1. Introduction

We live in a world of constant change, both economically and socially, and this requires continuous adaptation. The same applies to graduates who must adapt to the demands of a constantly changing labor market, but also to higher education institutions that must adapt teaching strategies and curricula to provide a skilled workforce. A skilled workforce and close collaboration between the business environment and higher education institutions are key factors in the sustainable development of a country.

1.1. The Role of Education in Sustainable Development

Sustainability implies economic development, but also development and environmental protection (1=Gavriluță, 2022), and the basis for a sustainable development is in the human capital investment, through education and training (2=Diaconu, 2014). In the globalization context and in the context of an economy of uncertainty (3=Altig et al 2022), the human responsibility should be the basis for the global sustainable development and should be at the center of the activities of higher education institutions (1=Gavriluță, 2022). A society that wants to develop sustainably must invest in research, development and innovation (4=Sîrbu et all 2015), which suggests that Romania's economic prosperity and the country's long-term sustainability are influenced above all by education (5=Ibinceanu, Cristache, Dobrea, Florescu 2021).

Also, in the context of sustainable development, Romania must continue to make progress in order to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, and some progress must be clearly recorded, precisely in the field of education. The poor quality of research and the lack of continued investment are an obstacle to achieving Romania’s sustainable goals (6=Romania country report 2023, p 5). In the case of Romania, to face those challenges in achieving the sustainable goals, the romanian workforce should be competitive, responsible and qualified in their field of activity (4=Sîrbu, 2015).

Romania's sustainable development must include education in its plan, and especially the collaboration between the education system and the business environment, to train competent graduates capable of adapting quickly to the constantly changing demands of the labor market. In Romania, it is necessary to create a closer connection between the labor market and the education system in order to improve the training of human resources (7=Șerban, 2012).

Romania presents a high risk of poverty and inequality (6= Romania Country report, 2023, p 60), with 3 of the regions in Romania being considered among the 20 poorest regions in the European Union (8=National Institute of Statistics, Statistical Yearbook Romania 2016), and at the same time among the EU countries with a high degree of material deprivation among young people (1=Gavriluță, 2022). The lack of human resource training can lead to increased unemployment, and excessive unemployment can implicitly lead to the degradation of living conditions. Thus, education is a key factor that can lead to the reduction of unemployment and fight against the eradication of poverty, having the potential to reduce cleavages in society (5=Ibinceanu, Cristache, Dobrea, Florescu 2021).

Although education should be one of the country's priorities and one of the necessary objectives for sustainable development, the quality level of the higher education system in Romania is declining (9=Stanciu, Banciu 2012). The causes for the decline in the credibility and competitiveness of universities are the following: the rapid increase in the number of higher education institutions, both public and private, as well as the emergence of specialization areas that have no correspondence on the labor market or the lack of funding (10=Vlăsceanu, 2007). This aspect is also highlighted by institutional reports in Romania indicating that the country is on the verge of having increasingly less efficient higher education institutions, an inflation of diplomas and a decrease in the skills of graduates, which leads to a decrease in the competitiveness of the labor force. At the same time, universities must struggle with the lack of resources, especially financial ones, to increase the quality of the education system (10=Vlăsceanu, 2010). This is also reflected in the fact that Romania does not have any universities in the Shanghai ranking. The low efficiency of the Romanian education system is also reflected in the gap between what educational institutions offer and the needs of the business environment (6=Romania Country Report, p 62, 9=Stanciu, Banciu 2012). From this point of view, it can be said that higher education institutions in Romania need to become more involved in analyzing the needs of employers and collaborate more closely with them (9=Stanciu, Banciu 2012).

Romania, like any other country, needs a skilled workforce that can adapt to changes in the labor market (2=Diaconu, 2014). The Romanian education system must aim to develop those skills that facilitate integration into the labor market among all citizens, regardless of age, gender, background or ethnicity (7=Șerban, 2012). Studies show that candidates' diplomas and studies are important for employers, but nevertheless graduates possess more theoretical knowledge than practical knowledge and skills that would help them in the labor market (9=Stanciu, Banciu, 2012). In Romania, the level of digital skills and the lack of participation in continuous professional training influence the degree of employment of people (6=Romania Country report 2023). Therefore, it can be said that there is pressure on the Romanian education system to train well-prepared graduates (11=Barbu, Diaconescu, Stepan, Popescu, 2020).

Many Romanian students lack basic skills (6=Romania country report p11) and specific skills are missing across all professions (6=Romania Country report, p62) and Romania is among the worst performers (12=European skills Index CEDEFOP). Moreover, the skills of graduates from VET and higher education are not sufficiently in accordance with the labor market needs (13=OECD). In Romania, the rate of young people neither in employment, nor in education or training is among the highest in the EU, at 19.8% in 2022, while the average in Europe was 11.7% in decrease with 1.4% from 2021 (14= Eurostat, 2023).

1.2. The Skills, Competences, Knowledge and Personal Traits in Sport Industry

The sports industry plays an important role in the global economy, including in the Romanian economy, and analyzing the degree of student employment and identifying the skills that need to be developed must be part of Romania's public policies for sustainable development (5=Ibinceanu, Cristache, Dobrea, Florescu, 2021). The development of the sports industry in Romania could bring numerous economic and social advantages, so training graduates who possess the skills necessary for rapid adaptation to the labor market is an elementary factor.

The sports industry is in continuous development, a fact anticipated since 2010, (15=Shilbury and Kellet), when they specified that the sports industry will develop rapidly in the coming years. Thus, in the last 20 years alone, the sports economy has recorded an annual growth rate twice as high as that of the world GDP (16=Aymar. Desbordes, Hautebois 2019), and in 2020, the global sports market is estimated at over 800 billion euros (17=Desbordes, Hautebois, 2020). This development entails the creation of new jobs and implicitly the training of skills that correspond to the demands of the labor market, for example, sport an unprecedented demand for university education (18=McCrae; Costa, 2005; 19=Shilbury et al 2017). However, working in sport industry offer opportunities that are challenging, fun and rewarding, excellent opportunities for rapid advancement (15=Shilbury, Kellet 2010).

At the same time, the sports industry is different from other industries. The sport industry is not managed as other businesses, even though sport organizations operate in a very similar manner to other organizations, the sport industry has several unique attributes that influence how management theories, principles and strategies are applied by sport managers (20=Hoye et al 2015).

Meanwhile, for students, choosing a certain type of training course will influence the nature of jobs held by the graduate (21=Pierre, Collinet, Schut 2022). In the past two decades, many students have chosen sport management as a major opportunity to follow their passion for the sport industry (22=Cohen, Levine, 2016; 23=Eagleman, McNary, 2010; ;). Nevertheless, (24=Dharamsi Karim, 2017) state that although although it is already difficult as it is for students fo find and keep a job in the domain they have been training for, it seems to be even more difficult in the sport industry (25=De Schepper, Sotiriadou 2018; 26=Keiper, Sieszputowski, Morgan, Mackey, 2019; 27=Todd, Magnusen, Andrew, Lachowetz, 2014). Furthermore, students are reporting a lack of career awareness, industry understanding and understanding between social norms values and behaviors within an organization (28 = Amis, Silk 2005; 29 = Frisby, 1992) suggesting that higher education institutions are not doing enough to provide opportunities to develop the essential skills demanded by the industry (30 = Kavanagh, Drennan 2008; 31 = Ipsos-Eureka Social Research Institute 2010).

At the end of the 20th century, authors already stated that sport and recreation organizations should enhance service quality (32 = Chelladurai, Chang 2000; 33 = Howat, Crilley, Absher, Milne 1996). As sport and recreation business is growing, it is needed a continuous support by satisfied customers (34 = Tsitskari, 2017 et all). So, to satisfy the customers, most sports and recreation services demand multiple roles from their employees, roles which demand a variety of personal and interpersonal competencies (34 = Tsitskari et al, 2017). In that way, we can consider that it is mandatory to underline which are the needed skills, competencies and attitudes for a sport graduate student (34 = Tsitskari et al 2017).

