Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

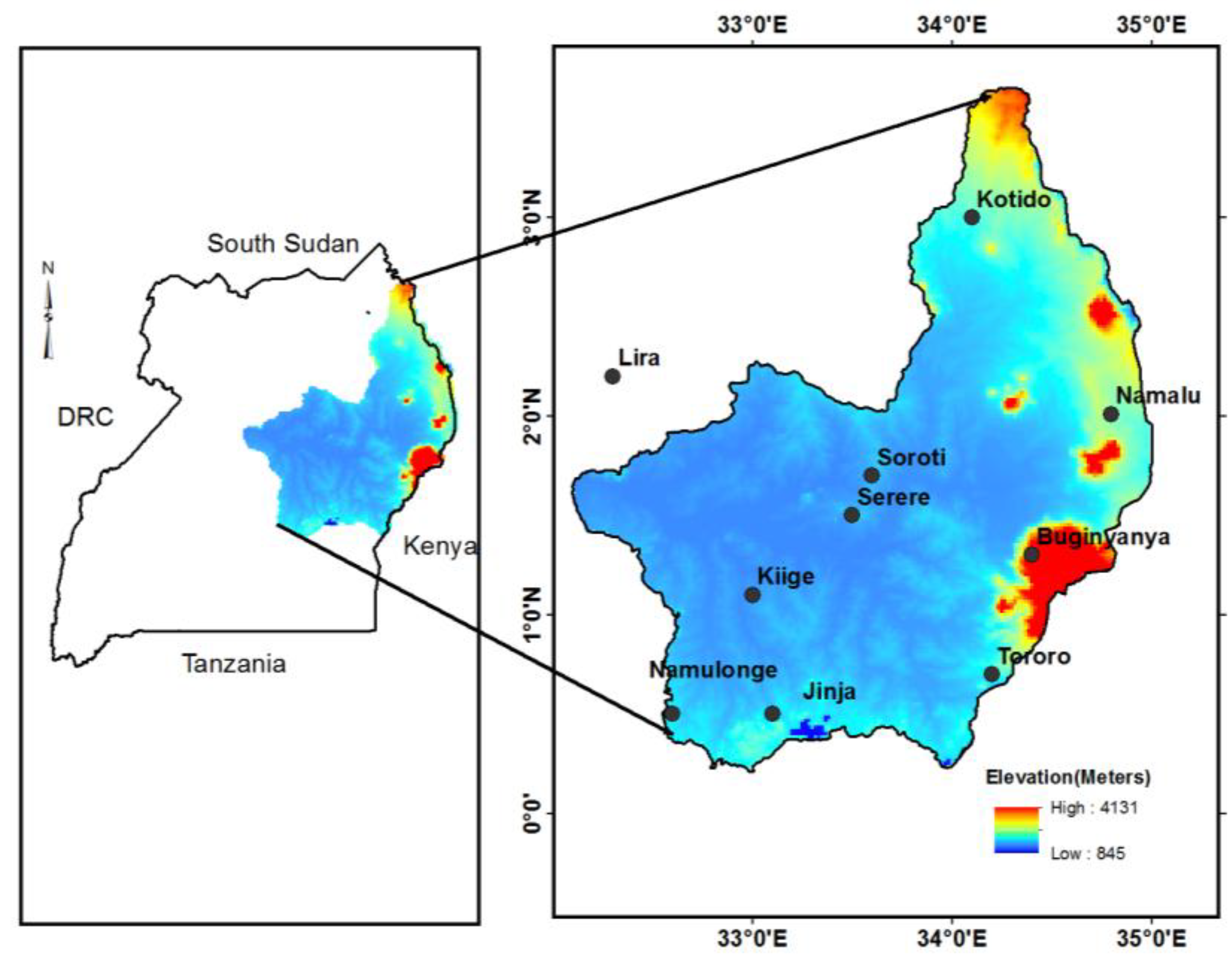

