1. Introduction

The female pelvic anatomy consists of interconnected organs, muscles, ligaments, and fasciae that support the bladder, uterus, and rectum, maintaining pelvic organ position and function [

1]. This intricate structure is prone to conditions such as pelvic organ prolapse (POP) [

2], where weakened support tissues cause the descent of pelvic organs like the anterior or posterior vaginal walls and the vaginal apex (e.g., uterus or vaginal cuff scar post-hysterectomy), as noted by IUGA and ICS [

3,

4].

The vaginal canal, located between the bladder and rectum, is particularly vulnerable to structural changes, leading to conditions like cystocele (bladder pressing into the anterior vaginal wall) and rectocele (rectum pressing into the posterior vaginal wall) [

5,

6]. These interdependent structures highlight the challenges in treating POP effectively. Beyond physical symptoms, POP affects a woman’s quality of life, impacting emotional and social well-being [

7,

8,

9].

POP prevalence is influenced by factors such as childbirth, menopause, and hysterectomy [

10,

11,

12], affecting 3–6% of women. It represents a significant public health concern due to its impact on quality of life and the high cost of treatment [

13]. Women aged 60 to 69 have the highest rates of POP surgery, with 6–18% requiring surgical intervention and an annual incidence of 1.5–1.8 per 1000 women [

14]. Approximately 29% of surgeries involving synthetic mesh implants lead to reoperation due to complications [

15,

16], further increasing healthcare costs, which average

$9,000 per procedure in the USA [

17]. In April 2019, the FDA ordered the withdrawal of all transvaginal mesh products for POP repair from the market [

18].

In this context, the development of innovative tools to enhance understanding of this issue is crucial for designing and implementing effective and viable therapeutic procedures. Recent studies have focused on developing novel biodegradable mesh implants with varying geometries, pore sizes, and filament diameters; however, these efforts remain in the testing and analysis phase [

19,

20,

21]. Both medical-grade and non-medical-grade PCL have been investigated for this application, including their degradation properties [

22,

23,

24]. Additionally, other research has explored the adaptation of cog threads, commonly used in facelift procedures, for prolapse repair [

25,

26].

Cog threads were first introduced in obstetrics and gynecology in 2008, initially used for tissue reapproximation during laparoscopic myomectomy and specific hysterectomy procedures [

26]. An ex vivo study demonstrated that applying cog threads to the sow's vaginal wall resulted in an increase in tissue strength, highlighting their potential for reinforcing the vaginal wall. These threads offer structural support during degradation, contributing to the observed increase in tissue strength [

22].

Diagnostic techniques such as clinical examination and medical imaging are commonly employed to evaluate POP, but they often lack the precision needed to quantify the extent of prolapse and its impact on pelvic floor function [

27]. The POP Quantification (POP-Q) system remains the standard for assessing prolapse severity by measuring the descent of specific pelvic segments relative to the hymen during the Valsalva maneuver [

28,

29]. While objective, the POP-Q system does not address the biomechanical factors or mechanisms underlying prolapse, limiting its effectiveness in guiding targeted therapeutic strategies [

30]. To overcome these limitations, the development of devices capable of quantifying intravaginal forces has emerged as a promising approach, enabling a deeper understanding of vaginal wall biomechanics and advancing diagnostic and treatment options.

Recent research has focused on creating devices that measure force distribution and structural integrity within the vaginal walls. For instance, vaginal tactile imaging generates detailed images of vaginal tissue and surrounding structures, offering valuable insights but requiring numerous pressure sensors, typically 120, which drives up production costs [

31]. Similarly, manometry catheters, widely used for evaluating vaginal pressure profiles, provide accurate readings at specific points but are less reliable in the distal vagina, where air exposure compromises pressure measurements [

32]. Other innovations, such as optical-fiber sensor devices, can map absolute pressure and pressure distribution within the vaginal canal [

33]. However, these designs also require multiple sensors, which increase manufacturing costs, reduce durability, and complicates handling, hindering widespread adoption [

34]. Recently, a novel diagnostic device has been developed using a standard stainless steel duckbill bivalve speculum with parallel blade dilatation, commonly employed in gynecological examinations as a minimally invasive procedure. This modified speculum can be locked at any opening between 0 and 3 cm and is equipped with eight sensors (four on each blade, superior and inferior). These sensors enable the precise measurement of intravaginal forces at each dilation point [

35,

36].

Therefore, this study aims to conduct an in vivo analysis in sheep. The animals underwent minimally invasive surgical implantation of cog threads to assess vaginal wall reinforcement, with evaluations performed before implantation, as well as at 90 and 180 days post-surgery. To assess the reinforcement, we used the novel device mentioned above [

