Submitted:

02 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

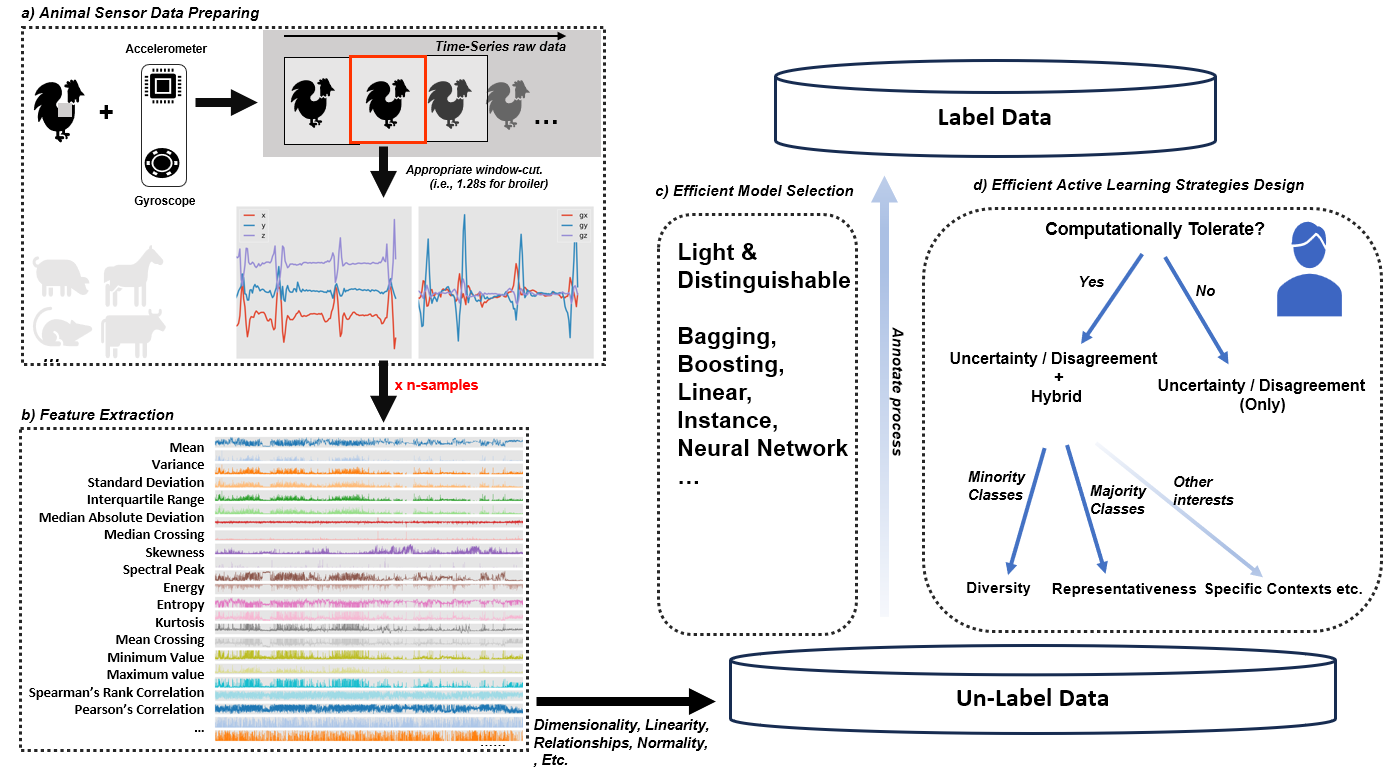

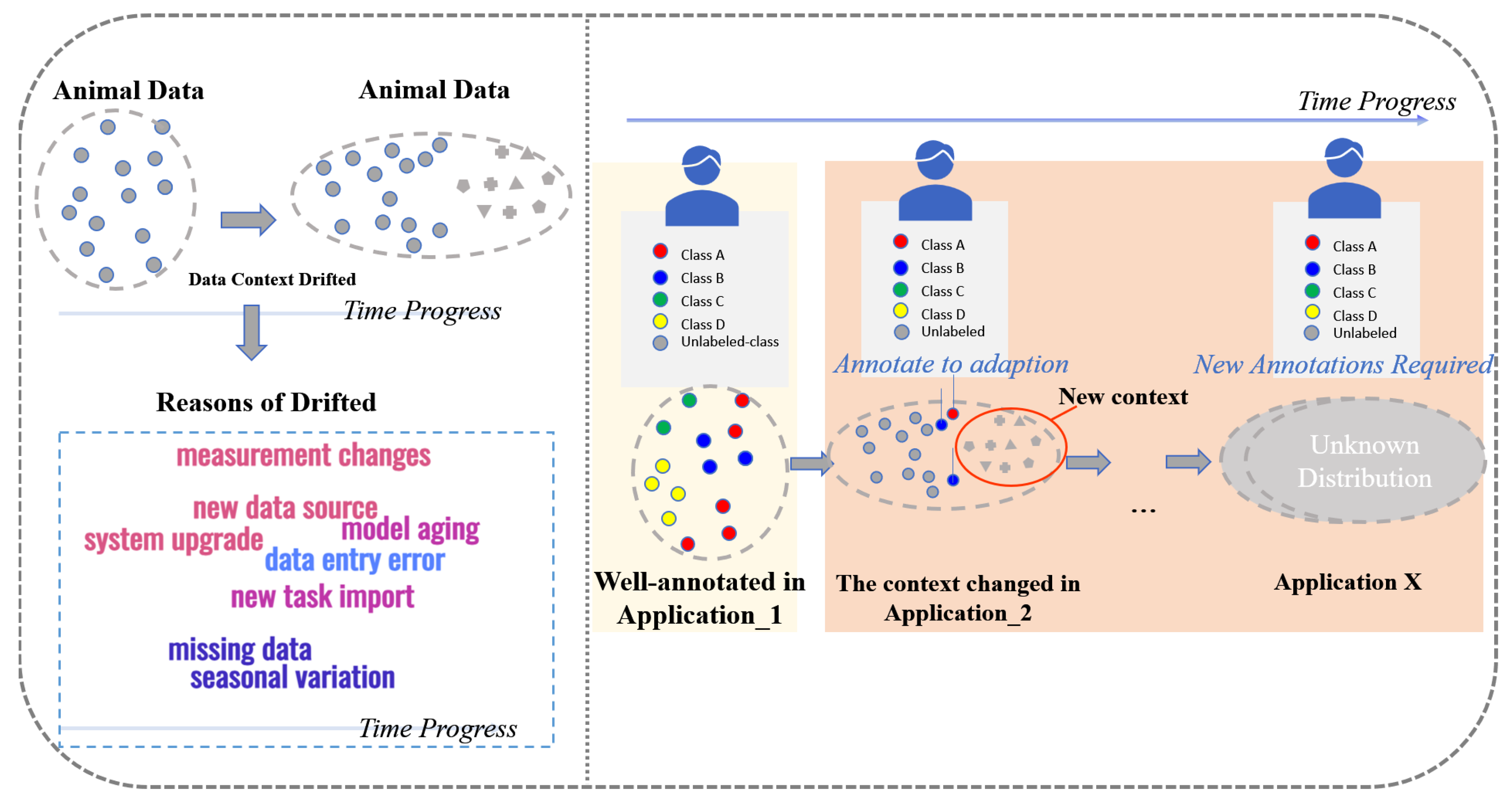

Animal welfare research increasingly relies on behavioral analysis as a non-invasive and scalable alternative to traditional metabolic and hormonal indicators. However, there remains an annotation challenge due to the diversity and spontaneity of animal actions, which may require expertise and knowledge in annotations, thorough look-back examination, and re-annotation to ensure the models can generalize well. In this regard, a scheme to facilitate the annotation scenarios is to selectively annotate less proportional but informative samples, called "Active Learning." We comprehensively evaluated combining 7-Active learning and 11-Classifiers to expose their different converge effects until they are fine-tuned. Including 3-uncertainty, Random Sampling, Core-Set-Scores (CSS), Expected-Maximized-Change (EMC), and Density-Weighted Uncertainty (DWU) sampling strategies let classifiers of linear-based, boosting-based, rule-based, instance-based, backpropagation-based, and ensemble-based classifiers to simulate the annotation process on laying hens of 27-Classes dataset collected by sensors of accelerometer and gyroscope. Results indicate that simpler AL strategies in handled high-dimensional feature space outperform complex-designed AL in efficiency and performance. Also, we found that the ensemble classifiers (Random Forest Classifier and Extra Trees Classifier) and the boosting-based models (LightGBM and Hist Gradient Boosting Classifier) exhibited learning instabilities. Additionally, increasing the query batch sizes can enhance annotation efficiency with slight performance loss. These findings contribute to the advancement of efficient behavior recognition in precision livestock farming, offering a scalable framework while the real-world applications are appealing to well-annotated animal datasets.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Regulations and Policies on Animal Welfare

1.2. Metabolic Signs and Hormones as Indicators of Animal Welfare

1.3. Behavior Patterns as Indicators of Animal Welfare

1.4. Smart Computing and Smart Sensing for Animal Welfare

1.5. Annotation Issue in Animal Behavior Analysis

- We introduce a 27-class behavior recognition framework for laying hens, which surpasses the classification scope of many existing animal behavior studies. The high complexity and class imbalance inherent in this dataset provide a unique opportunity to examine the impact of imbalanced class distributions on machine learning model performance and active learning strategies.

