Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

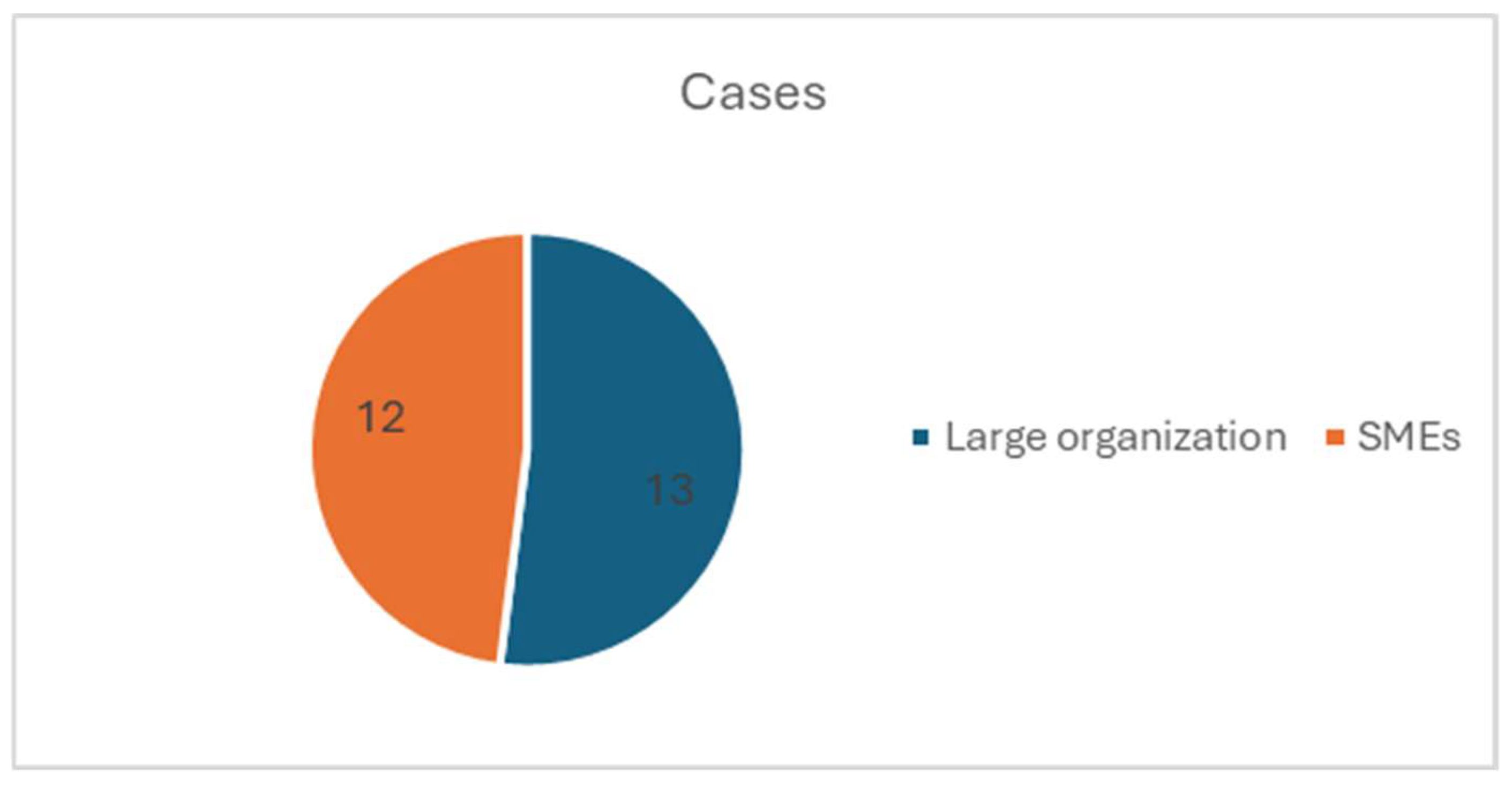

This study aims to identify, categorize, and structure all types of barriers to the process of implementing Open Innovation (OI) in the Asian region. The literature review method was used to answer two main research questions: (RQ1) What are the types and categories of barriers to OI implementation in countries in the Asian region? And (RQ2) What are the most dominant categories of barriers to OI implementation in the Asian region? The process of identifying and selecting journal articles in this literature study used the Google Scholar (GS) publication database. The selected papers have all been published in international journals between 2009 and 2023. This study has succeeded in identifying types of barriers to implementing OI in Asian countries and has divided these barriers into five categories, namely: external, inter-organizational, intra-organizational, organizational, and individual barriers. Analysis of the results of this study shows that the dominant categories of barriers to implementing OI in Asian countries are individual and organizational barriers. Therefore, it can be said that the challenges to implementing OI in Asia are posed more by internal barriers than external ones and the internal barriers that are very influential are the limitations of individual companies and very limited organizational management. The results of this research are expected to provide practical input for various parties, especially in terms of efforts to broaden and deepen the understanding of various barriers to the OI implementation process in a more systematic and comprehensive manner, especially company managers so that they can prepare steps in anticipation of adopting the OI approach in the Asian region.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Open Innovation (OI)

