1. Introduction

All over history, the need for progress has been constant. Long before recorded history, health-related methodologies concentrated on human well-being have used surgery to achieve better therapeutic outcomes. The potential of surgery has been explored throughout history and early surgeons mastered the basics of human anatomy and organ structures. However, evidence of healing behaviors and surgical practices remains a difficult scientific frontier to explore in paleopathology, but exploring such a frontier can help understand medical and health care practices in general, for example, in ancient Egypt [

1]. In fact, ancient Egyptian civilization has provided exceptional written and bio archaeological evidence of medical advances in antiquity regarding infections, trauma, and other conditions [

2,

3]. Further than ancient Egyptian surgeries and up to the present day, the surgical historical timeline has been often studied [

4]. Nowadays, many repetitive practices and skills contribute to a new well-being, through health-related approaches that emphasize safety, comfort and therapeutic results. Recent advances in medicine have made it possible to discover the origins of various diseases and establish approaches to treat them, mainly through surgical interventions. The effectiveness of these operations is directly related to the aforementioned factors related to the patient's health, which largely depend on the visual and tactile abilities of the therapeutic team. These surgeries aim to be minimally invasive (MI) and precisely monitored, thus preserving healthy tissues surrounding the affected areas.

In the previous little decades, surgical procedures have developed quick-progressing disciplines, where innovative skills are quickly initiated and spread out through the different surgical area of expertise. Actually, surgical strategy has progressed considerably and is continuously expanding across open, laparoscopic and robotic surgeries. The Advances in experienced surgical practices have brought many benefits to patients. On the other hand, methodological complexity has increased and the tasks of surgeons have changed significantly.

Since the beginning of surgery, the open technique has been commonly used to “see well” and is still used in situations related to complex anatomy and problematic processes. Laparoscopic surgery has significantly transformed the long-established open surgical methodology, due to the various advantages it presents to patients through a MI procedure [

5,

6]. Such a MI procedure has changed the line of attack to particular body areas by providing an expanded view through a microscopic camera and an illuminated tip of a mini-sized tool. In addition, laparoscopic intervention is concomitant with reduced postoperative distress and faster healing, allowing the management of small clinical episodes [

7,

8]. In addition, it allows important returns, such as improved wound aesthetics and decreased risk of obstruction [

7]. However, laparoscopic procedures using elongated tools as well as 2-D vision exposures could create several surgical ergonomic risks [

5,

9,

10]. Robotic MI surgery avoids such limitations and its use is increasing in different situations such as for hernia surgery. Thus, surgical dexterity and ergonomics are improved thanks to an increased robotic degree of freedom and 3-D vision as well as a general rise in the practice of MI surgeries. Surgical robotic intervention has evolved from, simple passive actions for instrument retraction or holding such as rail-mounted tools or camera routing, to active robotic organizations whose motion span of instruments allows elevated performing and improved strictness for splitting up, and stitching while expending a MI approach [

11]. In addition, it removes tactile tremors and laparoscopic surgery fulcrum effect. Robotic wrist instruments offer multiple degrees of freedom to surmount the restriction of laparoscopic tools that often do not allow its tip to attain the anterior of the tissue [

12] and permit suturing in difficult ergonomic positions.

From the above discussion, the safety, comfort and therapeutic outcomes related to the patient's health, which are the main objective of different surgical technologies, depend on different factors related to the degree of tissue invasiveness, accuracy of tracking, duration of the procedure, speed of healing, etc. These factors are related not only to the patient but also to the medical staff regarding surgical dexterity, ergonomics and ease of execution. In open surgery, almost all outcomes depend largely on the visual and tactile abilities of medical staff. These abilities are, in short, advantageously replaced by less invasive laparoscopic or robotic technologies. The difference between the latter two lies mainly in the way of replacing open surgery and the corresponding ease of execution by staff. These abilities or their substitutes are relatively situation-specific considering the patient, the staff, the operational complexity, and the cost. Thus, despite the clear superiority of robotic technology, laparoscopy and even open surgery have their places in many specific situations.

The prospect of safe, autonomous MI surgery with technology-substituted tactile and visual skills, all under the control of staff (staff in the loop), was a dream of the past and achievable with recent digital intelligence. This ensures the well-being of patient as well as ease and added value for staff. As abovementioned, surgery interventions aim at large to be MI and accurately targeted, thus preserving healthful tissues adjacent to the suffering spots. In addition, staff are expected to provide individualized treatment to patients, taking into account factors such as genetic characteristics, lifestyle, environment and response to medical procedures. In addition to the benefits of MI intervention, the precise position and visual ability could be substituted by laparoscopic technology [

7,

8,

13], robotics [9-11] or advantageously reliable image-assisted robotics [14-17]. Actually, image-assisted robotic surgery seems to be a logical descendant of laparoscopic and robotic surgeries with an obvious enhancement, in skill as well as in the surgeon resources who adopts a more comfortable position for the whole procedure interval. In addition, such robotically image-assisted intervention could be managed as autonomous surgery as mentioned earlier. Moreover, such autonomous procedure could be employed for planning and/or training of staff by using phantoms representing real living tissue body portion concerned. In fact, such autonomous procedure is mainly more advocated for further complex surgeries. Additionally, such intricacy that can be faced in foremost surgical interventions [18-21] or restricted delivery of drugs [22-24] necessitates activities in a constrained zone, to preserve healthful tissues contiguous the disturbed region. In such autonomous robotic controlled interventions, several challenges may be met, associated to the supervision of uncertainty, complexity, and unforeseen hazardous occurrences. Such difficulties can be treated exploiting methods of control centered on paired real–virtual matching [

17,

25]. Moreover, the personalized treatment as well as the interventional specifications mentioned above could be predetermined by a pair of corresponding real and virtual phantoms allowing the confirmation of the intervention outcome. In general, such adapted management could be autonomous [

26], assisted by staff arbitration. Moreover, in perspective, it can include the real patient with the staff in the loop.

This contribution aims to highlight the role of innovative concepts of the moment in improving the conditions of patients, staff and interventional results in the surgical practices of open, laparoscopic, robotic and image-guided robotic surgeries. It also aims to illustrate the roles and needs of each of these types of surgery today. These analyses take into account the precision of the intervention, the safety and the degrees of invasive and autonomous characteristics of the intervention, as well as the comfort of the staff and the healing conditions. The exploitation hence orients and focuses on image-guided interventions and their practice in staff training, preparation and implementation of a possible autonomous intervention. The accuracy of robotic positioning could be improved by reductions in complexity and uncertainty. These can be achieved by matching the actual controlled procedures involved and their virtual procedures. The contribution examines considerations for staff training and/or planning of surgical interventions using real and virtual phantoms, and the use of augmented matched digital twins (DT) for real interventions.

The contents of this article are summarized as follows. In the second section, open, laparoscopic and robotic surgeries are discussed and analyzed. The third section is dedicated to the details of image-guided robotic interventions and their performances in the case of nonionizing scanners and particularly magneto resonance imager (MRI). The fourth section introduces the possibility of a self-sufficient scheme for controlling MRI-assisted interventions and it’s monitoring for managing complexities and uncertainties via DT tools.

Section 5 presents MRI radiofrequency field ruling equations and their implication in, the scanner as well as the verification of MRI-compatibility of inserted robotic tools in scanner scaffold.

Section 6 details DT monitoring involvements in surgical interventions including, projecting, tutoring and implementation with human involvement in increased DT.

Section 7 discusses some notions revealed in the preceding analyses. The last section summarizes the main conclusions of the paper.

2. Open, Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgeries

2.1. Open vs MI Surgeries

Two commonly performed open and MI surgery techniques that have different characteristics and benefits. The open procedure also termed long-established surgery is the customary method that has been expended for lots of years. In this case, generally one sizable cut is fashioned to get into the surgical spot. This opening permits to directly see and get into the organ tissue being worked on. The open technique permits some profitable situations, as distinct and straight sight of the surgical zone, letting accurate handling and skill, and enhanced entrance to intricate or outsized configurations that might be challenging to attain by means of MI practices. Conversely, open intervention as well presents a number of weaknesses. The big cut can steer to further suffering, bigger bleeding, and an elongated healing period matched to MI procedures. Moreover, there is a greater menace of infectivity and a further perceptible big cut trace.

2.2. MI Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgeries

Laparoscopic surgery uses some slight cuts on body surface, routinely of length in the range of cm. Across these little openings, dedicated surgical mechanisms and a miniature camera named laparoscope are introduced. This technology evolves, as mentioned before, different benefits related to MI incisions and enlarged laparoscope vision of operation zone. They respectively help reduce pain, bleeding, healing time and visible scars, as well as precise and manageable engagements. Laparoscopy is very commonly used in abdominal surgeries and also as diagnostic tool [

27]. Conversely, laparoscopy procedure might be incompatible with all cases concerning patients or surgery types [

28] and needs in general dedicated tuition and instrumentation, in specialized healthcare services. Actually, specific procedures behaving intricate as neurosurgery or wide-ranging might yet necessitate open technique or more sophisticated robot-assisted laparoscopic techniques [

29]. Note that the difference between laparoscopy and the robotized option pertain mainly to the medical staff regarding surgical dexterity, ergonomics and ease of execution.

When it comes to robotic surgery, the goal is generally not to take the place of the surgeon but to increase his ability to care for the patient. The robot is therefore a surgical device, which is managed by computer, where its control is commonly mutual between the surgeon and the computer. Medical robots are therefore often referred to as surgical aides [

30]. Surgical robots involve different practiced or prospective categories depending on their concept and corresponding appropriate types of surgery [

31,

32]. The first brand is planned remotely by the surgeon and involves laparoscopic operation, robotic-supported suturing and tissue handling [

29]. The second is controlled through staff supervision, which reflects better abilities contrasted to the last one and can be used for surgical removals as e.g. (hysterectomy, prostatectomy or cholecystectomy) [33,34 ]. The third category is the joint control of surgeon skills and robot capability and can be used in surgeries such as (retinal, sinus, orthopedic) [

35,

36]. The fourth involves more autonomous robotics administered by staff and could be used e.g. for (microsurgery, neurosurgery, tumor ablation, anastomosis) [

37,

38]. The last category involves an entirely autonomous surgical robot executing complex surgeries devoid of direct staff interaction (but still surveyed) and could be used e.g. for (biopsies, transplantation, intricate reconstructive surgeries, microsurgery in sensitive bodily zones) [

39,

40].

3. Image-Guided Interventions

It is clear from the discussion in the last section that both open and laparoscopic surgery options each have a number of advantages and disadvantages. In summary, the open strategy allows for direct entry and improved panorama but is accompanied by a larger incision and slower healing, while laparoscopic option allows for smaller incisions, faster healing, and less visible scars but may not be appropriate in all circumstances. As mentioned earlier, the choice of surgical strategy depends on several factors, including the patient's disease, the complexity of the procedure, and the expertise of the staff. Only after a comprehensive assessment can the most appropriate choice be offered to the patient, evidence-based decision making [

41]. We have also seen that robot-assisted laparoscopic and robotic techniques allow for more complex problems to be performed with improved surgical dexterity, ergonomics, and staff ease. An advanced extended strategy of such assistance going further towards task enhancement could be image-guided robotic surgery, thus exploiting the precision of robotic positioning and high-resolution 3-D vision thanks to scanner imaging. In fact, if we only consider vision and positioning skills in surgery, open surgery uses external light projection and the surgeon's hands, laparoscopic surgery replaces external light projection with internal light projection, robotic surgery uses pre-images and computer positioning, and image-guided surgery uses instantaneous imaging aiding in immediate positioning.

