1. Introduction

Many types of cells make up the human body. Every cell serves a distinct purpose. The body’s cells divide systematically in a controlled/regulated manner to produce new cells. The human body’s overall health and functionality are enhanced by these additional cells. Body cells proliferate uncontrollably when they are unable to divide in a controlled or regulated manner. Such unchecked tissue cell proliferation gives rise to a tumour, also known as a neoplasm. Brain tumours have the potential to compress important brain tissue structures [

1], significantly raise the risk of stroke due to abrupt blood vessel ruptures[

2], and ultimately result in death. A stroke can cause partial blindness, loss of balance, memory loss, speech difficulties, and irreversible paralysis of several important locomotory organs[

2]. A person’s current lifestyle choices, such as smoking, eating poorly, and being obese, as well as environmental and genetic variables, such as a family history of cancer or prolonged exposure to chemicals or radiation, can all be risk factors[

3].

Typically, tumours can be classified as malignant (cancerous) or benign (noncancerous)[

4,

5,

6]. Benign tumours do not develop or become malignant; they begin slowly in the brain and expand gradually. Tumours of this type are considered less dangerous because they are unable to spread to other areas of the body. This can be rapidly removed, but abnormal cell development may compress a section of the brain or adjacent tissues. On the other hand, malignant tumours are more likely to spread to other bodily areas, grow quickly, and lack clear boundaries. When this type of tumour begins in the brain, it is called a primary malignant tumour. A tumour that begins in one area of the body and travels to the brain is referred to as a secondary malignant tumor [

7,

8]. Meningiomas, gliomas, and pituitary tumours are the other common types of brain tumours.

Roughly thirty percent of intracranial tumours are meningiomas. There is a 1:2 male-to-female ratio, and the incidence rises with age, peaking in the seventh decade. Extraaxial in nature, these tumours originate from arachnoidal cells in the meninges rather than the brain parenchyma. By squeezing healthy tissues, they cause symptoms and indicators. The particular symptoms and indicators are contingent upon the meningioma’s anatomical location. For instance, meningiomas originating from the cerebral convexity may result in headaches, decreased cognition, and seizures, while meningiomas originating from the suprasellar region are more likely to induce optic atrophy, bitemporal hemianopia, and visual loss. Based on their histologic appearance, meningiomas are categorised into grades I, II, and III. A meningioma may be classified as a Grade I tumour (benign), Grade II tumour (atypical), or Grade III tumour (anaplastic/malignant) according to the WHO Classification System, depending on its severity and potential for metastasis[

9].

Overall 5-year survival rates for patients with benign, atypical, and malignant meningiomas were 70%, 75%, and 55%, respectively, in one sizable investigation based on information from the US National Cancer Database[

10]. In a more recent study, analysis of the SEER database, which included over 12,000 patients, showed that individuals with histologically confirmed nonmalignant meningiomas had 1- and 3-year survival estimates of 95.4% and 92.4%, respectively[

11].

On radiologic studies, meningiomas exhibit a characteristic look. Most meningiomas exhibit strong gadolinium enhancement and are isointense with grey matter on T1-weighted MRI studies. 60% of meningiomas have obvious peripheral edema, and 20% have accompanying bone abnormalities, either hyperostosis or destruction. MRIs are not as good at displaying the changes to the bone as CT scans are. Calcifications, central necrosis, or pseudocysts may be visible inside the tumour. A tumor’s prognosis is contingent upon a number of characteristics, including the tumor’s stage of identification, operability, patient age, growth location, and extent of metastasis. Each of these variables affects how the patient responds to radiation and chemotherapy, which in turn affects their chance of survival[

9].

Essential diagnostic factors are medical picture data obtained from various biomedical equipment using various imaging modalities. The technique known as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) finds radiofrequency pulses and magnetic flux vectors in the hydrogen atom nuclei of a patient’s water molecules. Since an MRI scan doesn’t use radiation, it is superior to a CT scan from a diagnostic standpoint. Radiologists may utilise MRI to evaluate the brain. Brain tumours can be found using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[

12,

13]. Furthermore, noise from operator participation in the MRI may lead to erroneous classification. Less expensive automated methods are required because of the enormous volume of MRI data that needs to be analysed. The automatic identification of cancers using magnetic resonance imaging is vital because working with human life requires a high degree of precision. Classifying MR images of the brain as normal or diseased can be done using supervised and unsupervised machine learning algorithm approaches. Quick classification of multi-class freely accessible MRI brain tumor datasets to enable real-time tumor identification without sacrificing fidelity is feasible[

14]. It is also becoming possible to utilize a different strategy that links tumor genetic variation with radiomic characteristics to engender a link between two fields of study that could be helpful for clinical disease management and improving patient benefits[

15]. Our paper offers an efficient automated solution to brain MRI data categorization using machine learning techniques. Classifying brain MR images is done using the supervised machine learning approach[

16,

17].

We’ve employed FLAIR (FLuid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery) structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) in this case. Using quantitative and qualitative rendering of different brain subregions, sMRI measures variations in the brain’s water constitution, which are represented as different shades of grey. These data are then utilised to depict and characterise the location and size of tumours. For effective skull stripping (three-dimensional views of brain slices, axial, coronal, and sagittal), FLAIR images guarantee that surrounding fluids are not magnetised and that signals from CSF (cerebro-spinal fluid) are suppressed[

18,

19,

20].

The following is a summary of this research work’s major contributions:

• This research proposes a novel approach that significantly advances the application of deep learning for medical diagnostics by employing a very deep transfer learning CNN model (VGG-16) enhanced by CUDA optimisation for the accurate and timely real-time identification of meningiomas.

• We’ve employed FLAIR (FLuid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery) structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) in this case. Using quantitative and qualitative rendering of different brain subregions, sMRI measures variations in the brain’s water constitution, which are represented as different shades of grey. These data are then utilised to depict and characterise the location and size of tumours. For effective skull stripping (three-dimensional views of brain slices, axial, coronal, and sagittal), FLAIR images guarantee that surrounding fluids are not magnetised and that CSF (cerebro-spinal fluid) is suppressed.

• The clinical implications of accurate brain tumor grading classification are significant, as they can inform treatment decisions and improve patient outcomes. Discussing the method’s integration into clinical workflows have offered insights into its practical applications and impact on patient care, enhancing the paper’s relevance to healthcare professionals.

• A comparison has been made with recent state-of-the-art technique research propositions in the literature survey.

