Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

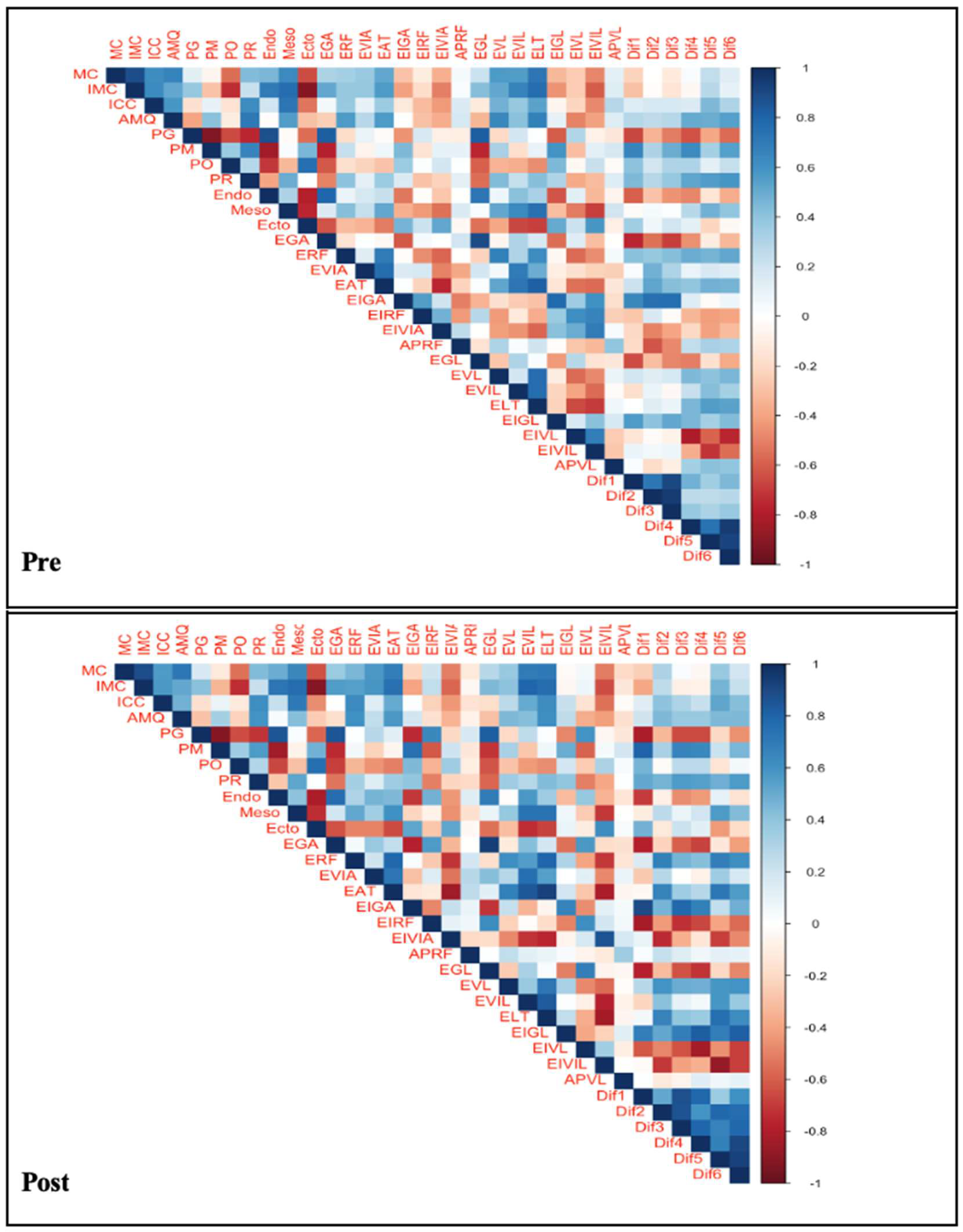

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Participants

Procedure

Strength Training

Anthropometric Measurements

Description of the Taking of the Main Anthropometric Measurements

Ultrasound Measurements

Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMQ | Cross-sectional section of the quadriceps |

