Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Group-Based Trajectory Models (GBTM) of Medication Adherence

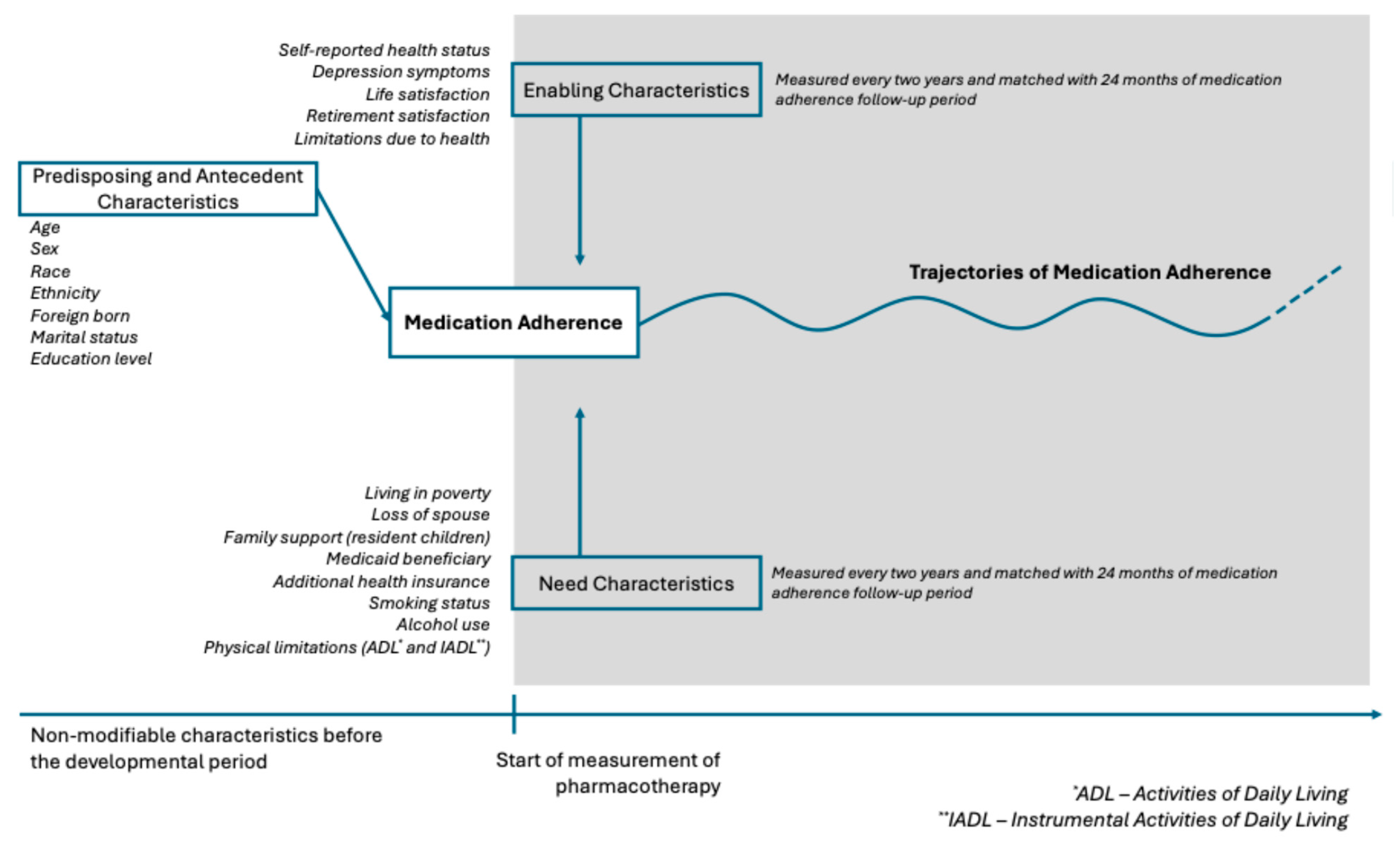

Predictors of Medication Adherence Trajectories

Time-Stable Predictors

Time-Varying Predictors

3. Results

Time-Varying Predictors of Medication Adherence Trajectories

- 1. Enabling characteristics

- Self-reported health status

- Depression Symptoms

- Life satisfaction

- Retirement satisfaction

- Limitations in work due to health

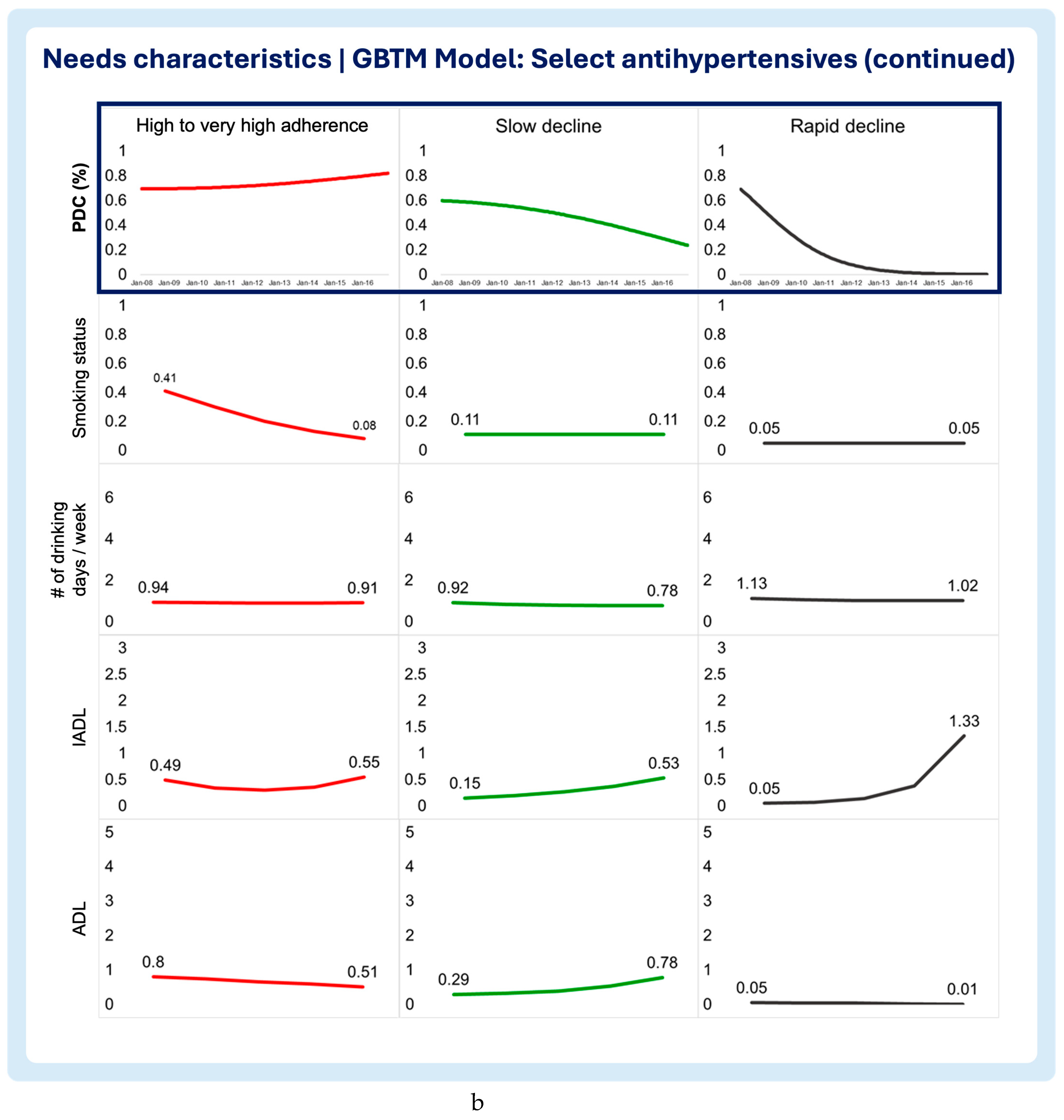

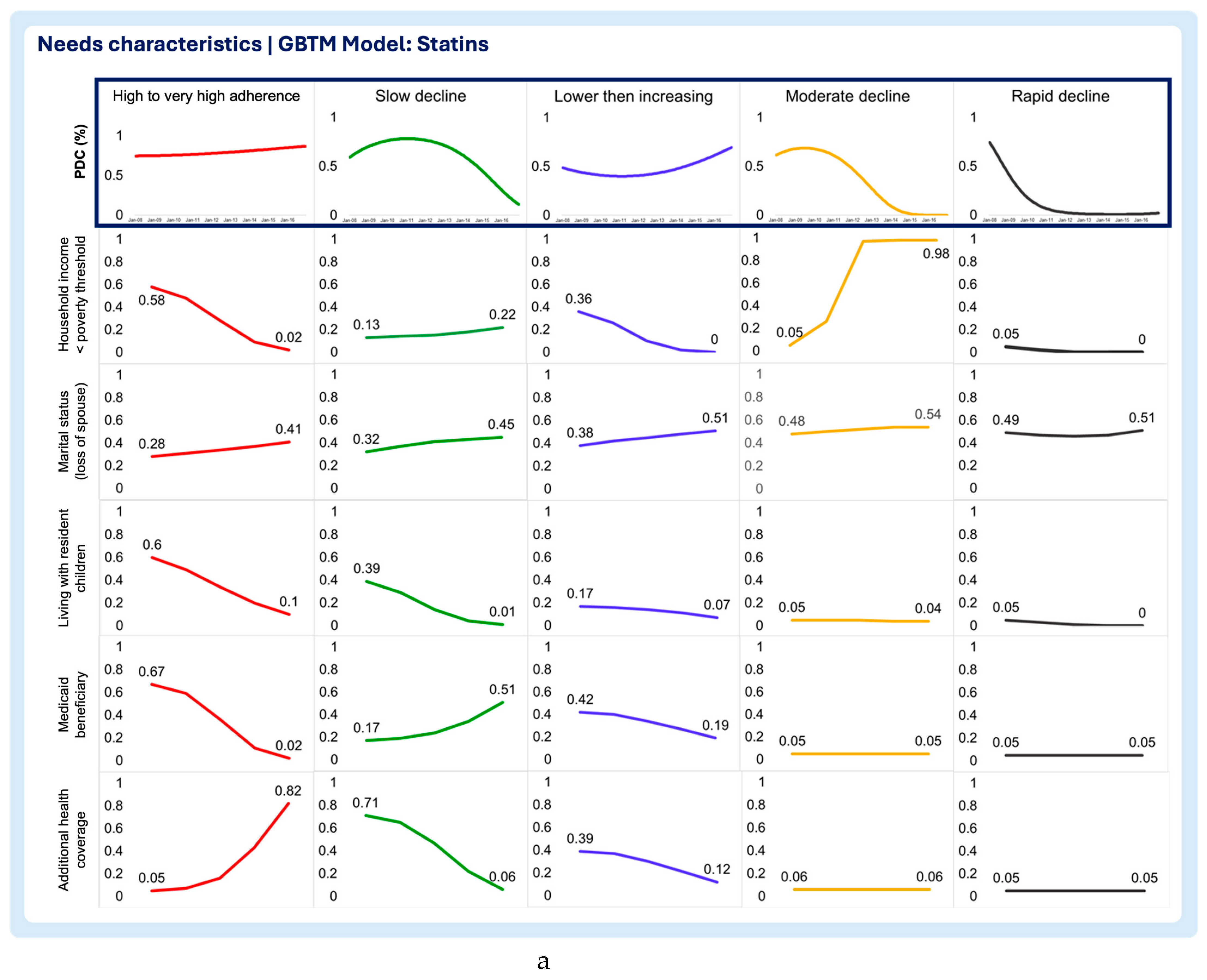

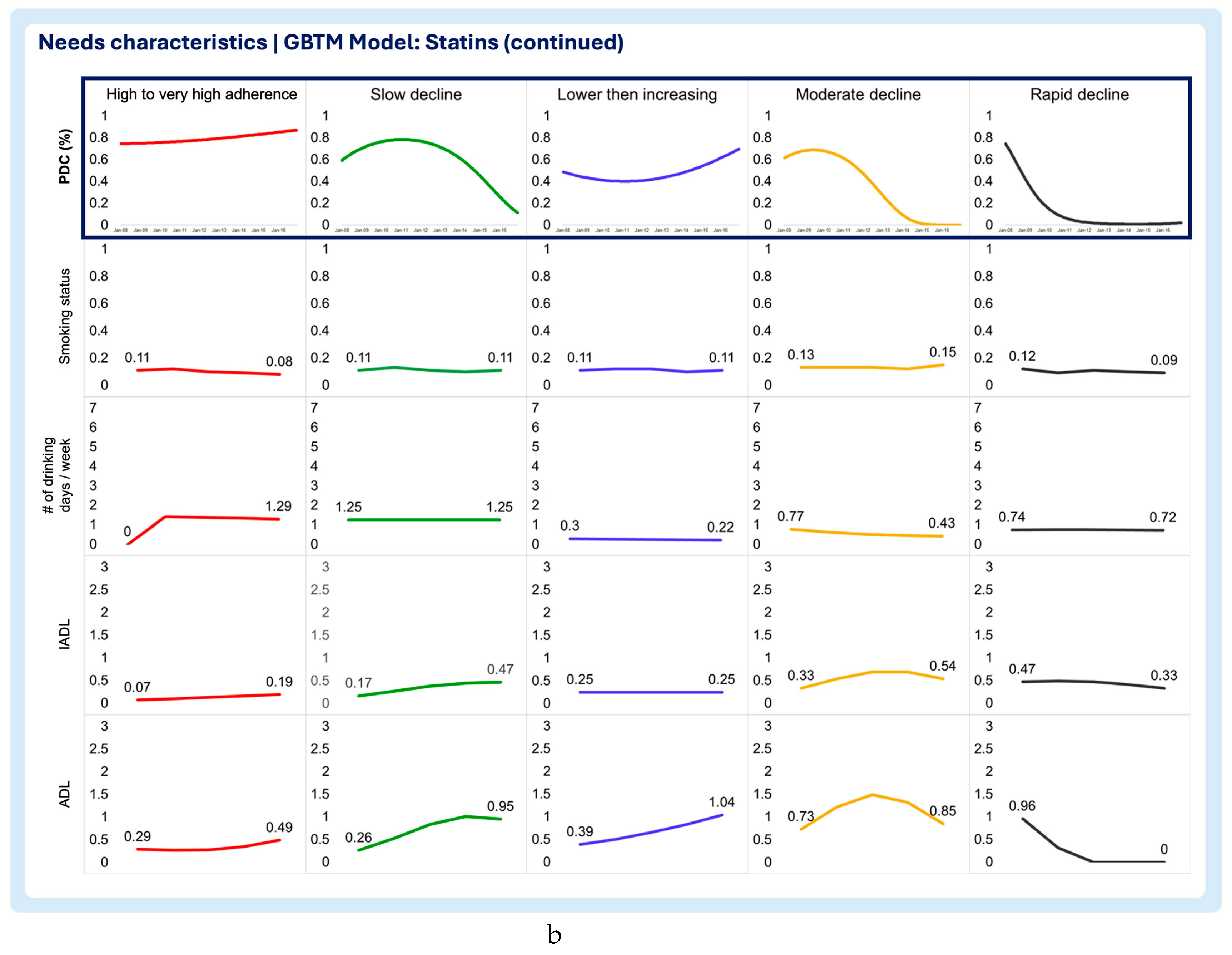

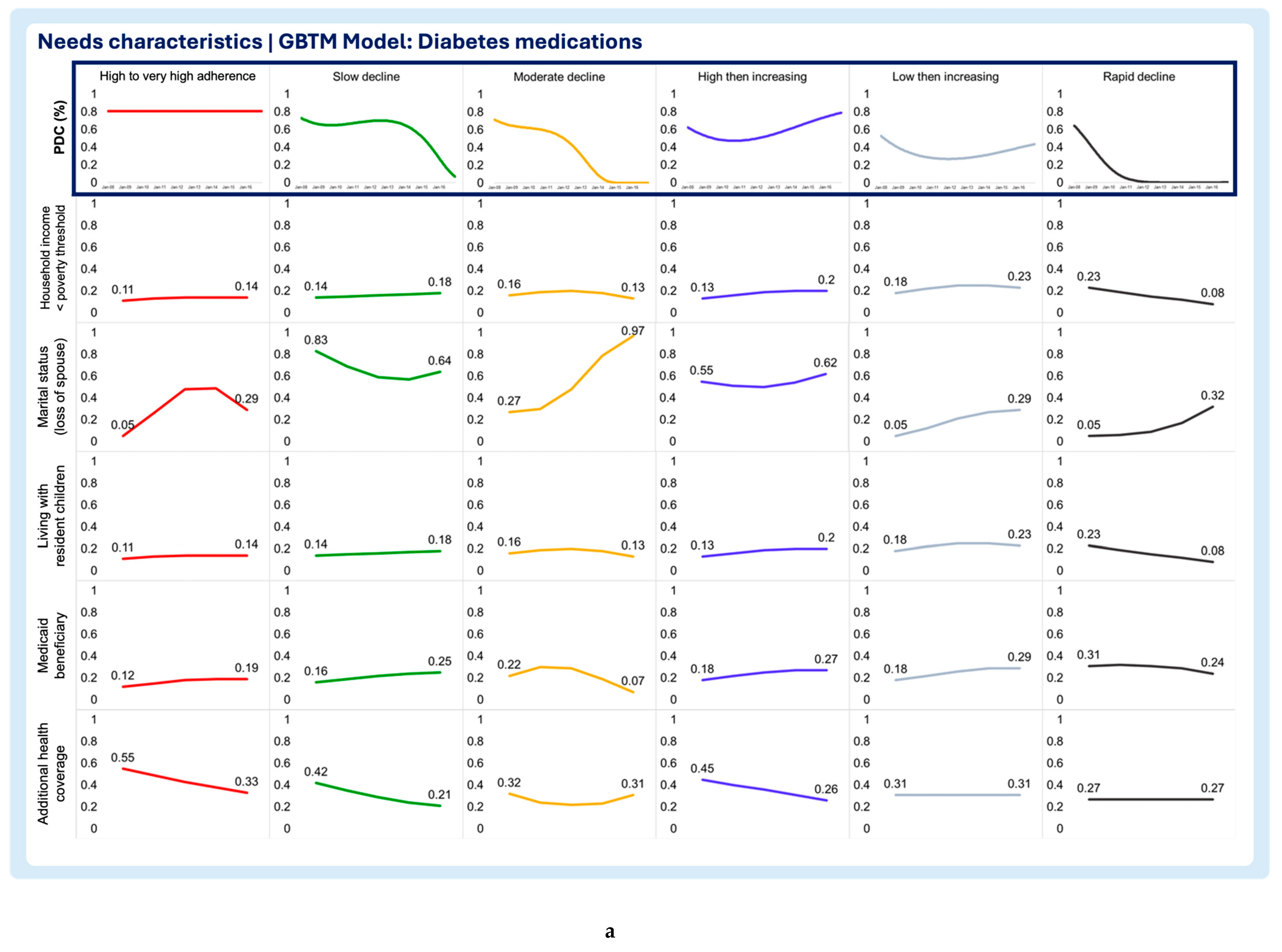

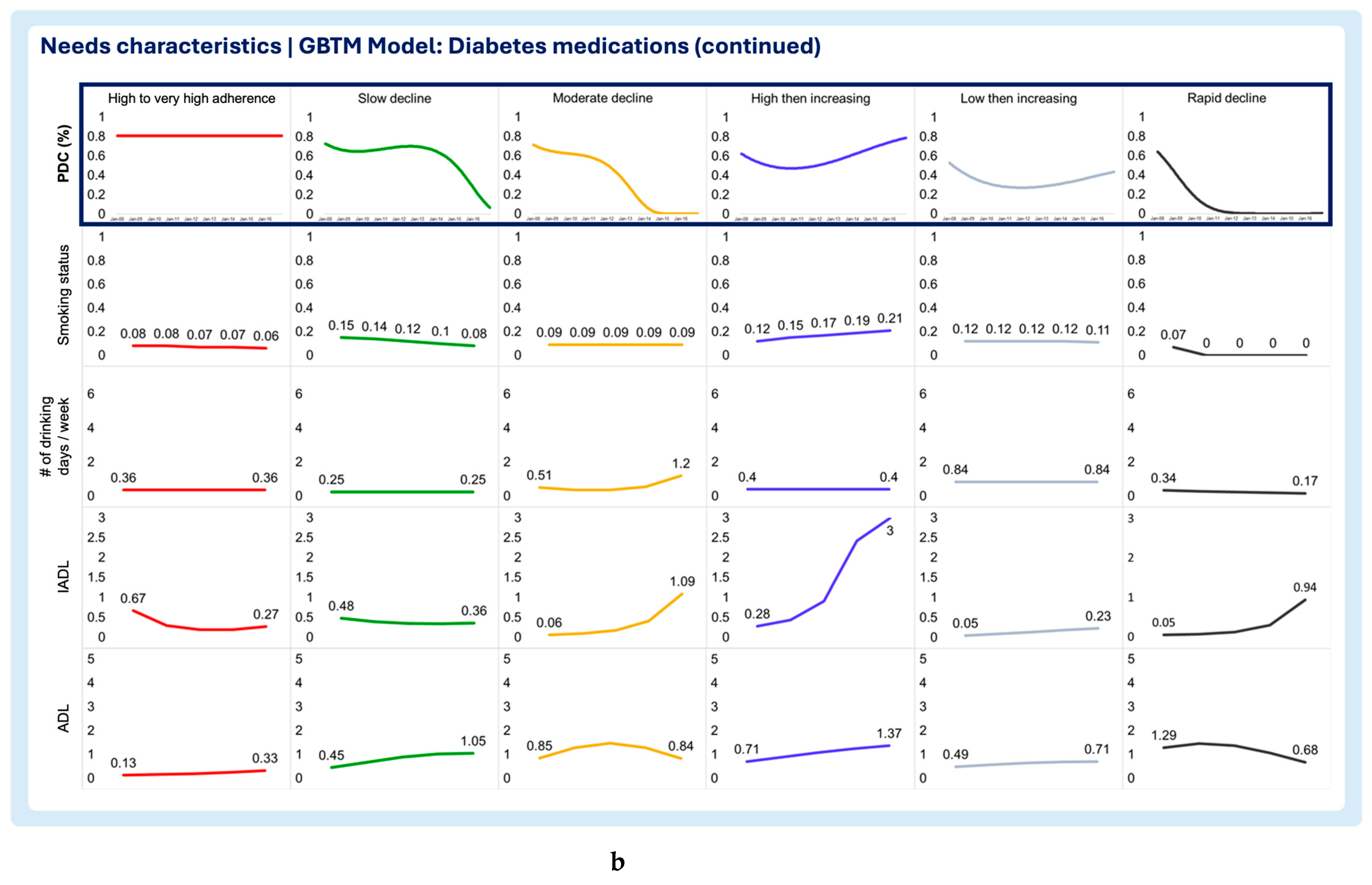

- 2. Needs characteristics

- Household income below poverty threshold

- Marital status (loss of spouse)

- Living with resident children

- Medicaid beneficiary

- Additional health coverage

- Smoking status

- Number of drinking days / week

- Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL)

- Activities of Daily Living (ADL)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GBTM | Group-based trajectory modeling |

| PDC | Proportion of Days Covered |

| HRS | Health & Retirement Study |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| IADL | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

Appendix A

| Characteristic | Covariates | Measurement approach |

|---|---|---|

| Enabling characteristics | Self-reported health status | 5-point scale: 1 - Excellent 2 – Very good 3 - Good 4 - Fair 5 - Poor |