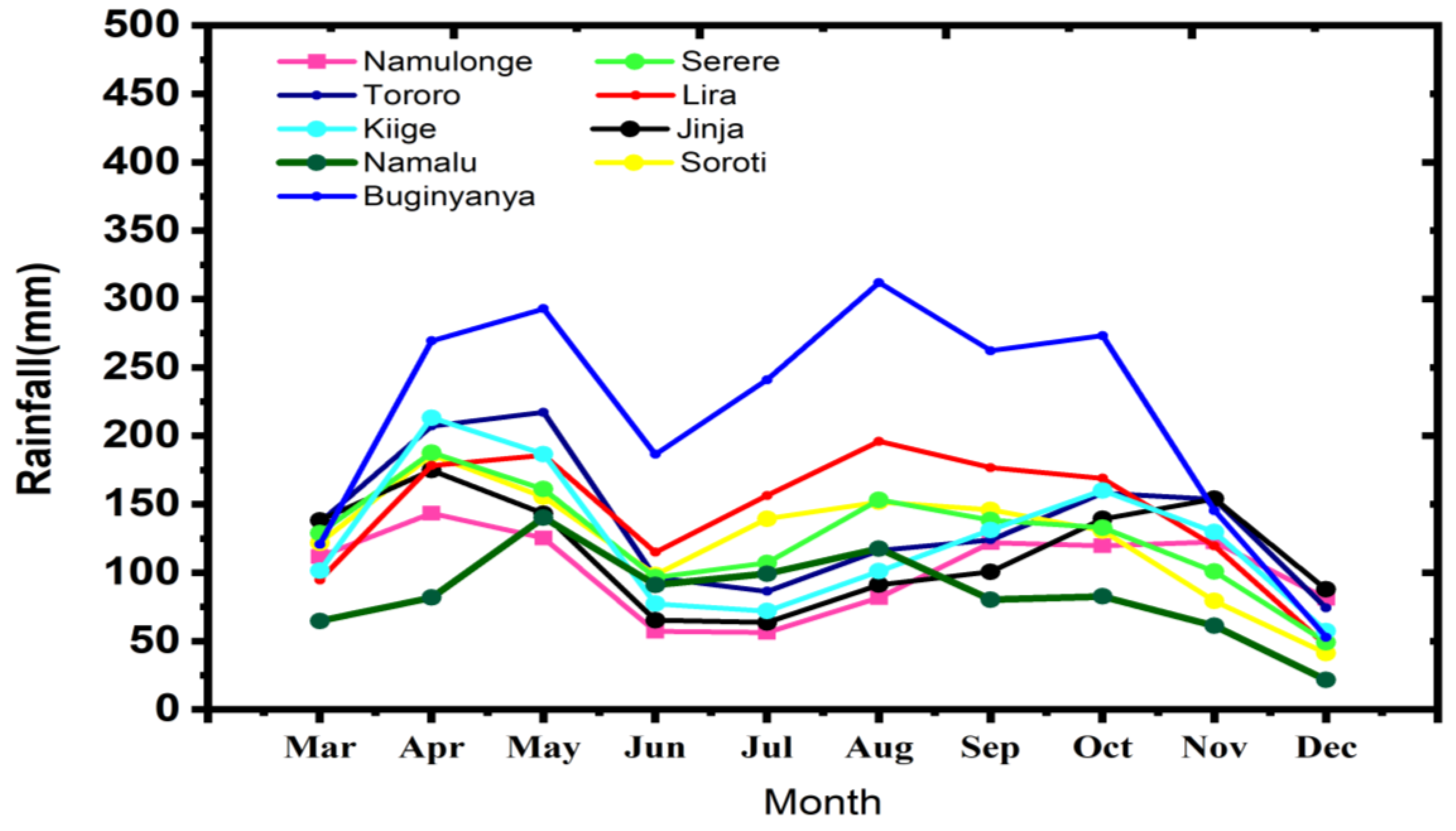

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.1.1. Observed Station Climate Data