35,

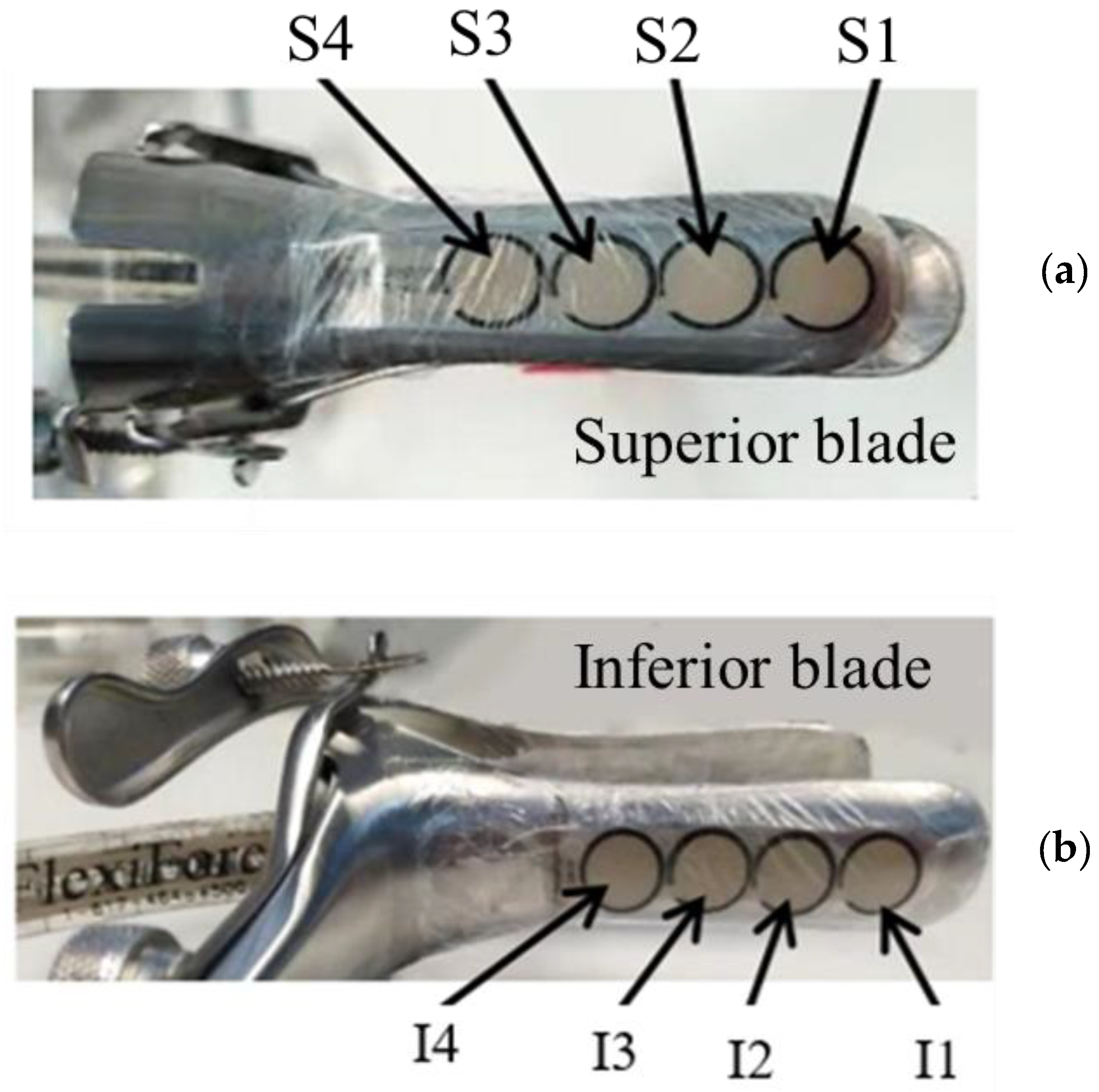

36]. However, in this study, only three sensors on each blade were used to measure the intravaginal force, as the vaginal canal of sheep is smaller than that of humans [

37], making the speculum less ideal for sheep.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Vivo Analysis

A total of ten sheep (n=5) were included in this study. The five sheep underwent surgical intervention, during which cog threads were implanted into their vaginal walls. These measurements were used to evaluate the reinforcing effect of the cog threads on the vaginal tissue. Measurements were conducted before surgery and at two post-surgical intervals: 90 days and 180 days. Due to anesthesia during the surgical procedures, intravaginal measurements were not performed immediately after the insertion of the cog threads. To minimize variability, all selected sheep had consistent characteristics, including age and weight. All animal procedures complied with Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and DL 113/2013. The procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Animal Protection Agency of ICBAS-UP and the Direção-Geral de Alimentação e Veterinária (DGAV). Animal welfare was carefully monitored throughout the study, following the OECD’s Guidance Document on the Recognition, Assessment, and Use of Clinical Signs as Humane Endpoints for Experimental Animals Used in Safety Evaluation (2000). All necessary measures to minimize pain and discomfort were implemented, with animals managed by FELASA C-certified veterinary surgeons experienced in handling this specific animal model.

2.2. In Vivo Minimally Invasive Surgery for Cog Thread Insertion

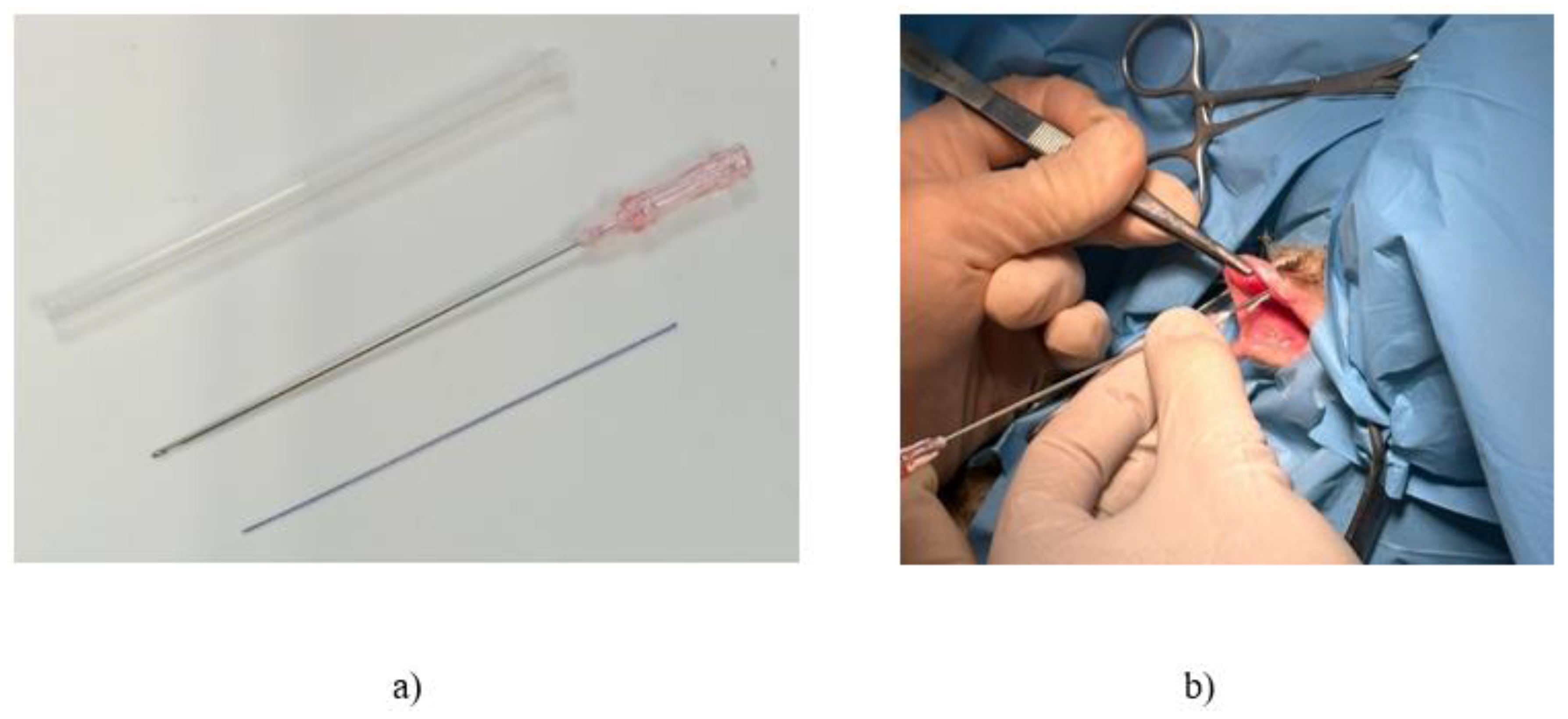

The in vivo minimally invasive procedure was performed on a sheep model, involving the insertion of commercially available biodegradable polycaprolactone (PCL) cog threads (Yastrid, China), as depicted in

Figure 1a.

