1. Introduction

Adolescence is considered to be a period of development ranging between 10 and 19 years old. Adolescence is one of the most rapid and formative stages of human development; national development policies, programs, and plans must pay particular attention to the unique physical, cognitive, social, emotional, and sexual development during this period.[

1,

2] The World Health Organization defines lifestyles as “identifiable behavioural patterns, determined by the interaction between individual personal characteristics, social interactions, and socioeconomic and environmental living conditions.[

3] Lifestyle choices and individuals’ behaviours have the potential to influence health and improve the quality of life.[

4] There is growing evidence of the detrimental effects of lifestyle characteristics like excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, poor eating habits, and low physical activity on an individual’s health.[

5]

With a population of 34 million, Saudi Arabia is the largest country on the Arabian Peninsula. Adolescents between the ages of 10 and 19 comprise 14% of the population.[

6] Today, more than ever, there are 1.3 billion teenagers worldwide, representing 16% of the world's population.[

7] A study done in 2022 in Saudi Arabia reported that many adolescents practice various unhealthy routines and Dietary Behaviors. Only 54.8% were found to consume breakfast per day, 54.3% of teenagers ate fruit or vegetables daily,21.8% reported drinking Soda daily, and 45% of all teenagers didn't do any physical activity or sports. Only 13.7% had to do physical exercises daily for 30 minutes during the week preceding participation in the study, 59% slept less than 8 hours at night per week, 60% had ever smoked cigarettes, and 25% had been bullied at school.[

8] Many teenagers practice a variety of unhealthy routines such as insufficient dietary intake, rest, physical activity, and risky behaviour such as tobacco and drug use and E-secret vape it could result in adverse health effects.[

9] our study aims to evaluate adolescent students' perception of their healthy lifestyle in Bisha.

A healthy lifestyle is essential for adolescents and their environment and helps them improve their lifestyle. Pay particular attention to the unique physical, cognitive, social, emotional, and sexual development during this period. Many teenagers practice a variety of unhealthy routines, such as insufficient dietary intake, rest, and physical activity. Risky behaviour, such as tobacco and drug use and E-cigarette vaping, could result in adverse health effects. Many studies have been conducted on this topic, but there are not enough studies in Bisha.

The study about The Attitude to One's Own Health Among Native Residents of Yakutia in 2017 was carried out concerning value reference points and attitudes of the native population of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) intended for health preservation. About 292 respondents residing in rural areas of Yakutia, most of them misunderstand and underestimate health's role in their lives because they are unaware of health as an instrumental value.[

10] In a study about the awareness and attitude of adolescents concerning healthy lifestyles in 2022 done on 183 teenagers aged 15-17 years studying in secondary schools, It is established that most adolescents are aware of healthy lifestyles.[

11] A study was conducted in 2018 about Public Awareness towards Healthy Lifestyle; they found that participants were generally aware of what they consume, they value the importance of having breakfast, controlling their food portion size, and eating three meals per day.[

12] A study about Attitudes of Jordanian adolescent students toward overweight and obesity. In 2018, the students expressed positive attitudes toward lifestyle, which means their attitudes were consistent with healthy behaviour. However, boys had significantly more positive attitudes than girls (p=0.04). The prevalence of overweight and obesity was 23.8%, while obese and non-obese students had similar attitudes toward lifestyle and obesity.[

13,

14] A study about Knowledge of healthy diets among adolescents in eastern Saudi Arabia. In 2005, it was reported that knowledge of healthy diets among school students was inadequate. It is recommended that health education and information about healthy eating habits and lifestyles be included in school curricula.[

15]

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was designed as an analytical cross-sectional study aimed at assessing adolescent awareness and perceptions of a healthy lifestyle in Bisha, Asir Province, Saudi Arabia. The cross-sectional design was chosen to capture a snapshot of the current level of knowledge and awareness among school-going adolescents within a defined period. This design allows for the identification of associations between sociodemographic factors and health awareness levels without requiring long-term follow-up.

Study Setting

The study was conducted in Bisha City, which is located in Asir Province, Saudi Arabia. Bisha has a substantial adolescent student population attending both intermediate and high schools. According to the most recent data from the Ministry of Education branch in Bisha, there are 27 intermediate schools with a total enrollment of 3,478 male students and 15 high schools with 3,676 male students, making a combined total of 7,154 students. Given the relevance of this population for public health interventions, this setting was ideal for investigating adolescent awareness of healthy lifestyle practices.

Study Population and Sampling Criteria

The study targeted male students aged 13–19 years enrolled in intermediate and high schools in Bisha. These students represented an appropriate demographic to assess adolescent awareness of health-related behaviors. The inclusion criteria required participants to be within the specified age range, enrolled in the selected schools, and have both parental consent and personal assent to participate in the study.

Students who were older than 19 years, had special educational needs or intellectual disabilities, or whose parents or guardians declined consent were excluded from participation. Female students were not included in the study due to logistical constraints and challenges in accessing female schools within the study timeframe. This exclusion was necessary to maintain feasibility, given the gender-segregated education system in Saudi Arabia.

