Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

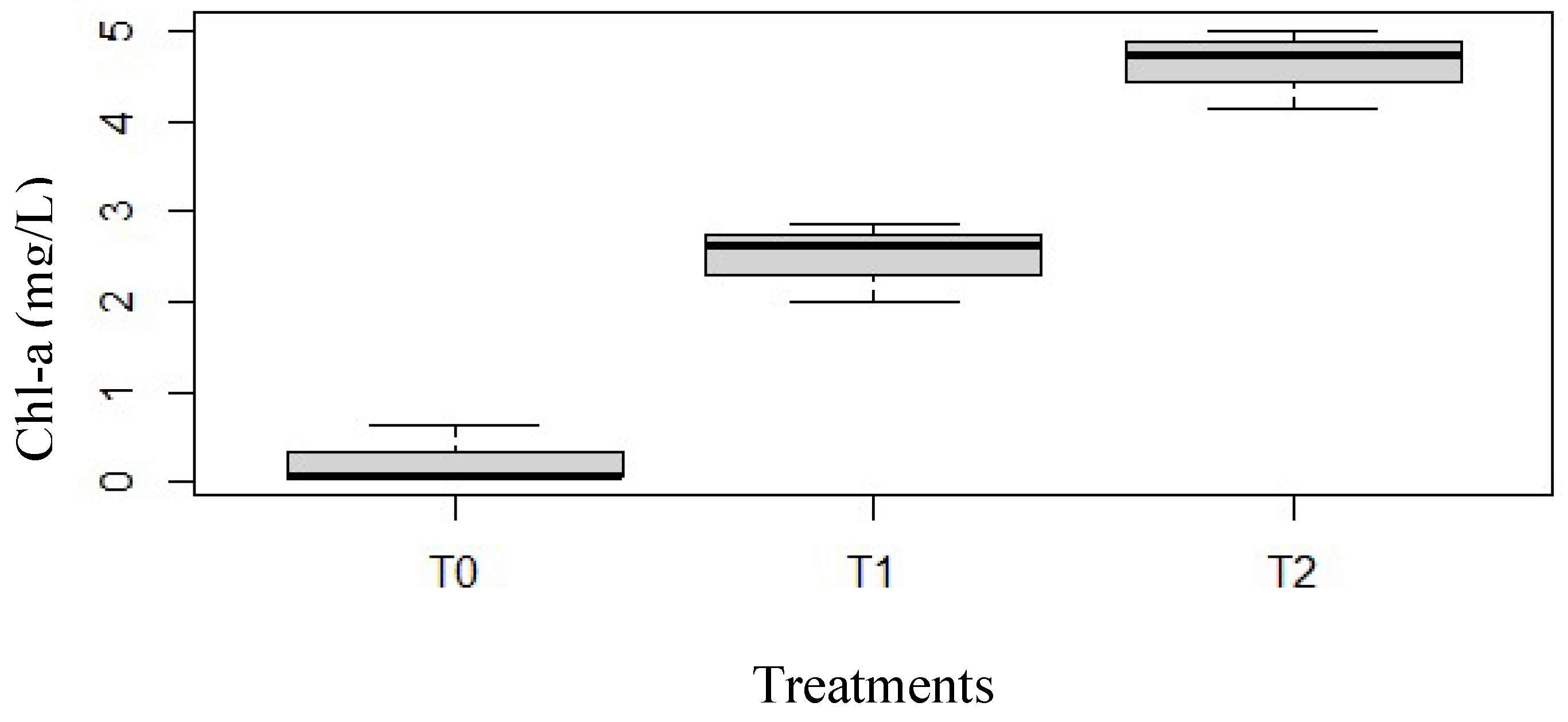

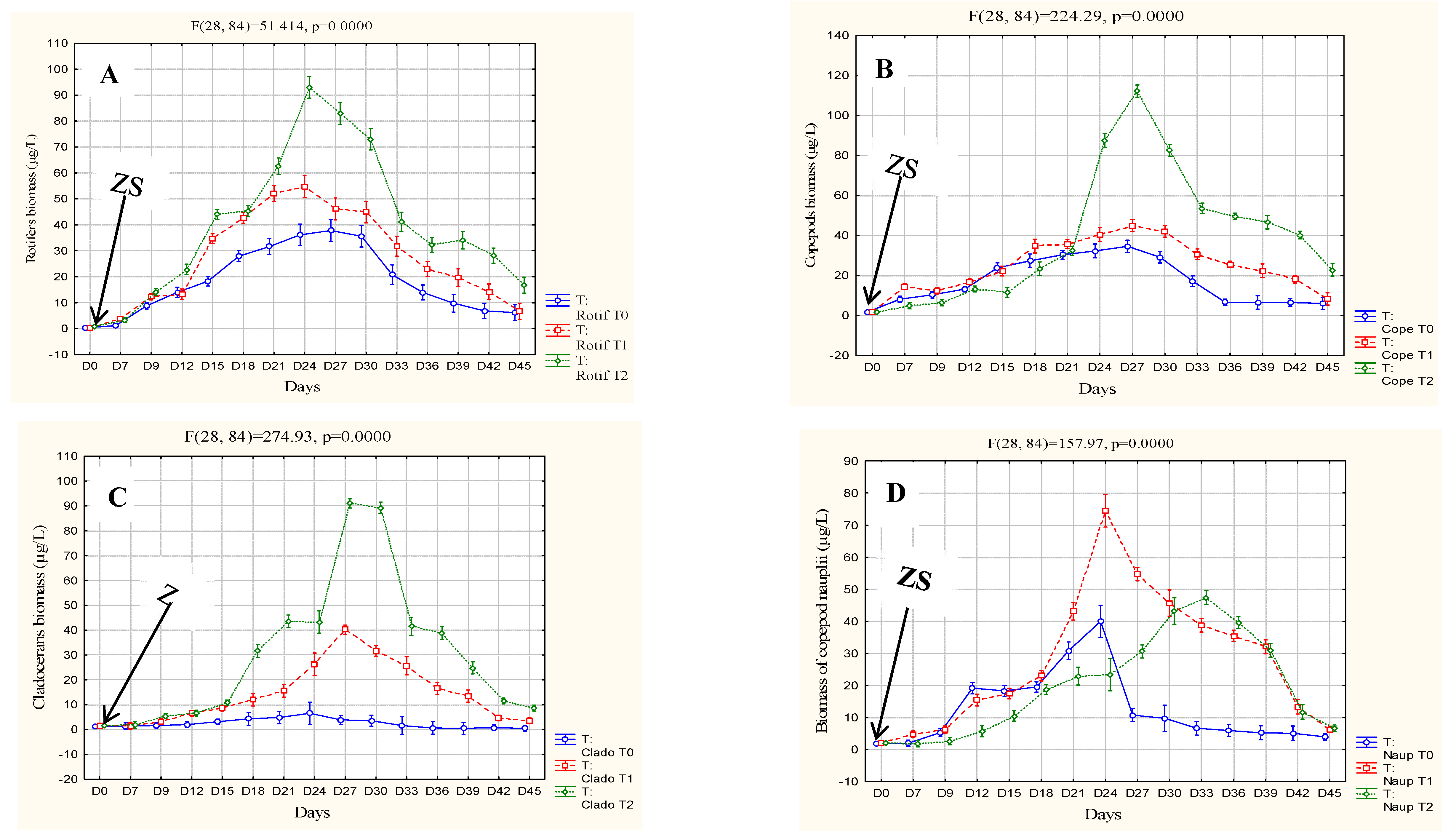

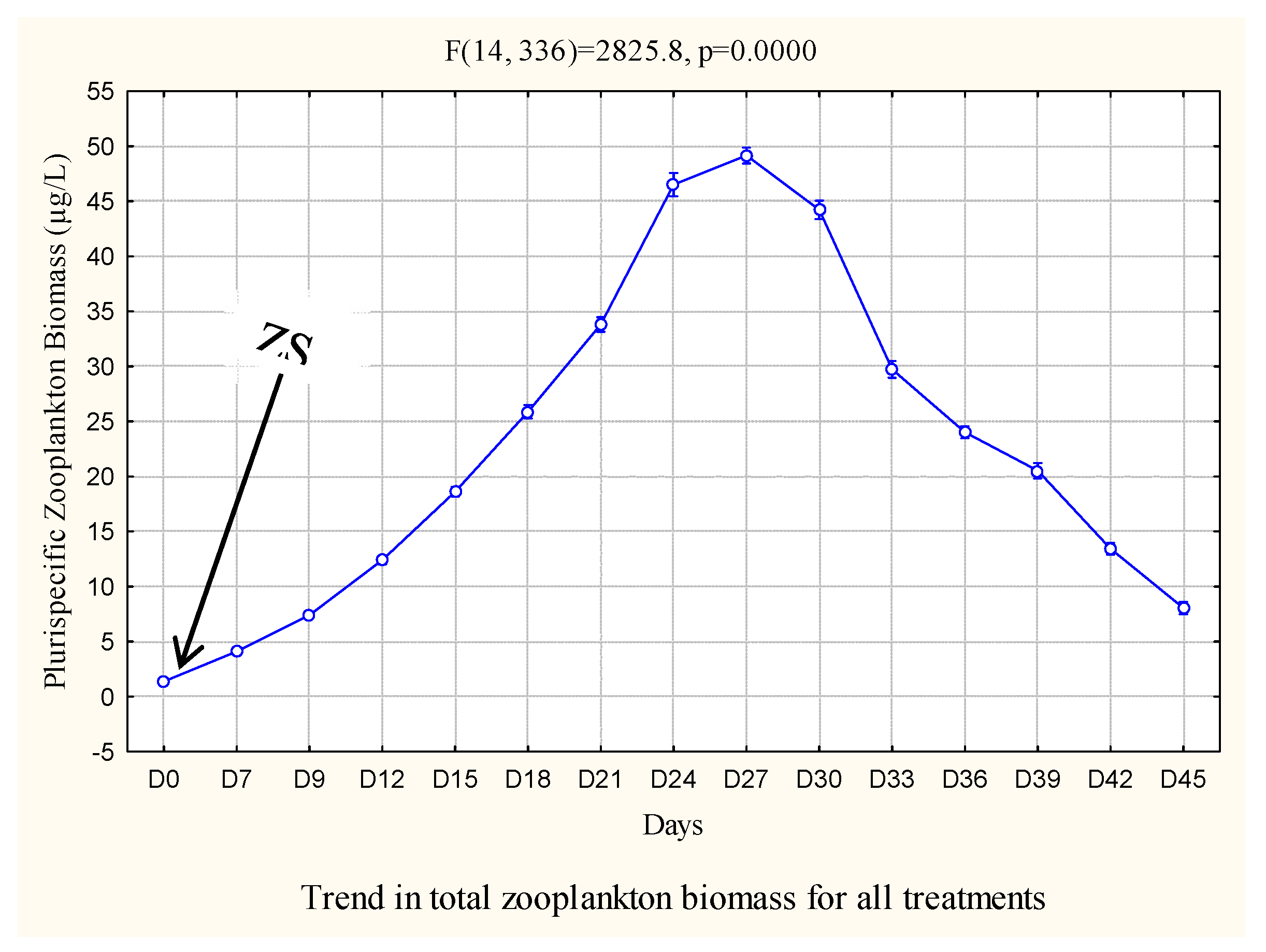

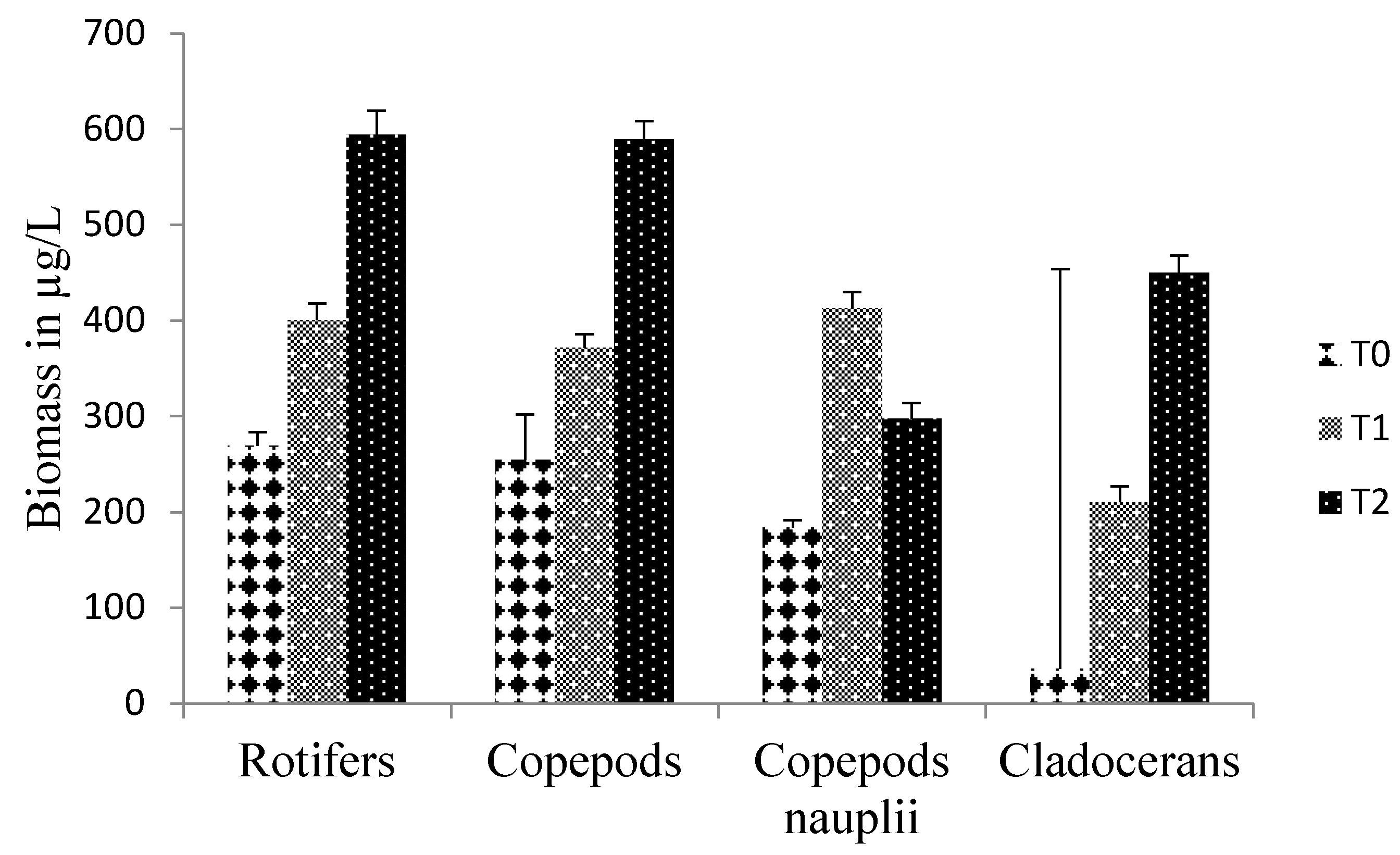

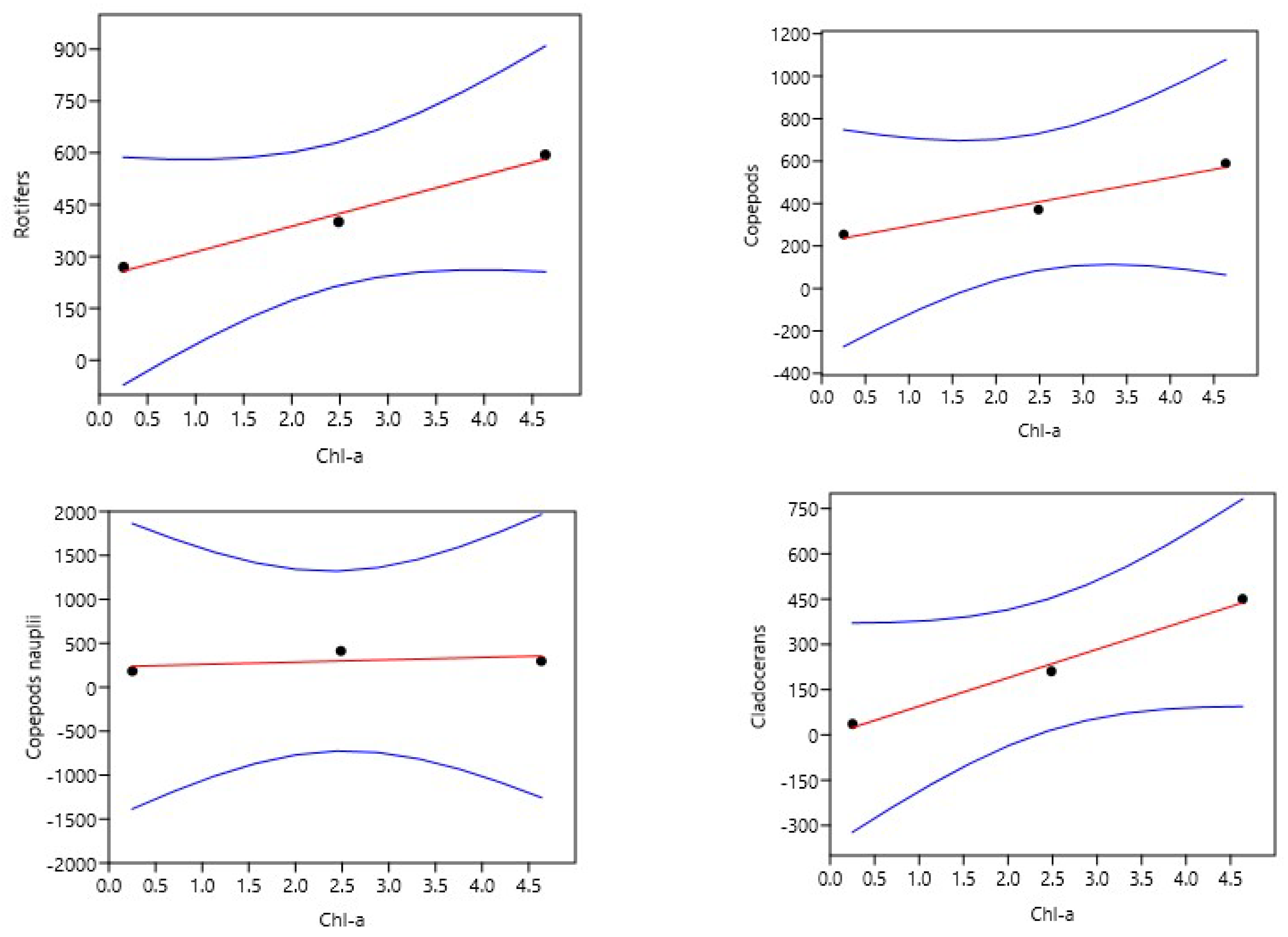

To identify an ideal dose of pig manure from piggeries in the Forest