1. Introduction

People’s appearance affects their sense of self-worth. There is a belief that having only a certain figure can make them fulfilled and happy human beings. The canons of beauty have changed over time. For instance, in the past, boyish, curvy or athletic figures were desired in women. Currently, slim figures of women and athletic and muscular bodies of men are glorified. A “perfect” appearance has become a necessity, a feature that determines intelligence and control over life [

1]. This behavior is etiologically related to the pressure of society, which results from contemporary standards of beauty. Unachievable perfection increases criticism of one’s own body image and the risk of certain triggers, such as depression or undertaking restrictive diets, contributing to the development of eating disorders [

2].

Eating disorders are behavioral states characterized by serious and persistent disturbances of eating practices that affect physical, mental and social health [

3]. They are influenced by many factors: biological, personal, family and socio-economic [

2]. Nowadays, social media and wellness culture encourage people to constantly analyze their diet, what often results in a worsening of one’s relationship with food. Giving up specific food products and so-called clean eating – “consuming only foods regarded as healthy, primarily unprocessed” [

4] – usually begins as an attempt to achieve optimal health through attention to diet, but may lead to various eating disorders, including orthorexia nervosa (ON), and ultimately to malnutrition and low quality of life [

5].

ON takes form of an ideology of eating “the only right food”. It involves counting calories, eliminating “fattening” products and generally consuming a very modest group of foods. It can manifest itself with obsessive thoughts about food and constant planning meals, and people struggling with this disorder do not take pleasure in eating because they are afraid of it. Possible health consequences of ON are mineral and vitamin deficiencies, and – as a consequence – osteoporosis, hypertension and anemia [

6].

Limiting or excluding meat and other animal products is becoming increasingly popular, especially among young people. Despite documented health benefits of adopting such dietary patterns, studies show significant relationship between them and eating disorders – more than a half of patients with ON follow different types of vegetarian diets [

7]. The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between orthorexia and plant-based diets and to make an attempt to assess whether such diet types may predispose individuals to orthorexia, or whether orthorexia may contribute to the adoption of such dietary patterns. A particular emphasis was put on the importance of distinguishing between pathological and healthy orthorexia and an urgent need for new diagnostic tools, appropriate for the users of plant-based diets.

2. Plant-Based Diets

More and more people decide to give up meat and other animal products. There is a wide range of plant-based (vegetarian) diets – from less to more restrictive: lacto-ovo-vegetarianism (excludes meat and fish), ovo-vegetarianism (excludes meat, fish and dairy), lacto-vegetarianism (excludes meat, fish and eggs), pescetarianism (excludes only meat), veganism (excludes all animal products). There are also so-called pseudo-vegetarian diets, namely semi-vegetarianism and flexitarianism, in which meat consumption is partially limited [

8].

According to the largest dietetic associations (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, British Dietetic Association), properly balanced vegetarian diets (including vegan) are healthy and can be an appropriate choice for any stage of life (during pregnancy and lactation, in children and in the elderly) and in athletes [

9]. Additionally, the use of plant-based diets can bring numerous health benefits. Compared to meat-eaters, vegetarians (especially vegans) have lower body mass and BMI [

10]. What is more, plant-based diets can reduce the risk of diet-related diseases, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes or some cancers [

8]. However, followers of these diets are prone to deficiency of certain nutrients, namely vitamin B

12 (supplementation of which is essential in a strict plant-based diet), vitamin D, calcium, iodine, iron, zinc, selenium, vitamin A, omega-3 fatty acids and protein [

9,

10,

11].

Usually, adopting a plant-based diet is an attempt to modify eating habits, during which animal-based foods and highly processed foods are replaced – whenever possible – with raw, unprocessed or minimally processed plant-based products. There are several reasons for switching to a vegetarian diet, including health, ethical, or environmental motives [

12].

