Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

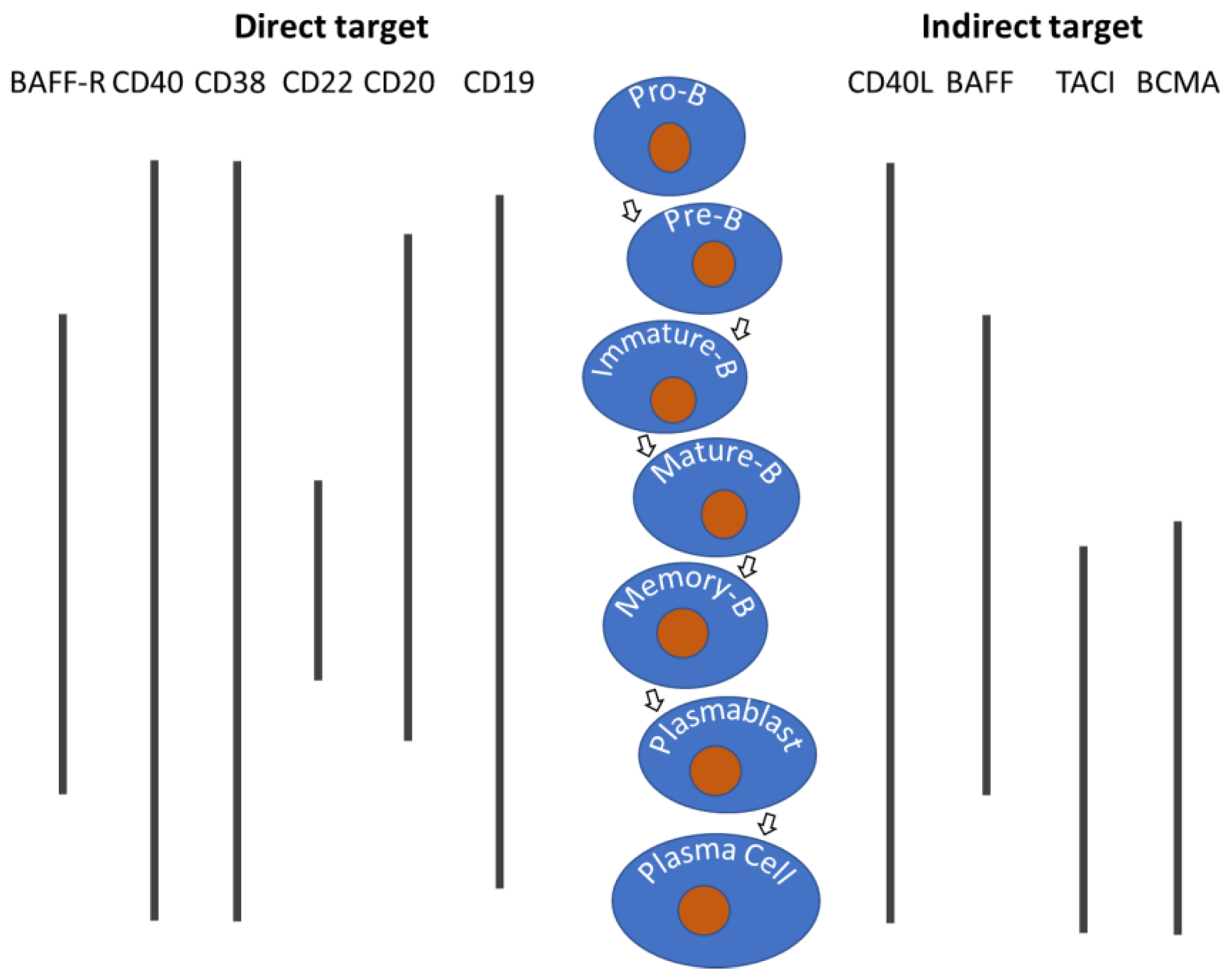

2. Therapeutic Targets of B-Cells in Autoimmune Disorders

3. Biologics Targeting B-Cells for Autoimmune Disease Treatments

3.1. OCREVUS (ocrelizumab) and KESIMPTA (ofatumumab) - Next Generation Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs)

