1. Introduction

The ultrastructure of chloroplasts and its dynamic features set the conditions for the operation of the photosynthetic machinery under a broad range of environmental and metabolic conditions. The structural and functional plasticity of thylakoid membranes (TMs) – as will be emphasized in this review – are largely determined by their lipid phase behavior. Recent data on lipid polymorphism of TMs, besides leading to an extension of the ‘standard’ fluid mosaic membrane model (Singer and Nicolson 1972), may give new insights into the mechanism of light-energy conversion in plant chloroplasts.

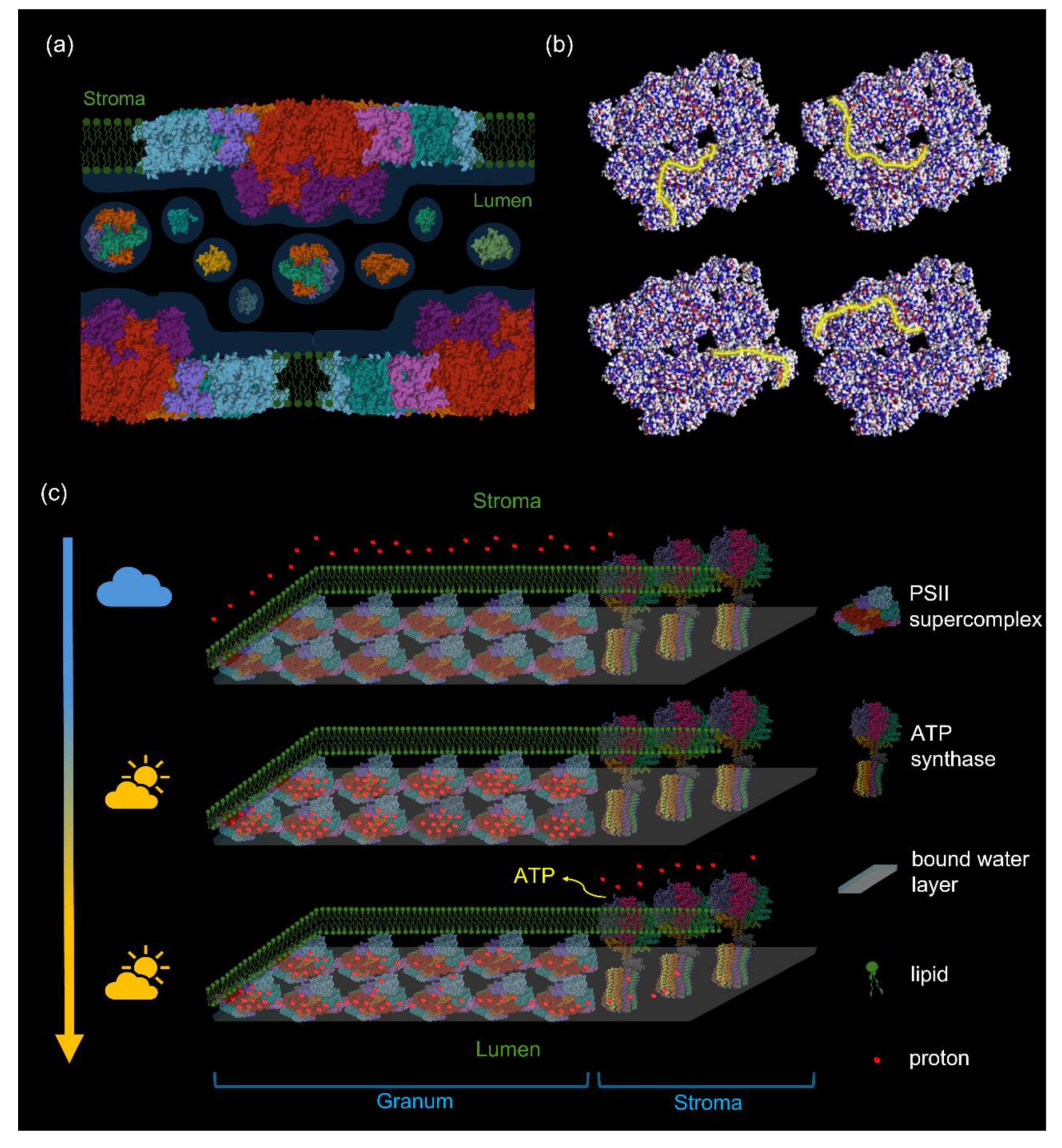

TMs in all oxygenic photosynthetic organisms “appear as an ensemble of flat sacs with highly curved edges” (Perez-Boerema et al. 2024). In plant chloroplasts, they reside in the aqueous matrix, called the stroma. They are constituted of grana, stacked piles of cylindrical layers of TMs with 400–600 nm in diameter, and stroma lamellae, unstacked TMs, which are helically wound around the grana and are connected to them through narrow slits (Mustárdy and Garab 2003). Neighboring granum-stroma TM assemblies are also coupled to each other (Bussi et al. 2019). By this means, the intricate 3D TM network system forms a single continuous membrane which encloses a contiguous interior aqueous phase, the lumen.

Plant TMs accommodate the two photosystems, PSII and PSI, along with their light-harvesting antenna complexes, LHCII and LHCI, respectively. The stacked regions are enriched in PSII-LHCII supercomplexes, which, under certain conditions, may form large often semi-crystalline arrays (Dekker and Boekema 2005, Wietrzynski et al. 2024); these supercomplexes display long-range chiral order both in vitro and in vivo (Garab 2014). PSI-LHCI and the ATP synthase are located in the stroma lamellae. Additional components of the light-energy converting machinery, the cytochrome b6f complex (cyt b6f) and the plastoquinone molecules are, respectively, embedded and shuttling in the lipid bilayer. Further constituents of the linear electron transport chain – the oxygen evolving complex, plastocyanin, ferredoxin and the ferredoxin:NADP oxidoreductase – are found in the aqueous phases of TMs. Water-soluble proteins also include the lumenal and stromal-side lipocalin-like photoprotective enzymes of the xanthophyll cycle, violaxanthin de-epoxidase (VDE) and zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZEP), respectively (Goss and Latowski 2020). In general, the bilayer is densely packed by membrane proteins and the inter-thylakoidal and stroma space and the lumen are also crowded with proteins (Kana et al. 2009, Kirchhoff et al. 2011, Gollan et al. 2021, Farci and Schröder 2023).

The operation of the electron transport system and the associated proton transport generate an energized state, proton-motive force (pmf) or ΔμH+, consisting of a transmembrane electric potential gradient and a ΔpH. Generation of pmf and its chemiosmotic utilization (Mitchell, 1966) are based on the capability of TMs of insulating the inner aqueous phase from the outer aqueous phase. This is warranted by organizing the bulk lipid molecules into bilayer structures, which is the basis of the ‘standard’ fluid-mosaic membrane model (Singer and Nicolson 1972). Lipid bilayers display low permeability to water and most water-soluble molecules and to ions, and protons, in particular (Miyamoto and Thompson 1967, Deamer and Bramhall 1986).

However, the organization of TM lipids into bilayer structures is not straightforward because only about half of the TM lipids – digalactosyldiacylglycerol (~25–30%), sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol (~10–15%) and phosphatidylglycerol (PG, ~10–15%) – are capable of spontaneously forming bilayers; the major lipid species of TMs, monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG, ~50%) (Boudière et al. 2014), is a non-bilayer lipid (Williams 1998). Non-bilayer lipids, because of their conical shapes (Israelachvili 2011), are not capable of self-assembling into bilayers. Lipid mixtures containing high concentrations of lipids with non-cylindrical geometry tend to form non-bilayer structures, such as inverted hexagonal (HII) or cubic phases or assemble into small micelles. A deeper conflict with the ‘standard’ model is that functional plant TMs contain in large quantities non-bilayer lipid assemblies (Krumova et al. 2008a, Garab et al. 2017, Garab et al. 2022).

The high abundance of MGDG and the co-existence of bilayer and non-bilayer structures in TMs pose perplexing questions regarding their roles in the mechanism of energy conversion. Furthermore, it is now well established that, beside the well-known fact that about half of the lipids of the inner mitochondrial membranes (IMMs) are non-bilayer lipids (phosphatidylethanolamine, ~34%; cardiolipin. ~18%) (Harwood 1985), functional IMMs also contain non-bilayer lipid phases (Gasanov et al. 2018). The polymorphic phase behavior of TMs and IMMs was recently reviewed (Garab et al. 2022), but the origin of different lipid phases in terms of structural entities remained elusive.

Data obtained in the past three years, on isolated plant TMs and subchloroplast particles, now allow us to provide a model that locates the different lipid phases in the chloroplast ultrastructure. Here, we show that the required bilayer organization of TMs and the high abundance of MGDG and non-bilayer lipid phases can be reconciled with each other – by taking into account physical mechanisms that deviate from the original form of chemiosmotic theory. Further, we set experimentally testable hypotheses on the roles of lipid polymorphism in the energization of TMs and its utilization for ATP synthesis – in the spirit of John Green: “as you learn, you don’t really get answers; you just get better questions”.

2. Lipid Polymorphism of Thylakoid Membranes and Subchloroplast Particles

Observations in the 1980s that isolated TM lipid mixtures assemble into non-bilayer structures suggested the possibility that similar phases could be formed in TMs; however, it was concluded that „non-bilayer configurations were difficult to reconcile with the need to maintain a stable semipermeable membrane system” (Gounaris et al. 1986). Indeed, the occurrence of HII phase, as identified by freeze-fracture electron microscopy (FF-EM), was only rarely observed; it required special conditions, e.g. exposure of TMs to 40 °C, addition of co-solutes (cf. Williams 1998), days-long storage at 5 °C (Semenova 1999), or isolating TMs from low-light grown plants (Kirchhoff et al. 2007).

