Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

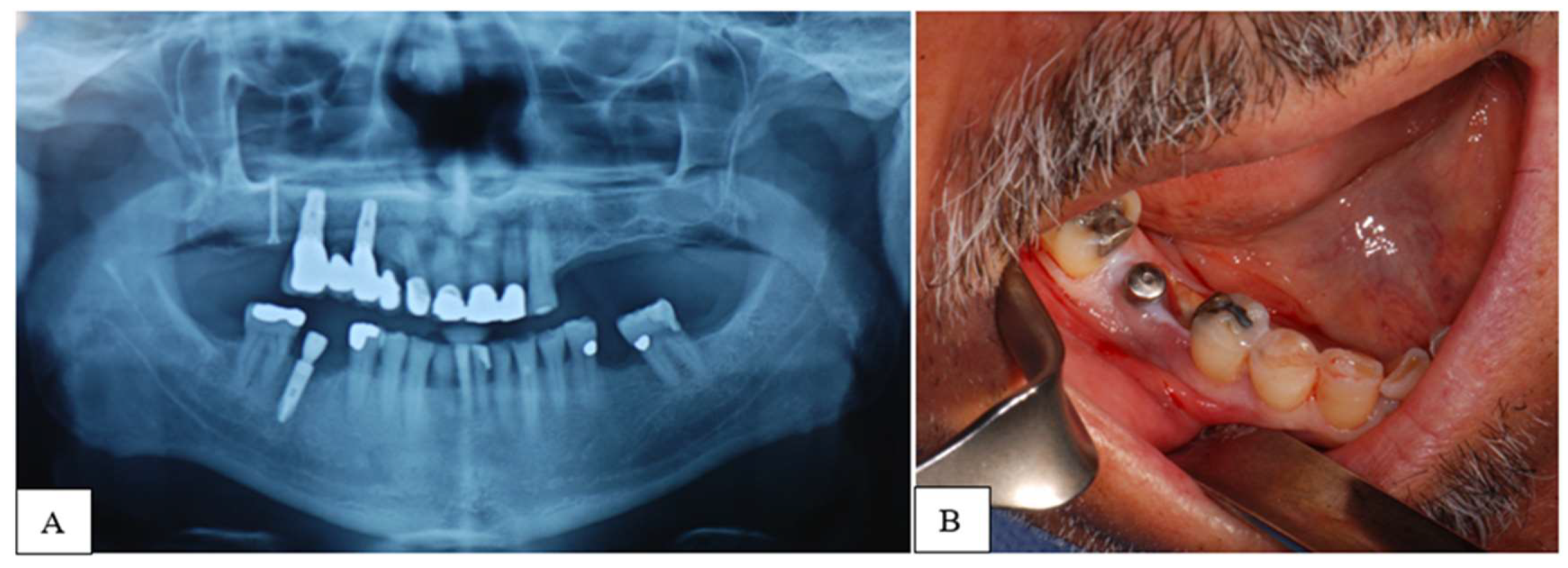

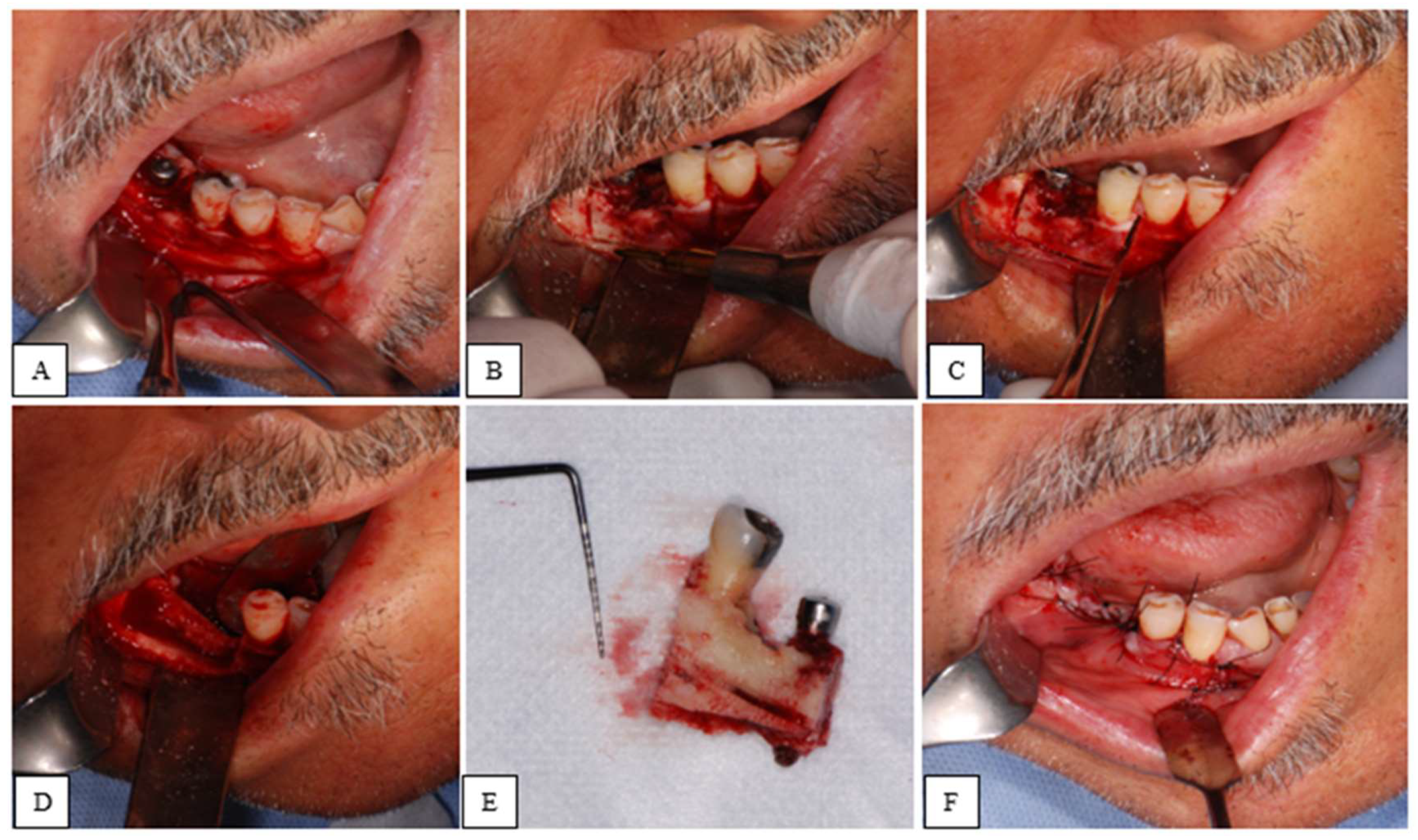

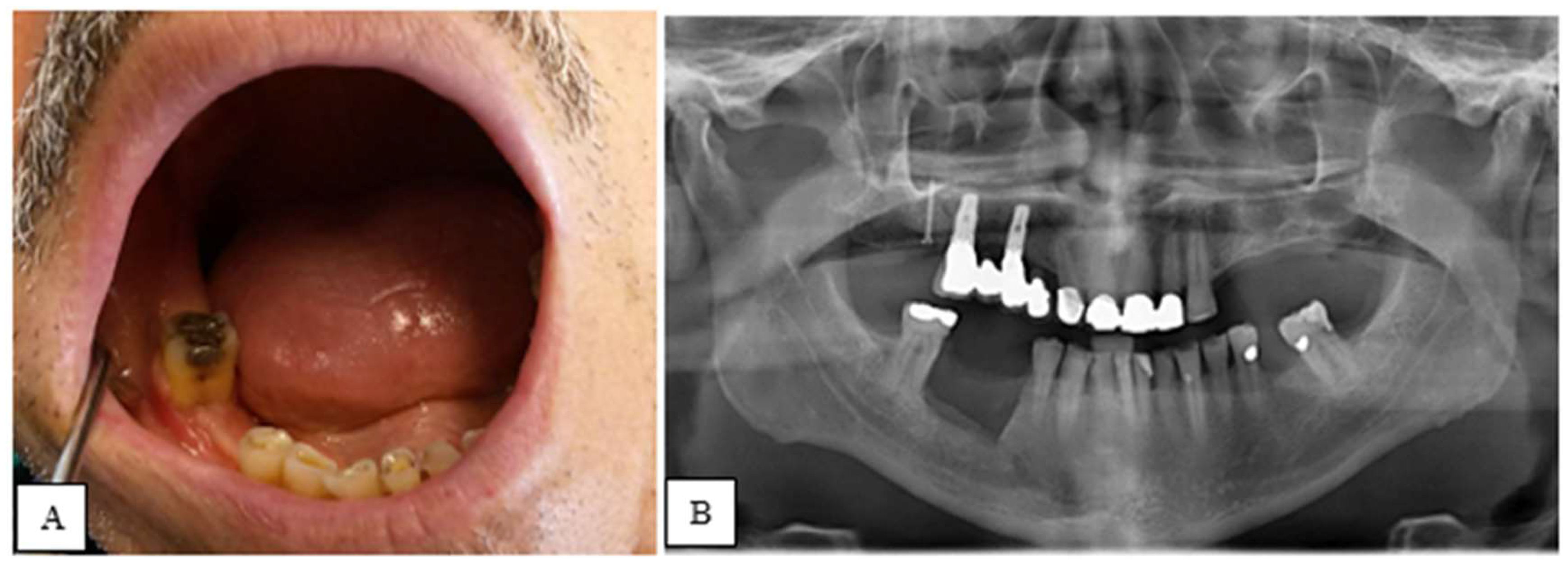

Objective: This study aims to investigate the efficacy of marginal resection using a piezoelectric device in patients with Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (BRONJ). Methods: A retrospective study was conducted on subjects treated at the Dental Clinic University Hospital of Padua (Italy) from January 2017 to April 2024. Patients diagnosed with BRONJ (stages 1 and 2) who underwent marginal resection of the maxillae using a piezoelectric instrument were included. Exclusion criteria included patients who had received radiotherapy to the head and neck, those with Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ), and