2.2. Barrier to Open Innovation

3. Method

| Categories of Barriers | Description | Source |

| Individual | Barriers that originate from each individual both from within and outside the company, such as knowledge and skills, mental attitude, creativity, and individual perception | Hsu et al. [54]; Chaudhary et al. [11] |

| Intra-organizational | Barriers that originate from parts of the company, such as departments, divisions, teams, and companies’ internal work groups | Smith [24]; Chaudhary et al. [11] |

| Organization | Barriers that originate from unique conditions and organizational characteristics, such as culture and innovation policies that are different in each company | Smith [24] |

| Inter-organizational | Barriers that originate from inter-organizational collaboration processes, such as collaboration with customers, suppliers, and universities | Smith [24]; Chaudhary et al. [11] |

| External | Barriers that originate from outside the company organization, such as the industrial sector, the role of government, community groups, and the innovation system. | Smith [24] |

4. Results & Discussion

| No | Journal | Number |

| 1 | Sustainability | 3 |

| 2 | Global Business Review | 2 |

| 3 | Journal of Open Innovation | 2 |

| 4 | Journal of Management & Organization | 1 |

| 5 | Journal of Technology Management & Innovation | 1 |

| 6 | Asian Economic Papers | 1 |

| 7 | International Journal Management and Enterprise Development | 1 |

| 8 | Quality & Quantity | 1 |

| 9 | Industrial Management & Data System | 1 |

| 10 | International Journal of Policy Studies | 1 |

| 11 | International Journal of Innovation Management | 1 |

| 12 | SSRN | 1 |

| 13 | Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business | 1 |

| 14 | Europian Journal of Innovation Management | 1 |

| 15 | Technological Forecasting & Social Change | 1 |

| 16 | The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge, and Society | 1 |

| 17 | International Journal of Technology | 1 |

| 18 | European Journal of Family Business | 1 |

| 19 | Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management | 1 |

4.1. Future Challanges

4.2. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in the Implementation of Open Innovation

4.3. Broker Roles in OI Implementation

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Research Limitations

References

- Bertello, A.; De Bernardi, P.; Ricciardi, F. Open Innovation: Status Quo and Quo Vadis - an Analysis of a Research Field. Review of Managerial Science 2024, 18, 633–683. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Jianjun, Z.; Hayat, K.; Palmucci, D.N.; Durana, P. Exploring the Factors for Open Innovation in Post-COVID-19 Conditions by Fuzzy Delphi-ISM-MICMAC Approach. European Journal of Innovation Management 2024, 27, 1679–1703. [CrossRef]

- Igartua, J.I.; Garrigós, J.A.; Hervas-Oliver, J.L. How Innovation Management Techniques Support an Open Innovation Strategy. Research Technology Management 2010, 53, 41–52. [CrossRef]

- 2022; 4. The Economic Group The Open Innovation Barometer The Open Innovation Barometer 2; 2022.

- Zhang, X.; Chu, Z.; Ren, L.; Xing, J. Open Innovation and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Role of Organizational Learning. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2023, 186. [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W.; Appleyard, M.M. Open Innovation and Strategy; 2007; Vol. 50.

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Review: Boston, 2003.

- Kovacs, A.; Looy, B. Van; Cassiman, B. Exploring the Scope of Open Innovation: A Bibliometric Review of a Decade of Research Exploring the Scope of Open Innovation: A Bibliometric Review of a Decade of Research 1; 2015.

- de Oliveira, L.S.; Echeveste, M.E.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Critical Success Factors for Open Innovation Implementation. Journal of Organizational Change Management 2018, 31, 1283–1294. [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.; Strazzullo, S.; Cricelli, L.; Grimaldi, M.; Mignacca, B. The Fine Line between Success and Failure: An Analysis of Open Innovation Projects. European Journal of Innovation Management 2022, 25, 687–715. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Kaur, P.; Talwar, S.; Islam, N.; Dhir, A. Way off the Mark? Open Innovation Failures: Decoding What Really Matters to Chart the Future Course of Action. J Bus Res 2022, 142, 1010–1025. [CrossRef]

- de Faria, P.; Noseleit, F.; Los, B. The Influence of Internal Barriers on Open Innovation. Ind Innov 2020, 27, 205–209. [CrossRef]