2. Literature Survey

Imaging methods are fundamental to the treatment of cancer and are a great aid in the detection and management of cancers[

21,

22]. A promising new technique to profile tumours is radiomics, a quantitative approach to medical pictures that has the potential to provide more individualised care. In order to identify intricate patterns in tumour images that are invisible to the human eye, this method uses mathematical algorithms and artificial intelligence concepts[

23,

24,

25,

26]. Radiomic imaging properties may function as biomarkers to monitor and impact clinical endpoints, much like other big data techniques like genomes and proteomics[

27]. Radiomics has been shown to have potential in a variety of cancer types. Radiomic models have been applied to the prognostication of distant metastasis and survival, as well as the identification of cancer subtypes and molecular and genetic variants[

28].

Because of the subtle differences in diagnosis, risk assessment, and treatment strategy of meningioma, it is a great oncologic model system to study the use and development of radiomics in cancer care today[

29,

30,

31]. Traditionally, the World Health Organisation (WHO) grade has guided clinical decision-making for meningiomas[

32]. Though some high-grade meningiomas show indolent behaviour and may not recur, this grading scheme occasionally reveals significant diversity in tumour behaviour, with over 20% of low-grade meningiomas having an early recurrence[

33,

34,

35,

36]. This has raised interest in treating patients based on their molecular traits and growth rates[

37,

38,

39,

40]. Molecular platforms and testing are not always available, they incur additional costs, and they could only be able to detect a portion of a heterogeneous tumour in practice[

41,

42]. On the other hand, physicians who treat brain tumours have significantly easier access to imaging. Therefore, if image-based phenotyping can reach high reliability and reflects the biological characteristic and genetic signature of tumours, it has the potential to completely change the way patients can receive precision care.

Brain tumour segmentation is the process of dividing MRI scans into separate segments so that they may be understood more easily. The majority of recent research on CNN application has concentrated on GBM (Glioblastoma Multiforme) segmentation. Using the segmentation process, an image is divided into its individual pixels. This makes it easier to analyse the image and draw conclusions that are insightful. The necrotic core, edema, and enhancing tumour are among the parts of a tumour that this segmentation process correlates to. Since this segmentation entails the process of distinguishing sick tissues from healthy ones, it is essential for precise diagnosis and therapy planning[

43]. The initial step in recommending an appropriate course of treatment based on a patient’s response to radiation and chemotherapy is segmentation[

44].

For many years, radiotherapists have carried out these operations using manual segmentation.

Nonetheless, there was a significant likelihood of variation in the outcomes amongst observers and even within the same observer. The radiologist’s level of skill may have an impact on the laborious process[

45]. Segmentation techniques that are automated or semi-automatic have been developed to get around these restrictions. CNNs have been noted as one of the most effective training algorithms, despite processing enormous amounts of data at the expense of substantial computational expenses and complexity[

44]. Classification of brain tumours is essential for accurate patient diagnosis and care. However, obtaining appropriate classification is severely hampered by the scarcity of annotated data and the intricacy of tumour images. To increase the performance of brain tumour classification tasks, transfer learning has been a viable method in recent years for utilising pre-trained models on large-scale datasets[

46].

In order to improve brain tumour segmentation performance, a research study presented a novel hybrid strategy that blended convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with handmade characteristics. The MRI scans used in this investigation were processed to extract handmade features, such as texture, form, and intensity-based features. Concurrently, a novel CNN architecture was created and trained to automatically identify the features in the data. The handcrafted features and the features found by CNN in various pathways were blended with the suggested hybrid approach to create a new CNN. A range of assessment metrics, including segmentation accuracy, dice score, sensitivity, and specificity, were utilised in this study to gauge performance using the Brain Tumour Segmentation (BraTS) challenge dataset[

47]. In a separate investigation, the same research team created a Global CNN (GCNN) that included an additional CNN for MRI Pathways and a CNN for Confidence Surface (CS) Pathways, which handled CS modalities in conjunction with the provided ground truth. The aim of this work was to develop a deep convolutional architecture that is capable of efficiently handling different types of tumours, with the addition of manually created features[

48].

In medical imaging, brain tumour segmentation plays a crucial role in detection and therapy while protecting patient privacy and security. Advances in AI-based medical imaging applications are hampered by privacy rules and security issues that often impede data sharing in traditional centralised techniques. Federated learning (FL) was suggested by a research group as a means of addressing these issues. By training the segmentation model on distributed data from several medical institutions without requiring raw data sharing, the suggested approach allowed collaborative learning. Using the U-Net-based model architecture, which is well-known for its remarkable abilities in semantic segmentation tasks, this work highlighted how scalable the suggested method is for widespread use in medical imaging applications[

49].

A specific study has additionally taken into account three classification frameworks. The first model applies a fundamental CNN methodology, the second divides it into three categories of brain cancers (glioma, meningioma, and pituitary tumour), and there are two further models: one is normal, and the other exhibits a high degree of metastasis[

50]. According to severity, the brain tumour is categorised into three categories (categories I, II, and III) in the third model[

50].

Based on information from medical imaging tests, a different study team developed an evolutionary machine learning algorithm that successfully classifies brain tumour grades. This model, which is a modified version of the recently published Multimodal Lightweight XGBoost[

51], is called lightweight ensemble combines (weighted average and lightweight combines multiple XGBoost decision trees).

