1. Introduction

Phoenixin (PNX), a bioactive peptide described nearly a decade ago [

1], is highly conserved across mammalian and non-mammalian species, with phoenixin-14 and -20 being the most prominent bioactive forms giving rise to its physiological importance. PNX-14 is identical among multiple species including human, rat, mouse, dog and domestic pig, whereas PNX-20 differs in one amino acid between the coding region of human, canine or porcine sequences [

1].

Initially, this substance was assigned an important function in the regulation of reproductive processes due to its high expression in the rodent hypothalamus and pituitary gland, where, acting by one of the orphan receptors, G protein-coupled receptor 173 (GPR173), PNX was able to induce an increase of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor mRNA expression and potentiates GnRH receptor upregulation, followed by a subsequent release of luteinizing hormone (LH) or follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) from cultures of female pituitary cells [

1,

2]. Further studies have shown that the presence of this peptide is not only limited to the hypothalamo-pituitary complex, but PNX contributes to the central control of several other biological processes, including food intake, energy homeostasis, water balance, modulation of inflammation, memory or anxiety (for corresponding reviews see [

3,

4]).

It should be emphasized that PNX is present not only in brain structures, but the occurrence of this neuropeptide has also been confirmed in some nervous structures belonging to the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Currently available data, unfortunately concerning almost exclusively the rat PNS, have revealed the presence of PNX-immunoreactive (IR) cells and fibers in, among others, the spinal trigeminal tract and nucleus of the solitary tract, trigeminal and nodose ganglion cells, superficial layers of the dorsal horn (DH), and, last but not least, in afferent neurons of the dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) [

5]. This latter observation was recently confirmed and extended by the results of our recent publication analyzing the intraganglionic arrangement and chemical coding of PNX-IR cells in DRGs of domestic pig [

6]. Indirect confirmation of the sensory and/or autonomic projections of PNX-positive cells were the observations of Yosten and colleagues who demonstrated the presence of this peptide in a number of internal organs, such as esophagus, stomach, pancreas, spleen and lung [

1].

The sensory component of the innervation of internal organs and its proper functioning is an indispensable part of many processes regulating the activity of the human and animal organism. For instance, DRG sensory neurons of the lumbo-sacral levels of the spinal cord are a crucial part of the afferent part of the micturition reflex arch. Spinal afferent neurons working together with sympathetic and parasympathetic efferent nerves, play an important role in reflex control of urine storage and micturition. As reported by Bossowska et al., the porcine bladder receives dual afferent innervation originating from sensory neurons located in the lumbar (L3-L6) and sacro-coccygeal (S3-S4 and Cq1) DRGs [

7]. Since many urinary bladder disorders have a neurogenic background, it is important to unravel the physiological mechanisms regulating functions of this organ what, in turn, will allow us to better understand the pathological mechanisms causing dysfunctions of the urinary bladder.

As mentioned above, recent studies regarding PNX have shown that this peptide has widely been distributed in various peripheral tissues. However, until now there is no data regarding the presence of PNX in the urinary bladder or in neurons supplying this organ. Therefore, the present study has been designed to investigate

i) the pattern of PNX-IR sensory neurons occurrence in DRGs associated with the urinary bladder;

ii) pattern(s) of intraganglionic distribution of PNX-positive cells in the examined sensory ganglia, and,

iii) pattern(s) of colocalization of PNX with other markers of sensory neurons (calretinin- CRT; calcitonin gene-related peptide-CGRP; galanin-GAL; neuronal nitric oxide synthase- nNOS; pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-PACAP; substance P-SP and somatostatin-SOM) in the bladder sensory neurons of the L as well as the S-Cq neuromeres of the porcine spinal cord. The domestic pig has been chosen for this study, as this species is increasingly employed as an animal model, because of the anatomical and physiological similarities to humans, in regard to both the structure and function of various tissues and organs [

8,

9,

10].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Laboratory Animals

Investigations were conducted using six immature (8–12 weeks old, 15–20 kg body weight - b.w.) female pigs of the Large White Polish breed. All the animals originated from a commercial fattening farm and were kept under standard laboratory conditions. They were fed standard fodder (Grower Plus, Wipasz, Wadąg, Poland) and had free access to water. The animals were housed and treated in accordance with the rules of the Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation in Olsztyn (affiliated to the National Ethics Commission for Animal Experimentation, Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education; decision No. 40/2020 from 22 July 2020r). All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. As the present study was designated to provide basic data concerning the chemical phenotypes of the subpopulation of PNX-containing DRG neurons involved in the afferent innervation of the urinary bladder wall under physiological conditions, the authors decided to focus on sexually immature female pigs in order to exclude any possible influences of reproductive hormones on studied tissues as identified in previous studies [

11,

12].

2.2. Anesthesia and Surgical Procedures

Before performing any surgical procedure, all the animals were pretreated with atropine (Polfa, Poland, 0.05 mg/kg b.w., subcutaneous (s.c.) injection) and azaperone (Stresnil, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Belgium; 0.5 mg/kg b.w., intramuscular (i.m.) injection). Next, buprenorphine (Bupaq, Richter Pharma AG, Austria, 20 μg/kg b.w.) was given in a single i.m. injection to abolish the visceral pain sensation. Thirty minutes later, to induce anesthesia, the main anesthetic drugs: sodium pentobarbital (Tiopental, Sandoz, Poland; 0.5 g per animal, administered according to the effect) and ketamine (Bioketan, Vetoquinol, Poland, 10 mg/kg b.w.) were given intravenously in a slow, fractionated infusion. The depth of anesthesia was monitored by testing the corneal reflex.

A mid-line laparotomy was performed in all the animals (n=6), and the urinary bladder was gently exposed to administer a total volume of 40 µL of 5% aqueous solution of the fluorescent retrograde tracer Fast Blue (FB; Dr K. Illing KG & Co GmbH, Gross Umstadt, Germany) into the right side of the urinary bladder body wall in multiple injections (1 μL of the dye solution per 1 injection with a Hamilton microsyringe equipped with a 26S gauge needle) under the serosa along the whole extension of the urinary bladder dome, keeping a similar distance between the places of injections. To avoid the leakage of the dye, the needle was left in each place of FB injection for about one minute. The wall of the injected organ was then rinsed with physiological saline and gently wiped with gauze. Three weeks later, which is a minimum time period needed for the retrograde tracer to be transported to the DRGs and label the urinary bladder-projecting neurons (UB-PNs) [

7], the animals were deeply anaesthetized (following the same procedure as was described above) and, after the cessation of breathing, transcardially perfused with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Following the perfusion, all the animals were dissected and the bilateral DRGs were collected from all animals studied (as described previously in detail by Bossowska et al. [

7]). Tissue samples were then postfixed by immersion in the same fixative (10 min at room temperature), washed several times in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4; 4 °C; twice a day for three days), and finally transferred to and stored in 18% buffered sucrose at 4 °C (two weeks) until sectioning.

