Introduction: Codon-Nucleotide Relationships

A codon, a triplet of DNA (A, G, T, C) or RNA nucleotides (A, G, U, C), dictates protein synthesis by encoding specific amino acids or stop signals. Translation initiates at the AUG codon, where the ribosome assembles amino acids into polypeptides until a stop codon halts the process. This sequence—transcription, translation, and post-translational modification—produces proteins critical for tissues (e.g., muscle, hair), enzymes, antibodies, and countless biological roles. Natural codon usage subtly tunes translation rates, but synthetic modifications, such as replacing uridine with N1-methylpseudouridine (m1ψ) in SARS-CoV-2 spike mRNA, introduce deliberate shifts. (Shabalina 2013, Quax 2015) The increase mass of m1ψ (~258 Da vs. uridine’s 244 Da) and its influence on tautomerism, a dynamic interconversion of molecular isomers involving hydrogen shifts, reshape the energetic and temporal landscape of protein synthesis.

The mass increment, per E=mc2 (where E is energy, m is mass, c=3×108 m/s), yields a small energy increase (ΔE= 2.0923x10-9 J for Δm = 14 Da, clarification section), negligible macroscopically but significant quantum-mechanically, not explosive, but a subtle elevation of codon energy (Lambert 2013, Nance 2021). This shift couples with E=hf, where Planck’s constant (h=6.626×10−34 J*s) and vibrational frequency (f) tie energy to molecular dynamics. A heavier m1ψ reduces f (since f∝1/√m in harmonic approximation), altering codon energy landscapes (Monroe 2024, Finol 2024). Concurrently, the methyl group (-CH3) group in m1ψ may destabilize its tautomeric equilibrium, shifting hydrogen positions and double bonds relative to uridine, a nucleotide absent in human biology (Borchardt 2020, Martinez 2022, Sponer, 1994, Santiago 2023, Malesu 2023). This could perturb base pairing and ribosomal recognition, amplifying the modification’s intended effects on mRNA stability and immunogenicity (Santiago 2024).

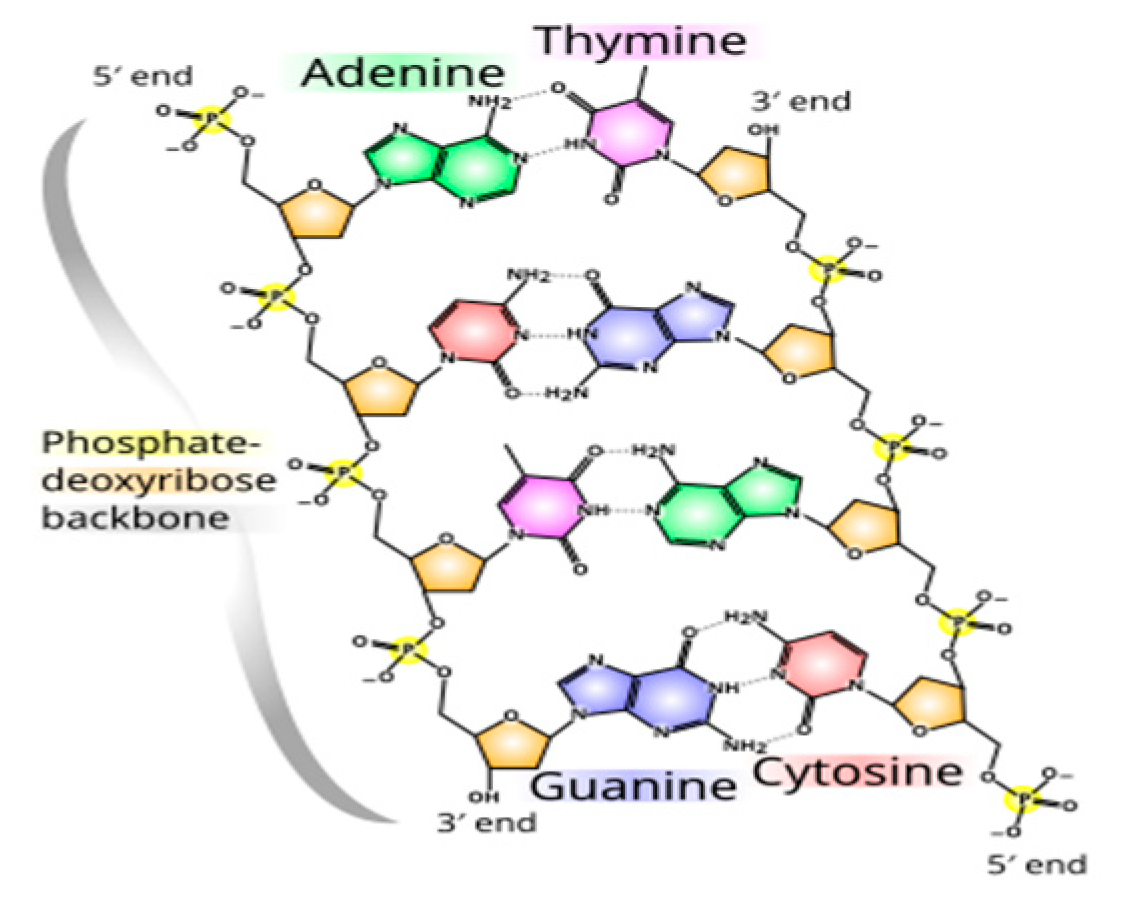

Tautomerism, driven by hydrogen’s mobility, is sensitive to mass and the environment (e.g., temperature, pH). Uridine’s keto form dominates, but m1ψ’s methyl substitution may favor alternative tautomers, (e.g., an enol-like state), altering hydrogen bonding patterns (Sponer 1994, Borchardt 2020, Martinez 2022). Adenine-uridine pairs form two hydrogen bonds, while guanine-cytosine pairs form three (

