1. Introduction

Minimizing the extent of surgical trauma through endoscopic techniques remains one of the cornerstones in modern surgery. Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery (MIMVS) combines right-sided thoracic endoscopy (thoracoscopy) with a minimal right-sided anterior thoracotomy and enables access to and surgery on the mitral valve. MIMVS has gradually been recognized as an alternative to mitral valve surgery by conventional sternotomy (CS) for treatment of degenerative mitral valve regurgitation[

1]. MIMVS and CS show equally good survival and surgical durability[

2]. In addition, MIMVS appears to shorten hospital length of stay, lower financial cost[

3,

4], lessen bleeding[

5,

6], improve patient satisfaction[

7] and a newly published propensity scored matched metanalysis suggests a mortality benefit[

8]. However, the technique in MIMVS differs widely from CS and demands unique surgical skills and dexterity[

9]. MIMVS also differs from other aspects of heart surgery. The minimal access thus necessitates peripheral cannulation for cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), one-lung ventilation, vacuum assisted CPB, single-dose crystalloid cardioplegia, comprehensive echocardiography as well as specific heart exposure-, de-airing- and CPB weaning procedures[

1]. These altered practices in MIMVS introduce more complex interactions between perfusion, surgery, and anesthesia, making the procedure hard for the entire team to master[

10]. A gradual learning curve has correspondingly been associated with MIMVS[

11,

12]. Concerns thus arise when implementing MIMVS of an increased risk of serious adverse effects, such as stroke and aortic dissection[

7,

13,

14], with some studies showing worse outcomes after MIMVS[

15,

16]. To study the safety of adopting MIMVS, we comprehensively investigated mitral valve surgery, before and after implementing MIMVS in a center without prior experience in the procedure.

2. Materials and Methods

The introduction of MIMVS at the institution followed “the seven pillars of governance”. This framework provides guidance for commencing new treatment or practices in health care[

17]. The National Health Service in the United Kingdom created these guidelines to ensure efficient, safe, and patient centered new treatment realization and has guided MIMVS implementation before[

17].

Two senior surgeons experienced in mitral valve- and minimally invasive surgery, but not in MIMVS, performed all MIMVS procedures. Two senior cardiac anesthesiologist/intensivists certified and proficient in perioperative transesophageal echocardiography provided all the anesthesia. The anesthesiologist/intensivists also attended the patients in the ICU for postoperative care. Other team members initially consisted of the same group of operating room (OR) nurses (three) and perfusionists (three). This latter group gradually added members. The first four cases were proctor supervised (> 5 years of MIMVS experience). The supplementary material offers specifics of the centers CS procedure and implementation of the MIMVS procedure.

The primary investigator (AK) surveyed all completed cardiac surgeries in the timespan (2017–2022) - at least one year after completion of the last surgery included in the study. The supplementary material provides a detailed comprehensive description of data acquisition and handling.

