1. Introduction

In modern digital infrastructure, internet portals play a crucial role in facilitating economic, educational, recreational, and political activities. However, as the reliance on these platforms increases, so does the risk of security threats, including unauthorized access, data breaches, and service disruptions. One of the primary attack vectors involves manipulating web requests, where adversaries masquerade as legitimate users to exploit vulnerabilities. Consequently, the detection and mitigation of malicious web requests have become fundamental aspects of web security.

To counter such threats, various security mechanisms, including Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) and blacklisting techniques, have been deployed. While these methods offer some level of protection, they remain ineffective against zero-day attacks—novel exploits that lack predefined security signatures [

1]. The primary challenge associated with zero-day attacks lies in their unpredictability, as they introduce previously unseen patterns that traditional rule-based detection systems fail to recognize. Addressing these challenges through deep learning-based anomaly detection presents a promising approach, leveraging neural networks to autonomously identify deviations indicative of malicious activity.

Conventional methods for preventing web-based attacks, such as WAFs [

2] and blacklisting, exhibit several limitations. For instance, maintaining a blacklist of prohibited keywords within web requests is both time-consuming and insufficient in addressing evolving attack patterns. Moreover, none of these existing approaches are capable of detecting zero-day attacks, as the strategies and obfuscation techniques employed in these attacks remain unknown. Recent advancements in machine learning and deep learning have demonstrated significant potential in enhancing security through intelligent threat identification, making these techniques highly relevant for modern cyber defense systems.

A critical advantage of anomaly detection models is that they do not require prior exposure to zero-day attacks to effectively detect them. In this study, an ensemble model is proposed that integrates multiple sub-models designed to detect zero-day attacks. Given that the patterns of zero-day attacks are inherently unknown, the model is trained exclusively on normal web request data. By learning the distribution of normal web traffic, the model becomes proficient in identifying deviations, thereby flagging both known and previously unseen attacks as anomalous. This approach ensures that malicious requests, whether originating from known attack types or zero-day exploits, are effectively classified as security threats.

To evaluate the proposed system, various web attacks such as SQL Injection (SQLi), Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), and Buffer Overflow [

3] are treated as zero-day attacks within the dataset. The model classifies any request with an anomaly score exceeding a predefined threshold as a potential zero-day attack. While the proposed approach does not explicitly categorize different types of attacks, it demonstrates the capability to reliably detect anomalous activities, ensuring a high level of security against emerging threats. The primary objective of this model is to simultaneously address both known and zero-day attacks while maintaining a high detection rate and minimizing false positives.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the foundational concepts and research background.

Section 3 provides a review of existing literature on web attack detection. The methodology and architectural design of the proposed model are discussed in

Section 4, followed by a performance evaluation in

Section 5.

Section 6 elaborates on the broader implications of the findings, and

Section 7 concludes the paper with final remarks.

The key contributions of this research are as follows:

Ensemble-Based Anomaly Detection: The proposed model integrates LSTM, GRU, and stacked autoencoders to detect malicious web requests. This ensemble structure enables the model to effectively learn normal request patterns while enhancing its robustness against unknown attack strategies.

Zero-Day Attack Detection Without Labeled Anomalous Data: Unlike conventional detection methods that require labeled datasets containing both normal and malicious samples, the proposed model is trained exclusively on normal web requests. This approach enables it to detect both known and zero-day attacks by identifying deviations from learned normal behaviors.

Advanced Tokenization and Feature Mapping: A novel tokenization strategy is introduced, classifying tokens based on character composition (e.g., numeric, lowercase, uppercase, special characters). This method reduces input dimensionality, enhances pattern consistency, and improves the model’s ability to distinguish between benign and malicious activities.

Comprehensive Performance Evaluation: The effectiveness of the proposed model is assessed using multiple performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, specificity, F1 score, false positive rate and also consumed time for training and testing phases. The results demonstrate that the ensemble model consistently outperforms individual sub-models and previous approaches, achieving a higher detection rate with a significantly lower false positive rate.

By addressing the limitations of traditional detection systems and leveraging anomaly detection through deep learning, this research contributes to advancing cybersecurity measures against evolving web-based threats.

2. Background

Due to the increasing reliance on internet-based services, web attacks pose significant threats to user privacy and can severely disrupt web server operations, affecting users on a global scale. Among these threats, zero-day (previously unknown) attacks are particularly concerning, as they can lead to privacy breaches and denial of service, impacting all users of a targeted website [

4]. Machine learning-based approaches for web attack mitigation typically consist of two key phases: training and detection. During the training phase, the model learns from patterns of normal web requests, while in the detection phase, it utilizes this learned knowledge to identify and mitigate potential web attacks [

5].

Web attack countermeasures can generally be categorized into three primary approaches: (1) supervised, (2) unsupervised, and (3) semi-supervised learning. The supervised approach is primarily designed to detect known attacks and is commonly implemented in signature-based systems such as Web Application Firewalls (WAFs). These models rely on labeled datasets containing both historical attack patterns and normal requests, making them highly effective against previously documented threats. However, their reliance on predefined signatures renders them ineffective against zero-day attacks, as these attacks introduce novel patterns that are not represented in the training dataset [

6].

The unsupervised approach, on the other hand, employs anomaly detection techniques to distinguish between normal system activities and anomalies. Unlike supervised methods, this approach does not rely on historical attack patterns, allowing it to identify previously unseen zero-day attacks [

6,

7]. By modeling the expected behavior of normal web traffic, anomaly detection-based methods can effectively flag deviations indicative of malicious activity, making them particularly suitable for dynamic and evolving attack landscapes.

The semi-supervised approach, which lies between supervised and unsupervised methods, leverages normal web request data to train the model. This approach focuses exclusively on learning the characteristics of legitimate requests, enabling the model to differentiate between normal and anomalous activities. Since it involves training on only one category of data—normal requests—it eliminates the need for labeled attack samples while still allowing for anomaly detection in the detection phase [

6].

In this research, an unsupervised approach is employed to address the challenge of detecting zero-day attacks, which lack predefined signatures and attack patterns. By learning the distribution of normal web requests, the proposed model can effectively identify requests that deviate from the established normal behavior, thereby flagging them as potential zero-day attacks. This approach enhances the system’s ability to detect novel and previously unknown threats, making it a robust solution for mitigating modern web security risks.

3. Related Work

Numerous methods and models have been proposed to counter web attacks, including zero-day attacks. Models by researchers like Pu, G. et al. [

6], Ingham K. L. et al. [

8], Sivri, T.T. et al. [

9], Jung et al. [

10] Vartouni, A. M. et al. [

11], Ariu, D. et al. [

12], Liang, J. et al. [

13], Kuang, X. et al. [

14], Tang, R. et al. [

15], Indrasiri, P. L. et al. [

16], Gong et al. [

17], Tekerek et al. [

18], Jemal, Ines, et al. [

19], Alaoui, Rokia Lamrani [

20], Mohamed, S.M. and Rohaim, M.A. [

21], Shahid, Waleed Bin, et al. [

22], Moarref, N., and Sandıkkaya, M. T [

23] are notable.

The model by Pu, G. et al. [

6] introduces an unsupervised anomaly detection method that combines Sub-Space Clustering (SSC) and One Class Support Vector Machine (OCSVM). This approach aims at detecting cyber intrusions without prior knowledge of the attacks, making it particularly useful for identifying unknown or zero-day attacks.

The model by K. L. et al. [

8] proposes a method for detecting web attacks by focusing on deep learning techniques, specifically utilizing Transformer models. This approach signifies a significant advancement in web security, offering a more dynamic and intelligent system for detecting and mitigating web-based attacks.

Sivri, T.T. et al. [

9] used various machine learning and deep learning models. For example, a hybrid model that uses character-level representations to classify HTTP requests as normal or malicious. The study employed models such as XGBoost, LightGBM, LSTM, CNN. The upsampling techniques have been used to balance the dataset, which are able to improve classification metrics. As a result, the LSTM model achieved the best accuracy and F1 score, while LightGBM performed better in computation time. This work shows the importance of balancing in real-time web intrusion detection systems.

Jung et al. [

10] used a novel approach named Payload Feature-Based Transfer Learning (PF-TL) to cope with insufficient training data in intrusion detection systems. Their method leverages knowledge transfer from a labeled source domain to an unlabeled target domain by extracting features from both the header and payload of network traffic. The technique they use is a hybrid feature extraction, combining signature-based and text vectorization methods, to enhance the representation of attack patterns.

The model by Vartouni, A. M. et al. [

11] uses a deep neural network-based method for feature learning and isolation forest for classification to identify malicious requests. It employs an n-gram model, which represents overlapping subsets of n characters from the data.

The Ariu, D. et al. [

12] model is an intrusion detection system that represents payloads as byte sequences, analyzed using Hidden Markov Models (HMM). This proposed algorithm ensures the analytical power of n-gram analysis while overcoming its computational complexity, using HMM for feature extraction. However, HMM models are less effective when the sequence length is not appropriate, leading to poorer performance in processing complex requests.

In the Liang, J. et al. [

13] model, the approach involves first training two Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) with Complex Recurrent Units (LSTM or GRU units) to learn normal request patterns solely from unsupervised normal requests. Then, a supervised neural network classifier is trained, taking the output of the RNN as input to categorize normal and abnormal requests.

Kuang, X. et al. [

14] employ deep learning concepts to design a model named DeepWaf, a combination of LSTM and CNN deep neural networks, achieving satisfactory results in detecting web attacks.

In the Tang, R. et al. [

15] model, each word in an HTTP request (except for low-value words like ’and’, ’or’, etc.) is tokenized. Words and tokens are mapped to each other through TokenIDs. The tokenized request is then encoded and decoded using a Short-Term Memory architecture; if the decoded value matches the pre-encoded tokenized value, the request is benign, otherwise, it’s malicious. The model primarily targets zero-day attacks, leaving known attack detection to WAF and addressing zero-day attacks through the Zero-Wall model. A limitation of this approach is that new benign requests with different patterns might be incorrectly flagged as malicious and subjected to further scrutiny in the Zero-Wall model before being identified as benign.

In the Indrasiri, P. L. et al. [

16] model, seven classification algorithms, one clustering algorithm, two ensemble methods, and two large standard datasets with 73,575 and 100,000 URLs were used. Two testing modes (percentage split, K-Fold cross-validation) were employed for experiments and predictions. An ensemble model named ERG-SVC was proposed, using features selected by various feature selection methods.