- We conduct a systematic evaluation of machine learning classifiers and active learning strategies, identifying distinct model convergence patterns and revealing performance degradation in boosting classifiers, a phenomenon rarely addressed in the literature.

- We integrate uncertainty-based sampling with recent advancements in active learning, incorporating density, representativeness, and diversity metrics, and assess their effectiveness in annotating both majority and minority behavior classes.

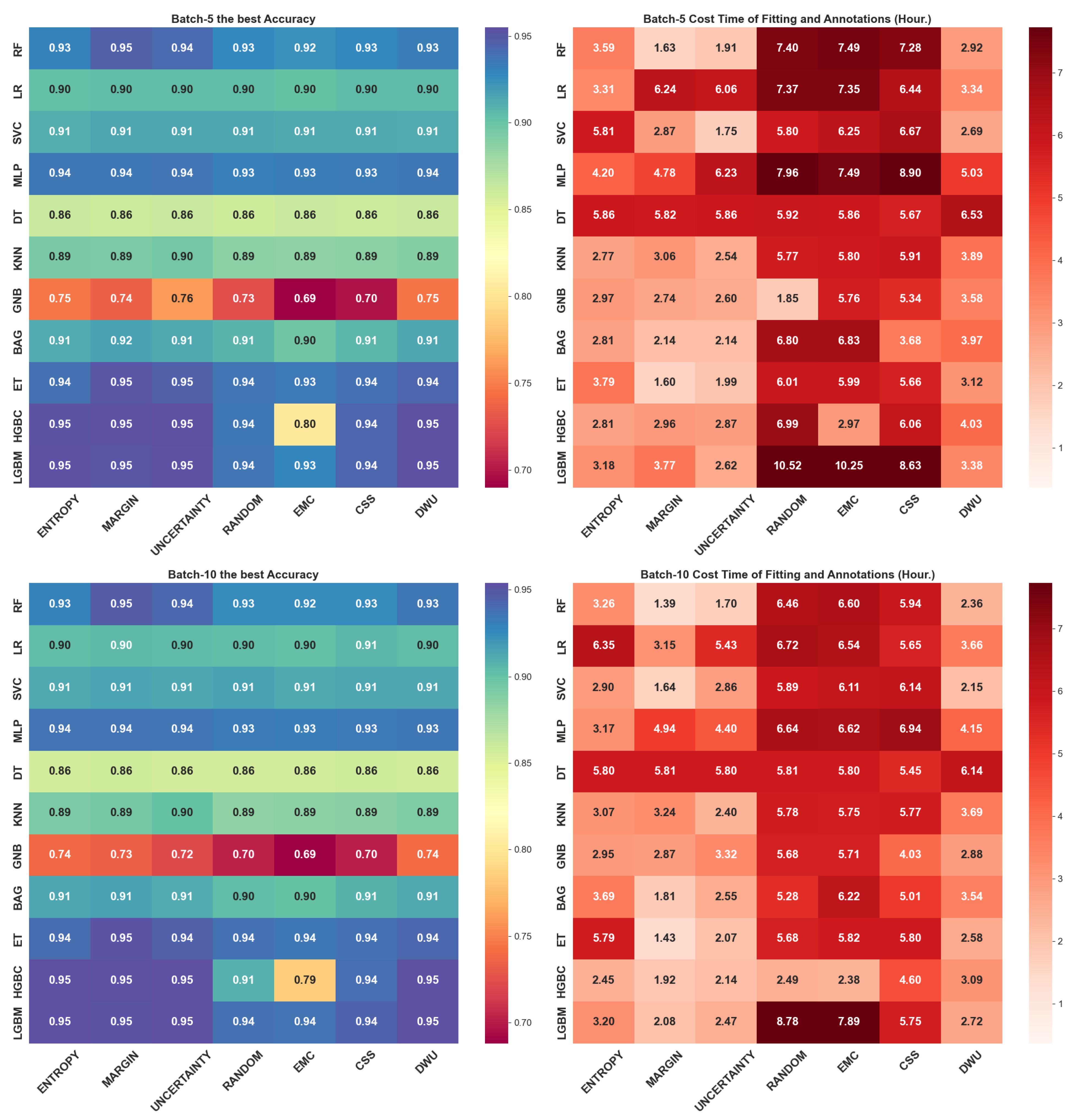

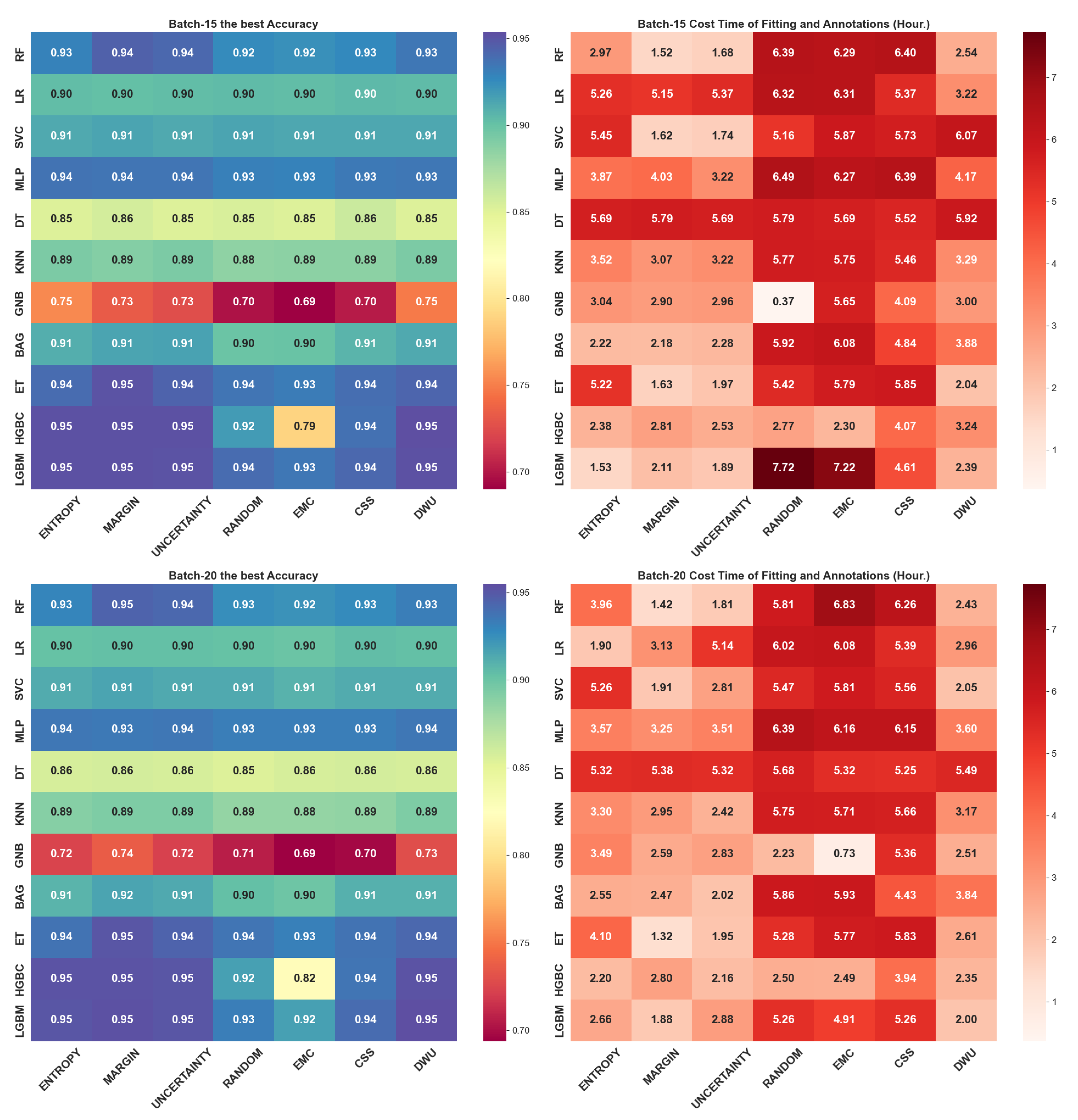

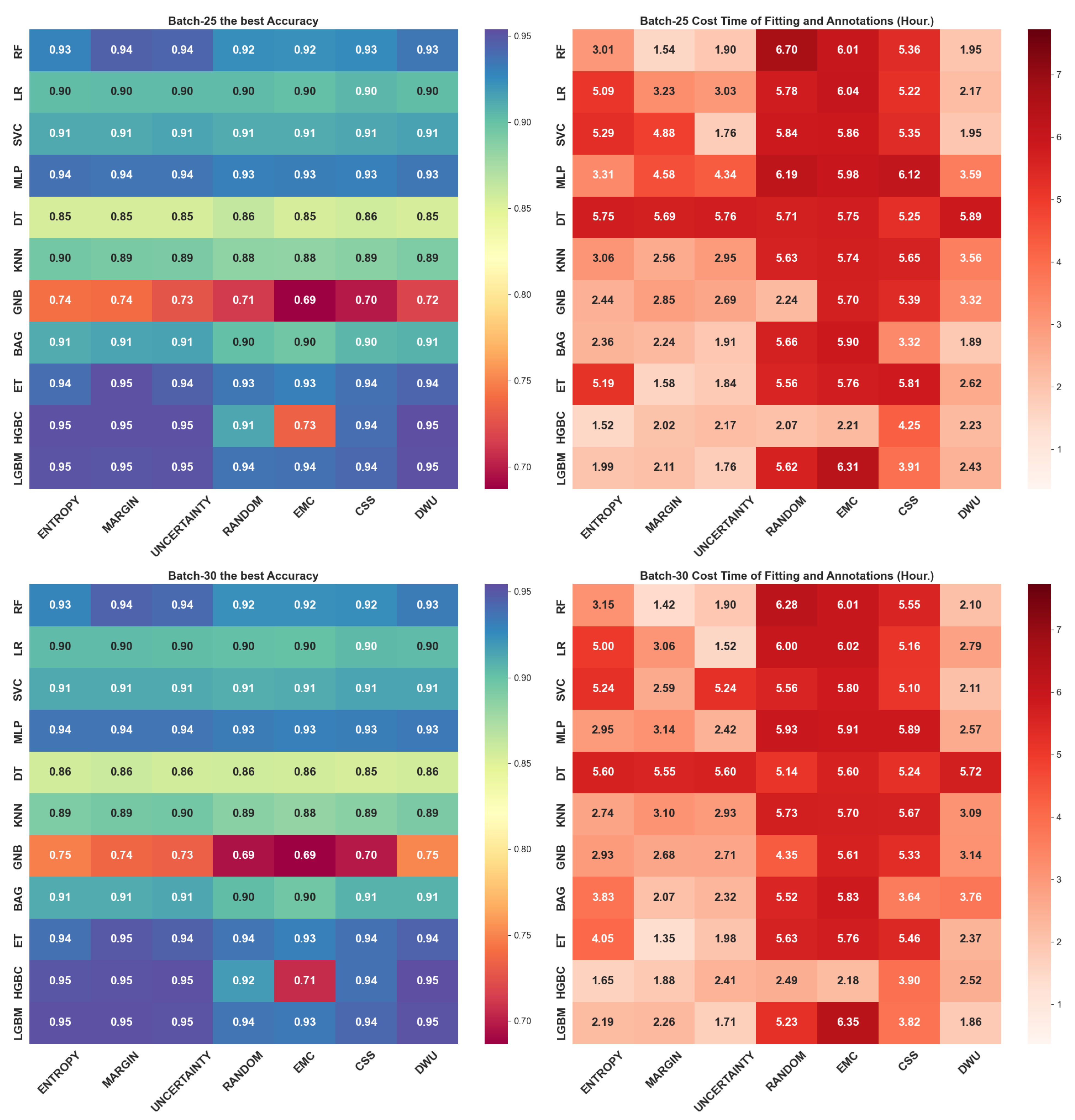

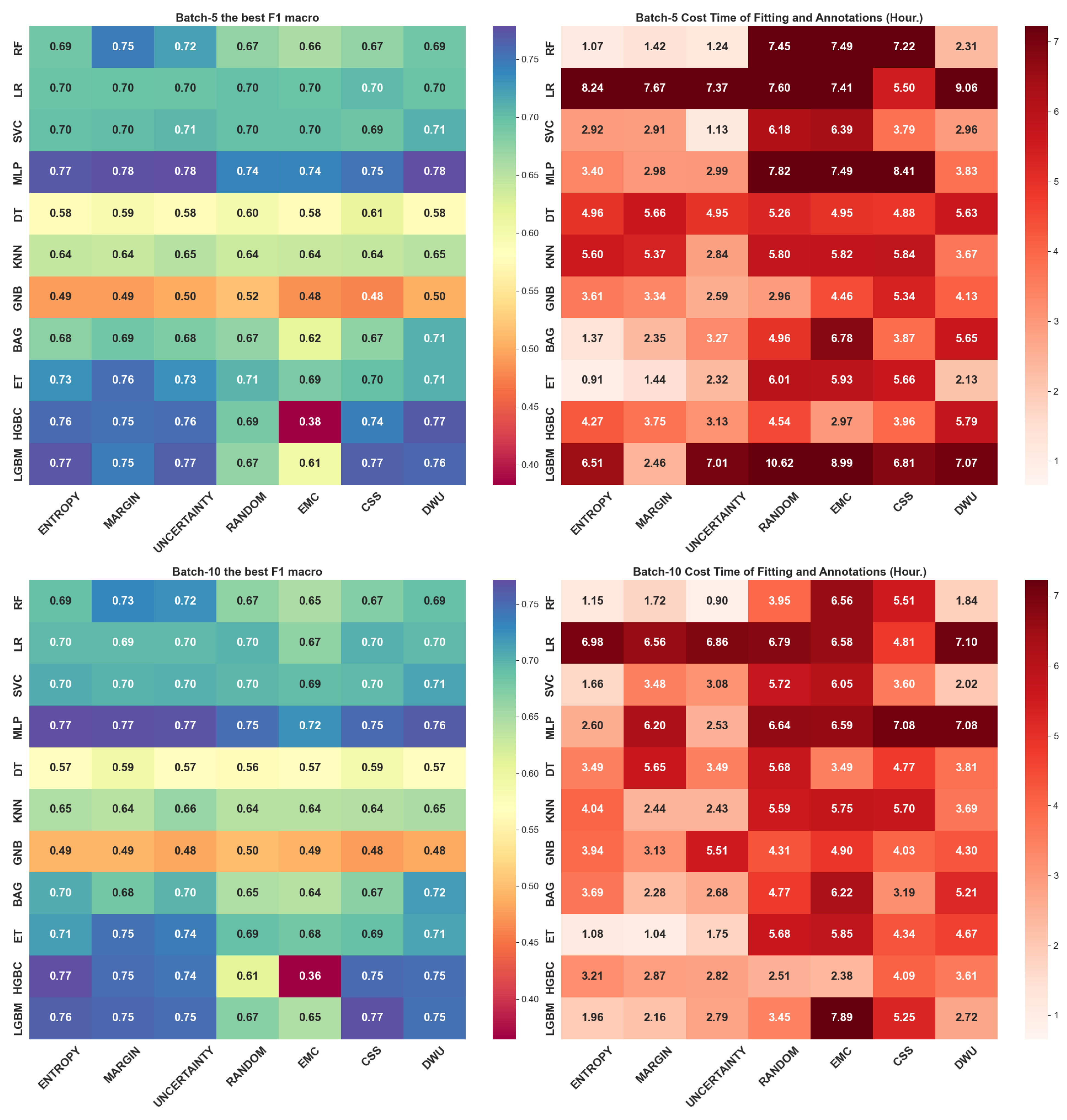

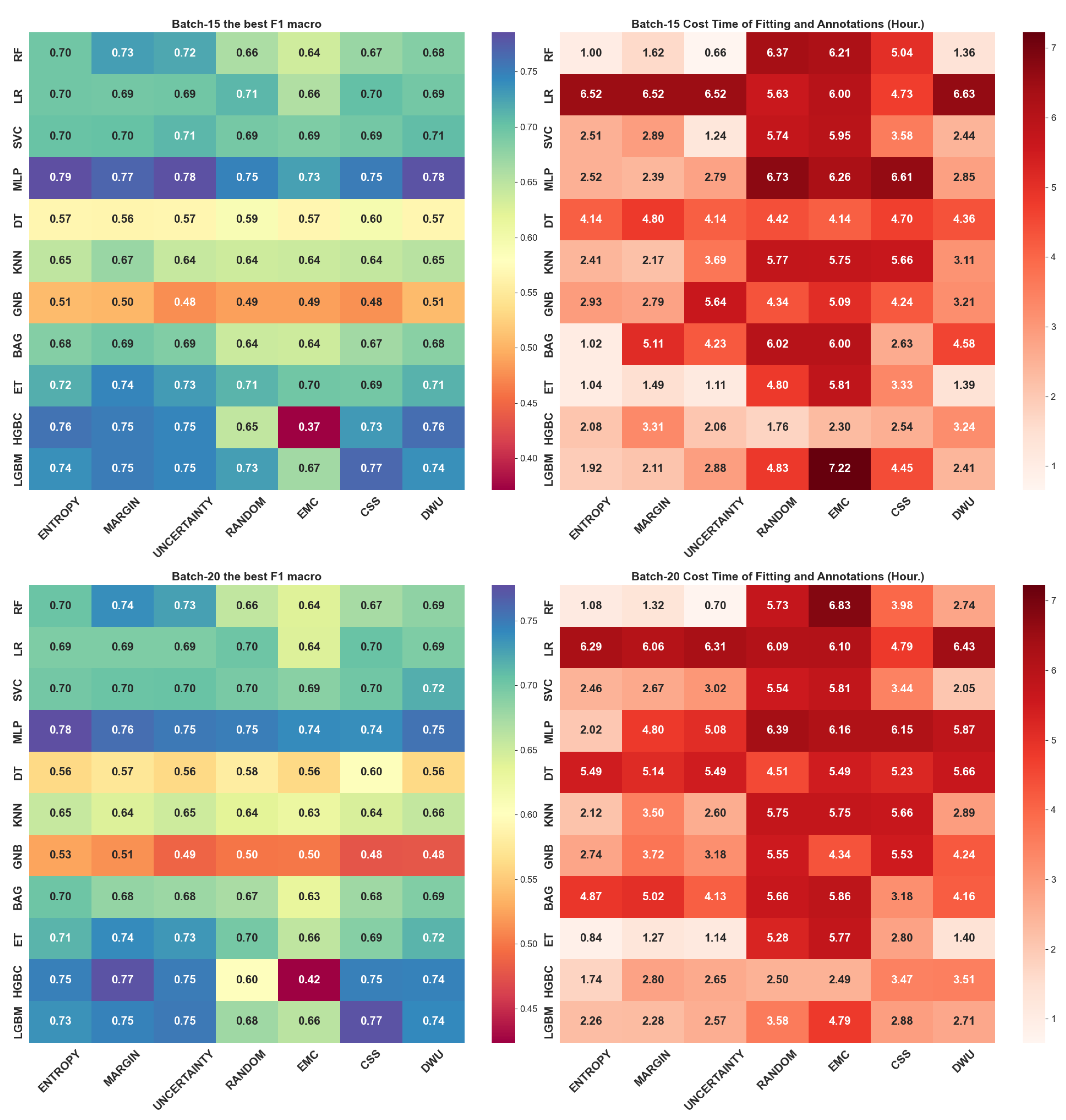

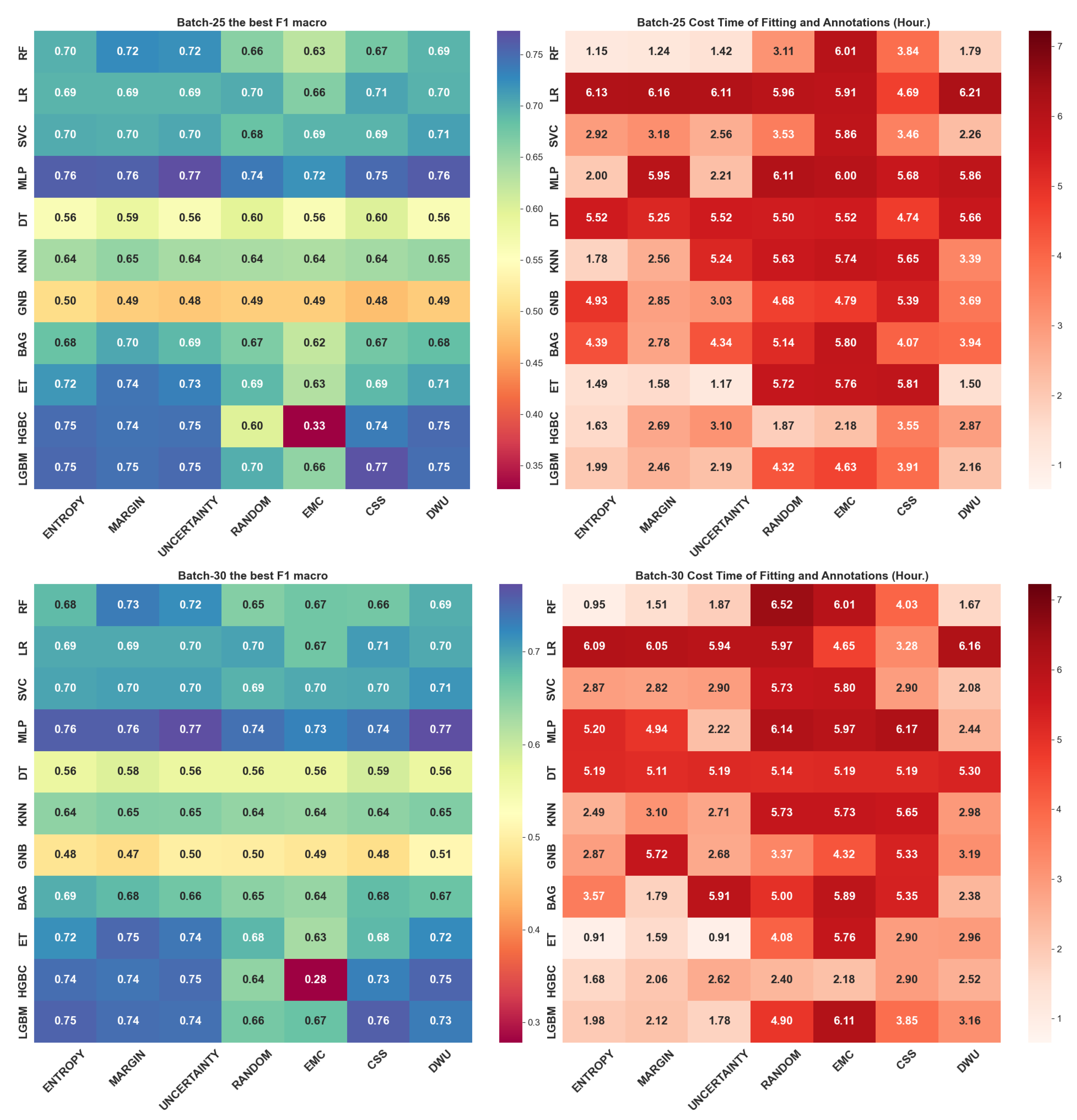

- We analyze the effect of different query batch sizes to annotation efficiency and model performance, demonstrating that larger batch sizes significantly enhance annotation efficiency while maintaining only a marginal reduction in predictive accuracy.

2. Methodology

2.1. Machine Learning