Propensity score adjustment included age at surgery, gender, BSA, EuroScore 2, creatinine, LVEF, stenotic component of mitral valve disease, history of smoking, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or atrial fibrillation. The nearest-neighbour method matched patient with a maximum calliper width of 0.05. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0 for macOS (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0 for macOS, (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Continuous variables, when normally distributed, are expressed as mean including standard deviation (when appropriate) and as median with range when non-normally distributed. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Differences between groups were assessed using T-test, Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U- test or Kolmogorov–Smirnov test as appropriate. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Age (<70 years), size (body surface area [BSA] < 2.3 m2), co-morbidities (Euroscore2 < 2%) and mitral valve pathology (primarily P2 prolapse) served as selection criteria in the first twenty patients. After the first twenty patients, selection for MIMVS was based on the same criteria as CS, but with exclusion criteria for MIMVS continuing to be: dilated ascending aorta (<40 mm); aortic valve regurgitation of more than mild to moderate degree; other concomitant valve surgery; peripheral vascular calcification of more than mild degree on preoperative computer tomography of the aorta (CTA), which all MIMVS candidates received; previous right-sided thoracic interventions or an expectation of right pleural cavity adhesions due to other reasons. Unavailability of the MIMVS team precluded MIMVS, leaving a group of patients receiving CS fulfilling MIMVS criteria after implementation for use in propensity score matching analysis.Anesthesia for MIMVS consisted of propofol instead of sevoflurane to avoid environmental contamination during lung isolation. The double lumen tube employed for lung isolation in MIMVS was exchange for a single lumen tube at the end of surgery. MIMVS monitoring differed by having near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for monitoring cerebral oximetry and by placing external defibrillation to enable external cardioversion/defibrillation. In MIMVS, a central line was placed in the left instead of the right jugular vein to monitor superior vena cava pressure (CVP) during the procedure instead of right atrial pressure. In patients with a BSA of 2.3 m2, or more, a 7fr venous sheath was placed in the right internal jugular vein in the draped surgical field to enable placement of an additional venous return cannula for upper venous return if warranted by inadequate venous drainage. These monitoring measures could also be employed in CS but were not standard. In MIMVS, a triangular wedged cushioning pad was placed under the patient, elevating the right hemithorax in the supine position. Straps and cushioning protected the right arm just below the level of the operating table, facilitating right-sided surgical access. Standard supine positioning with arms tugged next to the patient enabled access in CS.Otherwise, anesthesia monitoring and maintenance in MIMVS duplicated CS and consisted of left radial artery pressure, five lead electrocardiogram, TEE (Philips Healthcare, Inc., Andover, MA, USA), foley catheter with temperature monitoring and anesthesia machine monitoring (Philips Healthcare, Inc., Andover, MA, USA). The attending anesthesiologist decided perioperative care such as intra/postoperative transfusion, timing of tracheal extubation and intensive care unit management and -discharge.MIMVS only necessitated a 4-6 cm skin incision and - retraction with a Soft Tissue Retractor (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, California, USA) gently aided by a small standard retractor in the right 4th intercostal space at the anterior axillary line – see picture 1. The camera port, the atrial retractor, and the aortic clamp required additional small (2–10 mm) puncture incisions in the 2nd/3rd parasternal, 2nd and 6th lateral intercostal spaces respectively on the right side. An Endo Close™ trocar Site Closure Device (Medtronic Plc, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) facilitated placing a pericardial stay suture through the aortic clamp incision.A transverse right sided groin incision (3-5 cm) exposed the femoral vessels for cardiopulmonary bypass cannulation. Left sided vessels