The model by Gong et al. [

17] proposes a method to improve web attack detection by incorporating model uncertainty into deep learning (DL) models, specifically focusing on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). The method aims to address the problem of annotation errors in training data. Annotation errors are common in web attack datasets due to the vast and varied nature of web traffic, making correct labeling challenging.

The model by Tekerek et al. [

18] introduces a novel approach for detecting web-based attacks using a deep learning architecture centered on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Focused on anomaly-based detection, this method preprocesses HTTP request data, particularly URLs and payloads, to identify unusual patterns indicative of potential threats.

The model by Jemal, Ines, et al. [

19] presents a smart web application firewall (SWAF) based on a convolutional neural network. Using 5-fold cross-validation method. The CNN is characterized by a specific architecture, it can learn the data on a large scale and automatically extract and select the features engineering. It consists of five layers.

The model by Alaoui, Rokia Lamrani [

20], proposes an approach based on Word2vec embedding and a stacked generalization ensemble model for LSTMs to detect malicious HTTP web requests.

Mohamed, S.M. and Rohaim, M.A. [

21] propose a deep learning-based multi-class intrusion detection system that classifies different types of web attacks using algorithms like LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CNN, and RNN. Automatic extraction and classification of features from HTTP traffic are their main approaches which overcome limitations related to traditional feature engineering.

The model by Shahid, Waleed Bin, et al. [

22] proposes a framework based on an enhanced hybrid approach where Deep Learning model is nested with a Cookie Analysis Engine for web attacks detection, mitigation and attacker profiling in real time.

The model by Moarref, N., and Sandıkkaya, M. T [

23] try to focuse on enhancing web attack detection via a character-level multichannel multilayer dilated convolutional neural network, processes HTTP request texts at the character level and extracting relevant features. The model combines multichannel dilated convolutional blocks with varying kernel sizes to capture diverse temporal relationships and dependencies among characters.

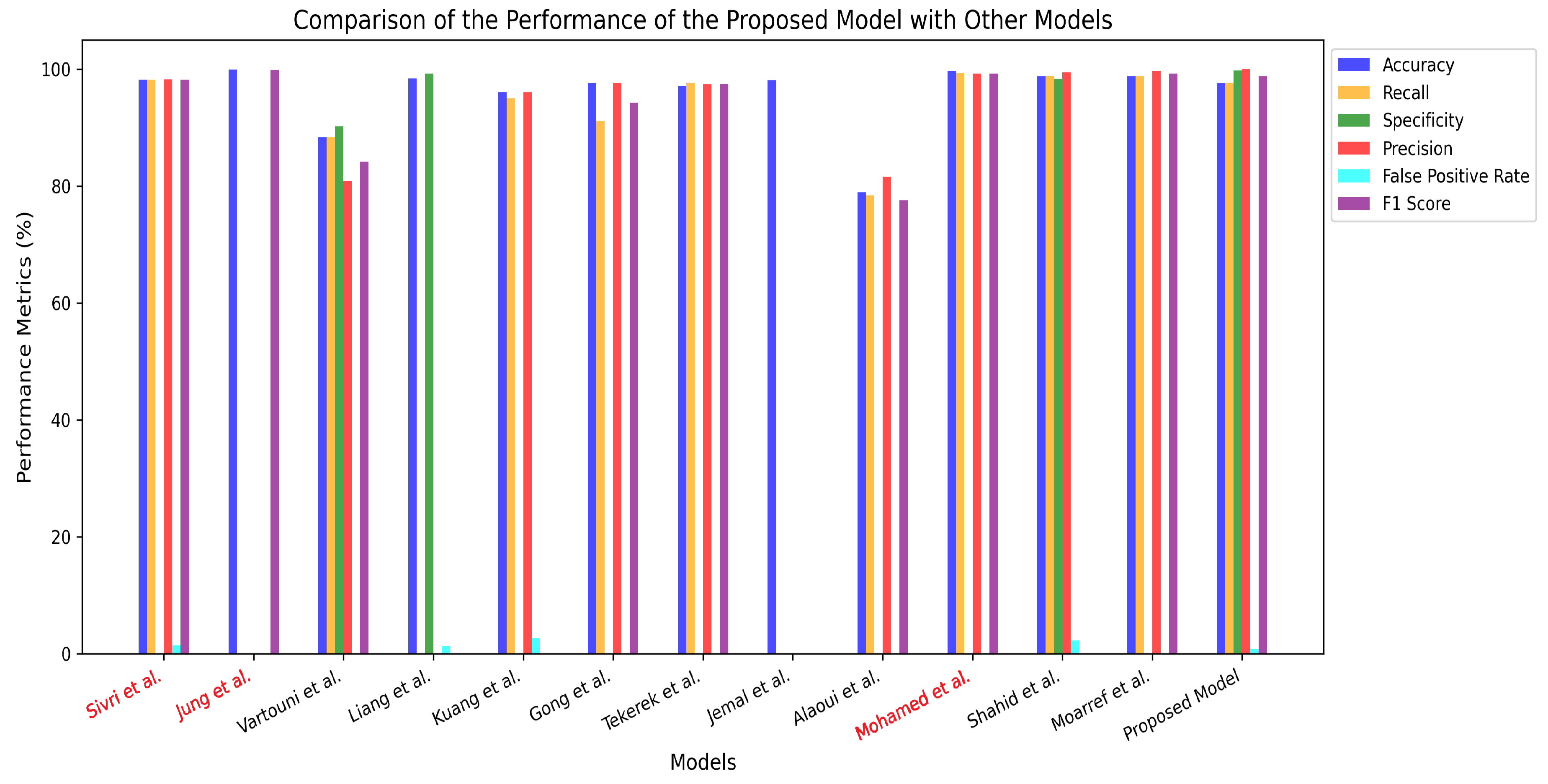

A key limitation of the related works is the omission of one of the most critical evaluation metrics: the False Positive Rate (FPR), which quantifies the proportion of normal web requests misclassified as malicious. This metric is essential for assessing the model’s capability to accurately encode and decode normal requests, ensuring minimal disruption to legitimate traffic. In contrast, our proposed model demonstrates superior performance, achieving the lowest False Positive Rate of 0.2%, which is even lower than the values reported in prior studies that included this metric in their evaluation.

4. Proposed Model

This section presents the proposed model for detecting zero-day web attacks. The detection process begins with the pre-processing of web requests through tokenization techniques, ensuring standardized input representation. These processed requests are then fed into an ensemble of relatively simple one-class classifiers designed to distinguish between normal and malicious web traffic. The effectiveness of the proposed model is assessed during the detection phase, focusing on its capability to identify and mitigate advanced security threats.

4.1. Architecture

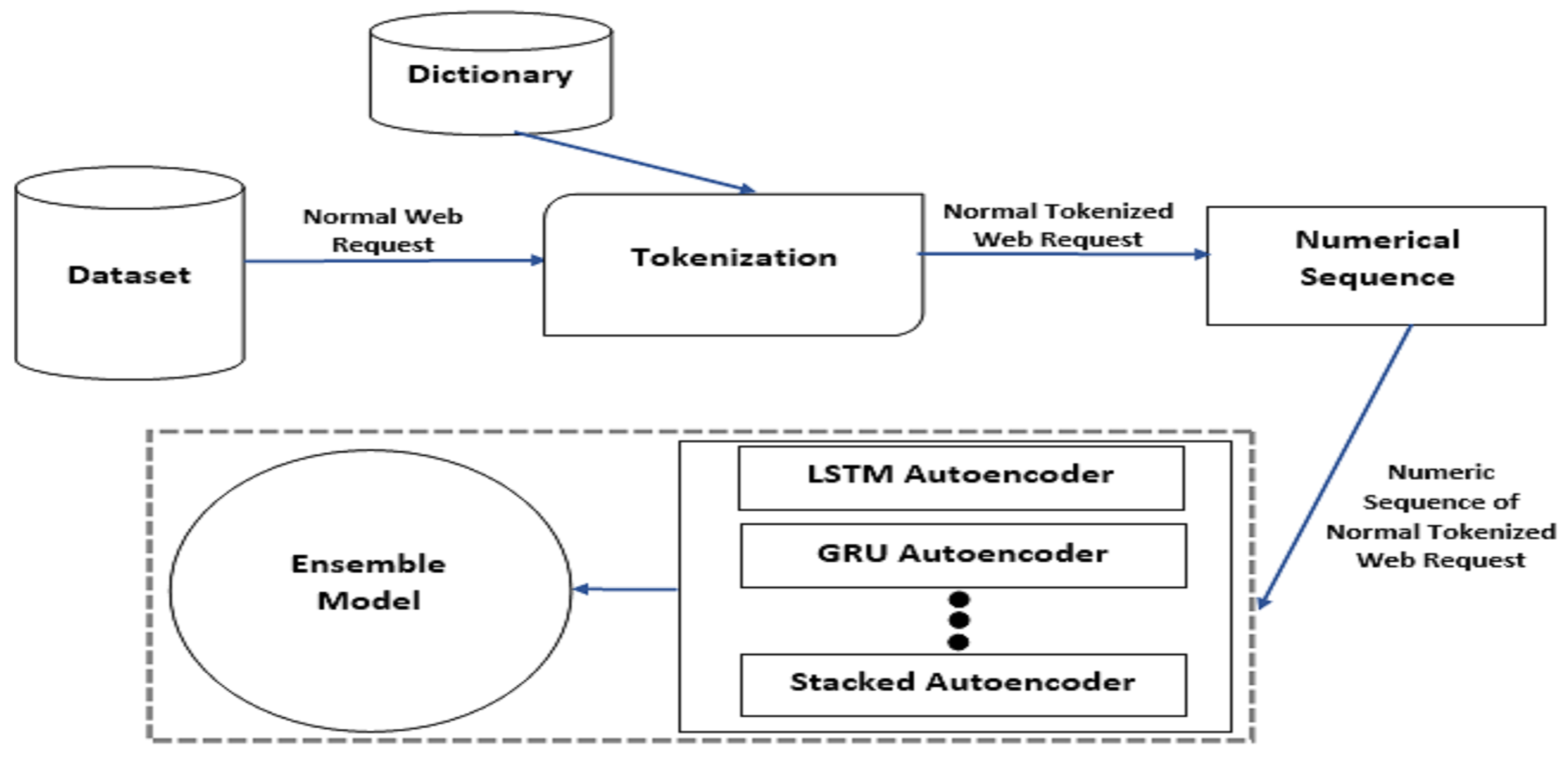

The proposed model comprises multiple components, each serving a distinct role in the detection process. These components collaboratively predict whether an incoming web request is benign or malicious. The overall model architecture is depicted in