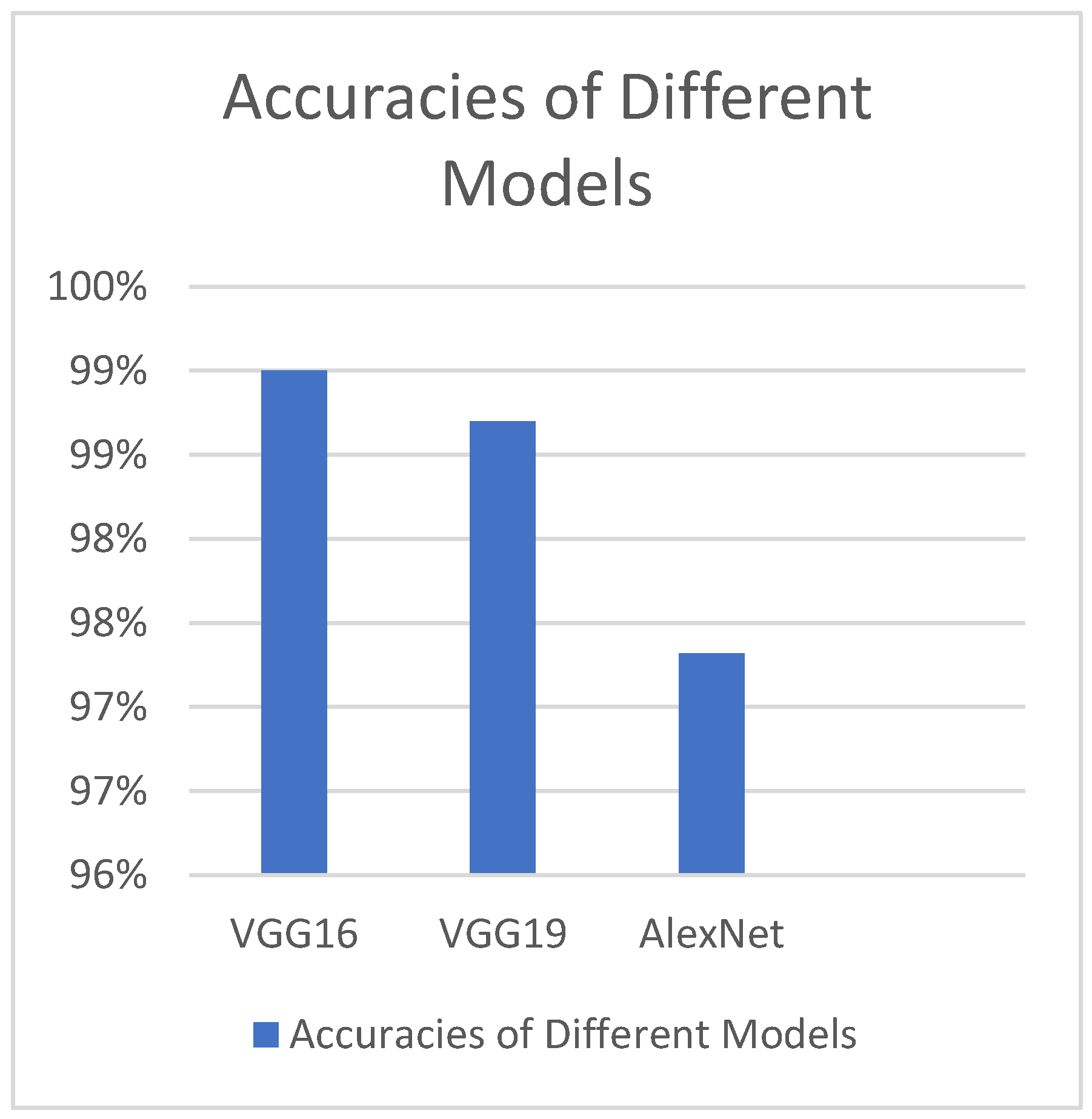

Different deep transfer learning techniques, such as GoogleNet, InceptionV3, AlexNet, VGG-16, and VGG-19, have been utilised by another study group to determine footprints; InceptionV3 has the best accuracy value but the largest time complexity (

Figure 1)[

52]. Additionally, it has been noted that, when compared to other models of a similar kind, the GoogleNet model has the steepest learning curve[

52].

An additional comparable model has been employed for the prediction of brain tumours, utilising the transfer learning techniques previously discussed. Additionally, an enhanced freeze strategy has been employed, which modifies the freeze Conv5-AlexNet layer to achieve superior outcomes[

53].

Rather than the widely utilised FLAIR images, some proposed study methodologies have used T1-weighted contrast MRI scan images[

8]. The application of multi-core GPUs, which generate image pixel matrix multiplication quickly and more efficiently even though it was found to be laborious and time-consuming[

54], has been a significant advancement in the categorization of brain tumours.

Radiomics-based image-based phenotyping has reinterpreted the role of medical imaging. A classic oncologic example that highlights the value of fusing artificial intelligence techniques with quantitative imaging data to enable precision therapy is meningioma. Globally, meningioma radiomics has increased due to new computational techniques and data accessibility. Research that enhances quality, creates extensive patient datasets, and conducts prospective trials is necessary to ensure translateability towards complicated tasks like prognostication[

55].

3. Methods

3.1. Justification for Choosing VGGNet CNN Model

Since it produces a greater level of accuracy than other deep CNN models like AlexNet, GoogleNet, etc., we have chosen to employ the VGGNet CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) model[

56]. With the aid of three extra 1 X 1 convolutional layers, VGG-16 achieves a 9.4% error rate, which is an improvement over the 9.9% error rate of the prior VGG-13 model[

57,

58]. Drawing from earlier research, VGGNet has achieved the best results on one of the most difficult datasets ever, the Caltech 256 dataset, which had 30607 photos in 256 different object categories. This model surpassed numerous others. VGGNet DNN models have been extensively utilised for image classification in a variety of prediction systems for malignancies of the lungs, skin, eyes, breasts, prostate, and other tissues within the past five years[

59,

60,

61,

62].

3.2. Architecture of VGGNet CNN Model

In our work we have used 2 Keras models in Python called VGG and Sequential models. VGGNet is a deep learning image pre-processing and classification CNN model which is an improvement from its predecessor, AlexNet(the first famous CNN)[

52]. The VGG network that we have constructed with very small convolutional filters consists of 13 convolutional layers and 3 fully connected layers.

Input: Our VGGNet model takes in an sMRI FLAIR image input size of 224×224.

Convolutional Layers: VGG’s convolutional layers leverage a minimal receptive field, i.e., 3×3, the smallest possible size that still captures up/down and left/right. Moreover, there are also 1×1 convolution filters acting as a linear transformation of the input. This is followed by a ReLU unit which is a piecewise linear function that will output the input if positive; otherwise, the output is zero. The convolution stride is fixed at 1 pixel to keep the spatial resolution preserved after convolution(stride is the number of pixel shifts over the input matrix).

Hidden Layers: All the hidden layers in our VGG network also use ReLU. VGG does not usually leverage Local Response Normalization(LRN) as it increases memory consumption and training time. Moreover, it makes no improvements to overall accuracy.

Fully-Connected Layers: The VGGNet has 3 fully connected layers. Out of the three layers, the first two have 4096 channels each, and the third has 1000 channels, 1 for each class.

No of Input Images: We have used segments of 264 3D FLAIR sMRI images belonging to 3 classes (meningioma, tuberculoma, normal). The reason for using limited number of images is because VGGNet is extremely computationally expensive and takes several days to train on NVIDIA GPU. We have considered implementing the model for larger than 5000 images in the future for effective generalization of the problem.

