Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

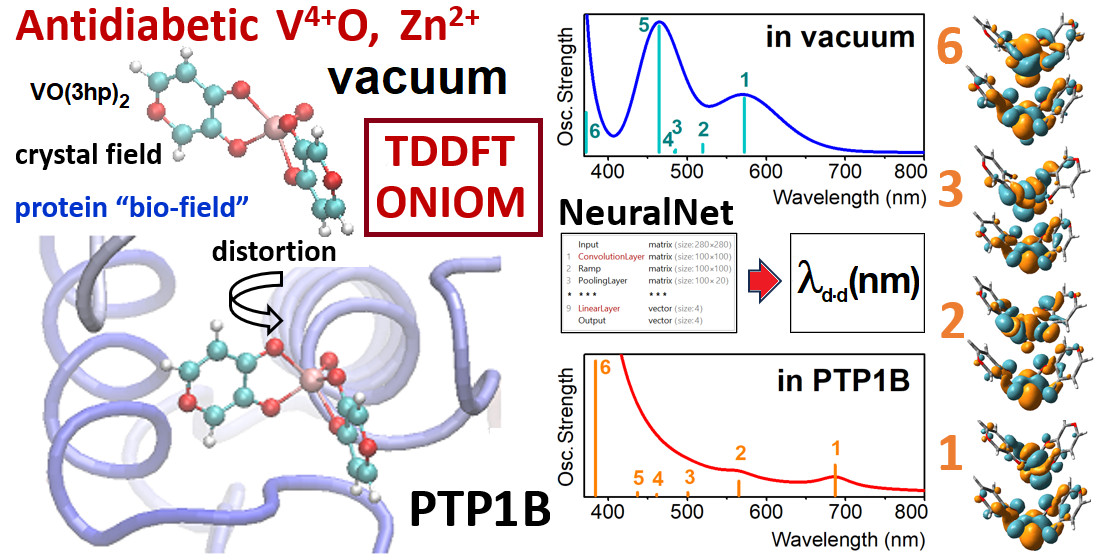

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

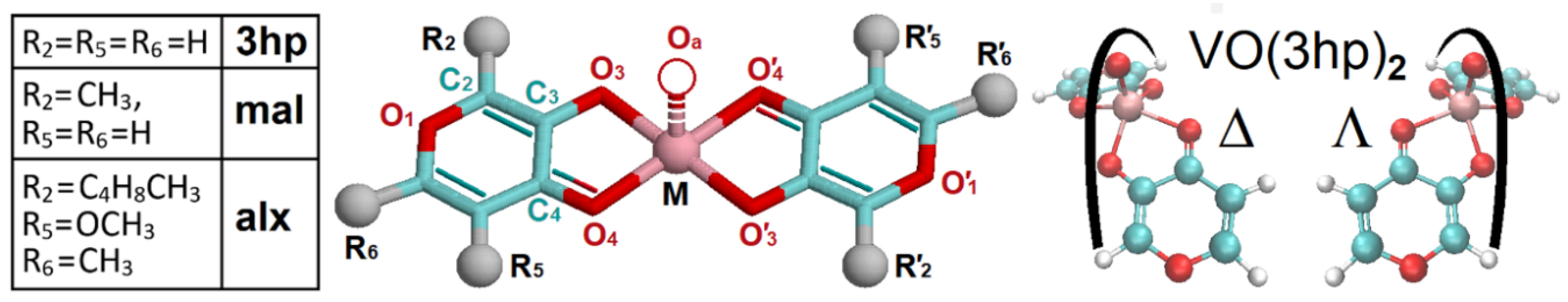

Structural Definition of the Complexes

Dynamics of the Complexes in Vacuum and in Local Water Clusters

DFT Calculations

Protein Structures

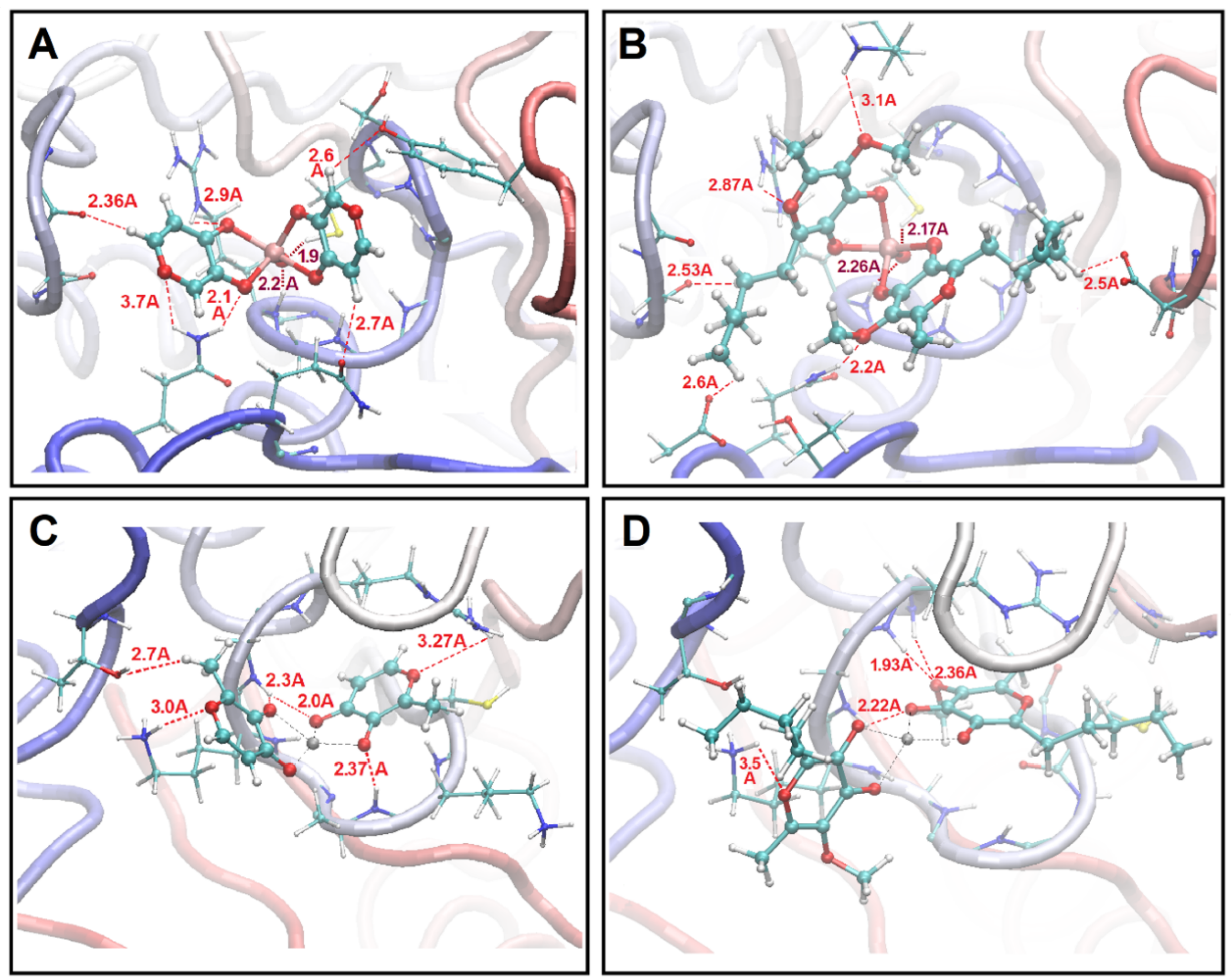

Docking and ONIOM Studies

Results and Discussion

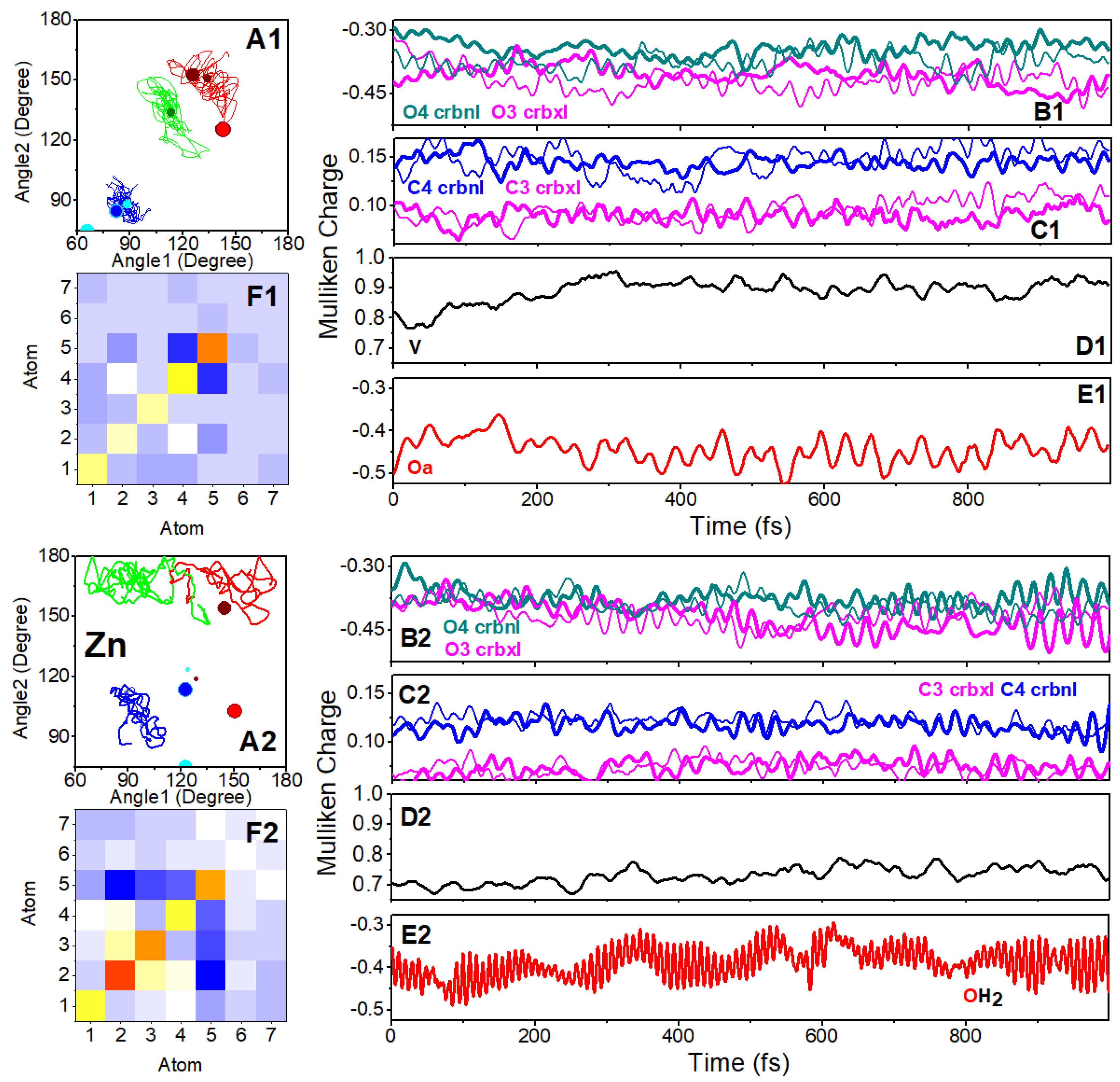

Dynamics of Complexes in Water Clusters

Structure upon Binding to Proteins

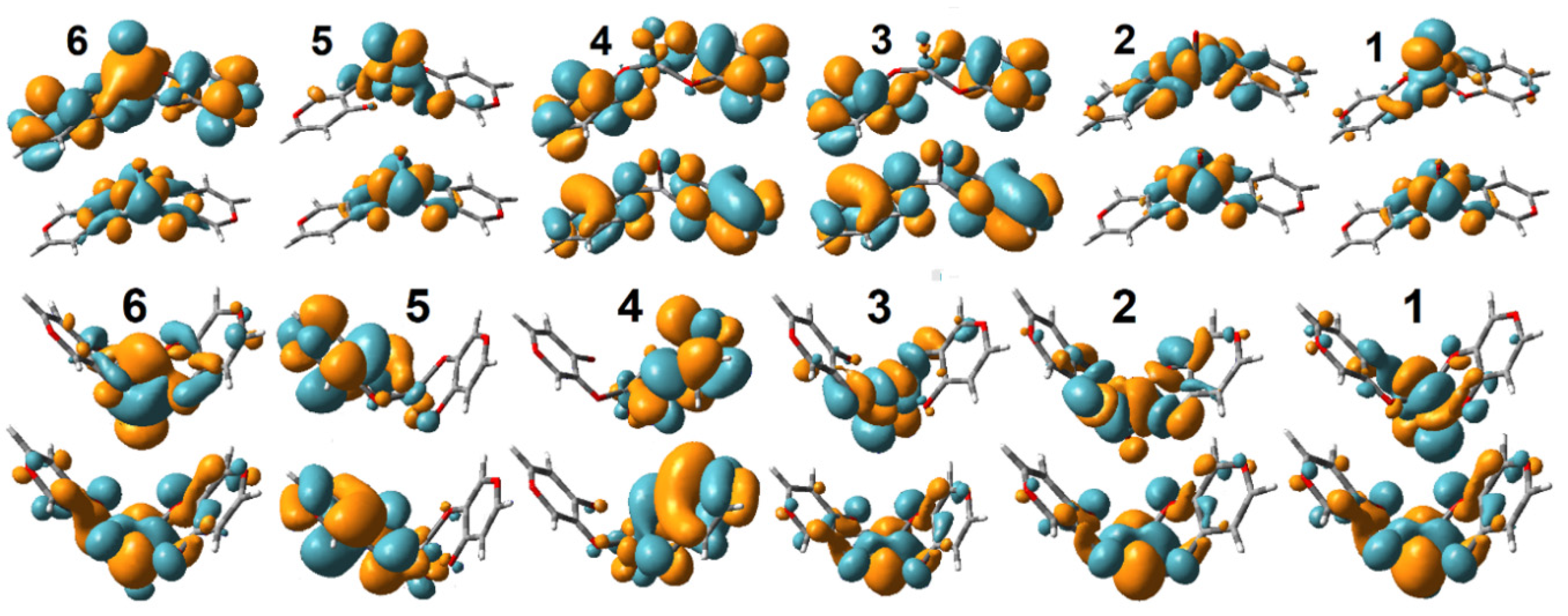

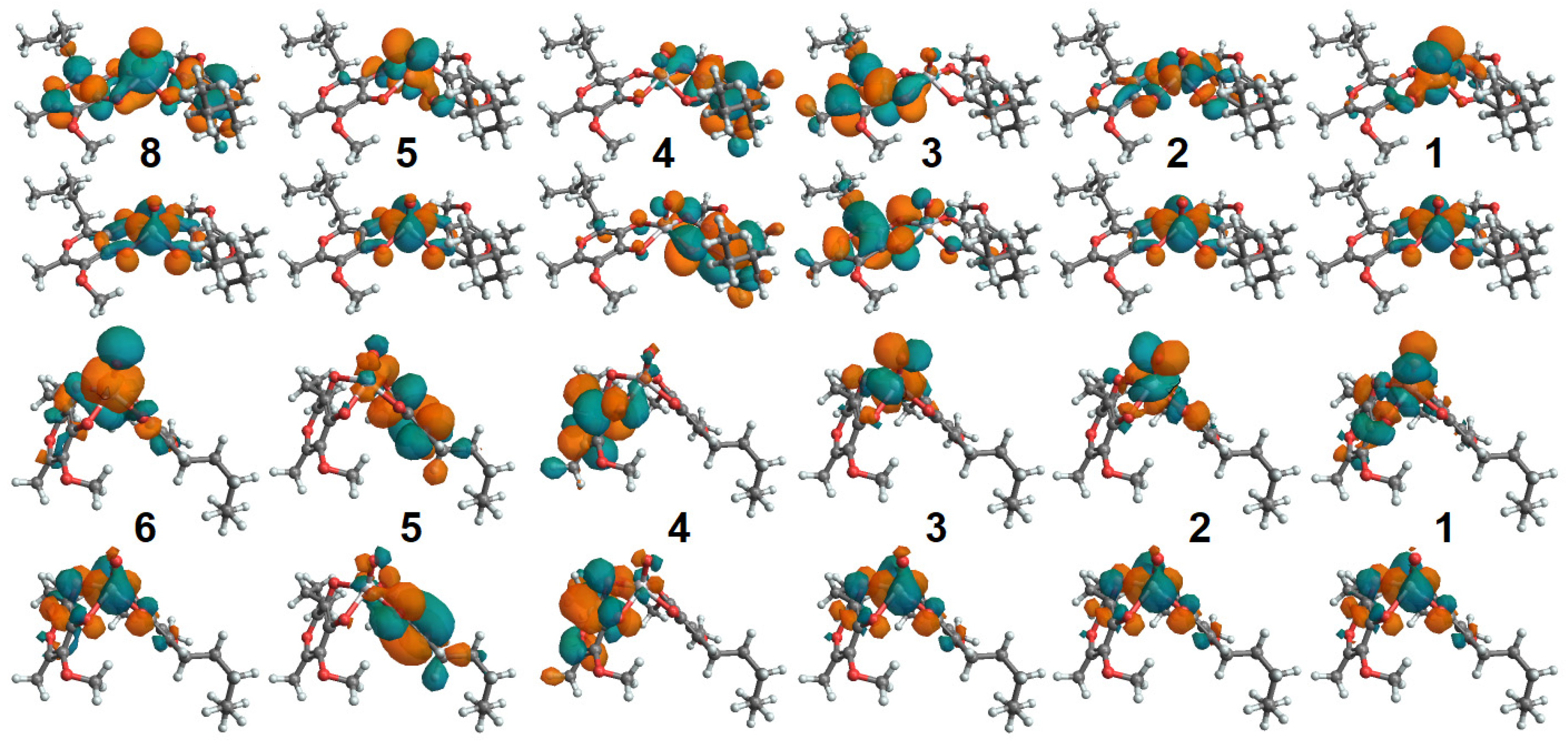

Nature of Coordination Bonds

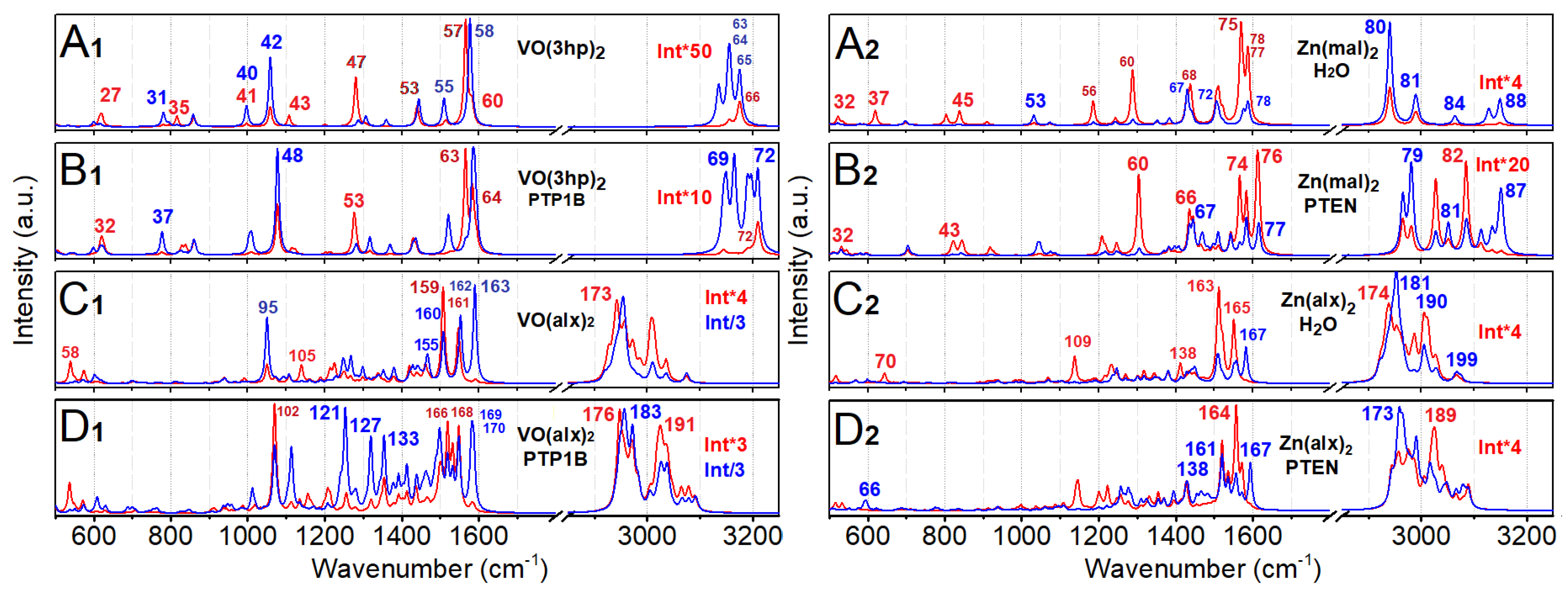

Normal Modes Analysis, VO(3hp)2

Normal Modes Analysis, Zn(mal)2

Normal Modes Analysis: VO(alx)2

Normal Modes Analysis: Zn(alx)2

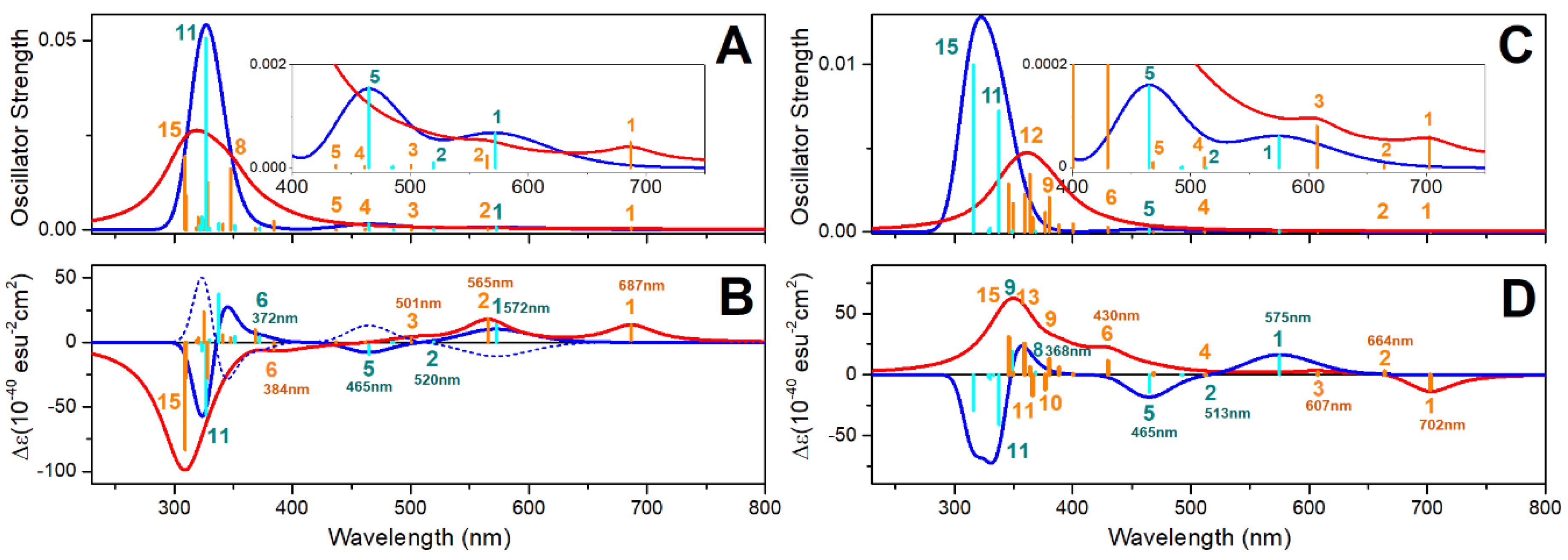

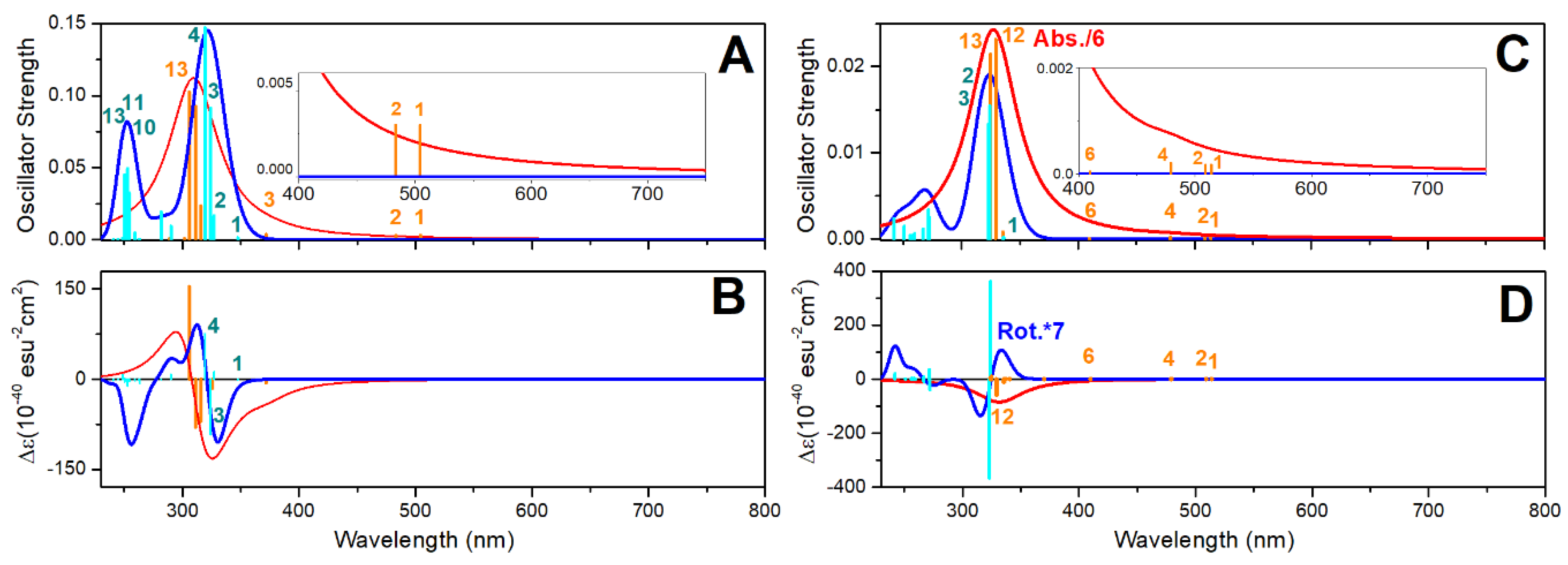

Oxovanadium Systems UV-VIS Properties

Zinc Systems UV-VIS Properties