The MI image-guided robotic interventions in general improve patient comfort and security along with precision in execution and therapeutic effectiveness. Moreover, such approaches can work at practically all body zones, involving surgery or implanted restricted drug release. The scanner type plays an important role in the procedure. Several imagers can be employed in image-assisted interventions. Still, even that the imaging processes are adapted each to specific cases [

42], those employing ionizing emissions as positron or X-ray seem inappropriate for medical treatments of wide intervals as in the case of complex image-guided surgeries. Thus, scanners fitting such elongated surgeries are those reflecting nonionizing features, specifically ultrasound and magnetic resonance [43-45]. The scanner is supposed to deliver 3-D high-resolution panorama of tissue details alongside interventional robotic tools. Thus, the robotic support performs inside the scaffold of the imager together with tissue involved part, permitting actions administration in a closed-loop manner, pursuing tissue topology, locating tools and monitoring their actions. In such a way, the scanner capacities and the robot skills are fused in an effectual task.

The two nonionizing scanners can achieve the abovementioned duty with specific restrictions for each. The ultrasound scanner can only perform in airless and boneless windows [

16,

17] while MRI requires a scaffold with a free electromagnetic field (EMF) environment [46-51] but can work universally in all organs of the body. In addition, ultrasound has appropriate flexibility and cost, while MRI, which allows excellent soft tissue images, has a more expensive and complex use. The choice between the two scanners therefore depends on the circumstances. However, when patient comfort and safety are important, procedures, such as brain surgery, should use MRI-guided robotics. Note that, MRI offers an unequaled contrast permitting the imagining of tumors besides other anomalies imperceptible by other imaging scanners. It reflects exact 3-D vision competency, comprising multimodal imaging, for instance, blood stream, temperature, and tracking of biomarkers. Thus, under such conditions, the administration by an MRI assistance of robots would permit an outstanding intervention.

Considering the universal (all body parts) use of MRI-assisted surgery, to fruitfully conduct an intervention, the MRI meets important implementation issues mainly related to involvement of three different EMFs in its functioning. These EMFs exhibit dissimilar natures (strength and frequency), displaying sensitive responses to external electromagnetic (EM) noise, and forcing a limited position zone within the imaging configuration.

4. Control and Monitoring of MRI-Assisted Interventions

Intraoperative image-guided surgery that meets safety demands related to scanners and surgical procedures in general uses MRI and ultrasound scanners [

16,

17,

19]. MRI scanners are increasingly being used in surgery, mainly because of their greater ability to distinguish tumors from healthy tissue in procedures involving tumor removal [52-55]. As abovementioned, MRI scanner is EM-sensitive. In addition to its possible disruption by external EMFs, the introduction of external substances could disrupt its operation; thus, robotic components introduced into the scaffold, near tissue parts, must be MRI-compatible, i.e. without magnetic or conductive constituents. However, robotic engagements typically require high-performance actuation actions, while a small number of actuator types behave in an MRI-compatible manner. One potential class of actuation mechanisms that are generally compatible with MRI exploits piezoelectric materials, which come in different types. Further detailed information about these actuators, their configurations, ingredients, fabrication, research, and uses are presented elsewhere, for example in [56-65]. These tools are devoid of magnetic substances and made of dielectric piezoelectric materials, but equipped with thin conductive electrodes necessary for their excitation. In fact, piezoelectric materials are presumed to be compatible with MRI, while the compatibility of conductive electrodes depends on their structural configuration and therefore needs to be verified. This issue will be addressed in

Section 5.2.

4.1. Closed-Loop Control of Image-Guided Robotic Actions

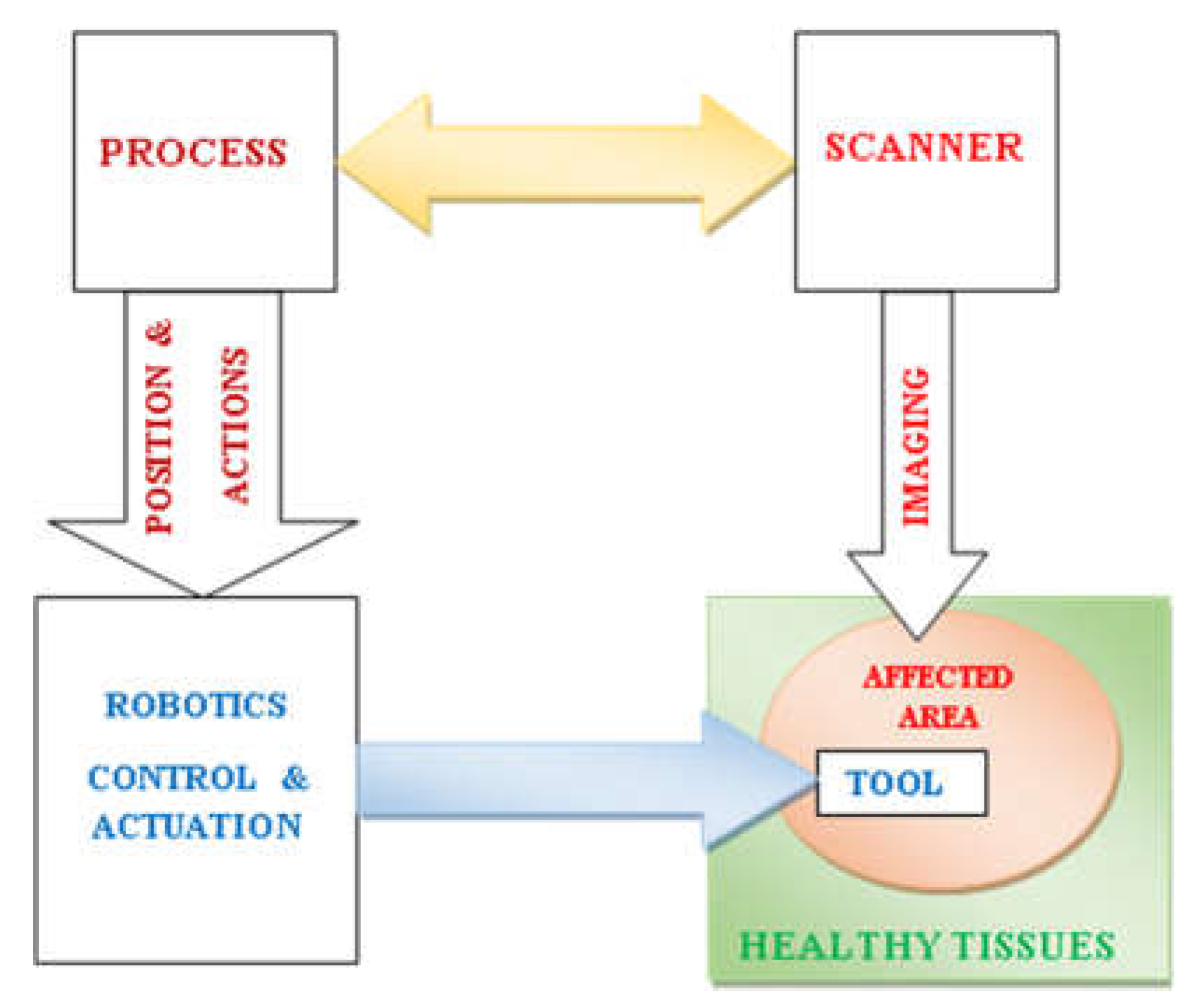

As mentioned before, patient safety is associated to the restriction quality of therapy to the distressed zone in the course of surgery. Such correctness hinge on the actuation precision of the surgical tool and its localization in the space. Consequently, the requirement for such high-quality spatial pursuing indicates an image-controlled position detection. Such clauses entail a joint configuration functioning autonomously, as illustrated by the schematics of a self-controlled surgical setting in

Figure 1. Such organization consist of scanner, tissue-touched zone, surgical tool, position and actions processing, and robotic control and actuation [

16,

17]. The precision involved in such a closed-loop control procedure, related to position localization and actuation quality, would be shaped by various confounding features, including the degree of complexity of the combined constituents of the procedure, the associated uncertainties, and various unexpected peripheral risk occurrences. Only the reduction of such perturbing features permits a consistent control.

4.2. Compatibility and Control Perturbations

As mentioned above, MRI scanners are subject to disturbances due to exposures to external EMFs or the introduction of substances that disturb their own fields. On the other hand, the control of their robotic assistance may involve disturbances due to the complexity and uncertainties as well as unexpected external risk incidences. This section aims to analyze the reduction of these various disturbances.

4.2.1. MRI-EMFs and Compatibility

This section aims to illustrate the problem of MRI-compatibility of inserted materials related to robotic tools in the scanner scaffold. Such compatibility is associated with image fidelity and accuracy. An MRI-compatible material is supposed not to alter the image.

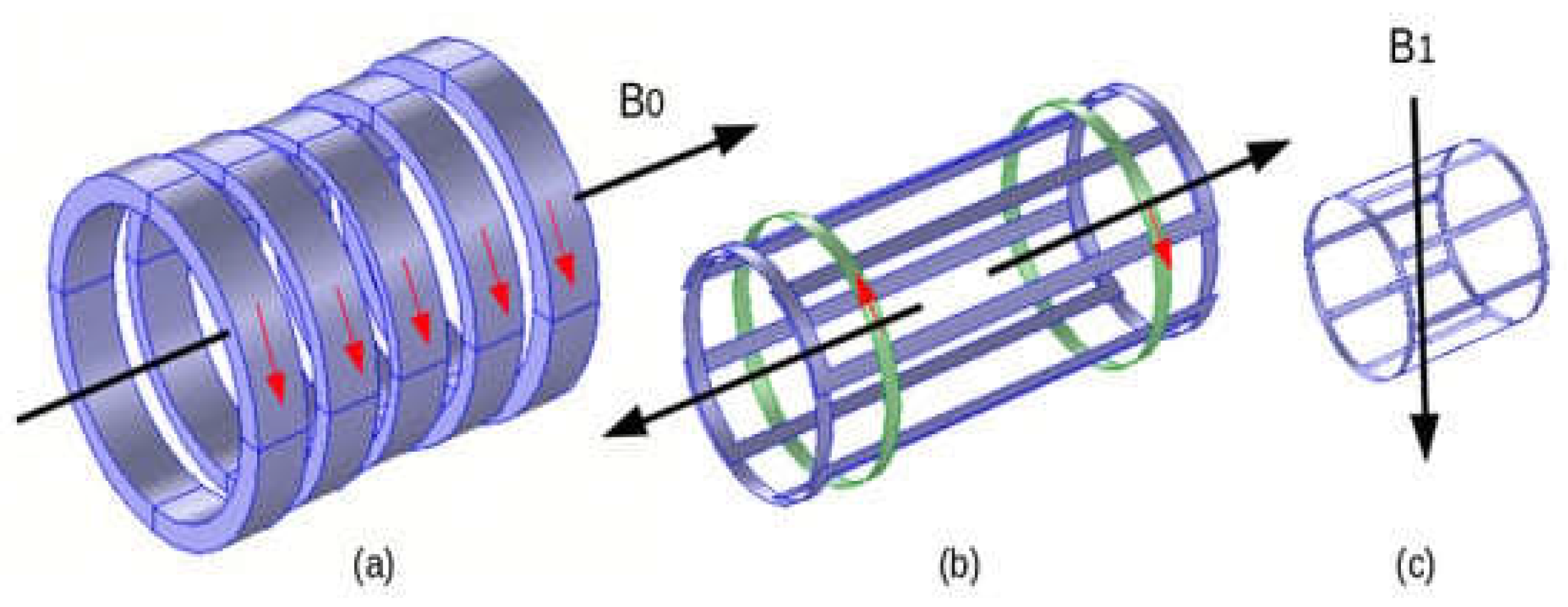

An image generated in an MRI scanner is shaped by signals occasioned by the connections of magnetic fields with living tissues. Thus, three different fields are exploited to construct 3-D images. A high static field engendering a vector of magnetization in tissues aligning their protons and quantifying their intensity. Three low-frequency repeated gradient fields space-positioning aligned tissues protons fashioning a 3-D spatial reconstruction. Finally, a radiofrequency (RF) field exciting the tissues vector of magnetization allowing its revealing by the scanner, which can be processed and converted into images [

16].