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): SVM [34] is excellent in generating decision boundaries among varying dimensional space, to fine-tune its model, and avoiding issues of under-fitting or over-fitting; its regularization adjusts through shrinking or expanding distance between two types of margin (e.g. sort margin and hard margin), enabling capturing a variety of relationships of data such as the radial, linear or nonlinear. In earlier studies, it is used in cow behavior recognition on a 9-features low-dimensional accelerometer dataset with respect to standing, lying, ruminating, feeding, walking normaly, walking abnormally, however, it is unable to recognize the lying down of cows with zero sensitivity and zero precision [35].

- K-nearest-neighboughrs (KNN): KNN is well-known in predicting house prices, since its mechanism is superior to learning the class-centroid samples and their neighbor samples, which adhering with the house prices correlated in regionally. However, its performance largely depends on whether the data has clustering characteristics to discriminate easily. In previously, it is proposed in GPS telemetry or dead-reckoning of animal position recognition and outperforming other complex models [36].

- Logistic Regression (LR): LR as one of linear models learning features linearly, and then, using sigmoid or softmax to transform the numerical values, enabling multi-classification, optimized in the direction of maximum likelihood function, it can yield probability for classifications so that can be used in animal movement analyses [37].

- Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB): GNB is based on the Bayes theorem based on an assumption of features that are independent and follow Gaussian distribution, therefore, it is fast to handle high-dimensional data. In earlier study of dog behavioral classification with respect to standing, walking, running, sitting, lying down, and resting, it outperforms Decision Tree, KNN, and SVM [38].

- Decision Tree (DT): DT constructed with tree nodes and splitted branch hierarchically, samples will be separated into subsets driving by infomration gain. It can handle features containing missing values based on the directional mechanism. In animal behavior recognition, it especially takes priority in classifying the behavior at different activity intensity levels, such as sports momentum at different levels, still and walking. Also, the transition state between standing and lying down between animal durations [39].