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Rosenberg, B.; VanCamp, L.; Trosko, J.E.; Mansour, V.H. Platinum compounds: a new class of potent antitumour agents. Nature 1969, 222, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpin, K.J.; Dyson, P.J. Enzyme inhibition by metal complexes: concepts, strategies and applications. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. American Diabetes Association, Diabetes Care 2006, 29, S43–S48.

- Lyonnet, B.; Martz, X.; Martin, E. L’emploi therapeutique des derives du. vanadium. La Presse Med. 1899, 1, 191–192. [Google Scholar]

- Meeks, M.J.; Landolt, R.R.; Kessler, W.V.; Born, G.S. Effect of vanadium on metabolism of glucose in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 1971, 60, 482–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLauchlan, C.C.; Hooker, J.D.; Jones, M.A.; Dymon, Z.; Backhus, E.A.; Greiner, B.A.; Dorner, N.A.; Youkhana, M.A.; Manus, L.M. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2010, 104, 274-281.

- Rehder, D. The potentiality of vanadium in medicinal applications. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 1823–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.H.; Liboiron, B.D.; Sun, Y.; Bellman, K.D.D.; Setyawati, I.A.; Patrick, B.O.; Karunaratne, V.; Rawji, G.; Wheeler, J.; Sutton, K.; et al. Preparation and characterization of vanadyl complexes with bidentate maltol-type ligands; in vivo comparisons of anti-diabetic therapeutic potential. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 8, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, H.; Fujii, K.; Watanabe, H.; Tamura, H. Orally active and long-term acting insulin-mimetic vanadyl complex: Bis(picolinato)oxovanadium(IV). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 214, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulston, L.; Dandona, P. Insulin-like effect of zinc on adipocytes. Diabetes 1980, 29, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shisheva, A.; Gefel, D.; Schechter, Y. Insulin-like effects of zinc ion in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes 1992, 41, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.D.; Liou, S.J.; Lin, P.Y.; Yang, V.C.; Alexander, P.S.; Lin, W.H. Effects of zinc supplementation on the plasma glucose level and insulin activity in genetically obese (ob/ob) mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1998, 61, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, J.M.; Contoreggi, C.S. The mechanism of the insulinlike effects of ionic zinc. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 4362–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezaki, O. IIb group metal ions (Zn2+, Cd2+, Hg2+) stimulate glucose transport activity by post-insulin receptor kinase mechanism in rat adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 16118–16122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilouz, R.; Kaidanovich, O.; Gurwitz, D.; Eldar-Finkelman, H. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3b by bivalent zinc ions: insight into the insulin-mimetic action of zinc. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 295, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, H.; Adachi, Y. The pharmacology of the insulinomimetic effect of zinc complexes. Bio. Metals 2005, 18, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Silbajoris, R.A.; Whang, Y.E.; Graves, L.M.; Bromberg, P.A.; Samet, J.M. p38 and EGF receptor kinase-mediated activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway is required for Zn2+-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005, 289, L883–L889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuki, W.; Hiromura, M.; Sakurai, H. J. Inorg. Insulinomimetic Zn complex (Zn(opt)2) enhances insulin signaling pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem. 2007, 101, 692–699. [Google Scholar]

