Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Elastic deformation: Elastic instability or buckling under elastic conditions, the shape of the vessel, and its stiffness, along with the characteristics of the materials, serve as safeguards against buckling.

- Brittle fracture: Brittle fractures have been observed in low-carbon steel vessels at low or moderate temperatures. During hydro testing, minor flaws have led to such fractures occurring in the temperatures ranging from 40 °F to 50 °F.

- Excessive plastic deformation: The stress limits for primary and secondary, as specified in ASME Section VIII, Division 2 [3], are designed to avert excessive plastic deformation and progressive failure.

- Stress rupture: Creep deformation occurs due to fatigue or cyclic loading, which leads to progressive fracture. While creep is influenced by time, fatigue is governed by cycles.

- Plastic instability: Incremental collapse is characterised by the progressive accumulation of cyclic strain that leads to damage and instability in vessels as a result of plastic deformation.

- High strain: Low cycle fatigue is influenced by strain and mainly occurs in materials that possess lower strength with high ductility.

- Stress corrosion: Chlorides are known to promote stress corrosion cracking in stainless steels, while caustic conditions can result in stress corrosion cracking in carbon steels. Selecting appropriate materials is crucial in these situations.

- Corrosion fatigue: This occurs when corrosive forces and fatigue effects occur simultaneously. Corrosion can reduce the fatigue lifespan by forming pits on the surface and accelerating crack development. The selection of material and its fatigue properties are crucial elements to be considered.