- Saguy, I.S. Food SMEs’ Open Innovation: Opportunities and Challenges. Innovation Strategies in the Food Industry: Tools for Implementation, Second Edition 2022, 39–52. [CrossRef]

- Malek, J.; Desai, T.N. Prioritization of Sustainable Manufacturing Barriers Using Best Worst Method. J Clean Prod 2019, 226, 589–600. [CrossRef]

- Cricelli, L.; Mauriello, R.; Strazzullo, S. Preventing Open Innovation Failures: A Managerial Framework. Technovation 2023, 127. [CrossRef]

- Oumlil, R.; Juiz, C.; Zohr, I. An Up-to-Date Survey in Barriers to Open Innovation; 2016; Vol. 11.

- Ullah, S.; Ahmad, T.; Kukreti, M.; Sami, A.; Shaukat, M.R. How Organizational Readiness for Green Innovation, Green Innovation Performance and Knowledge Integration Affects Sustainability Performance of Exporting Firms. Journal of Asia Business Studies 2023, 18, 519–537. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Barua, M.K. Evaluation of Manufacturing Organizations Ability to Overcome Internal Barriers to Green Innovations. In; 2021; pp. 139–160.

- Ashraf, M.; Ashraf, S.; Ahmed, S.; Ullah, A. Challenges of Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic Encountered by Students in Pakistan. Journal of Pedagogical Sociology and Psychology 2021, 3, 36–44. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Wang, Z.; Bashir, S.; Khan, A.R.; Riaz, M.; Syed, N. Nexus between IT Capability and Green Intellectual Capital on Sustainable Businesses: Evidence from Emerging Economies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 27825–27843. [CrossRef]

- Novillo-Villegas, S.; Ayala-Andrade, R.; Lopez-Cox, J.P.; Salazar-Oyaneder, J.; Acosta-Vargas, P. A Roadmap for Innovation Capacity in Developing Countries. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Tekic, A.; Willoughby, K.W. Configuring Intellectual Property Management Strategies in Co-Creation: A Contextual Perspective. Innovation: Organization and Management 2020, 22, 128–159. [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Ye, H.; Teo, H.H.; Li, J. Information Technology and Open Innovation: A Strategic Alignment Perspective. Information & Management 2015, 52, 348–358. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. Public Sector Open Innovation Exploring Barriers and How Intermediaries Can Mitigate Them; 2018.

- Business and Management in Asia: Digital Innovation and Sustainability; Endress, T., Badir, Y.F., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; ISBN 978-981-19-6417-6.

- Smith, R.; Perry, M. Is an “Open Innovation” Policy Viable in Southeast Asia? - A Legal Perspective. Athens Journal of Law 2023, 9, 187–210. [CrossRef]

- Dubouloz, S.; Bocquet, R.; Balzli, C.E.; Gardet, E.; Gandia, R.; Smes’, R.G. Open Innovation: Applying a Barrier Approach. Calif Manage Rev 2021, 64, 113–137. [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.H.J.; Zhao, X.; Jung, K.H.; Yigitcanlar, T. The Culture for Open Innovation Dynamics. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Radziwon, A.; Chesbrough, H.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; West, J. The Future of Open Innovation. In The Oxford Handbook of Open Innovation; Oxford University Press, 2024; pp. 914–934.

- Audretsch, B.D.; Belitski, M. The Limits to Open Innovation and Its Impact on Innovation Performance. Technovation 2023, 119. [CrossRef]

- Rouyre, A.; Fernandez, A.-S. Managing Knowledge Sharing-Protecting Tensions in Coupled Innovation Projects among Several Competitors. Calif Manage Rev 2019, 62, 95–120. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A.; Troise, C.; Strazzullo, S.; Bresciani, S. Creating Shared Value through Open Innovation Approaches: Opportunities and Challenges for Corporate Sustainability. Bus Strategy Environ 2023, 32, 4485–4502. [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation Results; Oxford University PressOxford, 2019; ISBN 0198841906.

- Terhorst, A.; Wang, P.; Lusher, D.; Bolton, D.; Elsum, I. Broker Roles in Open Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, O.; Enkel, E. Towards a Theory of Open Innovation: Three Core Process Archetypes; 2004.

- Greco, M.; Grimaldi, M.; Cricelli, L. Benefits and Costs of Open Innovation: The BeCO Framework. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 2019, 31, 53–66. [CrossRef]

- Moya, J.B. Open Innovation Practices in Colombian SMEs: Current State, Barriers, and Pathways to Success KTH Royal Institute of Technology Industrial Engineering and Management Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management; 2023.