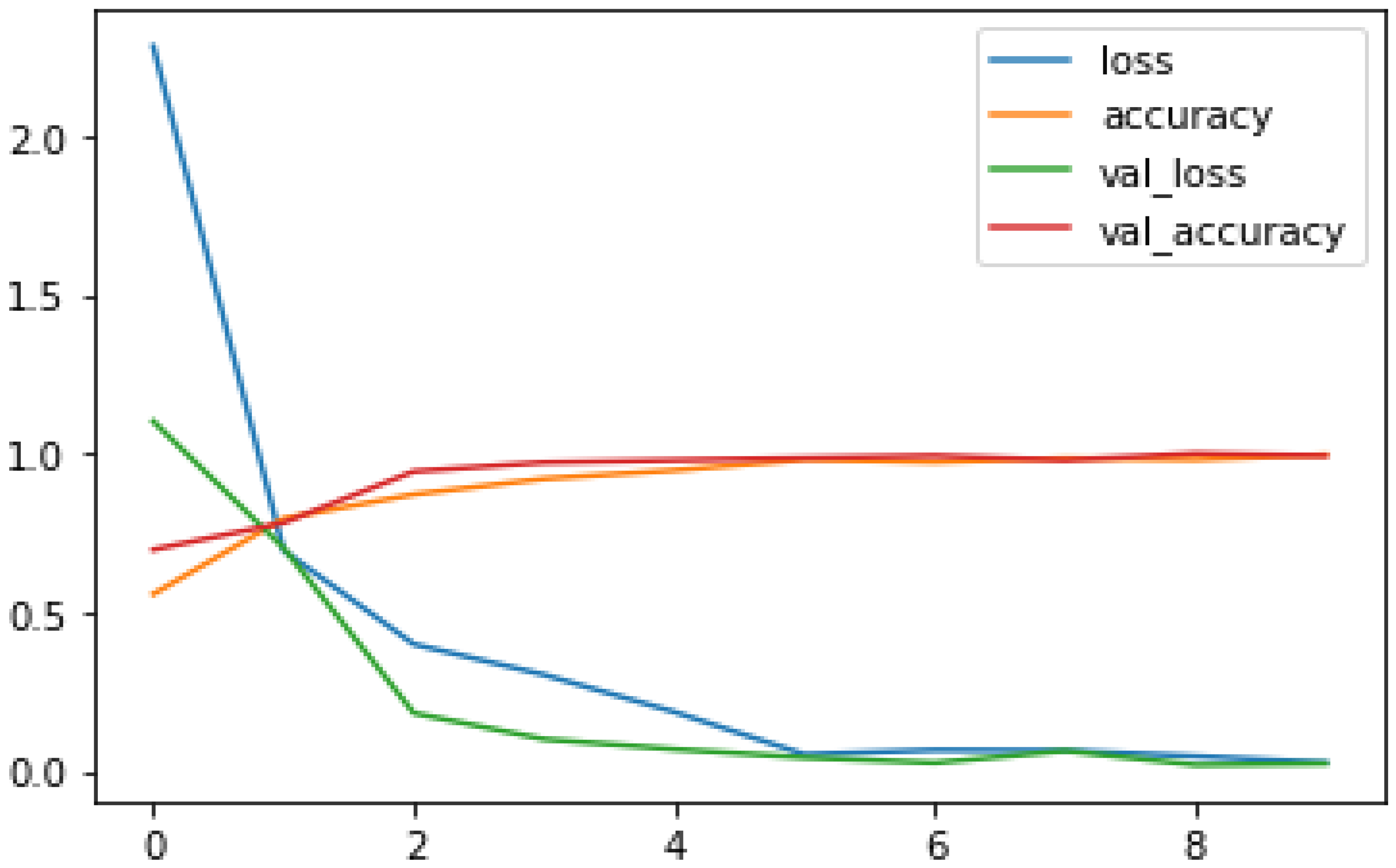

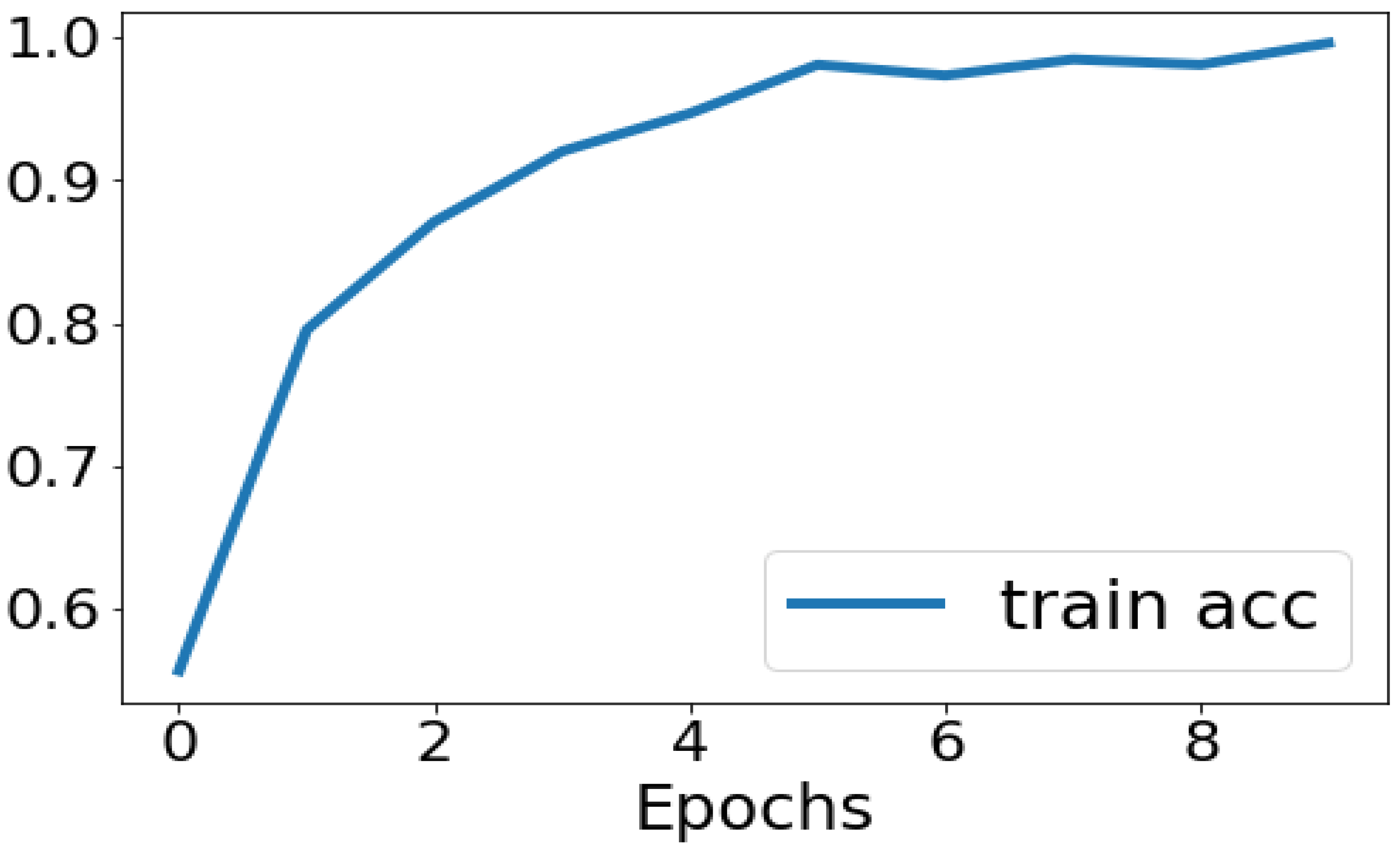

No of Epochs: The number of epochs in the Sequential Model has been set to 10(

Figure 3).

The Keras layers that we have used are Dense, Dropout, Flatten, Batch Normalization, ReLU.

In Keras, dense layers—also referred to as fully-connected layers—are the essential building blocks of neural networks. To add complexity, they first apply linear adjustments to the input data and then apply a non-linear activation function. In deep learning, dropout is a regularisation approach that helps avoid overfitting. During training, it randomly deactivates neurons, pushing the network to pick up more resilient properties. In order to prevent overfitting, the Dropout layer randomly sets input units to 0 at a frequency of rate at each step during the training period. It functions as an ensemble approach, enhances generalisation, streamlines training, and improves model performance on unknown data. Input data is reshaped into a one-dimensional array via the Keras “Flatten” layer, enabling neural network interoperability across convolutional and fully connected layers. Enhancing the model’s capacity for generalisation and stabilising the training process are the two main objectives of batch normalisation. Additionally, it may lessen the need for meticulous weight initialization of the model and permit the use of faster learning rates, both of which may expedite the training process. In neural networks, Rectified Linear Activation, or ReLU, is a popular activation function. It adds non-linearity, which facilitates the recognition of intricate patterns.