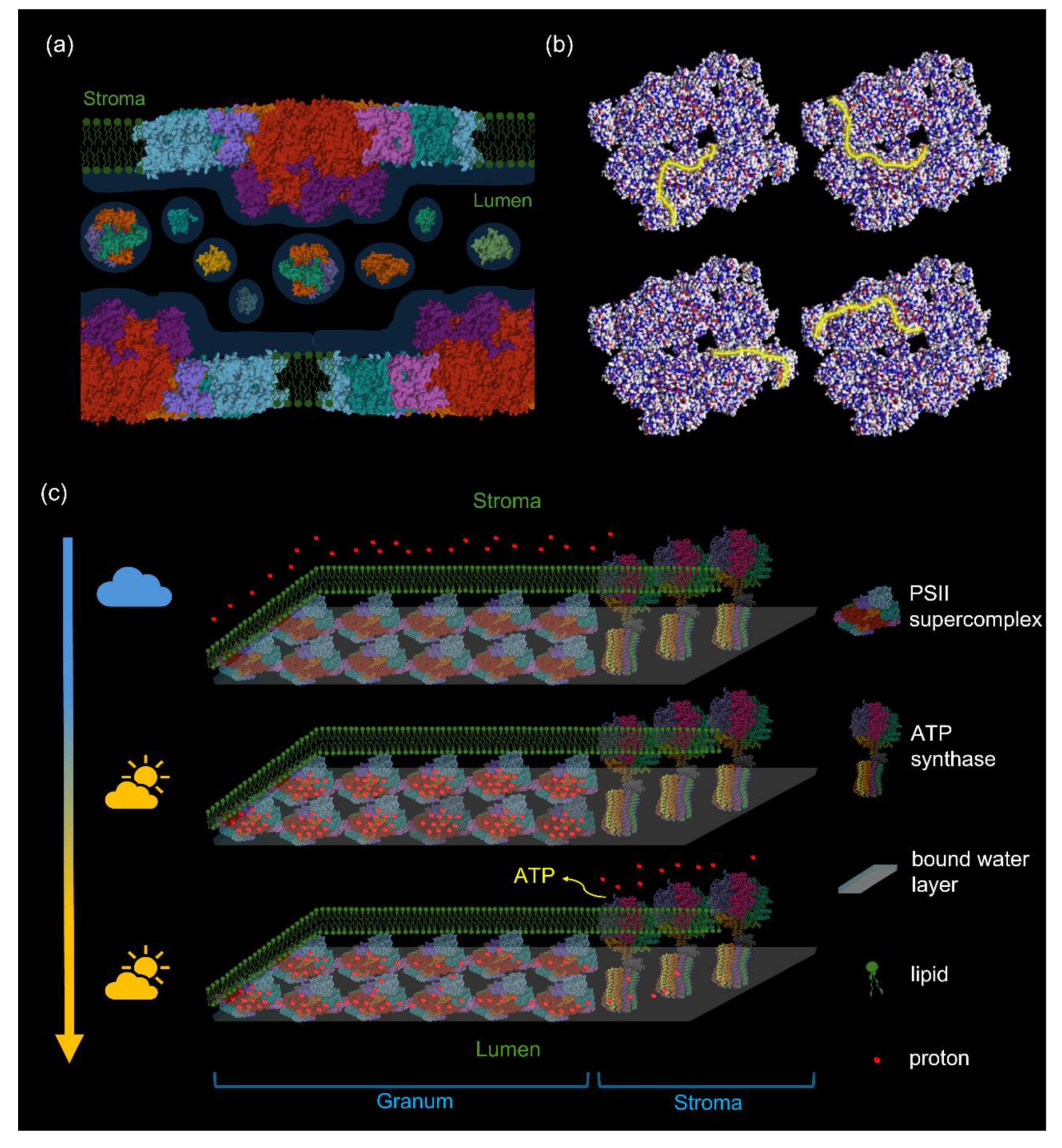

The first evidence that fully functional isolated intact TMs contain non-bilayer lipid phases was presented by (Krumova et al. 2008a) using

31P-NMR spectroscopy (see

Figure 1a). Earlier, co-existence of the bilayer and non-bilayer phases was observed on lyophilized and TRIS-treated membranes suspended in D

2O (Harańczyk et al. 1995). In agreement with

31P-NMR spectroscopy, time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy of Merocyanine-540 stained TMs also revealed different physico-chemical environments of the lipid molecules (Krumova et al. 2008b, Garab et al. 2017, Kotakis et al. 2018). (For a short overview of different techniques that can be used to monitor lipid polymorphism and lipid phase transitions in native membranes and in lipid model systems, see Supplementary Information.)

It has now been thoroughly documented that plant TMs, in addition to the bilayer (L, lamellar) phase, contain an H

II phase and (at least) two isotropic phases. This is illustrated in

Figure 1b.

Via employing 31P-NMR spectroscopy on isolated granum and stroma TM preparations (Dlouhý et al. 2021a), it has also been demonstrated that the lipid polymorphism of TMs is not correlated with the lateral heterogeneity of proteins. It has also been clarified that no SAXS signature of the HII phase could be discerned (Dlouhý et al. 2021b). The lack of long-range order of lipid molecules was explained by the low, 0.25-0.30, lipid-to-protein molar ratios of the samples, i.e. by the high protein density of the sample.

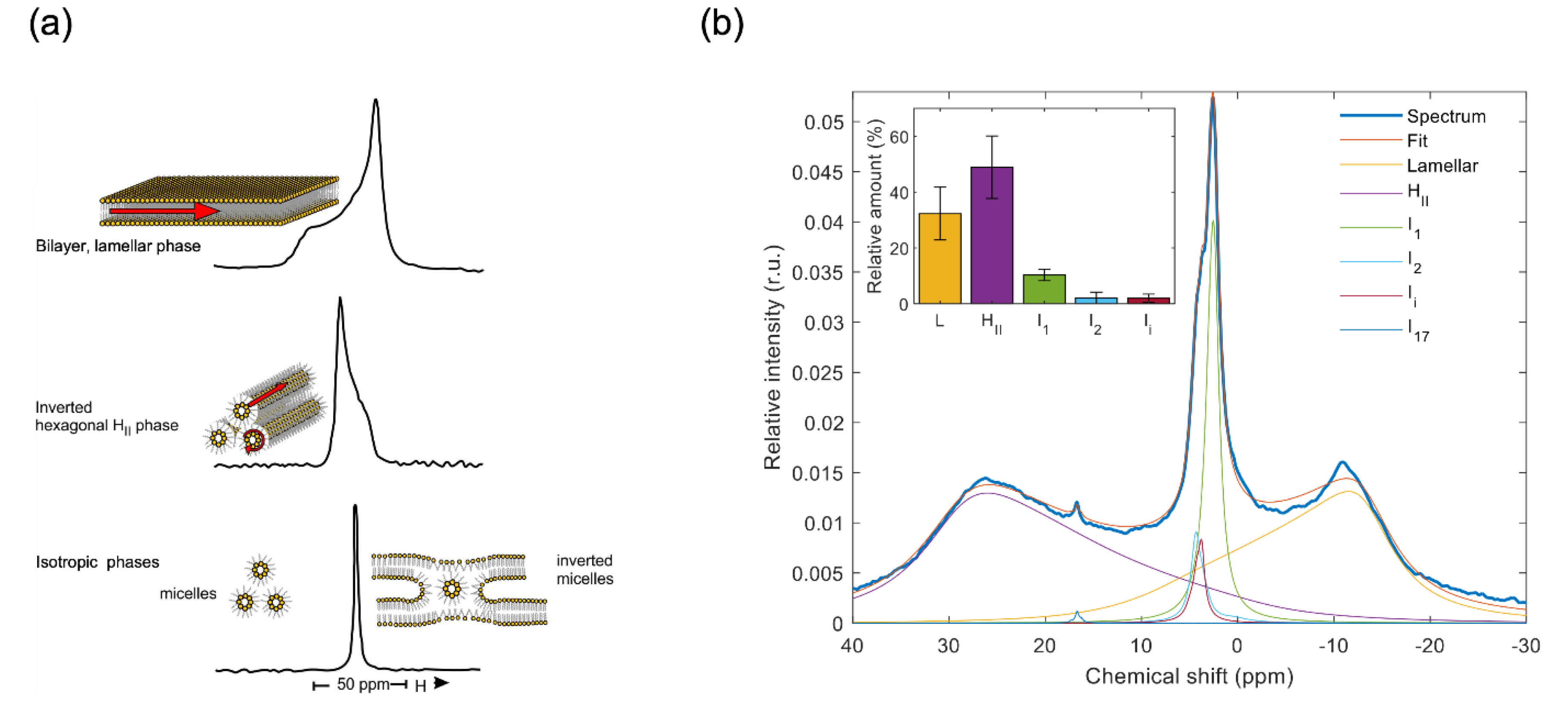

Recently, we also fingerprinted the lipid phase behavior of the stacked PSII membrane pairs (BBY particles) (Böde et al. 2024a) and the marginal region (MR) of grana (Böde et al. 2024b). The

31P-NMR spectra and ultrastructural positions of all subchloroplast particles are displayed in

Figure 2. This gallery also depicts the plastoglobuli (Dlouhý et al. 2022), which, however, contain only trace amounts of thylakoid lipids, and their proposed lipid exchange mechanism with TMs (Kirchhoff 2019) might thus be very slow.

It is evident that all membranous subchloroplast particles exhibit intense L phases; but this phase is absent in MR, probably because of the lack of supercomplexes that would stabilize the bilayer (Böde et al. 2024b), see also (Koochak et al. 2019). The HII phase was absent in BBY and MR. In contrast, all samples exhibited sharp isotropic 31P-NMR peaks with high amplitudes – indicating the participation of a large number of highly mobile lipid molecules in the corresponding structural entities.

