Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

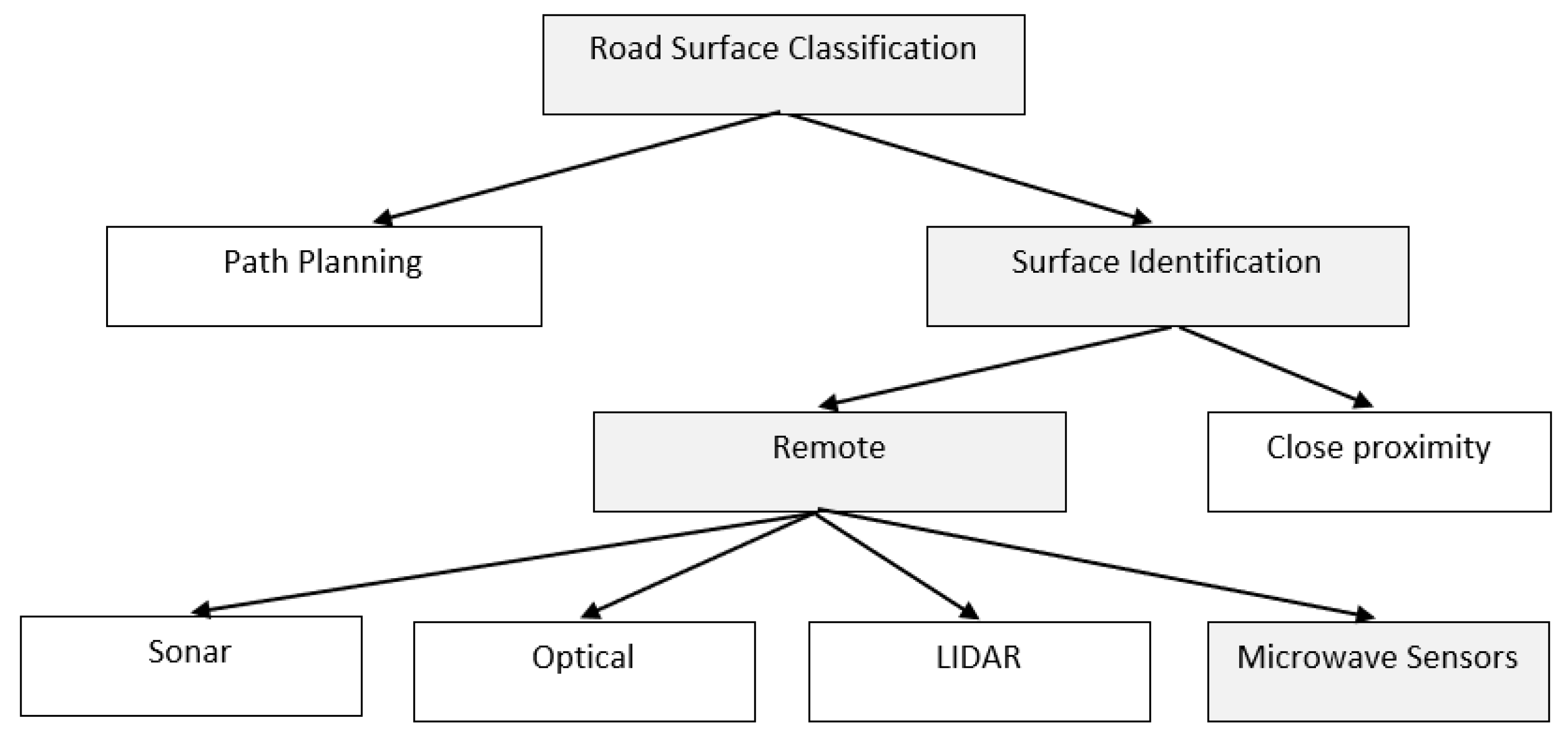

2. Surface Identification Technologies

- The first scenario involves detecting and classifying objects on the Earth's surface by measuring the characteristics of reflected or emitted radiation from regions using satellites, aircraft or drones. Such endeavors aim to achieve various objectives, such as detecting forest wildfires, identifying different types of vegetation and crops, determining soil types and moisture content, and monitoring processes like deforestation and urban growth [7]. The methods and algorithms developed for classifying surfaces in the context of remote sensing are often applicable to ground-based sensing as well, which will be the primary focus of this review.

- The second scenario involves the identification and differentiation of the road area and various road objects, such as cars, curbs, potholes, etc., for path planning in tasks related to autonomous driving. Numerous publications and reviews are dedicated to this specific research area [8-10]. Detecting and recognizing various classes of objects presents significant differences. Cars, being dynamic, are typically detected using Doppler methods with clutter suppression. On the other hand, all other objects, including parked cars and stationary road infrastructure, demand a distinct approach, often relying on imagery methods with region-based classification.