Figure 1, Wiki 2025); m1ψ’s tautomeric shift might mimic cytosine-like pairing, disrupting codon fidelity. Such mispairing elevates the activation energy (E

a) of translation, per k=Ae

−Ea/RT (where k is the rate constant, A is the pre-exponential factor, R=8.314 J/mol K, T≈310 K. A ΔE

a of 1–5 kJ/mol, from vibrational or tautomeric effects, slows k, extending translation time (t=E/P, where P from ATP hydrolysis) and aligning with +1 frameshifting (Mulroney 2023).

Figure 1.

Hydrogen bonds differences. Adenine to Thymine has two hydrogen bonds. Guanine to Cytosine. (Wiki 2025, Saenger, 1984).

Figure 1.

Hydrogen bonds differences. Adenine to Thymine has two hydrogen bonds. Guanine to Cytosine. (Wiki 2025, Saenger, 1984).

Hydrogen’s role escalates via quantum tunneling, where its low mass enables penetration of energy barriers (Lambert 2013, Wild 2023). In the ribosomal active site, tautomeric fluctuations—potentially enhanced by m1ψ’s methyl group, may facilitate hydrogen tunneling, bypassing classical Ea limits and misdirecting tRNA selection (Noller 2005). This quantum interplay, rooted in E=mc2 and E=hf, couples with k=Ae−Ea/RT and t=E/P to disrupt processivity, increasing aberrant protein risks (Nance 2021, Mulroney 2023). Frameshifting data suggest tautomer-driven errors compound mass-energy effects, challenging spike protein consistency across doses (Mulroney 2023, ,Sponer 1994).

I propose that m1ψ-modified mRNA leverages tautomerism and tunneling to alter translation dynamics. The mass-energy shift (ΔE=hΔf) and tautomeric instability elevate codon energy, while tunneling accelerates or skews peptide bond formation, fragmenting classical timing (Demongeot 2023, Schramm 2011). Flooding cells with high-frequency mRNA templates lowers Ea for synthesis but risks errors—evidenced by variable protein output (Nance & Mier 2021). Testable via Markov models or IR/Raman spectroscopy to probe Δf and tautomeric states, this positions mRNA technology as a quantum biology frontier, necessitating rigorous study of its cellular impacts (Klinman 2013, Nance 2021).

Energy-Frequency Relationship Molecular Systems

The Planck-Einstein relation, E=hf, ties a molecule’s energy (E) to its vibrational frequency (f), with Planck’s constant (h=6.626×10−34 J*s) bridging the quantum and molecular scales. In biological systems, unlike nuclear reactions where mass converts to vast energy, subtle energy shifts drive processes like protein synthesis. Ribosomes decode codons at a rhythmic pace, approximately 2–5 amino acids in eukaryotes (Alberts 2002), a frequency potentially disrupted by nucleotide modifications. Here, the ribosome "reads" codons at a characteristic frequency, a tempo, that nucleotide modifications like N1-methylpseudouridine (m1ψ) can alter. With m1ψ’s ~14 Da mass increase (~258 Da vs. uridine’s 244 Da), its vibrational frequency (f) drops, reducing energy per mode per E=hf. The Arrhenius equation, k=Ae−Ea/RT, further suggests that m1ψ’s steric bulk raises the activation energy (Ea), slowing translation rates (k) and potentially skewing ribosomal efficiency.

This energy-frequency interplay can be extended through the concept of power (P=E/t), where time (t=E/P) reflects the duration over which energy is delivered or dissipated in these molecular events. In ribosomal translation, E might represent the energy tied to molecular vibrations or bond formation, while P captures the rate at which this energy drives the reaction forward. For m1ψ, a lower f (from increased reduced mass) reduces E, and a higher Ea (from steric hindrance) decreases P, elongating t, the time required for translation.(Finol 2024) This aligns with observed slowdowns in reaction rates and hints at mistranslation risks, as the ribosome "clock" is disrupted. Compare this to vitamin D: D3 (cholecalciferol, 384.64 g/mol) outlasts D2 (ergocalciferol, 396.64 g/mol) due to structural differences affecting receptor binding and half-life (15 days vs. 3 days), showing how small mass shifts ripple into temporal and functional outcomes. (Hollis 1996, Jones 2014) The chemical formulas of D3 (C27H44O) and D2 (C28H44O).

The Arrhenius pre-exponential factor (A) ties into this by representing the frequency of molecular collisions with proper orientation, a proxy for f in a reaction context. Though molecular weight isn’t explicit in k=Ae−Ea/RT, it indirectly shapes A via collision theory. Heavier molecules, like m1ψ, increase reduced mass, a harmonic quantity simplifying two-body interactions, lowering collision frequency and thus A. This parallels the t=E/P lens: reduced P (slower energy transfer) extends t, reinforcing the mass-frequency-energy nexus. Finol (2024) notes m1ψ’s UV absorbance drops ~40% at 260 nm (λmax= 272 nm) compared to uridine, signaling altered molecular properties that could further modulate E and P in mRNA dynamics.

