Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is a lentivirus that primarily infects CD4

+ T- lymphocytes leading to progressive immune system deterioration and, if left untreated, the onset of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). In 2023, approximately 1.3 million people contracted HIV, and 630,000 deaths were attributed to HIV-related complications. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified HIV as one of the top ten public health priorities in the United States due to its persistent global burden and challenges in eradication (

HIV and AIDS). Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) is employed as a treatment method for HIV, working to suppress viral replication in CD4

+ T-lymphocytes, thereby preventing the virus from replicating and infecting adjacent cells. cART treatments are composed of 6 primary drug classes, each of which targets a phase of the HIV-1 life cycle in active HIV-1 cells (

Kemnic 2022). However, cART is unable to achieve complete viral eradication of HIV-1 from infected individuals due to the persistence of latent HIV-1 reservoirs. Latency is maintained when HIV integrates itself into the host’s genome but does not produce virions, hampering the ability of cART treatments to detect and attack it, therefore necessitating lifelong cART treatment to maintain viral suppression. Then, at any given moment the latent reservoir can reactivate and propagate throughout the body (

Tanaka et al. 2022). Since cART is only able to prevent viral replication and the spread of HIV-1 when the virus is active, latency is the downfall of such treatments and the primary focus of contemporary HIV-1 research (

Kemnic 2022). To address the challenge of persistent HIV-1 reservoirs, researchers have developed “shock-and-kill” treatments, which aim to induce viral reactivation, thereby exposing latently infected cells to immune clearance and antiretroviral-mediated suppression. These approaches rely on latency-reversing agents (LRAs) to disrupt viral latency, followed by cART and immune-mediated cytotoxicity to eliminate reactivated cells. While researchers have seen positive results in inducing virion production, they have seen little to no reduction in the size of the HIV-1 reservoir post-reactivation. Several models have been proposed to explain this roadblock. Firstly, in vitro LRA tests have indicated that LRAs impair CD8

+ T-cell cytolytic function, compromising the immune clearance of reactivated cells. Secondly, cART treatments have increased the likelihood of immune escape mutations in latent HIV-1 cells (

Kim et al,

2018). Finally, given that HIV-1 dysregulates the immune system, it further attenuates immune responses. Some estimates suggest that the immune system only operates at 10-20% capacity when attempting to kill HIV-1 cells. Thus, it has become evident that adjuvant interventions are needed to eliminate reactivated HIV-1 cells, yet studies on such strategies remain minimal (

Zerbato et al. 2020;

Tanaka et al. 2022). These challenges underscore the need for a more streamlined, efficient, and immunologically compatible HIV-1 eradication strategy.