Figure 1b illustrates the surgical procedure for reinforcing the vaginal canal through the insertion of commercially available cannula cog threads. Typically used in cosmetic procedures for temporary structural reinforcement, these threads were utilized in this study to strengthen the vaginal canal in sheep.

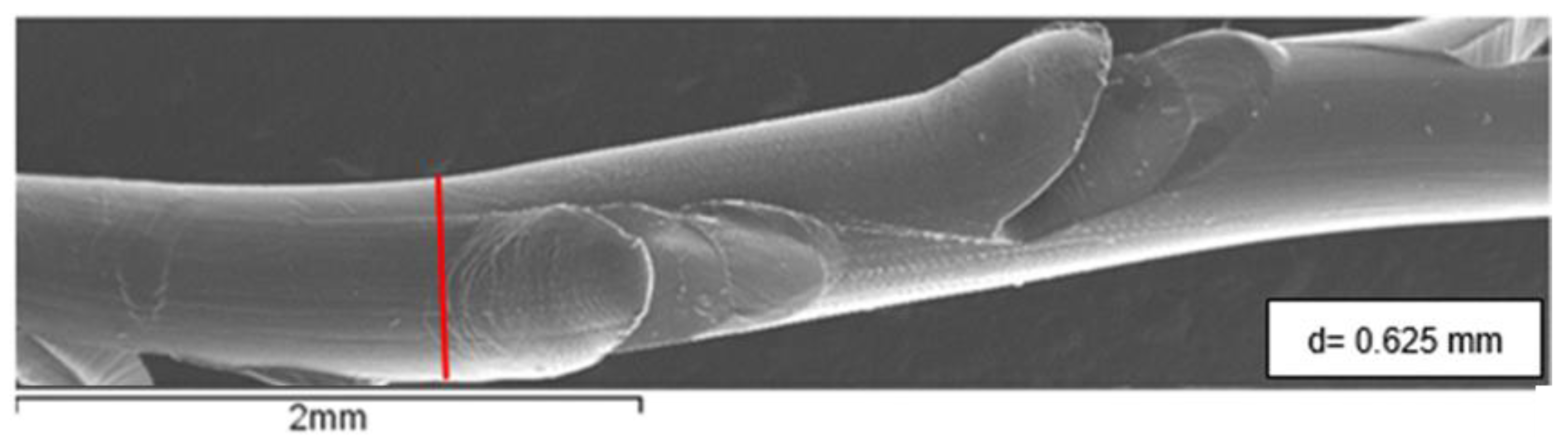

The threads used in this study are commercially available 360° 4D barb threads (PCL-19G-100), provided in sterile packs by Yastrid (Shanghai, China). Each pack contained two threads within an L-type cannula and a 19G needle, both made of stainless steel. Once implanted, these threads are expected to last between two and three years. The filament diameter of the cog threads, measured from SEM micrographs, is approximately 0.625 mm, as shown in

Figure 2.