Consider vitamin D again: D3’s longer half-life (up to 6 weeks from UV exposure vs. 3 weeks from supplements) reflects a slower energy dissipation rate (P), extending its biological t.( Heaney 2003) Similarly, m1ψ’s mass and steric effects might prolong ribosomal t, raising questions about protein fidelity. Tautomerism complicates matters further: the -CH₃ group in m1ψ may reposition hydrogens, promoting enol-like tautomers over uridine’s typical keto form. This shift modifies hydrogen bonding—potentially increasing from two A-U bonds to three G-C-like bonds—and elevates the energy state (E) of the system. (Martinez 2022)

Does substituting uridine with m1ψ, a non-natural nucleotide in eukaryotic mRNA, yield the same protein? (Santiago 2023, Santiago 2024, Malesu 2023) Santiago (2023, 2024) suggest that such modifications, by tweaking f, E, and P, could subtly but significantly reshape the delicate hum of molecular systems, where time, energy, and frequency converge, suggesting m1ψ’s mass and tautomeric effects ripple through ribosomal efficiency, not explosively, but as a quantum peculiarity. (Nance 2021)

Clock Defined by Nucleotide

A clock is a device designed to measure, track, and display time, utilizing mechanisms like mechanical systems (e.g., pendulums, springs), digital circuits, or atomic transitions. Time, expressed in units such as seconds, minutes, hours, days, and years, carries a rhythmic tempo. Oscillations—repetitive motions around an equilibrium position—echo this rhythm. In physical systems like a watch’s pendulum or spring, this oscillatory behavior drives timekeeping, with time providing a framework to quantify the period and frequency of these movements. Beyond this, the relationship t=E/P, where time (t) is energy (E) divided by power (P), reframes time as the duration over which energy is delivered or dissipated, offering a lens to connect physical and molecular rhythms.

Tautomerism, a chemical phenomenon, involves a compound existing in multiple interconvertible forms, or tautomers, typically through the relocation of a hydrogen atom and a shift between a single and adjacent double bond. This dynamic interconversion hints at a conceptual parallel to oscillation. Though not empirically established as a physical vibration, a theoretical mass-frequency relationship suggests tautomeric shifts resemble molecular oscillations.(Sponer 1994) Conventional timekeeping doesn’t directly measure an abstract duration but reflects oscillatory dynamics, e.g., a crystal vibration or a spring’s cyclic motion in a clock. The transition between physical states (e.g., spring’s compression and release) spans a defined interval, shaping our perception of time. Similarly, in tautomerism, time could be inferred from the rhythmic interplay of molecular forms. Here, t=E/P ties this to energy: the energy (E) of tautomeric states and the power (P) of their interconversion dictate the temporal scale of these chemical "oscillations."

Tautomerism’s impact extends to molecular genetics. For example, adding a functional group (e.g., -CH₃) alters hydrogen-bonding patterns and the timing of molecular events. In biological systems, tautomeric shifts might regulate temporal processes, akin to a chemical clock. While lacking the physical periodicity of a pendulum, tautomerism represents a dynamic oscillation between molecular states. This interplay can influence biological regulation, where the balance of tautomeric forms—modulated by nucleotide or codon substitutions—affects oscillatory activity and function. (Demongeot, 2023; Santiago, 2024) Enzymes, for instance, may exploit tautomerization to stabilize transition states, embedding this oscillation into catalytic or regulatory cycles (Jakubowski, 2018, Schramm 2011, Klinman 2013). Through t=E/P, a higher E (e.g., from structural changes) or lower P (e.g., slower interconversion) could extend t, altering the timing of these processes.

The Planck-Einstein relation, E=hf, links energy to frequency, mirroring a clock’s reliance on frequency—the rate of recurring events—to set its tempo. In daily life, this rhythmic "tick" aligns biological and environmental rhythms, coordinating activity. In molecular systems, an energy increase shifts the frequency of tautomeric interconversion, potentially speeding or slowing biological timing. Applying t=E/P, if E rises (e.g., due to tautomeric stabilization) while P (energy transfer rate) remains constant, t lengthens, suggesting a slower "tick" in molecular clocks. Conversely, a higher P accelerates the cycle, reducing t. Studies like Nance (2021) provide empirical backing, linking enhanced protein production to such energy-frequency dynamics, where tautomerism’s quantum-inspired oscillations tune biological outcomes

Timing Change

The energy of a molecule is tied to its frequency through E=hf, where h is Planck’s constant and frequency (f=1/t) reflects vibrational modes, while the Arrhenius equation, k=Ae−Ea/RT, links reaction rates to activation energy ( Ea). Introducing N1-methylpseudouridine (m1ψ) into mRNA increases its mass (~258 Da vs. uridine’s ~244 Da) with a methyl group (-CH₃), subtly lowering vibrational frequency (f). A reduced f means less energy per mode, potentially slowing molecular events. Additionally, m1ψ’s steric bulk may elevate Ea, decreasing reaction rates (k). In protein synthesis, where timing is critical, this shift could disrupt the ribosome’s rhythm, akin to swapping a high-voltage battery for a weaker one in a device, altering its performance. The expression t=E/P, where time (t) is energy (E) divided by power (P), further frames this: a lower E (from reduced f) or diminished P (energy transfer rate) extends t, stretching the temporal scale of translation. m1ψ’s ΔE, though small, sums across codons, raising E in t=E/P and slowing ribosomal ‘ticks’ cumulatively

