1. Introduction

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is a significant protein found exclusively in mammalian embryos and is involved in both ontogenic and oncogenic growth. AFP was discovered in human fetal sera by Bergstrand and Czar in 1956. It functions as a carrier for several substances, including bilirubin, fatty acids, and potentially certain medications [

1,

2]. AFP levels in maternal serum (MS-AFP) and amniotic fluid can assist in early detection and genetic counseling for families with a background of congenital abnormalities. By calculating the multiple of the AFP median (MOM) and comparing it with the patient’s AFP median value, fetal malformation, and adverse conditions can be categorized [

3]. Based on the concentration of AFP in biological fluids, elevated levels of MS-AFP and amniotic fluid AFP are typically a sign of the existence of anatomical abnormalities, such as those seen in neural tube defects (NTDs), anencephaly, ventral wall defects, gastrointestinal atresia, renal anomalies, and disruption of placental barriers [

4,

5]. On the other end of the spectrum, low levels of AFP indicate the existence of chromosomal abnormalities (aneuploidy), such as trisomies, as well as fetal loss, renal pyelectasis, and fetal growth restriction [6-9].

The causes of elevated MS-AFP levels in different fetal abnormalities, particularly those affecting the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract, are mostly unclear. Similarly, the statement relates to reduced levels of MS-AFP in cases of aneuploidy such as Down syndrome.

While AFP serves different roles throughout fetal development, in the past ten years, an increasing number of studies have examined AFP and its application as a biomarker unique to tumors. Increased levels of AFP are commonly seen in adults during liver carcinogenesis and various tumor processes[10-12]. Considerable focus has been directed towards AFP as a biomarker for the detection of hepatocellular cancer. Unlike these primary subjects in prenatal screening programs. In this review article, we aim to present a comprehensive overview of AFP, including its physiology, detection methods, biological significance during pregnancy and beyond, and its usefulness as a marker in fetal anomalies, obstetrical problems, and pregnancy complications. Finally, advancements in AFP screening, combined biomarker approaches and future research directions.

2. AFP Physiology

AFP gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 4 (4q11-q13) and it has two independent enhancer and silencer regions[

13]. Mammalian AFP is categorized as a member of a protein family called albuminoid, which has three cysteine-rich domains. This family has four members: albumin (ALB), vitamin D–binding protein, AFP, and α-ALB[14-16]. It has 5 Pathogenic variants with clinical significance rs387906580, rs121912685, rs146692547, rs587776861and rs1719498256 according to GeneCards®: The Human Gene Database. AFP is a dominant serum protein in embryonic life as early as 1 month reflecting its critical involvement in early human development. 609 amino acids form the AFP protein, a single-polypeptide chain with a molecular weight of 69-kDa, consisting of 3%–5% carbohydrate. AFP is a negatively charged protein and has an isoelectric point of pH 4.57[

17,

18]. It is characterized by three distinct domains, arranged in a triplicate pattern, referred to as domains I, II, and III. These domains are formed by loops within the molecule, which are determined by the presence of disulfide bridges. As a result, the protein takes on a helical shape that resembles either a V or a U shape when examined by electron dot maps [

19]. The conservation of these domains in humans, rats, mice, and bovines suggests that AFP plays a similar functional role throughout these species [

20]. AFP is present in three major isoforms that vary in binding affinity for the lectin Lens culinaris agglutinin. The isoforms AFP-L1, AFP-L2, and AFP-L3 are present in variable quantities depending on the specific clinical circumstances[

21,

22].

3. AFP Detection Methods

AFP was initially quantified using immunoelectrophoresis, although this technique proved to be insufficiently sensitive. An innovative quantitative automated chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay was developed for clinical use, effectively replacing and improving upon prior clinical assays [

23,

24]. In addition, advancements in the detection of AFP have recently made considerable improvements in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and practicality. Fluorescent aptasensors, digital quantification, electrochemical aptasensors, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), photoelectrochemical (PEC) biosensors, microchip-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and digital image colorimetry are many techniques that provide diverse and efficient methods for detecting AFP. These techniques have the potential to be used in clinical analysis and diagnosis to improve the early diagnosis and management of different conditions. Detect AFP level using fluorescent aptasensors employing Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) achieves a remarkable level of sensitivity, with a detection limit as low as 400 pg/mL and a linear range 0.5 to 45 ng/Ml [

25]. Notably, the combination of quantum dots (QDs) with N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX (NMM) in enzyme-free catalytic hairpin assembly (CHA) amplification allows for the detection of AFP at extremely low levels, with a limit as low as 3 fg/Ml [

26]. Regarding digital quantification methods of AFP, droplet-based microfluidic digital analysis enables the indirect quantification of AFP at very low concentrations at femtomolar levels by utilizing streptavidin-conjugated β-galactosidase as a signal tag [

27]. Furthermore, using microfluidic array chips incorporating modified magnetic microparticles (MMPs) and Poisson distribution analysis enables the detection of AFP concentrations as low as 1 fg/mL, demonstrating a high level of sensitivity [

28]. Indeed, the electrochemical aptasensors with graphene oxide-based offer a label-free, cost-effective method with a detection limit of 3 pg/mL and a linear range of 0.01-100 ng/Ml [

29]. Interestingly, DNA hydrogel-based SERS biosensors offer high accuracy and reproducibility with a wide detection range (50 pg/mL to 0.5 μg/mL) and low detection limit (50 pg/mL) [

30,

31]. A rapid detection of AFP is provided as well using PEC Biosensors with a linear range of 0.1-500 ng/Ml[

32,

33]. Likewise, Microchip-Based ELISA can determine a trace level of APF limit of 1 pg/mL and a linear range of 1-500 pg/Ml[

34]. Moreover, the enhanced fluorescence enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (FELISA) method based on the human alpha-thrombin (HAT) detected AFP at the ultralow concentrations of 10-8 ng/mL which were at least 104 times lower than those of the conventional fluorescence assay and 106 times lower than those of the conventional ELISA[

35]. Recently, a novel technology improved AFP testing with portability, precision, and accessible cost, making it ideal for resource-limited settings. AFP analysis platform using digital image colorimetry functionalized gold nanoparticles change from purple red to light gray blue with varying AFP concentrations. These colour variations are recorded using a smartphone app to compute sample AFP content. The detection limit of this method was established at 0.083 ng/mL, with an average accuracy of 90.81%[

36].

Table 1.

Overview of the key methods for AFP detection based on recent research.

