Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

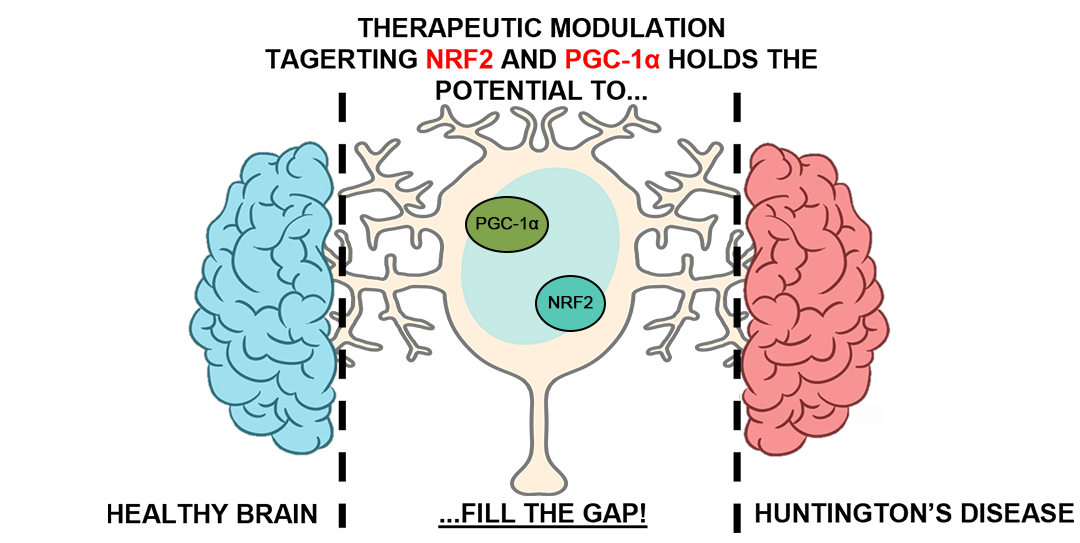

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. HD Pathogenesis

2.1. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

2.2. Neuroinflammation

3. Role of NRF2 and PGC1a

3.1. NRF2

3.2. PGC-1α

3.3. INTERACTION BETWeen NRF2 and PGC-1α

4. Antioxidant Therapeutic Strategies Involving NRF2 and PGC-1α Signaling

4.1. Modulation of NRF2 as a Therapy for HD

4.2. Modulation of PGC-1α as a Therapy for HD

| THERAPEUTIC STRATEGY | HD MODEL | NRF2activation | PGC-1αactivation | Effects | REF. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naringin | 3-NPA-stressed rats | V | Reduced neuroinflammatory markers and oxidative damage | [96] | |

| 3-NPA-stressed PC12 cells | V | Reduced 3-NPA-induced neurotoxicity | [52] | ||

| Protopanaxatriol | 3-NPA-stressed rats | V | Reduced neuronal injury | [97] | |

| 6-Shogaol | 3-NPA-stressed rats | V | Improved behavior and biochemical indices with restored levels of neurotransmitters and decreased neuroinflammatory molecules | [98] | |

| CDDO-MA | 3-NPA-stressed rats | V | Reduced neuronal injury | [100] | |

| CDDO-EA | N171-82Q mice | V | Improved motor performance and increased neuronal survival in striatum | [94] | |

| CDDO-TFA | N171-82Q mice | V | Improved motor performance and increased neuronal survival in striatum | [94] | |

| Azilsartan | 3-NPA-stressed rats | V | Improved motor function, restored neurotransmitter balance, and reduced inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis | [102] | |

| Cysteamine | Mouse primary neurons and human iPSCs | V | Reduced oxidative stress and neuroprotection | [103] | |

| Human patients | V | (Ongoing study) | NCT02101957 | ||

| DMF | YAC128 and R6/2 mice | V | improvements in muscle function, stabilization of body weight, and a marked reduction in neuronal loss | [9] | |

| Resveratrol | Human patients | V | (Unpublished results) | NCT02336633 | |

| Striatal and cortical neurons from YAC128 mice, Human lymphoblasts, and YAC128 mice | V | Rescued mitochondrial membrane potential and respiratory activity with TFAM upregulation | [123] | ||

| EGCG | Human patients | V | (Unpublished results) | NCT01357681 | |

| PGC-1α overexpression | N171-82Q mice | V | Improved neurological function and TFEB-mediated eradication of mHtt aggregates in the brain | [79] | |

| R6/2 mice | V | Halted striatal degeneration | [110] | ||

| Fenofibrate | 3-NPA-stressed rats | V | PPARγ-mediated enhanced mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and biogenesis. | [111] | |

| Human patients | V | Improved motor and cognitive symptoms | NCT03515213 | ||

| Rolipram | Quinolinic acid-stressed rats | V | Antidepressant and neuroprotective effects | [117] | |