Ribosomes assemble proteins at a steady pace—around 20 amino acids per second in bacteria, slower in humans at 2 to 5 amino acids per second—akin to a battery powering a clock’s precise. ticks (Alberts 2002, Cooper 2000) Substituting m1ψ for uridine could skew this tempo. A lower f from increased mass slows vibrational dynamics, while a higher Ea from steric hindrance raises energy barriers, potentially delaying translation steps. Here, t=E/P suggests that if E drops (via E=hf ) and P (the rate of energy delivery to peptide bond formation) decreases, t lengthens, disrupting the ribosome’s cadence. Studies indicate consequences: m1ψ in mRNA vaccines may trigger rare translation errors (Mulroney 2023), resonating with the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry’s focus on protein structure precision. (Nobel Committee for Chemistry (2024). Press Release, 9 October 2024) Slower k reduces successful translations per second, risking misfolded or aberrant proteins if timing falters.

Consider nucleotide mass changes. Table 2 in “A Closer Look at N1-methylpseudouridine in the Modified mRNA Injectables” shows m1ψ codons have higher molecular weight than uridine’s, altering their energy profile. Though encoding the same amino acids, m1ψ’s added mass and steric effects might affect ribosomal efficiency.(Mulroney 2023, Monroe 2024) Energy, mass, and frequency interlink (E=hf, f=1/t): a heavier molecule with lower f extends t, potentially shifting protein output. Through t=E/P, m1ψ’s mass lowers f (reducing E), possibly raises Ea (lowering P), and slows k, yet quantum tunneling might accelerate peptide bond formation by bypassing barriers. (Klinman, 2013) This tension, slower vibrational dynamics vs. faster catalysis, disrupts ribosomal timing. Frameshifting (Mulroney 2023) suggests this altered rhythm risks protein fidelity, a subtle but profound shift akin to a clock ticking out of sync.

Exact shifts in f or Ea from m1ψ require computational chemistry, accounting for bond stretching, angle bending, and steric interactions. (Verdolino 2008, Kalra 2020, Thapa 2015) Simulations of m1ψ’s vibrational spectra could estimate f changes, as Verdolino (2008) did for nucleobases. These studies show molecular energy varies with structure and conditions, so precise values demand further data, like vibrational spectra or reaction simulations. Qualitatively, m1ψ’s mass and bulk likely slow molecular “ticks” (t=1/f), and with t=E/P, a reduced P (from higher Ea) amplifies this, tweaking the body’s biochemical rhythm. It’s a small adjustment with potentially big ripples, much like a weaker battery altering a gadget’s speed.

Using m1ψ in mRNA technology adjusts the body’s molecular clock, prompting questions about long-term effects. It’s not a dramatic upheaval but a subtle shift, lower frequency, altered t via E/P, that might influence protein fidelity. More research is needed to clarify these dynamics and ensure precision aligns with intent, given translation’s delicate balance.

Extending the Hypothesis to Mitochondrial Ribosomes

Mitochondrial ribosomes, tasked with synthesizing electron transport chain proteins, may respond to m1ψ’s mass shift in nuanced ways. If quantum tunneling optimizes their peptidyl transferase center (PTC), m1ψ could subtly alter energy dynamics (E=hf), potentially affecting ATP production efficiency, a hypothesis ripe for computational exploration. (Klinman 2013, Abdallat, 2024) The expression t=E/P, where time (t) is energy (E) divided by power (P), provides a framework: changes in E (via frequency shifts) or P (energy transfer rate) could reshape the temporal scale of mitochondrial translation, influencing cellular energy output.

The mass increase from m1ψ (~258 Da vs. uridine’s ~244 Da) mirrors the structural difference between vitamin D2 and D3 (396.64 g/mol vs. 384.64 g/mol), where a minor mass shift alters receptor binding and half-life. Similarly, m1ψ could subtly tweak mitochondrial ribosomal kinetics, potentially affecting translation efficiency akin to codon bias effects. (Finol 2024) Mitochondria rely on quantum frequency-driven energy states (E=hf) to channel ATP production, and m1ψ’s mass lowers vibrational frequency (f), reducing E. Through t=E/P, a lower E with constant P extends t, suggesting slower translation, though tunneling might counter this by boosting P. This interplay of quantum effects and biochemical kinetics in mRNA translation invites a rethinking of protein synthesis as a process shaped by physical principles beyond classical chemistry. This could guide future studies into cellular energy dynamics. For example, are ATP yields altered in m1ψ treated cells?

At the cellular level, energy fuels metabolism and homeostasis, and disruptions like mitochondrial stress from viral RNA can impair health. (Duan, 2025, Engel, 2007, Shang, 2022) Could mRNA vaccine sequences mimicking SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA, with m1ψ substitutions, amplify mitochondrial stress? If m1ψ alters mitochondrial ribosomes, a shift in t=E/P, where E drops (lower f) or P varies (via tunneling or steric effects), might adjust ATP efficiency, a possibility yet unexplored. This subtle energy shift, amplified in a mitochondrial context, warrants investigation.

Extending this hypothesis, quantum tunneling, protons or electrons bypassing micro-barriers in the mitoribosomal PTC, may optimize peptide bond formation, akin to effects in photosynthetic and enzymatic systems. (DeVault, 1966) The PTC, central to forming electron transport chain proteins, ties mitochondrial function to translation timing. Here, t=E/P frames the duality: a lower f (from m1ψ’s mass) reduces E, potentially lengthening t, while tunneling could increase P, shortening t. This tension suggests a disrupted molecular rhythm with broader implications.

