Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Apparent diffusion coefficient |

| AE | Alveolar echinococcosis |

| CE | Cystic echinococcosis |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DWI | Diffusion weighted imaging |

| MoCAT | Modified catheterization technique |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| PAIR | Puncture-Aspiration of cyst contents-Injection of protoscolecidal agents |

| T1WI | T1 weighted image |

| T2WI | T2 weighted image |

| US | Ultrasound |

References

- Gatti, M.; Maino, C.; Tore, D.; Carisio, A.; Darvizeh, F.; Tricarico, E.; Inchingolo, R.; Ippolito, D.; Faletti, R. Benign focal liver lesions: The role of magnetic resonance imaging. World J. Hepatol. 2022, 14, 923–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calame, P.; Weck, M.; Busse-Cote, A.; Brumpt, E.; Richou, C.; Turco, C.; Doussot, A.; Bresson-Hadni, S.; Delabrousse, E. Role of the radiologist in the diagnosis and management of the two forms of hepatic echinococcosis. Insights into Imaging 2022, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou; Alexiou, K. ; Mitsos, S.; Fotopoulos, A.; Karanikas, I.; Tavernaraki, K.; Konstantinidis, F.; Antonopoulos, P.; Ekonomou, N. Complications of Hydatid Cysts of the Liver: Spiral Computed Tomography Findings. Gastroenterol. Res. 2012, 5, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallali, M.; Chaouch, M.A.; Zenati, H.; Ben Hassine, H.; Saad, J.; Noomen, F. Primary isolated hydatid cyst of the spleen: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 117, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrone, G.; Crino', F.; Caruso, S.; Mamone, G.; Carollo, V.; Milazzo, M.; Gruttadauria, S.; Luca, A.; Gridelli, B. Multidisciplinary imaging of liver hydatidosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 1438–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, I.; Saíz, A.; Arrazola, J.; Ferreirós, J.; Pedrosa, C.S. Hydatid Disease: Radiologic and Pathologic Features and Complications. RadioGraphics 2000, 20, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutihar, A.; Lamichhane, D.; JanakyRaman, G.; Arafin, M.; Shrestha, R.J.; Pandey, N.; Yadav, A.; Uprety, S. Giant Calcified Hepatic Hydatid Cyst: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesemma, A.; Adane, M.; Bekele, K.; Debebe, B.; Rosso, E.; Zenbaba, D.; Gomora, D.; Beressa, G. Giant pedunculated liver hydatid cyst causing inferior vena cava syndrome: a case report. J. Med Case Rep. 2024, 18, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, M.R.; Deepashri, B.; Lakshmeesha, M.T. Imaging Spectrum of Hydatid Disease: Usual and Unusual Locations. Pol. J. Radiol. 2016, 81, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Neglected tropical diseases in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals. WHO-HTM-NTD-NZD-2017.01. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HTM-NTD-NZD-2017.

- Farrar J, Hotez PJ, Junghanss T, Kang G, Lalloo D, White NJ, Garcia PJ. Manson's Tropical Diseases. 24th ed. London: Elsevier; 2023. ISBN: 9780702079597.

- Precetti, S.; Gandon, Y.; Vilgrain, V. ing of cystic liver diseases. J. Radiol. 2007, 88, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Vuitton, L.; Tuxun, T.; Li, J.; Vuitton, D.A.; Zhang, W.; McManus, D.P. Echinococcosis: Advances in the 21st Century. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00075–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortelé, K.J.; Ros, P.R. Cystic Focal Liver Lesions in the Adult: Differential CT and MR Imaging Features. RadioGraphics 2001, 21, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grocholski, S.; Agabawi, S.; Kadkhoda, K.; Hammond, G. Echinococcus granulosus hydatid cyst in rural Manitoba, Canada: Case report and review of the literature. IDCases 2019, 18, e00632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inan, N.; Arslan, A.; Akansel, G.; Anik, Y.; Sarisoy, H.T.; Ciftci, E.; Demirci, A. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging in the Differential Diagnosis of Simple and Hydatid Cysts of the Liver. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2007, 189, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalcinoz, K.; Ikizceli, T.; Kahveci, S.; Karahan, O.I. Diffusion-weighted MRI and FLAIR sequence for differentiation of hydatid cysts and simple cysts in the liver. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2021, 8, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konukoglu, O.; Tahtabasi, M.; Boyaci, F.N.; Karakas, E. The role of diffusion-weighted imaging in the differential diagnosis of liver lesions. Central Asian J. Med Hypotheses Ethic- 2024, 5, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuric-Stefanovic, A.; Cvejic, S.; Mijovic, K.; Ostojic, S. Rosette sign. Abdom. Imaging 2022, 47, 2560–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetti, E.; Kern, P.; Vuitton, D.A.; Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010, 114, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhan, O.; Gumus, B.; Akinci, D.; Karcaaltincaba, M.; Ozmen, M. Diagnosis and Percutaneous Treatment of Soft-Tissue Hydatid Cysts. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2007, 30, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| WHO-IWGE staging | MRI | US |