replaced right sided vessels in case of an inaccessible right groin. Careful TEE examination ensured correct tip positioning in the superior vena cava of a 25 Fr multistage Biomedicus Quickdraw venous cannula (Medtronic Plc, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA/Edwards Lifesciences Inc., Irvine, California, USA) and a guidewire in the aorta from a 17-19 Fr Biomedicus arterial cannula (Medtronic Plc, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). Seldinger technique facilitated the placement of both arterial and venous cannulas through the femoral vessels. Vacuum (− 40 to − 70 mmHg) assisted roller-pump cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) targeted a cardiac index of at least 2.4 L/min and an activated clotting time (ACT) above 480 seconds using heparin anticoagulation. A standard heater/cooler system cooled the patients to 34° C. Norepinephrine administration during CPB ensured a mean arterial pressure (MAP) minus superior CVP of 45-60mmhg. A LigaSure (Medtronic Plc, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) sealer ensured hemostatic pericardial fat resection and division of the pericardium anterior to the phrenic nerve. The division opened the pericardium from the superior vena cava to approximately two centimeters superior to the diaphragm allowing access to the heart. A needle vent cannula placed in the ascending aorta served as cardioplegia administration site as well as a vent for deairing. A transthoracic Chitwood (Fehling Instruments GMBH & CO. KG, Karlstein, Germany) clamp cross-clamped the aorta and 1500 ml of crystalloid cardioplegia (Custodiol-CE; Dr. Franz Köhler Chemie, Bensheim, Germany) arrested the heart. In case of cardiac activity any time during the procedure an additional dose of cardioplegia (1000 ml) and aortic cross-clamp repositioning mitigated the risk of inadequate myocardial protection. Carbon dioxide flooded the surgical field through the camera port. Paraseptal atriotomy (Sondergaards grove access) exposed the mitral valve by an Obadia 3D Atrial Retractor with Flex Blade (Delacroix-Chevalier, Paris, France) fixed through the small parasternal intercostal space incision. Adjusting the retractor in case of CVP increase or NIRS decrease reduced the risk of inadequate cerebral venous drainage. After closure of the left atrium, but before aortic clamp release, pace-wires were placed exiting the chest via the atrial retractor incision. Weaning from CPB was done twice. The first wean served to carefully deair the heart via the aorta needle vent catheter and by gradual levelling the patient from the deep Trendelenburg position (initiated just before clamp release), while on full lung ventilation for maximum venting. The patient returned to CPB after careful TEE evaluation of the surgical result and for complications as well as remaining air. Vent needle removal from the aorta could thus be done safely while on CPB. Electrocautery and occasional suturing completed hemostatic maneuvers of surgical sites in the mediastinum and chest wall, which received an intercostal nerve injection for postoperative pain relief. During peripheral CPB, increased risk of watershed phenomenon exists, whenever the aorta is not cross clamped if the heart ejects poorly oxygenated blood. One-lung ventilation thus persisted whenever possible to avoid poorly oxygenated blood getting ejected from the heart and preferentially going to the head and coronary arteries. Second and final wean from CPB, cannula removal and protamine administration followed hemostatic maneuvers, but preceded skin and soft tissue closure in the right hemithorax. At the end of surgery, the double lumen tube was exchanged for a single lumen tube and the patients were transferred intubated to ICU for standardized postoperative care.CS patients received standard median sternotomy, -pericardial opening, intermittent cold blood cardioplegia, -aortic- and -double venous cannulation. MIMVS employed Cor-Knot fastener (LSI solutions, Victor, NY, USA) instead of manual surgical knots to secure ring or valve and a self-made leaflet separator facilitating neo-chord placement. The method of mitral valve repair and replacement was performed according to the experience of the senior mitral valve surgeons. Direct visual inspection aided by comprehensive intraoperative TEE determined surgical decision-making regarding mitral valve operability and focused especially on lesion location, repairability, calcifications and systolic anterior motion (SAM) risk.