Conditional Directions

m1ψ’s impact depends on cellular context: its mass may slow translation (higher Ea, lower f), while tunneling could accelerate it. First, the increased mass lowers vibrational frequency (E=hf) and raises activation energy (Ea per Arrhenius), suggesting slower timing. Through t=E/P, a reduced E and lower P (from steric hindrance) extend t, potentially outweighing tunnelling’s acceleration. This aligns with m1ψ’s primary role in stability, yet its steric arrangement disrupts fit, leading to frameshifting. (Mulroney 2023, Demongeot 2023) Second, quantum tunneling in codon-optimized mRNA might boost P bypassing classical rate limits, shortening t and enhancing protein production, countering the mass-induced frequency drop. Thermal noise may amplify m1ψ’s weak energy shift, akin to stochastic resonance, increasing tunneling or error rates unpredictably. (Gammaitoni 1998)

This altered timing reflects a disrupted “molecular clock.” Mass lowers f (E=hf ), stretching t if P remains constant, while tunneling adjusts P, shifting kinetics (Arrhenius equation) unpredictably. The net effect, slower or faster t depending on context, disturbs vibrational harmony and translation fidelity, as seen in frameshift errors. (Mulroney, 2023) Thus, t=E/P underscores how m1ψ’s energy shifts ripple through mitochondrial ribosomes, urging nuanced study of its biological role.

Deuterium Design

Investigations into the quantum mechanisms in mitochondria could reveal that altering cellular energy reshapes the quantum nature of cellular machinery. Deuterium’s heavier mass (~2 Da vs. hydrogen’s 1 Da) reduces tunneling efficiency due to its increased reduced mass, impacting quantum processes. (Hay 2012, Klinman 2013)Theoretically, replacing hydrogen with deuterium in m1ψ-modified mRNA could amplify frequency shifts (E=hf), lowering vibrational frequency (f) and slowing translation, thus highlighting mass’s role in ribosomal timing. The expression t=E/P, where time (t) is energy (E) divided by power (P), offers insight: deuterium’s mass reduces E (via lower f), and if P (energy transfer rate) remains constant or decreases due to diminished tunneling, t extends, elongating the temporal scale of protein synthesis. This could amplify m1ψ’s existing mass effect (~258 Da vs. uridine’s ~244 Da), providing a controlled test of how quantum and mass-driven dynamics interplay in mitochondrial ribosomes, with implications for cellular energy efficiency.

Conclusion

Reality can be viewed from various perspectives, each offering a unique viewpoint. “Trust the science” isn’t a monolith to blindly accept; claiming full understanding of complex systems like the mRNA platform suggests a shallow grasp of their intricacies.

“If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.”

— Richard Feynman

Energy fluctuations matter across scales. In protein folding, the energy landscape dictates the final shape; disruptions, possibly from quantum tunneling altering reaction rates, might lead to misfolded proteins, a factor in diseases like Alzheimer’s or prion disorders. At the cellular level, energy drives metabolism and homeostasis, and disruptions, such as mitochondrial stress from viral RNA, can impair health. (Duan, 2025; Shang, 2022) Could m1ψ’s energy shifts amplify such risks? Through t=E/P, a lower E (from reduced f due to m1ψ’s mass) or altered P (via tunneling or steric effects) might shift t, subtly disrupting biological timing. While direct evidence linking m1ψ to disease is elusive, this question merits exploration.

Even in nature, synonymous codons subtly vary in translation behavior due to codon bias, affecting folding or speed. (Shabalina 2013, Quax 2015) m1ψ’s synthetic tweak might exaggerate this, raising a broader point: small changes in the genetic code ripple outward. mRNA technology bends this code intentionally, but at what cost? Frameshifting and energy shifts suggest incomplete control, urging caution as we probe consequences. Here, t=E/P frames the balance: m1ψ’s increased mass lowers f (E=hf), potentially extending t if P drops, while tunneling could increase P, shortening t. This duality, slower vibrational dynamics versus faster catalysis, disrupts ribosomal timing unpredictably.

The implications are clear: mass may slow vibrational dynamics, while tunneling could accelerate catalysis; their balance awaits testing. Substituting m1ψ for uridine increases nucleotide mass, lowering vibrational frequency (E=hf) and potentially raising activation energy (Ea) per the Arrhenius equation (k=Ae−Ea/RT), stretching t if P decreases. This quantum-inspired shift, evidenced by frameshifting, suggests mRNA technology alters biological rhythms. (Nance 2021, Mulroney 2023) Without direct data, computational models or spectroscopic analysis could test this, using t=E/P to quantify how energy and power dynamics shape timing, ensuring precision in synthetic biology’s bold leap.

Clarifications

The human cell, a marvel of biological complexity, is often likened to a microscopic universe. Each cell contains about 100 trillion atoms, organized into proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids. The human genome, with approximately 3 billion DNA base pairs, encodes around 20,000-25,000 genes that orchestrate cellular functions. (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2004) These genes direct the production of over 100,000 distinct proteins via transcription and translation, regulated by feedback loops. The cytoplasm hosts organelles like mitochondria (100 to 1,000 per cell, depending on type), the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and lysosomes, all working to sustain life. This complexity is heightened by the cell's ability to communicate, adapt, and self-regulate through signaling pathways and molecular interactions, akin to a modern city. In essence, the human cell exemplifies nature's capacity to pack vast functionality into a space just 10-100 micrometers wide, mirroring the principles of quantum mechanics, where mass-energy equivalence (E=mc2) governs the subatomic world. (Alberts 2002)

1-Mass-energy equivalence principle (E=mc2) applied to a specific mass increment suggests implications for codon energy at a quantum level, explored through nuclear scale references and biological effects.

