Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Principles of Hysteresis Effect in EWDs

2. Materials and Methods

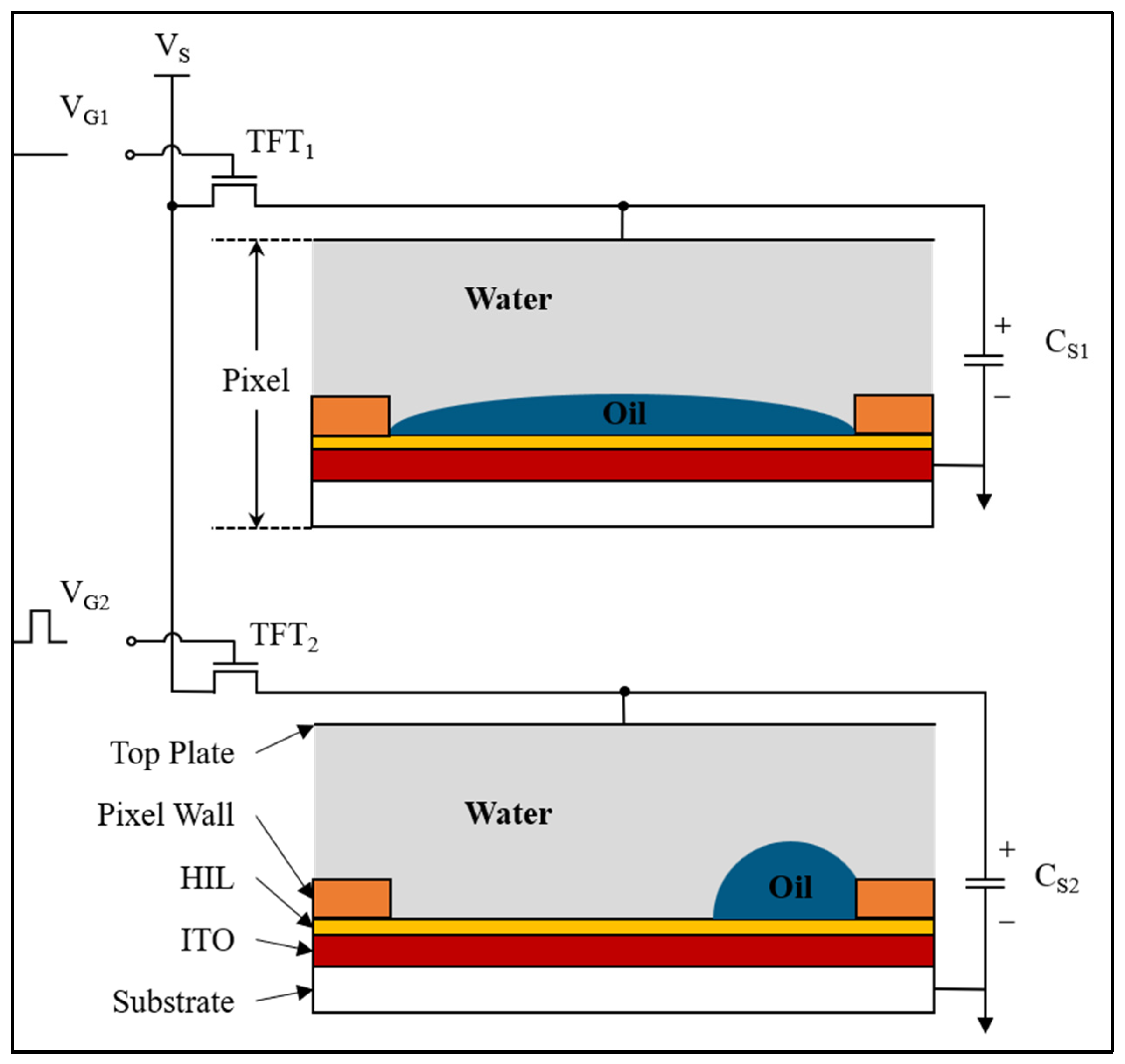

2.1. Driving Principle of EWDs