2.3. Sectioning of the Tissue Samples and Estimation of the Total Number of UB-PNs

Samples of the ipsi- as well as the contralateral DRGs studied were pairwise located on a pre-cooled block made of a drop of the ‘optimal cutting temperature’ compound medium (OCT) in a manner allowing easy determination of the position of individual subdomains of DRG sections under the microscope. Frozen ganglia were cut with an HM525 Zeiss freezing microtome on transverse 10-µm-thick serial sections (four sections on each slide), mounted on chrome alum-gelatine-coated slides, air dried, and examined under the fluorescent Olympus BX61 microscope equipped with a filter set allowing the visualization of FB-positive (FB+) neurons. To determine the relative number of UB-PNs, FB-positive nerve cells were counted in every fourth section (to avoid double-counting of the same neuron; most neurons were approximately 40 μm in diameter) prepared from both the ipsi- and contralateral ganglia of all animals. Only neurons with a clearly visible nucleus were considered. The results were pooled for every experimental animal and statistically analyzed, and the mean number of FB-positive cells was calculated. The total number of FB+ nerve cells counted in all the ipsilateral and contralateral DRG from a particular animal as well as the relative frequencies of perikarya in the ganglia belonging to the individual neuronal size classes were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The diameter of the FB+ perikarya was measured by means of an image analysis software (version 3.02, Soft Imaging System, Münster, Germany), and data were used to divide urinary bladder-projecting neurons into the three size-classes: small (average diameter up to 40µm), medium-sized (diameter 41–70 µm), and large afferent cells (diameter > 70 µm), while the statistical analysis was performed with Graph-Pad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.4. Immunohistochemical Procedure

Double-immunofluorescence was performed on cryostat sections of both the ipsi- and contralateral DRGs where the UB-PNs were found, according to a previously described method [

7]. Immunohistochemical characteristics of FB

+ neurons were investigated using primary antibodies raised in different species. After immersion of the tissues in a blocking solution containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 1% Triton X 100, 0.01% sodium azide (NaN

3), 0.05% thimerosal and 10% normal goat serum in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1h at room temperature to reduce non-specific background staining, sections were repeatedly rinsed in PBS, and then incubated overnight at room temperature with PNX antiserum applied in a mixture with antisera against: CGRP, CRT, GAL, nNOS, PACAP and SOM (the presence of all the above-mentioned active substances, or their marker enzymes (nNOS) was previously revealed in the porcine UB-PNs [

7,

13,

14,

15]. Primary antisera were visualized by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rat- or mouse-immunoglobulin G (IgG) specific secondary antisera or biotin-conjugated anti-rabbit specific antiserum. The latter complexes were then visualized by application of CY3-conjugated streptavidin. The application of primary antisera raised in different species allowed to assess the coexistence of investigated biological active substances. Details concerning all the primary and secondary antibodies used in the present study are listed in

Table 1.

Retrogradely labelled and double-immunostained DRG perikarya were evaluated under an Olympus BX61 microscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) equipped with epifluorescence filter for FB and an appropriate filter set for CY3 or FITC. Relationships between immunohistochemical staining and FB distribution were examined directly by interchanging filters. The images were taken with an Olympus XM10 digital camera (Tokyo, Japan). The microscope was equipped with cellSens Dimension 1.7 Image Processing software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, Münster, Germany).

2.5. Estimation of the Chemical Coding of the DRG UB-PNs

All sections containing FB+ neurons were used for double-immunohistochemical labelling. To determine the percentages of particular neuronal subpopulations, FB+ neuronal profiles were investigated with a combination of two primary antisera on each section (four sections per slide) and counted in both (ipsi- and contralateral) DRGs in each animal studied. Relationships between immunohistochemical staining and FB distribution were examined directly by interchanging filters. To avoid double counting of the same neurons, the retrogradely labeled neuronal cells were counted in every fourth section (only neurons with clearly visible nucleus were included). The colocalization pattern(s) of PNX with other biologically active substances in FB+ neurons were examined on consecutive sections. The percentages of FB+ neurons immunopositive to the individual biologically active substances or their marker enzyme were pooled in all the animals and presented as mean ± SD, with “n” referring to the number of animals. Morphometric data relative to each neuronal class were compared within each animal and among the animals and were analyzed by the student’s two-tailed t test for unpaired data using GraphPad PRISM 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). The differences were considered to be significant at p < 0.05.

2.6. Control of Specificity of the Tracer Staining and Immunohistochemical Procedures

The FB injection sites and the tissues adjacent to the urinary bladder were carefully examined macroscopically prior to the collection of DRGs for examination. The injection sites were easily identified by the yellow-labeled deposition left by the tracer within the bladder wall. Moreover, the injection sites were also observed in the UV lamp rays in the dark room. The tissues adjacent to the bladder were not found to be contaminated with the tracer. To verify that the tracer had not migrated into the urethra, we analyzed, in cryostat sections and by means of the H&E staining technique (IHC WORLD LLC, Woodstock, NY, USA), possible signs of leakage of the tracer to the junction between the urinary bladder trigone and cranial portion of the urethra. No contamination of the urethra with a tracer was found in all the animals studied. All above-mentioned procedures excluded any leakage of the tracer and validated the specificity of the tracing protocol.

To test the specificity of primary antibodies and staining reaction, preincubation tests were performed with the sections from DRG ganglia of the control pigs. Preabsorption for the neuropeptide antisera (20 μg of appropriate antigen per 1 ml of the corresponding antibody at working dilution; all antigens purchased from Peninsula, SWANT, Sigma, Phoenix -

Table 2), as well as an omission and replacement of the respective primary antiserum with the corresponding nonimmune serum completely abolished immunofluorescence and eliminated specific labeling.

4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

The analysis of literature clearly shows that PNX may be involved in sensory transmission. PNX was detected in the epidermis and dermis, and moreover, this peptide was found also in skin-projecting DRG neurons [

16]. It has also been demonstrated that PNX had a similar distribution in the dorsal horn and DRGs as gastrin-releasing peptide, which causes itching [

16].