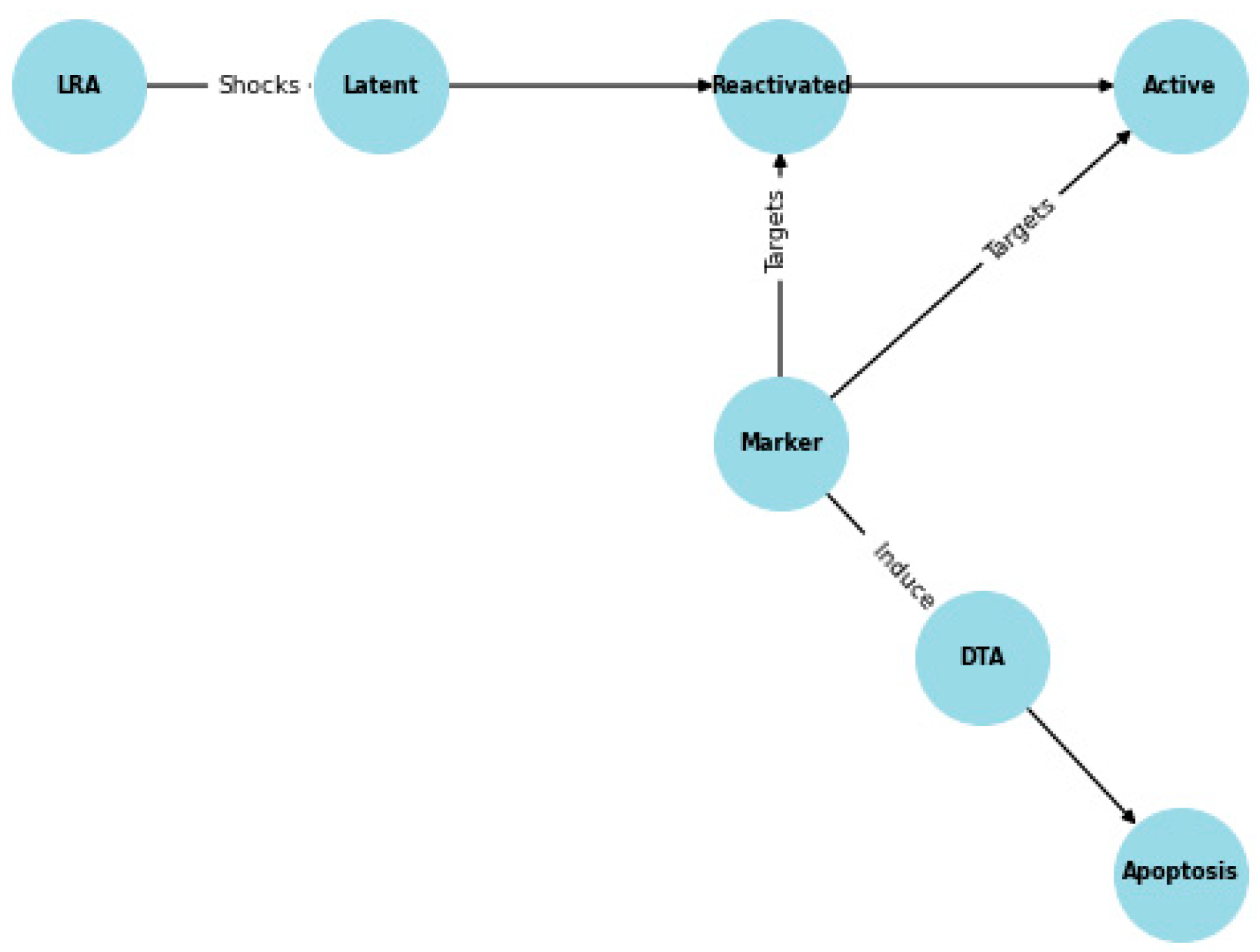

Given the limitations of existing strategies, I propose an alternative approach utilizing an HIV-1 LTR-driven negative selection marker to improve the efficiency of latent reservoir elimination. This marker system utilizes the HIV-1 LTR promoter to drive the expression of diphtheria toxin A (DTA), a potent apoptosis-inducing factor, selectively in active and reactivated HIV-1 cells. Therefore, this marker system is designed to simultaneously reactivate and eliminate HIV-infected cells before viral propagation, overcoming the spread limitations of conventional LRA-based shock-and-kill strategies. We hypothesize that integrating the marker system into the shock-and-kill framework will lead to a significant reduction in the HIV-1 reservoir compared to cART and LRA treatment alone. This study evaluates the long-term effects of this strategy using computational models to assess the population-level impacts of the marker in suppressing HIV. To ensure the NetLogo model closely mimicked real-world HIV treatment conditions, efficacy rates for cART and the immune response were derived from published in vitro and in vivo studies. Studies suggest that cART successfully suppresses approximately 70-90% of actively infected cells per treatment cycle (

Perelson et al. 1997). For the model, 70% was used a conservative estimate. Similarly, the immune system is severely impaired in HIV patients, with cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses ranging between 10-35% efficacy in eliminating active and reactivated HIV cells (

Shan et al. 2012). Based on these values, immune efficacy was set at 15% to represent a weakened but functional immune response.

Methods

This study utilized computational modeling to simulate HIV population dynamics under two conditions: a control group and an experimental group. The NetLogo agent-based model simulated cell-to-cell interactions, while Tellurium was used for kinetic parameter estimation.

Tellurium Python Marker Effectiveness Model:

Tellurium was used for kinetic parameter estimation, defining rate constants k₁-k₅ based on empirical data.

