Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Simulation Model and Methods

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Occupancy and Free Energy of Occupancy Fluctuations:

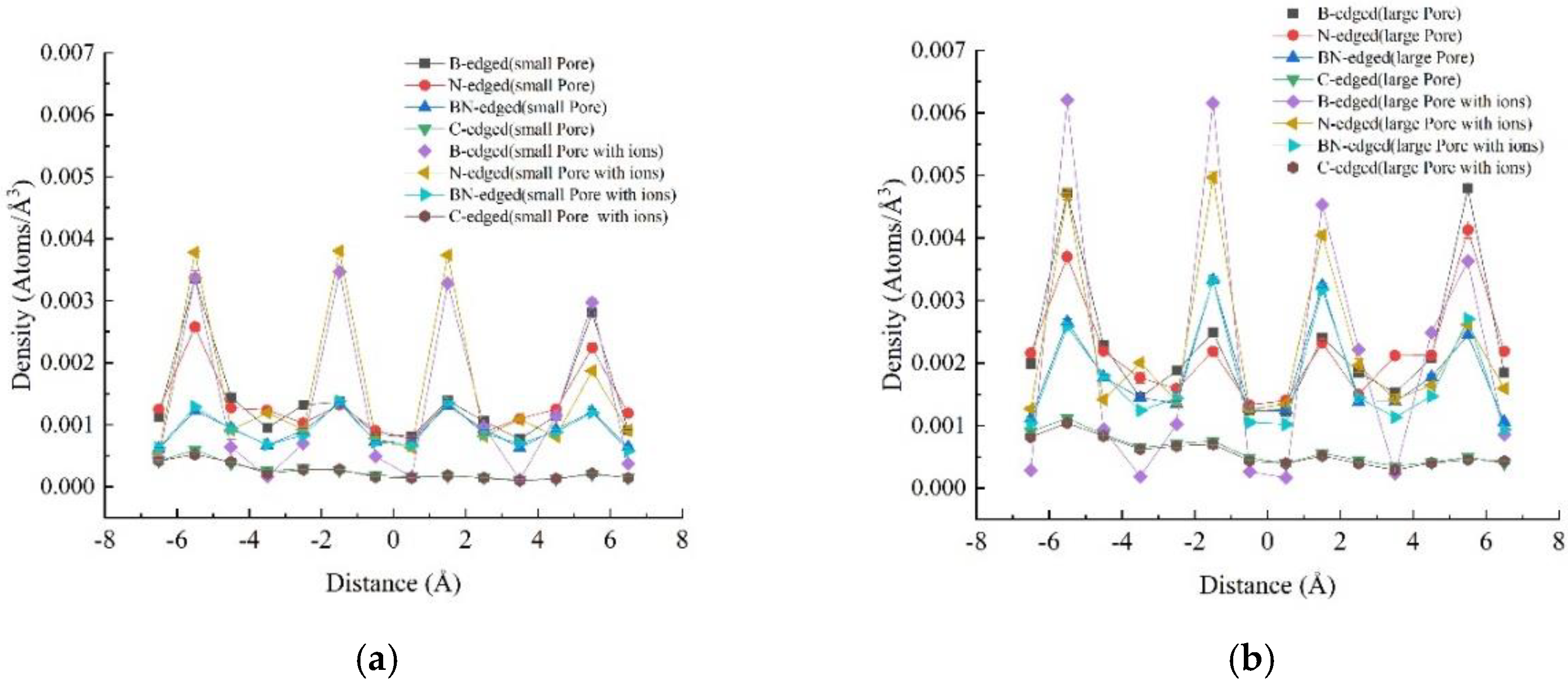

3.2. Density Profiles

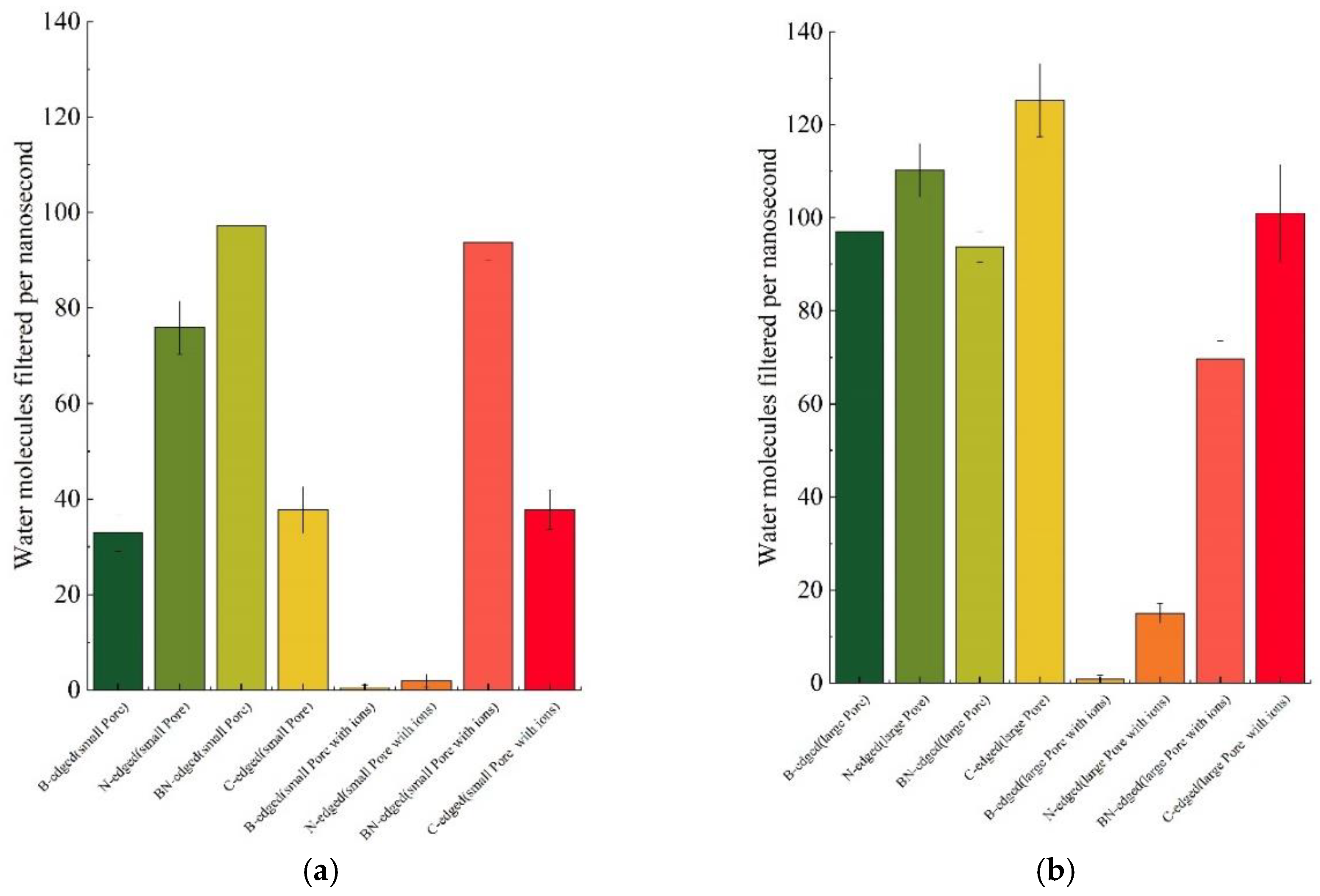

3.3. Water Conduction

4. Conclusion

References

- Alamaro, M. Water Politics Must Adapt to a Warming World. Nature 2014, 514 (7520), 7–7. [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, J. The Rising Pressure of Global Water Shortages. Nature 2015, 517 (7532), 6–6. [CrossRef]