- Albats, E.; Podmetina, D.; Vanhaverbeke, W. Open Innovation in SMEs: A Process View towards Business Model Innovation. Journal of Small Business Management 2023, 61, 2519–2560. [CrossRef]

- Hashimy, L.; Treiblmaier, H.; Jain, G. Distributed Ledger Technology as a Catalyst for Open Innovation Adoption among Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Journal of High Technology Management Research 2021, 32. [CrossRef]

- Sugandini, D.; Ghofar, A.; SDA Ambarwati, SDA.; Arundati, R. Limitations of Application Open Innovation for Increasing the Performance of Craft SMEs in Sleman, Indonesia. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research 2024, 13.

- Pihlajamaa, M. What Does It Mean to Be Open? A Typology of Inbound Open Innovation Strategies and Their Dynamic Capability Requirements. Innovation: Organization and Management 2023, 25, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; Eikelenboom, M.; Long, T.B. Innovating for Sustainability through Collaborative Innovation Contests. J Clean Prod 2021, 311. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation as a Response to Constraints and Risks: Evidence from China. Asian Economic Papers 2014, 13, 30–58. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ahmad, N.; Khan, F.U.; Badulescu, A.; Badulescu, D. Mapping Interactions among Green Innovations Barriers in Manufacturing Industry Using Hybrid Methodology: Insights from a Developing Country. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Brunswicker, S.; Chesbrough, H. The Adoption of Open Innovation in Large Firms: Practices, Measures, and RisksA Survey of Large Firms Examines How Firms Approach Open Innovation Strategically and Manage Knowledge Flows at the Project Level. Research Technology Management 2018, 61, 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xiao, Z.; Dong, M.C.; Gu, J. The Fit between Firms’ Open Innovation and Business Model for New Product Development Speed: A Contingent Perspective. Technovation 2019, 86–87, 75–85. [CrossRef]

- Himanshu Gupta; Mukesh Kumar Barua Evaluation of Manufacturing Organizations Ability to Overcome Internal Barriers to Green Innovations. Indian Institutes of Technology 2021, 139–160.

- Hewitt-Dundas, N.; Roper, S. Exploring Market Failures in Open Innovation. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 2018, 36, 23–40. [CrossRef]

- Drewery, D.; Judene, T.; Dana Church, P. Contributions of Work-Integrated Learning Programs to Organizational Talent Pipelines: Insights from Talent Managers; 2020.

- Dahlander, L.; Gann, D.M.; Wallin, M.W. How Open Is Innovation? A Retrospective and Ideas Forward. Res Policy 2021, 50. [CrossRef]

- Mody, M.A.; Lu, L.; Hanks, L. “It’s Not Worth the Effort”! Examining Service Recovery in Airbnb and Other Homesharing Platforms. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2020, 32, 2991–3014. [CrossRef]

- Hartono, A. Do Innovation Barriers Drive a Firm to Adopt Open Innovation? Indonesian Firms’ Experiences; 2018; Vol. 17.

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Who Captures Value from Open Innovation — The Firm or Its Employees? Strategic Management Review 2020, 1, 255–276. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-F.; Nguyen, T.K.; Huang, J.-Y. Value Co-Creation and Co-Destruction in Self-Service Technology: A Customer’s Perspective. Electron Commer Res Appl 2021, 46, 101029. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chang, H.; Forrest, J.Y.L.; Yang, B. Influence of Artificial Intelligence on Technological Innovation: Evidence from the Panel Data of China’s Manufacturing Sectors. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2020, 158. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, B.A. Open Innovation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Executive and Employee Perception of Processes and Receptiveness; 2018.

- Bogers, M.; Chesbrough, H.; Moedas, C. Open Innovation: Research, Practices, and Policies. Calif Manage Rev 2018, 60, 5–16. [CrossRef]

- Gurca, A.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Markovic, S.; Koporcic, N. Managing the Challenges of Business-to-Business Open Innovation in Complex Projects: A Multi-Stage Process Model. Industrial Marketing Management 2021, 94, 202–215. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Thelwall, M.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Delgado López-Cózar, E. Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, and OpenCitations’ COCI: A Multidisciplinary Comparison of Coverage via Citations. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 871–906. [CrossRef]

- Setiani Rafika, A.; Yunan Putri, H.; Diah Widiarti, F.; STMIK Raharja Tangerang, D.; STMIK Raharja Tangerang, M.; Jendral Sudirman No, J. ANALISIS MESIN PENCARIAN GOOGLE SCHOLAR SEBAGAI SUMBER BARU UNTUK KUTIPAN. 2017, 3.