3.2. UPLIZNA (inebilizumab) – Afucosylated Anti-CD19 mAb

3.3. BENLYSTA (belimumab) – mAb Indirectly Targeting B Cells

3.4. Ianalumab (VAY736) – mAb Directly Targeting B Cells

3.5. Dazodalibep (HZN4920/AMG611) – HSA-Fusion Protein Antagonizing CD40L

3.6. PRV-3279 (formerly MGD010) - Bispecific Antibody

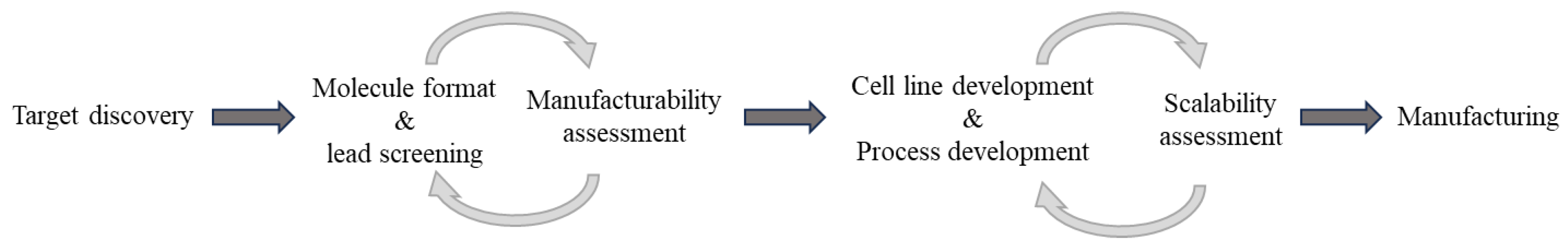

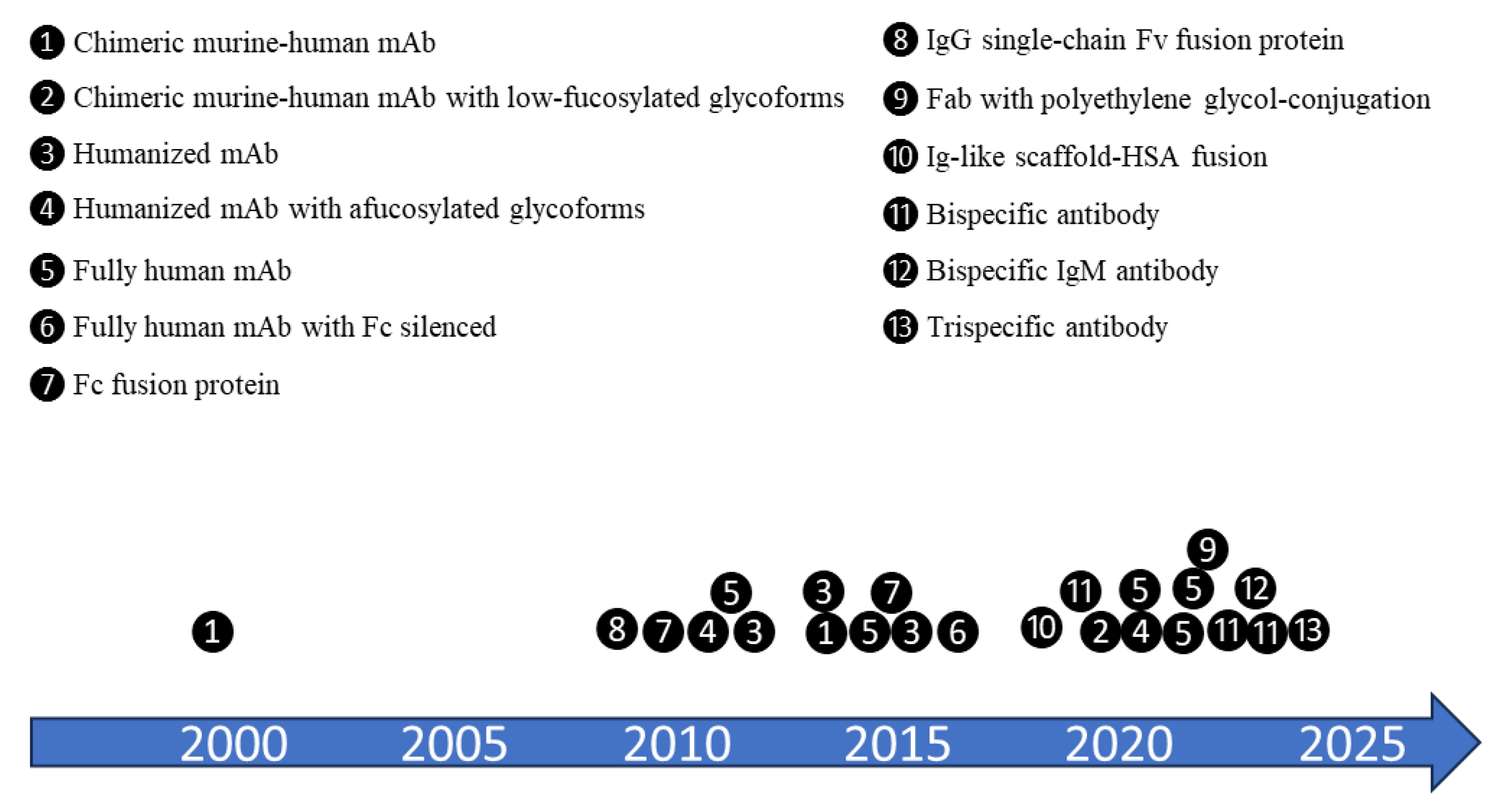

4. Impact of Molecule Format on Process Development and Manufacturability

4.1. Afucosylated mAb

4.2. Fusion Protein

4.3. Bispecific Antibody

5. Manufacturing Scalability

6. Closing Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

ORCID

References

- Kurosaki T. B-lymphocyte biology. Immunol Rev. Sep 2010;237(1):5-9. [CrossRef]

- Townsend MJ, Monroe JG, Chan AC. B-cell targeted therapies in human autoimmune diseases: an updated perspective. Immunol Rev. Sep 2010;237(1):264-83. [CrossRef]

- Barnas JL, Looney RJ, Anolik JH. B cell targeted therapies in autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Immunol. Dec 2019;61:92-99. [CrossRef]

- Frampton JE. Inebilizumab: First Approval. Drugs. Aug 2020;80(12):1259-1264. [CrossRef]

- Merino-Vico A, Frazzei G, van Hamburg JP, Tas SW. Targeting B cells and plasma cells in autoimmune diseases: From established treatments to novel therapeutic approaches. Eur J Immunol. Jan 2023;53(1):e2149675. [CrossRef]

- Du FH, Mills EA, Mao-Draayer Y. Next-generation anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies in autoimmune disease treatment. Auto Immun Highlights. Nov 16 2017;8(1):12. [CrossRef]

- Huda R. New Approaches to Targeting B Cells for Myasthenia Gravis Therapy. Front Immunol. 2020;11:240. [CrossRef]

- Gurcan HM, Keskin DB, Stern JN, Nitzberg MA, Shekhani H, Ahmed AR. A review of the current use of rituximab in autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. Jan 2009;9(1):10-25. [CrossRef]

- Kanatas P, Stouras I, Stefanis L, Stathopoulos P. B-Cell-Directed Therapies: A New Era in Multiple Sclerosis Treatment. Can J Neurol Sci. May 16 2022:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Rubbert-Roth A. TRU-015, a fusion protein derived from an anti-CD20 antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Mol Ther. Feb 2010;12(1):115-23.