- The third scenario considered in this review relates to the classification of road surface types, such as asphalt, gravel, sand, etc., with the primary goal of enhancing driving safety. In this review, we will focus on remote sensing technologies. Therefore, close proximity methodologies involving the analysis of tire noise, heating due to friction, or various parameters of the vehicle's running system [11-16] will be excluded from the scope of this paper.

3. Basic Principles Underlying Surface Classification

3.1. EM Signal Scattering

3.2. Considerations for Surface Identification in Automotive Radar Applications

3.3. Importance of High Signal Frequencies

4. Feature-based Solutions for Road Surface Classification

4.1. Research on Road Surface Classification Using Stationary Systems

4.2. Automotive-Based Microwave Sensors for Surface Identification

4.2.1. Automotive Microwave Sensors Below 100 GHz

4.2.2. Automotive Radars Operating in Sub-THz Range

5. Road Surface Classification Based on Radar Imaging

6. Sensor Fusion for Road Surface Classification

7. Discussion and Conclusions

- The emerging trend towards the introduction of partially autonomous and autonomous vehicles and a growing awareness of the crucial task of classifying surfaces for autonomous driving.

- The development of the theory of signal reflection from surfaces with varying roughness and dielectric properties, providing the theoretical foundations for surface classification.

- The emergence of compact microwave sensors and an increase in their frequency to the range of sub-THz signals.

- Advancements in statistical methods of classification, particularly the utilization of ANNs for surface classification purposes.

- Increasing the resolution of the radar and the capability of obtaining radar images approaching optical ones.

- Application of deep neural networks for surface classification.

- Sensor fusion.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chan, C.-Y. Advancements, prospects, and impacts of automated driving systems. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology, 2017, 6, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Díaz, M.; Soriguera, F. Autonomous vehicles: theoretical and practical challenges. Transportation Research Procedia 2018, 33, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A. Remote sensing technology for automotive safety. Microwave J. 2007, 50, 24–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ulaby, F.T.; Moore, R. K.; Fung, A. K. Microwave Remote Sensing. Vol. 2, Radar Remote Sensing and Surface Scattering and Emission Theory, Artech House: Boston, 1986.

- Fung, A.K. Microwave Scattering and Emission Models and their Applications, Artech House: Boston, 1994.

- Vlacic, L.; Parentand, M.; Harashima, F. Intelligent Vehicle Technologies, Theory and Applications; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.B.; Wynne, R.H.; Thomas, V.A. Introduction to Remote Sensing, 6th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yeong, D.J.; Velsco-Hernandez, G.; Barry, J.; Walsh, J. Sensor and sensor fusion technology in autonomous vehicles: a review. MDPI Sensors 2021, 21(6), 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Niu, Q. Multi-sensor fusion in automated driving: a survey. IEEE Access 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroescu, A.; Cherniakov, M.; Gashinova, M. Classification of high-resolution automotive radar imagery for autonomous driving based on deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 20th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Ulm, Germany, 1-10., 26-28 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, J.; Lopez, J.M.; Pavon, I.; Recuero, M.; Asenio, C.; Arcas, G.; Bravo, A. On-board wet road identification using tyre/road noise and Support Vector Machines. Appl. Acoust. 2014, 76, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, J.P.; Bento Coelho, J.L. Method for identification of road pavement types using a Bayesian analysis and neural networks. In Proceedings of the 17th International Congress on Sound and Vibration, Cairo, Egypt, 1–8., 18–22 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paulo, J.P.; Bento Coelho, J.L. Statistical classification of road pavements using near field vehicle rolling noise measurements. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 128, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Blanche, D. Mitchell, D. Flynn. Run-time analysis of road surface conditions using non-contact microwave sensing. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Global Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 12-16 December 2020.

- Salazar, A.; Rodriguez, A.; Vargas, N.; Vergara, L. On training road surface classifiers by data augmentation. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchetta, A.; Manetti, S.; Francini, F. Forecast: A neural system for diagnosis and control of highway surfaces. IEEE J. Intell. Syst. Their Appl. 1998, 13, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinmoto, Y.; Takagi, J.; Egawa, K.; Marata, Y.; Takeuchi, M. Road surface recognition sensor using an optical spatial filter. In Proceedings of the 1997 IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 12-12 November 1997, 1000-1004.