Sample Size Determination

The minimum required sample size was calculated using Raosoft software, an online sample size calculator. The calculation was based on a 95% confidence level, a 5% margin of error, and an expected response distribution of 50%, ensuring a representative sample of the target population. Based on these parameters, the required minimum sample size was 365 students. However, to enhance the study’s statistical power and account for potential non-responses or incomplete questionnaires, the final sample included 464 students.

Sampling Technique

To ensure fair representation, a multistage stratified cluster sampling technique was employed. Initially, schools were stratified into two categories based on education level—intermediate and high schools. Following this, schools were grouped by geographical distribution (North and South Bisha), ensuring diverse representation. A random selection of schools from each geographical cluster was then performed.

Once schools were selected, a simple random sampling method was used to choose students from the school’s official student lists. This approach ensured that each student had an equal chance of being selected, reducing potential selection bias and improving the study’s generalizability.

Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected using a structured, self-administered questionnaire, which was developed to assess students' awareness and perceptions of a healthy lifestyle. The questionnaire underwent content validation by public health experts to ensure clarity, relevance, and appropriateness for the target population. It was then piloted among 30 students (excluded from the final analysis) to test for comprehension, reliability, and response consistency.

The questionnaire was composed of three key sections. The first section covered demographic variables, including age, educational level, parental education, and household income. The second section evaluated awareness of healthy lifestyle behaviors, focusing on diet, physical activity, and substance use. The final section assessed self-reported lifestyle practices, such as breakfast consumption, fruit and vegetable intake, and participation in sports or exercise. The questionnaire consisted of 11 core questions, with students’ awareness levels classified as follows:

Good Awareness: A score of 7 or more correct answers

Moderate Awareness: A score between 4 and 6 correct answers

Poor Awareness: A score of 3 or fewer correct answers

Data Quality Control Measures

To ensure data reliability and validity, multiple quality control measures were implemented. The pilot study helped refine ambiguous questions and improve clarity. Additionally, trained data collectors were available to assist students in understanding the questionnaire if needed, while ensuring responses remained unbiased. Random checks were conducted to verify the completeness and accuracy of responses, and data entry was double-checked to minimize errors.

Statistical Analysis

All data were entered and analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize categorical and continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables, while means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables.

To assess associations between students' awareness levels and sociodemographic factors, Chi-square tests (χ²) were used for categorical data. Independent t-tests or one-way ANOVA were applied for continuous variables when necessary. Additionally, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine independent predictors of health awareness. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, ensuring rigorous statistical interpretation of findings.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Bisha College of Medicine (UBCOM). Ethical approval ensured that the study adhered to national and institutional research standards.

Informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians before data collection, and student assent was sought to confirm voluntary participation. Participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, with all collected data being used exclusively for research purposes. Any student who wished to withdraw from the study at any time was allowed to do so without any consequences.

Limitations and Bias Mitigation

Several limitations were identified in this study. The exclusion of female students may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader adolescent population in Bisha. Future studies should consider including female participants to provide a more comprehensive perspective. Additionally, as data were collected using self-reported questionnaires, there was a potential for response bias, particularly social desirability bias, where students may have provided answers they perceived as favorable rather than accurate reflections of their behaviors.

To mitigate these biases, anonymous data collection was emphasized to encourage honest responses. Additionally, a pilot study helped refine question wording to reduce misinterpretations. The cross-sectional study design also posed a limitation, as it only provided a snapshot of awareness levels at a single point in time. Longitudinal studies would be beneficial to track changes in health awareness over time and evaluate the impact of potential interventions.

Strengths of the Study

Despite its limitations, this study has several strengths. It is the first study in Bisha to comprehensively evaluate adolescent awareness of a healthy lifestyle, providing essential baseline data for future research and health promotion initiatives. The use of a large sample size (464 students) ensures statistical power and enhances the representativeness of the findings. Additionally, the validated questionnaire and rigorous sampling strategy contribute to the reliability of the study outcomes.

This study highlights the importance of targeting adolescent health awareness through educational interventions and parental engagement. By identifying key sociodemographic determinants of health awareness, the findings can inform policymakers and educators in designing effective health promotion programs for Saudi Arabian adolescents.

3. Results

According to

Table 1, 464 students participated in the present study, 213 from intermediate school and 251 from high school in Bisha, Saudi Arabia. The mean age of the study participants was 15.40 years, the mean weight was 58.96 kilograms, and the mean height was 163.82 cm.