- Robinson WH, Fiorentino D, Chung L, et al. Cutting-edge approaches to B-cell depletion in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1454747. [CrossRef]

- Arbitman L, Furie R, Vashistha H. B cell-targeted therapies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. Oct 2022;132:102873. [CrossRef]

- Subklewe M, Magno G, Gebhardt C, et al. Application of blinatumomab, a bispecific anti-CD3/CD19 T-cell engager, in treating severe systemic sclerosis: A case study. Eur J Cancer. Jun 2024;204:114071. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Li M, Wu D, Zhou J, Leung SO, Zhang F. SM03, an anti-human CD22 monoclonal antibody, for active rheumatoid arthritis: a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Rheumatology (Oxford). May 5 2022;61(5):1841-1848. [CrossRef]

- Geh D, Gordon C. Epratuzumab for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. Apr 2018;14(4):245-258. [CrossRef]

- Runkel L, Stacey J. Lupus clinical development: will belimumab’s approval catalyse a new paradigm for SLE drug development? Expert Opin Biol Ther. Apr 2014;14(4):491-501. [CrossRef]

- Bowman SJ, Fox R, Dorner T, et al. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous ianalumab (VAY736) in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b dose-finding trial. Lancet. Jan 8 2022;399(10320):161-171. [CrossRef]

- Furie RA, Bruce IN, Dorner T, et al. Phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of dapirolizumab pegol in patients with moderate-to-severe active systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). Nov 3 2021;60(11):5397-5407. [CrossRef]

- Kahaly GJ, Stan MN, Frommer L, et al. A Novel Anti-CD40 Monoclonal Antibody, Iscalimab, for Control of Graves Hyperthyroidism-A Proof-of-Concept Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Mar 1 2020;105(3)doi:10.1210/clinem/dgz013.

- Fisher BA, Szanto A, Ng W-F, Bombardieri M, Gergely P. Assessment of the anti-CD40 antibody iscalimab in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study. The Lancet Rheumatology. 2020;2(3):11. [CrossRef]

- Visvanathan S, Daniluk S, Ptaszynski R, et al. Effects of BI 655064, an antagonistic anti-CD40 antibody, on clinical and biomarker variables in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIa study. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(6):754-760. [CrossRef]

- Kivitz A. A Phase 2, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Mechanistic Insight and Dosage Optimization Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Dazodalibep (VIB4920/HZN4920) in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Having Inadequate Response to Conventional/Biological DMARDs. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74(9).

- Oganesyan V, Ferguson A, Grinberg L, et al. Fibronectin type III domains engineered to bind CD40L: cloning, expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of two complexes. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. Sep 2013;69(Pt 9):1045-8. [CrossRef]

- Karnell JL, Rieder SA, Ettinger R, Kolbeck R. Targeting the CD40-CD40L pathway in autoimmune diseases: Humoral immunity and beyond. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. Feb 15 2019;141:92-103. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon S. Telitacicept: First Approval. Drugs. Sep 2021;81(14):1671-1675. [CrossRef]

- Bracewell C, Isaacs JD, Emery P, Ng WF. Atacicept, a novel B cell-targeting biological therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. Jul 2009;9(7):909-19. [CrossRef]

- Robak T, Robak E. New anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of B-cell lymphoid malignancies. BioDrugs. Feb 1 2011;25(1):13-25. [CrossRef]

- Frampton JE. Ocrelizumab: First Global Approval. Drugs. Jun 2017;77(9):1035-1041. [CrossRef]

- McCool R, Wilson K, Arber M, et al. Systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing ocrelizumab with other treatments for relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. Apr 2019;29:55-61. [CrossRef]

- Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Cohen JA, et al. Ofatumumab versus Teriflunomide in Multiple Sclerosis. N Engl J Med. Aug 6 2020;383(6):546-557. [CrossRef]

- Herbst R, Wang Y, Gallagher S, et al. B-cell depletion in vitro and in vivo with an afucosylated anti-CD19 antibody. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. Oct 2010;335(1):213-22. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher S, Turman S, Yusuf I, et al. Pharmacological profile of MEDI-551, a novel anti-CD19 antibody, in human CD19 transgenic mice. Int Immunopharmacol. Jul 2016;36:205-212. [CrossRef]

- Rensel M, Zabeti A, Mealy MA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of inebilizumab in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: Analysis of aquaporin-4-immunoglobulin G-seropositive participants taking inebilizumab for ⩾4 years in the N-MOmentum trial. Mult Scler. May 2022;28(6):925-932. [CrossRef]

- Stone JH, Khosroshahi A, Zhang W, et al. Inebilizumab for Treatment of IgG4-Related Disease. N Engl J Med. Nov 14 2024;doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2409712.

- Zhang Y, Tian J, Xiao F, et al. B cell-activating factor and its targeted therapy in autoimmune diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. Apr 2022;64:57-70. [CrossRef]

- St Clair EW, Baer AN, Ng WF, et al. CD40 ligand antagonist dazodalibep in Sjogren’s disease: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Nat Med. Jun 2024;30(6):1583-1592. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Qian Y, Song Y, et al. Design of next-generation therapeutic IgG4 with improved manufacturability and bioanalytical characteristics. MAbs. Jan-Dec 2020;12(1):1829338. [CrossRef]

- Thomann M, Reckermann K, Reusch D, Prasser J, Tejada ML. Fc-galactosylation modulates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity of therapeutic antibodies. Mol Immunol. May 2016;73:69-75. [CrossRef]

- Shields RL, Lai J, Keck R, et al. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J Biol Chem. Jul 26 2002;277(30):26733-40. [CrossRef]

- Olivier S, Jacoby M, Brillon C, et al. EB66 cell line, a duck embryonic stem cell-derived substrate for the industrial production of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies with enhanced ADCC activity. MAbs. Jul-Aug 2010;2(4):405-15. [CrossRef]

- Kilmartin JV, Wright B, Milstein C. Rat monoclonal antitubulin antibodies derived by using a new nonsecreting rat cell line. J Cell Biol. Jun 1982;93(3):576-82. [CrossRef]

- Shinkawa T, Nakamura K, Yamane N, et al. The absence of fucose but not the presence of galactose or bisecting N-acetylglucosamine of human IgG1 complex-type oligosaccharides shows the critical role of enhancing antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. Jan 31 2003;278(5):3466-73. [CrossRef]

- Ripka J, Adamany A, Stanley P. Two Chinese hamster ovary glycosylation mutants affected in the conversion of GDP-mannose to GDP-fucose. Arch Biochem Biophys. Sep 1986;249(2):533-45. [CrossRef]

- Yamane-Ohnuki N, Kinoshita S, Inoue-Urakubo M, et al. Establishment of FUT8 knockout Chinese hamster ovary cells: an ideal host cell line for producing completely defucosylated antibodies with enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Biotechnol Bioeng. Sep 5 2004;87(5):614-22. [CrossRef]

- Malphettes L, Freyvert Y, Chang J, et al. Highly efficient deletion of FUT8 in CHO cell lines using zinc-finger nucleases yields cells that produce completely nonfucosylated antibodies. Biotechnol Bioeng. Aug 1 2010;106(5):774-83. [CrossRef]

- Chan KF, Shahreel W, Wan C, et al. Inactivation of GDP-fucose transporter gene (Slc35c1) in CHO cells by ZFNs, TALENs and CRISPR-Cas9 for production of fucose-free antibodies. Biotechnol J. Mar 2016;11(3):399-414. [CrossRef]

