Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- To provide an in-depth review of the CAN bus, including its classical and flexible data-rate (FD) versions.

- To analyze the key components, message arbitration, and error detection mechanisms of CAN networks.

- To compare the performance of CAN against other Intra-Vehicle Networks (IVNs).

- To review the integration of wireless technologies, such as IEEE 802.11b, Bluetooth, and Zigbee, into CAN-based communication.

- To identify gaps in the existing literature, particularly in evaluating the performance of ECUs in autonomous vehicles.

- To highlight future research directions for improving wireless CAN implementations and their scalability.

Controller Area Network (CAN) Types

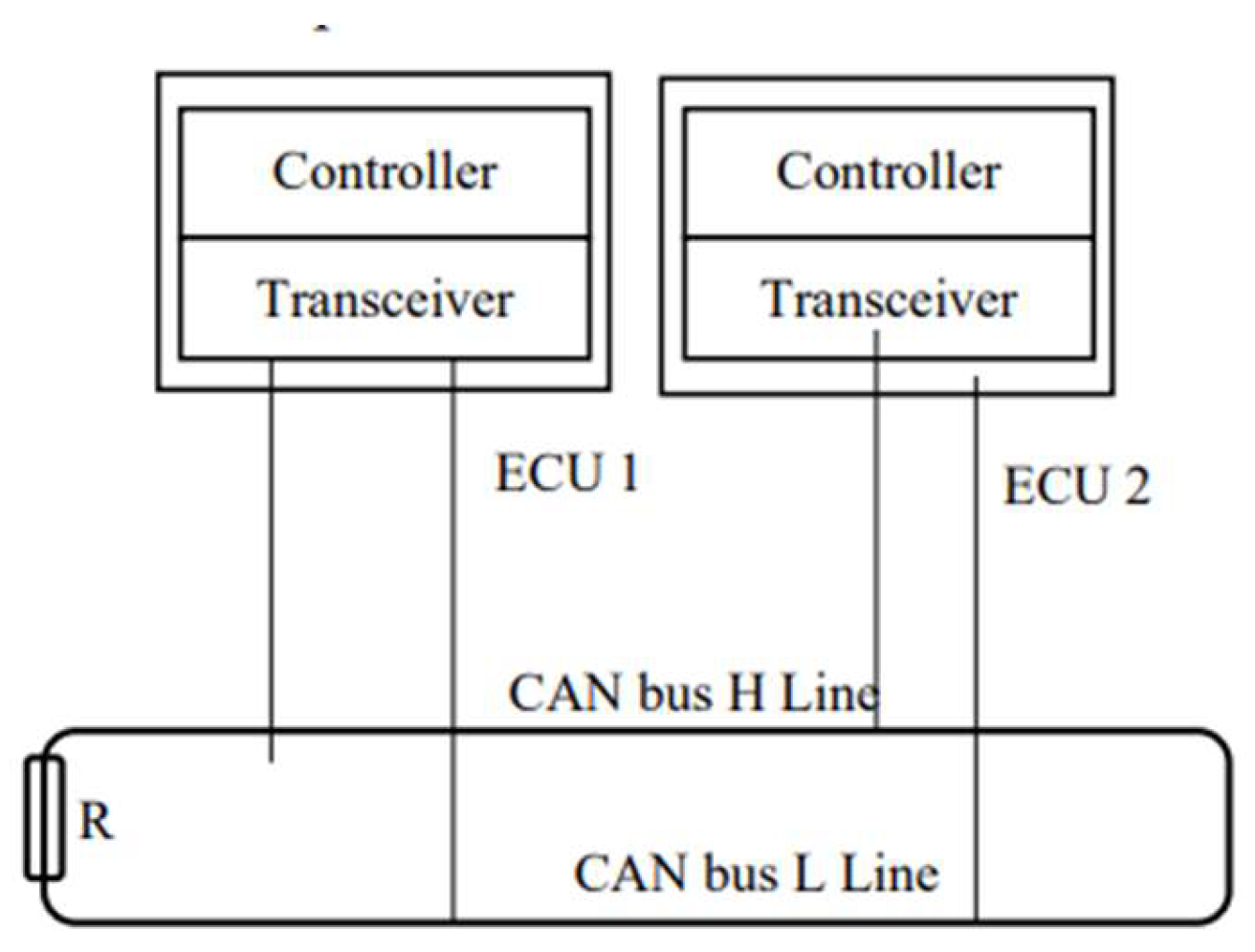

A. Classical Controller Area Network (CAN) Bus

- 1.