Higher education institutions everywhere are under pressure to produce graduates who contribute to the sustainability of economic growth and development of countries and regions (35 = Small, Shacklock, & Marchant, 2018), and the pressure is even greater in situations of economic recession such as the 2008 recession or health crisis, as was the case with the Covid 19 pandemic (36=Baciu, 2022). Developing the skills required by employers could facilitate students' transition from the economic to the business environment (37 = Mackieh, Dlhin 2019). As previously stated, the sport industry is different, and a student at a physical education faculty needs to acquire different competencies and skills-based knowledge for working in the sport industry (38=Molina-Garcia et al 2024). However, the formation of the necessary competencies is a serious problem that current Romanian society is facing. The lack of skills to facilitate the rapid integration of graduates into the labor market is one of the problems faced by employers (39=Donald, Ashleigh, & Baruch 2018). The skills required on the labor market may differ depending on the job required, even within the same sector, could depend on the geographical region. However, it can be argued that regardless of the job, there are several skills that can be required. Among them we can list, for example, the ability to communicate effectively which is needed in almost all industries (40=Baker et al, 2017). The goal of higher education institutions should be to prepare the students for the challenges they will face in their professional careers and to develop the desire for lifelong learning and adaptation in an ever-changing world (38=Molina-Garcia et al 2024).

One of the reasons why competencies could be difficult to form is the fact that competence is a complex concept which is difficult to define and very difficult to measure (41=Levett-Jones, 2011, p64). Competencies could be described as personal characteristics of a human being, individual attributes such as knowledge, skills and attitudes, that facilitate the achievement of results or superior performance in a particular situation which results in overall job performance (42=Spencer, Spencer 1993; 43 = Coll, Zegwaard 2006, p31). Competencies are skills and abilities that allow an individual to perform desirably within the internal and external limitation of an organization in the exercise of their role and work tasks (44=Arbi, 2017). Moreover, Sider et al (45 = 2019) described competence as the ability to apply knowledge, skills, professional characteristics, experience and motivation to perform a type of work or task uniquely and efficiently. From another point of view, competence could be defined as the capacity to accomplish complex task successfully by the mobilization of mental prerequisites among which are cognitive and practical skills, knowledge, motivation, value, ethics, attitudes emotions and social behaviors (46=Rychen, Salganik 2003, p83).

Also, in the specialized literature, a distinction is made between hard skills, soft skills and personal traits attributes. Hard skills refer to those technical abilities that are acquired through practice, repetition and education. These have the gift of increasing productivity and efficiency in the workplace. On the other hand, soft skills are those non-technical abilities that target interpersonal abilities and that are applied to a variety of activities and tasks (47=Matteson, Anderson, Boyden, 2016). Among hard skills can be listed: technical abilities, abilities that involve identifying problems and solving them (42=Spencer, Spencer 1993) or the ability to make complex and creative judgments (43=Coll, Zegwaard 2006). The limit between these skills is not always obvious, for example, De Schepper (48= 2021) considers that critical reflection is a soft skill, which is especially necessary in the sports industry. Soft skills are a combination of the individual’s personality and contain interpersonal skills and organizational skills. Behavioral skills incorporate personal skills that relate to how individuals respond and handle various situations like managing relationships between people (49=Birkett, 1993). At the same time, these behavioral skills are primarily affective in nature, and they are an accumulation of innate characteristics, personal and interpersonal skills (43=Coll, Zegwaard 2006).

Some employers find that soft skills are more important than hard skills (50=Archer and Davison, 2008) and in industries like sports and hospitality, which involve frequent interaction with people, soft skills could be even more important (51=Crawford, Weber, Lee 2020; 52=Weber et al, 2013, 53=Griffith et al, 2017). By example, in these industries, soft skills like enthusiasm, leadership, curiosity, ethics tend to be more important than hard skills (34=Tsitskari et al 2017, 54=Sato et all, 2021). By example, curiosity consists of a positive attitude towards learning and self-development, associated with personal growth and self-competence (Dixson, 2020). Employees with strong curiosity can potentially generate long term impacts (55= Sato et al, 2021). Moreover, the employers do not hire candidates who do not possess soft skills (56=Gabor, Blaga, Matis 2019). Also, many recruiters when hiring also consider personal traits attributes, such as agreeableness and extroversion. These personality traits are stable over time, are harder to change and influence human behavior and actions (57=Matteson, Anderson, Boyden, 2016). On the other hand, hard skills can be learned and improved throughout life.

2. Methodology

The motivation for the research is represented by the desire to connect the educational system to the demands of the labor market, to help the professional insertion of students as well as to increase their professional satisfaction and to form human resources that will favor the sustainable development of Romania. The relevance of the study is represented by the fact that the socio-economic situation is constantly changing, and to integrate into the labor market and to have a salary that allows them to ensure a decent living, students need new skills. Such studies have not been conducted so far in Romania, and its implementation allows an analysis of the situation of graduates from the faculties of physical education and sports in Romania. Also, the research results could inspire the implementation of similar approaches in other countries, regions or industries, and could raise certain comparisons and debates.

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the extent to which the information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired by graduates of physical education and sports faculties during their years of study influence their income level, standard of living and job satisfaction. The paper also aims to compare students' perceptions of their skills and employers' perceptions of students' skills and to identify which skills students need to improve. To achieve this objective, we asked the following research questions:

1. To what extent do the information, skills, abilities and competences acquired by students during their years of study influence their income level, standard of living, job satisfaction and level of confidence in the workplace?

2. What is the self-perception of students regarding the information, skills, abilities and knowledge that students possess?

3. What is the perception of employers regarding the information, skills, abilities and knowledge that students possess?

4. To what extent are there differences between students' self-perception and employers' perception regarding the information, skills, abilities and knowledge that students possess?

