1. Introduction

Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is a rare inborn error of metabolism that affects the development of bones and teeth and is caused by pathogenic variants in

ALPL gene, coding for the alkaline phosphatase, tissue-nonspecific isozyme (TNSALP, EC:3.1.3.1). Since the first description by Rathbun [

1], more than 400 variants in

ALPL, predominantly missense, have been identified [

2], explaining highly variable clinical phenotype of HPP. Both autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been reported, with the former often, but not always, corresponding to a more severe clinical phenotype [

3]. TNSALP is expressed in liver, bone (synthesized by the osteoblasts), kidney, as well as brain [

4] and it functions as a homodimeric ectoenzyme with a broad phospho-substrate specificity [

5]. Natural substrates of TNSALP include, but likely are not limited to [

5], inorganic pyrophosphate (PP

i) [

6,

7], pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP, the active form of vitamin B

6) [

8,

9,

10] and phosphoethanolamine [

8,

11,

12]. The severity of clinical phenotype strongly correlates with the residual TNSALP enzyme activity [

3,

5,

13]. Increased levels of plasma PLP and urinary and plasma PEA along with reduced serum unfractionated alkaline phosphatase activity serve as diagnostic markers of HPP [

5,

14].

Accumulation of TNSALP substrates in HPP patients reflects the physiological role of the enzyme and clarifies metabolic basis of HPP. Based on the age of diagnosis/onset of symptoms and severity of clinical phenotype HPP is classified in: perinatal (benign), perinatal (severe), infantile, childhood (mild), childhood (severe), adult and odontohypophosphatasia, with perinatal (severe) and infantile forms being most severe [

14]. The main clinical feature of HPP is abnormal bone mineralization causing premature loss of deciduous teeth, rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults. The bone phenotype of HPP is explained by accumulation of PP

i, a potent inhibitor of bone mineralization [

15]. Paradoxically, in some cases, premature closure of cranial sutures (craniosynostosis) occurs in infantile and childhood HPP causing intracranial hypertension [

5,

16]. In addition, blocked entry of minerals into the skeleton may lead to hypercalcemia/hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, and renal impairment [

5,

17]. In the most severe forms of perinatal and infantile HPP vitamin B

6-dependent seizures may occur, indicating a lethal prognosis [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The seizures begin in the first hours after birth, are refractory to standard anticonvulsant drugs, but are responsive to pyridoxine (unphosphorylated form of vitamin B

6) [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. B

6-dependent seizures are explained by the role of TNSALP in the cellular uptake of PLP (phosphorylated form of vitamin B

6) [

23], with the decreased TNSALP activity presumably leading to vitamin B

6 deficiency in the central nervous system (CNS) (

Figure 1a). The correlation between the response to pyridoxine and the severity of pediatric HPP reinforces TNSALP’s role in vitamin B

6 metabolism [

24]. Other, less well understood neurological symptoms of HPP may include depression, memory loss, ADHD, anxiety, headache and sleep disturbance [

25].

HPP is an incurable disease. In addition to symptomatic treatment, enzyme replacement therapy with asfotase alfa, a mineral-targeted human recombinant TNSALP, is available for treatment of the bone phenotype of HPP [

5,

26]. Therefore, understanding TNSALP function in the kidney, liver, brain and other soft tissues as well as the mechanistic basis of milder neurological symptoms of HPP is becoming more relevant to improve quality of life of HPP patients.

Zebrafish (

Danio rerio) is a promising model organism to study human disease [

27], including HPP [

28,

29]. Zebrafish have 4 genes coding for alkaline phosphatases: two for intestinal alkaline phosphatases

alpi.1 and

alpi.2 (gene duplication), one for alkaline phosphatase 3

alp3 (also expressed in intestine)

, and one for tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase

alpl, which also shows high degree of genetic conservation with human

ALPL [

28,

29]. In the present study we generated the first

alpl-/- zebrafish line using CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology. Biochemical and behavioral characterization of

alpl-/- zebrafish showed that they display multiple features of infantile HPP, including decreased bone mineralization, abnormal vitamin B

6 metabolism, abnormalities in neurotransmitter levels and pyridoxine-responsive seizures, as well as N-methylethanolaminium phosphate accumulation. Therefore, this new animal model could be used to gain insight in less understood aspects of HPP pathophysiology as well as for rapid screening of novel treatments.

3. Discussion

While the mechanistic basis of the bone phenotype of HPP is well understood, several unexplained clinical features remain, including craniosynostosis and neurological manifestations [