3. Similarities Between Plant-Based Diets and Orthorexia Nervosa

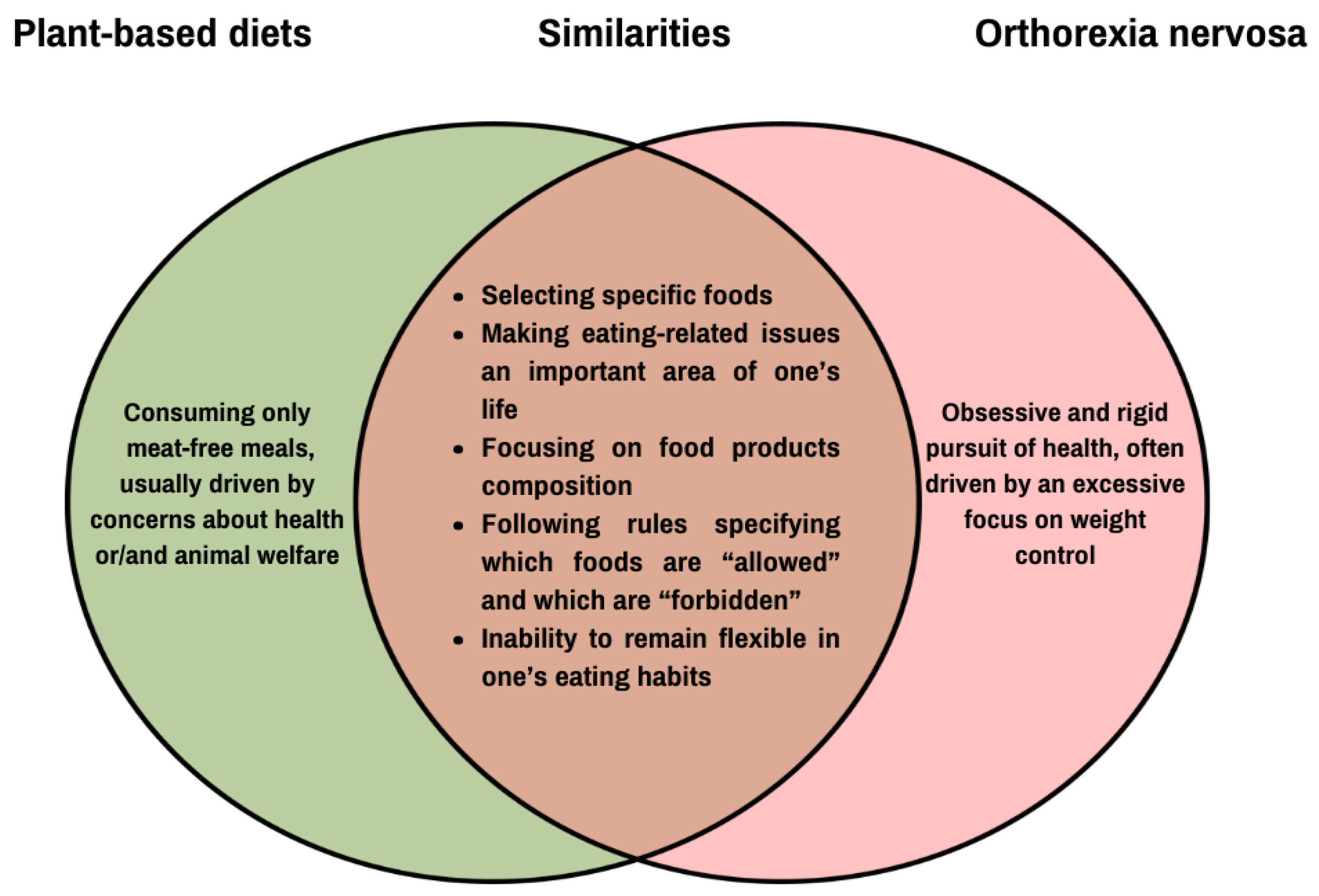

ON shares several features and dieting behaviors with vegetarianism, such as restricting food intake according to specific dietary rules and an inability to be flexible in one’s eating habits (

Figure 1) [

13]. Thus, adhering to these diets involve restrictions resembling cognitive restraint – the intention to continually, consciously control food intake to maintain or lose weight [

14] – often used as an indicator of pathological eating behaviors [

15]. However, it may not be applicable to vegetarians (especially vegans), as their avoidance of animal products is not necessarily indicative of disordered eating [

16]. In fact, a study on vegetarians and vegans showed that both groups had lower cognitive restraint, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating compared to omnivores, but on the other hand, they exhibited more behaviors associated with ON, such as a stronger focus on healthy eating, greater knowledge of it, and a heightened sense of wellbeing related to healthy food choices [

15].

Nevertheless, recent studies suggest that ON is associated with impaired cognitive functions and plant-based diets could be a contributing factor [

13]. Consequently, obsessive thoughts of food – a key feature of ON – appear to be more prevalent among vegetarians than non-vegetarians [

17], potentially putting them at a higher risk of developing orthorexic tendencies or the disorder itself [

15,

18,

19].