Actually, MRI, image the hydrogen atoms nuclei that are detained within the body. A hydrogen nucleus is a proton, which is a mass of positive charge rotating on itself around an axis. Protons are arbitrarily oriented in tissues, and spin individually. Therefore, they display zero magnetic field performing out of phase. Considering the MRI theory, tissues protons require three arrangements inside the concerned tissue: aligning protons in a settled direction, rotating them together, and localizing their space distinct origin. These three arrangement could be respectively realized by: the static magnetic field B

0, excitation by wave RF field B

1 having a frequency corresponding to the natural frequency of protons’ rotation f

L (Larmor frequency) allowing a resonance action, and 3-D space gradient G(x, y, z) applied to the field B

0, permitting the position distinct values of B

0d (x, y, z) = B

0 + G(x, y, z). Note that the value of f

L is function of B

0 and equal to 42.5 MHz per tesla, and the corresponding position distinct values f

Ld (x, y, z) will be function of B

0d (x, y, z). As mentioned before the three fields used in MRI, static, gradient and RF, differ in strength, frequency and presence while operating. Thus, B

0: 0.2–10 T, 0 Hz, permanently present; gradient: 0–50 mT/m, 0–10 kHz, pulses of few ms; B

1: 0–50 μT, 8–300 MHz, (amp. mod. pulses) of few ms. A representation of the three MRI field components is shown in

Figure 2.

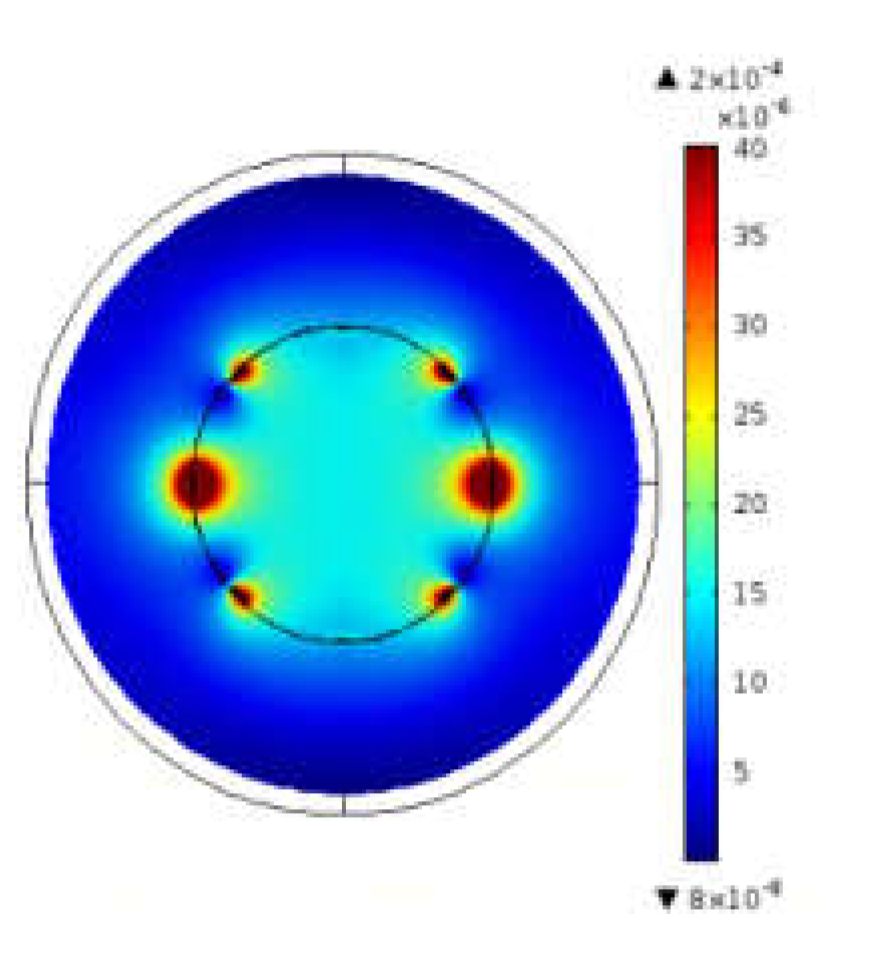

The components producing the three fields are normally protected. Those of static and gradient fields are compensated and regulated. The arrangement of RF field (often birdcage form, see figure 2.c), which is directly related to images, is the most exposed to perturbations mainly due inserted external matters. Thus, the MRI-compatibility of a matter inserted in the scanner scaffold (in the birdcage) is determined by its effect on the distribution of the field B1, i.e. for an MRI-compatible matter, the field distributions without or in presence of the matter are identical. Such compatibility could be checked from EMF computations of RF field B1 distribution in the birdcage, see section 5.2.

4.2.2. Complexity and Uncertainty Handlings

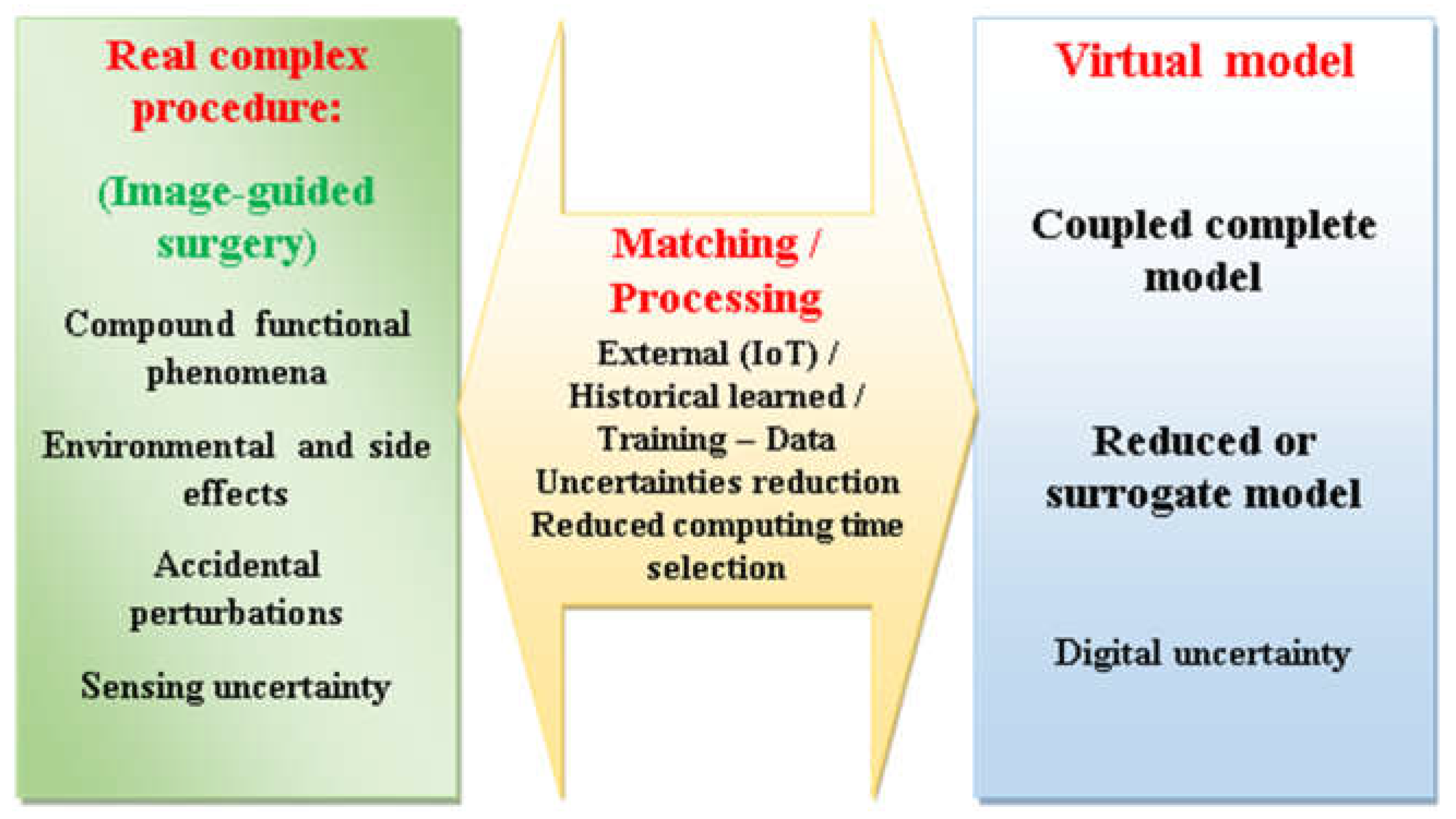

As stated previously, the precision implicated in the image-assisted robotic control associated with actuation and window positioning is conditional on troubling dynamics, including the complexity degree of different involved blended components, the related identification uncertainties, and unusual outer threat occurrences. The reduction of such potential troubles as well as the consideration of specific individual process information are indispensable for the correct functioning of the controlled image-guided procedure. Such objectives could be accomplished by monitoring the involved parameters in a matched real-virtual pair by means of a digital-twin (DT) tool [

66]. A DT is characterized by an integration of data within a pair of a physical event and its digital replica in a two-way manner. Such approach is practiced for managing of complexity in controlled procedures [

67] and structured as a physical-virtual pair allowing self-adjusting behavior. Thus, the physical side of the pair delivers processed sensed data to the virtual side while the last transmits control commands to the physical side. This self-adjustment matching helps reduce pair uncertainties and unexpected randomness in process control. It thus appears clearly that the management of complexity, uncertainties and randomness by DT responds well to the troubling dynamics of image-assisted robotic control mentioned above. Note that, generally DTs can be planned at the echelons of a structure, a substructure or a particular component and employed for diagnostics, prediction, procedure conditions monitoring, optimization and risk evaluation [

68].

Recently, DT has been gradually introduced into the health sector, which has allowed its use in different treatments to be gradually explored, thus enabling the renovation of daily life, health, connected monitoring and prolonged management of disorders. Many cases have been studied for this purpose, see for example [69-79].

4.3. DT Supervision of MRI-Assisted Interventions

The detailed DT supervision organization of an image-assisted robotic control is fashioned in this section. In general, concerning the abovementioned communications between the DT sides, the processed data of the physical side delivers detected information compared and adjusted, by external “IoT” data and learnt historical one. The occasioned outcome once trained as data analysis is conveyed, with an appropriate model reduction indication, to the DT virtual side. Actually, a swift communication (matching) between sides of DT necessitates a faithful virtual model but with undersized execution time. Thus, the comprehensive coupled model, which realistically represents the physical procedure, would be reduced allowing moderate computation time however preserving the picture of the real procedure. Management of an image-guided robotic control employing a DT pair fulfills an operational adaptive control procedure involving the real procedure matched with a reduced virtual model [

80].