| Depression symptoms | CES-D 8-Item Scale. Per Steffick and colleagues, a score > 3 is indicative of clinical depression24 0 – No depression symptoms (CES-D score ≤3) 1 – With depression symptoms (CES-D score >3) |

|

| Life Satisfaction | 5-point scale: 1 – Completely satisfied 2 – Very satisfied 3 – Somewhat satisfied 4 – Not very satisfied 5 – Not at all satisfied |

|

| Retirement Satisfaction | 3-point scale: 1 – Very satisfying 2 – Moderately satisfying 3 – Not at all satisfying |

|

| Limitations in work due to health | Yes (1) / No (0) | |

| Need characteristics | Poverty threshold | Below (1) / Above (0) |

Family structure

|

Yes (1) / No (0) Yes (1) / No (0) |

|

| Medicaid beneficiary | Yes (1) / No (0) | |

| Additional health coverage | Yes (1) / No (0) | |

Substance abuse

|

Yes (1) / No (0) Number of drinking days / week |

|

Assistance with activities

|

Number of activities requiring assistance/can’t perform |

|

| CES-D: 8-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale [46] | ||

Appendix B

| GBTM MODEL | Select hypertensives | Statins | Diabetes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | VIF | R-Squared | VIF | R-Squared | VIF | R-Squared |

| Predisposing and antecedents | ||||||

| Sex: Female | 1.170 | 0.144 | 1.150 | 0.130 | 1.220 | 0.179 |

| Birthplace: Foreign born | 1.430 | 0.299 | 1.470 | 0.320 | 1.590 | 0.372 |

| Race: Non-white | 1.200 | 0.165 | 1.180 | 0.153 | 1.190 | 0.162 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 1.530 | 0.347 | 1.550 | 0.357 | 1.740 | 0.425 |