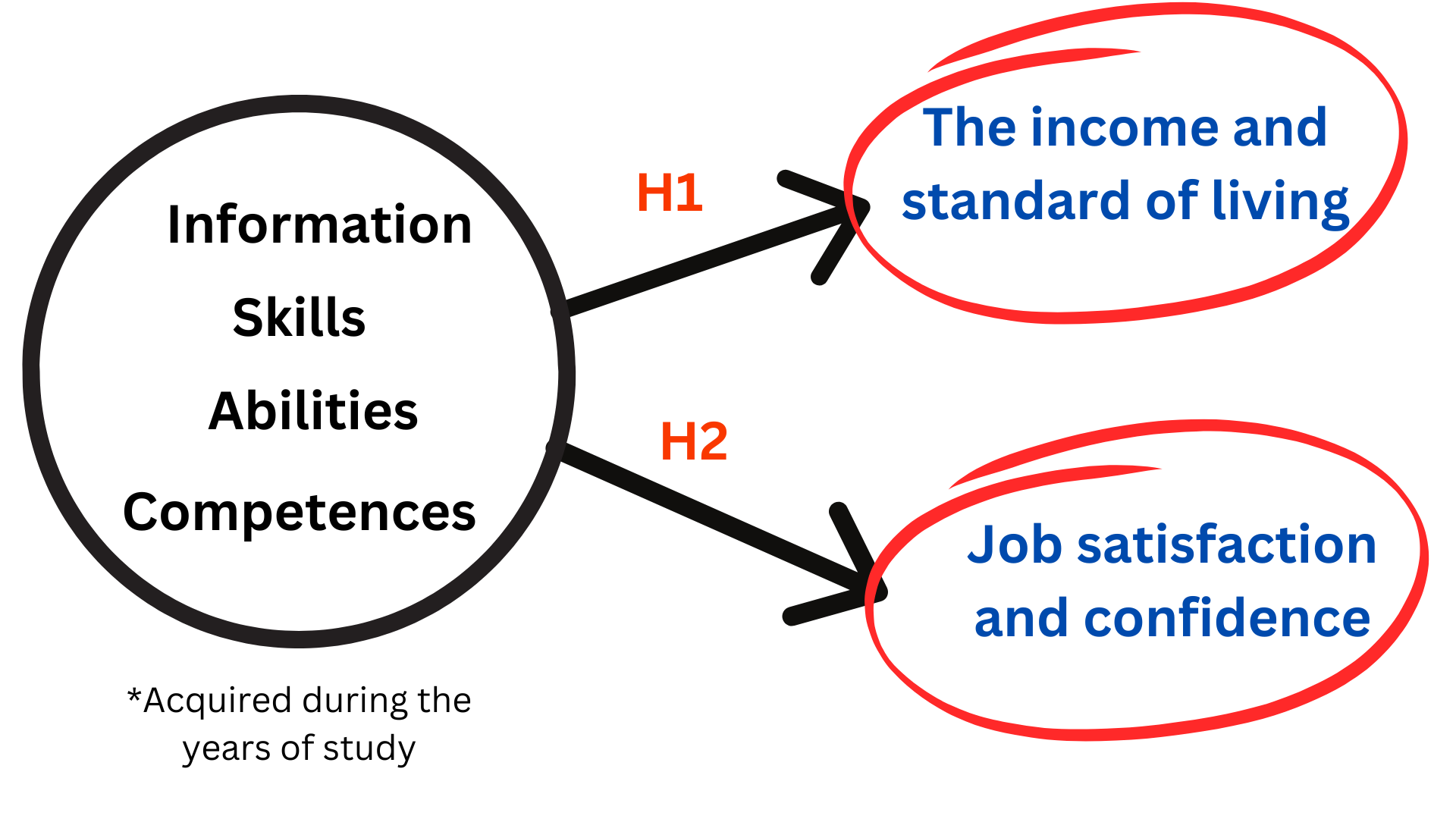

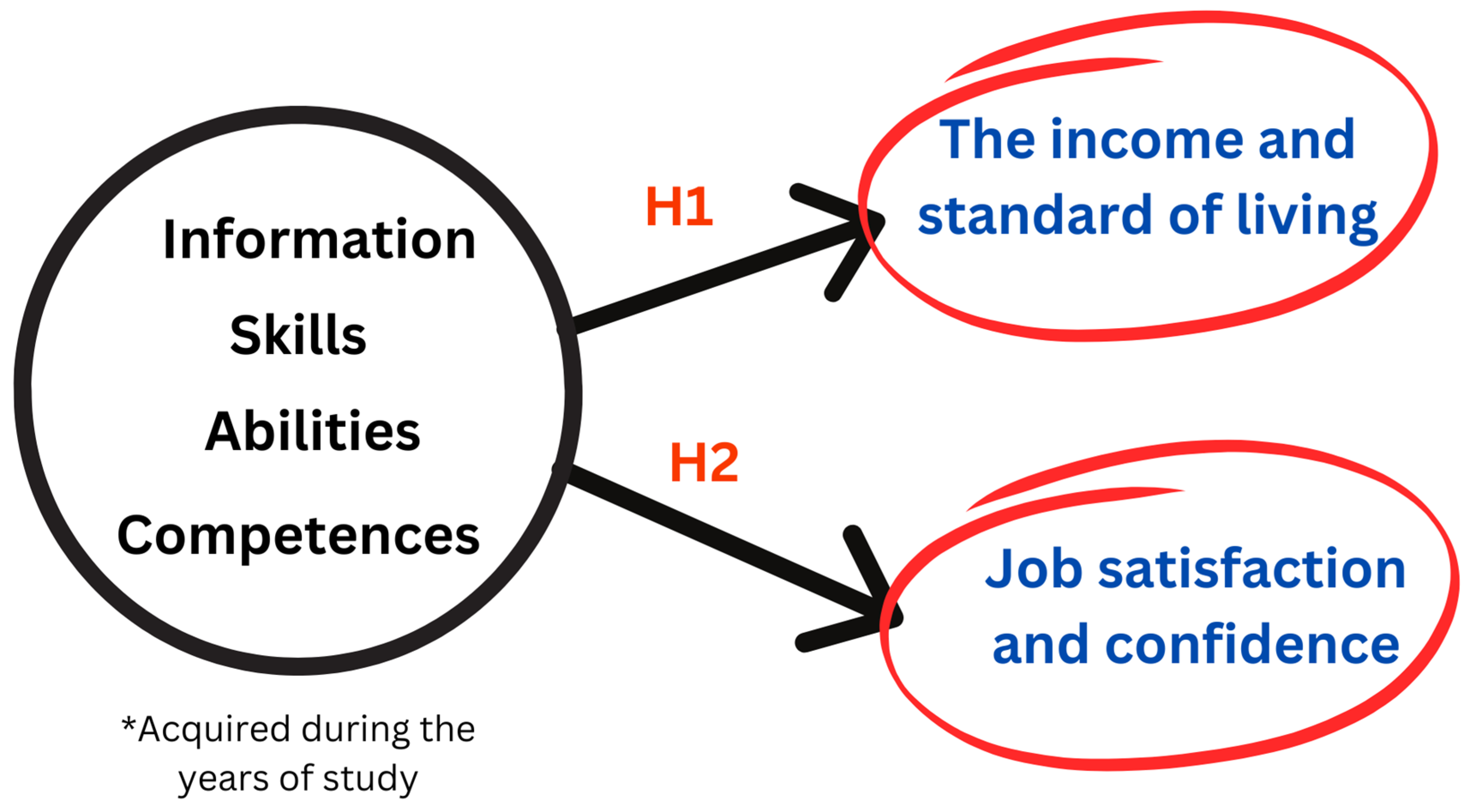

Thus, the hypotheses that were tested in this study are the following:

H1. The influence of skills, abilities, competencies and knowledge acquired during the years of study on the income and ensuring a decent living of graduates.

H2. The information, skills, abilities and competencies acquired during the years of study influence satisfaction and confidence at work.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model of the study. Source: authors contribution.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model of the study. Source: authors contribution.

To answer these questions, an online questionnaire was created through the Dragon Survey platform, which was distributed online and via a QR code to graduates from physical education and sports faculties in Romania. The questionnaire included socio-demographic questions, questions regarding the particularities of the workplace and questions regarding students' perception of the information, skills, abilities and competences they possess. It should also be noted that Dragon Survey allows responses from a single IP address, thus excluding the possibility that the same respondent could respond more than once. The questionnaire was first pre-tested with respondents from the target group, and then the questionnaire was distributed between 8 October and 18 November 2024 and reached 532 respondents, but only 333 answered all questions, so only these were considered for the statistical analysis of the data. The data were processed using SPSS 27 and subsequently analysed and interpreted. Also, to confront the students' self-perception of the information, skills, aptitudes and competences they possess, another questionnaire was conducted, also through Dragon Survey, and distributed online to 11 employers in the sports industry. This questionnaire was distributed in December 2024 and had an average response time of 35 minutes. The employers analysed the extent to which they consider that the students possess certain competences. Subsequently, the answers given by the students were compared with those provided by the employers.

2.1. Socio-Demographic Analysis

Table 1.

Analysis of the group of subjects from a socio-demographic point of view.

Table 1.

Analysis of the group of subjects from a socio-demographic point of view.

| Item |

Options |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Gender |

Male |

201 |

60.4% |

| Female |

132 |

39.6% |

| Age |

under 21 years |

13 |

3.9% |

| between 21-25 years |

174 |

52.3% |

| between 25-35 years |

62 |

18.6% |

| More than 35 years |

84 |

25.2% |

| Historical region |

Moldova |

107 |

32.1% |

| Muntenia |

113 |

33.9% |

| Dobrogea |

27 |

8.1% |

| Transilvania |

40 |

12.0% |

| Banat |

6 |

1.8% |

| Crișana |

5 |

1.5% |

| Oltenia |

25 |

7.5% |

| Republica Moldova |

6 |

1.8% |

| Ucraina |

4 |

1.2% |

| The environment of origin |

Urban |

229 |

68.8% |

| Rural |

104 |

31.2% |

| What is the last study program you graduated from? |

Bachelor |

277 |

83.2% |

| Master |

56 |

16.8% |

| In what year did you graduate from your last degree program? |

2020 |

45 |

13.5% |

| 2021 |

18 |

5.4% |

| 2022 |

22 |

6.6% |

| 2023 |

95 |

28.5% |

| 2024 |

153 |

45.9% |

| |

Total |

333 |

100.0% |

Regarding the socio-demographic analysis, it can be observed that just over 60% of the respondents are male, and almost 40% are female. This aspect indicates that the faculties of physical education and sports in Romania are masculinized, which also happens in other countries such as France (21=Pierre, Colinet, Schut 2022). Most of the respondents (52.3%) are between 21 and 25 years old, most of them having graduated from a bachelor's program in 2024 and enrolled in a master's program in the same year. Also, an important aspect is represented by the fact that 25.2% of the respondents are over 35 years old. This can be explained by several aspects. Firstly, many of the respondents, 60.7% to be exact, were competitive athletes for at least one season, and this may prevent them from starting their studies at a young age or continuing them. Also, the Romanian transport system does not facilitate the mobility of students so that they can move quickly from training to classes, and the distance between some cities can exceed 10 hours. Another reason why students start their studies at an older age is that some students who complete a bachelor's degree program do not immediately continue their studies with a master's degree program in the year they graduate. Also, some students decide to continuously train throughout their lives.