- Data Frame

| DLC(decimal) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| CAN (byte) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| CAN_FD(byte) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 32 | 48 | 64 |

- 2.

- Remote Frame

- 3.

- Error Frame

- 4.

- Overload Frame

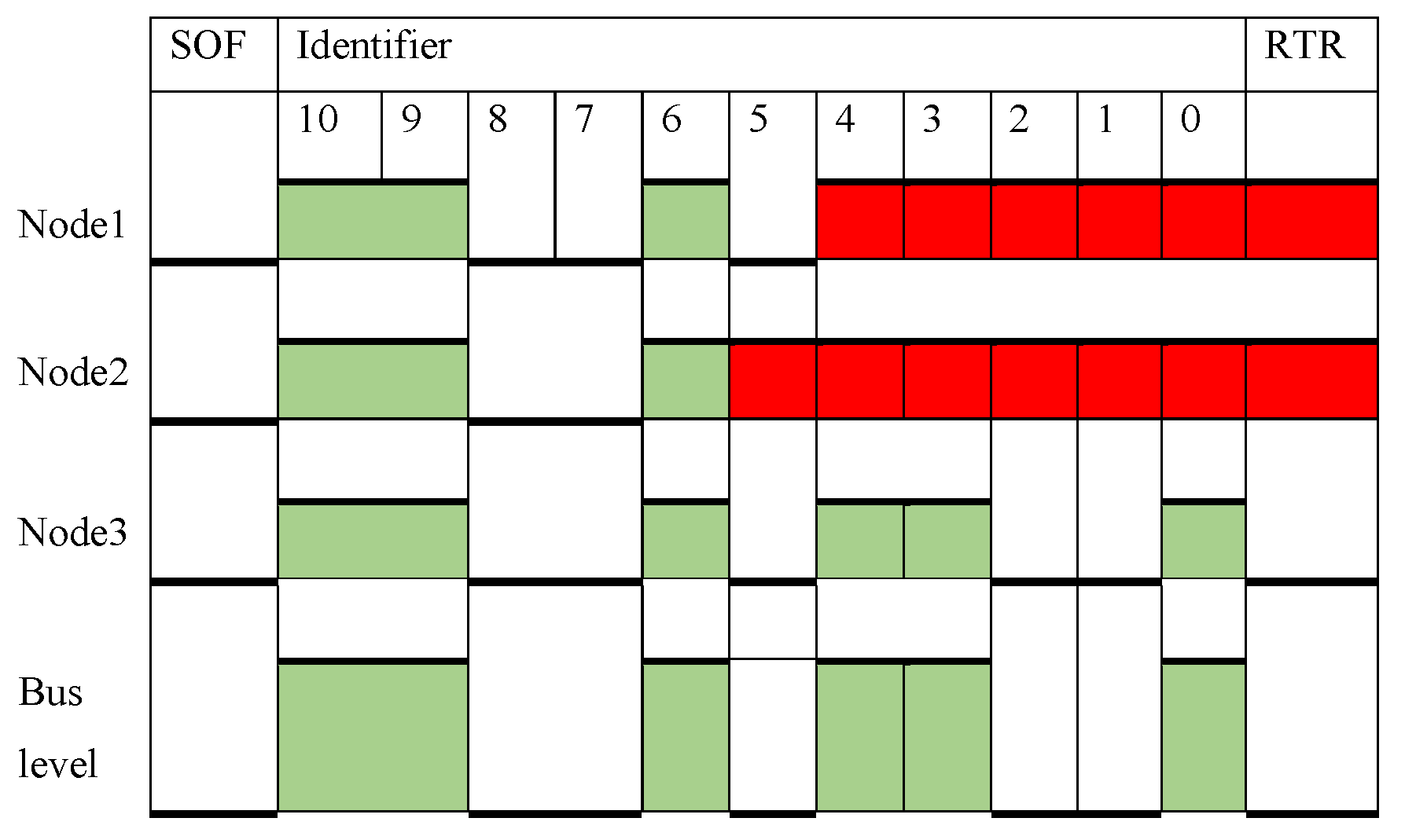

- When a node sends a dominant bit and detects a similar bit on the network (assuming no faults occur), it continues its transmission by sending the subsequent bit.