Derivation of Rate Constants:

Latency Reactivation Rate (k₁): LRAs activate 3.7% of latent HIV cells per day, yielding k₁ = 0.00156 hr⁻¹ (

Battivelli et al. 2013).

Marker-Induced DTA Transcription (k₂): Half-maximal transcription occurs in 4 hours, giving k₂ = 0.1733 hr⁻¹ (

Hanauske-Abel et al. 2013).

Marker Transcription Efficiency (k₄): Tat-mediated transcription follows a similar 3-hour activation time, yielding k₄ = 0.231 hr⁻¹.

Saturation Effects in Apoptosis (k₅): Modeled using Michaelis-Menten kinetics to cap apoptosis at a biologically realistic rate.

These rate constants were plugged into the following equations:

LatentHIV' = -k1 * LatentHIV * LRA

ActiveHIV' = (k1 * LatentHIV * LRA) - (k3 * ActiveHIV * k2)

DTA' = k2 * ActiveHIV * Marker

DeadCells' = ActiveHIV * k2 * k3

These equations and rate constants modeled what a system of healthy cells, active HIV-1 cells, and latent HIV-1 cells would look like to derive the marker effectiveness, which were calculated with the following equation:

Figure 2.

Tellurium Marker Effectiveness Model Logic.

Figure 2.

Tellurium Marker Effectiveness Model Logic.