The respondents come from all historical regions of Romania, and this gives added relevance to the research results and denotes that the results can be extrapolated to the entire country. It is also important to emphasize that a percentage of the number of Romanian students at the faculties of physical education and sports come from Romania's neighbouring countries. 1.8% of the respondents come from the Republic of Moldova, and 1.2% come from Ukraine, countries where there are Romanian speakers, which facilitates their integration and adaptation in higher education institutions. Many of the Moldovan or Ukrainian students are found in university centres close to the border, such as those in Galați, Iași or Suceava. At the same time, in the current geopolitical context (the war in Ukraine and the accession of the Republic of Moldova to the European Union) and combined with the desire of a significant percentage of young Romanians to emigrate, the percentage of Moldovan and Ukrainian students is expected to increase in the coming period, which will entail changes in both the socio-demographic environment and the labour market. 68.8% of respondents come from urban areas, while 31.2% come from rural areas. Unfortunately, a significant percentage of high school graduates from rural areas decide not to continue their university studies. Among the reasons would be the desire to have an income and the fact that the economic situation does not allow them to continue their studies. At the same time, it should be noted that all respondents graduated after 2020, the idea of the study being precisely to analyse the skills, competencies and aptitudes of graduates from the last 5 years. Also, of the total number of respondents, only 4.2% benefited from a study program of at least one semester at a university abroad.

3. Results

H1. The influence of skills, abilities, competencies and knowledge acquired during the years of study on the income and ensuring a decent living of graduates

One of the objectives of the paper is to analyse the extent to which the skills, abilities, competencies and knowledge acquired during the years of study influence the level of income and the possibility of ensuring a decent living of graduates. In this regard, the statistical analysis carried out indicates that there is a significant correlation between skills, abilities, competencies, knowledge, personality traits and the income earned by graduates. This aspect is indicated by the fact that the value of P Chi square is close to zero (0.000) and lower than the accepted limit of 0.05. Thus, it can be said that there is a correlation between the skills, abilities, competencies and knowledge that graduates consider having acquired during the years of study and the facilitation of the transition to the workplace by obtaining good paid jobs. Graduates who consider that the skills acquired during their years of study greatly facilitate their transition to the workplace have higher incomes than those who consider that these skills did not help them. Furthermore, it can be observed that there is a significant correlation between the perception of ensuring a decent living through the salary earned and the skills and competences acquired during their years of study, as the statistical analysis indicates that the statistical indicator p is close to zero (0.000) and lower than the accepted limit of 0.005. Thus, it can be stated that the more skills, aptitudes and knowledge students acquire, the greater their chances of earning income that allows them to ensure a decent living. However, some differences are noted according to gender. Male respondents are more likely to consider that the salary they earn is sufficient to ensure a decent living, while female respondents are less satisfied with the salary level.

Table 2.

Crosstab analysis between the influence of information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired during the years of study and particularities of the workplace. Source: report provided by SPSS software.

Table 2.

Crosstab analysis between the influence of information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired during the years of study and particularities of the workplace. Source: report provided by SPSS software.

| Item |

Options |

The influence of information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired during the years of study |

Total |

|

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

| I work in the field I trained in |

No |

8 |

11 |

33 |

38 |

43 |

133 |

|

| Yes |

3 |

10 |

40 |

43 |

104 |

200 |

|

| How long did it take you to find a job from the moment you started looking? |

less than 1 month |

2 |

9 |

22 |

32 |

60 |

125 |

|

| between 1 and 2 months |

0 |

7 |

14 |

22 |

27 |

70 |

|

| between 2 and 4 months |

2 |

1 |

10 |

6 |

13 |

32 |

|

| between 4 and 6 months |

0 |

1 |

7 |

4 |

9 |

21 |

|

| more than 6 months |

7 |

3 |

20 |

17 |

38 |

85 |

|

| What is the sector/field of activity in which you work? |

education |

1 |

5 |

12 |

22 |

64 |

104 |

|

| coaching and training |

2 |

1 |

15 |

15 |

30 |

63 |

|

| sport industry / clubs/ federations / |

0 |

4 |

10 |

6 |

9 |

29 |

|

| recreational sport |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

|

| sports goods trade |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

|

| health |

2 |

1 |

16 |

6 |

6 |

31 |

|

| outside the sports field |

6 |

7 |

18 |

31 |

36 |

98 |

|

| I have an employment contract: |

for a fixed period |

0 |

11 |

27 |

30 |

66 |

134 |

|

| for an indefinite period |

11 |

10 |

46 |

51 |

81 |

199 |

|

| How many hours do you work per week? |

less than 10 hours |

3 |

5 |

13 |

14 |

14 |

49 |

|

| between 10 - 20 hours |

2 |

3 |

19 |

25 |

46 |

95 |

|

| between 20 - 30 hours |

2 |

3 |

9 |

11 |

28 |

53 |

|

| between 30 - 40 hours |

2 |

5 |

16 |

12 |

20 |

55 |

|

| More than 40 hours |

2 |

5 |

16 |

19 |

39 |

81 |

|

| Your income is: |

less than 2.500 RON |

5 |

6 |

21 |

19 |

13 |

64 |

|

| between 2.500 - 3.500 RON |

2 |

0 |

14 |

20 |

24 |

60 |

|

| between 3.500 - 5.000 RON |

1 |

11 |

21 |

28 |

47 |

108 |

|

| between 5.000 - 7.000 RON |

1 |

2 |

4 |

8 |

43 |

58 |

|

| between 7.000 - 10.000 RON |

0 |

1 |

8 |

4 |

16 |

29 |

|

| More than 10.000 RON |

2 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

4 |

14 |

|

| Total |

11 |

21 |

73 |

81 |

147 |

333 |

333 |

Table 3.

Correlations between the influence of information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired during the years of study and job satisfaction. Source: report provided by SPSS software.

Table 3.

Correlations between the influence of information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired during the years of study and job satisfaction. Source: report provided by SPSS software.

| |

Coefficient |

p |

| I work in the field I trained in |

Chi-Square |

15.771 |

0.003 |

| Phi |

0.218 |

0.003 |

| Cramer's V |

0.218 |

0.003 |

| Contingency Coefficient |

0.213 |

0.003 |

| How long did it take you to find a job from the moment you started looking? |

Chi-Square |

22.166 |

0.138 |

| Phi |

0.258 |

0.138 |

| Cramer's V |

0.129 |

0.138 |

| Contingency Coefficient |

0.250 |

0.138 |

| What is the sector/field of activity in which you work? |

Chi-Square |

63.518 |

0.000 |

| Phi |

0.437 |

0.000 |

| Cramer's V |

0.218 |

0.000 |

| Contingency Coefficient |

0.400 |

0.000 |

| I have an employment contract: |

Chi-Square |

10.687 |

0.030 |

| Phi |

0.179 |

0.030 |

| Cramer's V |

0.179 |

0.030 |

| Contingency Coefficient |

0.176 |

0.030 |

| How many hours do you work per week? |

Chi-Square |

13.895 |

0.607 |

| Phi |

0.204 |

0.607 |

| Cramer's V |

0.102 |

0.607 |

| Contingency Coefficient |

0.200 |

0.607 |

| Your income is: |

Chi-Square |

61.470 |

0.000 |

| Phi |

0.430 |

0.000 |

| Cramer's V |

0.215 |

0.000 |

| Contingency Coefficient |

0.395 |

0.000 |

Table 4.

Correlations between the influence of information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired during the years of study and the particularities of the workplace. Source: report provided by SPSS software.

Table 4.

Correlations between the influence of information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired during the years of study and the particularities of the workplace. Source: report provided by SPSS software.

| |

|

Coefficient |

p |

| How easy do you think it was for you to find a job after completing your studies? |

Somers' d |

0.228 |

0.000 |

| Kendall's tau-b |

0.229 |

0.000 |

| Gamma |

0.304 |

0.000 |

| To what extent do you think the labour market does not offer enough opportunities for young graduates? |

Somers' d |

0.171 |

0.000 |

| Kendall's tau-b |

0.172 |

0.000 |

| Gamma |

0.232 |

0.000 |

| To what extent do you think the salary you earn allows you to ensure a decent living? |

Somers' d |

0.203 |

0.000 |

| Kendall's tau-b |

0.203 |

0.000 |

| Gamma |

0.276 |

0.000 |

| To what extent do you think your salary expectations are too high compared to what employers offer? |

Somers' d |

-0.004 |

0.934 |

| Kendall's tau-b |

-0.004 |

0.934 |

| Gamma |

-0.006 |

0.934 |

| I am seriously considering changing my job in the next 6 months. |

Somers' d |

-0.256 |

0.000 |

| Kendall's tau-b |

-0.256 |

0.000 |

| Gamma |

-0.348 |

0.000 |

| I am seriously considering working in a field other than the one in which I trained because either there are not enough opportunities or the salary does not satisfy me. |

Somers' d |

-0.193 |

0.000 |

| Kendall's tau-b |

-0.193 |

0.000 |

| Gamma |

-0.264 |

0.000 |

| I have thought at least once in the last 12 months about emigrating because I believe that the labour market in Romania does not offer the necessary opportunities. |

Somers' d |

-0.166 |

0.001 |

| Kendall's tau-b |

-0.166 |

0.001 |

| Gamma |

-0.232 |

0.001 |

| At my current workplace, I feel confident that I can successfully fulfil my tasks and duties |

Somers' d |

0.277 |

0.000 |

| Kendall's tau-b |

0.278 |

0.000 |

| Gamma |

0.407 |

0.000 |

| In general, I consider myself satisfied and fulfilled at work. |

Somers' d |

0.318 |

0.000 |

| Kendall's tau-b |

0.318 |

0.000 |

| Gamma |

0.431 |

0.000 |

Table 5.