Lyu et al. revealed that PNX is expressed in DRG neurons in rodents [

5], however the results of the present study for the first time have shown that PNX is present in the porcine DRG sensory neurons supplying the urinary bladder. This neuropeptide has been detected in the small- and medium-sized DRG neurons, but it was absent from the large-diameter cells. It is well known that small- and medium-sized DRG neurons are involved in pain transmission [

17,

18]. Considering that Lyu et al. showed PNX can reduce visceral pain, but not thermally evoked pain [

5], this phenomenon may also suggest putative influence of PNX on nociceptive transmission from the urinary bladder.

The main co-transmitter of PNX is SP, a tachykinin distributed throughout the central and peripheral nervous system. The literature clearly shows that SP is involved in classical and neurogenic inflammatory response at the peripheral level [

19,

20]. In the lower urinary tract, SP induces bladder contraction and facilitates normal micturition [

21]. Moreover, SP is recognized as a peptide involved in nociceptive transmission [

22]. Co-expression of PNX with SP may suggest that PNX, being present in a significant fraction of SP-IR cells, influences micturition and nociception, by modulation of SP-driven stimulation. However, this speculation needs confirmation in further studies.

CGRP is a peptide associated with several pathological conditions, among others the modulation of the releasing of inflammatory cytokines, in sepsis or in airways through hyperemia [

23]. It was also shown that CGRP level is increased during migraine attack [

24]. Considering the above data, as well as the relatively frequent co-occurrence with SP in retrogradely labeled DRG cells, it may be speculated that CGRP is also involved in nociceptive transmission. Although in the lower urinary tract CGRP has no excitatory effect on the micturition reflex pathway

per se, it is able to facilitate the SP-evoked chemonociceptive reflex [

25]. CGRP inhibits the activity of an endopeptidase that degrades SP [

26], thus may “improve” and extend the time of SP action. A large number of FB

+ PNX-IR cells containing SP and/or CGRP indicates putative connection of PNX with bladder contraction and nociceptive transmission. Moreover, it is widely known that the release of CGRP and SP were significantly increased following inflammation [

27]. It strongly suggests that PNX may involve sensory transmission.

The next most abundant population of PNX

+ cells, as shown by double immunofluorescence studies, were neurons containing either PACAP or GAL simultaneously. The presence of PACAP in sensory neurons serving various afferent pathways has been found in virtually every area of the human body [

28], and this molecule seems to play a significant role in many different physio- and pathophysiological processes. For example, it was investigated and observed that the intravenous infusion of PACAP in healthy human volunteers caused a slight headache or, rather, a feeling of increasing pressure in the head [

29], which may suggest that, similarly to CGRP, this transmitter may also be a factor involved in the etiopathogenesis of migraine attacks. This is further supported by the observations that in rats, administration of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide type I receptor (PAC1) antagonists both blocks the development of migraine and significantly reduces nociceptive transmission itself. [

30]. Moreover, PACAP has been shown to act as both a significant anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective factor in brain tissue [

31], acting via stimulation and recovery of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression under pathophysiological conditions [

32,

33]. At lower urinary tract, PACAP increased bladder smooth muscle tone and potentiated electric field stimulation (EFS)-induced contractions [

34]. On the other hand, Hernández et al. have reported that PACAP induced relaxations of the pig urinary bladder neck [

35]. Considering the above-mentioned data, it can be assumed that PACAP plays a number of roles in the lower urinary tract, starting from being involved in the regulation of the detrusor muscle tone, the control of blood flow through the vascular bed of the organ, to acting as a sensory transmitter and, probably, a neuroprotective factor.

It is well-known that GAL is involved in the regulation of many processes within the lower urinary tract. As can be concluded from the available literature, this peptide seems to influence the contractility of detrusor muscle in rat bladder

per se, and moreover, on the other hand, it may also act indirectly, modulating the activity of autonomic ganglia neurons involved in the control of detrusor motility [

36]. It seems that the action of GAL in the lower urinary tract is not limited only to the effect on smooth muscles, but through its ability to modulate the activity of neuromuscular junctions [

37], it may also (co-)regulate the activity of the external urethral sphincter. Furthermore, Honda and colleagues showed that intrathecal administration of this peptide delays the onset of micturition in rats, what may be indicative for an inhibitory role of GAL in the control of micturition reflex at the spinal level [

38]. It is also interesting that GAL may interact with other known afferent cell transmitters: for example, Zvarova et al. reported that GAL may inhibit the actions exerted by PACAP and/or nitric oxide (NO) on bladder-projecting afferent cells [

39]. Furthermore, GAL, when administrated intrathecally in higher doses, blocked the facilitatory effects of SP and CGRP on the excitability of the nociceptive flexor reflex in rats [

40,

41] what implicated that GAL may possess analgesic as well as anti-inflammatory properties [

42]. Considering that PNX was colocalized with GAL in a fair number of neurons, it seems likely that PNX may participate in the regulatory effects described above by modulating GAL function in a currently unknown manner. However, the existence or absence of such interactions remains to be clarified in detail. It should be emphasized that PNX co-occurs in the DRG cells supplying the bladder with transmitters that are believed to induce opposing physiological effects (e.g., SP and CGRP facilitate micturition and nociceptive transmission, while GAL inhibits these phenomena), and further studies are necessary to explain the interactions between PNX and other active substances co-occurring with it in sensory neurons.

In contrast to the substances described above, PNX co-existed with nNOS, CRT and/or SOM only in a marginal number of retrogradely labeled cells.

The role of NO in regulating lower urinary tract function, particularly the pool of molecules released from afferent nerve endings supplying the wall of the bladder and/or urethra, has not yet been sufficiently explained. On the one hand, it has been shown that the major sites of NO release in the rat bladder are afferent nerves and that NO plays an important role in the facilitation of the micturition reflex evoked by noxious chemical irritation of the bladder [

43], participating simultaneously in the initiation of inflammatory responses and triggering painful sensations [

43,

44]. On the other hand, an inhibitory function of NO in the micturition pathway has also been suggested. It was reported that NO may be a regulator of sodium currents in C-type DRG neurons, leading, by suppression of both fast and slow sodium trafficking, to DRG hypoexcitability [

25]. As previously described in the rat, similarly to PNX, nNOS is expressed mainly by small-diameter sensory neurons [

45], and moreover, this enzyme co-expresses very frequently with SP and/or CGRP in the L DRGs [

46]; however, in the present study, only a small percentage of retrogradely labeled PNX

+ cells co-expressed nNOS, even though a significant proportion of these neurons co-expressed SP and/or CGRP. This may suggest that the modulatory effect of PNX on nitrergic pathways regulating bladder functions is rather limited, whereas, considering the frequency of co-existence of PNX with SP and CGRP, it seems to be much more important in the latter case.

