Submitted:

31 October 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

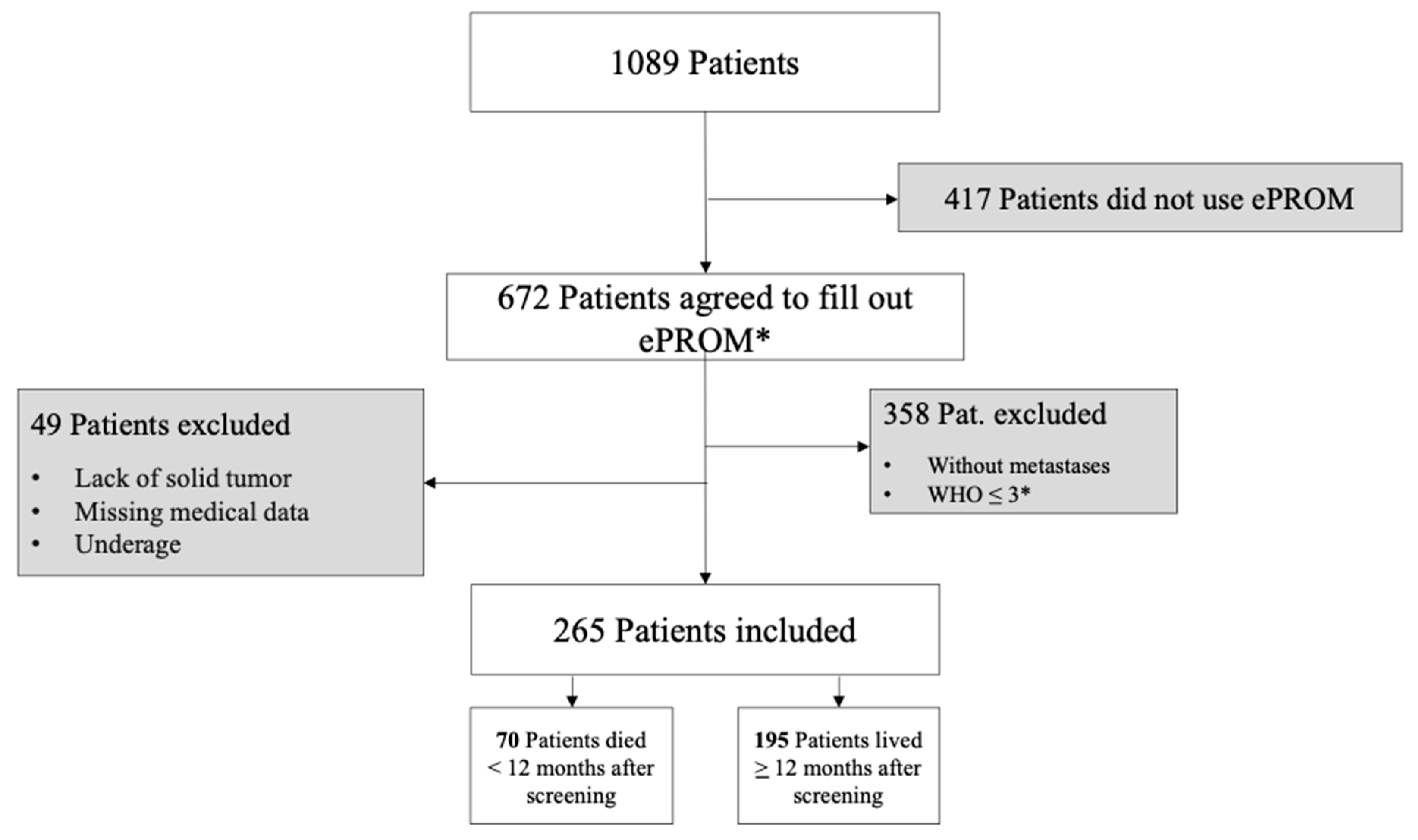

Study Design and Sample Description

3. Data Collection

3.1. ePROM (Electronic Patient Reported Outcome Measure)