Table 1.

Overview of the key methods for AFP detection based on recent research.

| AFP Detection Methods |

Principal use |

Detection limit |

References |

| Fluorescent aptasensors |

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) |

400 pg/mL |

Zhou, L. et al.2019[25] |

| Simultaneous Detection Methods |

Catalytic hairpin assembly (CHA) amplification with quantum dots and N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX (NMM) |

3 fg/mL |

Chen, P. et al.2022[26] |

| Digital quantification |

Microfluidic array chips incorporating modified magnetic microparticles (MMPs) and Poisson distribution analysis |

1 fg/mL |

Tian, S. et al. 2018&2019 [27,28] |

| Electrochemical aptasensors, |

Nanocomposites graphene oxide-based |

3 pg/mL |

Yang, S., Zhang, F., Wang, Z. & Liang, Q.2018[29] |

| Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) |

Combine DNA hydrogels with Raman tags |

50 pg/mL |

Wang, Q. et al.2020[30]

Ma, H. et al.2017[31] |

| Photoelectrochemical (PEC) biosensors |

Light to generate an electrical signal |

0.01 ng/ml |

Li, X., Pan, X., Lu, J., Zhou, Y. & Gong, J.2020[33]

Xu, R. et al.2015[32] |

| Microchip-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) |

1 pg/mL |

Liu, Y. et al.2009[34] |

| Enhanced fluorescence ELISA (FELISA) |

Human alpha-thrombin (HAT) to trigger fluorescence "turn-on" signals |

10-8 ng/mL |

Wu, Y. et al.2017[35] |

| Colorimetric |

Gold nanoparticles act as colorimetric agents, then a smartphone app captures the color changes and calculates the AFP concentration in the sample |

0.083 ng/mL |

Liu, J., Geng, Q. & Geng, Z.2024[36] |

4. AFP during pregnancy and beyond

The yolk sac and fetal hepatocytes are the sources of AFP synthesis [

17,

37,

38]. AFP is introduced into the mother's bloodstream during pregnancy by the syncytiotrophoblast cell layer of the placenta. AFP can enter the maternal circulation through a non-specific process known as "spillover [

39]. The synthesis of AFP has been investigated in many in vitro systems, such as rat hepatomas and isolated fetal hepatocytes [

40,

41]. AFP is produced during the G-1 and S stages of the cell cycle [

42]. During pregnancy, fetal plasma AFP passes into the urine and is excreted in the amniotic fluid. The concentration of AFP in amniotic fluid is roughly 1/150th to 1/200th of the concentration found in fetal plasma. Additionally, the concentration of AFP in maternal serum is approximately 1/100th of the concentration seen in amniotic fluid [

43]. A maternal serum AFP (MS-AFP) level is considered elevated if it is 2.5 MOM, commonly known as the standard threshold. In fetal serum, the highest concentrations of 3 mg/ml (3,000,000 ng/mL) are reached around the third month at the end of the first trimester of pregnancy (between 10–13 weeks) and gradually decrease as the time of birth approaches to approximately 20,000 ng/Ml [

39,

44]. Amniotic fluid has comparable patterns of AFP concentrations but at lower levels. However, during early pregnancy, the level of MS-AFP is low 5 ng/mL at 10 weeks of pregnancy it gradually increases and reaches a peak of approximately 200-300 mg/L at 30-32 weeks and then progressively declines until delivery. Interestingly, AFP is undetectable (about 0.2 ng/mL) while not pregnant due to its rapid decline in adults [45-48].