- von Horsten HH, Ogorek C, Blanchard V, et al. Production of non-fucosylated antibodies by co-expression of heterologous GDP-6-deoxy-D-lyxo-4-hexulose reductase. Glycobiology. Dec 2010;20(12):1607-18. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara C, Brunker P, Suter T, Moser S, Puntener U, Umana P. Modulation of therapeutic antibody effector functions by glycosylation engineering: influence of Golgi enzyme localization domain and co-expression of heterologous beta1, 4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III and Golgi alpha-mannosidase II. Biotechnol Bioeng. Apr 5 2006;93(5):851-61. [CrossRef]

- Kanda Y, Imai-Nishiya H, Kuni-Kamochi R, et al. Establishment of a GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase (GMD) knockout host cell line: a new strategy for generating completely non-fucosylated recombinant therapeutics. J Biotechnol. Jun 30 2007;130(3):300-10. [CrossRef]

- Nanda S, Bathon JM. Etanercept: a clinical review of current and emerging indications. Expert Opin Pharmacother. May 2004;5(5):1175-86. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Qian Y, Huang Z, Khattak SF, Li ZJ. Computational insights into O-glycosylation in a CTLA4 Fc-fusion protein linker and its impact on protein quality attributes. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:3925-3935. [CrossRef]

- Way JC, Lauder S, Brunkhorst B, et al. Improvement of Fc-erythropoietin structure and pharmacokinetics by modification at a disulfide bond. Protein Eng Des Sel. Mar 2005;18(3):111-8. [CrossRef]

- Trummer E, Fauland K, Seidinger S, et al. Process parameter shifting: Part I. Effect of DOT, pH, and temperature on the performance of Epo-Fc expressing CHO cells cultivated in controlled batch bioreactors. Biotechnol Bioeng. Aug 20 2006;94(6):1033-44. [CrossRef]

- Hossler P, Khattak SF, Li ZJ. Optimal and consistent protein glycosylation in mammalian cell culture. Glycobiology. Sep 2009;19(9):936-49. [CrossRef]

- Ha TK, Lee GM. Effect of glutamine substitution by TCA cycle intermediates on the production and sialylation of Fc-fusion protein in Chinese hamster ovary cell culture. J Biotechnol. Jun 20 2014;180:23-9. [CrossRef]

- Taschwer M, Hackl M, Hernandez Bort JA, et al. Growth, productivity and protein glycosylation in a CHO EpoFc producer cell line adapted to glutamine-free growth. J Biotechnol. Jan 20 2012;157(2):295-303. [CrossRef]

- Jing Y, Qian Y, Li ZJ. Sialylation enhancement of CTLA4-Ig fusion protein in Chinese hamster ovary cells by dexamethasone. Biotechnol Bioeng. Oct 15 2010;107(3):488-96. [CrossRef]

- Qian Y, Lewis AM, Sidnam SM, et al. LongR3 enhances Fc-fusion protein N-linked glycosylation while improving protein productivity in an industrial CHO cell line. Research. Process Biochemistry. 2017;53:9. [CrossRef]

- Ying J, Borys BC, Samiksha N, et al. Identification of cell culture conditions to control protein aggregation of IgG fusion proteins expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Process Biochemistry. 2012;47(1):6. [CrossRef]

- Qian Y, Jing Y, Li ZJ. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated reduction of IgG-fusion protein aggregation in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnol Prog. Sep-Oct 2010;26(5):1417-23. [CrossRef]

- Shukla AA, Gupta P, Han X. Protein aggregation kinetics during Protein A chromatography. Case study for an Fc fusion protein. J Chromatogr A. Nov 9 2007;1171(1-2):22-8. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Chen Y, Park J, et al. Design and Production of Bispecific Antibodies. Antibodies (Basel). Aug 2 2019;8(3)doi:10.3390/antib8030043.