3. Lipid Phases in Distinct Domains of Thylakoid Membranes

3.1. Lamellar Phase

In perfect harmony with all that we know about the role of bilayer organization of the bulk lipid molecules, 31P-NMR spectroscopy and electrochromic shift absorbance transient measurements performed under comparable conditions revealed close correlation between the weakening of the bilayer signature of TMs and the increased permeability of membranes (Ughy et al. 2019). Furthermore, the insulation capability of TMs was found to be very sensitive to Phospholipase A1 (PLA1) (Dlouhý et al. 2022). The virtually immediate effect of this lipase on TMs was the acceleration of the decay of the electrochromic shift absorbance transient, an effect which resembled that of ionophores (Witt 1979). These data indicate an easy access of PLA1 to the bilayer and show that the energized state of TMs can be abolished by hydrolyzing the minor lipid PG. In other terms, by ‘punching a hole’ in the bilayer the TM becomes permeable to ions – corroborating the pivotal role of the bilayer organization of lipids in membrane energization. However, as it will be emphasized in paragraphs below, the bilayer of TMs must not be portrayed as large sheets embedding (or ‘scaffolds’ holding) the intrinsic proteins – but rather as a ‘patchwork’ of lipids that are enclosed between the densely packed supercomplexes; further, as it will also be stressed below, the insulation capability of bilayers formed by TM lipids is inferior compared to bilayers composed of pure bilayer lipids.

3.2. Isotropic Phases

Regarding the I phases, we obtained important information by using WGL (wheat germ lipase), which selectively destroyed the I phases of TMs – with no or very little effect on the L and HII phases and virtually none on the structural and functional parameters of the photosynthetic machinery (Dlouhý et al. 2022). These data clearly indicated that the molecular assemblies responsible for the I phases were to be found in TM subdomains outside the protein-rich bilayer area. I-phase lipids were proposed to be involved in the fusions and junctions of TMs (Garab et al. 2017, Garab et al. 2022).

Experimental evidence for I-phase-mediated membrane fusion was provided by using BBY: WGL disassembled the large sheets of the laterally fused stacked PSII membrane pairs (Böde et al. 2024a) (

Figure 3). It might thus be inferred that I phase(s) – together with other key elements (see

Section 4) – aid(s) the self-assembly and plasticity of TMs. Chloroplasts contain regions with fusion and fission of membranes of marked dynamic features (Nevo et al. 2012). It is interesting to note here that I phases are present in all subcompartments of TMs and – as shown by electron microscopy and tomography data (Dlouhý et al. 2021b, Böde et al. 2024a, Böde et al. 2024b) – all of these samples form interwoven, multiply fused structures. In this context, de-etiolation processes are of great interest – during which the paracrystalline tubular prolamellar body is transformed into a lamellar system (Solymosi and Schoefs 2010, Kowalewska et al. 2019, Sandoval-Ibáñez et al. 2021, Liang et al. 2022, Wietrzynski et al. 2024).

It is to be noted here that the isotropic signal in MR might, in principle, originate from highly curved bilayers (Cullis and de Kruijff 1979). However, given the fact that intense I phases are present in all fractions, highly curved bilayers alone would not explain the occurrence of I phase (see also Krumova et al. 2008a). Also, the close correlation between the diminished insulation capability of membranes and the enhanced I phase(s), at the expense of the L phase, (Ughy et al. 2019; see 3.1) argue against well sealed bilayer structures in the MR.

In broad agreement with earlier findings on model systems (Latowski et al. 2002), an enhanced isotropic phase was also found to be associated with the activity of VDE (Dlouhý et al. 2020). This is envisioned to be formed in the lumenal phase (

Figure 4). It is unclear whether or not ZEP on the stromal side forms an I phase similar to that of VDE in the lumen.

3.3. HII Phase

Unexpectedly, we found that Trypsin and Proteinase K selectively suppressed the HII phase. At low and moderate concentrations, these proteinases destroyed the HII phase with only minor or no effect on the other lipid phases (Dlouhý et al. 2022) – showing that, similarly to the I phases, the structural entity responsible for this phase is located in (a) distinct subdomain(s) of TMs. Since, these proteases selectively hydrolyze peptide bonds exposed to the stromal side of TMs (Karnauchov et al. 1997), it has been concluded that HII phase is given rise by a fraction of TM lipids surrounding or encapsulating (a) stroma-side protein(s) or polypeptide(s). Indeed, BBY particles, containing no stroma-exposed proteins, possess no HII phase. It is also interesting to note that the highly curved marginal region, which contains the Trypsin-sensitive CURT1 protein, also does not give rise to this phase (Böde et al. 2024b). This renders our hypothesis (Dlouhý et al. 2022) about the participation of CURT1 protein in HII phase highly unlikely. The identity of the protein(s) and/or polypeptide(s) that is (are) associated with lipids displaying HII phase remain(s) to be determined.

4. The Dynamic Exchange Model of Thylakoid Membranes

The polymorphic lipid phase behavior of TMs is interpreted within the frameworks of the Dynamic Exchange Model (DEM), an extension of the fluid-mosaic membrane model. DEM postulates the coexistence of bilayer and non-bilayer phases and their dynamic equilibrium, and a self-regulatory mechanism that safeguards the high protein-to-lipid ratios in energy converting membranes (Garab et al. 2000, Garab et al. 2016). DEM has been based on: (i) the observation that MGDG can be forced by LHCII to form a bilayer membrane (Simidjiev et al. 2000); and (ii) the ability of lipid mixtures possessing high non-bilayer propensity to segregate out from the bilayer (Seddon and Templer 1995). (Garab et al. 2022) emphasized the importance of two additional attributes of TMs that largely determine the polymorphic phase behavior of TMs: (iii) both the inner and outer aqueous phases of TMs are fully packed with proteins (Kirchhoff et al. 2011), some of which, lipocalins (or lipocalin-like proteins), such as VDE, ZEP and LCNP (Malnoë et al. 2018, Goss and Latowski 2020), are capable of binding lipid molecules; and (iv) the self-assembly and structural dynamics of TMs depend largely on the fusion of membranes and intermembrane exchange of lipids (Mustárdy et al. 2008, Bussi et al. 2019) – processes that assume the formation of non-lamellar lipid phases (Seddon and Templer 1995, Blumenthal et al. 2003). Non-bilayer lipid phases have also been proposed to play important roles in the targeting, insertion, and assembly of proteins in plastid membranes (Bruce 1998, LaBrant et al. 2018).

Biogenesis and maintenance of thylakoid membranes have been shown to be governed by vesicle-inducing protein in plastids 1 (VIPP1). These water-soluble lipid binding proteins mediate contact between thylakoids and chloroplast envelope and also play important role in maintaining integrity under high light stress (Gupta et al. 2021). These proteins (aka IM30), under certain conditions, have been shown to be capable of destabilizing the bilayer via pore formation (Junglas et al. 2022). External protein-induced pore formation may contribute to the structural dynamics of TMs and may trigger membrane fusion. The formation of holes evidently brings about the emergence of non-bilayer lipid phases. It is interesting to note that toroidal holes have recently been visualized in cardiac mitochondrial cristae near the ATP synthase (Nesterov et al. 2024).

Additionally, other proteins, such as the dynamin-like protein CrFzl from the green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, have been proposed to modulate membrane organization and stabilization through membrane remodeling (Findinier et al. 2019). Other candidates are the Plasma Membrane Fusion Protein (PMFP, AT5G42765) identified in Arabidopsis thaliana or the Tvp38/DedA Family Protein (TVPFP, AT1G22850), which show homology with other membrane contact site proteins (Friso et al. 2004, Niedermaier et al. 2020). It is equally important to emphasize the role of lipid transport between the endoplasmatic reticulum and the TMs, which is achieved by multiple mechanisms including membrane contact sites with specialized protein machinery (LaBrant et al. 2018).

In accordance with the predictions of DEM, the lipid phases of TMs have been shown to respond sensitively to changes in the physico-chemical environment of the membranes, such as the pH and the ionic strength and osmolarity of the reaction medium. The lipid phases were particularly sensitive to elevated temperatures, which diminished and often eliminated the 31P-NMR spectroscopy signature of the bilayer; at the same time, the contribution of resonances with isotropic signature increased (Krumova et al. 2008a, Dlouhý et al. 2020). It must, however, be stressed that under comparable conditions the bilayer structure was preserved, albeit with increasing the temperature the energized state, parallel with the destabilization of the bilayer, relaxed faster (Dlouhý et al. 2020). Thus, vanishing the L phase at elevated but physiologically relevant temperatures is attributed to enhanced lipid exchange between the L and I phases. In general, it appears that non-bilayer lipids lend high plasticity to TMs – in line with the notion that „the bilayer must not be too stable because that would tend to limit protein dynamics” (Bagatolli et al. 2010). However, as will be posited below, non-bilayer lipid phases in TMs may play more fundamental roles in the conversion of light energy to chemical energy.

5. Hypotheses

5.1. Sub-Compartments, Autonomy of the Granum-Stroma Assembly

We hypothesize that each individual granum-stroma unit possesses a high degree of autonomy with regards to the generation of pmf and its utilization for ATP synthesis, and that this functional sub-compartmentalization is assisted by (a) non-bilayer lipid phase(s).

According to most textbooks, the aqueous phase of a chloroplast is divided by the TM into two compartments, and that the local electric fields are “delocalized over the thylakoid membrane by ion redistribution within the inner and outer aqueous phase of the membrane” (Witt 1979). According to this picture, the pmf is generated between the two aqueous phases of TMs. However, this widely accepted simplified view should probably be modified by taking into account more recently established parameters of the ultrastructure and molecular organization of TMs.

First, we recall that each granum-stroma assembly contains all components of the light-energy-converting machinery and that interconnections between the granum and stroma membranes and between the TM layers of grana (Mustárdy and Garab 2003) allow the formation of a delocalized uniform pmf in each unit. Thus, in principle, these units are capable of producing ATP with a high degree of autonomy. On the other hand, sharing pmf between adjacent granum-stroma units may be sterically hindered. It has recently been clarified that the right-handed helices of neighboring granum-stroma assemblies are joined together via bifurcations of membranes and left-handed helical surfaces (Bussi et al. 2019). These relatively narrow ‘bridges’ might constitute a barrier for ionic currents in the lumen – e.g. if these ‘bridges’ contain stalks or lipid assemblies similar to those involved in the lateral fusion of PSII membranes (Böde et al. 2024a). A possible scenario of disrupting the lumen-lumen continuity by a non-bilayer lipid phase is depicted in

Figure 5.