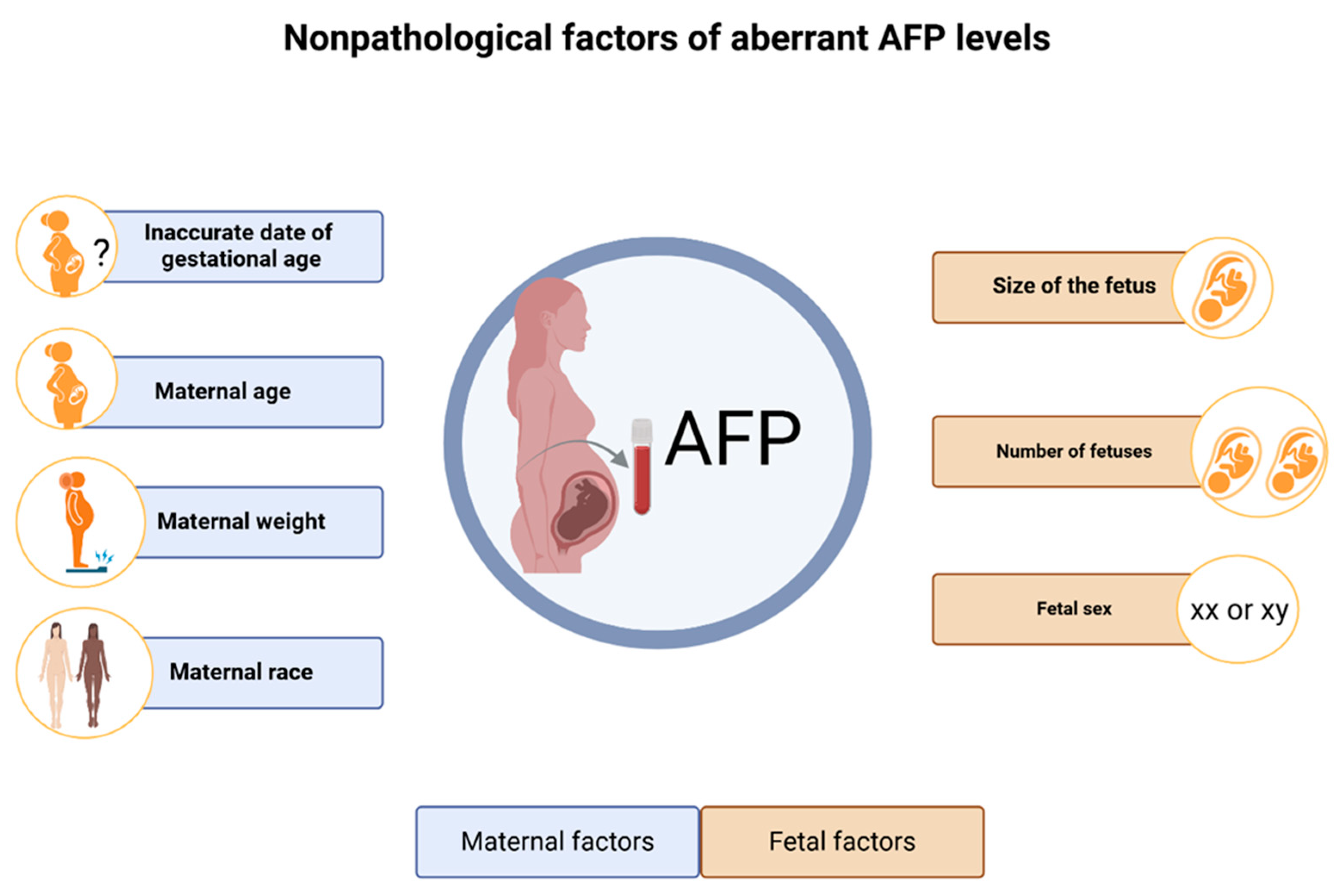

Studies were conducted to investigate the physiological and/or procedural factors that can substantially impact the MS-AFP concentrations. Notably, nonpathological elevated AFP can happen due to several conditions including the actual size of the fetus, and having a low birth weight, being born prematurely. In addition, inaccurate date of gestational age for example the pregnancy is further along than initially thought, AFP level may be higher than expected. Indeed, the number of fetuses, with multiple pregnancies (twins, triplets, etc.) having around twice the level found in singletons, as there is an increased amount of fetal tissue producing AFP [48-51]. Interestingly, higher maternal age and male fetal sex compared to female fetuses are correlated as well with elevated MS-AFP levels [

51,

52].

In contrast, maternal weight inversely correlated to MS-AFP level, since heavier pregnant women have lower median values due to increased blood volume [

53,

54]. Indeed, maternal race significantly affects AFP levels. Black women typically exhibit elevated AFP levels relative to other ethnic groups. Afro-Caribbean women have approximately 23% elevated AFP levels, while East Asians demonstrate roughly 8% diminished levels in comparison to Caucasians [

54,

55]. Finally, a prospective study demonstrated that women with diabetes have an inverse relationship between glycosylated hemoglobin and MS-AFP concentrations during pregnancy [

56]. All these conditions need to be taken into account when interpreting AFP levels.

After birth, the regulatory mechanisms that govern AFP change. AFP enhancers, which stimulate the transcription of the AFP gene during fetal development, are usually suppressed from the gene promoter after birth. Instead, these enhancers redirect their function to sustain albumin gene transcription throughout adulthood [

57]. In healthy term neonates, it is common to observe high blood AFP levels of up to 200,000 mg/L during the first days of life. Then, AFP levels decrease dramatically. The concentration of 500-6,500 mg/L at the end of the first month of life gradually falls to levels ranging from 1 to 100 mg/L by the age of 6 months. Subsequently, there is a continued and progressive decline. Then, a very small amount of AFP could be detected in normal adult human serum typically between 0.5 and around 15 mg/l[

48].

Figure 1.

Overview of nonpathological aberrant AFP levels.

Figure 1.

Overview of nonpathological aberrant AFP levels.

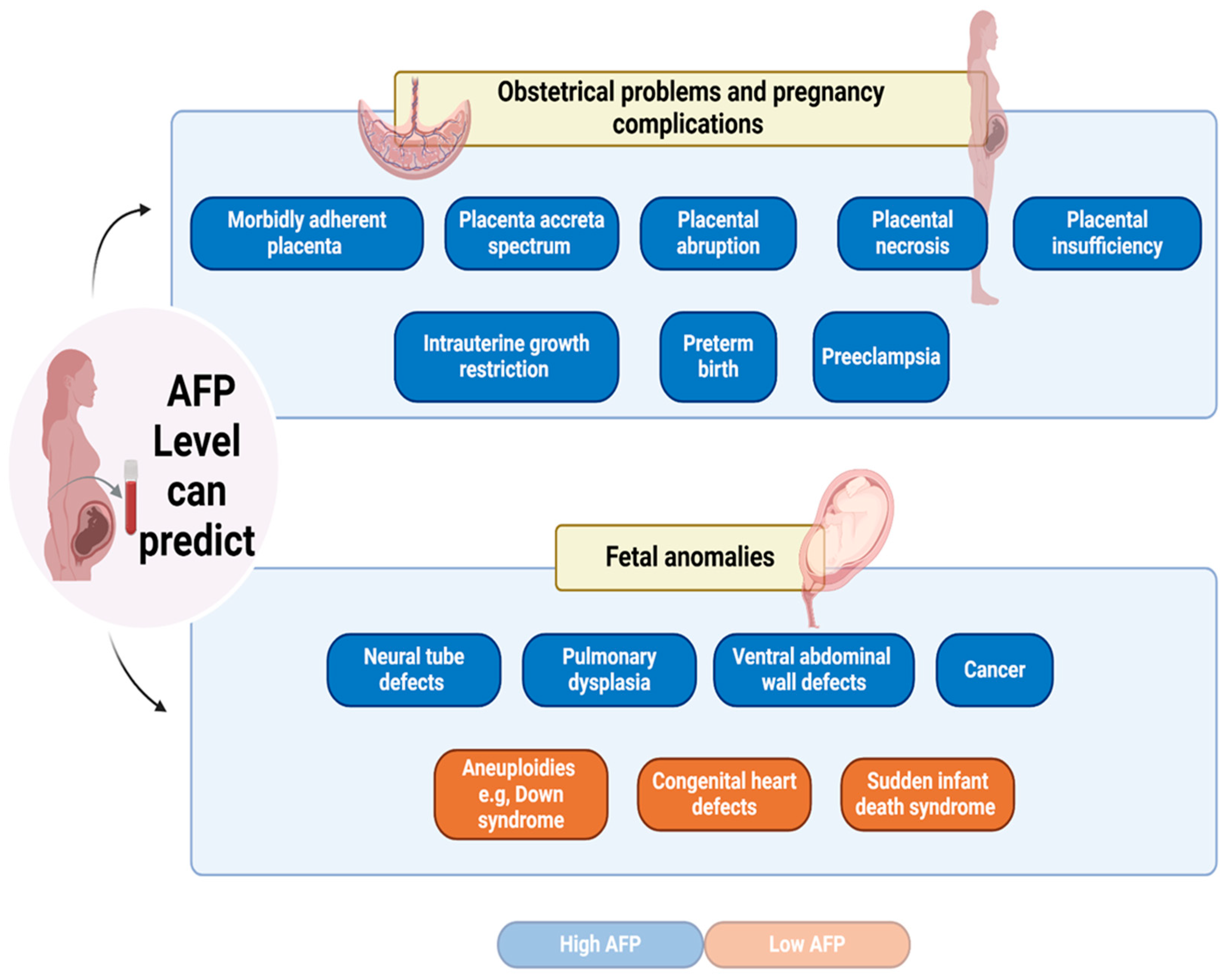

5. AFP as a marker for fetal anomalies

MS-AFP levels can function as important indicators of fetal anomalies, such as Neural tube defects (NTDs) and Down syndrome [

58]. Currently, AFP is utilized as a component of prenatal screening examinations. The American Academy of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommended in 2003 that all pregnant women need to have MS-AFP screening during the second trimester of pregnancy, namely between 16 to 18 weeks. This screening can be conducted as well between 15 to 20 weeks of gestation [

59].