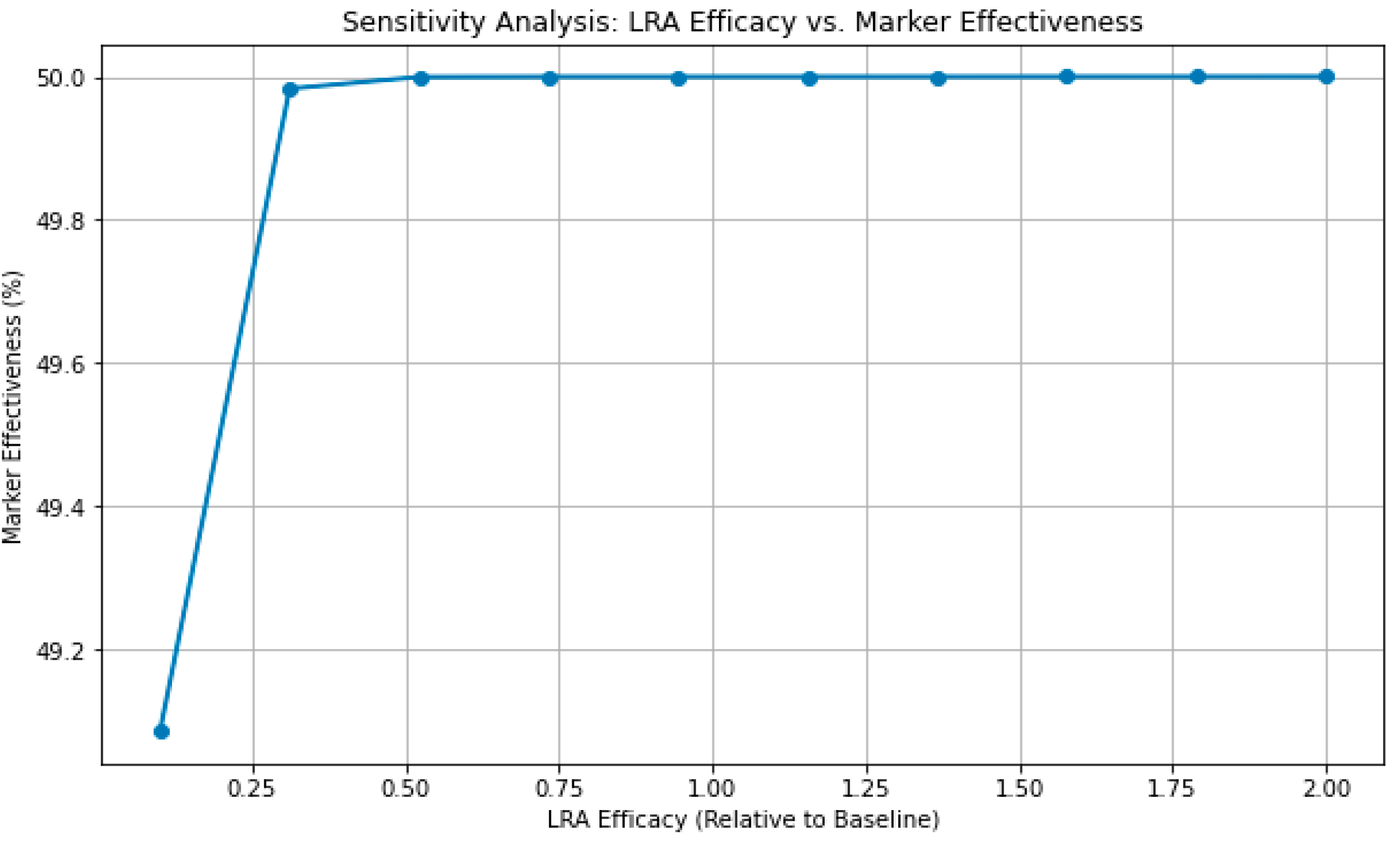

Tellurium Python Sensitivity Analysis:

To investigate the influence of LRA efficacy on marker-induced apoptosis in active HIV cells, a sensitivity analysis was performed by varying the LRA activation rate constant (k1). The rate constant was scaled between 10% and 200% of its baseline value (0.00156 hr⁻¹) while keeping all other parameters constant. The model was simulated over 100 hours with 200 time points for each efficacy level using the Tellurium modeling environment. The output measured the cumulative count of dead cells, which serves as a proxy for the effectiveness of the marker in inducing apoptosis. This analysis provided insights into how modifications in LRA efficacy impact the "shock and kill" mechanism underlying HIV-1 eradication strategies.

NetLogo Model

To create an accurate representation of HIV infection dynamics, the following key processes were carefully modelled:

cART: Targets only active HIV cells and stops around 70% of active cells from infecting other cells, but does not affect newly reactivated cells until they spread, as per observations derived from in vitro and in vivo studies.

The immune response: Eliminates around 15% of all active and reactivated cells, representing a weakened immune response.

Experimental treatment: Instantly eliminates 49% of latent, active, and reactivated HIV cells before they can spread further.

Latency Reversal: LRAs reactivate 5% of latent cells, leading to a gradual reactivation process.

HIV Spread: Unrestricted active and reactivated HIV cells spread to 5-6 healthy cells in their area prior to their death.

The control group initially had 4750 healthy cells, 200 active cells, and 50 latent cells. The control group consisted of the HIV spread, latency reversal, immune response, and cART metrics and processes detailed above. On the other hand, the experimental group initially had 4750 healthy cells, 200 active cells, and 50 latent cells. The experimental group contained the HIV spread, latency reversal, immune response, and cART metrics and processes detailed above. The only difference however was the addition of the experimental treatment metric and process detailed above.

Results and Discussion

Tellurium Marker Effectiveness Results:

The Tellurium simulations demonstrated a 49.09% marker effectiveness, indicating that nearly half of the reactivated HIV-1 cells underwent apoptosis. Compared to LRA-only treatment, marker-driven apoptosis significantly reduced the size of the HIV-1 reservoir.

Figure 3.

Tellurium Simulation.

Figure 3.

Tellurium Simulation.

Tellurium Sensitivity Analysis Results:

The sensitivity analysis revealed that increasing LRA efficacy leads to a higher count of dead cells, suggesting a direct, causal relationship between LRA potency and marker effectiveness. As LRA efficacy increased, more latent HIV cells were reactivated and subsequently driven to apoptosis by the treatment, resulting in greater cell death. This indicates that the marker’s performance is primarily driven by the efficiency of the LRA in activating latent cells. The results suggest that enhancing LRA efficacy could significantly improve treatment outcomes. These results suggest that while the ‘kill’ mechanism is robust, the ‘shock’ component, which relies on reactivating latent cells, remains a limiting factor.

Figure 4.

LRA Sensitivity Analysis.

Figure 4.

LRA Sensitivity Analysis.