- Purdie JL, Kowle RL, Langland AL, Patel CN, Ouyang A, Olson DJ. Cell culture media impact on drug product solution stability. Biotechnol Prog. Jul 8 2016;32(4):998-1008. [CrossRef]

- Gomez N, Wieczorek A, Lu F, et al. Culture temperature modulates half antibody and aggregate formation in a Chinese hamster ovary cell line expressing a bispecific antibody. Biotechnol Bioeng. Dec 2018;115(12):2930-2940. [CrossRef]

- Tustian AD, Laurin L, Ihre H, Tran T, Stairs R, Bak H. Development of a novel affinity chromatography resin for platform purification of bispecific antibodies with modified protein a binding avidity. Biotechnol Prog. May 2018;34(3):650-658. [CrossRef]

- Brantley T, Moore B, Grinnell C, Khattak S. Investigating trace metal precipitation in highly concentrated cell culture media with Pourbaix diagrams. Biotechnol Bioeng. Oct 2021;118(10):3888-3897. [CrossRef]

- Qian Y, Khattak SF, Xing Z, et al. Cell culture and gene transcription effects of copper sulfate on Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnol Prog. Jul 2011;27(4):1190-4. [CrossRef]

- Qian Y, Xing Z, Lee S, et al. Hypoxia influences protein transport and epigenetic repression of CHO cell cultures in shake flasks. Biotechnol J. Nov 2014;9(11):1413-24. [CrossRef]

- Qian Y, Sowa SW, Aron KL, et al. New insights into genetic instability of an industrial CHO cell line by orthogonal omics. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 2020;164:12. [CrossRef]

- Qian Y, Rehmann MS, Qian NX, et al. Hypoxia and transforming growth factor-beta1 pathway activation promote Chinese Hamster Ovary cell aggregation. Biotechnol Bioeng. Apr 2018;115(4):1051-1061. [CrossRef]

- Tian J, He Q, Oliveira C, et al. Increased MSX level improves biological productivity and production stability in multiple recombinant GS CHO cell lines. Eng Life Sci. Mar 2020;20(3-4):112-125. [CrossRef]

| Target | Drug Name | Molecule Format / Features | Autoimmune Indications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD20 | RITUXAN (Rituximab) | Chimeric murine-human IgG1k mAb / targeting CD20 on pro-B cells and all mature B cells, but not long-lived plasma or plasmablast cells. | Approved: RA, GPA, MPA, PV Clinical trials: ITP, MG |

[8] |

| OCREVUS (ocrelizumab) | Humanized mAb / with afucosylated glycoforms enhancing ADCC | Approved: RRMS and PPMS | [9] | |

| BRIUMVI (ublituximab) | Chimeric murine-human IgG mAb / with low-fucosylated glycoforms enhancing ADCC | Approved: RRMS, CIS, SPMS | [9] | |

| KESIMPTA (ofatumumab) | Fully human monoclonal antibody / first B-cell-targeting therapy that is intended for self-administration at home | Approved: RRMS, CIS, SPMS Clinical trial: RA |

[9] | |

| Veltuzumab | Humanized mAb / epratuzumab framework and rituximab CDRs | FDA granted orphan status designation for ITP and pemphigus Clinical trial: RA |

[6] | |

| TRU-015 | Fully human IgG fusion protein / a single-chain Fv specific for CD20 linked to human IgG1 hinge, CH2, and CH3 domains but devoid of CH1 and CL domains | Clinical trials: active seropositive RA on a stable background of methotrexate | [10] | |

| Mosunetuzumab | Bispecific antibody / IgG, anti- CD20 and anti-CD3 | Clinical trials: SLE |

[11] | |

| Imvotamab | Bispecific antibody / IgM, anti-CD20 and anti-CD3 | Clinical trials: RA, SLE |

[11] | |

| CD19 | UPLIZNA (inebilizumab) | Humanized IgG1k mAb / with afucosylated glycoforms enhancing ADCC | Approved: NMOSD with AQP4-IgG+ Clinical trials: GM, IgG4-RD |