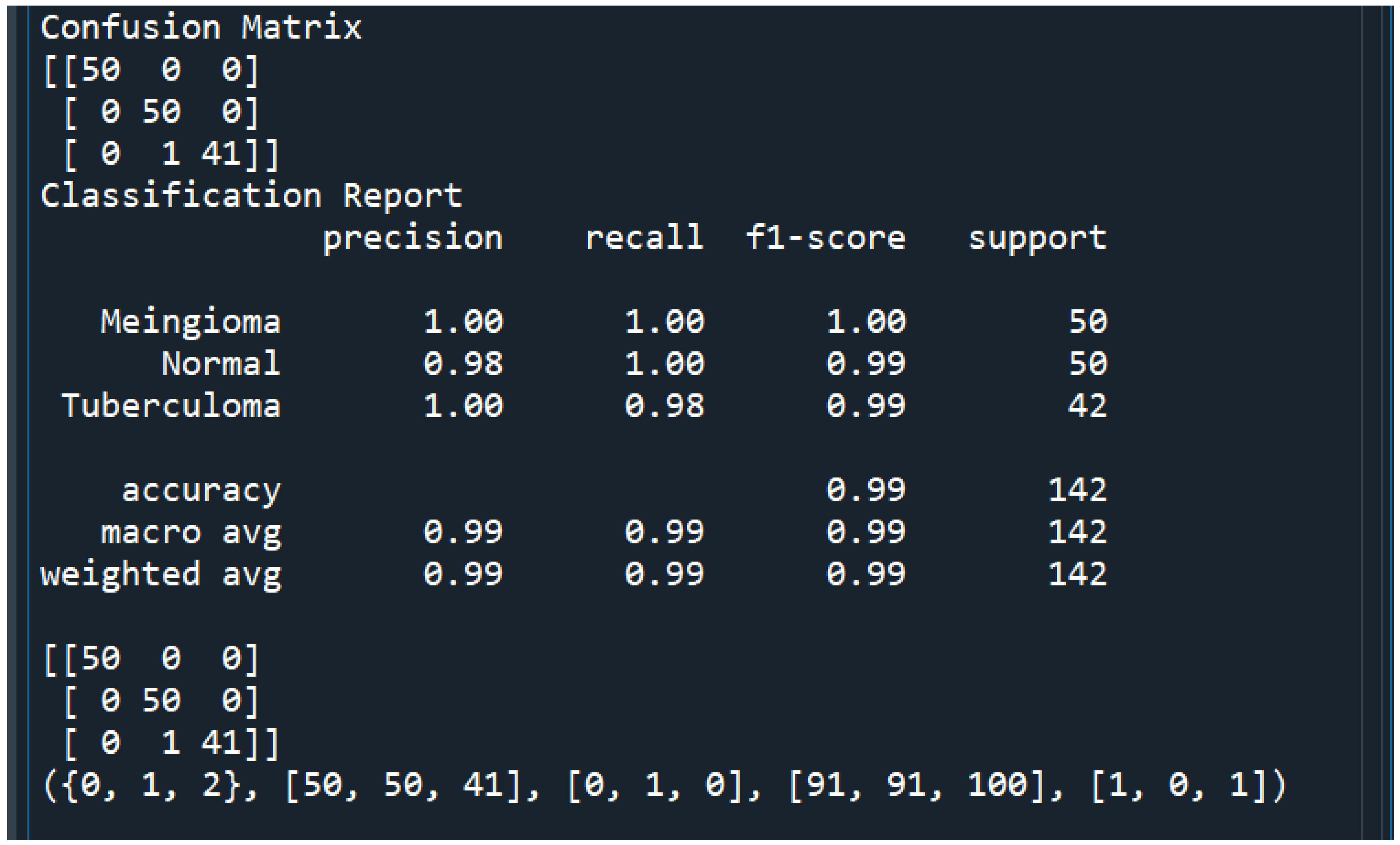

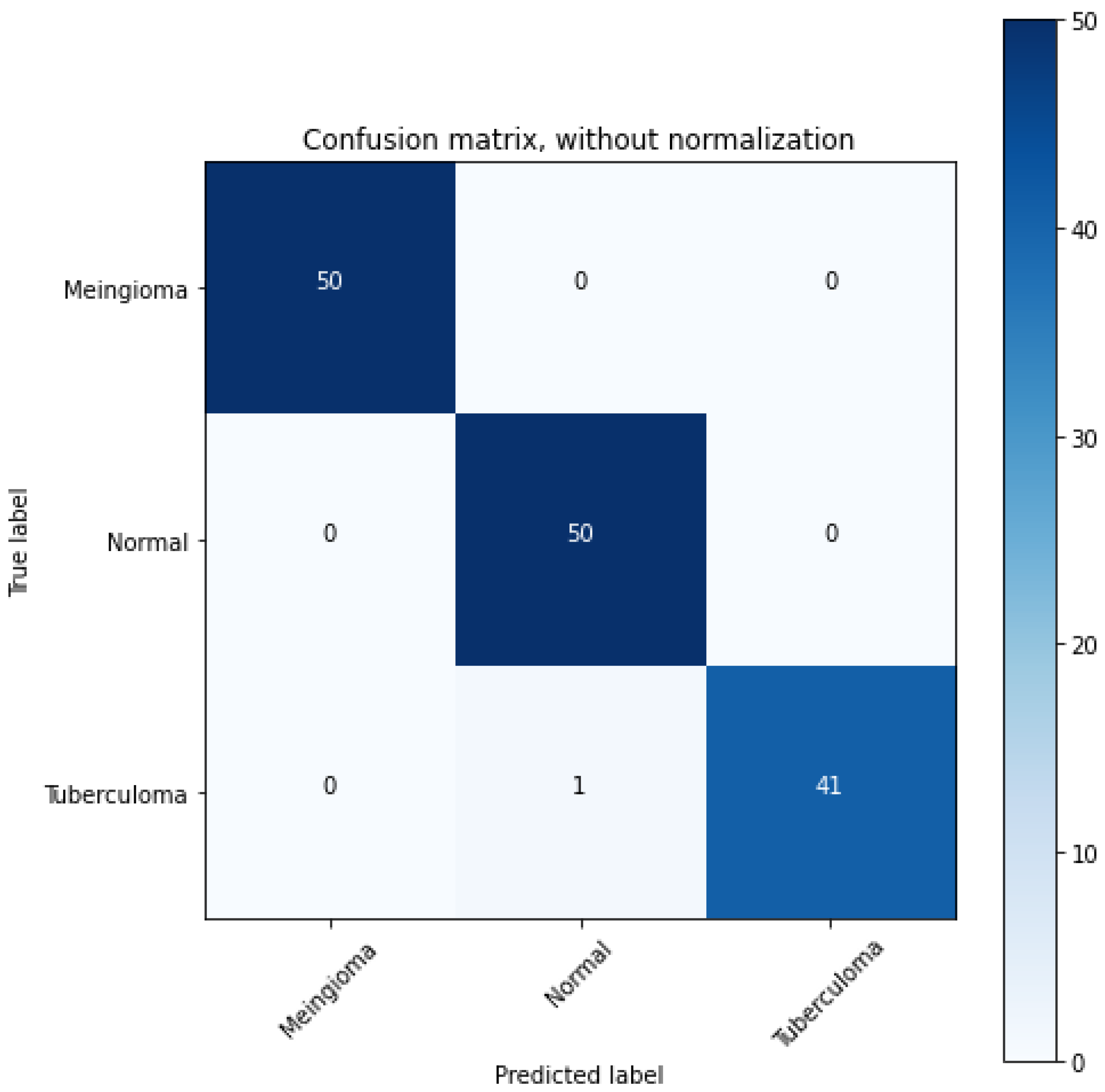

3.3. Dataset

The dataset containing MRI scans that we have obtained from an anonymous hospital in India contains 264 images belonging to 3 classes and we have considered 14 among them for training and the rest for testing. We have used segments of 264 3D FLAIR sMRI images belonging to 3 classes(meningioma, tuberculoma, normal). The reason for using limited number of images is because VGGNet is extremely computationally expensive and takes several days to train on NVIDIA GPU. We have considered implementing the model for larger than 5000 images in the future for effective generalization of the problem. First patient is a young, normal healthy patient with no observable pathology. The second patient has meningioma with a lot of metastases and the third patient has tuberculoma. The total number of parameters is 20,148,803 with 124,419 trainable parameters and 20,024,384 non-trainable parameters(

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Loading Multi Layered VGG-16 DNN Sequential Model.

Figure 2.

Loading Multi Layered VGG-16 DNN Sequential Model.

Figure 3.

10 Epochs That We Have Considered for Training Our DNN.

Figure 3.

10 Epochs That We Have Considered for Training Our DNN.

3.4. Activation Functions

The functions that we have used are :

SoftMax - SoftMax is utilised in Convolutional Neural Networks(CNNs) to convert the network’s final layer logits into probability distributions, ensuring that the output values represent normalized class probabilities, making it suitable for multi-class classification tasks.

Considering this function, the function values of both classes are determined and manipulated to add up to unity. It is represented by the undermentioned equation :

Cross Entropy/Loss Function - SoftMax is usually paired with the cross-entropy loss function in the training phase of CNNs. Cross-entropy measures the dissimilarity between the predicted probabilities and the true distribution of the classes. SoftMax, by producing a probability distribution, aligns well with the requirements of the cross-entropy loss. We have exploited this function after utilising SoftMax function whereby our goal is to foresee our network performance and by functioning to decrease this mean squared error, we would practically be optimizing our network. It is represented as(both are different forms of the same loss function equation):

3.5. Optimization Algorithm

In this work, we have also compiled the model using the cost optimization technique called ADAM(Adaptive Moment Estimation) Optimizer. ADAM, is an adaptive learning rate algorithm designed to improve training speeds in deep neural networks and reach convergence quickly. It customizes each parameter’s learning rate based on its gradient history, and this adjustment helps the neural network learn efficiently as a whole. It uses ⊙ which denotes the Hadamard product(element-wise multiplication) and ⊘ which denotes Hadamard division(element-wise division) and ϵ is the smoothing term used to make sure that division by zero does not take place.