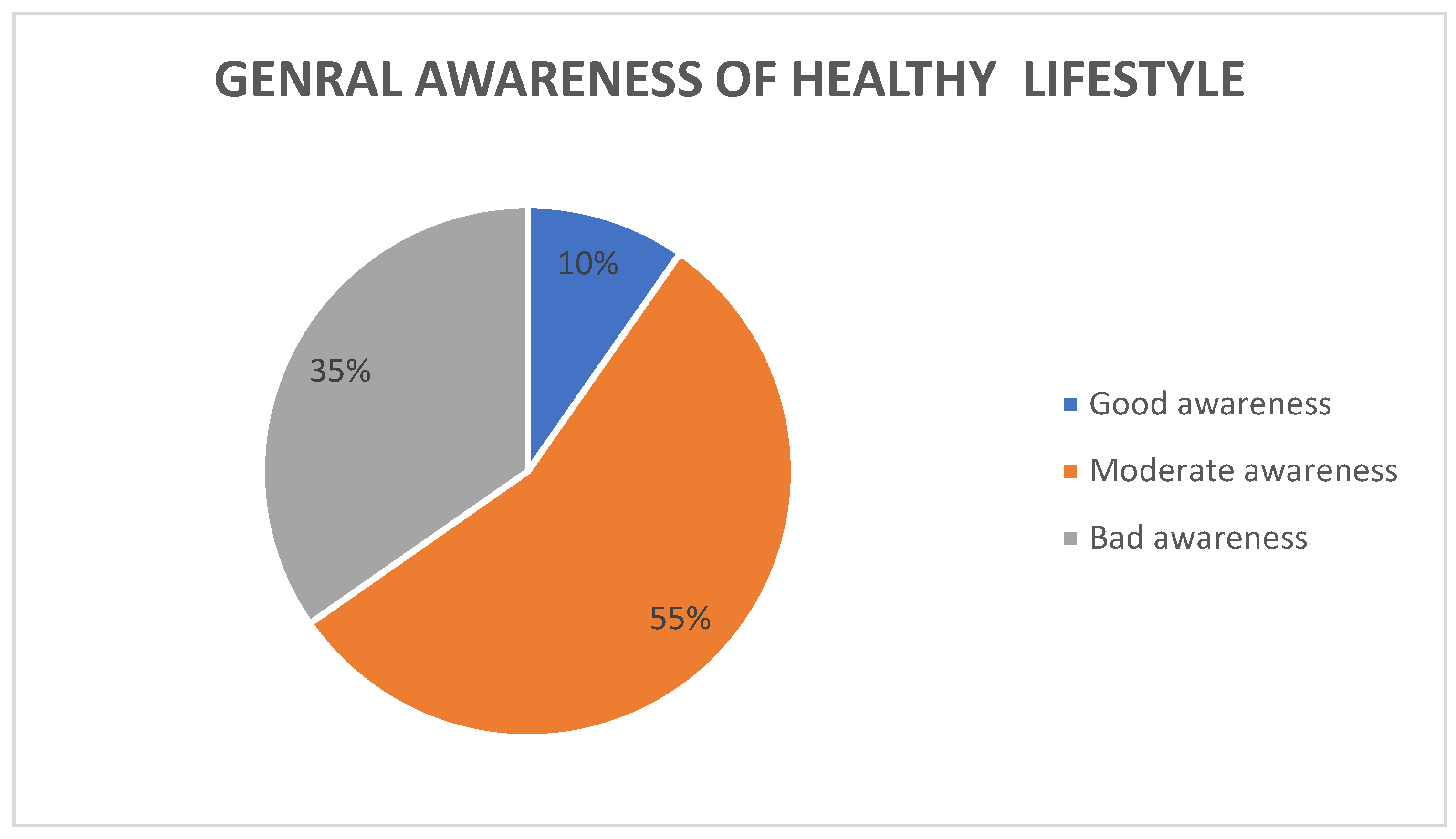

Figure 1 shows General awareness of healthy lifestyles among the study population is shown in Figure 1. Out of the total 464 study population, 45 students (10% approx.) had good awareness, 258 students (55% approx.) had moderate awareness, and 161 students (35% approx.) had insufficient awareness about healthy lifestyles.

Figure 1A.

General awareness of healthy lifestyle

Figure 1A.

General awareness of healthy lifestyle

Table 2.

Association between socio-demographic factors with general awareness.

Table 2.

Association between socio-demographic factors with general awareness.