[4] |

| Obexelimab | Bispecific antibody / simultaneously binds CD19 and FcγRIIb, resulting in down regulation of B cell activity | Clinical trials: GM; IgG4-RD | [12] | |

| Blinatumomab | Bispecific antibody / anti-CD19 and anti-CD3 | Clinical trials: RA, system sclerosis |

[13] | |

| PIT565 | Trispecific antibody / anti-CD19, anti-CD3, and anti-CD2 | Clinical trials: SLE |

NCT06335979 | |

| CD22 | SM03 | Chimeric murine-human mAb / targeting the extracellular portion of CD22 | Clinical trials: SLE, RA | [14] |

| Epratuzumab | Humanized mAb / targeting CD22 with modest ADCC activity | Clinical trials: SLE | [15] | |

| CD38 | Daratumumab | Fully human mAb / targeting CD38 on long-lived plasma cells | Clinical trials: SLE | [12] |

| BAFF/BAFF-R | BENLYSTA (belimumab) | Fully human mAb / neutralizing biologically active soluble form of BAFF | Approved: SLE and lupus nephritis | [16] |

| Ianalumab (VAY736) |

Fully human mAb / antagonizing BAFF-R | Clinical trials: MS, SLE, Sjögren’s syndrome, Diffuse Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis | [17] | |

| CD40/CD40L | Dapirolizumab pegol | Fab / polyethylene glycol-conjugated, anti-CD40L, lacking the Fc-portion to avoid platelet activation | Clinical trials: SLE | [18] |

| Iscalimab (CFZ533) | Fully human mAb / Fc-silenced, antagonizing CD40 | Clinical trials: Graves disease (GD); Sjögren’s syndrome | [19,20] | |

| BI 655064 | Humanized mAb / anti-CD40 blocking CD40-CD40L interaction | Clinical trials: RA | [21] | |

| Dazodalibep (AMG611, HZN-4920) |

Ig-like scaffold-HSA fusion protein / Tn3 scaffolds derived from the 3rd fibronectin type III domain of human tenascin-C, structurally analogous to antibody CDRs and functionally blocking CD40-CD40L interaction | Clinical trials: RA, Sjögren’s syndrome | [22,23,24] | |

| BAFF/APRIL | TAIAI (Telitacicept) |

Fc fusion protein / fused with extracellular domain (amino acids 13-118) of TACI binding to and neutralizing BAFF and APRIL | Approved: SLE (in China) Clinical trials: IgA nephropathy, MS, RA, MG, Sjögren’s syndrome |

[25] |

| Atacicept | Fc fusion protein / fused with extracellular domain (amino acids 30-110) of TACI binding to and neutralizing BAFF and APRIL | Clinical trials: SLE, RA, IgA nephropathy | [26] |

| Cell line | Affected Biosynthesis Pathway | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CHO Lec13 (Pro-Lec13.6a) | Natural deficiency in endogenous GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase (GMD) | [39,43] |

| CHO-DG44 FUT8-/- (BioWa) | FUT8 knockout by homologous recombination | [44] Patent# US6946292B2 |

| CHO-K1 FUT8-/- | FUT8 deletion by ZFN | [45] |

| CHO-gmt3 (CHO-glycosylation mutant3) | GDP-fucose transporter (SLC35C1) inactivation | [46] |

| CHO-RMD | Heterologous expression of GDP-6 deoxy-d-lyxo-4-hexulose reductase (RMD) in the cytosol of CHO cells to deflect the GDP-fucose de novo pathway | [47] |

| CHO-GnT-III | Overexpressed GnTIII catalyzes the formation of a bisecting GlcNAc to reduce Fc core fucosylation |

[48] |

| CHO-SM | GDP-fucose 4,6-dehydratase (GMD) knockout, which makes the cell unable to produce intracellular GDP-fucose and fucosylated glycoproteins in the absence of L-fucose | [49] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).