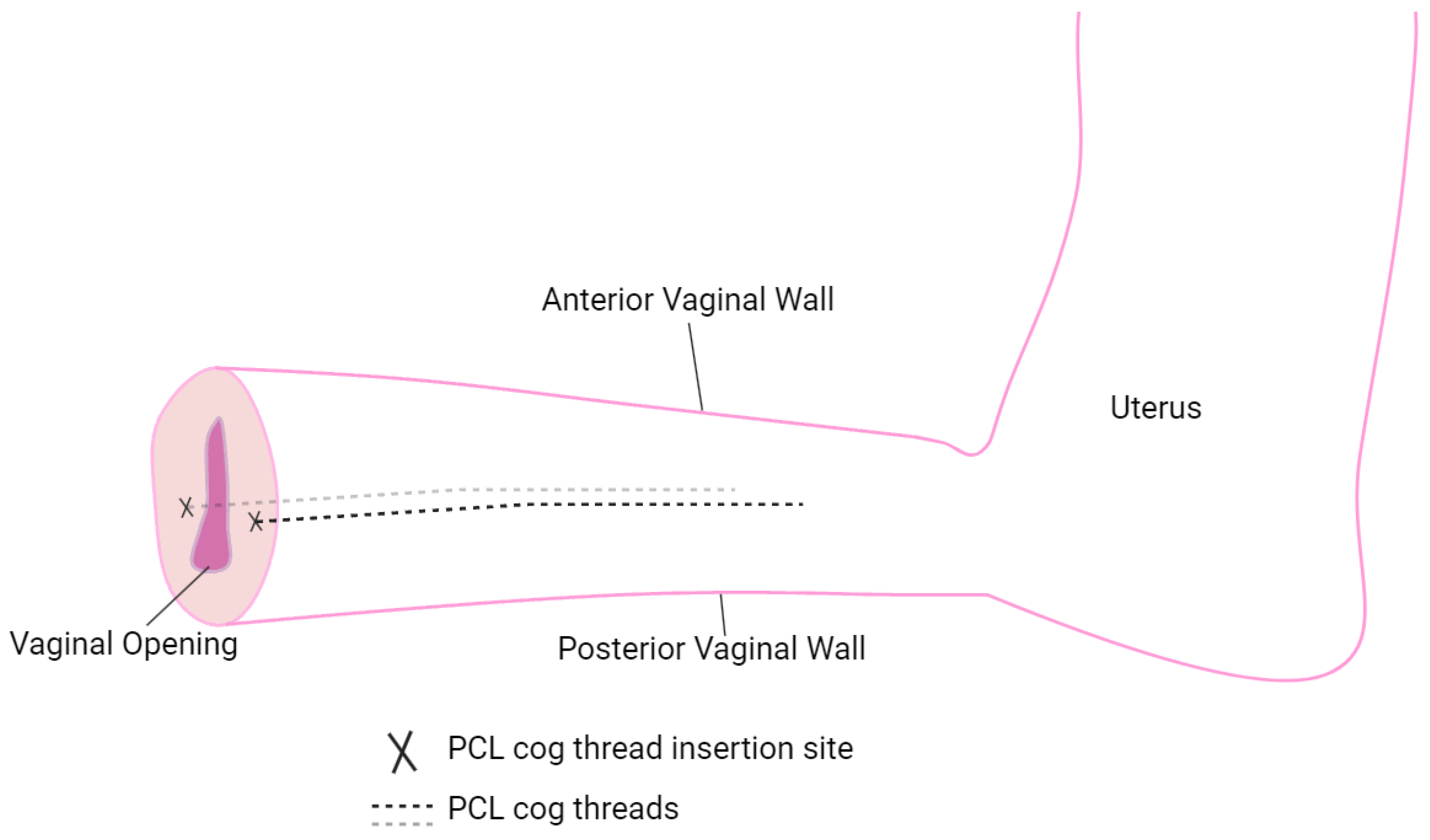

The cog threads were placed laterally (see

Figure 3, marked by "X" symbols) to ensure stable and effective placement. This lateral positioning enhanced structural support along the vaginal wall and facilitated gradual remodeling as the PCL threads degraded. This approach enabled the evaluation of reinforcement effects on intravaginal pressure distribution and wall stability during in vivo testing, while also demonstrating an adaptive strategy to accommodate anatomical constraints encountered during the procedure.

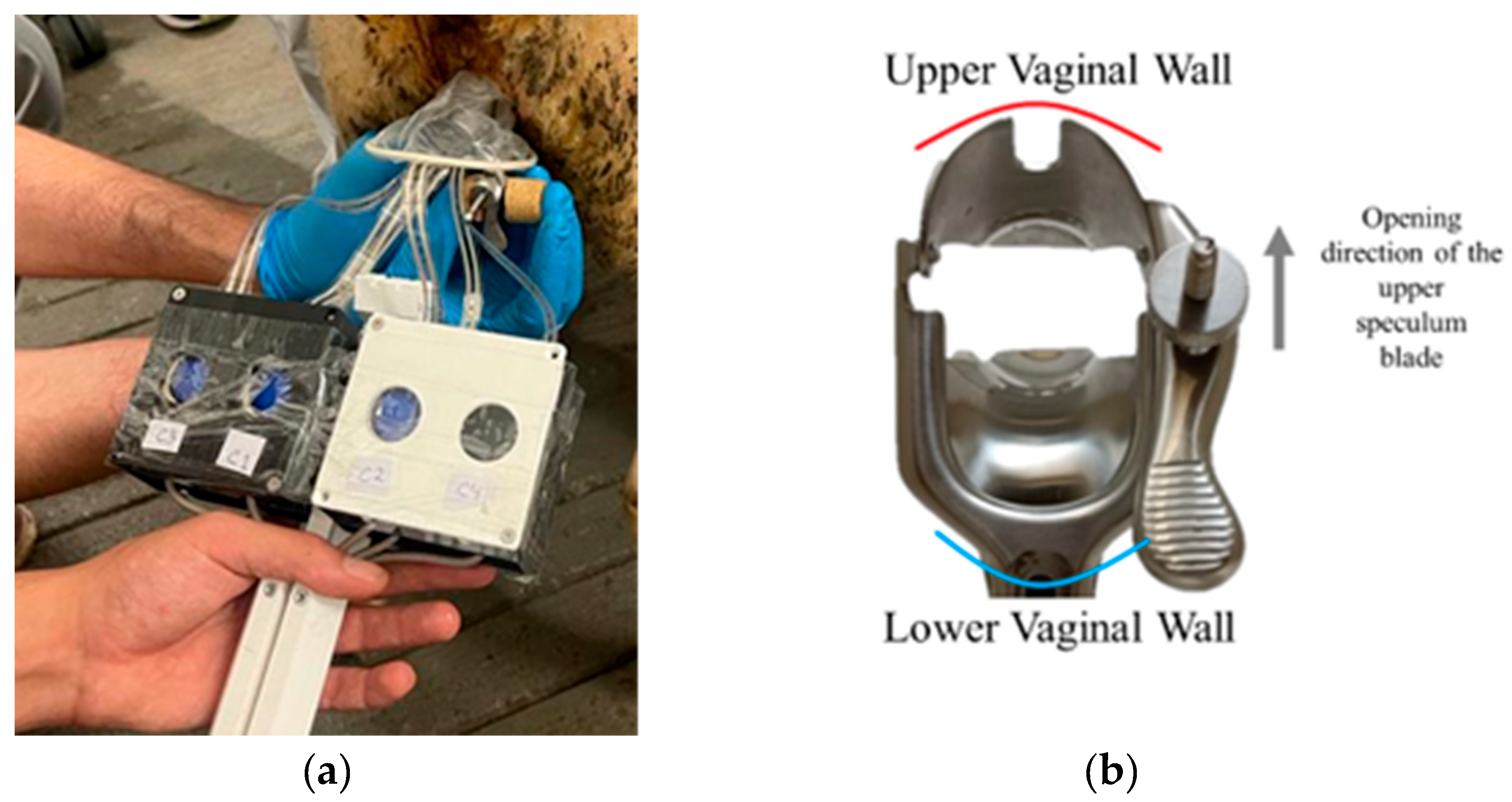

2.3. Intravaginal Force Measurement Device

A standard double-bladed stainless-steel speculum was used as the structural foundation for the diagnostic tool. The speculum was modified to lock at various openings (0 to 30 mm) and adapted to accommodate FlexiForce™ B201 Tekscan sensors (Boston, USA). These piezoresistive B201 sensors detect applied force by measuring changes in resistance, which are inversely proportional to the applied force. Their integration with USB-interface electronics and ELF™ software enabled real-time recording and visualization of force data, facilitating detailed analysis of force distribution and the role of cog thread reinforcement. The sensors were positioned on the outer surfaces of the blades, as shown in

Figure 4, with four sensors on the upper blade (S1 to S4) and another four on the lower blade (I1 to I4). However, since sensors S4 and I4 were often positioned outside the vaginal canal during most measurements, only three sensors per blade (S1 to S3 and I1 to I3) were considered for data analysis. Previous studies emphasize both the anatomical similarities and differences between the vaginal and cervical canals in humans and sheep, demonstrating their significance for medical and veterinary applications. While the vaginal and cervical structures in both species share key similarities, making the sheep a valuable model for studying human pelvic anatomy and testing medical devices, there are also notable differences. For instance, the human vaginal canal is longer and more flexible, whereas the sheep cervical canal features funnel-shaped rings and smaller openings. Despite these differences, both species possess fundamental anatomical characteristics that influence the design and application of instruments and treatments [

37,

38].

The insertion of the probe, which consists of the speculum with attached sensors, aimed to evaluate the reinforcement of the vaginal canal after the implantation of cog threads. During the measurements, a passive examination of the sheep model was performed with the speculum dilation set at 0 mm, 10 mm, 20 mm, and 30 mm in the medial position (see

Figure 5). Data was collected at each of these points to assess the capacity of the cog threads to reinforce the vaginal canal and achieve maximum strength.