4. Healthy Orthorexia

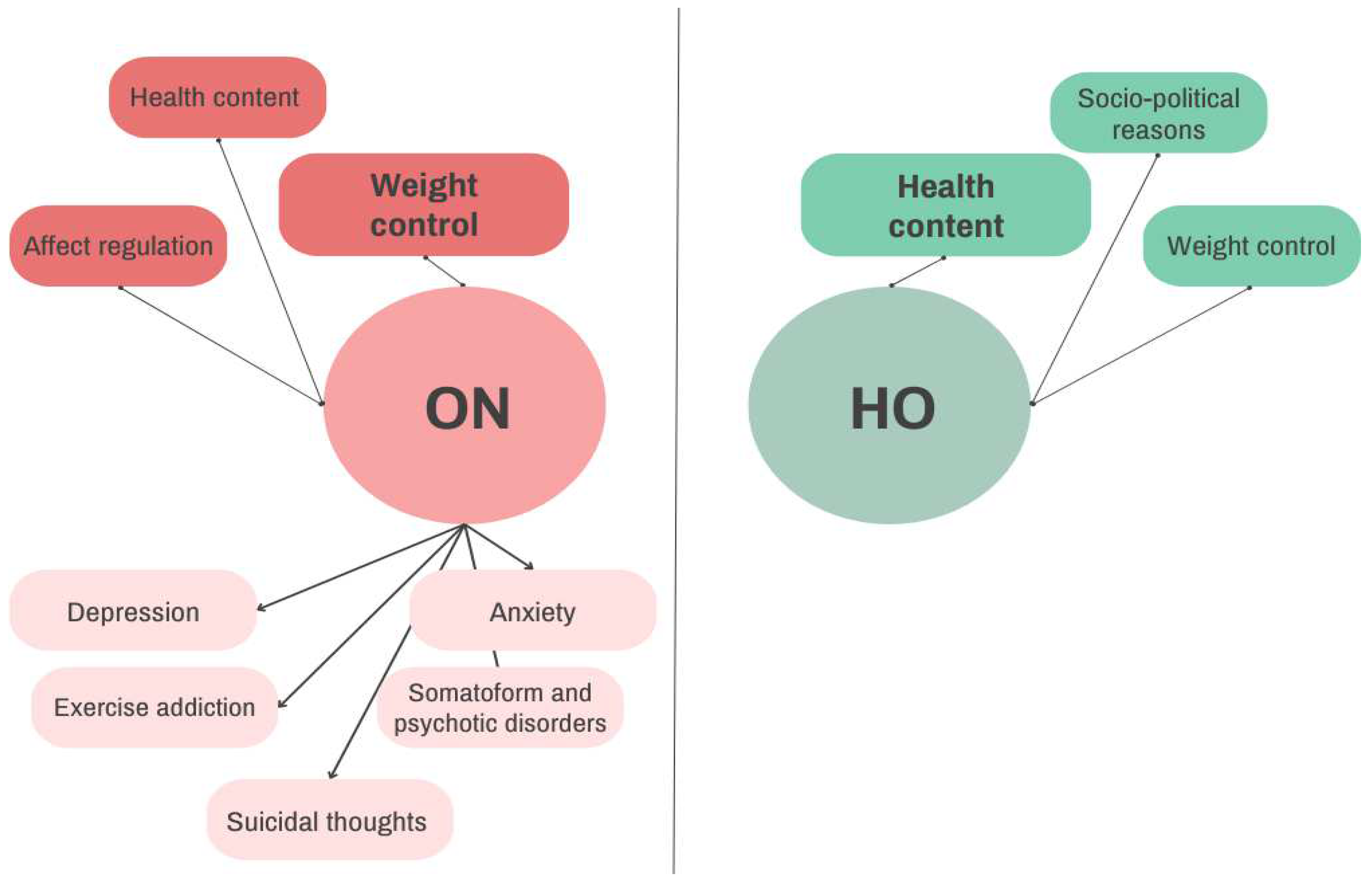

Some studies suggest that orthorexia may also be a non-pathological interest in healthy eating, which is called a healthy orthorexia (HO) [

20]. The bidimensional concept of orthorexia includes both pathological (ON) and non-pathological (HO) aspects of interest in healthy eating, which appear to vary significantly (

Figure 2). In the case of ON, the motive showing the strongest association is weight control. Health content shows negligible and statistically insignificant relationship with ON. In the case of HO, the strongest association is observed with health content, followed by weight control and socio-political reasons [

21]. It should be emphasized, though, that constant cutting down on unacceptable foods, resulting in a diet that includes only a small number of products considered edible, may not necessarily lead to a decrease in overall calories intake, which – in fact – may be even increased in subjects with ON [

22]. Moreover, despite their apparent preoccupation with healthy eating, individuals with ON often exhibit relatively unhealthy eating habits and other undesirable lifestyle behaviors, such as increased screen time or increased smoking and alcohol consumption compared to healthy subjects [

23].

5. Diagnostic Criteria for Orthorexia Nervosa

ON is a relatively newly described eating disorder, and despite the constantly increasing awareness and public interest in it, it cannot be clearly classified as an eating disorder or a mental disorder. The available literature discusses whether ON should be considered a separate disorder, a variation on other disorders, or a cultural attitude [

25,

26,

27]. It should be emphasized that ON is not included in the current Diagnostic Criteria for Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) or in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) [

25,

26,

27]. In addition, diagnosing ON may be difficult due to the lack of standard diagnostic criteria in the main psychiatric classification systems. It is also important to distinguish ON from other eating disorders (e.g., symptoms and behaviors typical for ON may also be characteristic for anorexia nervosa). Finally, it is crucial to differentiate between HO and ON, to recognize where a care of one’s diet quality ends and a pathological obsession – potentially leading to suffering and health damage – begins [

26,

27], and to avoid overdiagnosis and stigmatization of all alternative healthy diets (including plant-based diets) [

26]. Nevertheless, the mere fact of

reducing meat for ethical reasons should not be a diagnostic criterion for ON [

28].

At the moment, despite many proposals for diagnostic criteria for ON, no uniform standard or consensus has been established [

27]. However, proposed criteria for ON usually include the following features:

obsessive focus on healthy eating (rigid rules and restrictions, excessive attention to the nutritional value of meals as well as the quality and purity of food) worsening everyday functioning;

emotional disorders (e.g., anxiety, fear) resulting from failure to follow the rigorous dietary rules imposed on oneself;

psychosocial problems in various areas of life (e.g., work- or school-related);

malnutrition and weight loss [

26,

27].