At present, the physiological significance of SOM in bladder afferent neurons remains completely unclear. The only hypothesis that can be derived without any doubt from the presented results, analyzing both the number of cells containing it and the patterns of colocalization of this transmitter with other biologically active substances studied in this experiment, is that it most likely constitutes a distinct component of the bladder afferent pathways, the significance of which must be clarified in separate studies. At present, it can only be assumed, based on the available research results, that SOM may be involved in specific modulation of nociceptive transmission [

47], depressing the firing of dorsal horn neurons activated by noxious stimulation [

48], which is confirmed by the observations that SOM may produce an antinociceptive effect [

49], especially in the case of inflammatory reactions of both neurogenic and non-neurogenic origin [

50].

The last protein, previously observed by us in DRG cells associated with the bladder innervation, and whose co-occurrence with PNX we decided to investigate in this study, was CRT. Although the existence of CRT was described already in 1987 [

51], to date there is no precise data allowing to strongly suggest its physiological function in DRG cells involved in the regulatory loops of the micturition process. While it is known that CRT is a protein efficiently modulating both transmembrane Ca

2+ currents and calcium homeostasis in neurons of many parts of brain (e.g., hippocampus, thalamus, neocortex, amygdala) as well as spinal cord regions (especially in the superficial laminae of dorsal horn) [

52,

53], the exact role of this protein in DRG cells remains to be elucidated. Although the ability to modify the presynaptic signaling and Ca

2+ transients by CRT acts as a buffer against excitotoxicity, the expression of this protein seems to be modulated by hypoxic stress, as observed after ischemic episodes [

54], since its overexpression was observed in neurons belonging to the injured brain areas [

55]. Another interesting information is that mechanical and chemical stimuli received and transmitted by DRG neurons induce the expression of CRT in the sensory neurons of dorsal horns of the spinal cord, as can be judged by the increase in the number of CRT

+ cells visible in the spinal cord sections within the superficial Rexted laminae, a phenomenon that was explained by the increased activity of nociceptive transmission under the influence of the above-mentioned stimuli [

56]. However, further dedicated studies are required to reliably establish the role of this calcium-binding protein and its (possible) interactions with PNX and other studied compounds in the regulation of bladder function.

In the course of this study, we also tried to answer the question whether PNX

+ DRG afferent cells, involved in the innervation of the urinary bladder, can colocalize more than two tested substances simultaneously. However, although the analysis of the co-occurrence patterns of the tested substances, performed on consecutive sections, provided a lot of new data (see

Table 12), expanding our knowledge of the chemical coding of bladder sensory neurons, it also raised almost as many new questions, the answers to which require in-depth studies, both qualitative and functional. Although the existence of two clearly separable subpopulations of bladder sensory neurons, distinguished by the expression (or lack thereof) of SOM, seems indisputable, the physiological significance of this subtype of sensory perikaryons, as well as the function(s) that may be assigned to them, remain unknown at present. When the chemical coding patterns of the second, much larger subpopulation of PNX

+ DRG cells conducting sensory information from the bladder wall are analyzed, it is clear that their suite of neurotransmitters represents variant patterns of coexistence of GAL, PACAP, nNOS, and/or CRT with the "core pair" of sensory transmitters, SP and/or CGRP. While the importance of the co-occurrence and simultaneous or sequential release of two neurotransmitters from sensory neurons into the target tissue has been investigated in a number of studies, there are no similar studies on both the physiological importance and the interrelationships of the simultaneous release of more types of neurotransmitter molecules from the same nerve ending into the target tissue. An additional difficulty in interpreting the functional significance of the observed compositions of active substances that may be released into target tissues is both the almost complete ignorance of the latter (in relation to the individual neuronal subtypes identified during these studies) and the lack of data on the receptor "landscape" of potential effector tissues. Unfortunately, it should be stated that as of yet, without further, in-depth functional studies, the multitude of observed patterns of co-occurrence of the studied transmitters makes it impossible to clearly assign individual sensory modalities to individual sub-types of differently coded DRG neurons.