3.1.2. Climate Hazards Group Infrared Precipitation with Stations Data (CHIRPS)

3.1.3. TAMSAT Precipitation Data

3.2. Methods

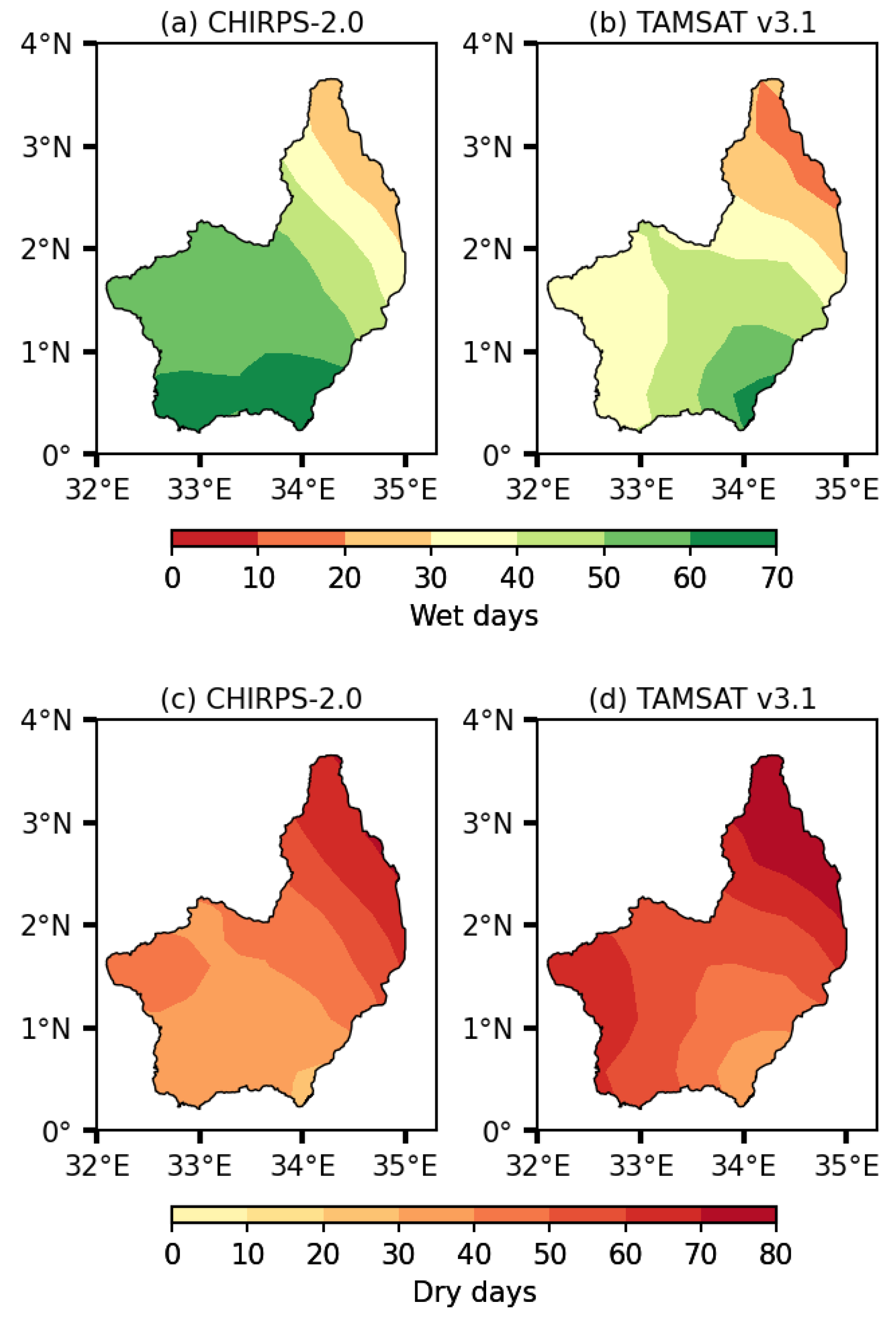

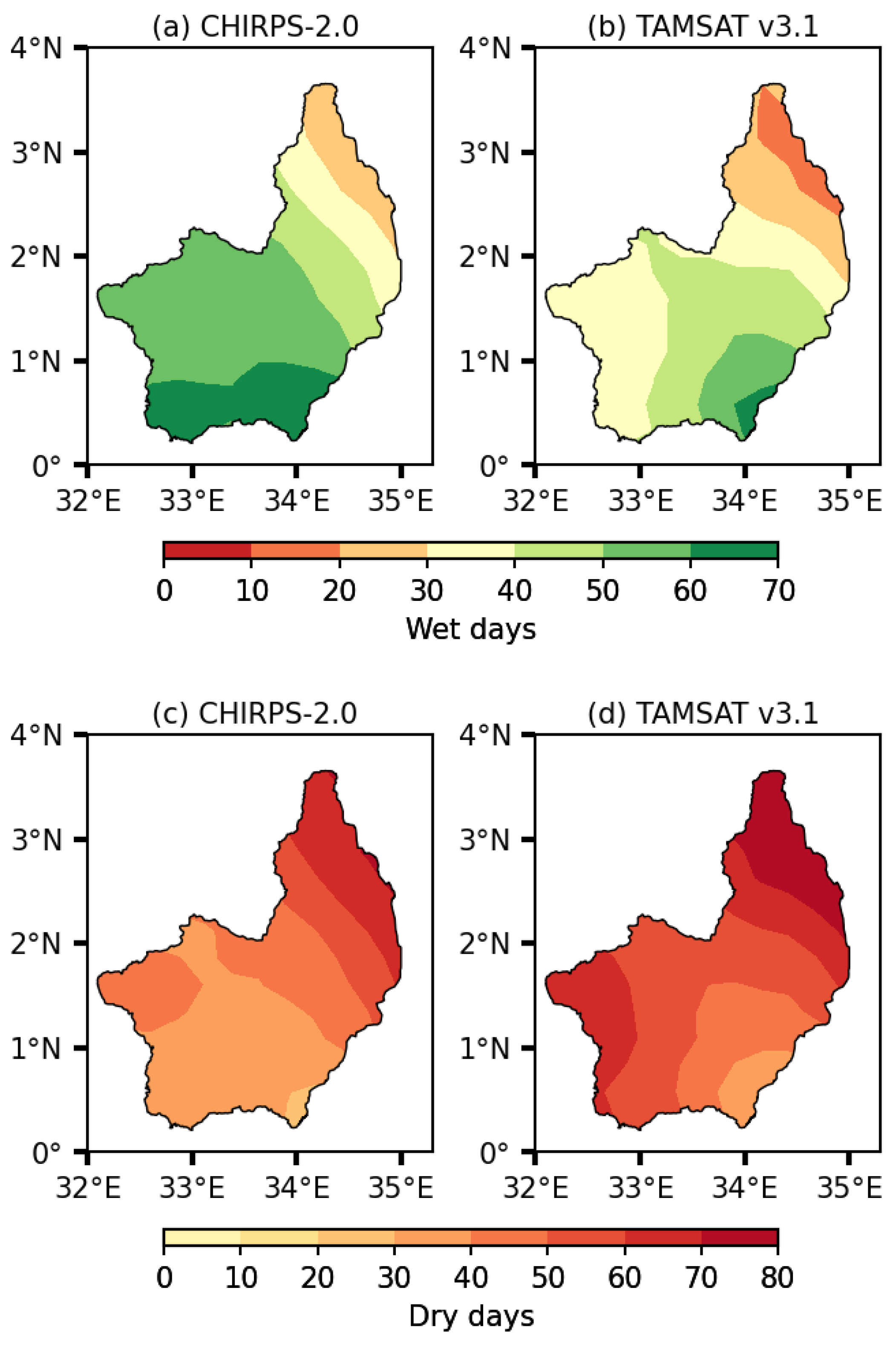

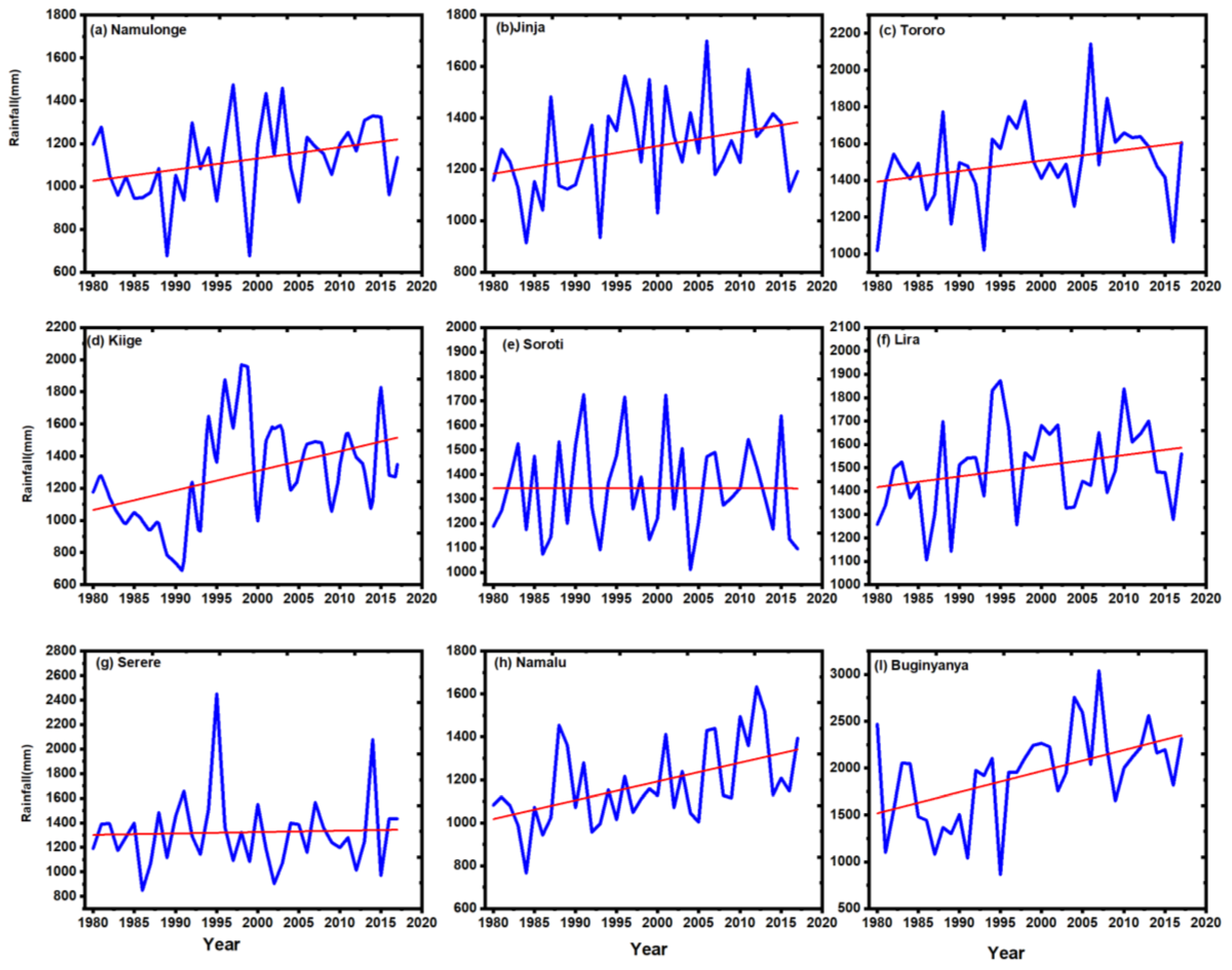

3.2.1. Number WET/DRY Days over MAM and SOND Rainfall Seasons

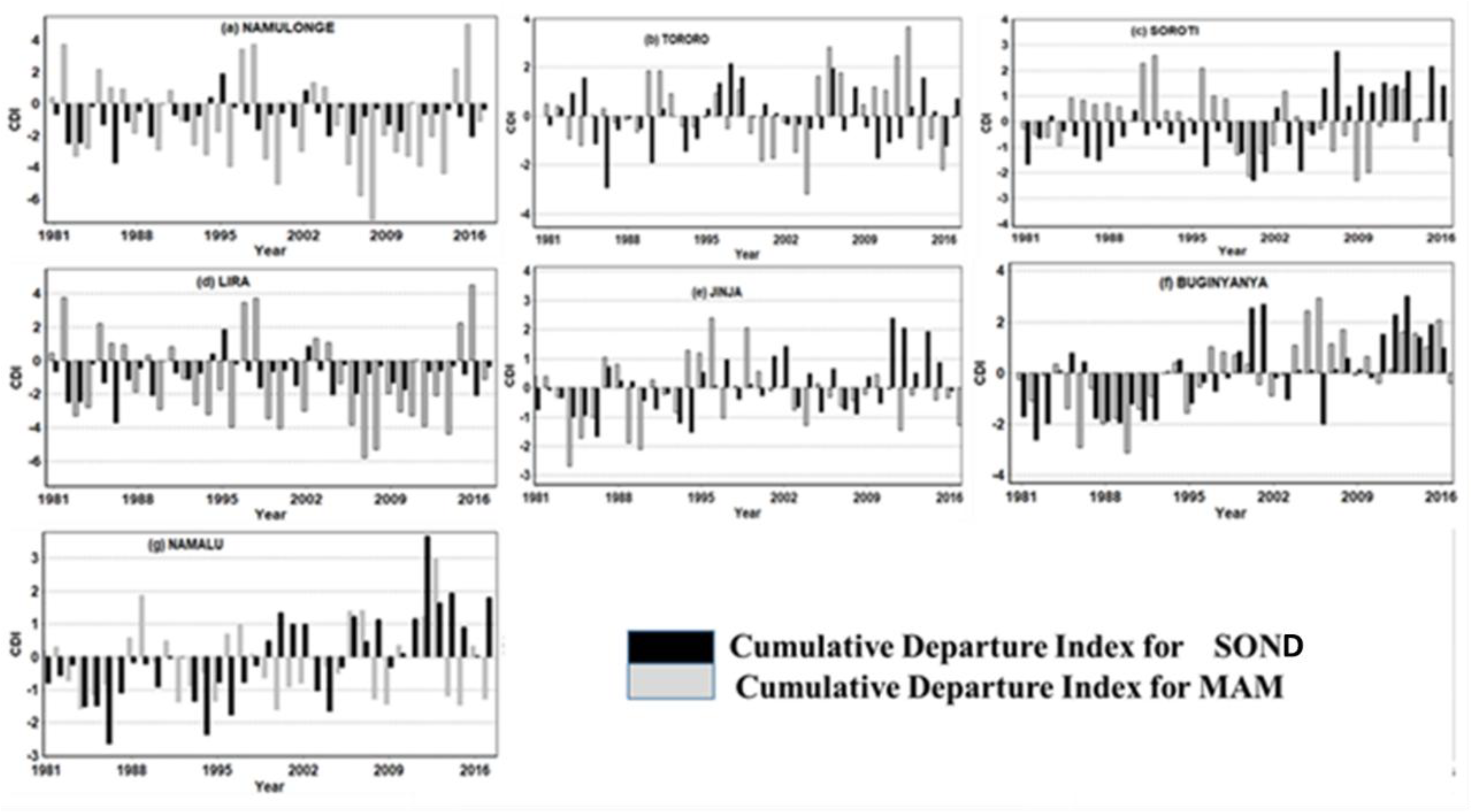

3.2.2. Cumulative Departure Index (CDI) for 1981-2017

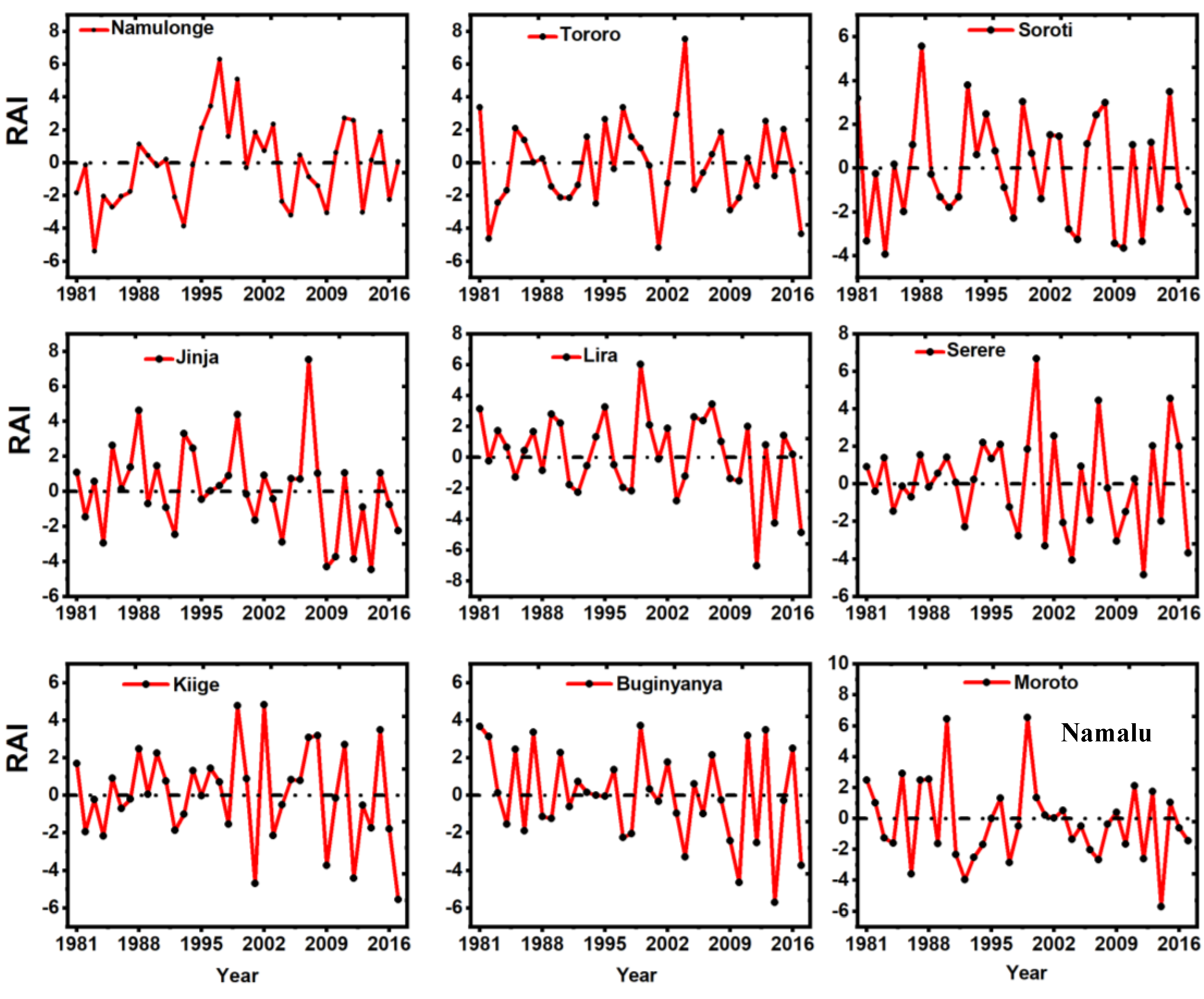

3.2.3. Rainfall Anomaly Index (RAI) for 1981-2017

4. Results

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Min, S.; Zhang, X.; Zwiers, F.W.; Hegerl, G.C. Human Contribution to More-Intense Precipitation Extremes. Nature 2011, 470, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; 2012.

- IPCC; Pachauri, R.K.; IPCC; Pachauri, R.K.; IPCC; Pachauri, R.K.; IPCC; Pachauri, R.K. CLIMATE CHANGE 2014,Synthesis Report; 2014.