Selected psychometric tools for diagnosing ON are presented in

Table 1. The most used are ORTO-15 questionnaire and the Bratman Orthorexia Test (BOT) [

27].

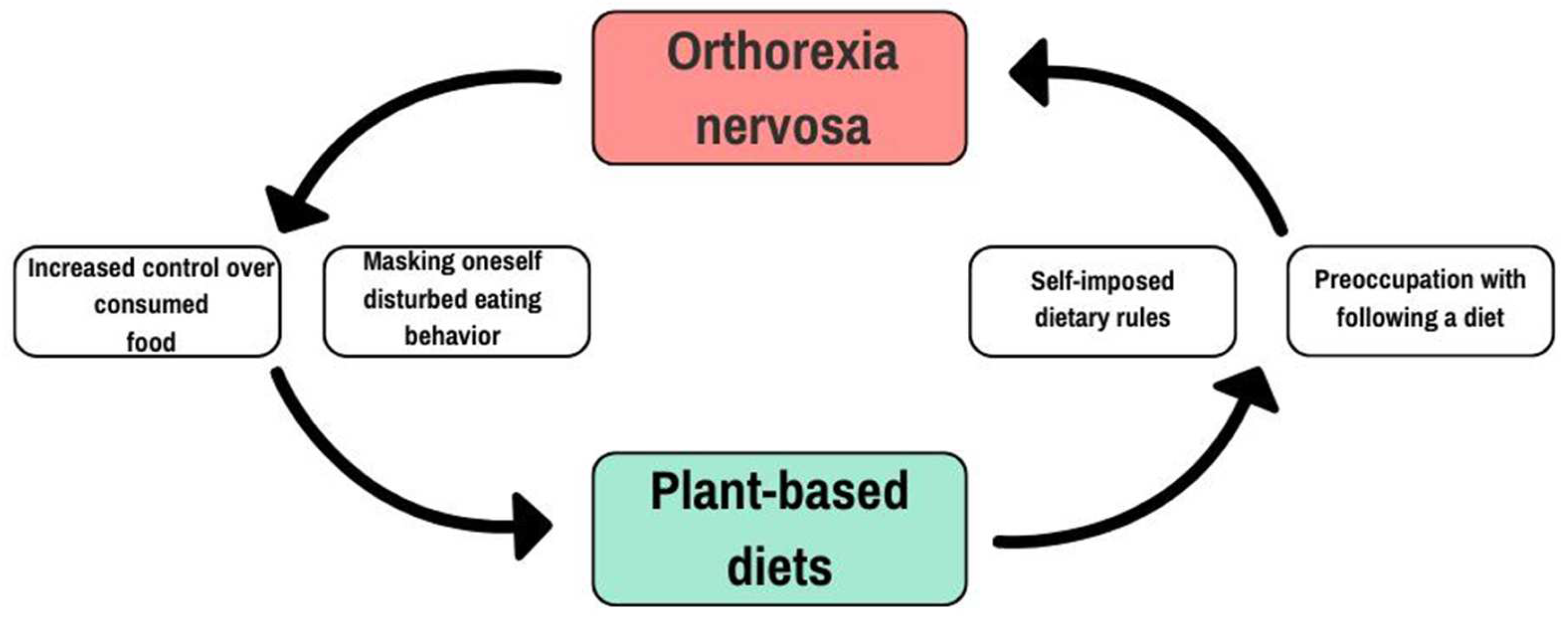

6. Two Sides of the Cycle

Half of patients with anorexia nervosa declare that they refuse to eat red meat because it is perceived as too caloric, distasteful or anxiety-provoking. On the other hand, problematic eating behaviors, developing after switching to a vegetarian diet, in a form of significant restrictions on the amount, frequency, or variety of food consumed, have also been observed. At the same time, 6-34% of adolescents and young adults in the general population developed an eating disorder after adopting a special diet [

40]. Other studies indicate that 50% of anorectic patients follow a vegetarian diet [

35], compared to 10% in the general population [

41]. It remains unclear whether vegetarianism increases the risk of developing eating disorders, or whether having an eating disorder increases the chances of choosing plant-based dietary pattern [

30]. It cannot be ruled out that the pathology is perpetuated in a vicious cycle, in which restriction begets restriction [

42] (

Figure 3).

6.1. Plant-Based Diets as a Cover for Orthorexia Nervosa

Currently, there is an increased prevalence of vegetarianism (from 1% to 9%), especially in developed countries [

35]. The reasons for choosing this dietary pattern vary depending on the study. One indicated that health/nutrition (37.5%) reason is the most common, followed by weight control (18.8%) and ethics towards animals (14.6%) [

43]. In the other one, the most common reasons were taste preferences (58.1%), followed by a healthier diet (19.4%) and weight control (9.6%) [

44].