Abbreviations

BDNF - brain-derived neurotrophic factor

Cd - caudal domain

CGRP - calcitonin gene-related peptide

Cn - central domain

Cq – coccygeal

Cr - cranial domain

CRT – calretinin

CY3 - conjugated streptavidin

DH - dorsal horn

DRGs - dorsal root ganglia

EFS - electric field stimulation

FB - fluorescent retrograde tracer Fast Blue

FITC - fluorescein isothiocyanate

FSH - follicle stimulating hormone

GAL – galanin

GnRH - gonadotropin releasing hormone

GPR173 - G protein-coupled receptor 173

IgG - immunoglobulin G

IR – immunoreactive

L – lumbar

LH - luteinizing hormone

Md - middle ganglion area

nNOS - neuronal nitric oxide synthase

NO - nitric oxide

OCT - the ‘optimal cutting temperature’ compound medium

P - peripheral domain

PACAP - pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide

PBS - phosphate-buffered saline

PNS - peripheral nervous system

PNX – Phoenixin

S – sacral

SD - standard deviation

SOM – somatostatin

SP – substance P

UB-PNs - urinary bladder-projecting neurons

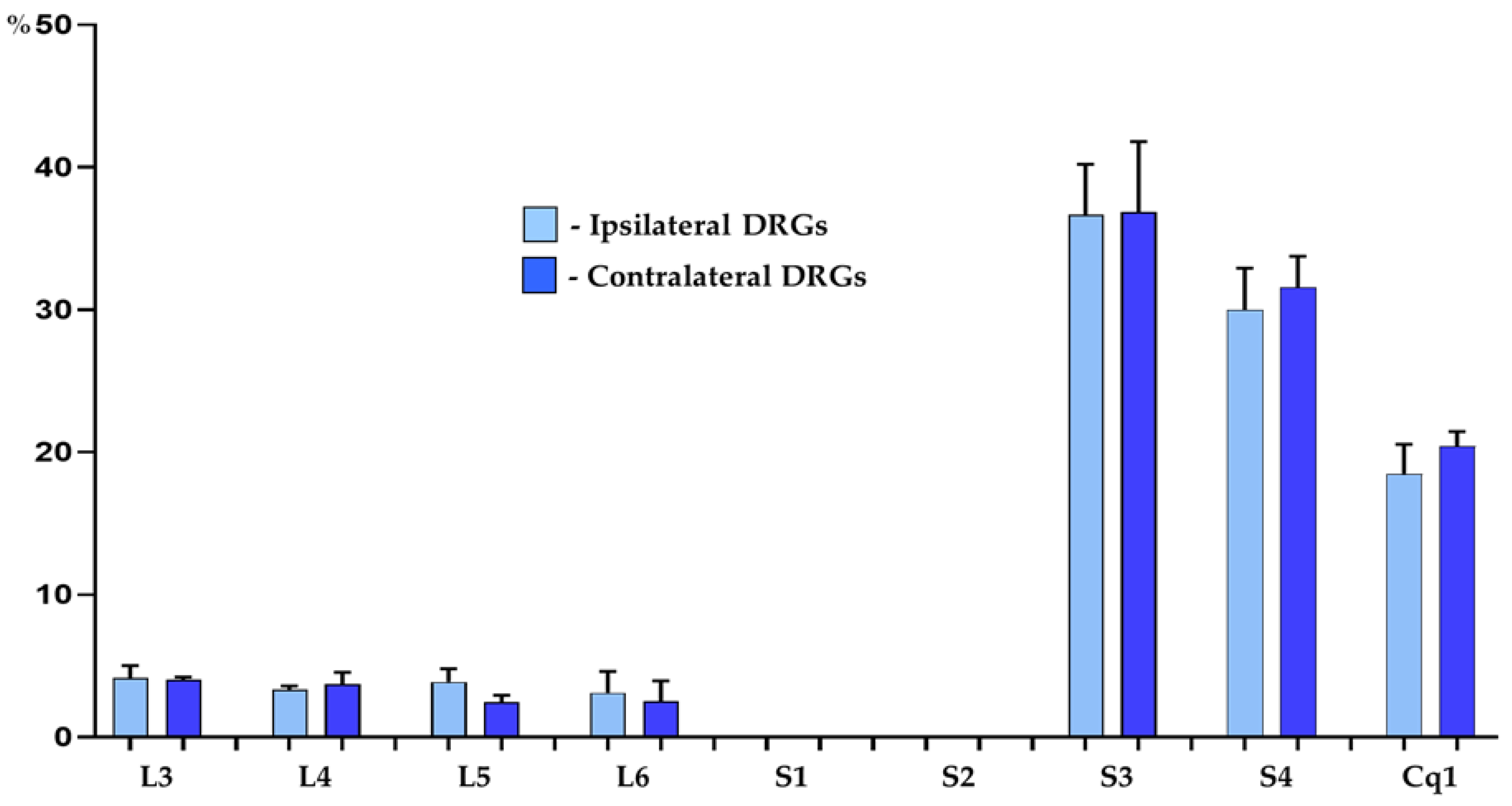

Figure 1.

Bar diagram showing the distribution pattern of FB+ bladder projecting cells in the porcine DRGs ipsi- (light blue bars) and contralateral (dark blue bars) to the sites of tracer injections into the organ wall. The data obtained were pooled in all the animals and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Figure 1.

Bar diagram showing the distribution pattern of FB+ bladder projecting cells in the porcine DRGs ipsi- (light blue bars) and contralateral (dark blue bars) to the sites of tracer injections into the organ wall. The data obtained were pooled in all the animals and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