- Elimelech, M.; Phillip, W. A. The Future of Seawater Desalination: Energy, Technology, and the Environment. Science 2011, 333 (6043), 712–717. [CrossRef]

- Vörösmarty, C. J.; Green, P.; Salisbury, J.; Lammers, R. B. Global Water Resources: Vulnerability from Climate Change and Population Growth. Science 2000, 289 (5477), 284–288. [CrossRef]

- Elimelech, M. The Global Challenge for Adequate and Safe Water. Journal of Water Supply: Research and Technology-Aqua 2006, 55 (1), 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, X.; Yu, H.; Zou, Y.; Dong, X. Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance of Boron and Phosphorous Co-Doped Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheets for Removal of Organic Pollutants. Separation and Purification Technology 2019, 226, 128–137. [CrossRef]

- Manan, S.; Ullah, M. W.; Ul-Islam, M.; Atta, O. M.; Yang, G. Synthesis and Applications of Fungal Mycelium-Based Advanced Functional Materials. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts 2021, 6 (1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Ni, Y.; Yan, L. Oxidation of Furfural to Maleic Acid and Fumaric Acid in Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) under Vanadium Pentoxide Catalysis. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts 2021, 6 (1), 39–44. [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, N.; Ghalamchi, L.; Vatanpour, V.; Khataee, A. Photocatalytic-Membrane Technology: A Critical Review for Membrane Fouling Mitigation. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2021, 93, 101–116. [CrossRef]

- Younos, T.; Tulou, K. E. Overview of Desalination Techniques. Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education 2005, 132 (1), 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Shon, H. K.; Phuntsho, S.; Vigneswaran, S.; Cho, J. Nanofiltration for Water and Wastewater Treatment - A Mini Review. Drinking Water Engineering and Science 2013, 6, 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Shenvi, S. S.; Isloor, A. M.; Ismail, A. F. A Review on RO Membrane Technology: Developments and Challenges. Desalination 2015, 368, 10–26. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. L.; Ooi, B. S.; Choudhury, J. P. Preparation and Characterization of Co-Polyamide Thin Film Composite Membrane from Piperazine and 3,5-Diaminobenzoic Acid. Desalination 2003, 158 (1), 101–108. [CrossRef]

- Shawky, H. A. Performance of Aromatic Polyamide RO Membranes Synthesized by Interfacial Polycondensation Process in a Water–Tetrahydrofuran System. Journal of Membrane Science 2009, 339 (1), 209–214. [CrossRef]

- Park, H. B.; Kamcev, J.; Robeson, L. M.; Elimelech, M.; Freeman, B. D. Maximizing the Right Stuff: The Trade-off between Membrane Permeability and Selectivity. Science 2017, 356 (6343), eaab0530. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, G.; Wang, X.; Ding, J. Molecular Dynamics Study on the Reverse Osmosis Using Multilayer Porous Graphene Membranes. Nanomaterials 2018, 8 (10). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, Z.; Gupta, K. M.; Shi, Q.; Lu, R. Molecular Dynamics Study on Water Desalination through Functionalized Nanoporous Graphene. Carbon 2017, 116. [CrossRef]

- Konatham, D.; Yu, J.; Ho, T. A.; Striolo, A. Simulation Insights for Graphene-Based Water Desalination Membranes. Langmuir 2013, 29 (38), 11884–11897. [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Tanugi, D.; Grossman, J. C. Water Desalination across Nanoporous Graphene. Nano Lett. 2012, 12 (7), 3602–3608. [CrossRef]