Conscious eating is associated with long-term health benefits, but also with a sense of responsibility, which in some people can lead to an obsession with healthy eating, characterized by excessive control over food intake, forced behaviors and self-control [

45]. Some research suggest that use of the plant-based diets may be associated with a disturbed body image and complexes regarding body weight and figure, which do not correspond to the contemporary canons of beauty [

35]. Moreover, studies have shown that women who follow a vegetarian diet may be more likely to demonstrate disturbed eating attitudes and behaviors than women who follow an omnivore diet, as well as men. It has also been found that following certain diets or dietary rules, such as different types of vegetarian diets, is associated with orthorexic eating patterns [

13].

Many people with disturbed eating habits and using (currently or in the past) a vegetarian diet admit that they adopted it because they wanted to increase control over the consumed food. In a patient with eating disorders and being a vegetarian, there is a high probability that the diet is a way of restricting one’s food consumption as a part of the pathological eating behavior [

46]. Vegetarianism may be a widely accepted way to limit food intake to control or reduce body weight, while concealing pathological eating behaviors [

47]. Since plant-based diets are characterized by a high intake of products such as vegetables, whole grains, legumes and fruits, they have a positive effect on health, as they are high in fiber, bioactive compounds and micro- and macro-elements, and low in saturated fats and simple sugars [

48]. This affects the perception of plant-based diets as low-calorie and low-fat, which on the one hand is good for general health [

40], but on the other, may be a strategy for avoiding food to control body weigh [

42]. It has been noted that eating disorders occurred more frequently in people who declared using a vegetarian diet for this very purpose [

17].

With the right expertise and meal planning, there is no reason why vegetarian – including vegan – diet cannot be well-balanced and sufficient to meet the nutritional needs of any individual [

49]. However, a person with ON exhibits inflexible eating behaviors, ranging from a focus on eating organic or raw foods to a complete avoidance of all foods perceived as unhealthy, what can lead to a disturbed relationship with food and malnutrition [

35]. In one study, participants most frequently named plant-based foods (30%), organic/natural/non-GMO foods (18%), and protein foods (16%) as important components of “clean” diets [

50]. Furthermore, two-thirds of people with a history of eating disorders reported that their choice of vegetarianism was associated with their eating disorders, because it allowed them to reduce calorie intake and to increase their sense of control over consumed food [

46].

Through avoidance and ritualization – perceiving vegan foods as healthy – people with ON experience temporary relief from anxiety, while perpetuating intrusive thoughts about health and food [

23].

The higher prevalence of eating disorders in vegetarians suggests that plant-based diets may be used to justify avoidance of food and to mask restrictive eating patterns used for weight control [

13]. For a patient with an eating disorder, declaring being a vegetarian for – for instance – animal rights reasons seem more socially acceptable and less uncomfortable than explicitly disclosing weight loss as a motive [

42].

6.2. Plant-Based Diets as a Path to Orthorexia Nervosa

Although there is an increasing number of studies on vegetarianism, only few examined the relationship between the use of these dietary patterns and an increased tendency to orthorexia disorders [

13,

28,

30]. It has been suggested that vegetarianism may be a factor triggering and maintaining eating disorders, but the evidence supporting this thesis are ambiguous [

47,

51].

The results of studies assessing the incidence of ON among vegetarians are divergent [

28,

30]. Some indicate a significant link between the use of plant-based diets and this disorder [

28,

30,

52,

53], while others find no such association [

54,

55]. The discrepancy in results may be due to several reasons, including different definitions of types of vegetarianism or the use of different methods for diagnosing ON [

28] and their unadjustedness to plant-based diets users – for obvious reasons, dietary attitudes and behaviors of vegetarians differ from non-vegetarians, and this may be wrongly perceived as pathology [

38].

Missbach et al. [

52], in a sample of 1029 people, found that different vegetarian dietary patterns were associated with the occurrence of ON. Similarly, Dell’Osso et al. [

56], in a sample of 2130 people from the academic community of the University of Pisa, found that vegetarians showed a significantly higher rate of ON symptoms than people on a typical diet. Moreover, women obtaining higher ORTO-15 scores were characterized by a lower BMI, were more often underweight and were more often vegetarians [

56].

Reynolds et al. [

53] compared the tendency to ON between vegans, vegetarians (using lacto-, ovo-, and lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets, and different types of pseudovegetarian diets) and people who did not exclude any product groups. It was found that vegans and vegetarians had significantly more orthorexic tendencies than non-vegetarians. A particularly high incidence of ON was observed in the vegan group: in dietary vegans – 42.9%, and in lifestyle and dietary vegans – 30.8%, compared to 11.8% in omnivores. Furthermore, it was shown that people with greater orthorexic tendencies significantly more often chose food for weight control and ethical reasons than people with lesser orthorexic tendencies [

53].

Another important aspect is the fact that vegetarians are more likely to have greater nutritional knowledge and pay more attention to the quality and composition of the products they choose. In a systematic review, in 9 of 12 analyzed studies, lacto-ovo-vegetarians or vegans had a 4.5–16.4-point higher HEI-2010 (Healthy Eating Index 2010) score than non-vegetarians [

57]. Brytek-Matera et al. [

13] showed that vegans had greater knowledge of healthy eating compared to vegetarians excluding only meat from their diet and non-vegetarians.