| R6/2 mice | V | Neuroprotective effects | [118] | ||

| R6/2 mice | V | Improved motor functions and neuroprotection | [119] | ||

| SIRT1 overexpression | N171-82Q mice | V | Improved metabolism and neuroprotection, decreased brain atrophy | [124] | |

| R6/2 mice | V | Improves survival, neuropathology and neutrophins levels | [125] | ||

| Viniferin | Striatal cells and primary cortical neurons from HD mice, N63-148Q PC12, and N2A cells | V | SIRT3-dependent neuroprotection | [126] | |

| Rosiglitazone | Striatal cells from HD mice | V | Reduced mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress | [127] | |

| Benzafibrate | R6/2 mice | V | Improved behavior and survival, decreased striatal atrophy and oxidative stress | [128] |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ross, C.A.; Tabrizi, S.J. Huntington’s Disease: From Molecular Pathogenesis to Clinical Treatment. The Lancet Neurology 2011, 10, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Egidio, F.; Castelli, V.; Cimini, A.; d’Angelo, M. Cell Rearrangement and Oxidant/Antioxidant Imbalance in Huntington’s Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColgan, P.; Tabrizi, S.J. Huntington’s Disease: A Clinical Review. European Journal of Neurology 2018, 25, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, A.; Mahjoub, Y.; Shaver, L.; Pringsheim, T. Prevalence and Incidence of Huntington’s Disease: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Movement Disorders 2022, 37, 2327–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendia, I.; Michalska, P.; Navarro, E.; Gameiro, I.; Egea, J.; León, R. Nrf2-ARE Pathway: An Emerging Target against Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2016, 157, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, A.; Moaddel, R. A Pilot Proteomic Analysis of Huntington’s Disease by Functional Capacity. Brain Sci 2025, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorolla, M.A.; Rodríguez-Colman, M.J.; Vall-llaura, N.; Tamarit, J.; Ros, J.; Cabiscol, E. Protein Oxidation in Huntington Disease. BioFactors 2012, 38, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, P.; Lattanzi, R.; Severini, C.; Saso, L. Nrf2 Pathway in Huntington’s Disease (HD): What Is Its Role? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 15272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellrichmann, G.; Petrasch-Parwez, E.; Lee, D.-H.; Reick, C.; Arning, L.; Saft, C.; Gold, R.; Linker, R.A. Efficacy of Fumaric Acid Esters in the R6/2 and YAC128 Models of Huntington’s Disease. PLoS One 2011, 6, e16172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamwal, S.; Blackburn, J.K.; Elsworth, J.D. PPARγ/PGC1α Signaling as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Pharmacol Ther 2021, 219, 107705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccato, C.; Cattaneo, E. Huntington’s Disease. In Neurotrophic Factors; Lewin, G.R., Carter, B.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-45106-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizi, S.J.; Flower, M.D.; Ross, C.A.; Wild, E.J. Huntington Disease: New Insights into Molecular Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Opportunities. Nat Rev Neurol 2020, 16, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, R.J.; Tong, Y. Proteostasis in Huntington’s Disease: Disease Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2018, 39, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Yang, J. Age- and Disease-related Autophagy Impairment in Huntington Disease: New Insights from Direct Neuronal Reprogramming. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Egidio, F.; Castelli, V.; d’Angelo, M.; Ammannito, F.; Quintiliani, M.; Cimini, A. Brain Incoming Call from Glia during Neuroinflammation: Roles of Extracellular Vesicles. Neurobiology of Disease 2024, 106663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.H. Increased Mitochondrial Fission and Neuronal Dysfunction in Huntington’s Disease: Implications for Molecular Inhibitors of Excessive Mitochondrial Fission. Drug discovery today 2014, 19, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.E.; Cirincione, A.B.; Jimenez-Torres, A.C.; Zhu, J. The Impact of Neurotransmitters on the Neurobiology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garret, M.; Du, Z.; Chazalon, M.; Cho, Y.H.; Baufreton, J. Alteration of GABAergic Neurotransmission in Huntington’s Disease. CNS Neurosci Ther 2018, 24, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Arellano, A.; Tejeda-Guzmán, C.; Lorca-Ponce, E.; Palma-Tirado, L.; Mantellero, C.A.; Rojas, P.; Missirlis, F.; Castro, M.A. Huntington’s Disease Leads to Decrease of GABA-A Tonic Subunits in the D2 Neostriatal Pathway and Their Relocalization into the Synaptic Cleft. Neurobiol Dis 2018, 110, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Yan, Y.-P.; Zhou, R.; Lou, H.-F.; Rong, Y.; Zhang, B.-R. Soluble N-Terminal Fragment of Mutant Huntingtin Protein Impairs Mitochondrial Axonal Transport in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. Neurosci Bull 2013, 30, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yablonska, S.; Ganesan, V.; Ferrando, L.M.; Kim, J.; Pyzel, A.; Baranova, O.V.; Khattar, N.K.; Larkin, T.M.; Baranov, S.V.; Chen, N.; et al. Mutant Huntingtin Disrupts Mitochondrial Proteostasis by Interacting with TIM23. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 16593–16602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ratan, R.R. Oxidative Stress and Huntington’s Disease: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. J Huntingtons Dis 2016, 5, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adegbuyiro, A.; Stonebraker, A.R.; Sedighi, F.; Fan, C.K.; Hodges, B.; Li, P.; Valentine, S.J.; Legleiter, J. Oxidation Promotes Distinct Huntingtin Aggregates in the Presence and Absence of Membranes. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 1517–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Sharma, P.; Singh, T.G. Mechanistic Insights on the Role of Nrf-2 Signalling in Huntington’s Disease. Neurol Sci 2025, 46, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johri, A.; Chandra, A.; Flint Beal, M. PGC-1α, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Huntington’s Disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2013, 62, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Uyeda, A.; Muramatsu, R. Central Nervous System Regeneration: The Roles of Glial Cells in the Potential Molecular Mechanism Underlying Remyelination. Inflammation and Regeneration 2022, 42, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.-H. Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders: The Roles of Microglia and Astrocytes. Translational Neurodegeneration 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, G.; Colasanti, A.; Kalk, N.; Owen, D.; Scott, G.; Rabiner, E.A.; Gunn, R.N.; Lingford-Hughes, A.; Malik, O.; Ciccarelli, O.; et al. 11C-PBR28 and 18F-PBR111 Detect White Matter Inflammatory Heterogeneity in Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2017, 58, 1477–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Barres, B.A. Reactive Astrocytes: Production, Function, and Therapeutic Potential. Immunity 2017, 46, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palpagama, T.H.; Waldvogel, H.J.; Faull, R.L.M.; Kwakowsky, A. The Role of Microglia and Astrocytes in Huntington’s Disease. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2019, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, A.D.; Kaltenbach, L.S.; Lo, D.C.; Harry, G.J. Activated Microglia Proliferate at Neurites of Mutant Huntingtin-Expressing Neurons. Neurobiol Aging 2012, 33, 621.e17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.P.; Denovan-Wright, E.M. Microglia-Mediated Neuron Death Requires TNF and Is Exacerbated by Mutant Huntingtin. Pharmacological Research 2024, 209, 107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpich, M.; Amini, E.; Mohamed, Z.; Azman Ali, R.; Mohamed Ibrahim, N.; Ahmadiani, A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Biogenesis in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Pathogenesis and Treatment. CNS Neurosci Ther 2017, 23, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Profumo, E.; Tucci, P.; Saso, L. A Perspective on Nrf2 Signaling Pathway for Neuroinflammation: A Potential Therapeutic Target in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Front Cell Neurosci 2022, 15, 787258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Qian, Y.; Xiao, Q. Resveratrol Regulates Microglia M1/M2 Polarization via PGC-1α in Conditions of Neuroinflammatory Injury. Brain Behav Immun 2017, 64, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Kaur, A.; Singh, T.G. Counteracting Role of Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 129, 110373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivandzade, F.; Bhalerao, A.; Cucullo, L. Cerebrovascular and Neurological Disorders: Protective Role of NRF2. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niture, S.K.; Khatri, R.; Jaiswal, A.K. Regulation of Nrf2—an Update. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2014, 66, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukutomi, T.; Takagi, K.; Mizushima, T.; Ohuchi, N.; Yamamoto, M. Kinetic, Thermodynamic, and Structural Characterizations of the Association between Nrf2-DLGex Degron and Keap1. Mol Cell Biol 2014, 34, 832–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, K.; Geng, M.; Gao, P.; Wu, X.; Hai, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Luo, L.; Hayes, J.D.; et al. RXRα Inhibits the NRF2-ARE Signaling Pathway through a Direct Interaction with the Neh7 Domain of NRF2. Cancer Res 2013, 73, 3097–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, M.; Patil, J.; D’Angelo, B.; Weber, S.G.; Mallard, C. NRF2-Regulation in Brain Health and Disease: Implication of Cerebral Inflammation. Neuropharmacology 2014, 79, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-I. MAPK-ERK Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-J.; Jang, M.; Lee, M.J.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, S.K.; Jang, D.S.; Cho, I.-H. Schisandra Chinensis Stem Ameliorates 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Striatal Toxicity via Activation of the Nrf2 Pathway and Inhibition of the MAPKs and NF-κB Pathways. Front Pharmacol 2017, 8, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, M.; Cho, I.-H. Sulforaphane Ameliorates 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Striatal Toxicity by Activating the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE Pathway and Inhibiting the MAPKs and NF-κB Pathways. Mol Neurobiol 2016, 53, 2619–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Choi, J.H.; Chang, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Nah, S.