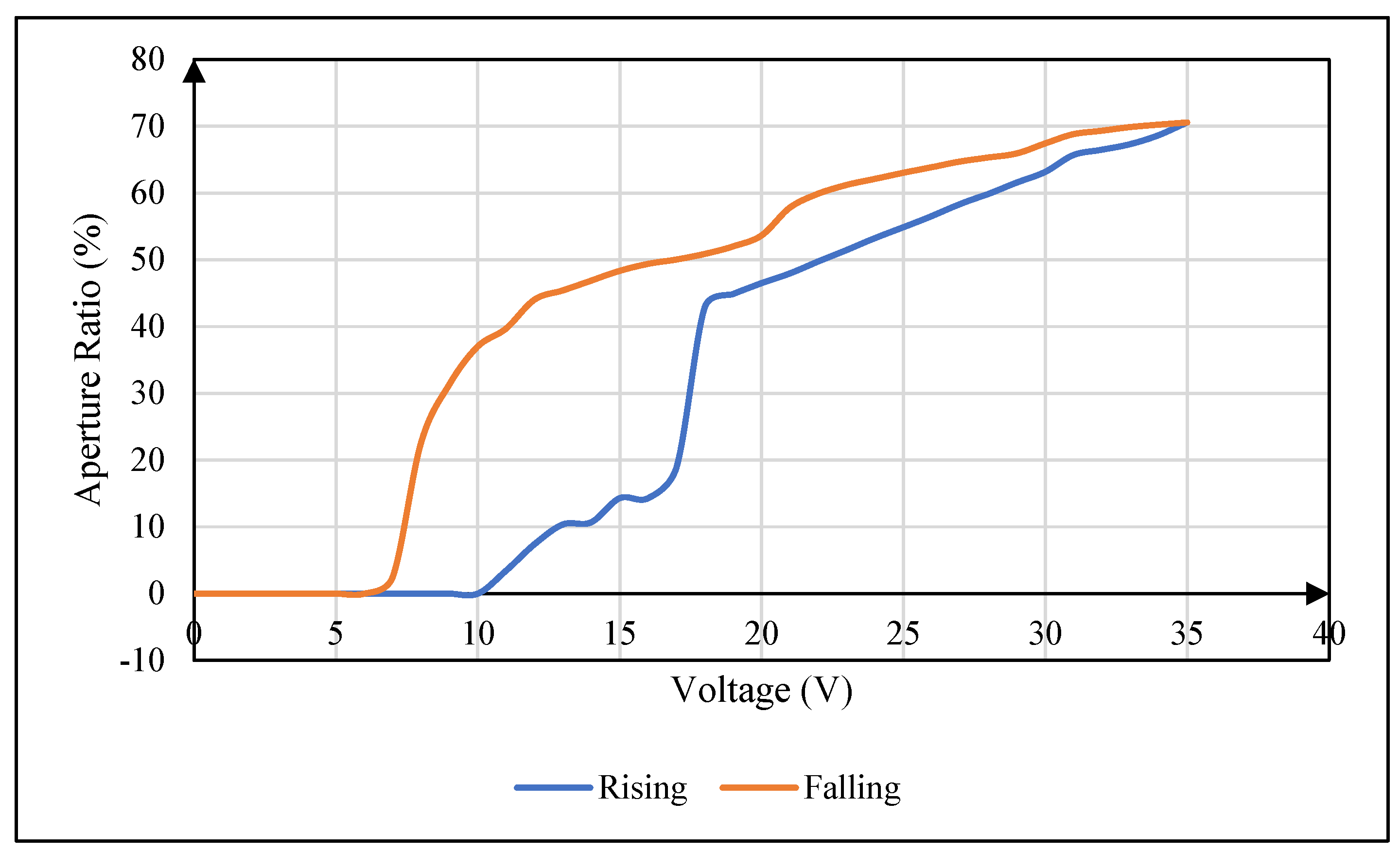

2.2. Hysteresis Effect of EWDs

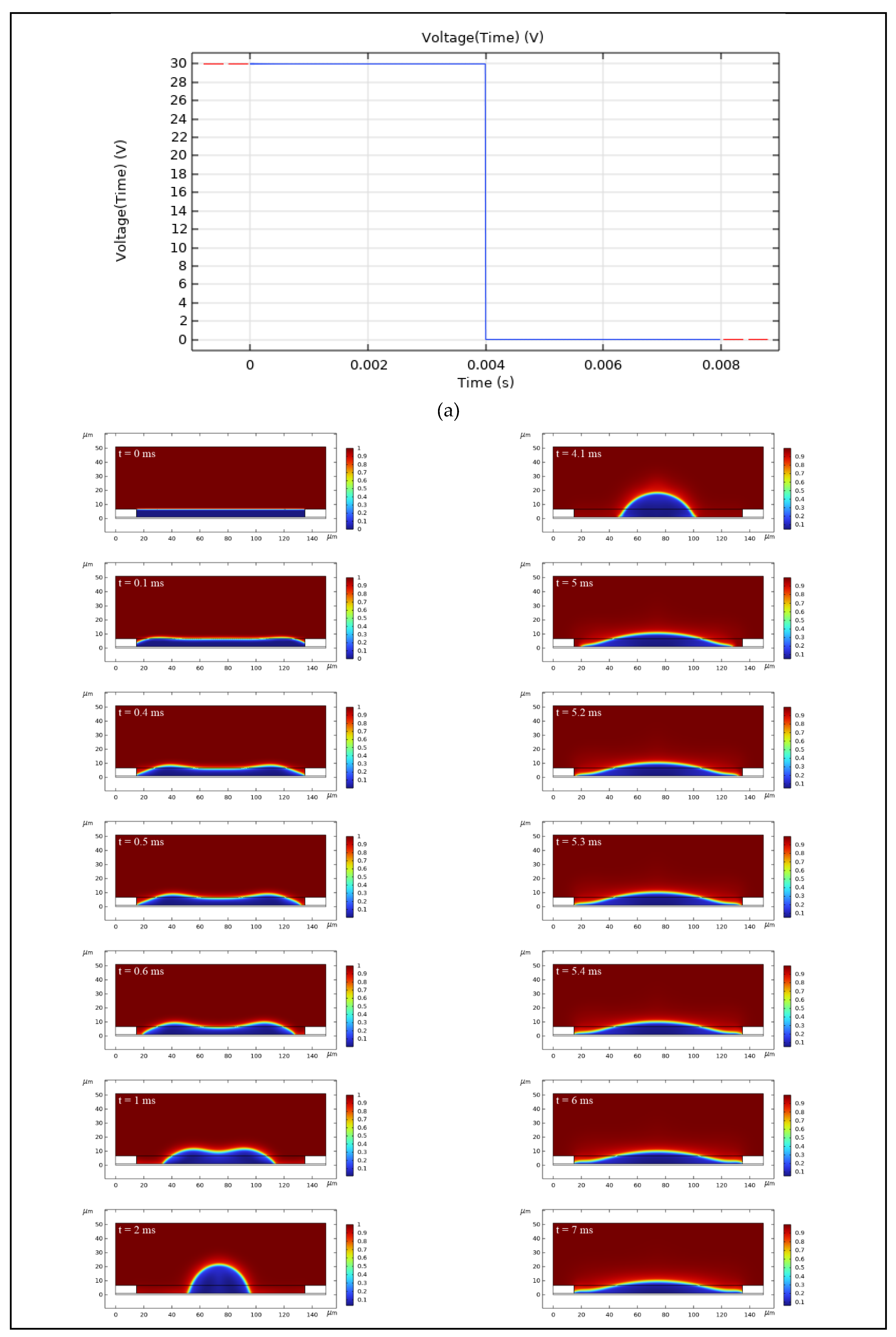

3. Numerical Methodology

3.1. Governing Equations