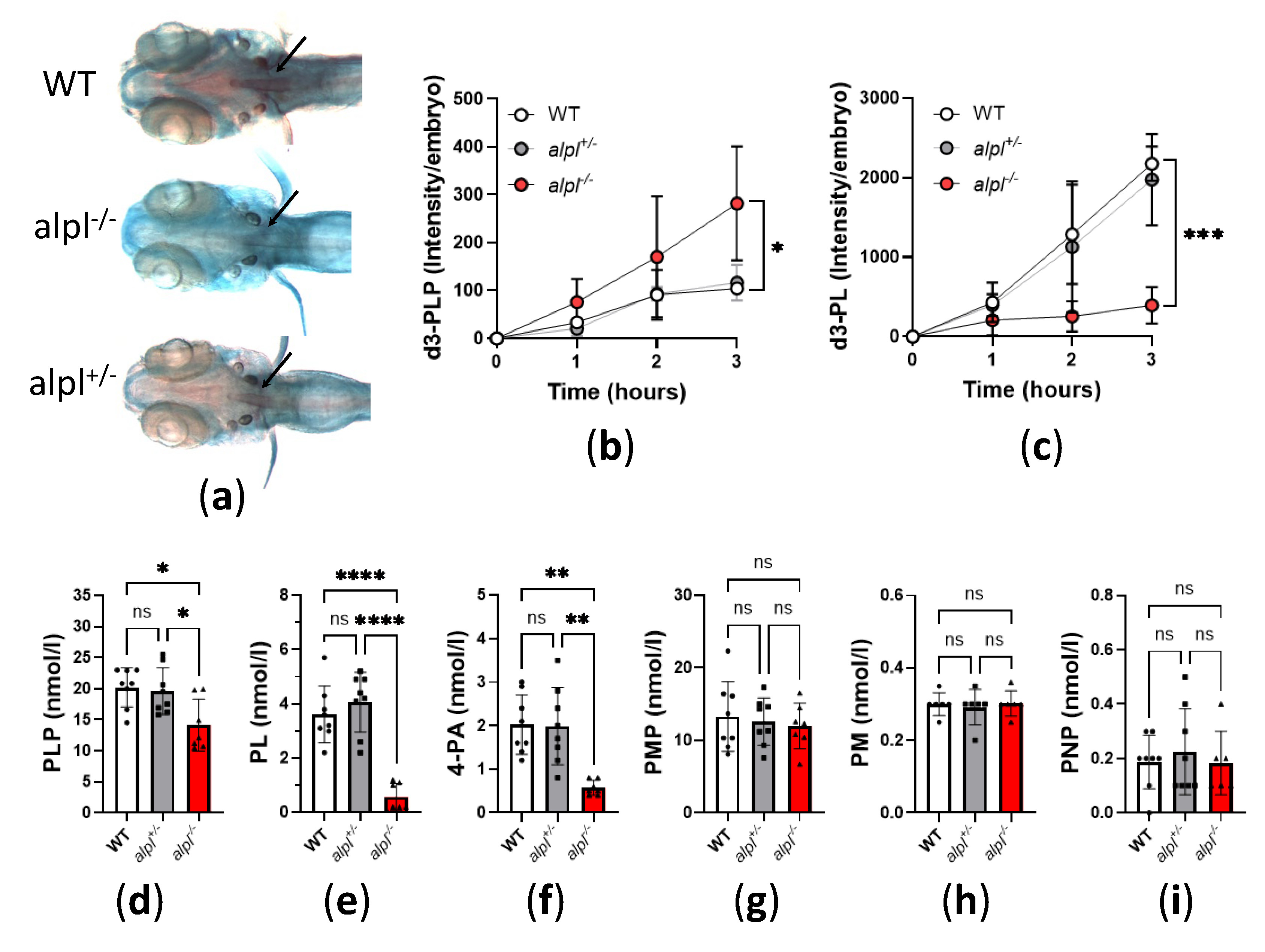

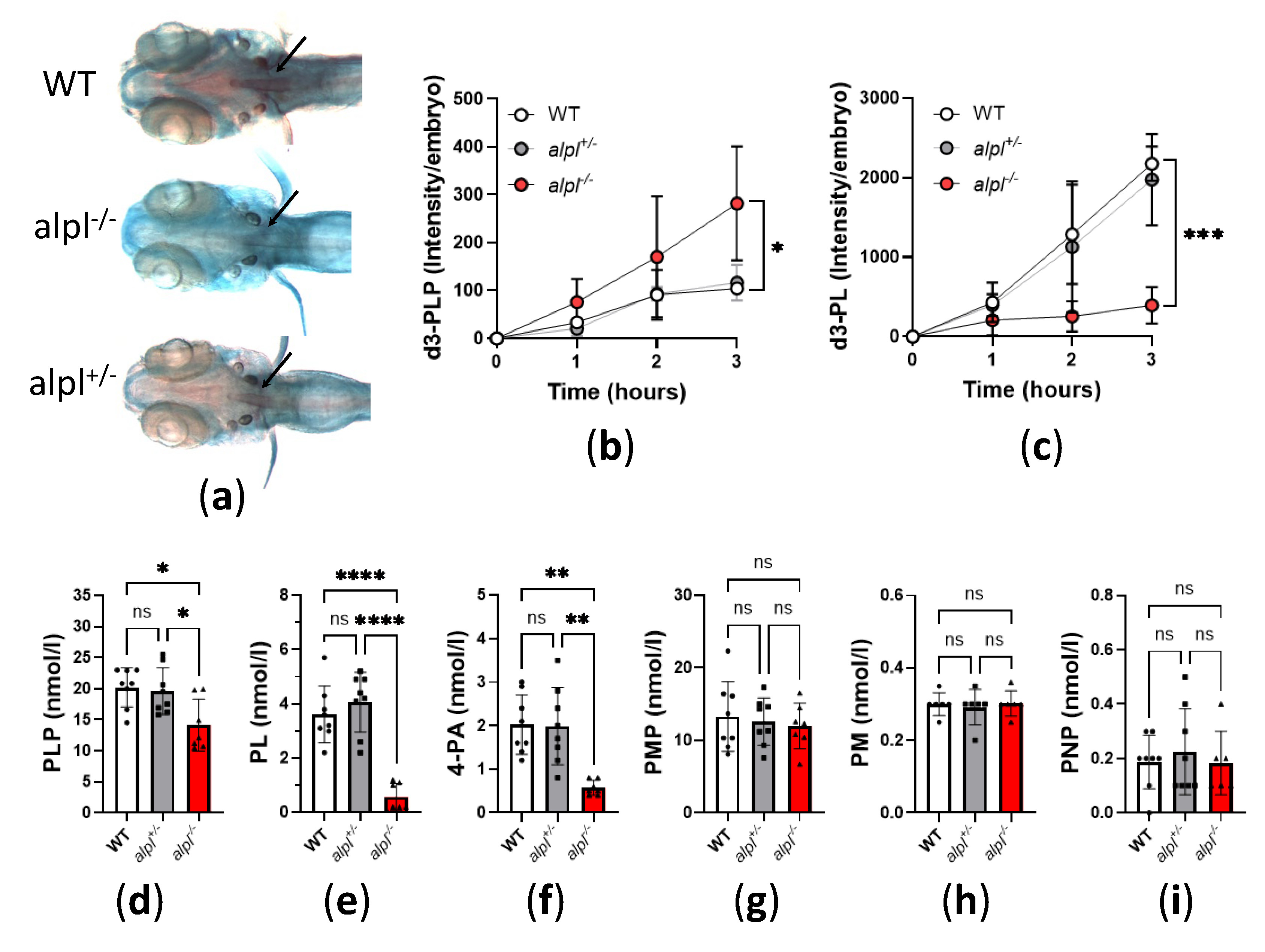

22,

25]. Moreover, the understanding of TNSALP function in the soft tissues like kidney, liver and brain is very limited, underscoring the need for further fundamental research. In the present study we described the first genetic model of tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase deficiency in zebrafish that displayed many key features of human HPP. Our data showed that like TNSALP in humans, Alpl in zebrafish has a function in vitamin B

6 metabolism, as illustrated by strongly impaired ability of

alpl-/- embryos to hydrolyze d3-PLP to d3-PL. The deficiency in Alpl activity led to lower total PLP, PL and 4-PA levels, and to vitamin B

6 (pyridoxine)-responsive seizures. Moreover, multiple metabolic abnormalities were identified through untargeted metabolomics that were linked to decreased cellular/tissue PLP levels and impaired activity of PLP-dependent enzymes. However, pyridoxine treatment improved, but not fully restored to WT level the survival of

alpl-/- zebrafish. This suggests that deficiency of functions other than in vitamin B

6 metabolism (e.g., bone mineralization) played essential role in the lethality of alpl deficiency in zebrafish.

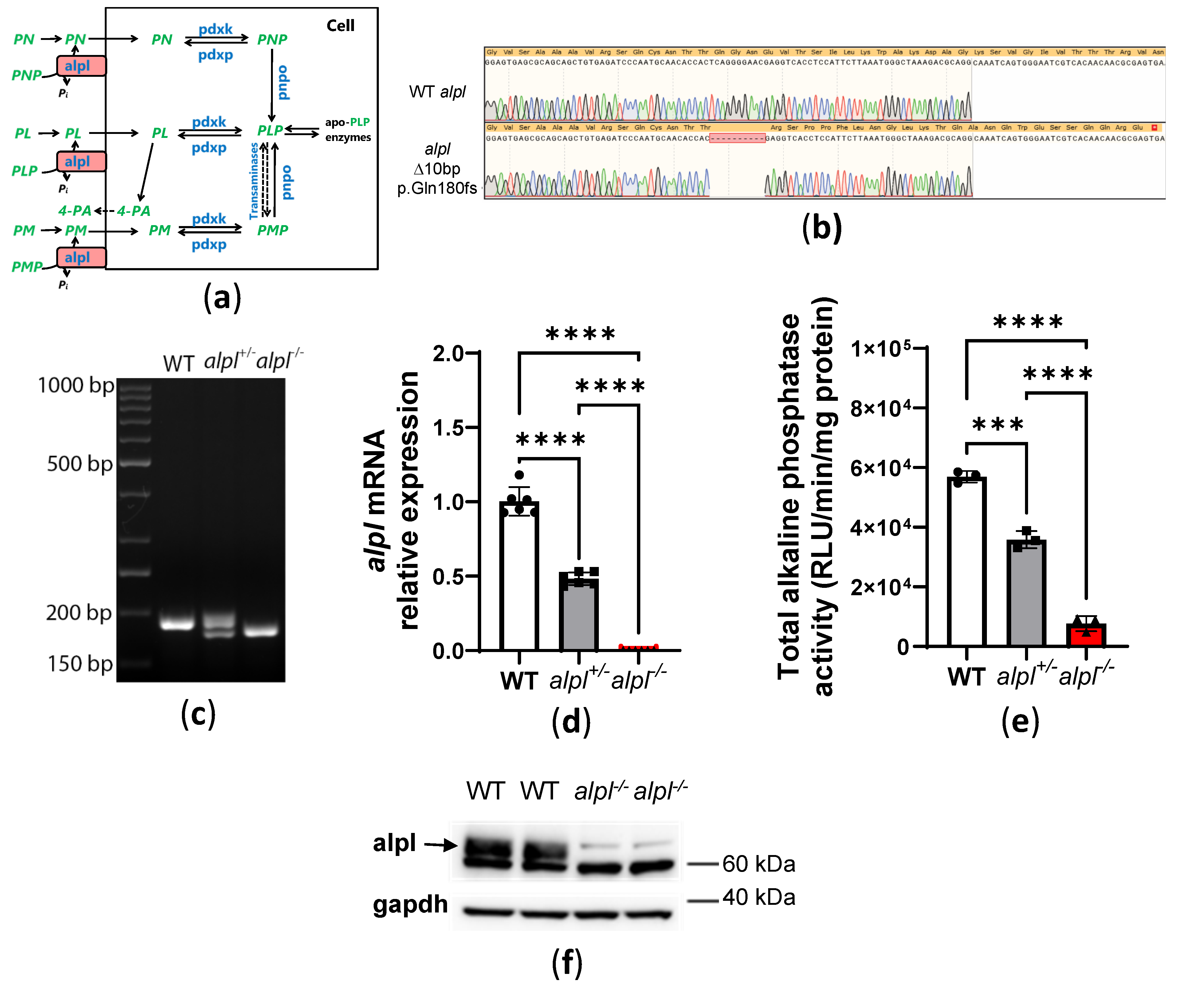

There is a high degree of evolutionary conservation of the gene coding for TNSALP in vertebrates [

40,

41], indicating that animal models of TNSALP deficiency can yield valuable insight in physiological functions of TNSALP and pathophysiology of HPP [

29]. The murine models of TNSALP deficiency have already proven essential for the development of enzyme replacement therapy [

42], which is currently the only available treatment option effective for bone phenotype of human HPP [

26]. Zebrafish is increasingly used as an alternative model organism to study human diseases due to its ease of breeding, large number of offspring, and short generation time. The conservation of zebrafish Alpl function in skeleton and nervous system was previously postulated based on the comparison of tissue-specific gene expression patterns in zebrafish, mouse and human [

41]. In the present study we describe the first genetic model of TNSALP deficiency in zebrafish generated using CRISPR/Cas gene editing. Although there was virtually no mRNA and protein detectable, there was residual alkaline phosphatase activity in 5dpf

alpl-/- embryos. Since enzyme activity measurements were done in the total embryo extracts, the most plausible explanation of the residual activity is contribution of intestinal alkaline phosphatase (encoded by

alpi.1 and

alpi.2) and alkaline phosphatase 3, also expressed in intestine, to the total measured enzyme activity. Residual alkaline phosphatase activity was also measured in serum of the first genetic murine model of TNSALP deficiency (

Akp2-/-), which was explained by the contribution of genetically distinct intestinal alkaline phosphatase activity [

43]. Furthermore, the biochemical and behavioral characteristics of

alpl-/- zebrafish described in the present study were comparable to the phenotypic features of

Akp2-/- mice, which recapitulate lethal infantile HPP extremely well, including bone abnormalities and vitamin B

6-responsive seizures with untreated seizing animals dying before weening [

43,

44,

45]. Data from available murine models of TNSALP deficiency show that in contrast to human TNSALP, murine TNSALP appears to be not essential for the initial events of bone mineralization during the intrauterine development (i.e., no severe skeletal abnormalities typical to perinatal HPP), but it becomes important for this process after birth [

43,

44,

45]. In the present study we showed that zebrafish Alpl functions in bone mineralization, as indicated by decreased alizarin staining of notochord, one of the earliest mineralizing structures in zebrafish embryo [

31]. This effect was comparable to the effect of chemical Alpl inhibition on bone mineralization in wild-type zebrafish embryos [

41].