- Random Forest Classifiers (RF): RF is based on an ensemble of trees by consolidating a multitude of tree’s decisions on classifications. It selects the best split at each node by considering a subset of features and using bootstrapped samples which is part of the whole training dataset. Compared with DT, which takes advantages at learning data with higher generalizability and robustness, thus avoiding over-fitting. It was applied in accelerometer-based free-grazing cows behavior recognition of feeding, lying, standing and walking [40].

- Bagging Classifier (BAG): BAG is an ensemble of classifers at meta level, in this study we adopted theDTas its basic component to benchmark.

- Extra Trees (ET): ET as ensemble classifier which is similar to RF, however, it introduces with more randomness into threshold for each feature and using the whole dataset (e.g. No Bootstrapping) for training each tree, therefore, it competing to RF with higher generalizability and speed, also previous study claims that it can be used for a wide variety of animal species, when recognizing 13-behaviors of cattle based on with accelerometer-based motion data [41].

- Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM): LGBM as a boosting algorithm is efficient to training on large-scale data since it used histogram-based feature which are discretized from origin features. Its optimization relying on an ensemble of trees conducted in a leaf-wise way [42].

- Histogram Based Gradient Boosting Classifier (HGBC): HGBC is faster than LGBM in handling large-scale dataset, which is as the same boosting-based and histogram feature-based components as LGBM, where its difference optimized in a level-wise way. In previous study of accelerometer-based cattle behavior recogntion, it outperforms RF, SVM, and KNN [43].

- Multi layers perceptrons (MLP): MLP as deep learning consisted of layers of interconnected neurons and corresponding weights to pass through the activation function, input values from features therefore can transformed into output values for prediction. With a variety of loss functions, it enables learning non-linear relationship from features, however, it usually requires large amount of data to support its generalizability for multi-classifcation [44].

2.2. Active Learning

2.3. Query Strategies

2.3.1. Least Confidence (UNCERTAINTY)

2.3.2. Entropy

2.3.3. Margin

2.3.4. Disagreement by Query-By-Committee

2.3.5. Expected Maximized Change (EMC)

2.3.6. Core-Set-Score (CSS)

- For each , there could a sample taking the minimal difference represented as core-score.

- Querying the sample with the largest core score among .

2.3.7. Density Weighted Uncertainty (DWU)

- Calculating the average difference between and samples belonging to its predefined k-neighbors as density.

- Synthesized the density and the UNCERTAINTY as informativeness score, querying based on the samples that contribute max value.

2.4. High-Dimentional Linearity of Feature Extraction

3. Experiment Design

3.1. Simulation

- Firstly, the whole dataset is separated into training and testing parts, as 70% (6356) vs 30% (2725), respectively.

- Secondly, choose 1% of training (63) to learn our classifiers as the initial label pool, where the remaining 99%(2725) parts are regarded as unlabeled pool.

- Thirdly, the batch size of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 are the label frequencies to inform classifiers to update themselves and the informativeness rank of the unlabeled pool, which is viewed as an iteration of active learning.

- Lastly, iteratively runs the active learning process to query the sample from the unlabeled pool into the labeled pool until the latter is exhausted.

3.2. Metrics

- True Positive (): The number of correctly predicted positive class sample.

- False Positive (): The number of incorrectly predicted positive class.

- True Negative (): The number of correctly predicted negative class sample.

- False Negative (): The number of incorrectly predicted negative class sample.