Figure 5a shows the insertion of the speculum into the sheep's vaginal tissue, while

Figure 5b illustrates how the speculum was positioned within the vaginal canal. The superior blade of the speculum was placed against the upper vaginal wall, and the inferior blade was positioned against the lower vaginal wall. The sheep was awake and standing in an upright position during the procedure. Force values were recorded for 50 to 60 seconds per measurement, with three measurements conducted for each opening. During each measurement, eight values per second were collected for each sheep. The average force was first calculated for each measurement, and a final mean value was determined from the three measurements.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 software (New York, United States), with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The force values measured using the speculum at different time points (before surgery, and at 90 and 180 days post-surgery) were compared across the various speculum openings (0 mm, 10 mm, 20 mm, and 30 mm) using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

3. Results

3.1. In Vivo Force Measurements of the Vaginal Wall Before Reinforcement

Table 1 shows the mean force values before the insertion of the cog threads, including the average force values, standard deviations, and corresponding p-values. The data indicate that intravaginal force increases as the speculum openings widens, with an intravaginal force of 0.379 N at no opening or closed and 0.703 N at a 20 mm opening, representing an approximately 46% difference. In the case of a 30 mm opening, the lower variation compared to 20 mm may be associated with excessive dilation of the sheep's vaginal canal, potentially preventing full insertion of the speculum at this opening size. Statistically, there is a significant difference in the force values obtained for the 20 mm and 30 mm openings when compared to the 0 mm opening, indicating an increase in force.

The different openings will serve as control groups for comparison with the insertion of cog threads at 90 and 180 days.

Analysis of the average force measured in the superior and inferior blades revealed a difference, with higher force detected in the lower vaginal wall. The maximum variation was 24% at a 20 mm opening and 22% at a 30 mm opening (see

Table 2).

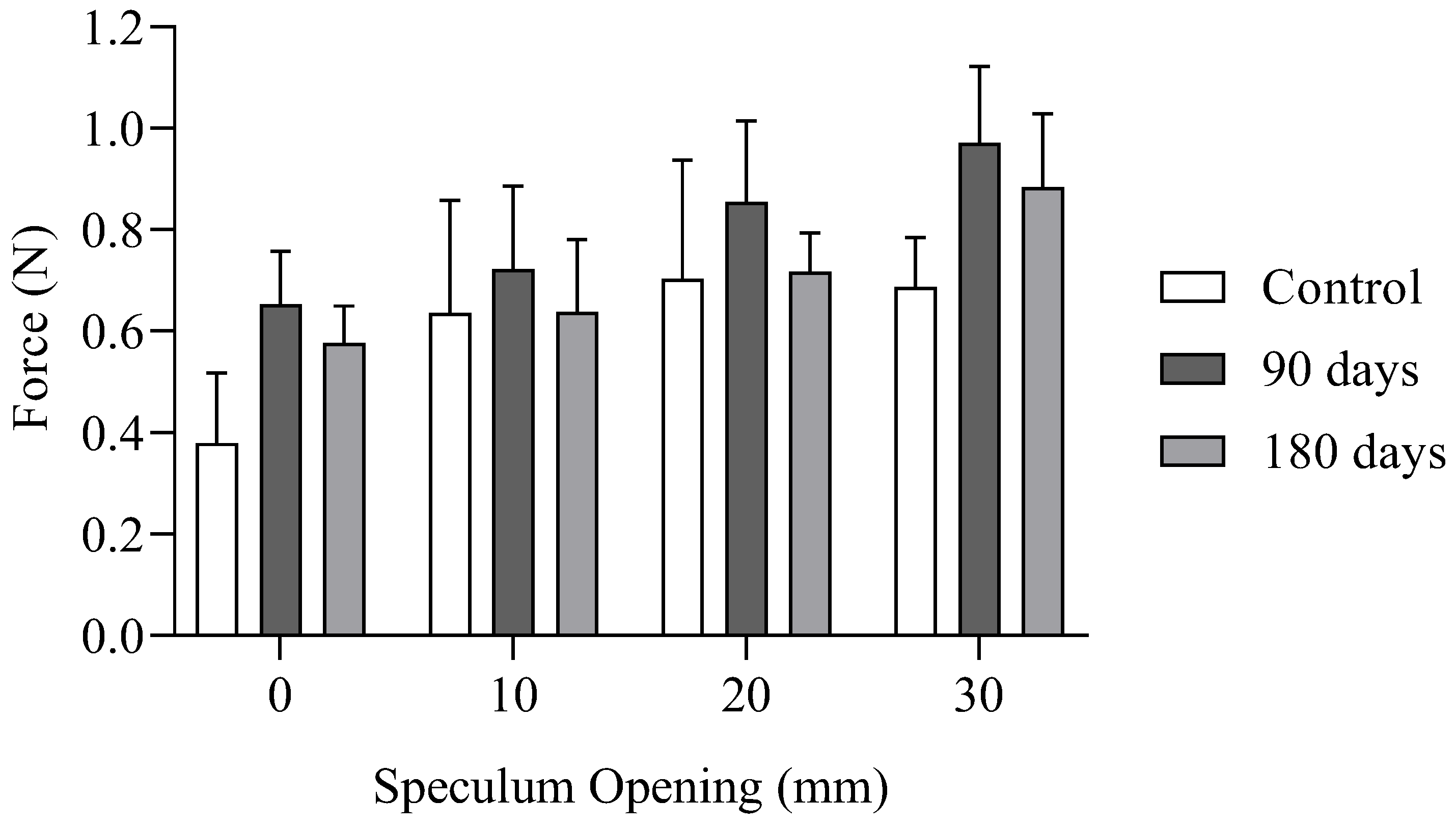

3.2. In Vivo Force Measurements of the Vaginal Wall After Reinforcement

In vivo intravaginal force measurements with vaginal wall reinforcement in the same sheep from the control group were conducted to assess the impact of PCL cog threads on reinforcing the vaginal canal. Measurements were recorded at four speculum openings (0 mm, 10 mm, 20 mm, and 30 mm) at 90 and 180 days post-implantation of cog threads.