Vitamin B

6 (pyridoxine)-responsive seizures is a rare clinical feature of HPP, observed only in the most severe forms of perinatal and infantile HPP [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. They are presumably caused by decreased PLP and PL availability in cells of central nervous system due to decreased/absent hydrolysis of extracellular PLP to PL (

Figure 1a). Impaired activity of PLP-dependent enzymes involved in amino acid and neurotransmitter synthesis, e.g., decreased synthesis of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA due to lower activity of PLP-dependent glutamate decarboxylase (EC: 4.1.1.15), and resulting imbalance in the levels of inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters, underlies seizures [

18,

46,

47]. Indeed, by using stably labeled PLP, we could show that the hydrolysis of PLP and production of PL is strongly impaired in

alpl-/- embryos, leading to lower concentrations of PLP and PL, as well as 4-PA (degradation product of PL) in total embryo extracts (dominated by tissue derived PLP and PL). Unfortunately, due to the small size of the embryos we were unable to separately quantify PLP in the circulation and in the individual tissues. However, PLP deficiency in tissues including the brain were suggested by the observation that GABA concentrations in

alpl-/- 5 dpf embryos and 10 dpf larvae were lower than in WT zebrafish, and they were normalized by PN treatment. The abnormalities in B

6 vitamer and GABA concentrations in

alpl-/- zebrafish were in line with the findings in

Akp2-/- mice, which have high serum PLP and low PL concentrations, as well as low PLP and PL concentrations in various tissues including the brain [

43,

44], and low brain GABA concentration [

43]. In HPP patients circulating PLP concentration is elevated [

9], making it a good biomarker of HPP [

14], while PL concentration is less often reported, ranging from normal [

18] to low in severe cases [

10]. A single report in various post-mortem tissues of two patients with perinatal HPP showed no alterations in PLP and PL concentrations [

10]. Lastly, similar to

Akp2-/- mice [

43,

44,

45] and severe forms of perinatal and infantile HPP [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], also

alpl-/- zebrafish embryos developed spontaneous seizures that were responsive to PN treatment. However, we detected no spontaneous seizures in 10 dpf

alpl-/- larvae, possibly which may be attributed to the fact that the measurements in larvae were done in a small number of the surviving larvae. Only subpopulation of

Akp2-/- mice experience seizures [

43]. The underlying cause of phenotypic heterogeneity despite of genetic homogeneity is not clear. We showed that, similarly to

Akp2-/- mice [

43,

44,

45] and HPP patients [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], spontaneous seizures in

alpl-/- zebrafish embryos were responsive to PN treatment leading to improved survival of the mutants. The lack of complete rescue of the survival by PN treatment is in line with the multiple non-overlapping TNSALP functions, as demonstrated in

Akp2-/- mice where PN treatment prevents seizures without beneficial effect on the skeletal phenotype [

48].

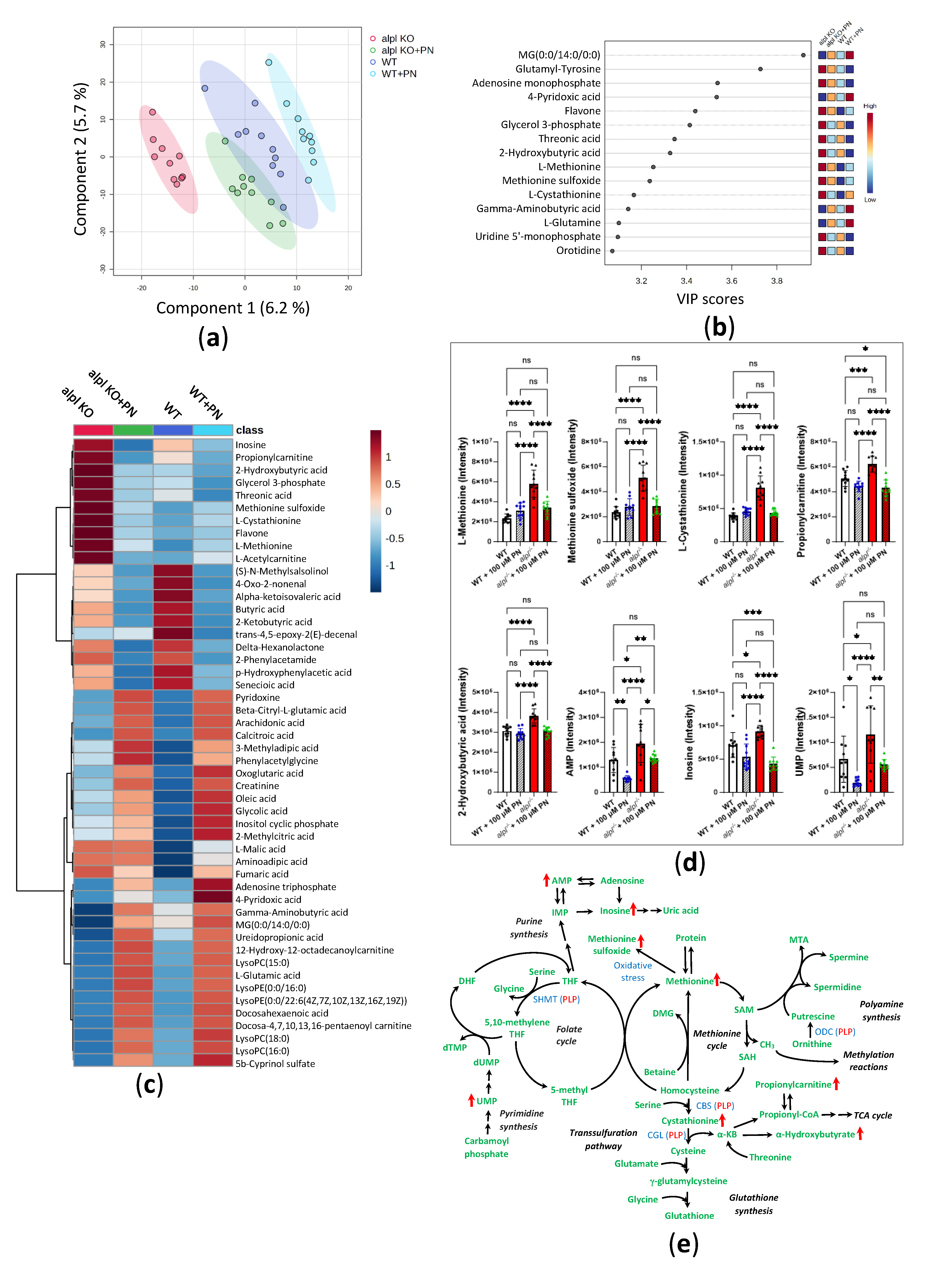

The untargeted metabolomics analysis of broader consequences of Alpl deficiency showed abnormalities in several neurotransmitter levels attributable to decreased cellular PLP availability. Next to lower GABA levels, increased levels of L-DOPA and vanillactic acid along with lower levels of dopamine and epinephrine pointed towards decreased activity of PLP-dependent AADC in

alpl-/- larvae. Impaired AADC activity was also implied in HPP patients based on elevated 3-ortho-methyldopa in CSF [

18,

47] and increased vanillactic acid in urine [

47]. Moreover, we observed that accumulation of N-methylethanolaminium phosphate (PEA) is detectable in

alpl-/- larvae but not yet in 5 dpf embryos, indicating that in zebrafish accumulation of PEA develops gradually.In

Akp2-/- mice elevated serum PEA concentrations were shown in 8-10 day old pups, however, the age-dependence was not investigated [

43]. Furthermore, we found increased methionine and cystathionine levels in

alpl-/- embryos, suggesting altered activity of methionine cycle and transsulfuration pathway, likely caused by the impaired activity of PLP-dependent enzymes, as underscored by the normalization of these metabolites in response to PN-treatment (

Figure 5E). Interestingly, the elevation of methionine and cystathionine levels was also reported in the brains of 1 week old

Akp2-/- mice [

49], suggesting common underlying mechanisms in zebrafish and mouse. Furthermore, elevated AMP and inosine levels in

alpl-/- embryos suggest abnormalities in purine metabolism that could be linked to the deficiency of the Alpl ectophosphatase function and to the mechanisms of chronic pain via an effect on circulating adenosine levels [

50]. Our observation that PN treatment led to normalization of AMP and inosine levels in

alpl-/- embryos suggested that changes in these compounds were caused by reduced vitamin B

6 availability rather than by the ectophosphatase activity of Alpl. However, empirical pyridoxine therapy for chronic fatigue and pain in four adult-onset HPP patients did not provide symptomatic relief (22), suggesting that the underlying mechanisms are vitamin B

6-independent. It must be noted that due to the contribution of isobaric compounds to the levels of AMP, inosine and adenosine (not changed in

alpl-/- embryos, data not shown) determined with DI-HRMS, further analysis using a targeted method is required.

Lastly, we observed accumulation of vitamin A (retinol) and decreased levels of retinal in

alpl-/- larvae. Interestingly, high

alpl expression and alpl enzyme activity were observed in the eyes (especially lens and retina) of zebrafish embryos [

41], as well as retina of other vertebrates [

51], suggesting that TNSALP has a function in vision. However, no eye-specific phenotype was reported in HPP patients or TNSALP deficient mice. Abnormalities in vitamin A metabolism have been implicated in development of craniosynostosis and skeletal abnormalities in humas and zebrafish [

52]. The mechanistic basis of how Alpl deficiency leads to retinol accumulation needs further investigation. Possibly, impaired Ca

2+ homeostasis caused by Alpl deficiency could affect retinol transport into the cell, which is regulated by Ca

2+/calmodulin [

53], leading to accumulation of circulating retinol and decreased intracellular retinal production.

Taken together, we generated first zebrafish model of HPP that shows multiple features of human disease and is suitable to study pathophysiology of HPP and to test novel treatments. We showed that Alpl has a function in vitamin B6 metabolism and bone mineralization in zebrafish. untargeted metabolomics revealed a multitude of metabolic alterations occurring in response to Alpl deficiency, including, but not limited to phosphoetanolamines, neurotransmitters, nucleotides, polyamines and retinoids suggesting potential interesting directions for follow-up research on the mechanisms of HPP in zebrafish. Furthermore, normalization of multiple metabolic abnormalities in response to PN treatment suggests that vitamin B6 supplementation could be beneficial to HPP patients even in the absence of seizures. This study also revealed limitations of doing metabolic research in zebrafish embryos, particularly related to the small embryo size that constrained the ability to analyze individual tissues/organs. Nevertheless, data presented in this study clearly showed that this zebrafish model can serve as a valuable tool for investigating poorly understood aspects of TNSALP function and for developing improved therapies in the future.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Zebrafish Maintenance and Treatment Protocols

Zebrafish (

Danio rerio) were raised and maintained under standard laboratory conditions [

31]. Animal experiments were approved by and performed according to the guidelines of the Animal Welfare Body Utrecht, Utrecht University (protocol code 1444WP2B2).