| Education: Not College educated | 1.820 | 0.451 | 1.850 | 0.459 | 1.790 | 0.440 |

| Enabling characteristics | ||||||

| Self-reported Health Status | 1.550 | 0.355 | 1.500 | 0.332 | 1.470 | 0.319 |

| Depression Symptoms | 1.930 | 0.482 | 2.010 | 0.502 | 1.960 | 0.490 |

| Life Satisfaction | 1.280 | 0.216 | 1.260 | 0.204 | 1.260 | 0.205 |

| Retirement Satisfaction | 1.310 | 0.237 | 1.320 | 0.242 | 1.240 | 0.191 |

| Limitations in work due to health | 1.270 | 0.211 | 1.290 | 0.224 | 1.300 | 0.232 |

| Need characteristics | ||||||

| Household income below poverty index | 1.340 | 0.252 | 1.330 | 0.251 | 1.340 | 0.256 |

| Marital spouse: Loss of spouse | 1.220 | 0.182 | 1.200 | 0.169 | 1.280 | 0.218 |

| Number of resident children | 1.080 | 0.074 | 1.080 | 0.075 | 1.060 | 0.057 |

| Medicaid eligibility | 1.320 | 0.245 | 1.320 | 0.241 | 1.360 | 0.263 |

| Additional health coverage | 1.130 | 0.118 | 1.120 | 0.110 | 1.180 | 0.155 |

| Smoking status: Smoker | 1.050 | 0.051 | 1.060 | 0.054 | 1.030 | 0.029 |

| Number of drinking days / week | 1.140 | 0.119 | 1.100 | 0.093 | 1.080 | 0.070 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living | 1.360 | 0.263 | 1.410 | 0.289 | 1.550 | 0.356 |

| Activities of Daily Living | 1.510 | 0.336 | 1.510 | 0.339 | 1.760 | 0.432 |

| Mean VIF | 1.381 | 1.389 | 1.410 | |||

References

- Arlt S, Lindner R, Rosler A, von Renteln-Kruse W. Adherence to medication in patients with dementia: predictors and strategies for improvement. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1033-47. [CrossRef]

