1. Introduction

Despite proceedings in cancer care 50% of cancer patients die [

1]. However, due to proceedings of cancer care many of them survive with cancer for longer times than in the past. Nonetheless, patients with haematological malignancies use less often specialized palliative care compared to patients with solid tumours [

2,

3,

4,

5].

Palliative medicine is a concept of care for patients with incurable diseases. It is based on Cicely Saunder’s Total Pain concept, which embraces not only the physical dimension of suffering, but also the social, spiritual, and psychological dimensions [

6]. Thus, palliative care uses an interdisciplinary and multiprofessional approach that addresses patients, and their relatives and other informal care givers [

7].

As the concept aims to accompany people with incurable diseases, it includes the end-of-life. Although all medical disciplines deal with it, palliative medicine is the one that is associated with death and dying in the public perception. Nonetheless patients and relatives benefit essentially from early integrated palliative care months and years preceding death. But the explicit acceptance of the end-of-life is a hallmark of palliative care, which may frequently lead to denial if it is offered early or in a context of uncertain predictability.

The latter is a frequent argument in haematologic malignancies (HM) compared to solid tumours. In acute leukaemia, at its onset, some patients move between death and survival. In situations of relapse or chronic HM courses the response to therapies is uncertain. Besides the uncertain predictability many haematologists prefer to deliver palliative care on their own. Thus, it is important to develop best practice models to identify early enough haemato-oncology patients approaching the end-of-life to provide palliative care when it is appropriate.

The ‘Surprise’-Question ‘Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months?’ is a simple and feasible instrument for intuitive estimation of mortality in patients with different kinds of advanced disease [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] and aims to improve prognostic awareness in physicians [

9]. However, little is known about the use of the ‘Surprise’-Question in haematological malignancies [

17].

The aim of this study was to test the feasibility of the ‘Surprise’-Question in haemato-oncology as a facilitator of early integration of palliative care by determination of the face validity and observation of the application process and assessment of survival at 12 months. Exploration of the applying physicians’ experience with the instrument revealed the potential of the ‘Surprise’-Question to involve the haemato-oncologists’ intuition into the patient assessment [

17]. We decided to revisit and publish our quantitative findings from 2014, because the accuracy of the ‘Surprise’-Question in identifying people with poor prognoses has been questioned [

18,

19,

20] and persistent lack of palliative mortality prediction tools in haematology [

21,

22,

23]. Here we report the test results for the ‘Surprise’-Question applied in the haemato-oncology outpatient clinic.

2. Materials and Methods

We performed a prospective cohort study and descriptive analysis of the validity of the ‘Surprise’-Question with integrated qualitative analysis of experiences of physicians who applied the instrument.

Participant Selection and Study Procedures

The setting was the haemato-oncology outpatient clinic situated at a university hospital in Germany with an average of 1100 patients each quarter. From October 1st through December 31st 2012 doctors where asked to answer the ‘Surprise’-Question “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months” with “No” or “Yes” for each cancer patient on their daily appointment-list. In case of the answer: “No, I would not be surprised”, physicians were further asked to indicate if the expected survival time could be even less than 3 months. Patients who presented repeatedly were assessed at each visit. Reassessment for survival status at 3 and 12 months was done by chart review at 18 months after inclusion. Included for analysis were patients with current malignant disease; exclusion criteria were non-malignant haematological diseases, and visits for diagnostic investigation with benign result, e.g. lymphadenopathy. The appointment lists were checked on a daily base and matched with the returned lists to avoid selection bias.

The quantitative part of this study was assessed as quality improvement initiative (Ethics Committee of the Medical Council of the province of Rhineland-Palatine).