3.2. Non-Patient Reported Outcome Variables

3.3. Prognostic Machine Learning Models

3.4. Evaluation Procedure and Metrics

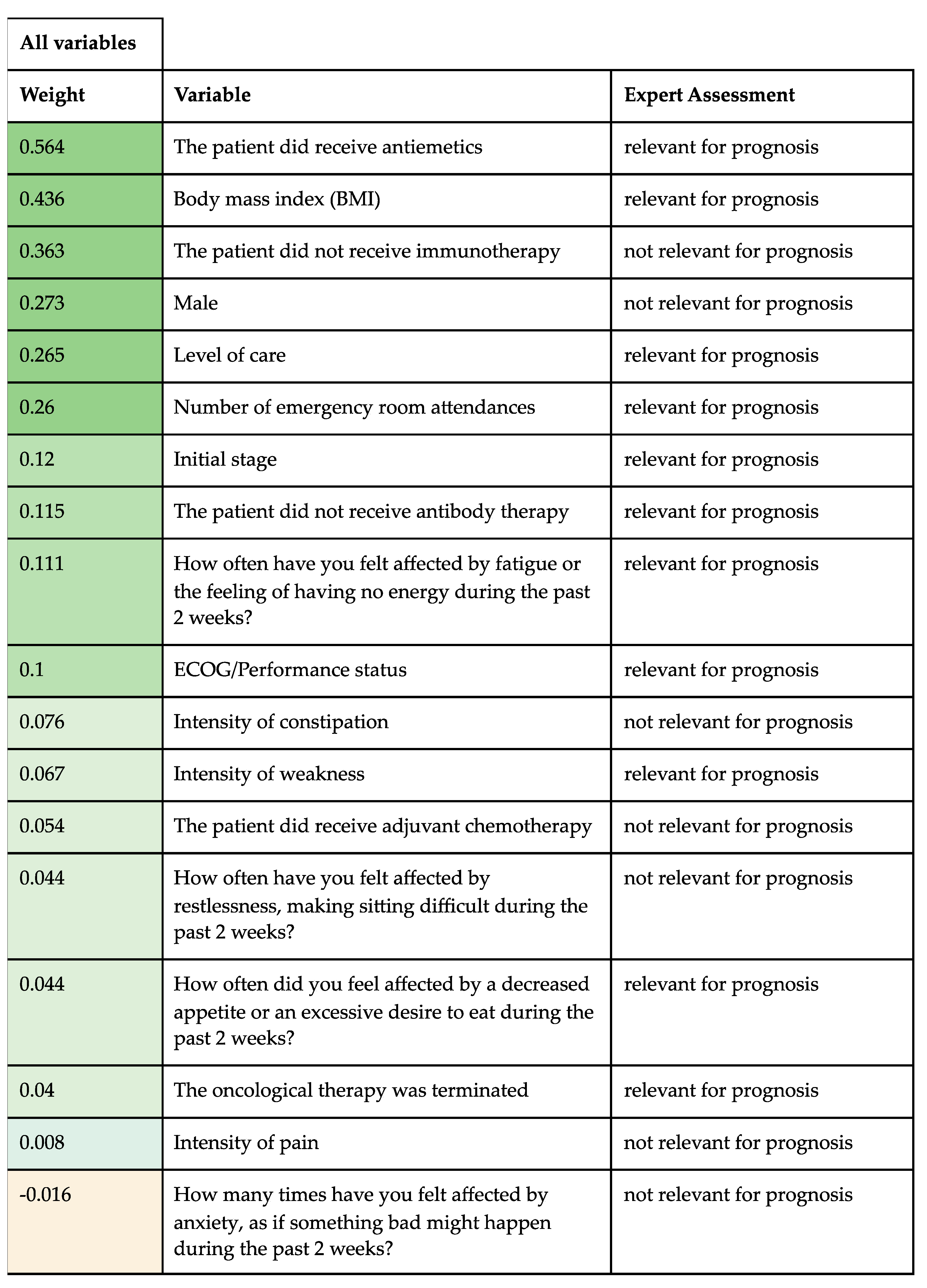

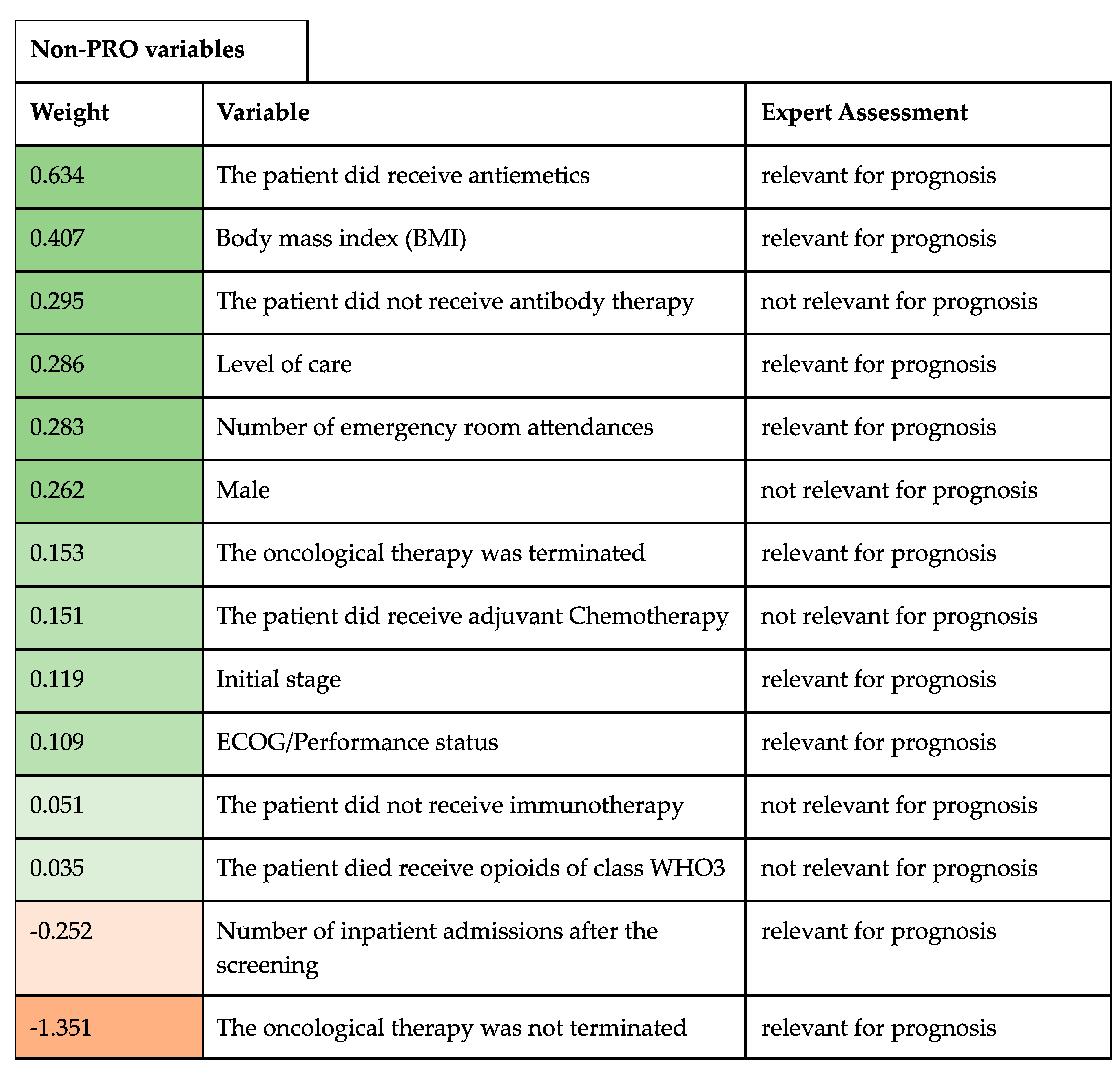

4. Variable Importance

5. Results

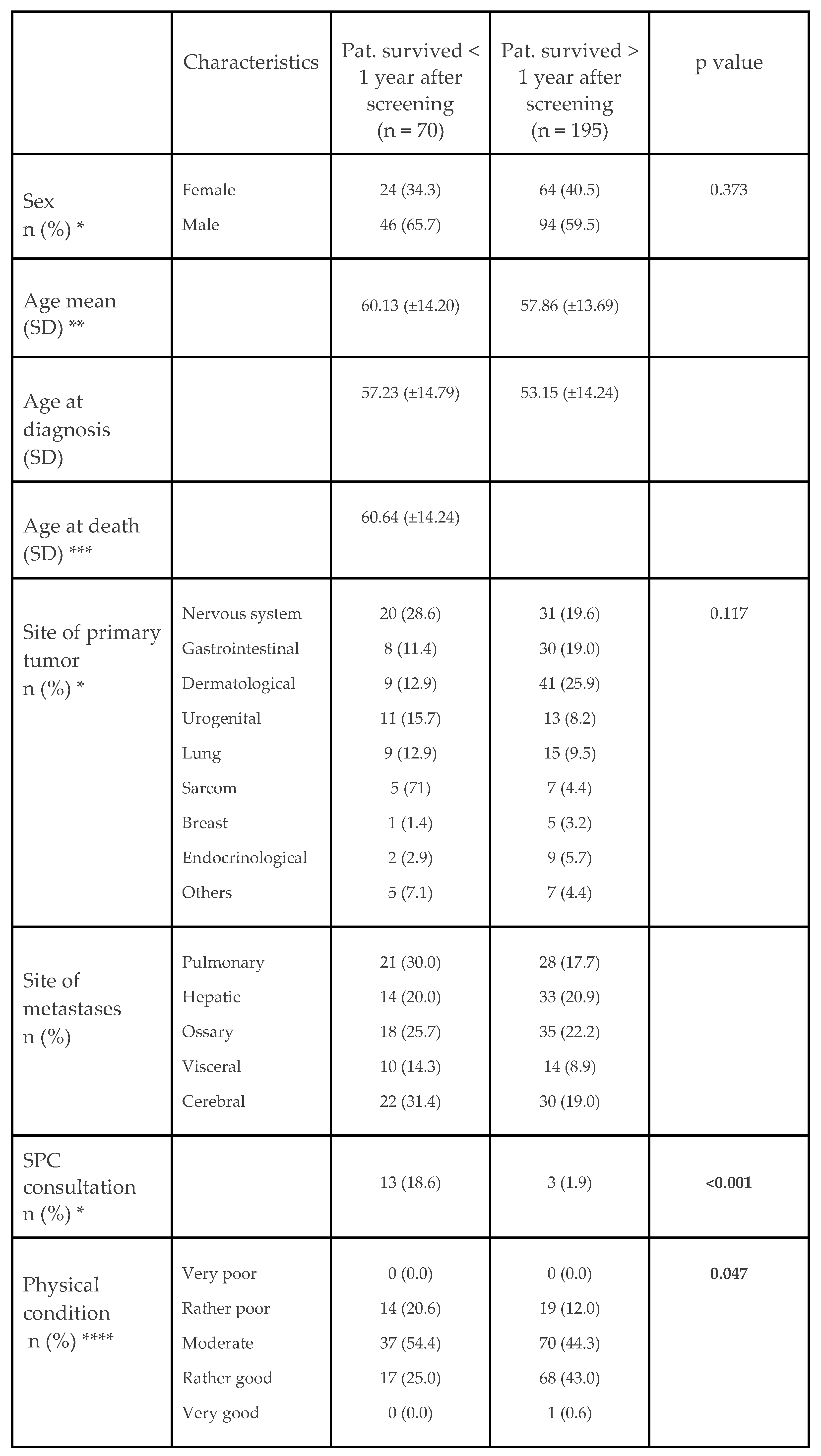

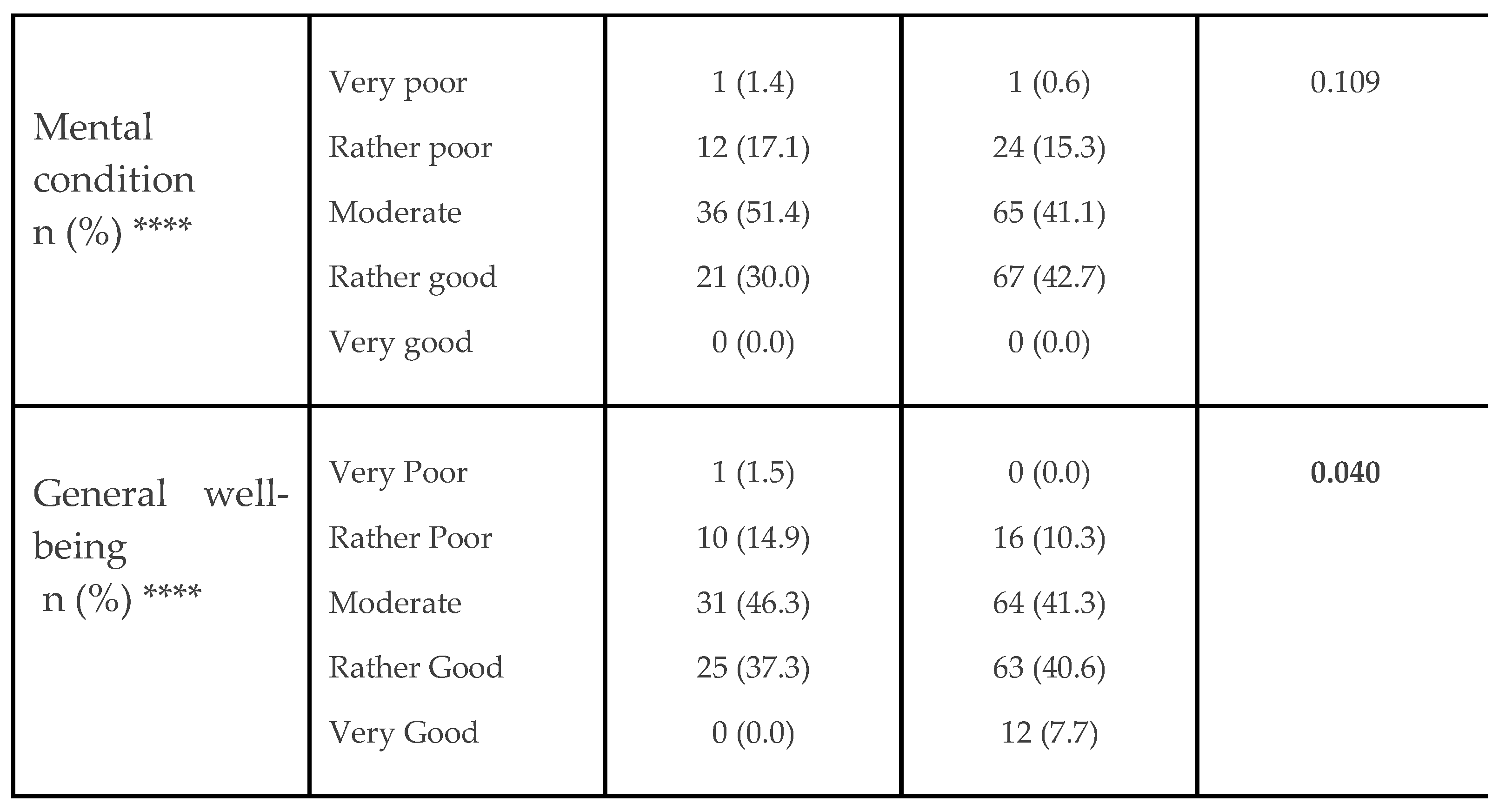

5.1. Patient Characteristics

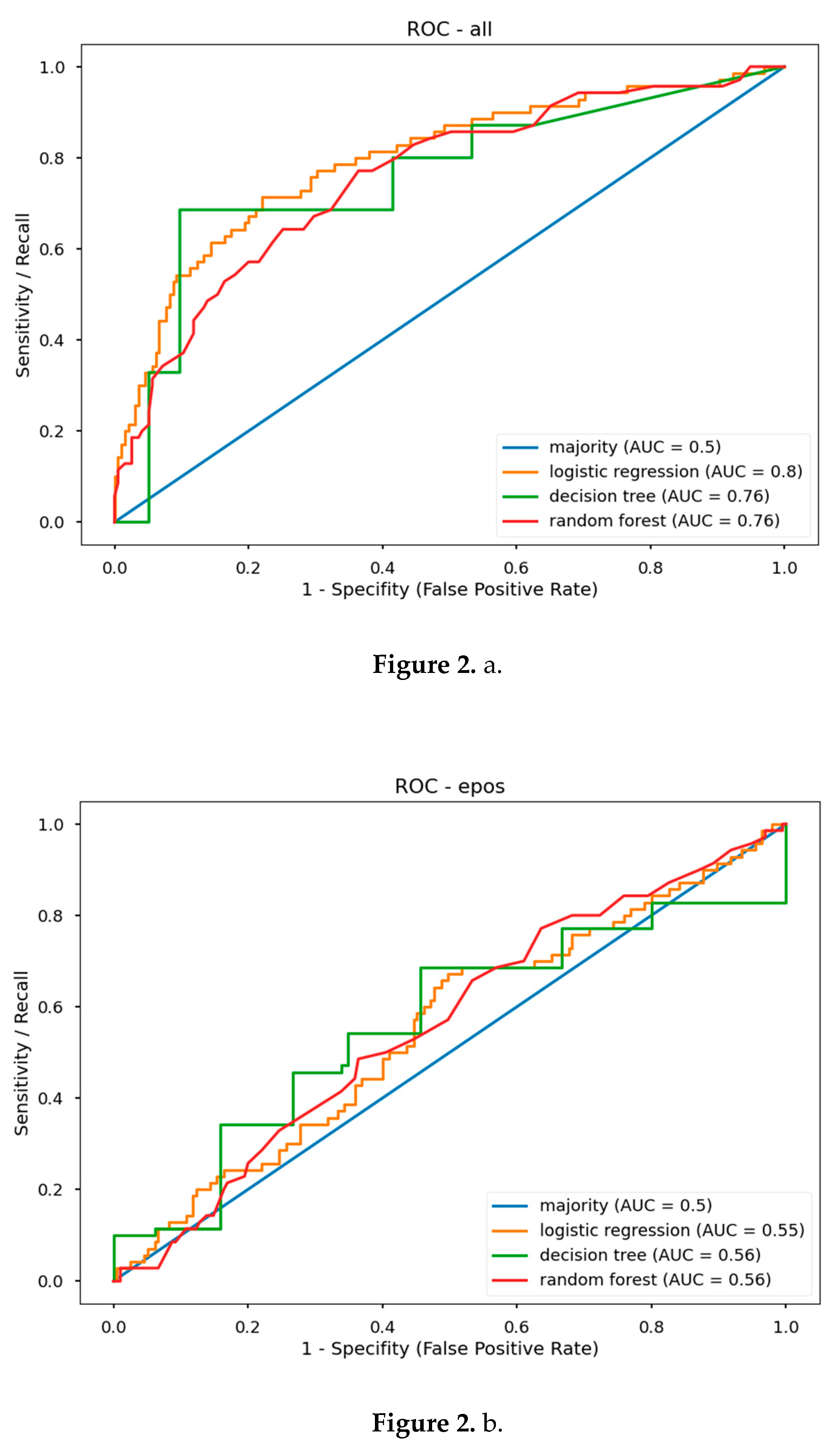

5.2. Predictive Model Performance

5.3. Prognostic Value

| a |

|

| b |

|

5.4. Expert Assessment

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vanbutsele, G; Pardon, K; Van Belle, S et al. Effect of Early and Systematic Integration of Palliative Care in Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Oncology 2018, 19(3), 394–404. [CrossRef]

- Haun, M.W.; Estel, S.; Rücker, G. et al. Early Palliative Care for Adults with Advanced Cancer. Cochrane Db Syst Rev 2017, 2017, CD011129. [CrossRef]