Pyridoxine-treatment experiments were carried out in either 5dpf embryos and 10 dpf larvae. For embryo treatment, batches of 2 dpf embryos (not genotyped), generated by incrossing

alpl+/- parents, were randomly assigned to untreated or pyridoxine-treated groups. Next, 0 µM (untreated) or 100 µM (treated) pyridoxine (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to E3 medium in a petri dish and embryos were raised to 5 dpf (3 days continuous treatment). Media were refreshed every 24 hours. At 5 dpf, embryos were anesthetized with tricaine, a sample of caudal fin was dissected for DNA isolation and genotyping, and embryos were instantly frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C until analysis. For larvae treatment, zebrafish embryos were genotyped at 3 dpf as described in [

34]. Only

alpl+/+ and

alpl-/- embryos were raised to 5 dpf. Starting from 5 dpf, zebrafish were treated for 5 consecutive days (between 9.00 and 10.30 am) with 0 µM or 100 µM pyridoxine for 30 min. Treatment included placing zebrafish larvae (n=18-22 per tank) in plastic tanks containing 500 ml of system water without pyridoxine (untreated) or 500 ml of system water containing 100 µM pyridoxine (treated). After 30 min zebrafish larvae were rinsed and placed in the home tank. At 10 dpf zebrafish larvae were anesthetized with tricaine, terminated by instant freezing on dry ice (1 larva per Eppendorf cup) and stored at -80°C until analysis.

To assess the utilization of stably labeled pyridoxal 5’-phospate, 5 dpf old embryos (~60 embryos/petri dish) were incubated with 100 µM pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (methyl-D3) (d3-PLP) (Buchem, Minden, The Netherlands) in E3 for 0, 1, 2 and 3 hours. At specified time-points, embryos were washed with E3, anesthetized with tricaine, dissected for genotyping, snap-frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C until analysis.

4.2. sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA Design and Synthesis

CRISPR/Cas9 gene-specific regions for

alpl were designed by the Sanger Institute (Hinxton, Cambridge, United Kingdom) using a modified version of CHOPCHOP (

http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no). Target sites were selected in exon 5 and exon 6 (Supplemental

Table S1) [

54,

55]. The gene-specific oligonucleotides contained the T7 promotor sequence (5’-TAATACGACTCACTATA-3’), the GGN20 target site without the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), and the constant complementary region 5’-GTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAG-3’. Oligonucleotides were ordered at IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa, USA) and the zebrafish specific pCS2-nCas9n plasmid was obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, USA). Cas9 mRNA transcription and sgRNA synthesis were performed as described before [

56].

4.3. Generation of Alpl Knockout Zebrafish

Wild type Tupfel longfin (WT TL) one-cell stage zebrafish embryos were microinjected in the yolk with approximately 1 nl sgRNA mixture (sgRNA targeting exon 5 and 6, each 30 ng/µl) and Cas9 mRNA (250 ng/µl). CRISPR efficiency was determined in subpopulation of healthy microinjected larvae at 4 dpf. The rest of the healthy microinjected larvae were raised till adulthood. Heterozygous variation was assessed in DNA extracted from healthy embryonal offspring (F1) at 24 dpf. Offspring from a mosaic founder that contained an 10 bp out-of-frame deletion was raised till adulthood and was fin-clipped for genotyping at 9 weeks of age. The mutant zebrafish line was maintained in the heterozygous form by crossing alpl+/- zebrafish with WT TL. In this study, F6 zebrafish (alpl+/+, alpl+/- and alpl-/-) were used, obtained from incrossing F5 alpl+/- zebrafish.

4.4. DNA Extraction and Genotyping

Depending on the type of experiment, genotyping was done on the caudal fin dissections at 3 or 5 dpf (overall experiments), whole 5 dpf embryos (Zebrabox and staining experiments), or adult zebrafish caudal fin dissections (line maintenance) as described in detail in [

34]. Briefly, tissue was lysed in single embryo lysis buffer (SEL) containing 10 mM Tris pH 8.2, 10 mM EDTA. 200 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 12 U/ml proteinase K (freshly added, Thermo Scientific, cat. # EO0491). DNA was isolated using the following thermocycler program: 60 min 60 °C, 15 min 95 °C, 15 min 4 °C, ∞ 12 °C. Genomic regions flanking the CRISPR target sites were amplified with CRISPR site-specific PCR primers (

Table S1), using AmpliTaq Gold 360 DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, cat. # 4398823) in combination with a touch down PCR program as previously described [

57]. Amplicons were visualized on a 3% agarose gel and mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

4.5. RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

Zebrafish embryos (5 dpf) were placed in sterile Eppendorf tubes on ice (10 embryos/tube per genotype, 3 tubes/genotype). Sterile, RNAse-free zirconium oxide beads (0.5 mm) and cold 0.5 ml TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # T9424) were added to each tube. Embryos were homogenized using bullet blender tissue homogenizer (Next Advance) for 10 min in stand 8 at 4 °C. Total mRNA was isolated from the embryo homogenates following manufacturers recommendations. Quantity and purity of the total RNA was quantified using NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). 1 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # M1302) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR was done with StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) using SYBR Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, cat. # 4472908) and primers listed in

Table S1. The

alpl (ZDB-GENE-040420-1, RefSeq:NM_201007.2) mRNA levels were normalized to the mRNA level of β-actin (ZDB-GENE-000329-1, RefSeq:NM_131031.2) and expressed relative to the wild type (calculated according to the ΔΔCt method).

4.6. Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue Staining

Mineralized bone and cartilage were stained in whole 5dpf embryos with acid-free alizarin red and alcian blue double stain as described in [

58]. Briefly, 5 dpf embryos were anesthetized with tricaine and up to 20 embryos were collected per 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube. After removing the medium, 1 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline was added per tube and embryos were fixed for 2 h with agitation at 500 rpm in an Eppendorf thermomixer at room temperature (RT), followed by washing and dehydration with 1 ml 50% ethanol for 10 min at RT. Embryos were stained overnight with 0.0005% alizarin red and 0.4% alcian blue working solution with agitation at RT. Stained embryos were washed and bleached with 1.5% H

2O

2 containing 1% KOH for 20 min at RT. After removing the bleach solution, 1 ml 20% glycerol containing 0.25% KOH was added and embryos were incubated for 2 hours, followed by overnight incubation with 1 ml 50 % glycerol containing 0.25% KOH at RT. Next, medium was replaced with 50% glycerol containing 0.1% KOH and embryos were stored at 4 °C. Images were captured with a Leica DFC420C digital microscope camera (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) mounted on a Zeiss Axioplan brightfield microscope (Carl Zeiss AG). After the imaging, DNA was extracted from stained embryos and genotype was determined as described in section 2.4.

4.7. Alkaline Phosphatase Enzyme Activity

Total alkaline phosphatase enzyme activity was determined in the whole embryo homogenates using assay described in [

59]. Briefly, 5 dpf embryos (n=30 per genotype) were homogenized in 200 µl of Dulbecco′s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS, Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # D8537) containing 0.1% Triton X100 using bullet blender tissue homogenizer (Next Advance) for 5 min in stand 8 at 4 °C. Homogenates were centrifuged at 600 g for 5 min at 4 °C and sonicated using ultrasonic disintegrator (Soniprep 150 Plus, MSE) for 30 sec in the pulse mode (1 s on 1s off, amplitude 10 µm) on ice. Assay mix contained 20 μl embryo extract (5× diluted in DPBS, final protein concentration in the assay 0.065 mg/ml), 80 μl DPBS and 100 μl of CSPD ready-to-use reagent (0.25 mM solution; Roche GmbH, Mannheim, Germany, cat. # CSPD-RO) without Alpl inhibitor (-)-tetramisole HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # L9756) or with 20 mM (-)-tetramisole HCl. Alpl activity was measured by following the chemiluminescence for 5 min at 37 °C using Clariostar microplate reader (BMG Labtech). Alpl activity was expressed as RLU/min/mg protein. Protein concentration in the embryo homogenates was determined using Pierce BCA protein assay kit according to the manufacturers protocol (Thermo Scientific, cat. # 23225).

4.8. Western Blotting

Zebrafish embryos (5 dpf, n=32 per genotype) were placed in Eppendorf tubes on ice, 150 µl RIPA lysis and extraction buffer (Thermo Scientific, cat. #89900) containing 2 mM NaF (Sigma-Aldrich) and protease inhibitor cocktail (1:200, Roche) were added, followed by zirconium oxide beads (0.5 mm). Embryos were homogenized using bullet blender tissue homogenizer (Next Advance) for 10 min in stand 8 at 4 °C. Tissue homogenates were solubilized with agitation for 2 hours at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation at 16200 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were mixed with LDS sample buffer (NuPage, Invitrogen, cat. # NP0007) and dithiothreitol (final concentration 50 mM), and denatured at 98 °C for 5 min with agitation. Proteins were resolved on NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P) with semi-dry blotting system (Novex, Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s recommendations. Membranes were blocked with tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) and 50 g/l bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour at RT. Next, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary rabbit polyclonal anti-ALPL antibody (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # HPA008765) or mouse monoclonal anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, 1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat. # sc-365062) in TBS-T containing 10 g/l BSA. After washing 3 × 10 min with TBS-T, membranes were incubated with a corresponding horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody in TBS-T containing 5 g/l BSA for 1 hour at RT. After the final wash of 3 × 10 min with TBS-T, the immunocomplexes were detected using SuperSignal™ West Atto Ultimate Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Scientific, cat. # A38554) and images were captured with the ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

4.9. B6 Vitamer Analysis

Frozen zebrafish 5 dpf embryos (3 embryos/100 µl TCA) or 10 dpf larvae (1 larva/100 µl TCA) were homogenized in ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA; 50 g/l) with zirconium oxide beads (0.5 mm) using a bullet blender tissue homogenizer (Next Advance) at a speed of 8 for 10 min at 4 °C. Homogenates were centrifuged at 16200 g for 5 min at 4 °C. Next, 80 µl of the supernatant was mixed with 80 µl of a solution containing stable isotope-labeled internal standards, vortexed, incubated for 15 min in the dark and centrifuged at 16200 g for 5 min at 4 °C. B

6 vitamers were quantified using ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) as previously described [

60], except for using 10 times lower concentrations of the calibration samples. For the analysis of pyridoxal 5’-phosphate-(methyl-d3) (d3-PLP) utilization and pyridoxal-(methyl-d3) (d3-PL) formation, zebrafish embryos were processed and analyzed using the same protocol, except that no stable isotope-labeled internal standards were added during UPLC-MS/MS measurement. During all steps, samples were protected from light as much as possible.