Interpretation of the Test Accuracy

The terminology of test qualities is challenging. The ‘No’- response to the ‘Surprise’-Question presents a ‘positive’ response, which means an estimate for the patient to possibly die within 12 months, ‘Yes’ means a prognostic estimate beyond one year. Sensitivity in this context refers to the probability to detect patients by ‘Surprise’-Question who will die within 1 year; specificity reflects the ability of the ‘Surprise’-Question to identify patients who will survive 12 months. The positive predictive value (PPV) reflects what happened, i.e. the proportion of patients who died within one year when the physician estimated ‘No, not surprised’; the negative predictive value (NPV) indicates the probability of a patient assessed ’Yes’ to survive 1 year. Area under the curve (AUROC) or c-statistics value compares the number of correct estimates (sensitivity) against the false (1-specificity). It helps to differentiate if physicians’ ‘Surprise’-Question estimate was better than chance at recognizing a patient nearing end of life. A score of 0.5 means the ‘Surprise’-Question estimate was equal to chance, a score of 1.0 means that random coincidence seems excluded. The Cohen’s kappa describes the concordance between physician estimate and actual outcome one year after. Kaplan-Meier curves describe the ability of the ‘Surprise’-Question to discriminate patients in two groups for risk of death. The odds ratio (OR) describes the probability of how many times more frequent an event happened under a defined condition, e.g. patients dying in the ‘No’-group compared to the ‘Yes’-group.

Statistical Methods

The study population with its demographic and clinical characteristics was described with appropriate statistical parameters (e.g. numbers and frequencies for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables). In order to compare the answer to the ‘Surprise’-Question and the actual outcome after 12 months, cross tabulation was applied for haematological and oncological diseases. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values with exact 95% confidence intervals were computed. Cohen’s kappa, c-statistic, and Pearson-Clopper test with confidence intervals were evaluated. To compare survival experience between patients with assumed life expectancy up to 3 months, more than 3 months, but up to 12 months and more than 12 months we also computed Kaplan-Meier estimates and performed a log-rank test. We used logistic regression to determine which factors could explain a realistic assessment of life expectancy. This was done in a case-control view: “cases” were patients for whom outcome and previous assessment of life expectancy agreed; “controls” were those with disagreement of outcome and previous assessment. Explanatory factors considered were: death within 12 months of the initial estimate, time between initial estimate and death in case of death, physician in charge, age and gender of patient, type of disease (solid tumor vs haemato-oncological disease) and intention of treatment (curative vs palliative). Patients who were assessed by doctors who saw 3 patients or less and patients for whom the assessing physicians was not documented were excluded from this analysis.

We used SAS Version 9.4 and SPSS Version 23.