In the mid-1970s, the initial developmental problems linked to aberrant AFP levels in the second trimester were NTDs. NTDs are serious congenital malformations that occur when the fetal brain and spinal cord do not develop properly with incomplete closure of the neural tube. AFP is key in diagnosing fetal open neural tube defects, characterized by cerebrospinal fluid leakage into the amniotic fluid. This leakage results in absorption into the maternal bloodstream, leading to elevated MS-AFP levels [60-62]. The reported sensitivity of MS-AFP in detecting NTDs is approximately 95% for anencephaly and 65-80% for open spinal NTDs [63-65]. However, Kjessler et al, demonstrated that AFP levels during early pregnancy, do not specifically indicate NTDs. Instead, they are more likely a product of fetal circulation [

66]. Furthermore, a study demonstrated that during the second trimester, there was a notable increase in the maternal blood concentration of MS-AFP in pulmonary dysplasia affected newborns [

67]. Increased levels of MS-AFP can also suggest the presence of additional fetal abnormalities, such as ventral abdominal wall defects, intestinal atresias, and sacrococcygeal teratomas. The leak of AFP from these defected organs into amniotic fluid leads to higher MS-AFP concentration [

64,

68].

Indeed, AFP can be elevated due to the presence of certain tumors in the fetus, therefore, AFP is a useful biomarker for diagnosing, managing, and following up in select pediatric cancers, with overexpression in germ cell tumors (GCTs), hepatoblastoma (HB), and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

69]. AFP is frequently raised in germ cell cancers, such as endodermal sinus tumors, which may manifest in the fetus[

70] . Notably, a possible association between AFP levels and embryonic lung masses was documented in a case where AFP was increased in a fetus with Type III cystic adenomatoid lung malformation [

71]. Increased AFP levels in children correlate as well with ovarian masses; nevertheless, further investigation is required to validate this correlation and establish its efficacy as a biomarker for ovarian mass detection [

72]. Moreover, Wilms tumor is an uncommon form of kidney cancer in children. Elevated AFP levels have been seen in some patients, they may be associated with tumor size and metastasis [

73]. In addition, hepatic disorders, particularly HB and HCC, are associated with elevated levels of AFP, especially in children [

69]. In general, in placental tumors, the elevated AFP levels in maternal serum are caused by its release into both the amniotic fluid and the maternal placental circulation [

62].

On the contrary, the NTDs, the chromosomal abnormalities (aneuploidies), were associated with low levels of AFP, such as Down's syndrome (trisomy 21). A reduced AFP level may also be associated with Turner's syndrome and Edwards syndrome (trisomy 13) with lower sensitivity compared to Down's syndrome [

64,

68,

74]. Indeed, a recent study showed that MS-AFP could be monitored in the second trimester to detect congenital heart defects (CHD). Interestingly, AFP level was significantly lower in mothers of neonates with CHD [

75]. Additionally, a correlation was discovered between low levels of AFP during the second trimester and the occurrence of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) in the future. The researchers in this study proposed that the risk of SIDS could be influenced, at least in part, by compromised fetal development and the occurrence of unfavorable preterm delivery events [

76].

6. AFP as a marker for obstetrical problems and pregnancy complications

Studies have demonstrated that MS-AFP when clinically elevated could be used as a marker for obstetrical issues and pregnancy complications that help to predict the management of difficult pregnancies as previously shown in the following observations [

4,

67,

77,

78]. A prospective epidemiological study of 23,792 singleton pregnancies determined a correlation between a high level of MS-AFP (above 2.5 MoM) and a higher risk of pathological pregnancies and an increased risk of consequent fetal death [

79]. Indeed, a cohort study of 236,714 singleton pregnancies with both first and second-trimester prenatal screening, and with excluding criteria of pregnancies have aneuploidies and NTDs or abdominal wall defects, showed elevated risk for the morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) among multiparous women with pregnancy associated with an increase in MS-AFP [

80]. A recent study demonstrated that elevated levels of MS-AFP over 200 ng/ml during the early stages of pregnancy can serve as an indicator for the development of MAP during the later stages of pregnancy in comparison to placenta previa (PP) [

81]. Increased placental abruption risk could be predicted at an early stage of pregnancy through the first trimester and second-trimester high MS-AFP level [

82]. Moreover, in the event of placental necrosis, the uterine-placenta barrier leaks, increasing the quantity of AFP transferred from the fetus to the mother. In addition, Meng-Yao Yu et al; reported a rare case of extremely elevated AFP level at 1032 ng/mL of a 23-year-old female patient associated with placental necrosis [

83]. However, Bartkute et al; in a study based on pregnancy and delivery data from 5520 women between 1999 and 2014 at the University Hospital of Zurich, demonstrated that pregnant women who have high levels of MS-AFP in second-trimester screening and no fetal abnormalities discovered through sonographically should undergo a third-trimester ultrasound screening to rule out any other potential pregnancy problems [

84]. Indeed, an established role of AFP in predicting preterm birth [

85]. Increased AFP levels, particularly in early pregnancy, are correlated with a greater chance of preterm birth, potentially attributable to placental impairment or other underlying problems that may induce early labor. A systematic review analyzed 24 studies published between January 1991 and October 2007, comparing 207,135 women to evaluate the association between elevated second-trimester MS-AFP and singleton preterm birth.