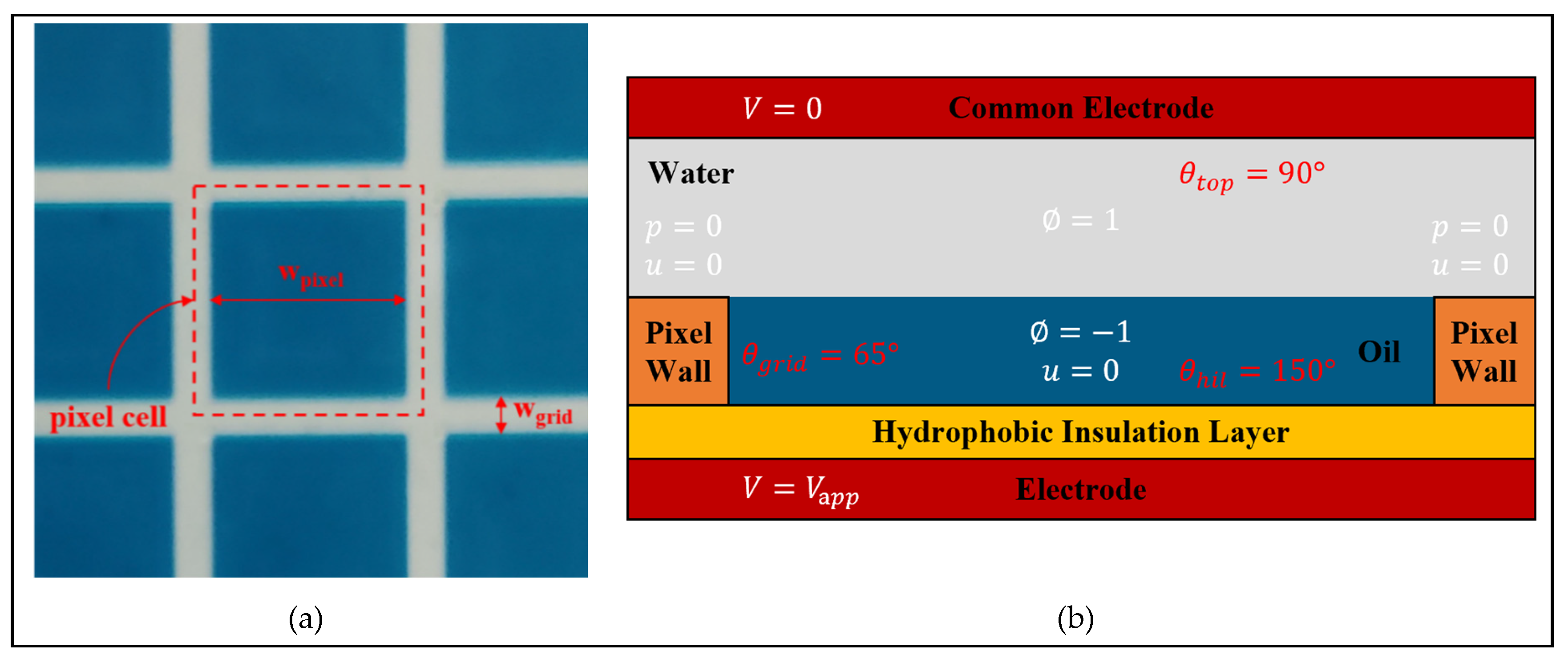

3.2. Boundary Conditions

| Parameters | Quantity | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | density of oil | 880 | kg/m³ | |