Guinea for the production of zooplankton in rural fish farms for larval breeding, three doses including a control of 0 (T0), 300 (T1) and 600 (T2) g/m3 were tested for forty-five days. The experimental device of three buckets with a capacity sixty liters per treatment was each filled with 40 liters of demineralized water and immediately fertilized with the different doses. Three days after fertilization, phytoplankton was seeded followed by zooplankton seventy-two hours later. The initial seeding density was 35±7.62 ind/L or (23±1.13 ind/L of copepod nauplii or 1.84±0.13 µg/L (Thermocyclops sp.), 4±0.1 ind/L or 1.88±0.1 µg/L copepod adults (Thermocyclops sp.), 1±0.007 ind/L or 2.7±0.7 µg/L cladocerans (Moina sp. and Daphnia sp.) and 3±1.48 ind/L or 0.21 ± 1.48 of rotifers (Brachionus sp and Asplanchna sp.). The results show that doses of 300 (T1) and 600 (T2) g/m3 of pig slurry gave good primary production, the highest of which was obtained with T2 (4.63±2.48 mg/L) with a strong correlation with zooplankton biomass (r2 between 0.96 and 0.98). Biomasses recorded in T2 were 594.35±24.93 µg/L rotifers, 589.73±18.98 µg/L copepods and 449.95±18.15 µg/L cladocerans. This dose could be considered ideal for rural fish farmers in forested Guinea.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and methods