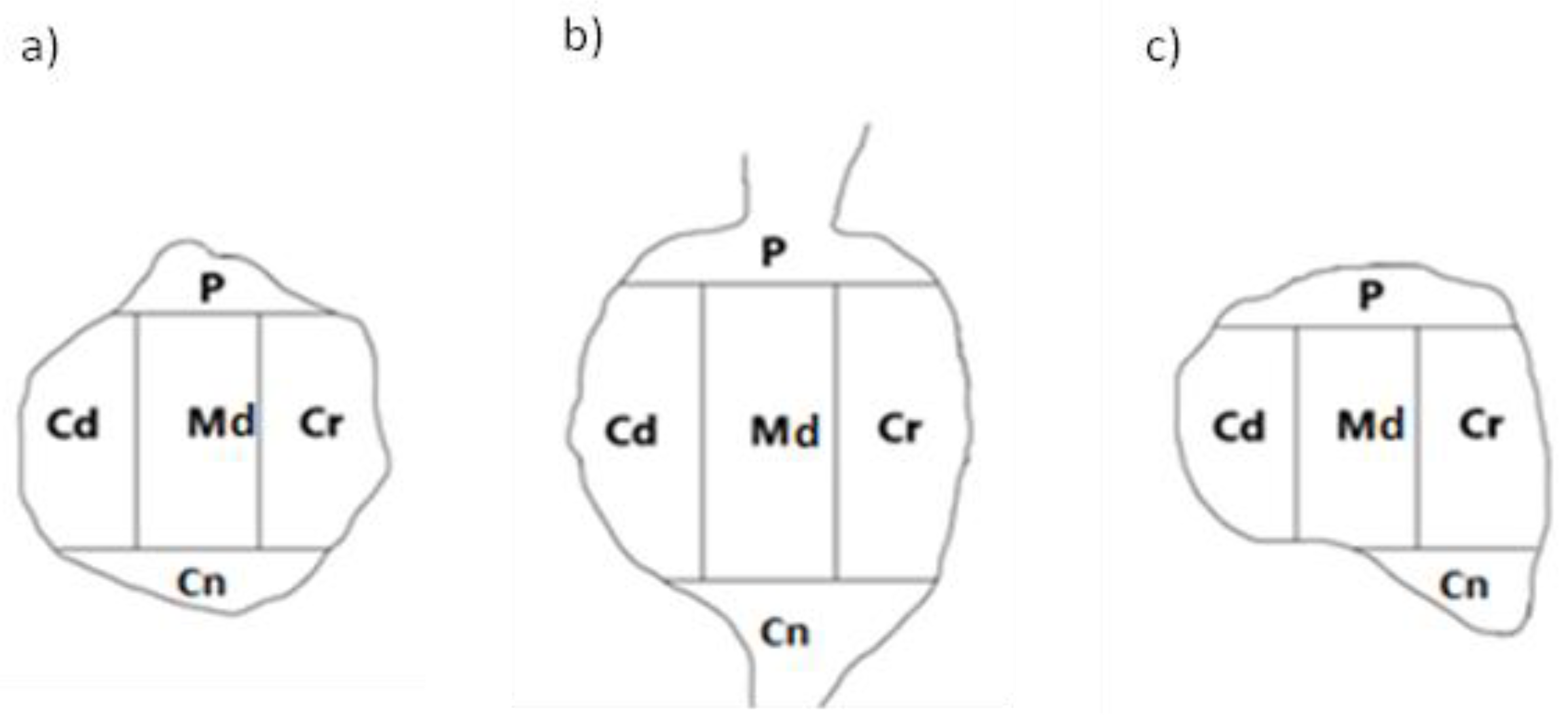

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram of DRG section showing its arbitrary division into topographical domains, in which the occurrence and relative frequency of PNX-containing sensory neurons was studied: P – peripheral domain, Cr – cranial domain, Cd - caudal domain, Cn – central domain of the DRG, Md - middle ganglion area; section from the a) proximal b) middle and c) distal part of the ganglion.

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram of DRG section showing its arbitrary division into topographical domains, in which the occurrence and relative frequency of PNX-containing sensory neurons was studied: P – peripheral domain, Cr – cranial domain, Cd - caudal domain, Cn – central domain of the DRG, Md - middle ganglion area; section from the a) proximal b) middle and c) distal part of the ganglion.

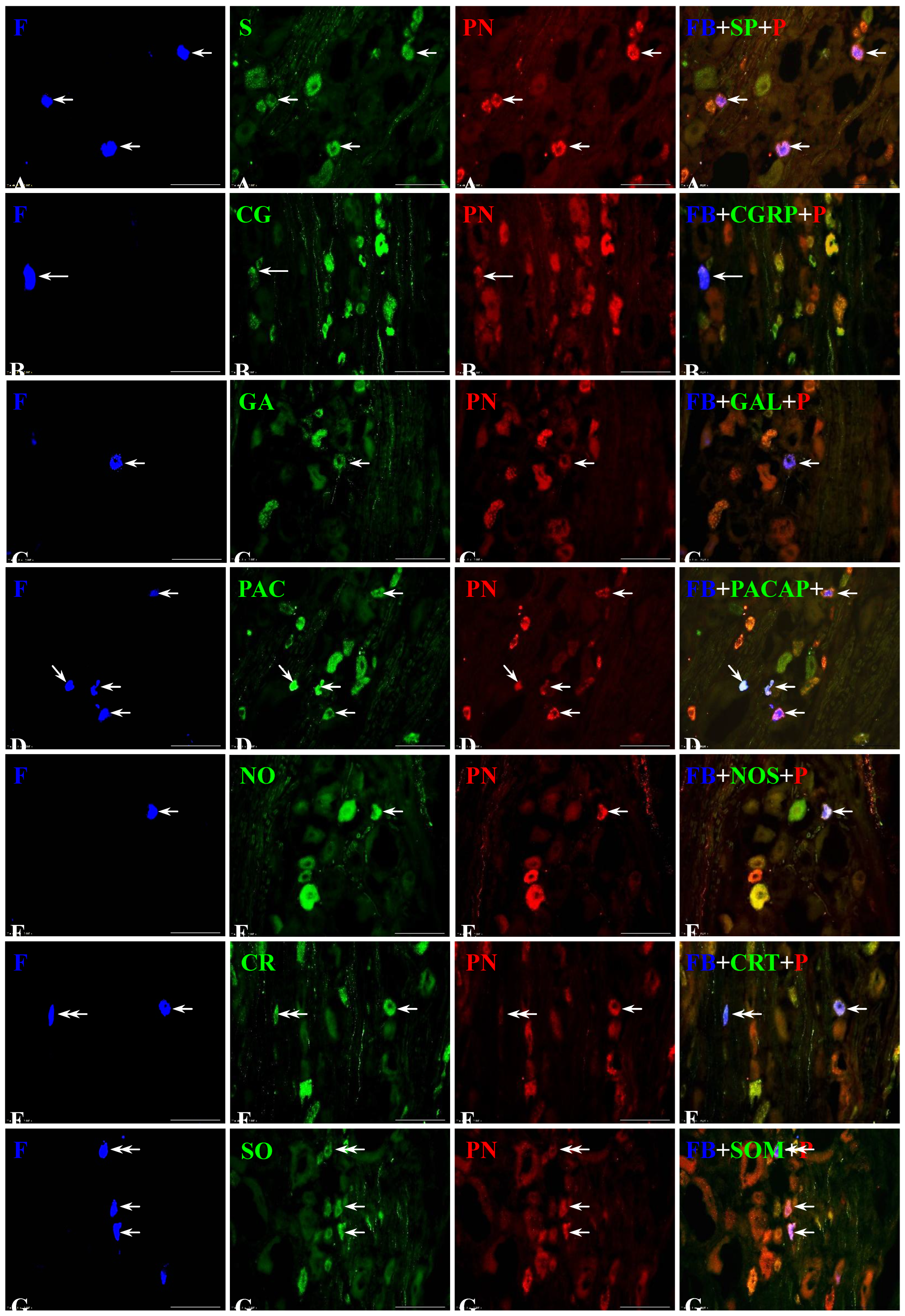

Figure 3.

Representative images of dorsal root ganglia (DRG)-UB-PNs. The images were taken separately from blue (A1, B1, C1, D1, E1, F1, G1), green (A2, B2, C2, D2, E2, F2, G2) and red (A3, B3, C3, D3, E3, F3, G3) fluorescent channels. Pictures A4, B4, C4, D4, E4, F4 and G4 represent images where blue, green and red channels were digitally superimposed. Short arrows represent small-sized FB-positive DRG-UB-PNs (A1, C1, D1, E1, F1, G1) which were simultaneously PNX- (A3, C3, D3, E3, F3, G3) and substance P- (SP; A2), galanin- (GAL; C2), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide- (PACAP; D2), neuronal nitric oxide synthase- (nNOS; E2), calretinin- (CRT; F2) or somatostatin-positive (SOM; G2). Long arrow represents middle-sized FB-positive DRG-UB-PN (B1) containing PNX (B3) and CGRP (B2). Double arrows represent small-sized FB-positive DRG-UB-PNs (F1, G1) which contained CRT (F2) or SOM (G2) and were simultaneously PNX-negative (F3, G3). Bar in all the images - 100 μm.