those with primary tumors of the maxillary bones. Marginal resection was considered an effective treatment when complete epithelialization of the surgical site was achieved, with no signs or symptoms of disease, and the condition remained stable one-year post-operation. Results: 21 patients (17 females and 4 males) were selected. A single resection was performed for each patient, resulting in a total of 21 surgeries: 14 in the mandible and 7 in the maxilla. At one-year post-surgery, 20 patients showed no signs or symptoms of the disease. 1 patient experienced two recurrences, both of which were subsequently treated. Conclusions: The study demonstrates that marginal resection using a piezoelectric device is an effective procedure for the treatment of BRONJ, although it remains a relatively invasive and destructive therapeutic approach.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OPG | Orthopantomography |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ZOL | Zoledronic acid |

| ALE | Alendronate |

| IBA | Ibandronate |

References

- Bedogni, A.; Mauceri, R.; Fusco, V.; Bertoldo, F.; Bettini, G.; Di Fede, O.; Lo Casto, A.; Marchetti, C.; Panzarella, V.; Saia, G.; Vescovi, P.; Campisi, G. (2024). Italian position paper (SIPMO-SICMF) on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). In Oral Diseases (Vol. 30, pp. 3679–3709). John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Sivolella, S.; Brunello, G.; Berengo, M.; de Biagi, M.; Bacci, C. (2015). Rehabilitation With Implants After Bone Lid Surgery in the Posterior Mandible. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 73, 1485–1492. [CrossRef]