- Kaasa, S.; Loge, J.H.; Aapro, M. et al. Integration of Oncology and Palliative Care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol 2018, 19, e588–e653. [CrossRef]

- German Guideline Program in Oncology (German Cancer Society, G.C.A., AWMF): Palliative Care for Patients with Incurable Cancer, Extended Version—Short Version 2.2, 2020 AWMF-Registration Number 128/001OL. Available online: https://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Hui, D.; Mori, M.; Watanabe, S.M. et al. Referral Criteria for Outpatient Specialty Palliative Cancer Care: An International Consensus. Lancet Oncol 2016, 17, e552–e559. [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Hannon, B.L.; Zimmermann, C. et al. Improving Patient and Caregiver Outcomes in Oncology: Team-based, Timely, and Targeted Palliative Care. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68. [CrossRef]

- Coventry, PA; Grande, GE; Rucgards, DA et al. Prediction of Appropriate Timing of Palliative Care for Older Adults with Non-Malignant Life-Threatening Disease: A Systematic Review. Age Ageing 2005, 34(3), 218-27. [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Hannon, B.L.; Zimmermann, C. et al. Improving Patient and Caregiver Outcomes in Oncology: Team-based, Timely, and Targeted Palliative Care. Ca Cancer J Clin 2018, 68, 356–376. [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Heung, Y.; Bruera, E. Timely Palliative Care: Personalizing the Process of Referral. Cancers 2022, 14, 1047. [CrossRef]

- Hui, D; Mori, M; Meng, YC et al. Automatic Referral to Standardize Palliative Care Access: An International Delphi Survey. Supportive Care in Cancer 2017. [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Mody, G.N.; Dueck, A.C. Electronic Patient-Reported Outcomes as Digital Therapeutics to Improve Cancer Outcomes. Jco Oncol Pract 2020, 16, 541–542. [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Deal, A.M.; Dueck, A.C. et