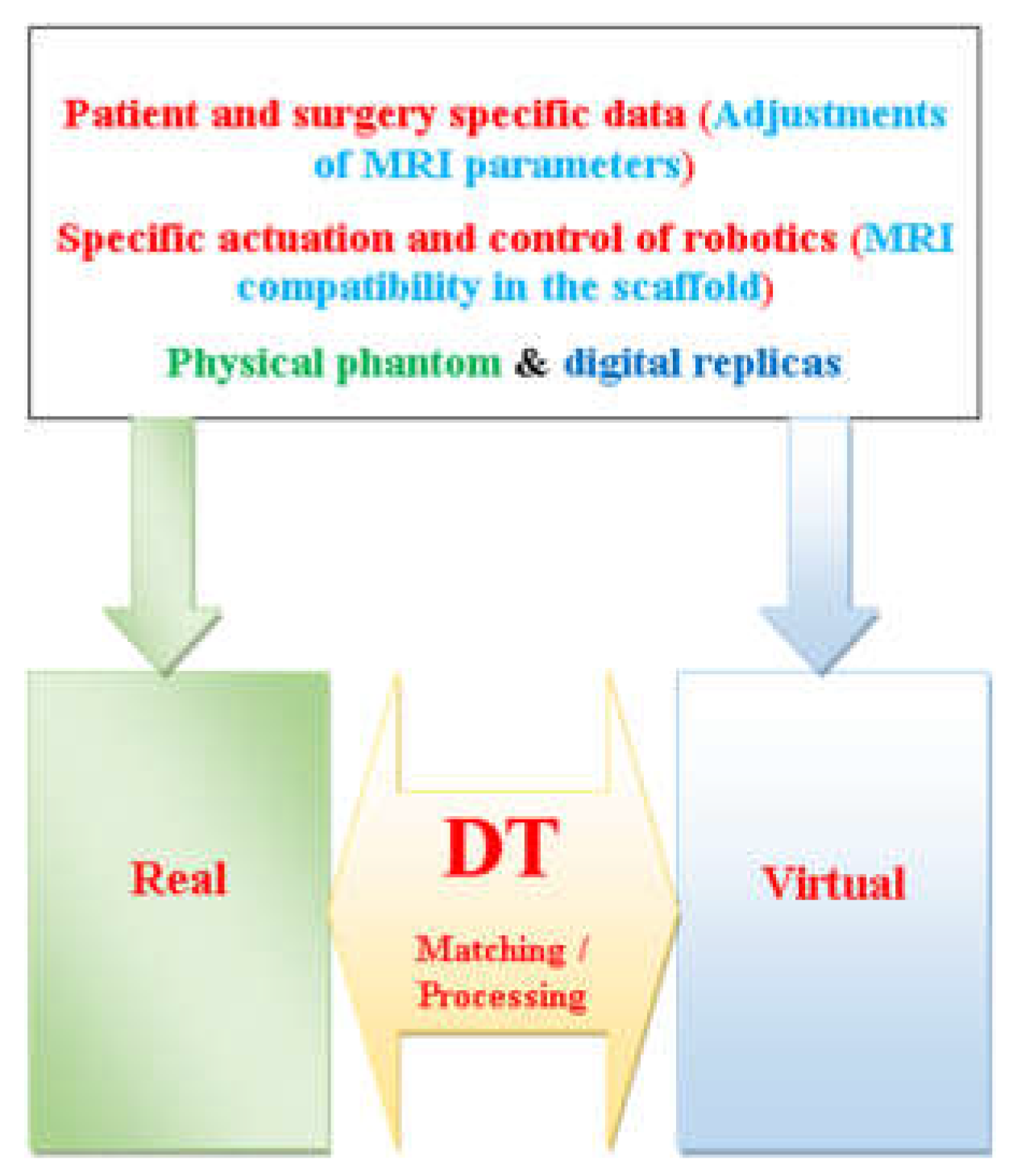

Figure 3 illustrates schematically the features of a DT monitoring an image-assisted robotic surgery. Such procedure monitoring could be used for staff training, predictions using physical phantoms and their digital replicas, or a real patient–virtual replica model, involving self-ruling matching with staff in the loop.

The coupled model includes all components and actions of the image-guided robotic surgery procedure illustrated in

Figure 1, namely the MRI scanner, tissue-affected area, surgical tool, position and action processing, robotic control and actuation. A significant part of the procedure is related to the MRI imaging involving the tissues and the surgical robotic tool. As mentioned earlier, the two components of the MRI magnetic fields related to the static and gradient fields are compensated and regulated, while the RF field arrangement is directly related to the images. This occurs through the processing and transformation of the field signals following the excitation and restoration of the B

1-wave RF field. Thus, the 3-D RF field distribution in the birdcage comprising the tissues and the tool enables the outcome of the imaging process as well as the control of the MRI-compatibility.

5. MRI RF Field Ruling Equations

As abovementioned, the excitation and restoration of RF wave field in the MRI scanner produce a 3-D field distribution permitting after signal processing and image conversion to obtain a 3-D image of tissue details including robotic surgical tool. The mathematical equations governing such RF EMF phenomenon are based on Maxwell’s local comportment differential form of the general EMF equations [

81]. In the situation of RF EMF excitation of living tissues, we can use the next formulation of EMF harmonic fields:

In the above Equations (1–4), H and E are the vectors of the magnetic and electric fields in A/m and V/m, B and D are the vectors of the magnetic and electric inductions in T and C/m2, A and V are the magnetic vector and electric scalar potentials in Wb/m and volt. J and Je are the vectors of the total and source current densities in A/m2, σ is the electric conductivity in S/m, and ω is the angular frequency = 2πf, f is the frequency in Hz of the exciting EMF. The symbol ∇ is a vector of partial derivative operators. The magnetic and electric comportment laws, respectively, between B/H and D/E are represented by the permeability μ and the permittivity ε in H/m and F/m.

The solution of the above EMF equations should count for particular features of involved structures such as geometrical complexity, matter inhomogeneity, variables nonlinear behaviors, which indicate advanced computational approaches. Fulfilling such characteristics imposes matter local answer insinuating the employ of discretized 3-D methods as finite elements method (FEM) or comparable approaches (BEM, FDTD, etc.) [82-89].

Such a solution could be used, to verify the MRI-compatibility of the different objects introduced into the scanner, using EM compatibility (EMC) routines [

16].

5.1. Models in DT

In the present contribution the term model is employed to designate several issues. These involve physical tissue representation model (physical phantom), digital tissue virtual model (virtual phantom), different procedure components models, compound coupled procedure model and reduced procedure model. For example a DT procedure as this given in

Figure 3 used for prediction (pre-interventional) task, would involve a physical and virtual phantoms in addition to a procedure coupled model [

90,

91] and its reduced or surrogate [ 92,93] model version.

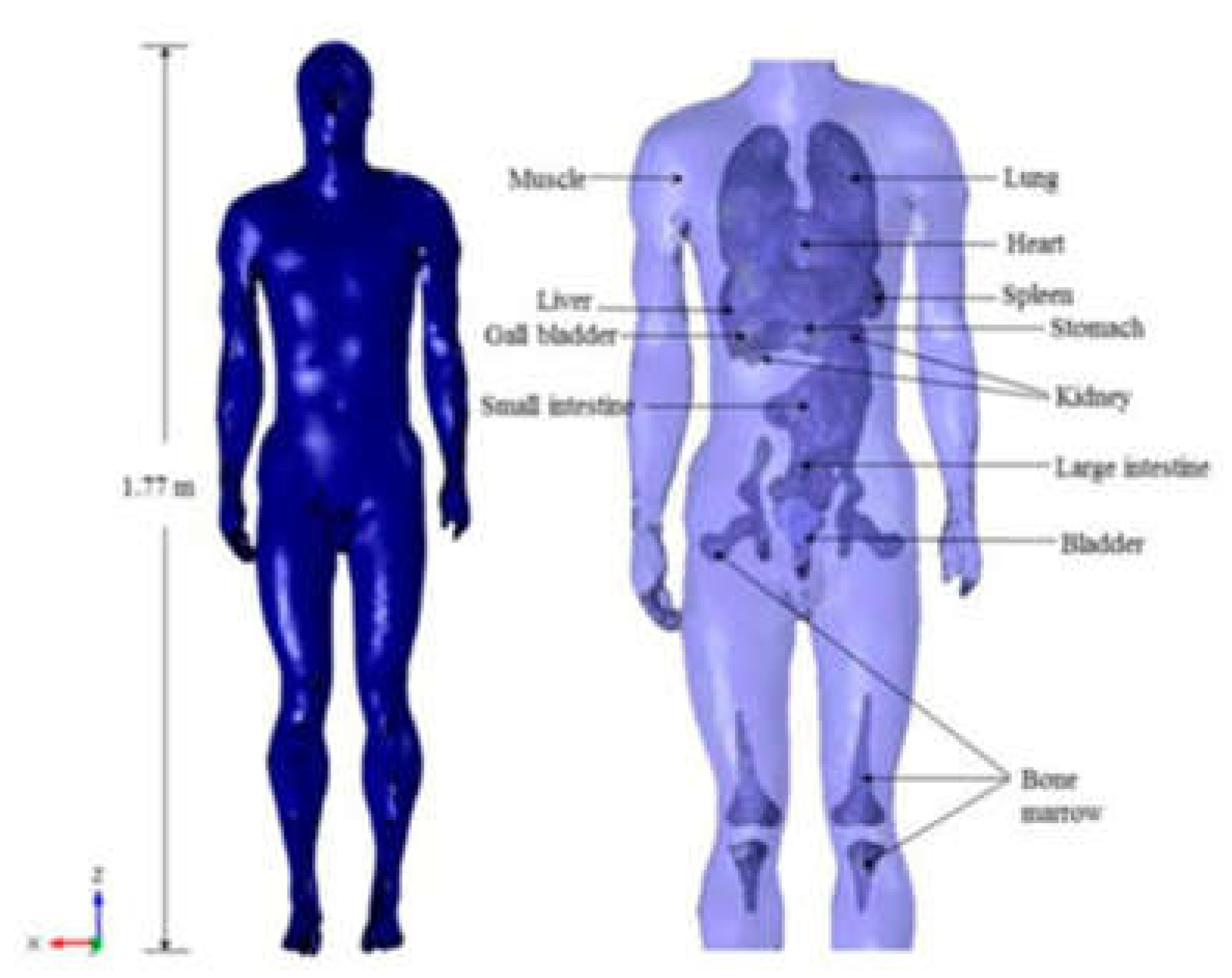

Virtual numerical models (digital phantoms) can personify the living tissue body part involved in the surgical procedure. Important features of these models should correspond to the nature of material and organic properties, geometric form and consistency with the computational approach used. Diverse body copies with living tissue features exist in the literature [94-99].

Figure 4 displays a structural body with its different body parts and tissues [

100].

5.2. EMC Analysis in MRI Setting

As mentioned in

Section 4, the MRI scanner displays sensitive responses to EM noise due to exposure to external EMFs or insertion of EM-sensitive materials into the scanner scaffold, both of which can disrupt the scanner's own EMFs. The MRI EM-sensitive matters are mainly ferromagnetic and conductive materials.