- Rullo, R.; Piccirillo, A.; Femiano, F.; Nastri, L.; Festa, V. M. (2018). A Comparison between Piezoelectric Devices and Conventional Rotary Instruments in Bone Harvesting in Patients with Lip and Palate Cleft: A Retrospective Study with Clinical, Radiographical, and Histological Evaluation. BioMed Research International, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Labanca, M.; Azzola, F.; Vinci, R.; Rodella, L. F. (2008). Piezoelectric surgery: Twenty years of use. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 46, 265–269. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Aghaloo T, Carlson ER, Ward BB, Kademani D. (2020). American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons’ Position Paper on Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws-2022 Update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022 May;80(5):920-943. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. (2013). In JAMA (Vol. 310, pp. 2191–2194). American Medical Association. [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D. G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S. J.; Gøtzsche, P. C.; Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2008). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61, 344–349. [CrossRef]

- Hoff, A. O.; Toth, B. B.; Altundag, K.; Johnson, M. M.; Warneke, C. L.; Hu, M.; Nooka, A.; Sayegh, G.; Guarneri, V.; Desrouleaux, K.; Cui, J.; Adamus, A.; Gagel, R. F.; Hortobagyi, G. N. (2008). Frequency and risk factors associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients treated with intravenous bisphosphonates. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 23, 826–836. [CrossRef]

- Estilo, C. L.; van Poznak, C. H.; Wiliams, T.; Bohle, G. C.; Lwin, P. T.; Zhou, Q.; Riedel, E. R.; Carlson, D. L.; Schoder, H.; Farooki, A.; Fornier, M.; Halpern, J. L.; Tunick, S. J.; Huryn, J. M. (2008). Osteonecrosis of the Maxilla and Mandible in Patients with Advanced Cancer Treated with Bisphosphonate Therapy. The Oncologist, 13, 911–920. [CrossRef]

- Eckert, A. W.; Maurer, P.; Meyer, L.; Kriwalsky, M. S.; Rohrberg, R.; Schneider, D.; Bilkenroth, U.; Schubert, J. (2007). Bisphosphonate-related jaw necrosis - Severe complication in Maxillofacial surgery. In Cancer Treatment Reviews (Vol. 33, pp. 58–63). [CrossRef]

- Thumbigere-Math, V.; Tu, L.; Huckabay, S.; Dudek, A. Z.; Lunos, S.; Basi, D. L.; Hughes, P. J.; Leach, J. W.; Swenson, K. K.; Gopalakrishnan, R. (2012). A retrospective study evaluating frequency and risk factors of osteonecrosis of the jaw in 576 cancer patients receiving intravenous bisphosphonates. American Journal of Clinical Oncology: Cancer Clinical Trials, 35, 386–392. [CrossRef]

- O’Ryan, F. S.; Lo, J. C. (2012). Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with oral bisphosphonate exposure: Clinical course and outcomes. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 70, 1844–1853. [CrossRef]

- Fliefel, R.; Tröltzsch, M.; Kühnisch, J.; Ehrenfeld, M.; Otto, S. (2015). Treatment strategies and outcomes of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) with characterization of patients: A systematic review. In International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (Vol. 44, pp. 568–585). Churchill Livingstone. [CrossRef]

- Atalay, B.; Yalcin, S.; Emes, Y.; Aktas, I.; Aybar, B.; Issever, H.; Mandel, N. M.; Cetin, O.; Oncu, B. (2011). Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis: Laser-assisted surgical treatment or conventional surgery? Lasers in Medical Science, 26, 815–823. [CrossRef]