al. Overall Survival Results of a Trial Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes for Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Treatment. JAMA 2017, 318, 197. [CrossRef]

- Denis, F.; Basch, E.; Septans, A.L. et al. Two-Year Survival Comparing Web-Based Symptom Monitoring vs Routine Surveillance Following Treatment for Lung Cancer. JAMA 2019, 321.

- Basch, E.; Deal, A.M.; Kris, M.G. et al. Symptom Monitoring With Patient-Reported Outcomes During Routine Cancer Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34, 557–565. [CrossRef]

- Barbera, L.; Sutradhar, R.; Seow, H. et al. Impact of Standardized Edmonton Symptom Assessment System Use on Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalization: Results of a Population-Based Retrospective Matched Cohort Analysis. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e958–e965. [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Wilfong, L.; Schrag, D. et al. Adding Patient-Reported Outcomes to Medicare’s Oncology Value-Based Payment Model. JAMA 2020. [CrossRef]

- Killock, D. AI Outperforms Radiologists in Mammographic Screening. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 134–134. [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R. et al. Dermatologist-Level Classification of Skin Cancer with Deep Neural Networks. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Gao, G.; Dai, J. et al Prediction of Lung Infection during Palliative Chemotherapy of Lung Cancer Based on Artificial Neural Network. Comput. Math. Methods Medicine 2022, 2022, 4312117. [CrossRef]

- Van Helden, E.J.; Vacher, Y.J.L.; Wieringen, W.N. et al. Radiomics Analysis of Pre-Treatment [18F]FDG PET/CT for Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Palliative Systemic Treatment. Eur. J. Nucl. Medicine Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 2307–2317. [CrossRef]