- Gundhla, I.Z.; Ugirinema, V.; Walmsley, R.S.; Mnonopi, N.O.; Hosten, E.; Betz, R.; Frost, C.L.; Tshentu, Z.R. pH-metric chemical speciation modeling and in vitro anti-diabetic studies of bis[(imidazolyl)carboxylato]oxovanadium(IV) complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 145, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, D.; Ugone, V.; Serra, M.; Garribba, E. Speciation of potential anti-diabetic vanadium complexes in real serum samples. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 173, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.L.; Duhme, A.K.; Hider, R.C.; Hossain, M.B.; Rizvi, S.; van der Helm, D. Synthesis, physicochemical properties, and biological evaluation of hydroxypyranones and hydroxypyridinones: novel bidentate ligands for cell-labeling. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 3659–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiromura, M.; Adachi, Y.; Machida, M.; Hattori, M.; Sakurai, H. Glucose lowering activity by oral administration of bis(allixinato)oxidovanadium(iv) complex in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice and gene expression profiling in their skeletal muscles. Metallomics 2009, 1, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Lu, L.; Gao, X.; Wu, Y.; Guo, M.; Li, Y.; Fu, X.; Zhu, M. Ternary Oxovanadium(IV) Complexes of ONO-Donor Schiff Base and Polypyridyl Derivatives as Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Inhibitors: Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Activities. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 14, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Reed, W.; Samet, J.M.; Whang, Y.E.; Ghio, A.J. Zinc-induced PTEN Protein Degradation through the Proteasome Pathway in Human Airway Epithelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 28258–28263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, D.F.; Saltiel, A.R. Lipid phosphatases as drug discovery targets for type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, H.; Katoh, A.; Kiss, T.; Jakusch, T.; Hattori, M. Metallo–allixinate complexes with anti-diabetic and anti-metabolic syndrome activities. Metallomics 2010, 2, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwaser, I.; Qian, S.; Gershonov, E.; Fridkin, M.; Schechter, Y. Organic vanadium chelators potentiate vanadium-evoked glucose metabolism in vitro and in vivo: establishing criteria for optimal chelators. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000, 58, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabe, K.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Yasui, H.; Sakurai, H. Possible mode of action for insulinomimetic activity of vanadyl(IV) compounds in adipocytes. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 2860–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, H.; Katoh, A.; Yoshikawa, Y. Chemistry and biochemistry of insulin-mimetic vanadium and zinc complexes. Trial for treatment of diabetes mellitus. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 79, 1645–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiromura, M.; Nakayama, A.; Adachi, Y.; Doi, M.; Sakurai, H. Action mechanism of bis(allixinato)oxovanadium(IV) as a novel potent insulin-mimetic complex: regulation of GLUT4 translocation and FoxO1 transcription factor. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 12, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, A.; Hiromura, M.; Adachi, Y.; Sakurai, H. Molecular mechanism of antidiabetic zinc-allixin complexes: regulations of glucose utilization and lipid metabolism. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 13, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, F.; Perfetto, L.; Castagnoli, L.; Cesareni, G. The human phosphatase interactome: An intricate family portrait. FEBS Letters 2012, 586, 2732–2739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lessard, L.; Stuible, M.; Tremblay, M.L. The Two Faces of PTP1B in Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bononi, A.; Agnoletto, C.; De Marchi, E.; Marchi, S.; Patergnani, S.; Bonora, M.; Giorgi, C.; Missiroli, S.; Poletti, F.; Rimessi, A.; Pinton, P. Protein Kinases and Phosphatases in the Control of Cell Fate. Enzym. Res. 2011, 2011, 329098. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaganesh, V.; Sivaganesh, V.; Scanlon, C.; Iskander, A.; Maher, S.; Lê, T.; Peethambaran, B. Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases: Mechanisms in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Li, P.M.; Meyerovitch, J.; Goldstein, B.J. Osmotic loading of neutralizing antibodies demonstrates a role for protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in negative regulation of the insulin action pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 20503–20508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmann, C.; Barr, K.J.; Kung, J.; Zhu, J.; Erlanson, D.A.; Shen, W.; Fahr, B.J.; Zhong, M.; Taylor, L.; Randal, M.; McDowell, R.S.; Hansen, S.K. Allosteric inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004, 11, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, S.; Fantus, I.G. Inhibition of the Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase PTP1B: Potential Therapy for Obesity, Insulin Resistance and Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Best Prac. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 21, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriou, P.; Geronikaki, A.; Petrou, A. PTP1b Inhibition, A Promising Approach for the Treatment of Diabetes Type II. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 246–263. [Google Scholar]

- Villamar-Cruz, O.; Loza-Mejía, M.A.; Arias-Romero, L.E.; Camacho-Arroyo, I. Recent advances in PTP1B signalling in metabolism and cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20211994. [Google Scholar]