3. Results

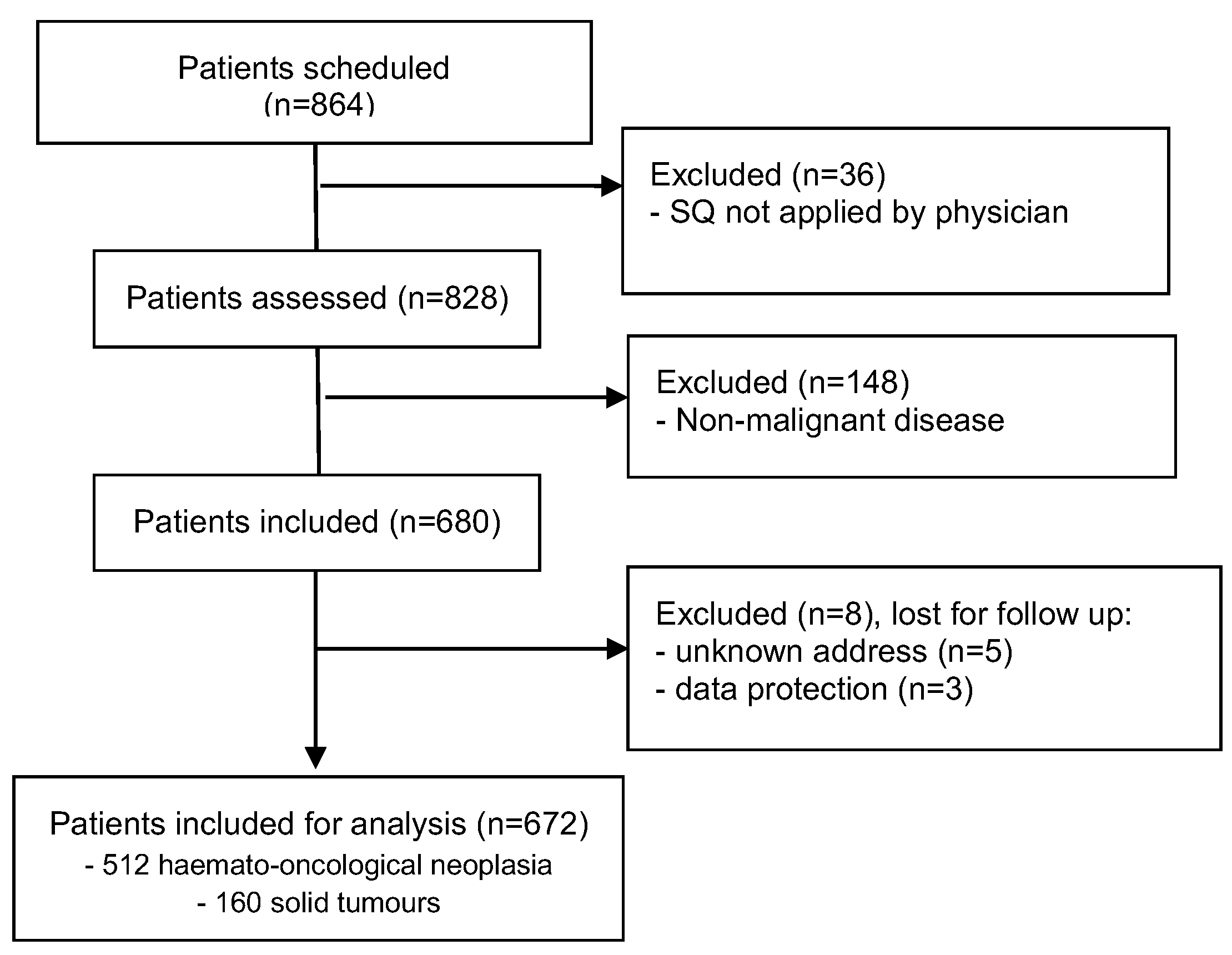

A total of 864 patients from the outpatient clinics for haematology and oncology were assessed for eligibility within 3 months. Thirty-six patients were not screened with the ‘Surprise’-Question by their doctors for organisational reasons, 148 patients were excluded because of a non-malignant diagnosis, resulting in 680 included for follow up. 8 patients were lost for follow-up. 672 patients were eligible for analysis 3 and 12 months after survival estimate by ‘Surprise’-Question, (

Figure 1).

Most patients were diagnosed with haematological malignancy (n=512; 76.2%), mean age 63 years (SD ± 14, range 19 - 90), 59.4 % men. 160 patients suffered from solid tumours, mainly lung cancer (43.1 %), 65 % men, mean age 61 (SD ± 15, range 14 - 89). The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants are shown in

Table 1.