- Adhikari, U.; Nejadhashemi, A.P.; Woznicki, S.A. Climate Change and Eastern Africa : A Review of Impact on Major Crops. Food Energy Secur. 2015, 4, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazroui, M.; Saeed, F.; Saeed, S.; Islam, M.N.; Ismail, M. Projected Change in Temperature and Precipitation Over Africa from CMIP6. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 4, 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwagira, U.; Yasin, I. East African Journal of Environment and Natural Resources Review of the Past, Current, and the Future Trend of the Climate Change and Its Impact in Uganda. East African J. Environ. Nat. Resour. 2022, 5, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Burke, M.B.; Tebaldi, C.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Falcon, W.P.; Rosamond, L. Naylor Prioritizing Climate Change Adaptation Needs for Food Security in 2030. Science 2008, 319, 607–610. [Google Scholar]

- Ongoma Victor, Haishan Chen, G.W.O. Variability of Extreme Weather Events over the Equatorial East Africa , a Case Study of Rainfall in Kenya and Uganda. Theorectical Appl Climatol. 2018, 295–308. [CrossRef]

- GoU; UNFPA The State Of Uganda Population Report 2009: Addressing the Effects of Climate Change on Migration; 2009.

- Macleod David, C.C.; Macleod, D.; Caminade, C. The Moderate Impact of the 2015 El Ni ñ o over East Africa and Its Representation in Seasonal Reforecasts. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 7989–8001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, P.I.; Wainwright, C.M.; Dong, B.; Maidment, R.I.; Wheeler, K.G.; Gedney, N.; Hickman, J.E.; Madani, N.; Folwell, S.S.; Abdo, G.; et al. Drivers and Impacts of Eastern African Rainfall Variability. Nat. Rev. earth &environment. [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.K.; Owiyo, T.; Jones, P.G.; Owiyo, T.; Kruska, R.L.; Herrero, M.; Orindi, V.; Bhadwal, S.; Kristjanson, P.; Notenbaert, A.; et al. Climate Change and Poverty in Africa: Mapping Hotspots of Vulnerability. African J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2008, 2, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikuku, K.M.; Winowiecki, L.; Twyman, J.; Eitzinger, A.; Perez, J.G.; Mwongera, C.; Läderach, P. Climate Risk Management Smallholder Farmers ’ Attitudes and Determinants of Adaptation to Climate Risks in East Africa. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenker, W.; Lobell, D.B. Robust Negative Impacts of Climate Change. Environ. Res. Lett. 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, R.K.; Reisinger, A. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change . Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change , Geneva, Switzerland; 2007.