Considering that the static and gradient fields are compensated and regulated as mentioned in section 4.2.1., the interaction of a material introduced (such as those constituting the robotic structure) into the MRI scaffold with the RF B1 field can be examined. Via such an analysis, the compatibility of the material with MRI can be verified or established. Thus, the EMC analysis allows to identify the impact of the insertion of external materials into the MRI atmosphere on the 3-D distribution of the B1 field obtained from the solution of equations (1-4) that is image correlated. The equations are solved for a given field excitation source amplitude and frequency with the inserted stuff behavior laws parameters σ, μ, and ε.

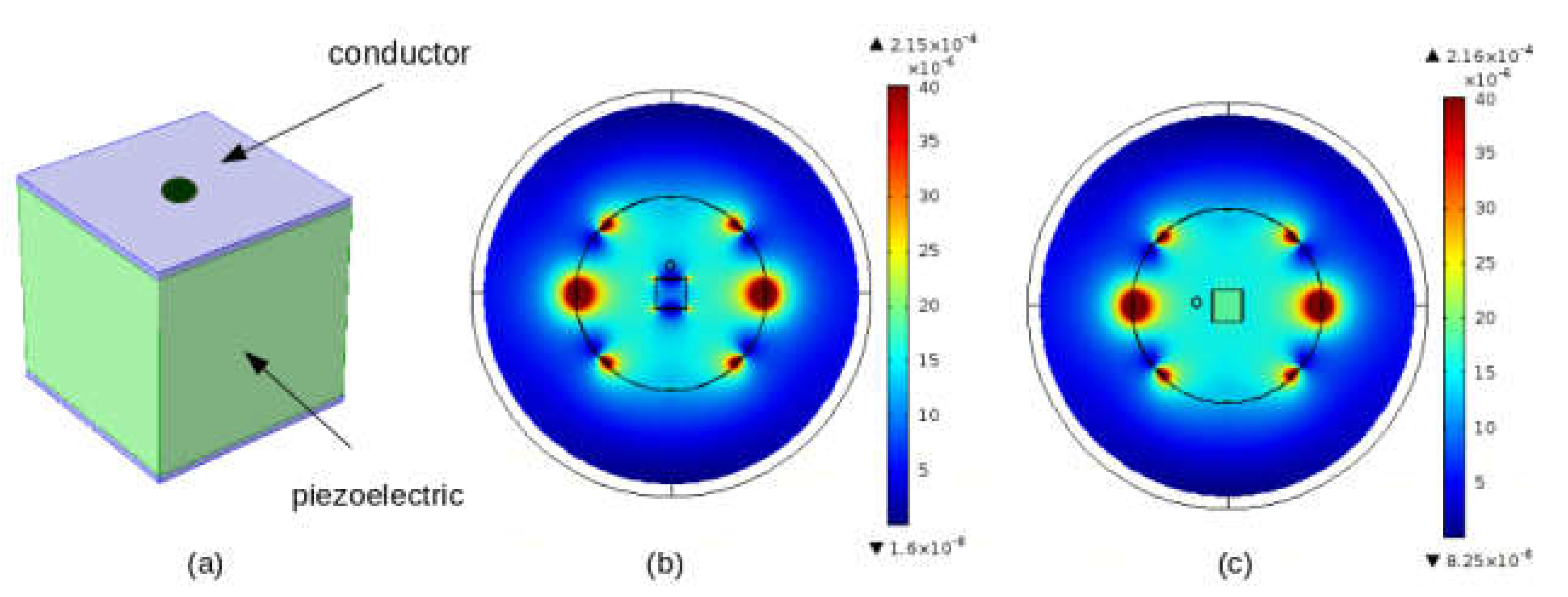

As mentioned in

Section 4, typical MRI-compatible actuation mechanisms are those using piezoelectric materials, which are free of magnetic substances and made of dielectric piezoelectric materials (assumed to be MRI-compatible), but equipped with thin conductive electrodes (their MRI-compatibility is subject to their structural configuration) necessary for their excitation. These conductive electrodes could be responsible for the disturbance of the 3-D distribution of the RF B

1 field, due to their eddy currents induced by this field. These currents mainly depend on the conductive surface perpendicular to the field. Such occurrence could be used in the actuation perspective to reduce disturb in the distribution of RF field [

17]. Perturbation control could be achieved by matching the field distributions with and without the introduced structure.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show such demonstration (see [

17] for more details).

Figure 5 shows the RF field B

1 distribution (vertically directed) in the section of an empty birdcage within the tunnel of the scanner.

Figure 6 displays a case of a cubic piezoelectric covered by skinny electrodes on two opposite surfaces of the cube typifying a simple piezoelectric actuator (

Figure 6a).

Figure 6b,c show the distributions of the field in the two situations with the electrodes perpendicular and parallel to the field direction respectively.

Note that the conductors effect, in the case (parallel to the field), is drastically reduced (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6c are almost same). These results illustrate a simple qualitative example of possible EMF noise image perturbation and thus actuation perspective by reducing such disturb.

6. DT Monitoring Involvements

6.1. Projecting of Medical Arrangements

Following the DT supervision of MRI-assisted surgery discussed in

Section 4.3., such supervision requires planning to adjust and verify the various medical pre-arrangements. This would be accomplished by using physical phantoms and their digital replicas in the DT tool. These pre-arrangements include patient and surgery specific data, corresponding adjustments of MRI scanner parameters, MRI compatibility of objects inserted into the scaffold, and related actuation and control of robotics specific to the surgery involved. Such pre-arrangements are illustrated on

Figure 7.

6.2. Perspectives for Implementation, and Tutoring

The planning mentioned in the last section allows to regulate the smooth handling of the intervention and the expected adjustments involved in the therapeutic procedure carried out. Thus, the upcoming surgery involving the patient could be performed in a decent imaging-assisted joint atmosphere, under staff supervision, or possibly as a stand-alone DT monitoring intervention involving staff in the loop. In addition, such preparation permits staff to forecast the disturbances that patients might undergo through the intervention. Such disorders might be associated to robotic surgical tools, implementations or drugs. Moreover, DT patient personalized planning task permits staff, in a harmless manner without patient, to perform processes, arbitrate decisions, and be aware of likely mistakes of evaluation [17,101-103].

Regarding living tissues of different parts of the body, they are represented in the two wings of the DT, as mentioned before, by physical phantoms and their digital replicas (see

Figure 7). The tissue behaviors in these models (physical and digital) are of static character, which might be acceptable for some body organs in the context of specific procedures. However, these models are supposed to take into account the biological belongings of real tissues in general [

104]. A typical example is the case of soft tissues moistened by fluids that support and manage them. The behavior of soft tissues corresponds to a complex active dynamic behavior corresponding to the mechanics of displacement and deformation of living soft tissues [

105,

106,

107,

108,

109]. In fact, dealing with such sophisticated mechanical behavior requires adapted behavior laws and numerical approaches, which can only address such a problem in an estimated manner [

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99].

6.2.1. Human Involvement and Increased DT

The human-robotic association materialized by the concept of DT with personnel in the loop allows advanced image-assisted supervision of surgical interventions, thus reducing the risk to the patient and ensuring a reliable end for the personnel [110-112]. Moreover, artificial intelligence (AI) exercises in such therapies help to reduce the complexity of data acquisition and post-processing and to perform recurring planned training tasks [

113,

114]. Furthermore, the intervention can be significantly improved through expanded human-robot connections, advancing the entire arrangement through augmented reality (AR)-assisted robotic actions. Thus, AR combined with MRI scanner can minimize risks in complex surgical procedures, such as tissue damage, hemorrhage, and post-interventional trauma. Besides, DTs can perform an important job in AR-assisted robotic interventions. Thus, the possible cause of the disorder and its remedy action could be accurately identified via individual patient testing through deep learning databases. Moreover, several additional benefits of AR-DT combined are related to improved accuracy in suturing, gluing, and fixation compared to manual tasks [

115,

116,

117,

118,

119].

6.2.2. Training Potentials

DT has the potential to transform patient healthcare by progressively bringing personalized and data-driven medical care. Its use is part of digital care and is generally used in individualized medical treatments, which can be disease monitoring and identification, training, or interventions. DTs are often associated, as mentioned earlier, with AI and AR tools, as well as virtual reality (VR). Similarly, VR tutoring improves the ability to imitate everyday training situations with the ability to properly measure execution. Tutoring mainly involves planning a personalized situation or researching new treatments as part of general training.

The basic DT training of commencing staff is connected to the establishment of virtual anatomy and body models to permit performing, skill augmenting, and polishing their perception of tissues of the body. DT common staff training comprises performing scenarios, attainment vital characters, administrating drugs, and fronting urgent circumstances. This can be associated to patient interests, e.g., cardiac attacks, or environmental situations, e.g., fires. In addition, DT allows training in the use and protection of therapeutic tools and infection management procedures [

69,

70]. In addition, Training of DTs allows staff to observe the progression of disorders and adapt treatment policies, selecting the most relevant therapy. Such training in individualized planning helps to advance premature diagnosis and explore new treatments or interventions [

120,

121].

7. Discussion

In a general analysis of different surgical techniques, the results of this review highlighted the importance of minimally invasive, non-ionizing and precise interventions. In addition, taking advantage of an appropriate digital environment allows staff to plan, predict, prospect, train and execute with staff in the loop, surgical activities in general. Following the above analyses, some points deserve further discussions:

The analyses carried out in this contribution focused on open, laparoscopic, robotic and image-guided surgeries. The only hierarchical classification of these techniques is related to their chronological entry into medicine. The chronological classification is often related to technical innovations such as optical fibers, robotics, numerical control, DT, etc. and mainly to their use in medicine, see for example [

122,

123]. Each of these surgical techniques has today its own specificity and impact depending on the operation concerned and the organ involved. This article in addition has highlighted some potentialities offered by the option of image-assisted surgery and by DT monitoring of the controlled procedure involved.

Regarding the technical innovations mentioned in the previous point, these are often presented as innovative because they find a new modern application even if their notion existed before, for example, the association of earlier neural networks and recent AI. In the context of this article, the recent concept of DT does not escape this observation. The action of DT based on observation and iterative deduction by imitation introduced by Grieves in 2002 [

67] which uses a strategy identical to the oldest method of survival, namely camouflage described by Bates in 1862 [

124], which allows creatures to blend into their environment thanks to adaptive matching.

All the mentioned types of interventions in the paper are assisted by offline, computerized or real-time imaging strategies. In open surgery, a pre-made image is exploited offline by the staff, in laparoscopic and robotic surgeries, a pre-made computerized image is involved, and real-time imaging is concerned in image-guided robotic surgery. As for autonomous closed-loop procedures including imaging, they can be used generally in computerized or image-assisted robotic surgeries.

The concept of DT mentioned and practiced in this article corresponds to different brands of DTs. Indeed, these emphasize the progression of the concept from simple to more sophisticated by adding more capabilities in between. Initially, DT was defined as a static twin, which was followed by twins labeled, mirror (functional or dynamic), shadow (self-adaptive or real-time), and intelligent (self-adaptive augmented by AI). Each of these categories is well suited for specific uses. For example, dynamic for intervention planning, self-adaptive for biomarker and drug improvement, and intelligent for strategy and care alignment, and for individualized treatment.