|---|---|---|

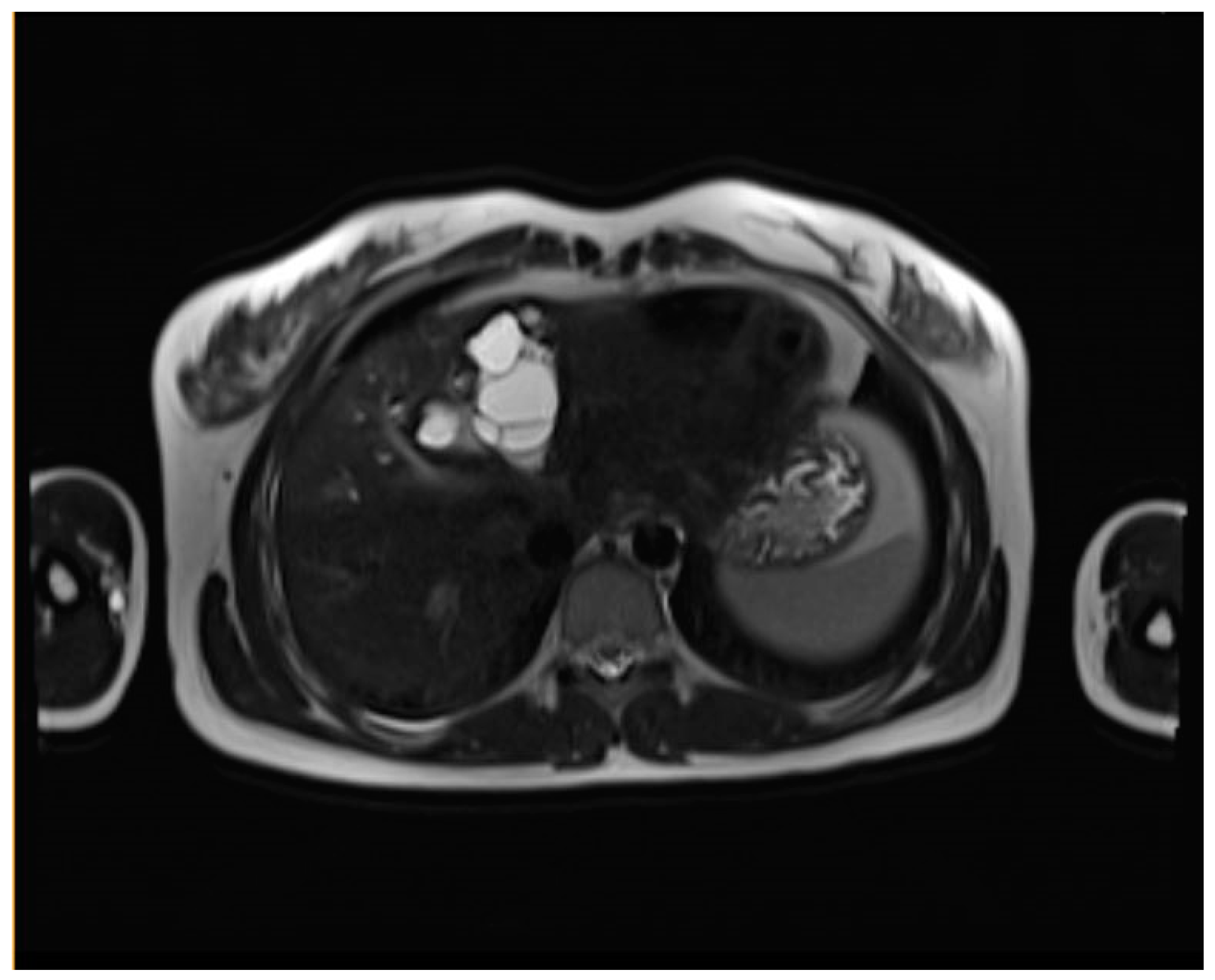

| CE1 (Simple cyst) | Well-defined, unilocular cyst with a peripheral capsule, hypointense on T2WI, possible rim sign. Hyperintense hydatid matrix on DWI and ADC. | Unilocular anechoic cyst with possible rim sign and internal echoes (hydatid sand, snowflake sign) seen after repositioning. |