Energetically, and to reach the threshold of pmf, autonomy of granum-stroma units is evidently advantageous compared to sharing the energized state of each unit with all other granum-stroma assemblies in a chloroplast. In this context, it is interesting to evoke the photophosphorylation autonomy of purple bacterial chromatophores (Altamura et al. 2021) and the energetic autonomy of individual cristae of mitochondria (Wolf et al. 2019).

5.2. Compromised Membrane Impermeability; Role of Protein Networks in Utilizing PMF

Recently Fehér and coworkers (Fehér et al. 2023), using coarse-grained molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, compared the permeability of two bilayers: one, constructed from a TM lipid mixture and the other from DPPC (dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine). It was found that the permeability of the bilayer composed of TM lipids was almost two orders of magnitude larger than that of the membrane formed by the typical bilayer lipid DPPC. Recent MD simulations using TM lipid mixtures have further revealed that MGDG promotes dynamic fluctuations in membrane thickness and spontaneous formation of inverted hexagonal phases and other, not well-defined non-bilayer structures (Fehér et al. 2024). These processes dependent heavily on the concentration of MGDG as well as on the hydration state and temperature of the lipid assemblies. These findings are in harmony with the generally accepted view that biological membranes that contain non-bilayer lipids are in frustrated state and that “a membrane composed solely of lamellar lipids would be an optimum insulator, only non-compatible with cell function, i.e. life” (Goñi 2014).

It is an intriguing question whether the inferior electrical insulation capability due to the presence of MGDG is simply an unavoidable consequence of the presence of non-bilayer lipids requested for ‘secondary’ functions of TMs (such as the fusion of membranes, and lipocalins), or these lipids play a more fundamental role in the energy conversion. The answer to this question depends on the physical and molecular mechanisms of the energization of TMs.

The nature of the energized state and the mechanism of its utilization for ATP synthesis in energy-converting biological membranes is long-debated. Many authors (Williams 1979, Cherepanov et al. 2003, Dilley 2004, Mulkidjanian et al. 2006, Sjöholm et al. 2017, Morelli et al. 2019, Kell 2021, 2024, Nesterov et al. 2024, Variyam et al. 2024) proposed mechanisms deviating from or modifying the original form of the chemiosmotic theory of (Mitchell 1966). Most of the modified chemiosmotic models suggest that protons, instead of being released to the bulk aqueous phase, are conducted along the surface of membranes towards the ATP synthase. As pointed out by (Goñi 2014), Mitchell’s chemiosmotic concept can be reconciled with these models, if the value of pmf is „calculated surface-to-surface, rather than bulk-to-bulk”.

The ‘proton-conduction’ models are strongly supported by the discovery that water molecules at the membrane-water interface represent an electrostatic barrier toward the bulk water phase (Mulkidjanian et al. 2006). Water-protein (and water-membrane interfaces, in general) are comprised of polarized multilayers of water molecules, aka layers of confined water, which possess distinct structural and dynamical features compared to bulk water (Dér et al. 2007, Ghosh et al. 2007, Nagata and Mukamel 2010, Trapp et al. 2010, Nickels and Katsaras 2015, Frias and Disalvo 2021, Bellissent-Funel 2023). Proton-binding networks, or so-called ‘proton antennas’, which can be formed, e.g., by clusters of H-bond-forming (carboxylic) side chains of membrane proteins or lipid head groups and water molecules. have been proposed to exist in different biological systems such as PSII, channelrhodopsins and GFP complexes (Shinobu et al. 2010, Bondar 2022, Aoyama et al. 2024). Proton antennas are able to gather and transiently store protons.

According to a recently proposed mechanism, the so-called protet mechanism, energy coupling in oxidative and photosynthetic phosphorylation, is based on protein networks. The basic assumption of the ‘protet’ model, or protonic charge transfer model, is that protons are stored in and drained from protein networks (Kell 2021, 2024). When applying the ‘protet’ model for the energization of TMs and the utilization of pmf, we also invoke the role of bound water molecules and assume that protons – produced upon splitting water at the donor side of PSII, and ejected upon the oxidation of plastoquinol molecules by the cyt b6f complex – are not released to the bulk water phase of the lumen; instead, they remain in the hydration layer of proteins. By this means, protons can be accumulated on protein residues on the lumenal side. Their release into the lumen, which is densely packed with a large variety of proteins (Gollan et al. 2021, Farci and Schröder 2023), could easily be dispersed and ‘lost’ for ATP synthesis. It is an interesting question, which deserves further considerations, what could be the spectral fingerprints of these transiently stored protons; and how the proposed protet mechanism(s), the storage of protons (Kell 2024), is harmonized with known ΔpH-dependent regulatory mechanisms (Ruban and Saccon 2022, Iwai et al. 2024).

For the conduction of protons for long distances from PSII to the ATP synthase, we invoke the Grotthus mechanism, or proton jumping mechanism; according to this mechanism, the deposited protons (e.g., generated by PSII) diffuse through the hydrogen bond network of water molecules (Agmon 1995). The feasibility of long-distance proton migration has recently been demonstrated on self-assembled peptide constructs, which allow proton transport over micrometer-size distances (Censor et al. 2024) and references therein).

Using the above premises, we hypothesize that the integrity of the protein network, which allows the efficient generation and utilization of pmf in TMs, is secured by the high abundance of MGDG. To prevent the disruption of this network via ‘diluting’ the protein density of TMs by lipids, MGDG must be present in high amounts relative to the bilayer lipids. It appears that other roles of MGDG as non-bilayer lipid, such as supporting the activity of VDE and mediating membrane fusions, require much lower concentrations. Indeed, in a model system, high de-epoxidation rates were obtained with MGDG concentrations that were significantly lower than in TMs (Latowski et al. 2002); also, fusion of most biological membranes occurs at much lower concentrations of non-bilayer lipids. In contrast, the segregation capability of lipids in excess depends prominently on the concentration of non-bilayer lipids, as reflected by the strong dependence of the formation of HII phase on the concentration of MGDG (Fehér et al. 2024). In general, the proportion of non-bilayer lipids in lipid mixtures largely determines their non-bilayer propensity (Seddon and Templer 1995, Williams 1998); this, in turn, adjusts the protein-to-lipid ratio of the membrane (Garab et al. 2000).

With regard to the role of water in TMs, recent experimental findings have indicated that ordered layers of water molecules play a crucial role in maintaining the ultrastructure of chloroplasts (Zsíros et al. 2020). It was shown that water-structure-breaking (chaotropic) salts, such as sodium perchlorate or sodium thiocyanate, led to a rapid disassembly of TM ultrastructure. Numerous data also indicate that lipid head groups are tightly associated with water (Trapp et al. 2010, Nickels and Katsaras 2015). It is equally important to realize that – in the presence of non-bilayer lipids – the polymorphic lipid phase behavior of membranes is highly sensitive to their hydration state (Seddon and Templer 1995, van Eerden et al. 2015, Fehér et al. 2024). Hence, this factor adds another dimension to the structural dynamics of TMs – strongly suggesting that the high abundance of MGDG has important physiological / regulatory roles. This notion is supported by the fact that the MGDG-deficient Arabidopsis mutant (mgd1) suffers from defects in chloroplast ultrastructure (Jarvis et al. 2000). Key role of glycerolipid remodelling in stress physiology is also well established (Yu et al. 2021).