| density of water | 998 | kg/m³ | ||

| dynamic viscosity of oil | 0.002 | Pa·s | ||

| dynamic viscosity of water | 0.001 | Pa·s | ||

| dielectric constant of oil | 2.2 | 1 | ||

| dielectric constant of water | 80 | 1 | ||

| dielectric constant of hydrophobic insulating layer | 1.95 | 1 | ||

| dielectric constant of pixel wall | 3.28 | 1 | ||

| Geometric | width of pixel cell | 150 | μm | |

| height of pixel wall | 5.6 | μm | ||

| width of pixel wall | 15 | μm | ||

| thickness of hydrophobic insulating layer | 1 | μm | ||

| thickness of oil | 5.6 | μm | ||

| Interfacial | surface tension of oil and water | 0.015 | N/m | |

| contact angle of pixel wall | 65 | deg | ||

| contact angle of hydrophobic insulating layer | 150 | deg | ||

| contact angle of top plate | 90 | deg |

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

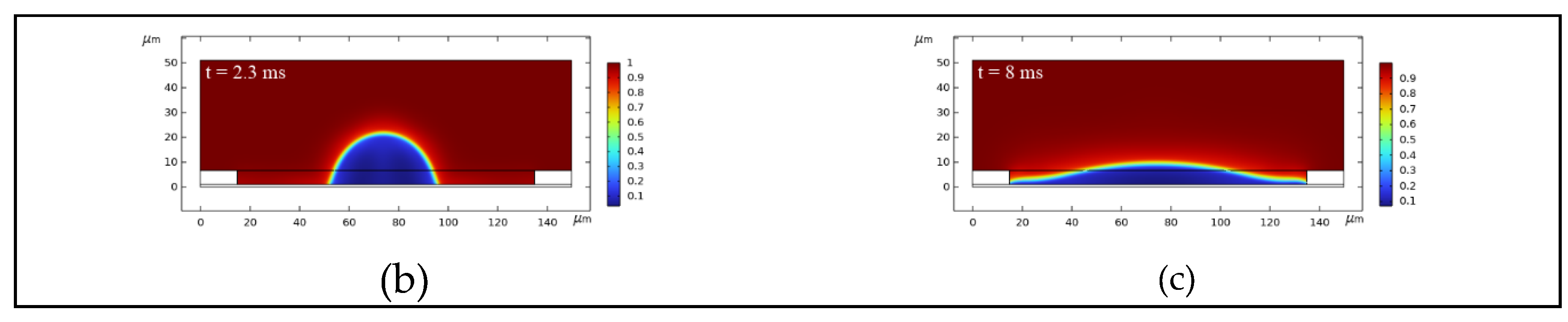

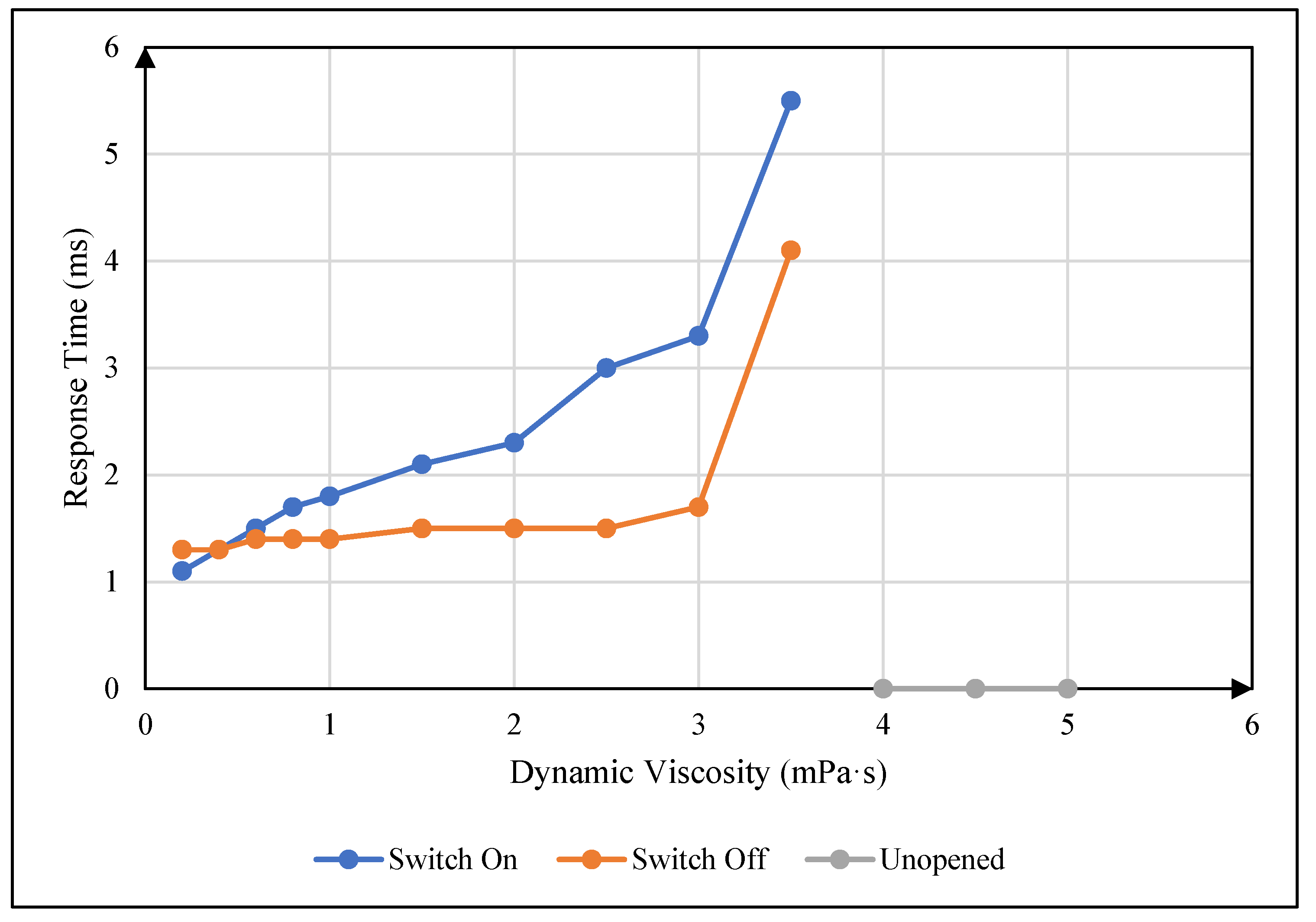

4.1. Influence of Oil Viscosity on Response Time

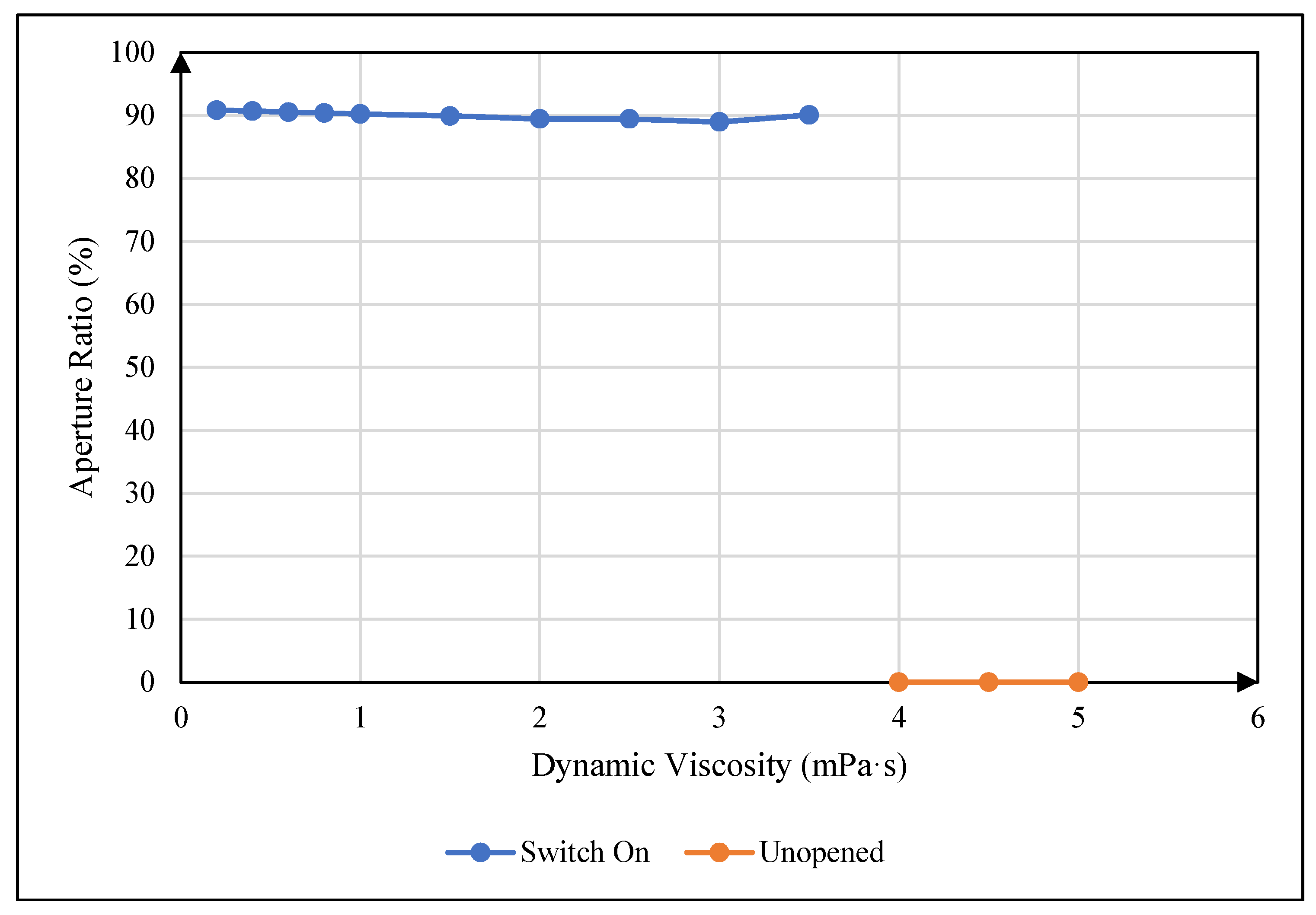

4.2. Influence of Oil Viscosity on Maximum Aperture Ratio

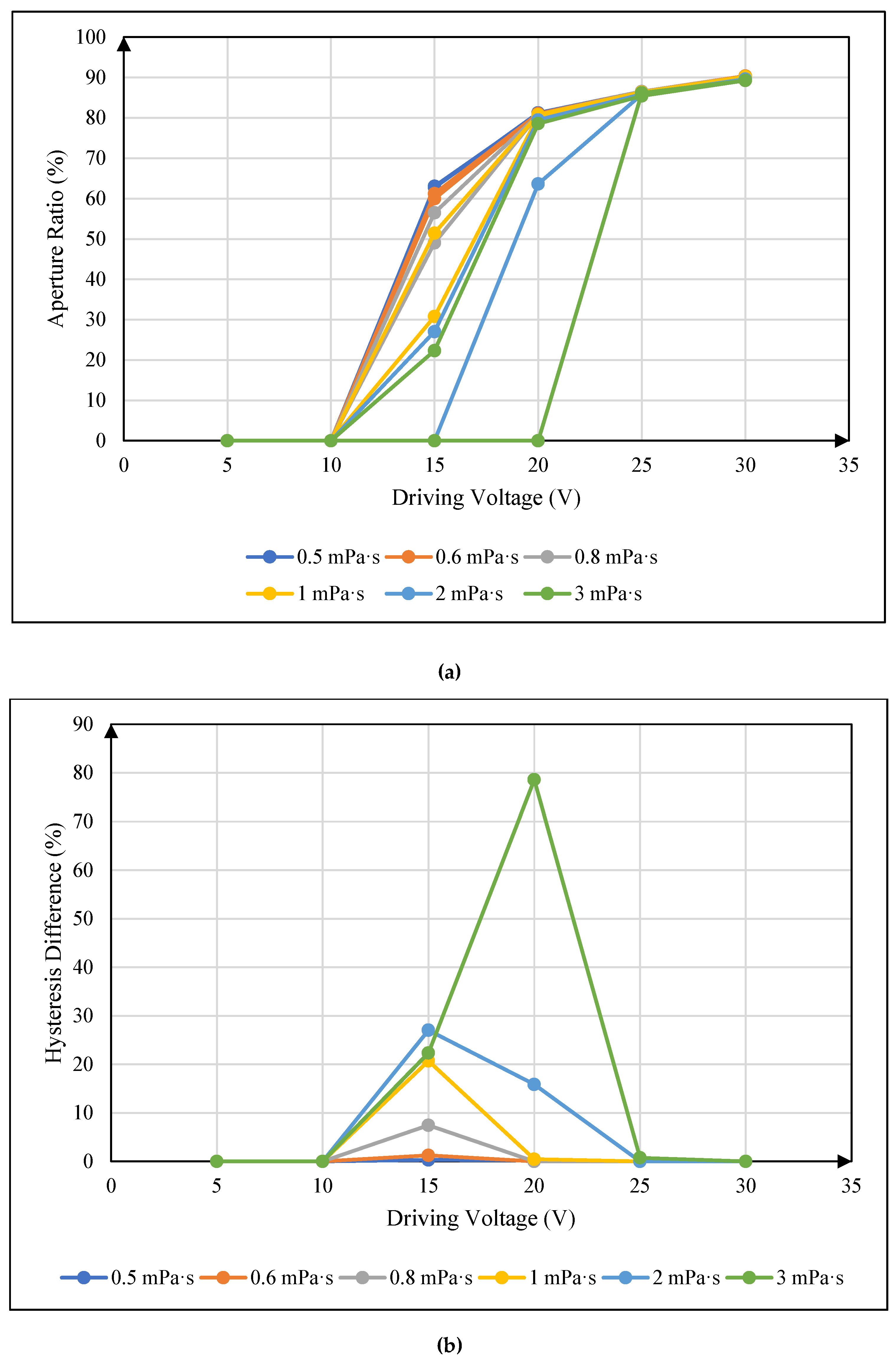

4.3. Influence of Oil Viscosity on Hysteresis Effect

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayes, R.A.; Feenstra, B.J. Video-speed electronic paper based on electrowetting. Nature 2003, 425, 383–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, H.; Wheeler, A.R.; Garrell, R.L.; Loo, J.A.; Kim, C.J. An integrated digital microfluidic chip for multiplexed proteomic sample preparation and analysis by MALDI-MS. Lab on a Chip 2006, 6, 1213–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, B.; Peseux, J. Variable