- Ning, G.; Fan, Z.; Wang, G.; Gao, J.; Qian, W.; Wei, F. Gram-Scale Synthesis of Nanomesh Graphene with High Surface Area and Its Application in Supercapacitor Electrodes. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47 (21), 5976–5978. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Fan, Z.; Wei, T.; Qian, W.; Zhang, M.; Wei, F. Fast and Reversible Surface Redox Reaction of Graphene–MnO2 Composites as Supercapacitor Electrodes. Carbon 2010, 48 (13), 3825–3833. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wu, S.; Wang, D.; Xie, G.; Cheng, M.; Wang, G.; Yang, W.; Chen, P.; Shi, D.; Zhang, G. Fabrication of High-Quality All-Graphene Devices with Low Contact Resistances. Nano Research 2014, 7 (10), 1449–1456. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Qin, H.; Huang, J.; Huan, S.; Hui, D. Mechanical Properties of Boron Nitride Sheet with Randomly Distributed Vacancy Defects. 2019, 8 (1), 210–217. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, G. F.; Xu, Q.; Hage, S.; Luik, S.; Spoor, J. N. H.; Malladi, S.; Zandbergen, H.; Dekker, C. Tailoring the Hydrophobicity of Graphene for Its Use as Nanopores for DNA Translocation. Nature Communications 2013, 4 (1), 2619. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C. Y.; Zulhairun, A. K.; Wong, T. W.; Alireza, S.; Marzuki, M. S. A.; Ismail, A. F. Water Transport Properties of Boron Nitride Nanosheets Mixed Matrix Membranes for Humic Acid Removal. Heliyon 2019, 5 (1), e01142. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B. B.; Govind Rajan, A. How Grain Boundaries and Interfacial Electrostatic Interactions Modulate Water Desalination via Nanoporous Hexagonal Boron Nitride. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126 (6), 1284–1300. [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, R.; Azamat, J.; Erfan-Niya, H.; Hosseini, M. Molecular Insights into Effective Water Desalination through Functionalized Nanoporous Boron Nitride Nanosheet Membranes. Applied Surface Science 2019, 471, 921–928. [CrossRef]

- Loh, G. C. Fast Water Desalination by Carbon-Doped Boron Nitride Monolayer: Transport Assisted by Water Clustering at Pores. Nanotechnology 2018, 30 (5), 055401. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhi, C.; Weng, Q.; Bando, Y.; Golberg, D. Boron Nitride Nanosheets: Novel Syntheses and Applications in Polymeric Composites. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2013, 471 (1), 012003. [CrossRef]

- Golberg, D.; Bando, Y.; Huang, Y.; Terao, T.; Mitome, M.; Tang, C.; Zhi, C. Boron Nitride Nanotubes and Nanosheets. ACS Nano 2010, 4 (6), 2979–2993. [CrossRef]

- Geick, R.; Perry, C. H.; Rupprecht, G. Normal Modes in Hexagonal Boron Nitride. Phys. Rev. 1966, 146 (2), 543–547. [CrossRef]

- Cartamil-Bueno, S. J.; Cavalieri, M.; Wang, R.; Houri, S.; Hofmann, S.; van der Zant, H. S. J. Mechanical Characterization and Cleaning of CVD Single-Layer h-BN Resonators. npj 2D Materials and Applications 2017, 1 (1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Alem, N.; Erni, R.; Kisielowski, C.; Rossell, M. D.; Gannett, W.; Zettl, A. Atomically Thin Hexagonal Boron Nitride Probed by Ultrahigh-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80 (15), 155425. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Song, M.; Jiang, L.; Fu, G.; Li, J. Hexagonal Boron Nitride with Nanoslits as a Membrane for Water Desalination: A Molecular Dynamics Investigation. Separation and Purification Technology 2020, 251, 117409. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Liu, S.; Dai, X.; Chen, S. H.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, R. Nanoporous Boron Nitride for High Efficient Water Desalination. bioRxiv 2018, 500876. [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L.; Ma, X.; Li, C.; Li, Q. Insights into Water Permeability and Hg2+ Removal Using Two-Dimensional Nanoporous Boron Nitride. New J. Chem. 2020, 44 (41), 18084–18091. [CrossRef]

- OneAngstrom. SAMSON, 2020. https://www.samson-connect.net/.