Figure 1 for the training phase and

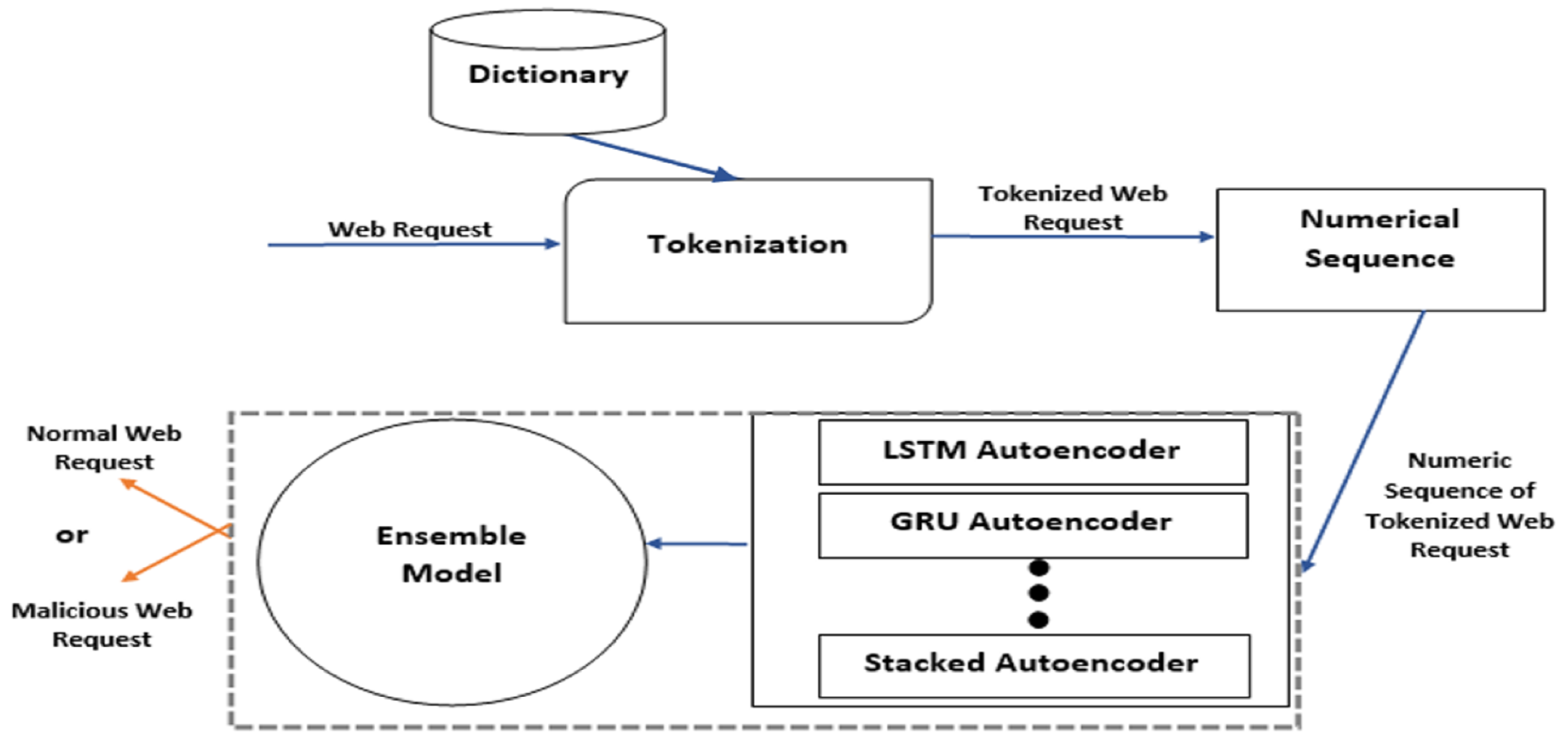

Figure 2 for the testing phase.

During the training phase, the model is exclusively trained on normal web requests to establish a baseline pattern of legitimate traffic. In this phase, the model has full access to the training dataset, allowing it to learn the distribution of normal request patterns [

24]. Conversely, in the testing phase, both normal and malicious web requests are input into the model for evaluation. This enables the model to assess its ability to generalize and detect deviations indicative of potential zero-day attacks.

4.1.1. Tokenization

A key innovation of the proposed model is the introduction of a novel tokenization technique for web requests, applied at the word level to both normal and malicious inputs [

25]. Due to the inherent variability in the length and structure of web requests, this method addresses the challenges associated with training neural network-based models for web security. Specifically, the model leverages anomaly detection principles to effectively distinguish between legitimate and anomalous web traffic [

26].