- Bowry AD, Shrank WH, Lee JL, Stedman M, Choudhry NK. A systematic review of adherence to cardiovascular medications in resource-limited settings. J Gen Intern Med. Dec 2011;26(12):1479-91. [CrossRef]

- Coletti DJ, Stephanou H, Mazzola N, Conigliaro J, Gottridge J, Kane JM. Patterns and predictors of medication discrepancies in primary care. J Eval Clin Pract. Oct 2015;21(5):831-9. [CrossRef]

- Gard PR. Non-adherence to antihypertensive medication and impaired cognition: which comes first? Int J Pharm Pract. Oct 2010;18(5):252-9. [CrossRef]

- Hudani ZK, Rojas-Fernandez CH. A scoping review on medication adherence in older patients with cognitive impairment or dementia. Res Social Adm Pharm. Nov-Dec 2016;12(6):815-829. [CrossRef]

- Lenti MV, Selinger CP. Medication non-adherence in adult patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease: a critical review and update of the determining factors, consequences and possible interventions. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. Mar 2017;11(3):215-226. [CrossRef]

- Warren JR, Falster MO, Fox D, Jorm L. Factors influencing adherence in long-term use of statins. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. Dec 2013;22(12):1298-307. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for action. World Health Organization. Accessed 20/01/2020. https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s4883e/s4883e.pdf.

- Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. Apr 2011;86(4):304-14. [CrossRef]

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. Mar 1995;36(1):1-10.

- Andersen RM, Davidson PL, Baumeister SE. Improving access to care in America. Changing the US health care system: key issues in health services policy and management. 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass; 2007:3-31.

- Alhazami M, Pontinha VM, Patterson JA, Holdford DA. Medication Adherence Trajectories: A Systematic Literature Review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. Sep 2020;26(9):1138-1152. [CrossRef]

- Ajrouche A, Estellat C, De Rycke Y, Tubach F. Trajectories of Adherence to Low-Dose Aspirin Treatment Among the French Population. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. Jan 2020;25(1):37-46. [CrossRef]

- Dillon P, Stewart D, Smith SM, Gallagher P, Cousins G. Group-Based Trajectory Models: Assessing Adherence to Antihypertensive Medication in Older Adults in a Community Pharmacy Setting. Clin Pharmacol Ther. Jun 2018;103(6):1052-1060. [CrossRef]

- Feldman CH, Collins J, Zhang Z, et al. Dynamic patterns and predictors of hydroxychloroquine nonadherence among Medicaid beneficiaries with systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. Oct 2018;48(2):205-213. [CrossRef]

- Franklin JM, Krumme AA, Shrank WH, Matlin OS, Brennan TA, Choudhry NK. Predicting adherence trajectory using initial patterns of medication filling. Am J Manag Care. Sep 1 2015;21(9):e537-44.

- Franklin JM, Shrank WH, Pakes J, et al. Group-based trajectory models: a new approach to classifying and predicting long-term medication adherence. Med Care. Sep 2013;51(9):789-96. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez I, He M, Chen N, Brooks MM, Saba S, Gellad WF. Trajectories of Oral Anticoagulation Adherence Among Medicare Beneficiaries Newly Diagnosed With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. Jun 18 2019;8(12):e011427. [CrossRef]

- Nagin DS, Jones BL, Passos VL, Tremblay RE. Group-based multi-trajectory modeling. Stat Methods Med Res. Jul 2018;27(7):2015-2023. [CrossRef]

- Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press; 2005.

- Nagin DS. Group-based trajectory modeling: an overview. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;65(2-3):205-10. [CrossRef]

- Pontinha VM, Patterson JA, Dixon DL, et al. Longitudinal medication adherence group-based trajectories of aging adults in the US: A retrospective analysis using monthly proportion of days covered calculations. Res Social Adm Pharm. Dec 27 2023;doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2023.12.008.

- RAND Center for the Study of Aging. RAND HRS Longitudinal File 2016 (V2) Documentation. Accessed 03/05/2020. https://hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/documentation/codebooks/randhrs1992_2016v2.pdf.

- Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. StataCorp LLC; 2021.

- Jones BL, Nagin DS. A Note on a Stata Plugin for Estimating Group-based Trajectory Models. Sociological Methods & Research. 2013/11/01 2013;42(4):608-613. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery DC. Introduction to linear regression analysis. Fifth edition. ed. Wiley; 2013.

- Kutner MH, Nachtsheim C, Neter J. Applied linear regression models. 4th / ed. vol Boston ; New York :. McGraw-Hill/Irwin; 2004.

- Burckhardt P, Nagin DS, Padman R. Multi-Trajectory Models of Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2016;2016:1737-1746.

- Woolpert KM, Schmidt JA, Ahern TP, et al. Clinical factors associated with patterns of endocrine therapy adherence in premenopausal breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Apr 8 2024;26(1):59. [CrossRef]

- Fatima B, Mohan A, Altaie I, Abughosh S. Predictors of adherence to direct oral anticoagulants after cardiovascular or bleeding events in Medicare Advantage Plan enrollees with atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. May 2024;30(5):408-419. [CrossRef]

- Chang CY, Jones BL, Hincapie-Castillo JM, et al. Association between trajectories of adherence to endocrine therapy and risk of treated breast cancer recurrence among US nonmetastatic breast cancer survivors. Br J Cancer. Jun 2024;130(12):1943-1950. [CrossRef]

- Wabe N, Timothy A, Urwin R, Xu Y, Nguyen A, Westbrook JI. Analysis of Longitudinal Patterns and Predictors of Medicine Use in Residential Aged Care Using Group-Based Trajectory Modeling: The "MEDTRAC-Cardiovascular" Longitudinal Cohort Study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. Aug 2024;33(8):e5881. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt JA, Woolpert KM, Hjorth CF, Farkas DK, Ejlertsen B, Cronin-Fenton D. Social Characteristics and Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Premenopausal Women With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. Jun 25 2024:JCO2302643. [CrossRef]

- Mohan A, Chen H, Deshmukh AA, et al. Group-based trajectory modeling to identify adherence patterns for direct oral anticoagulants in Medicare beneficiaries with atrial fibrillation: a real-world study on medication adherence. Int J Clin Pharm. Aug 27 2024;doi:10.1007/s11096-024-01786-y.

- Ishiwata R, AlAshqar A, Miyashita-Ishiwata M, Borahay MA. Dispensing patterns of antidepressant and antianxiety medications for psychiatric disorders after benign hysterectomy in reproductive-age women: Results from group-based trajectory modeling. Womens Health (Lond). Jan-Dec 2024;20:17455057241272218. [CrossRef]

- Huang W, Ahmed MM, Morris EJ, et al. Trajectories of Sacubitril/Valsartan Adherence Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Heart Failure. JACC Adv. Jul 2024;3(7):100958. [CrossRef]

- Abegaz TM, Shehab A, Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, Elnour AA. Nonadherence to antihypertensive drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). Jan 2017;96(4):e5641. [CrossRef]

- Ruksakulpiwat S, Schiltz NK, Irani E, Josephson RA, Adams J, Still CH. Medication Adherence of Older Adults with Hypertension: A Systematic Review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2024;18:957-975. [CrossRef]

- Stentzel U, van den Berg N, Schulze LN, et al. Predictors of medication adherence among patients with severe psychiatric disorders: findings from the baseline assessment of a randomized controlled trial (Tecla). BMC Psychiatry. May 29 2018;18(1):155. BMC Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Cummings P. The relative merits of risk ratios and odds ratios. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. May 2009;163(5):438-45. [CrossRef]