1.1. Buckling Failures in the Curved Structures

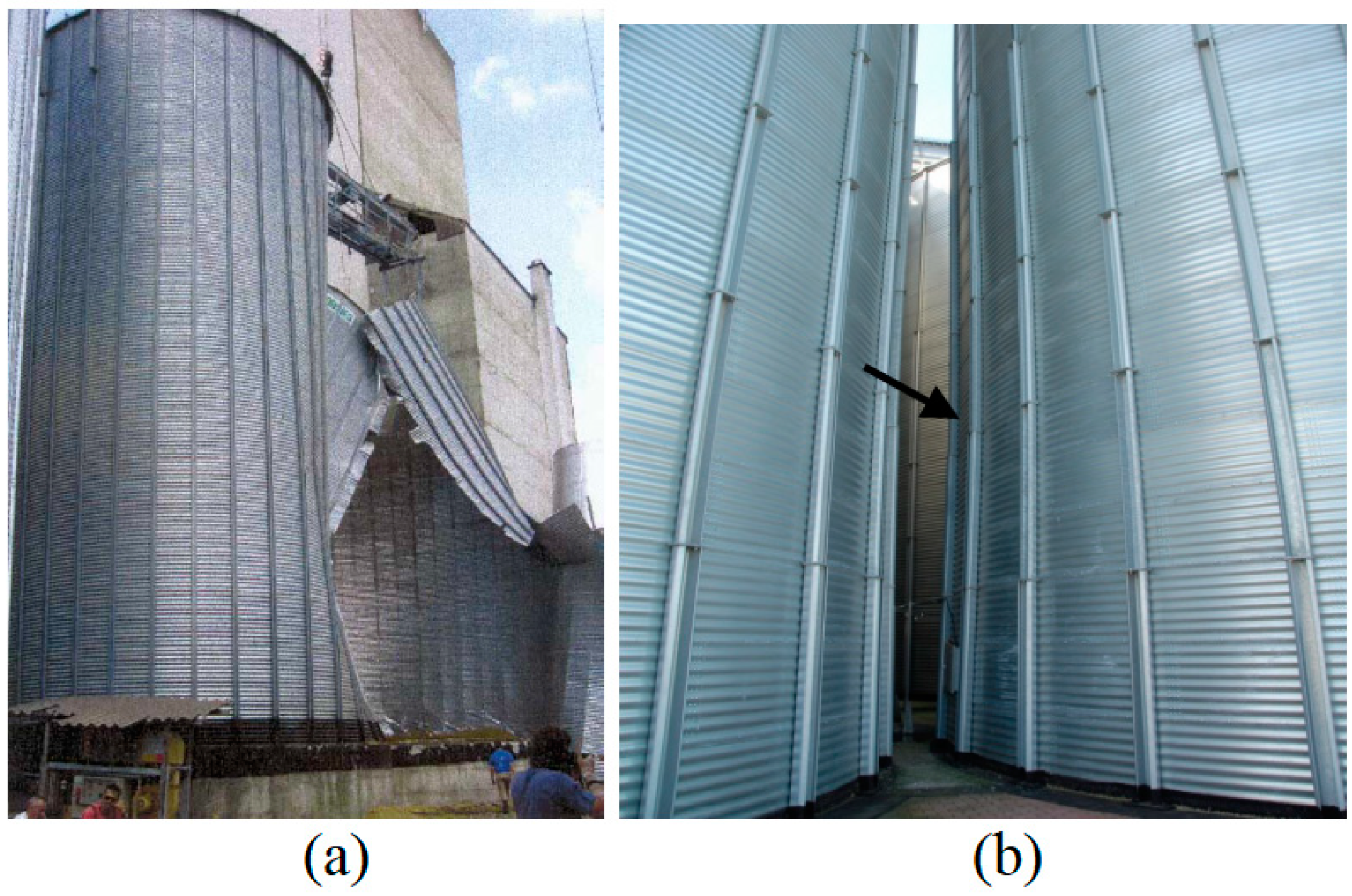

1.1.1. Failure due to Flow Discharge, Design Error and Crack

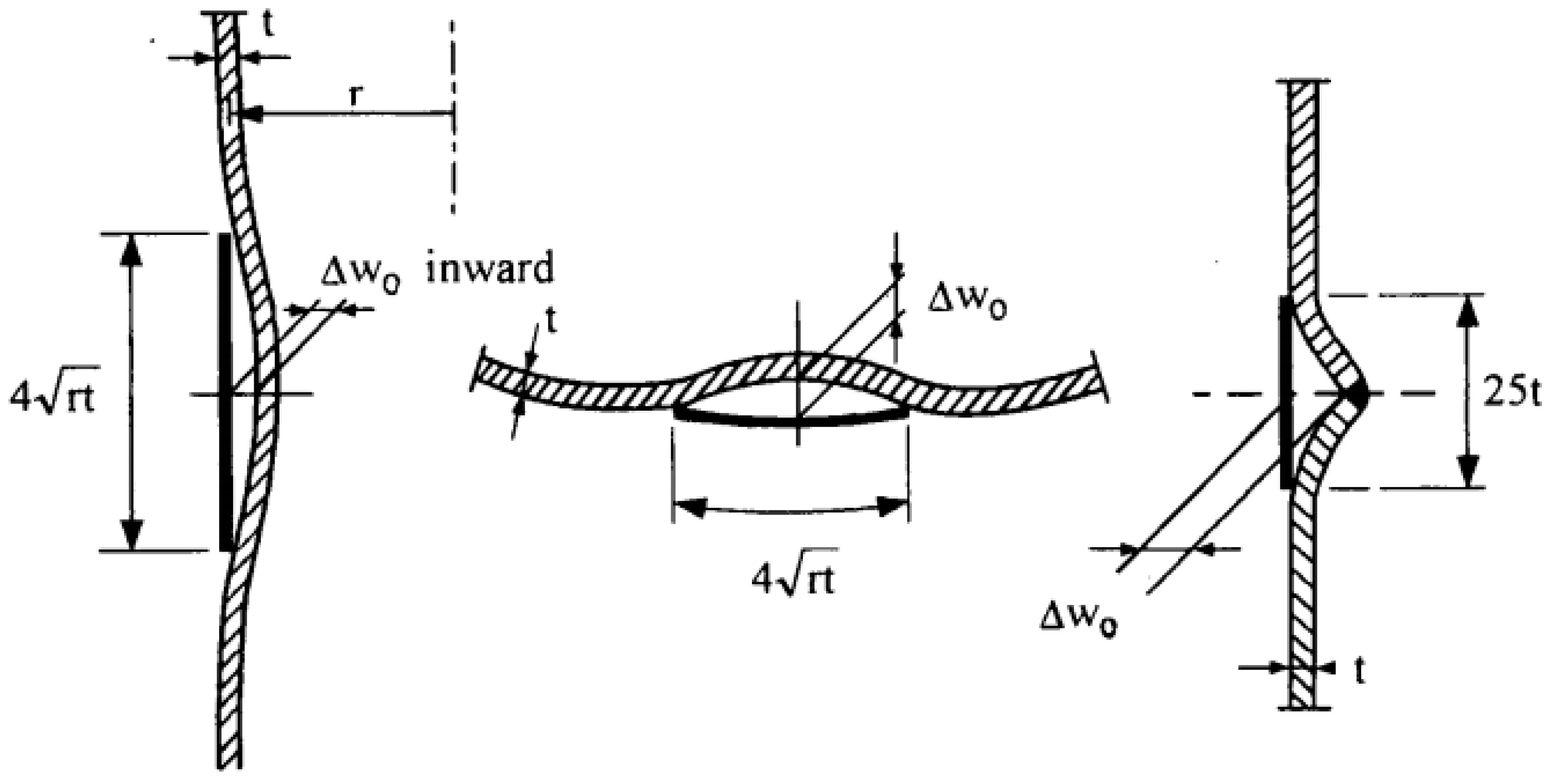

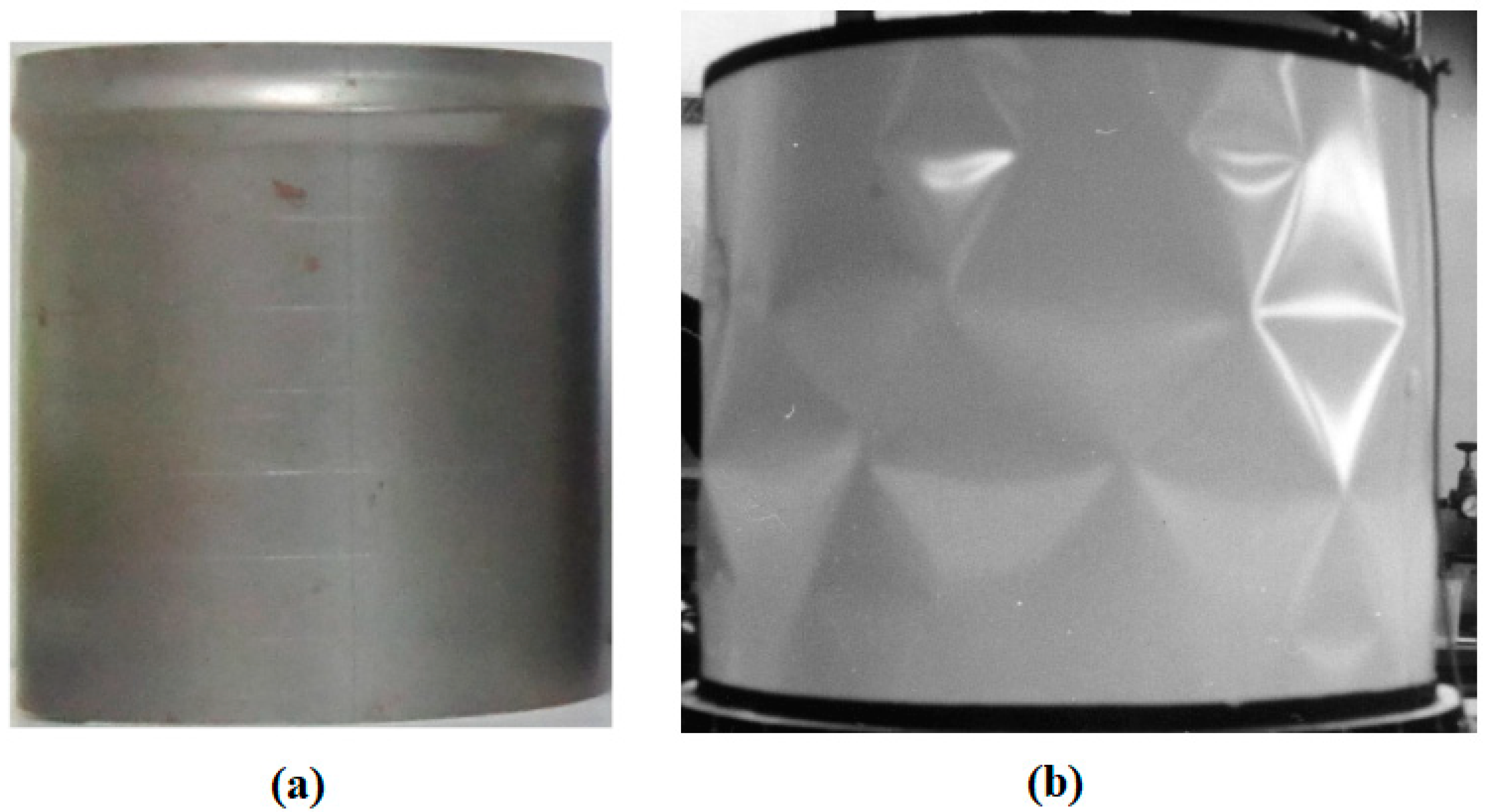

1.1.2. Failure due to the Initial Geometric Imperfection and/or Manufacturing Defect

1.1.3. Failure due to the Thermal Load and Ratcheting

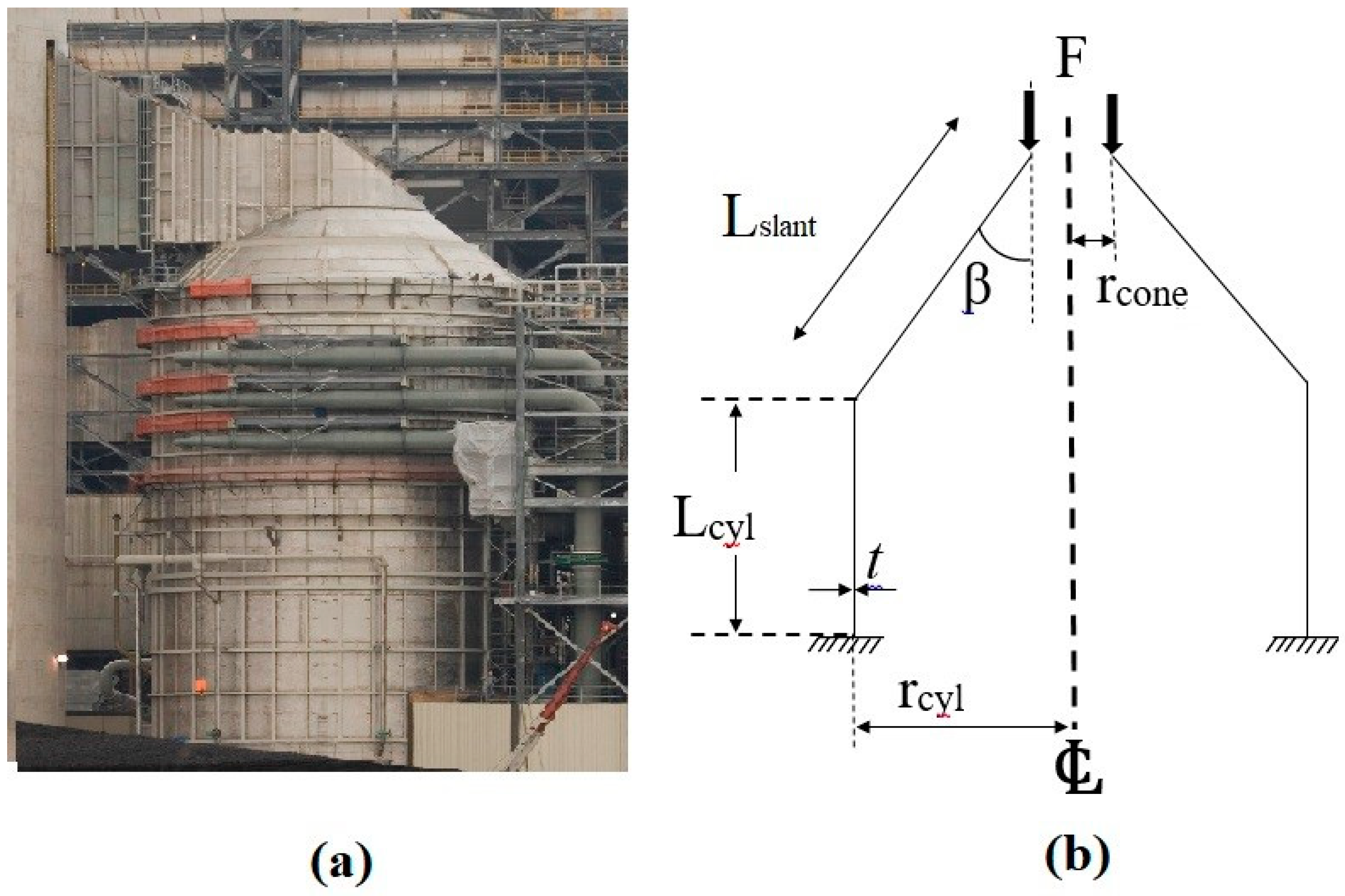

1.2. An Overview of Curved Shell Structures and Their Application

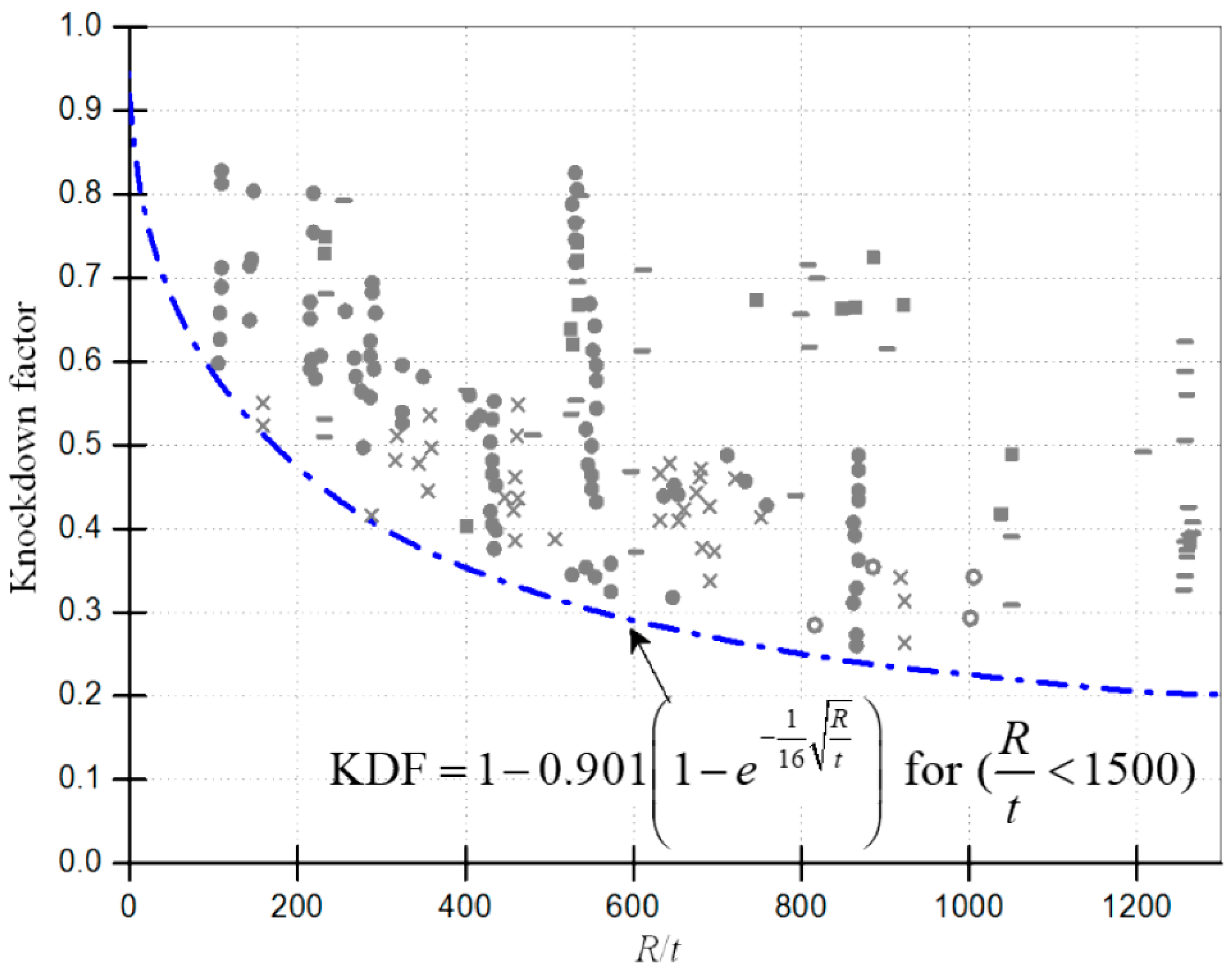

1.3. The Role of Imperfection in Design Against Buckling Failure

1.3.1. ASME BPVC Section VIII Div. 2 Approach Against Imperfection

- Method A: involves a five-step procedure for elastic analysis. Each load case is assessed to confirm that the elastic analysis fulfils the necessary validity criteria. Subsequently, distinct allowable membrane stress is determined for each load case by utilizing an eigenvalue buckling analysis alongside the relevant capacity reduction factor, βcr, as specified in Section 5.4.2.2. If any of the validity requirements detailed in the procedure are not satisfied, then Method B must be employed. Fabrication tolerances must comply with the specifications outlined in Section 4.4.4. If the elastic analysis fails to meet the validity criteria, Method B must be used.

- Method B: This analysis involves elastic-plastic buckling and considers geometric imperfections as described in 5.4.3.1.