4. Experimental Results

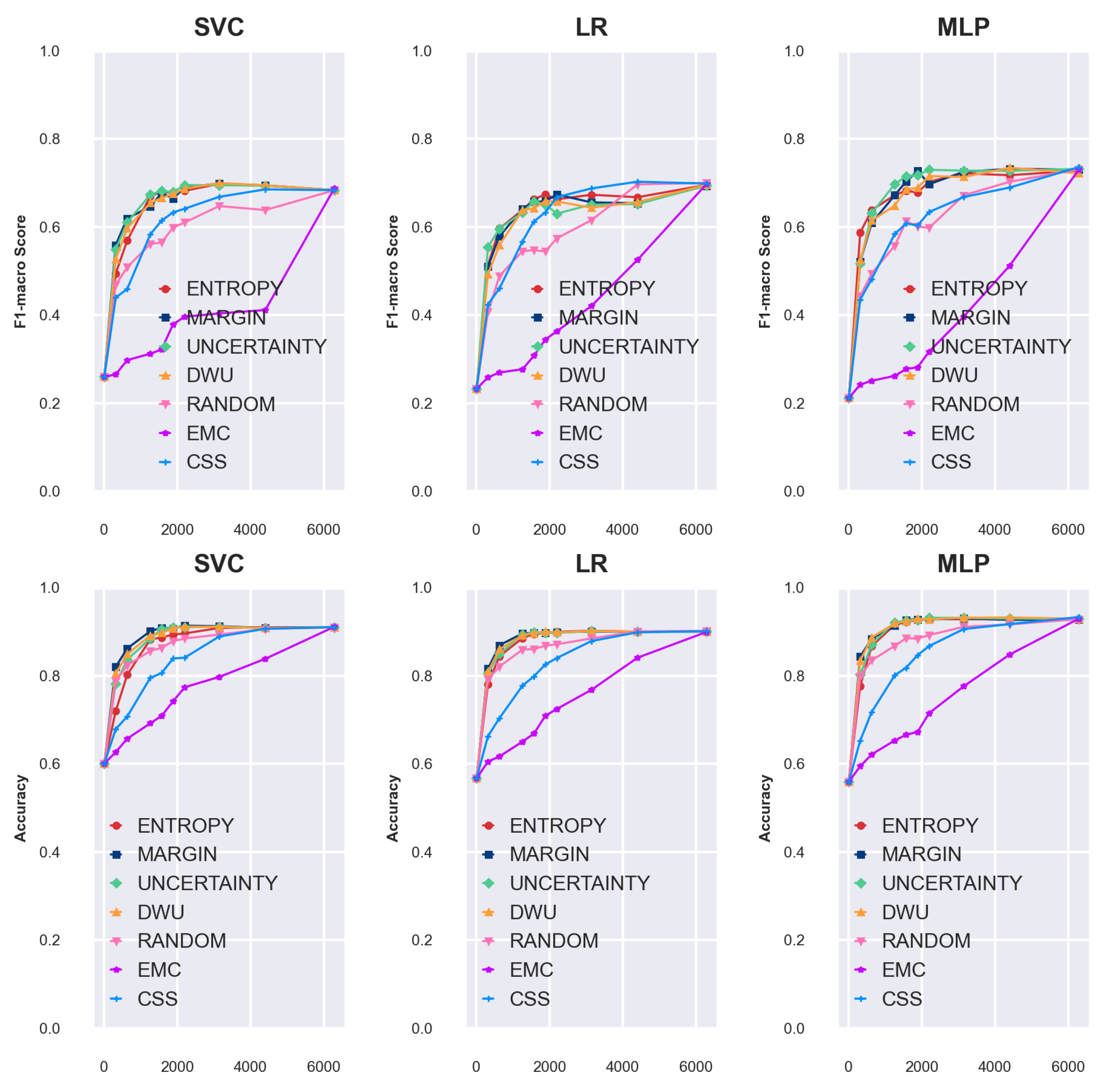

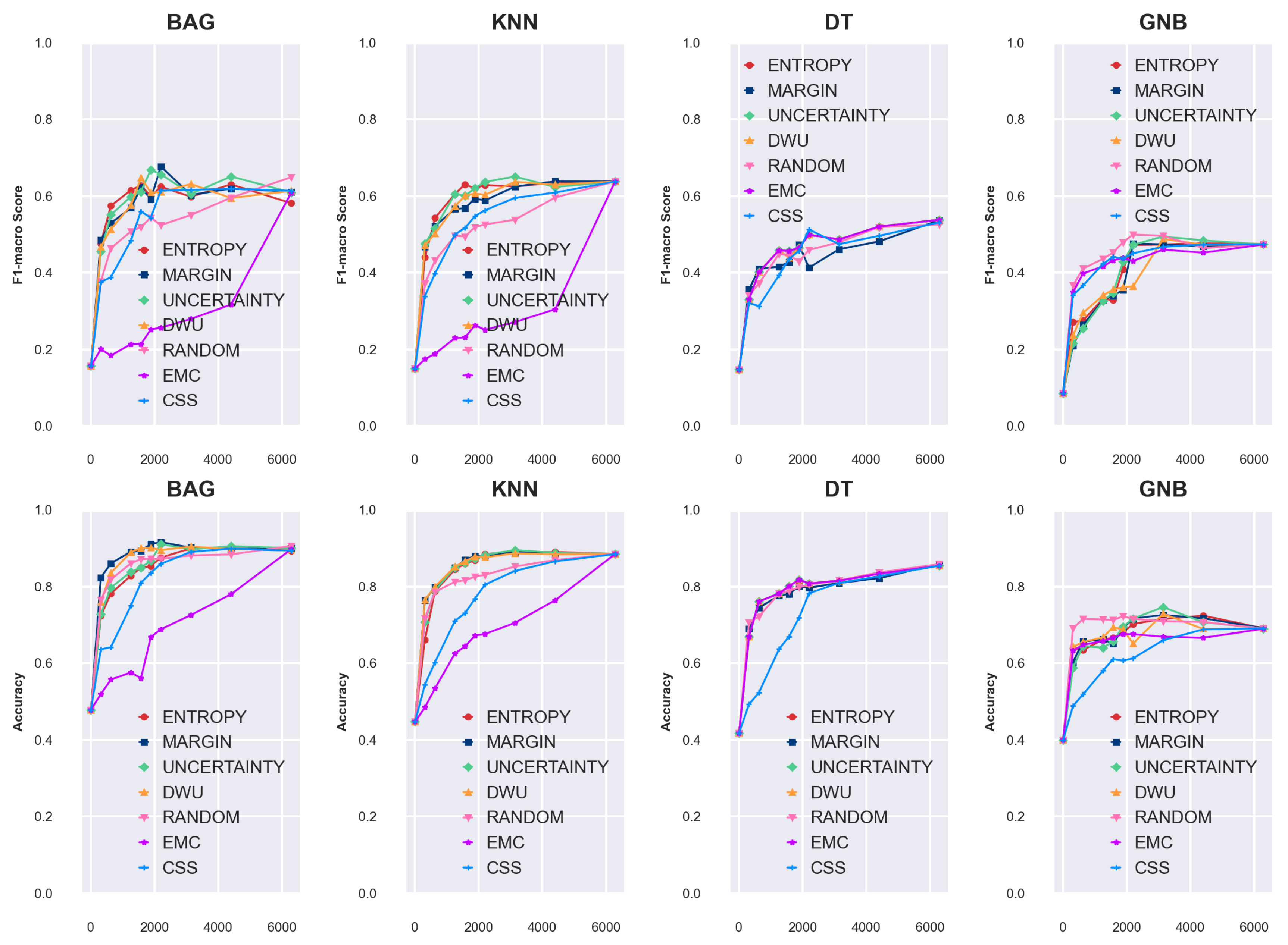

4.1. Simulation of Batch Size 5

- Active Learning: batch_size = 5

- Data Split: random_state = 2021

- Model : random_state = 42

- Scaler Wrapping: Model would be wrapped with a preprocessing function of standardscaler before fitting, which is , where the x represents feature vector, u is mean of the feature, and s is standard deviation of the feature.

- LGBM & ENTROPY: 0.773 at 3160 annotation points

- ET & MARGIN: 0.756 at 1515 annotation points

- RF & MARGIN: 0.746 at 1310 annotation points

4.2. Query Batch Size Effect

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion-Hybird of Diversity, Representativeness and Density

5.2. Supporting Artificial Neural Network

5.3. Facilitate Muti-Modal Animal Behavior Recognition

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BAG | Bagging Classifier |

| CSS | Core-Set-Score |

| DWU | Density-Weighted Uncertainty |

| EMC | Expected Maximized Change |

| ET | Extra Trees Classifier |

| F1-macro | Macro-averaged F1 Score |

| GNB | Gaussian Naive Bayes |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HGBC | Histogram-Based Gradient Boosting Classifier |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| QBC | Query-by-Committee |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RFID | Radio-Frequency Identification |

| SVC | Support Vector Classifier |

References

- Alves, R.R.N.; Policarpo, I.d.S. Ethnozoology. Ethnozoology 2018, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R.; Aguilar, J.; Toro, M.; Pinto, A.; Rodríguez, P. A systematic literature review on the use of machine learning in precision livestock farming. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 179, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwin, R. Evacuation of Pets During Disasters: A Public Health Intervention to Increase Resilience. American Journal of Public Health 2017, 107, 1413–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, N.; Krueger, J.I.; Fischer, J.; Hahn, D.; Kastenmüller, A.; Frey, D.; Fischer, P. “Man’s best friend:” How the presence of a dog reduces mental distress after social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2012, 48, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarberg, K.E. Animal Welfare in Relation to Standards in Organic Farming. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 2002, 43, S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki-Kurosawa, T.; Park, J.H.; Hong, C.C. Laboratory Animals 2014. pp. 267–294. [CrossRef]

- Jukan, A.; Masip-Bruin, X.; Amla, N. Smart Computing and Sensing Technologies for Animal Welfare. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2017, 50, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry for Primary Industries, N.Z. Animal Welfare (Calves): Code of Welfare 2012, 2012. Accessed online: https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/5089/direct.

- of Naval Research, O. Final Workshop Proceedings: Effects of Stress on Marine Mammals Exposed to Sound, 4–5 November, 2008. Accessed online: https://www.onr.navy.mil/media/document/final-workshop-proceedings-effects-stress-marine-mammals-exposed-sound-4-5-november.

- Gonzalez, J.J.; Nasirahmadi, A.; Knierim, U. Automatically Detected Pecking Activity in Group-Housed Turkeys. Animals 2020, 10, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, M.S. Behaviour as a tool in the assessment of animal welfare1. Zoology 2003, 106, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, E.D.; Curley, J.P.; Shizuka, D.; Hobson, E.A. The centennial of the pecking order: current state and future prospects for the study of dominance hierarchies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2022, 377, 20200432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.I.L.d.; Paz, I.C.d.L.A.; Chaves, G.H.C.; Almeida, I.C.d.L.; Ouros, C.C.d.; Souza, S.R.L.d.; Milbradt, E.L.; Caldara, F.R.; Satin, A.J.G.; Costa, G.A.d.; et al. Behaviour and animal welfare indicators of broiler chickens housed in an enriched environment. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnig, A.; Zufferey, R.; Thomann, B.; Zwygart, S.; Keil, N.; Schüpbach-Regula, G.; Miserez, R.; Stucki, D.; Zanolari, P. Animal-Based Indicators for On-Farm Welfare Assessment in Goats. Animals 2021, 11, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corr, S.; McCorquodale, C.; Gentle, M. Gait analysis of poultry. Research in Veterinary Science 1998, 65, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.F.; Lopes, F.A.A.; Filho, L.R.A.G.; Salgado, D.D.; Neto, M.M. Cluster index for estimating thermal poultry stress (gallus gallus domesticus). Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 177, 105704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ScienceDirect. Egg Production, n.d. ScienceDirect. Egg Production, n.d. Accessed: 2024-11-30.