Table 3 also presents the intravaginal average force and the variation of intravaginal force at 90 and 180 days, compared to the control group for each opening. The results show the highest variation for the case without opening (0 mm), with a variation of 42% at 90 days and 34% at 180 days. A noteworthy finding is the decrease in intravaginal force measured at 180 days, which may be linked to the gradual degradation of the cog threads over time. In this study, intravaginal force was not measured on day 0 post-implantation due to anesthesia, following veterinary surgeons’ protocol. However, degradation of the cog threads may have already started by 90 days post-implantation. A previous study evaluating biodegradable meshes printed with PCL reported significant weight loss in printed fibers at both 90 and 180 days of degradation in different media, with a weight reduction of approximately 10–27% [

24].

When comparing the force values between 90 and 180 days post-implantation, a decrease in intravaginal force was observed across all openings. This reduction was most pronounced at the 20 mm opening, with a force decrease of approximately 15.7%. This trend suggests that the degradation of the cog threads may have contributed to the decrease in reinforcement over time, aligning with previous studies that reported a weight loss of 10–27% in biodegradable PCL-based implants over similar periods [

24].

The graph in

Figure 6 presents the results from the tables above, summarizing the key findings of the intravaginal force measurements. It clearly demonstrates that there is reinforcement of the vaginal canal following the insertion of cog threads. This increase is more pronounced at 90 days post-implantation than at 180 days.

4. Discussion

The intravaginal force measurement device was previously tested and validated through ex vivo experiments and a specific in vivo case in sheep, ensuring the necessary accuracy and reliability for this study [

35,

36]. This device is capable of detecting slight variations in force distribution and mechanical integrity, which are essential for assessing the effectiveness of PCL cog thread reinforcement in the vaginal wall.

The objective of this study was to conduct an in vivo analysis by performing a surgical procedure to implant cog threads into the vaginal sheep canal and evaluate, using a probe-speculum with sensors, the intravaginal force to determine whether reinforcement occurs with the cog threads.

During the initial in vivo measurements, the device successfully identified differences in intravaginal force distribution between the upper and lower vaginal walls, as well as variations in force associated with different degrees of speculum opening. Through the speculum, the highest force was measured on the lower vaginal wall. The greater differences observed at 20 mm and 30 mm speculum openings (24% and 22%) between the upper and lower blades, compared to 10 mm and no opening (4% and 9.5%), may be attributed to the vaginal canal's mechanical response during the examination. At larger openings, the vaginal canal undergoes greater stretching, which can increase resistance and the force needed to maintain the speculum’s position. This force difference may be more pronounced under these conditions, as the inferior vaginal wall could experience increased compression or tension, leading to higher measured forces. This may also be influenced by various anatomical and physiological factors. The lower vaginal wall is typically more exposed to external forces during pelvic movements and may exhibit greater sensitivity to mechanical loads. Additionally, the positioning of the speculum during measurement may have also contributed to this discrepancy, with the inferior part potentially being more affected by the speculum's interaction with the vaginal walls. In the literature, in vivo methods have been developed to mechanically characterize the vagina, offering clinically relevant data by evaluating the tissue in its natural environment. However, these techniques typically offer only basic measurements of biomechanical properties. One of the earliest in vivo studies on vaginal tissue distensibility was conducted using a catheter balloon inflation combined with a pressure transducer. Although this method is no longer employed for a comprehensive characterization of vaginal mechanics, balloon catheterization continues to be used for estimating intravaginal pressures in vivo, offering a reference configuration for subsequent ex vivo inflation experiments [

39].

The measurements for the control group were taken at different degrees of speculum opening, showing an increase in intravaginal force as the opening degree increased. The greatest difference, approximately 46%, was observed between the 0 mm and 20 mm openings. For the 30 mm opening, the force was lower than at the 20 mm opening, which may be attributed to the maximum dilation of the sheep's vaginal canal. Previous studies highlight both the similarities and differences between the vaginal and cervical canals in humans and sheep, underscoring their relevance for medical and veterinary applications. While the vaginal and cervical structures in both species share key anatomical features, making sheep a valuable model for studying human pelvic anatomy and testing medical devices, there are distinct differences between the two. For example, the human vaginal canal is generally longer and more flexible, while the sheep cervical canal is characterized by funnel-shaped rings and smaller openings. Despite these differences, both species exhibit fundamental anatomical characteristics that play a crucial role in the design and application of medical instruments and treatments, highlighting the importance of considering these similarities and differences in translational research [

37,

40]. Previous research using a speculum to study the sheep cervical canal found an average length of 6.7 ± 1.1 cm, with 4.9 ± 1.0 funnel-shaped rings and small openings measuring 2.7 ± 1.1 mm [

37]. In contrast, measurements taken from 120 vaginal specimens included 104 without prolapse and 16 with prolapse. The average length of the distended vagina was approximately 13 ± 3 cm. The flexibility of vaginas without prolapse was around 3 ± 2.5 cm, while the flexibility of vaginas with prolapse ranged from 5.5 to 8.0 cm [

40].

In the present study, after implantation of the cog threads, an increase in intravaginal force was observed, indicating reinforcement of the vaginal wall. The most significant reinforcement was noted at 90 days post-implantation, with a force increase of approximately 42% at 0 mm opening. Although a similar trend was observed with other degrees of speculum opening, the increase was less pronounced. In comparison, a previous ex vivo study on sow vaginal tissue demonstrated a significant reinforcement of tissue, as confirmed by the ball burst test [

25]. The study reported that vaginal tissue reinforced with threads could withstand an additional 68 N of load compared to normal tissue (p < 0.05), corresponding to an approximate 45% increase in strength. While the experimental conditions differ between the two studies, the observed increase in strength from the in vivo study is of a similar order of magnitude to the ex vivo results, indicating that the reinforcement effect observed in the vaginal wall after cog thread implantation aligns with findings from tissue reinforcement in ex vivo models. Despite these methodological differences, the similarity in the order of magnitude of the obtained values reinforces the hypothesis that cog threads effectively strengthen vaginal tissue. These findings also suggest that the probe-speculum can provide accurate measurements, highlighting its potential for use in urogynecological consultations. However, it may require adaptation with integrated sensors. Its main advantages include its existing use in clinical practice, ease of handling by experienced clinical doctors, simple sensor replacement, and cost-effectiveness. Further studies are needed to establish a more precise quantitative correlation between the two experimental models and to better understand the biomechanical mechanisms involved over time. However, at 180 days post-implantation, a decrease in intravaginal force was observed compared to the measurements at 90 days, likely due to the degradation of the PCL cog threads. Specifically, the reduction in intravaginal force was 7.8% at 0 mm opening, 11.7% at 10 mm, 15.7% at 20 mm, and 7% at 30 mm. If force measurements had been taken one day after implantation and compared to those at 90 days, a potential decrease in force might have been detected, being a limitation of this study. Previous studies have shown a significant weight loss in printed fibers after both 90 and 180 days of degradation in various media, with a weight reduction ranging from approximately 10% to 27% [

24].

