The spleen and sickle cell disease: the sick(led) spleen. Br J Haematol 2014, 166, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzi, M.; Fuligni, F.; Santoro, L.; Sabattini, E.; Ichino, M.; De Vito, R.; Zucchetta, P.; Colombatti, R.; Sainati, L.; Gamba, P.; et al. Spleen histology in children with sickle cell disease and hereditary spherocytosis: hints on the disease pathophysiology. Hum Pathol 2017, 60, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Khaled, M.; Ouederni, M.; Mankai, Y.; Rekaya, S.; Ben Fraj, I.; Dhouib, N.; Kouki, R.; Mellouli, F.; Bejaoui, M. Prevalence and predictive factors of splenic sequestration crisis among 423 pediatric patients with sickle cell disease in Tunisia. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2020, 80, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rimawi, H.S.; Abdul-Qader, M.; Jallad, M.F.; Amarin, Z.O. Acute splenic sequestration in female children with sickle cell disease in the North of Jordan. J Trop Pediatr 2006, 52, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, R.; Bandyopadhyay, S.K.; Dutta, A. Sickle cell hepatopathy. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2008, 51, 284–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Owen, C.; Chopra, S. Sickle cell hepatopathy. Hepatology 2001, 33, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbari, D.S.; Kple-Faget, P.; Kwagyan, J.; Rana, S.; Gordeuk, V.R.; Castro, O. Circumstances of death in adult sickle cell disease patients. Am J Hematol 2006, 81, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamideh, D.; Alvarez, O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 1482–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacaille, F.; Allali, S.; de Montalembert, M. The Liver in Sickle Cell Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2021, 72, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badria, F.A.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Badria, A.F.; Elmarakby, A.A. Curcumin Attenuates Iron Accumulation and Oxidative Stress in the Liver and Spleen of Chronic Iron-Overloaded Rats. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0134156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Weihrauch, D.; Jones, D.W.; Jing, X.; Shi, Y.; Gourlay, D.; Oldham, K.T.; Hillery, C.A.; Pritchard, K.A., Jr. Inhibition of myeloperoxidase decreases vascular oxidative stress and increases vasodilatation in sickle cell disease mice. J Lipid Res 2013, 54, 3009–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.T.; Fasano, R.M. Management of Patients with Sickle Cell Disease Using Transfusion Therapy: Guidelines and Complications. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2016, 30, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, G.J.; Hebbel, R.P.; Steinberg, M.H.; Gladwin, M.T. Vasculopathy in sickle cell disease: Biology, pathophysiology, genetics, translational medicine, and new research directions. Am J Hematol 2009, 84, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, B.K.; Rodger, D.C. Sickle cell disease and the eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2017, 28, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetsch, J.W.; Park, T.S.; Dugan, L.L.; Shah, A.R.; Gidday, J.M. Xanthine oxidase-derived superoxide causes reoxygenation injury of ischemic cerebral endothelial cells. Brain Res 1998, 786, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, I.; Wattiaux, R.; Wattiaux-De Coninck, S. Deleterious effects of xanthine oxidase on rat liver endothelial cells after ischemia/reperfusion. Biochim Biophys Acta 1995, 1269, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solovey, A.; Gui, L.; Key, N.S.; Hebbel, R.P. Tissue factor expression by endothelial cells in sickle cell anemia. J Clin Invest 1998, 101, 1899–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Promsote, W.; Powell, F.L.; Veean, S.; Thounaojam, M.; Markand, S.; Saul, A.; Gutsaeva, D.; Bartoli, M.; Smith, S.B.; Ganapathy, V.; et al. Oral Monomethyl Fumarate Therapy Ameliorates Retinopathy in a Humanized Mouse Model of Sickle Cell Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016, 25, 921–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, R.J.; Jennette, J.C. Sickle cell nephropathy. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp 1994, 23, 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Saborio, P.; Scheinman, J.I. Sickle cell nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999, 10, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, P.T.; Pham, P.C.; Wilkinson, A.H.; Lew, S.Q. Renal abnormalities in sickle cell disease. Kidney Int 2000, 57, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebbel, R.P. The sickle erythrocyte in double jeopardy: autoxidation and iron decompartmentalization. Semin Hematol 1990, 27, 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, K.A.; Grande, J.P.; Haggard, J.J.; Croatt, A.J.; Katusic, Z.S.; Solovey, A.; Hebbel, R.P. Oxidative stress and induction of heme oxygenase-1 in the kidney in sickle cell disease. Am J Pathol 2001, 158, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daenen, K.; Andries, A.; Mekahli, D.; Van Schepdael, A.; Jouret, F.; Bammens, B. Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 2019, 34, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncos, J.P.; Grande, J.P.; Croatt, A.J.; Hebbel, R.P.; Vercellotti, G.M.; Katusic, Z.S.; Nath, K.A. Early and prominent alterations in hemodynamics, signaling, and gene expression following renal ischemia in sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2010, 298, F892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Liu, T.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, L.; Mao, H.; Ma, F.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L.; Zhan, Y. Oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetic nephropathy: role of polyphenols. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1185317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedeke, L.; Fernandez-Hernando, C. Regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012, 69, 915–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istvan, E.S.; Deisenhofer, J. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. Science 2001, 292, 1160–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.J.; Hong, E.M.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, J.; Park, S.W.; Byun, H.W.; Koh, D.H.; Choi, M.H.; Kae, S.H.; et al. Simvastatin induces heme oxygenase-1 via NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) activation through ERK and PI3K/Akt pathway in colon cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 46219–46229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Feng, Y.; Cui, R.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C. Simvastatin protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 98, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, K.A.; Ou, J.; Ou, Z.; Shi, Y.; Franciosi, J.P.; Signorino, P.; Kaul, S.; Ackland-Berglund, C.; Witte, K.; Holzhauer, S.; et al. Hypoxia-induced acute lung injury in murine models of sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004, 286, L705–L714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xi, C.; Thomas, B.; Pace, B.S. Loss of NRF2 function exacerbates the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease in a transgenic mouse model. Blood 2018, 131, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleku-Lukwete, N.; Suzuki, M.; Otsuki, A.; Tsuchida, K.; Katayama, S.; Hayashi, M.; Naganuma, E.; Moriguchi, T.; Tanabe, O.; Engel, J.D.; et al. Amelioration of inflammation and tissue damage in sickle cell model mice by Nrf2 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 12169–12174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Hazra, R.; Ihunnah, C.A.; Weidert, F.; Flage, B.; Ofori-Acquah, S.F. Augmented NRF2 activation protects adult sickle mice from lethal acute chest syndrome. Br J Haematol 2018, 182, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musicki, B.; Liu, T.; Sezen, S.F.; Burnett, A.L. Targeting NADPH oxidase decreases oxidative stress in the transgenic sickle cell mouse penis. J Sex Med 2012, 9, 1980–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Paul, J.; Wang, Y.; Gupta, M.; Vang, D.; Thompson, S.; Jha, R.; Nguyen, J.; Valverde, Y.; Lamarre, Y.; et al. Heme Causes Pain in Sickle Mice via Toll-Like Receptor 4-Mediated Reactive Oxygen Species- and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Glial Activation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2021, 34, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, B.S.; Shartava, A.; Pack-Mabien, A.; Mulekar, M.; Ardia, A.; Goodman, S.R. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on dense cell formation in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2003, 73, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nur, E.; Brandjes, D.P.; Teerlink, T.; Otten, H.M.; Oude Elferink, R.P.; Muskiet, F.; Evers, L.M.; ten Cate, H.; Biemond, B.J.; Duits, A.J.; et al. N-acetylcysteine reduces oxidative stress in sickle cell patients. Ann Hematol 2012, 91, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan Tahsin Ozpolat, J.C. , Xiaoyun Fu, Shelby A Cate, Jennie Le, Minhua Ling, Colette Norby, Dominic W Chung, Barbara A. Konkle, Jose A. Lopez. A Pilot Study of High-Dose N-Acetylcysteine Infusion in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. 2021.