1.3.2. Imperfection Magnitude According to ECCS

| Codes | Imperfection tolerance |

| DnV [94] | |

| ECCS [49] | |

| API [51] | |

| Eurocode 3 and Eurocode 9 [58,59] |

2. A Brief of the Development of Curved Shell Buckling Theory

2.1. Design of Curved Shell Structures and the Associated Considerations

2.2. Current Design Guideline

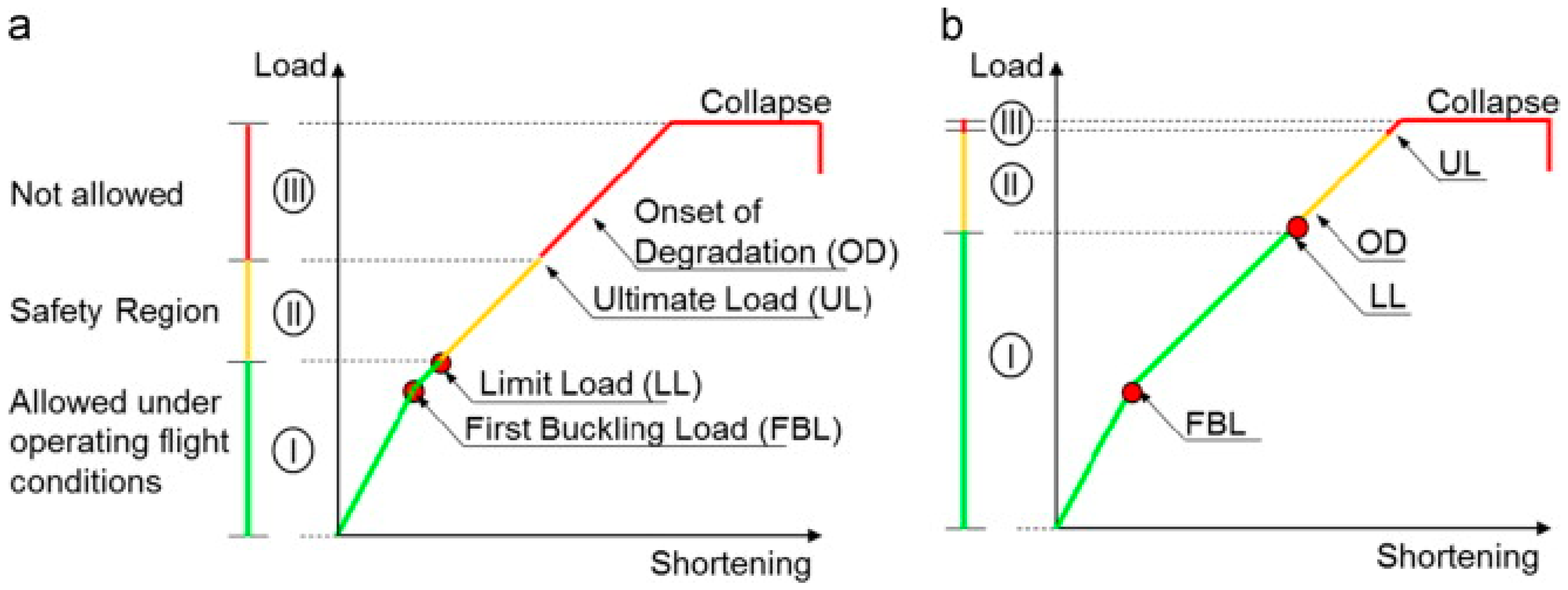

2.2.1. NASA Design Guidelines

2.2.2. ECCS Design Rule

2.2.3. PD 5500 Design Rule

2.3. Some Commentary on Current Design Guidelines and Their Limitations

3. Curved Shell Buckling

3.1. Experimental Works on Curved Shell Buckling

3.2. Numerical Works on Curved Shell Buckling

4. Research Direction and Future Works

5. Closure

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carson JW. Silo Failures: Case Histories and Lessons Learned. Proc, 3rd Israeli Conf for Conveying and Handling of Particulate Solids [Internet]. Dead Sea, Israel; 2000. Available from: www.jenike.com.

- Moss DR. Third Edition - Pressure vessel design manual [Internet]. Gulf Professional Publishing; 2004. Available from: http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=1EvxhJDf3JgC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=Pressure+vessel+design+manual&ots=RjPbQ5ANG_&sig=UVSDhxecNGGTPuEUMq-zbQB1Clc.

- American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME). ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code An International Code - Division 2 Section VIII Rules for Construction of Pressure Vessels [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.asme.org/cer.

- Dogangun A, Karaca Z, Durmus A, Sezen H. Cause of Damage and Failures in Silo Structures. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities. 2009;23:65–71.

- Piskoty G, Michel SA, Zgraggen M. Bursting of a corn silo – An interdisciplinary failure analysis. Eng Fail Anal. 2005;12:915–29. [CrossRef]

- Zaccari N, Cudemo M. Steel silo failure and reinforcement proposal. Eng Fail Anal. 2016;63:1–11. [CrossRef]

- EN 1991-1-4. EN 1991-1-4: Eurocode 1: Actions on structures - Part 1-4: General actions - Wind actions. 2010.

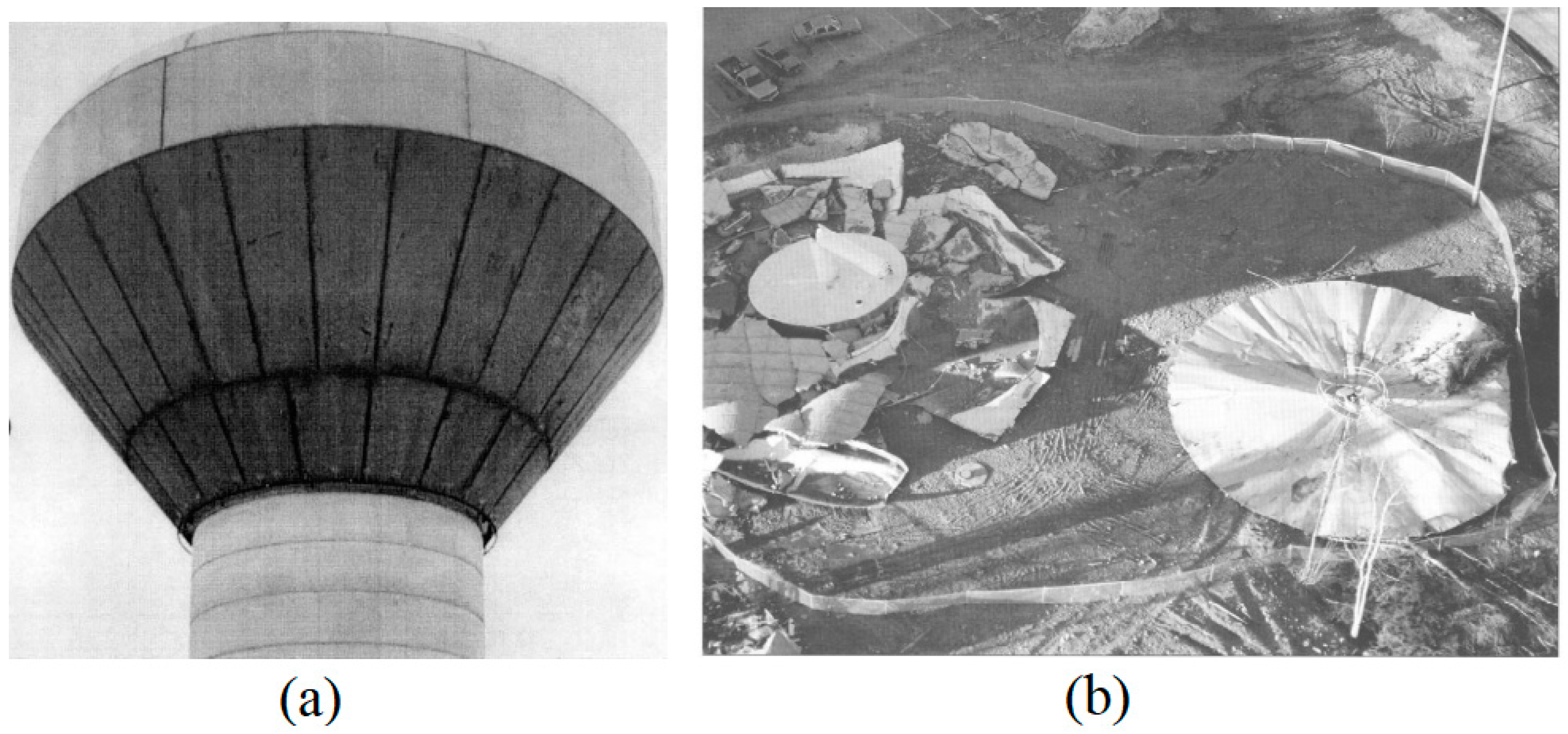

- Dawe JL, Seah CK, Abdel-Zaher AK. Investigation of the Regent Street Water Tower Collapse. Management & Operations. 1993;34–47. [CrossRef]

- Rejowski K, Iwicki P. Buckling analysis of cold formed silo column. Mechanics and Mechanical Engineering. 2016;20:109–20.

- Iwicki P, Rejowski K, Tejchman J. Stability of cylindrical steel silos composed of corrugated sheets and columns based on FE analyses versus Eurocode 3 approach. Eng Fail Anal [Internet]. 2015;57:444–69. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1350630715300595 . [CrossRef]

- Iwicki P, Tejchman J, Chróścielewski J. Dynamic FE simulations of buckling process in thin-walled cylindrical metal silos. Thin-Walled Structures. 2014;84:344–59. [CrossRef]

- Iwicki P, Wójcik M, Tejchman J. Failure of cylindrical steel silos composed of corrugated sheets and columns and repair methods using a sensitivity analysis. Eng Fail Anal [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2015 May 16];18:2064–83. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1350630711001567 . [CrossRef]

- Weller T. Recent experimental studies on the buckling Of integrally stringer-stiffened cylindrical shells. Haifa, Israel; 1970.

- Ansourian P. On the Buckling Analysis and Design of Silos and Tanks. J Constr Steel Res. 1992;23:273–94. [CrossRef]

- De Paor C, Kelliher D, Cronin K, Wright WMD, McSweeney SG. Prediction of vacuum-induced buckling pressures of thin-walled cylinders. Thin-Walled Structures [Internet]. 2012;55:1–10. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Piskoty G, Michel SA, Zgraggen M. Bursting of a corn silo – An interdisciplinary failure analysis. Eng Fail Anal. 2005;12:915–29. [CrossRef]

- Iwicki P, Wójcik M, Tejchman J. Failure of cylindrical steel silos composed of corrugated sheets and columns and repair methods using a sensitivity analysis. Eng Fail Anal. 2011;18:2064–83. [CrossRef]

- Cao QS, Zhao Y, Xing L, Zhang R, Li BY. Nonlinear buckling of cylindrical steel silos with fabrication cracks. Powder Technol. 2019;353:219–29. [CrossRef]

- Cao Q shuai, Zhao Y. Buckling strength of cylindrical steel tanks under harmonic settlement. Thin-Walled Structures [Internet]. 2010;48:391–400. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Bozozuk M. Foundation failure of the Vankleek Hill tower silo. Proceedings of the ASCE Specialty Conference on Performance of Earth and Earth-Supported Structures. Purdue University; 1972. p. 885–902.

- Galletly GD. Buckling of pressure vessels. Sci Prog. 1988;72:371–405.

- Yoshimura Y. On the mechanism of buckling of a circular cylindrical shell under axial compression. Technical Memorandum 1390. National Advisory Comittee for Aeronautics (NACA); 1955.

- Ifayefunmi O. Plastic buckling of axially compressed thick unstiffened steel cones. Ocean Engineering [Internet]. 2015;103:1–9. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Ifayefunmi O, Błachut J. Instabilities in imperfect thick cones subjected to axial compression and external pressure. Marine Structures. 2013;33:297–307. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi T, Mihara Y. Postbuckling Analyses of Elastic Cylindrical Shells Under Axial Compression. Volume 3: Design and Analysis. ASME; 2009. p. 745–54.