- Yamada, M.; Oshima, T.; Ueda, K.; Horiba, I.; Yamamoto, S. A study of the road surface condition detection technique for deployment on a vehicle. JSAE Review, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jokela, M.; Kutila, M.; Le, L. Road condition monitoring system based on a stereo camera. In Proceedings of the IEEE 5th International Conf. Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 27-29 August 2009. 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.-J.; Jang, H.; Jeong, D.-S. Detection algorithm for road surface condition using wavelet packet transform and SVM. In Proceedings of the 19th Korea-Japan Joint Workshop on Frontiers of Computer Vision, Incheon, South Korea, 30 January - 01 February 2013, 323–326.

- Nolte, M.; Kister, N.; Maurer, M. Assessment of deep convolutional neural networks for road surface classification. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC) 4-7 November 2018 Maui, HI, USA.

- Jonsson, P.; Casselgren, J.; Thörnberg, B. Road surface status classification using spectral analysis of NIR camera images. IEEE Sensors Journal 2015, 15(3), 1641–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasshofer, R.H.; Spies, M.; Spies, H. Influences of weather phenomena on automotive laser radar systems. Adv. Radio Sci. 2011, 9, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, M.; Vandapel, N. Terrain classification techniques from LADAR data for autonomous navigation. In Proceedings of the Collaborative Technology Alliances Conference, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Kodagoda, S.; Ranasinghe, R. Road terrain type classification based on laser measurement system data. In Proceedings of the Australian Conference on Robotics and Automation, Wellington, New Zealand, 3-5 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.P.; Zografos, K. Sonar for recognizing the texture of pathways. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2005, 51(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bystrov, A.; Hoare, E.; Tran, T.-Y.; Clarke, N.; Gashinova, M.; Cherniakov, M. Road surface classification using automotive ultrasonic sensor. In Proceedings of the 30th Anniversary Eurosensors Conference, Budapest, Hungary, 19–22., 4–7 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bystrov, A.; Hoare, E.; Tran, T.-Y.; Clarke, N.; Gashinova, M.; Cherniakov, M. Automotive surface identification system. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Safety, ICVES 2017, Vienna, Austria, 27-28 June 2017, 115–120.

- Daniel, L.; Phippen, D.; Hoare, E.; Stove, A.; Cherniakov, M.; Gashinova, M. Low-THz radar, lidar and optical imaging through artificially generated fog. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Radar Systems (Radar 2017), Belfast, UK, 23-26 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzian, F.; Marchetti, E.; Gashinova, M.; Hoare, E.; Constantinou, C.; Gardner, P.; Cherniakov, M. Rain attenuation at millimeter wave and low-THz frequencies. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2020, 68, 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzian, F.; Marchetti, E.; Hoare, E.; Gashinova, M.; Constantinou, C.; Gardner, P.; Cherniakov, M. Experimental study on low-THz automotive radar signal attenuation during snowfall. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2019, 13, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Mandehgar, M.; Grischkowsky, D.R. Broadband THz signals propagate through dense fog. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bystrov, A.; Hoare, E.; Tran, T.-Y.; Clarke, N.; Gashinova, M.; Cherniakov, M. Sensors for automotive remote road surface classification. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Vehicular Electronics and Safety (ICVES), Madrid, Spain, 12-14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, L.L. Electromagnetic reflectivity characteristics of road surfaces. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 1974, 23, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Strutt, J.W. ; Baron Rayleigh, The Theory of Sound, vol. 2, Macmillan, London, 1878.

- Sarabandi, K.; Li, E.S.; Nashashibi, A. Modeling and measurements of scattering from road surfaces at millimeter-wave frequencies. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1977, 45, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.S.; Sarabandi, K. Low grazing angle incidence millimeter-wave scattering models and measurements for various road surfaces. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1999, 47, 851–861. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson, F.E. Radar Design Principles. Signal Processing and the Environment, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, R.; Didascalou, D.; Wiesbeck, W. Impact of road surfaces on millimeter-wave propagation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2000, 49, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Sabery, S.M. , Bystrov A., Navarro-Cía M., Gardner P., Gashinova M. Study of low Terahertz radar signal backscattering for surface identification. MDPI Sensors, 2021; 21. [Google Scholar]

- Hetzner, W. Recognition of road conditions with active and passive millimetre-wave sensors. Frequenz 1984, 38, 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Carpintero, G.; García-Munoz, E.; Hartnagel, H.; Preu, S.; Raisanen, A. (Eds.) Semiconductor TeraHertz technology: Devices and Systems at Room Temperature Operation, John Wiley Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2015.

- Vizard, D.R.; Gashinova, M.; Hoare, E.; Cherniakov, M. Portable low THz imaging radars for automotive applications. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz waves (IRMMW-THz), Hong Kong, China, November 23-28 August 2015.