| Category |

Observation |

| Study Population |

Total: 464 students |

| School Levels |

Intermediate: 213 students (46%)High School: 251 students (54%) |

| Mean Age |

15.40 years |

| Mean Weight |

58.96 kilograms |

| Mean Height |

163.82 cm |

| Awareness of Healthy Lifestyles |

Good: 45 students (10%)Moderate: 258 students (55%)Bad: 161 students (35%) |

| Significant Sociodemographic Factors |

Father’s educational level (P = 0.012)Monthly income of the family (P = 0.031) |

| Non-Significant Factors |

Age, weight, height, mother’s educational level |

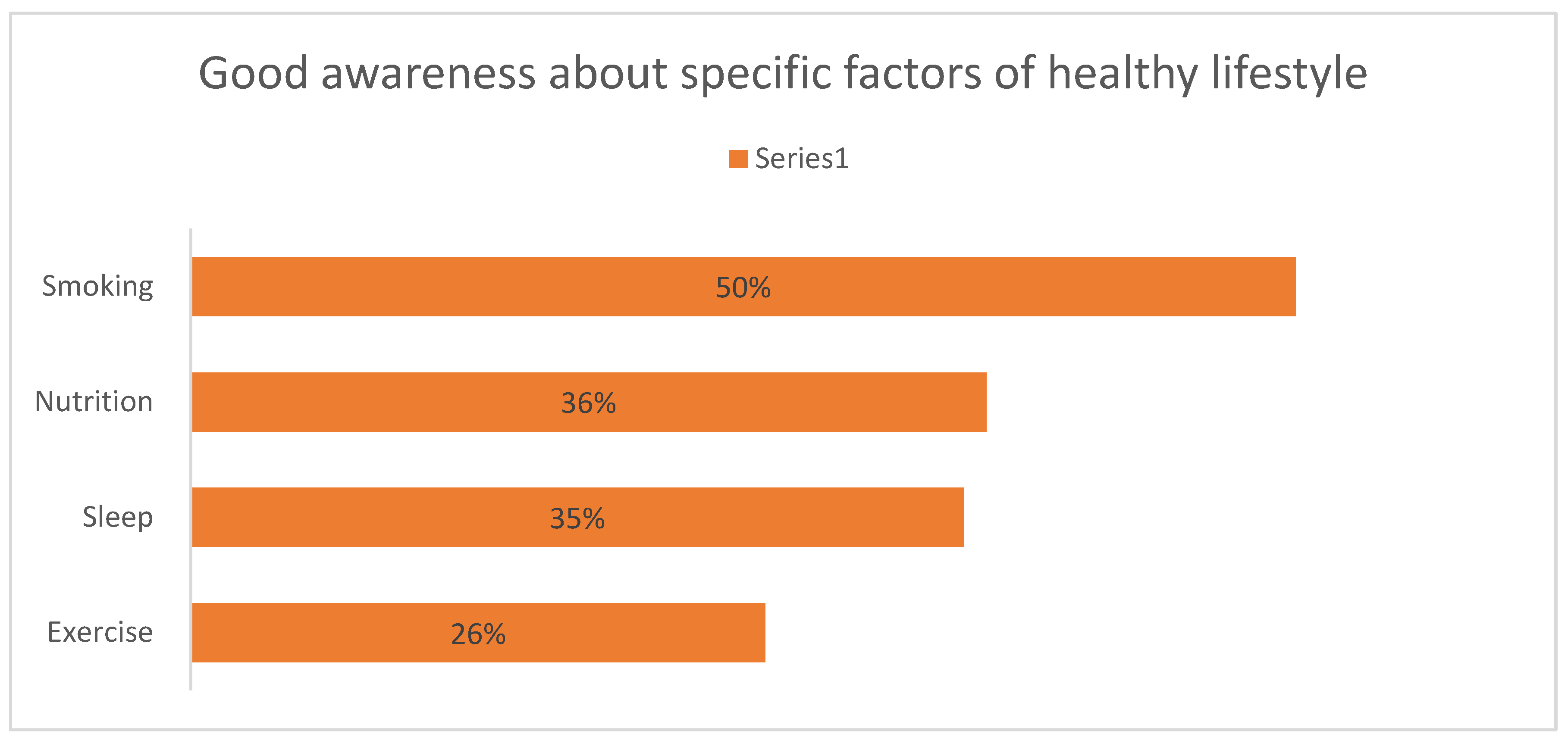

Some of the sociodemographic factors in the present study were found to be significantly associated with general awareness about healthy lifestyles, such as “father’s educational level” (P=0.012) and “monthly income of the family” (P=0.031) as shown in tables (2 & 3 respectively). In contrast, the age, weight, height and mother’s educational level were not significantly associated. Almost 39% of the student participants had good awareness about recommended exercise time, and it’s significantly related to their father’s educational level (P= 0.002); however, 61% had poor awareness. About 88% of students had poor awareness of weight lifting exercises per week, whereas 12% had good awareness.

Figure 1B: 50% of the study population answered smoking-related questions correctly.

Figure 1B.

Good awareness about specific factors of a healthy lifestyle

Figure 1B.