- Vinchi, F.; De Franceschi, L.; Ghigo, A.; Townes, T.; Cimino, J.; Silengo, L.; Hirsch, E.; Altruda, F.; Tolosano, E. Hemopexin therapy improves cardiovascular function by preventing heme-induced endothelial toxicity in mouse models of hemolytic diseases. Circulation 2013, 127, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belcher, J.D.; Chen, C.; Nguyen, J.; Abdulla, F.; Zhang, P.; Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, P.; Killeen, T.; Miescher, S.M.; Brinkman, N.; et al. Haptoglobin and hemopexin inhibit vaso-occlusion and inflammation in murine sickle cell disease: Role of heme oxygenase-1 induction. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0196455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buehler, P.W.; Swindle, D.; Pak, D.I.; Ferguson, S.K.; Majka, S.M.; Karoor, V.; Moldovan, R.; Sintas, C.; Black, J.; Gentinetta, T.; et al. Hemopexin dosing improves cardiopulmonary dysfunction in murine sickle cell disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 175, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentinetta, T.; Belcher, J.D.; Brugger-Verdon, V.; Adam, J.; Ruthsatz, T.; Bain, J.; Schu, D.; Ventrici, L.; Edler, M.; Lioe, H.; et al. Plasma-Derived Hemopexin as a Candidate Therapeutic Agent for Acute Vaso-Occlusion in Sickle Cell Disease: Preclinical Evidence. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, P.M.; B.J.B.; Kesse-Adu, R.; Wahab, E.; Desai, P.C.; Boucher, A.; Eleftheriou, P.; Rijneveld, A.; De Castro, L.M.; Bergmann, S.; Kato, G.J.; Jochems, J.; Wilson, F.; Jung, K.; Gordeuk, V.R. Phase 1 Study of the Safety and Pharmacokinetics of CSL889 (Hemopexin) in Adults with SCD. Journal of Sickle Cell Disease 2024, 1.

- Stivala, S.; Gobbato, S.; Bonetti, N.; Camici, G.G.; Luscher, T.F.; Beer, J.H. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid reduces platelet activation and collagen-mediated cell adhesion in sickle cell disease mice. J Thromb Haemost 2022, 20, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.D.; Manfredini, V.; Peralba, M.C.; Benfato, M.S. Alpha-lipoic acid modifies oxidative stress parameters in sickle cell trait subjects and sickle cell patients. Clin Nutr 2009, 28, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhu, X.; Yu, A.; Ward, C.M.; Pace, B.S. delta-Aminolevulinate induces fetal hemoglobin expression by enhancing cellular heme biosynthesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2019, 244, 1220–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.R.; Brown, L.A.S.; Reynolds, M.; Dampier, C.D.; Lane, P.A.; Watt, A.; Kumari, P.; Harris, F.; Manoranjithan, S.; Mendis, R.D.; et al. Impact of arginine therapy on mitochondrial function in children with sickle cell disease during vaso-occlusive pain. Blood 2020, 136, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, C.A.; Brousseau, D.C.; Cohen, D.M.; Villella, A.; Dampier, C.; Brown, K.; Campbell, A.; Chumpitazi, C.E.; Airewele, G.; Chang, T.; et al. Sickle Cell Disease Treatment with Arginine Therapy (STArT): study protocol for a phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Trials 2023, 24, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrine, S.P.; Ginder, G.D.; Faller, D.V.; Dover, G.H.; Ikuta, T.; Witkowska, H.E.; Cai, S.P.; Vichinsky, E.P.; Olivieri, N.F. A short-term trial of butyrate to stimulate fetal-globin-gene expression in the beta-globin disorders. N Engl J Med 1993, 328, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atweh, G.F.; Sutton, M.; Nassif, I.; Boosalis, V.; Dover, G.J.; Wallenstein, S.; Wright, E.; McMahon, L.; Stamatoyannopoulos, G.; Faller, D.V.; et al. Sustained induction of fetal hemoglobin by pulse butyrate therapy in sickle cell disease. Blood 1999, 93, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Molokie, R.; Lavelle, D.; Gowhari, M.; Pacini, M.; Krauz, L.; Hassan, J.; Ibanez, V.; Ruiz, M.A.; Ng, K.P.; Woost, P.; et al. Oral tetrahydrouridine and decitabine for non-cytotoxic epigenetic gene regulation in sickle cell disease: A randomized phase 1 