Currently used methods for diagnosing ON may not be adapted to vegans and other vegetarians for several reasons. Inherently, these diets require some level of dietary restraint to ensure that unacceptable foods are not consumed. Questionnaires may not be able to distinguish between underlying factors behind the restrictions – whether it is dietary restraint (e.g., plant-based diet) or cognitive restraint (e.g., weight control). In addition, they are likely unable to identify dietary behaviors unique to vegetarians, such as monitoring meals composition when eating in public or reading food labels (

Table 2). Therefore, it seems necessary to design a specific screening tool to assess eating disorder symptoms in individuals who follow plant-based diets. A validated self-report tool dedicated to this group would provide clinicians and researchers with a rapid, inexpensive, and effective way to identify individuals who may require in-depth assessment of dietary habits or intervention [

47].

Recently, a method for diagnosing eating disorders dedicated to vegans and vegetarians – the Vegetarian Vegan Eating Disorder Screener (V-EDS) – was created. This is an 18-item self-report tool designed to assess eating disorders symptoms in vegetarians and vegans over the past 7 days. It was created based on the experience of vegetarians and vegans, the experience of people with a history of eating disorders, and the knowledge of psychologists and dietitians specializing in the field. The V-EDS was designed to distinguish the basic factors determining the increasing pathology of eating disorders (e.g., restricting food to affect body weight versus restricting food groups in vegetarian or vegan diets). The questionnaire is divided into two parts – the first one, consisting of 6 items, provides information on the respondent’s diet, while the second, 12-item part, refers to the respondent’s behaviors and attitudes and examines the presence of pathology towards eating disorders. Both are assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, and the higher the obtained score, the more severe eating disorder. The overall score of 18 is considered as the cut-off point for predicting clinical cases [

47,

58].

V-EDS has the potential to serve as an accessible tool for the initial screening and ongoing monitoring of eating disorder symptoms progression among vegetarians and vegans. However, future studies should aim to broaden the psychometric evaluation of the V-EDS by testing it with larger and more diverse populations, considering factors such as gender, age, cultural background, and history of eating disorders [

58].

7. Conclusions

Based on the available literature, an association between ON and plant-based diets can be observed. However, the lack of consensus on the definition of ON and its diagnosis, as well as the small number of studies involving people with a history of eating disorders who also stick to plant-based diets, makes it difficult to demonstrate a clear cause-effect relationship. Moreover, there is a possibility of misinterpreting results obtained by using existing diagnostic tools.

Studies suggest that vegetarian diets may be chosen as an attempt to cover up orthorexic behaviors, while dietary restrictions resulting from adopting these diets may potentially predispose to disturbances of eating habits. Thus, it is important for specialists (including dietitians) to pay attention to the motives for choosing such diet types (health aspects vs. weight control) and their patients’ general relationship with food. On the other hand, it is also necessary to create new and to adapt current methods for diagnosing ON, considering the lifestyle specific to vegetarians – especially vegans – to avoid overdiagnosis and stigmatization. More research is needed to determine where the boundary between HO and ON lies, and to explore how ON and plant-based diets are interrelated.

Author Contributions

P.S., K.W. – study design; P.S., K.W. – literature search; P.S., K.W., P.G. – manuscript preparation; P.G. – primary responsibility for the final content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jasiński M, Dubelt J, Cybula-Misiurek M, Jasińska E. Kult piękniej i szczupłej sylwetki a zagrożenia zdrowia młodzieży. In: Tatarczuk J, Zboina B, Dąbrowski P, editors. Zagrożenie życia i zdrowia człowieka. Wydawnictwo Naukowe NeuroCentrum; 2017:133-146.

- Kochman, D.; Jaszczak, M. Zaburzenia odżywiania się – częsty problem współczesnej młodzieży. 2021, 6, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padín, P.F.; González-Rodríguez, R.; Verde-Diego, C.; Vázquez-Pérez, R. Social media and eating disorder psychopathology: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology: J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge University Press. (n.d.). Clean eating. In Cambridge English Dictionary. [Retrieved February 27.02.2025 from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/clean-eating].