- AU STATE OF AFRICA ’ S POPULATION 2017 Keeping Rights of Girls, Adolescents and Young Women at the Centre of Africa’s Demographic Dividend; 2017.

- Onyutha, C.; Acayo, G.; Nyende, J. Analyses of Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Changes across the Lake Kyoga Basin in East Africa. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubialiwo, A.; Chelangat, C.; Onyutha, C. Changes in Precipitation and Evapotranspiration over Lokok and Lokere Catchments in Uganda. Bull. Atmos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atube, F.; Malinga, G.M.; Nyeko, M.; Okello, D.M.; Mugonola, B.; Omony, G.W.; Uma, I.O. Farmers ’ Perceptions of Climate Change, Long - Term Variability and Trends in Rainfall in Apac District, Northern Uganda. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2022, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyutha, C.; Acayo, G.; Nyende, J. Analyses of Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Changes across the Lake Kyoga Basin in East Africa. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyutha, C. Trends and Variability of Temperature and Evaporation over the African Continent : Relationships with Precipitation. Atmosfera 2021, 34, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obubu, J.P.; Mengistou, S.; Fetahi, T.; Alamirew, T.; Odong, R.; Ekwacu, S. Recent Climate Change in the Lake Kyoga Basin, Uganda : An Analysis Using Short-Term and Long-Term Data with Standardized Precipitation and Anomaly Indexes. 2021.

- Filahi, S.; Tanarhte, M.; Mouhir, L.; El Morhit, M.; Tramblay, Y.; Morhit, M. El; Tramblay, Y.; El Morhit, M.; Tramblay, Y.; Morhit, M. El; et al. Trends in Indices of Daily Temperature and Precipitations Extremes in Morocco. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016, 124, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Landsfeld, M.; Pedreros, D.; Verdin, J.; Shukla, S.; Husak, G.; Rowland, J.; Harrison, L.; Hoell, A.; et al. The Climate Hazards Infrared Precipitation with Stations - A New Environmental Record for Monitoring Extremes. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, C.M.; Marsham, J.H.; Keane, R.J.; Rowell, D.P.; Finney, D.L.; Black, E.; Allan, R.P. ‘Eastern African Paradox’ Rainfall Decline Due to Shorter Not Less Intense Long Rains. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidment, R.I.; Grimes, D.; Black, E.; Tarnavsky, E.; Young, M.; Greatrex, H.; Allan, R.P.; Stein, T.; Nkonde, E.; Senkunda, S.; et al. Data Descriptor : A New, Long-Term Daily Satellite-Based Rainfall Dataset for Operational Monitoring in Africa. Nat. Publ. Gr. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloiero, T.; Coscarelli, R. Analysis of the Characteristics of Dry and Wet Spells in a Mediterranean Region. Environ. Process. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendon, E.J.; Stratton, R.A.; Tucker, S.; Marsham, J.H.; Berthou, S.; Rowell, D.P.; Senior, C.A. Enhanced Future Changes in Wet and Dry Extremes over Africa at Convection-Permitting Scale. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, K. Analysis of Rainfall Climate and Evapo-Transpiration in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions of Ethiopia Using Data over the Last Half a Century. J. Arid Environ. 2006, 64, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recha, C.W.; Makokha, G.L.; Traore, P.S.; Shisanya, C.; Lodoun, T.; Sako, A. Determination of Seasonal Rainfall Variability, Onset and Cessation in Semi-Arid Tharaka District, Kenya. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2012, 108, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, E.O. A COMPARATIVE PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS OF THREE. J. Climatol. 1985, 5, 655–664. [Google Scholar]

- Hänsel, S.; Schucknecht, A.; Matschullat, J. The Modified Rainfall Anomaly Index ( MRAI ) — Is This an Alternative to the Standardised Precipitation Index ( SPI ) in Evaluating Future Extreme Precipitation Characteristics ? Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Wambugu, S.K.; Shisanya, C.A. Perceived and Actual Rainfall Trends and Variability in Eastern Uganda : Implications for Community Preparedness and Response. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Indeje, M.; Semazzi, F.H.M.; Ogallo, L.J. ENSO Signals in East African Rainfall Seasons. Int. J. Climatol. 2000, 46, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Sutcliffe, J. V; Brown, E.; John, V. The Water Balance of Lake Kyoga, Uganda The Water Balance of Lake Kyoga, Uganda. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2013, 58, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwang, B.A. ; Alex Nimusiima, Teddy Tindamanyire, Margaret N. Serwanga, Godwin Ayesiga, Moses Ojara, Fred Ssebabi, Gordon Gugwa, Yusuf Nsubuga1, R.A.; Robert Kibwika, Joseph Kiwuwa Balikudembe, Herbert Kikonyogo, Abubakar Kalema, Victor Ongoma, Aggrey Taire, Anne Kiryhabwe, Musa Semujju, Felix Einyu, Rashid Kituusa, L.A. Characteristics and Changes in SON Rainfall Over. J. Environ. Agric. Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mubiru, Drake N. ; Komutunga, Everline; Agona, Ambrose; Apok, Anne; Ngara, T. Characterising Agrometeorological Climate Risks and Uncertainties : Crop Production in Uganda. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2012, 108, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsubuga, F.W.; Rautenbach, H. Climate Change and Variability : A Review of What Is Known and Ought to Be Known For. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Camberlin, P.; Philippon, N. The East African March – May Rainy Season : Associated Atmospheric Dynamics and Predictability over the 1968 – 97 Period. J. Clim. 2002, 15, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Nandozi, C.S.; Omondi, P.; Komutunga, E.; Aribo, L.; Isubikalu, P.; Tenywa, M.M.; Box, P.O.; Zonal, M.; Unit, C.C.; Centre, A. Regional Climate Model Performance and Prediction of Seasonal Rainfall and Surface Temperature of Uganda. African Crop Sci. J. 2012, 20, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Masih, I.; Maskey, S.; Trambauer, P.; Mussá, F.E.F.; Trambauer, P. A Review of Droughts on the African Continent: A Geospatial and Long-Term Perspective. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 3635–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremeskel, G.; Tang, Q.; Sun, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. Droughts in East Africa: Causes, Impacts and Resilience. Earth-Science Rev. 2019, 193, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, D. Booth, S. Nicholson, and P.G. Reconciling Past and Future Rainfall Trends over East Africa. J. Clim. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clive A, S. The Changing Climate of Africa Part I: Introduction and Eastern Africa. In African Ecology - Benchmarks and Historical Perspectives; 2012; pp. 57–140 ISBN 9783642228711.