To what extent do you consider that the salary you earn allows you to ensure a decent living? Source: report provided by SPSS software.

Table 5.

To what extent do you consider that the salary you earn allows you to ensure a decent living? Source: report provided by SPSS software.

| Count |

| |

Gender |

Total |

| Male |

Female |

| To what extent do you consider that the salary you earn allows you to ensure a decent living? |

1 |

21 |

36 |

57 |

| 2 |

38 |

40 |

78 |

| 3 |

80 |

31 |

111 |

| 4 |

34 |

17 |

51 |

| 5 |

28 |

8 |

36 |

| Total |

201 |

132 |

333 |

H2. Information, skills, abilities and competences acquired during the years of study influence job satisfaction and confidence.

The other objective of the paper is to analyse the extent to which the skills, abilities, abilities and knowledge acquired influence job satisfaction and confidence. Thus, direct indicators were analysed that reveal the general degree of satisfaction and job satisfaction, confidence in the ability to perform tasks and duties at work, but also other indirect indicators that suggest job satisfaction: desire to change jobs, desire to change industries, desire to emigrate, perception of opportunities on the labour market or perception of the ease of finding a job.

First, it can be observed that there is a significant correlation between graduates who believe that the information, skills and competences acquired during their years of study have facilitated their transition from university to the workplace and the general level of satisfaction and job satisfaction at work, as the statistical indicator p is close to zero (0.000) and below the accepted limit of 0.005. Thus, it can be said that students who acquire more skills, competences and information during their years of study tend to be more satisfied at work as they have greater chances of employment in well-paid positions, can implement their knowledge and can see that the result of their work during their studies has been prolific. Also, another significant correlation is observed between the level of knowledge acquired during the years of study and confidence in one's own ability to successfully perform tasks and duties, since the statistical coefficient p is close to zero (0.000) and below the accepted limit of 0.05. Thus, it can be said that conscientious graduates, who focus on developing skills, competencies and aptitudes and on acquiring a volume of information, are more confident in their own strengths at work because they can use what they have learned at work, and if there is a need to learn new skills for these respondents, it would be easier because they have this training experience.

As previously mentioned, we also considered other indirect indicators to analyse the degree of job satisfaction. Specifically, a significant correlation is noted between the skills acquired during the years of study and the ease of finding a job (p=0.000), between the skills acquired and the perception that the labour market offers sufficient opportunities (p=0.000), between the skills acquired and the desire to change jobs in the next six months (p=0.000), between skills and changing the field of activity (p=0.000), and between skills and the desire to emigrate (p=0.001). In all these correlations, the p-statistic is close to zero, below the maximum allowed limit of 0.05. However, although the correlations are significant, they are not that strong, but even so we can see that these correlations can explain certain causes and effects.

Analysing these correlations, it can be stated that graduates who accumulate more skills, abilities, competences and knowledge find a job more easily and still consider that the Romanian labour market offers sufficient opportunities. Thus, the better prepared a graduate is, the easier it is for him to take advantage of the opportunities existing on the labour market. Also, the same students do not think about changing their job, field or emigrating. There is an inversely proportional relationship between skills, abilities, competences, knowledge and the desire to change jobs or to emigrate. Basically, the more skills students acquire, the easier it is for them to find a better-paid job that offers security and does not lead them to change jobs or emigrate. Also, if a student has dedicated time to training in a certain field, he will not want to give up the field in which he trained so easily.

In

Table 7, the distribution of responses regarding students' perception of their own abilities, skills and aptitudes can be observed. Moreover, in

Table 7, the average of responses for this self-perception can be observed, the table being also ordered in descending order, starting with the abilities in which students consider themselves to excel, to the abilities in which students should further improve. Thus, at the top of the list is the passion for sports (which is normal since sports represent the passion that students want to transform into a profession), followed by the continuous desire for improvement, conscientiousness, the ability to work in a team, ethical and integrity behaviour, openness to the new, the ability to adapt to change and respect for hierarchies and internal regulations. Thus, it can be said that these abilities and aptitudes are formed through sports and are practically values promoted by sports and which could also be applied within the framework of organizations that do not necessarily operate in the sports industry. Sports train young people and adolescents to respect hierarchies, regulations, to behave ethically and, in the case of team sports, to work as a team to achieve common goals. At the opposite, among the skills, aptitudes and competences that students consider they need to improve include: the ability to speak in public, general management skills, the ability to communicate orally and in writing in a foreign language, the ability to sell or the ability to manage a project. At the same time, it should be noted that these skills and competences are more important in certain fields than in others. Specifically, a physiotherapist will speak much less, if not at all, in front of a large audience, while a manager of a sports organization may have to do so frequently. This is also valid for management or project management skills.

Table 6.

Analysis of students' skills, competences and personal traits "On a scale from 1 to 5, to what extent do you consider yourself to possess these skills/abilities (1 = to a very small extent; 5 = to a very large extent): Source: own contribution.

Table 6.

Analysis of students' skills, competences and personal traits "On a scale from 1 to 5, to what extent do you consider yourself to possess these skills/abilities (1 = to a very small extent; 5 = to a very large extent): Source: own contribution.

| Item |

Score |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

To what extent do you consider that the information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired during your years of study facilitated your transition from academia to the workplace?

|

Frequency |

11 |

21 |

73 |

81 |

147 |

| Percent |

3.3% |

6.3% |

21.9% |

24.3% |

44.1% |

General management skills

|

Frequency |

11 |

30 |

120 |

101 |

71 |

| Percent |

3.3% |

9% |

36% |

30.3% |

21.3% |

Leadership skills

|

Frequency |

8 |

26 |

66 |

123 |

110 |

| Percent |

2.4% |

7.8% |

19.8% |

36.9% |

33% |

Ability to manage a project

|

Frequency |

3 |

17 |

99 |

124 |

90 |

| Percent |

0.9% |

5.1% |

29.7% |

37.2% |

27% |

Time management

|

Frequency |

5 |

26 |

81 |

110 |

111 |

| Percent |

1.5% |

7.8% |

24.3% |

33% |

33.3% |

Ability to work effectively in a team to achieve common goals

|

Frequency |

4 |

4 |

34 |

90 |

201 |

| Percent |

1.2% |

1.2% |

10.2% |

27% |

60.4% |

Ability to speak in public in front of a large audience

|

Frequency |

16 |

49 |

94 |

96 |

78 |

| Percent |

4.8% |

14.7% |

28.2% |

28.8% |

23.4% |

Ability to listen actively (listen carefully)