study. PLoS Med 2017, 14, e1002382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunthararajah, Y.; Molokie, R.; Saraf, S.; Sidhwani, S.; Gowhari, M.; Vara, S.; Lavelle, D.; DeSimone, J. Clinical effectiveness of decitabine in severe sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2008, 141, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Hu, T.; Ho, M.H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, M.; Patel, N.; Pi, W.; Choi, J.H.; Xu, H.; Ganapathy, V.; et al. Hydroxyurea differentially modulates activator and repressors of gamma-globin gene in erythroblasts of responsive and non-responsive patients with sickle cell disease in correlation with Index of Hydroxyurea Responsiveness. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1995–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Wang, J.; Tan, Y.; Beyer, A.I.; Xie, F.; Muench, M.O.; Kan, Y.W. Genome editing using CRISPR-Cas9 to create the HPFH genotype in HSPCs: An approach for treating sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 10661–10665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, V.; Christopher, A.C.; Rhiel, M.; Azhagiri, M.K.K.; Babu, P.; Walavalkar, K.; Saravanan, B.; Andrieux, G.; Rangaraj, S.; Srinivasan, S.; et al. Editing the core region in HPFH deletions alters fetal and adult globin expression for treatment of beta-hemoglobinopathies. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2023, 32, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniani, C.; Meneghini, V.; Lattanzi, A.; Felix, T.; Romano, O.; Magrin, E.; Weber, L.; Pavani, G.; El Hoss, S.; Kurita, R.; et al. Induction of fetal hemoglobin synthesis by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of the human beta-globin locus. Blood 2018, 131, 1960–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn, G.E.; Wienert, B.; Yang, L.; Shah, M.; Norton, L.J.; Burdach, J.; Kurita, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Pearson, R.C.M.; Funnell, A.P.W.; et al. Natural regulatory mutations elevate the fetal globin gene via disruption of BCL11A or ZBTB7A binding. Nat Genet 2018, 50, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, L.; Frati, G.; Felix, T.; Hardouin, G.; Casini, A.; Wollenschlaeger, C.; Meneghini, V.; Masson, C.; De Cian, A.; Chalumeau, A.; et al. Editing a gamma-globin repressor binding site restores fetal hemoglobin synthesis and corrects the sickle cell disease phenotype. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Lu, R.; Chang, J.C.; Kan, Y.W. NRF2, a member of the NFE2 family of transcription factors, is not essential for murine erythropoiesis, growth, and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 13943–13948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macari, E.R.; Lowrey, C.H. Induction of human fetal hemoglobin via the NRF2 antioxidant response signaling pathway. Blood 2011, 117, 5987–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhao, M.; Chang, C.; Lu, Q. The Bach Family of Transcription Factors: A Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016, 50, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belcher, J.D.; Nataraja, S.; Abdulla, F.; Zhang, P.; Chen, C.; Nguyen, J.; Ruan, C.; Singh, M.; Demes, S.; Olson, L.; et al. The BACH1 inhibitor ASP8731 inhibits inflammation and vaso-occlusion and induces fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attucks, O.C.; Jasmer, K.J.; Hannink, M.; Kassis, J.; Zhong, Z.; Gupta, S.; Victory, S.F.; Guzel, M.; Polisetti, D.R.; Andrews, R.; et al. Induction of heme oxygenase I (HMOX1) by HPP-4382: a novel modulator of Bach1 activity. PLoS One 2014, 9, e101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palani, C.D.; Zhu, X.; Alagar, M.; Attucks, O.C.; Pace, B.S. Bach1 inhibitor HPP-D mediates gamma-globin gene activation in sickle erythroid progenitors. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2024, 104, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Wu, F.; Yang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, T.; Deng, X.