| APRF | Pennation angle of the RF |

| APVL | Pennation angle of the VL |

| CT | Tomography |

| DAM | Median Absolute Deviation |

| DS | Standard deviation |

| Dif1 | Anterior fat EI minus RF EI |

| Dif2 | Anterior fat EI minus anterior VI EI |

| Dif3 | Anterior fat EI minus the average of RF EI + anterior VI EI |

| Dif4 | Lateral fat EI minus VL EI |

| Dif5 | Anterior fat EI minus lateral VI EI |

| Dif6 | Lateral fat EI minus the average of VL EI + lateral VI EI |

| DS | Standard Deviation |

| EAT | Total anterior thickness |

| EGA | Subcutaneous fat tissue thickness in the anterior region |

| EGL | Fat thickness in the lateral region |

| EI | Echo-intensity |

| EIGA | EI of subcutaneous fat tissue in the anterior region |

| EIGL | EI of subcutaneous fat tissue in the lateral region |

| EIRF | EI of the RF |

| EIVIA | EI of the VI in the anterior region |

| EIVIL | EI of the VI in the lateral region |

| EIVL | EI of the VL |

| ELT | Total lateral thickness |

| ERF | Thickness of the RF |

| EVIA | Thickness of the VI in the anterior region |

| EVIL | Thickness of the VI in the lateral region |

| EVL | Thickness of the VL |

| ICC | Waist-to-hip ratio |

| IMC | Body mass index |

| M | Mean |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| n | Sample size |

| US | Ultrasound |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| 1RM | One-repetition maximum |

References

- Hyde, P.N.; Kendall, K.L.; Fairman, C.M.; Coker, N.A.; Yarbrough, M.E.; Rossi, S.J. Use of B-Mode Ultrasound as a Body Fat Estimate in Collegiate Football Players. J Strength Cond Res 2016, 30, 3525–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarto, F.; Spörri, J.; Fitze, D.P.; Quinlan, J.I.; Narici, M.V.; Franchi, M.V. Implementing Ultrasound Imaging for the Assessment of Muscle and Tendon Properties in Elite Sports: Practical Aspects, Methodological Considerations and Future Directions. Sports Medicine 2021, 51, 1151–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzynski-Seymour, E.; Fisher, J.; Giessing, J.; Gentil, P.; Steele, J. Relationships and comparative reliability of ultrasound derived measures of upper and lower limb muscle thickness and estimates of muscle area from anthropometric measures. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizoo, D.; de Heide, L.J.M.; Emous, M.; van Zutphen, T.; Navis, G.; van Beek, A.P. Measuring Muscle Mass and Strength in Obesity: a Review of Various Methods. Obes Surg 2021, 31, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Love, M.O.; Seamon, B.A.; Teixeira, C.; Ismail, C. Ultrasound estimates of muscle quality in older adults: reliability and comparison of Photoshop and ImageJ for the grayscale analysis of muscle echogenicity. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.C.; San Millán, I. Validation of Musculoskeletal Ultrasound to Assess and Quantify Muscle Glycogen Content. A Novel Approach. Phys Sportsmed 2014, 42, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzocchi, A.; Filonzi, G.; Ponti, F.; Albisinni, U.; Guglielmi, G.; Battista, G. Ultrasound: Which role in body composition? Eur J Radiol 2016, 85, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Pascual, C.; Manonelles Marqueta, P.; Federación Española de Medicina del Deporte. Manual de cineantropometría; Nexus Médica, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Atencia Pérez, E.A.; Ricardo Paternina, D.A.; Vergara Villa, J.D. Relación del nivel de actividad física con variables asociadas a la composición corporal en estudiantes de primer ingreso del programa ciencias del deporte y la actividad física; CECAR. Corporación Universitaria del Caribe, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo, L.C. Body fat percentage and prevalence of overweight - obesity in college students of sports performance in Bogotá, Colombia. Nutrición Clínica y Dietética Hospitalaria 2016, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirazán Rodríguez, M.J.; Pirazán Rodríguez, M.J.; Rivera Santisteban, M.E.; Anzola Martínez, F. Efectos de un programa de entrenamiento concurrente sobre el perfil antropométrico y la fuerza muscular en un grupo de jóvenes universitarios. Revista Digital: Actividad Física y Deporte 2020, 6, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coratella, G.; Beato, M.; Milanese, C.; Longo, S.; Limonta, E.; Rampichini, S. Specific Adaptations in Performance and Muscle Architecture After Weighted Jump-Squat vs. Body Mass Squat Jump Training in Recreational Soccer Players. J Strength Cond Res 2018, 32, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa C, LaRoche D, Cadore E, Reischak-Oliveira A, Bottaro M, Kruel LF. 3 Different Types of Strength Training in Older Women. Int J Sports Med 2012, 33, 962–969. [CrossRef]