focal lens controlled by an external voltage: An application of electrowetting. The European Physical Journal E 2000, 3, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupenkin, T.; Taylor, J.A. Reverse electrowetting as a new approach to high-power energy harvesting. Nature communications 2011, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Lai, S.; Liu, L.; He, W.; Yi, Z. Driving Waveform Design with Rising Gradient and Sawtooth Wave of Electrowetting Displays for Ultra-Low Power Consumption. Micromachines 2020, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Huang, Z.; Lai, S.; He, W.; Wang, L.; Chi, F.; Zhang, C.; Shui, L.; Zhou, G. Driving Waveform Design of Electrowetting Displays Based on an Exponential Function for a Stable Grayscale and a Short Driving Time. Micromachines 2020, 11, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.S.; Kuo, S.W.; Tsai, Y.H.; Cheng, P.P.; Chen, J.L.; Lan, K.W.; Cheng, W.Y. The Structure and Manufacturing Process of Large Area Transparent Electrowetting Display. SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers 2012, 43, 850–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Heikenfeld, J. Observation and optical implications of oil dewetting patterns in electrowetting displays. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2008, 18, 025027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Feng, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Lin, Y.; He, W.; Zhou, G. Aperture Ratio Improvement by Optimizing the Voltage Slope and Reverse Pulse in the Driving Waveform for Electrowetting Displays. Micromachines 2019, 10, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, Dijk.R.; Feenstra, B.J.; Hayes, R.A.; Camps, I.G.J.; Boom, R.G.H.; Wagemans, M.M.H.; Feil, H. Gray scales for video applications on electrowetting displays. SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers 2006, 37, 1926–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, A.; Vermeulen, P.; Figura, D.; Spreafico, M.; Meeusen, J.A.; Hampton, M.W.; Novoselov, P. Improved Oil Motion Control and Hysteresis-Free Pixel Switching of Electrowetting Displays. In SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers 2012, 42, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fang, H. Hysteresis and saturation of contact angle in electrowetting on a dielectric simulated by the lattice Boltzmann method. Journal of adhesion science and technology 2012, 26, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.; Qi-Chao, L.; Ping, W.; Zhong-Cheng, L. Contact angle hysteresis in electrowetting on dielectric. Chinese Physics B 2015, 24, 086801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Peng, R.; He, M. Effect of oil liquid viscosity on hysteresis in double-liquid variable-focus lens based on electrowetting. In International Conference on Optical and Photonics Engineering 2017, 10250, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Tang, B.; Groenewold, J.; Li, F.; Yue, Q.; Zhou, R.; Zhou, G. Oil motion control by an extra pinning structure in electro-fluidic display. Sensors 2018, 18, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Tang, B.; Henzen, A.; Zhou, G. Photolithography fabricated spacer arrays offering mechanical strengthening and oil motion control in