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. miR-144/451 inhibits c-Myc to promote erythroid differentiation. FASEB J 2020, 34, 13194–13210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Chao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Gong, X.; Liang, D.; Wang, Y. CAP1, a target of miR-144/451, negatively regulates erythroid differentiation and enucleation. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 2377–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhu, X.; Ward, C.M.; Starlard-Davenport, A.; Takezaki, M.; Berry, A.; Ward, A.; Wilder, C.; Neunert, C.; Kutlar, A.; et al. MIR-144-mediated NRF2 gene silencing inhibits fetal hemoglobin expression in sickle cell disease. Exp Hematol 2019, 70, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.E. Nrf2-mediated redox signalling in vascular health and disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2014, 75 (Suppl. 1), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, K.L.; Gayatri, V.; Kriya, K.; Sanjushree, N.; Vishwanathan Palanivel, S.; Anuradha, M.; Ramkumar, K.M. MiR-142-5p mediated Nrf2 dysregulation in gestational diabetes mellitus and its impact on placental angiogenesis. Placenta 2024, 158, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, K.; Lv, J. Down-regulation of microRNA-142-5p attenuates oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation-induced neuron injury through up-regulating Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 89, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teimouri, M.; Hosseini, H.; Shabani, M.; Koushki, M.; Noorbakhsh, F.; Meshkani, R. Inhibiting miR-27a and miR-142-5p attenuate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating Nrf2 signaling pathway. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BJ Biemond, B.S., F Wilson, J Jochems, LM Lindqvist, K Jung, T Gentinetta, S Costin, GJ Kato, P Eleftheriou, H Fok, E Wahab, PM Leung, J Sharif, A Boucher, R Fitzgerald, R Keese-Adu, R Azbell, D Liles, S Bergmann, S Lanzkron, V Gordeuk. A PHASE 1 STUDY OF CSL888 (HEMOPEXIN) IN ADULT PATIENTS WITH SICKLE CELL DISEASE. Hemasphere 2023, 7. [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, C.; Kuypers, F.; Larkin, S.; Hagar, W.; Vichinsky, E.; Styles, L. A pilot study of the short-term use of simvastatin in sickle cell disease: effects on markers of vascular dysfunction. Br J Haematol 2011, 153, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner, S.M.; Alexander, C.M.; Cook, T.J.; Boccuzzi, S.J.; Musliner, T.A.; Pedersen, T.R.; Kjekshus, J.; Pyorala, K. Reduced coronary events in simvastatin-treated patients with coronary heart disease and diabetes or impaired fasting glucose levels: subgroup analyses in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Arch Intern Med 1999, 159, 2661–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, D.; Ferreira, F.; Teles, M.J.; Porto, G.; Coimbra, S.; Rocha, S.; Santos-Silva, A. Catalase, Glutathione Peroxidase, and Peroxiredoxin 2 in Erythrocyte Cytosol and Membrane in Hereditary Spherocytosis, Sickle Cell Disease, and beta-Thalassemia. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Y.; Bae, C.Y.; Kasztan, M.; Pollock, D.M.; Russell, R.T.; Lebensburger, J.; Patel, R.P. Peroxiredoxin-2 recycling is slower in denser and pediatric sickle cell red cells. FASEB J 2022, 36, e22267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matte, A.; Federti, E.; Tibaldi, E.; Di Paolo, M.L.; Bisello, G.; Bertoldi, M.; Carpentieri, A.; Pucci, P.; Iatchencko, I.; Wilson, A.B.; et al. Tyrosine Phosphorylation Modulates Peroxiredoxin-2 Activity in Normal and Diseased Red Cells. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.H.; Kim, S.U.; Kwon, T.H.; Lee, D.S.; Ha, H.L.; Park, D.S.; Woo, E.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.M.; Chae, H.B.; et al. Peroxiredoxin II is essential for preventing hemolytic anemia from oxidative stress through maintaining hemoglobin stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012, 426, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).