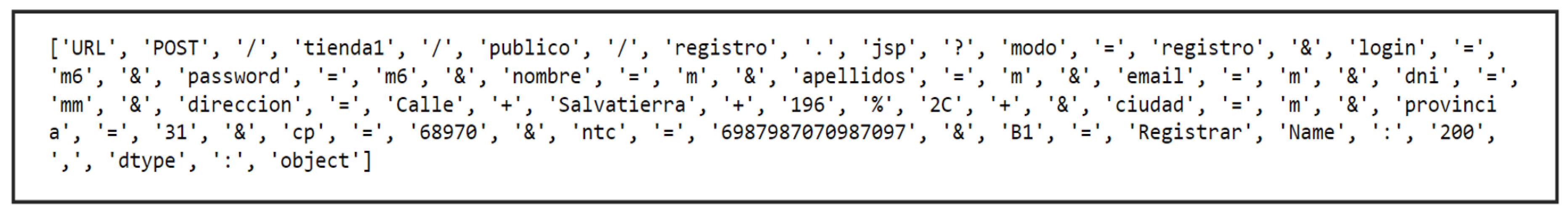

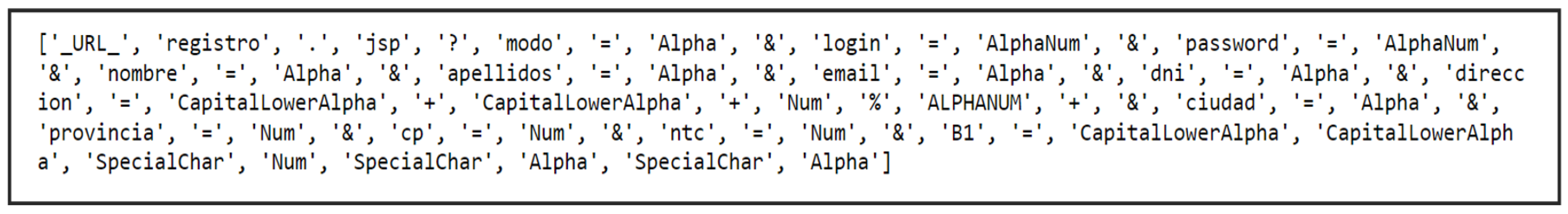

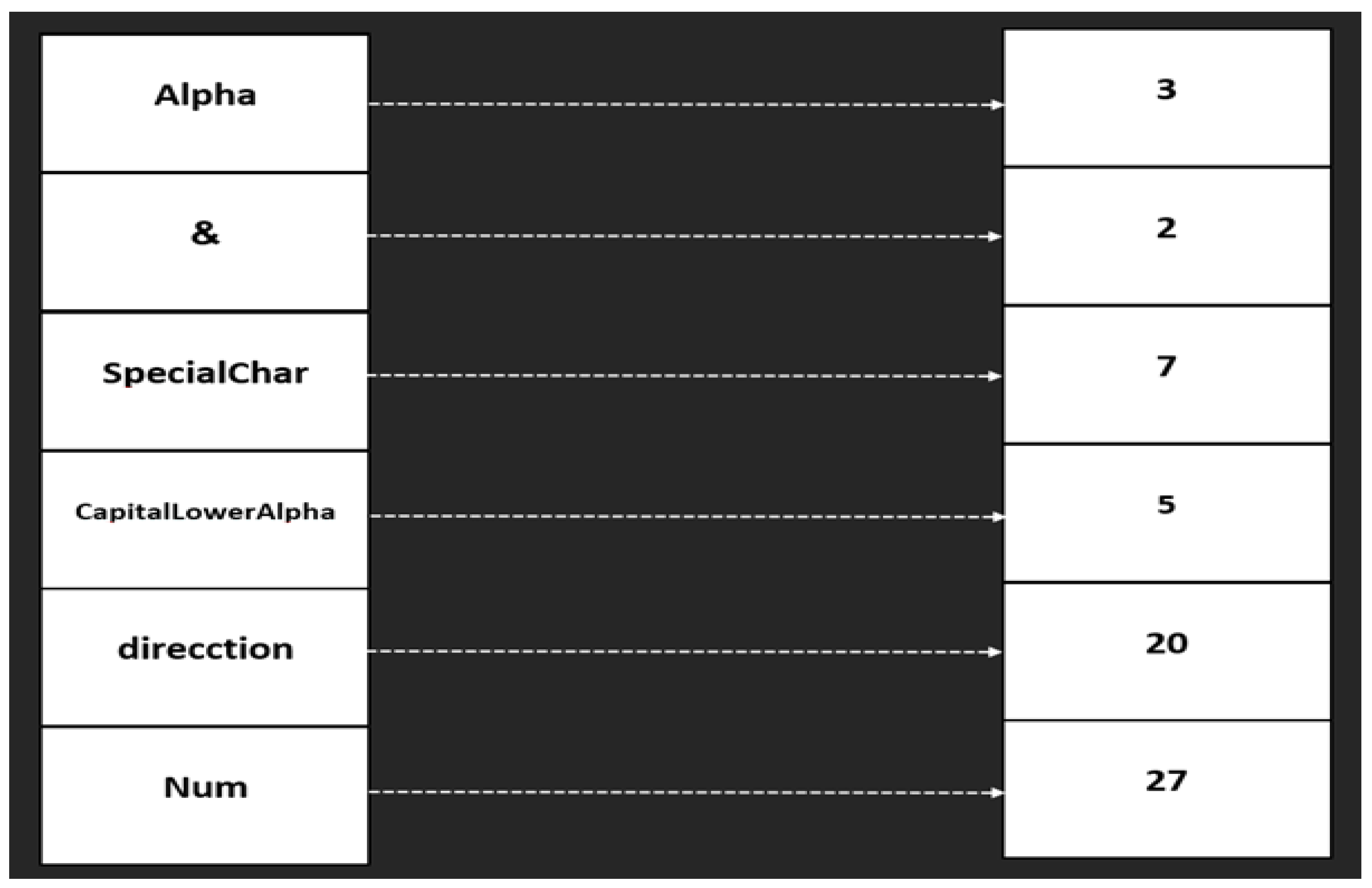

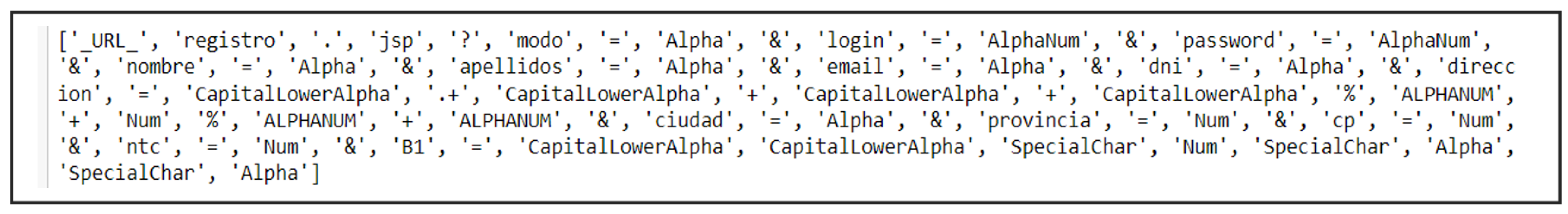

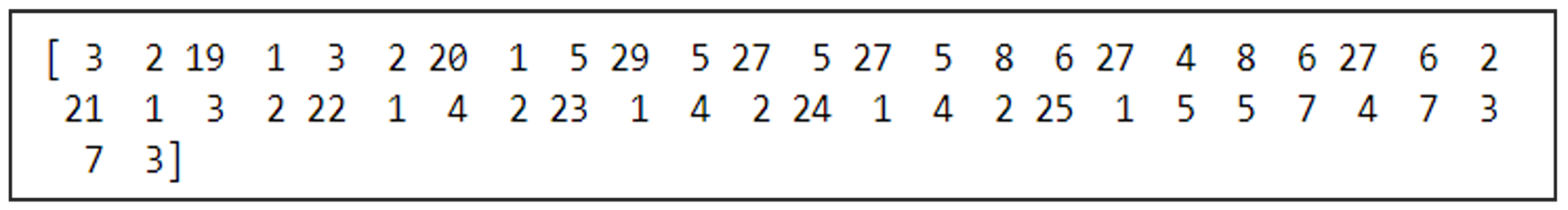

To ensure consistent data representation, the pre-processing pipeline standardizes normal web requests through a dictionary-based tokenization approach [

13]. This process involves segmenting each request at the word level using tools such as Python’s WordPunctTokenizer [

27]. The resulting structured pattern is subsequently utilized as the input for training the ensemble model. The overall tokenization and data processing workflow is depicted in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, illustrating how the extracted token sequences contribute to model learning and detection accuracy.

4.1.2. Dictionary

A predefined dictionary is utilized to categorize each character into distinct classes, facilitating structured tokenization. The dictionary includes categories such as

Alpha,

AlphaNum,

CapitalAlpha, and

SpecialChar, among others. For instance, in

Figure 4, the token "login" is assigned the value "m6," which represents a combination of letters and numbers, classifying it under

AlphaNum according to the predefined dictionary. Similarly, the word "Register," which begins with a capital letter, falls under the

CapitalLowerAlpha category. These classifications enhance the accuracy of tokenization and facilitate the interpretation of web requests within the proposed model.

The significance of the tokenization approach in this model is twofold:

Data volume reduction: The tokenization process optimizes data representation, reducing the complexity and size of input data, thereby improving computational efficiency.

Pattern identification for anomaly detection: By establishing a structured pattern for normal web requests, the tokenization method enhances the model’s ability to differentiate between legitimate and anomalous activities, ensuring higher accuracy in detecting malicious web requests.

4.1.3. Numerical Sequence

Following the tokenization of web requests on a word-by-word basis, each token must be mapped to a corresponding numerical representation, as neural networks operate on numerical data rather than raw text. This transformation is a critical step, as the varying range of input features necessitates data scaling before being processed by the model [

28]. The tokenized text is converted into a structured numerical format suitable for input into the neural network.

Figure 5 illustrates the mapping process, where individual words are assigned numerical values, facilitating seamless integration into the model.

To accommodate variations in the length of numerical sequences representing web requests, a padding mechanism is implemented. This ensures that all input sequences maintain a uniform length, preventing inconsistencies in model processing. Padding aligns shorter sequences with longer ones by appending neutral values, thereby standardizing input dimensions.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 depict the complete process, demonstrating how an entire web request is transformed into a numerical sequence. This step enhances the model’s ability to analyze and recognize patterns within the data, ultimately improving detection accuracy and performance.