Several limitations should be considered in this study. One significant limitation is the lack of force measurements immediately post-implantation, which could have provided a clearer baseline for evaluating early mechanical reinforcement. Additionally, variations in force measurements may have been influenced by differences in vaginal wall elasticity and individual anatomical characteristics of the sheep, highlighting the importance of larger sample sizes in future studies to account for these individual variations. Another important consideration is the progressive degradation of PCL cog threads over time. Previous studies have reported weight loss in printed fibers ranging from 10% to 27% after 90 and 180 days of degradation in different media, including a biological fluid model (pH 7.4) and an acidic medium associated with inflammation (pH 4.3) [

24]. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the material's mechanical behavior during degradation, future studies should include additional intermediate time points. The use of lysozyme and simulated body fluid are among the media that can better replicate physiological conditions.

These results highlight the potential of PCL cog threads to enhance tissue resistance, underscoring their applicability for treating POP. PCL cog threads offer a controlled biodegradation process, providing temporary support while promoting the remodeling of native tissue [

41]. Unlike permanent synthetic meshes, which pose risks such as erosion and infection [

42], PCL cog threads gradually degrade, offering a safer, short-term reinforcement option. This approach aligns with clinical goals and may be particularly beneficial for patients who are unsuitable for permanent mesh placement. While minor risks such as inflammation or tissue stiffness may arise, ongoing research into tissue adaptation and the biomechanical effects of thread degradation will continue to improve clinical safety and efficacy.

The use of cog threads might have several advantages over traditional mesh implants in reconstructive pelvic surgeries. Although primarily used in facelifting procedures, we believe cog threads could be an effective treatment option for the early stages of POP due to several factors. This technique reduces operative times and allows for simpler wound closure, as there is no need for knot tying, and it can be performed under local anesthesia. The thread’s barbs anchor firmly into the soft tissue, eliminating the need for additional anchoring points, which could otherwise contribute to inflammatory reactions. Additionally, this technique offers quicker recovery and better sexual health outcomes compared to conventional meshes, while also preserving the possibility of future vaginal delivery. Conventional meshes are typically used in older women with no intention of childbirth, as it is not recommended to give birth after using synthetic meshes. For younger women, native repairs are often used, although they carry a higher recurrence rate [

25].

The biomechanical responses observed in the sheep model provide valuable insights for potential human applications in POP diagnostics. Future studies could explore polymer blends or modifications to the PCL thread coating to enhance tissue biocompatibility and reduce risks of inflammation or stiffness. Additionally, leveraging additive manufacturing for model optimization could lead to design improvements tailored to both animal and human anatomy, expanding their use in both research and clinical contexts.

Integrating PCL cog threads with diagnostic capabilities could represent a minimally invasive strategy for managing or delaying the onset of POP. This combined approach would offer structural support while enabling real-time monitoring and adjustments, thereby improving patient outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that integrating intravaginal force measurement sensors into a modified speculum provides a reliable and sensitive method for assessing force distribution across the vaginal wall, a crucial factor in diagnosing POP. In vivo testing confirmed the device’s effectiveness, as force measurements increased progressively with speculum dilation, accurately reflecting the vaginal wall’s natural resistance. Additionally, comparative measurements with an established probe validated the proper functioning of the modified speculum, reinforcing its accuracy and reliability.

Beyond its diagnostic capabilities, the study explored the use of biodegradable PCL cog threads for vaginal wall reinforcement. In vivo results showed significant increases in tissue resistance across multiple speculum openings, demonstrating that the cog threads provided temporary structural support while gradually integrating into the surrounding tissue. This suggests they could serve as a safer and more adaptable alternative to permanent synthetic meshes.

By combining an innovative diagnostic tool with a temporary reinforcement method, this approach offers a minimally invasive, patient-centered strategy for early POP intervention, potentially reducing recurrence rates. However, further research is needed to optimize the degradation rates and biocompatibility of PCL cog threads, particularly in human tissues, to ensure clinical safety and efficacy.

Future work should focus on refining the device’s ergonomic design, enhancing sensor accuracy, and evaluating its performance across diverse anatomical contexts. Additive manufacturing could facilitate customization tailored to individual patient anatomy, further improving clinical applicability.

Ultimately, this study advances POP diagnosis and treatment by merging diagnostic precision with temporary reinforcement. These innovations pave the way for real-time monitoring and individualized interventions, which could reduce the need for repeat surgeries and improve long-term patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding by Ministério da Ciência Tecnologia, e Ensino Superior, FCT, Portugal, under grants 2023.00640.BD, project PRECOGFIL-PTDC/EMD-EMD/2229/2020 and from Stimulus of Scientific Employment 2021.00077.CEECIND. This work was supported by FCT, through INEGI, under LAETA, project UIDB/50022/2020, LA/P/0079/2020 and UIDP/50022/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no financial, professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be constructed as influencing the position.

References

- Roch, M.; Gaudreault, N.; Cyr, M.-P.; Venne, G.; Bureau, N.J.; Morin, M. The Female Pelvic Floor Fascia Anatomy: A Systematic Search and Review. Life 2021, 11, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, T. Potential Molecular Targets for Intervention in Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haylen, B.T.; de Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) Joint Report on the Terminology for Female Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 2010, 29, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, R.; Linder, B.J. Evaluation and Management of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Mayo Clin Proc 2021, 96, 3122–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamblin, G.; Delorme, E.; Cosson, M.; Rubod, C. Cystocele and Functional Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor: Review and Update of the Various Theories. Int Urogynecol J 2016, 27, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laganà, A.S.; La Rosa, V.L.; Rapisarda, A.M.C.; Vitale, S.G. Pelvic Organ Prolapse: The Impact on Quality of Life and Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology 2018, 39, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, T.; Li, M.; Huang, Y.; Xue, L.; Zhu, Q.; Gao, X.; Wu, M. Global Burden and Trends of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Associated with Aging Women: An Observational Trend Study from 1990 to 2019. Front Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J.A.; Gunasekera, P. Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Incontinence in Developing Countries: Review of Prevalence and Risk Factors. Int Urogynecol J 2011, 22, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLancey, J.O.L. The Hidden Epidemic of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: Achievable Goals for Improved Prevention and Treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005, 192, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, S.L.; Clark, A.; Nygaard, I.; Aragaki, A.; Barnabei, V.; McTiernan, A. Pelvic Organ Prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: Gravity and Gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002, 186, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. P. Dietz Pelvic Organ Prolapse - a Review; 7th ed.; Australian family physician, 2015; Vol. 44.