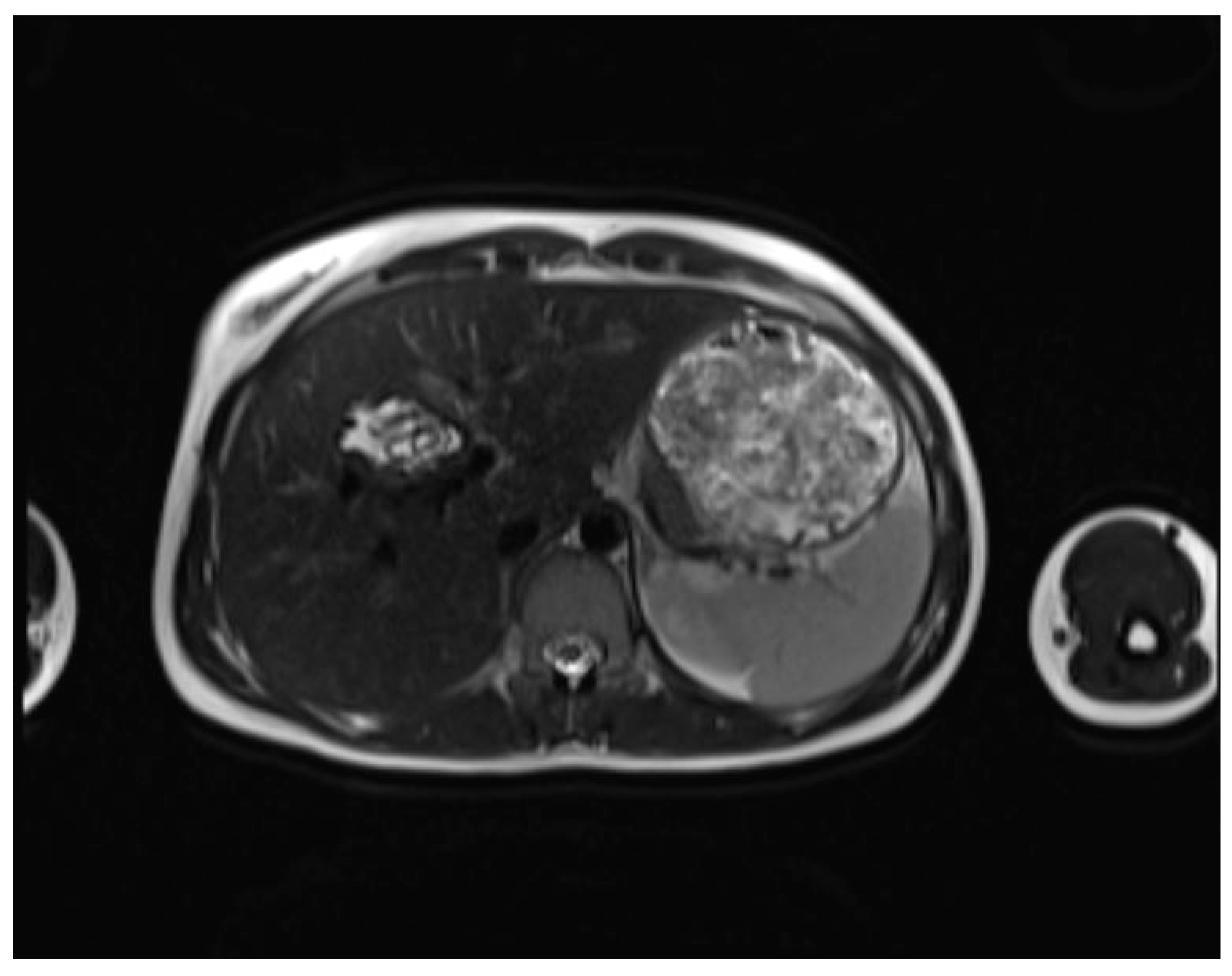

| CE2 (Cyst with daughter cysts and matrix) | Multicystic mass with septa (wheel-spoke pattern), daughter cysts are hypointense or isointense compared to the mother cyst on both T1WI and T2WI. | Well-defined cyst with multiple internal septations and daughter cysts, described as honeycomb or rosette appearance. |

| CE3A (Transitional) | Detachment of laminated membranes, with a floating water lily sign or serpent sign. Daughter cysts may be visible in the matrix. | Internal floating membranes or detached laminated membranes (water lily sign). |

| CE3B (Transitional; daughter cysts within solid matrix) | Solid matrix with visible daughter cysts; signal intensity varies depending on the proteinaceous content of the cyst. | Similar to CE3A, but daughter cysts are present within a solid matrix, often with calcification. |

| CE4 (Complicated or inactive cyst) | Heterogeneous mass with hypointense and hyperintense areas, often partially or completely calcified. Inactive stage. May show signs of complication like rupture (biliary communication) or infection. | Cyst with heterogeneous hypoechoic and hyperechoic contents, resembling a ball of wool; absence of daughter cysts. |

| CE5 (Completely calcified cyst) | Complete calcification, appearing as hypointense on all MRI sequences due to lack of fluid. No residual daughter cysts. | Completely calcified cyst with no internal structures. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).