- Greenland S. Interpretation and choice of effect measures in epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol. May 1987;125(5):761-8. [CrossRef]

- Park KH, Tickle L, Cutler H. Identifying temporal patterns of adherence to antidepressants, bisphosphonates and statins, and associated patient factors. SSM - Population Health. 2022/03/01/ 2022;17:100973. [CrossRef]

- Wang CH, Huang LC, Yang CC, et al. Short- and long-term use of medication for psychological distress after the diagnosis of cancer. Support Care Cancer. Mar 2017;25(3):757-768. [CrossRef]

- Hsu YH, Mao CL, Wey M. Antihypertensive medication adherence among elderly Chinese Americans. J Transcult Nurs. Oct 2010;21(4):297-305. [CrossRef]

- Bird GC, Cannon CP, Kennison RH. Results of a survey assessing provider beliefs of adherence barriers to antiplatelet medications. Crit Pathw Cardiol. Sep 2011;10(3):134-41. [CrossRef]

- Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. Jun 1999;11(2):139-48. [CrossRef]

| WHO Report: Causes of Non-Adherence | ||||||

| Socioeconomic | Health care team / Health care system | Disease-related factors | Therapy-related factors | Patient-related factors | ||

| Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Services Use | Predisposing characteristics | Education, race, ethnicity, income, occupation, marital status | Trust in medical organizations/health care team | Health-beliefs | Transportation, distance to health services, substance abuse | |

| Enabling factors | Urbanicity, Medicaid eligibility | Access to health care services, wait times, difficulty filling prescriptions, cost, health information, integration of health care team, physician-patient communication, facetime with health care providers | Health insurance, social/family support, health literacy | |||

| Need characteristics | Evaluated health-status, comorbidities (MI, stroke, cancer), severity, symptoms | Treatment complexity, route of administration, side effects, duration, degree of behavioral change required | Activities of daily living, limitations in activities/profession, risk-factors (obesity, smoking, alcohol use) | |||

| Sample Characteristics | Frequency of study participants (n,%) | Missing Data |

| N = 11,068 | (n, %) | |

| Predisposing and antecedents | ||

| Sex (n=11,068) | 0, 0% | |

| Female | 6,724, 60.75% | |

| Birthplace (n=9,564) | 1,504, 13.58% | |

| US-born | 8,475, 88.61% | |

| Race (n=11,057) | 11, 0.09% | |

| Non-white | 2,597, 23.49% | |

| Ethnicity (n=11,058) | 10, 0.09% | |

| Hispanic | 1,302, 11.77% | |

| Education (n=11,068) | 0, 0% | |

| Has college degree or higher | 2,263, 20.45% | |

| Enabling characteristics | ||

| Self-reported health status (n=6,308) | 4,760, 43.01% | |

| Excellent | 282, 4.47% | |

| Very good | 1,349, 21.39% | |

| Good | 2,127, 33.72% | |

| Fair | 1,826, 28.95% | |

| Poor | 724, 11.48% | |

| Depression symptoms (n=9,432) | 1,636, 14.78% | |

| With clinical depression* | 1,919, 20.35% | |

| Life Satisfaction (n=1,761) | 9,307, 84.09% | |

| Completely satisfied | 395, 22.43% | |

| Very satisfied | 726, 41.23% | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 528, 29.98% | |

| Not very satisfied | 85, 4.83% | |

| Not at all satisfied | 27, 1.53% | |

| Retirement Satisfaction (n=4,667) | 6,401, 57.83% | |

| Very Satisfied | 2,132, 45.68% | |

| Moderately satisfied | 2,048, 43.88% | |

| Not at all satisfied | 487, 10.43% | |

| Limitations in work due to health (n=5,977) | ||

| Yes | 3,435, 57.47% | 5,091, 46.00% |

| Need characteristics | ||

| Poverty Index (n=9,609) | 1,459, 13.18% | |

| Household income below poverty threshold | 1,426, 14,84% | |

| Marital Status (n=9,805) | 1,263, 11.41% | |

| Loss of spouse or never married** | 5,404, 55.11% | |

| Lives with spouse, partner | 4,401, 44.89% | |

| Number of resident children (n=6,320) | 4,748, 42,90% | |

| Does not live with resident children | 4,852, 76.77% | |

| Lives with resident children | 1,468, 23.23% | |

| Medicaid eligibility (n=9,798) | 1270, 11.47% | |

| Medicaid beneficiary | 2,007, 20.48% | |

| Additional health insurance coverage (n=6,216) | 4,852, 43,84% | |

| Has additional insurance | 1,920, 30.89% | |

| Smoking status (n=9,749) | 1319, 11.91% | |

| Smokers | 986, 10.11% | |

| Number of drinking days per week (n=6,294) | 4,774, 43.13% | |

| 0 or doesn’t drink | 4,473, 71.07% | |

| 1 | 658, 10.45% | |

| 2 | 304, 4.83% | |

| 3 | 245, 3.89% | |

| 4 | 102, 1.62% | |

| 5 | 124, 1.97% | |

| 6 | 52, 0.83% | |

| 7 | 336, 5.34% | |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (n=9,822) | 1,246, 11.25% | |

| 0 (Highly functional) | 7,458, 75.93% | |

| 1 | 1,035, 10.54% | |

| 2 | 605, 6.16% | |

| 3 (Not functional) | 724, 7.37% | |

| Activities of Daily Living (n=9,822) | 1,246, 11.25% | |

| 0 (Completely independent) | 6,316, 64.3% | |

| 1 | 1,160, 11.81% | |

| 2 | 735, 7.48% | |

| 3 | 504, 5.13% | |

| 4 | 486, 4.95% | |

| 5 (Totally dependent) | 621, 6.32% | |

| Pharmacotherapeutic class*** | ||

| Select antihypertensives | 7,727, 69.81% | |

| Blood cholesterol lowering drugs | 8,221, 74.28% | |

| Oral diabetes medications | 3,214, 29.04% | |

| * The CESD-8 (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression 8-item) scale is a validated instrument to measure depressive symptoms. Per Steffick and colleagues, a score > 3 is indicative of clinical depression24 | ||

| ** Loss of spouse due to death, separation, or divorce | ||

| *** Participants could be taking concomitant drug from more than one pharmacotherapeutic class | ||

| TRAJECTORY | Rapid Declinea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBTM MODEL | Select antihypertensives | Statins | Oral diabetes medications | |||||||||

| Coeff. | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Coeff. | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Coeff. | S.E. | aOR | p-value | |

| Predisposing and antecedents | ||||||||||||

| Sex: Female | 0.11 | 0.12 | 1.11 | 0.392 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 1.18 | 0.273 | -0.01 | 0.29 | 0.99 | 0.980 |

| Birthplace: Foreign born | 0.00 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.988 | 0.91 | 0.24 | 2.48 | 0.000* | 0.19 | 0.44 | 1.21 | 0.673 |