- Koven, N.; Abry, A. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Możdżonek, P.; Antosik, K. Creating of dietary trends in the media and their influence on the development of eating disorders. Nurs. Public Heal. 2017, 7, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertelli, T.; Carretier, E.; Loisel, A.; Moro, M.-R.; Blanchet, C. Vegetarianism and eating disorders: The subjective experience of healthcare professionals. Appetite 2023, 193, 107136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, G.; Kehoe, L.; Flynn, A.; Walton, J. Plant-based diets: a review of the definitions and nutritional role in the adult diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 81, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melina, V.; Craig, W.; Levin, S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinger, E.; Neuenschwander, M.; Koller, A.; Gojda, J.; Kühn, T.; Schwingshackl, L.; Barbaresko, J.; Schlesinger, S. Evidence of a vegan diet for health benefits and risks – an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational and clinical studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 9926–9936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeder, C.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A. Vegan nutrition: a preliminary guide for health professionals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 64, 670–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehér, A.; Gazdecki, M.; Véha, M.; Szakály, M.; Szakály, Z. A Comprehensive Review of the Benefits of and the Barriers to the Switch to a Plant-Based Diet. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brytek-Matera, A.; Czepczor-Bernat, K.; Jurzak, H.; Kornacka, M.; Kołodziejczyk, N. Strict health-oriented eating patterns (orthorexic eating behaviours) and their connection with a vegetarian and vegan diet. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2018, 24, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banna, J.C.; Panizza, C.E.; Boushey, C.J.; Delp, E.J.; Lim, E. Association between Cognitive Restraint, Uncontrolled Eating, Emotional Eating and BMI and the Amount of Food Wasted in Early Adolescent Girls. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brytek-Matera, A. Restrained Eating and Vegan, Vegetarian and Omnivore Dietary Intakes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss S, Hormes JM, Timko CA. Vegetarianism and eating disorders. In: Vegetarian and Plant-Based Diets in Health and Disease Prevention. Academic Press; 2017:51-69.

- Dittfeld, A.; Gwizdek, K.; Jagielski, P.; Brzęk, J.; Ziora, K. A Study on the relationship between orthorexia and vegetarianism using the BOT (Bratman Test for Orthorexia). Psychiatr. Polska 2017, 51, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthels, F.; Meyer, F.; Pietrowsky, R. Orthorexic and restrained eating behaviour in vegans, vegetarians, and individuals on a diet. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2018, 23, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis MJ, Comer LK. Vegetarianism, dietary restraint, and feminist identity. Eat Behav. 2006;7(2):91-104. [CrossRef]