- Norouzian, F.; Hoare, E.; Marchetti, E.; Cherniakov, M.; Gashinova, M. Next generation, Low-THz automotive radar–the potential for frequencies above 100 GHz. In Proceedings of the 20th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Ulm, Germany, 26-28 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Wireless Telegraphy (Automotive Short Range Radar) (Exemption) Regulations 2013. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2013/1437/pdfs/uksi_20131437_en.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Revision of part 15 of the Commission’s Rules Regarding Ultra-Wideband Transmission Systems, Federal Communications Commission. Available online: https://www.fcc.gov/document/revision-part-15-commissions-rules-regarding-ultra-wideband (accessed on 24 August 2022).

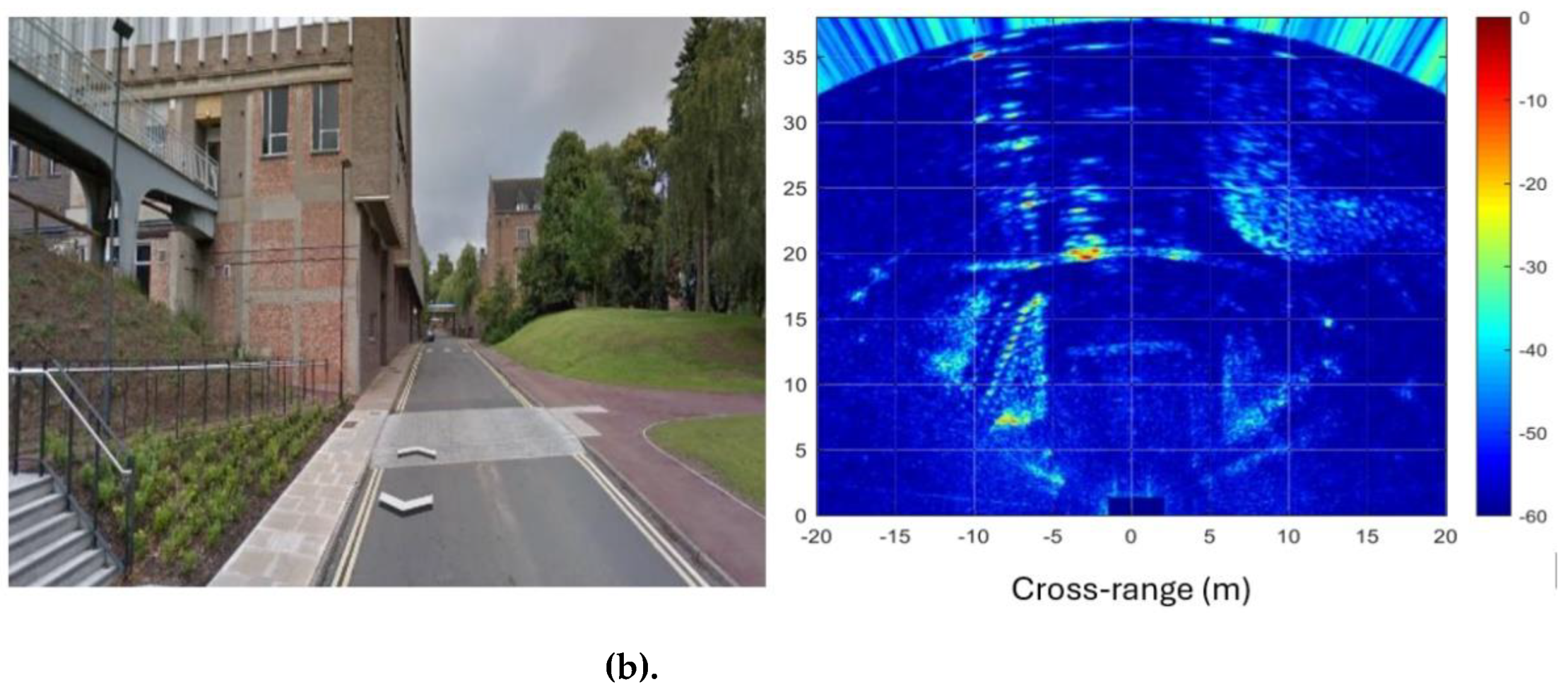

- Jasteh, D.; Hoare, E.; Cherniakov, M.; Gashinova, M. Experimental low-terahertz radar image analysis for automotive terrain sensing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2016, 13, 490–494. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, L.; Phippen, D.; Hoare, E.; Stove, A.; Cherniakov, M.; Gashinova, M. Multi-height radar images of road scenes at 150 GHz. In Proceedings of the 18th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Prague, Czech Republic, 28-30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, L.; Phippen, D.; Hoare, E.; Cherniakov, M.; Gashinova. M. Image segmentation in real aperture Low-THz radar images. In Proceedings of the 20th International Radar Symposium (IRS). Ulm, Germany, 26-28 June 2019.