- Krasovsky V, Kostyrko VV. Experimental studying of buckling of stringer cylindrical shells under axial compression. Thin-Walled Structures [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2015 Jan 19];45:877–82. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0263823107001826 . [CrossRef]

- Yamaki N, Otomo K. Experiments on the postbuckling behavior of circular cylindrical shells under hydrostatic pressure. Exp Mech. 1975;13:299–304. [CrossRef]

- Ifayefunmi O. Buckling behavior of axially compressed cylindrical shells: Comparison of theoretical and experimental data. Thin-Walled Structures. 2016;98:558–64. [CrossRef]

- Lancaster ER, Calladine CR, Palmer SC. Paradoxical buckling behaviour of a thin cylindrical shell under axial compression. Int J Solids Struct. 2000;42:843–65. [CrossRef]

- Hayes B. Six case histories of pressure vessel failures. Eng Fail Anal. 1996;3:157–70. [CrossRef]

- Ifayefunmi O, Błachut J. The effect of shape, thickness and boundary imperfections on plastic buckling of cones. Proceedings of the ASME 2011 30th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering OMAE2011. 2011. p. 1–11.

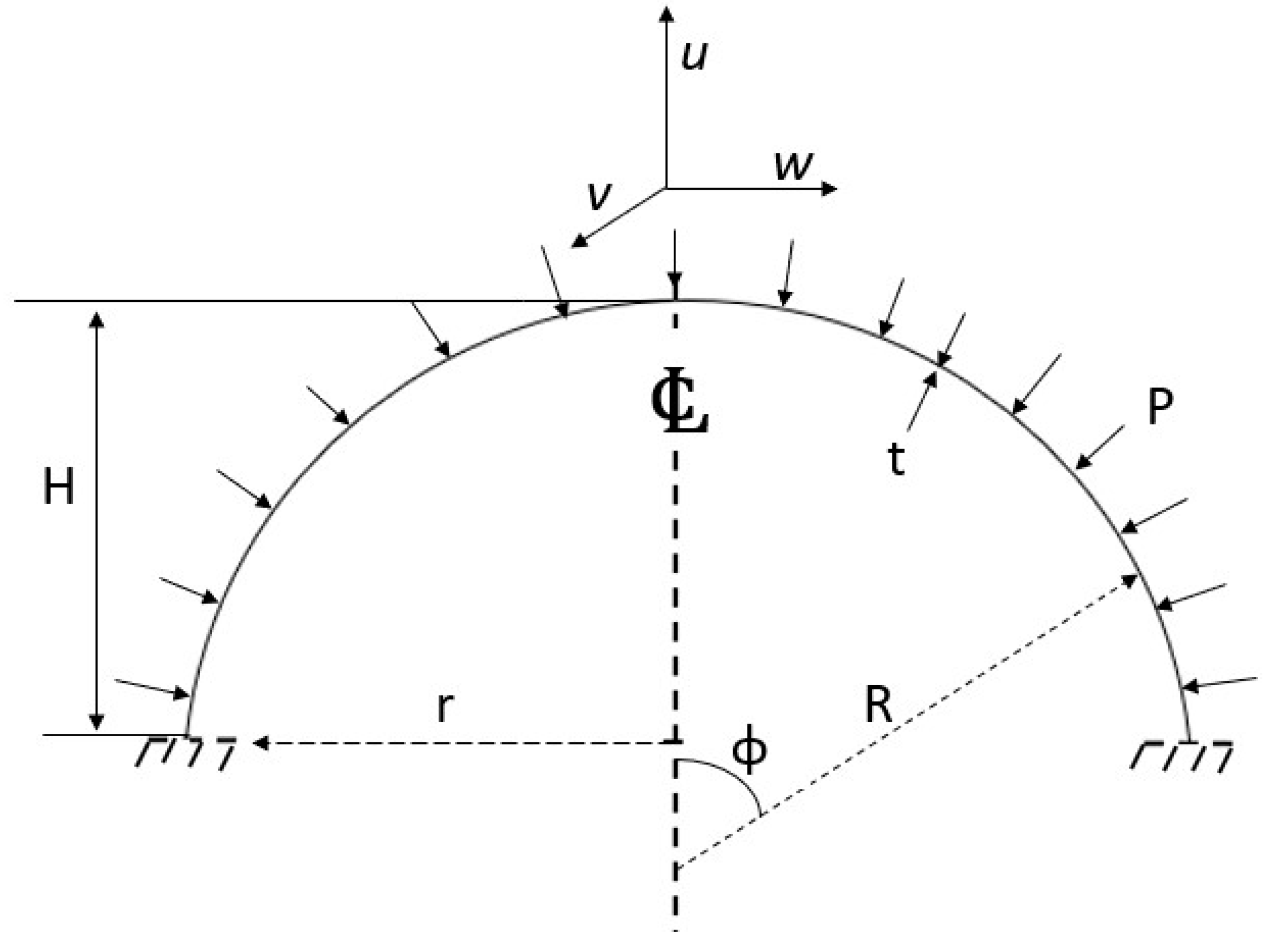

- Ismail MS, Muhammad al-Attas SM, Mahmud J. Buckling behaviour of steel dome cap design under external pressure. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping. 2024;208.

- Matiaskova L, Bilcik J, Soltesz J. Failure analysis of reinforced concrete walls of cylindrical silos under elevated temperatures. Eng Fail Anal. 2020;109. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Li X, Yang Y, Zhao S, Fu Z. Experimental and numerical investigation of the effect of temperature patterns on behaviour of large scale silo. Eng Fail Anal. 2018;91:543–53. [CrossRef]

- Tauseef SM, Abbasi T, Pompapathi V, Abbasi SA. Case studies of 28 major accidents of fires/explosions in storage tank farms in the backdrop of available codes/standards/models for safely configuring such tank farms. Process Safety and Environmental Protection. 2018;120:331–8. [CrossRef]

- Ifayefunmi O, Ismail MS. An overview of buckling and imperfection of cone-cylinder transition under various loading condition. Latin American Journal of Solids and Structures. 2020;17:1–21. [CrossRef]

- Ismail MS, Purbolaksono J, Andriyana A, Tan CJ, Muhammad N, Liew HL. The use of initial imperfection approach in design process and buckling failure evaluation of axially compressed composite cylindrical shells. Eng Fail Anal [Internet]. 2015;51:20–8. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1350630715000746 . [CrossRef]

- Çelik Aİ, Köse MM, Apay AC. Buckling conditions and strengthening by CFRP composite of cylindrical steel water tanks under seismic load. Earthquakes and Structures. 2024;27:97–111.

- Zeybek O, Celik Aİ, Ozkilic YO. Buckling of axially loaded shell structures made of stainless steel. Steel and Composite Structures [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Sep 22];48:681. Available from: http://techno-press.org/content/?page=article&journal=scs&volume=48&num=6&ordernum=6.

- Çelik Aİ, Zeybek Ö, Özkılıç YO. Effect of the initial imperfection on the response of the stainless steel shell structures. Steel and Composite Structures. 2024;50:705–20.

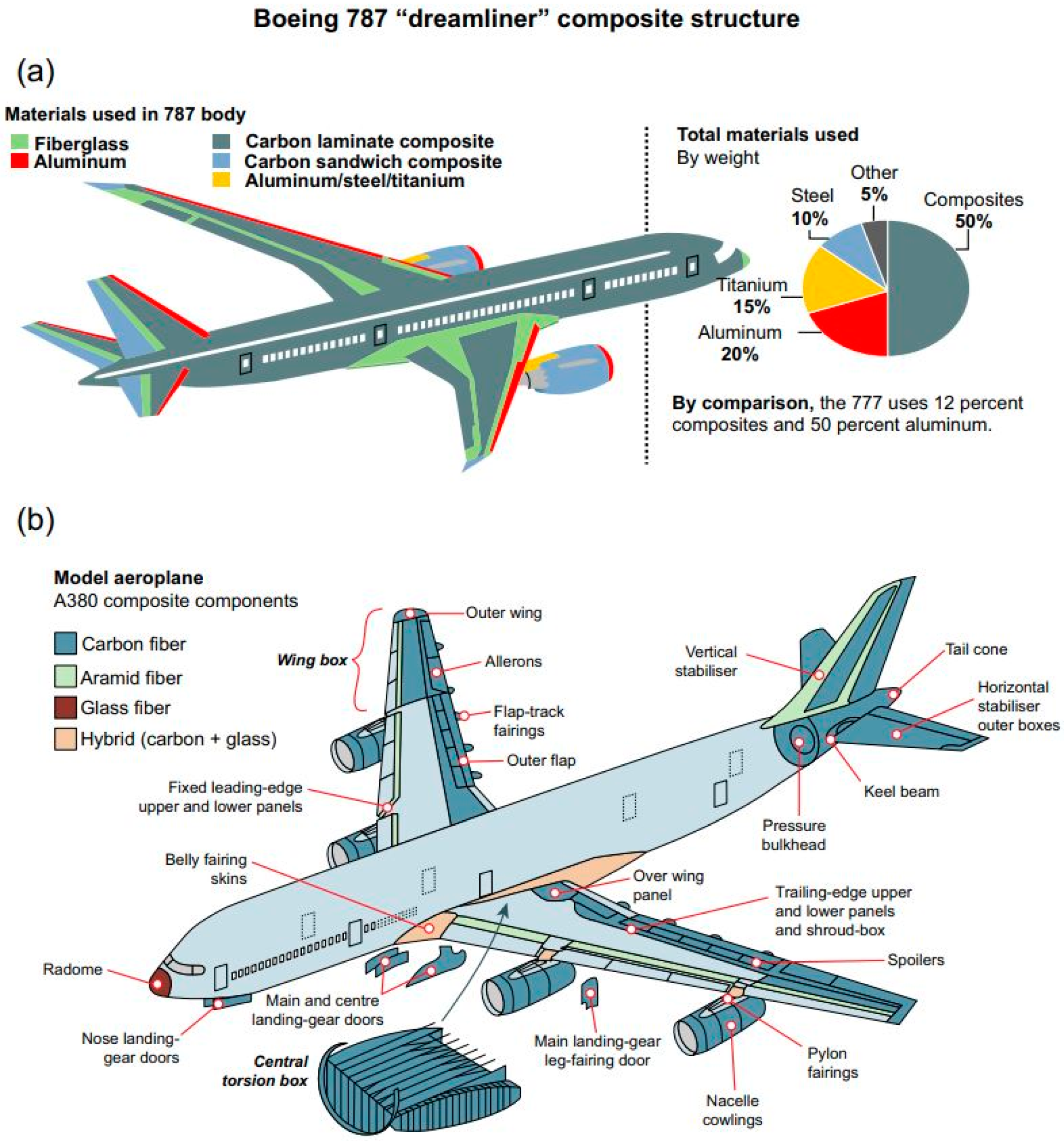

- Abramovich H. Introduction to composite materials. Stability and Vibrations of Thin-Walled Composite Structures. Elsevier; 2017. p. 1–47.

- Degenhardt R, Castro SGP, Arbelo MA, Zimmermann R, Khakimova R, Kling A. Future structural stability design for composite space and airframe structures. Thin-Walled Structures [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2014 Jul 21];81:29–38. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0263823114000676 . [CrossRef]

- Baker, Baker AA, Kelly DW. Composite Materials for Aircraft Structures [Internet]. American Institute of Aeronautics & Astronautics; 2004 [cited 2014 Jul 5]. Available from: http://books.google.com.my/books/about/Composite_Materials_for_Aircraft_Structu.html?id=5SPAIKFmFjcC&pgis=1.

- Schmidt H. Two decades of research on the stability of steel shell structures at the University of Essen ( 1985 – 2005 ): Experiments , evaluations , and impact on design standards. Advances in Structural Engineering. 2018;21:1–29.