|

Frequency |

2 |

12 |

37 |

111 |

171 |

| Percent |

0.6% |

3.6% |

11.1% |

33.3% |

51.4% |

Ability to express oneself effectively in writing

|

Frequency |

7 |

10 |

51 |

124 |

141 |

| Percent |

2.1% |

3% |

15.3% |

37.2% |

42.3% |

Ability to communicate orally and in writing in at least one foreign language

|

Frequency |

16 |

37 |

105 |

85 |

90 |

| Percent |

4.8% |

11.1% |

31.5% |

25.5% |

27% |

Ability to plan

|

Frequency |

2 |

8 |

69 |

124 |

130 |

| Percent |

0.6% |

2.4% |

20.7% |

37.2% |

39% |

Ability to organize and use available resources efficiently

|

Frequency |

3 |

6 |

62 |

123 |

139 |

| Percent |

0.9% |

1.8% |

18.6% |

36.9% |

41.7% |

Ability to integrate new technologies into everyday tasks

|

Frequency |

3 |

12 |

66 |

117 |

135 |

| Percent |

0.9% |

3.6% |

19.8% |

35.1% |

40.5% |

General ability to solve problems with minimal risks and safely

|

Frequency |

2 |

16 |

49 |

132 |

134 |

| Percent |

0.6% |

4.8% |

14.7% |

39.6% |

40.2% |

Ability to make decisions under stress

|

Frequency |

5 |

8 |

68 |

122 |

130 |

| Percent |

1.5% |

2.4% |

20.4% |

36.6% |

39% |

| Ability to make decisions under risk |

Frequency |

4 |

16 |

84 |

113 |

116 |

| Percent |

1.2% |

4.8% |

25.2% |

33.9% |

34.8% |

Continuous desire for improvement |

Frequency |

3 |

2 |

24 |

73 |

231 |

| Percent |

0.9% |

0.6% |

7.2% |

21.9% |

69.4% |

Ability to analyze work and progress objectively |

Frequency |

3 |

4 |

46 |

125 |

155 |

| Percent |

0.9% |

1.2% |

13.8% |

37.5% |

46.5% |

Ethical and integrity behavior |

Frequency |

3 |

5 |

36 |

91 |

198 |

| Percent |

0.9% |

1.5% |

10.8% |

27.3% |

59.5% |

Passion for sports |

Frequency |

3 |

3 |

18 |

30 |

279 |

| Percent |

0.9% |

0.9% |

5.4% |

9% |

83.8% |

Self-control ability |

Frequency |

5 |

6 |

29 |

114 |

179 |

| Percent |

1.5% |

1.8% |

8.7% |

34.2% |

53.8% |

Ability to resolve conflicts |

Frequency |

2 |

8 |

34 |

118 |

171 |

| Percent |

0.6% |

2.4% |

10.2% |

35.4% |

51.4% |

Ability to manage a budget |

Frequency |

3 |

12 |

48 |

107 |

163 |

| Percent |

0.9% |

3.6% |

14.4% |

32.1% |

48.9% |

Ability to create and maintain relationships (networking) |

Frequency |

2 |

17 |

72 |

107 |

135 |

| Percent |

0.6% |

5.1% |

21.6% |

32.1% |

40.5% |

Ability to distinguish fake news from scientific information |

Frequency |

6 |

10 |

60 |

109 |

148 |

| Percent |

1.8% |

3% |

18% |

32.7% |

44.4% |

Patience |

Frequency |

2 |

8 |

44 |

90 |

189 |

| Percent |

0.6% |

2.4% |

13.2% |

27% |

56.8% |

Creativity |

Frequency |

2 |

7 |

50 |

125 |

149 |

| Percent |

0.6% |

2.1% |

15% |

37.5% |

44.7% |

Ability to adapt to change |

Frequency |

0 |

6 |

40 |

100 |

187 |

| Percent |

0% |

1.8% |

12% |

30% |

56.2% |

Vision and ability to plan long-term |

Frequency |

0 |

13 |

43 |

122 |

155 |

| Percent |

0% |

3.9% |

12.9% |

36.6v |

46.5% |

Ability to work in culturally diverse teams (with members of several nationalities) |

Frequency |

4 |

10 |

63 |

97 |

159 |

| Percent |

1.2% |

3% |

18.9% |

29.1% |

47.7% |

Ability to sell and sell oneself |

Frequency |

11 |

29 |

96 |

96 |

101 |

| Percent |

3.3% |

8.7% |

28.8% |

28.8% |

30.3% |

Spirit of initiative |

Frequency |

1 |

8 |

54 |

113 |

157 |

| Percent |

0.3% |

2.4% |

16.2% |

33.9% |

47.1% |

Respect for hierarchies, boundaries and internal regulations |

Frequency |

2 |

9 |

39 |

95 |

188 |

| Percent |

0.6% |

2.7% |

11.7% |

28.5% |

56.5% |

Openness to new experiences |

Frequency |

3 |

5 |

38 |

88 |

199 |

| Percent |

0.9% |

1.5% |

11.4% |

26.4% |

59.8% |

Conscientiousness |

Frequency |

2 |

5 |

33 |

88 |

205 |

| Percent |

0.6% |

1.5% |

9.9% |

26.4% |

61.6% |

Extroversion |

Frequency |

12 |

19 |

82 |

110 |

110 |

| Percent |

3.6% |

5.7% |

24.6% |

33% |

33% |

Ability to be agreeable despite everyday problems |

Frequency |

5 |

7 |

58 |

124 |

139 |

| Percent |

1.5% |

2.1% |

17.4% |

37.2% |

41.7% |

| To what extent do you consider that the information, skills, attitudes and competences acquired during your years of study facilitated your transition from academia to the workplace? |

Frequency |

4 |

8 |

41 |

125 |

155 |

| Percent |

1.2% |

2.4% |

12.3% |

37.5% |

46.5% |

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics on students' perceptions of their own skills, competencies and aptitudes. Source: report provided by SPSS software and supplemented with employers' questionnaire responses.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics on students' perceptions of their own skills, competencies and aptitudes. Source: report provided by SPSS software and supplemented with employers' questionnaire responses.

| Item |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Employer perception |

| Passion for sports |

1 |

5 |

4.74 |

0.682 |

4 |

| Continuous desire for improvement |

1 |

5 |

4.58 |

0.73 |

3.6 |

| Conscientiousness |

1 |

5 |

4.47 |

0.782 |

3.6 |

| Ability to work effectively in a team in order to achieve common goals |

1 |

5 |

4.44 |

0.818 |

4 |

| Ethical and honest behavior |

1 |

5 |

4.43 |

0.813 |

4.1 |

| Openness to new experiences |

1 |

5 |

4.43 |

0.82 |

3.8 |

| Ability to adapt to change |

2 |

5 |

4.41 |

0.769 |

4 |

| Respect for hierarchies, boundaries and internal regulations |

1 |

5 |

4.38 |

0.84 |

3.7 |

| Self-control ability |

1 |

5 |

4.37 |

0.835 |

3.2 |

| Patience |

1 |

5 |

4.37 |

0.846 |

3.3 |

| Ability to resolve conflicts |

1 |

5 |

4.35 |

0.805 |

3 |

| Ability to listen actively (listen carefully) |

1 |

5 |

4.31 |

0.853 |

3.5 |

| Ability to analyze work and progress objectively |

1 |

5 |

4.28 |

0.811 |

3.3 |

| Vision and ability to plan long-term |

2 |

5 |

4.26 |

0.828 |

3.1 |

| Ability to be emotionally stable |

1 |

5 |

4.26 |

0.853 |

3.3 |

| Ability to manage a budget |

1 |

5 |

4.25 |

0.895 |

3 |

| Spirit of initiative |

1 |

5 |

4.25 |

0.834 |

3 |

| Creativity |

1 |

5 |

4.24 |

0.826 |

4 |

| Ability to work in culturally diverse teams (with members of several nationalities) |

1 |

5 |

4.19 |

0.928 |

3.8 |

| Ability to organize and use available resources efficiently |

1 |

5 |

4.17 |

0.855 |

3.3 |

| Ability to be agreeable despite everyday problems |

1 |

5 |

4.16 |

0.888 |

3.8 |

| Ability to express oneself effectively in writing |

1 |

5 |

4.15 |

0.931 |

3.4 |

| Ability to distinguish fake news from scientific information |

1 |

5 |

4.15 |

0.942 |

3.1 |

| General ability to solve problems with minimal risk and safely |

1 |

5 |

4.14 |

0.882 |

3.1 |

| Ability to plan |

1 |

5 |

4.12 |

0.858 |

3.4 |

| Ability to integrate new technologies into daily tasks |

1 |

5 |

4.11 |

0.905 |

4 |

| Ability to make decisions under stress |

1 |

5 |

4.09 |

0.905 |

2.6 |

| Ability to create and maintain relationships (networking) |

1 |

5 |

4.07 |

0.937 |

3.7 |

| Ability to make decisions under risk |

1 |

5 |

3.96 |

0.95 |

2.7 |

| Leadership skills |

1 |

5 |

3.9 |

1.025 |

2.5 |

| Time management |

1 |

5 |

3.89 |

1.007 |

3.3 |

| Extroversion (ability to be extroverted) |

1 |

5 |

3.86 |

1.055 |

3.7 |

| Ability to manage a project |

1 |

5 |

3.84 |

0.912 |

3 |

| Ability to sell and sell oneself |

1 |

5 |

3.74 |

1.084 |

3.2 |

| Ability to communicate orally and in writing in at least one foreign language |

1 |

5 |

3.59 |

1.139 |

3.4 |

| General management skills |

1 |

5 |

3.57 |

1.026 |

2.6 |

| Ability to speak in public in front of a large audience |

1 |

5 |

3.51 |

1.142 |

3.1 |

Also, to analyse the self-perception of students' abilities, we addressed a questionnaire among 11 employers, from all regions of Romania, who have an experience ranging between 10 and 32 years in the sports industry, hiring in the following fields: education (3/11), sports coaching and training (3/11), health (1/11) and in the professional sports industry (sports organizations or federations (4/11). The sample may represent a limitation of the research, but it must be considered that the sports industry in Romania is not as developed as those in Western Europe and automatically the number of employers at the national level is smaller. Thus, in the last column of

Table 7, we can see the average that employers attributed to graduates' competencies. This allows a comparison between what students think about themselves and what employers consider about graduates' competencies.