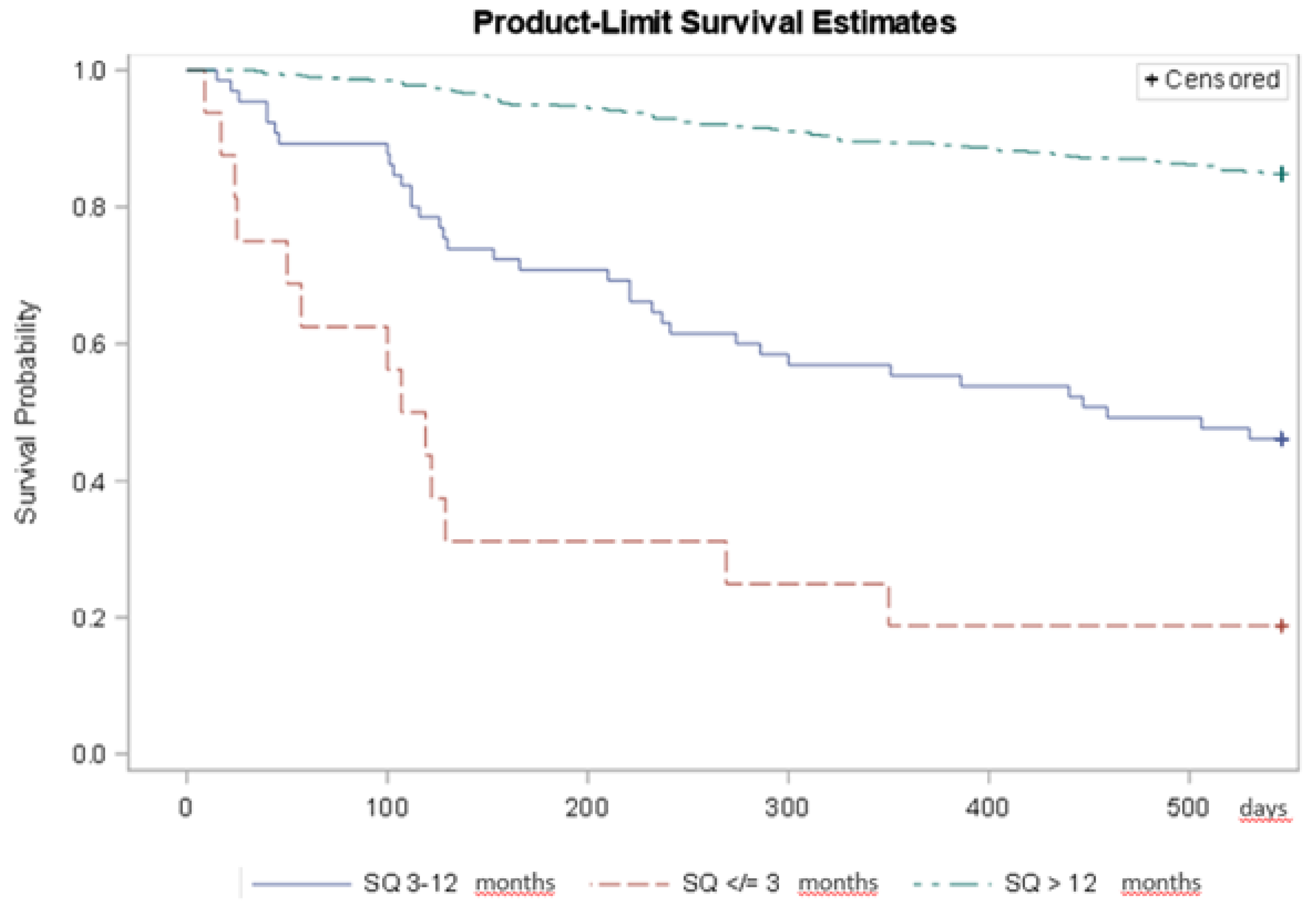

3.1. Survival of Patients Stratified by Answer to the ‘Surprise’-Question

Median survival for those with an assumed life expectancy up to 3 months was 113 days, 459 days for those with assumed life expectancy of more than 3 months up to 12 months, and for those with assumed life expectancy of more than 12 months the median could not be observed, i.e. was greater than 546 days. The log-rank test indicated different survival experience between groups (p < 0.0001). Patients with haematological malignancies in the ‘No’-group were times 5.7 (95% CI: 3.0; 10.8) likelier to die within one year compared to those in the ‘Yes’-group, and this was also true for patients with solid tumours, 4.3 (95% CI: 2.5;7.5) (

Table 2;

Figure 2).

3.2. The ‘Surprise’-Question as Diagnostic Tool to Identify Patients with Limited Life Expectancy

We compared the mortality of patients for whom the ‘Surprise’-Question had a positive answer, i. e. the treating physician would not be surprised if the patient died within 12 months (‘No’-group), with those patients for whom the ‘Surprise’-Question had a negative answer (‘Yes’-group). Considerably less haematology patients (n=31, 6.1 %) were assessed for the ‘No’-group compared with oncology patients (n=50, 31.3 %).

Of 81 patients who were deemed to have a life expectancy not beyond 12 months, 42 (52%) died within 12 months (positive predictive value PPV 0.52, 95% CI: [0.40; 0.63]), 12 out of 31 haematology patients (PPV 0.39), and 30/50 oncology patients (PPV 0.60). In contrast, 591 patients were expected to survive beyond 12 months, of whom 528 survived (89%, negative predictive value NPV 0.89, 95% CI: [0.87; 0.92]), 0.91 for haematology and 0.80 for oncology patients. The NPV, indicating the probability of a patient assessed ’Yes’ to survive 1 year, was higher than the PPV in both groups, which can be defined as implicit safeguard to prevent people with higher life expectancy from too early overprovision with palliative care (

Table 2). However, many more haematology patients than oncology patients died although estimated to survive one year (false negative 77%, 41/53 vs. 42%, 22/52).

When comparing the answer to the ‘Surprise’-Question between the 105 patients who died within 12 months and the 567 patients who survived, we found a sensitivity of 0.40 (95% CI: [0.31; 0.50]) and a specificity of 0.93 (95% CI: [0.91; 0.95]). The sensitivity was 0.23 in patients with haematological malignancies and 0.58 in patients with solid tumours. The lower sensitivity in the group of haematological patients also reflects the physicians’ tendency to answer ‘Yes, surprised if this patient died’ (94 %) (

Table 2). We observed a trend to improved sensitivity and PPV comparing first and last estimates when patients were assessed repeatedly. This might reflect the decreasing interval to the actual time of death, or the increasing hits known from repeated testing (

Table 2).