Description of Data Acquisition

The primary investigator (AK) surveyed all completed cardiac surgeries in the timespan (May 1st, 2017–February 28th, 2022) via the OR schedule using the Snap Board featured in the Centers electronic medical record (EMR) system (EPIC System, Madison, Wisconsin, United States). The EMR preoperative standardized heart team conference-, admission history- and physical chart note provided data on patient demographics and co-morbidities. The standardized surgical post procedure note provided surgical data such as ring/valve type and size, left atrial closure and cryo-maze procedure. A search in the automated barcode scanned implant history system of the EMR verified the surgical data. A Patient Advocate Tracking System (PATS) online data-spreadsheet also provided perfusion related information in the centers data management. PATS is registered real-time by the perfusionists during surgery at the institution. Both PATS and EPIC thus provided perfusion related data (CPB time, cross-clamp time, BSA and EuroScore 2). If minor inconsistencies existed between data in PATS and EPIC such as in the EuroScore 2, the least favorable data point would be used (e.g., highest EuroScore 2). The Phillips Intellispace Carciovascular (Philips Healthcare, Inc., Andover, MA) and Xeroviewer (AGFA healthcare, Mortsel, Belgium) systems provided echocardiographic data. The cardiologist report of the echocardiography conducted before (closest date) and after the surgery (latest date up to one year) served as data entry points. In case of non-description of relevant echocardiographic findings in the report, the next closest echocardiography would be used as entry point. The EMR’s “Patient Station” provided real time admission, transfer, discharge, and readmission data.Patient outcome data was also collected from the EMR. Either from automated integrated electronic transfer to the EMR, such as from ICU ventilators and medicine infusion pumps or from hourly electronic observation charts in the EMR such as for bleeding or urine output in both the ICU and OR. The blood banks EMR integrated data system provided blood product administration information and consisted of blood products handed out and not returned to the blood bank. The EMR’s integrated laboratory value reporting system provided laboratory values. Neuroimaging data was recorded from XeroViewer (AGFA healthcare, Mortsel, Belgium) as scans performed and reported. Neurologic incidents were recorded as any neuro consult that described neuro deficits in any patient note up to one year following surgery. The outcomes of atrial fibrillation, pacemaker, pleural or pericardial effusion were likewise collected based on any patient note describing these occurrences. The EMR’ free standing word search system served to cross-check for these outcomes by searching the following: “atrial...”, “neuro...”, ”pace…”, “pleu...” and “peri…”. The Danish central citizen registry served to cross-check the outcome of death and the centralized Danish EMR system (“Sundhedsjournalen”) served to cross-check on other outcomes. The “Sundhedsjournal” provides centralized data on all health data across all vendors, independent of geographical location or health care settings in all health care facilities. Availability of datapoint is expressed in parenthesis in tables.