2.1. Experimental design

2.2. Physico-chemical and trophic parameters

2.3. Phytoplankton and Zooplankton seeding process

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

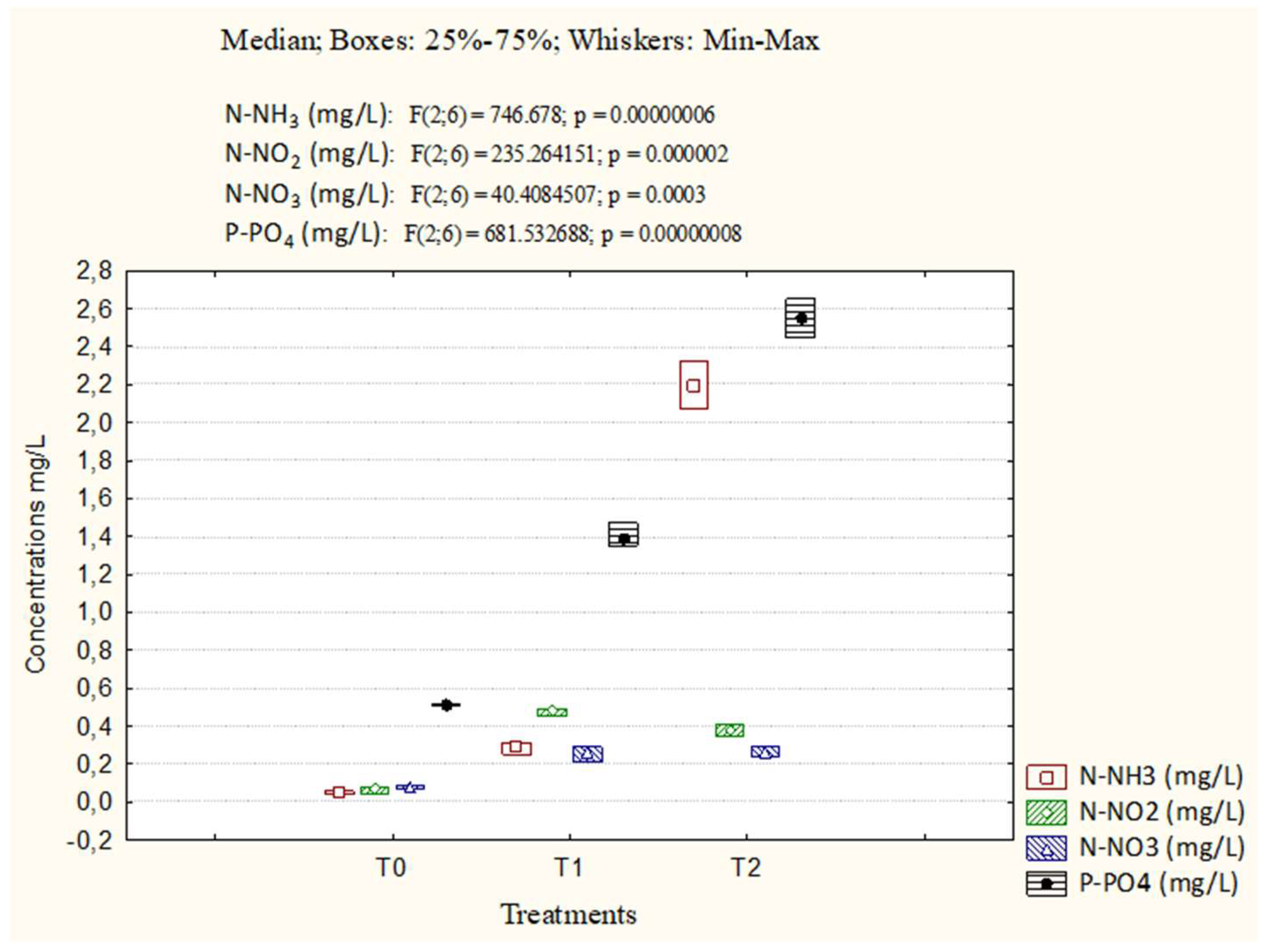

3.1. Abiotic parameters

3.2. Biotic parameter

3.3. Multispecies zooplankton biomass

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO (Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture) Rome, 2021, P44. www.fao.org/pwb.

- Lazard, J. La diversité des piscicultures mondiales illustrée par les cas de la Chine et du Nigeria. Cah. Agric. 2014, 23, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiogbe, E.D.; Kestemont, P. ; Micha, J-C. Performances zootechniques comparées de rotifères d'eau douce Brachionus calyciflorus et de nauplies d'Artemia chez les larves de la perche fluviatile perca fluviatilis. Tropic. 2003, 21, 31-35. http://www.tropicultura.org/text/v21n1.pdf#page=33.

- Arimoro, F. First feeding in the African Catfish Clarias anguillaris fry in tanks with the freshwater rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus cultured in a continuous feed back mechanism in comparison with a mixed zooplankton diet. J. of Fish. and Aquat. Sci. 2007, 2, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaari, A.; Iehata, S.; Kim H-J.; Rasdi, N.W. Recent advancement of zooplankton enriched with nutrients and probiotic isolates from aquaculture systems: a review, J. of Appli. Anim. Res. 2024, 52-1. [CrossRef]

- Adande, R.; Liady, M.N.D.; Tossavi, C.E.; Fiogbe, E.D. The effect of zooplankton produced using rabbit manure and artemia on the survival and growth of larvae of Clarias gariepinus, Heterobranchus longifilis and heteroclarias. Int. of Fish. and Aquat. Sci. 2017, 5, 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Adande, R.; Djidohokpin, G.; Djissou, S.M.A.; Bilivogui, P. Bromatological value of Chironomidae produced from organic fertilizers and their effects on the growth of Clarias gariepinus fry in the Guinean forest region. Blue Biotechnol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- CILSS. Permanent Interstate Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel. 2009, P15. https://www.anasa.gov.gn/2021/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Situation-Alimentaire-et-Nutritionnelle-Guinees-2019.pdf.

- APDRA (Association de Pisciculture et Développement rural en Afrique). Pisciculture Paysanne, rapport d’activité, l’innovation piscicole pour satisfaire les besoins alimentaires. 2017, P.23. apdra.org http://apdra.org › IMG › file · Fichier PDF.