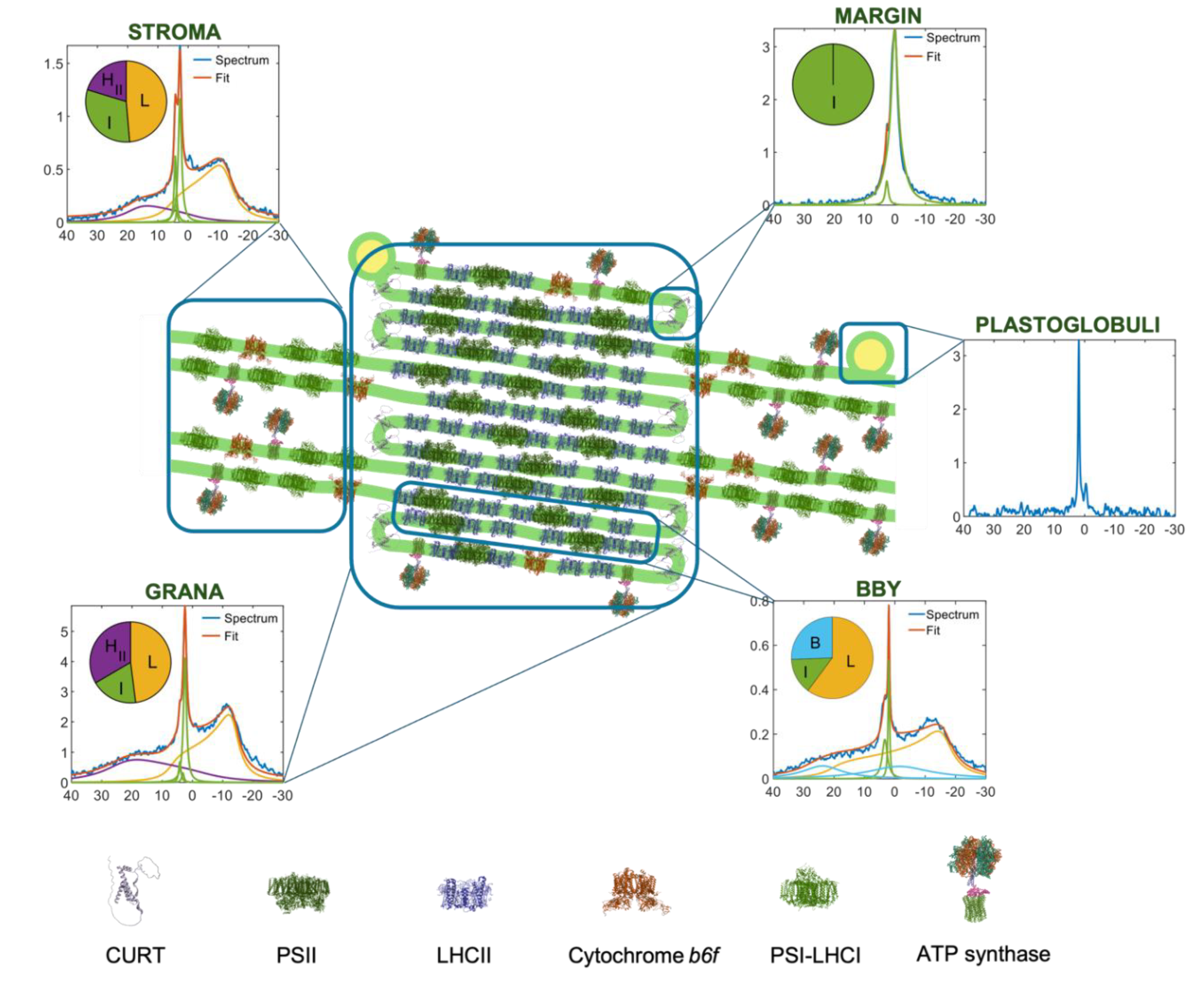

In the light of the above findings, delocalization of Δμ

H+ in the bulk aqueous phases seems unlikely, or at least delayed substantially compared to the proton-conduction pathways along the membrane surfaces (Kell 2021, 2024). Key elements of the proposed mechanism of diffusion of PSII protons from the core of the grana to the ATP synthase in the stroma are displayed in

Figure 6. We emphasize that the structural basis of this mechanism is provided by densely packed arrays of PSII-LHCII supercomplexes, warranted by the high abundance of MGDG. This quasi-continuous network of supercomplexes possess protonable residues at the lumenal side.

6. Concluding Remarks

We reviewed experimentally established facts on the polymorphic phase behavior of plant TMs and stressed the fundamental significance of non-bilayer lipid phases in the self-assembly and structural and functional dynamics of TMs. We hypothesize that non-bilayer lipid phases facilitate the formation of functional subcompartments in plant TMs, allowing an energetic autonomy of each granum stroma TM assembly. Further, it is pointed out that the compromised electrical insulation capability of TMs, due to the presence of MGDG, is not necessarily in conflict with the generation of pmf and its utilization for ATP synthesis – if using a modified chemiosmotic theory. In fact, the high abundance of MGDG might well be a key boundary condition that secures the operation of the energy converting machinery, which is proposed to be based on proton-conduction pathways on the quasi-continuous, hydrated protonable protein residues on the lumenal side of TMs.

The strong dependence of the phase behavior of lipid mixtures on their hydration state and the sensitivity of the lipid polymorphism of TMs to factors, such as the ΔpH, ionic and the osmotic strength of the stroma liquid, as well as the ambient temperature strongly suggest the involvement of non-bilayer lipid phases in regulatory mechanisms governing e.g. TM responses to heat and drought stresses of plants.

Author Contributions

The concepts of the study were conceived by G.G. and V.Š. – and were gradually refined with the participation of all authors: K.B., O.D. and V.K. focused on aspects of the polymorphic lipid phase behavior of thylakoid membranes, and Z.N. and A.D. on the energization of energy-converting membranes, in general. The figures were prepared by K.B. G.G. edited the drafts and the final version of the manuscript with the help of K.B. and O.D. All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR 23-07744S to G.G.), the European Union under the LERCO project (CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000003) via the Operational Programme Just Transition, and the Hungarian National Research Excellence Programme (NKFI-1 150958 to A.D.). We are grateful for the CERIC-ERIC financial assistance for travel and lodging of our 31P-NMR measurement campaigns – and especially for the assistance at the Slovenian NMR Center provided by Uroš Javornik, Dr. Primož Šket and Prof. Janez Plavec. The authors of this preprint are grateful to Dr. Anja Krieger-Liszkay and the two anonymous reviewers of Physiologia Plantarum for their valuable and helpful suggestions. The corresponding author (G.G.) would like to dedicate this paper to the memory of Dr. Geoffrey Hind (1937-2024), commemorating many years of intense and highly inspiring collaborative works conducted mainly in his laboratory at the Brookhaven National Laboratory and enjoying Geoff’s and Bonie’s warm hospitality in Center Moriches, Long Island, NY. The authors wish to thank Dr. Petar H. Lambrev for his continued interest in this topic and stimulating discussions. Legend to Supplementary Movie 1: Spontaneously formed pathways of protons on the lumenal side of PSII-LHCII supercomplexes. For further details, see the legend to Figure 6b. Legend to Supplementary Movie 2: The formation of pmf and its utilization for ATP synthesis in plant TMs – for details of this hypothesis, see Legend to Figure 6.

References

- Agmon N (1995) The Grotthuss mechanism. Chemical Physics Letters 244(5): 456-462.

- Altamura E, Albanese P, Marotta R, Milano F, Fiore M, Trotta M, Stano P, Mavelli F (2021) Chromatophores efficiently promote light-driven ATP synthesis and DNA transcription inside hybrid multicompartment artificial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(7): e2012170118. e, 2012.

- Aoyama M, Katayama K, Kandori H (2024) Unique hydrogen-bonding network in a viral channelrhodopsin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1865(4): 149148.

- Bagatolli LA, Ipsen JH, Simonsen AC, Mouritsen OG (2010) An outlook on organization of lipids in membranes: Searching for a realistic connection with the organization of biological membranes. Progress in Lipid Research 49(4): 378-389.

- Bellissent-Funel M-C (2023) Structure and dynamics of confined water: Selected examples. Journal of Molecular Liquids 391: 123370.

- Blumenthal R, Clague MJ, Durell SR, Epand RM (2003) Membrane fusion. Chemical Reviews (Washington, D C) 103(1): 53-69.

- Böde K, Javornik U, Dlouhý O, Zsíros O, Biswas A, Domonkos I, Šket P, Karlický V, Ughy B, Lambrev PH, Špunda V, Plavec J, Garab G (2024a) Role of isotropic lipid phase in the fusion of photosystem II membranes. Photosynthesis Research 161(1-2): 127-140.

- Böde K, Dlouhý O, Javornik U, Domonkos I, Zsiros O, Plavec J, Špunda V, Garab G (2024b) Lipid polymorphism of the marginal region of plant thylakoid membranes. bioRxiv: 2024.2011.2012.623231.

- Boekema EJ, van Breemen JF, van Roon H, Dekker JP (2000) Arrangement of photosystem II supercomplexes in crystalline macrodomains within the thylakoid membrane of green plant chloroplasts. Journal of molecular biology 301(5): 1123-1133.

- Bondar A-N (2022) Interplay between local protein interactions and water bridging of a proton antenna carboxylate cluster. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1864(12): 184052.

- Boudière L, Michaud M, Petroutsos D, Rébeillé F, Falconet D, Bastien O, Roy S, Finazzi G, Rolland N, Jouhet J, Block MA, Maréchal E (2014) Glycerolipids in photosynthesis: Composition, synthesis and trafficking. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1837(4): 470-480.

- Bruce BD (1998) The role of lipids in plastid protein transport. Plant Mol Biol 38(1-2): 223-246.

- Bussi Y, Shimoni E, Weiner A, Kapon R, Charuvi D, Nevo R, Efrati E, Reich Z (2019) Fundamental helical geometry consolidates the plant photosynthetic membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116(44): 22366-22375.

- Censor S, Martin JV, Silberbush O, Reddy SMM, Zalk R, Friedlander L, Trabada DG, Mendieta J, Le Saux G, Moreno JIM, Zotti LA, Mateo JO, Ashkenasy N (2024) Long-Range Proton Channels Constructed via Hierarchical Peptide Self-Assembly. Advanced Materials 36(50): 2409248.

- Cullis PR, de Kruijff B (1979) Lipid polymorphism and the functional roles of lipids in biological-membranes. Biochimica et biophysica acta 559(4): 399-420.

- Deamer DW, Bramhall J (1986) Permeability of lipid bilayers to water and ionic solutes. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 40(2): 167-188.

- Dekker JP, Boekema EJ (2005) Supramolecular organization of thylakoid membrane proteins in green plants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1706(1): 12-39.

- Dér A, Kelemen L, Fábián L, Taneva S, Fodor E, Páli T, Cupane A, Cacace M, Ramsden J (2007) Interfacial water structure controls protein conformation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 111(19): 5344-5350.

- Dilley RA (2004) On Why Thylakoids Energize ATP Formation Using Either Delocalized or Localized Proton Gradients – A Ca2+ Mediated Role in Thylakoid Stress Responses.

- Dlouhý O, Javornik U, Zsiros O, Šket P, Karlický V, Špunda V, Plavec J, Garab G (2021a) Lipid Polymorphism of the Subchloroplast—Granum and Stroma Thylakoid Membrane—Particles. I. 31P-NMR Spectroscopy. Cells 10(9): 2354.

- Dlouhý O, Kurasová I, Karlický V, Javornik U, Šket P, Petrova NZ, Krumova SB, Plavec J, Ughy B, Špunda V, Garab G (2020) Modulation of non-bilayer lipid phases and the structure and functions of thylakoid membranes: effects on the water-soluble enzyme violaxanthin de-epoxidase.

- Dlouhý O, Karlický V, Arshad R, Zsiros O, Domonkos I, Kurasová I, Wacha AF, Morosinotto T, Bóta A, Kouřil R, Špunda V, Garab G (2021b) Lipid Polymorphism of the Subchloroplast—Granum and Stroma Thylakoid Membrane–Particles. II. Structure and Functions. Cells 10(9): 2363.