- Barford, D.; Flint, A.J.; Tonks, N.K. Crystal structure of human protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Science 1994, 263, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Z.; Barford, D.; Flint, A.J.; Tonks, N.K. Structural basis for phosphotyrosine peptide recognition by protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Science 1995, 268, 1754–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamerlin, S.C.; Rucker, R.; Boresch, S. A targeted molecular dynamics study of WPD loop movement in PTP1B. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 345, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandao, T.A.; Hengge, A.C.; Johnson, S.J. Insights into the reaction of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B: Crystal structures for transition state analogs of both catalytic steps. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 21, 15874–15883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Xie, L.; Yang, F.; Wang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Xiang, M.; Zhou, S.; Lv, W.; Jia, Y.; Pokhrel, L.; et al. Recent advance on PTP1B inhibitors and their biomedical applications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 199, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, G.; Gallup, N.M.; Alexandrova, A.N.; Hengge, A.C.; Johnson, S.J. Conservative Tryptophan Mutants of the Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase YopH Exhibit Impaired WPD-Loop Function and Crystallize with Divanadate Esters in Their Active Sites. Biochem. 2015, 54, 6490–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; et al. Insights into the importance of WPD-loop sequence for activity and structure in protein tyrosine phosphatases. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 13524–13540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Di Cristofano, A.; Woo, M. Metabolic Role of PTEN in Insulin Signaling and Resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020, 10, a036137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, G.R.; Williams, R.L. Structural Mechanisms of PTEN Regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020, 10, a036152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.O.; Yang, H.; Georgescu, M.M.; Di Cristofano, A.; Maehama, T.; Shi, Y.; Dixon, J.E.; Pandolfi, P.; Pavletich, N.P. Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association. Cell 1999, 99, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mighell, T.L.; Evans-Dutson, S.; O’Roak, B.J. A saturation mutagenesis approach to understanding PTEN lipid phosphatase activity and genotype-phenotype relationships. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrzewa, T.; Jonczyk, J.; Drzezdzon, J.; Jacewicz, D.; Górska-Ponikowska, M.; Kołaczkowski, M.; Kuban-Jankowska, A. Synthesis, In Vitro, and Computational Studies of PTP1B Phosphatase Inhibitors Based on Oxovanadium(IV) and Dioxovanadium(V) Complexes. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvaiz, N.; Abro, A.; Azam, S.S. Three-state dynamics of zinc(II) complexes yielding significant antidiabetic targets. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2024, 127, 108665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühne, T.D.; Iannuzzi, M.; Del Ben, M.; Rybkin, V.V.; Seewald, P.; Stein, F.; Laino, T.; Khaliullin, R.Z.; Schütt, O.; Schiffmann, F.; et al. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package-Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 194103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Ruzsinszky, A.; Csonka, G.I.; Vydrov, O.A.; Scuseria, G.E.; Constantin, L.A.; Zhou, X.; Burke, K. Restoring the Density-Gradient Expansion for Exchange in Solids and Surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 136406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandeVondele, J.; Hutter, J. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 125, 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedecker, S.; Teter, M.; Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosé, S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T.H.; Hay, P.J. Modern Theoretical Chemistry. Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1977, Volume 3, pp. 1-28.

- Wedig, U.; Dolg, M.; Stoll, H.; Preuss, H. Quantum Chemistry: The Challenge of Transition Metals and Coordination Chemistry. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986, pp. 79–89.

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09 Revision E.01. Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009.

- Glendening, E.D., Reed, A.E., Carpenter, J.E. and Weinhold, F. NBO Version 3.1. Gaussian Inc., Pittsburgh, 2003.

- Volkov, C.C.; Chelli, R.; Perry, C.C. Cu(Proline)2 Complex: A Model of Bio-Copper Structural Ambivalence. Molecules 2022, 27, 5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopmans, T. Über die Zuordnung von Wellenfunktionen und Eigenwerten zu den einzelnen Elektronen eines Atoms. Physica 1934, 1, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, A.T.; Hall, G.G. Single determinant wave functions. Proc. Royal. Soc. A 1961, 263, 483–493. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.L. Natural transition orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 4775–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.U.; Hahne, G.; Hanske, J.; Bange, T.; Bier, D.; Rademacher, C.; Hennig, S.; Grossmann, T.N. Redox Modulation of PTEN Phosphatase Activity by Hydrogen Peroxide and Bisperoxidovanadium Complexes. Angew. Chem. 2015, 54, 13796–13800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Szczepankiewicz, B.G.; Pei, Z.; Janowich, D.A.; Xin, Z.; Hadjuk, P.J.; Abad-Zapatero, C.; Liang, H.; Hutchins, C.W.; Fesik, S.W.; Ballaron, S.J.; Stashko, M.A.; Lubben, T.; Mika, A.K.; Zinker, B.A.; Trevillyan, J.M.; Jirousek, M.R. Discovery and Structure-Activity Relationship of Oxalylarylaminobenzoic Acids as Inhibitors of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 2093–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.C.; et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 044130. [Google Scholar]

- Tautz, L.; Critton, D.A.; Grotegut, S. Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases: Structure, Function, and Implication in Human Disease. Phosphatase Modul. 2013, 1053, 179–221. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.P.; et al. Structure-based optimization of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors: from the active site to the second phosphotyrosine binding site. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 4681–4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, A. Effect of protonation states of catalytically important residus and active site water molecules on PTP1B conformation. Diploma, 2008.