- Franchi, M.V.; Monti, E.; Carter, A.; Quinlan, J.I.; Herrod, P.J.J.; Reeves, N.D. Bouncing Back! Counteracting Muscle Aging With Plyometric Muscle Loading. Front Physiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó-Servat, A.; Ibarra, M.; Libran, M.; Escobar, L.; Perea, V.; Quirós, C. Prospective Study to Evaluate Rectus Femoris Muscle Ultrasound for Body Composition Analysis in Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó-Servat, A.; Ibarra, M.; Libran, M.; Quirós, C.; Puértolas, N.; Alonso, N. Usefulness of Ultrasound in Assessing the Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Body Composition: a Pilot Study. Obes Surg 2023, 33, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustani, K.; Kundisova, L.; Capecchi, P.L.; Nante, N.; Bicchi, M. Ultrasound measurement of rectus femoris muscle thickness as a quick screening test for sarcopenia assessment. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2019, 83, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechelli, F.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Stokes, M.; Agyapong-Badu, S. Validity of Ultrasound Imaging Versus Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Measuring Anterior Thigh Muscle, Subcutaneous Fat, and Fascia Thickness. Methods Protoc 2019, 2, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, C.M.M.; Heymsfield, S.B. Lean Tissue Imaging. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2014, 38, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, J.C.; Bouslah, M. Prediction of body fat in male athletes from ultrasound and anthropometric measurements versus DXA. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2020, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclos-Balica, M.; Muntean, P.; Schick, F.; Haragus, H.G.; Glisici, B.; Pupazan, V. Reliability of body composition assessment using A-mode ultrasound in a heterogeneous sample. Eur J Clin Nutr 2021, 75, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Anwar, M.; Hertwig, A.; Hahn, R.; Pesta, M.; Timmermann, I. Ultrasound method of the USVALID study to measure subcutaneous adipose tissue and muscle thickness on the thigh and upper arm: An illustrated step-by-step guide. Clin Nutr Exp 2020, 32, 38–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, M.S.; Thompson, B.J. Echo intensity as an indicator of skeletal muscle quality: applications, methodology, and future directions. Eur J Appl Physiol 2021, 121, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, A.U.; Harmon, K.K.; Burton, A.M.; Phan, D.C.; Mercer, N.E.; Lawless, N.W. Muscle strength, not age, explains unique variance in echo intensity. Exp Gerontol 2020, 139, 111047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.; Spitz, R.W.; Bell, Z.W.; Viana, R.B.; Chatakondi, R.N.; Abe, T. Exercise induced changes in echo intensity within the muscle: a brief review. J Ultrasound 2020, 23, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasenina, C.; Kataoka, R.; Hammert, W.B.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Dankel, S.J.; Buckner, S.L. Examination of Changes in Echo Intensity Following Resistance Exercise among Various Regions of Interest. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2022, 42, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J. The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application to Resistance Training. J Strength Cond Res 2010, 24, 2857–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernbom, M.; Augustsson, J.; Thomeé, R. The Influence of Frequency, Intensity, Volume and Mode of Strength Training on Whole Muscle Cross-Sectional Area in Humans. Sports Medicine 2007, 37, 225–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J. Science and development of muscle hypertrophy; Human Kinetics, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Stone, M.H. The Importance of Muscular Strength in Athletic Performance. Sports Medicine 2016, 46, 1419–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, M.V.; Reeves, N.D.; Narici, M.V. Skeletal Muscle Remodeling in Response to Eccentric vs. Concentric Loading: Morphological, Molecular, and Metabolic Adaptations. Front Physiol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proske, U.; Morgan, D.L. Muscle damage from eccentric exercise: mechanism, mechanical signs, adaptation and clinical applications. J Physiol. 2001, 537, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A. Fundamentals of Resistance Training: Progression and Exercise Prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004, 36, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatsiorsky, V.M.; Kraemer, W.J.; Fry, A.C. Science and practice of strength training; Human kinetics, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation; Geneva, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zermeño-Ugalde, P.; Gallegos-García, V.; Ramírez, R.A.C.; Gaytán-Hernández, D. Relación del índice cintura-estatura (ICE) con circunferencia cintura e índice de cintura cadera como predictor para obesidad y riesgo metabólico en adolescentes de secundaria. Rev Salud Pública Nutr 2020, 19, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000, 894, i253.