4.10. Non-Quantitative Direct-Infusion High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (DI-HRMS)

Metabolite profiling was done in 5 dpf embryos and 10 dpf larvae using a non-quantitative DI-HRMS method described in [

36]. For extraction of metabolites, 3 embryos or a single 10 dpf larvae were homogenized in 100 µl of ice-cold 100% methanol with zirconium oxide beads (0.5 mm) using a bullet blender tissue homogenizer (Next Advance Inc., Averill Park, NY, USA) at a speed of 8 for 10 min at 4 °C. Homogenates were centrifuged at 16200 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants (70 µl) were mixed with 60 µL of 0.3% formic acid (Emsure, Darmstadt, Germany) and 70 µL of internal standard working solution described in [

36], and filtered using a methanol-preconditioned 96-well filter plate (Pall Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) loaded onto a vacuum manifold into an Armadillo high-performance 96-well PCR plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were analyzed using a TriVersa NanoMate system (Advion, Ithaca, NY, USA) controlled by Chipsoft software (version 8.3.3, Advion). Data were acquired using Xcalibur software (version 3.0, Thermo Scientific, Waltham,MA, USA). Raw mass spectrometry data were analyzed using an in-house developed peak calling pipeline written in R programming language (source code available at

https://github.com/UMCUGenetics/DIMS) that utilizes Human Metabolome DataBase (HMDB) for peak annotation with the accuracy of 5 ppm with respect to the theoretical m/z value, as described in detail in [

36]. The web-based analysis tool MetaboAnalyst v.6.0 was used for statistical analysis (one factor) [

61]. Metabolites with multiple possible annotations (isobaric compounds) were processed as single metabolite for statistical purposes.

4.11. Amino Acid and γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Analysis

Amino acid analysis was performed in 40 µl of zebrafish embryo (3 embryos/100 μl) extracts in 100% methanol (see section 2.10 for preparation details) using an UPLC-MS/MS method described in [

62]. GABA was quantified in 10 µl of zebrafish embryo (3 embryos/100 μl) or larvae (1 larva/100 μl) extracts in 100% methanol using an UPLC-MS/MS method described in [

34].

4.12. Locomotion Analysis

Zebrabox system (Viewpoint Live Sciences, Lyon, France) was used to track and quantify the locomotion of zebrafish embryos. 5 dpf old embryos or 10 dpf old larvae (1 embryo/well) were transferred to a 48-wells flat-bottom plate (Greiner Bio-one CELLSTAR) containing 0.5 ml embryo medium E3 medium. Zebrafish embryos/larvae were allowed to acclimatize in the measurement chamber in the dark for 15 minutes prior to the measurement. Locomotion was assessed in the tracking mode using the following settings: background 15, inactivity threshold <1mm/s, and burst activity threshold >30 mm/s. Temperature was maintained at 28 ± 1 °C. Locomotion was tracked in the dark without any intervention for 1 hour. Movement trajectories were recorded and locomotion parameters were quantified with Zebralab software (Viewpoint Live Sciences, Lyon, France).

4.13. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. Number of zebrafish used for specific experiment is indicated in the figure legends. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v.10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For comparison of two groups, Student’s t-test was used. For comparison of three or more groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tuckey’s post hoc test was used. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C., J.J.J and N.M.V.; methodology, J.C., S.M.C.S, N.W.F.M and F.T; validation, J.C., S.M.C.S and M.A.; formal analysis, J.C., S.M.C.S, N.W.F.M, and M.B.; investigation J.C., S.M.C.S, N.W.F.M, and M.B.; resources, J.J.J, N.M.V., J.P.W.B. and G.H.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, M.A., S.M.C.S, N.W.F.M, F.T., J.P.W.B., G.H., J.J.J and N.M.V.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, G.H., J.J.J and N.M.V.; project administration, J.C.; funding acquisition, M.A., J.J.J and N.M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

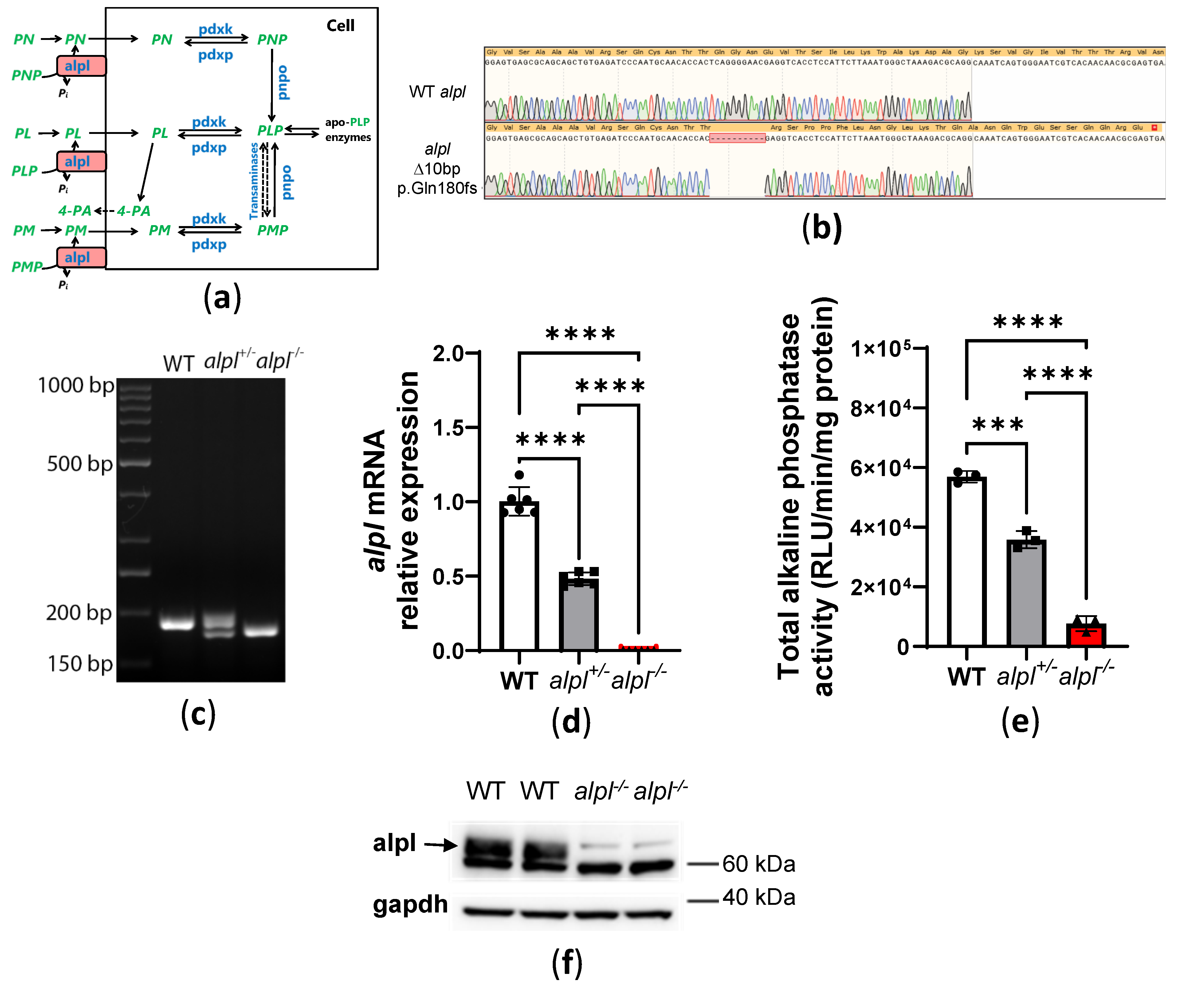

Figure 1.

Generation and basic characterization of alpl-/- zebrafish line. (a) Schematic representation of vitamin B6 metabolism. (b) Sanger sequencing results showing 10 bp deletion at the CRISPR site in exon 5 of alpl gene (c.623_632del, p.Gln180fs), which is predicted to result in a truncated protein. (c) Agarose electrophoresis of genotyping PCR products for the CRISPR site in exon 5 of alpl gene in wild type (WT), alp+/-, alpl-/- 5 dpf old zebrafish embryos. (d) Relative alpl mRNA expression in WT, alpl+/- and alpl-/- 5 dpf old zebrafish embryos. Data are means from n=3 pools (10 embryos per pool) per genotype measured in duplicate ± SD. ****p<0.0001. (e) Total alkaline phosphatase activity in whole-embryo extracts of WT, alpl+/- and alpl-/- 5 dpf old zebrafish. RLU, relative light unit. Data are means from n=3 pools (10 embryos per pool) per genotype ±SD. ****p<0.0001 and ***p<0.001, (f) Alpl protein expression in total WT and alpl-/- 5 dpf zebrafish embryo extracts showing lack of alpl protein in alpl-/- embryos (predicted molecular weight of alpl protein (NP_957301.2) is 62.5 kDa). Data are from pools of n=32 embryos per genotype. Gapdh protein expression was used as the loading control.

Figure 1.

Generation and basic characterization of alpl-/- zebrafish line. (a) Schematic representation of vitamin B6 metabolism. (b) Sanger sequencing results showing 10 bp deletion at the CRISPR site in exon 5 of alpl gene (c.623_632del, p.Gln180fs), which is predicted to result in a truncated protein. (c) Agarose electrophoresis of genotyping PCR products for the CRISPR site in exon 5 of alpl gene in wild type (WT), alp+/-, alpl-/- 5 dpf old zebrafish embryos. (d) Relative alpl mRNA expression in WT, alpl+/- and alpl-/- 5 dpf old zebrafish embryos. Data are means from n=3 pools (10 embryos per pool) per genotype measured in duplicate ± SD. ****p<0.0001. (e) Total alkaline phosphatase activity in whole-embryo extracts of WT, alpl+/- and alpl-/- 5 dpf old zebrafish. RLU, relative light unit. Data are means from n=3 pools (10 embryos per pool) per genotype ±SD. ****p<0.0001 and ***p<0.001, (f) Alpl protein expression in total WT and alpl-/- 5 dpf zebrafish embryo extracts showing lack of alpl protein in alpl-/- embryos (predicted molecular weight of alpl protein (NP_957301.2) is 62.5 kDa). Data are from pools of n=32 embryos per genotype. Gapdh protein expression was used as the loading control.

Figure 2.