- Knuckey, R.M.; Brown, MR.; Robert, R.; Frampton, D.M. F. ; “Production of Microalgal Concentrates by Flocculation and Their Assessment as Aquaculture Feeds,” Aquacultural Enginer. 2006, 300-313.

- Conceição, L.E.C.; Yúfera, M.; Makridis, P.; Morais, S.; Dinis, M.T. “Live Feeds for Early Stages of Fish Rearing,” Aquaculture Research. 2010. 41, no. 5: 613-640.

- Sontakke., R.; Chaturvedi, C.S.; Saharan, N.; Tiwari, V.K.; Haridas, H.; Rani, A.B. Sontakke. R.; Chaturvedi, C.S.; Saharan, N.; Tiwari, V.K.; Haridas, H.; Rani, A.B. Growth response, digestive enzyme activity and stress enzyme status in early stages of an endangered fish, Notopterus chitala (Hamilton, 1822) fed with live feed and formulated diet. Aquaculture. 2019, 182-190. [CrossRef]

- Kandathil Rad hakrishnan, D.; AkbarAli, I.; Schmidt, B.V.; John, E.M.; Sivanpillai, S.; Thazhakot Vasunambesan, S. Improvement of nutritional quality of live feed for aquaculture: an overview. Aquac Res. 2020, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agadjihouèdé, H.; Bonou, A.C.; Montchowui, E.; Laleye, P. Recherche de la dose optimale de fiente de volaille pour la production spécifique de zooplancton à des fins piscicoles. Cah. Agric. 2011, 247–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adandé, R.; Liady, M.N.D.; Bokossa, H.K.J.; Djidohokpin, G.; Zouhir, F.; Mensah, G. A.; Fiogbe, E.D. Utilisation rationnelle de fertilisants organiques pour la production de macroinvertébrés benthiquesd’eau douce en pisciculture. Base. 2018, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adande, R. ; Liady, Liady, M.N.D.; Sossoukpe, E.; Fiogbe, E.D. Effect of Different Doses of Rabbit Manure on the Abundance, Growth Rate and Production of Zooplankton in Plurispecific System for Fish Larvae Feeding, Int. J. of Aquacult. 2017, 7, 112-121. http://ija.biopublisher.ca.

- UNESCO. Determination of phytosynthetic pigment in seawater, Repport SCOR UNESCO, Pers 17. Monographs on oceanographic methodology, 1966. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0007/000716/071612eo.pdf.

- Shoko, A.; Getabu, A.; Mwayuli, G.; Mgaya, Y. Growth performance yields and economic benefits of O. niloticus and Kales (B oleracea) cultured under vegetable-fish culture integration. Tanz. J. of Sc. 2011, 37-48. [CrossRef]

- Gebru, T.T.; Balkew, W.K. Plankton Composition and Abundance in Semi Intensive Aquaculture Pond and their Preference by Nile tilapia. Aquacult. Stud. 2023, 23, AQUAST1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodier, J. ; Legube, B, Analyse de l'eau. 2016, P1600. https://www.unitheque.com/Livre/dunod/Technique_et_ingenierie/L_analyse_de_l_eau-93883.html.

- Guiral, D.; Arfi, R.; Bouvy, M.; Pagano, M.; Saint-Jean, L. Ecological organization and succession during natural recolonization of a tropical pond. Hydrobiologia, 1994, 229-242. [CrossRef]

- Gras, R.; Saint-Jean, L. ; Croissance en poids de quelques copépodes planctoniques du lac Tchad. Rev. d'Hydrobio. Trop. 1981, 14 : 135-47.

- Legendre, M.; Pagano, M.; Saint-Jean, L. Peuplements et biomasse zooplanctonique dans des étangs de pisciculture lagunaire (Layo, Côte d'Ivoire). Étude de la recolonisation après la mise en eau. Aquaculture, 1987, 67, 321-41.

- Dabbadie, L. Étude de la viabilité d'une pisciculture rurale à faible niveau d'intrant dans le Centre-Ouest de la Côte d'Ivoire : approche du réseau trophique. Thèse de doctorat de l'université de Paris 6 en océanologie biologique. 1996.

- Sipaúba-Tavares, L.H.; Bachion, M.A. Popula tion growth and development of two species of Cladocera, Moina micrura and Diaphanosoma birgei, in laboratory. Brazilian J. of Biology, 2002, 701-11.