- Daniel, L.; Xiao, Y.; Hoare, E.; Cherniakov, M.; Gashinova, M. Statistical image segmentation and region classification approaches for automotive radar. In Proceedings of the 2020 17th European Radar Conference (EuRAD), Utrecht, Netherlands, 10-15 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Daniel, L.; Gashinova, M. Image segmentation and region classification in automotive high-resolution radar imagery. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 6698–6711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, J.F.; Grischkowsky, D.R. Comment on the veracity of the ITU-R recommendation for atmospheric attenuation at Terahertz frequencies. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Mandehgar, M.; Grischkowsky, D.R. Broadband THz signals propagate through dense fog. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2015, 27, 383–386.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, J.F.; Ma, J.; Moeller, L. Review of weather impact on outdoor terahertz wireless communication links. Nano Commun. Netw. 2016, 10, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, E.-B.; Jeon, T.-I.; Grischkowsky, D.R. Long-path THz-TDS atmospheric measurements between buildings. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashinova, M.; Hoare, E.; Stove, A. Predicted sensitivity of a 300GHz FMCW radar to pedestrians. In Proceedings of the 46th European Microwave Conference (EuMC), London, UK, 5-7 October 2016, 1497–1500.

- Macelloni, G.; Ruisi, R.; Pampaloni, P.; Paloscia, S. Microwave radiometry for detecting road ice. Proceedings of IEEE 1999 Int. Geosci.Remote Sens. Symp. (IGARSS’99), Hamburg, Germany, 28 June – 2 Jul. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Magerl, G.; Pritzl, W.; Fröhling, W. Remote sensing of road condition. In Proceedings of the Int. Geosci. Remote Sens. Symp., 03-06 June 1991, 2137–2140.

- Finkele, R. Detection of ice layers on road surfaces using a polarimetric millimeter wave sensor at 76 GHz. Electron. Lett. 1997, 33(13), 1153–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snuttjer, B.R.J.; Narayanan, R.M. Millimeter-wave backscatter measurements in support of surface navigation applications. In Proceedings of the Int. Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS'96, Lincoln, NE, USA, 27-31 May 1996; pp. 506–508. [Google Scholar]

- Ulaby, F.T.; Sarabandi, K.; Nashashibi, A. Statistical properties of the Mueller matrix of distributed targets. IEE Proc. F (Radar and Signal Process.) 1992, 139, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkele, R.; Schreck, A.; Wanielik, G. Polarimetric road condition classification and data visualization. In Proceedings of the International ‘Quantitative Remote Sensing for Science and Applications’, In Proceedings of the Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS ‘95), Firenze, Italy, 1786–1788., 10–14 July 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tapkan, R.I.; Yoakim-Stover, S.; Kubichek, F. Active microwave remote sensing of road surface conditions. In Proceedings of the Snow Removal and Ice Control Technology, Roanoke, VA, USA, 11–16 August 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Song, I.Y.; Shin, V. Robust urban road surface monitoring system using Bayesian classification and outlier rejection algorithm. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Control Automation and Systems (ICCAS 2012), Jeju Island, Korea, 17–21 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Song, I.Y.; Yoon, J.H.; Bae, S.H.; Jeon, M.; Shin, V. Classification of road surface status using a 94 GHz dual-channel polarimetric radiometer. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2012, 33(18), 5746–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, V.; Buchberger, C.; Van Driesten, C.; Biebl. E. Retroreflective mmWave measurements to determine road surface characteristics. In Proceedings of the 2019 Kleinheubach Conference Miltenberg, Germany 23-25 September 2019.

- R. Kees; J. Detlefsen. Road surface classification by using a polarimetric coherent radar module at millimetre waves. In Proceedings of the IEEE Nat. Telesystems Conf., San Diego, CA, USA, 23-27 May 1994, 95–98.

- Rudolf, H.; Wanielik, G.; Sieber, A.J. Road conditions recognition using microwaves. In Proceedings of the. IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, ITSC’97, Boston, MA, USA, 12 November 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Giubbolini, L.; Wanielik, G. A microwave coherent polarimeter with velocity gating for road surface monitoring. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Microwaves, Radar and Wireless Communications 2000 (MIKON-2000), Wroclaw, Poland, 22–24 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Viikari, V.; Varpula, T.; Kantanen, M. Automotive radar technology for detecting road conditions. Backscattering properties of dry, wet, and icy asphalt. In Proceedings of the. Eur. Radar Conf., Amsterdam, Netherlands, 30-31 October 2008, 276–279.