- Dlouhý O, Karlický V, Javornik U, Kurasová I, Zsiros O, Šket P, Kanna SD, Böde K, Večeřová K, Urban O, Gasanoff ES, Plavec J, Špunda V, Ughy B, Garab G (2022) Structural Entities Associated with Different Lipid Phases of Plant Thylakoid Membranes - Selective Susceptibilities to Different Lipases and Proteases. Cells 11(17): 2681.

- Farci D, Schröder WP (2023) Thylakoid Lumen; from “proton bag” to photosynthetic functionally important compartment. Frontiers in Plant Physiology 1, Mini Review.

- Fehér B, Voets IK, Nagy G (2023) The impact of physiologically relevant temperatures on physical properties of thylakoid membranes: a molecular dynamics study. Photosynthetica 61(4): 441-450.

- Fehér B, Nagy G, Garab G (2024) Molecular level insight into non-bilayer structure formation in thylakoid membranes: a molecular dynamics study. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation.

- Findinier J, Delevoye C, Cohen Findinier J, Delevoye C, Cohen MM (2019) The dynamin-like protein Fzl promotes thylakoid fusion and resistance to light stress in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLoS Genetics 15(3): e1008047(2019) The dynamin-like protein Fzl promotes thylakoid fusion and resistance to light stress in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.

- Frias MA, Disalvo EA (2021) Breakdown of classical paradigms in relation to membrane structure and functions. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1863(2): 183512.

- Friso G, Giacomelli L, Ytterberg AJ, Peltier JB, Rudella A, Sun Q, Wijk KJ (2004) In-depth analysis of the thylakoid membrane proteome of Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplasts: new proteins, new functions, and a plastid proteome database. Plant Cell 16(2): 478-499.

- Garab G (2014) Hierarchical organization and structural flexibility of thylakoid membranes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1837(4): 481-494.

- Garab G, Ughy B, Goss R (2016) Role of MGDG and Non-bilayer Lipid Phases in the Structure and Dynamics of Chloroplast Thylakoid Membranes. In: Nakamura Y, Li-Beisson Y (eds) Lipids in Plant and Algae Development. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 127-157.

- Garab G, Lohner K, Laggner P, Farkas T (2000) Self-regulation of the lipid content of membranes by non-bilayer lipids: a hypothesis. Trends in Plant Science 5(11): 489-494.

- Garab G, Yaguzhinsky LS, Dlouhý O, Nesterov SV, Špunda V, Gasanoff ES (2022) Structural and functional roles of non-bilayer lipid phases of chloroplast thylakoid membranes and mitochondrial inner membranes. Progress in Lipid Research 86: 101163.

- Garab G, Ughy B, de Waard P, Akhtar P, Javornik U, Kotakis C, Šket P, Karlický V, Materová Z, Špunda V, Plavec J, van Amerongen H, Vigh L, Van As H, Lambrev PH (2017) Lipid polymorphism in chloroplast thylakoid membranes - as revealed by P-31-NMR and timeresolved merocyanine fluorescence spectroscopy. Scientific Reports 7.

- Gasanov SE, Kim AA, Yaguzhinsky LS, Dagda RK (2018) Non-bilayer structures in mitochondrial membranes regulate ATP synthase activity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1860(2): 586-599.

- Ghosh A, Smits M, Bredenbeck J, Bonn M (2007) Membrane-Bound Water is Energetically Decoupled from Nearby Bulk Water: An Ultrafast Surface-Specific Investigation. Journal of the American Chemical Society 129(31): 9608-9609.

- Gollan PJ, Trotta A, Bajwa AA, Mancini I, Aro E-M (2021) Characterization of the Free and Membrane-Associated Fractions of the Thylakoid Lumen Proteome in Arabidopsis thaliana. International journal of molecular sciences 22(15): 8126.

- Goñi FM (2014) The basic structure and dynamics of cell membranes: An update of the Singer–Nicolson model. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1838(6): 1467-1476.

- Goss R, Latowski D (2020) Lipid Dependence of Xanthophyll Cycling in Higher Plants and Algae. Frontiers in plant science 11: 455.

- Gounaris K, Barber J, Harwood JL (1986) The thylakoid membranes of higher plant chloroplasts. The Biochemical journal 237(2): 313-326.

- Gupta TK, Klumpe S, Gries K, Heinz S, Wietrzynski W, Ohnishi N, Niemeyer J, Spaniol B, Schaffer M, Rast A, Ostermeier M, Strauss M, Plitzko JM, Baumeister W, Rudack T, Sakamoto W, Nickelsen J, Schuller JM, Schroda M, Engel BD (2021) Structural basis for VIPP1 oligomerization and maintenance of thylakoid membrane integrity. Cell 184(14): 3643-3659 e3623.

- Harańczyk H, Strzałka K, Dietrich W, Blicharski JS (1995) 31P-NMR observation of the temperature and glycerol induced non-lamellar phase formation in wheat thylakoid membranes. Journal of Biological Physics 21(2): 125-139.

- Harwood JL (1985) Plant Mitochondrial Lipids: Structure, Function and Biosynthesis. In: Douce R, Day DA (eds) Higher Plant Cell Respiration. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 37-71.

- Hryc J, Szczelina R, Markiewicz M, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M (2022) Lipid/water interface of galactolipid bilayers in different lyotropic liquid-crystalline phases. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 9, Original Research.

- Cherepanov DA, Feniouk BA, Junge W, Mulkidjanian AY (2003) Low dielectric permittivity of water at the membrane interface: Effect on the energy coupling mechanism in biological membranes. Biophysical Journal 85(2): 1307-1316.

- Israelachvili JN (2011) Interactions of Biological Membranes and Structures. In: Israelachvili JN (ed) Intermolecular and Surface Forces (Third Edition). Academic Press, San Diego, pp 577-616.

- Iwai M, Patel-Tupper D, Niyogi KK (2024) Structural Diversity in Eukaryotic Photosynthetic Light Harvesting. Annu Rev Plant Biol 75(1): 119-152.

- Jarvis P, Dörmann P, Peto CA, Lutes J, Benning C, Chory J (2000) Galactolipid deficiency and abnormal chloroplast development in the Arabidopsis MGD synthase 1 mutant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97(14): 8175-8179.

- Junglas B, Axt A, Siebenaller C, Sonel H, Hellmann N, Weber SAL, Schneider D (2022) Membrane destabilization and pore formation induced by the Synechocystis IM30 protein. Biophys J 121(18): 3411-3421.

- Kana R, Prásil O, Mullineaux CW (2009) Immobility of phycobilins in the thylakoid lumen of a cryptophyte suggests that protein diffusion in the lumen is very restricted. FEBS letters 583(4): 670-674.

- Karnauchov I, Herrmann RG, Klösgen RB (1997) Transmembrane topology of the Rieske Fe/S protein of the cytochrome b6/f complex from spinach chloroplasts. FEBS Letters 408(2): 206-210.

- Kell DB (2021) A protet-based, protonic charge transfer model of energy coupling in oxidative and photosynthetic phosphorylation. Adv Microb Physiol 78: 1-177.

- Kell DB (2024) A protet-based model that can account for energy coupling in oxidative and photosynthetic phosphorylation.

- Kirchhoff H (2019) Chloroplast ultrastructure in plants. New Phytologist 223(2): 565-574.

- Kirchhoff H, Haase W, Wegner S, Danielsson R, Ackermann R, Albertsson PA (2007) Low-light-induced formation of semicrystalline photosystem II arrays in higher plant chloroplast. Biochemistry 46(39): 11169-11176.

- Kirchhoff H, Hall C, Wood M, Herbstová M, Tsabari O, Nevo R, Charuvi D, Shimoni E, Reich Z (2011) Dynamic control of protein diffusion within the granal thylakoid lumen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108(50): 20248-20253.

- Koochak H, Puthiyaveetil S, Mullendore DL, Li M, Kirchhoff H (2019) The structural and functional domains of plant thylakoid membranes. The Plant Journal 97(3): 412-429.

- Kotakis C, Akhtar P, Zsiros O, Garab G, Lambrev PH (2018) Increased thermal stability of photosystem II and the macro-organization of thylakoid membranes, induced by co-solutes, associated with changes in the lipid-phase behaviour of thylakoid membranes. Photosynthetica 56(1): 254-264.

- Kowalewska Ł, Bykowski M, Mostowska A (2019) Spatial organization of thylakoid network in higher plants. Botany Letters 166(3): 326-343.

- Krumova SB, Dijkema C, de Waard P, Van As H, Garab G, van Amerongen H (2008a) Phase behaviour of phosphatidylglycerol in spinach thylakoid membranes as revealed by P-31-NMR. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1778(4): 997-1003.

- Krumova SB, Koehorst RBM, Bóta A, Páli T, van Hoek A, Garab G, van Amerongen H (2008b) Temperature dependence of the lipid packing in thylakoid membranes studied by time- and spectrally resolved fluorescence of Merocyanine 540. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1778(12): 2823-2833.

- LaBrant E, Barnes AC, Roston RL (2018) Lipid transport required to make lipids of photosynthetic membranes. Photosynthesis research 138(3): 345-360.

- Latowski D, Kruk J, Burda K, Skrzynecka-Jaskier M, Kostecka-Gugała A, Strzałka K (2002) Kinetics of violaxanthin de-epoxidation by violaxanthin de-epoxidase, a xanthophyll cycle enzyme, is regulated by membrane fluidity in model lipid bilayers. European journal of biochemistry 269(18): 4656-4665.

- Liang Z, Yeung W-T, Ma J, Mai KKK, Liu Z, Chong Y-LF, Cai X, Kang B-H (2022) Electron tomography analysis of the prolamellar body and its transformation into grana thylakoids in the cryofixed Arabidopsis cotyledon. bioRxiv: 2022.2004.2004.487035.