Overall, large discrepancies can be observed, with students tending to overestimate their abilities, skills and aptitudes. Practically, compared to the perception of employers, all the graduates' responses are overestimated. The largest discrepancies are recorded, in this order: decision making under risk; leadership skills, conscientiousness; making decisions under stress, the ability to manage a budget, the ability to self-control and patience. On the other hand, among the skills that students overestimate the least, are the ability to communicate in a foreign language, creativity or extroversion. These discrepancies also suggest that students should develop their self-assessment capacity.

4. Discussions

In Romania, not many studies and statistics have been conducted to analyse the competencies, skills, aptitudes and personality traits of Romanian students, and in the field of the sports industry there are even fewer such studies, and this brings an added relevance and an element of novelty to our study. However, there are other studies that highlight, as in the case of our study, a connection between the knowledge, skills, aptitudes acquired during the years of study and the salary level (21= Pierre, Collinet, Schut 2022, Diaconu, 2014). There are also a series of studies that support our results, among which Diaconu's study (2= 2014) states that In Europe and the EU the higher the level of education, the better chances of employment. Also, in crisis situations (such as pandemics or economic recessions), for people with secondary education the challenges are greater, while for high education level graduates it is easier to find and keep a job. Thus, a positive relationship is noted between education level and finding a job, an aspect also highlighted by (1= Gavriluță, 2022). Moreover, an increased education level for the young workforce is correlated with economic freedom and higher opportunity for developing the entrepreneurship (1= Gavriluță, 2022).

One of the only studies conducted on students who graduated from the Faculty of Physical Education and Sports in Romania, targets a university in the historical area of Oltenia, and targets graduates between 2015 and 2019 (11= Barbu, Diaconescu, Stepan, Popescu, 2020). According to this study, many of the graduates have not yet found a job, and of those who have found one, they do not work in the field in which they were trained. Most of them work in other industries and services, then there is a percentage that works in health, education or trade. Among the jobs they occupy are teacher, sales agent, driver, physiotherapist, sports instructor or sales consultant. (11=Barbu, Diaconescu, Stepan, Popescu, 2020). Also, as our study shows, a percentage of graduates are tempted to emigrate, and this is also highlighted by (58=Vasile, 2012), who states that this desire is even more pressing in crisis situations when the desire to increase their income is greater.

Another study conducted in Romania, but this time on a sample of students from economics and business administration faculties, indicates that in the perception of students, integration into the labour market depends on the acquisition of knowledge, its revision, the ability to adapt to change and the application of knowledge (59=Neștian et al, 2021).

5. Conclusions, Limits and Future Research

Society is changing rapidly, and the sustainable economic and social development of a nation is based on education and on the development of skills, aptitudes and competences that facilitate the rapid integration of graduates into the labour market, especially in the field in which they were trained. A reduced insertion into the labour market or activation in fields in which graduates were not trained can lead to an increase in both emigration and immigration, to the accentuation of social inequalities and to a decrease in the standard of living. Romania must continue to make progress in terms of education to achieve the sustainability goals. More and more people are afraid of the evolution of artificial intelligence and the fact that it will replace human resources. One of the ways to remain competitive in the labour market is the continuous development of skills. Developing soft skills can be an advantage in the fight against artificial intelligence. Higher education institutions should emphasize instilling a positive attitude towards continuous improvement and drawing attention to the fact that obtaining a permanent position should not automatically mean stopping continuous development. The workforce must know to remain competitive in the labour market, continuous training is needed, and higher education institutions must offer such study programs.

In conclusion, it can be stated that the more skills, abilities and knowledge students acquire, the greater their chances of earning income that will allow them to ensure a decent living, which implicitly leads to sustainable development. It can also be said that students who acquire more skills, abilities, competencies and information during their years of study tend to be more satisfied at work because they have a greater chance of employment in well-paid positions, can implement their knowledge and can see that the result of their work during their studies has been prolific. Although higher education institutions are criticized especially for their lack of development of needed skills by the labour market, a link between skills acquired during studies and income levels is observed in Romania and other countries. Certainly, higher education institutions can improve their curricula, pedagogy or research level, but these are also closely related to the level of funding. On the other hand, the business environment should be more open to collaborating with higher education institutions in terms of curriculum development, offering internships, employment or funding research projects. Even though difficult times can lead to difficulties in finding and keeping a job, they can facilitate the growth of students' resilience and implicitly the development of qualities that can be put into practice in finding and keeping a job. Thus, the development of resilience can be achieved by developing the skills to make decisions under conditions of risk and uncertainty.

As for the limitations of the study, these are represented by the small sample for analysing the employers' perspective. Also, the questionnaire contains a relatively large number of questions, which for some of the respondents may be considered too long, which is also the explanation for why out of the total of 532 respondents who started the questionnaire, only 333 finished it. At the same time, the results may also be relevant for recruiters from other countries, Romania is a supplier of labour for the European labour market, where millions of Romanians already work. The use of this questionnaire adapted to the particularities of a local economy can provide valuable results regarding the skills obtained by students. In the next future, other studies addressing the same research topic are to be published.

Author Contributions

The authors have contributed and collaborated for the whole manuscript. Both authors have contributed substantially to the research work and paper. The authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Both authors have equal rights. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

QR code for the student’s questionnaire

References

- Gavriluță, N., Grecu, S. P., & Chiriac, H. C. (2022). Sustainability and employability in the time of COVID-19. Youth, education and entrepreneurship in EU countries. Sustainability, 14(3), 1589. [CrossRef]

- Diaconu, L. (2014). Education and labour market outcomes in Romania. Eastern Journal of European Studies, 5(1), 99-112.

- Altig, D.; Baker, S.; Barrer, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Bunn, P.; Chen, S.; Davis, S.J.; Leather, J.; Meyer, B.; Mihaylov, E.; et al. Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104274. [CrossRef]

- Sirbu, R. M., Popescu, A. D., Borca, C., & Draghici, A. (2015). A study on Romania sustainable development. Procedia Technology, 19, 416-423.

- Ibinceanu, C. O. M., Nicoleta, C., Cătălin, D. R., & Margareta, F. (2021). Regional development in Romania: Empirical evidence regarding the factors for measuring a prosperous and sustainable economy. Sustainability, 13(7), 3942. [CrossRef]

- Institutional Paper 247 (2023) Country Report Romania (2023) Institutional paper 247, june 2023, European Comission, ISSN 2443-8014 (online), p5,11,60,62.

- Serban, A. C. (2012). A better employability through labour market flexibility. The case of Romania. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 4539-4543. [CrossRef]

- Romanian Statistical Yearbook (2016) National Institute of Statistics, I.S.S.N. : 1220 - 3246 I.S.S.N.-L : 1220 – 3246.

- Stanciu, S., & Banciu, V. (2012). Quality of higher education in Romania: Are graduates prepared for the labour market?. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 821-827. [CrossRef]

- Vlasceanu, L., Grunberg, L., Parlea, D. (2007). Quality Assurance and Accreditation, Bucharest: CEPES.

- Barbu, R M. C., Raluca, S. A., Maria, S. O., Sorin, P. S., Laurențiu, D. D., Daniel, P. L., ... & Cătălin, P. M. (2020). Employability Of Graduates In The Field Of Physical Education And Sport, Studies Programs “Physical And Sports Education” And “Kinetotherapy” In The Southwest Region Of Oltenia. Annals-Economy Series, 6, 48-56.

- CEDEFOP European Center for the Development of Vocational Training (2010), Skills supply and demand in Europe, Cedefop Louxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union 2010.