In the analysis of DT monitoring (tracking), the notions of complexity, fast matching, coupled models and reduced models have been addressed at different places. In fact, these four notions are related. A correct matching of a real complex procedure with its virtual replica implies taking into account the real complexity in the virtual model. Thus, the interdependent compound phenomena involved in the complex procedure must be mathematically modeled in a coupled manner [

125]. The problem of such an exact full coupled model is that its huge execution time is antagonistic to a supposedly fast real-time matching. One must then find a reduced coupled model behaving physically exactly but with a reduced execution time. In summary, the physical complexity introduces a mathematical complexity and for a fast matching, the latter must be reduced but can still represent the former. Thus, reducing a model comprises hurrying its execution while degrading its precision as slim as possible [

126]. The dilemma is then often to attain the boundary among saving time and deteriorating correctness. A reduced (surrogate) model is therefore substituted [

92,

93] for the superior model to obtain a pre-sizing. In addition, one can exercise non-intrusive stochastic methods (e.g., kriging and polynomial chaos) [

127,

128] that spend 3-D FEM computations with a contained set of realizations (training trials), thus offering efficient (reduction) metamodels.

The three different MRI fields B

0, B

1 and G are assumed to be protected and secure. In fact, the use of MRI scanners is normally safe for patients and medical personnel in the case of using common scanners with moderate efficiency (static field strength and gradient output). For recent high-performance scanners, some traumatic concerns could be observed. Actually in such circumstances, the EMFs of the scanner can trigger possible uncomfortable side-effects for patients or nearby personnel. The RF B

1 field reflects a trivial intensity for a negligible duration and the corresponding tissues induced currents are insignificant. The pulsed gradient field G produces a variable electric field, which can create unpleasant peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS), especially in modern gradient coils with high output (intensity and scanning speed) [129, 130]. In fact, efficient gradient coils produce shorter cycles with higher resolutions, thus amplifying their output, which leads to a shorter imaging duration. These PNSs can trigger sensations of muscle compression, irritation, or numbness. The static B

0 field is normally safe for common field strengths around 1.5 T. Recently, due to improved performance, ultra-high-field (UHF) MRI scanners (above 7 T) have been introduced [

131]. These UHF scanners induce low-frequency currents in the conductive tissues of the moving body inside or near the scanner [

132]. These induced currents and their fields trigger uncomfortable sensations such as falling sensation, light flashes, loss of balance, or muscle tremors (PNS). In addition, the interaction between a strong B

0 field and living tissues creates magnetic induction effects due not only to the induced currents but also to Lorenz forces [

133]. These forces correspond to charged particles moving through the static field and experiencing forces in a direction perpendicular to the motion. These forces depend on the speed of movement and the field intensity, and could therefore be important in tissues for UHF scanners. Different disorders could arise due to such forces as for example magnetic vestibular stimulation (MVS) [

134]. A common reported significant side-effect caused by these forces is dizziness which can eventually lead to nausea [

135], they can also cause involuntary eye motion and other effects [

136].

8. Conclusions

This contribution has analyzed and paralleled open, laparoscopic, robotic and image-guided robotic surgical interventions with regard to patient well-being, staff efforts and assignment reliability. Thus, surgeries targeted to be minimally invasive, precise and safe. The specificities of each type of surgeries have be highlighted. Each of these surgical techniques has today its own impact and worth depending on the operation concerned and the organ involved. Considering the general targets and different advantages of these surgery types, we hence focused on image-guided interventions and their practice in staff training, preparation and implementation of a possible autonomous intervention. In order to enhance the accuracy of robotic positioning the reductions in complexity and uncertainty have been managed by matching the actual controlled procedures involved and their virtual replicas through digital twins. Thus, the staff training and/or planning of interventions using real and virtual phantoms have been analyzed. As well, the use of augmented matched digital twins for real interventions has been discussed.

To end with, like open, laparoscopic and robotic surgeries, robotic image-assisted surgery has a clear potential in complex and restricted positioning procedures, which could be augmented by its monitoring via digital twins in a computerized environment. In addition, such digital background is well adapted for planning, predicting, prospecting and training of surgical activities in general.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tondini T, Isidro A, Camarós E. Case report: Boundaries of oncological and traumatological medical care in ancient Egypt: new palaeopathological insights from two human skulls. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024, 11, 1371645. [CrossRef]

-

Bestetti, RB; Daniel, RF; Geleilete, TM; Almeida, ALN. From Shamans to Priests of Sekhmet: A Review of the Literature in Search for the Origins of Doctors in Ancient Egypt. Cureus. 2024, 16(8), e67195. [CrossRef]

- Hernigou, P; Hosny, GA; Scarlat, M. Evolution of orthopaedic diseases through four thousand three hundred years: from ancient Egypt with virtual examinations of mummies to the twenty-first century. Int Orthop. 2024, 48(3), 865-884. [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J. The Evolution of Surgery: A Historical Timeline. A History of Surgery. Verywell health. Available at: https://www.verywellhealth.com/the-history-of-surgery-timeline-3157332. (Accessed January 3, 2025).

- Tetteh, E; Wang, T; Kim, JY; Smith, T; Norasi, H; Van Straaten, MG; Lal, G; Chrouser, KL; Shao, JM; Hallbeck, MS. Optimizing ergonomics during open, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted surgery: A review of surgical ergonomics literature and development of educational illustrations. Am J Surg. 2024, 235:115551. [CrossRef]

- Alkatout, I; Mechler, U; Mettler, L; Pape, J; Maass, N; Biebl, M; Gitas, G; Laganà, AS; Freytag, D. The Development of Laparoscopy-A Historical Overview. Front Surg. 2021, 8, 799442. [CrossRef]

- Barrios, EL; Polcz, VE; Hensley, SE; Sarosi, GA Jr; Mohr, AM; Loftus, TJ; Upchurch, GR Jr; Sumfest, JM; Efron, PA; Dunleavy, K; Bible, L; Terracina, KP; Al-Mansour, MR; Gravina, N. A narrative review of ergonomic problems, principles, and potential solutions in surgical operations. Surgery 2023, 174(2), 214-221. [CrossRef]

- Bittner, R. Laparoscopic surgery-15 years after clinical introduction. World J Surg. 2006, 30(7), 1190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Salazar, M.J.; Caballero, D.; Sánchez-Margallo, J.A.; Sánchez-Margallo, F.M. Comparative Study of Ergonomics in Conventional and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Surgery. Sensors 2024, 24, 3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemskerk, J; Zandbergen, R; Maessen, JG; Greve, JW; Bouvy, ND. Advantages of advanced laparoscopic systems. Surg Endosc. 2006, 20(5), 730–3. [CrossRef]

- Bittner, JG; Alrefai, S; Vy, M; Mabe, M; Del Prado, PAR; Clingempeel, NL. Comparative Analysis of Open and Robotic Transversus Abdominis Release for Ventral Hernia Repair. Surg Endosc 2017, 32, 727–734. [CrossRef]

- Misiakos, EP; Patapis, P; Zavras, N; Tzanetis, P; Machairas, A. Current Trends in Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair. JSLS 2015, 19(3), e2015.00048. [CrossRef]

- Marrelli, D; Piccioni, SA; Carbone, L; Petrioli, R; Costantini, M; Malagnino, V; Bagnacci, G; Rizzoli, G; Calomino, N; Piagnerelli, R; Mazzei, MA; Roviello, F. Posterior and Para-Aortic (D2plus) Lymphadenectomy after Neoadjuvant/Conversion Therapy for Locally Advanced/Oligometastatic Gastric Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16(7), 1376. [CrossRef]

- Chinzei, K; Hata, N; Jolesz, FA; Kikinis, R. Surgical Assist Robot for the Active Navigation in the Intraoperative MRI: Hardware Design Issues. Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2000) (Cat. No.00CH37113), Takamatsu, Japan; 2000. p. 727-732. [CrossRef]

- Tsekos, NV; Khanicheh, A; Christoforou, E; Mavroidis, C. Magnetic resonance-compatible robotic and mechatronics systems for image-guided interventions and rehabilitation: A review study. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007, 9, 351–387. [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Towards an image-guided restricted drug release in friendly implanted therapeutics. Eur Phys J Appl Phys. 2018, 82, 31401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Image-guided surgical and pharmacotherapeutic routines as part of diligent medical treatment. Appl Sci. 2023, 13, 13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faoro, G; Maglio, S; Pane, S; Iacovacci, V; Menciassi, A. An artificial intelligence-aided robotic platform for ultrasound-guided transcarotid revascularization. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2023, 8, 2349–2356. [CrossRef]

- Su, H; Kwok, KW; Cleary, K; Iordachita, II; Çavuşoğlu, MC; Desai, JP; Fischer, GS. State of the art and future opportunities in MRI-guided robot-assisted surgery and interventions. Proc IEEE Inst Electr Electron Eng. 2022, 110, 968–992. [CrossRef]

- Padhan, J; Tsekos, N; Al-Ansari, A; Abinahed, J; Deng, Z; Navkar, NV. Dynamic Guidance Virtual Fixtures for Guiding Robotic Interventions: Intraoperative MRI-guided Transapical Cardiac Intervention Paradigm. Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE), Taichung, Taiwan, 2022, 265-270. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S; Torrealdea, F; Bandula, S. MR imaging-guided intervention: Evaluation of MR conditional biopsy and ablation needle tip artifacts at 3T using a balanced fast field echo sequence. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2021, 32, 1068–1074. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L ; Pacia, CP ; Gong, Y; Hu, Z; Chien, CY; Yang, L; Gach, HM; Hao, Y; Comron, H; Huang, J; Leuthardt, EC; Chen, H. Characterization of the targeting accuracy of a neuronavigation-guided transcranial FUS system in vitro, in vivo, and in silico. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2023, 70(5), 1528-1538. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Becerra, JA; Borden, MA. Targeted microbubbles for drug, gene, and cell delivery in therapy and immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15(6), 1625. [CrossRef]

- Delaney LJ, Isguven S, Eisenbrey JR, Hickok, NJ; Forsberg, F. Making waves: How ultrasound-targeted drug delivery is changing pharmaceutical approaches. Mater Adv. 2022, 3, 3023–3040. [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Augmented therapeutic tutoring in diligent image-assisted robotic interventions. AIMS Med Sci. 2024, 11(2), 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Planning and performing image-assisted robotic interventions using personalized, minimally invasive, safe, and precise therapeutics. INNOSC Theranostics and Pharmacological Sciences 2024, 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, N; Pedone Anchora, L; Teodorico, E; Certelli, C; Galati, G; Carbone, V; Gallotta, V; Naldini, A; Costantini, B; Querleu, D; Fanfani, F; Fagotti, A; Scambia, G; Ferrandina, G. The role of diagnostic laparoscopy in locally advanced cervical cancer staging. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2024, 50(12), 108645. [CrossRef]

- Li, SY; Ye-Wang; Cheng-Xin; Ji, LQ; Li, SH; Jiang, WD; Zhang CM; Zhang W; Lou Z. Laparoscopic surgery is associated with increased risk of postoperative peritoneal metastases in T4 colon cancer: a propensity score analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2025, 40(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, K; Glenisson, M; Loiselet, K; Fiorenza, V; Cornet, M; Capito, C; Vinit, N; Pire, A; Sarnacki, S; Blanc, T. Robot-assisted laparoscopic adrenalectomy: Extended application in children. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2024, 50(12), 108627. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, RH; Menciassi, A; Fichtinger, G; Fiorini, P; Dario, P. Medical Robotics and Computer-Integrated Surgery. Springer Handbook of Robotics, B. Siciliano and O. Khatib, Eds., in Springer Handbooks, Cham: Springer International Publishing 2016, 1657–1684. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q; Shi, Y; Xiao, X; Li, X; Mo, H. Review of Human–Robot Collaboration in Robotic Surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 2400319. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T; Wang, J; Wong, S; Razjigaev, A; Beier, S; Peng, S; Do, TN; Song, S; Chu, D; Wang, CH; Lovell, NH; Wu, L. A Review on the Form and Complexity of Human–Robot Interaction in the Evolution of Autonomous Surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2400197. [CrossRef]