- Viikari, V.; Varpula, T.; Kantanen, M. Road-condition recognition using 24-GHz automotive radar. IEEE Trans. On Intelligent Transportation Systems 2009, 10(4), 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viikari, V.; Pursula, P. Novel automotive radar applications. Available online: https://publications.vtt.fi/julkaisut/muut/2011/13-AutomotiveMMID.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Asuzu, P.; Thompson, C. Road condition identification from millimetre-wave radar backscatter measurements. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf18) 23-27 April 2018 Oklahoma City, OK, USA.

- Giallorenzo, M.; Cai, X.; Nashashibi, A.; Sarabandi, K. Radar backscatter measurements of road surfaces at 77 GHz. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation & USNC/URSI National Radio Science Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 08-13 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Renuka Devi, S.M.; Sudeepini, D. Road surface detection using FMCW 77GHz automotive radar using MFCC. In Proceedings of the 6th Int. Conf. on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT 2021), Coimbatore, India, 20-22 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hakli, J.; Saily, J.; Koivisto, P.; Huhtinen, I.; Dufva, T.; Rautiainen, A.; Toivanen, H.; Nummila, K. Road surface condition detection using 24 GHz automotive radar technology. In Proceedings of the 14th International Radar Symposium (IRS 2013), Dresden, Germany, 19–21 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bystrov, A.; Abbas, M.; Hoare, E.; Tran, T.-Y.; Clarke, N.; Gashinova, M.; Cherniakov, M. Analysis of Classification Algorithms Applied to Road Surface Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Radar Conference (RadarCon), Arlington, VA, USA, 10–15 May 2015. 0907–0911. [Google Scholar]

- Bystrov A., Hoare E., Tran T.-Y., Clarke N., Gashinova M., Cherniakov M. (2017). Automotive surface identification system based on modular neural network architecture. In Proceedings of the International Radar Symposium IRS 2017, Prague, Czech Republic, 28-30 June 2017.

- Bystrov, A.; Hoare, E.; Tran, T.-Y.; Clarke, N.; Gashinova, M.; Cherniakov, M. Automotive system for remote surface classificationю MDPI Sensors 2017, 17(4), 745.

- Vassilev, V. Road surface recognition at mm-wavelengths using a polarimetric radar, IEEE Trans. On Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2022, 23(7), 6985-6990.

- Montgomeryy, D.; Holmén, G.; Almersy, P.; Jakobsson, A. Surface classification with millimeter-wave radar using temporal features and machine learning. In Proceedings of the 16th European Radar Conference, Paris, France, 2– 4 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Auriacombe, O.; Vassilev, V.; Uz Zaman, A. Oil, water, and ice detection on road surfaces with a millimeter-wave radiometer. In Proceedings SPIE 11533, Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XXVI, online, 21-25 September 2020.

- Auriacombe, O.; Vassilev, V.; Pinel, N. Dual-polarised radiometer for road surface characterisation. Journal of Infrared, Milli-meter and Terahertz Waves, 2022, 43, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, W.; Fioranelli, F.; Yarovoy, A. Dynamic road surface signatures in automotive scenarios. In Proceedings of the 18th European Radar Conference, London, UK, 05-07 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Qiu, X.; Shi, Z.; Wang, Y. Road Surface Classification Based on Millimeter-Wave Radar Backscatter Measurements. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Ubiquitous Communication, Xi'an, China., 07-09 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S.; Liu, R.; Jiang, B.; Lin, Y.; Xu, H. Material surface classification based on 24GHz FMCW MIMO radar. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE MTT-S International Wireless Symposium (IWS), Beijing, China; 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester, W.; Fioranelli, F.; Yarovoy, A.G. Road Surface Conditions Identification via H α A Decomposition and Its Application to mm-Wave Automotive Radar, IEEE Trans. on Radar Systems, 2023, 1, 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Alageel, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Nashashibi, A.; Shaman, H.; Sarabandi, K. Near-grazing radar backscattering measurements of road surfaces at 222 GHz. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2017, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2322-2324., 23-28 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, T.J.; Nashashibi, A.Y.; Kashanianfard, M.; Sarabandi, K. Polarimetric backscatter measurement of road surfaces at J-band frequencies for standoff road condition assessment. Proceedings of 2021 IEEE USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting (Joint with AP-S Symposium), Singapore, 04-10 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alaqeel, A.; Nashashibi, A.; Sarabandi, K. Sub-millimeter wave automotive radars for road assessment applications. Proceedings of IGARSS 2022 - 2022 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17-22 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bystrov, A.; Hoare, E.; Gashinova, M.; Tran, T.-Y.; Cherniakov, M. Low terahertz signal backscattering from rough surfaces. In Proceedings of the. 16th European Radar Conference, Paris, France, 01-03 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Li, P.; Hu, Y.; Song, F.; Ma, J. Theoretical study on recognition of icy road surface condition by low-Terahertz frequencies. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Gishkori, S.; Wright, D.; Daniel, L.; Gashinova, M.; Mulgrew, B. Forward scanning automotive SAR with moving targets. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Radar Conference (RADAR), Toulon, France, 23-27 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jebramcik, J.; Rolfes, I.; Barowski, J. Aperture synthesis method to investigate on the reflective properties of typical road surfaces. In Proceedings of the 2020 50th European Microwave Conference (EuMC), Utrecht, Netherlands 12-14 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Neural networks and their applications. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1994, 65, 1803–1832. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alpaydin, E. Introduction to Machine Learning, MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010.