Good awareness about specific factors of a healthy lifestyle

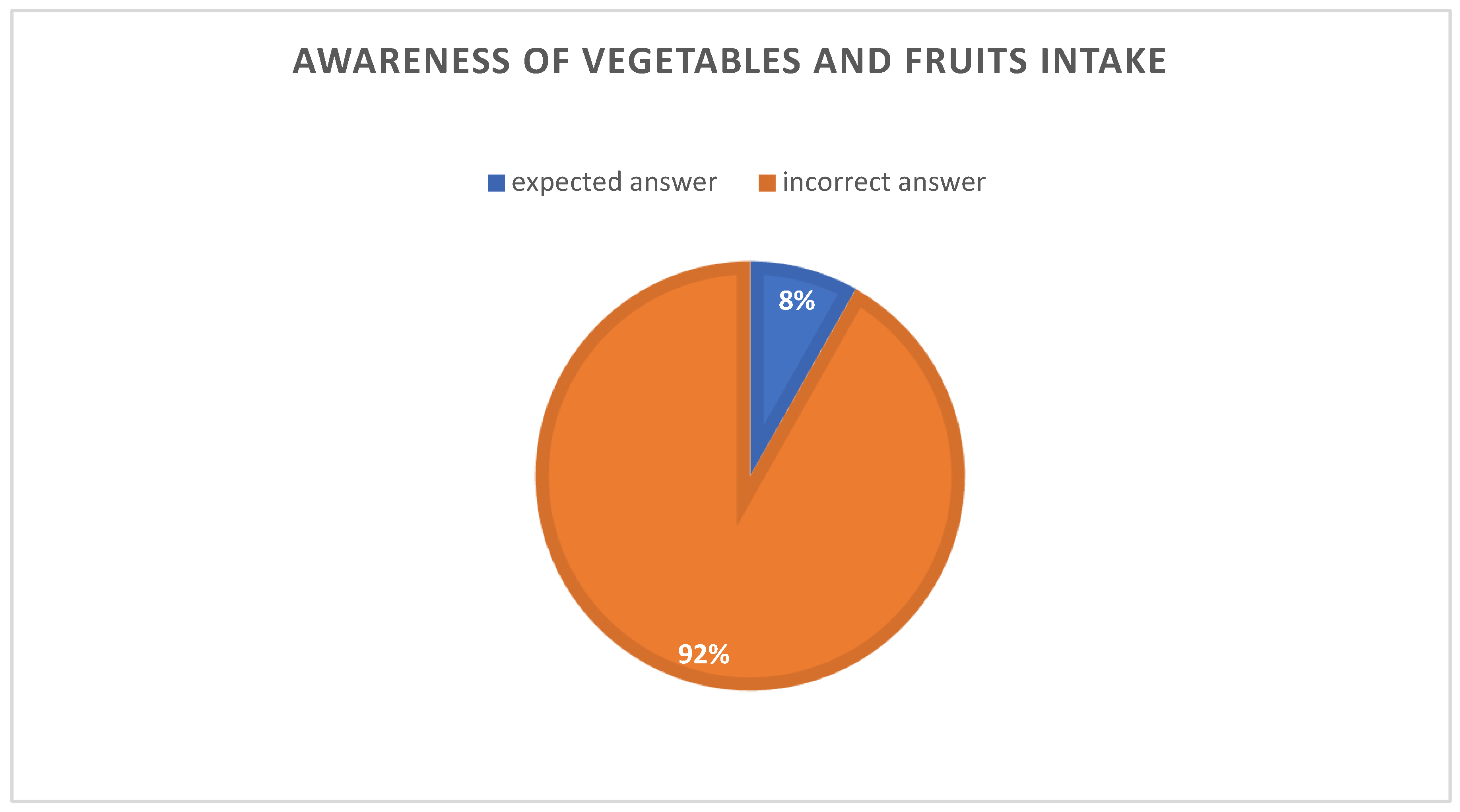

Figure 2: Only 8% of the study population chose the correct recommended vegetable and fruit intake answer.

Figure 2.

Awareness of recommended vegetables and fruits intake.

Figure 2.

Awareness of recommended vegetables and fruits intake.