- Şentürk, E.; Şentürk, B.G.; Erus, S.; Geniş, B.; Coşar, B. Dietary patterns and eating behaviors on the border between healthy and pathological orthorexia. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2022, 27, 3279–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depa, J.; Barrada, J.R.; Roncero, M. Are the Motives for Food Choices Different in Orthorexia Nervosa and Healthy Orthorexia? Nutrients 2019, 11, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Gkiouras, K.; Markaki, A.; Theodoridis, X.; Tsakiri, V.; Mavridis, P.; Dardavessis, T.; Chourdakis, M. Food addiction, orthorexia, and food-related stress among dietetics students. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2018, 23, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickgraf, H.F.; Barrada, J.R. Orthorexia nervosa vs. healthy orthorexia: relationships with disordered eating, eating behavior, and healthy lifestyle choices. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2021, 27, 1313–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakın, E.; Obeid, S.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Soufia, M.; Sawma, T.; Samaha, S.; Mhanna, M.; Azzi, R.; Mina, A.; Hallit, S. “In-between orthorexia” profile: the co-occurrence of pathological and healthy orthorexia among male and female non-clinical adolescents. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gortat, M.; Samardakiewicz, M.; Perzyński, A. Orthorexia nervosa – a distorted approach to healthy eating. Psychiatr. Polska 2021, 55, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horovitz, O.; Argyrides, M. Orthorexia and Orthorexia Nervosa: A Comprehensive Examination of Prevalence, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L.M.; Barrada, J.R.; Barthels, F.; Dunn, T.M.; Babeau, C.; Brytek-Matera, A.; Cena, H.; Cerolini, S.; Cho, H.-H.; Coimbra, M.; et al. A consensus document on definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2022, 27, 3695–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Manzaneque-Cañadillas, M.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; Fernández-Muñoz, J.J.; Prado-Laguna, M.d.C.; Brytek-Matera, A. Pathological Preoccupation with Healthy Eating (Orthorexia Nervosa) in a Spanish Sample with Vegetarian, Vegan, and Non-Vegetarian Dietary Patterns. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, S.; Timko, C.A.; Hormes, J.M. Confirmatory factor analysis of the EDE-Q in vegans and omnivores: Support for the brief three factor model. Eat. Behav. 2020, 39, 101447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.P.; Kulkarni, J.; Sharp, G. Disordered eating and the meat-avoidance spectrum: a systematic review and clinical implications. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2022, 27, 2347–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małachowska, A.; Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gębski, J. Polish Adaptation of the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ): The Role of Eating Style in Explaining Food Intake—A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Syurina, E.V.; Donini, L.M. Shedding light upon various tools to assess orthorexia nervosa: a critical literature review with a systematic search. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2019, 24, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, N.A.; Worthington, A.; Li, L.; Conner, T.S.; Bermingham, E.N.; Knowles, S.O.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Hannaford, R.; Braakhuis, A. Adherence and eating experiences differ between participants following a flexitarian diet including red meat or a vegetarian diet including plant-based meat alternatives: findings from a 10-week randomised dietary intervention trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1174726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Ayhan, N.Y.; Sarıyer, E.T.; Çolak, H.; Çevik, E. The Effect of Bigorexia Nervosa on Eating Attitudes and Physical Activity: A Study on University Students. Int. J. Clin. Pr. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalika, E.; Egan, H.; Mantzios, M. Exploring the role of mindful eating and self-compassion on eating behaviours and orthorexia in people following a vegan diet. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2022, 27, 2641–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styk, W.; Gortat, M.; Samardakiewicz-Kirol, E.; Zmorzynski, S.; Samardakiewicz, M. Measuring Pathological and Nonpathological Orthorexic Behavior: Validation of the Teruel Orthorexia Scale (TOS) among Polish Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albery, I.P.; Shove, E.; Bartlett, G.; Frings, D.; Spada, M.M. Individual differences in selective attentional bias for healthy and unhealthy food-related stimuli and social identity as a vegan/vegetarian dissociate “healthy” and “unhealthy” orthorexia nervosa. Appetite 2022, 178, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.P.; Kulkarni, J.; Sharp, G. The 26-Item Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26): Psychometric Properties and Factor Structure in Vegetarians and Vegans. Nutrients 2023, 15, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiss, S.; Coffino, J.A.; Hormes, J.M. What does the ORTO-15 measure? Assessing the construct validity of a common orthorexia nervosa questionnaire in a meat avoiding sample. Appetite 2018, 135, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorard, G.; Mathieu, S. Vegetarian and omnivorous diets: A cross-sectional study of motivation, eating disorders, and body shape perception. Appetite 2020, 156, 104972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, M.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Nowak, J.K.; Stachowska, E. Global and local diet popularity rankings, their secular trends, and seasonal variation in Google Trends data. Nutrition 2020, 79-80, 110759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergentanis, T.N.; Chelmi, M.-E.; Liampas, A.; Yfanti, C.-M.; Panagouli, E.; Vlachopapadopoulou, E.; Michalacos, S.; Bacopoulou, F.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsitsika, A. Vegetarian Diets and Eating Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Children 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Klopp, S.; Heiss, C.J.; Smith, H.S. Self-reported vegetarianism may be a marker for college women at risk for disordered eating. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 745–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baş, M.; Karabudak, E.; Kiziltan, G. Vegetarianism and eating disorders: association between eating attitudes and other psychological factors among Turkish adolescents. Appetite 2005, 44, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Syurina, E.V.; Muftugil-Yalcin, S.; Cesuroglu, T. "Keep Yourself Alive": From Healthy Eating to Progression to Orthorexia Nervosa A Mixed Methods Study among Young Women in the Netherlands. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2020, 59, 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paslakis, G.; Richardson, C.; Nöhre, M.; Brähler, E.; Holzapfel, C.; Hilbert, A.; de Zwaan, M. Author Correction: Prevalence and psychopathology of vegetarians and vegans – Results from a representative survey in Germany. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.P.; Chen, Z.; Song, R.; Le, J.; Fielding, J.; Sharp, G. Development and preliminary validation of a novel eating disorder screening tool for vegetarians and vegans: the V-EDS. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwioździk, W.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Całyniuk, B.; Helisz, P.; Grajek, M.; Głogowska-Ligus, J. Traditional, Vegetarian, or Low FODMAP Diets and Their Relation to Symptoms of Eating Disorders: A Cross-Sectional Study among Young Women in Poland. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, S.J.; Brown, A.; Rowley, J.; Elliott-Archer, J. Veganism and eating disorders: assessment and management considerations. Bjpsych Bull. 2021, 46, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambwani, S.; Shippe, M.; Gao, Z.; Austin, S.B. Is #cleaneating a healthy or harmful dietary strategy? Perceptions of clean eating and associations with disordered eating among young adults. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahler, J.; Hermann, A.; Walter, B.; Stark, R. Orthorexia nervosa: A behavioral complex or a psychological condition? J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missbach, B.; Hinterbuchinger, B.; Dreiseitl, V.; Zellhofer, S.; Kurz, C.; König, J. When Eating Right, Is Measured Wrong! A Validation and Critical Examination of the ORTO-15 Questionnaire in German. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0135772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R.; McGowan, A.; Smith, S.; Rawstorne, P. Vegan and vegetarian males and females have higher orthorexic traits than omnivores, and are motivated in their food choice by factors including ethics and weight control. Nutr. Heal. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T.M.; Gibbs, J.; Whitney, N.; Starosta, A. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is less than 1 %: data from a US sample. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2016, 22, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiçekoğlu, P.; Tunçay, G.Y. A Comparison of Eating Attitudes Between Vegans/Vegetarians and Nonvegans/Nonvegetarians in Terms of Orthorexia Nervosa. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Abelli, M.; Carpita, B.; Massimetti, G.; Pini, S.; Rivetti, L.; Gorrasi, F.; Tognetti, R.; Ricca, V.; Carmassi, C. Orthorexia nervosa in a sample of Italian university population. Riv. Psichiatr. 2016, 51, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, H.W.; Vadiveloo, M.K. Diet quality of vegetarian diets compared with nonvegetarian diets: a systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, C.P.; Chen, Z.; Fielding, J.; Sharp, G. Preliminary identification of clinical cut-off of the vegetarian vegan eating disorder screener (V-EDS) in a community and self-reported clinical sample of vegetarians and vegans. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).