The c-statistic value was 0.66 for estimates in haematology and 0.75 in solid tumours indicating moderate accuracy. Cohen’s kappa was 0.37 (95% CI: [0.27; 0.46]), indicating fair agreement between physician estimate and actual outcome [

24]. In summary, patients of the

„No“-group had a many times greater risk to die within 1 year compared to patients of the „Yes“-group. The accuracy of survival estimate with the ‘Surprise’-Question was better in patients with solid tumours compared to those with haematological malignancies.

3.3. Which Factors Contribute to a Realistic Assessment of Life Expectancy?

We fitted a logistic regression model with dependent variable agreement of assessment and outcome and explanatory variables

death within 12 months of initial estimate

time between initial estimate and death in case of death

assessing physician

age and gender of patient

type of disease (solid tumor vs haemato-oncological disease)

intention of treatment (curative vs palliative)

We found significant effects of death within 12 months of initial estimate (p=0.005), time between initial estimate and death in case of death (p < 0.001) and assessing physician (p=0.0096) (

Table 3). Age and gender of patients, type of disease and intention of treatment did not show an association with agreement of estimate and outcome. For patients dying within 12 months the odds ratio (OR) of having a realistic assessment was 0.012 (95% CI: [0.004; 0.036]), which means realistic assessment was obtained more easily in patients who survived. Time between initial assessment and death resulted in an OR of 0.991 per day (95% CI: [0.986; 0.996]), i.e. a realistic assessment was more likely in patients who died soon after the assessment.

There were some differences in the amount of agreement of initial assessment and outcome between physicians. While the ‘Surprise’-Question estimate by doctor 4 agreed with the outcome in 74/79 (94%) cases, others provided less realistic assessments. Odd Ratios compared to doctor 4 ranged between 0.117 (95% CI: [0.027; 0.502]) to 0.501 (95% CI: [0.097; 2.592]). The accuracy of the ‘Surprise’-Question estimate depended on the closeness to death, and on the assessing physician rather than training while on study or the patients’ category of illness.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to examine the ‘Surprise’-Question “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months” in haemato-oncology outpatients. We observed the use of the ‘Surprise’-Question in outpatient settings at a university hospital and compared estimates for haematology patients with those for patients with solid tumours. We found that the ‘Surprise’-Question-answers well discriminate between patients at higher (‘No’) vs. low (‘Yes’) risk of 1-year mortality as others did before us [

9,

10,

18,

19,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Test accuracy was better in oncology compared to haematology patients and increased between first and last ‘Surprise’-Question estimate, but this effect was attributable to the assessing physician and proximity to death rather than disease category.

The application of the ‘Surprise’-Question was feasible, but its usability for integration of palliative care is ambiguous. Study conditions facilitated regular reflection about individual patient survival, which may not be the case in standard clinical operation mode. Further, the integrated interviews with the applying haemato-oncology specialists revealed a lack of consequences from a ‘No’-answer (indicating patients supposed to be in their last year of life), which undermine the function of the instrument when applied by physicians not trained in palliative care [

17].

In the Gold Standard Framework and SPICT [

29], the ‘Surprise’-Question is used to rise attention for further prognostic, symptom, and psychosocial assessment in the general practice. We and others combined the ‘Surprise’-Question as a screening instrument for further PC needs assessment in the haemato-oncology population, which revealed a substantial part of patients with severe unmet burden that could be alleviated by integration of palliative care [

30,

31]. In a cohort of 101 haematology and 46 solid tumour inpatients 68.7% were correctly estimated to die within 12 months, which was better than in our cohort (52 %). In contrast to our results, their subgroup-analysis showed no PPV-difference between groups (haematological malignancies: 69/101, 68.3% vs. solid tumours 32/46, 69.6%; p=0.88) [