Step 1: Verify the Calculation

-

Given:

- o

Δm≈14 Da (Dalton, or atomic mass unit), where 1 Da=1.660539×10−27 kg

- o

c=3×108 m/s (speed of light).

- o

E=mc2

Step 2: Contextualize the Statement: ΔE is nuclear-scale but serves as a reference; biological effects arise at 10−21 J scales via vibrational or tautomeric shifts. (Wolfenden 2001)

Mass increment (Δm≈1 Da): This could correspond to a small biochemical change, like adding a nucleotide or modifying a codon (a group of three nucleotides in DNA/RNA, with masses on the order of hundreds of Da).

Energy increase (ΔE≈1.5 x 10−10 J): This is tiny macroscopically (e.g., compared to a joule of heat) but significant in quantum systems, such as molecular vibrations or electronic transitions in biomolecules (where energies are often in the range of 10−20 to 10−10 J).

Codon energy: Codons relate to genetic coding, and subtle energy shifts could influence molecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding or conformational changes) without being "explosive" (i.e., not nuclear scale).

2-Reference

The statement bridges mass-energy equivalence (E=mc2) with quantum-scale biochemical effects. While no single source explicitly ties 10−11 J and 1 Da to "codon energy" in this exact phrasing, anchoring it in biophysical or biochemical literature that applies E=mc2 to small mass changes and their energy implications.

-

Lehninger, A. L., Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. (2005). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. 4th edition, W.H. Freeman.

- o

Why: This textbook covers bioenergetics and the energetics of biochemical reactions, including the role of small mass changes in molecular systems. Chapter 13 ("Bioenergetics and Biochemical Reaction Types") discusses energy changes in biological molecules, often on the order of 10−20 to 10−10 J (e.g., ATP hydrolysis yields ∼5×10−20 J per molecule). While it doesn’t directly invoke E=mc2 for codons, it provides a framework for energy scales in quantum/biochemical contexts.

- o

Relevance: The 1 Da mass change aligns with atomic/molecular mass differences (e.g., isotopic substitution or bond formation), and 10−11 J fits as a subtle energy shift, consistent with "negligible macroscopically but significant quantum-mechanically" claim.

3- Amplification of Minute Energy Scales at the Ribosomal Level

This article posits that replacing uridine (~244 Da) with m1ψ (~258 Da) in mRNA introduces a mass increment (Δm ≈ 14 Da), yielding a tiny energy increase via E=mc2 (where c=3×108 m/s). This ΔE ≈ 2.0922791 x 10-9 J per molecule is minuscule, orders of magnitude smaller than thermal energy at physiological temperature (kT ≈ 4.14 × 10⁻²¹ J at 310 K, or ~2.5 kJ/mol). Critics might dismiss this as biologically irrelevant, yet at the ribosomal level, subtle energy shifts can amplify through cooperative effects or stochastic resonance, influencing translation dynamics in ways not immediately apparent from raw magnitude.

4-Cooperative Effects

Ribosomal translation is a highly cooperative process involving multiple molecular components—mRNA, tRNAs, ribosomal subunits, and accessory proteins—operating in concert. Small energy perturbations, like those from m1ψ’s mass or tautomeric shifts, could propagate across a system, altering its energy landscape collectively. For instance:

Vibrational Frequency Shifts: Per E=hf, m1ψ’s increased mass lowers its vibrational frequency (f∝1/√m in a harmonic oscillator approximation). Even a slight reduction in f (e.g., a few cm⁻¹ in vibrational modes) decreases energy per mode by a small amount (~10⁻²¹ J). Across thousands of codons in an mRNA molecule, this aggregates, subtly raising the total energy barrier (E) for translation.

Tautomeric Influence: m1ψ’s methyl group may favor enol-like tautomers over uridine’s dominant keto form, shifting hydrogen bonding (e.g., from two A-U bonds to three G-C-like bonds). This alters base-pairing stability by ~1–5 kJ/mol (comparable to hydrogen bond energies). In a ribosome processing hundreds of codons, these incremental changes compound, increasing the activation energy (Ea) in the Arrhenius equation (k=Ae−Ea/RT), slowing the rate constant (k) collectively.

Ribosomal Processivity: The ribosome’s stepwise movement relies on synchronized conformational changes powered by ATP/GTP hydrolysis. A higher Ea from m1ψ could delay tRNA selection or translocation, amplifying across multiple steps. If t=E/P (time per step = energy barrier / power), a modest E increase (e.g., 1 kJ/mol) with constant P (~10⁻¹⁹ W) extends t by ~0.01 s per codon. Over a 1,000-codon protein, this becomes a ~10 s delay—significant for cellular timing.

This cooperative amplification resembles how weak interactions in protein folding (e.g., hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces) collectively dictate a stable tertiary structure. Though ΔE from E=mc2 (e.g., 2.1 x 10-9 J for 14 Da) is nuclear scale, biological effects at 10-21 J scales amplify across a translating ribosome, potentially tipping the system into detectable errors, like the +1 frameshifting observed by Mulroney et al. (2024).