-Y.; Cho, I.-H. Gintonin, a Ginseng-Derived Ingredient, as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Huntington’s Disease: Activation of the Nrf2 Pathway through Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptors. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 80, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Mechanisms of Cellular Energy Sensing and Restoration of Metabolic Balance. Mol Cell 2017, 66, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, M.Z.; Tadros, M.G.; Abd-Alkhalek, H.A.; Mohamad, M.I.; Eid, D.M.; Hassan, F.E.; Elhelaly, H.; Faramawy, Y.E.; Aboul-Fotouh, S. Harmine Prevents 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Neurotoxicity in Rats via Enhancing NRF2-Mediated Signaling: Involvement of P21 and AMPK. Eur J Pharmacol 2022, 927, 175046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaré, S.; Kothari, A.; Calcutt, N.A.; Fernyhough, P. Metformin as a Potential Therapeutic for Neurological Disease: Mobilizing AMPK to Repair the Nervous System. Expert Rev Neurother 2021, 21, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, K.R.; Jones, L. Kinase Signalling in Huntington’s Disease. J Huntingtons Dis 2014, 3, 89–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.N.; Dilnashin, H.; Birla, H.; Singh, S.S.; Zahra, W.; Rathore, A.S.; Singh, B.K.; Singh, S.P. The Role of PI3K/Akt and ERK in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurotox Res 2019, 35, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.M.; Rabie, M.A.; Zaki, H.F.; Shaheen, A.M. Inhibition of Brain GTP Cyclohydrolase I Attenuates 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Striatal Toxicity: Involvement of Mas Receptor/PI3k/Akt/CREB/ BDNF Axis. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 740966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulasekaran, G.; Ganapasam, S. Neuroprotective Efficacy of Naringin on 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction through the Modulation of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in PC12 Cells. Mol Cell Biochem 2015, 409, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayed, N.H.; Fathy, N.; Kortam, M.A.; Rabie, M.A.; Mohamed, A.F.; Kamel, A.S. Vildagliptin Attenuates Huntington’s Disease through Activation of GLP-1 Receptor/PI3K/Akt/BDNF Pathway in 3-Nitropropionic Acid Rat Model. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neo, S.H.; Tang, B.L. Sirtuins as Modifiers of Huntington’s Disease (HD) Pathology. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2018, 154, 105–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naia, L.; Rego, A.C. Sirtuins: Double Players in Huntington’s Disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1852, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beura, S.K.; Dhapola, R.; Panigrahi, A.R.; Yadav, P.; Kumar, R.; Reddy, D.H.; Singh, S.K. Antiplatelet Drugs: Potential Therapeutic Options for the Management of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Med Res Rev 2023, 43, 1835–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, V.; Quinti, L.; Kim, J.; Vollor, L.; Narayanan, K.L.; Edgerly, C.; Cipicchio, P.M.; Lauver, M.A.; Choi, S.H.; Silverman, R.B.; et al. The Sirtuin 2 Inhibitor AK-7 Is Neuroprotective in Huntington’s Disease Mouse Models. Cell Rep 2012, 2, 1492–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Tecedor, L.; Chen, Y.H.; Monteys, A.M.; Sowada, M.J.; Thompson, L.M.; Davidson, B.L. Reinstating Aberrant mTORC1 Activity in Huntington’s Disease Mice Improves Disease Phenotypes. Neuron 2015, 85, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonchar, O.O.; Maznychenko, A.V.; Klyuchko, O.M.; Mankovska, I.M.; Butowska, K.; Borowik, A.; Piosik, J.; Sokolowska, I. C60 Fullerene Reduces 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Oxidative Stress Disorders and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Rats by Modulation of P53, Bcl-2 and Nrf2 Targeted Proteins. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritos, N.A.; Mastaitis, J.W.; Kokkotou, E.G.; Puigserver, P.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Maratos-Flier, E. Characterization of the Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Coactivator 1 Alpha (PGC 1alpha) Expression in the Murine Brain. Brain Res 2003, 961, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qin, Y.; Liu, B.; Gao, M.; Li, A.; Li, X.; Gong, G. PGC-1α-Mediated Mitochondrial Quality Control: Molecular Mechanisms and Implications for Heart Failure. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 871357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigserver, P.; Wu, Z.; Park, C.W.; Graves, R.; Wright, M.; Spiegelman, B.M. A Cold-Inducible Coactivator of Nuclear Receptors Linked to Adaptive Thermogenesis. Cell 1998, 92, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Lin, J.D. PGC-1 Coactivators in the Control of Energy Metabolism. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2011, 43, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, G.; Fasciolo, G.; Venditti, P. Mitochondrial Management of Reactive Oxygen Species. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several Lines of Antioxidant Defense against Oxidative Stress: Antioxidant Enzymes, Nanomaterials with Multiple Enzyme-Mimicking Activities, and Low-Molecular-Weight Antioxidants. Arch Toxicol 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Shelbayeh, O.; Arroum, T.; Morris, S.; Busch, K.B. PGC-1α Is a Master Regulator of Mitochondrial Lifecycle and ROS Stress Response. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanzione, R.; Forte, M.; Cotugno, M.; Bianchi, F.; Marchitti, S.; Busceti, C.L.; Fornai, F.; Rubattu, S. Uncoupling Protein 2 as a Pathogenic Determinant and Therapeutic Target in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases. Curr Neuropharmacol 2022, 20, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rius-Pérez, S.; Torres-Cuevas, I.; Millán, I.; Ortega, Á.L.; Pérez, S. PGC-1α, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress: An Integrative View in Metabolism. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 1452696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, J.; Lin, J.; Krauss, S.; Tarr, P.T.; Yang, R.; Newgard, C.B.; Spiegelman, B.M. Bioenergetic Analysis of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivators 1alpha and 1beta (PGC-1alpha and PGC-1beta) in Muscle Cells. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 26597–26603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Puigserver, P.; Andersson, U.; Zhang, C.; Adelmant, G.; Mootha, V.; Troy, A.; Cinti, S.; Lowell, B.; Scarpulla, R.C.; et al. Mechanisms Controlling Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Respiration through the Thermogenic Coactivator PGC-1. Cell 1999, 98, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMeekin, L.J.; Bartley, A.F.; Bohannon, A.S.; Adlaf, E.W.; van Groen, T.; Boas, S.M.; Fox, S.N.; Detloff, P.J.; Crossman, D.K.; Overstreet-Wadiche, L.S.; et al. A Role for PGC-1α in Transcription and Excitability of Neocortical and Hippocampal Excitatory Neurons. Neuroscience 2020, 435, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Huang, W.; Li, D.; Si, E.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, X. Overexpression of PGC-1α Influences Mitochondrial Signal Transduction of Dopaminergic Neurons. Mol Neurobiol 2016, 53, 3756–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanaveski, T.; Molchanova, S.; Pham, D.D.; Schäfer, A.; Pajanoja, C.; Narvik, J.; Srinivasan, V.; Urb, M.; Koivisto, M.; Vasar, E.; et al. PGC-1α Signaling Increases GABA(A) Receptor Subunit A2 Expression, GABAergic Neurotransmission and Anxiety-Like Behavior in Mice. Front Mol Neurosci 2021, 14, 588230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, H.-R.; Guo, M.-N.; Ma, S.-F.; Yun, Q.; Zhang, W.-N. Adult Conditional Knockout of PGC-1α in GABAergic Neurons Causes Exaggerated Startle Reactivity, Impaired Short-Term Habituation and Hyperactivity. Brain Res Bull 2020, 157, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Wan, R.; Yang, J.-L.; Kamimura, N.; Son, T.G.; Ouyang, X.; Luo, Y.; Okun, E.; Mattson, M.P. Involvement of PGC-1α in the Formation and Maintenance of Neuronal Dendritic Spines. Nat Commun 2012, 3, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Valenza, M.; Cui, L.; Leoni, V.; Jeong, H.-K.; Brilli, E.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Q.; Duan, W.; Reeves, S.A.; et al. Peroxisome-Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1 α Contributes to Dysmyelination in Experimental Models of Huntington’s Disease. J Neurosci 2011, 31, 9544–9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cristo, F.; Finicelli, M.; Digilio, F.A.; Paladino, S.; Valentino, A.; Scialò, F.; D’Apolito, M.; Saturnino, C.; Galderisi, U.; Giordano, A.; et al. Meldonium Improves Huntington’s Disease Mitochondrial Dysfunction by Restoring Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Coactivator 1α Expression. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 9233–9246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weydt, P.; Pineda, V.V.; Torrence, A.E.; Libby, R.T.; Satterfield, T.F.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Gilbert, M.L.; Morton, G.J.; Bammler, T.K.; Strand, A.D.; et al. Thermoregulatory and Metabolic Defects in Huntington’s Disease Transgenic Mice Implicate PGC-1alpha in Huntington’s Disease Neurodegeneration. Cell Metab 2006, 4, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunemi, T.; Ashe, T.D.; Morrison, B.E.; Soriano, K.R.; Au, J.; Roque, R.A.V.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Damian, V.A.; Masliah, E.; La Spada, A.R. PGC-1α Rescues Huntington’s Disease Proteotoxicity by Preventing Oxidative Stress and Promoting TFEB Function. Science Translational Medicine 2012, 4, 142ra97–142ra97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ar, L.S. PPARGC1A/PGC-1α, TFEB and Enhanced Proteostasis in Huntington Disease: Defining Regulatory Linkages between Energy Production and Protein-Organelle Quality Control. Autophagy 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, M.S.; Kim, W.D.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Koo, J.H.; Kim, S.G. AMPK Facilitates Nuclear Accumulation of Nrf2 by Phosphorylating at Serine 550. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2016, 36, 1931–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhry, S.; Zhang, Y.; McMahon, M.; Sutherland, C.; Cuadrado, A.; Hayes, J.D. Nrf2 Is Controlled by Two Distinct β-TrCP Recognition Motifs in Its Neh6 Domain, One of Which Can Be Modulated by GSK-3 Activity. Oncogene 2013, 32, 3765–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Numazawa, S.; Tang, H.; Tang, X.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, Z.; et al. The Crosstalk Between Nrf2 and AMPK Signal Pathways Is Important for the Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Berberine in LPS-Stimulated Macrophages and Endotoxin-Shocked Mice. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2014, 20, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, K.; Sonowal, H.; Saxena, A.; Ramana, K.V.; Srivastava, S.K. Aldose Reductase Inhibitor, Fidarestat Regulates Mitochondrial Biogenesis via Nrf2/HO-1/AMPK Pathway in Colon Cancer Cells. Cancer Lett 2017, 411, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosuru, R.; Kandula, V.; Rai, U.; Prakash, S.; Xia, Z.; Singh, S. Pterostilbene Decreases Cardiac Oxidative Stress and Inflammation via Activation of AMPK/Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway in Fructose-Fed Diabetic Rats. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2018, 32, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, H.; Lv, H.; Cheng, G.; Ci, X. Nrf2-Mediated Liver Protection by Esculentoside A against Acetaminophen Toxicity through the AMPK/Akt/GSK3β Pathway. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2016, 101, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilano, K.; Baldelli, S.; Pagliei, B.; Cannata, S.M.; Rotilio, G.; Ciriolo, M.R. P53 Orchestrates the PGC-1α-Mediated Antioxidant Response Upon Mild Redox and Metabolic Imbalance. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2013, 18, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, A.D.; Suliman, H.B.; Bartz, R.R.; Piantadosi, C.A. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Co-Activator 1-α as a Critical Co-Activator of the Murine Hepatic Oxidative Stress Response and Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Staphylococcus Aureus Sepsis*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-I.; Kim, H.-J.; Park, J.-S.; Kim, I.-J.; Bae, E.H.; Ma, S.K.; Kim, S.W. PGC-1α Attenuates Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Apoptotic Cell Death by Upregulating Nrf-2 via GSK3β Inactivation Mediated by Activated P38 in HK-2 Cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, S.; Aquilano, K.; Ciriolo, M.R. Punctum on Two Different Transcription Factors Regulated by PGC-1α: Nuclear Factor Erythroid-Derived 2-like 2 and Nuclear Respiratory Factor 2. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2013, 1830, 4137–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, Y.; Zheng, M.; Kim, H.J.; Uddin, Md.J.; Kim, S.-K.; Chen, Y.; Park, J.; Cho, G.J.; Ryter, S.W.; Chung, H.T. Cilostazol Attenuates Murine Hepatic Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury via Heme Oxygenase-Dependent Activation of Mitochondrial Biogenesis. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2015, 309, G21–G29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, S.A.; Long, M.; Wondrak, G.T.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, D.D. Nrf2 Modulates Contractile and Metabolic Properties of Skeletal Muscle in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Atrophy. Experimental Cell Research 2013, 319, 2673–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hota, K.B.; Hota, S.K.; Chaurasia, O.P.; Singh, S.B. Acetyl-L-Carnitine-Mediated Neuroprotection during Hypoxia Is Attributed to ERK1/2-Nrf2-Regulated Mitochondrial Biosynthesis. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stack, C.; Ho, D.; Wille, E.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Williams, C.; Liby, K.; Sporn, M.; Dumont, M.; Beal, M.F. Triterpenoids CDDO-Ethyl Amide and CDDO-Trifluoroethyl Amide Improve the Behavioral Phenotype and Brain Pathology in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2010, 49, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, M.J.; Jakel, R.J.; Johnson, D.A.; Chan, K.; Kan, Y.W.; Johnson, J.A. Protection from Mitochondrial Complex II Inhibition in Vitro and in Vivo by Nrf2-Mediated Transcription. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, K.; Sudhandiran, G. Naringin Modulates Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Neurodegeneration through the Activation of Nuclear Factor-Erythroid 2-Related Factor-2 Signalling Pathway. Neuroscience 2012, 227, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, J.; Wen, Z.; Xia, C.; Mou, Z.; Wang, Z.; He, W.; et al. Protopanaxtriol Protects against 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Oxidative Stress in a Rat Model of Huntington’s Disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2015, 36, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambi, E.J.; Alamri, A.; Afzal, M.; Al-Abbasi, F.A.; Al-Qahtani, S.D.; Almalki, N.A.R.; Bawadood, A.S.; Alzarea, S.I.; Sayyed, N.; Kazmi, I. 6-Shogaol against 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Huntington’s Disease in Rodents: Based on Molecular Docking/Targeting pro-Inflammatory Cytokines/NF-κB-BDNF-Nrf2 Pathway. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0305358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Roon-Mom, W.M.C.; Pepers, B.A.; ’t Hoen, P.A.C.; Verwijmeren, C.A.C.M.; den Dunnen, J.T.; Dorsman, J.C.; van Ommen, G.B. Mutant Huntingtin Activates Nrf2-Responsive Genes and Impairs Dopamine Synthesis in a PC12 Model of Huntington’s Disease. BMC Mol Biol 2008, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Thomas, B.; Chaturvedi, R.K.; Kiaei, M.; Wille, E.J.; Liby, K.T.; Williams, C.; Royce, D.; Risingsong, R.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects of the Triterpenoid, CDDO Methyl Amide, a Potent Inducer of Nrf2-Mediated Transcription. PLoS One 2009, 4, e5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, O.A.; Dedeoglu, A.; Ferrante, R.J.; Jenkins, B.G.; Ferrante, K.L.; Thomas, M.; Friedlich, A.; Browne, S.E.; Schilling, G.; Borchelt, D.R.; et al. Creatine Increase Survival and Delays Motor Symptoms in a Transgenic Animal Model of Huntington’s Disease. Neurobiol Dis 2001, 8, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, H.A.; Sayed, R.H.; Eid, N.I.; El-Sayeh, B.M. Azilsartan Attenuates 3-Nitropropinoic Acid-Induced Neurotoxicity in Rats: The Role of IĸB/NF-ĸB and KEAP1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathways. Neurochem Res 2024, 49, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbez, N.; Roby, E.; Akimov, S.; Eddings, C.; Ren, M.; Wang, X.; Ross, C.A. Cysteamine Protects Neurons from Mutant Huntingtin Toxicity. Journal of Huntington’s Disease 2019, 8, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.D.; Snyder, S.H. Therapeutic Applications of Cysteamine and Cystamine in Neurodegenerative and Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassab, L.Y.; Abbas, S.S.; Mohammed, R.A.; Abdallah, D.M. Dimethyl Fumarate Abrogates Striatal Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Experimentally Induced Late-Stage Huntington’s Disease: Focus on the IRE1α/JNK and PERK/CHOP Trajectories. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1133863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkutewicz, I. Dimethyl Fumarate: A Review of Preclinical Efficacy in Models of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Eur J Pharmacol 2022, 926, 175025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, S.A.; Ardizzone, A.; Paterniti, I.; Esposito, E.; Campolo, M. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Nrf2 Inducer Dimethyl Fumarate in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrdova, E.; Giovannoni, G.; Gold, R.; Fox, R.J.; Kappos, L.; Phillips, J.T.; Okwuokenye, M.; Marantz, J.L. Effect of Delayed-Release Dimethyl Fumarate on No Evidence of Disease Activity in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Integrated Analysis of the Phase III DEFINE and CONFIRM Studies. Eur J Neurol 2017, 24, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, N.E.; Farina, M.; Tucci, P.; Saso, L. The Role of the NRF2 Pathway in Maintaining and Improving Cognitive Function. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jeong, H.; Borovecki, F.; Parkhurst, C.N.; Tanese, N.; Krainc, D. Transcriptional Repression of PGC-1alpha by Mutant Huntingtin Leads to Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neurodegeneration. Cell 2006, 127, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhateja, D.K.; Dhull, D.K.; Gill, A.; Sidhu, A.; Sharma, S.; Reddy, B.V.K.; Padi, S.S.V. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-α Activation Attenuates 3-Nitropropionic Acid Induced Behavioral and Biochemical Alterations in Rats: Possible Neuroprotective Mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol 2012, 674, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.; Tabrizi, S.J.; Wild, E.J. Huntington’s Disease Clinical Trials Update: September 2024. Journal of Huntington’s Disease 2024, 13, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurcau, A.; Jurcau, M.C. Therapeutic Strategies in Huntington’s Disease: From Genetic Defect to Gene Therapy. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, V.; Zhang, H.; O’Donnell, J.M.; Xu, Y.; Yin, X. The Antidepressant- and Anxiolytic-like Effects of Resveratrol: Involvement of Phosphodiesterase-4D Inhibition. Neuropharmacology 2019, 153, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-J.; Ahmad, F.; Philp, A.; Baar, K.; Williams, T.; Luo, H.; Ke, H.; Rehmann, H.; Taussig, R.; Brown, A.L.; et al. Resveratrol Ameliorates Aging-Related Metabolic Phenotypes by Inhibiting cAMP Phosphodiesterases. Cell 2012, 148, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Mix, E.; Winblad, B. The Antidepressant and Antiinflammatory Effects of Rolipram in the Central Nervous System. CNS Drug Rev 2001, 7, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarch, Z.; Giampà, C.; Patassini, S.; Martorana, A.; Bernardi, G.; Fusco, F.R. Beneficial Effects of Rolipram in a Quinolinic Acid Model of Striatal Excitotoxicity. Neurobiol Dis 2007, 25, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarch, Z.; Giampà, C.; Patassini, S.; Bernardi, G.; Fusco, F.R. Beneficial Effects of Rolipram in the R6/2 Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. Neurobiol Dis 2008, 30, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampà, C.; Middei, S.; Patassini, S.; Borreca, A.; Marullo, F.; Laurenti, D.; Bernardi, G.; Ammassari-Teule, M.; Fusco, F.R. Phosphodiesterase Type IV Inhibition