31]. However, this result may be in concordance with our observation that the ‘Surprise’-Question estimates were more accurate when closer to death, because Hudson et al observed hospitalised patients who might have been in a more severe status of illness than outpatients of our cohort: 42.9% of those requiring inpatient care died during the index and the following admission. Nevertheless, an alternative reason for the improved test-accuracy in our study close to the actual time of death may be increasing hits known from repeated testing or closer observation of the patient. Also, others found better accuracy of the ‘Surprise’-Question estimates close to death. Gupta et al. [

13] found in their meta-analysis from 56 studies with nearly 69,000 patients that the test accuracy of the ‘Surprise’-Question improved with the frequency of testing and a short time frame. They also described the positive impact of the physician experience on the ‘Surprise’-Question test accuracy that we observed in our cohort. The risk that the ‘Surprise’-Question might reflect the predictive skills of the applying healthcare practitioner rather than the remaining lifespan was intensively discussed by Davis et al. [

16]. But the benefit of the ‘Surprise’-Question for haematology patients might be to inspire their physicians to think of and train prognosis at all [

17].

The question is whether the exact prognosis is rather relevant under circumstances when quality of life (QoL) is most relevant – even more knowing the positive effect of specialized palliative care on QoL and in some cases even survival [

32,

33]. Nevertheless, the better accuracy of the ‘Surprise’-Question in identifying patients surviving than those dying within 12 months may prevent from too early end-of-life care in those patients, who may only need improved supportive care. However, palliative care should not be misinterpreted as end-of-life-care only, which is an issue in haematologists who are the first to inform their patients correctly about palliative care [

5,

34,

35]. In this context, the interpretation of Mahes at al. [

15] may be considered. Similarly to our results they found the ‘Surprise’-Question to help identify patients with Parkinson’s disease surviving the next 12 months. Nevertheless, they interpreted that this function facilitates to identify patients with palliative care needs early enough to provide appropriate care in time.

Limitations of our study in terms of generalizability and currency need to be discussed. This was a single centre study in an academic hospital setting. Yet, oncology care is comparable in terms of patient characteristics in outpatient settings between academic and non-academic and even between health-care systems. However, the physician characteristics may vary with greater continuity in patient care and a higher proportion of experienced staff in non-academic settings providing specialised haematology and oncology care. Our data is older, but not outdated. The ongoing debate on the integration of palliative care in haematology shows the continuing relevance of the topic [

5,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Nevertheless, we hope for an improved understanding in future generations of specialists caring for patients with haematological malignancies in terms of palliative care, because it is a mandatory subject in undergraduate medical education in Germany since 2013 [

40,

41].

5. Conclusions

As any other instrument the handling of the ‘Surprise’-Question needs training and practice. Our data suggest that the greatest accuracy of survival estimation occurs when the string of intuition has a sounding board from medical experience. The impact of characteristics from the assessing physicians and the individual doctor-patient relation should be further explored to inform training with the ‘Surprise’-Question. However, the ability of the ‘Surprise’-Question to identify patients with longer survival may be an interesting approach to combine the activation of reflective intuition with the doctors’ natural preference for positive prediction. Further, a tool does not only need a user but a purpose. The impact of basic palliative care training and availability of specialised palliative care services on usability of the ‘Surprise’-Question needs to be examined. As the haematologists’ self-image embraces provision of palliative care for their patients and relatives, haematologic malignancies should be considered with priority.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization,M.W. and C.G.; methodology, C.G. and I.S.; software, I.S.; validation, C.G. and I.S.; formal analysis, I.S.; investigation, C.G.; resources, M.W.; data curation, C.G. and I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G. and I.S.; writing—review and editing, C.G.; visualization, C.G. and I.S.; supervision, C.G.; project administration, C.G.; funding acquisition, -. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The quantitative part of the study was classified as quality improvement, and used pre-existing data respectively; we received exemption from local ethic committee. The qualitative study protocol was approved by the King’s College research ethics committee (Reference Number LRU14/ 150715, May 5th, 2015) and the Ethics Committee of the Medical Council of the province of Rhineland-Palatine (837.103.15 (9871), April 2nd , 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the administrative and medical staff of the haematology outpatient clinic and of the bone marrow transplant outpatient clinic. Special thanks to Luisa Halbe who essentially supported the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. .

References

- Cancer IAfRo. Prognostizierte Anzahl von Krebstodesfällen weltweit im Zeitraum von 2022 bis 2050 [Graph] Statista2024 [Available from: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1201305/umfrage/prognostizierte-anzahl-von-krebstodesfaellen-weltweit/.