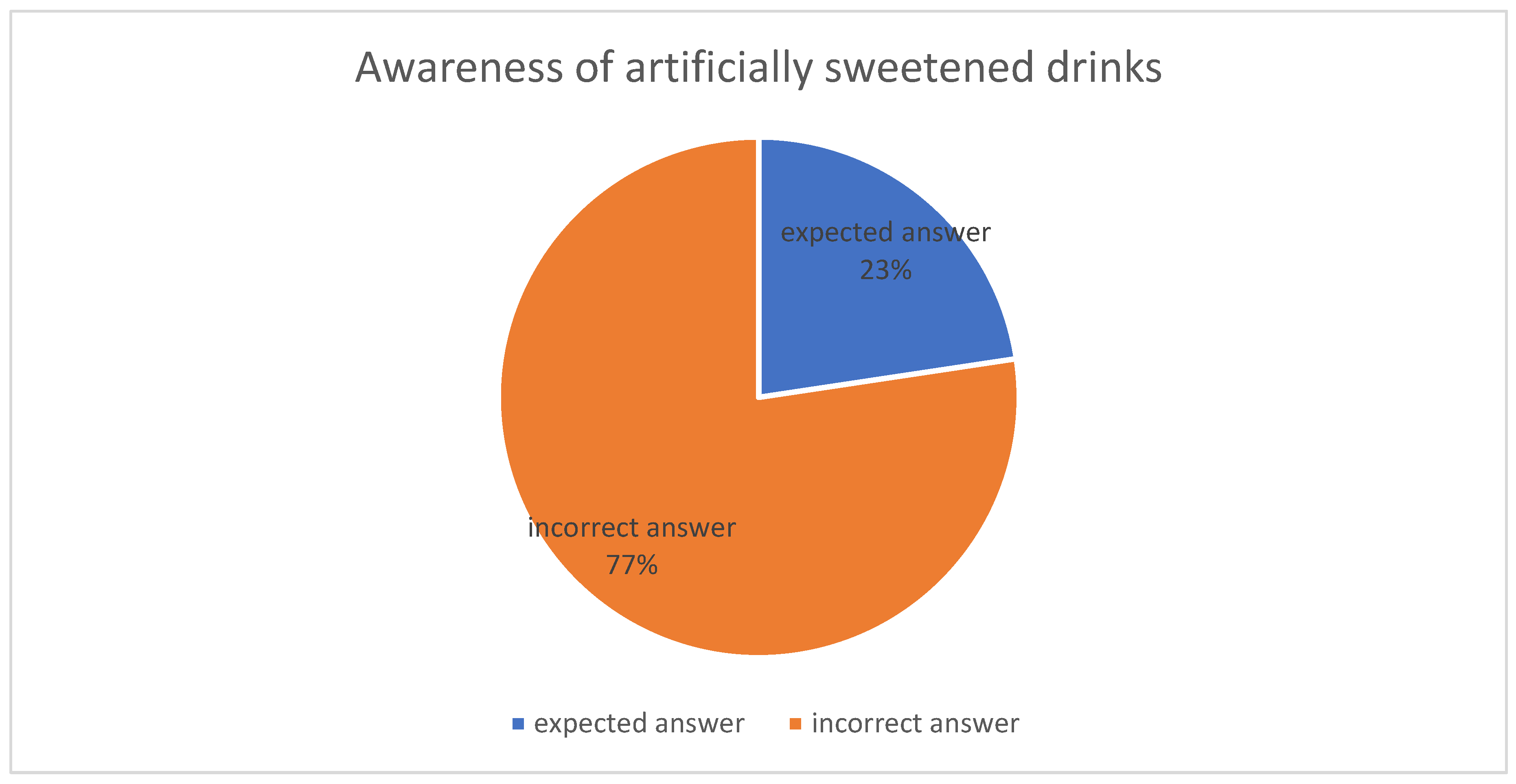

Figure 3: 23% of the study population had a good awareness of artificially sweetened drinks

Figure 3.

Awareness of artificially sweetened drinks.

Figure 3.

Awareness of artificially sweetened drinks.

As per

Table 3, Students from intermediate and high schools exhibited the highest percentages of poor awareness (42% and 41%, respectively). Poor awareness of the participants the students decreased significantly with father higher educational levels (30% in university and 33% in master’s or above). Most participants at all academic levels had moderate awareness (54% to 59%). University-level students had the highest number of participants with moderate awareness (59%). Good awareness of the participants of the students increased with the higher educational attainment of their fathers, with 4% at intermediate and high school levels, 11% at the university level, and 17% among those fathers with master’s or above. Higher fathers’ educational levels were associated with better awareness of the healthy lifestyles of the participants, demonstrating a clear positive correlation. The p-value (0.011) is less than the significance level of 0.05, indicating a statistically significant association between fathers’ educational levels and participants’ awareness levels.

As per

Table 4, the p-value (0.031) is less than the significance level of 0.05, indicating a statistically significant relationship between income levels and awareness levels of healthy lifestyles. Poor awareness is relatively higher among lower-income groups (e.g., " SAR 5000 or less" and " SAR 10001– SAR 15000"). Good awareness improves in higher income brackets, especially among individuals with incomes between " SAR 20001– SAR 25000". Most participants across most income ranges had moderate awareness, dominating each group. The analysis underscores the role of economic status in influencing awareness levels about healthy lifestyles. Interventions targeting health awareness should mainly focus on lower-income groups.

As per

Table 5, The majority (71%) of the study population demonstrated good awareness of the hazards of passive smoking. This awareness showed a statistically significant association with the father’s educational level (P = 0.009), indicating that higher paternal education may contribute to better student awareness. Approximately 60% of students believed that E-cigarettes are a healthier alternative to traditional smoking, reflecting a misconception that needs to be addressed through educational interventions.

4. Discussion

Adolescence is the most sensitive period of life affected by the type of lifestyle, and it's the most rapid and formative stage of human development. The lifestyle choices of adolescents’ influence health and improve the quality of life. Our findings showed a significant association between the general awareness of the students and the "father's educational level" and with the "monthly income of the family", as either of these factors could influence the student's awareness. The family's monthly income affects the adolescents' awareness level because it restricts the learning process.

Our study showed that 35% of the study participants were unaware of healthy lifestyles, and only 10% were aware, comparable to studies conducted in Yakutia in 2017 10. This is contrary to many previous studies [

11,

12] and one similar study conducted in Jordan in 2018 [

13], which also showed contradictory findings.