- Roberts, J.R.; Souillard, R.; Bertin, J. Avian diseases which affect egg production and quality. In Improving the Safety and Quality of Eggs and Egg Products; Woodhead Publishing, 2011; pp. 376–393. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Li, X.; Lan, F.; Wen, C.; Wu, G.; Li, G.; Yan, Y.; Yang, N.; et al. Calcium deposition in chicken eggshells: role of host genetics and gut microbiota. Poultry Science 2024, 103, 104073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tarabany, M.S. Effect of thermal stress on fertility and egg quality of Japanese quail. Journal of Thermal Biology 2016, 61, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilani, C.; Confessore, A.; Bozzi, R.; Sirtori, F.; Pugliese, C. Review: Precision Livestock Farming technologies in pasture-based livestock systems. Animal 2022, 16, 100429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Ren, Z.; Li, D.; Zeng, L. Review: Automated techniques for monitoring the behaviour and welfare of broilers and laying hens: towards the goal of precision livestock farming. Animal 2020, 14, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R.; Aguilar, J.; Toro, M.; Pinto, A.; Rodríguez, P. A systematic literature review on the use of machine learning in precision livestock farming. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 179, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, E.; Casey, C.; Mitsch, J.; Vzquez-Diosdado, J.A.; Yan, J.; Dottorini, T.; Ellis, K.A.; Winterlich, A.; Kaler, J. Evaluation of sampling frequency, window size and sensor position for classification of sheep behaviour. Royal Society Open Science 2018, 5, 171442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Biswas, S.; Daigle, C.; Siegford, J.M. Remote Activity Classification of Hens Using Wireless Body Mounted Sensors. 2012 Ninth International Conference on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks 2012, 1, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikurior, S.J.; Marquetoux, N.; Leu, S.T.; Corner-Thomas, R.A.; Scott, I.; Pomroy, W.E. What Are Sheep Doing? Tri-Axial Accelerometer Sensor Data Identify the Diel Activity Pattern of Ewe Lambs on Pasture. Sensors 2021, 21, 6816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, A.; Riordan, D.; Walsh, J. Sensor Technology For Animal Health Monitoring. International Journal on Smart Sensing and Intelligent Systems 2020, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.S.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Groves, P.J.; Gebhardt-Henrich, S.G.; Rault, J.L. Ranging Behaviour of Commercial Free-Range Broiler Chickens 1: Factors Related to Flock Variability. Animals 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, L.v.; Sturman, O.; Bohacek, J. Big behavior: challenges and opportunities in a new era of deep behavior profiling. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimmura, T.; Sato, I.; Takuno, R.; Fujinami, K. Spatiotemporal understanding of behaviors of laying hens using wearable inertial sensors. Poultry Science 2024, 103, 104353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuyttens, F.; Graaf, S.d.; Heerkens, J.; Jacobs, L.; Nalon, E.; Ott, S.; Stadig, L.; Laer, E.V.; Ampe, B. Observer bias in animal behaviour research: can we believe what we score, if we score what we believe? Animal Behaviour 2014, 90, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinami, K.; Takuno, R.; Sato, I.; Shimmura, T. Evaluating Behavior Recognition Pipeline of Laying Hens Using Wearable Inertial Sensors. Sensors 2023, 23, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimmura, T.; Sato, I.; Takuno, R.; Fujinami, K. Spatiotemporal understanding of behaviors of laying hens using wearable inertial sensors. Poultry Science 2024, 103, 104353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiskainen, P.; Järvinen, M.; Skön, J.P.; Tiirikainen, J.; Kolehmainen, M.; Mononen, J. Cow behaviour pattern recognition using a three-dimensional accelerometer and support vector machines. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 2009, 119, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidder, O.R.; Campbell, H.A.; Gómez-Laich, A.; Urgé, P.; Walker, J.; Cai, Y.; Gao, L.; Quintana, F.; Wilson, R.P. Love Thy Neighbour: Automatic Animal Behavioural Classification of Acceleration Data Using the K-Nearest Neighbour Algorithm. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicosia, A.; Duchesne, T.; Rivest, L.P.; Fortin, D. A Multi-State Conditional Logistic Regression Model for the Analysis of Animal Movement. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1611.02690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muminov, A.; Mukhiddinov, M.; Cho, J. Enhanced Classification of Dog Activities with Quaternion-Based Fusion Approach on High-Dimensional Raw Data from Wearable Sensors. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diosdado, J.A.V.; Barker, Z.E.; Hodges, H.R.; Amory, J.R.; Croft, D.P.; Bell, N.J.; Codling, E.A. Classification of behaviour in housed dairy cows using an accelerometer-based activity monitoring system. Animal Biotelemetry 2015, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.N.; Nguyen, T.N.; Khanh, P.C.P.; Tran, D.T. An IoT-Based Design Using Accelerometers in Animal Behavior Recognition Systems. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 17515–17528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütün, A.; Yılmaz, D. Classification of Cattle Behavior Leveraging Accelerometer Data and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing Symposium (IDAP); 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’17. Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Shehada, H.; Ha, D.; Dos Reis, B.; White, R.; Shin, S. Machine Learning-Driven Optimization of Livestock Management: Classification of Cattle Behaviors for Enhanced Monitoring Efficiency. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Machine Learning and Machine Intelligence (MLMI), MLMI ’24. New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Galan, D.; Dominguez-Morales, J.P.; Cerezuela-Escudero, E.; Rios-Navarro, A.; Tapiador-Morales, R.; Rivas-Perez, M.; Dominguez-Morales, M.; Jimenez-Fernandez, A.; Linares-Barranco, A. Embedded neural network for real-time animal behavior classification. Neurocomputing 2018, 272, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settles, B. Active Learning Literature Survey. Technical Report 1648, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2009. Computer Sciences Technical Report.

- Kaseb, A.; Farouk, M. Active learning for Arabic sentiment analysis. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2023, 77, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, D.; Tennakoon, R.; George, Y.; Roy, S.; Bozorgtabar, B.; Ge, Z.; Reyes, M. ALFREDO: Active Learning with FeatuRe disEntangelement and DOmain adaptation for medical image classification. Medical Image Analysis 2024, 97, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, G.; Kirshenbaum, E.; Rajaram, S. A novel traffic analysis for identifying search fields in the long tail of web sites. In Proceedings of the 19th international conference on World wide web - WWW ’10; 2010; pp. 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandi, A.; Diehl, C.; Kharrazi, A.Y.; Scholz, S.A.; Bobkova, E.; Faure, L.; Nattermann, M.; Adam, D.; Chapin, N.; Foroughijabbari, Y.; et al. A versatile active learning workflow for optimization of genetic and metabolic networks. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Du, S.; Ma, Z.; Huo, H.; Peng, G. A Model for Animal Home Range Estimation Based on the Active Learning Method. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2019, 8, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothmann, L.; Wimmer, L.; Charrakh, O.; Weber, T.; Edelhoff, H.; Peters, W.; Nguyen, H.; Benjamin, C.; Menzel, A. Automated wildlife image classification: An active learning tool for ecological applications. Ecological Informatics 2023, 77, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sethi, I. Confidence-based active learning. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2006, 28, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holub, A.; Perona, P.; Burl, M.C. Entropy-based active learning for object recognition. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops; 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcan, M.F.; Broder, A.; Zhang, T. Margin based active learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Learning Theory. Springer; 2007; pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. Maximizing expected model change for active learning in regression. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 13th international conference on data mining. IEEE; 2013; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q.; Li, S.; Du, X.; Yuan, M.; Wang, M.; Song, Z. Density-based one-shot active learning for image segmentation. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 126, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urner, R.; Wulff, S.; Ben-David, S. Plal: Cluster-based active learning. In Proceedings of the Conference on learning theory. PMLR; 2013; pp. 376–397. [Google Scholar]

- Notar, C.E.; Restauri, S.; Wilson, J.D.; Friery, K.A. Going the distance: Active learning. 2002.

- Schjelderup-Ebbe, T. Beiträge zur Sozialpsychologie des Haushuhns. Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Physiologie der Sinnesorgane 1921, 88, 225–252. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes, S.; Sicks, F.; Berger, A. Behaviour Classification on Giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) Using Machine Learning Algorithms on Triaxial Acceleration Data of Two Commonly Used GPS Devices and Its Possible Application for Their Management and Conservation. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunner, R.M.; Wilson, R.P.; Holton, M.D.; Scott, R.; Hopkins, P.; Duarte, C.M. A new direction for differentiating animal activity based on measuring angular velocity about the yaw axis. Ecology and Evolution 2020, 10, 7872–7886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Yoder, N.; Carson, A.; Junge, C.; Allen, D.; Prescott, L.; Bradley, S.; Wymore, G.; Lloyd, K.; Lyle, S. Deep Learning Classification of Canine Behavior Using a Single Collar-Mounted Accelerometer: Real-World Validation. Animals 2021, 11, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, R.; Aguilar, J.; Toro, M.; Pinto, A.; Rodríguez, P. A systematic literature review on the use of machine learning in precision livestock farming. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 179, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilani, C.; Confessore, A.; Bozzi, R.; Sirtori, F.; Pugliese, C. Review: Precision Livestock Farming technologies in pasture-based livestock systems. Animal 2022, 16, 100429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Ren, Z.; Li, D.; Zeng, L. Review: Automated techniques for monitoring the behaviour and welfare of broilers and laying hens: towards the goal of precision livestock farming. Animal 2020, 14, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, C.J.; Huber-Fliflet, N.; Jensen, K.; Zhao, H.; Neary, R.; Ye, S. Empirical Evaluations of Seed Set Selection Strategies for Predictive Coding. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:1903.08816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S. Two faces of active learning. Theoretical Computer Science 2011, 412, 1767–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Q.; Ghosh, S.K. Similarity-based active learning methods. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 251, 123849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flesca, S.; Mandaglio, D.; Scala, F.; Tagarelli, A. A meta-active learning approach exploiting instance importance. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 247, 123320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, X.; Yuan, B.; Lu, J. Active learning via query synthesis and nearest neighbour search. Neurocomputing 2015, 147, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sener, O.; Savarese, S. Active learning for convolutional neural networks: A core-set approach. arXiv, 2017; arXiv:1708.00489 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, P.; Yu, S.; Liu, S.; Jia, J. Bal: Balancing diversity and novelty for active learning. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haussler, D.; Seung, H.S.; Opper, M.; Sompolinsky, H. Query by committee. In Proceedings of the fifth annual workshop on Computational learning theory, 1992; pp. 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womble, J.N.; Horning, M.; Lea, M.A.; Rehberg, M.J. Diving into the analysis of time–depth recorder and behavioural data records: A workshop summary. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2013, 88, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.V.; Bayne, K. Research Animal Behavioral Management Programs for the 21st Century. Animals 2023, 13, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Deb, O.; Patel, A.; Rupprecht, C.; Torr, P.; Trigoni, N.; Markham, A. Towards Multi-Modal Animal Pose Estimation: An In-Depth Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.09312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Feature Description | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-domain Features | Mean | Represents the central tendency of the data. | Statistical measure |