- Vu, E.; Steinmann, N.; Schröder, C. et al. Applications of Machine Learning in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 1596. [CrossRef]

- Avati, A.; Jung, K.; Harman, S. et al. Improving Palliative Care with Deep Learning. BMC Méd. Informatics Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 122. [CrossRef]

- Cary, M.P.; Zhuang, F.; Draelos, R.L. et al. Machine Learning Algorithms to Predict Mortality and Allocate Palliative Care for Older Patients With Hip Fracture. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2021, Pages 291-296. [CrossRef]

- Manz, C.R.; Parikh, R.B.; Small, D.S. et al. Effect of Integrating Machine Learning Mortality Estimates With Behavioral Nudges to Clinicians on Serious Illness Conversations Among Patients With Cancer. Jama Oncol 2020, 6, e204759. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R.B.; Manz, C.; Chivers, C. et al. Machine Learning Approaches to Predict 6-Month Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1915997. [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Paiva, C.E.; del Fabbro, E.G. et al. Prognostication in Advanced Cancer: Update and Directions for Future Research. Supportive Care in Cancer 2019, 27, 1973–1984.

- Mitra, T.; Rettler, T.M.; Beckmann, M. et al. Patient-Reported-Outcome-Messung (PROM) Psychosozialer Belastung Und Symptome Für Ambulante Patienten Unter Kurativer Oder Palliativer Tumortherapie – Eine Retrospektive Analyse Eines Comprehensive Cancer Center. Der Onkologe 2018, 24(1), 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Löwe, B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A Systematic Review. General Hospital Psychiatry 32, 345–359. [CrossRef]

- Plummer, F.; Manea, L.; Trepel, D. Screening for Anxiety Disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A Systematic Review and Diagnostic Metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Stiel, S.; Bertram, M.E.M.L.; Ostgathe, C. et al. Validation of the New Version of the Minimal Documentation System (MIDOS) for Patients in Palliative Care: The German Version of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS)]. Schmerz. [CrossRef]

- Buchhold, B.; Lutze, S.; Freyer-Adam, J. et al. Validation of the Psychometric Properties of a “Modified Version of the Hornheider Screening Instrument” (HSI-MV) Using a Sample of Outpatient and Inpatient Skin Tumor Patients. JDDG: J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2022, 20, 597–609. [CrossRef]

- Ownby, K.K. Use of the Distress Thermometer in Clinical Practice. J. Adv. Pr. Oncol. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Storick, V.; O’Herlihy, A.; Abdelhafeez, S. et al. Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care with Machine Learning and Routine Data: A Rapid Review. HRB Open Res. 2019, 2, 13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sha, L.; Lakin, J.R. et al. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for Mortality Prediction in Selecting Patients With Dementia for Earlier Palliative Care Interventions. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196972. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; McConnell, W. Predicting Potential Palliative Care Beneficiaries for Health Plans: A Generalized Machine Learning Pipeline. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 123, 103922. [CrossRef]

- Berg, G.D.; Gurley, V.F. Development and Validation of 15-Month Mortality Prediction Models: A Retrospective Observational Comparison of Machine-Learning Techniques in a National Sample of Medicare Recipients. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e022935. [CrossRef]

- Blanes-Selva, V.; Ruiz-García, V.; Tortajada, S. et al. Design of 1-Year Mortality Forecast at Hospital Admission: A Machine Learning Approach. Heal. Inform. J. 2021, 27, 1460458220987580. [CrossRef]

- Courtright, K.R.; Chivers, C.; Becker, M. et al. Electronic Health Record Mortality Prediction Model for Targeted Palliative Care Among Hospitalized Medical Patients: A Pilot Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 1841–1847. [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; White, N.; Stone, P. Prognostication in Palliative Care. Clin. Med. 2019, 19, 306–310. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Hiratsuk, Y.; Suh, S.Y. Clinicians’ Prediction of Survival and Prognostic Confidence in Patients with Advanced Cancer in Three East Asian Countries. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2023. [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, J.; Hupcey, J.E. A Systematic Review on Barriers to Palliative Care in Oncology. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 2021, 1361–1377. [CrossRef]

- Gothe, H.; Brinkmann, C.; Schmedt, N. Is There an Unmet Medical Need for Palliative Care Services in Germany? Incidence, Prevalence, and 1-Year All-Cause Mortality of Palliative Care Sensitive Conditions: Real-World Evidence Based on German Claims Data. J. Public Heal. 2022, 30, 711–720. [CrossRef]

- Windisch, P.; Hertler, C.; Blum, D. Leveraging Advances in Artificial Intelligence to Improve the Quality and Timing of Palliative Care. Cancers 2020, 12, 1149. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Zafra, M.I.; Gómez-García, R.; Ocaña-Riola, R. et al. Level of Palliative Care Complexity in Advanced Cancer Patients: A Multinomial Logistic Analysis. J Clin Medicine 2020, 9, 1960. [CrossRef]