- Hockney, R. W.; Eastwood, J. W. Computer Simulation Using Particles; 1988.

- Thompson, A. P.; Aktulga, H. M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D. S.; Brown, W. M.; Crozier, P. S.; in ’t Veld, P. J.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S. G.; Nguyen, T. D.; Shan, R.; Stevens, M. J.; Tranchida, J.; Trott, C.; Plimpton, S. J. LAMMPS - a Flexible Simulation Tool for Particle-Based Materials Modeling at the Atomic, Meso, and Continuum Scales. Computer Physics Communications 2022, 271, 108171. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics 1996, 14 (1), 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. J.; Holian, B. L. The Nose–Hoover Thermostat. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83 (8), 4069–4074. [CrossRef]

- Ryckaert, J.-P.; Ciccotti, G.; Berendsen, H. J. C. Numerical Integration of the Cartesian Equations of Motion of a System with Constraints: Molecular Dynamics of n-Alkanes. Journal of Computational Physics 1977, 23 (3), 327–341. [CrossRef]

- Chogani, A.; Moosavi, A.; Bagheri Sarvestani, A.; Shariat, M. The Effect of Chemical Functional Groups and Salt Concentration on Performance of Single-Layer Graphene Membrane in Water Desalination Process: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2020, 301, 112478. [CrossRef]

- Hummer, G.; Rasaiah, J. C.; Noworyta, J. P. Water Conduction through the Hydrophobic Channel of a Carbon Nanotube. Nature 2001, 414 (6860), 188–190. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, F.; Shahbabaei, M.; Kim, D. Deformation Effect on Water Transport through Nanotubes. Energies 2019, 12 (23). [CrossRef]

- Robinson, F.; Park, C.; Kim, M.; Kim, D. Defect Induced Deformation Effect on Water Transport through (6, 6) Carbon Nanotube. Chemical Physics Letters 2021, 778, 138632. [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Robinson, F.; Kim, D. Effect of Layer Orientation and Pore Morphology on Water Transport in Multilayered Porous Graphene. Micromachines 2022, 13 (10). [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Robinson, F.; Kim, D. On the Choice of Different Water Model in Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Nanopore Transport Phenomena. Membranes 2022, 12 (11). [CrossRef]

- Davoy, X.; Gellé, A.; Lebreton, J.-C.; Tabuteau, H.; Soldera, A.; Szymczyk, A.; Ghoufi, A. High Water Flux with Ions Sieving in a Desalination 2D Sub-Nanoporous Boron Nitride Material. ACS Omega 2018, 3 (6), 6305–6310. [CrossRef]

- Tsukanov, A. A.; Shilko, E. V. Computer-Aided Design of Boron Nitride-Based Membranes with Armchair and Zigzag Nanopores for Efficient Water Desalination. Materials 2020, 13 (22). [CrossRef]

- Garnier, L.; Szymczyk, A.; Malfreyt, P.; Ghoufi, A. Physics behind Water Transport through Nanoporous Boron Nitride and Graphene. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7 (17), 3371–3376. [CrossRef]

| σ (Å) | ε (kcal/mol) | |

| O | 3.178 | 0.15587 |

| B | 3.453 | 0.0949 |

| N | 3.365 | 0.1448 |

| C | 3.3997 | 0.0859 |

| Na | 2.217 | 0.3519 |

| Cl | 4.849 | 0.01838 |

| Type | Length (Å) | Width (Å) |

| B-edged (Small pore) | 10.12 | 7.51 |

| N-edged (Small pore) | 10.12 | 7.51 |

| BN-edged (Small pore) | 10.12 | 7.51 |

| C-edged (Small pore) | 9.93 | 7.37 |

| B-edged (Large pore) | 14.46 | 7.51 |

| N-edged (Large pore) | 14.46 | 7.51 |

| BN-edged (Large pore) | 14.46 | 7.51 |

| C-edged (Large pore) | 14.18 | 7.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).