Prevents Sequestration of CREB Binding Protein, Protects Striatal Parvalbumin Interneurons and Rescues Motor Deficits in the R6/2 Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. Eur J Neurosci 2009, 29, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Padi, S.S.V.; Naidu, P.S.; Kumar, A. Effect of Resveratrol on 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Biochemical and Behavioural Changes: Possible Neuroprotective Mechanisms. Behav Pharmacol 2006, 17, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binienda, Z.K.; Beaudoin, M.A.; Gough, B.; Ali, S.F.; Virmani, A. Assessment of 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Evoked Peripheral Neuropathy in Rats: Neuroprotective Effects of Acetyl-l-Carnitine and Resveratrol. Neurosci Lett 2010, 480, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.J.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Wille, E.; Dumont, M.; Beal, M.F. Resveratrol Protects against Peripheral Deficits in a Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. Exp Neurol 2010, 225, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naia, L.; Rosenstock, T.R.; Oliveira, A.M.; Oliveira-Sousa, S.I.; Caldeira, G.L.; Carmo, C.; Laço, M.N.; Hayden, M.R.; Oliveira, C.R.; Rego, A.C. Comparative Mitochondrial-Based Protective Effects of Resveratrol and Nicotinamide in Huntington’s Disease Models. Mol Neurobiol 2017, 54, 5385–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, J.; Fu, J.; Du, L.; Jeong, H.-K.; West, T.; Xiang, L.; Peng, Q.; Hou, Z.; Cai, H.; et al. Neuroprotective Role of SIRT1 in Mammalian Models of Huntington’s Disease through Activation of Multiple SIRT1 Targets. Nat Med 2011, 18, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.E.; Cui, L.; Supinski, A.; Savas, J.N.; Mazzulli, J.R.; Yates, J.R.; Bordone, L.; Guarente, L.P.; Krainc, D. Sirt1 Mediates Neuroprotection from Mutant Huntingtin by Activation of TORC1 and CREB Transcriptional Pathway. Nat Med 2011, 18, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Jin, J.; Cichewicz, R.H.; Hageman, S.A.; Ellis, T.K.; Xiang, L.; Peng, Q.; Jiang, M.; Arbez, N.; Hotaling, K.; et al. Trans-(-)-ε-Viniferin Increases Mitochondrial Sirtuin 3 (SIRT3), Activates AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK), and Protects Cells in Models of Huntington Disease. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 24460–24472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, R.A.; Jin, Y.N.; Fuenzalida, K.; Bronfman, M.; Johnson, G.V.W. Rosiglitazone Treatment Prevents Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Mutant Huntingtin-Expressing Cells. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 25628–25637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri, A.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Hennessey, T.M.; Sharma, A.; Yang, L.; Wille, E.; Chandra, A.; Beal, M.F. Pharmacologic Activation of Mitochondrial Biogenesis Exerts Widespread Beneficial Effects in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscomi, C.; Bottani, E.; Civiletto, G.; Cerutti, R.; Moggio, M.; Fagiolari, G.; Schon, E.A.; Lamperti, C.; Zeviani, M. In Vivo Correction of COX Deficiency by Activation of the AMPK/PGC-1α Axis. Cell Metab 2011, 14, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsuga, S.; Suomalainen, A. Effect of Bezafibrate Treatment on Late-Onset Mitochondrial Myopathy in Mice. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, M.M.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Beddor, A.; Kashbour, M. Breaking Barriers in Huntington’s Disease Therapy: Focused Ultrasound for Targeted Drug Delivery. Neurochem Res 2025, 50, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Bano, N.; Ahamad, S.; Dar, N.J.; Nazir, A.; Bhat, S.A. Advances in Nanotherapeutic Strategies for Huntington’s Disease: Design, Delivery, and Neuroprotective Mechanisms. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2025, 522, 216206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwas, S.; Gulati, M.; Khursheed, R.; Arya, K.R.; Singh, S.K.; Jha, N.K.; Prasher, P.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, V. Chapter 13 - Advanced Drug Delivery Systems to Treat Huntington’s Disease: Challenges and Opportunities. In Drug Delivery Systems for Metabolic Disorders; Dureja, H., Murthy, S.N., Wich, P.R., Dua, K., Eds.; Academic Press, 2022; pp. 189–206 ISBN 978-0-323-99616-7.

- Martí-Martínez, S.; Valor, L.M. A Glimpse of Molecular Biomarkers in Huntington’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eimeren, T.; Giehl, K.; Reetz, K.; Sampaio, C.; Mestre, T.A. Neuroimaging Biomarkers in Huntington’s Disease: Preparing for a New Era of Therapeutic Development. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2023, 114, 105488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, R.G.; Neilson, L.E.; McHill, A.W.; Hiller, A.L. Dietary Fasting and Time-Restricted Eating in Huntington’s Disease: Therapeutic Potential and Underlying Mechanisms. Transl Neurodegener 2024, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Fung, W.L.A. F54 Non-Pharmacological Interventions Targeting Psychiatric Manifestations in Huntington’s Disease Patients: A Scoping Review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2018, 89, A58–A58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).