| Race: Non-white | -0.01 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 0.938 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 1.18 | 0.374 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 1.16 | 0.630 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | -0.25 | 0.22 | 0.78 | 0.247 | -0.13 | 0.26 | 0.88 | 0.619 | 0.08 | 0.42 | 1.08 | 0.848 |

| Education: Not College educated | -0.03 | 0.18 | 0.97 | 0.858 | 0.52 | 0.22 | 1.67 | 0.018* | 0.21 | 0.40 | 1.23 | 0.606 |

| Enabling characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Self-reported Health Status | 0.03 | 0.07 | 1.03 | 0.646 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 1.11 | 0.540 |

| Depression Symptoms | 0.60 | 0.17 | 1.82 | 0.000* | 0.39 | 0.22 | 1.48 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 1.18 | 0.691 |

| Life Satisfaction | 0.16 | 0.07 | 1.17 | 0.025* | 0.02 | 0.09 | 1.02 | 0.86 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 1.15 | 0.392 |

| Retirement Satisfaction | -0.03 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.753 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 1.10 | 0.45 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 1.18 | 0.455 |

| Limitations in work due to health | 0.17 | 0.13 | 1.19 | 0.181 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 1.25 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 1.37 | 0.306 |

| Need characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Household income below poverty index | 0.12 | 0.18 | 1.13 | 0.512 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.42 | 1.14 | 0.756 |

| Marital status: Loss of spouse | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.01 | 0.617 | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 0.293 |

| Lives with resident children | 0.03 | 0.11 | 1.03 | 0.769 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 1.10 | 0.51 | -0.16 | 0.25 | 0.85 | 0.509 |

| Medicaid beneficiary | -0.11 | 0.17 | 0.90 | 0.539 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 1.14 | 0.55 | -1.39 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.010* |

| Additional health coverage | -0.02 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.869 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 1.35 | 0.307 |

| Smoking status: Smoker | 0.40 | 0.18 | 1.49 | 0.028* | 0.76 | 0.22 | 2.13 | 0.00* | 0.85 | 0.43 | 2.35 | 0.046* |

| Number of drinking days / week | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.04 | 0.159 | -0.02 | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.58 | -0.11 | 0.10 | 0.89 | 0.263 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living | 0.01 | 0.12 | 1.01 | 0.937 | 0.63 | 0.15 | 1.88 | 0.00* | -0.09 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.768 |

| Activities of Daily Living | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.09 | 0.158 | -0.14 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 0.10 | -0.01 | 0.16 | 0.99 | 0.937 |

| aThe trajectory of rapid decline in medication adherence was observed all of the models of select antihypertensives, statins, and diabetes medications | ||||||||||||

| TRAJECTORY | Slow declinea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBTM MODEL | Select antihypertensives | Statins | Oral diabetes medications | |||||||||

| Coeff. | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Coeff. | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Coeff. | S.E. | aOR | p-value | |

| Predisposing and antecedents | ||||||||||||

| Sex: Female | 0.10 | 0.09 | 1.11 | 0.254 | -0.02 | 0.11 | 0.98 | 0.846 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 1.24 | 0.245 |

| Birthplace: Foreign born | 0.03 | 0.14 | 1.03 | 0.831 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 1.10 | 0.637 | 0.66 | 0.28 | 1.93 | 0.017* |

| Race: Non-white | 0.37 | 0.10 | 1.44 | 0.000* | 0.23 | 0.13 | 1.26 | 0.084 | -0.09 | 0.20 | 0.91 | 0.645 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 0.04 | 0.14 | 1.04 | 0.784 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 1.17 | 0.421 | -0.56 | 0.28 | 0.57 | 0.050* |

| Education: Not College educated | 0.06 | 0.13 | 1.06 | 0.633 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 1.27 | 0.143 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 1.40 | 0.212 |

| Enabling characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Self-reported Health Status | 0.22 | 0.05 | 1.24 | 0.000* | 0.15 | 0.06 | 1.16 | 0.013* | 0.14 | 0.10 | 1.14 | 0.188 |

| Depression Symptoms | 0.23 | 0.13 | 1.26 | 0.066 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 1.23 | 0.198 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 1.65 | 0.042* |

| Life Satisfaction | -0.04 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.398 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 1.02 | 0.817 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 1.05 | 0.654 |

| Retirement Satisfaction | -0.04 | 0.07 | 0.96 | 0.588 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 1.09 | 0.325 | -0.09 | 0.14 | 0.91 | 0.510 |

| Limitations in work due to health | 0.04 | 0.09 | 1.04 | 0.700 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 1.19 | 0.133 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 1.42 | 0.065 |

| Need characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Household income below poverty index | 0.05 | 0.13 | 1.05 | 0.697 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 1.37 | 0.075 | -0.30 | 0.26 | 0.74 | 0.259 |

| Marital status: Loss of spouse | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.01 | 0.562 | -0.01 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.506 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 0.693 |

| Lives with resident children | 0.09 | 0.08 | 1.09 | 0.254 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 1.16 | 0.145 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1.14 | 0.322 |

| Medicaid beneficiary | -0.11 | 0.12 | 0.90 | 0.384 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 1.02 | 0.931 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 1.01 | 0.982 |

| Additional health coverage | -0.18 | 0.09 | 0.84 | 0.057 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 1.19 | 0.112 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 1.59 | 0.016* |

| Smoking status: Smoker | -0.03 | 0.15 | 0.97 | 0.855 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 1.12 | 0.543 | 0.09 | 0.32 | 1.09 | 0.784 |

| Number of drinking days / week | 0.05 | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.017* | 0.00 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.986 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 1.04 | 0.459 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living | 0.05 | 0.09 | 1.06 | 0.557 | 0.42 | 0.12 | 1.52 | 0.000 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 1.31 | 0.104 |

| Activities of Daily Living | 0.01 | 0.05 | 1.01 | 0.783 | -0.09 | 0.06 | 0.92 | 0.151 | -0.01 | 0.09 | 0.99 | 0.949 |

| aThe trajectory of slow decline in medication adherence was observed all of the models of select antihypertensives, statins, and diabetes medications | ||||||||||||

| TRAJECTORY | Moderate Declinea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBTM MODEL | Select antihypertensives | Statins | Oral diabetes medications | |||||||||

| Coeff. | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Coeff. | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Coeff. | S.E. | aOR | p-value | |

| Predisposing and antecedents | ||||||||||||

| Sex: Female | - | - | - | - | 0.40 | 0.12 | 1.50 | 0.001* | 0.25 | 0.17 | 1.28 | 0.149 |

| Birthplace: Foreign born | - | - | - | - | 0.56 | 0.20 | 1.75 | 0.006* | 0.05 | 0.27 | 1.05 | 0.862 |

| Race: Non-white | - | - | - | - | 0.69 | 0.14 | 2.00 | 0.000* | -0.37 | 0.19 | 0.69 | 0.054 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | - | - | - | - | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1.23 | 0.311 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 1.15 | 0.564 |

| Education: Not College educated | - | - | - | - | 0.07 | 0.18 | 1.07 | 0.704 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 1.28 | 0.333 |