- Özcan, A.; Olmez, E.O.; Alakent, B. Effects of protonation state of Asp181 and position of active site water molecules on the conformation of PTP1B. Proteins 2013, 81, 788–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gapsys, V.; Perez-Benito, L.; Aldeghi, M.; Seeliger, D.; van Vlijmen, H.; Tresadern, G.; de Groot, B. L. Large scale relative protein ligand binding affinities using non-equilibrium alchemy. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapprich, S.; Komáromi, I.; Byun, K.S.; Morokuma, K.; Frisch, M.J. A New ONIOM Implementation in Gaussian 98. 1. The Calculation of Energies, Gradients and Vibrational Frequencies and Electric Field Derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem) 1999, 462, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.J.; Kollman, P.A.; Case, D.A.; Singh, U.C.; Ghio, C.; Alagona, G.; Profeta, S.; Weiner, P. A new force field for molecular mechanical simulation of nucleic acids and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zborowski, K.; Grybos, R.; Proniewicz, L.M. Structure modification of maltol (3-hydroxy-2-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one) upon cation and anion formation studied by vibrational spectroscopy and quantum-mechanical calculations. Vib. Spec. 2007, 43, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajón-Costa, B.S.; Baran, E.J. Vibrational spectra of bis(maltolato)zinc(II), an interesting insulin mimetic agent. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. and Biomol. Spec. 2013, 113, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stappen, C.; Maganas, D.; DeBeer, S.; Bill, E.; Neese, F. Investigations of the Magnetic and Spectroscopic Properties of V(III) and V(IV) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57(11), 6421–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirohata, A.; Takanashi, K. Future perspectives for spintronic devices. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 193001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Chinnasamy, H.V.; Sahu, D.; Matheshwaran, S.; Sow, C.; Chandra Mondal, P. Spin-dependent electrified protein interfaces for probing the CISS effect. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 159, 024708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feder, D.; Gahan, L.R.; McGeary, R.P.; Guddat, L.W.; Schenk, G. The binding mode of an ADP analog to a metallohydrolase mimics the likely transition state. Chembiochem. 2019, 20, 1536–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethe, H. Termaufspaltung in Kristallen. Annalen der Physik 1929, 395, 133–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.S.; Green, P.T. Ligand Field Theory for Pentacoordinate Molecules. II. A Crystal Field—Spin-Orbit Coupling Treatment of the d1, d3, d6, and d8 Configurations in Trigonal-Bipyramidal Molecules and the Magnetic Properties of E Ground Terms. Inorganic Chemistry 1969, 8, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| bond | Length Å | ESP charges | oxygen contribution | metal contribution |

| hp: V-Ocrbn | 2.05 | -0.5985, -0.5997 | 88.27% s(23.53%) p3.25(76.42%) | 11.73% s(19.76%) p0.96(18.91%) d3.10(61.33%) |

| hp: V-Ocrbx | 1.97 | -0.5478, -0.5493 | 87.66% s(26.00%) p2.84(73.95%) | 12.34% s(21.40%) p1.39(29.77%) d2.28(48.83%) |

| hp: V=O | 1.5790 | V: 1.4057 O: -0.5655 |

71.49% s(18.16%) p4.50(81.74%) | 28.51% s(13.17%) p0.00( 0.04%) d6.59(86.79%) |

| 77.11% p1.00(99.86%) | 22.89% p1.00(32.16%) d2.11(67.84%) | |||

| P-hp: V-Ocrbn | 2.04, 207 | -0.5923, -0.5681 | 88.10% s(23.74%) p3.21(76.21%) | 11.90% s(18.66%) p1.40(26.49%) d2.79(54.14%) |

| P-hp: V-Ocrbx | 1.97, 1.96 | -0.5183, -0.5494 | 86.12% s(25.27%) p2.95(74.68%) | 13.88% s(20.64%) p1.25(25.81%) d2.59(53.55%) |

| P-hp: V=O | 1.57968 | V: 1.292 Oa: -0.6463 |

72.92% s(21.05%) p3.75(78.88%) | 27.08% s(18.98%) p0.01(0.23%) d4.26(80.78%) |

| 77.49% p1.00 (99.85%) | 22.51% p1.00 (30.53%) d2.10(69.39%) | |||

| bond | Length Å | ESP charges | oxygen contribution | metal contribution |

| mal: Zn-Ocrbn | 2.07 | -0.72; -0.74 Zn: 1.441 |

95.62% s(14.83%) p5.74(85.10%) | 4.38% s(22.66%) p3.39(76.73%) d0.03(0.62%) |

| mal: Zn-Ocrbx | 1.99 | 94.81% s(16.71%) p4.98(83.23%) | 5.19% s(27.22%) p2.65(72.08%) d0.03(0.70%) | |

| mal: Zn-O7crbn | 2.10 | O7;18: -0.71; -0.65 O9;11: -0.57;-0.67 Zn: 1.25 Oa: -0.81 |

96.18% s(15.58%) p5.41(84.36%) | 3.82% s(20.82%) p3.14(65.29%) d0.67(13.89%) |

| mal: Zn-O18crbn | 2.08 | 95.97% s(16.29%) p5.13(83.65%) | 4.03% s(22.66%) p2.88(65.30%) d0.53(12.04%) | |

| mal: Zn-O9crbx | 2.03 | 96.03% s(17.82%) p4.61(82.13%) | 3.97% s(23.36%) p2.13(49.82%) d1.15(26.81%) | |

| mal: Zn-O11crbx | 2.08 | 96.67% s(16.97%) p4.89(82.98%) | 3.33% s(19.41%) p2.67(51.81%) d1.48(28.78%) | |

| mal: Zn-Oa | 2.23 | 97.64% s(30.23%) p2.31(69.72%) | 2.36% s(13.77%) p4.97(68.48%) d1.29(17.75%) | |

| P-mal:Zn-O7crbn | 2.02121 | O7;O16:-0.69;-0.82 O9; O23:-0.67;-0.64 Zn 1.34 |

95.62% s(14.05%) p6.11(85.88%) | 4.38% s(25.69%) p2.83(72.61%) d0.07(1.70%) |

| P-mal:Zn-O16crbn | 2.24524 | 97.40% s(8.40%) p10.90(91.53%) | 2.60% s(14.56%) p5.72(83.32%) d0.15(2.12%) | |

| P-mal:Zn-O9crbx | 2.05197 | 96.16% s(12.15%) p7.22(87.79%) | 3.84% s(25.85%) p2.79(72.08%) d0.08(2.06%) | |

| P-mal:Zn-O23crbx | 1.94144 | 95.21% s(14.87%) p5.72(85.06%) | 4.79% s(33.55%) p1.92(64.55%) d0.06(1.90%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).