- Kizza, M.; Rodhe, A.; Xu, C.-Y.; Ntale, H.K.; Halldin, S. Temporal Rainfall Variability in the Lake Victoria Basin in East Africa during the Twentieth Century. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2009, 98, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsubuga, F.W.N.W.N.W.; Olwoch, J.M.; Rautenbach, C.J. de W. Climatic Trends at Namulonge in Uganda: 1947-2009. J. Geogr. Geol. 2011, 3, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, N.H.; Vinayachandran, P.N. A Dipole Mode in the Tropical Indian Ocean. Nature 1999, 401, 360–363. [Google Scholar]

- Behera, S.K.; Luo, J.J.; Masson, S.; Delecluse, P.; Gualdi, S.; Navarra, A.; Yamagata, T. Paramount Impact of the Indian Ocean Dipole on the East African Short Rains: A CGCM Study. J. Clim. 2005, 18, 4514–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwang, B.A.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Gao, C.; Bob Alex Ogwang, Haishan Chen, Xing Li, and C. G. The Influence of Topography on East African October to December Climate: Sensitivity Experiments with RegCM4. Adv. Meteorol. 2014, 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAPA Climate Change: Uganda National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPA). 2007.

- Ayugi, B.; Tan, G.; Rouyun, N.; Zeyao, D.; Ojara, M.; Mumo, L.; Babaousmail, H.; Ongoma, V. Evaluation of Meteorological Drought and Flood Scenarios over Kenya, East Africa. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, F.; Mario, M.; Sandra, A. Regional Landsat-Based Drought Monitoring from 1982 to 2014. Climate 2015, 3, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, B.; Dewitt, D.G. A Recent and Abrupt Decline in the East African Long Rains. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Borlace, S.; Lengaigne, M.; Rensch, P. Van; Collins, M. Increasing Frequency of Extreme El Niño Events Due to Greenhouse Warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S.E. Climate and Climatic Variability of Rainfall over Eastern Africa. Rev. Geophys. 2017, 55, 590–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACF 2015/ 16 El Nino Event Global Report. Action Against Hunger (ACF UK) Greenwich High Road London, SE10 8JA; 2015.

- Ntale, H.K.; Gan, T.Y. East African Rainfall Anomaly Patterns in Association with El Niño/Southern Oscillation. J. Clim. 2004, 9, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNISDR Progress and Challenges in Disaster Risk Reduction: A Contribution towards the Development of Policy Indicators for the Post-2015 Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction - UNISDRUNISDR. (2014). Progress and Challenges in Disaster Risk Reduction: A Contribut; 2014.

| Stations | Longitude (degree) |

Latitude (degree) |

Elevation (meters) |

Data period (Years) |

Rainfall zones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Namulonge | 32.6 | 0.5 | 1128.3 | 1981- 2017 | B |

| Tororo | 34.2 | 0.7 | 1176.0 | 1981- 2017 | D |

| Soroti | 33.6 | 1.7 | 1115.8 | 1981-2017 | E |

| Jinja | 33.1 | 0.5 | 1175.1 | 1981-2017 | A2 |

| Lira | 32.3 | 2.2 | 1120.2 | 1981-2017 | I |

| Serere | 33.5 | 1.5 | 1098.0 | 1961-2017 | E |

| Kiige | 33.0 | 1.1 | 1089.4 | 1981-2017 | B |

| Buginyanya | 34.4 | 1.3 | 1875.0 | 1981-2017 | F |

| Kotido | 34.1 | 3.0 | 1219.5 | 1981-2017 | G |

| Namalu | 34.8 | 2.0 | 1274.4 | 1981-2017 | L |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).