The participating students had poor knowledge about exercise time (61 %) and weight-lifting exercise (88%), which is not similar to the findings of the study conducted among medical students at King Abdul-Aziz University, Saudi Arabia, in 2015. [

14]

Students had poor knowledge about vegetables and fruit intake (92%); this finding is supported by another study done at King Faisal University, Al-Khobar, Dammam, Saudi Arabia, in the year 200515 and also supported by a similar study done in the United State of America, 201314 However this was in contrary to study conducted in Malaysia 201812 and a similar study done in king Abdul-Aziz university, KSA. [

14]

Adolescence, spanning ages 10 to 19, is a pivotal phase characterized by rapid physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development. During this period, individuals establish patterns that significantly influence their immediate and long-term health outcomes. Healthy behaviors adopted in adolescence, such as balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, and adequate sleep, are foundational for disease prevention and health promotion. Conversely, engagement in risky behaviors, including substance use and sedentary lifestyles, can lead to adverse health effects extending into adulthood. The World Health Organization emphasizes that adolescence is a unique stage for laying the foundations of good health, as decisions made during this time affect how individuals feel, think, and interact with the world around them. [

15]

Parental education and family income are pivotal determinants of adolescents' health behaviors and awareness. Higher parental education often correlates with increased health literacy, fostering environments that promote healthy lifestyle choices among adolescents. Similarly, greater family income provides access to resources that facilitate health-promoting behaviors, such as nutritious foods and recreational activities. Conversely, adolescents from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face elevated risks of engaging in unhealthy behaviors, including early initiation of smoking and low physical activity levels. A systematic review highlighted that children and adolescents with low socioeconomic status are more likely to adopt unhealthy behaviors compared to their higher-status counterparts. Thus, socioeconomic factors play a crucial role in shaping adolescents' health awareness and behaviors. [

16]

Despite the critical importance of health awareness during adolescence, studies indicate that a substantial proportion of adolescents lack adequate knowledge about healthy lifestyles. For instance, research has shown that adolescents often do not engage in positive healthy behaviors, with such behaviors decreasing as age advances. This deficiency in awareness underscores the need for targeted health education programs that address the specific needs and challenges faced by adolescents. [

17]

Physical activity is essential for adolescents' physical and mental well-being. However, many adolescents lack knowledge about recommended exercise guidelines. A study found that adolescents often do not engage in positive healthy behaviors, including regular physical activity, with such behaviors decreasing as age advances. This gap in knowledge can lead to insufficient physical activity, increasing the risk of various health issues. Addressing this knowledge gap is crucial for promoting active lifestyles among adolescents. [18, 21, 22]

Adequate nutrition is vital during adolescence, a period marked by significant growth and development. However, many adolescents lack proper knowledge regarding healthy dietary practices. Johns Hopkins Medicine emphasizes that healthy eating during adolescence is crucial, as body changes during this time affect nutritional and dietary needs. This deficiency in dietary knowledge can lead to poor eating habits, increasing the risk of obesity and related health problems. Implementing comprehensive nutrition education in schools and communities is essential to improve adolescents' dietary habits. [19, 22, 23]

The health of adolescents is intrinsically linked to a nation's development and productivity. Healthy adolescents are more likely to become healthy adults, contributing positively to the workforce and society. Conversely, poor health behaviors established during adolescence can lead to chronic diseases, imposing economic burdens on healthcare systems. The World Health Organization highlights that adolescence is a critical period for laying the foundations of good health, affecting how individuals feel, think, and make decisions. Investing in adolescent health through education and supportive environments is essential for fostering a healthy, productive population. [20, 24, 25]

To enhance health awareness among adolescents, several strategies are recommended: First, integrating comprehensive health education into school curricula can equip students with essential knowledge about nutrition, physical activity, and mental health. Second, government initiatives should focus on creating supportive environments that facilitate healthy choices, such as providing access to recreational facilities and healthy foods. Third, leveraging mass media campaigns can effectively disseminate health information to a broader audience, promoting positive health behaviors. A study on eHealth interventions demonstrated that digital platforms could improve health habits in adolescents, highlighting the potential of technology in health promotion. Implementing these strategies requires collaboration among educators, policymakers, healthcare providers, and communities to create a supportive ecosystem for adolescent health. [21, 22, 23, 24, 25]

The future of any nation depends on that nation's youth, and every youth's health is essential. Good and adequate knowledge about health and a healthy lifestyle is one of the most essential components for the youth and a nation to be healthy and productive. Adolescents should be the target population with good knowledge about health and healthy lifestyles to be healthy future youth for a healthy and productive nation. In this background and based on the study findings, the following are the recommendations:

Creating good awareness about healthy lifestyles among school-going children

The government should develop programs to create awareness about healthy lifestyles among schoolchildren and parents.