- Malnoë A, Schultink A, Shahrasbi S, Rumeau D, Havaux M, Niyogi KK (2018) The Plastid Lipocalin LCNP Is Required for Sustained Photoprotective Energy Dissipation in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 30(1): 196-208.

- Massiot D, Fayon F, Capron M, King I, Le Calvé S, Alonso B, Durand J-O, Bujoli B, Gan Z, Hoatson G (2002) Modelling one- and two-dimensional solid-state NMR spectra. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 40(1): 70-76.

- Mitchell P (1966) Chemiosmotic coupling in oxidative and photosynthetic phosphorylation. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 41(3): 445-502.

- Miyamoto VK, Thompson TE (1967) Some electrical properties of lipid bilayer membranes. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 25(1): 16-25.

- Morelli AM, Ravera S, Calzia D, Panfoli I (2019) An update of the chemiosmotic theory as suggested by possible proton currents inside the coupling membrane.

- Mulkidjanian AY, Heberle J, Cherepanov DA (2006) Protons @ interfaces: implications for biological energy conversion. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1757(8): 913-930.

- Mustárdy L, Garab G (2003) Granum revisited. A three-dimensional model - where things fall into place. Trends in Plant Science 8(3): 117-122.

- Mustárdy L, Buttle K, Steinbach G, Garab G (2008) The Three-Dimensional Network of the Thylakoid Membranes in Plants: Quasihelical Model of the Granum-Stroma Assembly. Plant Cell 20(10): 2552-2557.

- Nagata Y, Mukamel S (2010) Vibrational sum-frequency generation spectroscopy at the water/lipid interface: molecular dynamics simulation study. J Am Chem Soc 132(18): 6434-6442.

- Nesterov SV, Plokhikh KS, Chesnokov YM, Mustafin DA, Goleva TN, Rogov AG, Vasilov RG, Yaguzhinsky LS (2024) Safari with an Electron Gun: Visualization of Protein and Membrane Interactions in Mitochondria in Natural Environment. Biochemistry (Mosc) 89(2): 257-268.

- Nevo R, Charuvi D, Tsabari O, Reich Z (2012) Composition, architecture and dynamics of the photosynthetic apparatus in higher plants. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology 70(1): 157-176.

- Nickels JD, Katsaras J (2015) Water and Lipid Bilayers. Subcell Biochem 71: 45-67.

- Niedermaier S, Schneider T, Bahl M-O, Matsubara S, Huesgen PF (2020) Photoprotective Acclimation of the Arabidopsis thaliana Leaf Proteome to Fluctuating Light. Frontiers in Genetics 11, Original Research.

- Perez-Boerema A, Engel BD, Wietrzynski W (2024) Evolution of Thylakoid Structural Diversity. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 40(Volume 40, 2024): 169-193.

- Ruban AV, Saccon F (2022) Chlorophyll a de-excitation pathways in the LHCII antenna. The Journal of Chemical Physics 156(7).

- Sandoval-Ibáñez O, Sharma A, Bykowski M, Borràs-Gas G, Behrendorff JBYH, Mellor S, Qvortrup K, Verdonk JC, Bock R, Kowalewska Ł, Pribil M (2021) Curvature thylakoid 1 proteins modulate prolamellar body morphology and promote organized thylakoid biogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(42): e2113934118.

- Seddon JM, Templer RH (1995) Polymorphism of Lipid-Water Systems. In: Lipowsky R, Sackmann E (eds) Handbook of Biological Physics. North-Holland, pp 97-160.

- Semenova GA (1999) The relationship between the transformation of thylakoid acyl lipids and the formation of tubular lipid aggregates visible on fracture faces. Journal of Plant Physiology 155(6): 669-677.

- Shinobu A, Palm GJ, Schierbeek AJ, Agmon N (2010) Visualizing Proton Antenna in a High-Resolution Green Fluorescent Protein Structure. Journal of the American Chemical Society 132(32): 11093-11102.

- Simidjiev I, Stoylova S, Amenitsch H, Javorfi T, Mustárdy L, Laggner P, Holzenburg A, Garab G (2000) Self-assembly of large, ordered lamellae from non-bilayer lipids and integral membrane proteins in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97(4): 1473-1476.

- Singer SJ, Nicolson GL (1972) The Fluid Mosaic Model of the Structure of Cell Membranes. Science 175(4023): 720-731.

- Sjöholm J, Bergstrand J, Nilsson T, Šachl R, Ballmoos Cv, Widengren J, Brzezinski P (2017) The lateral distance between a proton pump and ATP synthase determines the ATP-synthesis rate. Scientific Reports 7(1): 2926.

- Solymosi K, Schoefs B (2010) Etioplast and etio-chloroplast formation under natural conditions: the dark side of chlorophyll biosynthesis in angiosperms. Photosynthesis Research 105(2): 143-166.

- Trapp M, Gutberlet T, Juranyi F, Unruh T, Demé B, Tehei M, Peters J (2010) Hydration dependent studies of highly aligned multilayer lipid membranes by neutron scattering. The Journal of Chemical Physics 133(16).

- Ughy B, Karlický V, Dlouhý O, Javornik U, Materová Z, Zsiros O, Šket P, Plavec J, Špunda V, Garab G (2019) Lipid-polymorphism of plant thylakoid membranes. Enhanced non-bilayer lipid phases associated with increased membrane permeability. Physiologia Plantarum 166(1): 278-287.

- an Eerden FJ, de Jong DH, de Vries AH, Wassenaar TA, Marrink SJ (2015) Characterization of thylakoid lipid membranes from cyanobacteria and higher plants by molecular dynamics simulations. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1848(6): 1319-1330.

- Variyam AR, Stolov M, Feng JJ, Amdursky N (2024) Solid-State Molecular Protonics Devices of Solid-Supported Biological Membranes Reveal the Mechanism of Long-Range Lateral Proton Transport. Acs Nano 18(6): 5101-5112.

- Wietrzynski W, Lamm L, Wood WHJ, Loukeri M-J, Malone L, Peng T, Johnson MP, Engel BD (2024) Molecular architecture of thylakoid membranes within intact spinach chloroplasts. bioRxiv: 2024.2011.2024.625035.

- Williams RJ (1979) Some unrealistic assumptions in the theory of chemi-osmosis and their consequences. FEBS letters 102(1): 126-132.

- Williams WP (1998) The Physical Properties of Thylakoid Membrane Lipids and Their Relation to Photosynthesis. In: Siegenthaler PA, Murata N (eds) Lipids in Photosynthesis: Structure, Function and Genetics. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp 103-118.

- Witt HT (1979) Energy-Conversion in the Functional Membrane of Photosynthesis - Analysis by Light-Pulse and Electric Pulse Methods - Central Role of the Electric-Field. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 505(3-4): 355-427.

- Wolf DM, Segawa M, Kondadi AK, Anand R, Bailey ST, Reichert AS, van der Bliek AM, Shackelford DB, Liesa M, Shirihai OS (2019) Individual cristae within the same mitochondrion display different membrane potentials and are functionally independent. EMBO Journal 38(22): e101056.

- Yu L, Zhou C, Fan J, Shanklin J, Xu C (2021) Mechanisms and functions of membrane lipid remodeling in plants. The Plant Journal 107(1): 37-53.

- Zsíros O, Ünnep R, Nagy G, Almásy L, Patai R, Székely NK, Kohlbrecher J, Garab G, Dér A, Kovács L (2020) Role of Protein-Water Interface in the Stacking Interactions of Granum Thylakoid Membranes—As Revealed by the Effects of Hofmeister Salts. Frontiers in plant science 11, Original Research.

Figure 1.

(a) Bilayer and non-bilayer lipid assemblies, indicating also the characteristic motions of lipid molecules (red arrows), and the corresponding 31P-NMR spectra (based on Cullis and de Kruijff 1979). (b) 31P-NMR spectrum of freshly isolated spinach thylakoid membranes (thick dark blue trace) and the fitted spectrum (orange curve) obtained after deconvolution of the spectral components. The area-normalized spectrum represents the average obtained from 52 independent experiments performed at 5 °C; the average Chl content of these samples was 8.3 ± 3.1 mg mL-1. Individual contributions of the lamellar (L, yellow), inverted hexagonal (HII, purple), and isotropic (I1, I2, Ii and I17, green, light blue, red and turquoise, respectively) lipid phases were determined using the software DMfit (Massiot et al. 2002). Inset depicts the integrated areas of the deconvoluted component spectra, associated with the different lipid phases, relative to the overall integrated area; mean values ± SD, n = 52.

Figure 1.

(a) Bilayer and non-bilayer lipid assemblies, indicating also the characteristic motions of lipid molecules (red arrows), and the corresponding 31P-NMR spectra (based on Cullis and de Kruijff 1979). (b) 31P-NMR spectrum of freshly isolated spinach thylakoid membranes (thick dark blue trace) and the fitted spectrum (orange curve) obtained after deconvolution of the spectral components. The area-normalized spectrum represents the average obtained from 52 independent experiments performed at 5 °C; the average Chl content of these samples was 8.3 ± 3.1 mg mL-1. Individual contributions of the lamellar (L, yellow), inverted hexagonal (HII, purple), and isotropic (I1, I2, Ii and I17, green, light blue, red and turquoise, respectively) lipid phases were determined using the software DMfit (Massiot et al. 2002). Inset depicts the integrated areas of the deconvoluted component spectra, associated with the different lipid phases, relative to the overall integrated area; mean values ± SD, n = 52.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the TM ultrastructure and the 31P-NMR spectra of different subchloroplast particles, displaying (in insets) the relative amounts of the contributing lipid phases (L, yellow – lamellar or bilayer phase; I, light green – sum of the sharp isotropic phases similar to those in TMs; HII, purple – inverted hexagonal phase; and B, light blue – sum of the two broad isotropic bands which are present only in BBY and most likely originate from partially detached shell lipids of PSII-LHCII supercomplexes). For the membranous particles (grana, stroma, BBY), the counts are normalized for 10 mg mL-1 chlorophyll content and 6400 scans; for the MR and plastoglobuli preparations, the counts were normalized as described in (Böde et al. 2024a) and (Dlouhý et al. 2022), respectively. It is important to stress that the weak, phospholipase-insensitive 31P-NMR signal of plastoglobuli does not contribute to the lipid polymorphism of TMs (Dlouhý et al. 2022). Note that (i) the granum and stroma TMs exhibit very similar polymorphisms, resembling that of intact TMs, showing that the PSII-LHCII and PSI-LHCI supercomplexes have no preferred lipid phases (Dlouhý et al. 2021a); (ii) the absence of HII phase in BBY is consistent with the finding that this phase originates from association of lipid molecules with stroma-exposed protein(s) or polypetide(s) – as explained in a paragraph below; the lower 31P-NMR amplitudes of BBY, relative to TM, is evidently due to lower lipid-to-protein ratios in BBY samples (Böde et al. 2024a); and (iii) the MR displays an intense isotropic phase (Böde et al. 2024b), probably due to the presence of loosely attached lipid molecules that surround the CURT proteins (PDBs: AF_AFA0A1D6K7J4F1, 9EVX, 6A2W, 2ZT9, 8J7A, 1QO1).