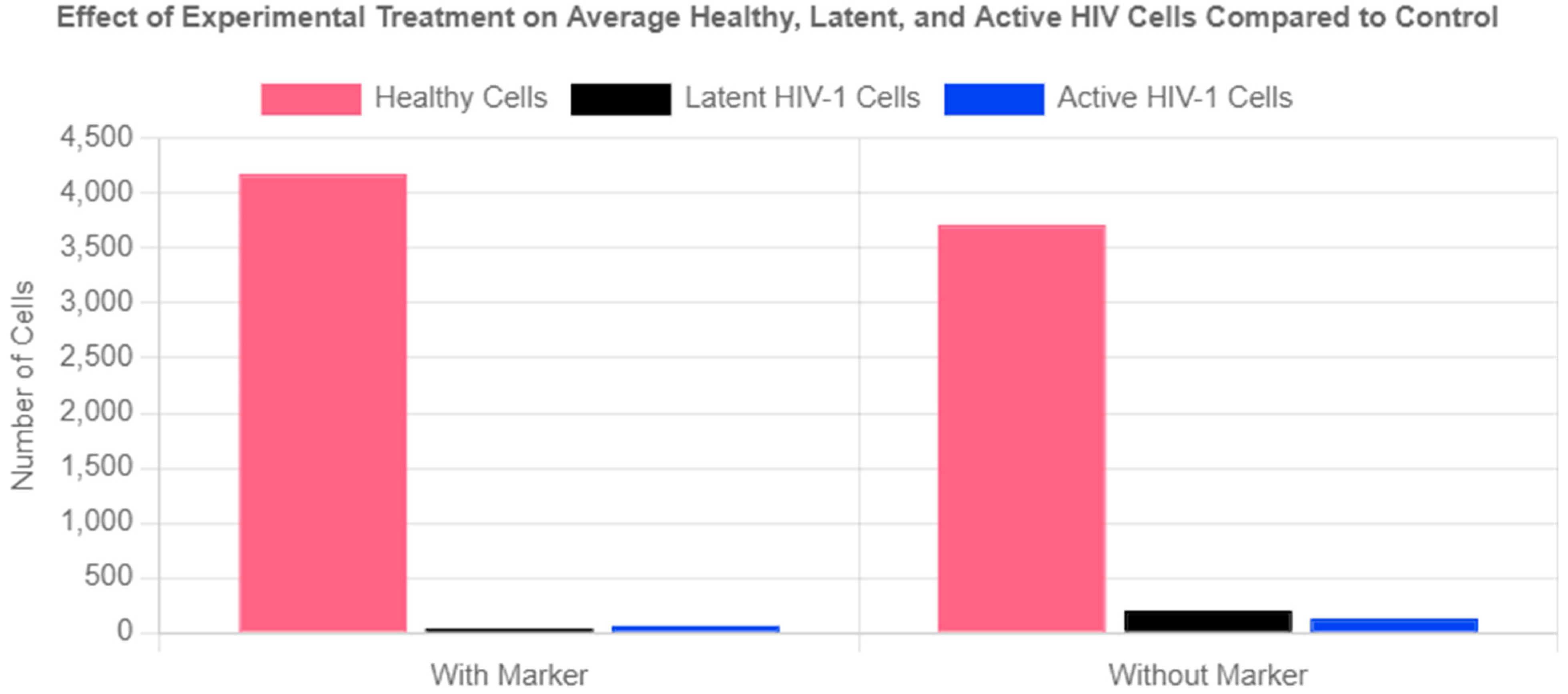

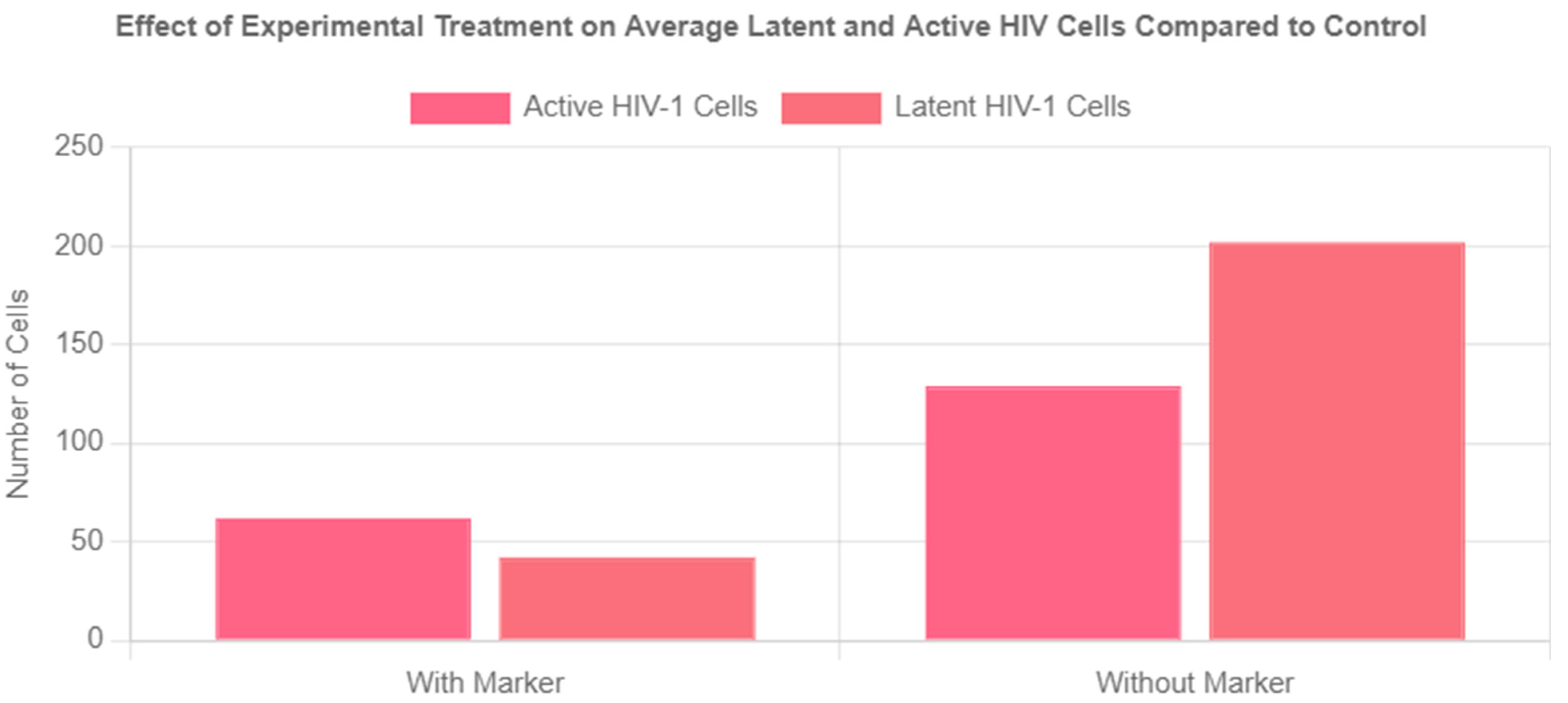

NetLogo Population Simulation Results:

The experimental group exhibited a 79% reduction in the latent reservoir compared to the control group. The marker also led to a 52% reduction in active HIV cells. Overall, the marker system achieved a 63% total reduction in infected cells compared to cART and the immune system clearing HIV-1 infected cells alone. Finally, the marker was highly effective in preventing the spread of HIV, as evidenced by the 12.5% higher number of healthy cells in the experimental group compared to the control.

Figure 5.

Effect of Experimental Treatment on Average Healthy, Latent, and Active HIV Cells Compared to Control.

Figure 5.

Effect of Experimental Treatment on Average Healthy, Latent, and Active HIV Cells Compared to Control.

Figure 6.

Effect of Experimental Treatment on Average Latent and Active Cells Compared to Control.

Figure 6.

Effect of Experimental Treatment on Average Latent and Active Cells Compared to Control.

Table 1.

Average Values of HIV-1 Population Dynamics with Experimental Treatment.

Table 1.

Average Values of HIV-1 Population Dynamics with Experimental Treatment.

| Healthy Cells |

Average Number of Latent HIV-1 Cells |

Average Number of Active HIV-1 Cells |

| 4178 |

42 |

62 |

Table 2.