A general campaign for a healthy lifestyle through mass media for the general public from the public health point of view

5. Conclusions

According to our findings, the knowledge and awareness about healthy lifestyles among school-going adolescents was moderate to poor. It was also found that the awareness of healthy lifestyles was significantly associated with their father’s educational level and the family's monthly income.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.A. and I.A.E.I.; methodology, A.H.A. and A.M.A.; software, A.M.J.; validation, A.H.A., I.A.E.I., and K.E.A.; formal analysis, P.N. and N.A.M.A.; investigation, R.S.S.A. and O.B.A.A.; resources, M.T.A.A.; data curation, O.F.O.A. and M.S.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.A.A.; writing—review and editing, N.A.H.A.; visualization, A.H.A.; supervision, I.A.E.I. and K.E.A.; project administration, A.H.A.; funding acquisition, Not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Bisha, College of Medicine (Protocol Code: UBCOM-IRB-2024-017, Approval Date: 15 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. Due to ethical restrictions, individual participant data cannot be shared publicly.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at the University of Bisha for supporting this work through the Fast-Track Research Support Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Definition |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| KSA |

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| UNICEF |

United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund |

| PHA |

Public Health Awareness |

| NCDs |

Non-Communicable Diseases |

| SES |

Socioeconomic Status |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| TVT |

Tension-Free Vaginal Tape |

| TVT-O |

Trans-Obturator Tension-Free Vaginal Tape |

References

- Maliye, C.; Garg, B.S. Adolescent Health and Adolescent Health Programs in India. J. Mahatma Gandhi Inst. Med. Sci. 2017, 22, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, D.; Viner, R. Adolescent Development. BMJ 2005, 330, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D.; Kickbusch, I. Health Promotion Glossary. Health Promot. Int. 1998, 13, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minke, S.W.; Smith, C.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Khalema, E.; Raine, K. The Evolution of Integrated Chronic Disease Prevention in Alberta, Canada. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2006, 3, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, T. Measuring Health Lifestyles in a Comparative Analysis: Theoretical Issues and Empirical Findings. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlBuhairan, F.S. Adolescents in Saudi Arabia: Their Status of Health. Ph.D. Thesis, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Data. Adolescents’ Statistics (2023). Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/overview/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Koivusilta, L.K.; Rimpelä, A.H.; Rimpelä, M.K. Health-Related Lifestyle in Adolescence—Origin of Social Class Differences in Health? Health Educ. Res. 1999, 14, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaete, J.; Olivares, E.; Godoy, M.I.; Cárcamo, M.; Montero-Marín, J.; Hendricks, C.; Araya, R. Adolescent Lifestyle Profile-Revised 2: Validity and Reliability Among Adolescents in Chile. J. Pediatr. 2021, 97, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammosova, E.P.; Zakharova, R.N.; Klimova, T.M.; Timofeieva, A.V.; Fedorov, A.I.; Baltakhinova, M.E. The Attitude to One's Own Health Among Native Residents of Yakutia. Probl. Soc. Hyg. Zdravookhr. Istor. Med. 2017, 25, 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kutyrina, I.M.; Filkina, O.M.; Kocherova, O.Y.; Rudenko, T.E.; Malyshkina, A.I.; Savel'eva, S.A.; Vorobyeva, E.A.; Shvetsov, M.Y.; Dolotova, N.V.; Shestakova, M.V. The Awareness and Attitude of Adolescents Concerning Healthy Lifestyles. Probl. Soc. Hyg. Public Health Hist. Med. 2022, 30, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- bin Ridzuan, A.R.; Karim, R.A.; Marmaya, N.H.; Razak, N.A.; Khalid, N.K.; Nizam, K.; Yusof, M. Public Awareness Towards Healthy Lifestyles. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, N.N.; Al-Ali, N.; Al-Ajlouni, R. Attitudes of Jordanian Adolescent Students Toward Overweight and Obesity. Open Nurs. J. 2018, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alissa, E.M.; Alsawadi, H.; Zedan, A.; Alqarni, D.; Bakry, M.; Hli, N.B. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Dietary and Lifestyle Habits Among Medical Students in King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 4, 650–655. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Almaie, S. Knowledge of Healthy Diets Among Adolescents in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2005, 25, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Gautam, P.; Dessie, G.; Rahman, A.; Khanam, R. Socioeconomic Status and Health Behavior in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1228632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health and Development. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/adolescent-health-and-development (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. Coming of Age: Adolescent Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/coming-of-age-adolescent-health (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Krist, L.; Dornquast, C.; Reinhold, T.; Icks, A.; Rathmann, W.; Herder, C.; et al. Health and Health Behaviours in Adolescence as Predictors of Educational Attainment: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 18668. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, M.D.; Chen, E. Socioeconomic Status and Health Behaviors in Adolescence: A Review of the Literature. J. Behav. Med. 2007, 30, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Singh, J.A. World Health Organization Guidance on Ethical Considerations in Planning and Reviewing Research Studies on Sexual and Reproductive Health in Adolescents. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2019, 14, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doku, D.; Koivusilta, L.; Rimpelä, A. Socioeconomic Differences in Smoking Among Finnish Adolescents from 1977 to 2007. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 47, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Health for the World's Adolescents: A Second Chance in the Second Decade. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/substance-use/1612-mncah-hwa-executive-summary.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).