- Sabery, S.; Bystrov, A.; Gashinova, M.; Gardner, P. Surface classification based on Low Terahertz radar imaging and deep neural network. In Proceedings of the International Radar Symposium (IRS-2020), Warsaw, Poland, 05-08 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sabery, S.M.; Bystrov, A.; Gardner, P.; Stroescu, A.; Gashinova, M. Road surface classification based on radar imaging using convolutional neural network, IEEE Sensors 2021, 21(17), 18725-18732.

- Cho, J.; Hussen, H.R.; Yang, S.; Kim, J. Radar-based Road surface classification system for personal mobility devices, IEEE Sensors, 2023, 23(14), 16343-16350.

- Cassidy S., L.; Pooni, S.; Cherniakov, M.; Hoare, E. G.; Gashinova M., S. High-resolution automotive imaging using MIMO radar and Doppler beam sharpening, IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, 2022, 59(2), 1495-1505.

- Bekar, M.; Bekar, A.; Baker, C.; Gashinova, M. Improved resolutions in forward looking MIMO-SAR through Burg algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 21st European Radar Conference (EuRAD), Paris, France, 25-27 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Finkele, R. Verfahren zur polarimetrischen Fahrbahnerkennung, German Patent DE 197 18 623.8, 1998. [Google Scholar]

| Video | Lidar | Sonar | 24 GHz Radar | >77GHz Radar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation in adverse weather condition | - | - | + | ++ | ++ |

| Operation at night | -- | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Maximum operation range | ++ | + | - | + | ++ |

| Angular resolution | ++ | + | -- | -- | - |

| Range resolution | + | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| Method | Papers | Advantages | Main limitations |

| Backscattered signal feature analysis, single-polarization radar | [34] [59] [63] [66] [73] [84] | Simple implementation | Limited number of features, challenging to implement automatic classification |

| Backscattered signal feature analysis: polarimetric radar | [36] [37] [39] [40] [58] [60] [61] [62] [67] [68] [69] [70] [71] [72] [74] [76] [80] [87] [88] [91] [92] | Expanded feature set utilizing co-polarized and cross-polarized signals | Challenging to implement automatic classification |

| Emitted signal feature analysis:polarimetric radiometer | [41] [57] [64] [65] [82] [83] | Expanded feature set utilizing co-polarized and cross-polarized signals | Challenging to implement automatic classification |

| Backscattered signal statistical analysis: single-polarization radar | [63] [75] | Simple implementation | Challenge to achieve high accuracy in classification. |

| Backscattered signal statistical analysis: polarimetric radar | [62] [77] [78] [79] | Potential for high accuracy with the extended number of features | Challenges in selecting optimal salient features |

| Backscattered signal analysis using ANN: single-polarization radar | [75] [81] [88] | Simple implementation | Challenge to achieve high accuracy in classification. |

| Backscattered signal analysis using ANN: polarimetric radar | [77] [78] [79] | Potential for high accuracy with the extended number of features | Configuration and training of ANNs can be complex |

| Radar Imaging: Automatic segmentation and classification | [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [93] [94] [95] [96] [97] [98] [99] [100] [101] [102] | High accuracy | Radar implementation is challenging and expensive |

| Sensor data fusion: | |||

| Radar + Weather Station | [64] [65] | Data fusion provides additional features independent of the primary radar data, offering the potential for higher classification accuracy | More complex hardware and software implementation requires synchronization and calibration of sensors data |