- Howell, D.A.; Roman, E.; Cox, H.; Smith, A.G.; Patmore, R.; Garry, A.C.; Howard, M.R. Destined to die in hospital? Systematic review and meta-analysis of place of death in haematological malignancy. BMC Palliative Care. 2010, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, D.A.; Shellens, R.; Roman, E.; Garry, A.C.; Patmore, R.; Howard, M.R. Haematological malignancy: are patients appropriately referred for specialist palliative and hospice care? A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Palliat Med. 2011, 25, 630–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, D.A.; Wang, H.-I.; Smith, A.G.; Howard, M.R.; Patmore, R.D.; Roman, E. Place of death in haematological malignancy: variations by disease sub-type and time from diagnosis to death. BMC Palliative Care. 2013, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawahri, A.; Nelson, A.M.; Gray, T.F.; Lee, S.J.; LeBlanc, T.W. Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Patients With Hematologic Malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2020, 38, 944–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Chan, L.S. Understanding of the Concept of "Total Pain": A Prerequisite for Pain Control. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2008, 10, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Organization, WH. WHO definition of palliative care 2002 [Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/.

- Pattison, M.; Romer, A.L. Improving care through the end of life: launching a primary care clinic-based program. J Palliat Med. 2001, 4, 249–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, Auber M, Kurian S, Rogers J, et al. Prognostic Significance of the “Surprise” Question in Cancer Patients. J Palliat Med. 2010, 13, 837–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni M, Zocchi D, Bolognesi D, Abernethy A, Rondelli R, Savorani G, et al. The ‘surprise’ question in advanced cancer patients: A prospective study among general practitioners. Palliative Medicine. 2014, 28, 959–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauh LA, Sullivan MW, Camacho F, Janke MJ, Duska LR, Chandler C, et al. Validation of the surprise question in gynecologic oncology: A one-question screen to promote palliative care integration and advance care planning. Gynecologic Oncology. 2020, 157, 754–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, D.; Straw, S.; Witte, K.K.; Napp, A. Palliativversorgung bei Herzinsuffizienz. Zeitschrift für Palliativmedizin. 2022, 23, 327–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Burgess, R.; Drozd, M.; Gierula, J.; Witte, K.; Straw, S. The Surprise Question and clinician-predicted prognosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2024, spcare-2024-004879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moor, C.C.; Tak van Jaarsveld, N.C.; Owusuaa, C.; Miedema, J.R.; Baart, S.; van der Rijt, C.C.D.; Wijsenbeek, M.S. The Value of the Surprise Question to Predict One-Year Mortality in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Prospective Cohort Study. Respiration. 2021, 100, 780–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahes A, Macchi ZA, Martin CS, Katz M, Galifianakis NB, Pantilat SZ, et al. The “Surprise Question” for Prognostication in People With Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024, 67, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis MP, Vanenkevort E, Young A, Wojtowicz M, Gupta M, Lagerman B, et al. Radiation Therapy in the Last Month of Life: Association With Aggressive Care at the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023, 66, 638–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, C.; Goebel, S.; Weber, S.; Weber, M.; Sleeman, K.E. Space for intuition – the ‘Surprise’-Question in haemato-oncology: Qualitative analysis of experiences and perceptions of haemato-oncologists. Palliat Med. 2019, 33, 531–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.; Kupeli, N.; Vickerstaff, V.; Stone, P. How accurate is the ‘Surprise Question’ at identifying patients at the end of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downar, J.; Goldman, R.; Pinto, R.; Englesakis, M.; Adhikari, N.K.J. The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2017, 189, E484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakin, J.R.; Robinson, M.G.; Bernacki, R.E.; Powers, B.W.; Block, S.D.; Cunningham, R.; Obermeyer, Z. Estimating 1-Year Mortality for High-Risk Primary Care Patients Using the “Surprise” Question. {JAMA Internal Medicine}. 2016, 176, 1863–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, E.; Chan, R.J.; Chambers, S.; Butler, J.; Yates, P. A systematic review of prognostic factors at the end of life for people with a hematological malignancy. BMC Cancer. 2017, 17, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, E.; Gavin, N.C.; Chan, R.J.; Connell, S.; Butler, J.; Yates, P. Harnessing the power of clinician judgement. Identifying risk of deteriorating and dying in people with a haematological malignancy: A Delphi study. J Adv Nurs. 2019, 75, 161–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, E.; Bolton, M.; Chan, R.J.; Chambers, S.; Butler, J.; Yates, P. A palliative care model and conceptual approach suited to clinical malignant haematology. Palliat Med. 2019, 33, 483–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics. 1977, 33, 159–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, K.; Coombes, L.H.; Menezes, A.; Anderson, A.-K. The ‘surprise’ question in paediatric palliative care: A prospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2018, 32, 535–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilley EJ, Gemunden SA, Kristo G, Changoor N, Scott JW, Rickerson E, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question in Predicting Survival among Older Patients with Acute Surgical Conditions. J Palliat Med. 2017, 20, 420–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, A.; Laking, G.; Frey, R.; Robinson, J.; Gott, M. Can we predict which hospitalised patients are in their last year of life? A prospective cross-sectional study of the Gold Standards Framework Prognostic Indicator Guidance as a screening tool in the acute hospital setting. Palliat Med. 2014, 28, 1046–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi K, Jambaulikar G, George NR, Xu W, Obermeyer Z, Aaronson EL, et al. The “Surprise Question” Asked of Emergency Physicians May Predict 12-Month Mortality among Older Emergency Department Patients. J Palliat Med. 2018, 21, 236–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practitioners, RCoG (Ed.) The GSF Prognostic Indicator Guidance: The National GSF Centre's guidance for clinicians to support earlier recognition of patients nearing the end of life Prognostic Indicator Guidance (PIG); 2011 October 2011: The Gold Standards Framework Centre in End of Life Care CIC.