- Schreiter, J.; Schott, D.; Schwenderling, L.; Hansen, C.; Heinrich, F.; Joeres, F. AR-Supported Supervision of Conditional Autonomous Robots: Considerations for Pedicle Screw Placement in the Future. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, T ; Song, SE. Robotic Surgery Techniques to Improve Traditional Laparoscopy. JSLS 2022, 26(2), e2022.00002. [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Moreno, Y; Echevarria, S; Vidal-Valderrama, C; Pianetti, L; Cordova-Guilarte, J; Navarro-Gonzalez, J; Acevedo-Rodríguez, J; Dorado-Avila, G; Osorio-Romero, L; Chavez-Campos, C; Acero-Alvarracín, K. Robotic Surgery: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature and Current Trends. Cureus 2023, 15(7), e42370. [CrossRef]

- Lima, VL; de Almeida, RC; Neto, TR; Rosa, AAM. Chapter 72 - Robotic ophthalmologic surgery, Editor(s): Zequi, SC; Ren, H. Handbook of Robotic Surgery, Academic Press 2025, 701-704. [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Moreno, Y; Rodriguez, M; Losada-Muñoz, P; Redden, S; Lopez-Lezama, S; Vidal-Gallardo, A; Machado-Paled, D; Cordova Guilarte, J; Teran-Quintero, S. Cureus 2024, 16(1), e52243. [CrossRef]

- Han, J; Davids, J; Ashrafian, H; Darzi, A; Elson, DS; Sodergren, M. A systematic review of robotic surgery: From supervised paradigms to fully autonomous robotic approaches. Int J Med Robot 2022, 18(2), e2358. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A; Baker, TS; Bederson, JB; Rapoport, BI. Levels of autonomy in FDA-cleared surgical robots: a systematic review. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7(1), 103. [CrossRef]

- Haidegger, T. Autonomy for surgical robots: Concepts and paradigms. IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics 2019, 1(2), 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011, 128(1), 305-310. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B ; Liu, L ; Meng, D ; Kue, CS. Medical imaging technology: Principles and systems. INNOSC Theranostics Pharmacol Sci. 2024, 7(3), 3360. [CrossRef]

- Kraus, MS, Coblentz, AC ; Deshpande, VS ; Peeters, JM; Itriago-Leon, PM; Chavhan, GB. State-of-the-art magnetic resonance imaging sequences for pediatric body imaging. Pediatr Radiol. 2023, 53, 1285–1299. [CrossRef]

- Sennimalai, K; Selvaraj, M; Kharbanda, OP; Kandasamy, D; Mohaideen, K. MRI-based cephalometrics: A scoping review of current insights and future perspectives. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2023, 52, 20230024. [CrossRef]

- Chianca, V.; Vincenzo, B.; Cuocolo, R.; Zappia, M.; Guarino, S.; Di Pietto, F.; Del Grande, F. MRI Quantitative Evaluation of Muscle Fatty Infiltration. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato Y, Takeuchi T, Fuju A, Yusuke Sato and Tomokazu Takeuchi and Atsuya Fuju and Masahiko Takahashi, M; Hashimoto, M; Okawa, R; Hayashi, R. MRI safety for leave-on powdered hair thickeners under 1.5-T and 3.0-T MRI: Measurement of deflection force, MRI artifact, and evaluation of preexamination screening. Phys Eng Sci Med. 2023, 46, 915–924. [CrossRef]

- Akdogan, G; Istanbullu, O. Analysing the effects of metallic biomaterial design and imaging sequences on MRI interpretation challenges due to image artefacts. Phys Eng Sci Med. 2022, 45, 1163–1174. [CrossRef]

- Germann, C; Nanz, D; Sutter, R. Magnetic resonance imaging around metal at 1.5 Tesla: Techniques from basic to advanced and clinical impact. Investig Radiol. 2021, 56, 734–748. [CrossRef]

- Germann, C; Falkowski, AL; von Deuster, C; Nanz, D; Sutter, R. Basic and advanced metal-artifact reduction techniques at ultra- high field 7-T magnetic resonance imaging-phantom study investigating feasibility and efficacy. Investig Radiol. 2022, 57, 387–398. [CrossRef]

- Inaoka, T; Kitamura, N; Sugeta, M; Nakatsuka, T; Ishikawa, R; Kasuya, S; Sugiura, Y; Nakajima, A; Nakagawa, K; Terada, H. Diagnostic value of advanced metal artifact reduction magnetic resonance imaging for periprosthetic joint infection. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2022, 46, 455–463. [CrossRef]

- Haskell, MW; Nielsen, JF; Noll, DC. Off-resonance artifact correction for MRI: A review. NMR Biomed. 2023, 36, e4867. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X; Zhang, Y; Du, H; Yu, Y. Experimental study of double cable-conduit driving device for MRI compatible biopsy robots. J Mech Med Biol. 2021, 21, 2140014. [CrossRef]

- Li, X; Young, AS; Raman, SS; Lu, DS; Lee, YH; Tsao, TC; Wu, HH. Automatic needle tracking using Mask R-CNN for MRI-guided percutaneous interventions. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2020, 15, 1673–1684. [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, MC; Moreira, P; Lezcano, D; Foley, L; Tuncali, K; Tempany, C; Kim, JS; Hata, N; Iordachita, I; Tokuda, J. In Vivo Feasibility Study: Evaluating Autonomous Data-Driven Robotic Needle Trajectory Correction in MRI-Guided Transperineal Procedures. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9(10), 8975–8982. In Vivo Feasibility Study. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D; Li, G; Patel, N; Yan, J; Monfaredi, R; Cleary, K; Iordachita, I. Remotely Actuated Needle Driving Device for MRI-Guided Percutaneous Interventions: Force and Accuracy Evaluation. Proceedings of the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mohith, S; Upadhya, AR; Navin, KP; Kulkarni, SM; Rao, M. Recent trends in piezoelectric actuators for precision motion and their applications: A review. Smart Mater Struct. 2020, 30, 013002. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X; Yang, J; Wu, J; Xin, X; Li, Z; Yuan, X; Shen, X; Dong, S. Piezoelectric actuators and motors: Materials, designs, and applications. Adv. Mater Technol. 2020, 5, 1900716. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G; Li, H; Lu, X; Wen, J; Cheng, T. Piezoelectric stick-slip actuators with flexure hinge mechanisms: A review. J Intell Mater Syst Struct. 2022, 33, 1879–1901. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J; Gao, X; Jin, H; Ren, K; Guo, J; Qiao, L; Qiu, C; Chen, W; He, Y; Dong, S; Xu, Z; Li, F. Miniaturized electromechanical devices with multi-vibration modes achieved by orderly stacked structure with piezoelectric strain units. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 6567. [CrossRef]

- Fu, DK; Fan, PQ; Yuan, T; Wang, YS. A novel hybrid mode linear ultrasonic motor with double driving feet. Rev Sci Instrum. 2022, 93, 025003. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z; Guo, Z; Han, H; Su, Z; Sun, H. Design and characteristic analysis of multi-degree-of-freedom ultrasonic motor based on spherical stator. Rev Sci Instrum. 2022, 93, 025004. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S; Zhou, S; Zhang, X; Xu, P; Zhang, Z; Ren, L. Bionic stepping motors driven by piezoelectric materials. J Bionic Eng. 2023, 20, 858–872. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C; Bernard, Y; Razek, A. Design and manufacturing of a piezoelectric traveling-wave pumping device. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2013, 60, 1949–1956. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S; Liu, Y; Deng, J; Gao, X; Li, J; Wang, W; Xun, M; Ma, X; Chang, Q; Liu, J; Chen, W; Zhao, J. Piezo robotic hand for motion manipulation from micro to macro. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 500. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z; Li, X; Tang, J; Huang, H; Zhao, H; Cheng, Y; Liu, S; Li, C; Xiong, M. A bionic stick-slip piezo-driven positioning platform designed by imitating the structure and movement of the crab. J Bionic Eng. 2023, 20, 2590–2600. [CrossRef]

- Tao, F; Sui, F; Liu, A; Qi, Q; Zhang, M; Song, B; Guo, Z; Lu, SCY; Nee, AYC. Digital twin-driven product design framework. Int J Prod Res. 2019, 57, 3935–3953. [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M; Vickers, J. Digital twin: Mitigating unpredictable, undesirable emergent behavior in complex systems. In: Trans-disciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer 2017, 85-113. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A; Fan, Z; Day, C; Barlow, C. Digital twin: Enabling technologies, challenges and open research. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108952–108971. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T; He, X; Li, Z. Digital twin in healthcare: Recent updates and challenges. Digit Health 2023, 9, 20552076221149651. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T; He, X; Song, X; Shu, L; Li, Z. The digital twin in medicine: A key to the future of healthcare? Front Med. 2022, 9, 907066. [CrossRef]

- De Benedictis, A; Mazzocca, N; Somma, A, Strigaroet, C. Digital twins in healthcare: An architectural proposal and its application in a social distancing case study. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2022, 27, 5143–5154. [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A; Javaid, M; Singh, RP; Suman, R. Exploring the revolution in healthcare systems through the applications of digital twin technology. Biomed Technol. 2023, 4, 28–38. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N; Al-Jaroodi, J; Jawhar, I; Kesserwan, N. Leveraging digital twins for healthcare systems engineering. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 69841–69853. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaroodi, J; Mohamed, N. Enhancing the Efficiency of Healthcare Facilities Management with Digital Twins. 2024 International Conference on Smart Applications, Communications and Networking (SmartNets), Harrisonburg, VA, USA, 2024, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A; Croatti, A; Montagna, S. Pervasive and connected digital twins-a vision for digital health. IEEE Internet Comput. 2022, 26, 26–32. [CrossRef]

-

Okegbile, SD; Cai, J. Edge-Assisted Human-to-Virtual Twin Connectivity Scheme for Human Digital Twin Frameworks. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 95th Vehicular Technology Conference: (VTC2022-Spring), Helsinki, Finland, 2022; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Das, C; Mumu, AA; Ali, MF; Sarker, SK; Mmuyeen, S; Das, SK; Das, P; Hasan, M; Tasneem, Z; Islam, M; Islam, R; Badal, FR; Ahamed, H; Abhi, SH. Toward IoRT collaborative digital twin technology enabled future surgical sector: Technical innovations, opportunities and challenges. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 129079–129104. [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, A; Marfoglia, A; Nardini, F; Mellone, S. CONNECTED: Leveraging digital twins and personal knowledge graphs in healthcare digitalization. Front Digit Health 2023, 5, 1322428. [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, N; Ulapane, N; Sloane, EB; Gehlot, V. Digital Twins for More Precise and Personalized Treatment. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2024, 310, 229–233. [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Monitoring complexity in clean energy systems applications. Clean Energy Sustain. 2024, 2, 10007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, JC. VIII. A dynamical theory of the electromagnetic field. Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society 1865, 155, 459–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.S.; Chadebec, O.; Kuo-Peng, P.; Dular, P.; Meunier, G. A Coupling between the Facet Finite Element and Reluctance Network Methods in 3-D. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2017, 53 (10). [CrossRef]