| Radar + Sonar | [77] [78] [79] | ||

| Radar + Laser | [103] | ||

| Radar + Radar (different frequencies) | [63] | ||

| Several antennas or MIMO | [62] [75] [76] [85] [86] | ||

| Range doppler radar | [84] |

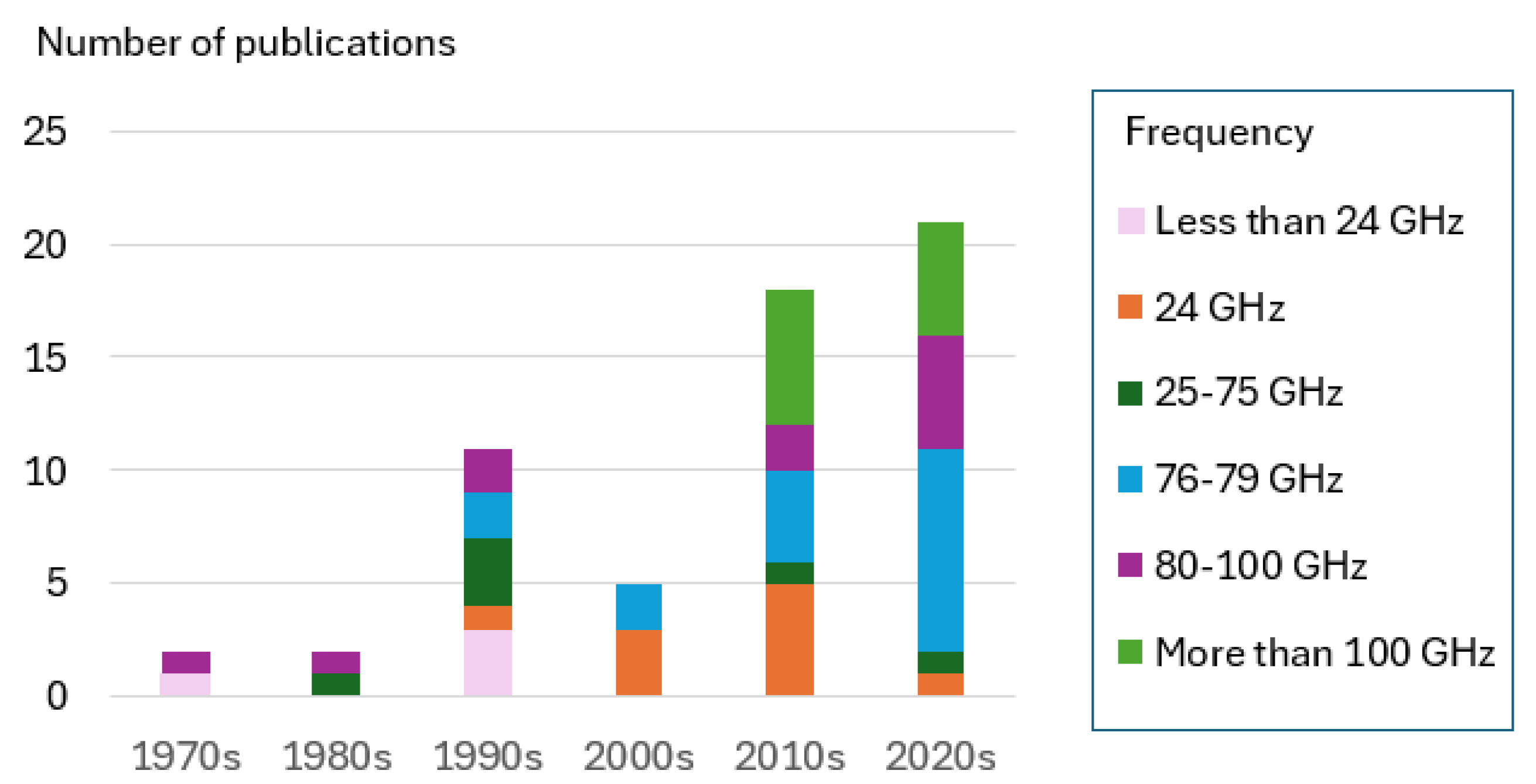

| Frequency | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | 2020s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 24 GHz | [34] | [57], [58], [61] | ||||

| 24 GHz | [68] | [69], [70], [71] | [72], [76], [77], [78], [79] | [86] | ||

| 25 - 75 GHz | [41] | [57], [63], [67] | [81] | [100] | ||

| 76 - 79 GHz | [59], [62] | [39], [70] | [66], [72], [73], [74] | [40], [50], [51], [75], [85], [94], [99], [101], [102] | ||

| 80 - 100 GHz | [36] | [41] | [37], [60] | [64], [65] | [80], [82], [83], [84], [87] | |

| > 100 GHz | [47], [48], [49], [88], [91], [93] | [40], [89], [90], [92], [98] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).