| Enabling characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Self-reported Health Status | - | - | - | - | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.09 | 0.196 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 1.15 | 0.153 |

| Depression Symptoms | - | - | - | - | 0.23 | 0.17 | 1.26 | 0.175 | 0.79 | 0.23 | 2.20 | 0.001* |

| Life Satisfaction | - | - | - | - | 0.10 | 0.07 | 1.10 | 0.159 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 1.14 | 0.187 |

| Retirement Satisfaction | - | - | - | - | 0.14 | 0.10 | 1.15 | 0.137 | -0.01 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 0.966 |

| Limitations in work due to health | - | - | - | - | 0.02 | 0.13 | 1.02 | 0.889 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 1.08 | 0.677 |

| Need characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Household income below poverty index | - | - | - | - | 0.25 | 0.18 | 1.29 | 0.163 | -0.30 | 0.25 | 0.74 | 0.231 |

| Marital status: Loss of spouse | - | - | - | - | -0.02 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.326 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.973 |

| Lives with resident children | - | - | - | - | 0.02 | 0.11 | 1.02 | 0.836 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.997 |

| Medicaid beneficiary | - | - | - | - | 0.21 | 0.17 | 1.23 | 0.223 | -0.09 | 0.23 | 0.92 | 0.706 |

| Additional health coverage | - | - | - | - | -0.08 | 0.13 | 0.92 | 0.529 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 1.01 | 0.978 |

| Smoking status: Smoker | - | - | - | - | 0.38 | 0.19 | 1.46 | 0.049* | 0.18 | 0.31 | 1.19 | 0.566 |

| Number of drinking days / week | - | - | - | - | -0.05 | 0.03 | 0.96 | 0.165 | -0.08 | 0.06 | 0.92 | 0.149 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living | - | - | - | - | 0.24 | 0.13 | 1.27 | 0.061 | -0.07 | 0.17 | 0.93 | 0.684 |

| Activities of Daily Living | - | - | - | - | -0.09 | 0.07 | 0.92 | 0.179 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 1.01 | 0.871 |

| aThe trajectory of moderate decline in medication adherence was observed only in the models of statins and diabetes medications | ||||||||||||

| TRAJECTORY | Low then increasing adherencea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBTM MODEL | Select antihypertensives | Statins | Oral diabetes medications | |||||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Estimate | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Estimate | S.E. | aOR | p-value | |

| Predisposing and antecedents | ||||||||||||

| Sex: Female | - | - | - | - | 0.06 | 0.10 | 1.06 | 0.561 | 0.71 | 0.20 | 2.02 | 0.001* |

| Birthplace: Foreign born | - | - | - | - | 0.48 | 0.18 | 1.62 | 0.009* | 0.05 | 0.29 | 1.05 | 0.868 |

| Race: Non-white | - | - | - | - | 0.30 | 0.13 | 1.35 | 0.019* | 0.26 | 0.20 | 1.30 | 0.189 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | - | - | - | - | 0.02 | 0.18 | 1.02 | 0.930 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 1.15 | 0.599 |

| Education: Not College educated | - | - | - | - | 0.15 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.334 | -0.47 | 0.32 | 0.63 | 0.136 |

| Enabling characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Self-reported Health Status | - | - | - | - | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.08 | 0.168 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 1.01 | 0.946 |

| Depression Symptoms | - | - | - | - | 0.19 | 0.15 | 1.21 | 0.213 | 0.71 | 0.26 | 2.04 | 0.005* |

| Life Satisfaction | - | - | - | - | -0.11 | 0.06 | 0.90 | 0.078 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 1.37 | 0.004* |

| Retirement Satisfaction | - | - | - | - | 0.16 | 0.08 | 1.17 | 0.055 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 1.02 | 0.897 |

| Limitations in work due to health | - | - | - | - | 0.17 | 0.11 | 1.18 | 0.114 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 1.17 | 0.456 |

| Need characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Household income below poverty index | - | - | - | - | -0.12 | 0.17 | 0.88 | 0.473 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 1.00 | 0.990 |

| Marital status: Loss of spouse | - | - | - | - | -0.03 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.098 | -0.03 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.420 |

| Lives with resident children | - | - | - | - | 0.07 | 0.10 | 1.07 | 0.467 | -0.24 | 0.16 | 0.79 | 0.121 |

| Medicaid beneficiary | - | - | - | - | 0.16 | 0.15 | 1.17 | 0.310 | -0.34 | 0.25 | 0.71 | 0.174 |

| Additional health coverage | - | - | - | - | -0.06 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 0.574 | -0.32 | 0.23 | 0.73 | 0.168 |

| Smoking status: Smoker | - | - | - | - | 0.16 | 0.18 | 1.17 | 0.368 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 1.58 | 0.150 |

| Number of drinking days / week | - | - | - | - | -0.02 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.454 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 1.01 | 0.885 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living | - | - | - | - | 0.08 | 0.12 | 1.09 | 0.490 | -0.07 | 0.18 | 0.93 | 0.681 |

| Activities of Daily Living | - | - | - | - | 0.01 | 0.06 | 1.01 | 0.843 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 1.10 | 0.283 |

| aThe trajectory of low then increasing medication adherence was observed only in the models of statins and diabetes medications | ||||||||||||

| TRAJECTORY | High then increasing adherencea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBTM MODEL | Select antihypertensives | Statins | Oral diabetes medications | |||||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Estimate | S.E. | aOR | p-value | Estimate | S.E. | aOR | p-value | |

| Predisposing and antecedents | ||||||||||||

| Sex: Female | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.23 | 0.19 | 1.26 | 0.221 |

| Birthplace: Foreign born | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.20 | 0.30 | 1.22 | 0.511 |

| Race: Non-white | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.36 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.092 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.43 | 0.30 | 0.65 | 0.146 |

| Education: Not College educated | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.31 | 0.30 | 0.74 | 0.313 |

| Enabling characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Self-reported Health Status | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.08 | 0.10 | 1.08 | 0.444 |

| Depression Symptoms | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.29 | 0.25 | 1.34 | 0.253 |

| Life Satisfaction | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.01 | 0.11 | 1.01 | 0.947 |

| Retirement Satisfaction | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.19 | 0.15 | 0.83 | 0.212 |

| Limitations in work due to health | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.11 | 0.20 | 1.12 | 0.571 |

| Need characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Household income below poverty index | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.40 | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.147 |

| Marital status: Loss of spouse | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.03 | 0.04 | 1.03 | 0.465 |

| Lives with resident children | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.09 | 0.15 | 0.91 | 0.527 |

| Medicaid beneficiary | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.08 | 0.25 | 1.08 | 0.747 |

| Additional health coverage | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.09 | 0.21 | 1.09 | 0.686 |

| Smoking status: Smoker | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.22 | 0.33 | 1.25 | 0.504 |

| Number of drinking days / week | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.06 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.342 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.05 | 0.18 | 1.05 | 0.770 |

| Activities of Daily Living | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.12 | 0.09 | 1.12 | 0.201 |

| aThe trajectory of high then increasing medication adherence was observed only in the models of diabetes medications | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).