- OECD (2022), OECD Economic Surveys: Romania 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat (2023) Fewer young people neither employed nor in education, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230526-3 (retrived 25.02.2025).

- Kellett, P., & Shilbury, D. (2010). Sport management in Australia: An organisational overview. Allen & Unwin.

- Aymar, P., Desbordes, M., & Hautbois, C. (2019). Management global du sport: Marketing, gouvernance, industrie et distribution (No. hal-04321428).

- Desbordes, M., & Hautbois, C. (2020). Management du sport 3.0: Spectacle, fan experience, digital (No. hal-04326355).

- McCrae, R. R., Costa, Jr, P. T., & Martin, T. A. (2005). The NEO–PI–3: A more readable revised NEO personality inventory. Journal of personality assessment, 84(3), 261-270. [CrossRef]

- Shilbury, D. (2017). Golf governance. In Golf Business and Management (pp. 35-50). Routledge.

- Hoye, R., Smith, A. C., Nicholson, M., & Stewart, B. (2015). Sport management: Principles and applications. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J., Collinet, C., & Schut, P. O. (2022). STAPS graduates: What training for what professional integration?. Staps, 137(3), 11-34. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A., & Levine, J. (2016). “This class has opened up my eyes”: Assessing outcomes of a sport-for-development curriculum on sport management graduate students. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 19, 97-103. [CrossRef]

- Eagleman, A. N., & McNary, E. L. (2010). What are we teaching our students? A descriptive examination of the current status of undergraduate sport management curricula in the United States. Sport Management Education Journal, 4(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Dharamsi, K. (2017). Educating for a common world: The university goes to school. The Journal of General Education, 66(3-4), 235-251. [CrossRef]

- De Schepper, J., & Sotiriadou, P. (2018). A framework for critical reflection in sport management education and graduate employability. Annals of Leisure Research, 21(2), 227-245. [CrossRef]

- Keiper, M. C., Sieszputowski, J., Morgan, T., & Mackey, M. J. (2019). Employability Skills: A Case Study on a Business-Oriented Sport Management Program. E-journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching, 13(1), 59-68.

- Todd, S. Y., Magnusen, M., Andrew, D. P., & Lachowetz, T. (2014). From great expectations to realistic career outlooks: Exploring changes in job seeker perspectives following realistic job previews in sport. Sport Management Education Journal, 8(1), 58-70. [CrossRef]

- Amis, J., & Silk, M. (2005). Rupture: Promoting critical and innovative approaches to the study of sport management. Journal of Sport Management, 19(4), 355-366. [CrossRef]

- Frisby, C. L. (1992). Thinking skills instruction: What do we really want?. In The Educational Forum (Vol. 56, No. 1, pp. 21-35). Taylor & Francis Group. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, M. H., & Drennan, L. (2008). What skills and attributes does an accounting graduate need? Evidence from student perceptions and employer expectations. Accounting & Finance, 48(2), 279-300. [CrossRef]

- Ipsos-Eureka Social Research Institute. 2010. Faculty of Law & Management Project 3. The University experience and graduate employability. La Trobe University Faculty of Law and Management consultancy report. Project number 10-009038-01.

- Chelladurai, P., & Chang, K. (2000). Targets and standards of quality in sport services. Sport management review, 3(1), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Howat, G., Absher, J., Crilley, G., & Milne, I. (1996). Measuring customer service quality in sports and leisure centres. Managing leisure, 1(2), 77-89. [CrossRef]

- Tsitskari, E., Goudas, M., Tsalouchou, E., & Michalopoulou, M. (2017). Employers’ expectations of the employability skills needed in the sport and recreation environment. Journal of hospitality, leisure, sport & tourism education, 20, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Small, L., Shacklock, K., & Marchant, T. (2018). Employability: A contemporary review for higher education stakeholders. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 70(1), 148-166. [CrossRef]

- Baciu, E. L. (2022). Employment Outcomes of Higher Education Graduates from during and after the 2007–2008 Financial Crisis: Evidence from a Romanian University. Sustainability, 14(18), 11160. [CrossRef]

- Mackieh, A. A., & Dlhin, F. S. A. (2019). Evaluating the employability skills of industrial engineering graduates: A case study. The International journal of engineering education, 35(3), 925-937.

- Molina-García, N., González-Serrano, M. H., Ordiñana-Bellver, D., & Baena-Morales, S. (2024). Redefining Education in Sports Sciences: A Theoretical Study for Integrating Competency-Based Learning for Sustainable Employment in Spain. Social Sciences, 13(5), 242. [CrossRef]

- Donald, W. E., Ashleigh, M. J., & Baruch, Y. (2018). Students’ perceptions of education and employability: Facilitating career transition from higher education into the labor market. Career development international, 23(5), 513-540. [CrossRef]

- Baker, C., Loughren, E. A., Dickson, T., Goudas, M., Crone, D., Kudlacek, M., ... & Tassell, R. (2017). Sports graduate capabilities and competencies: A comparison of graduate and employer perceptions in six EU countries. European Journal for Sport and Society, 14(2), 95-116. [CrossRef]

- Levett-Jones, T., Gersbach, J., Arthur, C., & Roche, J. (2011). Implementing a clinical competency assessment model that promotes critical reflection and ensures nursing graduates’ readiness for professional practice. Nurse education in practice, 11(1), 64-69. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, L. M., & Spencer, S. M. (1993). Competence at Work. New York: Jhon Wiley & Sons. Inc, l993.

- Coll, R. K., & Zegwaard, K. E. (2006). Perceptions of desirable graduate competencies for science and technology new graduates. Research in Science & Technological Education, 24(1), 29-58. [CrossRef]

- Arbi, K. A., Bukhari, S. A. H., & Saadat, Z. (2017). Theoretical framework for taxonomizing sources of competitive advantage. Management Research and Practice, 9(4), 48-60.

- Sider, S. T., García, A. C., el Hierro Pinés, D., & del Castillo, J. M. (2019). Componentes de la satisfacción del cliente interno en centros deportivos de la Comunidad de Madrid. Su influencia en la gestión. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, (426), ág-482. [CrossRef]

- Rychen, D. S. E., & Salganik, L. H. E. (2003). Key competencies for a successful life and a well-functioning society. Hogrefe & Huber Publishers. ISBN 0-88937-272-1.

- Matteson, M. L., Anderson, L., & Boyden, C. (2016). " Soft skills": A phrase in search of meaning. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 16(1), 71-88. [CrossRef]

- de Schepper, J., Sotiriadou, P., & Hill, B. (2021). The role of critical reflection as an employability skill in sport management. European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(2), 280-301. [CrossRef]

- Birkett, W.P. (1993). Competency based standards for professional accountant in Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne: Australian Society of Certified Practicing Accountants.

- Archer, W., & Davison, J. (2008). Graduate employability: What do employers think and want. The council for industry and Higher Education, 811, 1-20.

- Crawford, A., Weber, M. R., & Lee, J. (2020). Using a grounded theory approach to understand the process of teaching soft skills on the job so to apply it in the hospitality classroom. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 26, 100239. [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. R., Crawford, A., Lee, J., & Dennison, D. (2013). An exploratory analysis of soft skill competencies needed for the hospitality industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 12(4), 313-332. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K., Bullough, S., Shibli, S., & Wilson, J. (2017). The impact of engagement in sport on graduate employability: Implications for higher education policy and practice. International journal of sport policy and politics, 9(3), 431-451. [CrossRef]

- Sato, S., Kang, T. A., Daigo, E., Matsuoka, H., & Harada, M. (2021). Graduate employability and higher education’s contributions to human resource development in sport business before and after COVID-19. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 28, 100306. [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D. (2022). How hope measures up: Hope predicts school variables beyond growth mindset and school belonging. Current Psychology, 41(7), 4612-4624. [CrossRef]

- Gabor, M. R., Blaga, P., & Matis, C. (2019). Supporting employability by a skills assessment innovative tool—Sustainable transnational insights from employers. Sustainability, 11(12), 3360. [CrossRef]

- Matteson, M. L., Anderson, L., & Boyden, C. (2016). " Soft skills": A phrase in search of meaning. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 16(1), 71-88. [CrossRef]

- Vasile, V. Crisis impact on employment and mobility model of the Romanian university graduates. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 3, 315–324. [CrossRef]

- Neștian, Ș. A., Vodă, A. I., Tiță, S. M., Guță, A. L., & Turnea, E. S. (2021). Does individual knowledge management in online education prepare business students for employability in online businesses?. Sustainability, 13(4), 2091. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).