3. Results

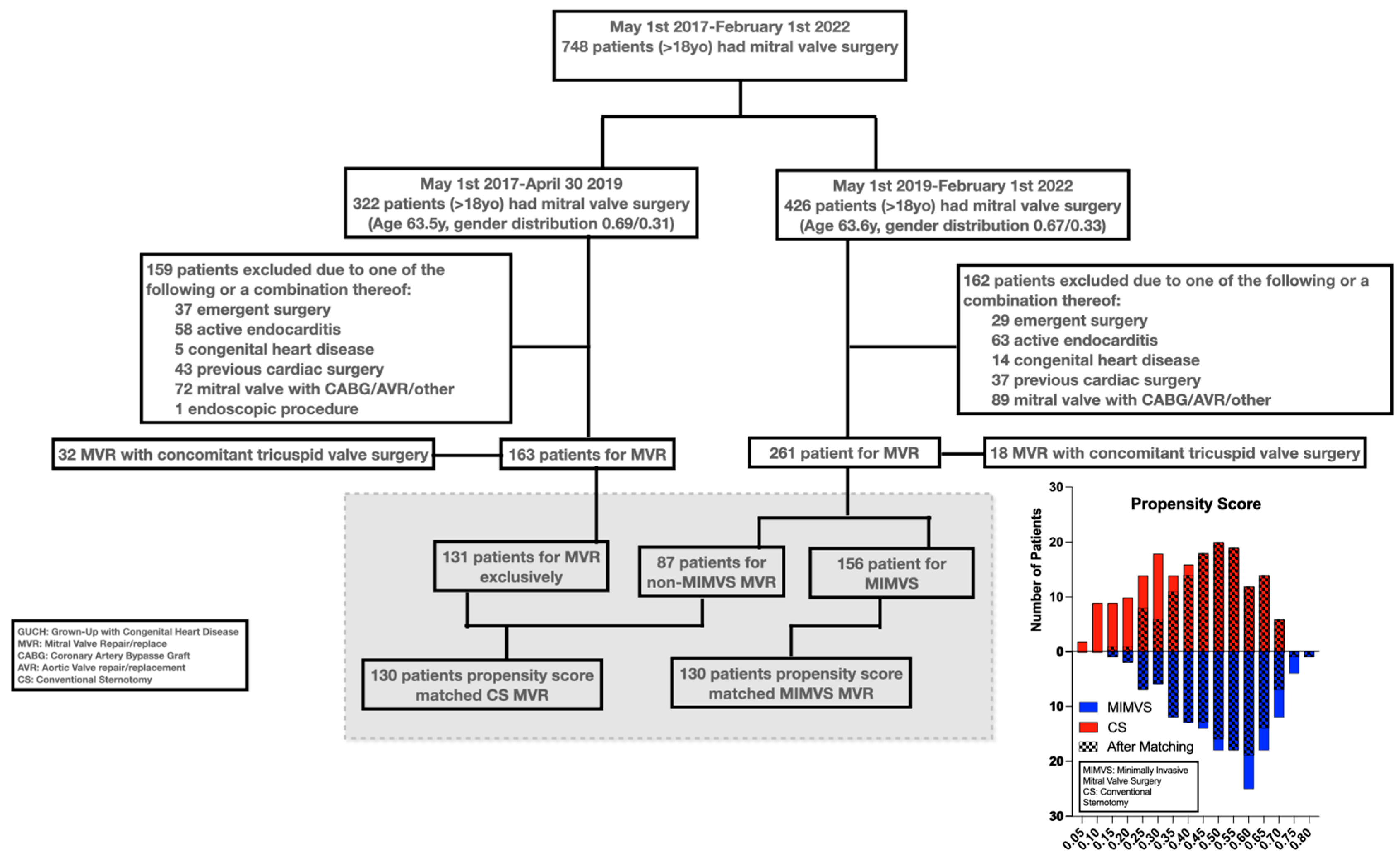

Seven hundred forty-eight patients underwent screening in the study - 424 underwent assessment.

Figure 1 shows patient selection and the histographic alignment in propensity score.

Table 1 though 4 provides overview of data from patients (supplementary material shows full overview of all data assessed).

3.1. Matching

Mean and median propensity score margins were both 0.006 (range -0.015-0.05, interquartile range -0.002-0.014).

Matching mitigated pre-existing significant differences in gender (34% vs 32%, p=0.7), size (BSA of 1.93 m2 vs 1.94 m2, p=0.7), age (64 vs 64 years, p=0.6), rate of atrial fibrillation (30% vs 34%, p=0.6) and Euroscore 2 (1.38% vs 1.43%, p=0.7) in patients receiving CS compared to MIMVS. Significant differences persisted in CAD frequency after matching (19% vs 36%, p=0.003).

3.2. Surgical Technique

Table 2 displays surgical interventions in the study. After patient matching the repair versus replace rate was similar (79% vs 85%, p=0.2). Repair technique changed significantly after MIMVS implementation.

More chord placement (57% vs 83%, p<0.001)

Less left atrial appendage closure (28% vs 43%, p=0.009)

Smaller ring sizes (34 mm vs 36mm, p<0.001)

Rate of tissue valve (11% vs 17%, p=0.15) and mechanical valve replacement (3.1% vs 4.6%, p=0.5) did not differ significantly.

3.3. Patient Outcome

Table 3 shows outcomes. MIMVS was longer.

Operating-, CPB- (180 vs 102 min, p<0.001) and aortic cross-clamp- (98 vs. 81 min, p<0.001) (5.5 vs 4.3 hours, p<0.001) increased.

Longer procedure time appeared to affect extubation in MIMVS slightly (10 vs 9 hours, p=0.009).

Hower, MIMVS in-hospital time decrased significantly

ICU re-admissions occurred less (0 vs 3.1%, p=0.045).

Hospital discharge shortened (p<0.001, median 5 vs 7).

Patient centered outcomes such as neurologic-, effusion- and reintervention endpoints showed non-significant small differences.

Postoperative atrial fibrillation and endocarditis/mediastinitis occurred significantly less in MIMVS (42% vs 70%, p<0.001/0 vs 3.1%, p= 0.044)

4. Discussion

This retrospective report shows that MIMVS introduction in a mitral valve surgical center without prior experience looks safe and feasible.

Longer surgical-, CPB- and aortic cross-clamp times seemed not to affect one year survival, hospital length of stays or subordinate in-hospital outcomes such as ICU length of stay, bleeding, or transfusion requirement.