Preeclampsia is a hypertensive condition of pregnancy that poses significant risks to both mother's and baby's health. Research indicates that elevated AFP levels (exceeding 2.0 MOM) are associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia, especially in early-onset cases occurring before 34 weeks of gestation [

5,

68]. AFP combined with other biomarkers was tested for disease severity. Notably, AFP levels were not significantly different between preeclampsia and control groups [

86]. Moreover, Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a serious disorder that restricts fetal development, increasing the risk of morbidity and mortality. Infants with IUGR encounter considerable health risks, such as increased susceptibility to metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and neurodevelopmental disorders. Timely detection of IUGR via efficient screening and monitoring can aid in managing and reducing the negative consequences linked to the condition [

87]. High AFP level greater than 2.0 MoM, correlate with a heightened IUGR risk. The threshold had a high specificity (94%) for predicting IUGR; however, the sensitivity was very low, suggesting that while increased AFP is a robust signal, it may not identify all instances of IUGR [

88].

Finally, a study demonstrated the predictive ability of AFP to pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) for adverse placentally related outcomes. A high MS-AFP: PAPP-A ratio greater than 10 in the first trimester is predicted for placental insufficiency, a disorder in which the placenta inadequately supplies nutrition and oxygen to the fetus, resulting in different negative pregnancy outcomes[

89]. All these conditions underscore the importance of AFP not only as a biomarker for detecting specific fetal conditions but also for monitoring the overall health of the pregnancy.

Figure 2.

AFP level can predict obstetrical problems, pregnancy complications, and fetal anomalies.

Figure 2.

AFP level can predict obstetrical problems, pregnancy complications, and fetal anomalies.

7. Advancements in AFP screening and combined biomarker approaches

The diagnosis and management of fetal abnormalities and pregnancy problems have been greatly improved by advances in AFP screening and integrated biomarker methods. With the primary goal of discovering diseases including Down syndrome and fetal anatomical defects first and second-trimester screenings were developed. These screens contribute to early detection, allowing for more effective care and decision-making during pregnancy [

90]. The combinations of AFP, unconjugated estriol (uE3), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), inhibin A, and maternal age, yield an 80% detection rate and a 5% false positive rate of Down syndrome [

91]. Moreover, quadruple screening AFP, uE3, hCG, and inhibin A during the second trimester of pregnancy can provide early indications of maternal and fetal unfavorable pregnancy outcomes [

92]. Interestingly, the sensitivity of prenatal screening for fetal abnormalities can reach a sensitivity of 97.93% by the combination of 4D color ultrasound with maternal serological tests (such as AFP, hCG, PAPP-A, and VitB12) [

93]. AFP along with first trimester biomarkers and mean arterial pressure serve as the most effective predictors of early-onset pre-eclampsia [

94]. A significant correlation between MS-AFP levels and preterm birth is observed when other aberrant pregnancy markers (e.g. hCG and uE3) are also raised [

95]. Furthermore, we can predict unfavorable pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth, IUGR, and macrosomia using first- and second-trimester serum markers PAPP-A, AFP, and maternal weight [

96]. Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) defines the atypical invasion of trophoblastic tissues. AFP, with β-hCG, PAPP-A, and cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA), can predict PAS during pregnancy [

97]. Indeed, pregnancies characterized by unexplained mid-trimester elevations in maternal serum hCG and/or MS AFP are associated with an increased risk of complications due to placental insufficiency [

98]. Increased levels of AFP and hCG, coupled with reduced estriol, are linked to negative outcomes including pregnancy-induced hypertension, miscarriage, preterm delivery, and intrauterine fetal death [

99,

100]. These methods enhance the accuracy and reliability of prenatal screening, offering better outcomes for both mothers and fetuses.

8. AFP limitation, future Directions Research, and conclusion

Aberrant levels of AFP have been linked to a higher risk of congenital abnormalities, poor obstetric outcomes, morbidly adherent placenta, and other serious conditions discussed in this review. Indeed, MS-AFP values require careful interpretation due to the influence of various factors. A deeper understanding of the parameters influencing MS-AFP levels is essential for improving the interpretation of AFP in prenatal screening and risk assessment. Notably, determining the AFP concentrations showed a significant development through advanced technologies that may help to determine a specific level for certain diseases. These results highlight the value of AFP screening in the early stages of pregnancy in order to detect high-risk pregnancies and treat them properly to enhance outcomes for both the mother and the fetus. However, AFP use as a standalone biomarker remains limited. AFP screening can lead to false positives or false negatives. This is why when the level of MS-AFP is out of line, more prenatal assessment is required to determine the exact abnormality. Therefore, integrating AFP measurements with other tests can improve the precision of diagnosis, hence increasing its utility in prenatal screening and genetic counseling, establishing AFP as a crucial element of prenatal screening programs. Comprehensive screening methods and effective treatment strategies continue to require further research and development.

Regardless of these, it remains uncertain if AFP alone serves as a biochemical indicator for the illnesses or if AFP itself actively contributes to the mechanisms that cause fetal anomalies, obstetrical problems, and pregnancy complications discussed here. Therefore, more molecular research are needed to answer this inquiry which may lead to discover a new potential function of AFP and help in monitoring treatment protocols in the future.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.M. and M.M.; methodology, S.M.; software, S.M.; validation, S.M., M.M.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M.; resources, S.M.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M, M.M.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, M.M.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.” This study does not require approval of the Institutional Review Board because no patient data is contained in this article. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding of the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia, through Project Number: GSSRD-24.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFP |

Alpha-fetoprotein |

| ALB |

albumin |

| cffDNA |

cell-free fetal DNA |

| CHA |

catalytic hairpin assembly |

| CHD |

congenital heart defects |

| ELISA |

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FRET |

Förster resonance energy transfer |

| GCTs |

Germ cell tumors |

| HB |

hepatoblastoma |

| HCC |

hepatocellular carcinoma |

| hCG |

human chorionic gonadotrophin |

| IUGR |

Intrauterine growth restriction |

| MAP |

morbidly adherent placenta |

| MMPs |

modified magnetic microparticles |

| MOM |

multiples of the median |

| MS-AFP |

maternal serum Alpha-fetoprotein |

| NMM |

N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX |

| NTDs |

neural tube defects |

| PAPP-A |

pregnancy-associated plasma protein A |

| PAS |

Placenta accreta spectrum |

| PEC |

photoelectrochemical |

| PP |

placenta previa |

| QDs |

quantum dots |

| SERS |

surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy |

| SIDS |

sudden infant death syndrome |

| uE3 |

unconjugated estriol |

| |

|

References

- Mizejewski, G. J. Alpha-fetoprotein Structure and Function: Relevance to Isoforms, Epitopes, and Conformational Variants. Exp. Biol. Med. 226, 377–408 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Murray, M. J. & Nicholson, J. C. α-Fetoprotein. Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 96, 141–147 (2011).