Impaired bone mineralization and abnormal vitamin B6 metabolism in alpl knockout zebrafish. (a) Decreased alizarin red staining of mineralized structures (notochord, indicated by arrows) in alpl-/- compared to WT and alpl+/- embryos at 5 dpf suggests a negative effect of alpl deficiency on bone mineralization. (b) Accumulation of d3-PLP and (c) decreased production of d3-pyridoxal (d3-PL) in alpl-/- compared to WT and alpl+/- embryos incubated with 100 µM d3-PLP in embryo water (E3) for 3 hours at 28 °C. Data are means from n=3 pools (3 embryos per pool) per time point and genotype ± SD. (d) Steady-state PLP, (e) pyridoxal (PL), (f) 4-pyridoxic acid (4-PA), (g) pyridoxamine 5’-phospate (PMP), (h) pyridoxamine (PM) and (i) pyridoxine 5’-phosphate (PNP) concentrations in whole embryo extracts. Data are means from n=8 pools (3 embryos per pool) per genotype ± SD. ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001 **p<0.01, *p<0.05 and ns—not significant (p>0.05).

Figure 2.

Impaired bone mineralization and abnormal vitamin B6 metabolism in alpl knockout zebrafish. (a) Decreased alizarin red staining of mineralized structures (notochord, indicated by arrows) in alpl-/- compared to WT and alpl+/- embryos at 5 dpf suggests a negative effect of alpl deficiency on bone mineralization. (b) Accumulation of d3-PLP and (c) decreased production of d3-pyridoxal (d3-PL) in alpl-/- compared to WT and alpl+/- embryos incubated with 100 µM d3-PLP in embryo water (E3) for 3 hours at 28 °C. Data are means from n=3 pools (3 embryos per pool) per time point and genotype ± SD. (d) Steady-state PLP, (e) pyridoxal (PL), (f) 4-pyridoxic acid (4-PA), (g) pyridoxamine 5’-phospate (PMP), (h) pyridoxamine (PM) and (i) pyridoxine 5’-phosphate (PNP) concentrations in whole embryo extracts. Data are means from n=8 pools (3 embryos per pool) per genotype ± SD. ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001 **p<0.01, *p<0.05 and ns—not significant (p>0.05).

Figure 3.

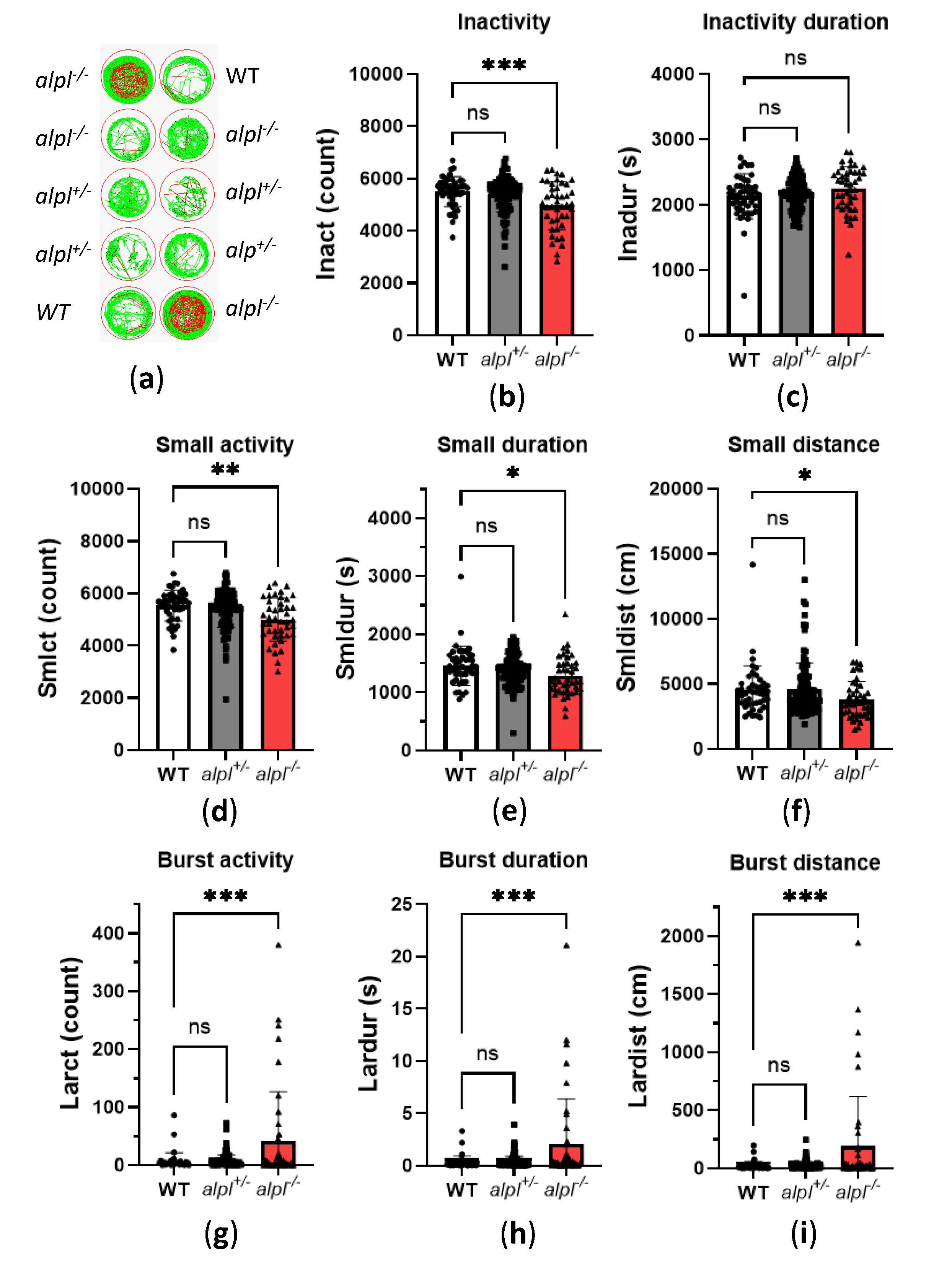

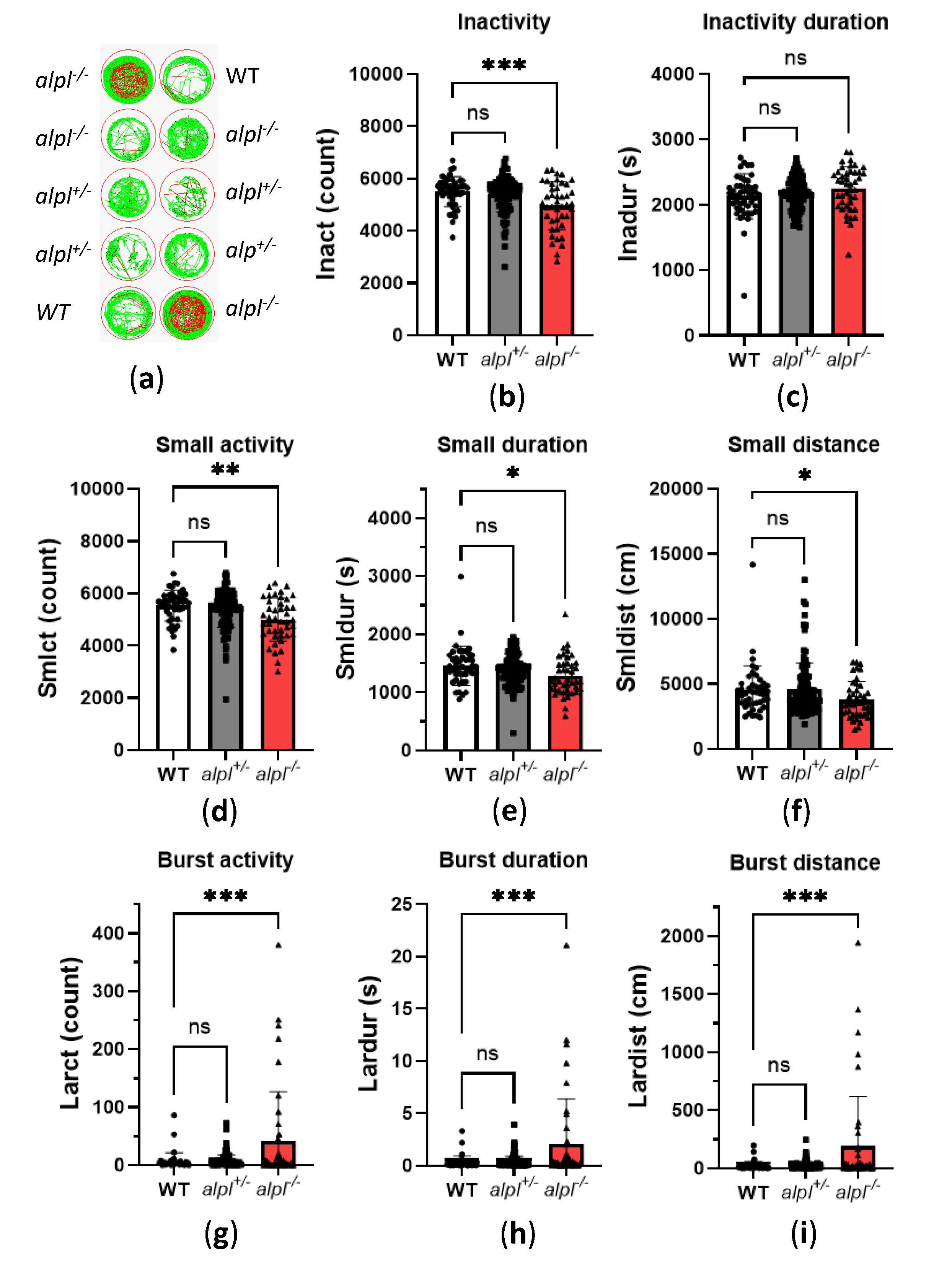

Locomotion analysis of 5 dpf old WT, alpl+/-, alpl-/- zebrafish embryos. (a) Examples of swimming trajectories of 5 dpf old embryos recorded with Zebrabox for 1 hour at 28 °C in the dark. Green—movement speed <30 mm/s (small activity), red—movement speed >30 mm/s (burst activity), black—no movement (inactivity). (b) Inactivity count, (c) Duration of inactivity, (d) Small activity count, (e) Duration of small activity, (f) Distance swum during small activity, (g) Burst activity count, (h) Duration of burst activity, (i) Distance swum during burst activity. Data are means from n=45 (WT), n=105 (alpl+/-) and n=42 (alpl-/-) embryos ±SD. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 and ns—not significant (p>0.05).

Figure 3.