- Knoedel Peter. Cylinder-cone-cylinder intersections under axial compression. Jullien JF, editor. London: Buckling of Shell Structures, on Land, in the Sea and in the Air; 1991.

- Schmidt H, Krysik R. Towards recommendations for shell stability design by means of numerically determined buckling loads. Jullien JF, editor. London: Buckling of Shell Structures, on Land, in the Sea and in the Air; 1991.

- Schmidt H. Stability of steel shell structures General Report. J Constr Steel Res. 2000;55:159–81.

- Schmidt H, Swadlo P. Strength and stability design of unstiffened cylinder/cone/cylinder and cone/cone shell assemblies under axial compression. In: Krupka V, Schneider P, editors. Proceeding International Conference. Brno, Czech Republic; 1997. p. 361–7.

- ECCS. Enhancement of ECCS design recommendations and developement of Eurocode 3 parts related to shells buckling. Buckling of shells. 5th ed. Brussels: European Convention for Constructional Steelwork. 1998. p. 384.

- Degenhardt R, Castro SGP, Arbelo MA, Zimmermann R, Khakimova R, Kling A. Future structural stability design for composite space and airframe structures. Thin-Walled Structures. 2014;81:29–38. [CrossRef]

- America Petroleum Institute. Bulletin on Stability Design of Cylindrical Shells. Washington D.C; 2000.

- American Bureau of Shipping. Buckling and Ultimate Strength Assessment for Offshore Structures. Houston, TX; 2004.

- Weingarten VI, Seide P, Peterson JP. Buckling of thin-walled circular cylinders. NASA SP-8007 Monograph. 1968;

- ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code. Section III, division 1: rules for construction of pressure vessels. ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York; 1986.

- BS5500. BS5500: specification of unfired fusion welded pressure vessels. British Standards Institution, London, England; 1988.

- ECCS. ECCS Publication - Buckling of Steel Shells: European Recommendations. 1988;

- ECCS. Buckling of steel shells : European recommendations. Buckling of shells 5th ed Brussels: European Convention for Constructional Steelwork. 1988;384.

- Eurocode 9. Eurocode 9 - Design of aluminium structures - Part 1-5: Shell structures. European comitee for standardization, Brussels, Belgium; 2006.

- Eurocode 3. Eurocode 3 - Design of steel structures - Part 1-6: Strength and stability of shell structures. 2007.

- Jasion P. Stability analysis of shells of revolution under pressure conditions. Thin-Walled Structures. 2009;47:311–7. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi SM, Anup S, Muthukumar R. Effect of geometrical parameters on mode shape and critical buckling load of dished shells under external pressure. Thin-Walled Structures. 2016;106:218–27. [CrossRef]

- Błachut J. Experimental Perspective on the Buckling of Pressure Vessel Components. Appl Mech Rev. 2014;66:1–24. [CrossRef]

- Błachut J, Magnucki K. Strength, Stability, and Optimization of Pressure Vessels: Review of Selected Problems. Appl Mech Rev. 2008;61:060801–1.

- Błachut J. Combined stability of geometrically imperfect conical shells. Thin-Walled Structures. 2013;67:121–8. [CrossRef]

- Wagner HNR, Hühne C, Niemann S. Robust knockdown factors for the design of spherical shells under external pressure: development and validation. Int J Mech Sci. 2018;141:58–77. [CrossRef]

- ECCS. Buckling of steel shells european design recommendations. Buckling of shells 5th ed Brussels: European Convention for Constructional Steelwork. 2008;

- DnV. DNV RP-C202: Buckling Strength of Shells. Det Norske Veritas AS. 2013;27.

- American Bureau of Shipping. Underwater Vehicles, Systems and Hyperbaric Facilities. 2021;77 p. in various pagings.

- Spagnoli A. Koiter circles in the buckling of axially compressed conical shells. Int J Solids Struct. 2003;40:6095–109. [CrossRef]

- Castro SGP, Zimmermann R, Arbelo MA, Khakimova R, Hilburger MW, Degenhardt R. Geometric imperfections and lower-bound methods used to calculate knock-down factors for axially compressed composite cylindrical shells. Thin-Walled Structures. 2014;74:118–32. [CrossRef]

- Song CY, Teng JG, Rotter JM. Imperfection sensitivity of thin elastic cylindrical shells subject to partial axial compression. Int J Solids Struct. 2004;41:7155–80. [CrossRef]

- Shakouri M, Spagnoli A, Kouchakzadeh MA. Re-interpreting simultaneous buckling modes of axially compressed isotropic conical shells. Thin-Walled Structures. 2014;84:360–8. [CrossRef]

- Ismail MS, Ifayefunmi O, Fadzullah SHSM. Buckling of imperfect cylinder-cone-cylinder transition under axial compression. Thin-Walled Structures. 2019;144:106250. [CrossRef]

- Ismail MS, Ifayefunmi O, Fadzullah SHSM, Johar M. Buckling of imperfect cone-cylinder transition subjected to external pressure. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping. 2020;187:104173. [CrossRef]

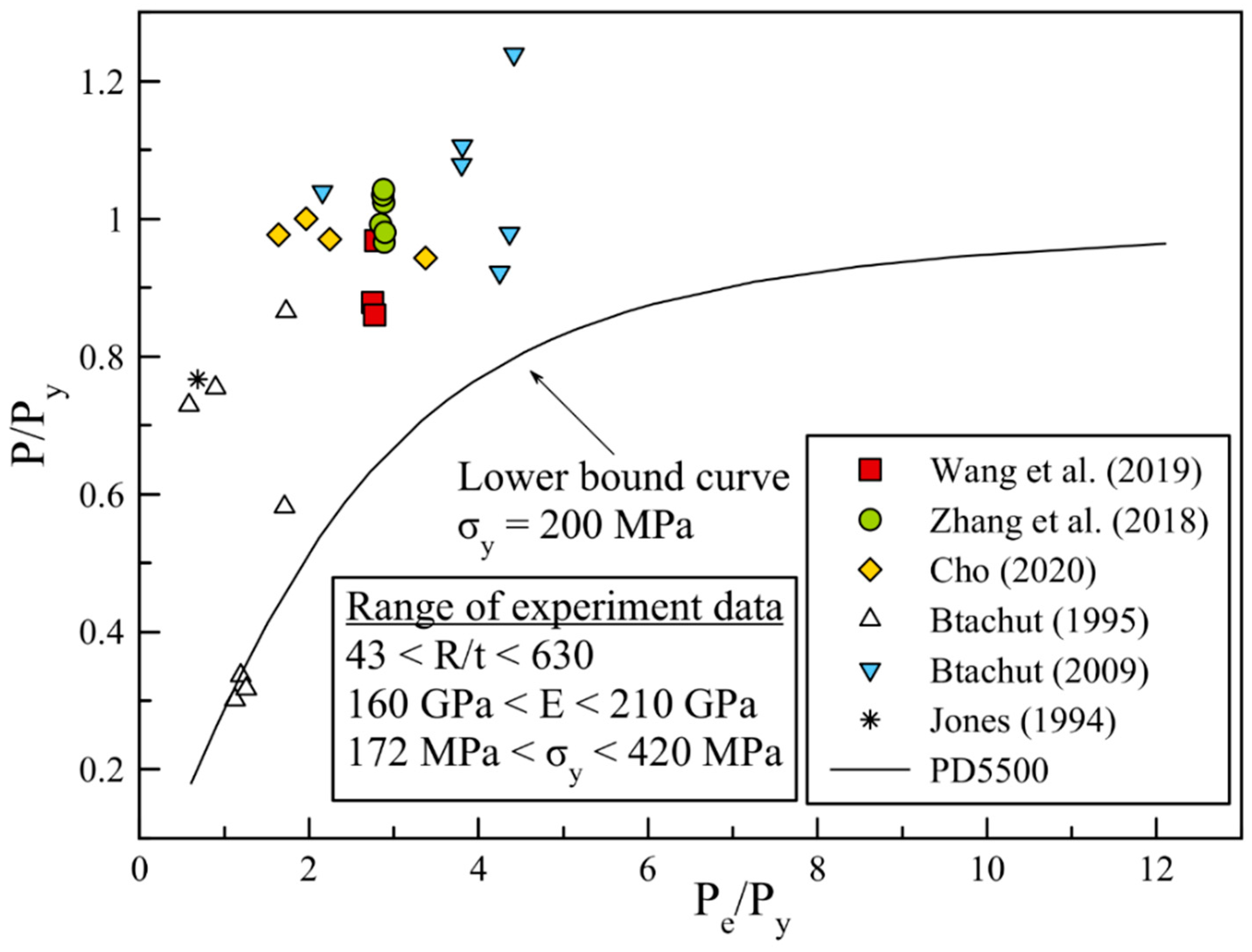

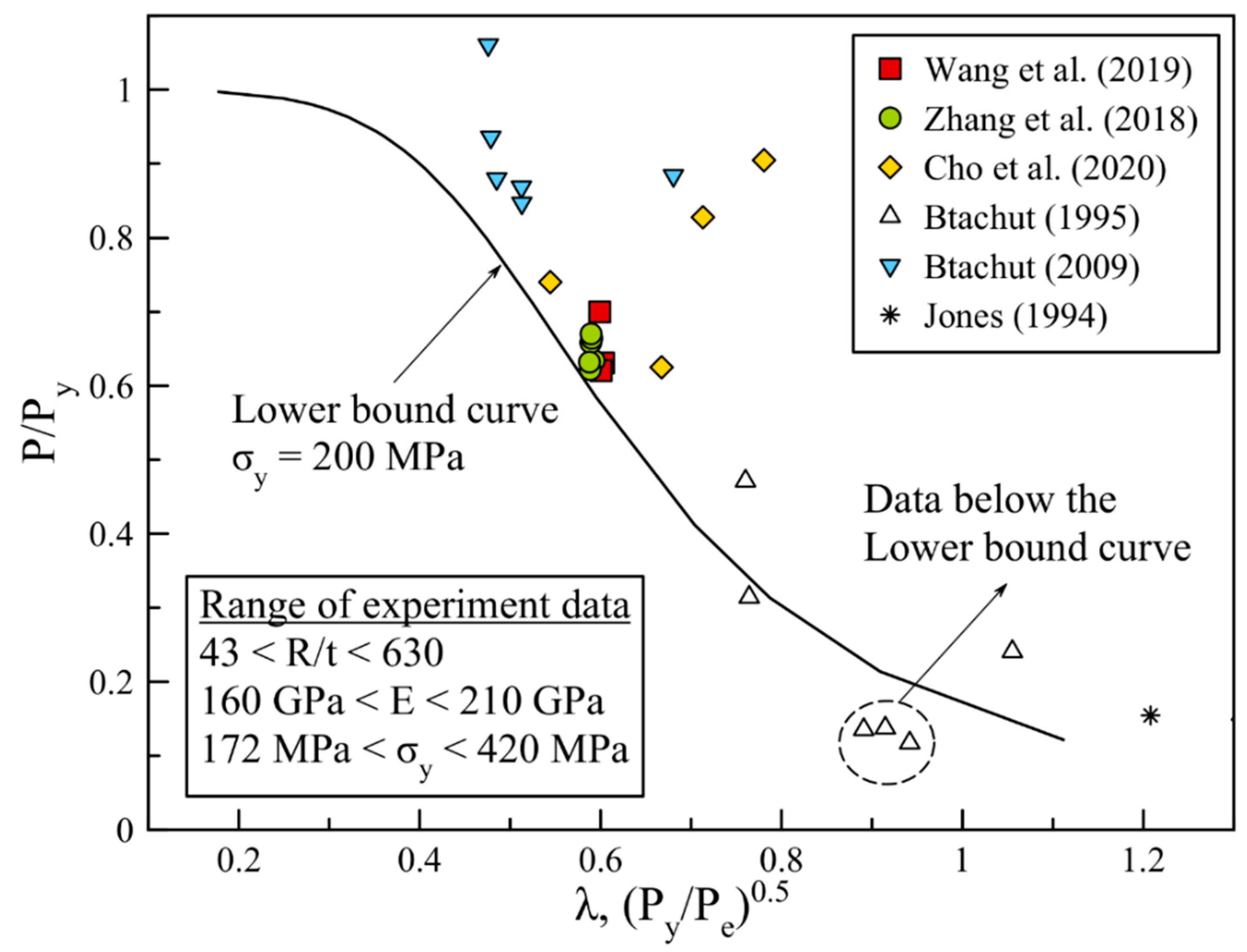

- Ismail MS, Mahmud J, Jailani A. Buckling of an imperfect spherical shell subjected to external pressure. Ocean Engineering. 2023;275:114118. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Wang Y, Wang F, Tang W. Buckling of stainless steel spherical caps subjected to uniform external pressure. Ships and Offshore Structures. 2018;13:779–85. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Zhang J, Xu X. Elastic–plastic buckling of externally pressurised hemispherical heads. Ships and Offshore Structures. 2019;14:829–38. [CrossRef]