- Cho, S. , Durfee, K. K., Keel, B. A. & Parks, L. H. Perinatal outcomes in a prospective matched pair study of pregnancy and unexplained elevated or low AFP screening. J. Perinat. Med. 25, 476–483 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Killam, W. P. , Miller, R. C. & Seeds, J. W. Extremely high maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein levels at second-trimester screening. Obstet. Gynecol. 78, 257–261 (1991).

- Waller, D. K. , Lustig, L. S., Cunningham, G. C., Feuchtbaum, L. B. & Hook, E. B. The association between maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein and preterm birth, small for gestational age infants, preeclampsia, and placental complications. Obstet. Gynecol. 88, 816–822 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Cuckle, H. Biochemical screening for Down syndrome. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 92, 97–101 (2000).

- Rausch, D. N. , Lambert-Messerlian, G. M. & Canick, J. A. Participation in maternal serum screening for Down syndrome, neural tube defects, and trisomy 18 following screen-positive results in a previous pregnancy. West. J. Med. 173, 180–183 (2000).

- Kiran, T. S. U. , Bethel, J. & Bhal, P. S. Correlation of abnormal second trimester maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) levels and adverse pregnancy outcome. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. J. Inst. Obstet. Gynaecol. 25, 253–256 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Muller, F.; et al. Very low alpha-fetoprotein in Down syndrome maternal serum screening. Prenat. Diagn. 23, 584–587 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Bloomer, J. R. , Waldmann, T. A., McIntire, K. R. & Klatskin, G. alpha-fetoprotein in noneoplastic hepatic disorders. JAMA 233, 38–41 (1975). [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D. T. , Calaminus, G. & Göbel, U. Diagnostic value of alpha 1-fetoprotein and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin in infancy and childhood. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 18, 11–26 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.-F.; et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic analysis of 429 patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 15, 5976–5982 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Nakabayashi, H.; et al. A position-dependent silencer plays a major role in repressing alpha-fetoprotein expression in human hepatoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 5885–5893 (1991).

- Mizejewski, G. J. The phylogeny of alpha-fetoprotein in vertebrates: survey of biochemical and physiological data. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 5, 281–316 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Long, L. , Davidson, J. N. & Spear, B. T. Striking differences between the mouse and the human α-fetoprotein enhancers. Genomics 83, 694–705 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Terentiev, A. A. & Moldogazieva, N. T. Alpha-fetoprotein: a renaissance. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelopmental Biol. Med. 34, 2075–2091 (2013).

- Gitlin, D. , Perricelli, A. & Gitlin, G. M. Synthesis of -fetoprotein by liver, yolk sac, and gastrointestinal tract of the human conceptus. Cancer Res. 32, 979–982 (1972).

- Yachnin, S. The clinical significance of human alpha-fetoprotein. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 8, 84–90 (1978).

- Luft, A. J. & Lorscheider, F. L. Structural analysis of human and bovine alpha-fetoprotein by electron microscopy, image processing, and circular dichroism. Biochemistry 22, 5978–5981 (1983).

- Baker, M. E. Evolution of alpha-fetoprotein: sequence comparisons among AFP species and with albumin species. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelopmental Biol. Med. 9, 123–136 (1988). [CrossRef]

- Debruyne, E. N. & Delanghe, J. R. Diagnosing and monitoring hepatocellular carcinoma with alpha-fetoprotein: new aspects and applications. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 395, 19–26 (2008). [CrossRef]

- AlSalloom, A. A. M. An update of biochemical markers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Health Sci. 10, 121–136 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Nishizono, I.; et al. Rapid and sensitive chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay for measuring tumor markers. Clin. Chem. 37, 1639–1644 (1991). [CrossRef]

- Hanif, H.; et al. Update on the applications and limitations of alpha-fetoprotein for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 216–229 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; et al. An fluorescent aptasensor for sensitive detection of tumor marker based on the FRET of a sandwich structured QDs-AFP-AuNPs. Talanta 197, 444–450 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; et al. Simultaneous Homogeneous Fluorescence Detection of AFP and GPC3 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Clinical Samples Assisted by Enzyme-Free Catalytic Hairpin Assembly. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 28697–28705 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; et al. Digital analysis with droplet-based microfluidic for the ultrasensitive detection of β-gal and AFP. Talanta 186, 24–28 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; et al. A digital quantification method for the detection of biomarkers on a microfluidic array chip. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 298, 126851 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. , Zhang, F., Wang, Z. & Liang, Q. A graphene oxide-based label-free electrochemical aptasensor for the detection of alpha-fetoprotein. Biosens. Bioelectron. 112, 186–192 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Preparation of Aptamer Responsive DNA Functionalized Hydrogels for the Sensitive Detection of α-Fetoprotein Using SERS Method. Bioconjug. Chem. 31, 813–820 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; et al. Multiplex Immunochips for High-Accuracy Detection of AFP-L3% Based on Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering: Implications for Early Liver Cancer Diagnosis. Anal. Chem. 89, 8877–8883 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; et al. A sensitive photoelectrochemical biosensor for AFP detection based on ZnO inverse opal electrodes with signal amplification of CdS-QDs. Biosens. Bioelectron. 74, 411–417 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , Pan, X., Lu, J., Zhou, Y. & Gong, J. Dual-modal visual/photoelectrochemical all-in-one bioassay for rapid detection of AFP using 3D printed microreactor device. Biosens. Bioelectron. 158, 112158 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Microchip-based ELISA strategy for the detection of low-level disease biomarker in serum. Anal. Chim. Acta 650, 77–82 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; et al. Enhanced Fluorescence ELISA Based on HAT Triggering Fluorescence “Turn-on” with Enzyme–Antibody Dual Labeled AuNP Probes for Ultrasensitive Detection of AFP and HBsAg. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 9369–9377 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , Geng, Q. & Geng, Z. A Route to the Colorimetric Detection of Alpha-Fetoprotein Based on a Smartphone. Micromachines 15, 1116 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bergstrand, C. G. & Czar, B. Demonstration of a new protein fraction in serum from the human fetus. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 8, 174 (1956). [CrossRef]

- Halbrecht, I. & Klibanski, C. Identification of a new normal embryonic haemoglobin. Nature 178, 794–795 (1956). [CrossRef]

- Habib, Z. A. Maternal serum alpha-feto-protein: its value in antenatal diagnosis of genetic disease and in obstetrical-gynaecological care. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. Suppl. 61, 1–92 (1977).