- Vescovi, P.; Manfredi, M.; Merigo, E.; Meleti, M.; Guidotti, R.; Sarraj, A.; Mergoni, G.; Fornaini, C.; Bonanini, M.; Pizzi, S.; Rocca, J. P.; Nammour, S. (2012). Osteonecrosi dei mascellari e bisfosfonati: Terapia e follow-up a lungo termine in 160 pazienti. Dental Cadmos, 80, 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Thumbigere-Math, V.; Michalowicz, B. S.; Hodges, J. S.; Tsai, M. L.; Swenson, K. K.; Rockwell, L.; Gopalakrishnan, R. (2014). Periodontal Disease as a Risk Factor for Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. Journal of Periodontology, 85, 226–233. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Pouso, A. I.; Pérez-Sayáns, M.; Chamorro-Petronacci, C.; Gándara-Vila, P.; López-Jornet, P.; Carballo, J.; García-García, A. (2020). Association between periodontitis and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review and meta-analysis. In Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine (Vol. 49, pp. 190–200). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Dioguardi, M.; di Cosola, M.; Copelli, C.; Cantore, S.; Quarta, C.; Nitsch, G.; Sovereto, D.; Spirito, F.; Caloro, G. A.; Cazzolla, A. P.; Aiuto, R.; Cascardi, E.; Greco Lucchina, A.; lo Muzio, L.; Ballini, A.; Mastrangelo, F. (2023). Oral bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis complications in patients undergoing tooth extraction: a systematic review and literature updates. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 27, 6359–6373. [CrossRef]

- Nisi, M.; la Ferla, F.; Karapetsa, D.; Gennai, S.; Miccoli, M.; Baggiani, A.; Graziani, F.; Gabriele, M. (2015). Risk factors influencing BRONJ staging in patients receiving intravenous bisphosphonates: A multivariate analysis. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 44, 586–591. [CrossRef]

- Bodem, J. P.; Kargus, S.; Eckstein, S.; Saure, D.; Engel, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Freudlsperger, C. (2015). Incidence of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in high-risk patients undergoing surgical tooth extraction. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery, 43, 510–514. [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, D.; Seemann, R.; Matoni, N.; Ewers, R.; Millesi, W.; Wutzl, A. (2014). Effect of dental implants on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 72, 1937.e1-1937.e8. [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.; Laviv, A.; Schwartz-Arad, D. (2007). Denture-related osteonecrosis of the maxilla associated with oral bisphosphonate treatment. Journal of the American Dental Association, 138, 1218–1220. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, Y.; Kawabe, M.; Kimura, H.; Kurita, K.; Fukuta, J.; Urade, M. (2012). Influence of dentures in the initial occurrence site on the prognosis of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: A retrospective study. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology, 114, 318–324. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-L.; Xiang, Z.-J.; Yang, J.-H.; Wang, W.-J.; Xiang, R.-L. (2019). The incidence and relative risk of adverse events in patients treated with bisphosphonate therapy for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology, 11, 1758835919855235. [CrossRef]

- Fung, P.L.; Nicoletti, P.; Shen, Y.; Porter, S.; Fedele S (2015) Pharmacogenetics of Bisphosphonate-associated Osteonecrosis of the Jaw In Oral Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America (Vol, 2.7.; pp 537–546), W.B.Fung, P. L.; Nicoletti, P.; Shen, Y.; Porter, S.; Fedele, S. (2015). Pharmacogenetics of Bisphosphonate-associated Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. In Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America (Vol. 27, pp. 537–546). W.B. Saunders. [CrossRef]

- Apatzidou, D. A. (2022). The role of cigarette smoking in periodontal disease and treatment outcomes of dental implant therapy. In Periodontology 2000 (Vol. 90, pp. 45–61). John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- Chambler, D.; Blincoe, T. (2018). Smoking and surgery. British Journal of Hospital Medicine (London, England: 2005), 79, 478. [CrossRef]

- Bacci, C.; Boccuto, M.; Cerrato, A.; Grigoletto, A.; Zanette, G.; Angelini, A.; Sbricoli, L. (2021). Safety and efficacy of sectorial resection with piezoelectric device in ONJ. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, J.; Shannon, J.; Modelevsky, S.; Grippo, A. A. (2011). Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 2350–2355. [CrossRef]

- Paek, S. J.; Park, W.-J.; Shin, H.-S.; Choi, M.-G.; Kwon, K.-H.; Choi, E. J. (2016). Diseases having an influence on inhibition of angiogenesis as risk factors of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, 42, 271–277. [CrossRef]

- Molcho, S.; Peer, A.; Berg, T.; Futerman, B.; Khamaisi, M. (2013). Diabetes microvascular disease and the risk for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A single center study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 98. [CrossRef]