- Tewes, M.; Rettler, T.; Wolf, N. et al. Predictors of Outpatients’ Request for Palliative Care Service at a Medical Oncology Clinic of a German Comprehensive Cancer Center. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3641–3647. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, J.; Beyer, F.; Sistermanns, J. et al. Symptom Burden and Palliative Care Needs of Patients with Incurable Cancer at Diagnosis and During the Disease Course. Oncol 2021, 26, e1058–e1065. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Luo, B. Prognostic Factors and Survival Prediction in HER2-positive Breast Cancer with Bone Metastases: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 8114–8126. [CrossRef]

- Greenlee, H.; Unger, J.M.; LeBlanc, M. et al. Association between Body Mass Index and Cancer Survival in a Pooled Analysis of 22 Clinical Trials. Cancer Epidemiology Prev. Biomark. 2017, 26, 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Tripodoro, V.A.; Llanos, V.; Daud, M.L et al. Palliative and Prognostic Approach in Cancer Patients Identified in the Multicentre NECesidades PALiativas 2 Study in Argentina. ecancermedicalscience 2021, 15, 1316. [CrossRef]

- Ediebah, D.E.; Quinten, C.; Coens, C. et al. Quality of Life as a Prognostic Indicator of Survival: A Pooled Analysis of Individual Patient Data from Canadian Cancer Trials Group Clinical Trials. Cancer 2018, 124, 3409–3416. [CrossRef]

- Qian, A.S.; Qiao, E.M.; Nalawade, V. et al. Impact of Underlying Malignancy on Emergency Department Utilization and Outcomes. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 9129–9138. [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, R.R.; Yekkaluri, S.; Meyer, E. et al. Emergency Room Presentation of Lung Cancer as a Highly Practical Prognostic Marker for Consideration in Clinical Trials: A SEER Database Analysis.; 2020.

- Owusuaa, C.; Dijkland, S.A.; Nieboer, D. et al. Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Advanced Cancer—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 14, 328. [CrossRef]

- Garinet, S.; Wang, P.; Mansuet-Lupo, A. et al. Updated Prognostic Factors in Localized NSCLC. Cancers 2022, 14, 1400. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, E.; Sugii, N.; Matsuda, M. et al. Maximum Resection and Immunotherapy Improve Glioblastoma Patient Survival: A Retrospective Single-Institution Prognostic Analysis. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 282. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R.B.; Manz, C.R.; Nelson, M.N. et al. Clinician Perspectives on Machine Learning Prognostic Algorithms in the Routine Care of Patients with Cancer: A Qualitative Study. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4363–4372. [CrossRef]

- Spooner, C.; Vivat, B.; White, N. et al. What Outcomes Do Studies Use to Measure the Impact of Prognostication on People with Advanced Cancer? Findings from a Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies. Palliat. Med. 2023, 2692163231191148. [CrossRef]

- Semler, S.C.; Wissing, F.; Heyder, R. German Medical Informatics Initiative. Methods Inf. Med. 2018, 57, e50–e56. [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, J.; Hallek, J.W.; Hallek, M. et al. Standardizing Integration of Palliative Care into Comprehensive Cancer Therapy—a Disease Specific Approach. Supportive Care in Cancer volume 2011, 19, 1037–1043. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z. et al. Prognostic Value of Baseline and Change in Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio for Survival in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients with Poor Performance Status Receiving PD-1 Inhibitors. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1397–1407. [CrossRef]

- Berlanga, M; Cupp, I.; Tyoulaki, E. et al. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio and Cancer Prognosis: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies. BMC Medicine 2020, 18. [CrossRef]

- Amano, K.; Maeda, I.; Morita, T. et al. Clinical Implications of C-Reactive Protein as a Prognostic Marker in Advanced Cancer Patients in Palliative Care Settings. J Pain Symptom Manag 2016, 51, 860–867. [CrossRef]

- SEER*Explorer: An Interactive Website for SEER Cancer Statistics [Internet]. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/report_to_nation/ (accessed 10 Sept 2023).

- Sandham, M.H.; Hedgecock, E.A.; Siegert, R.J. et al. Intelligent Palliative Care Based on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, 747–757. [CrossRef]

|

|

| PRO Variables (Subjective) |

non-PRO Variables (Clinical) | All Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROC AUC | F1 Score | ROC AUC | F1 Score | ROC AUC | F1 Score | |

| Majority | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.42 |

| LR | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.72 |

| DT | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.67 |

| RF | 0.56 | 0.45 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).