- If a node sends a recessive bit but detects a dominant bit from another node, it acknowledges a more important message is being transmitted and stops its own transmission.

| Bus name | Data rate | Bus features | Access control |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAN | 1 Mbps | Multi-master serial bus protocol | CSMA/CA |

| CAN-FD | 8 Mbps | Similar to classical CAN with longer data payload | CSMA/CA |

| LIN | 20 Kbps | Broadcast serial bus, master-slave communication and cheaper than CAN | Polling |

| FlexRay | 10 Mbps | Multi-master serial bus, 1-master; up to 16 slaves, expensive protocol and 2 channels | TDMA |

| MOST | 150 Mbps | Ring topology, supports 64 devices and very high cost | CSMA/CA TDMA |

| Industrial Ethernet | 100 Mbps | Cheaper than MOST, more expensive than CAN and lightweight wiring and CSMA/CD | TDMA TDD |

Literature Review

MATHEMATICAL MODEL FOR AV COMMUNICATION BUSES

| Ref | Application | Wireless Technology | Research Tool | Contribution and Strength | Shortcoming |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | Vehicle | Bluetooth | CANBLUE module and CANalyzer | Developed a gateway to convert CAN messages to Bluetooth format using the CANBLUE module. | CAN to Bluetooth gateways are unsuitable for vehicle high-speed wireless networks, no dealing with anti-jamming |

| [17] | Vehicle | Bluetooth | Texas instrument development kit CC2540/CC2541 | Utilized BLE for cost-effective and energy-efficient communication between sensor nodes and the ECU. | Limited data rate not exceed 1 Mbps, no dealing with anti-jamming. |

| [18] | Trucks and Trailers | Bluetooth | DAVE v4 NINA-B1 | Implemented a wireless CAN bridge integrated with the AddVolt network for vehicular refrigeration systems. | Throughput metric not mentioned. In addition, limited data rate |

| [19] | Real-time control applications | ZigBee | XCTU software | Enabled CAN message exchange wirelessly by developing WCAN on FlexDevel board. | Zigbee technology limits data rate, simulate five nodes. ,no dealing with anti-jamming |

| [20] | Vehicle | ZigBee | Lyapunov Optimization Theorem | Designed the Hybrid-Backpressure Collection Protocol to enhance intra-car sensor data collection. | limited data rate |

| [21] | Heavy Duty Vehicles | ZigBee | XBee module | Created a WCAN protocol to link NOx sensors with the vehicle’s engine control unit. | Zigbee technology limits data rate, so WCAN is only between two nodes. ,no dealing with anti-jamming |

| [22] | Industrial control applications | IEEE 802.11 WLAN | OPNET Modeler | Extended CAN segments by utilizing IEEE 802.11 WLAN via WIU | Limited data rate, ,no dealing with anti-jamming |

| [27] | General | 802.11b Token Ring | QualNet simulator. | Implemented a Wireless CAN (WCAN) based on the wireless token ring protocol for multiple nodes. | scalability and complexity constraints, ,no dealing with anti-jamming. |

| [28] | Industrial | On-off Keying | On-Off Keying modulation | Developed a simple wireless transceiver that was compatible with CAN controllers. | Data rate is limited to 125 k bps, ,no dealing with anti-jamming |

| [29] | Vehicle | bridge | STM32F103RC Cortex-M3 microcontroller | Designed and validated the CAN-to-RF platform connected to real cluster units to generate speed and RPM data. | The number of relays and data rate supported by the designed ViCAN depends on wireless excess latency,no dealing with anti-jamming |

| [30] | Vehicle | gateway | Hardware with CANoe | demonstrated a functional prototype of the body controller and gateway of a vehicle interacting with a digital tachometer and cluster. | Limited data rate, no dealing with anti-jamming |

Conclusions

References

- Bozdal, M., Samie, M., and Jennions, I. "A Survey on Can Bus Protocol: Attacks, challenges, and potential solutions." 2018 International Conference on Computing, Electronics and Communications Engineering (iCCECE). IEEE, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, B., and Duwe, R. "Designing Autonomous Vehicles for a Future Of Unknowns." ATZelectronics worldwide vol.16 no.3 (2021): pp. 44-47.

- Sharma, R., “Big Data for Autonomous Vehicles,” in Studies in Computational Intelligence, vol. 945, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2021, pp. 21–47. [CrossRef]

- Boland, H. M., Burgett, M. I., Etienne, A. J., and Stwalley III, R. M. "An Overview of CAN-BUS Development, Utilization, and Future Potential in Serial Network Messaging for Off-Road Mobile Equipment." Technology in Agriculture (2021). [CrossRef]

- Bozdal, M., Samie, M., Aslam, S., and Jennions, I. “Evaluation of CAN Bus Security Challenges,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 20, no. 8, p.2364, MDPI AG, Apr. 02, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Di Natale, M., Zeng, H., Giusto, P., and Ghosal, A. “Understanding and Using the Controller Area Network Communication Protocol: Theory and Practice”. Springer Science and Business Media, 2012.