- Gerlach C, Weber S, Hopprich A, Reinholz U, Wehler T, Heß G, et al. Pilotstudie zur Erfassung von Lebensqualität, Distress, Depressivität, Angst und Symptombelastung bei onkologischen Patienten in fortgeschrittenen Krankheitszuständen – Erste Ergebnisse. Zeitschrift für Palliativmedizin 2014, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, K.E.; Wolf, S.P.; Samsa, G.P.; Kamal, A.H.; Abernethy, A.P.; LeBlanc, T.W. The Surprise Question and Identification of Palliative Care Needs among Hospitalized Patients with Advanced Hematologic or Solid Malignancies. J Palliat Med. 2018, 21, 789–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel JS, Greer J, Gallagher E, Admane S, Pirl WF, Jackson V, et al. Effect of early palliative care (PC) on quality of life (QOL), aggressive care at the end-of-life (EOL), and survival in stage IV NSCLC patients: Results of a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28, 7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Li Z, et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015, 33, 1438–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc TW, Burns LJ, Denzen E, Meyer C, Mau L-W, et al. What do transplant physicians think about palliative care? A national survey study. Cancer 2018, 124, 4556–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Park, M.; Liu, D.; Reddy, A.; Dalal, S.; Bruera, E. Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Supportive and Palliative Care Referral Among Hematologic and Solid Tumor Oncology Specialists. The Oncologist. 2015, 20, 1326–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, T.W.; El-Jawahri, A. Hemato-oncology and palliative care teams: is it time for an integrated approach to patient care? Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care. 2018, 12, 530–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, C.; Alt-Epping, B.; Oechsle, K. Specific challenges in end-of-life care for patients with hematological malignancies. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, C.; Ratjen, I.; Brandt, J.; Para, S.; Alt-Epping, B.; van Oorschot, B.; Letsch, A. Screening of symptoms and needs in hematology-observations from practice. Onkologie-Ger. 2023, 29, 351–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salins, N.; Ghoshal, A.; Hughes, S.; Preston, N. How views of oncologists and haematologists impacts palliative care referral: a systematic review. BMC Palliative Care. 2020, 19, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, C.; Mai, S.; Schmidtmann, I.; Massen, C.; Reinholz, U.; Laufenberg-Feldmann, R.; Weber, M. Does Interdisciplinary and Multiprofessional Undergraduate Education Increase Students' Self-Confidence and Knowledge Toward Palliative Care? Evaluation of an Undergraduate Curriculum Design for Palliative Care at a German Academic Hospital. J Palliat Med. 2015, 18, 513–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, C.; Mai, S.S.; Schmidtmann, I.; Weber, M. Palliative care in undergraduate medical education - consolidation of the learning contents of palliative care in the final academic year. GMS journal for medical education 2021, 38, Doc103. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).