- Jarnbring, F.; Kashani, A.; Björk, A.; Hoffman, T.; Krawiec, K.; Ljungman, P.; Lund, B. (2015). Role of intravenous dosage regimens of bisphosphonates in relation to other aetiological factors in the development of osteonecrosis of the jaws in patients with myeloma. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 53, 1007–1011. [CrossRef]

- Anavi-Lev, K.; Anavi, Y.; Chaushu, G.; Alon, D. M.; Gal, G.; Kaplan, I. (2013). Bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaws: Clinico-pathological investigation and histomorphometric analysis. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology, 115, 660–666. [CrossRef]

- Tiranathanagul, S.; Yongchaitrakul, T.; Pattamapun, K.; Pavasant, P. (2004). Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans Lipopolysaccharide Activates Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 and Increases Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor-κB Ligand Expression in Human Periodontal Ligament Cells. Journal of Periodontology, 75, 1647–1654. [CrossRef]

- Jelin-Uhlig, S.; Weigel, M.; Ott, B.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Howaldt, H.-P.; Böttger, S.; Hain, T. (2024). Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw and Oral Microbiome: Clinical Risk Factors, Pathophysiology and Treatment Options. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25. [CrossRef]

- Miksad, R. A.; Lai, K.-C.; Dodson, T. B.; Woo, S.-B.; Treister, N. S.; Akinyemi, O.; Bihrle, M.; Maytal, G.; August, M.; Gazelle, G. S.; Swan, J. S. (2011). Quality of Life Implications of Bisphosphonate-Associated Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. The Oncologist, 16, 121–132. [CrossRef]

- Blus, C.; Szmukler-Moncler, S.; Giannelli, G.; Denotti, G.; Orrù, G. (2013). Use of Ultrasonic Bone Surgery (Piezosurgery) to Surgically Treat Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws (BRONJ). A Case Series Report with at Least 1 Year of Follow-Up. The Open Dentistry Journal, 7, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Blus, C.; Giannelli, G.; Szmukler-Moncler, S.; Orru, G. (2017). Treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) with ultrasonic piezoelectric bone surgery. A case series of 20 treated sites. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 21, 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A. M.; Malcangi, G.; Ferrara, I.; Viapiano, F.; Netti, A.; Patano, A.; Isacco, C. G.; Inchingolo, A. D.; Inchingolo, F. (2023). Sixty-Month Follow Up of Clinical MRONJ Cases Treated with CGF and Piezosurgery. Bioengineering (Basel, Switzerland), 10. [CrossRef]

- Bacci, C.; Cerrato, A.; Bardhi, E.; Frigo, A. C.; Djaballah, S. A.; Sivolella, S. (2022). A retrospective study on the incidence of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) associated with different preventive dental care modalities. Supportive Care in Cancer, 30, 1723–1729. [CrossRef]

| STAGE | CLINICAL SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | CT SIGNS |

|

Stage 1 - FOCAL MRONJ The presence of at least 1 clinical sign/symptom and increased bone density limited to the alveolar process at CT, with or without additional radiological signs. Stage 1a: Asymptomatic (without pain) Stage 1b: Symptomatic (the presence of pain and/or purulent discharge) |

Abscess, bone exposure, halitosis, intraoral fistula, jaw pain of bone origin, mucosal inflammation, non-healing post-extraction socket, soft tissue swelling, spontaneous loss of bone fragments, sudden dental/implant mobility, purulent discharge, toothache and trismus. |

Trabecular thickening and/or focal bone marrow sclerosis, with or without cortical erosion, osteolytic changes, thickening of the alveolar ridge, thickening of the lamina dura, persistent post-extraction socket, periodontal space widening, thickening of the inferior alveolar nerve canal, sequester formation. |

|

Stage 2 - DIFFUSE MRONJ The presence of at least 1 clinical sign/symptom and increased bone density extending to the basal bone at CT, with or without additional radiological signs. Stage 2a: asymptomatic (without pain) Stage 2b: symptomatic (presence of pain and/or purulent discharge) |