Locomotion analysis of 5 dpf old WT, alpl+/-, alpl-/- zebrafish embryos. (a) Examples of swimming trajectories of 5 dpf old embryos recorded with Zebrabox for 1 hour at 28 °C in the dark. Green—movement speed <30 mm/s (small activity), red—movement speed >30 mm/s (burst activity), black—no movement (inactivity). (b) Inactivity count, (c) Duration of inactivity, (d) Small activity count, (e) Duration of small activity, (f) Distance swum during small activity, (g) Burst activity count, (h) Duration of burst activity, (i) Distance swum during burst activity. Data are means from n=45 (WT), n=105 (alpl+/-) and n=42 (alpl-/-) embryos ±SD. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 and ns—not significant (p>0.05).

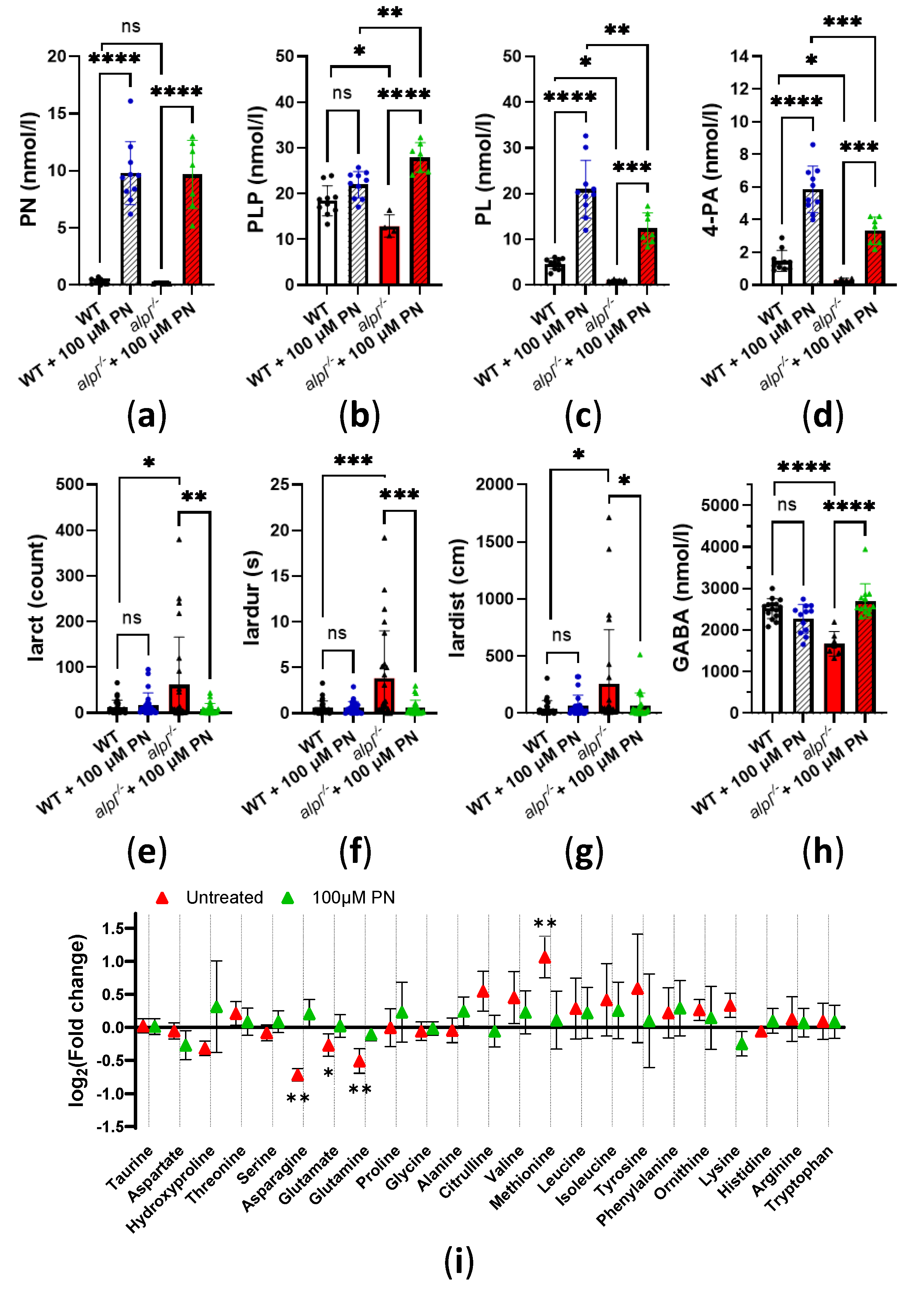

Figure 4.

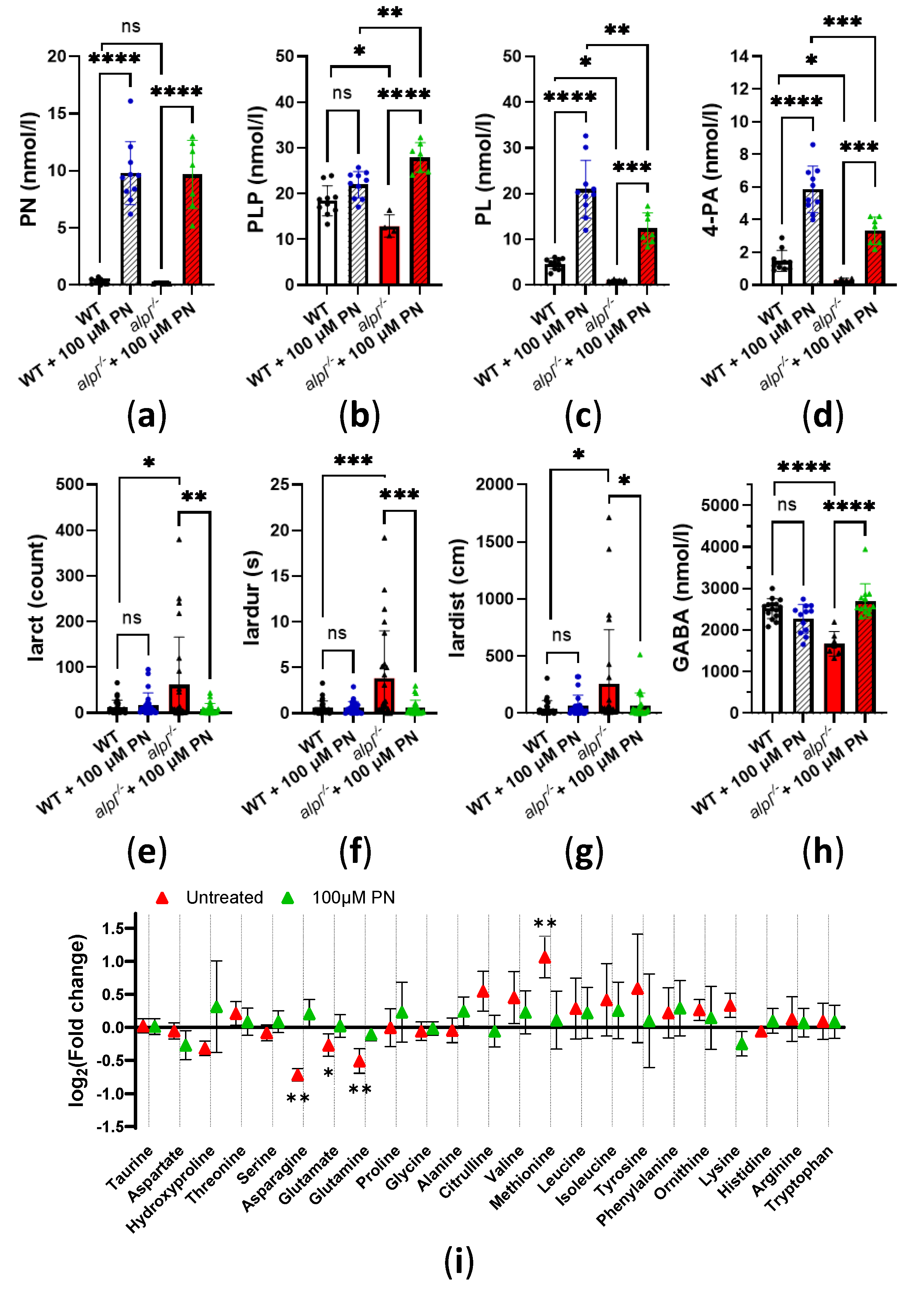

Normalization of biochemical and locomotion abnormalities in 5 dpf old alpl-/- zebrafish embryos after 72 hours continuous treatment with 100 µM pyridoxine (PN). Concentrations of (a) pyridoxine (PN) (b) PLP, (c) pyridoxal (PL) and (d) 4-pyridoxic acid (4-PA) measured in whole 5 dpf old embryo extracts. Data are means from n=4-10 pools (3 embryos per pool) per genotype ± SD. Zebrabox analysis of (e) burst activity count, (f) duration of burst activity, (g) distance swum during burst activity in 5dpf old embryos measured for 1 hour at 28°C in the dark. Data are means from n=23-25 embryos per genotype and treatment ± SD. (h) γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentrations. Data are means from n=7-15 pools (3 embryos per pool) per genotype and treatment ± SD. (i) Fold-change analysis of amino acid concentrations in untreated alpl-/- and 100 µM PN-treated alpl-/- zebrafish embryos compared to the corresponding WT group. Data are from n=4 pools (3 embryos per pool). ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 and ns—not significant (p>0.05).

Figure 4.

Normalization of biochemical and locomotion abnormalities in 5 dpf old alpl-/- zebrafish embryos after 72 hours continuous treatment with 100 µM pyridoxine (PN). Concentrations of (a) pyridoxine (PN) (b) PLP, (c) pyridoxal (PL) and (d) 4-pyridoxic acid (4-PA) measured in whole 5 dpf old embryo extracts. Data are means from n=4-10 pools (3 embryos per pool) per genotype ± SD. Zebrabox analysis of (e) burst activity count, (f) duration of burst activity, (g) distance swum during burst activity in 5dpf old embryos measured for 1 hour at 28°C in the dark. Data are means from n=23-25 embryos per genotype and treatment ± SD. (h) γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentrations. Data are means from n=7-15 pools (3 embryos per pool) per genotype and treatment ± SD. (i) Fold-change analysis of amino acid concentrations in untreated alpl-/- and 100 µM PN-treated alpl-/- zebrafish embryos compared to the corresponding WT group. Data are from n=4 pools (3 embryos per pool). ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 and ns—not significant (p>0.05).