Interestingly, the study showed that surgical repair technique changed with MIMVS introduction.

The patient population presenting for mitral valve surgery in this study resembles published large databases[

18]. The findings thus seem generalizable for the surgical mitral valve patient population. The more frequent occurrence of mild CAD, also after propensity score matching, could likely be explained by a transition from evaluating selected risk patients by catheter-based angiogram to broadly screening all cardiac surgery patients with CT based angiogram during the timespan of the study.

In this study MIMVS adoption correlated to a changed surgical repair technique. Thus, smaller ring size and more chord placement occurred after MIMVS introduction, likely reflecting a move away from correcting lesions by resection and stitching to a strategy of displacing scallops using artificial chords. Editorials discuss these two diverging strategies [

19]. A recent large metanalysis of more than 6,000 patients favored the displacement technique[

20] by showing hard endpoints such as operative mortality differing supporting the change in strategy observed in the current study. Minimal invasive approaches combine more readily with the displacement technique[

19,

21], because of the constrained instrument movement, when repairing the valve, contributing to the transition to the displacement strategy.

The current study showed that mitral valve repair takes longer by MIMVS. Several previous studies support this finding[

11,

21]. Counterintuitively, the longer duration of MIMVS contrasted to a finding of shorter hospital stay of up to two days. Meta-analyses and randomized clinical trial have found similar benefits of approximately two days shorter hospital stay in MIMVS[

21]. Hospital stays in MIMVS could likely shorten due to factors such as less pain and early mobilization. Shorter hospitalization with the potential of lowering cost to both patients and hospitals highly favors adopting MIMVS along with a possible decrease in rare events such as ICU re-admission or serious chest infections. However, Chikwe et al. [

22] showed that low volume mitral valve centers (<50 mitral valve operations per surgeon per year) might encounter challenges in outcomes due to lack of exposure and hence experience. Thus, Müller[

13] recently suggested the need for at least two MIMVS per week to ensure excellence, which equals more than 100 surgeries needed per year. However, in the current study we found no indication that a volume of 50-60 MIMVS per year at start-up correlated with poorer outcomes when adopting MIMVS. A recent well-conducted multicenter randomized trial with approximately the same number of patients as in the current trial recently reported almost identical outcomes in the safety parameters of death, stroke, and ICU length of stay[

21]. The current study therefore suggest that high-quality treatment can be achieved by firm adherence to a strict implementation strategy.

Several limitations exist in this investigation. The single center retrospective study design creates a risk of detection and selection bias. Matching by propensity score balances known diverging variables among patients, but unmeasured variables still might skew results. Furthermore, treatment success depends on a longer period of follow-up than the one year reported in the current study.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective implementation study of adopting MIMVS in a center without prior experience in the procedure showed feasibility and equally good outcomes when compared to CS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AK, PHMS, JEM and CLC; methodology, AK and CLC.; formal analysis, AK; investigation, AK; data curation, AK; writing—original draft preparation, AK; writing—review and editing, AK, PHMS, JEM and CLC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Danish law (Danish Health Care Law §42d), which mandates physicians to follow patients’ outcomes after implementing new treatments. The Danish Capital Region Regional Ethics Committee approved the research. Individual patients consented for surgery and data collection, but due to the retrospective nature of the investigation, the Danish Capital Region Regional Ethics Committee waived requirement for additional informed study consent (protocol# F-22051524).