4.1.4. Ensemble Model

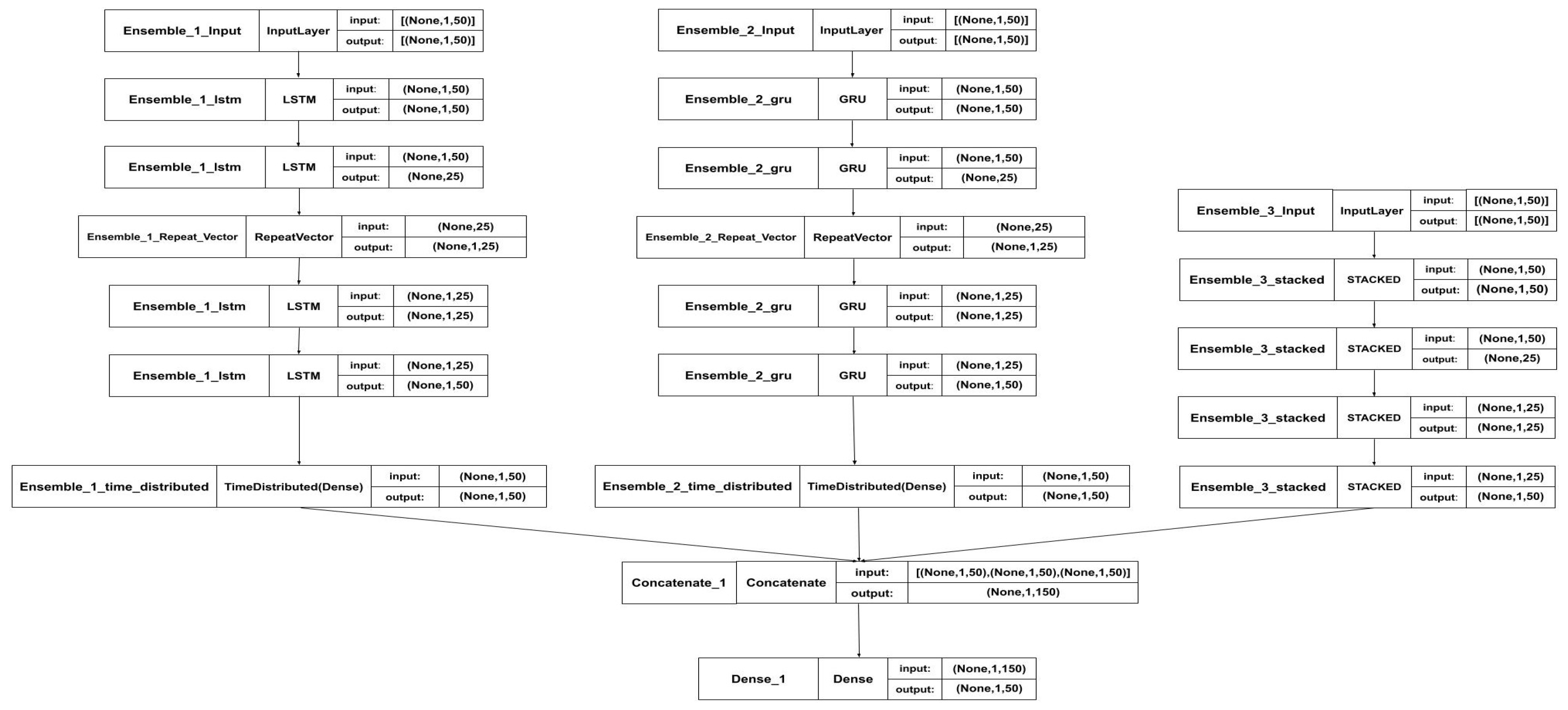

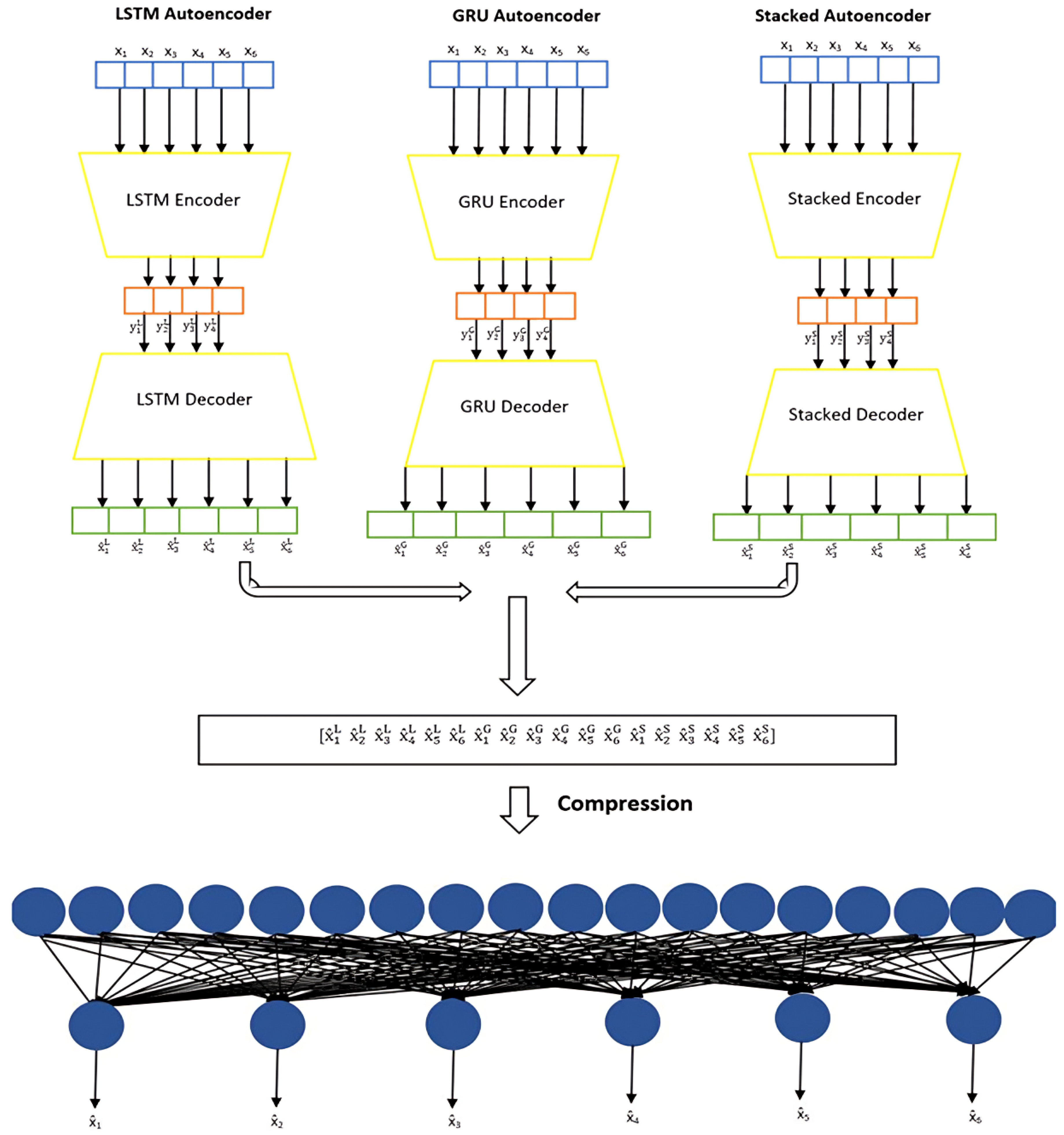

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the proposed ensemble model consists of three sub-models: an LSTM autoencoder, a GRU autoencoder, and a stacked autoencoder. The initial phase of the proposed approach involves selecting appropriate sub-models for training and detection, ensuring an optimal balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. The primary objective is to design multiple lightweight sub-models that, when combined, enhance the overall detection capability while maintaining a low false positive rate.

To achieve this, various neural network architectures were evaluated. Experimental results demonstrated that employing Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and stacked autoencoders in an ensemble configuration enhances data processing efficiency and improves the accurate identification of both known and zero-day web attacks. The outputs of these sub-models are concatenated and further processed through a dense layer for feature reduction, optimizing the final classification process.

Autoencoders are widely utilized for dimensionality reduction and feature extraction. These models consist of an encoder and a decoder, both comprising multiple layers, which collectively transform an input sequence of symbols (words) into a continuous latent representation. The decoder then reconstructs the original input from this representation, preserving critical features while filtering out noise [

29,

30]. This reconstruction-based learning approach enables autoencoders to effectively capture underlying patterns in web requests, further improving the robustness of the detection framework.

The encoded sequences of the original input data, denoted as:

are obtained through specific encoding functions corresponding to each autoencoder type. The encoding transformations for the LSTM, GRU, and stacked autoencoders are formally defined as follows:

These equations represent the encoding processes, wherein the input sequence x is mapped to its corresponding latent representation, effectively capturing essential features required for the detection process.

For each type of autoencoder, the encoded representations are structured as follows:

for the LSTM autoencoder,

for the GRU autoencoder, and

for the stacked autoencoder.

The output of the encoder serves as the input to the decoder, which reconstructs the original input sequence from the encoded representation. The reconstruction process is defined as follows:

where , , and denote the decoding functions for the LSTM, GRU, and stacked autoencoders, respectively.

The primary objective of the decoding process is to validate the quality and representativeness of the extracted features. The outputs from all three autoencoders are subsequently concatenated to form a unified feature representation, denoted as

:

To maintain consistency with the original input dimensions and optimize computational efficiency, a compression operation is applied to

. This step ensures that the number of features in the final output aligns with that of the original input data, enabling effective processing and interpretation of web requests within the proposed model:

This final transformation refines the extracted feature representations, ensuring that the model retains only the most relevant and informative aspects of the input data while discarding redundant or insignificant components. By optimizing the structure of the encoded sequences, the model enhances its capacity for accurate detection and classification of web requests.

5. Evaluation and Results

This section presents the evaluation of the proposed model and its sub-models based on multiple performance metrics, including accuracy, detection rate, sensitivity, precision, and false positive rate. To assess the effectiveness of the proposed approach, a threshold-based evaluation is conducted using the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), which quantifies the difference between the reconstructed request and the original input (prior to encoding).

In machine learning, MAE is a widely used metric for measuring the absolute difference between predicted values and their actual counterparts. It is computed by averaging the absolute errors across all predictions. MAE was selected as the primary evaluation metric due to its interpretability, robustness, and alignment with the model’s objectives. Specifically, MAE measures the average absolute deviation between the original and reconstructed web requests, providing a clear and intuitive measure of reconstruction accuracy.

Unlike Mean Squared Error (MSE), which disproportionately amplifies the effect of outliers due to its squared loss formulation, MAE is less sensitive to extreme deviations. This stability makes MAE particularly well-suited for anomaly detection, as it emphasizes individual discrepancies without being overly influenced by rare, extreme variations. By leveraging linear reconstruction errors, MAE effectively differentiates between benign and malicious web requests while ensuring an optimal balance between detection rates and false positives. This makes it an appropriate choice for evaluating the performance of web attack detection models.

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is formally defined as:

In Formula (7),

represents the reconstructed value, while

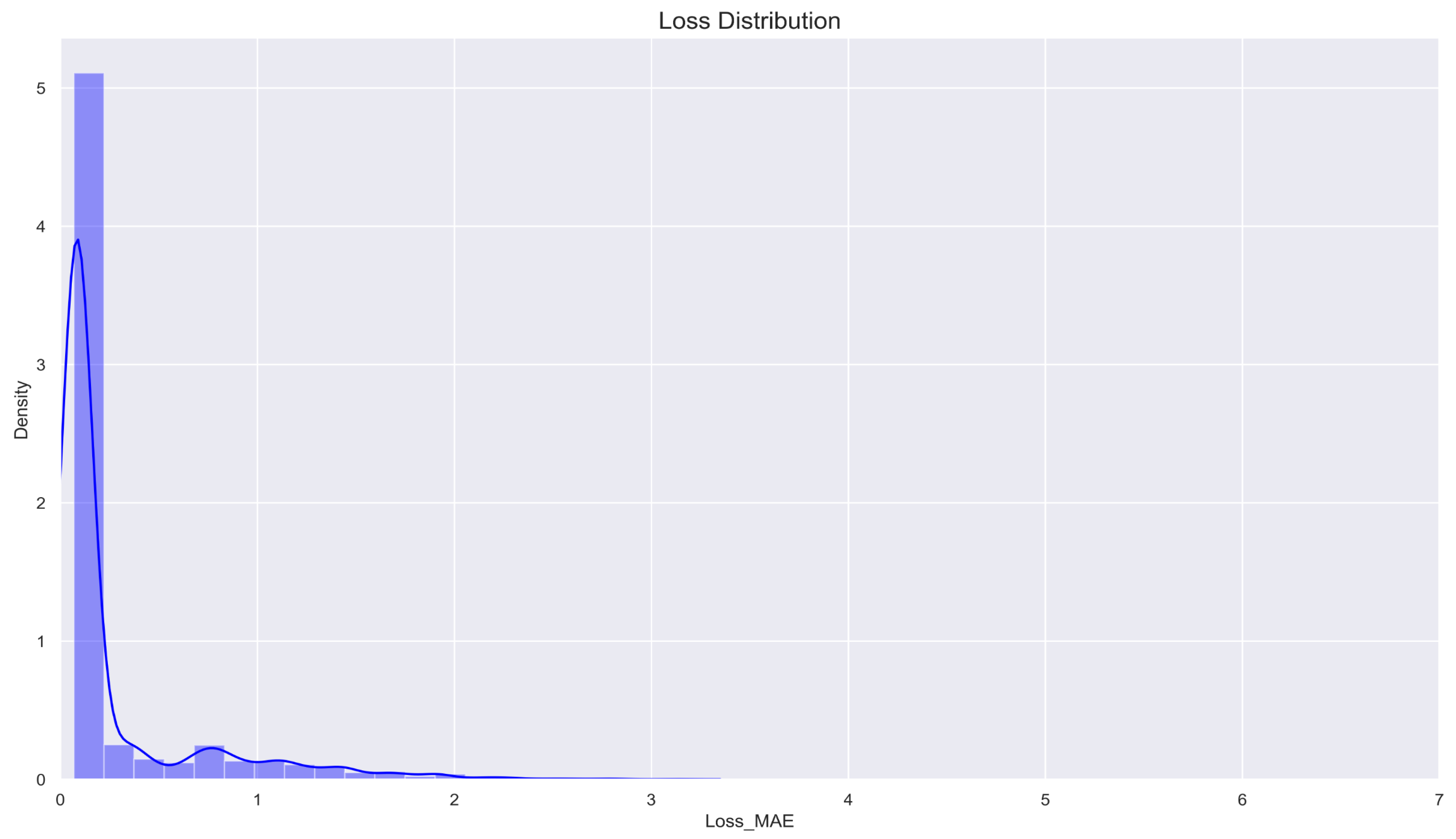

denotes the actual value. The classification criterion is based on the computed MAE for a given web request: if the MAE falls below a predefined threshold, the request is classified as normal; otherwise, it is identified as malicious. The threshold value is determined using

Figure 9, which visualizes the density distribution of web requests based on the MAE metric. This methodology effectively differentiates benign from malicious web requests, utilizing MAE as a robust anomaly detection measure. Based on the analysis in

Figure 9, an optimal threshold value of approximately 4 is identified.

During training, the neural network is trained exclusively on 80% of normal web requests, while malicious requests are introduced only during the detection phase. The optimal threshold is determined empirically through iterative experimentation. The analysis suggests that a threshold value of 4.09 provides optimal detection performance, as requests with an MAE of 5 or higher are observed infrequently. However, setting the threshold too high (e.g., at 7) may improve training results but could fail to detect certain malicious requests with reconstruction errors in the range of 5 to 7. This would compromise the model’s effectiveness in distinguishing anomalous web activity. A practical example from the model’s output further illustrates this decision-making process.

5.1. Data Collection

Previous research on detecting malicious and zero-day web requests has primarily relied on two well-established datasets: CSIC [

31] and HTTPPARAMS [

31]. These datasets provide a comprehensive representation of both normal and malicious web requests, making them widely used benchmarks in web security research. Additionally, a project hosted on GitHub [

32], which employs Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has utilized the CSIC 2012 dataset. Accordingly, the proposed model leverages this dataset for training and evaluation.