Same as Stage 1, plus mandibular deformation and numbness of the lips. |

Diffuse bone marrow sclerosis, with or without cortical erosion, osteolytic changes, thickening of the alveolar ridge, thickening of the lamina dura, persistent post-extraction socket, periodontal space widening, thickening of the inferior alveolar nerve canal, sequester formation, periosteal reaction and opacified maxillary sinus. |

|

Stage 3 - COMPLICATED MRONJ The presence of at least 1 clinical sign/symptom and increased bone density extended to the basal bone at CT, plus one or more of the following Stage 3a: asymptomatic (without pain) Stage 3b: symptomatic (presence of pain and/or purulent discharge) |

Cutaneous fistula, mandible fracture, fluid discharge from the nose. |

Osteosclerosis of adjacent bones (zygoma and hard palate), pathologic fracture, osteolysis extending to the maxillary sinus, sinus tract (oroantral, oronasal fistula, oro-cutaneous). |

| STAGE | SYMPOTMS | CLINICAL FINDINGS | RADIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS |

| Stage 0 | Odontalgia not explained by an odontogenic cause. Dull, aching bone pain in the jaw, which may radiate to the temporomandibular joint region. Sinus pain, which may be associated with inflammation and thickening of the maxillary sinus wall. Altered neurosensory function. |

Loosening of teeth not explained by chronic periodontal disease. Intraoral or extraoral swelling. |

Alveolar bone loss or resorption not attributable to chronic periodontal disease. Changes to trabecular pattern sclerotic bone and no new bone in extraction sockets. Regions of osteosclerosis involving the alveolar bone and/or the surrounding basilar bone. Thickening/obscuring of periodontal ligament (thickening of the lamina dura, sclerosis and decreased size of the periodontal ligament space) |

| Stage I | Asymptomatic | Exposed and necrotic bone or fistula that probes to the bone. No evidence of infection/inflammation. |

may present with radiographic findings mentioned for Stage 0 that are localized to the alveolar bone region |

| Stage II | Symptomatic | Exposed and necrotic bone, or fistula that probes to the bone. Evidence of infection/inflammation. |

may present with radiographic findings mentioned for Stage 0 localized to the alveolar bone region. |

|

Stage III |

Symptomatic | Exposed and necrotic bone or fistulae that probes to the bone. Evidence of infection One or more of the following: Exposed necrotic bone extending beyond the region of alveolar bone (i.e., inferior border and ramus in the mandible, maxillary sinus and zygoma in the maxilla). Extraoral fistula. Oral antral/oral-nasal communication. |

May be present: Pathologic fracture. Osteolysis extending to the inferior border of the mandible or sinus floor |

| N° Patient | Sex | Age | Primary Disease | Comorbidities | Smoking status | BiP Treatment | Triggering cause of BRONJ | BRONJ Stage | BRONJ Resection Site | Presence of Actinomyces |

| 1 | M | 66 | Thyroid Cancer | Hypertension | yes | ZOL | Implant | 1b | Mandible (right side) | yes |

| 2 | F | 80 | Osteoporosis | Diabetes, Familial hypercholesterolemia | no | IBA | Unknown | 2a | Mandible (right side) | no |

| 3 | F | 79 | Osteoporosis | Hypertension | no | IBA | Unknown | 2b | Mandible (left side) | no |

| 4 | F | 63 | Breast Cancer | Hypertension | yes | ZOL | Periodontal Disease | 2b | Mandible (right side) | yes |

| 5 | F | 81 | Breast Cancer | None | no | ZOL | Extraction | 2b | Maxillary (left side) | no |

| 6 | F | 79 | Osteoporosis | Familial hypercholesterolemia | yes | ALE | Extraction | 1a | Mandible (left side) | no |

| 7 | F | 77 | Breast Cancer | Hypertension | yes | ALE | Prosthetic Decubitus | 1a | Mandible (left side) | yes |

| 8 | M | 72 | Multiple Myeloma | Hypertension | yes | ZOL | Prosthetic Decubitus | 2b | Maxillary (left side) | no |