Figure 3.

Representative images of dorsal root ganglia (DRG)-UB-PNs. The images were taken separately from blue (A1, B1, C1, D1, E1, F1, G1), green (A2, B2, C2, D2, E2, F2, G2) and red (A3, B3, C3, D3, E3, F3, G3) fluorescent channels. Pictures A4, B4, C4, D4, E4, F4 and G4 represent images where blue, green and red channels were digitally superimposed. Short arrows represent small-sized FB-positive DRG-UB-PNs (A1, C1, D1, E1, F1, G1) which were simultaneously PNX- (A3, C3, D3, E3, F3, G3) and substance P- (SP; A2), galanin- (GAL; C2), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide- (PACAP; D2), neuronal nitric oxide synthase- (nNOS; E2), calretinin- (CRT; F2) or somatostatin-positive (SOM; G2). Long arrow represents middle-sized FB-positive DRG-UB-PN (B1) containing PNX (B3) and CGRP (B2). Double arrows represent small-sized FB-positive DRG-UB-PNs (F1, G1) which contained CRT (F2) or SOM (G2) and were simultaneously PNX-negative (F3, G3). Bar in all the images - 100 μm.

Table 1.

List of primary antisera and secondary reagents used in the study: CGRP - calcitonin gene-related peptide, CRT - calretinin, GAL - galanin, nNOS - neuronal nitric oxide synthase, PACAP - pituitary adenylate synthase-activating polypeptide, PNX - phoenixin, SOM - somatostatin, SP - substance P, FITC - fluorescein isothiocyanate, CY3 - streptavidin-conjugated.

Table 1.

List of primary antisera and secondary reagents used in the study: CGRP - calcitonin gene-related peptide, CRT - calretinin, GAL - galanin, nNOS - neuronal nitric oxide synthase, PACAP - pituitary adenylate synthase-activating polypeptide, PNX - phoenixin, SOM - somatostatin, SP - substance P, FITC - fluorescein isothiocyanate, CY3 - streptavidin-conjugated.

| Antigen |

Code |

Dilution |

Host |

Supplier |

| Primary antibodies |

| CGRP |

PC205L |

1:9000 |

Rabbit |

Merck Millipore; Temecula; CA; USA |

| CRT |

6B3 |

1:2000 |

Mouse |

SWANT, Switzerland |

| GAL |

AB5909 |

1:4000 |

Rabbit |

Merck Millipore; Temecula; CA; USA |

| nNOS |

N2280 |

1:200 |

Mouse |

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| PACAP |

T-4465 |

1:15000 |

Rabbit |

Peninsula; San Carlos; CA; USA; |

| PNX |

H-079-01 |

1:7000 |

Rabbit |

Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc, Burlingame, CA, USA, |

| SOM |

MAB 354 |

1:50 |

Rat |

Merck Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA |

| SP |

8450-0004 |

1:200 |

Rat |

Bio-Rad, Kidlington, UK |

| Secondary reagents |

| Biotinylated anti-rabbit immunoglobulins |

E 0432 |

1:1000 |

Goat |

Dako; Hamburg; Germany |

| CY3-conjugated streptavidin |

711-165-152 |

1:12000 |

- |

Jackson I.R.; West Grove; PA; USA |

| FITC-conjugated anti-rat IgG |

712-095-150 |

1:400 |

Donkey |

Jackson I.R.; West Grove; PA; USA |

| FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG |

715-096-151 |

1:600 |

Donkey |

Jackson I.R.; West Grove; PA; USA |

Table 2.

List of antigens used in pre-absorption test.

Table 2.

List of antigens used in pre-absorption test.

| Antigen |

Code |

Dilution |

Supplier |

| CGRP |

T-4030 |

1:800 |

Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA, USA |

| CRT |

Lot No.: 22 |

1:2000 |

SWANT, Switzerland |

| GAL |

T-4862 |

1:1500 |

Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA, USA |

| nNOS |

N3033 |

1:200 |

Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| PACAP |

A9808 |

1:1000 |

Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| PNX |

079-01 |

1:7000 |

Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc; Burlingame; Kalifornia; USA |

| SOM |

S9129 |

1:50 |

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| SP |

S6883 |

1:200 |

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

Table 3.

Percentages of Fast Blue-positive (FB+) neurons located in the individual lumbar (L), sacral (S) and coccygeal (Cq) dorsal root ganglia (DRGs). The obtained data were pooled in all the animals and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Table 3.

Percentages of Fast Blue-positive (FB+) neurons located in the individual lumbar (L), sacral (S) and coccygeal (Cq) dorsal root ganglia (DRGs). The obtained data were pooled in all the animals and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), referring to the number of animals (N=6).

| FB+ neurons |

L3

% |

L4

% |

L5

% |

L6

% |

S3

% |

S4

% |

Cq1

% |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

3.5 ± 0.4 |

2.4 ± 0.4 |

3.4 ± 0.5 |

2.9 ± 0.8 |

33.3 ± 2.0 |

30.7 ± 1.6 |

23.8 ± 1.2 |

| Contralateral DRGs |

3.8 ± 0.1 |

3.0 ± 0.1 |

3.7 ± 0.2 |

3.2 ± 0.8 |

33.5 ± 2.8 |

31.3 ± 1.2 |

21.5 ± 0.6 |

Table 4.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations located in the ipsilateral and the contralateral DRG studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Table 4.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations located in the ipsilateral and the contralateral DRG studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

| DRG subdomain |

P |

Cr |

Cd |

Cn |

Md |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

12.2 ± 2.1% |

20.2 ± 4.2% |

36.7 ± 3.6% |

8.6 ± 0.8% |

22.3 ± 1.6% |

| Contralateral DRGs |

24.8 ± 1.6% |

13.2 ± 1.2% |

26.5 ± 1.5% |

17.4 ± 1.4% |

18.1 ± 4.3% |

Table 5.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing SP and located in the ipsilateral and the contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Table 5.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing SP and located in the ipsilateral and the contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

| DRG subdomain |

P |

Cr |

Cd |

Cn |

Md |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

15.1 ± 4.9% |

26.7 ± 6.0% |

36.3 ± 6.9% |

7.7 ± 2.9% |

14.2 ± 1.8% |

| Contralateral DRGs |

32.8 ± 2.3% |

13.3 ± 4.6% |

31.9 ± 1.9% |

7.9 ± 1.6% |

14.1 ± 3.0% |

Table 6.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing CGRP and located in the ipsi- and contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Table 6.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing CGRP and located in the ipsi- and contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