electrowetting displays. Sensors 2020, 20, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Bai, P.F.; Hayes, R.A.; Shui, L.L.; Jin, M.L.; Tang, B.; Zhou, G.F. Novel driving methods for manipulating oil motion in electrofluidic display pixels. Journal of Display Technology 2016, 12, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Henzen, A. A Multi Waveform Adaptive Driving Scheme for Reducing Hysteresis Effect of Electrowetting Displays. Frontiers in Physics 2020, 8, 618811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eral, H.B.; ’t Mannetje, D.J.C.M.; Oh, J.M. Contact angle hysteresis: a review of fundamentals and applications. Colloid and polymer science 2013, 291, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Deng, Y.; Xu, B.; Henzen, A.; Hayes, R.; Tang, B.; Zhou, G. Asymmetrical Electrowetting on Dielectrics Induced by Charge Transfer through an Oil/Water Interface. Langmuir 2018, 34, 11943–11951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.H.; Pak, J.J. Effect of contact angle hysteresis on electrowetting threshold for droplet transport. Journal of adhesion science and technology 2012, 26, 2105–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, A.; Sedev, R.; Ralston, J. Contact angle saturation in electrowetting. The journal of physical chemistry B 2005, 109, 6268–6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arzpeyma, A.; Bhaseen, S.; Dolatabadi, A.; Wood-Adams, P. A coupled electro-hydrodynamic numerical modeling of droplet actuation by electrowetting. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2008, 323, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, W.L.; Lin, C.H.; Lo, K.L.; Lee, K.C.; Cheng, W.Y.; Chen, K.C. 3D electrohydrodynamic simulation of electrowetting displays. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2014, 24, 125024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkiv, V.; Yarin, AL.; Mashayek, F. Modeling of Droplet Impact onto Polarized and Nonpolarized Dielectric Surfaces. Langmuir 2018, 34, 10169–10180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.P.; Yao, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Li, A.F.; Shams, B. Investigation of the Dynamic Contact Angle Using a Direct Numerical Simulation Method. Langmuir 2016, 32, 11736–11744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Tang, B.; Dong, B.; Li, H.; Zhou, R.; Guo, Y.; Dou, Y.; Deng, Y.; Groenewold, J.; Henzen, A.V.; Zhou, G. Electrowetting on dielectric: experimental and model study of oil conductivity on rupture voltage. Journal of Physics D Applied Physics 2018, 51, 195102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.T.; Feng, J.J.; Liu, C.; Shen, J. A diffuse-interface method for simulating two-phase flows of complex fluids. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2004, 515, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, J.W.; Hilliard, J.E. Free Energy of a Nonuniform System. I. Interfacial Free Energy. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1958, 28, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhuang, L.; Bai, P.; Tang, B.; Henzen, A.; Zhou, G. Modeling of Oil/Water Interfacial Dynamics in Three-Dimensional Bistable Electrowetting Display Pixels. ACS omega 2020, 5, 5326–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).