- Cho SR, Muttaqie T, Lee SH, Paek J, Sohn JM. Ultimate Strength Assessment of Steel-Welded Hemispheres under External Hydrostatic Pressure. Journal of Marine Science and Application. 2020;19:615–33.

- Błachut J. Locally flattened or dented domes under external pressure. Thin-Walled Structures. 2015;97:44–52. [CrossRef]

- Galletly GD, Kruzelecki J, Moffat DG, Warrington B. Buckling of shallow torispherical domes subjected to external pressure — A comparison of experiment, theory, and design codes. J Strain Anal Eng Des. 1987;22:163–75.

- Błachut J. Buckling of composite domes with localised imperfections and subjected to external pressure. Compos Struct. 2016;153:746–54. [CrossRef]

- Błachut J, Galletly GD. Buckling strength of imperfect steel hemispheres. Thin-Walled Structures. 1995;23:1–20. [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej S, Marcinowski J. Experimental and numerical analyses of the buckling of steel, pressurized, spherical shells. Advances in Structural Engineering. 2018;21:2416–32. [CrossRef]

- Wagner HNR, Hühne C, Zhang J, Tang W, Khakimova R. Geometric imperfection and lower-bound analysis of spherical shells under external pressure. Thin-Walled Structures. 2019;143:106195. [CrossRef]

- Wagner HNR, Hühne C, Zhang J, Tang W. On the imperfection sensitivity and design of spherical domes under external pressure. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping. 2020;179:104015. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhang J, Tang W. Buckling Performances of Spherical Caps Under Uniform External Pressure. Journal of Marine Science and Application. 2020;19:96–100. [CrossRef]

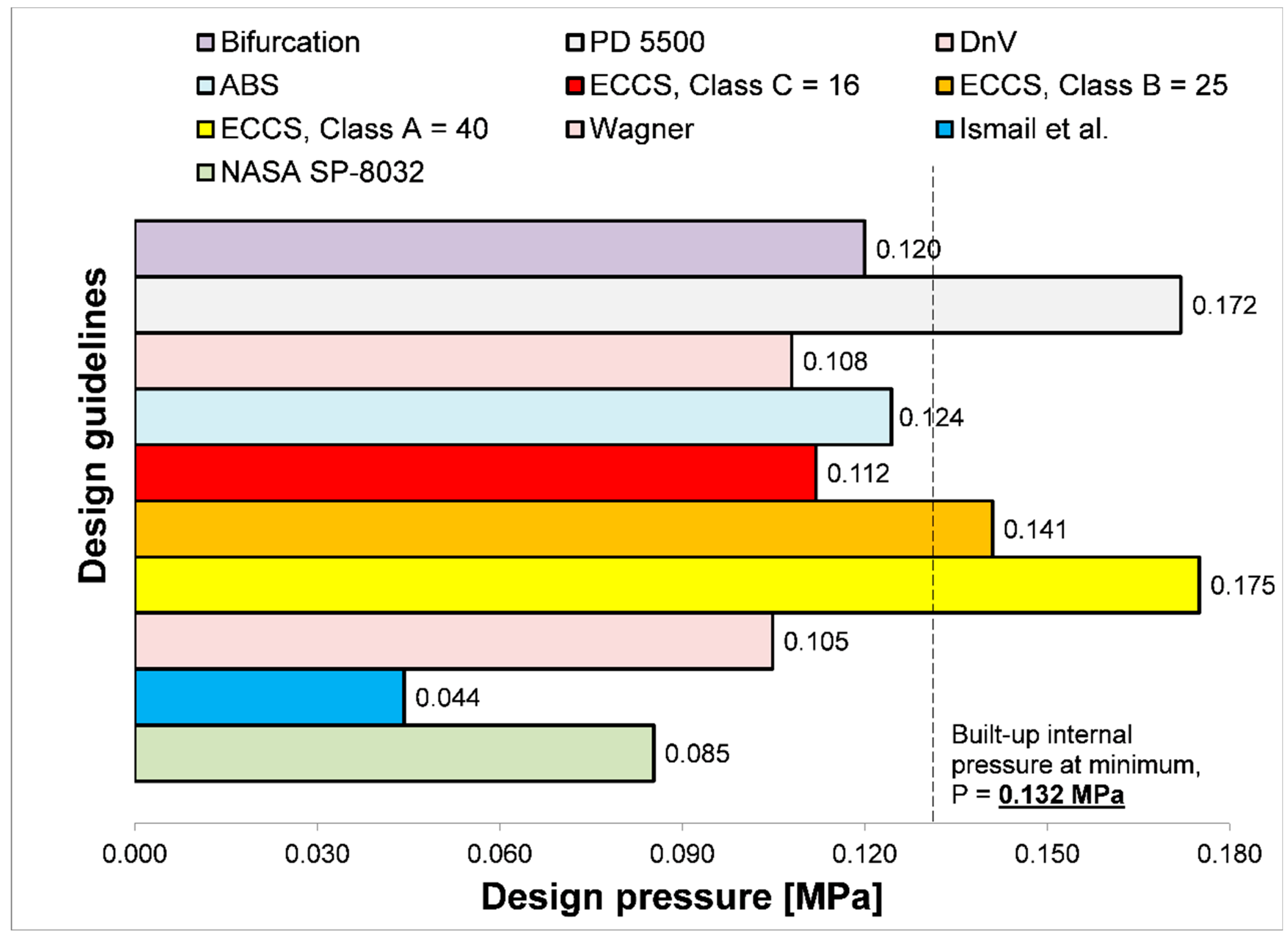

- Ismail MS, Mahmud J. Comparative evaluation of design codes for buckling assessment of a steel spherical shell. Latin American Journal of Solids and Structures. 2023;20:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Bai Y. Ultimate strength models for spherical shells under external pressure: a comparative study. Ships and Offshore Structures. 2022;1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zoelly R. Ueber ein Knickungsproblem an der Kugelschale Ober ein Knickungsproblein. 1915;

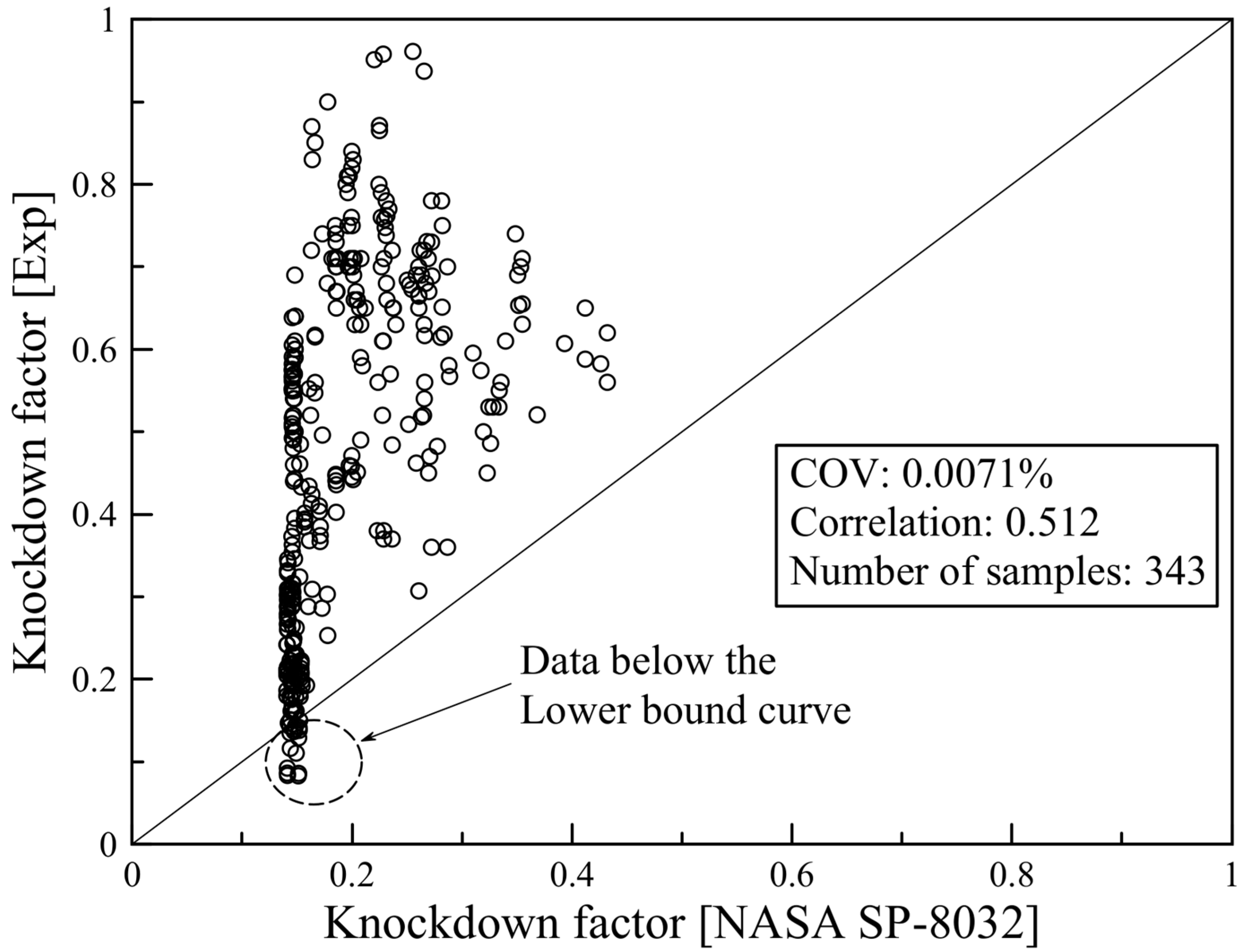

- Wingarten VI, Seide P. NASA SP-8032: Buckling of thin-walled doubly curved shells. 1969. p. 1–33.