- Li, D.; Hou, R. Impact of Inbound Open Innovation on Chinese Advanced Manufacturing Enterprise Performance. International Journal of Knowledge Management 2023, 19. [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Wang, D. Will Increasing Government Subsidies Promote Open Innovation? A Simulation Analysis of China’s Wind Power Industry. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mitkova, L. Research on China’s Knowledge-Sharing System: Under Open Innovation Framework; 2016; Vol. 15.

- Savitskaya, I.; Salmi, P.; Torkkeli, M. Barriers to Open Innovation: Case China; 2010; Vol. 5.

- Huang, F.; Rice, J.; Martin, N. Does Open Innovation Apply to China? Exploring the Contingent Role of External Knowledge Sources and Internal Absorptive Capacity in Chinese Large Firms and SMEs. Journal of Management and Organization 2015, 21, 594–613. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, R.T.; Gentile-Lüdecke, S.; Figueira, S. Barriers to Innovation and Innovation Performance: The Mediating Role of External Knowledge Search in Emerging Economies. Small Business Economics 2022, 58, 1953–1974. [CrossRef]

- Naqshbandi, M.M.; Kaur, S. Do Managerial Ties Support or Stifle Open Innovation? Industrial Management and Data Systems 2014, 114, 652–675. [CrossRef]

- Naqshbandi, M.M.; Kaur, S.; Ma, P. What Organizational Culture Types Enable and Retard Open Innovation? Qual Quant 2015, 49, 2123–2144. [CrossRef]

- Annamalah, S.; Aravindan, K.L.; Raman, M.; Paraman, P. SME Engagement with Open Innovation: Commitments and Challenges towards Collaborative Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Naqshbandi, M.M. Organizational Characteristics and Engagement in Open Innovation: Is There a Link? Global Business Review 2018, 19, S1–S20. [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Andrew, S. Building R&D Collaboration between University-Research Institutes and Small Medium-Sized Enterprises. Int J Soc Econ 2014, 41, 1174–1193. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Lee, K.; Yoon, B. Development Of An Open Innovation Model For R&D Collaboration Between Large Firms And Small-Medium Enterprises (Smes) In Manufacturing INDUSTRIES. International Journal of Innovation Management 2017, 21. [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-H.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y. Compassion and Workplace Incivility: Implications for Open Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2021, 7, 95. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.M.; Mortara, L.; Minshall, T. Linkages between Openness and CEO Characteristics in Innovative SMEs. SSRN Electronic Journal 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.M.; Ali, A.; Saleem, H.; Qamruzzaman, M.; Khalid, R. The Effect of Technology and Open Innovation on Women-Owned Small and Medium Enterprises in Pakistan. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 2021, 8, 411–422. [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, N.; Adomako, S. Be Open to Failure: Open Innovation Failure in Dynamic Environments. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2023, 193. [CrossRef]

- Lingyan, M.; Qamruzzaman, M.; Adow, A.H.E. Technological Adaption and Open Innovation in Smes: An Strategic Assessment for Women-Owned Smes Sustainability in Bangladesh. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Hartono, A.; Kusumawardhani, R. Innovation Barriers and Their Impact on Innovation: Evidence from Indonesian Manufacturing Firms. Global Business Review 2019, 20, 1196–1213. [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.; Lam, K. Open Innovation: A Study of Industry-University Collaboration in Environmental R&D in Hong Kong. Hong Kong The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge, and Society 2012, 8.

- Naruetharadhol, P.; Srisathan, W.A.; Gebsombut, N.; Wongthahan, P.; Ketkaew, C. Industry 4.0 for Thai SMEs: Implementing Open Innovation as Innovation Capability Management. International Journal of Technology 2022, 13, 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; Kong, E.; Timperio, G. An Analysis of Open Innovation Determinants: The Case Study of Singapore Based Family Owned Enterprises. European Journal of Family Business 2019, 9, 85–101. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.; Chong, C.W.; Ojo, A.O. The Implications of Knowledge-Based HRM Practices on Open Innovations for SMEs in the Manufacturing Sector. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management 2023, 18, 521–545. [CrossRef]

- Stefan, I.; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Oikarinen, E.L. The Dark Side of Open Innovation: Individual Affective Responses as Hidden Tolls of the Paradox of Openness. J Bus Res 2022, 138, 360–373. [CrossRef]

- Bilichenko, O.; Tolmachev, M.; Polozova, T.; Aniskevych, D.; Mohammad, A.L.A.K. Managing Strategic Changes in Personnel Resistance to Open Innovation in Companies. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Marzi, G.; Fakhar Manesh, M.; Caputo, A.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Vlačić, B. Do or Do Not. Cognitive Configurations Affecting Open Innovation Adoption in SMEs. Technovation 2023, 119. [CrossRef]

- Faridian, P.H. Leading Open Innovation: The Role of Strategic Entrepreneurial Leadership in Orchestration of Value Creation and Capture in GitHub Open Source Communities. Technovation 2023, 119. [CrossRef]