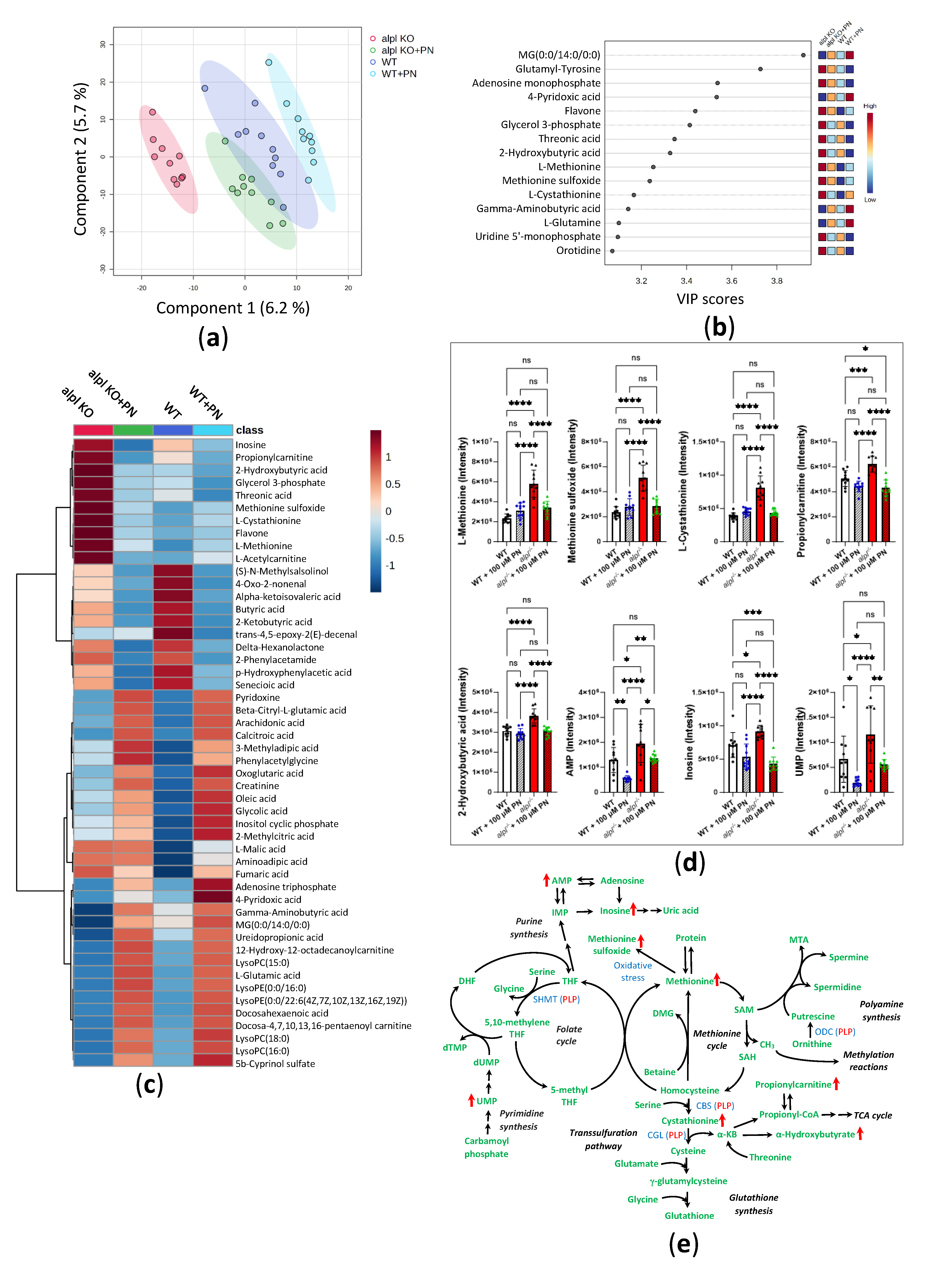

Figure 5.

Global metabolic response to pyridoxine (PN) treatment in 5 dpf old WT and alpl-/- zebrafish embryos. (a) Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) scores plot (principal component 1 (x-axis) and component 2 (Y-axis)). The explained variances are shown in brackets. 95% confidence intervals are shown for each group. (b) Important metabolites identified by PLS-DA for principal component 1. Metabolites with the highest variable importance in projection (VIP) scores are shown. The colored boxes on the right indicate the relative intensity of the corresponding metabolite in each group. (c) Heatmap visualization of group-average intensities of the 50 highest-ranking metabolites based on one-way ANOVA results. Euclidean distance and Ward’s clustering algorithm were used for the hierarchical clustering of metabolites. (d) Intensities of a selection of the highest-ranking metabolites based on one-way ANOVA results. Data are means from n=10 pools (3 embryos per pool) per genotype and treatment group ± SD. ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 and ns—not significant (p>0.05); comparisons as indicated in the graphs. (e) Schematic visualization of metabolic pathways where strongest effects of Alpl deficiency were observed followed by normalization after pyridoxine treatment. Metabolites are shown in green; red arrows indicate the effect of alpl deficiency. Key PLP-dependent enzymes are shown in blue: SHMT, serine hydroxymethyltransferase (EC 2.1.2.1); CBS, cystathionine-β-synthase (EC 4.2.1.22); CGL, cystathionine γ-lyase (EC 4.4.1.1); ODC, ornithine decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.17).

Figure 5.

Global metabolic response to pyridoxine (PN) treatment in 5 dpf old WT and alpl-/- zebrafish embryos. (a) Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) scores plot (principal component 1 (x-axis) and component 2 (Y-axis)). The explained variances are shown in brackets. 95% confidence intervals are shown for each group. (b) Important metabolites identified by PLS-DA for principal component 1. Metabolites with the highest variable importance in projection (VIP) scores are shown. The colored boxes on the right indicate the relative intensity of the corresponding metabolite in each group. (c) Heatmap visualization of group-average intensities of the 50 highest-ranking metabolites based on one-way ANOVA results. Euclidean distance and Ward’s clustering algorithm were used for the hierarchical clustering of metabolites. (d) Intensities of a selection of the highest-ranking metabolites based on one-way ANOVA results. Data are means from n=10 pools (3 embryos per pool) per genotype and treatment group ± SD. ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 and ns—not significant (p>0.05); comparisons as indicated in the graphs. (e) Schematic visualization of metabolic pathways where strongest effects of Alpl deficiency were observed followed by normalization after pyridoxine treatment. Metabolites are shown in green; red arrows indicate the effect of alpl deficiency. Key PLP-dependent enzymes are shown in blue: SHMT, serine hydroxymethyltransferase (EC 2.1.2.1); CBS, cystathionine-β-synthase (EC 4.2.1.22); CGL, cystathionine γ-lyase (EC 4.4.1.1); ODC, ornithine decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.17).

Figure 6.

Progression of metabolic abnormalities in 10 dpf old alpl-/- zebrafish larvae. (a) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of untreated and 100 µM PN-treated WT and alpl-/- zebrafish until 10 dpf. Data are from n=18-42 zebrafish per genotype and treatment condition. (b) Concentrations of pyridoxine (PN), PLP, pyridoxal (PL) and its degradation product 4-pyridoxic acid (4-PA) in untreated and 100 µM PN-treated WT and alpl-/- larvae. Data are means from n=4-10 larvae per genotype and treatment condition ±SD. (c) Distance swum during burst activity (lardist, movement speed >30 mm/s) and during small activity (smldist, movement speed <30 mm/s) during 1 hour measurement using Zebrabox at 28°C in the dark. Data are means from n=9-19 larvae per genotype and treatment condition ±SD. (d) Concentrations of GABA in untreated and 100 µM PN-treated WT and alpl-/- larvae. Data are means from n=5-7 larvae per genotype and treatment condition ±SD. (e) Important features in metabolome of alpl-/- larvae selected by volcano plot with fold change (FC) threshold equal to 2 (x-axis) and t-tests threshold of p<0.05 (y-axis). (f) Accumulation of L-Dopa and vanillactic acid, and decreased level of dopamine, dopamine sulfate (dopamine 4-sulfate and dopamine 3-O-sulfate) and epinephrine in alpl-/- larvae suggest impaired activity of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase. (g) Accumulation of vitamin A (retinol) and decreased level of retinal in alpl-/- larvae. (h) Accumulation of N-methylethanolaminium phosphate in alpl-/- larvae. Data are means from n=5-7 larvae per genotype ±SD (panels E-H). ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01 and *p<0.05.

Figure 6.

Progression of metabolic abnormalities in 10 dpf old alpl-/- zebrafish larvae. (a) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of untreated and 100 µM PN-treated WT and alpl-/- zebrafish until 10 dpf. Data are from n=18-42 zebrafish per genotype and treatment condition. (b) Concentrations of pyridoxine (PN), PLP, pyridoxal (PL) and its degradation product 4-pyridoxic acid (4-PA) in untreated and 100 µM PN-treated WT and alpl-/- larvae. Data are means from n=4-10 larvae per genotype and treatment condition ±SD. (c) Distance swum during burst activity (lardist, movement speed >30 mm/s) and during small activity (smldist, movement speed <30 mm/s) during 1 hour measurement using Zebrabox at 28°C in the dark. Data are means from n=9-19 larvae per genotype and treatment condition ±SD. (d) Concentrations of GABA in untreated and 100 µM PN-treated WT and alpl-/- larvae. Data are means from n=5-7 larvae per genotype and treatment condition ±SD. (e) Important features in metabolome of alpl-/- larvae selected by volcano plot with fold change (FC) threshold equal to 2 (x-axis) and t-tests threshold of p<0.05 (y-axis). (f) Accumulation of L-Dopa and vanillactic acid, and decreased level of dopamine, dopamine sulfate (dopamine 4-sulfate and dopamine 3-O-sulfate) and epinephrine in alpl-/- larvae suggest impaired activity of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase. (g) Accumulation of vitamin A (retinol) and decreased level of retinal in alpl-/- larvae. (h) Accumulation of N-methylethanolaminium phosphate in alpl-/- larvae. Data are means from n=5-7 larvae per genotype ±SD (panels E-H). ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01 and *p<0.05.