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the TM ultrastructure and the 31P-NMR spectra of different subchloroplast particles, displaying (in insets) the relative amounts of the contributing lipid phases (L, yellow – lamellar or bilayer phase; I, light green – sum of the sharp isotropic phases similar to those in TMs; HII, purple – inverted hexagonal phase; and B, light blue – sum of the two broad isotropic bands which are present only in BBY and most likely originate from partially detached shell lipids of PSII-LHCII supercomplexes). For the membranous particles (grana, stroma, BBY), the counts are normalized for 10 mg mL-1 chlorophyll content and 6400 scans; for the MR and plastoglobuli preparations, the counts were normalized as described in (Böde et al. 2024a) and (Dlouhý et al. 2022), respectively. It is important to stress that the weak, phospholipase-insensitive 31P-NMR signal of plastoglobuli does not contribute to the lipid polymorphism of TMs (Dlouhý et al. 2022). Note that (i) the granum and stroma TMs exhibit very similar polymorphisms, resembling that of intact TMs, showing that the PSII-LHCII and PSI-LHCI supercomplexes have no preferred lipid phases (Dlouhý et al. 2021a); (ii) the absence of HII phase in BBY is consistent with the finding that this phase originates from association of lipid molecules with stroma-exposed protein(s) or polypetide(s) – as explained in a paragraph below; the lower 31P-NMR amplitudes of BBY, relative to TM, is evidently due to lower lipid-to-protein ratios in BBY samples (Böde et al. 2024a); and (iii) the MR displays an intense isotropic phase (Böde et al. 2024b), probably due to the presence of loosely attached lipid molecules that surround the CURT proteins (PDBs: AF_AFA0A1D6K7J4F1, 9EVX, 6A2W, 2ZT9, 8J7A, 1QO1).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the involvement of the non-bilayer, isotropic lipid phase in the lateral fusion of adjacent membrane pairs, BBY particles, enriched in PSII-LHCII supercomplexes (PDB: 5XNL). Using the geometry reported by (Boekema et al. 2000), the average area of a lipid "inclusion" between the supercomplexes is estimated to be ~130 nm², which corresponds to 200–300 lipid molecules in one leaflet of the bilayer. (The area occupied by a lipid molecule in bilayer structures varies between about 0.45 and 0.65 nm² (cf (Hryc et al. 2022). The figure is modified after (Böde et al. 2024a). Similar restrictions for the area available for the bilayer phase would be obtained when using the mean center-to-center distance of 21.2 ± 3.1 nm between PSII supercomplexes (Wietrzynski et al. 2024), and the lateral dimensions of PSII-LHCII (smallest, ~18 nm and largest, ~25 nm).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the involvement of the non-bilayer, isotropic lipid phase in the lateral fusion of adjacent membrane pairs, BBY particles, enriched in PSII-LHCII supercomplexes (PDB: 5XNL). Using the geometry reported by (Boekema et al. 2000), the average area of a lipid "inclusion" between the supercomplexes is estimated to be ~130 nm², which corresponds to 200–300 lipid molecules in one leaflet of the bilayer. (The area occupied by a lipid molecule in bilayer structures varies between about 0.45 and 0.65 nm² (cf (Hryc et al. 2022). The figure is modified after (Böde et al. 2024a). Similar restrictions for the area available for the bilayer phase would be obtained when using the mean center-to-center distance of 21.2 ± 3.1 nm between PSII supercomplexes (Wietrzynski et al. 2024), and the lateral dimensions of PSII-LHCII (smallest, ~18 nm and largest, ~25 nm).

Figure 4.

Model based on the low-pH and elevated temperature induced enhancement of an isotropic phase, which has been shown to bring about the activity of the VDE (Dlouhý et al. 2020); the envisioned association of I phase lipids with VDE dimers (PDB: 3CQN) is consistent with the earlier documented non-bilayer lipid-phase dependent activity of this lumenal photoprotective enzyme (Latowski et al. 2002, Goss and Latowski 2020).

Figure 4.

Model based on the low-pH and elevated temperature induced enhancement of an isotropic phase, which has been shown to bring about the activity of the VDE (Dlouhý et al. 2020); the envisioned association of I phase lipids with VDE dimers (PDB: 3CQN) is consistent with the earlier documented non-bilayer lipid-phase dependent activity of this lumenal photoprotective enzyme (Latowski et al. 2002, Goss and Latowski 2020).

Figure 5.

(a) 3D model of the extensive, fusion-rich vesicular network of thylakoid membrane reconstructed from electron microscopy tomography images; yellow: granum vesicles, light blue: stromal lamellae, blue: inner and outer envelope membranes (Bussi et al. 2019). (b) Proposed mechanism of the lumen-lumen discontinuity involving a non-bilayer lipid structure between adjacent stroma lamellae. (For further explanation and arguments for this hypothesis see the main text.) (PDBs: 8J7A, 2ZT9, 1QO1).

Figure 5.

(a) 3D model of the extensive, fusion-rich vesicular network of thylakoid membrane reconstructed from electron microscopy tomography images; yellow: granum vesicles, light blue: stromal lamellae, blue: inner and outer envelope membranes (Bussi et al. 2019). (b) Proposed mechanism of the lumen-lumen discontinuity involving a non-bilayer lipid structure between adjacent stroma lamellae. (For further explanation and arguments for this hypothesis see the main text.) (PDBs: 8J7A, 2ZT9, 1QO1).

Figure 6.

Schematic model, illustrating the main elements of the proposed modified chemiosmotic mechanism of ATP synthesis in plant TMs. Here we use tenets of the ‚protet’ model (Kell 2024), according to which protons in energy converting membranes are stored in and drained from protein networks for ATP synthesis. Our model heavily relies on the high abundance of MGDG, which – via lending the capability of segregating ‚excess’ lipids from the bilayer – warrants the formation and stability of high-density protein networks in TMs (Garab et al. 2000). Further, we assume that „the membrane surface is separated from the bulk aqueous phase by a barrier of electrostatic nature” (Mulkidjanian et al. 2006), which thus facilitates the conduction of protons along the membrane surface; this prevents the binding of protons to proteins in the lumen, which – in contrast to most textbooks that display an essentially empty lumen with protons inside – contains at least 78 different proteins (Farci and Schröder 2023). Panel (a) illustrates that PSII-LHCII supercomplexes are embedded in the lipid bilayer and that the lumen contains different water-soluble proteins (selected PDBs: 3QO6, 1FC6, 5X56). Panel (b) shows the distribution of positive (red) and negative (blue) charges on the lumenal side of the supercomplex; yellow lines depict some of the different possible proton-conduction pathways (for an animation, see Supplementary Movie 1). Panel (c) depicts the proposed series of events: in the dark, the protons (red dots) are located on the stroma side; upon illumination, they are deposited on the lumenal surface of supercomplexes (here only PSII-LHCII supercomplexes are displayed); finally, the activation of ATP synthase (PDB: 1QO1) drains the protons from these sites and the protons ‚diffuse’ from the grana towards the stroma lamellae by Grotthus mechanism (Agmon 1995). (This series of events is animated in Supplementary Movie 2.).

Figure 6.

Schematic model, illustrating the main elements of the proposed modified chemiosmotic mechanism of ATP synthesis in plant TMs. Here we use tenets of the ‚protet’ model (Kell 2024), according to which protons in energy converting membranes are stored in and drained from protein networks for ATP synthesis. Our model heavily relies on the high abundance of MGDG, which – via lending the capability of segregating ‚excess’ lipids from the bilayer – warrants the formation and stability of high-density protein networks in TMs (Garab et al. 2000). Further, we assume that „the membrane surface is separated from the bulk aqueous phase by a barrier of electrostatic nature” (Mulkidjanian et al. 2006), which thus facilitates the conduction of protons along the membrane surface; this prevents the binding of protons to proteins in the lumen, which – in contrast to most textbooks that display an essentially empty lumen with protons inside – contains at least 78 different proteins (Farci and Schröder 2023). Panel (a) illustrates that PSII-LHCII supercomplexes are embedded in the lipid bilayer and that the lumen contains different water-soluble proteins (selected PDBs: 3QO6, 1FC6, 5X56). Panel (b) shows the distribution of positive (red) and negative (blue) charges on the lumenal side of the supercomplex; yellow lines depict some of the different possible proton-conduction pathways (for an animation, see Supplementary Movie 1). Panel (c) depicts the proposed series of events: in the dark, the protons (red dots) are located on the stroma side; upon illumination, they are deposited on the lumenal surface of supercomplexes (here only PSII-LHCII supercomplexes are displayed); finally, the activation of ATP synthase (PDB: 1QO1) drains the protons from these sites and the protons ‚diffuse’ from the grana towards the stroma lamellae by Grotthus mechanism (Agmon 1995). (This series of events is animated in Supplementary Movie 2.).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).