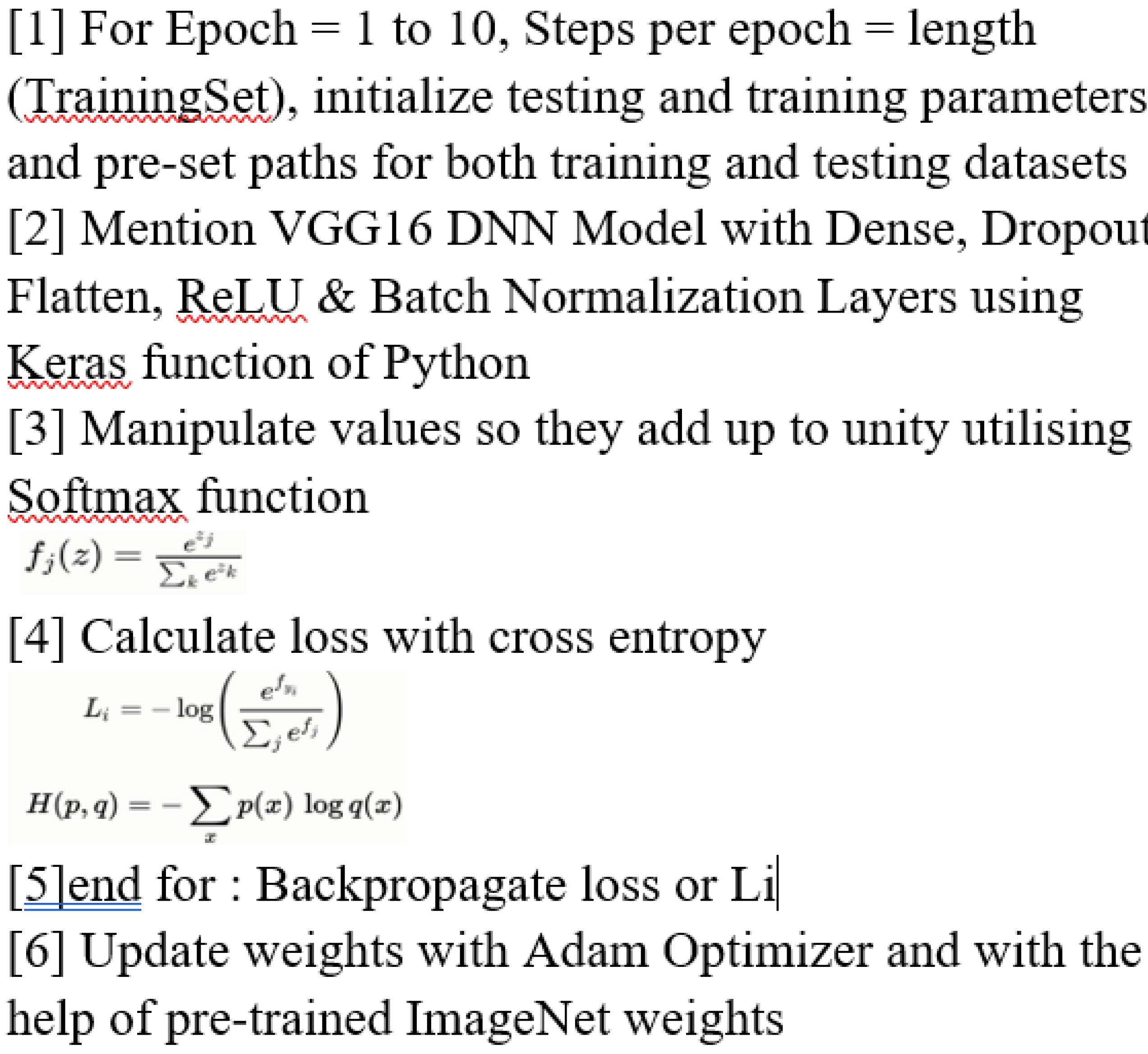

3.6. DNN Implementation Algorithm

We have used DNN or Deep Neural Network Algorithm for this research which is outlined as under(

Figure 4):

5. Conclusion and Future Work

This research proposes a novel approach that significantly advances the application of deep learning for medical diagnostics by employing a very deep transfer learning CNN model(VGG-16) enhanced by CUDA optimisation for the accurate and timely real-time identification of meningiomas.

The different test cases that we have observed are summarized in

Table 1.

Thus, we were successfully able to test 10 random images and classify them as 4 “Normal” images and 6 “Meningioma” images.

4.1. Integration of Output of This Very Deep Transfer CNN Based Real-Time Meningioma Detection Methodology Within the Clinico-Radiomics Workflow

The majority of research utilising radiomic analysis to investigate meningiomas relied on magnetic resonance imaging(MRI), utilising one or more imaging sequences. Because different MRI imaging sequences have varying tumour physiology sensitivity, magnetic resonance imaging(MRI) can, in fact, give a superior anatomical delineation(e.g., spatial position) of the cerebral structures and characterise the prevalence of different physiopathological processes[

63]. Grade prediction and additional uses are the two main categories into which radiomics applications in meningioma can be broadly classified. For this reason, deep learning-based AI technology such as our implemented model offers previously unheard-of improvements in several medical domains when it comes to automated image analysis. The diagnosis and staging of cancer(preoperative grading), treatment selection and individual treatment optimisation, including prognosis modelling, and follow-up imaging are typical areas of use for oncological studies. Numerous imaging modalities can help cancer patients along their path of care[

64]. These radiomic results have begun to change the conventional meningioma treatment workflow.

Figure 9.

Workflows for various meningioma treatment approaches, both with and without radiomic analysis[

64].

Figure 9.

Workflows for various meningioma treatment approaches, both with and without radiomic analysis[

64].

Although there are four basic processes in the radiomics workflow(image acquisition, segmentation, feature extraction, and statistical analysis/model)[

65,

66,

67], each step varies slightly depending on the study and its goals[

68].

The process of radiomics workflow commences with image acquisition, which involves obtaining and reconstructing the image data[

68]. The region of interest(ROI) is identified and segmented in the second stage, which can be done manually, automatically, or semiautomatically. Meningiomas are typically manually defined by skilled radiologists in clinical situations. Because many other tumour types lack well-defined borders and internal heterogeneity, the resulting inter-user variability is unavoidable. While there are other approaches to reduce variability, segmentation techniques are a common one[

67].