- Kanai, K. , Endo, Y., Oda, T. & Kaneko, Y. Synthesis of alpha-fetoprotein by rat ascites hepatoma cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 259, 29–36 (1975). [CrossRef]

- Leffert, H. L. & Sell, S. ALPHA1-FETOPROTEIN BIOSYNTHESIS DURING THE GROWTH CYCLE OF DIFFERENTIATED FETAL RAT HEPATOCYTES IN PRIMARY MONOLAYER CULTURE. J. Cell Biol. 61, 823–829 (1974). [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, Y. & Hirai, H. Alpha-Fetoprotein and albumin synthesis during the cell cycle. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 259, 37–44 (1975). [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. K. & Yang, Y. H. Alpha-fetoprotein values in maternal serum and amniotic fluid for prenatal screening of genetic disorders. Yonsei Med. J. 28, 218–227 (1987). [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, D. & Boesman, M. Serum alpha-fetoprotein, albumin, and gamma-G-globulin in the human conceptus. J. Clin. Invest. 45, 1826–1838 (1966). [CrossRef]

- Masseyeff, R. , Gilli, J., Krebs, B., Calluaud, A. & Bonet, C. Evolution of alpha-fetoprotein serum levels throughout life in humans and rats, and during pregnancy in the rat. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 259, 17–28 (1975).

- Ball, D. , Rose, E. & Alpert, E. Alpha-fetoprotein levels in normal adults. Am. J. Med. Sci. 303, 157–159 (1992). [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S. G. , Kjessler, B., Sherman, M. S. & Wahlström, J. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in maternal serum and amniotic fluid in singleton pregnant women in their 10th-25th week post last menstrual period. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. Suppl. 69, 20–24 (1977). [CrossRef]

- Mizejewski, G. J. Levels of alpha-fetoprotein during pregnancy and early infancy in normal and disease states. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 58, 804–826 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Entezami, M. , Runkel, S., Sarioglu, N., Hese, S. & Weitzel, H. K. Diagnostic dilemma with elevated level of α-fetoprotein in an undiagnosed twin pregnancy with a small discordant holoacardius acephalus. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 177, 466–468 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Crandall, B. F. & Chua, C. Risks for fetal abnormalities after very and moderately elevated AF-AFPs. Prenat. Diagn. 17, 837–841 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Lei, U.; et al. Reproductive factors and extreme levels of maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein: a population-based study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 83, 1147–1151 (2004).

- Szabó, M. , Veress, L., Münnich, Á. & Papp, Z. Maternal Age-Dependent and Sex-Related Changes of Gestational Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 10, 368–372 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Haddow, J. E. , Kloza, E. M., Knight, G. J. & Smith, D. E. Relation between maternal weight and serum alpha-fetoprotein concentration during the second trimester. Clin. Chem. 27, 133–134 (1981). [CrossRef]

- Crandall, B. F. , Lebherz, T. B., Schroth, P. C. & Matsumoto, M. Alpha-fetoprotein concentrations in maternal serum: relation to race and body weight. Clin. Chem. 29, 531–533 (1983). [CrossRef]

- Bredaki, F. E. , Wright, D., Akolekar, R., Cruz, G. & Nicolaides, K. H. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein in normal pregnancy at 11-13 weeks’ gestation. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 30, 274–279 (2011).

- Baumgarten, A. & Robinson, J. Prospective study of an inverse relationship between maternal glycosylated hemoglobin and serum α-fetoprotein concentrations in pregnant women with diabetes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 159, 77–81 (1988). [CrossRef]

- Camper, S. A. & Tilghman, S. M. Postnatal repression of the alpha-fetoprotein gene is enhancer independent. Genes Dev. 3, 537–546 (1989). [CrossRef]

- Racusin, D. A.; et al. Role of Maternal Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein and Ultrasonography in Contemporary Detection of Spina Bifida. Am. J. Perinatol. 32, 1287–1291 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Cheschier, N. & ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin. Neural tube defects. Number 44, July 2003. (Replaces committee opinion number 252, March 2001). Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 83, 123–133 (2003).

- Driscoll, D. A. & Gross, S. J. Screening for fetal aneuploidy and neural tube defects. Genet. Med. 11, 818–821 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Muller, F. Prenatal biochemical screening for neural tube defects. Childs Nerv. Syst. 19, 433–435 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Głowska-Ciemny, J.; et al. Fetal and Placental Causes of Elevated Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein Levels in Pregnant Women. J. Clin. Med. 13, 466 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bradley, L. A. , Palomaki, G. E. & McDowell, G. A. Technical standards and guidelines: Prenatal screening for open neural tube defects: This new section on “Prenatal Screening for Open Neural Tube Defects,” together with the new section on “Prenatal Screening for Down Syndrome,” replaces the previous Section H of the American College of Medical Genetics Standards and Guidelines for Clinical Genetics Laboratories. Genet. Med. 7, 355–369 (2005).

- Glick, P. L.; et al. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein is a marker for fetal anomalies in pediatric surgery. J. Pediatr. Surg. 23, 16–20 (1988). [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; et al. Complement factors and alpha-fetoprotein as biomarkers for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of neural tube defects. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1478, 75–91 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Kjessler, B. , Johansson, S. G., Sherman, M., Gustavson, K. H. & Hultquist, G. Alpha-fetoprotein in antenatal diagnosis of congenital nephrosis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 1, 432–433 (1975). [CrossRef]

- Elrahim, M. M. A. , Ch, M. B. B. & Mohamed, I. Alpha-feto protein in obstetrics. 24, (2020).

- Mizejewski, G. J. Biological roles of alpha-fetoprotein during pregnancy and perinatal development. Exp. Biol. Med. Maywood NJ 229, 439–463 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Houwelingen, L. V. , Sandoval, J. A., Houwelingen, L. V. & Sandoval, J. A. Alpha-Fetoprotein in Malignant Pediatric Conditions. in Proof and Concepts in Rapid Diagnostic Tests and Technologies (IntechOpen, 2016). [CrossRef]

- Rebischung, C. , Pautier, P., Morice, P., Lhomme, C. & Duvillard, P. α-Fetoprotein Production by a Malignant Mixed Müllerian Tumor of the Ovary. Gynecol. Oncol. 77, 203–205 (2000).