5- Stochastic Resonance

Stochastic resonance offers another amplification mechanism, where random noise enhances weak signals in nonlinear systems. The ribosome operates in a noisy cellular environment, with thermal fluctuations (~kT) dwarfing m1ψ’s ΔE. However:

Subthreshold Signal Boost: The minute energy shift from m1ψ (e.g., via lower f or higher Ea) acts as a weak periodic signal. Thermal noise, typically disruptive, can stochastically align with this signal, pushing the ribosome past energy barriers it might otherwise fail to cross. This could paradoxically increase tunneling efficiency or tRNA mis selection, amplifying m1ψ’s impact.

Frameshifting Example: Frameshifting requires the ribosome to slip by one base, a rare event needing precise timing. A lower f (slower molecular “ticks”) might desynchronize ribosomal steps, and noise could amplify this mismatch, raising error rates. If P (energy delivery rate) fluctuates, t=E/P varies stochastically, making frameshifts more likely when noise peaks align with m1ψ’s altered energy profile.

Quantum Tunneling Context: Klinman & Kohen (2013) note that hydrogen tunneling in enzymes leverages thermal vibrations to optimize barrier crossing. m1ψ’s tautomeric shifts could modulate hydrogen positions, enhancing tunneling probability in the peptidyl transferase center. Noise amplifies this subtle quantum effect, skewing peptide bond formation timing unpredictably.

In stochastic resonance, the signal (m1ψ’s ΔE) need not exceed noise (kT); their interplay suffices to shift system behavior. This could explain how a negligible ΔE translates into measurable biological outcomes, like aberrant proteins, without requiring massive energy input.

Integration with t=E/P

The t=E/P model ties these mechanisms together:

Cooperative Effects: A collective E increase (from aggregated Δf or ΔEa) raises t if P (ATP-driven power) remains fixed, slowing translation linearly with codon number.

Stochastic Resonance: Noise modulates P, making t fluctuate. When noise amplifies m1ψ’s signal, P may spike (reducing t) or drop (extending t), driving erratic timing that manifests as frameshifts or mistranslations.

6-Biological Relevance

While ΔE=2.09227914 × 10⁻⁹ J (from Δm≈ 14 Da, via E=mc2) illustrates a quantum-scale energy shift, ribosomes operate at a nanoscale where single-molecule events matter, with energies closer to kT=4.28×10−21 J. A 1–5 kJ/mol Ea shift (0.39–1.94 kT) is plausible for steric or tautomeric effects of m1ψ and aligns with enzymatic barriers (Wolfenden, 2001). Cooperative amplification across codons and stochastic enhancement via noise make this biological scale significant, affecting protein fidelity or mitochondrial ATP output over time.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the author used Copilot, Grok 3 to highlight grammar and punctuation. After using this tool/service, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Abdallat, M.; Qaswal, A.B.; Eftaiha, M.; Qamar, A.R.; Alnajjar, Q.; Sallam, R.; Kollab, L.; Masa’deh, M.; Amayreh, A.; Mihyar, H.; et al. A mathematical modeling of the mitochondrial proton leak via quantum tunneling. AIMS Biophysics 2024, 11, 189–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science.

- Berg, J.M.; Tymoczko, J.L.; Stryer, L. (2002). Biochemistry. 5th edition, Chapter 13: "Bioenergetics and Biochemical Reaction Types. ": Chapter 13.

- Borchardt, E.K.; Martinez, N.M.; Gilbert, W.V. Regulation and function of RNA pseudouridylation in human cells. Annual Review of Genetics 2020, 54, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, G.M. (2000). Transport of Small Molecules. In The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9847/.

- Demongeot, J.; Fougère, C. mRNA COVID-19 vaccines—Facts and hypotheses on fragmentation and encapsulation. Vaccines 2023, 11, Article 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVault, D.; Chance, B. Studies of photosynthesis using a pulsed laser: I. Temperature dependence of cytochrome oxidation in Chromatium. Biophysical Journal 1966, 6, 825–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Liu, R.; Lan, W.; Liu, S. The essential role of mitochondrial dynamics in viral infections. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.S.; Calhoun, T.R.; Read, E.L.; Ahn, T.-K.; Mančal, T.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Blankenship, R.E.; Fleming, G.R. Evidence for wavelike energy transfer through quantum coherence in photosynthetic systems. Nature 2007, 446, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finol, E.; Krul, S.E.; Hoehn, S.J.; Lyu, X.; Crespo-Hernández, C.E. The mRNACalc webserver accounts for the N1-methylpseudouridine hypochromicity to enable precise nucleoside-modified mRNA quantification. Molecular Therapy: Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammaitoni, L.; Hänggi, P.; Jung, P.; Marchesoni, F. Stochastic resonance. Reviews of Modern Physics 1998, 70, 223–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, S.; Scrutton, N.S. Pressure effects on enzyme-catalyzed quantum tunneling events arise from protein-specific structural and dynamic changes. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134, 9749–9754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P.; Davies, K.M.; Chen, T.C.; Holick, M.F.; Barger-Lux, M.J. Human serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol response to extended oral dosing with cholecalciferol. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2003, 77, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, B.W. Assessment of vitamin D nutritional and hormonal status: What to measure and how to do it. The Journal of Nutrition, 1996, 126 Suppl.4, 1228S–1234S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J. (2001). Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton. Sinauer Associates.