- Tunn, R.; Baeßler, K.; Knüpfer, S.; Hampel, C. Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Women. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.; Lewicky-Gaupp, C. Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2022, 51, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, M.D.; Maher, C. Epidemiology and Outcome Assessment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 2013, 24, 1783–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, U.; Raz, S. Emerging Concepts for Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery: What Is Cure? Curr Urol Rep 2011, 12, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehrani, F.R.; Hashemi, S.; Simbar, M.; Shiva, N. Screening of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse without a Physical Examination; (a Community Based Study). BMC Womens Health 2011, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Martin, B.; Markowitz, M.A.; Myers, E.R.; Lundsberg, L.S.; Ringel, N. Estimated National Cost of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery in the United States. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA FDA Takes Action to Protect Womens Health, Orders Manufacturers of Surgical Mesh Intended for Transvaginal Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse to Stop Selling All Devices.

- Cunha, M.N.B. da; Rynkevic, R.; Silva, M.E.T. da; Moreira da Silva Brandão, A.F.; Alves, J.L.; Fernandes, A.A. Melt Electrospinning Writing of Mesh Implants for Pelvic Organ Prolapse Repair. 3D Print Addit Manuf 2022, 9, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterk, S.; Silva, M.E.T.; Fernandes, A.A.; Huß, A.; Wittek, A. Development of New Surgical Mesh Geometries with Different Mechanical Properties Using the Design Freedom of 3D Printing. J Appl Polym Sci 2023, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hympánová, L.; Rynkevic, R.; Román, S.; Mori da Cunha, M.G.M.C.; Mazza, E.; Zündel, M.; Urbánková, I.; Gallego, M.R.; Vange, J.; Callewaert, G.; et al. Assessment of Electrospun and Ultra-Lightweight Polypropylene Meshes in the Sheep Model for Vaginal Surgery. Eur Urol Focus 2020, 6, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, M.F.; Martins, J.A.P.; Pinheiro, F.; Ferreira, N.M.; Brandão, S.; Alves, J.L.; Fernandes, A.A.; Parente, M.P.L.; Silva, M.E. Optimizing Melt Electrowriting Prototypes for Printing Non-medical and Medical Grade Polycaprolactone Meshes in Prolapse Repair. J Appl Polym Sci 2025, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, M.F.R.; Martins, J.A.P.; Pinheiro, F.; Ferreira, N.M.; Brandão, S.; Alves, J.L.; Fernandes, A.A.; Parente, M.P.L.; Silva, M.E.T. Medical- and Non-Medical-Grade Polycaprolactone Mesh Printing for Prolapse Repair: Establishment of Melt Electrowriting Prototype Parameters. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 9670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynkevic, R.; Silva, M.E.T.; Martins, P.; Mascarenhas, T.; Alves, J.L.; Fernandes, A.A. Characterisation of Polycaprolactone Scaffolds Made by Melt Electrospinning Writing for Pelvic Organ Prolapse Correction - a Pilot Study. Mater Today Commun 2022, 32, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.; Martins, P.; Silva, E.; Hympanova, L.; Rynkevic, R. Cog Threads for Transvaginal Prolapse Repair: Ex-Vivo Studies of a Novel Concept. Surgeries 2022, 3, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.A.; Goldman, R.H. Barbed Suture: A Review of the Technology and Clinical Uses in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2013, 6, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gilyadova, A.; Ishchenko, A.; Puchkova, E.; Mershina, E.; Petrovichev, V.; Reshetov, I. Diagnostic Value of Dynamic Magnetic Resonance Imaging (DMRI) of the Pelvic Floor in Genital Prolapses. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLANCEY, J.O.L. Anatomy and Biomechanics of Genital Prolapse. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1993, 36, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.; Caccia, G. Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Pathophysiology and Epidemiology. In; 2018; pp. 19–30.

- Samantray, S.R.; Mohapatra, I. Study of the Relationship Between Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) Staging and Decubitus Ulcer in Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Cureus 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, V.; van Raalte, H.; Sarvazyan, A.P. Vaginal Tactile Imaging. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2010, 57, 1736–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaderrama, N.M.; Nager, C.W.; Liu, J.; Pretorius, D.H.; Mittal, R.K. The Vaginal Pressure Profile. Neurourol Urodyn 2005, 24, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.A.; Araújo, F.M.; Mascarenhas, T.; Natal Jorge, R.M.; Fernandes, A.A. Dynamic Assessment of Women Pelvic Floor Function by Using a Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor System.; Gannot, I., Ed.; February 9 2006; p. 60830H.

- Parkinson, L.A.; Gargett, C.E.; Young, N.; Rosamilia, A.; Vashi, A. V.; Werkmeister, J.A.; Papageorgiou, A.W.; Arkwright, J.W. Real-Time Measurement of the Vaginal Pressure Profile Using an Optical-Fiber-Based Instrumented Speculum. J Biomed Opt 2016, 21, 127008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, F.; Silva, M.E.; Fernandes, A.A. Prototype of a Medical Device for Measuring Intravaginal Forces. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 7th Portuguese Meeting on Bioengineering (ENBENG); IEEE, June 22 2023; pp. 124–127. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, F.; Silva, M.E.; Fernandes, A.A.; Coelho, A. Prototype of a Medical Device: Intravaginal Force Measurement Device. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th Congress of the Portuguese Society of Biomechanics; Martins, A., Roseiro, L., Messias, A.L., Gomes, B., Almeida, H., Castro, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023; pp. 289–299.

- Halbert, G.W.; Dobson, H.; Walton, J.S.; Buckrell, B.C. The Structure of the Cervical Canal of the Ewe. Theriogenology 1990, 33, 977–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Matthes, A. do C.; Zucca Matthes, G. Measurement of Vaginal Flexibility and Its Involvement in the Sexual Health of Women. J Womens Health Care 2016, 05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubik, J.; Alperin, M.; De Vita, R. The Biomechanics of the Vagina: A Complete Review of Incomplete Data. npj Women’s Health 2025, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Matthes, A. do C.; Zucca Matthes, G. Measurement of Vaginal Flexibility and Its Involvement in the Sexual Health of Women. J Womens Health Care 2016, 05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, X.; Zhu, T.; Lu, S. Electrospun PCL/Collagen Hybrid Nanofibrous Tubular Graft Based on Post-Network Bond Processing for Vascular Substitute. Biomaterials Advances 2022, 139, 213031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCraith, E.; Cunnane, E.M.; Joyce, M.; Forde, J.C.; O’Brien, F.J.; Davis, N.F. Comparison of Synthetic Mesh Erosion and Chronic Pain Rates after Surgery for Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. Int Urogynecol J 2021, 32, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).