Choosing segmentation software wisely and manually verifying results with vision can improve the outcome and increase workflow efficiency, particularly when a radiologist is managing hundreds of cases concurrently. Generally speaking, the human brain is not as efficient as a computer when it is tired, anxious, or has limited expertise. This might lead to misdiagnosis or missing a lesion during an MRI. In contrast, artificial intelligence(AI) may deliver dependable results in a short amount of time, making up for human limitations and avoiding mistakes in clinical settings. Therefore, in this radiomic workflow stage our AI-enabled system can be helpful for novices learning MRI as well as for professionals who are tired or for negligence brought on by people who have had a lot of screenings. In some circumstances, alternative strategies like segmenting a fixed-size ROI[70] or applying an algorithm[

69] might also be effective.

Decoding and quantitatively outputting the high-dimension image data is the next stage of feature extraction[

69]. Currently, feature extraction patterns may be easily categorised as either having human commands or not[

66]. The traditional method requires specialised algorithms that are run by humans. However, the more recent mode, which is based on deep learning radiomics (DLR) and uses CNNs as an example like our model in this workflow stage, can almost entirely do the remaining tasks automatically and without the assistance of humans. Furthermore, compared to conventional approaches, the number of recovered features from CNNs is many orders of magnitude higher[

66]. However, in order to prevent overfitting, feature dimensions must be reduced[

69]. Additionally, several layers inside a single CNN can be used for feature extraction, selection, and classification[

66]. Semantic and agnostic features make up the two categories of radiomics features. The radiology lexicons that are frequently employed to intuitively define the lesion, such as size, location, and shape, are indicated by semantic characteristics. In contrast, agnostic features are quantitative descriptors that are derived theoretically with the intention of emphasising lesion heterogeneity[

69]. There are three types of agnostic features: first-, second-, and higher-order. First-order statistics, which are usually based on the histogram and show skewness and kurtosis, show the distribution of values of individual voxels without taking into account spatial correlations. Second-order statistics characterise statistical correlations, or “texture” features, between voxels that have comparable(or dissimilar) contrast values. Higher-order statistical features, such as Laplacian transforms, Minkowski functionals, etc., are repeating or nonrepetitive patterns filtered through particular grids on the picture[

69].

The chosen features can be utilised for a variety of analyses in the last stage of statistical analysis and modelling, and they are typically included into predictive models to offer better risk stratification[

68]. The process of creating a model involves integrating a number of analysis techniques, grouping features, and allocating distinct values to each feature based on the information content that has been predetermined. These analytical techniques will make use of statistical techniques, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. A perfect model will be able to handle sparse data, such as genetic profiles, in addition to handling the extracted features well[

69]. The model’s versatility increases with the number of covariates it can manage.

In order to accurately classify meningiomas from MR image slices, a deep learning architecture utilising CNNs was discussed and put into practice in this study. In the end, better patient outcomes may result from this research’s ability to provide more accurate and customised treatment strategies for patients with correctly diagnosed brain tumours.

4.2. Limitations of Our Study

Still, there’s always space for improvement, and further research is needed in a number of areas. One of the study’s methodological flaws is data bias, which is the predominant representation of data from a single age group(those > 50) and may result in a lack of diversity in the dataset and restricted generalizability to other datasets and imaging modalities. The whole population should have been included in a dataset that was well-balanced. Its incapacity to differentiate between various brain tumour subtypes is another drawback. Meningiomas are smaller than gliomas, and the former are frequently more noticeable than the latter. Gliomas, however, can readily pass for menigiomas on MRI because to characteristics including the broad dural contact, CFS cleft sign, and dural tail sign, which could lead to confusion in the diagnosis. Correct brain tumour grading classification has important therapeutic ramifications since it can guide therapy choices and enhance patient outcomes. The ultimate goal of this project is to accurately detect brain tumours at the medical picture analysis stage and throughout the planning and execution of robotic surgery by using deep learning techniques in computer vision.

4.3. Computational Complexity of the Model; Trade-Offs Between Accuracy and Computational

4.3.1. Demands

The CNNs’ deep architectures are typically arranged in a pipeline of descriptors that progresses in representational granularity from edges and corners to motifs, sections, and, at the end, objects. In order to accomplish this, CNNs rely on fully connected and softmax classification modules to deliver the final classification of the input image, as well as many convolutional and sub-sampling layers that acquire the features and reduce their dimensionality, respectively. For these reasons, a high computational burden and memory occupation are common characteristics of CNNs. With over 138 million parameters that demand over 527 MB of storage and over 13 billion operations for processing the input image, VGG-16 is computationally and memory intensive[71].

Hence, the computational cost of the VGGNet model is very high. On an NVIDIA GPU, training takes many days. Therefore, we are excited to add more input photographs to the model after implementing it for 264 images in the beginning. We have a total of 20,148,803 parameters, of which 124,419 are trainable and 20,024,384 are not, in order to balance the trade-offs between accuracy and computing needs. Increasing the Imagenet accuracy for a range of parameter values is something we are excited about.

4.3.2. Potential Future Research Directions

We intend to continue developing the Inception-V3 model in the future. Moreover, additional research could be conducted to categorise these images as normal, gliomas, pituitary tumours, tuberculomas, meningiomas, and also be able to determine the extent of metastasis rather than relying solely on a basic prediction system that distinguishes between normal and meningiomas. The grade of the tumour can also be used to classify. Current developments in this field of study include the application of more effective methods that need less time complexity and have higher accuracy. Several layers of CNN are altered to improve performance. Future research should focus on exact tumour delineation and characterization, generative AI, massive medical language models, multimodal data integration, and racial and gender inequities[72,73]. Clinical results will be optimised by personalised treatment techniques that are adaptive. Like RNNs (Recurrent Neural Networks), integrated techniques can be used in conjunction with SVM (Support Vector Machine) to improve detection. Subsequent research endeavours ought to concentrate on integrating the auspicious outcomes of machine learning (ML) algorithms into clinical settings, encompassing the creation of software solutions that are easy to employ for medical practitioners. In the future, robotic neurosurgery could greatly benefit from the integration of AI with cutting-edge technologies like neuronavigation and augmented reality, ushering in a new era of surgical procedures that are safer and more precise.

Terminologies: meningioma, glioma, pituitary, metastasis, cross entropy; radiomics

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D., and B.D.; methodology, D.D.; software, D.D.; validation, D.D., C.S. and B.D.; formal analysis, D.D.; investigation, D.D.; resources, D.D.; data curation, D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D.; writing—review and editing, D.D., C.S. and B.D.; visualization, D.D.; supervision, B.D.; project administration, C.S. and B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.