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 2004, 431, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H.; Flatt, P. (2018, December 2). 6.1: How Enzymes Work. Biology LibreTexts. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Biochemistry/Fundamentals_of_Biochemistry_(Jakubowski_and_Flatt)/01%3A_Unit_I-_Structure_and_Catalysis/06%3A_Enzyme_Activity/6.01%3A_How_Enzymes_Work.

- Jones, G.; Prosser, D.E.; Kaufmann, M. Cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of vitamin D. Bone 2014, 59, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, K.; Gorle, S.; Cavallo, L.; Oliva, R.; Chawla, M. Occurrence and stability of lone pair-π and OH–π interactions between water and nucleobases in functional RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 48, 5825–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinman, J.P.; Kohen, A. Hydrogen tunneling links protein dynamics to enzyme catalysis. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2013, 82, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N.; Chen, Y.-N.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Li, C.-M.; Chen, G.-Y.; Nori, F. Quantum biology. Nature Physics 2013, 9, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesu, V.K. (2023, December 7). A step forward in vaccine technology: Exploring the effects of N1-methylpseudouridine in mRNA translation. News-Medical.net. https://www.news-medical.net/news/20231207/A-step-forward-in-vaccine-technology-Exploring-the-effects-of-N1-methylpseudouridine-in-mRNA-translation.aspx.

- Martinez, N.M.; Gilbert, W.V. Pre-mRNA modifications and their role in nuclear processing. Quantitative Biology 2018, 6, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, N.M.; Su, A.; Burns, M.C.; Nussbacher, J.K.; Schaening, C.; Sathe, S.; Yeo, G.W.; Gilbert, W.V. Pseudouridine synthases modify human pre-mRNA co-transcriptionally and affect pre-mRNA processing. Molecular Cell 2022, 82, 645–659.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, J.; Eyler, D.E.; Mitchell, L.; Deb, I.; Bojanowski, A.; Srinivas, P.; Dunham, C.M.; Roy, B.; Frank, A.T.; Koutmou, K.S. N1-Methylpseudouridine and pseudouridine modifications modulate mRNA decoding during translation. Nature communications 2024, 15, 8119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulroney, T.E.; Pöyry, T.; Yam-Puc, J.C.; Rust, M.; Harvey, R.F.; Kalmar, L.; Horner, E.; Booth, L.; Ferreira, A.P.; Stoneley, M.; et al. N1-methylpseudouridylation of mRNA causes +1 ribosomal frameshifting. Nature 2024, 625, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, K.D.; Meier, J.L. Modifications in an emergency: The role of N1-methylpseudouridine in COVID-19 vaccines. ACS Central Science 2021, 7, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobel Committee for Chemistry. (2024, October 9). The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2024 [Press release]. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2024/press-release/.

- Noller, H.F. RNA structure: Reading the ribosome. Science 2005, 309, 1508–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quax, T.E.; Claassens, N.J.; Söll, D.; van der Oost, J. Codon bias as a means to fine-tune gene expression. Molecular Cell 2015, 59, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodnina, M.V.; Fischer, N.; Maracci, C.; Stark, H. Ribosome dynamics and tRNA movement by time-resolved electron cryomicroscopy. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2017, 18, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenger, W. (1984). Principles of nucleic acid structure. Springer-Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Santiago, D. (2023, November). Future science series: “Unknown ingredients”: mXNA and the Kozak sequence with Daniel Santiago. Solari Report. https://home.solari.com/future-science-series-unknown-ingredients-mxna-and-the-kozak-sequence-with-daniel-santiago/.

- Santiago, D. A closer look at N1-methylpseudouridine in the modified mRNA injectables. International Journal of Vaccine Theory, Practice, and Research 2024, 3, 1345–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, V.L. Enzymatic transition states, transition-state analogs, dynamics, thermodynamics, and lifetimes. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2011, 80, 703–732. [Google Scholar]

- Shabalina, S.A.; Spiridonov, N.A.; Kashina, A. Sounds of silence: Synonymous nucleotides as a key to biological regulation and complexity. Nucleic Acids Research 2013, 41, 2073–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, J.; Ge, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, N.; Jin, N.; Li, Y.; Tian, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 causes mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy impairment. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 12, 780768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Meng, X.; Shi, K.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Lian, W.; Zhou, C.; Lyu, Y.; Chu, P.K. Hydrogen permeation barriers and preparation techniques: A review. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A 2022, 40, Article 060803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šponer, J.; Hobza, P. Tautomerism of uracil and 5-bromouracil: A combined ab initio quantum mechanical and statistical thermodynamic study. Journal of Physical Chemistry 1994, 98, 3161–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Schlegel, H.B. Calculations of pKa’s and redox potentials of nucleobases with explicit waters and polarizable continuum solvation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2015, 119, 5134–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdolino, V.; Cammi, R.; Munk, B.H.; Schlegel, H.B. Calculation of pKa values of nucleobases and the guanine oxidation products guanidinohydantoin and spiroiminodihydantoin using density functional theory and a polarizable continuum model. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2008, 112, 16860–16873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, R.; Nötzold, M.; Simpson, M.; Tran, T.D.; Wester, R. Tunnelling measured in a very slow ion-molecule reaction. Nature 2023, 615, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, M. (2013, June). Quantum tunneling in DNA [Unpublished manuscript]. Drexel University, Department of Physics. https://www.physics.drexel.edu/~bob/Term_Reports/Megan_Wolfe.pdf.

- Wolfenden, R.; Snider, M.J. The depth of chemical time and the power of enzymes as catalysts. Accounts of Chemical Research 2001, 34, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).