Average Values of HIV-1 Population Dynamics without Experimental Treatment.

Table 2.

Average Values of HIV-1 Population Dynamics without Experimental Treatment.

| Healthy Cells |

Latent HIV-1 Cells |

Active HIV-1 Cells |

| 3714 |

202 |

129 |

Conclusion

It is important to clarify that in silico research has inherent limitations. Modeling complex cellular processes to a high degree of accuracy is outside the scope of in silico testing conducted in this research. Therefore, the computational methods introduced here are designed to study long-term trends rather than fixed timeframes. Instead of modeling HIV progression over specific hours or days, these simulations focus on the conceptual impact of this novel, marker-based therapy in reducing the viral reservoir over time and the overall population trends in an HIV-1 infected system. Future models could provide more specific results by incorporating a detailed chronological framework. The results demonstrate a clear distinction between the control and experimental groups, validating the marker's role in reducing the spread of HIV-infected cells. These findings suggest that this experimental treatment provides a viable strategy for enhancing shock-and-kill treatments by directly inducing apoptosis in reactivated HIV-1 cells. Future research should focus on further in vitro validation and potential in vivo applications to assess clinical feasibility. It should also focus on developing a vector specific to the structure of the treatment for effective delivery.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with computational assistance from NetLogo and Tellurium. Special thanks to Dr. Jennifer Kirchherr for guidance on HIV dynamics modeling.

References

- Emilie, Battivelli, Matthew S Dahabieh, Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen, J Peter Svensson, Israel Tojal Da Silva, Lillian B Cohn, Andrea Gramatica, Steven Deeks, Warner C Greene, Satish K Pillai, Eric Verdin (2018) Distinct chromatin functional states correlate with HIV latency reactivation in infected primary CD4+ T cells. [CrossRef]

- Hanauske-Abel, Hartmut M., Deepti Saxena, Paul E. Palumbo, Axel-Rainer Hanauske, Augusto D. Luchessi, Tavane D. Cambiaghi, Mainul Hoque, et al. “Drug-Induced Reactivation of Apoptosis Abrogates HIV-1 Infection.” PLoS ONE 8, no. 9 (September 23, 2013). [CrossRef]

- Kemnic, Tyler R. “HIV Antiretroviral Therapy.” StatPearls [Internet]., September 20, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513308/.

- Kim, Youry, Jenny L. Anderson, and Sharon R. Lewin. “Getting the ‘Kill’ into ‘Shock and Kill’: Strategies to Eliminate Latent HIV.” Cell Host & Microbe 23, no. 1 (January 2018): 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.004. [CrossRef]

- NIH. 2024. “HIV and AIDS Fact Sheet.” National Institutes of Health. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/hiv-and-aids-basics.

- Perelson, Alan S., Paulina Essunger, Yunzhen Cao, Mika Vesanen, Arlene Hurley, Kalle Saksela, Martin Markowitz, and David D. Ho. “Decay Characteristics of HIV-1-Infected Compartments during Combination Therapy.” Nature 387, no. 6629 (May 1997): 188–91. [CrossRef]

- Shan, Liang, Kai Deng, Neeta S. Shroff, Christine M. Durand, S. Alireza. Rabi, Hung-Chih Yang, Hao Zhang, Joseph B. Margolick, Joel N. Blankson, and Robert F. Siliciano. “Stimulation of HIV-1-Specific Cytolytic T Lymphocytes Facilitates Elimination of Latent Viral Reservoir after Virus Reactivation.” Immunity 36, no. 3 (March 2012): 491–501. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Kiho, Youry Kim, Michael Roche, and Sharon R. Lewin. “The Role of Latency Reversal in Hiv Cure Strategies.” Journal of Medical Primatology 51, no. 5 (August 27, 2022): 278–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmp.12613. [CrossRef]

- Zerbato, Jennifer M, Harrison V Purves, Sharon R Lewin, and Thomas A Rasmussen. “Between a Shock and a Hard Place: Challenges and Developments in HIV Latency Reversal.” Current Opinion in Virology 38 (October 2019): 1–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).