- Evkin AY, Lykhachova O V. Energy barrier as a criterion for stability estimation of spherical shell under uniform external pressure. Int J Solids Struct. 2017;118–119:1339–51. [CrossRef]

- ECCS. Enhancement of ECCS design recommendations and development of Eurocode 3 parts related to shells buckling. Buckling of shells. 5th ed. Brussels: European Convention for Constructional Steelwork. 1998.

- Rotter JM. Development of Proposed European Design Rules for Buckling of Axially Compressed Cylinders. Advances in Structural Engineering. 2017;1:273–86. [CrossRef]

- DnV. Buckling strength analysis. Det Norske Veritas AS. 1995;1–44.

- Rotter JM. Development of Proposed European Design Rules for Buckling of Axially Compressed Cylinders. Advances in Structural Engineering. 2017;1:273–86. [CrossRef]

- Robertson A. The strength of tubular struts. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series A,. 1928;

- Flügge W. Die Stabilität der Kreiszylinderschale. Ingenieur-Archiv. 1932;3:463–506. [CrossRef]

- Wilson WM, Newmark NM. The strength of thin cylindrical shells as columns. Selected Papers By Nathan M Newmark. 1933;

- Donnell BLH. A New Theory for the Buckling of Thin Cylinders Under Axial Com pression and Bending. AER-56-12. 1935;

- Simitses GJ. Buckling and postbuckling of imperfect cylindrical shells : A review. Appl Mech Rev. 1986;39. [CrossRef]

- Stein M. The influence of prebuckling deformations and stresses on the buckling of perfect cylinders. National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 1964.

- Stein M. The Effect on the Buckling Of Perfect Cylinders Of Prebuckling Deformations And Stresses Induced By Edge Support. 1962;

- Ohira H. Linear Local Buckling Theory of Axially Compressed Cylinders and Various Eigenvalues. Space Technology and Science: Proceedings of the fifth international symposium held in Tokyo in 1963 Editor-in-Chief: Tsuyoshi Hayashi Editorial Board: R Akiba. 1964;

- Hoff NJ, Soong T-C. Buckling of circular cylindrical shells in axial compression. Int J Mech Sci. 1965;7:489–520. [CrossRef]

- Hoff NJ, Rehfield LW. Buckling of Axially Compressed Circular Cylindrical Shells at Stresses Smaller Than the Classical Critical Value. J Appl Mech. 1965;32:542. [CrossRef]

- Karman T Von, Tsien H-S. The Buckling of Thin Cylindrical Shells under Axial Compression. Journal Appl ied Mechanical. 1965;32:533–8.

- Michielsen HF. The Behavior of Thin Cylindrical Shells After Buckling Under Axial Compression. Journal of the aeronautical sciences. 1948;15. [CrossRef]

- Kempner J. Postbuckling Behavior of Axially Compressed Circular Cylindrical Shells. 2012; [CrossRef]

- Almroth BO. Postbuckling Behavior Of Axially Compressed Circular Cylinders. AIAA Journal. 1963;Vol. 1:630–3. [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt R, Tessmer J, Kling A. Collapse behaviour of thin-walled cfrp structures due to material and geometric nonlinearities – experiments and simulation. :1–10.

- Ismail MS, Mahmud J. Buckling and Postbuckling Analysis of Stiffened Cylindrical Shells Subjected to Axial Compression and External Pressure. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 23];519–29. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-97-0169-8_42.

- Orf J, Kärger L, Degenhardt R, Bethge A. The influence of imperfections on the buckling behaviour of unstiffened CFRP-cylinders. In proceeding of: 2nd International Conference on Buckling and Postbuckling Behaviour of Composite Laminated Shell Structures. 2008. p. 2–5.

- Degenhardt R, Wiedemann M. Future challenges in the design of structures made of CFRP. 2011;

- Bisagni C, Cordisco P. An experimental investigation into the buckling and post-buckling of CFRP shells under combined axial and torsion loading. Compos Struct. 2003;60:391–402. [CrossRef]

- Weingarten VI, Seide P, Peterson JP. Buckling of thin-walled circular cylinders. NASA SP-8007 Monograph. 1968;

- ECCS. ECCS Publication - Buckling of Steel Shells: European Recommendations. 1988;

- Friedrich L, Schröder K-U. Discrepancy between boundary conditions and load introduction of full-scale built-in and sub-scale experimental shell structures of space launcher vehicles. Thin-Walled Structures. 2016;98:403–15. [CrossRef]

- EN 1993-4-1. Eurocode 3: Design of steel structures - Part 4 - 1: Silos. 2007.

- PD 5500. Specification for unfired fusion welded pressure vessels This publication is not to be regarded as a British Standard . 2009;904.

- Ismail MS, Mahmud J. Comparative evaluation of design codes for buckling assessment of a steel spherical shell. Latin American Journal of Solids and Structures. 2023;20:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zoelly R. Ueber ein Knickungsproblem an der Kugelschale Ober ein Knickungsproblein. 1915;

- Wingarten VI, Seide P. NASA SP-8032: Buckling of thin-walled doubly curved shells. 1969.

- Wang J, Fajuyitan OK, Orabi MA, Rotter JM, Sadowski AJ. Cylindrical shells under uniform bending in the framework of Reference Resistance Design. J Constr Steel Res. 2020;166. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Bai Y. Ultimate strength models for spherical shells under external pressure: a comparative study. Ships and Offshore Structures [Internet]. 2022;1–12. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- American Bureau of Shipping. Buckling and Ultimate Strength Assessment for Offshore Structures. Houston, TX; 2004.

- DnV. DNV RP-C202: Buckling Strength of Shells. Det Norske Veritas AS. 2013;27.

- Russian Maritime Register of Shipping [RS]. Rules for the classification and construction of manned submersibles. Saint Petersburg: RS; 2004.

- Galletly GD, Blachut J. Buckling design of imperfect welded hemispherical shells subjected to external pressure. Proc Inst Mech Eng C J Mech Eng Sci. 1991; [CrossRef]

- Wagner HNR, Hühne C, Niemann S. Robust knockdown factors for the design of spherical shells under external pressure: development and validation. Int J Mech Sci. 2018;141:58–77. [CrossRef]

- Evkin AY, Lykhachova O V. Design buckling pressure for thin spherical shells: Development and validation. Int J Solids Struct [Internet]. 2019;156–157:61–72. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Błachut J, Galletly GD. Buckling strength of imperfect steel hemispheres. Thin-Walled Structures. 1995;23:1–20. [CrossRef]

- Jones DRH. Buckling failures of pressurised vessels-two case studies. Eng Fail Anal. 1994;1:155–67. [CrossRef]

- Ismail MS, Mahmud J, Jailani A. Buckling of an imperfect spherical shell subjected to external pressure. Ocean Engineering [Internet]. 2023;275:114118. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0029801823005024 . [CrossRef]

- Almroth BO, Holmes AMC, Brush DO. An experimental study of the buckling of cylinders under axial compression. Exp Mech [Internet]. 1964 [cited 2015 Apr 11];4:263–70. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF02323088 . [CrossRef]

- Haynie WT, Hilburger MW. Comparison of Methods to Predict Lower Bound Buckling Loads of Cylinders under Axial Compression. 51st AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference. 2010;1–22.

- Haynie WT, Hilburger MW, Kriegesmann B. Validation of Lower-Bound Estimates for Compression-Loaded Cylindrical Shells. 51st AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference. 2010;1–12.

- Nemeth MP, Starnes JH. The NASA Monographs Design Recommendations A Review on Shell Stability and Suggested. NASA/TP-1998-206290. 1998;

- Degenhardt R, Bethge A, Kling A, Zimmermann R, Rohwer K. Probabilistic approach for better buckling knock-down factors of CFRP cylindrical shells – tests and analyses. 18th Engineering Mechanics Division Conference (EMD2007). 2007. p. 1–6.

- Elghazouli AY, Chryssanthopoulos MK, Spagnoli A. Experimental response of glass-reinforced plastic cylinders under axial compression. Marine Structures. 1998;11:347–71. [CrossRef]

- Chryssanthopoulos MK, Elghazouli AY, Esong IE. Compression tests on anti-symmetric two-ply GFRP cylinders. Compos B Eng. 1999;30:335–50. [CrossRef]

- Hilburger MW, Starnes JH. Effects of imperfections on the buckling response of compression-loaded composite shells. Int J Non Linear Mech [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2014 Feb 20];37:623–43. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020746201000889 . [CrossRef]

- Geier B, Klein H, Zimmermann R. Experiments on buckling of CFRP cylindrical shells under non-uniform axial load. int conference on composite engineering, ICCE/1 [Internet]. 1994 [cited 2014 Feb 5]; Available from: http://scholar.google.com.my/scholar?q=Experiments+on+buckling+of+CFRP+cylindrical+shells+under+non-uniform+axial+load&btnG=&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5#2.

- Han S-C, Lee S-Y, Rus G. Postbuckling analysis of laminated composite plates subjected to the combination of in-plane shear, compression and lateral loading. Int J Solids Struct [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2013 Dec 19];43:5713–35. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0020768305005275 . [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick SW, Holmes BS. Axial buckling of a thin cylindrical shell: experiments and calculations. Computational experiment. 1989;176:67–74.

- Arbocz J, Hol JMAM. Collapse of Axially Compressed Cylindrical Shells with Random Imperfections. Thin-Walled Structures. 1995;23:131–58. [CrossRef]

- Starnes JH, Hilburger MW. Using High-Fidelity Analysis Methods and Experimental Results to Account for the Effects of Imperfections on the Buckling Response of Composite Shell Structures. Reduction of Military Vehicle Acquisition Time and Cost through Advanced Modelling and Virtual Simulation. 2002. p. 22–5.

- Starnes JH, Hilburger MW. Using High-Fidelity Analysis Methods and Experimental Results to account for the Imperfections on the Buckling Response of Composite Shells Structures. 2002;

- Weller T, Singer J. Experimental studies on buckling of 7075-T6 Aluminium alloy integrally stringer-stiffened shells. TAE Report. 1971;

- Hilburger MW. Developing the Next Generation Shell Buckling Design Factors and Technologies. 53rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference Honolulu, Hawaii. 2007.

- Hilburger MW, Nemeth MP, Starnes JH. Shell Buckling Design Criteria Based on Manufacturing Imperfection Signatures. AIAA Journal. 2006;44:654–63.

- Hilburger MW, Arbor A, Starnes JH, Waas AM. A numerical and experimental study of the response of selected compression-loaded composite shells with cutouts. AIAA-1998-1988, AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference and Exhibit, 39th, and AIAA/ASME/AHS Adaptive Structures Forum, Long Beach, CA. 1998.

- Hilburger MW, Arbor A, Starnes JH, Waas AM. The Response of Composite Cylindrical Shells with Cutouts and Subjected To Internal Pressure and Axial Compression Loads. Proceedings of the 39th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, AIAA-98-1768, AIAA, Washington, DC. 1998. p. 576–84.

- Rahimi GH, Zandi M, Rasouli SF. Analysis of the effect of stiffener profile on buckling strength in composite isogrid stiffened shell under axial loading. Aerosp Sci Technol [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2015 Jan 19];24:198–203. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1270963811001921 . [CrossRef]

- Andrianov IV, Verbonol VM, Awrejcewicz J. Buckling analysis of discretely stringer-stiffened cylindrical shells. Int J Mech Sci [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2015 Jan 19];48:1505–15. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0020740306001391.