- Masood, A.; Ahmad, K. ; Particulate matter forecasting using artificial neural network and support vector machine based models. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on ICT for Digital, Smart, and Sustainb. Develop. ICIDSSD 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, G.M. Tank culture of sunshine bass Morone chrysops X.M., saxatilis fry with freshwater rotifer B. calyciflorus and salmon starter meal as first food sources. J. of the world Aquacult. Society, 1994, 337-341. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, K.A.; Baly, R.L.; Hasan, I.; Naser, M.D.N.; Shahadat, M.D. , High density rotifer culture as live food for larval rearing in Carp hatcheries. World J. of Zoology, 2010, 110-114. https://scholar.google.com.hk/citations?user=--agAFoAAAAJ&hl=zh-CN.

- Xu, W.Y.; Cui, J.N. Effect of pH on survival, reproduction, egg viability and growth rate of five closely related rotifer species . Aquat. Ecol. 2008, 607-616. [CrossRef]

- Hodaifa, G.M.; Martínez, E.; Sánchez, S. Influence of pH on the Culture of Scenedesmus obliquus in Olive-mill Wastewater. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2009, 14, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Ignatius, B.; Sawant, P.B.; Santhosh, B.; Chadha, N.K. Productivity of the calanoid copepod Acartia tropica in response to different salinities and multigenerational acclimatization. Aquaculture, 2021, 531 – 735818. [CrossRef]

- Akodogbo , H.H.; Bonou, C.A.; Adandé, R.; Sossou,D.S.; Fiogbé, E.D.; Optimization of zooplankton production from pig dung optimal dose: renewed medium. Agricultural advances, 2015, 15-21. http://www.jebas.org/00300120022015/AKODOGBO%20et%20al%20JEBAS.pdf.

- Canovas, S.; Casellas, C.; Picot, B.; Pena, G.; Bontoux, J. Evolution annuelle du peuplement zooplanc tonique dans un lagunage à haut rendement et incidence du temps de séjour. Rev. des Sci. de l'Eau, 1991, 269-89.

- Carvalho, L.; Solimini, A. G.; Phillips, G.; Pietiläinen, O.P.; Moe, J.; Cardoso, A. C.; Solheim, A. L.; Ott, I.; Søndergaard, M.; Tartari, G.; Rekolainen, S. Site-specific chlorophyll reference conditions for lakes in Northern and Western Europe. Hydrobiologia, 2009, 633-5966.

- Liu, Y.; Guo, H.; Yang, P. Exploring the influence of lake water chemistry on chlorophyll a: A multivariate statistical model analysis. Ecol. Model. 2010, 221- 681688.

- Trevisan, G.V.; Forsberg, B.R. Relationships among ni trogen and total phosphorus, algal biomass and zooplankton density in the central Amazonia lakes. Hydrobiologia, 2007, 357-365.

- Magumba, D.; Maruyama, A.; Takagaki, M.; Kato, A.; Kikuchi, M. Relationships between Chlorophyll-a, Phosphorus and Nitrogen as Fundamentals for Controlling Phytoplankton Biomass in Lakes. Environ. Control Biol. 2013; 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Dai, S.; Wen, X.; Qian, C.; Luo, F.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Xi, Y. Chlorophyll-nutrient relationship changes with lake type, season and small-bodied zooplankton in a set of subtropical shallow lakes. Ecological Indicators, 2022, 135, art. no. 108571. [CrossRef]

- Ouba, A. Variabilité saisonnière et interannuelle (2000-2013) de l’abondance, de la biomasse et du spectre de taille du zooplancton dans le bassin Levantin. Ecosystèmes. Université Paris VI, Français. 2015, NNT: 2015PA066545. tel-01325647.

| Parameters | Cond (µs/cm) | pH | TDS | T°C | DO (mg/L) | Sal (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 225±6.12c | 7.33±0.37c | 162.4±4.86c | 28.34±0.38a | 4.7±0.17c | 0.21±0.00a |

| T1 | 574.13±76.72b | 6.73±0.40abc | 277.6±50.29b | 27.85±0.36a | 6.03±0.05ab | 0.33±0.01ab |

| T2 | 616.26±24.91a | 6.4±0.17ab | 397.73±39.03a | 29.36±0.08a | 6.03±0.05ab | 0.36±0.04ab |

| Characters | Regression coefficients | t-test at 5% significant (p<0.05) | Correlation type | |||||

| X | Y | a | b | r | r2 | N | p-value | CT |

| Chl-a (µg/L) | Biomass Rotifers | 74.05 | 239.39 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1999 | 0.07 | *** |

| Biomass Copepods | 76.18 | 217.98 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.34 | *** | ||

| Biomass copepods nauplii | 26.50 | 232.93 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.67 | ** | ||

| Biomass Cladocerans | 94.33 | 0.35 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.32 | *** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).