- Chowdhury, M., and Dey, K. “Intelligent transportation systems-a frontier for breaking boundaries of traditional academic engineering disciplines [Education],” IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 4–8, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hartwich, F. "CAN with Flexible Data-Rate." In Proc. iCC, pp. 1-9. Citeseer, 2012.

- Cataldo, C. "Ethernet Network in the Automotive field: Standards, possible approaches to Protocol Validation and Simulations." Hamburg University of Applied Sciences ,PhD diss., Politecnico di Torino, 2021.

- De Andrade, R., Hodel, K. N., Justo, J. F., Laganá, A. M., Santos, M. M., and Gu, Z. “Analytical and Experimental Performance Evaluations of CAN-FD Bus,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 21287–21295, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, A., Malik, H., Avatefipour, O., Rongali, P. R., and Zehra, S. “Comparative Study of CAN-Bus and FlexRay Protocols for In-Vehicle Communication,” in SAE Technical Papers, SAE International, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, C., Asghar, M. R., and Crispo, B. “Security and privacy in vehicular communications: Challenges and opportunities,” Vehicular Communications, vol. 10. Elsevier Inc., pp. 13–28, Oct. 01, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Cheon, B., and Jeon, J. W. "The CAN FD Network Performance Analysis using the CANoe." In IEEE ISR 2013, pp. 1-5. IEEE, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. H., Cheon, B. M., and Jeon, J. W. "CAN FD performance analysis for ECU re-programming using the CANoe." In The 18th IEEE International Symposium on Consumer Electronics (ISCE 2014), pp. 1-4. IEEE, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Tenruh, M., Oikonomidis, P., Charchalakis, P., and Stipidis, E. "Modelling, Simulation, and Performance Analysis of a CAN FD system with SAE Benchmark Based Message Set." Proc. 15th Int. CAN Conf. 2015. pp. 12-19.

- Vemparala, M. R., Yerabati, S., and Mary, G. I. "Performance Analysis of Controller Area Network Based Safety System in an Electric Vehicle." 2016 IEEE International Conference on Recent Trends in Electronics, Information and Communication Technology (RTEICT). IEEE, 2016. (pp. 461-465. [CrossRef]

- Zago, G. M., and de Freitas, E. P. “A Quantitative Performance Study on CAN and CAN FD Vehicular Networks,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 4413–4422, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Yoo, W., Ha, S., and Chung, J. M. “In-Vehicle Network Average Response Time Analysis for CAN-FD and Automotive Ethernet,” IEEE Trans Veh Technol, vol. 72, no. 6, pp. 6916–6932, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rishvanth, D. V., and Ganesan, K. “Design of an In-Vehicle Network (Using LIN, CAN and FlexRay), Gateway and its Diagnostics Using Vector CANoe,” American Journal of Signal Processing, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 40–45, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Yong, S., Ma, Y., Zhao, Y., and Qi, L."Analysis of the Influence of CAN Bus Structure on Communication Performance." In IoT as a Service: 5th EAI International Conference, IoTaaS 2019, Xi’an, China, November 16-17, 2019, Proceedings 5, pp. 405-416. Springer International Publishing, 2020.

- Hegde, R., Kumar, S., and Gurumurthy, K. “The Impact of Network Topologies on the Performance of the In-Vehicle Network” International Journal of Computer Theory and Engineering, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 405–409, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ishak, M. K., Ali, O., Sirajuduin, E. A., and Qi, L. S. “Vehicle Sensors Programming Based On Controller Area Network (CAN) Bus Using Canoe,” In 2019 16th International Conference on Electrical Engineering / Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI-CON), pp. 1-4. IEEE, 2019.

- Kim, J., Jung, W. Y., Kwon, S., and Kim, Y. “Performance test of autonomous emergency braking system based on commercial radar,” in Proceedings - 2016 5th IIAI International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics, IIAI-AAI 2016, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Aug. 2016, pp. 1211–1212. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A. D. G., Dhadyalla, G., and Kumari, N. "Experimental validation of CAN to Bluetooth gateway for in-vehicle wireless networks." 2013 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Communication, Control, Signal Processing and Computing Applications (C2SPCA). pp. 1-5. IEEE, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, N., and Khan, A. N. “Bluetooth Low Energy based Communication Framework for Intra Vehicle Wireless Sensor Networks,” in Proceedings - 2017 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology, FIT 2017, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Jul. 2017, pp. 29–34. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P. M. M. “Wireless CAN bus bridge,” Master thesis, University of Porto , Jule, 2019.