- David, K.G.; Yang, W.; Pei, C.; Moosa, A. Effect of Transformational Leadership on Open Innovation through Innovation Culture: Exploring the Moderating Role of Absorptive Capacity. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 2021, 35, 613–628. [CrossRef]

- Lianto, B.; Dachyar, M.; Soemardi, T.P. Modelling the Continuous Innovation Capability Enablers in Indonesia’s Manufacturing Industry. Journal of Modelling in Management 2020, 17, 66–99. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Hooi, L.W.; Avvari, M.V. Leadership Styles and Organisational Innovation in Vietnam: Does Employee Creativity Matter? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2023, 72, 331–360. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yue, Z.; Ijaz, A.; Lutfi, A.; Mao, J. Sustainable Business Performance: Examining the Role of Green HRM Practices, Green Innovation and Responsible Leadership through the Lens of Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Al Nuaimi, F.M.S.; Singh, S.K.; Ahmad, S.Z. Open Innovation in SMEs: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Journal of Knowledge Management 2024, 28, 484–504. [CrossRef]

- Lianto, B. Identifying Key Assessment Factors for a Company’s Innovation Capability Based on Intellectual Capital: An Application of the Fuzzy Delphi Method. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Khan, F.U.; Ahmad, N. Promoting Sustainability through Green Innovation Adoption: A Case of Manufacturing Industry. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 21119–21139. [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, A.M.; Mackiewicz, M. Commonalities and Differences of Cluster Policy of Asian Countries; Discussion on Cluster Open Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2021, 7, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Sira, M.; Brożek, P. Use of Artificial Intelligence in Terms of Open Innovation Process and Management. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Machado, I.; Magrelli, V.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Artificial Intelligence in Innovation Research: A Systematic Review, Conceptual Framework, and Future Research Directions. Technovation 2023, 122. [CrossRef]

- Bahoo, S.; Cucculelli, M.; Qamar, D. Artificial Intelligence and Corporate Innovation: A Review and Research Agenda. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2023, 188. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zeng, J. Shaping AI’s Future? China in Global AI Governance. Journal of Contemporary China 2023, 32, 794–810. [CrossRef]

- Heeu, K.G.; Kim, M.; Deng, M. Issue Brief Examining Singapore’s AI Progress; 2023.

- Baldwin, R.; Okubo, T. Are Software Automation and Teleworker Substitutes? Preliminary Evidence from Japan. World Economy 2024, 47, 1531–1556. [CrossRef]

- Widayanti, R.; Meria, L. Business Modeling Innovation Using Artificial Intelligence Technology; 2023; Vol. 1.

- Yun, J.H.J.; Won, D.K.; Jeong, E.S.; Park, K.B.; Yang, J.H.; Park, J.Y. The Relationship between Technology, Business Model, and Market in Autonomous Car and Intelligent Robot Industries. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2016, 103, 142–155. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Hamid, R.; Sultan, B.; Ahmad, F.; Hamid, R.; Ahmad, F.; Jinnah, F. Strategic Sustainability: Exploring the Impact of Technological Inclusion of AI in Pakistani Health Care Strategic Sustainability: Exploring the Impact of Technological Inclusion of AI in Pakistani Health Care The Commission on Science and Technology for Sustainable Development in the South (COMSATS) Islamabad. Journal of Workplace Behavior (JWB) 2023, 4, 2023.

- Hopkins, J.L. An Investigation into Emerging Industry 4.0 Technologies as Drivers of Supply Chain Innovation in Australia. Comput Ind 2021, 125. [CrossRef]

- Broekhuizen, T.; Dekker, H.; de Faria, P.; Firk, S.; Nguyen, D.K.; Sofka, W. AI for Managing Open Innovation: Opportunities, Challenges, and a Research Agenda. J Bus Res 2023, 167. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Mo Ahn, J.; Min Lee, K. The Impacts of Cross Functional Team on Innovation Performance and Openness; 2018.

- Paschen, U.; Pitt, C.; Kietzmann, J. Artificial Intelligence: Building Blocks and an Innovation Typology. Bus Horiz 2020, 63, 147–155. [CrossRef]

- Lou, B.; Wu, L. AI on Drugs: Can Artificial Intelligence Accelerate Drug Development? Evidence from a Large-Scale Examination of Bio-Pharma Firms.