- Bisagni C, Cordisco P. Testing of Stiffened Composite Cylindrical Shells in the Postbuckling Range Until Failure. AIAA Journal. 2004;42:1806–17. [CrossRef]

- Chryssanthopoulos MK, C. Poggi. Stochastic Imperfection Modelling in Shell Buckling Studies Stiffener depth. Thin-Walled Structures. 1995;23:179–200.

- Ismail MS, Purbolaksono J, Muhammad N, Andriyana A, Liew HL. Statistical analysis of imperfection effect on cylindrical buckling response. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng [Internet]. 2015;100:012003. Available from: http://stacks.iop.org/1757-899X/100/i=1/a=012003?key=crossref.f281b6578e78d76a69267c9a663f938c.

- Frieze PA. The experimental response of flat-bar stiffeners in cylinders under external pressure. Marine Structures [Internet]. 1994 [cited 2017 Feb 20];7:213–30. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0951833994900256 . [CrossRef]

- Maali M, Showkati H, Mahdi Fatemi S. Investigation of the buckling behavior of conical shells under weld-induced imperfections. Thin-Walled Structures [Internet]. 2012;57:13–24. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Pircher M, Bridge R. The influence of circumferential weld-induced imperfections on the buckling of silos and tanks. J Constr Steel Res. 2001;57:569–80. [CrossRef]

- Pircher M, Bridge R. Effects of weld-induced circumferential imperfections on the buckling of cylindrical thin-walled shells. Transactions on Engineering Sciences. 1998;19:112–20.

- Hao P, Wang B, Tian K, Du K, Zhang X. Influence of imperfection distributions for cylindrical stiffened shells with weld lands. Thin-Walled Structures. 2015;93:177–87. [CrossRef]

- Teng JG, Zhao Y. On the buckling failure of a pressure vessel with a conical end. Eng Fail Anal [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2015 May 16];7:261–80. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1350630799000205 . [CrossRef]

- Anwen W. Stresses and stability for the cone-cylinder shells with toroidal transition. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping. 1998;75:49–56. [CrossRef]

- Teng JG, Zhao Y. On the buckling failure of a pressure vessel with a conical end. Eng Fail Anal. 2000;7:261–80. [CrossRef]

- Teng JG. Collapse Strength of Complex Metal Shell Intersections by the Effective Area Method. J Press Vessel Technol. 1998;120:217–22. [CrossRef]

- Arnold PC, Mclean AG, Roberts AW. Bulk solids : storage, flow and handling. 1980.

- Jenike AWW, Johanson JRR, Carson JWW. Bin Loads — Part 2 : Concepts. Journal of Engineering for Industry. 1973;95:1–5.

- Jenike AWW, Johanson JR, Carson JWW. Bin Loads—Part 3: lass-Flow Bins. Journal of Engineering for Industry. 1973;95:6–12.

- Moore DW, White GM, Ross IJ. Friction of Wheat on Corrugated Metal Surfaces. Transactions of the American Society of Agricultural Engineers. 1984;27:1842–7.

- Rotter JM. On the Strength and Stability of Light Gauge Silos. Eighth International Specialty Conference on Cold-Formed Steel Structures. St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.; 1986.

- AS1210. AS1210: SAA unfired pressure vessel code. Association of Standards - Australia, Sydney, Australia, Sydney, Australia; 1990.

- Brogan FA, Almroth BO. Practical Methods for Elastic Collapse Analysis for Shell Structures. AIAA Journal. 1971;9:2321–6. [CrossRef]

- Riks E, Rankin CC, Brogan FA. The Numerical Simulation of the Collapse Process of Axially Compressed Cylindrical Shells with Measured Imperfections. Technical Report LR-705. 1992.

- Riks E, Rankin CC, Brogan FA. On the solution of mode jumping phenomena shell structures in thin-walled. Computational method in applied mechanics and engineering. 1996;7825.

- Hilburger MW, Starnes JH. Effects of imperfections of the buckling response of composite shells. Thin-Walled Structures [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2013 Dec 18];42:369–97. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0263823103001423 . [CrossRef]

- Ambur DR, Jaunky N, Hilburger MW. Progressive Failure Studies of Stiffened Panels Subjected to Shear Loading. 43rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference [Internet]. 2002; Available from: http://arc.aiaa.org/doi/abs/10.2514/6.2002-1404.

- Kriegesmann B, Hilburger MW, Rolfes R. The Effects of Geometric and Loading Imperfections on the Response and Lower-Bound Buckling Load of a Compression-Loaded Cylindrical Shell. 53rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference 20th AIAA/ASME/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference 14th AIAA [Internet]. 2012;1–10. Available from: http://arc.aiaa.org/doi/abs/10.2514/6.2012-1864.

- Hilburger MW, Nemeth MP. Buckling and Failure of Compression-loaded Composite Cylindrical Shells with Reinforced Cutouts. 46th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference Austin, Texas. 2005.

- Arbocz J, Hilburger MW. Toward a Probabilistic Preliminary Design Criterion for Buckling Critical Composite Shells. AIAA Journal [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2014 Feb 5];43:1823–7. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Tafreshi A. Buckling and post-buckling analysis of composite cylindrical shells with cutouts subjected to internal pressure and axial compression loads. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping [Internet]. 2002;79:351–9. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0308016102000261 . [CrossRef]

- Bisagni C. Numerical analysis and experimental correlation of composite shell buckling and post-buckling. Compos B Eng [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2014 Mar 11];31:655–67. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359836800000317 . [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Piening HR, Farshad M, Geier B, Zimmermann R. Buckling loads of CFRP composite cylinders under combined axial and torsion loading – experiments and computations. Compos Struct [Internet]. 2001;53:427–35. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0263822301000538 . [CrossRef]

- Tafreshi A, Bailey CG. Instability of imperfect composite cylindrical shells under combined loading. Compos Struct [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2013 Dec 18];80:49–64. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0263822306000900 . [CrossRef]

- Almroth BO, Holmes AMC. Buckling of shells with cutouts, experiment and analysis. Int J Solids Struct [Internet]. 1972 [cited 2014 May 7];8:1057–71. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0020768372900704.

- Toda S. Buckling of cylinders with Cutouts Under Axial Compression. 1983. [CrossRef]

- Ambur DR, Dávila CG, Hilburger MW. Progressive Failure Studies of Composite Panels with and without Cutouts. 2001;

- Taheri-Behrooz F, Omidi M, Shokrieh MM. Experimental and numerical investigation of buckling behavior of composite cylinders with cutout. Thin-Walled Structures [Internet]. 2017;116:136–44. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Ghazijahani TG, Jiao H, Holloway D. Structural behavior of shells with different cutouts under compression: An experimental study. J Constr Steel Res [Internet]. 2015;105:129–37. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Hilburger MW. Buckling and Failure of Compression-loaded Composite Laminated Shells with Cutouts. 1998;1–13.

- Ismail MS, Baharudin BTHT, Yahya SA, Kahar HA. Finite Element Analysis of Composite Cylinder with Centre Cutout under Axial Load and Internal Pressure. Adv Mat Res [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2024 Sep 23];701:425–9. Available from: https://www.scientific.net/AMR.701.425 . [CrossRef]

- Ismail MS, Baharudin BTHT, Yahya SA, Kahar HA. Finite Element Analysis of Composite Cylinder with Centre Cutout under Axial Load and Internal Pressure. Adv Mat Res [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 Dec 18];701:425–9. Available from: http://www.scientific.net/AMR.701.425 . [CrossRef]

- Shen H, Zhou P, Chen T. Postbuckling Analysis of Stiffened Cylindrical Shells under Combined External Pressure and Axial Compression. Thin-Walled Structures [Internet]. 1993 [cited 2017 Feb 20];15:43–63. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/026382319390012Y . [CrossRef]

- Shen H, Zhou P, Chen T. Buckling And Postbuckling of Stiffened Cylindrical Shells Under Axial Compression. Appl Math Mech. 1991;12:1195–207.

- Wang B, Du K, Hao P, Zhou C, Tian K, Xu S, et al. Numerically and experimentally predicted knockdown factors for stiffened shells under axial compression. Thin-Walled Structures [Internet]. 2016;109:13–24. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Ismail MS, Ifayefunmi O, Fadzullah SHSM. The role of stiffener in resisting buckling of externally pressurized cone-cylinder intersection. Proceedings of Mechanical Engineering Research Day. 2018;55–6.

- Ismail MS, Nordin FN, Hieu Le C, Nguyen HQ, Mahmud J. The implementation of the single perturbation load approach to axially-compressed stiffened-stringer cylinder. Springer Proceedings in Materials. 2024;40:13–23.

- Rafiee M, Hejazi M, Amoushahi H. Buckling response of composite cylindrical shells with various stiffener layouts under uniaxial compressive loading. Structures. 2021;33:4514–37. [CrossRef]

- Block DL. Influence of discrete ring stiffeners and prebuckling deformation on the buckling of eccentrically stiffened orthotropic cylinders. NASA TN D-4283, Washington, D.C.; 1968.

- Wang B, Tian K, Hao P, Zheng Y, Ma Y, Wang J. Numerical-based smeared stiffener method for global buckling analysis of grid-stiffened composite cylindrical shells. Compos Struct [Internet]. 2016;152:807–15. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Ismail MS, Purbolaksono J. Analysis using finite element method of the buckling characteristics of stiffened cylindrical shells. Australian Journal of Structural Engineering. 2024; [CrossRef]

- Dinkler D, Knoke O. Elasto-plastic limit loads of cylinder-cone configurations. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics. 2003;41:443–57.

- DIN 18 800. Structural steelwork Analysis of safety against buckling of linear members and frames. Berlin: Deutsche Norm; 1990.

- Zingoni A. Discontinuity effects at cone-cone axisymmetric shell junctions. Thin-Walled Structures. 2002;40:877–91. [CrossRef]

- Zingoni A, Mokhothu B, Enoma N. A theoretical formulation for the stress analysis of multi-segmented spherical shells for high-volume liquid containment. Eng Struct. 2015;87:21–31. [CrossRef]

- Flores FG, Godoy LA. Post-buckling of elastic cone-cylinder and sphere-cylinder complex shells. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping. 1991;45:237–58. [CrossRef]

- Teng JG. Elastic buckling of cone-cylinder intersection under localized circumferential compression. Eng Struct. 1996;18:41–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Teng JG. A stability design proposal for cone-cylinder intersections under internal pressure. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping. 2003;80:297–309. [CrossRef]

| Categories of failure | Comments |

| Material | Inappropriate choice of material; flaws in the material. |

| Design | Flawed design information; imprecise design techniques; and insufficient shop testing. |

| Fabrication | Inadequate quality control; inappropriate or lacking fabrication techniques such as welding; heat treatment or forming processes methods. |

| Service | Modifications to service conditions by the user; lack of experience among operations or maintenance staff; unexpected situations. Certain services that necessitate particular care in terms of material selection, design specifics, and manufacturing techniques include the followings:

|

| Codes | Imperfection tolerance | |

| Ring-stiffened | Stringer-stiffened | |

| DnV [94] | - | |

| ECCS [49] | , | |

| API [51] | ||

| Models | Features and recommended application range |

| ABS [125]; DNV [126] |

|

| RS [127]; Galletly and Blachut [128] |

|

| NASA [122]; Wagner et al. [129]; Evkin [130] |

|

| Area to explore | Proposed Improvement/Control |

| Experimental |

|

| Numerical (FEM) |

|

| Analytical |

|

| Controls variables |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).