The dataset utilized in this study is significant due to the following characteristics:

It encompasses a diverse range of malicious requests, including SQL Injection (SQLi), Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), and Buffer Overflow attacks.

It contains normal (benign) web requests, ensuring a balanced distribution of data for effective training and evaluation.

A key consideration in dataset selection is ensuring that malicious requests accurately reflect real-world attack scenarios. The dataset comprises approximately 16,000 instances labeled as anomalous. However, certain anomalies may arise from factors unrelated to direct cyberattacks, such as unusual user behavior, malformed requests, or suspicious data entry attempts. These cases, while indicative of potential security threats, do not strictly conform to defined attack patterns. To maintain data integrity and ensure the model is trained on well-defined attack and normal request samples, such ambiguous anomalies are removed from the dataset prior to training.

5.2. The Ensemble Model Structure

As illustrated in

Figure 12, the proposed ensemble model is designed for performance optimization, with a numerical sequence length and an input layer comprising 50 cells for each web request. Each autoencoder follows a simple yet effective architecture, consisting of an input layer with 50 cells, a middle layer with 25 cells, and an output layer with 50 cells. The outputs from these autoencoders are subsequently merged to form the final output of the ensemble model. A compression operation is then applied to align the feature count of the final output with that of the input data, ensuring consistency and improving computational efficiency.

Various numerical sequence lengths (e.g., 60 or 70) and more complex sub-model architectures were explored during model optimization. However, the combination of an input length of 50 and a middle layer size of 25 demonstrated the best overall performance, achieving an optimal balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency.

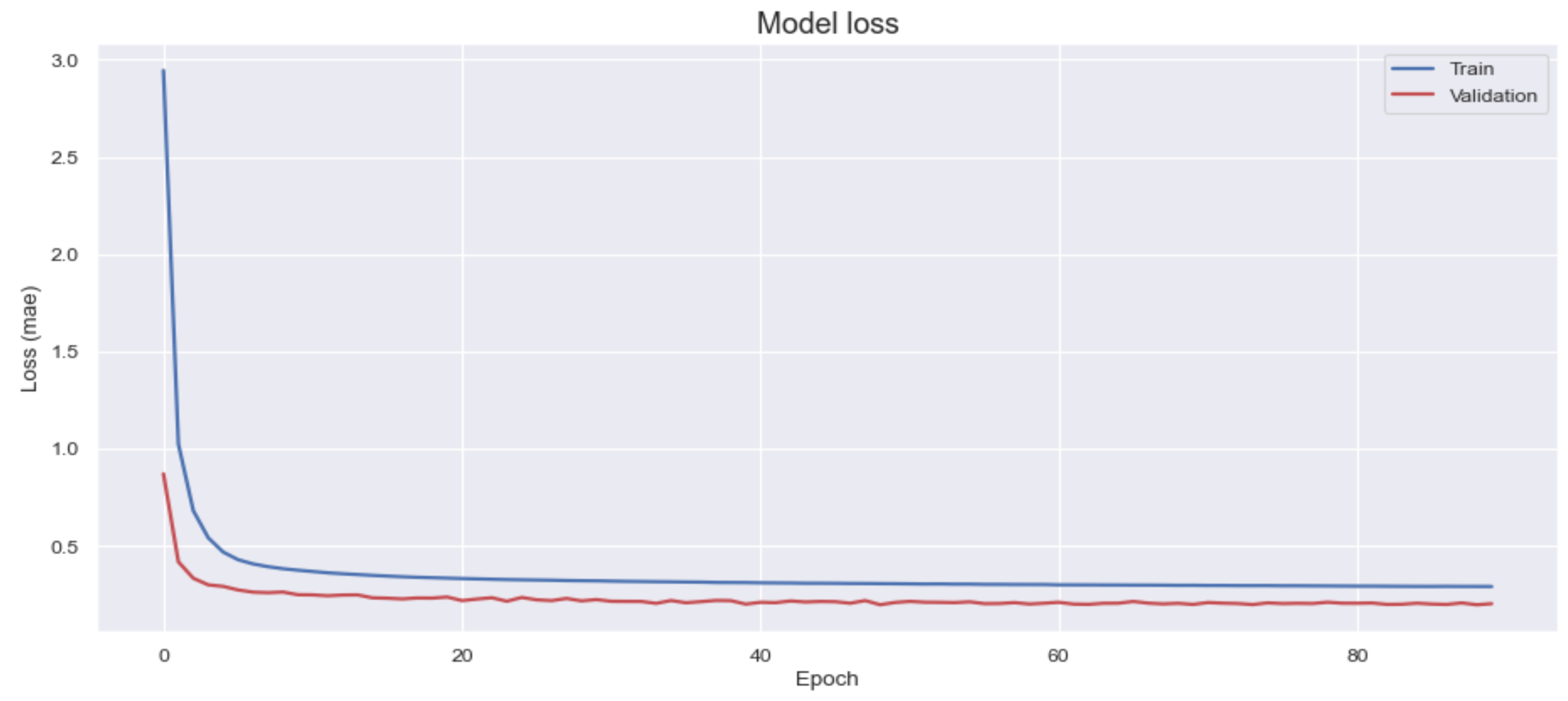

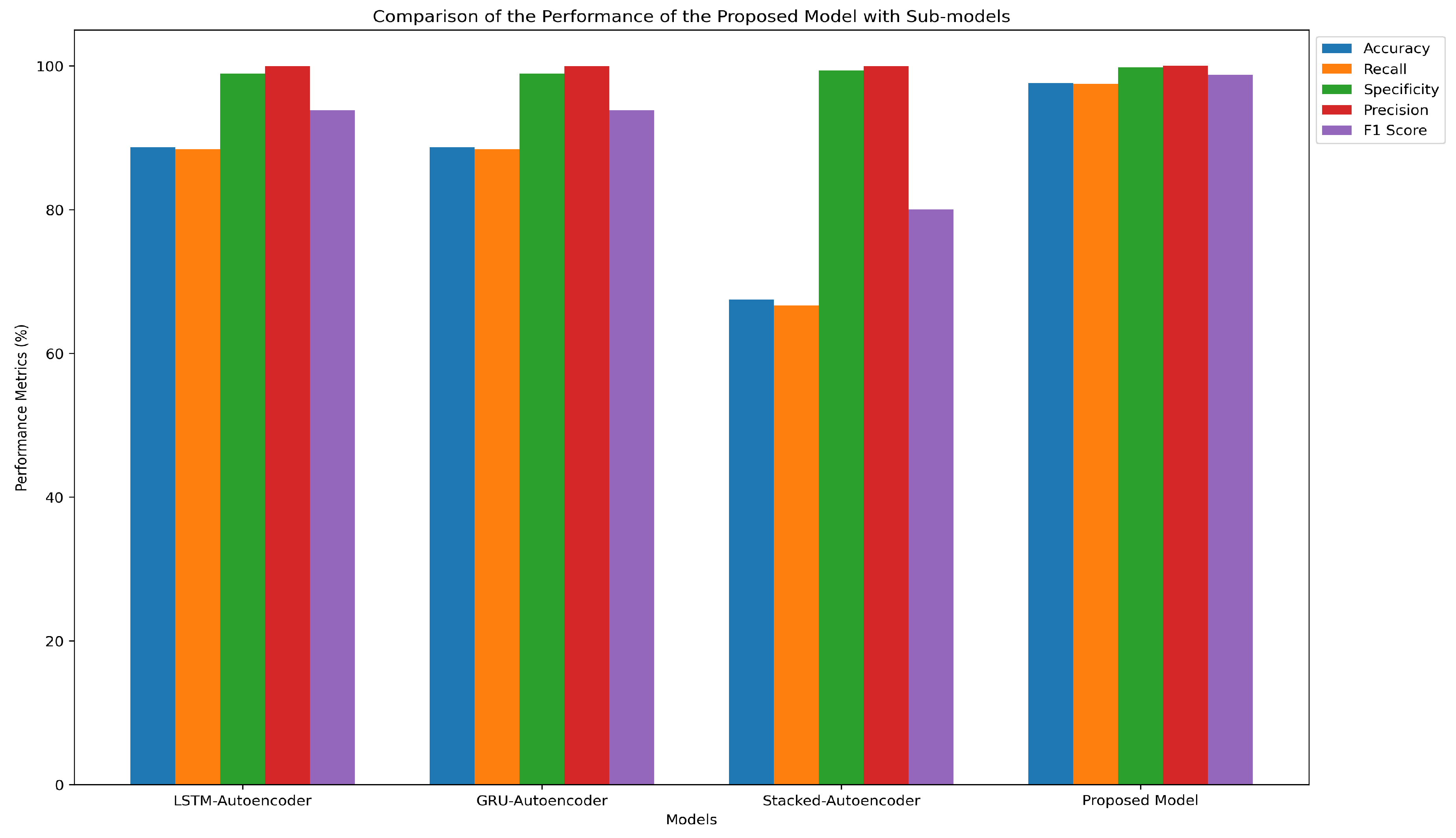

The evaluation results of the proposed model, as depicted in

Figure 10, illustrate the training process. Over the course of 90 epochs, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) metric exhibited a significant reduction, decreasing from approximately 3 to around 0.5. This trend indicates that, in the initial training stages, a substantial discrepancy existed between the decoded and original values. However, as the ensemble model progressively learned the patterns of normal web requests, the reconstruction error diminished, reflecting an improvement in model accuracy.

The dataset utilized for training and validation followed an 80-20 split, with 80% of the data allocated for training and the remaining 20% reserved for validation. This partitioning ensures that the model is effectively trained while being rigorously evaluated on an unseen subset of data, enabling a more reliable assessment of its generalization capability.