- Barbosa, A.P.P.L.; Salerno, M.S.; Brasil, V.C.; Nascimento, P.T. de S. Coordination Approaches to Foster Open Innovation R&D Projects Performance. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 2020, 58, 101603. [CrossRef]

- Saputra, R.; Tiolince, T.; Iswantoro; Sigh, S.K. Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property Protection in Indonesia and Japan. Journal of Human Rights, Culture and Legal System 2023, 3, 210–235. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kogler, D.F.; Zabetta, M.C. New Collaborations and Novel Innovations: The Role of Regional Brokerage and Collaboration Intensity. European Planning Studies 2023, 32, 1251–1272. [CrossRef]

- Corvello, V.; Felicetti, A.M.; Steiber, A.; Alänge, S. Start-up Collaboration Units as Knowledge Brokers in Corporate Innovation Ecosystems: A Study in the Automotive Industry. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Peng, L.; Shang, Y.; Zhao, X. Green Technology Progress and Total Factor Productivity of Resource-Based Enterprises: A Perspective of Technical Compensation of Environmental Regulation. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2022, 174, 121276. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.P. de The Impact of Food Manufacturing Practices on Food Borne Diseases. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology 2008, 51, 615–623. [CrossRef]

- Ankrah, S.; AL-Tabbaa, O. Universities-Industry Collaboration: A Systematic Review. Scandinavian Journal of Management 2015, 31, 387–408. [CrossRef]

| No | Inclusion Criteria |

Description | Result Searching Date: 25 April 2024 |

| 1 | Databases | Google Scholar (GS) publication database | Initial papers: 536 |

| 2 | Keywords | “Barriers to open innovation” OR “constraints to open innovation” OR “inhibitors to open innovation” OR “lack of open innovation” OR “obstacles to open innovation” | |

| 3 | Period | 2009–2023 | |

| 4 | Language | Papers written in English | |

| No | Exclusion Criteria |

Description | Result |

| 1 | EC 1 | Papers with unchecked citations. | 530 |

| 2 | EC 2 | Papers that did not include empirical research and did not have an explicit mention of research locations in Asian countries in the title and abstract of the article | 34 |

| 3 | EC3 | Papers that did not contain and discuss OI and obstacles to its implementation | 23 |