- Mary, G. I., and Alex, Z. C. “Implementation and response time analysis of messages in Wireless Controller area Network,” Indian J Sci Technol, vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 536–541, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Si, W., Starobinski, D., and Laifenfeld, M. “A Robust Load Balancing and Routing Protocol for Intra-Car Hybrid Wired/Wireless Networks,” IEEE Trans Mob Comput, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 250–263, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Siemuri, A., Glocker, T., Mekkanen, M., Kauhaniemi, K., Mantere, T., and Elmusrati, M. “Design and implementation of a Wireless CAN Module For Marine Engines Using Zigbee Protocol,” IET Communications, vol. 17, no. 13, pp. 1541–1552, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bayilmis, C., Erturk, I., and Ceken, C. “Extending CAN segments with IEEE 802.11 WLAN”. In The 3rd ACS/IEEE International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications, January ,2005. (p. 79). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Patil R. D., and Shinde, V. D. “ Design and Implementation of WIU for CAN/WLAN/CAN Bridge” International Journal Of Innovative Research In Technology,IJIRT , 2015, Vol. 1 Issue 12.

- Purohit, M., Vyas, P., and Bora, A. "Evaluation of MAC Protocols Using Local Bridge in High Frequency Bands Based on Discrete Event Simulator Tool Using Analytical Approach." In 2017 International Conference on Energy, Communication, Data Analytics and Soft Computing (ICECDS), pp. 2103-2107. IEEE, 2017.

- Ozcelik, I. “Interconnection of CAN segments through IEEE 802.16 wireless MAN,” Journal of Network and Computer Applications, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 879–890, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Mary, G. I., Alex, Z. C., and Jenkins, L. “Real Time Analysis of Wireless Controller Area Network” ICTACT Journal on Communication Technology, vol. 05, no. 03, pp. 951–958, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Mary, G. I., and Alex, Z. C. "Modelling, Analysis and Validation of Wireless Controller Area Network." International Journal of Engineering Systems Modelling and Simulation 8, no. 1 (2016): pp. 8-19. [CrossRef]

- Quitin, F. and Osee, M. “A Wireless Transceiver for Control Area Networks: Proof-of-Concept Implementation,” in IEEE International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems - Proceedings, WFCS, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., pp. 1-4. IEEE, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Lee, C., Park, J. H., Choi, B. C., and Ko, J. G. "Poster: Exploiting Wireless CAN Bus Bridges for Intra-Vehicle Communications." In 2014 IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference (VNC), pp. 111-112. IEEE, 2014.

- Lee, C., Jeong, H., Ryu, J., Choi, B. C., and Ko, J. “Demo abstract: Bringing Down Wires in Vehicles - Interconnecting ECUs Using Wireless Connectivity,” in SenSys 2015 - Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems, Association for Computing Machinery, Inc, Nov. 2015, pp. 465–466. [CrossRef]

- Q. I. Ali, "Design, implementation & optimization of an energy harvesting system for VANETs’ road side units (RSU)," IET Intelligent Transport Systems, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 298-307, 2014.

- Q. I. Ali, "An efficient simulation methodology of networked industrial devices," in Proc. 5th Int. Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals and Devices, 2008, pp. 1-6.

- Q. I. Ali, "Security issues of solar energy harvesting road side unit (RSU)," Iraqi Journal for Electrical & Electronic Engineering, vol. 11, no. 1, 2015.

- Q. I. Ali, "Securing solar energy-harvesting road-side unit using an embedded cooperative-hybrid intrusion detection system," IET Information Security, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 386-402, 2016.

- Q. Ibrahim, "Design & Implementation of High-Speed Network Devices Using SRL16 Reconfigurable Content Addressable Memory (RCAM)," Int. Arab. J. e Technol., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 72-81, 2011.

- M. H. Alhabib and Q. I. Ali, "Internet of autonomous vehicles communication infrastructure: a short review," Diagnostyka, vol. 24, 2023.

- Q. I. Ali, "Realization of a robust fog-based green VANET infrastructure," IEEE Systems Journal, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 2465-2476, 2022.