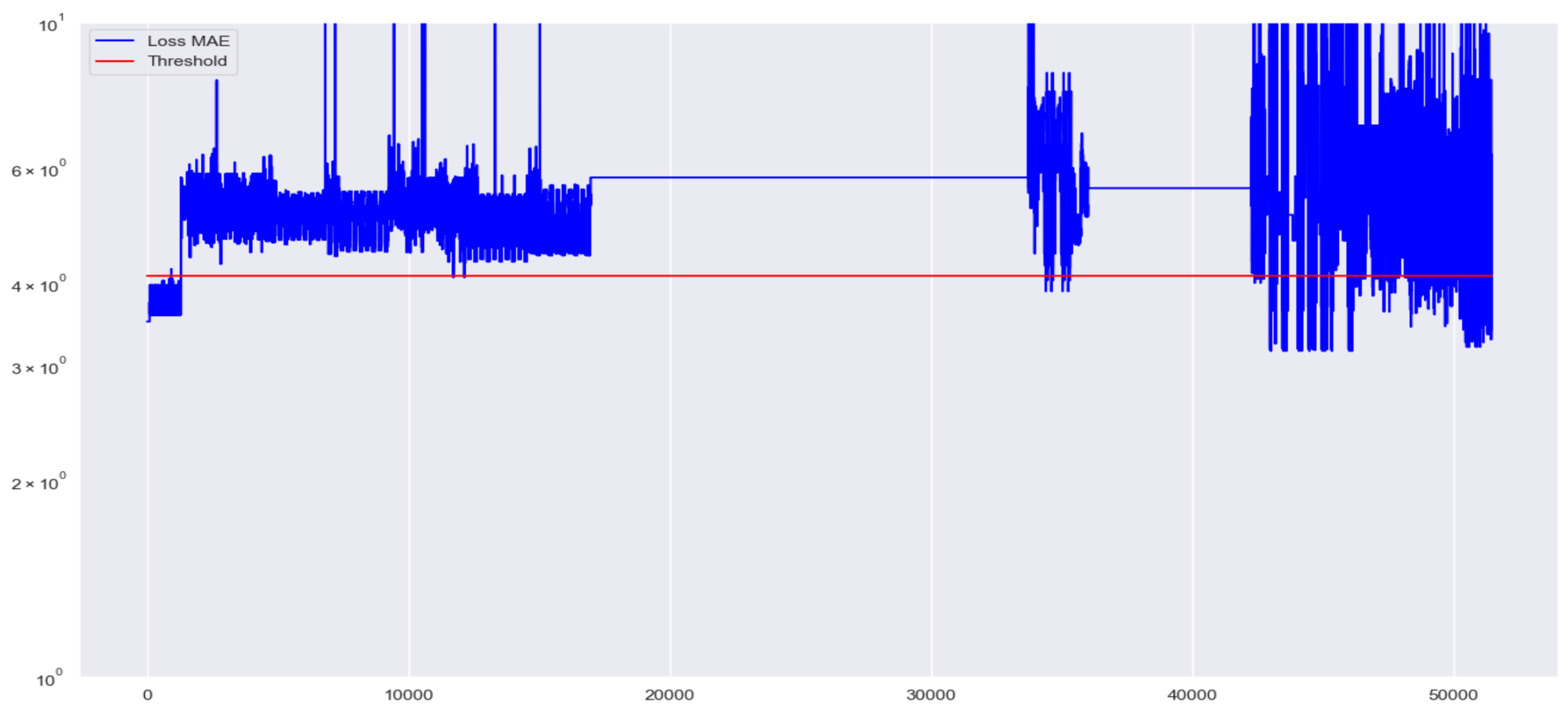

Following the detection phase, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for each web request is computed and compared against the predefined threshold. As illustrated in

Figure 11, the calculated MAE values for individual web requests are represented in blue, while the threshold value is indicated by a red line. Web requests with an MAE exceeding the threshold (blue points above the red line) are classified as malicious, whereas those with an MAE below the threshold (blue points below the red line) are categorized as normal requests. The final performance evaluation of the proposed model is summarized in

Table 3.

The ensemble model, incorporating LSTM, GRU, and stacked autoencoder sub-models, demonstrates superior performance across all evaluation metrics compared to each sub-model individually. The reported results represent the average performance obtained over six independent runs of the model.

The system components utilized for evaluating the proposed model consists of key components as shown in

Table 1, including LSTM, GRU, and Stacked Autoencoder for neural network-based processing, running on Windows 11 with Python v3.12 as the programming language. The implementation leverages Scikit-learn v1.6.0 for machine learning functionalities and WordPunctTokenizer from the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) for splitting a text into a sequence of words. Additionally, the Tokenizer class is employed for converting text data into numerical sequences, ensuring compatibility with neural networks. The model’s performance is evaluated using Mean Absolute Error (MAE), which quantifies the difference between predicted and actual values, providing an effective measure for anomaly detection. The training phase required approximately 20 s, while the test phase was completed in 5 s. The model was implemented using Python version 3.12 with the Keras framework.

5.3. Results

The results indicate that the proposed ensemble model achieves robust performance across all evaluation metrics, whereas individual sub-models exhibit certain limitations. Specifically, while the LSTM and GRU autoencoders demonstrate high accuracy, sensitivity, and precision, they suffer from an elevated false positive rate due to the number of normal requests misclassified as malicious.

The stacked autoencoder, on the other hand, improves the false positive rate but exhibits weaker performance in precision and recall. By combining these sub-models in an ensemble framework, their respective weaknesses are balanced, leading to an overall improvement in detection performance.

An analysis of the false positive rate reveals that both LSTM and GRU sub-models incorrectly classified 14 out of 1,299 normal requests as malicious, which is suboptimal for real-world deployment. To mitigate this issue, the inclusion of a third sub-model was explored, aiming to enhance model robustness against false positive errors.

Table 2 presents key terms used for calculating various performance metrics associated with the models. This table serves as a reference for understanding and computing essential evaluation indicators. The performance assessment of the proposed model involves the computation of six primary metrics: accuracy, precision, sensitivity, detection rate, false positive rate, and F1 score. These metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation framework for analyzing the effectiveness and robustness of the model in detecting web-based threats.

Figure 12.

Ensemble model architecture.

Figure 12.

Ensemble model architecture.

As shown in

Table 3, the stacked autoencoder significantly reduces the false positive rate. However, its performance in accuracy and recall remains comparatively weaker.

Figure 13 illustrates this comparison in the form of a bar chart graph.

These findings suggest that each sub-model possesses distinct advantages and disadvantages across different evaluation metrics. The ensemble approach effectively leverages the strengths of individual sub-models while minimizing their weaknesses, ensuring a more balanced and reliable detection system.

Table 3.

Comparison of the Performance of the Proposed Model with the Sub-models.

Table 3.

Comparison of the Performance of the Proposed Model with the Sub-models.

| Models |

Accuracy |

Recall |

Specificity |

Precision |

False Positive Rate |

F1 Score |

| LSTM-Autoencoder |

88.68% |

88.41% |

98.92% |

99.96% |

1% |

93.83% |

| GRU-Autoencoder |

88.69% |

88.42% |

98.92% |

99.96% |

1% |

93.83% |

| Stacked-Autoencoder |

67.48% |

66.65% |

99.38% |

99.97% |

0.6% |

79.98% |

| Proposed Model |

97.58% |

97.52% |

99.76% |

99.99% |

0.2% |

98.74% |

Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed model’s performance against various models from previous research that have utilized the CSIC2010 and CSIC2012 datasets. This comparison provides insights into the effectiveness of the proposed approach relative to existing solutions in the field. One notable limitation in prior studies is the omission of the False Positive Rate (FPR) in their evaluation results. This metric is crucial, as it quantifies the number of normal requests misclassified as malicious, directly impacting the practical applicability of detection models.

Figure 14 illustrates this comparison in the form of a bar chart graph. In the figure we have colored the models that utilized CSIC2012 dataset with red color.

The primary comparison focuses on studies that have employed the CSIC2012 dataset [

9,

10,

21], as they provide the most directly comparable benchmark. However, to offer a broader perspective, we also include studies based on the CSIC2010 dataset [

11,

13,

14,

17,

18,

19,

20,

22,

23]. It is important to note that differences in dataset characteristics may influence the comparability of results.

The CSIC2010 and CSIC2012 datasets are widely recognized benchmarks for evaluating web application security models, particularly for detecting SQL Injection (SQLi) and other web-based attacks. The CSIC2010 dataset, developed earlier, contains a diverse set of normal and anomalous HTTP requests. While it provides a solid foundation for studying web attack detection, it lacks the complexity and evolving attack patterns characteristic of modern cybersecurity threats.

To address these limitations, the CSIC2012 dataset was designed with more sophisticated and realistic attack scenarios, along with a broader range of normal traffic. This makes CSIC2012 a more representative dataset for contemporary web security challenges. Additionally, CSIC2012 includes refined labeling and a larger volume of data, enhancing its suitability for training and evaluating advanced machine learning models.

These distinctions underscore the importance of selecting CSIC2012 for research targeting modern web application threats, as it serves as a more rigorous and up-to-date evaluation benchmark compared to its predecessor.

6. Discussion

According to the obtained results, the proposed model demonstrates strong performance across all evaluation metrics, particularly in terms of the False Positive Rate (FPR). The model achieves the lowest FPR compared to related work referenced in this study, highlighting its ability to accurately differentiate between normal and malicious web requests. This is a critical aspect of web security, as a high FPR would indicate an increased likelihood of blocking legitimate users, thereby compromising usability.

6.1. Effectiveness of the Ensemble Model

The proposed ensemble model comprises three fundamental sub-models: LSTM, GRU, and Stacked Autoencoder. Each sub-model plays a distinct role in detecting malicious web requests, contributing unique advantages:

LSTM Autoencoder: Captures long-term dependencies in web request sequences, enhancing the ability to recognize complex request structures.

GRU Autoencoder: Provides computational efficiency while preserving strong sequential pattern recognition capabilities.

Stacked Autoencoder: Focuses on dimensionality reduction and latent feature extraction, improving anomaly detection in subtle attack patterns.

By integrating these sub-models, the ensemble model achieves a well-balanced performance across multiple evaluation metrics, effectively mitigating the weaknesses of individual sub-models. The ensemble approach significantly enhances accuracy, recall, and precision while substantially reducing false positives compared to each sub-model independently.

6.2. Practical Considerations and Limitations

Although the proposed model demonstrates robust performance on benchmark datasets, its real-world deployment in web security applications requires additional considerations. One of the primary challenges is the variability in web request patterns across different applications and domains. While the tokenization and feature extraction methods effectively standardize the CSIC2012 dataset, these techniques should be extended to other datasets, such as FWAF and HTTPParams [

33], to enhance generalization.

Additionally, while the model is designed to detect zero-day attacks, it does not explicitly classify attack types (e.g., SQL Injection, Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), Buffer Overflow). Future research should focus on integrating an attack-type classification mechanism alongside anomaly detection to improve forensic analysis and threat response capabilities.