| No | Category of Barriers | Sources | |||||

| Countries | Individual | External | Intra-Organization | Inter- Organization |

Organization | ||

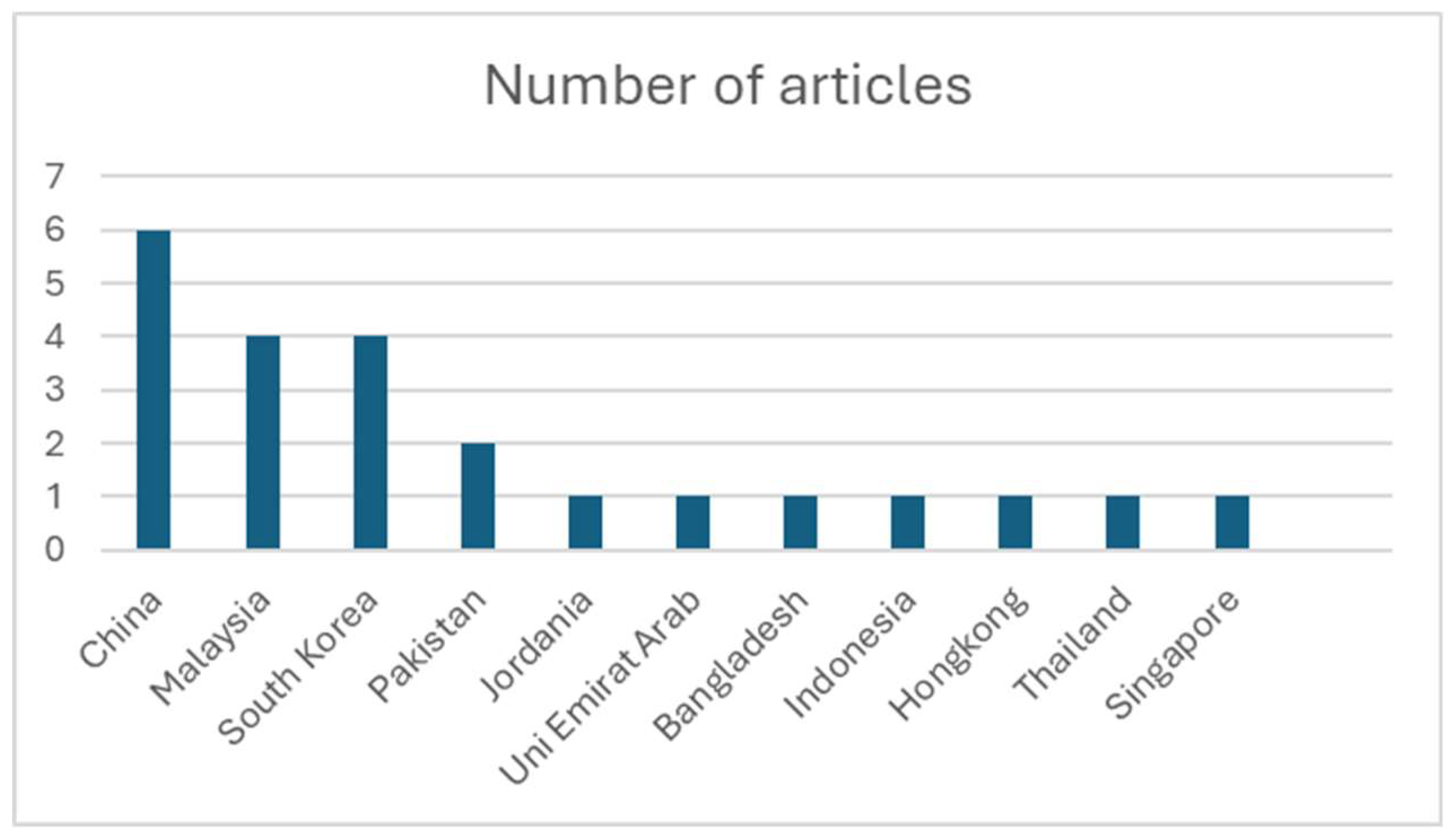

| 1 | China | Weak research expertise; knowledge & skill; Lack of qualified personnel | Economic system and institution; Financial system | Lack of cooperation inside the company | Trust; Network | Absorption capacity; Technological value; Culture restriction; Lack of technical support; Lack of incentive mechanism; Entrepreneurial orientation; Financial support | Gao and Wang [62]; Wang and Mitkova [63]; Savitskaya et al. [64]; Huang et al. [65]; Oliveira et al. [66] |

| 2 | Malaysia | Motivation; Mindset; Employee behavior | Managerial Ties; Transactional cost; Inter-organization ties | Organizational culture; Firm characteristics | Naqshbandi and Kaur [67]; Naqshbandi et al. [68]; Annamalah et al. [69]; Naqshbandi [70] | ||

| 3 | South Korea | Employee compassion; Innovative behavior; Positive leadership; CEO traits and attitudes | Open Innovation System; Government initiative and support | Information sharing; Workplace incivility | Trust; Sustainable relation | R&D capabilities; Management support | Jung and Andrew [71]; Jang et al. [72]; Ko et al. [73]; Ahn et al. [74] |

| 4 | Pakistan | Employee competence and commitment; Executive commitments | Organizational culture; Lack of innovation strategy | Mehta et al. [75]; Ullah et al. [17] | |||

| 5 | United Arab Emirates | Relational trust | Organizational learning culture | Zahoor and Adomako [76] | |||

| 6 | Bangladesh | Competence and commitment of worker | Organization culture | Meng et al. [77] | |||

| 7 | Indonesia | Employee attitudes | Organization attitude | Hartono and Kusumawardhani [78] | |||

| 8 | Hong Kong | Innovation policy | Institutional mechanisms | Chi and Lam [79] | |||

| 9 | Thailand | Competence and commitment | Knowledge management | Networks | Centralized structure | Naruetharadhol et al. [80] | |

| 10 | Singapore | Government support; Market dynamics; Access to external funds | External network and partnership | Culture | Koh et al. [81] | ||

| 11 | Jordan | Collaborative and learning skill | Training and development system | Shahin et al. [82] | |||

| Categories | Barriers to Open Innovation | Countries |

| Individual | Weak research expertise; knowledge & skill; lack of qualified personnel; motivation; mindset; employee behavior; employee compassion; innovative behavior; positive leadership; CEO traits and attituides; employee competence and commitment; executive commitments; employee attitude; collaborative and learning skill | China, Malaysia, South Korea, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Thailand, and Jordan |

| External | Economic system and institution; financial system; open innovation system; government initiative and support; innovation policy; market dynamics; access to external funds | China, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore |

| Intra-Organization | Lack of cooperation inside the company; information sharing; workplace incivility; knowledge management; managerial ties | China, South Korea, and Thailand |

| Inter-Organization | Transactional cost; inter-organization ties; trust; sustainable relation; institutional mechanisms; external network and partnership | Malaysia, South Korea, United Arab Emirates, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Singapore |

| Organization | Absorption capacity; technological value; culture restriction; lack of technical support; lack of incentive mechanism; entrepreneurial orientation; financial support; organization culture; firm characteristic; R&D capabilities; management support; lack of innovation strategy; organizational learning culture; organization attitude; centralized structure; training and development system | China, Malaysia, South Korea, Pakistan, United Arab Emirates, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, and Jordan |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).