| DRG subdomain |

P |

Cr |

Cd |

Cn |

Md |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

0% |

37.9 ± 2.2% |

62.1 ± 2.2% |

0% |

0% |

| Contralateral DRGs |

0% |

44.2 ± 5.8% |

55.8 ± 5.8% |

0% |

0% |

Table 7.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing GAL and located in the ipsi- and contralateral studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Table 7.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing GAL and located in the ipsi- and contralateral studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

| DRG subdomain |

P |

Cr |

Cd |

Cn |

Md |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

13.7 ± 2.8% |

23.7 ± 6.0% |

36.5 ± 9.0% |

9.5 ± 1.9% |

16.6 ± 3.2% |

| Contralateral DRGs |

15.5 ± 1.3% |

11.4 ± 3.3% |

42.9 ± 2.3% |

5.6 ± 4.8% |

24.6 ± 3.3% |

Table 8.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing PACAP and located in the ipsi- and contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Table 8.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing PACAP and located in the ipsi- and contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

| DRG subdomain |

P |

Cr |

Cd |

Cn |

Md |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

10.1 ± 5.7% |

15.9 ± 1.4% |

32.6 ± 2.7% |

11.1 ± 3.7% |

30.3 ± 2.7% |

| Contralateral DRGs |

0% |

0% |

79.9 ± 7.6% |

0% |

20.1 ± 7.9% |

Table 9.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing nNOS and located in the ipsilateral and contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Table 9.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing nNOS and located in the ipsilateral and contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

| DRG subdomain |

P |

Cr |

Cd |

Cn |

Md |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

7.3 ± 1.6% |

22.9 ± 4.8% |

33.8 ± 3.5% |

11.7 ± 0.8% |

24.3 ± 3.6% |

| Contralateral DRGs |

29.1 ± 1.5% |

15.4 ± 3.5% |

30.6 ± 2.1% |

8.8 ± 1.1% |

16.1 ± 8.7% |

| DRG subdomain |

P |

Cr |

Cd |

Cn |

Md |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

7.3 ± 1.6% |

22.9 ± 4.8% |

33.8 ± 3.5% |

11.7 ± 0.8% |

24.3 ± 3.6% |

| Contralateral DRGs |

29.1 ± 1.5% |

15.4 ± 3.5% |

30.6 ± 2.1% |

8.8 ± 1.1% |

16.1 ± 8.7% |

Table 10.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing CRT and located in the ipsi- and contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Table 10.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing CRT and located in the ipsi- and contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

| DRG subdomain |

P |

Cr |

Cd |

Cn |

Md |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

10.5 ± 9.1% |

0% |

54.7 ± 10.8% |

5.2 ± 4.5% |

29.6 ± 4.5% |

| Contralateral DRGs |

0% |

0% |

96.3 ± 3.7% |

0% |

3.7 ± 3.7% |

Table 11.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing SOM and located in the ipsilateral and the contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

Table 11.

Percentages of intraganglionic distribution pattern of FB+/PNX+ neuronal populations containing SOM and located in the ipsilateral and the contralateral DRGs studied. Data obtained from all studied animals were pooled and presented as mean ± SD, referring to the number of animals (N=6).

| DRG subdomain |

P |

Cr |

Cd |

Cn |

Md |

| Ipsilateral DRGs |

11.5 ± 5.1% |

32.8 ± 4.0% |

55.7 ± 8.0% |

0% |

0% |

| Contralateral DRGs |

4.1 ± 5.5% |

0% |

95.9 ± 5.5% |

0% |

0% |

Table 12.

The relative numbers of individual, differently neurochemically coded, subpopulations of PNX+ sensory neurons supplying the urinary bladder, as determined by analysis of consecutive serial sections of the studied ganglia.

Table 12.

The relative numbers of individual, differently neurochemically coded, subpopulations of PNX+ sensory neurons supplying the urinary bladder, as determined by analysis of consecutive serial sections of the studied ganglia.

| Collocation Patterns of PNX with Different Neurotransmitters in the Bladder DRG Neurons |

% |

| PNX+/SP+ |

14.6 ± 0.9 |

| PNX+/GAL+ |

3.7 ± 0.8 |

| PNX+/CGRP+ |

4.2 ± 0.8 |

| PNX+/SP+/PACAP+ |

3.5 ± 1.1 |

| PNX+/SP+/GAL+ |

6.1 ± 1.2 |

| PNX+/SP+/CGRP+ |

4.3 ± 0.8 |

| PNX+/SP+/CRT+ |

0.7 ± 0.5 |

| PNX+/SP+/NOS+ |

0.8 ± 0.9 |

| PNX+/GAL+/CGRP+ |

7.2 ± 0.8 |

| PNX+/NOS+/PACAP+ |

1.9 ± 1.1 |

| PNX+/GAL+/PACAP+ |

3.5 ± 1.9 |

| PNX+/CRT+/CGRP+ |

3.7 ± 1.3 |

| PNX+/PACAP+/CGRP+ |

2.2 ± 1.4 |

| PNX+/SP+/CGRP+/PACAP+ |

6.7 ± 2.1 |

| PNX+/SP+/GAL+/PACAP+ |

3.2 ± 1.5 |

| PNX+/SP+/GAL+/CGRP+ |

4.4 ± 0.6 |

| PNX+/SP+/GAL+/CRT+ |

8.1 ± 1.8 |

| PNX+/SP+/CGRP+/CRT+ |

0.7 ± 0.2 |

| PNX+/SP+/NOS+/PACAP+ |

2.2 ± 0.8 |

| PNX+/SP+/SOM+/CGRP+ |

0.7 ± 0.7 |

| PNX+/NOS+/PACAP+/CGRP+ |

3.0 ± 1.3 |

| PNX+/SP+/PACAP+/CRT+/CGRP+ |

2.2 ± 0.9 |

| PNX+/SP+/GAL+/PACAP+/CGRP+ |

8.5 ± 2.8 |

| PNX+/SP+/NOS+/PACAP+/CGRP+ |

1.2 ± 0.7 |

| PNX+/SP+/GAL+/NOS+/CGRP+ |

0.6 ± 0.3 |

| PNX+/SP+/SOM+/GAL+/PACAP+/CGRP+ |

2.1 ± 0.8 |