7. Conclusions

In this study, each web request was initially segmented into individual words and subsequently tokenized using a predefined vocabulary. This preprocessing step aimed to reduce the size of web requests while establishing a structured pattern for normal web traffic. In the final stage of preprocessing, each tokenized word was mapped to a unique numerical representation, facilitating its input into the neural network. The proposed model employs an ensemble approach comprising three relatively simple sub-models: LSTM, GRU, and Stacked Autoencoders. The ensemble operates by independently processing the input data through each sub-model and subsequently merging the decoded numerical sequences. A final feature compression step is then applied to align the output feature dimensions with those of the input data.

During the training phase, only normal web requests were provided as input to the ensemble model, enabling it to learn the underlying patterns of legitimate requests. Upon completion of training, the model effectively captured and recognized these patterns. In the detection phase, both normal and malicious web requests were introduced for evaluation. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) was employed as the primary metric to quantify the difference between the reconstructed and original values of each request. The threshold for classification was determined based on the MAE values computed during the training phase. In the detection phase, if the MAE of a web request was below the threshold, it was classified as normal; otherwise, it was identified as malicious.

During evaluation, the ensemble model’s performance was compared against each of its sub-models individually. The results demonstrated that the ensemble approach achieved superior performance, particularly in terms of an increased detection rate and a reduced false positive rate. Additionally, the proposed model was benchmarked against prior research, where it consistently outperformed existing approaches, further validating its effectiveness in detecting web-based threats.

8. Future Work

One potential direction for future research involves enhancing the tokenization and feature extraction process [

34] across diverse web attack datasets. This improvement can be achieved through the application of Generative AI, leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) [

35,

36]. Specifically, prompt engineering [

37] can be employed to construct a structured prompt that systematically guides the LLM in preprocessing each dataset sample.

A few-shot learning approach can be utilized to accomplish this by providing representative examples from each dataset, detailing the exact tokenization process required for each sample. This method ensures that the LLM internalizes dataset-specific preprocessing rules while maintaining uniformity across different datasets.

Another approach involves automating the preprocessing pipeline by generating customized script code [

38] for each dataset. This method leverages LLMs to autonomously generate preprocessing scripts based on structured prompts that define tokenization rules and feature extraction strategies. While manual scripting was employed in this study for data preprocessing, future research will focus on automating this process using LLMs, thereby minimizing human intervention and improving scalability across diverse datasets.

Beyond advancements in preprocessing, future efforts will explore the implementation of advanced neural architectures, such as Bidirectional LSTM, GRU, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

39], to develop a more robust ensemble model for web attack detection. Additionally, feature selection techniques will be applied to retain high-information-value features while eliminating less significant ones, effectively reducing input dimensionality and enhancing computational efficiency.

Furthermore, the integration of a voting-based ensemble learning approach will be investigated to improve detection accuracy by combining multiple classifiers. This strategy aims to leverage the strengths of individual models, resulting in a more generalized and resilient web attack detection framework.

References

- Ahmad, R.; Alsmadi, I.; Alhamdani, W.; Tawalbeh, L. Zero-day attack detection: a systematic literature review. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 10733–10811.

- Dawadi, B.R.; Adhikari, B.; Srivastava, D.K. Deep learning technique-enabled web application firewall for the detection of web attacks. Sensors 2023, 23, 2073. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, Y.L.; Por, L.Y.; Ku, C.S. A systematic literature review of information security in chatbots. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 6355.

- Calzavara, S.; Conti, M.; Focardi, R.; Rabitti, A.; Tolomei, G. Machine learning for web vulnerability detection: the case of cross-site request forgery. IEEE Security & Privacy 2020, 18, 8–16.

- Ahmed, M.; Mahmood, A.N.; Hu, J. A survey of network anomaly detection techniques. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2016, 60, 19–31.

- Pu, G.; Wang, L.; Shen, J.; Dong, F. A hybrid unsupervised clustering-based anomaly detection method. Tsinghua Science and Technology 2020, 26, 146–153.

- Long, H.V.; Tuan, T.A.; Taniar, D.; Can, N.V.; Hue, H.M.; Son, N.T.K. An efficient algorithm and tool for detecting dangerous website vulnerabilities. International Journal of Web and Grid Services 2020, 16, 81–104.

- Ingham, K.L.; Somayaji, A.; Burge, J.; Forrest, S. Learning DFA representations of HTTP for protecting web applications. Computer Networks 2007, 51, 1239–1255.

- Sivri, T.T.; Akman, N.P.; Berkol, A.; Peker, C. Web intrusion detection using character level machine learning approaches with upsampled data. Annals of Computer Science and Information Systems 2022, 32.

- Jung, I.; Lim, J.; Kim, H.K. PF-TL: Payload feature-based transfer learning for dealing with the lack of training data. Electronics 2021, 10, 1148. [CrossRef]

- Vartouni, A.M.; Kashi, S.S.; Teshnehlab, M. An anomaly detection method to detect web attacks using stacked auto-encoder. In Proceedings of the 2018 6th Iranian Joint Congress on Fuzzy and Intelligent Systems (CFIS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 131–134.

- Ariu, D.; Tronci, R.; Giacinto, G. HMMPayl: An intrusion detection system based on Hidden Markov Models. computers & security 2011, 30, 221–241.

- Liang, J.; Zhao, W.; Ye, W. Anomaly-based web attack detection: a deep learning approach. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 VI International Conference on Network, Communication and Computing, 2017, pp. 80–85.

- Kuang, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Zhao, G.; Cao, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X. DeepWAF: detecting web attacks based on CNN and LSTM models. In Proceedings of the Cyberspace Safety and Security: 11th International Symposium, CSS 2019, Guangzhou, China, December 1–3, 2019, Proceedings, Part II 11. Springer, 2019, pp. 121–136.

- Tang, R.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Meng, W.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Sun, Y.; Pei, D.; Wei, T.; Xu, Y.; et al. Zerowall: Detecting zero-day web attacks through encoder-decoder recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2020-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications. IEEE, 2020, pp. 2479–2488.

- Indrasiri, P.L.; Halgamuge, M.N.; Mohammad, A. Robust ensemble machine learning model for filtering phishing URLs: Expandable random gradient stacked voting classifier (ERG-SVC). Ieee Access 2021, 9, 150142–150161.

- Gong, X.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Qiu, H.; He, R. Model uncertainty based annotation error fixing for web attack detection. Journal of Signal Processing Systems 2021, 93, 187–199. [CrossRef]

- Tekerek, A. A novel architecture for web-based attack detection using convolutional neural network. Computers & Security 2021, 100, 102096.

- Jemal, I.; Haddar, M.A.; Cheikhrouhou, O.; Mahfoudhi, A. SWAF: a smart web application firewall based on convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2022 15th International Conference on Security of Information and Networks (SIN). IEEE, 2022, pp. 01–06.

- Alaoui, R.L.; et al. Web attacks detection using stacked generalization ensemble for LSTMs and word embedding. Procedia Computer Science 2022, 215, 687–696.

- Mohamed, S.M.; Rohaim, M.A. Multi-Class Intrusion Detection System using Deep Learning. Journal of Al-Azhar University Engineering Sector 2023, 18, 869–883.

- Shahid, W.B.; Aslam, B.; Abbas, H.; Khalid, S.B.; Afzal, H. An enhanced deep learning based framework for web attacks detection, mitigation and attacker profiling. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2022, 198, 103270.

- Moarref, N.; Sandıkkaya, M.T. MC-MLDCNN: Multichannel Multilayer Dilated Convolutional Neural Networks for Web Attack Detection. Security and Communication Networks 2023, 2023, 2415288.

- Thomas, S.; Koleini, F.; Tabrizi, N. Dynamic defenses and the transferability of adversarial examples. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 4th International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems, and Applications (TPS-ISA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 276–284.

- Khalid, M.N.; Farooq, H.; Iqbal, M.; Alam, M.T.; Rasheed, K. Predicting web vulnerabilities in web applications based on machine learning. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Technologies and Applications: First International Conference, INTAP 2018, Bahawalpur, Pakistan, October 23-25, 2018, Revised Selected Papers 1. Springer, 2019, pp. 473–484.

- Levene, M.; Poulovassilis, A.; Davison, B.D. Learning web request patterns. Web Dynamics: Adapting to Change in Content, Size, Topology and Use 2004, pp. 435–459.

- Vijayarani, S.; Janani, R.; et al. Text mining: open source tokenization tools-an analysis. Advanced Computational Intelligence: An International Journal (ACII) 2016, 3, 37–47.

- Rashvand, N.; Hosseini, S.S.; Azarbayjani, M.; Tabkhi, H. Real-Time Bus Arrival Prediction: A Deep Learning Approach for Enhanced Urban Mobility. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.15495 2023.

- Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017.

- Rashvand, N.; Witham, K.; Maldonado, G.; Katariya, V.; Marer Prabhu, N.; Schirner, G.; Tabkhi, H. Enhancing automatic modulation recognition for iot applications using transformers. IoT 2024, 5, 212–226. [CrossRef]

- Shaheed, A.; Kurdy, M.B. Web application firewall using machine learning and features engineering. Security and Communication Networks 2022, 2022, 5280158.

- DuckDuckBug. CNN Web Application Firewall. https://github.com/DuckDuckBug/cnn_waf, 2023. Accessed: January 29, 2025.

- Jagat, R.R.; Sisodia, D.S.; Singh, P. Detecting web attacks from HTTP weblogs using variational LSTM autoencoder deviation network. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2024. [CrossRef]

- Abshari, D.; Fu, C.; Sridhar, M. LLM-assisted Physical Invariant Extraction for Cyber-Physical Systems Anomaly Detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10918 2024.

- Zibaeirad, A.; Koleini, F.; Bi, S.; Hou, T.; Wang, T. A comprehensive survey on the security of smart grid: Challenges, mitigations, and future research opportunities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.07966 2024.

- Abshari, D.; Sridhar, M. A Survey of Anomaly Detection in Cyber-Physical Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13256 2025.

- Babaey, V.; Ravindran, A. GenSQLi: A Generative Artificial Intelligence Framework for Automatically Securing Web Application Firewalls Against Structured Query Language Injection Attacks. Future Internet 2025, 17, 8. [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Fu, Q.; Hays, S.; Sandborn, M.; Olea, C.; Gilbert, H.; Elnashar, A.; Spencer-Smith, J.; Schmidt, D.C. A prompt pattern catalog to enhance prompt engineering with chatgpt. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.11382 2023.

- Graves, A.; Jaitly, N.; Mohamed, A.r. Hybrid speech recognition with deep bidirectional LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE workshop on automatic speech recognition and understanding. IEEE, 2013, pp. 273–278.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).