- Q. I. Ali and J. K. Jalal, "Practical design of solar-powered IEEE 802.11 backhaul wireless repeater," in Proc. 6th Int. Conf. on Multimedia, Computer Graphics and Broadcasting, 2014.

| Ref | Application | Research Tool |

Contribution and Strength | Shortcoming |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [13] | General Application | CANoe | The study examined CAN-FD-8-byte and CAN networks, where four ECUs exchanged over 40 messages in a simulated environment. Results indicated that CAN-FD outperformed CAN in terms of network message busload and worst-case response time (WCRT). |

It dealt with limited number of ECUs, few messages. It did not simulate external ECUs |

| [14] | Automative | CANoe | To compare transmission efficiency, the researchers measured the bus transmission times of CAN and CAN FD within a network consisting of two ECUs—one for sending and one for receiving data. A correlation was identified between message count and data bytes, with CAN FD demonstrating superior performance, particularly when flashing large amounts of data to the ECU. |

It dealt with limited number of ECUs. It did not simulate external ECUs |

| [15] | Industrial Applications | MATLAB | The performance of a CAN FD network transmitting a time- and event-based SAE benchmark message set was assessed. Simulation results showed that the CAN FD protocol enhanced real-time control system message delay and improved bus utilization. | It did not simulate external ECUs |

| [16] | Electrical vehicle | CANoe Hardware | For an electric vehicle setup, FSAE standards were used to assess busload and response time across four ECUs. | It dealt with limited number of ECUs. It did not simulate external ECUs. In addition, it did not handle CAN FD |

| [17] | Agriculture Machine | CAN oe | A separate study simulated and analyzed an agricultural machine vehicle network using J1939 and ISO 11783 standards to compare CAN and CAN FD performance with both 8-byte and 64-byte messages. The simulated network included three ECUs and a virtual terminal, with results indicating that CAN FD exhibited lower busload, WCRT, and jitter than CAN. | It dealt with limited number of ECUs. It did not simulate external ECUs |

| [18] | Vehicle | OMNeT++ | Response time estimation was conducted using queuing analysis-based models for CAN, CAN-FD, and Automotive Ethernet. The analytical model featured an 81-message CAN bus connecting six ECUs within both CAN and CAN FD networks. | It dealt with limited number of ECUs. It did not simulate external ECUs |

| [19] | Vehicle | CANoe Hardware | In another study, researchers developed three communication protocols—LIN, classical CAN, and FlexRay—along with a gateway protocol to facilitate message transfers between them. |

It dealt with limited number of ECUs. It did not simulate external ECUs. In addition, it did not handle CAN FD |

| [20] | Vehicle | CANoe | The impact of CAN bus structure on transmission performance was investigated. A multi-level bus CAN network incorporating a gateway was found to reduce both busload and message delay in simulations. |

It did not simulate external ECUs. In addition, it did not handle CAN FD |

| [21] | Vehicle | CANoe | the study compared ring and star network topologies by evaluating busload across four ECUs. Findings revealed that the star topology outperformed the ring topology. |

It dealt with limited number of ECUs. It did not simulate internal ECUs . In addition, it did not handle CAN FD |

| [11] | Vehicle | HCS12 microcontrollers | FlexRay and CAN-Bus latencies were compared, showing that while CAN-Bus is better suited for hard real-time systems, FlexRay offers advantages for low-priority deterministic data transmission. | It dealt with limited number of ECUs. It did not simulate internal ECUs . In addition, it did not handle CAN FD |

| [22] | Vehicle | CANoe | The classical CAN network was analyzed, and when compared to the classical CAN+LIN setup, it was found to have a 2.7% higher average transmission speed. | It dealt with limited number of ECUs. It did not simulate internal ECUs. In addition, it did not handle CAN FD |

| [23] | AV | Commercial radar | The emergency braking system was simulated and tested by integrating a radar sensor with the CAN bus. This setup enabled control over an autonomous vehicle’s speed and movement tracking. The study measured braking starting position errors and braking distances to assess system performance. | It dealt with limited number of ECUs. It did not simulate internal ECUs . In addition, it did not handle CAN FD |

| Bus Type | Data Rate (Mbps) | Bus Utilization (%) | WCRT (ms) | Latency (ms) | PDR (%) | Throughput (kbps) |

| CAN 2.0 | 1 | 75 | 12 | 10 | 95 | 800 |

| CAN FD | 8 | 60 | 6 | 2 | 98 | 5000 |

| IEEE 802.11b | 11 | 40 | 2 | 1.5 | 90 | 7500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).