| 9 | M | 77 | Thyroid Cancer | Hypertension, Familial hypercholesterolemia | yes | ZOL | Periodontal Disease | 2a | Maxillary (left side) | no |

| 10 | F | 68 | Multiple Myeloma | Hypertension,Familial hypercholesterolemia | no | ZOL | Periodontal Disease | 2a | Mandible (left side) | yes |

| 11 | F | 68 | Breast Cancer | None | no | ZOL | Unknown | 1b | Maxillary (right side) | no |

| 12 | F | 75 | Multiple Myeloma | Hypertension, Diabetes | no | ZOL | Periodontal Disease | 1b | Mandible (right side) | yes |

| 13 | F | 67 | Breast Cancer | Hypertension | no | ZOL | Extraction | 2a | Mandible (right side) | yes |

| 14 | F | 85 | Breast Cancer | Diabetes, Familial hypercholesterolemia | no | ZOL | Periodontal Disease | 2a | Maxillary (left side) | yes |

| 15 | F | 73 | Osteoporosis | None | no | ALE | Prosthetic Decubitus | 1a | Mandible (left side) | no |

| 16 | M | 69 | Prostate Cancer | Hypertension | yes | ZOL | Periodontal Disease | 1a | Mandible (left side) | no |

| 17 | F | 65 | Osteoporosis | None | yes | ZOL | Implants | 2a | Maxillary (left side) | yes |

| 18 | F | 83 | Osteoporosis | None | yes | ALE | Unknown | 1a | Mandible (left side) | no |

| 19 | F | 86 | Thyroid Cancer | Chronic kidney failure | no | ZOL | Extraction | 2a | Mandible (left side) | no |

| 20 | F | 63 | Osteoporosis | Hypertension | no | ZOL | Unknown | 1a | Mandible (left side) | no |

| 21 | F | 86 | Breast Cancer | Hypertension | yes | ZOL | Periodontal Disease | 2b | Maxillary (right side) | yes |

| Clinical Signs and Symptoms of BRONJ (T0) | N° of Patients | % |

| Exposed bone | 21 | 100 |

| Halitosis | 11 | 52.38 |

| Dental mobility | 7 | 33.33 |

| Pain | 6 | 28.57 |

| Trismus | 5 | 23.81 |

| Failure of post-extraction alveolar mucosa repair | 4 | 19.05 |

| Soft tissue swelling | 3 | 14.29 |

| Lip paresthesia/dysesthesia | 3 | 14.29 |

| Implant mobility | 2 | 9.52 |

| Suppuration | 2 | 9.52 |

| Radiographic Signs of BRONJ (T0) | N° of Patients | % |

| Diffuse Osteosclerosis | 6 | 28.57 |

| Focal Medullary Osteosclerosis | 5 | 23.81 |

| Widening of the Periodontal Space | 5 | 23.81 |

| Persistence of Post-extraction Alveolus | 4 | 19.05 |

| Sinusitis | 4 | 19.05 |

| Thickening of the Alveolar Canal | 2 | 9.52 |

| Oro-antral Fistulas | 2 | 9.52 |

| Periosteal Reaction | 2 | 9.52 |

| N° Patient | T1 Clinical Signs and Symptoms of BRONJ | T1 Radiographic Signs of BRONJ | T2 Clinical Signs and Symptoms of BRONJ | T2 Radiographic Signs of BRONJ | T3 Clinical Signs and Symptoms of BRONJ | T3 Radiographic Signs of BRONJ |

| 1 | Incomplete epithelialization, Dysesthesia | X-rays not performed | Incomplete epithelialization, Dysesthesia | Trabecular thickening | Exposed bone, Dysesthesia, Pain | Focal medullary osteosclerosis |

| 8 | Incomplete epithelialization | X-rays not performed | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| 13 | Incomplete epithelialization, Trismus | X-rays not performed | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| 14 | Incomplete epithelialization | X-rays not performed | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| 19 | Incomplete epithelialization, Lip Dysesthesia | X-rays not performed | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).