| Variance | Measures how much the data spreads around the mean. | Statistical measure | |

| Standard Deviation | Measures the extent of variability around the mean. | Statistical measure | |

| Interquartile Range | Indicates the range between the 25th and 75th percentiles. | Robust measure | |

| Median Absolute Deviation | Measures variability using the median as a reference. | Robust measure | |

| Median Crossing | Counts how many times the data crosses its median. | Oscillation indicator | |

| Skewness | Captures asymmetry in the data distribution. | Statistical measure | |

| Frequency-domain Features | Spectral Peak | Identifies the dominant frequency component. | Frequency analysis |

| Energy | Represents the total power of the signal. | Frequency analysis | |

| Entropy | Quantifies the randomness in the frequency domain. | Frequency analysis | |

| Kurtosis | Indicates the "peakedness" of the data distribution. | Statistical measure | |

| Crossing Features | Mean Crossing | Counts the number of times the signal crosses its mean. | Oscillation indicator |

| Minimum Value | Smallest value in the signal data. | Extremum | |

| Maximum Value | Largest value in the signal data. | Extremum | |

| Correlation Features | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | Measures the monotonic relationship between signal pairs. | Relationship indicator |

| Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient | Measures the linear relationship between signal pairs. | Relationship indicator |

| Category | Behavior | Occurrences | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Behaviors | Eat | 2235 | Indicates general health and well-being |

| Stop | 1365 | Potential indicator of stress or discomfort | |

| Preening | 1327 | Indicates grooming and self-care, sign of comfort | |

| Rest | 1051 | Reflects a healthy rest cycle and energy recovery | |

| Less Frequent Behaviors | Peck the nest box | 585 | Suggests nesting behavior, potential environmental enrichment indicator |

| Peck the ground | 558 | Exploration or foraging behavior, can reflect access to resources | |

| Move | 339 | Indicates activity level, could be linked to space or environmental stimulation | |

| Head scratch | 277 | May suggest comfort or behavior related to hygiene and health | |

| Dust bathing | 274 | Indicates self-maintenance and health care, behavioral enrichment | |

| Drink | 191 | Hydration status, key welfare indicator | |

| Rare Behaviors | Look around | 164 | Vigilance behavior, possible indicator of environmental awareness or anxiety |

| Peck the sensor | 124 | Interaction with environment, may indicate curiosity or stress | |

| Very Rare Behaviors | Head swing | 114 | Possible sign of discomfort or agitation |

| Shivering | 105 | Welfare concern, potentially due to cold or distress | |

| Get on the nest box | 73 | Indicates nesting behavior, may reflect environmental comfort | |

| Get off the nest box | 66 | Potential indicator of disturbance or stress in the environment | |

| Uncommon Events | Litter exploration | 47 | Exploration behavior, could indicate resource availability and environmental enrichment |

| Get on the perch | 35 | Indicates perching behavior, related to comfort and space utilization | |

| Get off the perch | 35 | May reflect anxiety or environmental disturbance | |

| Stretching | 28 | Sign of physical comfort, stretch can indicate health and well-being | |

| To keep balance | 24 | Can indicate stress or instability, potentially environmental stressor |

| Category | Behavior | Occurrences | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly Rare Events | Tail swing | 23 | Indicates agitation or distress in response to the environment |

| Attack another hens | 13 | Aggression, possible welfare concern or dominance behavior | |

| Beak sharpening | 11 | Potential sign of frustration or need for environmental enrichment | |

| Pecked the sensor | 9 | Interaction with environmental stressor or curiosity | |

| Pecked | 5 | Possible indication of aggression or discomfort | |

| Box Bumping Behavior | 3 | Potential stress or agitation, welfare concern |

| ENTROPY | MARGIN | UNCERTAINTY | RANDOM | EMC | CSS | DWU | ||||||||

| Model | ||||||||||||||

| SVC | 0.7 | 2875 | 0.702 | 2865 | 0.706 | 1175 | 0.701 | 5900 | 0.701 | 6260 | 0.694 | 3670 | 0.711 | 2435 |

| BAG | 0.678 | 1445 | 0.692 | 2400 | 0.684 | 3260 | 0.674 | 4765 | 0.617 | 6250 | 0.675 | 3720 | 0.711 | 4745 |

| DT | 0.577 | 5305 | 0.595 | 6010 | 0.577 | 5305 | 0.597 | 5615 | 0.577 | 5305 | 0.614 | 5080 | 0.577 | 5305 |

| ET | 0.731 | 970 | 0.756 | 1515 | 0.733 | 2440 | 0.707 | 6235 | 0.687 | 6220 | 0.699 | 5700 | 0.711 | 1805 |

| GNB | 0.491 | 3940 | 0.492 | 3645 | 0.501 | 2830 | 0.516 | 3225 | 0.484 | 4860 | 0.477 | 5670 | 0.502 | 3820 |

| HGBC | 0.759 | 2335 | 0.755 | 2195 | 0.757 | 1905 | 0.69 | 3065 | 0.382 | 2345 | 0.745 | 2490 | 0.77 | 2355 |

| KNN | 0.643 | 6005 | 0.642 | 5760 | 0.652 | 3065 | 0.639 | 6250 | 0.641 | 6265 | 0.644 | 6115 | 0.651 | 3255 |

| LGBM | 0.773 | 3160 | 0.747 | 1410 | 0.765 | 3275 | 0.674 | 5370 | 0.607 | 5540 | 0.766 | 3525 | 0.761 | 3105 |

| LR | 0.696 | 6290 | 0.696 | 6025 | 0.696 | 5965 | 0.7 | 6290 | 0.698 | 6290 | 0.704 | 4795 | 0.696 | 6290 |

| MLP | 0.771 | 2550 | 0.776 | 2270 | 0.778 | 2440 | 0.743 | 6035 | 0.74 | 6270 | 0.753 | 5680 | 0.778 | 2460 |

| RF | 0.692 | 1000 | 0.746 | 1310 | 0.722 | 1190 | 0.674 | 6155 | 0.66 | 6270 | 0.674 | 5720 | 0.693 | 1620 |

| ENTROPY | MARGIN | UNCERTAINTY | RANDOM | EMC | CSS | DWU | ||||||||

| Model | ||||||||||||||

| SVC | 0.911 | 5390 | 0.914 | 2830 | 0.914 | 1780 | 0.914 | 5580 | 0.913 | 6145 | 0.913 | 6100 | 0.912 | 2215 |

| BAG | 0.912 | 2825 | 0.916 | 2200 | 0.913 | 2205 | 0.908 | 6240 | 0.897 | 6290 | 0.906 | 3555 | 0.914 | 3350 |

| DT | 0.862 | 6235 | 0.86 | 6175 | 0.862 | 6235 | 0.859 | 6290 | 0.862 | 6235 | 0.86 | 5880 | 0.862 | 6235 |

| ET | 0.939 | 3930 | 0.952 | 1685 | 0.946 | 2100 | 0.937 | 6235 | 0.934 | 6285 | 0.939 | 5700 | 0.944 | 2710 |

| GNB | 0.748 | 3240 | 0.736 | 2985 | 0.762 | 2840 | 0.726 | 2015 | 0.69 | 6290 | 0.698 | 5670 | 0.746 | 3255 |

| HGBC | 0.952 | 1625 | 0.953 | 1790 | 0.955 | 1770 | 0.935 | 4770 | 0.804 | 2345 | 0.943 | 3870 | 0.953 | 1710 |

| KNN | 0.895 | 2980 | 0.893 | 3290 | 0.897 | 2740 | 0.887 | 6215 | 0.886 | 6250 | 0.887 | 6195 | 0.889 | 3475 |

| LGBM | 0.953 | 1735 | 0.951 | 1980 | 0.954 | 1470 | 0.937 | 5325 | 0.929 | 6160 | 0.944 | 4325 | 0.953 | 1645 |

| LR | 0.902 | 3040 | 0.904 | 5185 | 0.903 | 5150 | 0.903 | 6145 | 0.902 | 6260 | 0.905 | 5425 | 0.905 | 2580 |

| MLP | 0.936 | 3050 | 0.935 | 3365 | 0.937 | 4575 | 0.931 | 6120 | 0.933 | 6270 | 0.933 | 5945 | 0.936 | 3150 |

| RF | 0.931 | 3090 | 0.946 | 1495 | 0.942 | 1795 | 0.927 | 6120 | 0.924 | 6270 | 0.927 | 5755 | 0.932 | 2005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).