- Young, H.; Jenkins, N.T.; Zhao, Q.; Mccully, K.K. Measurement of intramuscular fat by muscle echo intensity. Muscle Nerve 2015, 52, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.S.; Darras, B.T.; Rutkove, S.B. Assessing spinal muscular atrophy with quantitative ultrasound. Neurology 2010, 75, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive statistics | Data |

|---|---|

| n 1 | 31 |

| Age (years) (M±DS) 1 | 22.3±4.14 |

| Height (meters) (M±DS) 1 | 1.73±0.08 |

| Body Mass (Kg)(Mediana±DAM) 1 | 69±13.64 |

| IMC (Kg/m2) (Mediana±DAM) 1 | 23.54±3.34 |

| Anthropometry (% fat) | Pre - n (%) | Post- n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Media | 21 (67.74) | 14 (45.16) | 0.0302 1 |

| Good | 1 (3.2) | 7 (22.6) | |

| Excellent | 9 (29.03) | 10 (32.25) | |

| Total | 31 (100) | 31 (100) |

| Ultrasound | Medium | DAM | Medium | DAM | p value* | Size of the effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | |||||

| EGA | 5.120 | 3.050 | 5.690 | 3.560 | 0.827 | 0.041 |

| ERF | 25.930 | 4.050 | 27.370 | 5.460 | 0.004 | 0.500 |

| EVIA | 20.450 | 2.940 | 21.000 | 3.460 | 0.158 | 0.255 |

| EAT | 48.060 | 6.910 | 49.080 | 7.410 | 0.005 | 0.484 |

| EIGA | 155.220 | 17.010 | 157.160 | 11.970 | 0.111 | 0.289 |

| EIRF | 116.290 | 18.160 | 112.050 | 9.610 | 0.182 | 0.243 |

| EIVIA | 90.050 | 15.880 | 90.380 | 13.670 | 0.999 | 0.000 |

| APRF | 15.120 | 4.560 | 17.000 | 2.620 | 0.055 | 0.345 |

| EGL | 5.060 | 3.230 | 5.600 | 3.290 | 0.812 | 0.044 |

| EVL | 24.320 | 4.180 | 25.120 | 4.040 | 0.035 | 0.377 |

| EVIL | 20.400 | 4.630 | 19.510 | 4.370 | 0.820 | 0.042 |

| ELT | 47.590 | 7.990 | 48.580 | 6.520 | 0.003 | 0.516 |

| EIGL | 151.590 | 10.900 | 155.480 | 9.980 | 0.135 | 0.271 |

| EIVL | 119.740 | 18.020 | 117.390 | 10.780 | 0.157 | 0.257 |

| EIVIL | 78.470 | 14.620 | 80.030 | 19.120 | 0.399 | 0.155 |

| APVL | 16.130 | 3.590 | 15.650 | 3.190 | 0.961 | 0.011 |

| Dif1 | 33.000 | 15.540 | 41.170 | 18.320 | <0.0001 | 0.686 |

| Dif2 | 67.170 | 15.400 | 71.730 | 21.280 | 0.224 | 0.222 |

| Dif3 | 49.110 | 14.060 | 55.630 | 13.730 | 0.002 | 0.524 |

| Dif4 | 30.780 | 24.940 | 37.920 | 19.890 | 0.001 | 0.560 |

| Dif5 | 79.520 | 13.800 | 84.100 | 23.020 | 0.854 | 0.035 |

| Dif6 | 56.650 | 19.270 | 59.770 | 21.540 | 0.157 | 0.257 |

| Stage | Days | % 1RM | Series | Repetitions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-3 | 60-70 | 4-5 | 10-12 | Bompa & Carrera (2015) [15] |

| 2 | 4-6 | 70-80% | 4-5 | 8-10 | Schoenfeld (201) [8] |

| 3 | 7-9 | 80-90% | 5-6 | 4-6 | Zatsiorsky & Kraemer (2020) [14] |

| 4 | 10-12 | 85-95% | 4-5 | 3-5 | Verkhoshansky (2009) [16] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).