Data Availability Statement

All data will be share upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| BSA |

Body surface area |

| CAD |

Coronary artery disease |

| CPB |

Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| CS |

Conventional sternotomy |

| CTCA |

Computer tomography coronary angiogram |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| LVEF |

Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MIMVS |

Minimally invasive mitral valve surgery |

| MR |

Mitral regurgitation |

| MV |

Mitral valve |

| MVR |

Mitral valve repair/replacement |

References

- Modi, P.; Hassan, A.; Chitwood, W.R. Minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2008, 34, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, A.B.; Atluri, P.; Szeto, W.Y.; et al. Minimally invasive approach provides at least equivalent results for surgical correction of mitral regurgitation: A propensity-matched comparison. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013, 145, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iribarne, A.; Easterwood, R.; Russo, M.J.; et al. A minimally invasive approach is more cost-effective than a traditional sternotomy approach for mitral valve surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011, 142, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perin, G.; Shaw, M.; Toolan, C.; et al. Cost Analysis of Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery in the UK National Health Service. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021, 112, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, L.G.; Atik, F.A.; Cosgrove, D.M.; et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional mitral valve surgery: A propensity-matched comparison. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010, 139, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscarelli, M.; Fattouch, K.; Casula, R.; et al. What Is the Role of Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery in High-Risk Patients? A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016, 101, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.C.H.; Martin, J.; Lal, A.; et al. Minimally Invasive Versus Conventional Open Mitral Valve Surgery. Innovations Technology Techniques Cardiothorac Vasc Surg. 2011, 6, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Swystun, A.G.; Caputo, M.; et al. A review and meta-analysis of conventional sternotomy versus minimally invasive mitral valve surgery for degenerative mitral valve disease focused on the last decade of evidence. Perfusion. 2023, 026765912311745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammie, J.S.; Bartlett, S.T.; Griffith, B.P. Small-Incision Mitral Valve Repair: Safe, Durable, and Approaching Perfection. Ann Surg. 2009, 250, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.J.; Smood, B.; Atluri, P. Commentary: Transitioning to Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Repair—Navigating the Gauntlet. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021, 32, 838–839. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Omar, Y.; Fazmin, I.T.; Ali, J.M.; et al. Minimally invasive mitral valve surgery. J Thorac Dis. 2020, 13, 1960–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzhey, D.M.; Seeburger, J.; Misfeld, M.; et al. Learning minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: a cumulative sum sequential probability analysis of 3895 operations from a single high-volume center. Circulation. 2013, 128, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.C. Is minimally invasive mitral valve surgery equal to or worse than a full sternotomy: a perspective from the Netherlands National Heart Registration. Eur J cardio-Thorac Surg : Off J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2021, 61, 1107–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, C.; Marchetto, G.; Ricci, D.; et al. Temporary Neurological Dysfunction After Minimal Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery: Influence of Type of Perfusion and Aortic Clamping Technique. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017, 103, 691–692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olsthoorn, J.R.; Heuts, S.; Houterman, S.; et al. Effect of minimally invasive mitral valve surgery compared to sternotomy on short- and long-term outcomes: a retrospective multicentre interventional cohort study based on Netherlands Heart Registration. Eur J cardio-Thorac Surg : Off J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2021, 61, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, J.; Lorenzen, U.; Borzikowsky, C.; et al. Unilateral pulmonary oedema after minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: a single-centre experience. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2017, 53, 764–770. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, S. How to start a minimal access mitral valve program. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013, 2, 77478–77778. [Google Scholar]

- Gammie, J.S.; Chikwe, J.; Badhwar, V.; et al. Isolated Mitral Valve Surgery: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database Analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018, 106, 716–727. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus, G.D.; Dulguerov, F.; Marcacci, C.; et al. “Respect when you can, resect when you should”: A realistic approach to posterior leaflet mitral valve repair. The J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018, 156, 1856–1866.e3. [Google Scholar]

- Sa, M. P.; Cavalcanti, L. R. P.; Van den Eynde, J.; et al. Respect versus resect approaches for mitral valve repair: A study-level meta-analysis. Trends Cardiovasc Medicine. 2023, 33, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, R.H.; Kasim, A.S.; Zacharias, J.; et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional sternotomy for Mitral valve repair: protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial (UK Mini Mitral). Bmj Open. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Chikwe, J.; Toyoda, N.; Anyanwu, A.C.; et al. Relation of Mitral Valve Surgery Volume to Repair Rate, Durability, and Survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017, 69, 2397–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).