- Henrotte, F; Geuzaine, C. Electromagnetic forces and their finite element computation. Int J Numer Model. 2024, 37(5), e3290. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, O.J.; Bastos, J.P.A.; Sadowski, N.; Razek, A.; Santandrea, L.; Bouillault, F.; Rapetti, F. Comparison between nonconforming movement methods. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2006, 42, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z; Razek, A. Comparison of some 3D eddy current formulations in dual systems. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2000, 36(4), 751–755. [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, IT; Martin, F; Rasilo, P; Billah, MM; Belahcen, A. A new methodology for incorporating the cutting deterioration of electrical sheets into electromagnetic finite-element simulation. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2024, 593, 171843. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, IPC; de Miranda, RA; Sadowski, N; Batistela, NJ; Bernard, L; Bastos, JP. Modeling of Electrical Machines Hysteresis Losses under Mechanical Stresses. Journal of Microwaves, Optoelectronics and Electromagnetic Applications 2024, 23(3), e2024283838. [CrossRef]

- Urdaneta-Calzadilla, A.; Chadebec, O.; Galopin, N.; Niyonzima, I.; Meunier, G.; Bannwarth, B. Modeling of Magnetoelectric Effects in Composite Structures by FEM–BEM Coupling. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2023, 59(5), 1-4, 7000604. [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann, A; Lessmann, M; Finocchiaro, T; Schmitz-Rode, T; and Hameyer, K. Numerical Computation Can Save Life: FEM Simulations for the Development of Artificial Hearts. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2011, 47(5), 1166-1169. [CrossRef]

- Gu, B; Li, H; Li, B. An internal ballistic model of electromagnetic railgun based on PFN coupled with multi-physical field and experimental validation. Defence Techno. 2024, 32, 254–261. [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Coupled Models in Electromagnetic and Energy Conversion Systems from Smart Theories Paradigm to That of Complex Events: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudela, J; Matousek, R. Recent advances and applications of surrogate models for finite element method computations: A review. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 13709–13733. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M; Zhao, X; Dhimish, M; Qiu, W; Niu, S. A Review of Data-driven Surrogate Models for Design Optimization of Electric Motors. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2024, 10(4), 8413-84311. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.; Lau, R.W.; Gabriel, C. The dielectric properties of biological tissues: II. Measurements in the frequency range 10 Hz to 20 GHz. Phys. Med. Biol. 1996, 41, 2251–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchanski, A; Steiner, T. ; De Gersem, H.; Clemens, M.; Weiland, T. Local grid refinement for low-frequency current computations in 3-D human anatomy models. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2006, 42, 1371–1374. [CrossRef]

- Hasgall, PA; Di Gennaro, F; Baumgartner, C; Neufeld, E; Lloyd, B; Gosselin, MC; Payne, D; Klingenböck, A; Kuster, N. iT'S Database for thermal and electromagnetic parameters of biological tissues 2022. Version 4.1. [CrossRef]

- Makarov, SN; Noetscher, GM; Yanamadala, J; Piazza, MW; Louie, S; Prokop, A; Nazarian, A; Nummenmaa, A. Virtual Human Models for Electromagnetic Studies and Their Applications. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 10, 95–121. [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.R.; Zhadobov, M.; Chahat, N.; Sauleau, R. Electromagnetic dosimetry for adult and child models within a car: Multi-exposure scenarios. Int. J. Microw. Wireless Technol. 2011, 3, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjonaj, E.; Bartsch, M.; Clemens, M.; Schupp, S.; Weiland, T. High-resolution human anatomy models for advanced electromagnetic field computations. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2002, 38, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Biological and Medical Disturbances Due to Exposure to Fields Emitted by Electromagnetic Energy Devices—A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, VA; Morris, JM. Establishing a point-of-care virtual planning and 3D printing program. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2022, 36, 133–148. [CrossRef]

- Elkefi, S; Asan, O. Digital twins for managing health care systems: rapid literature review. J Med Internet Res 2022, 24, e37641. [CrossRef]

- Cellina, M.; Cè, M.; Alì, M.; Irmici, G.; Ibba, S.; Caloro, E.; Fazzini, D.; Oliva, G.; Papa, S. Digital Twins: The New Frontier for Personalized Medicine? Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangasmaa, O; Laakso, I; Schmid, G. Estimating Human Fat and Muscle Conductivity From 100 Hz to 1 MHz Using Measurements and Modelling. Bioelectromagnetics 2025, 46, e22541. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, JD. Biological soft tissues. In: Sharpe W, editor. Springer Handbook of Experimental Solid Mechanics. Springer Handbooks. Boston, MA., USA: Springer, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Kallin, S. Deformation of Human Soft Tissues: Experimental and numerical aspects. Licentiate Thesis, Jönköping University, School of Health and Welfare, HHJ, Department of Rehabilitation; 2019. Available from: https://hj.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1344790/FULLTEXT01.pdf [Last accessed on 2025 Jan. 17].

- Al-Dirini, RMA; Reed, MP; Hu, JW; Thewlis, D. Development and validation of a high anatomical fidelity FE model for the buttock and thigh of a seated individual. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016, 44(9), 2805–2816. [CrossRef]

- Fung, YC. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. 2nd ed. New York, Berlin: Springer-Vlg, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Henninger, HB; Reese, SP; Anderson, AE; Weiss, JA. Validation of computational models in biomechanics. Proc Inst Mechan Eng H. 2010, 224(7), 801–881. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. Human digital twin, the development and impact on design. J Comput Inf Sci Eng. 2023, 23, 060819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burattini, S; Montagna, S; Croatti, A; Gentili, N; Ricci, A; Leonardi, L; Pandolfini, S; Tosi, S. An Ecosystem of Digital Twins for Operating Room Management. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 36th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), L’Aquila, Italy, 2023. 770-775. [CrossRef]

- Hagmann, K; Hellings-Kuß, A; Klodmann, J; Richter, R; Stulp, F; Leidner, D. A digital twin approach for contextual assistance for surgeons during surgical robotics training. Front Robot AI 2021, 8, 735566. [CrossRef]

- Katsoulakis, E; Wang, Q; Wu, H; Shahriyari, L; Fletcher, R; Liu, J; Achenie, L; Liu, H; Jackson, P; Xiao, Y; Syeda-Mahmood, T; Tuli, R; Deng, J. Digital twins for health: a scoping review. NPJ Digit Med. 2024, 7, 77. [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, D; Boldrini, L; Dhont, J; Fiorino, C; Green, O; Güngör, G; Jornet, N; Klüter, S; Landry, G; Mattiucci, GC; Placidi, L; Reynaert, N; Ruggieri, R; Tanadini-Lang, S; Thorwarth, D; Yadav, P; Yang, Y; Valentini, V; Verellen, D; Indovina, L. Artificial intelligence in magnetic resonance guided radiotherapy: Medical and physical considerations on state of art and future perspectives. Phys Med. 2021, 85, 175–191. [CrossRef]

- Seetohul, J; Shafiee, M; Sirlantzis, K. Augmented reality (AR) for surgical robotic and autonomous systems: State of the art, challenges, and solutions. Sensors (Basel) 2023, 23, 6202. [CrossRef]

- Avrumova, F; Lebl, DR. Augmented reality for minimally invasive spinal surgery. Front Surg. 2023, 9, 1086988. [CrossRef]

- Long, Y; Cao, J; Deguet, A; Taylor, RH; Dou, Q. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Augmented Reality in Robotic Surgery: An Initial dVRK Study Using a Surgical Education Scenario. In: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Medical Robotics (ISMR), Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Rota, A.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Q.; Iovene, E.; Ferrigno, G.; De Momi, E. Recent Advancements in Augmented Reality for Robotic Applications: A Survey. Actuators 2023, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L; Wu, JY; DiMaio, SP; Navab, N; Kazanzides, P. A review of augmented reality in robotic-assisted surgery. IEEE Trans Med Robot Bionics. 2020, 2, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kukushkin, K; Ryabov, Y; Borovkov, A. Digital twins: a systematic literature review based on data analysis and topic modeling. Data 2022, 7, 173. [CrossRef]

- Armeni, P; Polat, I; De Rossi, LM; Diaferia, L; Meregalli, S; Gatti, A. Digital twins in healthcare: is it the beginning of a new era of evidence-based medicine? A critical review. J Pers Med 2022, 12, 1255. [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, S; Difalco, P; Caradonna, L; Tetè, S. Traditional endodontic surgery versus modern technique: a 5-year controlled clinical trial. J Craniofac Surg. 2014, 25(3), 804-807. [CrossRef]

- You, C; Lu, H; Zhao, J; Qin, B; Liu, W. The Comparison Between Traditional Versus 3D Printing Combined With Computer Navigation Technique in the Management of Orbital Blowout Fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2025, 36(1), 201–205. [CrossRef]

- Bates, HW. Contributions to an insect fauna of the amazon valley. Lepidoptera: Heliconidae. Trans Linnean Soc London. 1862, 23(3), 495-566. [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Matching of an observed event and its virtual model in relation to smart theories, coupled models and supervision of complex procedures-A review. Comptes Rendus Phys. 2024, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razek, A. Strategies for managing models regarding environmental confidence and complexity involved in intelligent control of energy systems - A review. Adv Environ Energies 2023, 2(1), aee020104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebensztajn, L; Marretto, CAR; Caldora Costa, M; Coulomb, JL. Kriging: A useful tool for electromagnetic device optimization. IEEE Trans Magn. 2004, 40(2), 1196-1199. [CrossRef]

- Gaignaire, R; Scorretti, R; Sabariego, RV; Geuzaine, C. Stochastic uncertainty quantification of eddy currents in the human body by polynomial chaos decomposition. IEEE Trans Magn. 2012, 48(2), 451–454. [CrossRef]

- Den Boer, J.A.; Bourland, J.D.; Nyenhuis, J.A.; Ham, C.L.; Engels, J.M.; Hebrank, F.X.; Frese, G.; Schaefer, D.J. Comparison of the threshold for peripheral nerve stimulation during gradient switching in whole body MR systems. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2002, 15, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, M; Guerin, B; Klein, V; Wald, LL. Optimization of MRI Gradient Coils With Explicit Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Constraints. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2021, 40(1), 129–142. [CrossRef]

- Thylur, DS; Jacobs, RE; Go, JL; Toga, AW; Niparko, JK. Ultra-High-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Human Inner Ear at 11.7 Tesla. Otology & Neurotology 2017, 38(1), 133-138. [CrossRef]

- Crozier, S; Liu, F. Numerical evaluation of the fields induced by body motion in or near high-field MRI scanners. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2005, 87(2–3), 267-278. [CrossRef]

- van Osch, MJP; Webb, AG. Safety of Ultra-High Field MRI: What are the Specific Risks?. Curr Radiol Rep 2014, 2, 61. [CrossRef]

- Bouisset, N; Laakso, I. Induced electric fields in MRI settings and electric vestibular stimulations: same vestibular effects? Exp Brain Res 2024, 242, 2493–2507. [CrossRef]

- Mian, OS; Li, Y; Antunes, A; Glover, PM; Day, BL On the Vertigo Due to Static Magnetic Fields. PLoS ONE 2013, 8(10): e78748. [CrossRef]

- Boegle, R; Dieterich, M; Kirsch, V. Comment On: Modulatory Effects of Magnetic Vestibular Stimulation on Resting-State Networks Can be Explained by Subject-Specific Orientation of Inner Ear Anatomy in the MR Static Magnetic Field. J Exp Neurol. 2020, 1(3), 109-114. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).