- Petit, P.; et al. Type III congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung: another cause of elevated alpha fetoprotein? Clin. Genet. 32, 172–174 (1987). [CrossRef]

- Matonóg, A. & Drosdzol-Cop, A. Alpha-fetoprotein level in fetuses, infants, and children with ovarian masses: a literature review. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1307619 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Crocoli, A. , Madafferi, S., Jenkner, A., Zaccara, A. & Inserra, A. Elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein in Wilms tumor may follow the same pattern of other fetal neoplasms after treatment: evidence from three cases. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 24, 499–502 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Benn, P. A. & Ying, J. Preliminary estimate for the second-trimester maternal serum screening detection rate of the 45,X karyotype using alpha-fetoprotein, unconjugated estriol and human chorionic gonadotropin. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Perinat. Med. Fed. Asia Ocean. Perinat. Soc. Int. Soc. Perinat. Obstet. 15, 160–166 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Aghaamoo, S. , Lotfi, M., Mirmohammadkhani, M. & Hemmatian, M. N. Evaluation of Second-Trimester Maternal Serum AFP Value in the Detection of Congenital Heart Defects. Middle East J. Rehabil. Health Stud. 8, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. C. S.; et al. Second-trimester maternal serum levels of alpha-fetoprotein and the subsequent risk of sudden infant death syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 978–986 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Duric, K.; et al. Second trimester total human chorionic gonadotropin, alpha-fetoprotein and unconjugated estriol in predicting pregnancy complications other than fetal aneuploidy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 110, 12–15 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, A.; et al. RETIRED: Obstetrical Complications Associated With Abnormal Maternal Serum Markers Analytes. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 30, 918–932 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Pejtsik, B. , Rappai, G., Pintér, J. & Kelemen, A. [Correlation between elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein, certain pregnancy complications and fetal death]. Orv. Hetil. 133, 2621–2624 (1992).

- Lyell, D. J.; et al. Maternal serum markers, characteristics and morbidly adherent placenta in women with previa. J. Perinatol. Off. J. Calif. Perinat. Assoc. 35, 570–574 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Azadi Teaching Hospital, Kirkuk, Iraq, Hassan, S., Ghalib, A., & of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine, Kirkuk University, Kirkuk, Iraq. Maternal Serum Alpha Feto Protein Level May Predict Morbidly Adherent Placenta in Women with Placenta Previa. Iraqi J. Med. Sci. 20, 278–285 (2022).

- Ananth, C. V. , Wapner, R. J., Ananth, S., D’Alton, M. E. & Vintzileos, A. M. First-Trimester and Second-Trimester Maternal Serum Biomarkers as Predictors of Placental Abruption. Obstet. Gynecol. 129, 465–472 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-Y. , Xi, L., Zhang, J.-X. & Zhang, S.-C. Possible connection between elevated serum α-fetoprotein and placental necrosis during pregnancy: A case report and review of literature. World J. Clin. Cases 6, 675–678 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Bartkute, K. , Balsyte, D., Wisser, J. & Kurmanavicius, J. Pregnancy outcomes regarding maternal serum AFP value in second trimester screening. J. Perinat. Med. 45, 817–820 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. , Sampurna, M. T. A. & Aditiawarman. The role of maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein in preterm birth: A literature review. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 18, 738–741 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Duan, H. , Zhao, G., Xu, B., Hu, S. & Li, J. Maternal Serum PLGF, PAPPA, β-hCG and AFP Levels in Early Second Trimester as Predictors of Preeclampsia. Clin. Lab. 63, 921–925 (2017).

- Kesavan, K. & Devaskar, S. U. Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Postnatal Monitoring and Outcomes. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 66, 403–423 (2019).

- Odibo, A. O. , Sehdev, H. M., Stamilio, D. M. & Macones, G. A. Evaluating the Thresholds of Abnormal Second Trimester Multiple Marker Screening Tests Associated with Intra-Uterine Growth Restriction. Am. J. Perinatol. 23, 363–368 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A. E.; et al. The association between first trimester AFP to PAPP-A ratio and placentally-related adverse pregnancy outcome. Placenta 81, 25–31 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Edwards, L. & Hui, L. First and second trimester screening for fetal structural anomalies. Semin. Fetal. Neonatal Med. 23, 102–111 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Canick, J. A. & MacRae, A. R. Second Trimester Serum Markers. Semin. Perinatol. 29, 203–208 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.-Y. , Zhang, C.-Y. & Ying, C.-M. Serum markers in quadruple screening associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes: A case–control study in China. Clin. Chim. Acta 511, 278–281 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lu, H. , Huang, Z., Lin, L. & Ding, X. Value Analysis of Four-Dimensional Color Ultrasound Combined with Maternal Serological Index in Prenatal Screening for Fetal Anomalies. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 30, 248–253 (2024).

- Nevalainen, J. , Korpimaki, T., Kouru, H., Sairanen, M. & Ryynanen, M. Performance of first trimester biochemical markers and mean arterial pressure in prediction of early-onset pre-eclampsia. Metab. - Clin. Exp. 75, 6–15 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W. , Chen, L. & Bernal, A. L. Is elevated maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein in the second trimester of pregnancy associated with increased preterm birth risk?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 145, 57–64 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.; et al. Prediction of Pregnancy Complications With Maternal Biochemical Markers Used in Down Syndrome Screening. Cureus 14, e23115. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. & Wang, S. Potential Serum Biomarkers in Prenatal Diagnosis of Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Front. Med. 9, 860186 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulos, G. , Gkogkos, P. & Decavalas, G. Mid-Trimester Maternal Serum hCG and Alpha Fetal Protein Levels: Clinical Significance and Prediction of Adverse Pregnancy Outcome. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 11, 102–106 (2013).

- Yaron, Y.; et al. Second-trimester maternal serum marker screening: Maternal serum α-fetoprotein, β-human chorionic gonadotropin, estriol, and their various combinations as predictors of pregnancy outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 181, 968–974 (1999).

- Alizadeh-Dibazari, Z. , Alizadeh-Ghodsi, Z. & Fathnezhad-kazemi, A. Association Between Serum Markers Used in the Routine Prenatal Screening with Pregnancy Outcomes: A Cohort Study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India 72, 6–18 (2022). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).